Abstract

The floor of deep summit craters is often obscured, hindering monitoring and limiting understanding of the dynamic processes within it. At Lascar Volcano, a sudden eruption in December 2022 was accompanied by lava emplacement. We employed satellite and drone imagery to generate high-resolution point clouds, optical and thermal orthomosaics through photogrammetry. Quantitative morphological analysis revealed an initial crater floor uplift from lava extrusion, followed by rapid subsidence that reduced nearly half the volume and formed a central funnel-shaped depression. To investigate surface deformation linked to internal structure evolution, we experimentally simulate lava dome extrusion and subsidence in a scaled 3D-printed mold. The analogue experiments reproduced a funnel-shaped structure consistent with satellite observations and demonstrated the extrusion along divergent faults followed by piston-like subsidence accommodated along convergent faults. The structural pattern constrains underlying conduit geometry and provides insights into dome emplacement dynamics and magma withdrawal mechanisms in upper conduits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volcanoes in subduction zones typically produce viscous lava that does not flow far away from a volcanic vent, instead accumulating above and around the vent to form lava domes1,2. Lava domes present a wide range of morphologies, from tall, steep-sided upheaved plugs and peléan domes to flat, rounded low lava domes and coulées3. Their morphological features are primarily governed by magma rheology (viscosity), extrusion rate, substrate topography, and growth style (endogenous and exogenous growth4,5). In some instances, lava extrusion confined within a deep crater may form a dome-shaped cap or plug atop the magma conduit2, or partially to completely infill the crater, creating low-relief and subhorizontal features6. Such lava domes or bodies typically undergo periodic phases of construction and destruction, as has been observed at Lascar6,7, Popocatépetl8,9, Colima10,11, and Cleveland12,13.

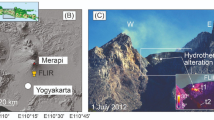

Magma ascent within a conduit and dome extrusion are complex processes subject to the non-linear effects of crystallization and gas loss14. Minor changes in magma or conduit conditions can drive fluctuations in discharge rate and eruption regime15,16. Consequently, dome-building volcanoes commonly exhibit cyclic eruptive patterns characterized by alternating phases of dome growth and collapse, interspersed with short-lived, shallow-source explosive events17,18. Dome-building volcanoes therefore produce some of the most unpredictable and devastating types of eruptions19,20. At elevated volcano summits, gravitational collapse of oversteepened dome flanks or pressurized domes can trigger rapid decompression and lead to explosive eruptions associated with pyroclastic flows and surges21,22,23. Changes in dome permeability and localized strength weakening due to hydrothermal alteration also contribute to instability and collapse24,25, resulting in the generation of destructive block and ash flows and pyroclastic density currents26,27. Furthermore, dome failure occurs not only at the margins but also at the centre, as we observed during the lava emplacement event at Lascar volcano in 2023.

The surface of intracrater domes often exhibit ring structures during emplacement. Concentric structures and pressure ridges develop during extrusion, likely attributed to cooling contraction28,29 and confinement by surrounding crater walls6,9. Subsidence is characterized by concentric fractures encircling a central depression on the dome top6,9. These concentric fractures are interpreted as surface expressions of subsurface fault systems that accommodate inward subsidence or collapse and help delineate the geometry of the underlying conduit6,30,31. The manner of subsidence or collapse is thought to be the consequence of magma withdrawal from a depressurized conduit6,9 or deflation of extruded lava bodies28, although the mechanism remains poorly understood. Ring patterns are also evident in thermal images during both growth and collapse phases, manifesting as temperature variations arranged in concentric formations, as seen at Santiaguito30,32, Colima10,29, Cleveland33 and Nevado del Ruiz34. Owing to the inherently unstable and unpredictable nature of dome-building volcanoes, evaluating lava dome emplacement advances the understanding of magma ascent dynamics and discharge rates, the mechanisms driving dome growth and collapse, transitions between effusive and explosive regime, and provides a vital reference for predicting related volcanic hazards.

Changes in morphological and thermal properties serve as the most direct indicators for assessing lava dome emplacement and associated crater changes. A variety of remote sensing approaches based on photogrammetric principles are employed for this purpose, including ground-35,36,37, aerial-38,39, and drone-31,40 based observations, as well as satellite monitoring utilizing optical41, infrared42,43, and synthetic aperture radar data11,12,44,45. Despite the integration of diverse remote sensing techniques capable of providing high spatio-temporal correlation, observations remain confined to the object surface and cannot reach its interior. The internal evolution during lava emplacement has been reconstructed through numerical simulations46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 and laboratory experiments. Sandbox analogue modeling, a widely used laboratory method in geology, is defined as a scaled and repeatable simulation of natural processes54,55. Previous analogue experiments have extensively investigated dome extrusion using temperature-independent (isothermal) Bingham viscoplastic fluids3,56, viscous Newtonian fluids57,58 and temperature-dependent Bingham materials4,59,60,61,62. These studies demonstrate that lava dome morphology is governed by yield strength, cooling rate, eruption rate, solid carapace, and underlying slope. Ductile materials injected into a brittle cone have been used to simulate solid crust formation63 and the endogenous intrusion of a cryptodome64. Granular materials have been used to model viscous lava lobes65 and near-solid spine extrusion66,67. Few works have concerned the development of internal strain and structure within extruding domes58,64,65,66,67. However, the above studies have substantially advanced understanding of extrusion processes, dome subsidence or collapse has not yet been experimentally explored.

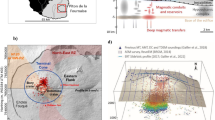

Lascar Volcano, situated in northern Chile (5592 m a.s.l.; 23°22’S, 67°44’W; Fig. 1a), is among the most active volcanoes in the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes. Volcanism in this region results from the subduction of the oceanic Nazca Plate beneath the western margin of the South American Plate68. Historical unrest at Lascar has been recorded since the 1840s69. Volcanic activity between 1984 and 1993 involved four cycles of andesitic lava dome growth and collapse6,7, with action confined to the inner crater of the western crater (Fig. 1b). Each cycle began with dome extrusion, followed by dome collapse accompanied by frequent minor explosions, and ultimately culminated in a major explosive event6. The last recorded lava dome extrusion occurred following the largest historical eruption (VEI 4) in April 199370, and was destroyed during an eruption in December 19936,71. Since then, Lascar has ended its cyclic behavior and entered a phase of irregular and relatively quiescent activity. This phase is characterized by sustained fumarolic degassing and gas plumes72,73, interrupted by occasional explosions of varying magnitudes (mostly VEI 1-274,75). Until recently on 10 December 2022, a sudden explosion produced an ash plume rising ~6 km above the crater rim76. Activity subsequently declined, with several minor explosions occurring between 26 and 28 January 2023. These explosions were accompanied by incandescent ejecta and gas plumes that reached heights of up to ~1.9 km above the crater rim77. On 31 January 2023, satellite imagery revealed a dome-like effusive lava extrusion on the crater floor78. Thereafter, volcanic activity diminished to a quiescent state. The renewed effusive activity likely signals changes in magma discharge rate and current eruptive regime, thereby elevating volcanic hazards. Given Lascar’s popularity as a tourist destination in the San Pedro de Atacama region with hikers climbing up to the crater rim almost daily, such unpredictable activity poses high risks to tourists and local communities.

a Hillshade map generated from Pléiades data (acquired on 01 October 2022) illustrates the main components of Lascar volcano: the truncated western cone (dormant) and eastern cone (active). The inset shows the location of Lascar in northern Chile and a webcam capture of the eruption on 10 December 202277. The yellow star and dashed line demarcate the launch point and flight path of the drone survey, starting at a safe distance on the southern flank. b Panchromatic Pléiades image of the eastern cone, which comprises three partially overlapping craters, the western of which is active. The arrow marks the inner crater of the western crater, where lava dome emplacement occurred. Hillshade and satellite maps created using ArcGIS Pro (v3.3). c Tri-stereo acquisition mode of the Pléiades satellite, which consists of three nearly simultaneously captured images with forward-, near nadir-, backward-looking. d Setup of the analogue experiment. The map view is realized by a camera positioned vertically above the table, while the section view is captured by a side camera placed in front of the glass. The inset shows a 3D-printed mold of Lascar’s inner crater at 1:100 scale, used to replicate realistic topographic constraints in the experiment.

Here, we integrated satellite and drone observations with laboratory analogue experiments to investigate the 2022-2023 lava emplacement event at Lascar. We acquired a sequence of Pléiades tri-stereo satellites images (Fig. 1c) together with drone surveys to cover the period of unrest. Photogrammetric processing of the satellite and thermal drone imagery produced high-precision datasets, including submeter-scale optical and thermal orthomosaics, and dense point clouds (equivalent to ~1 m resolution digital elevation models). We quantified time-progressive topographic changes of the inner crater by computing point cloud differences and volume changes. Based on remote sensing observations, we designed analogue experiments using a 3D-printed mold replicating the near-natural morphology of Lascar’s inner crater (Fig. 1d). We utilized granular sand material to simulate dome extrusion and subsidence from the same conduit. This integrated approach links surface deformation to internal structure evolution, providing insights into the mechanisms governing dynamic deformation during lava dome emplacement at Lascar’s crater. While this study focuses on a short-term (weeks) event at Lascar, it contributes to a broader understanding of lava dome emplacement processes at other dome-building volcanoes and helps to anticipate future activity and mitigate associated volcanic hazards.

Results and Discussion

Satellite and drone observation

We analyzed topographic changes before, during, and after the 2022-2023 lava emplacement event using photogrammetrically reconstructed satellite data acquired between 01 October 2022 and 25 October 2023 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). On 01 October 2022, prior to the 10 December 2022 eruption (Fig. 2a), the inner crater measured ~300 m in diameter and ~150 m in depth (Fig. 2e). Topographic profiles revealed an asymmetric pre-eruption topography, with steeper western and northern inner walls (~60°-75°) compared to the less sloping eastern and southern sides (~45°-60°) (Fig. 4). By 25 January 2023, approximately 1 month after the eruption, new volcanic deposits had filled the deep inner crater (Fig. 2b), elevating the crater floor by ~20 m (Fig. 4). On the topographic change map, these deposits appeared as a relatively flat, pancake-shaped extrusion body (Fig. 3a). In satellite imagery, their surface appeared bright, a feature interpreted as light-colored hydrothermal deposits such as sulfur and other precipitates (Fig. 2b). The new surface exhibited linear to curved, flow-like patterns, suggestive of extrusion and flow movement (Fig. 2f). Its slope gently inclined (~10°) toward the less steep eastern and northern inner walls (Fig. 4a).

Two eruptions occurred on 10 December 2022 and 26 January 202377. a−d Orthomosaics (0.5 m/pixel) generated from the Pléiades panchromatic band. Black boxes delineate the areas shown in the zoomed views. b Whitish alteration and sulfur deposits are visible on the crater floor. c Ring-shaped snow patterns on the funnel slope. d Erosional ravines along the funnel slope. The blue circle marks the estimated conduit extent at Lascar31. e−h Point cloud slope maps derived from Pléiades tri-stereo data, emphasizing post-eruptive topographic features. Black regions indicate missing points in the point cloud, corresponding to shadowed areas. f Flow-like surface patterns suggesting effusive extrusion. g Funnel structure on the crater floor. h Funnel structure persisted until the last data acquisition. Orthomosaic and slope maps created using ArcGIS Pro (v3.3).

Point cloud differencing maps (M3C2 distance) illustrate the temporal evolution of the inner crater topography across successive intervals: (a) 01 October 2022 and 25 January 2023, (b) 25 January 2023 to 22 February 2023, (c) 22 February 2023 and 25 October 2023, and (d) cumulative change from 01 October 2022 to 25 October 2023. Red dashed lines (a-a' and b-b') indicate the locations of topographic profiles depicted in Fig. 4. Topographic change maps created using ArcGIS Pro (v3.3).

Profile locations are shown in Fig. 3a. a Profile a-a' in the W-E direction, illustrating asymmetric inner walls, uplift of the crater floor following lava extrusion, and the geometry of the subsequently developed funnel. b Profile b-b' in the N-S direction. The inferred extent of the initial lava extrusion is delineated by dashed lines. Point cloud profiles created using CloudCompare (v2.13.2).

Between 25 January 2023 and 22 February 2023, a funnel-shaped depression developed near the center of the newly emplaced flat crater floor (Fig. 2g). Topographic change maps confirmed that the area of material removal corresponded precisely to the funnel structure (Fig. 3b). Following a minor, low-energy explosion on 26 January 202377, the volume of deposits on the northern crater floor (hereafter referred to as the northern deposit) increased (Fig. 3b). The funnel reached ~80 m in diameter and ~20 m in depth, with inward slopes averaging ~40° (Fig. 4a). The bottom of the funnel was relatively flat and partially filled with redeposited debris originating from the northern deposit and material eroded from the funnel slopes (Fig. 2g). Topographic profiles revealed that the funnel was symmetrical in the E-W direction (Fig. 4a) but asymmetrical in the N-S direction owing to localized debris accumulation (Fig. 4b). The surrounding unsubsided crater floor was preserved as a flat terrace, contrasting with the steep, blocky funnel slopes (Fig. 2g). Snow accumulation within the funnel was confined to the slopes, displaying a ring pattern, whereas the flat bottom remained snow-free, likely due to debris cover (Fig. 2c). The terrace was partially snow-free, implying elevated temperatures relative to adjacent areas. The funnel structure (Fig. 2h) remained morphologically stable through the last data acquisition on 25 Oct 2023 (Fig. 3c), nearly 10 months after the eruption. Nonetheless, the development of erosional ravines along the funnel slopes indicates continued inward mass wasting and transport of surface material (Fig. 2d).

Close-range optical and thermal drone observations provided crucial details that could not be obtained from satellites (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Optical drone images from 01 February 2023 showed that the funnel-shaped depression had already developed, with a diameter of ~68 m (Fig. 5a). The funnel appeared distinctly darker than the whitish to greyish tephra and pyroclastic materials covering the remaining crater floor (Fig. 5a). Predominant concentric fractures encircling the funnel were clearly visible (Fig. 5a). The funnel coincided spatially with a circular high-temperature anomaly in thermal orthomosaic (Fig. 5c), suggesting that the color difference may have been caused by thermal alteration of surface deposits. Thermal data further displayed inwardly radiating patterns along the funnel slopes (Fig. 5c), corresponding to mass-wasting features identified in the optical imagery (Fig. 5a). Elevated temperatures were detected in northern deposits, along the funnel margins, and at the boundary between the crater floor and inner crater walls (Fig. 5c). These hot residual substances in the northern deposits were likely incandescent ejecta contributed by the minor explosion on 26 January 2023. As of 26 February 2023, the funnel had enlarged to ~88 m in diameter (Fig. 5b). Continuous downslope movement of material from the northern deposit into the funnel was shown (Fig. 5b). During this time, thermal anomalies within the funnel largely diminished, indicating that the hot funnel had largely cooled (Fig. 5d). The northern deposit had also mostly cooled, with only a few hot residues remaining around the funnel margin (Fig. 5d). Heat fissures still persist, but have weakened accordingly (Fig. 5d).

a Georeferenced drone image showing the funnel structure on the crater floor. The extent of the funnel is outlined by a white dashed circle. Concentric fractures surrounding the funnel are indicated by red arrows. b Georeferenced drone image revealing enlargement of the funnel, marking its progressive development. c Thermal orthomosaic (0.75 m/pixel) showing the highest thermal anomalies concentrated in a circular area on the crater floor, corresponding to the funnel. d Thermal orthomosaic (0.75 m/pixel) displaying markedly reduced thermal anomalies. The funnel and the northern deposit are largely cooled. Optical and thermal maps created using ArcGIS Pro (v3.3).

Combining satellite and drone observations provides a comprehensive depiction of lava emplacement within Lascar’s inner crater. The sequence began with uplift of the crater floor due to new lava extrusion, followed by the formation of a central conical depression-the funnel. We interpret this funnel structure as a consequence of the erupted or extruded material draining back into the underlying conduit, with both subsidence and solidification proceeding rapidly. Subsidence likely began around or shortly after 25 January 2023, and the funnel structure had formed by 01 February 2023. The funnel subsequently enlarged and cooled over time, from ~68 m in diameter on 01 February 2023 (hot), to ~80 m on 22 February 2023 (cold), and ~88 m on 26 February 2023 (cold), eventually solidifying into a lava plug located at the top of the inferred magma conduit. The funnel-shaped plug persisted through the latest observation on 25 October 2023. Notably, the location and dimensions of the funnel closely coincide with a ring structure (Fig. 2d), which was interpreted as reflecting the underlying conduit geometry, supporting its association with conduit-scale deformation31. Based on these findings, we designed a series of scaled analogue experiments to verify the hypothesis of an extrusion-subsidence mechanism operating from the same conduit.

Modeling dome extrusion and subsidence in 3D-printed mold

We utilized granular material to simulate dome growth and subsidence in a 3D-printed mold (Fig. 7) and on a flat surface (Supplementary Fig. 6). The 3D-printed mold provided a down-scaled representation of Lascar’s inner crater (Fig. 1d), allowing assessment of the impact of pre-existing topography on dome evolution and final morphology. Map- and section-view linked surface displacement with internal structure development, while displacement field and vorticity maps visualize particle movement and shear strain localization, helping to analyze the evolution of the dome structure throughout the growth and subsidence processes.

The extrusion process was divided into two main stages. The first stage was distinguished by rapid vertical and lateral growth (Fig. 6a). Material was pushed out of the conduit (cylinder), forming a conical dome whose height and width increased rapidly (Fig. 6a). Vorticity maps reveal two sets of distinctive shear faults that initiate at the conduit edge (Fig. 7q): two outward-dipping normal faults converge upward and propagate to the dome top, while two inward-dipping reverse faults reach the dome slope (Fig. 7r). Displacement maps show that new material ascends vertically along these shear faults, intruding into the dome interior and pushing the internal material upward (endogenous growth; Fig. 7m). Owing to the homogeneous nature of the granular material, no discernible surface deformation caused by internal swelling was observed. This suggests that the contribution of endogenous growth to dome development is negligible in this setting. Asymmetric crater walls influenced dome evolution by forcing material to spread preferentially toward the less steep wall, resulting in asymmetric dome growth (Fig. 7i). Accordingly, shear faults developed asymmetrically, with the fault adjacent to the steeper crater wall exhibiting a steeper dip (Fig. 7r). Vertical displacement decreased upward from the conduit and gradually transitioned into lateral movement along the reverse faults (Fig. 7m). Exogenous growth commenced when material breached the dome surface and expanded laterally (Fig. 7n). Extruded material accumulated at the dome margins, steepening the flank. Once the slope exceeded the angle of repose (~40°), it triggered gravitational failure (Fig. 6b). Collapsed material slid down the dome flank and formed talus aprons at the dome base (Fig. 7i). Subsequent slope failures progressively buried the talus, while the marginal slope maintained at the angle of repose throughout extrusion (Fig. 7j). The lateral movement of material turned into stable talus deposits at the normal faults (Fig. 7n). As extrusion continued, the rate of vertical growth declined while lateral expansion became dominant, indicative of the second stage (Fig. 6a). The dome summit gradually flattened while continuing to expand asymmetrically (Fig. 7j).

a Dome height over time, showing an initial stage of rapid vertical growth followed by a second stage dominated by lateral expansion. b Dome diameter over time, indicating discontinuous increases in radius attributed to slump or landslide events. c Funnel depth over time, showing an early down-sag stage with continuous subsidence of the dome top and a later stage characterized by discontinuous collapse driven by gravitational failure. d Funnel diameter over time, highlighting the overall subsidence of the dome top prior to the depression formation. Measured values see Supplementary Data 1.

a−d Map view digital images illustrating dome and funnel morphology. e−h Map view displacement fields and vectors (black arrow), showing surface deformation characterized by concentric ring patterns. i−l Section view digital images displaying asymmetrical dome growth followed by symmetrical subsidence. m−p Section view displacement fields and vectors, revealing internal deformation strength and particle movement direction, indicative of piston-like subsidence. q−t Vorticity maps visualizing shear strain localization throughout dome evolution. Positive values (blue) correspond to clockwise particle rotation, while negative values (red) correspond to counterclockwise rotation. Vorticity intensity represents the velocity of particle rotation. Images created using LaVision DaVis (v10.0.5).

The final sand dome was asymmetric, measuring 85 mm in height and 182 mm in width, with steep flanks (~40°) and flat summit inclined toward the less steep crater wall (Fig. 7j). The crater walls constrained lateral widening and instead promoted vertical growth, yielding a dome taller than that extruded on a flat surface (Supplementary Fig. 6). In map view, the dome appears sub-circular, reflecting the influence of uneven pre-existing topography (Fig. 7b). The center of the dome summit is dominated by vertical growth, whereas the dome margins exhibit the strongest lateral deformation, marked by constant slumping (Fig. 7e). These dynamics manifest as a concentric ring deformation pattern on the dome surface (Fig. 7f). Since the material spreads toward the less steep wall, the center of the concentric rings is offset from the center of the displacement map (Fig. 7e). Notably, as the dome widens, the deformation zone does not expand accordingly (Fig. 7f). Instead, it remains confined within a limited range delineated by two sets of shear faults, with inward-dipping faults defining the deformation zone slightly larger than the conduit diameter (Fig. 7r).

The subsidence process consisted of an initial down-sag stage followed by a collapse stage (Fig. 6c). The down-sag stage began with the onset of the piston moving downward, drawing the material into the conduit and deforming the dome (Fig. 7c). Vorticity map evidences two outward-dipping reverse faults and two inward-dipping normal faults that nucleated at the conduit margins and rapidly propagated upwards (Fig. 7s). Once these shear faults reached the surface, a shallow bowl-shaped depression (~20° slope) formed on the dome top (Fig. 7k). Notably, a brief, overall subsidence of the dome top was observed prior to depression formation (Fig. 6d). As the piston continued to descend, material on the slope continuously slid downward under the action of gravity (Fig. 7d). The depression gradually deepened and evolved into a deeper funnel-shaped structure (Fig. 7l), marking the transition to the collapse stage (Fig. 6c). This stage was characterized by intense slumping of slope material driven by gravitational instability. As subsidence progressed, the marginal slope of the funnel steepened but did not exceed ~35° (Fig. 7p). Profile views of the displacement map demonstrate a piston-like subsidence of the dome, accommodated by movement along inward-dipping ring faults (Fig. 7o). Meanwhile, the talus deposits remained stable throughout the subsiding process (Fig. 7p).

Prior asymmetric dome growth caused material to spread away from the conduit, producing a depression offset from the geometric center of the dome (Fig. 7g). In section view, however, the funnel and associated ring faults appear symmetrical, with their axis of symmetry aligned with the center of the underlying conduit (Fig. 7s). Surface displacement displays concentric ring patterns, with deformation mainly occurring on the funnel slope (Fig. 7g). The accumulation of slumped material at the funnel base produced a non-planar displacement field dominated by vertical motion (Fig. 7h). Inward-dipping normal faults delineate and magnify the extent of surface displacement, thereby resulting in a deformation zone larger than the conduit diameter (Fig. 7t).

Limitations of satellite photogrammetry

Satellite photogrammetry has proven effective and accurate for monitoring real-time volcanic activity, as demonstrated at Lascar in this study and at other volcanoes79,80, and for 3D mapping of morphological changes and associated volcanic products81,82,83,84. This approach is particularly useful for remote, high-altitude summit craters where field or airborne surveys are challenging41,85. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that satellite observations have inherent limitations, along with uncertainties introduced during data processing and their implications.

Satellite imagery is constrained by spatial and temporal resolution. The Pléiades data (panchromatic band) used in this study provide a spatial resolution of 0.5 m, which remains insufficient to discern details in small structures. Satellites operate on fixed orbits and revisit times, for example, Pléiades 1A and 1B have a revisit time of 26 days86. Crater morphology often changes rapidly, as in our case at Lascar, satellite observation may not be able to capture these changes in real time. Photogrammetric reconstruction of a topography model requires at least two images acquired from different viewing angles. However, obtaining high-quality stereo pairs or triplet is challenging in high-latitude regions or rugged terrain. The high cost of acquiring high-resolution commercial satellite imagery further limits the feasibility of frequent monitoring. Optical satellite sensors are highly dependent on solar illumination and cloud coverage. Variations in sunlight and atmospheric conditions can affect image consistency. In active volcanic craters, fumaroles, gas or ash plumes often degrade image quality and reduce intrinsic resolution accordingly. Moreover, in steep stratovolcanoes, deep craters can introduce geometric distortions and shadow effects. The extent of shadow on the crater floor is determined by the incidence angle of the satellite (Fig. 1c) and solar altitude angle. The crater floor is frequently obscured when imaged from oblique angles. This increases the need of incorporating a nadir-viewing image in triplet acquisitions to ensure adequate coverage of crater floors.

The source of uncertainty include point cloud uncertainty and point cloud registration uncertainty. Point cloud uncertainty primarily stems from errors in the satellite sensor models and the absence of on-site ground control points (GCPs). Orientation and position accuracy rely solely on rational polynomial coefficients (RPCs), a sensor orientation model embedded in satellite metadata. The RPC model is widely used for geometric modeling, including orthorectification and 3D reconstruction from tri-stereo satellite imagery87. In the absence of GCPs, previous work has demonstrated that Pléiades stereo imagery is capable of resolving submeter-scale height changes88. In this study, rather than georeferencing to an absolute position, we registered the Pléiades dataset relative to each other and compared relative changes. The use of the same GCPs for all Pléiades data ensured co-registration among the various datasets and thus the repeatability of multi-temporal comparisons. This approach requires careful selection of GCPs, as errors between control points from different datasets can propagate into the derived point cloud. We used the iterative closest point (ICP) algorithm-based fine registration tool in CloudCompare to align the Pléiades-derived point clouds. The ICP algorithm constructs a rigid transformation matrix by searching point-to-point correspondences between two datasets and achieves accurate alignment through iteration89. This technique is widely applied in 3D point cloud registration and has proven to be stable and robust89. However, the Pléiades-derived point clouds exhibited non-homogenous point density, with obvious sparser regions and data gaps evident within the deep inner crater. These deficiencies were mainly attributable to poor image contrast caused by gas emissions, snow cover, and especially shadows, which reduced matching accuracy, decreased the success of cross-correlation, and ultimately led to misalignment. Furthermore, variations in snow and shadow coverage across different acquisition periods resulted in inconsistent point cloud densities and ranges of missing data, introducing errors into the registration process (Supplementary Table 2).

Quantifying morphological change is challenging due to missing data on the crater floor caused by shadow effects. Interpolating a DEM (digital elevation model) over missing data can introduce substantial artefacial values. A DEM is inherently constrained to representing 2.5D surfaces and therefore cannot describe vertical surfaces, such as steep or overhanging crater walls. In addition, the fixed resolution of a DEM limits the preservation of subtle details present in the raw data90. To address these limitations, we applied point cloud differencing using the Multiscale Model-to-Model Cloud Comparison (M3C2) algorithm. The M3C2 method directly computes the distance between two point clouds in three dimensions without meshing or gridding to generate a DEM91. This approach minimizes interpolation artifacts and is robust when handling point clouds with missing data and variable point density. We calculated volume changes using the 2.5D volume method in CloudCompare, which estimates volume differences by summing the individual contributions of each point. It is important to note that uncertainties in the point clouds and their registration propagate into the differencing process, thereby amplifying errors in the volume calculations. In this study, the presence of large data gaps in point clouds mean that the reported volume changes should be regarded as approximate estimates rather than absolute values and must therefore be interpreted with caution.

Limitations of analogue experiment

Scaled analogue modelings are useful tools for simulating and investigating earth’s complex processes under controlled laboratory settings. However, they are subject to several limitations, including simplification of complex natural systems, scaling constraints, material properties, and human operating or measurement errors92. Previous laboratory studies have demonstrated that dome growth and morphology are primarily governed by the physical properties of the analogue materials, such as yield stress3,56,58,61, extrusion and cooling rates4,59,60,61,62, tensile strength of the solid outer crust63,93, and the presence of a flanking talus apron3,94.

A main limitation of the analogue experiments in this study was the neglect of the complex behavior of cooled and solidified carapace encompassing a hot, ductile magma core93,95. Buisson and Merle63 used a brittle material covering a ductile core to explore the role of brittle crust thickness (mechanical strength) in dome evolution. As the dome grew, radial and concentric tension fractures developed on the dome surface, forming discrete brittle blocks. With further lateral expansion, these blocks slid away from the summit toward the dome margin, suggesting that the surface experienced concentric extension and behaved as a deformable surface rather than a rigid shell63. Similar outward radial movement and circumferential stretching of surface material during dome growth were observed in earlier analogue experiments employing viscoplastic materials3. In a natural case, such as at Colima, dome growth is accompanied by continued dispersion of the cooled solid carapace at the dome summit10,48. This suggests that the outer part of a growing natural dome does not act as a stiff and rigid crust, instead is influenced by dynamic processes of granular deformable surface material. Concentric stretching of the dome surface in both laboratory and natural cases closely resembles the concentric deformation caused by lateral spreading of surface material shown in our analogue experiments.

As a result of the extrusion experiments, we obtained a near-axisymmetric sand dome with a flat-top, encircled by steep talus aprons (Fig. 8a). The final morphology and formation mechanisms of the sand dome resemble those of peléan lava domes in nature. A Peléan-type dome is characterized by a high height-to-radius ratio, a pyramidal or conical shape with steep flanks, and extensive talus aprons2. The slope of the talus flank is determined by the internal friction of cohesionless talus rubble (~30°-45°3). Peléan dome commonly develop in high-viscosity andesitic to rhyolitic volcanic systems1,2, with most known examples at Colima11,96, Soufriére Hills97, Merapi98, Santiaguito99,100 and Chaiten101,102. In profile view (Fig. 8a), the analogue experiment revealed a pair of outward shear faults that initiated at the conduit edge and propagated to the dome surface, completing the endogenous-to-exogenous transition. These shear bands evolve to the dome surface and permit exogenous growth only when the lava is highly crystalline and capable of brittle fracture, and when shear strain rates are sufficiently high49. Consequently, peléan domes are commonly associated with the development of spine protrusions2,66,67. In short, the Peléan-style dome shape, the formation of talus apron, and the evolution of internal shear faults in our experiments demonstrate that the brittle analogue material employed is suitable for simulating dome extrusion. However, its applicability is limited to cases involving viscous extrusion of highly crystalline lava.

Associated morphological and structural features, including talus accumulation, concentric surface deformation patterns, and fault orientations are illustrated. a Extrusion phase: Material extrudes from the conduit, producing an asymmetric dome with a flat summit and encircled by steep talus aprons. b Subsidence phase: Material withdraws into the conduit, creating an axisymmetric, funnel-shaped depression.

Laboratory experiments regarding dome subsidence are partly comparable to those investigating caldera collapse103,104,105,106 or pit crater formation107,108. Regardless of differences in nucleation points and dip directions of ring faults105,109, these structures commonly manifest as concentric tension fractures at the surface110. Due to the homogeneity of the granular materials used in our experiments111, we were unable to reproduce the concentric tension fractures surrounding the funnel that were observed in satellite images. Producing tension fractures requires materials with higher cohesion. Instead, the concentric ring patterns observed in analogue modeling are attributed to surface deformation caused by local, gravity-driven collapse. Moreover, surface depression during the early stage of dome subsidence may also have resulted from lava deflation28. Since the dry and brittle material cannot simulate the cooling and contraction of emplaced lava, the depth of the depression attributable to the deflation remains uncertain.

Comparison of analogue experiments and remote sensing observation

We compared the analogue experiment results with satellite and drone observations to evaluate their similarities and discrepancies. The extrusion experiments produced a Peléan-style sand dome distinguished by a flat summit and steep talus aprons (Fig. 7j). By contrast, satellite observations reveal a flat, pancake-shaped extrusion that lacks prominent surface textures and talus accumulation (Fig. 3a). This apparent discrepancy is primarily attributable to the inherent limitations of the analogue materials. The granular sand used in our experiments has been proven to be more suitable for simulating high-viscosity dome extrusions. Additional factors contributing to these discrepancies are outlined and discussed below.

First, the initial lava dome may have been destroyed by the eruption. The satellite dataset spans 2 months prior to and 1 month after the 10 December 2022 eruption, leaving a 3-month observational gap during which dome extrusion could not be confirmed. A small-volume dome may have formed above the conduit and subsequently been destroyed by the 10 December 2022 eruption. The flat surface shown in satellite imagery (Fig. 2b) and drone photographs (Fig. 5a) likely represents mixed deposits of lava fragments, tephra, and pyroclastic materials. This interpretation may explain the absence of characteristic surface textures of lava domes1,4,5,112. The hot northern deposits are interpreted as probable dome remnants and incandescent ejecta from a minor explosion on 26 January 2023. Furthermore, the circular thermal anomaly may delineate the upper extent of the hot conduit (Fig. 5c), consistent with previous estimates of conduit position and diameter31 (Fig. 2d).

Second, the lava dome may have begun to subside shortly after emplacement. Assume the dome was not destroyed by the eruption but instead buried beneath eruptive material, then nearly 1 month after the eruption, the extruded lava may have subsided at the conduit site. Our analogue experiments demonstrate dome-wide subsidence during the early down-sag stage (Fig. 6d), preceding the formation of a central depression. A steep deposit edge (~30°-50°) visible in the profile resembles talus slopes and is interpreted as the dome margin (Fig. 4). Based on this geometry, we inferred the height of the undeformed dome (Fig. 4).

Third, lava extrusion was effusive. Although the extruded lava body may be buried beneath eruptive deposits, topographic change maps reveal a flat, pancake-shaped extrusion with flow-like surface patterns indicative of effusive emplacement (Fig. 3a). The extrusion body appears sub-circular, consistent with analog experiments where dome morphology was largely influenced by crater walls and local topography (Fig. 7b). This morphology resembles the term ‘low lava dome’ or ‘axisymmetric dome’, both characterized by low height-to-diameter ratios and smooth profiles3,4. Such domes are typically associated with low-viscosity basaltic andesite to andesite compositions and high extrusion rates relative to cooling rates4. Predominant examples with comparable morphologies have been observed at Lascar6,113, Popocatépetl8,9, Cleveland12,13, Shinmoe-dake28,114, Mount Agung40, and Nevado del Ruiz40. In these examples, concentric textures and pressure ridges are commonly well discernible on the dome surface, attributed to cooling contraction29,114 and crater topography8,40. These features differ from the concentric patterns caused by surface stretching and lateral spreading, which are typical of Peléan-type domes in nature and sand domes in our experiments.

Satellite data show a funnel-shaped depression (~40° slope) that formed during the post eruptive stage (Fig. 3b). Subsidence analogue experiments reproduced a similar funnel geometry (~35°-40° slope; Fig. 7l). In both satellite imagery (Fig. 3c) and analogue experiments (Fig. 7d), the funnel center shifted toward the southeast inner crater wall. A fundamental question is whether the funnel formed through subsidence or explosive excavation. The volume of newly added material between 01 October 1 2022 and 25 January 2023 was estimated at ~1.47 × 105m3. Thereafter, the removed volume was ~0.8 × 105m3, nearly half of the extruded material was lost. Apart from increased northern deposits, estimated ~0.11 × 105m3 (Supplementary Table 4), no additional substantial amounts of explosive ejecta were identified within the inner crater or on the upper crater terrace. Crucially, the funnel lacks morphological features typical of explosion craters, such as ejecta rims or tephra rings, suggesting that explosive excavation was not the dominant process115. Instead, thermal (Fig. 5a) and drone (Fig. 5c) imaging show inwardly radiating streaks interpreted as mass-wasting features providing further evidence supporting the subsidence-driven mechanism. Drone photograph shows distinct concentric ring fractures encircling the funnel margin (Fig. 5a). Similar concentric fractures were documented during previous lava dome collapse phases at Lascar6. These fractures are interpreted as surface expressions of deeper fault systems beneath the dome or crater floor that accommodated piston-like subsidence, in great agreement with our experimental results.

Conceptual model and applications

Lascar volcano is characterized by cyclic behavior over recent decades, involving repeated episodes of dome construction and deconstruction, persistent degassing, and abrupt explosive activity of varying magnitudes. Its high altitude and deep crater geometry pose challenges for in situ observation. We monitored lava emplacement and associated morphological changes in real time using satellite photogrammetry at Lascar. Through analogue experiments, we demonstrate that the initially extruded material subsided and drained back into the conduit, producing a localized funnel-shaped depression. Building on these insights, we propose a conceptual model of viscous dome extrusion and funnel formation within deep craters, which may be applicable to other dome-building volcanic systems (Fig. 8; conceptual model of flat surface see Supplementary Fig. 7).

During dome extrusion from the conduit, new material rises along outward-dipping shear faults initiated at the conduit edge. The extruded material spreads laterally outward from the center, oversteepening and sliding down the dome flanks to establish talus deposits around the dome base. The dome construction phase (Fig. 8a) is primarily driven by continuous extrusion of new material, progressively burying older material beneath expanding talus. The slope of the dome flanks is controlled by the angle of repose of the talus material, typically ranging from ~35° to 40°. Concentric deformation patterns on the dome surface result from the outward lateral spreading of surface material. The dome deconstruction phase (Fig. 8b) is marked by the formation of a gradually deepening and enlarging funnel at the dome top. This developing funnel is subject to gravitational instability, driving inward slumping and landslides along its slopes. Dome subsidence behaves as a conical, piston-like subsidence, accommodated by movement along inward-dipping ring faults, which manifest at the surface as concentric fractures encircling the funnel. The development of outward- and inward-dipping faults during both extrusion and subsidence defines the deformation zone and enlarges the surface deformation. Accordingly, the position and extent of dome surface deformation can be used to infer the geometry of the underlying feeding conduit. Pre-existing topography and axisymmetric crater walls influence advance paths and the final morphology, resulting in off-center growth and the formation of a sub-circular, asymmetric dome (Fig. 8a). These topographic controls also affect the orientation of shear faults, which tend to develop asymmetrically. In contrast, during the subsidence phase, the funnel and associated faults exhibit axisymmetric geometry (Fig. 8b).

A similar dome growth sequence was documented at Colima during the 2007-2009 dome extrusion episode10. Dome growth initiated with lava extrusion onto a flat crater floor, forming a truncated cone. As the dome evolved, the cooled solid carapace brecciated and accumulated as talus at its base. Hot rockfall debris sourced from the summit continually slid down the flanks, expanding the talus apron, which exhibited slopes of ~38°-44°. At later stages, the dome developed a flat, circular top with a substantial granular talus apron. These stationary talus deposits stabilized the structure by buttressing the viscous dome core, increasing resistance to lateral spreading and facilitating vertical growth. The growth manner of the Colima dome bears a strong resemblance to the sand dome described in our experiments, with both natural and experimental cases emphasizing the role of the talus collar in constraining dome geometry and stability. A comparable fault pattern evolution was observed at Soufriére Hills during the 1995-1998 dome extrusion event5, where new lava was extruded onto the dome surface in a stick-slip manner along shear faults sourced from the conduit walls. These shear bands propagated either vertically, producing spines, or sub-horizontally, forming shear lobes.

The subsidence mechanism observed in analogue experiments correlates closely with natural examples. At Popocatépetl, dome subsidence is marked by the formation of a central circular pit (~23-47 m in diameter), which occasionally evolves into a cratered lava dome that reflects the geometry of the underlying conduit116. Concentric fractures commonly develop on the dome surface to accommodate downward sagging. As the pit deepens through piston-collapse structures, the inner crater progressively enlarges, driven by gravitational instability of the inner crater walls9. Similarly, subsidence of the Cleveland dome begins with the appearance of a slight depression at the summit, which gradually widens and deepens. The process is characterized by the presence of ring fractures encircling the depression33,117. Subsidence eventually causes nearly the entire center portion of the dome to collapse into the conduit, leaving a donut-like structure in which the remaining dome rims a deep pit (~20-40 m in diameter). In contrast to the cooled funnel at Lascar, the central pit of the Cleveland donut dome remains thermally active with temperatures exceeding 600 °C, indicative of an open volcanic conduit with sustained thermal output118. In the case of Popocatépetl and Celevland, short-term dome growth-collapse cycles have been interpreted as buoyancy-driven rise and fall of the magma column in the upper conduit8,9,13.

At Lascar, dome subsidence and funnel formation may have resulted from foam collapse in the upper conduit, initiating the drain-back of the dome or crater floor into the conduit6. As demonstrated by satellite observations in this study, this process can occur rapidly-potentially within a few days. Thermal satellite data indicate that no thermal anomalies were detected on the crater floor after funnel formation (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the area remained quiescent until the last data acquisition. The cooled and solidified funnel may have formed a plug at the top of the magma conduit, resulting in temporary thermal sealing, as shown on infrared drone imagery (Fig. 5d). Intensive snowfall may have accelerated the cooling of surface materials to some extent (Supplementary Fig. 1). The subsequent disappearance of thermal anomalies most likely reflects the lack of sustained magma supply within the deep plumbing system. In the absence of continued magma input, thermal anomalies associated with lava or lava domes tend to diminish rapidly119. The thermal signatures of the 2022-2023 lava emplacement event stand in marked contrast to the persistent crater floor-centered thermal anomalies and vigorous degassing that have characterized Lascar in recent years31,75. These comparisons imply that distinct mechanisms of magma withdrawal in conduit operate in volcanic systems, and the interplay among these mechanisms requires further investigation.

In this study, we integrated satellite and drone observations with laboratory analogue experiments to investigate lava emplacement dynamics at Lascar volcano. Photogrammetric processing of stereo or tri-stereo satellite imagery proved crucial for accurate and effective monitoring during eruptive crises. Despite factors limiting spatial and temporal resolution, such as shadow effects and the absence of ground control points, the resulting orthomosaics, DEMs or point clouds were sufficient to capture and present real-time topographic changes. Analogue experiments designed to replicate natural processes helped to explain the mechanisms governing morphological evolution. The use of 3D printing technology achieved a closer representation of natural terrain morphology, thereby making analogue processes more realistic. Lava dome extrusion and collapse often developed rapidly, while experimental modeling helped fill gaps in remote sensing observations and complemented the deformation processes. Our experiments reproduced the complete sequence of dome extrusion followed by subsidence from the same conduit, including the formation of a funnel-shaped depression that closely resembled satellite observations. Surface concentric fractures were shown to be mechanically linked to subsurface structures, accommodating piston-like sagging of the crater floor. Both topographic and experimental findings support a drain-back mechanism and delineate upper conduit conditions. Our model provides valuable insights into shallow conduit processes responsible for transient magma extrusion and withdrawal, with broader implications for lava dome evolution in other volcanic systems. Historical and recent dome extrusions at Lascar have often been associated with explosive activity and tephra ejected beyond the crater rim. In contrast, the subsequent funnel-shaped subsidence occurred deep within the crater during a period of quiescence, and might not have been noticed by nearby residents and tourists. Therefore, the design and implementation of laboratory analogue modeling based on remote sensing geodetic measurements represent a practical and comprehensive approach for understanding volcanic behavior, predicting future activity, and mitigating potential hazards.

Methods

Photogrammetric processing of satellite and drone data

We acquired a series of cloud-free Pléiades-1A tri-stereo images on 01 October 2022, 25 January 2023, and 22 February 2023, along with a stereo pair acquired on 25 October 2023, for photogrammetric processing. This dataset covers the entire period of lava emplacement at Lascar volcano. We processed the panchromatic band at 0.5 m spatial resolution using Agisoft Metashape (v2.1.0). Metashape is based on a photogrammetric algorithm and supports the rational polynomial coefficient (RPC) model. Among all the datasets, the 01 October 2022 satellite image exhibited the highest quality, with no snow or gas obscuring the summit, and was assigned as the reference dataset. From this dataset, we generated an orthomosaic (0.5 m/pixel) and a digital elevation model (DEM; 1 m/pixel) from the reference dataset. We then selected 20-30 evenly distributed ground control points (reference GCPs) over the reference orthomosaic and DEM to guide the processing of the remaining Pléiades images. Preliminary alignment was achieved by registering the other Pléiades images relevant to the reference dataset. The tri-stereo triplets and stereo pairs produced optical orthomosaics at 0.5 m spatial resolution and dense point clouds120 (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

We conducted two drone surveys at Lascar on 01 February 2023 and 26 February 2023, respectively. Drones were launched from the southern flank base (67°43’50"W, 23°21’19"S; 4881 m a.s.l.), ascending a vertical distance of ~1 km and successfully flew over the active crater to capture valuable images (Fig. 1b). On 01 February 2023, we employed a DJI Matrice 30T RTK quadcopter equipped with a DJI FPV camera and infrared sensor. On 26 February 2023, we utilized a DJI Mavic 3T quadcopter equipped with a 4/3 CMOS optical camera and an M3T thermal imaging camera. Together, the two surveys collected 320 optical (4000 × 3000 pixels) and 320 thermal infrared images (640 × 512 pixels). Because of substantial shadowing and intense degassing within the inner crater, most optical images were of low quality and insufficient for generating a reliable 3D model. We therefore processed only the infrared thermal imagery using the Structure-from-Motion (SfM) approach in Agisoft Metashape. Position accuracy relied solely on the built-in RTK module. The resulting thermal orthomosaic120 achieved a spatial resolution of 75 cm/pixel. For the purpose of spatial analysis, we selected two near-nadir view optical images with the least gas obstruction from both survey dates. To integrate the drone data with the Pléiades dataset, we georeferenced optical drone images and thermal orthomosaics using reference GCPs in ArcGIS Pro (v3.3) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

It’s worth noting that thermal radiation measurements are affected by numerous factors, including the emissivity and reflectivity of the target object, the viewing angle and flight height of the drone, and environmental conditions such as solar radiation, atmospheric transmittance, humidity121. Our thermal infrared drone data were acquired during the daytime and are subject to intensive degassing. Consequently, the measured apparent temperatures are underestimated and should be treated with caution31,122. Nevertheless, thermal anomalies at the crater floor remained notable compared to the surrounding area, providing a useful reference for relative comparison.

Point cloud alignment, differencing and volume change

We aligned the Pléiades-derived point clouds using the fine registration (ICP) tool in CloudCompare (v2.13.2). To reduce processing time, we segmented and aligned only the summit area. The point cloud from 01 October 2022 contained the least points missing and was designated as the reference point cloud. Subsequently, we registered the other point clouds to the reference point cloud successively. The root mean square (RMS) errors output by CloudCompare of each alignment are listed in Supplementary Table 2. To quantify morphological changes, we conducted point cloud differencing analysis using the M3C2 algorithm based plugin in CloudCompare. By this, we obtained the difference between successive point clouds (Fig. 3a, b and c) and a cumulative change map (Fig. 3d) with associated RMS errors (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, we computed significant change maps to verify that the detected changes represent real morphological changes (Supplementary Fig. 4). We considered the M3C2 distances are significant when the distance is at or above the 95% confidence interval123. Finally, we computed volumetric changes within the inner crater utilizing the 2.5D volume tool in CloudCompare (Supplementary Table 3).

Analogue experiment set up

We designed a series of analogue experiments to simulate the extrusion and withdrawal of materials from the same conduit (Fig. 1d). We attached a rigid pipe (15 cm long, 4 cm in diameter) beneath a table with a matching 4 cm diameter hole and connected a piston inside the pipe to a motor. The motor regulated the velocity and direction of piston motion and operated at a fixed actuation rate of 25 Hz for all experiments. Upward piston motion pushed material out of the pipe onto the table surface, whereas downward motion caused extruded material to fall back into the pipe. We conducted all experiments under controlled laboratory conditions with constant temperature and humidity. To assess the influence of crater topography on extrusion and subsidence morphologies, we extruded materials onto two types of surfaces: a flat horizontal plate and a 3D-printed mold.

We used a drone-derived point cloud acquired on 11 February 2020 from previous work to present the pre-emplacement topography31. We subsampled the point cloud to a spatial resolution of 1 m and generated a polygonal surface in CloudCompare, and expanded the polygon surface and closed its bottom to create a printable 3D object in Blender (v3.6). The 3D printing was carried out at Wissenschaftsladen Potsdam e.V. using a Creality 10s Pro printer. The print configuration was prepared in Ultimaker Cura (v4.3) with the following parameters: 1 mm bottom and top layer thickness, 3 mm wall thickness, 25% infill density, and 50 mm/s print speed. Polylactic acid (PLA) was used as the printing material, which has high mechanical strength to provide sufficient structural rigidity of the crater walls during the experiments. A circular hole with a diameter of 4 cm was opened at the 3D mold base, corresponding proportionally (1:100) to the estimated location and diameter of the underlying conduit31.

In the flat topography experiment, we placed a glass plate vertically through the center of the table opening. In the 3D topography experiment, we divided the 3D mold into two parts along the N-S axis and attached one half onto the glass plate. We sealed the gap between the mold and glass with silicone to prevent material leakage. We employed two Nikon digital cameras to record the experiments simultaneously at 10 second intervals. One camera was positioned vertically above the conduit to capture surface deformation in map view, while the second camera was placed in front of the glass plate to trace internal displacement in section view. Material was extruded on both sides of the glass during the recording. To maintain an unobstructed section view, we swept away the extruded material continuously from one side of the glass.

Analogue materials and scaling

We used dry quartz sand (well-rounded, grain size 100-400 μm) as analogue material124. To enhance visual contrast for digital image correlation analysis, we mixed a small amount of black-dyed sand into the bulk material125. Granular materials such as quartz sand are commonly used in scaled analogue modeling to simulate brittle deformation in the upper crust111,126,127,128. The quartz sand utilized in our experiments has a bulk density of 1410-1235 kg/m−3, a cohesion of 13 Pa, and a friction coefficient of 0.48129. The internal friction angle of typical granular materials ranges from 35° to 41°126,127.

A proper scaling of analogue experiments is intended to be geometrically, kinematically, and dynamically similar to natural prototypes54,55. Granular sand is a brittle-dominant material that exhibits frictional-plastic behavior and fails according to the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion126. The deformation of brittle materials is time-independent and is primarily governed by cohesion and the angle of internal friction130. The angle of internal friction (ϕ) is a dimensionless quantity that depends on the analogue material and should be comparable to that of natural rocks130. For natural igneous rocks, the angle of internal friction typically ranges between 30° and 40°64,126. We followed the scaling principles outlined by Ramberg55 to downscale our analogue models. The cohesion of the brittle material (τm) has the dimension of stress and needs to be scaled relative to the cohesion of the natural prototype (τn) by the same factor as the stress ratio (σ*): τm = σ*τn (1). The stress ratio (σ*) is defined as: σ* = ρ*g*h* (2), where ρ* is the density ratio, g* is the gravity ratio, and h* is the length ratio of the model, respectively. The density of natural igneous rock131 typically ranges from 2000-2700 kg/m−3. The granular quartz sand used in our experiments has a bulk density of ~1700 kg/m−3, yielding a density ratio (ρ*) of 0.5107,132. Since the experiments were conducted under a constant Earth’s gravitational field, g* = 1. The model conduit (pipe) has a fixed diameter of 4 cm. According to the estimated minimum conduit diameter of 40 m at Lascar31, the corresponding length ratio h* = 1 × 10−3, such that 1 cm in the model represents 10 m in nature. Accordingly, the stress ratio is calculated to σ* = 5 × 10−4, indicating that the analog models are ~5000 times weaker than the natural system.

2D DIC analysis

We processed the recorded time-lapse image sequences using the 2D-DIC (2-dimensional digital image correlation) algorithm implemented in LaVision DaVis (v10.0.5). The 2D-DIC technique is an effective method for detecting in-plane displacements and quantifying strain133. It operates by matching identical pixels between two sequential images before and after deformation134. In DaVis, this is accomplished by searching and matching pixel patterns within designated subset windows that shift across the entire image. We performed multiple passes with decreasing window size from 128 × 128 px (50% overlap) to 24 × 24 px (75% overlap). The outputs included displacement vectors and displacement fields. To visualize the shear zones during deformation, we computed vorticity from the displacement fields. Vorticity is defined as the rotation direction associated with the localized shearing of sand grains135, which serves as an indicator of strain localization and has been successfully applied in previous analog modelings66,67.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Photogrammetric datasets of Pléiades satellite and drone surveys are available via the Zenodo data repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17122265. Time-lapse video recordings of the analogue experiments are available via the Zenodo data repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17399571.

References

Fink, J. & Anderson, S. Lava Domes and Coulees (Academic Press, 2000).

Calder, E. S., Lavallée, Y., Kendrick, J. E. & Bernstein, M. Lava dome eruptions. In The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (Second Edition), (ed. Sigurdsson, H.) 343–362 (Academic Press, 2015).

Blake, S. Viscoplastic models of lava domes. In Lava Flows and Domes: Emplacement Mechanisms and Hazard Implications, (ed. Fink, J.) 88–126 (Springer, 1990).

Fink, J. H. & Griffiths, R. W. Morphology, eruption rates, and rheology of lava domes: Insights from laboratory models. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 103, 527–545 (1998).

Watts, R., Herd, R., Sparks, R. & Young, S. Growth patterns and emplacement of the andesitic lava dome at soufrière hills volcano, montserrat. Geol. Soc. London Memoirs 21, 115–152 (2012).

Matthews, S. J., Gardeweg, M. C. & Sparks, R. The 1984 to 1996 cyclic activity of lascar volcano, northern chile: cycles of dome growth, dome subsidence, degassing and explosive eruptions. Bull. Volcanol. 59, 72–82 (1997).

Gardeweg, M., Sparks, R. & Matthews, S. Evolution of lascar volcano, northern chile. J. Geol. Soc. 155, 89–104 (1998).

Gómez-Vazquez, A., De la Cruz-Reyna, S. & Mendoza-Rosas, A. The ongoing dome emplacement and destruction cyclic process at popocatépetl volcano, central mexico. Bull. Volcanol. 78, 58 (2016).

Valade, S. et al. Lava dome cycles reveal rise and fall of magma column at popocatépetl volcano. Nat. Commun. 14, 3254 (2023).

Hutchison, W., Varley, N., Pyle, D. M., Mather, T. A. & Stevenson, J. A. Airborne Thermal Remote Sensing of the Volcán de Colima (Mexico) Lava Dome From 2007 to 2010. In Remote Sensing of Volcanoes and Volcanic Processes: Integrating Observation and Modelling. (Geological Society of London, 2013).

Walter, T. R. et al. Imaging the 2013 explosive crater excavation and new dome formation at volcán de colima with terrasar-x, time-lapse cameras and modelling. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 369, 224–237 (2019).

Wang, T., Poland, M. P. & Lu, Z. Dome growth at mount cleveland, aleutian arc, quantified by time series terrasar-x imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10,614–10,621 (2015).

Werner, C. et al. Magmatic degassing, lava dome extrusion, and explosions from mount cleveland volcano, alaska, 2011-2015: insight into the continuous nature of volcanic activity over multi-year timescales. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 337, 98–110 (2017).

Melnik, O. & Sparks, R. Nonlinear dynamics of lava dome extrusion. Nature 402, 37–41 (1999).

Jaupart, C. & Allègre, C. J. Gas content, eruption rate and instabilities of eruption regime in silicic volcanoes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 102, 413–429 (1991).

Sparks, R. Causes and consequences of pressurisation in lava dome eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 150, 177–189 (1997).

Voight, B. et al. Magma flow instability and cyclic activity at soufriere hills volcano, montserrat, british west indies. Science 283, 1138−1142 (1999).

Melnik, O., Sparks, R., Costa, A. & Barmin, A. A. Volcanic eruptions: cyclicity during lava dome growth. In Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science, (ed. Meyers, R.) (Springer, 2021).

Ogburn, S., Loughlin, S. & Calder, E. The association of lava dome growth with major explosive activity (vei4): Domehaz, a global dataset. Bull. Volcanol. 77, 1–17 (2015).

Sheldrake, T., Sparks, R., Cashman, K., Wadge, G. & Aspinall, W. Similarities and differences in the historical records of lava dome-building volcanoes: Implications for understanding magmatic processes and eruption forecasting. Earth Sci. Rev. 160, 240–263 (2016).

Alidibirov, M. & Dingwell, D. B. Magma fragmentation by rapid decompression. Nature 380, 146–148 (1996).

Voight, B. & Elsworth, D. Instability and collapse of hazardous gas-pressurized lava domes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 1−4 (2000).

Calder, E., Luckett, R., Sparks, R. & Voight, B. Mechanisms of lava dome instability and generation of rockfalls and pyroclastic flows at soufriére hills volcano, montserrat. In The Eruption of Soufriére Hills Volcano, Montserrat from 1995 to 1999, 343–362 (Geological Society of London, 2002).

Voight, B. Structural stability of andesite volcanoes and lava domes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 358, 1770 (2000).

Ball, J. L., Stauffer, P. H., Calder, E. S. & Valentine, G. A. The hydrothermal alteration of cooling lava domes. Bull. Volcanol. 77, 1–16 (2015).

Sparks, R. & Young, S. The eruption of soufriére hills volcano, montserrat (1995-1999): overview of scientific results. In The Eruption of Soufriére Hills Volcano, Montserrat from 1995 to 1999 (Geological Society of London, 2002).

Voight, B. et al. The 26 December (Boxing Day) 1997 sector collapse and debris avalanche at soufriére hills volcano, Montserrat. In The Eruption of Soufriére Hills Volcano, Montserrat from 1995 to 1999 (Geological Society of London, 2002).

Sato, H. et al. Viscosity of andesitic lava and its implications for possible drain-back processes in the 2011 eruption of the Shinmoedake volcano, Japan. Earth Planets Space 65, 623–631 (2013).

Salzer, J. T. et al. Evaluating links between deformation, topography and surface temperature at volcanic domes: results from a multi-sensor study at volcán de Colima, Mexico. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 479, 354–365 (2017).

Bluth, G. J. & Rose, W. I. Observations of eruptive activity at Santiaguito volcano, Guatemala. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 136, 297–302 (2004).

Ai, L. et al. Crater morphology, nested ring structures, and temperature anomalies studied by unoccupied aircraft system data at Lascar volcano, northern Chile. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 439, 107840 (2023).

Sahetapy-Engel, S. & Harris, A. J. Thermal structure and heat loss at the summit crater of an active lava dome. Bull. Volcanol. 71, 15–28 (2009).

McGimsey, R. G., Maharrey, J. Z. & Neal, C. A. 2011 Volcanic Activity In Alaska: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory. https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2014/5159/pdf/sir2014-5159.pdf (2014).

Ordoñez, M., Laverde, C. & Battaglia, M. The new lava dome growth of Nevado del Ruiz (2015-2021). J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 430, 107626 (2022).

Major, J., Dzurisin, D., Schilling, S. & Poland, M. Monitoring lava-dome growth during the 2004-2008 Mount St. Helens, Washington, eruption using oblique terrestrial photography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 286, 243–254 (2009).

Diefenbach, A. K., Bull, K. F., Wessels, R. L. & McGimsey, R. G. Photogrammetric monitoring of lava dome growth during the 2009 eruption of Redoubt volcano. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 259, 308–316 (2013).

Walter, T. R. et al. Dome growth and coulée spreading controlled by surface morphology, as determined by pixel offsets in photographs of the 2006 Merapi eruption. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 261, 121–129 (2013).

Diefenbach, A. K., Crider, J. G., Schilling, S. P. & Dzurisin, D. Rapid, low-cost photogrammetry to monitor volcanic eruptions: an example from Mount St. Helens, Washington, ISA. Bull. Volcanol. 74, 579–587 (2012).

Thiele, S. T., Varley, N. & James, M. R. Thermal photogrammetric imaging: a new technique for monitoring dome eruptions. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 337, 140–145 (2017).

Andaru, R., Rau, J.-Y., Syahbana, D. K., Prayoga, A. S. & Purnamasari, H. D. The use of UAV remote sensing for observing lava dome emplacement and areas of potential lahar hazards: an example from the 2017-2019 eruption crisis at Mount Agung in Bali. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 415, 107255 (2021).

Moussallam, Y. et al. Monitoring and forecasting hazards from a slow growing lava dome using aerial imagery, tri-stereo pleiades-1a/b imagery and PDC numerical simulation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 564, 116906 (2021).

Wooster, M., Kaneko, T., Nakada, S. & Shimizu, H. Discrimination of lava dome activity styles using satellite-derived thermal structures. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 102, 97–118 (2000).

Coppola, D. et al. Thermal remote sensing for global volcano monitoring: Experiences from the Mirova system. Front. Earth Sci. 7, 362 (2020).

Pallister, J. S. et al. Merapi 2010 eruption-chronology and extrusion rates monitored with satellite radar and used in eruption forecasting. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 261, 144–152 (2013).

Dualeh, E. et al. Rapid pre-explosion increase in dome extrusion rate at La Soufrière, St. vincent quantified from synthetic aperture radar backscatter. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 603, 117980 (2023).

Hale, A. & Wadge, G. Numerical modelling of the growth dynamics of a simple silicic lava dome. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2003 (2003).

Buisson, C. & Merle, O. Numerical simulation of strain within lava domes. J. Struct. Geol. 26, 847–853 (2004).

Hale, A. Lava dome growth and evolution with an independently deformable talus. Geophys. J. Int. 174, 391–417 (2008).

Hale, A. J. & Wadge, G. The transition from endogenous to exogenous growth of lava domes with the development of shear bands. J. Volcanol. Geothe. Res. 171, 237–257 (2008).

Hale, A., Calder, E., Wadge, G., Loughlin, S. & Ryan, G. Modelling the lava dome extruded at soufrière hills volcano, Montserrat, August 2005-May 2006: Part I: Dome shape and internal structure. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 187, 53–68 (2009).

Hale, A., Calder, E., Loughlin, S., Wadge, G. & Ryan, G. Modelling the lava dome extruded at soufrière hills volcano, Montserrat, August 2005-May 2006: Part II: rockfall activity and talus deformation. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 187, 69–84 (2009).

Husain, T., Elsworth, D., Voight, B., Mattioli, G. & Jansma, P. Influence of extrusion rate and magma rheology on the growth of lava domes: Insights from particle-dynamics modeling. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 285, 100–117 (2014).

Harnett, C. E., Thomas, M. E., Purvance, M. D. & Neuberg, J. Using a discrete element approach to model lava dome emplacement and collapse. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 359, 68–77 (2018).

Hubbert, M. K. Theory of scale models as applied to the study of geologic structures. GSA Bull. 48, 1459–1520 (1937).

Ramberg, H. Gravity, Deformation, and the Earth's Crust: In Theory, Experiments, and Geological Application, Vol. 452 (Academic Press, 1981).

Balmforth, N. J., Burbidge, A., Craster, R., Salzig, J. & Shen, A. Visco-plastic models of isothermal lava domes. J. Fluid Mech. 403, 37–65 (2000).

Huppert, H. E., Shepherd, J. B., Haraldur Sigurdsson, R. & Sparks, S. J. On lava dome growth, with application to the 1979 lava extrusion of the soufriére of St. vincent. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 14, 199–222 (1982).

Buisson, C. & Merle, O. Experiments on internal strain in lava dome cross sections. Bull. Volcanol. 64, 363–371 (2002).

Griffiths, R. W. & Fink, J. H. Effects of surface cooling on the spreading of lava flows and domes. J. Fluid Mech. 252, 667–702 (1993).

Fink, J. H. & Bridges, N. T. Effects of eruption history and cooling rate on lava dome growth. Bull. Volcanol. 57, 229–239 (1995).

Griffiths, R. W. & Fink, J. H. Solidifying Bingham extrusions: a model for the growth of silicic lava domes. J. Fluid Mech. 347, 13–36 (1997).

Lyman, A. W., Koenig, E. & Fink, J. H. Predicting yield strengths and effusion rates of lava domes from morphology and underlying topography. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 129, 125–138 (2004).

Buisson, C. & Merle, O. Influence of Crust Thickness on Dome Destabilization. (Geological Society of America, 2005).

Donnadieu, F. & Merle, O. Experiments on the indentation process during cryptodome intrusions: New insights into Mount St. Helen's deformation. Geology 26, 79–82 (1998).

Závada, P., Kratinová, Z., Kusbach, V. & Schulmann, K. Internal fabric development in complex lava domes. Tectonophysics 466, 101–113 (2009).

Zorn, E. U., Walter, T. R., Heap, M. J. & Kueppers, U. Insights into lava dome and spine extrusion using analogue sandbox experiments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 551, 116571 (2020).

Walter, T. R. et al. Influence of conduit and topography complexity on spine extrusion at Shiveluch volcano, Kamchatka. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 169 (2022).

Stern, C. R. Active Andean volcanism: its geologic and tectonic setting. Revista Geológica de Chile 31, 161–206 (2004).

Francis, P. & Rothery, D. Using the landsat thematic mapper to detect and monitor active volcanoes: an example from lascar volcano, northern chile. Geology 15, 614–617 (1987).

Gardeweg, M. & Medina, E. La erupción subpliniana del 19-20 de abril de 1993 del volcan Lascar, n de Chile. Acta 7th Congr Geol Chileno 7, 299–304 (1994).

Wooster, M. J. & Rothery, D. A. Thermal monitoring of Lascar volcano, Chile, using infrared data from the along-track scanning radiometer: a 1992-1995 time series. Bull. Volcanol. 58, 566–579 (1997).

Tassi, F. et al. The magmatic- and hydrothermal-dominated fumarolic system at the active crater of lascar volcano, northern Chile. Bull. Volcanol. 71, 171–183 (2009).

Menard, G. et al. Gas and aerosol emissions from Lascar volcano (northern Chile): Insights into the origin of gases and their links with the volcanic activity. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 287, 51–67 (2014).

González, C. et al. Heat and mass flux measurements using Landsat images from the 2000-2004 period, Lascar volcano, northern Chile. J. Volcanol. Geother. Res. 301, 277–292 (2015).

Gaete, A. et al. Processes culminating in the 2015 phreatic explosion at Lascar volcano, Chile, evidenced by multiparametric data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 377–397 (2020).

Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería de Chile (SERNAGEOMIN). Reporte Especial de Actividad Volcánica (REAV), Región de Antofagasta, Volcán Láscar, 10 De Diciembre De 2022 https://rnvv.sernageomin.cl/volcan-lascar/ (2022).

Global Volcanism Program. Report on Lascar (Chile). https://volcano.si.edu/showreport.cfm?wvar=GVP.WVAR20250312-355100 (2023).

Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería de Chile (SERNAGEOMIN). Reporte Especial de Actividad Volcánica (REAV), Región de Antofagasta, Volcán Láscar, 31 De Enero de 2023 https://rnvv.sernageomin.cl/volcan-lascar/ (2023).

Gouhier, M. et al. Cnes-esa satellite contribution to the operational monitoring of volcanic activity: The 2021 icelandic eruption of mt. fagradalsfjall. J. Appl. Volcanol. 11, 10 (2022).

Pedersen, G. B. et al. Volume, effusion rate, and lava transport during the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption: results from near real-time photogrammetric monitoring. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097125 (2022).

Bagnardi, M., González, P. J. & Hooper, A. High-resolution digital elevation model from tri-stereo Pleiades-1 satellite imagery for lava flow volume estimates at Fogo volcano. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 6267–6275 (2016).

Traglia, F. D., Fornaciai, A., Favalli, M., Nolesini, T. & Casagli, N. Catching geomorphological response to volcanic activity on steep slope volcanoes using multi-platform remote sensing. Remote Sensing 12, 438 (2020).

Proietti, C. et al. Towards a satellite-based approach to measure eruptive volumes at mt. ETNA using Pleiades datasets. Bull.Volcanol. 82, 35 (2020).