Abstract

Traditional wildfire fuel management faces critical barriers due to high cost, carbon emissions, and operational risks. While biochar technology offers a solution, the poor awareness of forest fuel biochar hinders its global implementation. Here we produced biochar from boreal and temperature forest surface fuels. Large-scale characterization revealed its composition, performance, and the chemical and molecular changes of the carbon components. The pyrolysis mechanism was clarified, and advanced analysis was integrated to predict functions and quantify the relationships between raw material, pyrolysis conditions, biochar properties, and functions. It was demonstrated that fuel biochar has important functions in mitigating greenhouse benefits, improving soil, and pollution control. The proposed conversion strategy enables permanent carbon dioxide sequestration of at least 383.61-712.18 kg per ton of fuel. We conclude that biochar represents an innovative alternative to conventional fuel management for more effective mitigation of both wildfires and climate warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consecutive record breaks in wildfires, particularly in boreal forests, have great adverse global impacts on climate change, ecosystems, and sustainable development1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and represent an environmental crisis that urgently needs to be addressed8,9. Based on the fundamental principles of fire, active fuel management helps to curb wildfire escalation10,11. However, the high cost and poor safety of traditional fuel regulation make fuel management difficult in large areas. Controlled burning (prescribed burning) and land clearing are widely used fuel regulation methods in many countries and areas, including America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia12,13, but controlled burning produces large amounts of toxic smoke, greenhouse gases (GHGs), and may also get out of control14,15. Fuel management is expensive, for example, between 2006 and 2015, U.S. Forest Service funding for hazardous fuel treatment totaled 3.2 billion USD16, and the budget was 321 million USD in 202317. The Natural Resources Canada has increased its budget by 147.5 million CAD for the “Wildfire Risk Management” project in the fiscal year 2023–2024. Hazardous fuels management is its core funding activity18. Therefore, urgent implementation of cost-effective and sustainable fuel management strategies is required globally.

Biochar provides a validated pathway for biomass waste valorization, with its preparation and properties extensively characterized over the past decade19,20,21,22,23. Studies confirm biochar’s multifunctional potential across industrial22,24,25,26, agricultural27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, and ecosystem sustainability applications20,23,28,29,33,35. Therefore, the production of forest fuels into biochar can not only directly mitigate or reduce wildfires by reducing fuel but also enable economic or ecological benefits from this previously unused biomass10,11. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has long proposed converting wildfire fuel to biochar20,36, however previous studies on forest biochar have predominantly focused on woody biomass (e.g., timber, sawdust)20,37,38,39,40 or non-specific leaf feedstocks, such as pine needles from the Himalayas41, northern India20, and the Congo Basin20, even in some studies, whether the material was wood or leaves was not specified42. This underscores a critical research gap: the poor awareness of forest surface fuel-derived biochar, hindering the optimization and global implementation of sustainable wildfire mitigation options.

This study addresses these gaps through four core contents: (1) comprehensive characterization of the performance and composition of forest surface fuel biochar, (2) clarify the pyrolysis mechanism, (3) predict functions and quantify the complex relationships between raw material components, pyrolysis conditions, biochar composition, properties, and functions, and (4) the benefits of biochar in mitigating GHG, replacing fossil fuels, improving soil, nutrient exchange, pollution control, and ecological restoration. Here, we used the surface fuels from temperate and boreal forests as experimental materials (Fig. 1a) to make a total of 60 biochar samples at pyrolysis temperatures of 300–700 °C durations of 1–3 h (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on the raw materials, the biochar samples were named as follows: biochar of Larix gmelinii (Rupr.) Kuzen (BCLg), biochar of Pinus sylvestris L. (BCPs), biochar of Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb. (BCQm), and Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr. (BCFm). Morphological characteristics of the surface fuels are shown in Fig. 1b, while their compositional differences are presented in Fig. 1c. The research content encompasses more than 50 indicators, such as the biochar composition and application performance, C composition, molecular characteristics of soluble organic carbon (SOC), pore properties, and pollutant adsorption capacity. The pyrolysis mechanism was discussed in detail, and the above indicators were explained and predicted through machine learning. The relationship between the indicators was quantified through structural equation modeling. Finally, the ecological benefits of forest surface fuel biochar were analyzed. This study fills the research gap of biochar for wildfire management and expands the application field of biochar. It has demonstrated the multiple benefits of biochar technology in mitigating wildfires, climate change, and economic and ecological sustainability, providing a more proactive and feasible option for global wildfire management.

Results

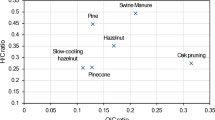

Pyrolysis of biochar elements, pH, and organic structure

The major elemental composition (C, H, O, and N) and ash content of biochar obtained at different pyrolysis temperatures exhibited significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The C content increased as the temperature increased from 300 °C to 500–600 °C, then decreased at 700 °C. The contents of N, H, and O all decreased with increasing temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Van Krevelen diagram (Fig. 2a) reflects the dehydrogenation and deoxygenation during pyrolysis32, and the polarity of biochar decreased significantly with the increasing temperature34,43 (Fig. 2b). A clear partition is formed between temperatures, both H and O contents decrease rapidly between 300–500 °C, while the decline slows down at 500–700 °C with a more pronounced reduction in H compared to O. Compared with the pyrolysis temperature, the retention time has a smaller impact on the atomic ratio, especially at 300–500 °C. However, at the same temperature, varying the retention time leads to changes in the O/organic C (Corg) molar ratio, suggesting that retention time affects the decarboxylation process32. Furthermore, there is a significant linear relationship between the O/C and H/C atomic ratios (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2c, d).

a Van Krevelen diagram of the biochar. Each arrow represents the direction of loss of a particular gas molecule during evolution. b Correlation between N/Corg and (O + N)/Corg molar ratio of biochar of different raw materials and biochar produced at different pyrolysis temperatures. c, d Univariate linear model and model collinearity test for H/C and O/C molar ratio of biochar from different raw materials. e, f Univariate linear model and model collinearity test for pH and ash% of biochar from different raw materials. The relative content of each functional group was calculated from the FT-IR absorbance values (g). Determination of the absolute content of acidic functional groups of BCLg (h), BCPs (i), BCQm (j), and BCFm (k) by Boehm titration. The error bar represents the standard deviation.

Surface fuels are weakly acidic (4 < pH < 6, Supplementary Fig. 3). The pH of all biochar produced at 300 °C is in the range of 7–9 (weakly alkaline) and increases significantly (p < 0.05) with the rising temperature, and the maximum pH value can reach 11–13 at 700 °C. Similar to the elemental ratio, there is also a significant linear relationship between pH and ash content (p < 0.001, Fig. 2e). It is observed during Boehm titration that there is a big loss of O-containing functional groups at high temperatures, just like the carboxyl groups of BCPs, BCQm, and BCFm (Fig. 2h–k). The infrared spectral features of biochar prepared at 200–250 °C do not differ significantly from those of the feedstocks44,45. The overall change trends of biochar functional groups were consistent: the types of functional groups decreased significantly at 300°C when aromatic and ketone structures began to form44. At 400 °C, accompanied by dehydrogenation, decarboxylation, and polysaccharide lysis reaction, most aliphatic compounds are completely pyrolysis46. Part of the lignin and aromatic ketone structure can be retained, while the degree of condensation of aromatic compounds increases. Temperature 500 °C is mainly accountable for the lignin decomposition, further development towards polycyclic aromatic structures46, and enhanced conjugated structure occupancy leading to a shift in the absorption band of aromatic C=O near lower wavelengths (redshift). At temperatures 600–700 °C, there are almost no absorption peaks, and it is hypothesized that graphene-like structures are generated (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3)47. These results further confirmed that positive feedback of biochar stability on pyrolysis temperature, and temperature 700 °C, makes biochar the most stable.

Application performance of biochar (Supplementary Fig. 5)

BCLg and BCPs (two coniferous fuels) had similar mass fractions and changing trends of available nitrogen and phosphorus, as did BCQm and BCFm (two deciduous fuels). Heating caused the original total dissolved salts of biochar to be pyrolyzed, and new salts are regenerated at high temperatures. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) maximum for the biochar appeared at 400 °C, then decreased from 500 to 600 °C, and finally rebounded at 700 °C. BCLg, BCQm, and BCFm exhibited good cation exchange (>1 mol kg−1). The higher heating values (HHV) and ash-free caloric value (AFCV) of BCLg, BCPs, BCQm were highest at a temperature of 600 °C and decreased at a temperature of 700 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5). The HHV of coniferous-char (21.58–26.45 MJ kg−1) is higher than that of broad-leaved-char (17.15–22.55 MJ kg−1).

Distribution of C elements in biochar (Fig. 3a)

In our study, the stable C content of the biochar (22.45%–54.27%) was much higher than that of their raw materials (8.26%–14.23%). And BCLg and BCPs (28.03%–54.27%) had more stable C than BCQm and BCFm (22.45%–46.08%), which can be attributed to higher lignin in conifers, resulting in a higher mass fraction of stable C in their biochar44,48. The labile C content of biochar (0.67%–26.42%) was lower than their raw material (14.82%–27.83%), and the content decreases with the increasing pyrolysis temperature and retention time. However, it rebounds at the temperature of 700 °C when the stable C and carbonate content displays the reversed trend versus temperature. This is similar to the trend of changes in organic structure, functional groups, and O/C and H/C molar ratios in biochar mentioned earlier.

Pyrolysis resulted in significant decreases in the SOC content of the biochar compared to their raw materials. At 300 °C, the SOC dropped from 12.75% to 2.03% (84.10% loss) for BCLg, from 11.54% to 0.45% (96.09% loss) for BCPs, from 18.52% to 1.93% (89.57% loss) for BCQm, and from 15.13% to 9.06% (40.15% loss) for BCFm. Further temperature increase to 700 °C resulted in near-complete depletion, with SOC contents falling below 0.2% and losses exceeding 98% for all materials. This exponential decrease in SOC with rising temperature demonstrates the high thermal sensitivity of biochar SOC, which aligns with previous findings30,49.

The three SOC components of biochar were continuously extracted through cold water (25 °C), hot water (80 °C), and weak alkali (0.05 M, 25 °C), named cold-water-soluble organic C (CCS), hot water-soluble organic C (CHS), and alkali-soluble organic C (CAS)50. The three SOC components decrease rapidly with the increase in temperature. For example, from 300 to 700 °C, the CCS, CHS, and CAS of BCLg drop from 0.88%, 0.70%, and 0.45%, respectively, to 0.01%, 0.03%, and 0.03%, decreasing by 98.50%, 95.51%, and 92.46%. This finding aligns with both the consensus from previous studies that all three SOC components are highly sensitive to temperature increases30,49, and the view proposed by Liu et al. that the sequentially extracted SOC components using water, hot water, and NaOH solution exhibit progressively increasing thermal stability and molecular weight50.

Biochar carbon sink (Fig. 3b)

To determine the amount of C that can be permanently and semi-permanently fixed per unit mass of forest surface fuels after pyrolysis, and given that half-life does not provide a specific value for C fixation, we constructed relatively conservative biochar stable and labile carbon sink yields by multiplying biochar yield by the stable C content and labile C content, respectively. For every 1-ton dry fuel consumed, the biochar can permanently fix 104.62–194.23 kg of C (383.61–712.18 kg CO2) and semi-permanently fix 4.68–148.96 kg of C (17.16–546.19 kg CO2). The maximum permanent carbon sink is provided by BCPs at 300 °C, 3 h. The labile carbon sink of biochar decreases rapidly as the temperature rises, stemming from a synergistic decrease in labile C content and yield. The rapid increase of stable C and rapid decrease in yield at temperatures of 300–400 °C resulted in large fluctuations in the carbon sink yield of biochar, which varied steadily in the range of 500–600 °C and decreased at 700 °C due to the further decrease in the yield and oxidization of the stable C.

Characteristics of soluble organic matter in biochar

The composition and chemical properties of SOC are susceptible to pyrolysis temperature. With the increase in thermal temperature, the abundance of colored soluble organic carbons (CSOC) continued to decline and was almost completely lost at 500 °C (Fig. 3c). The pyrolysis of plant components produced new SOC. Their aromaticity, hydrophobicity, molecular weight, degree of polymerization of benzene ring, and degree of conjugation with carbonyl groups, and structural complexity were positively correlated with temperature before 400 °C and negatively correlated with temperature after 400 °C (Fig. 3d–h, l). In contrast to the other three types of biochar, the aromaticity of CCS and CHS in BCLg increased again at 700 °C (Fig. 3d). Similar phenomena have been observed in previous studies on rice straw biochar, dairy manure biochar, and coconut shell biochar51,52. Cao et al. attributed this observation to the formation of phenolic compounds resulting from lignin depolymerization above 600 °C52. Furthermore, studies have also indicated that temperatures above 600 °C promote the formation of small aromatic compounds such as pyrolic and pyridinic structures in BCLg53, which further enhances the aromaticity of SOC components. These conjectures require validation through more advanced analytical techniques, such as Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry or Liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer.

The content of fluorescent soluble organic carbons and the proportion of aromatic amino acids also showed the same trend (Fig. 3i, j). The proportion of newborn SOC positively correlates with temperature (Fig. 3k). Three-dimensional-excitation-emission spectroscopy (3d-EES) further confirmed that the SOC of biochar at 300 °C and 400 °C was rich in humic-like and fulvic-like structures, their conjugation, aromaticity, and molecular weight increased at 400 °C. They originate from the thermal decomposition of cellulose and lignin54, which helps to increase soil fertility and absorb heavy metals50. These components in SOC disappeared at 500 °C and generated a small amount of stable protein-like structures. Extending the pyrolysis time led to an increase or decrease in SOC components. Still, it would not significantly change the composition and chemical properties of the material as temperature does55,56 (Fig. 3m, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7).

SEM and pore development of biochar

Figure 4a–h depicts the size distribution of pores of diameters 1–300 nm. It is noted that because of the limitation of the nitrogen adsorption test, the micropores selected only contain pores of 1–2 nm in this study. The pores of surface fuel biochar are dominated by mesopores of 2–12 nm, except for BCLg700 and BCQm600, when the pores are of micropores of 1–2 nm. These pores contributed 47.88%–89.57% of the specific surface area. The specific surface areas of biochar were 39.407–127.74 m2 g−1 (BCLg), 17.439–44.101 m2 g−1 (BCPs), 6.959–85.873 m2 g−1 (BCQm), and 20.275–134.66 m2 g−1 (BCFm).

Nitrogen adsorption isotherms (Fig. 4i–l) indicate that many slit-like pores were present in all biochar samples, which are consistent with the scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). The pore characteristics of biochar vary greatly among different raw materials. As the pyrolysis temperature increased, the particles of BCLg tended to be inhomogeneous, and the mesopores in the samples were lost during the pyrolysis process, and a considerable number of micropores were further produced at 700 °C. In contrast, BCPs produced some mesopores at 700 °C, while the particle size of the samples tended to homogenize. The number of mesopores in BCQm increased at 300–500 °C while the particle size was inhomogeneous, with a large number of micropores appearing at 600 °C and collapsing at 700 °C. Mesopores in BCFm increased and collapsed at the same temperatures.

Adsorption characteristics of heavy metals in aqueous solutions

Figure 5a shows that the forest fuel biochar has the best adsorption on Pb (Ⅱ), followed by Cd (Ⅱ), Zn (Ⅱ), and Cr (Ⅵ), and the least adsorption on As (Ⅴ), and BCFm has the best adsorption effect on Zn (Ⅱ), As (Ⅴ), Cd (Ⅱ), and Pb (Ⅱ). Supplementary Tables 5–7 provide detailed results of the adsorption models. The higher R2 of the Elovich model compared to the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models (Fig. 5b–f, Supplementary Tables 5–7) indicates that chemical adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces is the primary mechanism for metal ion adsorption by the biochar in this study57,58.

Contrary to the maximum experimental adsorption quantity, the saturated adsorption quantities (Qe) for the five ions estimated by the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models were greater for BCLg than for the other biochar (Supplementary Tables 5–7). This suggests that BCLg possesses the highest potential saturated adsorption capacity among the tested biochars. The lower total experimental adsorption capacity observed for BCLg could be attributed to the adsorption process not reaching full saturation under the given experimental conditions and timeframe, or potentially to a lower capacity associated with its specific heterogeneous surface diffusion pathways58,59. This discrepancy warrants further investigation.

The Intraparticle Diffusion Equation describes the complete process of metal ion transfer from the solution to the adsorption sites within the biochar particles. The first stage represents boundary layer diffusion or instantaneous surface adsorption, the second stage signifies intra-particle diffusion, and the third stage corresponds to the very slow approach to final equilibrium60. As shown in Supplementary Tables 5–7, the rate constant for the second stage (k₂) is considerably lower than that of the first stage (k₁). This clearly indicates that intra-particle diffusion is the rate-determining step for the overall adsorption process. We attribute this phenomenon to the presence of ink-bottle pores in the biochar structure. As indicated previously in the pore size analysis (Fig. 4i–l), the population of these ink-bottle pores increases with higher pyrolysis temperatures, thereby further impeding ion diffusion.

Prediction of biochar properties

The PCA results (Fig. 6a) suggested that biochar aggregated into three clusters. The biochar of the same temperature and same source tended to be close to each other; rising temperatures made the spacing of biochar of different feedstocks smaller. The pyrolysis temperature and raw material composition are the primary determinants of nearly all biochar properties, particularly ash content, C content, C composition, and application performance. The yield, elemental composition, C composition, certain application performances, and most functional group changes in biochar are predominantly influenced by pyrolysis temperature. The main components of raw materials primarily explained the ash content, C composition, application performance, and heavy metal ion adsorption capacity of biochar (Fig. 6b). The basic properties, C composition, and functional group content of biochar can effectively explain its application performance, such as calorific value, CEC, and carbon sink yield (88.41% <variance explained <98.05%, Fig. 6c–e). Additionally, the specific surface area and average pore diameter of biochar, and abundance of certain functional groups in biochar, were explained 87.01%–92.02% of the variation in heavy metal cation adsorption capacity (Fig. 6f, g).

a Three-dimensional principal component analysis (3d-PCA) is used to characterize similarities and dissimilarities in biochar. b The contribution of pyrolysis temperature and biomass feedstock composition (major elements, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content) to explain the differences in every attribute of biochar based on correlation and optimal multiple regression models. We investigated the correlation of all attributes with these values for each biochar sample and identified the main predictors. The size of the circle represents the importance of the variable (i.e., the proportion of explained variability calculated from multiple regression models and variance decomposition analyses, and the color represents the Spearman correlation. Random forest (RF) algorithm was used to rank the importance of the attributes that determine HHV (c), EC (d), CEC (e), and Zn (Ⅱ) (f), As (V) (g), Cr (Ⅵ) (h), Cd (Ⅱ) (i), and Pb (Ⅱ) (j) adsorbed respectively; percentage increment (mean square error, %IncMSE) were used to rank attributes (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001). APD average pore diameter, SA specific surface area, C&E Carboxyl & ester, PAr C–H polysubstituted aromatic C–H, MAr C–H monosubstituted aromatic C–H, Phhy phhydroxyl, Carb carboxyl, Lact lactonyl.

Discussion

The pyrolysis mechanism of biochar

The increase in C content at 600 °C and below reflects the rise in the carbonization degree of biochar. Higher pyrolysis temperatures lead to further cracking or oxidation of the generated stable C structure, resulting in the C content decreasing at 700 °C44. With increasing temperature, the content of elemental O and H decreases; the cause of such a phenomenon has been widely confirmed that the escape of water molecules from biomass is the main cause for the loss of O and H at lower temperatures61. Organic compounds of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin are cleaved at higher temperatures when the weaker -O and -H chemical bonds are broken. The loss of oxygen-containing functional groups leads to a further reduction of O and H61. There are two change patterns in the N content of biochar62: a part of the results showed that the N content decreased with increasing pyrolysis temperature, and our study supports this. Other studies found that the N content increased and then decreased with increasing temperature63,64. On the one hand, more stable N-containing raw materials (N-containing heterocyclic compounds and N-containing aliphatic amino chains) lead to a slower loss of N at low temperatures63,64; on the other hand, the pyrolysis process produces different N-containing compounds, and the proportion of stable components among them affects the change patterns. The significant linear relationship (p < 0.001) between the O/C and H/C atomic ratios exists, suggesting that O and H atoms are lost proportionally during pyrolysis and reinforcing the argument that the changes in the biochar properties at different temperatures are largely due to dehydration reactions44. The linear regression models of BCLg and BCQm have similar slopes, indicating that the two biochars may have gone through similar chemical mechanisms. The models for BCLg, BCPs, and BCQm have similar intercepts and tighter data points at high temperatures, meaning that increased temperatures result in a convergence in the stability and carbonization of them65. The combined differences in the slopes of the models suggest that even if biochars are of similar origins, their pyrolysis mechanisms and post-pyrolysis properties may differ because of the main composition of the feedstock.

The increasing temperature leads to the enhancement of biochar alkalinity through the increase of ash content and the alkaline content in the ash; our study confirmed the dominant effect of ash content on pH as reported in previous works21,22,34. We believe that, in addition to ash content that affects pH, other factors also affect pH. For example, the impact of ash on the pH varies depending on raw materials. Cellulose and hemicellulose produce tar, organic acids, and phenolics during decomposition48,65. This acidic fraction is pyrolyzed or volatilized as an acidic bio-oil result, which is an explanation for the decrease in pH with increasing duration at 400 °C. The acidic functional groups of -COOH and aromatic -OH on the biochar surface decreased significantly with increasing temperature, leading to an increase in biochar pH22,65.

Biochar loses hemicellulose and cellulose at 300 °C and 400 °C; both are unstable C components rich in H and O. This is the reason why labile C has the fastest loss rate at 300 °C and 400 °C. The lignin structure was further pyrolyzed and converted into highly polymerized aromatic C fractions at a temperature of 500 °C, resulting in the further content reduction of labile C and the further increase in the proportion of stable C. The stable C component, further combined with the refractory inorganic crystalline minerals produced by pyrolysis, makes organic-inorganic complexes at higher temperatures (600–700 °C)66,67, and the high temperatures lead to local oxidation. Some studies have suggested that high temperatures decrease biochar stability from the perspective of stable C content alone66. However, the results of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and atomic ratios in this study indicate that even though the stable C content of biochar is lost at 700 °C, there still exist less easily oxidizable structures and a longer half-life. Therefore, the biochar stability cannot be determined solely by the stable C content.

The hysteresis loops of BCLg, BCQm, and BCFm at 500 °C and higher temperatures shared two common features: the first one is the steep region of the desorption branch leading to the lower closure point around a relative pressure from 0.4 to 0.5 P/P0, which is referred to as the force-closed phenomenon. Such a phenomenon is attributed to the instability of the meniscus condensation for pores around 4 nm caused by the adsorption energy of the pore wall and an increased tensile strength in the adsorbed phase, as well as to the pore network effect originating from the complex pore system. The hypothesis is that the system is composed of macropores formed by the biomass vascular structure, and ultra-micropores or micropores on the macroporous walls by further pyrolyzation68,69. Secondly, there is an unclosed hysteresis loop, which can be attributed to the non-rigid structural deformation of biochar by adsorption or pore filling70,71; as well as to the nitrogen trapped by the adsorption potential of the pore wall that cannot be released because of the affinity of nitrogen in biochar caused by the heterogeneous property of the biochar surface71. This agrees with the observation that increasing temperature will deteriorate the hysteresis effect72,73. Furthermore, the existence of the ink-bottle pore in the biochar may intensify this phenomenon.

Mantel tests revealed that most biochar properties were strongly correlated with pyrolysis temperature (p < 0.01), whereas most showed no significant association with residence time (p > 0.05), unequivocally establishing the dominant role of temperature. Furthermore, the significant correlations observed among the various biochar properties collectively indicate a consistent response to pyrolysis conditions. The variation in these correlation patterns with feedstock type consequently demonstrates the influence of the original plant composition on this response (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Further, by integrating the above properties and their change trend, the biochar pyrolysis mechanism was summarized and visualized through a structural equation model (Supplementary Fig. 12). Pyrolysis conditions (pyrolysis temperature and retention time) and raw material components are crucial for the diversity of biochar properties and determine the diversity of biochar functions. The changes in pyrolysis conditions and raw material composition influence the C composition and yield of biochar, thereby determining its C sequestration capacity. These factors also affect the ash content, acidic functional groups, and available nutrients in biochar, which in turn govern its pH, nutrient release, and adsorption properties. Furthermore, by altering the organic structure of biochar, these changes impact the elemental composition of biochar, consequently influencing the stability (half-life), aromaticity, polarity, and energy characteristics of biochar. Higher temperatures will weaken the influence of raw material composition, making biochar from different fuel sources more similar, except for specific surface area and absorptivity. The effect of retention time on biochar was much weaker than that of pyrolysis temperature.

The environmental functions and application prospects of biochar

Mitigating climate change stands as a central objective in biochar research, with the C sequestration potential of biochar representing one of its most significant environmental benefits. This study highlights the notable role of biochar derived from forest surface fuels in climate change mitigation, demonstrating its contributions across three key aspects. Firstly, consistent with previous findings, biochar can achieve long-term C sequestration due to its high chemical stability74,75,76. The biochar of plant origin has almost the highest proportion of stable C, it is also the cleanest compared to the biochar from manure and sludge30,77. Among the plant-derived biomass, the biomass of trees contains more lignin components; its biochar is more stable than gramineous straw biochar44,48. In this work, BCLg produced at 400°C and all biochar produced at 500 °C and above exhibited complete thermochemical alteration (H/Corg molar ratio <0.7) and half-life greater than 1000 years (O/Corg atomic ratio <0.2), which are highly stable chemically and meet the biochar standards set up by the European Biochar Foundation (EBC) and International Biochar Initiative74,75,76. In terms of C sequestration, 104.62–194.23 kg of C (383.61–712.18 kg CO2) can be permanently fixed for every one ton of surface fuel processed, with an additional 4.68–148.96 kg of C (17.16–546.19 kg CO2) being semi-permanently fixed. The observed values are lower than those reported in earlier studies78, which may be attributed to the fact that the current analysis only considers C sequestration per unit mass of biochar. Future research should employ life cycle assessment to evaluate the C sequestration potential of the full chain—from production to application—of biochar derived from forest fuels.

Secondly, biochar can be used to replace fossil fuels to reduce C emissions and save resources79. The HHV of BCLg and BCPs produced at 600 °C(24.33–26.45 MJ kg−1) surpassed that of sub-bituminous coal (24.40 MJ kg−1)80, and other biochar samples demonstrated energy densities (over 17.15 MJ kg−1) greater than that of peat (17.00 MJ kg−1)80, suggesting the biochar has potential usage as solid bio-fuels80,81. Our previous research has also demonstrated this through more advanced thermal analysis82.

Finally, producing biochar from forest surface fuels could mitigate climate warming by curbing wildfires and associated GHG emissions. The fundamental principle of combustion states that fuel is a necessary condition for fire ignition and spread10,11. Consequently, reducing or removing fuel decreases fire intensity or prevents fires, making fuel management a widely adopted strategy for wildfire control12,13. Similar to prescribed burning and fuel clearing, the conversion of forest surface fuels into biochar directly reduces fuel load, thereby suppressing wildfire occurrence and intensity and leading to lower fire-related GHG emissions. Although prescribed burning reduces fuel via low-intensity fires, it still releases substantial amounts of GHGs83. Fuel clearing, which involves the manual or mechanical concentration and piling of fuels, also presents drawbacks: on one hand, natural decomposition of these piles emits GHGs84; on the other, concentrated fuel accumulation increases localized fire risk85. Therefore, further pyrolyzing these fuels into biochar represents a safer and more C-fixing approach to fuel management.

Another significant environmental benefit of biochar is its protective and enhancing effect on ecosystems20,37,38,39,41. The addition of biochar to soil enhances the adsorption and retention capacity of soil organic matter due to its high specific surface area and well-developed porous structure, thereby reducing soil C loss86. The input of biochar-derived SOC directly increases soil organic C content, improving soil fertility and stimulating microbial activity87. In this work, biochar produced at 300 °C and 400 °C is rich in humic acid-like compounds50. These strongly hydrophilic components facilitate the formation of soil aggregates, thereby improving soil quality88, exhibit high bioavailability that promotes plant growth88, and can complex metal cations to alleviate salt stress and mitigate contamination89.

Biochar shows unique advantages in the remediation of acidic soil. The maximum pH of the forest surface fuel biochar (11–13) was significantly higher than that of most biochar in previous studies (pH 10–11)21,34, making it a superior candidate for remediating acidified soils34. CEC refers to the adsorption capacity of biochar for cations in solution and is an important indicator for assessing the ability of biochar to act as a soil conditioner and to purify heavy metal cations from the environment90,91. It has been suggested that biochar prepared at low temperatures has a greater abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups and has a larger CEC90. BCLg, BCQm, and BCFm produced at 400 °C have excellent CEC (>1 mol kg−1). This high CEC provides surface negative charges to soil organic matter-mineral complexes, which further promotes the formation of soil aggregates92 and enhances the adsorption of cationic pollutants. The effective adsorption of heavy metals such as Zn(II), Cd(II), Cr(VI), and Pb(II) further confirms the potential of forest surface fuel biochar as a material for remediating contaminated environments.

Our result also revealed low available N and P in the biochar, which is attributed to the nutrient-poor nature of the forest floor feedstock and further losses during pyrolysis93. Therefore, it needs to be further loaded with nutrients to be produced as fertilizer.

In conclusion, this work comprehensively details the pyrolysis mechanisms of temperature and boreal forest surface fuels, biochar, and highlights the application prospects of the biochar in ecosystems. Our research supports biochar production as a sustainable, low-C alternative to traditional forest fuel management. This technology also applies to the recycling and reuse of other types of forest waste, such as forest harvest residues. To mitigate the increasing threats of wildfires and climate warming, this strategy should be a priority deployed in regions with intensive fuel loads, notably Northern China, North America, and Siberia.

Limitations and future directions of the study

To sum up, reducing forest fuels through biochar technology is a sustainable means of suppressing forest fires, but there are still some issues that are worthy of further investigation:

(1) It is unrealistic to dispose of all forest fuels. Unlike crop straw, the cost of removing forest fuels from forest stands is directly proportional to the distance between stands and roads. Furthermore, removing all fuels to eliminate wildfires can damage the forest ecosystem. Therefore, this study may be more applicable to the wildland-urban interface and forest edges only and can help effectively prevent fires that may seriously affect human communities.

(2) Collecting a large amount of forest fuels for centralized processing will increase transportation costs. Due to different national policies and conditions (for example, China’s strict forest management policy does not allow commercial logging), the biomass that needs to be pyrolyzed is mainly surface litter. Therefore, in the real production scenario, more convenient and safe technologies need to be developed that can be used directly in forests to make usable biochar.

(3) This study found that there are significant differences in biochar produced from surface fuels of different tree species. As the potential of biochar has not been fully exploited globally, more research on surface fuel biochar from diverse and extensive regions is needed. As the heating rate also affects the performance of biochar, future research can consider the impact of different heating rates on forest surface fuel biochar.

(4) Unlike synthetic materials, biochar originates from the pyrolysis of biomass, and relationships between biochar properties are complex. The correlation analysis alone may overlook or overly explain such relationships, thereby weakening the persuasiveness of the study. Even though we have used the RF and PLS-SEM methods to detect the formation and comprehensive relationship of biochar properties, the analyses were only performed on 180 samples, and more samples should be pursued in future studies. Nevertheless, our study can play a reference role for similar future studies. Future research or meta-analysis can also integrate in-depth mathematical and statistical methods to seek the intrinsic connections of biochar properties.

Methods

Preparation of biochar

The fallen leaves of Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii (Rupr.) Kuzen), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb), and Manchurian ash (Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr) were collected in October 2021 in Heilongjiang Province, China. Forests in northern China and even higher latitudes produce large amounts of fallen leaves in September and October each year. The leaves break down slowly because of the cold weather and is a major fuel for autumn wildfires. Therefore, China’s forestry and security departments invest a large amount of costs every year to reduce this fuel load. Thirty to forty kilograms of each raw material were collected at one time from a 20 × 30 m plot in a mature natural forest to ensure enough to complete all experiments.

After removing the insects, stones, and soil, the raw materials were dried naturally in the laboratory and then placed in an oven at a temperature of 105 °C for more than 24 h to reach a constant weight. Then the materials were ground into powder, sieved through 250 μm, and sealed. The powder was compacted into an iron box (11 × 8 × 6.5 cm), and the box was wrapped with 3 layers of tin foil to ensure that the environment in the box tends to be strictly oxygen-free30. A total of 60 biochar samples were obtained by pyrolysis using a muffle furnace (JXL-620, Renhe, China) at temperatures of 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, and 700 °C for 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h, correspondingly, with a temperature increase rate of 40 °C min−1, and cooling to room temperature. The production of each biochar sample was repeated three times to ensure repeatability and to produce sufficient samples for various physicochemical characterizations (yield in Fig. 3b).

Components of biochar

All aqueous solutions for this experiment were prepared using ultrapure water (UW, 18.2 MΩ cm−1) obtained from a water purification system, and all chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade, purchased from professional chemical companies. All treatments were made of three parallel samples.

Biochar Yield (%) is calculated by Eq. (1)30

where m1 is the biochar mass (g); m0 is the raw material dry weight (g).

The crude ash content of biochar was determined by the dry ashing method. 5.00 g of biochar was weighed and placed in a crucible and completely ashed to a constant weight at 800 °C, and the weight of the crucible was subtracted to get the crude ash mass. The crude ash content was expressed as Ash (%)31.

where m2 is the mass of the crucible (g); m3 is the mass of the crucible and biochar (g), and m4 is the mass of the crucible and sample (g).

The elemental analyzer (UNICUBE, Elementar, Germany) was used to determine the total carbon (C), total nitrogen (N), total hydrogen (H), and total sulfur (S) content of biochar and their raw materials. The elemental oxygen content was calculated by mass conservation. Since the S content is too low and partly less than the lower limit of detection of the analyzer (0.02%), it is not included in the calculation.

Atomic ratios of elements with reference to Eq. (4)

where A and B meant any two elements.

Biochar NH4+ and NO3− concentrations were determined from 1 mol L−1 KCl (biochar/solution 1:10) extracts by a discontinuous flow analyzer (Smartchem200, AMS Alliance, France)94.

Biochar available phosphorous (AP) concentrations were determined from 1 mol L−1 NaHCO3 (pH = 8.5) (biochar/solution 1:10) extracts using the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method by a discontinuous flow analyzer.

Separation and determination of C fractions

In this study, to characterize the biochar and C sequestration properties as completely and comprehensively as possible based on the previous researches30, six C fractions of biochar were separated according to the extraction conditions and chemical methods, which were labile C (LC), stable C (SC), cold-water-soluble C (CCS), hot water soluble C (CHS), alkali-soluble C (CAS), and carbonate (CN). The detailed separation and extraction steps are in the Supplementary Method.

Soluble organic carbon (SOC) characterization

UV-visible absorbance was analyzed by a UV-visible spectrophotometer (SpectraMax iD5, Molecular Devices, U.S). A three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix (3D-EEM) of WSOC was obtained by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, F-7100, Japan) at 250–500 nm excitation and 300–600 nm emission wavelengths, 5 nm excitation and emission slits95. The UV absorbance at 355 nm (a355), Specific ultraviolet absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254)96, the absorption spectral slopes ratios at 275–295 nm and 350–400 nm (SR)97, E2/E3 (the ratio of absorbance at 254 nm and 365 nm, a254/a365), E2/E4 (the ratio of absorbance at 254 nm and 436 nm, a254/a436), E4/E6 (the ratio of absorbance at 465 nm and 665 nm, a465/a665)98, fluorescence intensity at 355 nm (Fn355)99, fluorescence index (FI), biological index (BIX), and humification index (HIX) were calculated to show WSOC characteristics95. Their calculation methods and significance can be found in the Supplementary Table 4.

Characterization of biochar

Higher heating values (HHV) were determined by an oxygen bomb calorimeter. The net calorific value of biochar is represented by the ash-free caloric value (AFCV, Eq. 5).

Biochar and water were mixed at a mass ratio of 1:20 (w/v), and the mixture was separated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm (rcf ≈ 6700 g) for 20 min after constant shaking at 25 °C for 24 h (200 rpm), and the supernatant was obtained by filtration. The pH was measured using a pH meter, and electrode and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured using a conductivity meter.

Biochar functional group composition was determined by the Fourier transform infrared ray. Biochar and KBr (spectroscopic grade) were mixed tablet at a mass ratio of 1:100, scanned 64 times per sample in the spectral range of 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

The Boehm titration method100 was used to determine the content of oxygenated functional groups. The biochar material (0.5 g) was mixed with 50 mL of 0.05 M NaHCO3, Na2CO3, NaOH, or HCl, in 50 mL tubes, for 24 h. To neutralize excess base or acid, back-titrations were carried out using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH, respectively. Oxygen-containing functional groups were determined based on the assumption that NaHCO3 neutralizes carboxyl groups, Na2CO3 neutralizes carboxyl groups and lactones, NaOH neutralizes all organic acids and acidic functional groups including phenols, while HCl neutralizes all alkaline groups101.

The CEC of biochar was determined according to the Chinese National Environmental Standard (HJ 889-2017) as biochar: Co(NH3)6Cl3 standard solution (1.66 cmol L−1) = 0.5 g/20 ml was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min after shaking at 25 °C for 1 h (200 rpm), and the Co3+ concentration was determined by a discontinuous flow analyzer to determine the Co3+ concentration (Eq. 6).

where A0 is the absorbance of the blank sample; A is the absorbance of the sample to be tested; V is the volume of the extracted liquid (ml); B represents the slope of the absorbance standard curve, and M represents the weight of biochar (kg).

A gas adsorption analyzer with liquid N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm technique was applied to analyze the pore structure of biochar. The total surface area of biochar was assessed by calculating the amount of adsorbed N2 using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method; the micropore volume and external surface area of biochar were determined using the t-Plot method; and the pore size distribution was obtained using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method68,69. Structure and morphologies were examined by scanning electron microscopy.

Detergent fibers extraction of surface combustibles

The extraction of detergent fibers was carried out by a fiber tester, following the analytic procedure developed by Van Soest102. In the analysis, biomass was separated progressively into neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and strong acid detergent fiber (SADF). NDF mainly consists of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and ash, while ADF is composed of cellulose, lignin, and ash. There are only lignin and ash in SADF. The masses of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose are calculated based on the mass differences of NDF, ADF, and SADF.

Adsorption kinetics experiment

According to previous research, the initial concentrations of Cr (VI), Zn (II), Pb (II), Cd (II), and Cd (II) were set to 200 mg L−1, and As (V) was 2.500 mg L−1 103. The background electrolyte was a Na+ solution with the same anion. Samples were taken at 10, 30, 60, 120, 180, 360, 720, and 1440 min, with ionic concentration measured by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, Agilent 7700, Agilent, US). Four dynamic models were established based on the experimental data57,58,60 (Eqs. 7–11).

1. First-order dynamic model:

2. Second-order dynamic model:

where “Qe” and “Qt” (mg/g) represent the adsorption capacity at equilibrium time and time t (min), and “k1” (min−1), “k2” (g mg−1 min−1) are the adsorption rate constants of models 1 and 2, respectively.

3. Elovich model:

where constant “α” is related to the rate of chemisorption and the constant “β” is related to the surface coverage.

4. Intra-particle diffusion model:

where “ki” (mg · g−1 · min−0.5) is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant and “C” (mg g−1) is a constant indicating the number of boundary layer thicknesses of the adsorbent.

Statistical analyses

Three replications were performed for all biochar experiments except for the N2 adsorption experiment, and five replications were performed for the separation and determination of the major components of surface combustibles. Data were preprocessed via Microsoft Office365 Excel.

One-way ANOVA was used to analyze whether different pyrolysis temperatures and retention times of maximum temperatures had significant effects on the properties of biochar. Multiple comparisons were used to compare the differences between biochar properties under different pyrolysis conditions. The homogeneity of variance test is used to check whether the population variance of each group of samples is the same, which is required for the multiple comparison methods. In multiple comparisons analysis, the same pyrolysis temperature and retention time are grouped into one group (the response variables of each biochar type, including raw materials, were divided into 16 groups, while the response variables that do not require raw materials to be included in the analysis consisted of 15 groups). All groups have 3 replicates. If the sample variance is the same (Supplementary Table 1), the Tukey test is used to rank the response variables of each group (Supplementary Table 2). If the sample variances are different, the Games-Howell test is used to rank each group of response variables (Supplementary Table 2). It is considered that the false positive probability of the LSD test in the case of homogeneity of variance is too large to be applicable, and the sample size of each group is equal after comparison in this study, which meets the requirements of the Tukey test. One-way ANOVA analysis, homogeneity of variance test, and Tukey test procedure and ranking were completed by SPSS 26.0. The Games-Howell validation and sorting were completed by the R package rstatix v0.7.2 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix).

The H/C molar ratio-O/C molar ratio and pH-ash linear models fitted by Origin 2021. The R package Simba v0.3-5 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=simba) was used to analyze the similarity between linear models (reflected in the difference between the slopes or intercepts of the models). The correlations between all the properties of biochar were measured by the Spearman’s correlation coefficients and they were subjected to pyrolysis temperature and retention time by using Mantel test. The analysis was done through the R package LinkET v0.0.7.4 (https://github.com/Hy4m/linkET). PCA was conducted through SPSS 26.0. The Random Forest (RF) algorithm is accomplished with the R package random Forest v 4.7-1.1 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=randomForest). Partial Least Squares - Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was built and tested with R packages plspm v0.5.0 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=plspm) and vegan v2.4-6 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan).

As the same statistical analyses, Fig. 1a was made by ArcGIS 10.2. Figure 6b and Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 were made by R v4.3.1. Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9 were photographed by SEM, Supplementary Fig. 12 was finished by Visio 2021, and all other figures were completed by Origin 2021. A p < 0.05 was statistically significant. Microsoft Office365 PowerPoint was used for the figure layout. All tables were created by Microsoft Office365 Excel.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The code and the data can be downloaded at this address: https://github.com/wlx9934/Biochar_paper_code.

References

FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2020).

Schimel, D. S. et al. Recent patterns and mechanisms of carbon exchange by terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 414, 169–172 (2001).

Ruckstuhl, K. E., Johnson, E. A. & Miyanishi, K. Introduction. The boreal forest and global change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 2243–2247 (2008).

Andela, N. et al. A human-driven decline in global burned area. Science 356, 1356–1362 (2017).

Bowman, D. M. J. S. et al. Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 500–515 (2020).

Schoennagel, T. et al. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4582–4590 (2017).

Byrne, B. et al. Carbon emissions from the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Nature 633, 835–839 (2024).

Murdiyarso, D. et al. The potential of Indonesian mangrove forests for global climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1089–1092 (2015).

Albert, J. S. et al. Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science 379, eabo5003 (2023).

British Columbia Ministry of Forests. 2024 Fuel Management Practices Guide: A Technical Guide for Wildfire Risk Reduction Through Fuel Management in British Columbia (BC Wildfire Service, 2024).

Safford, H. D., Stevens, J. T., Merriam, K., Meyer, M. D. & Latimer, A. M. Fuel treatment effectiveness in California yellow pine and mixed conifer forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 274, 17–28 (2012).

Bowman, D. M. et al. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. J. Biogeogr. 38, 2223–2236 (2011).

Hsu, A. et al. A global assemblage of regional prescribed burn records—GlobalRx. Sci. Data 12, 1083 (2025).

Liu, J. C. et al. Particulate air pollution from wildfires in the Western US under climate change. Clim. Change 138, 655–666 (2016).

Engebretson, J. M. et al. Characterizing public tolerance of smoke from wildland fires in communities across the United States. J. For. 114, 601–609 (2016).

Hoover, K. & Bracmort, K. Wildfire Management: Federal Funding and Related Statistics (Library of Congress, 2015).

U. S. Department of Agriculture, F. S. FY 2023 Budget Justification: Forest Service (USDA Forest Service, 2022).

Natural Resources Canada. Departmental Plan 2023-24 (Government of Canada, 2023).

Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 447, 143–144 (2007).

Sharma, A. K. et al. A critical review on biochar production from pine wastes, upgradation techniques, environmental sustainability, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 387, 129632 (2023).

Ippolito, J. A. et al. Feedstock choice, pyrolysis temperature and type influence biochar characteristics: a comprehensive meta-data analysis review. Biochar 2, 421–438 (2020).

Waqas, M. et al. Development of biochar as fuel and catalyst in energy recovery technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 188, 477–488 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Roles of biochar-derived dissolved organic matter in soil amendment and environmental remediation: a critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130387 (2021).

Lyu, H., Zhang, Q. & Shen, B. Application of biochar and its composites in catalysis. Chemosphere 240, 124842 (2020).

Pan, X., Gu, Z., Chen, W. & Li, Q. Preparation of biochar and biochar composites and their application in a Fenton-like process for wastewater decontamination: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 754, 142104 (2021).

Kwon, G., Bhatnagar, A., Wang, H., Kwon, E. E. & Song, H. A review of recent advancements in utilization of biomass and industrial wastes into engineered biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 400, 123242 (2020).

Bo, X. et al. Benefits and limitations of biochar for climate-smart agriculture: a review and case study from China. Biochar 5, 1–24 (2023).

Nguyen, T. T. N. et al. Effects of biochar on soil available inorganic nitrogen: a review and meta-analysis. Geoderma 288, 79–96 (2017).

Osman, A. I. et al. Biochar for agronomy, animal farming, anaerobic digestion, composting, water treatment, soil remediation, construction, energy storage, and carbon sequestration: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 2385–2485 (2022).

Wei, S. et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature and feedstock on carbon fractions of biochar produced from pyrolysis of rice straw, pine wood, pig manure and sewage sludge. Chemosphere 218, 624–631 (2019).

Uchimiya, M., Ohno, T. & He, Z. Pyrolysis temperature-dependent release of dissolved organic carbon from plant, manure, and biorefinery wastes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 104, 84–94 (2013).

Parshetti, G. K., Kent Hoekman, S. & Balasubramanian, R. Chemical, structural and combustion characteristics of carbonaceous products obtained by hydrothermal carbonization of palm empty fruit bunches. Bioresour. Technol. 135, 683–689 (2013).

Xiao, X., Chen, B. & Zhu, L. Transformation, morphology, and dissolution of silicon and carbon in rice straw-derived biochars under different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3411–3419 (2014).

Zhang, X., Zhang, P., Yuan, X., Li, Y. & Han, L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and correlation analysis on the yield and physicochemical properties of crop residue biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 296, 122318 (2020).

Chen, B., Zhou, D. & Zhu, L. Transitional adsorption and partition of nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 5137–5143 (2008).

Fang, K. et al. ENSO modulates wildfire activity in China. Nat. Commun. 12, 1764 (2021).

Palviainen, M. et al. Biochar amendment increases tree growth in nutrient-poor, young Scots pine stands in Finland. For. Ecol. Manag. 474, 118362 (2020).

Zhu, X. et al. Short-term effects of biochar on soil CO2 efflux in boreal Scots pine forests. Ann. For. Sci. 77, 59 (2020).

Köster, E., Pumpanen, J., Palviainen, M., Zhou, X. & Köster, K. Effect of biochar amendment on the properties of growing media and growth of containerized Norway spruce, Scots pine, and silver birch seedlings. Can. J. For. Res. 51, 31–40 (2021).

Jamal, M. U. & Fletcher, A. J. Design of experiments study on Scottish wood biochars and process parameter influence on final biochar characteristics. Bioenergy Res. 16, 2342–2355 (2023).

Choudhary, V., Patel, M., Pittman, C. U. & Mohan, D. Batch and continuous fixed-bed lead removal using Himalayan pine needle biochar: isotherm and kinetic studies. ACS Omega 5, 16366–16378 (2020).

Huang, M. et al. Effects of biochar on soil carbon pool stability in the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) forest are regulated by the dominant soil microbial ecological strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 951, 175725 (2024).

Das, S. K., Ghosh, G. K., Avasthe, R. K. & Sinha, K. Compositional heterogeneity of different biochar: effect of pyrolysis temperature and feedstocks. J. Environ. Manag. 278, 111501 (2021).

Keiluweit, M., Nico, P. S., Johnson, M. G. & Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1247–1253 (2010).

Al-Wabel, M. I., Al-Omran, A., El-Naggar, A. H., Nadeem, M. & Usman, A. R. A. Pyrolysis temperature induced changes in characteristics and chemical composition of biochar produced from conocarpus wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 131, 374–379 (2013).

Wang, Y., Hu, Y. & Zhao, X. Comparisons of biochar properties from wood material and crop residues at different temperatures and residence times. Energy Fuels 27, 5890–5899 (2013).

Azargohar, R., Nanda, S., Kozinski, J. A., Dalai, A. K. & Sutarto, R. Effects of temperature on the physicochemical characteristics of fast pyrolysis bio-chars derived from Canadian waste biomass. Fuel 125, 90–100 (2014).

Yu, H., Zhang, Z., Li, Z. & Chen, D. Characteristics of tar formation during cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin gasification. Fuel 118, 250–256 (2014).

Uchimiya, M., Hiradate, S. & Antal, M. J. Influence of carbonization methods on the aromaticity of pyrogenic dissolved organic carbon. Energy Fuels 29, 2503–2513 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Investigating biochar-derived dissolved organic carbon (DOC) components extracted using a sequential extraction protocol. Materials 15, 3865 (2022).

Fan, J., Duan, T., Zou, L. & Sun, J. Characteristics of dissolved organic matter composition in biochar: effects of feedstocks and pyrolysis temperatures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 85139–85153 (2023).

Cao, Q. et al. Insight to the physiochemical properties and DOM of biochar under different pyrolysis temperature and modification conditions. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 166, 105590 (2022).

Cheng, S., Yao, K., Tian, H., Yang, T. & Chen, L. Synergistic catalytic effects on nitrogen transformation during biomass pyrolysis: a focus on proline as a model compound. Molecules. 29, 3118 (2024).

Stefanidis, S. D. et al. A study of lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis via the pyrolysis of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 105, 143–150 (2014).

Tang, J., Li, X., Luo, Y., Li, G. & Khan, S. Spectroscopic characterization of dissolved organic matter derived from different biochars and their polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) binding affinity. Chemosphere 152, 399–406 (2016).

Uchimiya, M., Liu, Z. & Sistani, K. Field-scale fluorescence fingerprinting of biochar-borne dissolved organic carbon. J. Environ. Manag. 169, 184–190 (2016).

Wu, F., Tseng, R. & Juang, R. Characteristics of Elovich equation used for the analysis of adsorption kinetics in dye-chitosan systems. Chem. Eng. J. 150, 366–373 (2009).

Wang, J. & Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 390, 122156 (2020).

HO, Y. Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 136, 681–689 (2006).

Malash, G. F. & El-Khaiary, M. I. Piecewise linear regression: a statistical method for the analysis of experimental adsorption data by the intraparticle-diffusion models. Chem. Eng. J. 163, 256–263 (2010).

Demirbas, A. Effects of temperature and particle size on bio-char yield from pyrolysis of agricultural residues. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 72, 243–248 (2004).

Usman, A. R. A. et al. Biochar production from date palm waste: charring temperature induced changes in composition and surface chemistry. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 115, 392–400 (2015).

Cantrell, K. B., Hunt, P. G., Uchimiya, M., Novak, J. M. & Ro, K. S. Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 107, 419–428 (2012).

Koutcheiko, S., Monreal, C. M., Kodama, H., McCracken, T. & Kotlyar, L. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon derived from the thermo-chemical conversion of chicken manure. Bioresour. Technol. 98, 2459–2464 (2007).

Lee, Y. et al. Comparison of biochar properties from biomass residues produced by slow pyrolysis at 500°C. Bioresour. Technol. 148, 196–201 (2013).

Yuan, J., Xu, R. & Zhang, H. The forms of alkalis in the biochar produced from crop residues at different temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3488–3497 (2011).

Guo, J. & Chen, B. Insights on the molecular mechanism for the recalcitrance of biochars: interactive effects of carbon and silicon components. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9103–9112 (2014).

Qi, L., Tang, X., Wang, Z. & Peng, X. Pore characterization of different types of coal from coal and gas outburst disaster sites using low temperature nitrogen adsorption approach. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27, 371–377 (2017).

Groen, J. C., Peffer, L. A. & Pérez-Ramı Rez, J. Pore size determination in modified micro-and mesoporous materials. Pitfalls and limitations in gas adsorption data analysis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 60, 1–17 (2003).

Liu, C. J., Wang, G. X., Sang, S. X. & Rudolph, V. Changes in pore structure of anthracite coal associated with CO2 sequestration process. Fuel 89, 2665–2672 (2010).

Tang, X., Wang, Z., Ripepi, N., Kang, B. & Yue, G. Adsorption affinity of different types of coal: mean isosteric heat of adsorption. Energy Fuels 29, 3609–3615 (2015).

Ravikovitch, P. I., Domhnaill, S. Ó, Neimark, A. V., Schüth, F. & Unger, K. K. Capillary hysteresis in nanopores: theoretical and experimental studies of nitrogen adsorption on MCM-41. Langmuir 11, 4765–4772 (1995).

Machin, W. D. Temperature dependence of hysteresis and the pore size distributions of two mesoporous adsorbents. Langmuir 10, 1235–1240 (1994).

IBI. Standardized Product Definition and Product Testing Guidelines for Biochar that Is Used in Soil (International Biochar Initiative, 2015).

Spokas, K. A. Review of the stability of biochar in soils: predictability of O:C molar ratios. Carbon Manag. 1, 289–303 (2010).

Leng, L., Huang, H., Li, H., Li, J. & Zhou, W. Biochar stability assessment methods: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 647, 210–222 (2019).

Yuan, H. et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on physical and chemical properties of biochar made from sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 112, 284–289 (2015).

Yang, Q. et al. Country-level potential of carbon sequestration and environmental benefits by utilizing crop residues for biochar implementation. Appl. Energy 282, 116275 (2021).

Lehmann, J. et al. Biochar in climate change mitigation. Nat. Geosci. 14, 883–892 (2021).

Selvarajoo, A., Wong, Y. L., Khoo, K. S., Chen, W. & Show, P. L. Biochar production via pyrolysis of citrus peel fruit waste as a potential usage as solid biofuel. Chemosphere 294, 133671 (2022).

ANGIN, D. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate on biochar obtained from pyrolysis of safflower seed press cake. Bioresour. Technol. 128, 593–597 (2013).

Wang, L. et al. The performance and prediction of converting forest residual biomass into solid biofuel, saving fossil fuel and reducing forest fire. Ind. Crop. Prod. 233, 121363 (2025).

Bradstock, R. A. et al. Modelling the potential for prescribed burning to mitigate carbon emissions from wildfires in fire-prone forests of Australia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 21, 629–639 (2012).

Harris, N. L. et al. Global maps of twenty-first century forest carbon fluxes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 234–240 (2021).

OECD. Taming Wildfires in the Context of Climate Change. (OECD Publishing, 2023).

Suliman, W. et al. The role of biochar porosity and surface functionality in augmenting hydrologic properties of a sandy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 574, 139–147 (2017).

Pei, J. et al. Five years of biochar amendment combined with reduced fertilization and irrigation improved the soil organic carbon composition and structure in a solonchak. Sci. Rep. 15, 21823 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Biochar combined with humic acid improves the soil environment and regulate microbial communities in apple replant soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 283, 116958 (2024).

Asgharzade, A. & Babaeian, M. Investigating the effects of humic acid and acetic acid foliar application on yield and leaves nutrient content of grape (Vitis vinifera). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 6049–6054 (2012).

Lee, J. W. et al. Characterization of biochars produced from cornstovers for soil amendment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 7970–7974 (2010).

Abdel-Fattah, T. M. et al. Biochar from woody biomass for removing metal contaminants and carbon sequestration. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 22, 103–109 (2015).

Cen, R. et al. Effect mechanism of biochar application on soil structure and organic matter in semi-arid areas. J. Environ. Manag. 286, 112198 (2021).

Elkhlifi, Z. et al. Potential role of biochar on capturing soil nutrients, carbon sequestration and managing environmental challenges: a review. Sustainability 15, 2527 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. The mechanistic role of wildfire ash in regulating post-fire nitrogen transformation: a pathway as critically important as the thermal effects of fire. Catena 259, 109396 (2025).

Zhou, P. et al. Spatial patterns and environmental functions of dissolved organic matter in grassland soils of China. Nat. Commun. 15, 6356 (2024).

Weishaar, J. L. et al. Evaluation of specific ultraviolet absorbance as an indicator of the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved organic carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4702–4708 (2003).

Fu, H. et al. Photochemistry of dissolved black carbon released from biochar: reactive oxygen species generation and phototransformation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1218–1226 (2016).

Jaffé, R. et al. Source characterization of dissolved organic matter in a subtropical mangrove-dominated estuary by fluorescence analysis. Mar. Chem. 84, 195–210 (2004).

Guan, Y., Yu, G., Jia, N., Han, R. & Huo, D. Spectral characteristics of dissolved organic matter in Plateau Lakes: identifying eutrophication indicators in Southwest China. Ecol. Inform. 82, 102703 (2024).

Boehm, H. P. Some aspects of the surface chemistry of carbon blacks and other carbons. Carbon 32, 759–769 (1994).

Rangel-Mendez, J. R. & Streat, M. Adsorption of cadmium by activated carbon cloth: influence of surface oxidation and solution pH. Water Res. 36, 1244–1252 (2002).

Goering, H. K. & Van, S. P. Forage Fiber Analysis USDA-ARS Agriculture Handbook (Gov.Print, 1971).

Sahu, N. et al. Adsorption of As(III) and As(V) from aqueous solution by magnetic biosorbents derived from chemical carbonization of pea peel waste biomass: isotherm, kinetic, thermodynamic and breakthrough curve modeling studies. J. Environ. Manag. 312, 114948 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32371881), National Forestry and Grassland Administration “Research and Development of the Key Technologies for Three-North Shelterbelt Forest Program” (202401), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025T180545), and the Fundamental Research Funds of CAF (CAFYBB2024ZA004). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper. Special thanks to Prof. Yonghe Wang (Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service: Edmonton, Alberta, CA) for the language refinement of this text, and Jili Zhang and Xin Zheng (Harbin Forestry Machinery Research Institute, Heilongjiang, China) for the carbon component experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guang Yang and Lixuan Wang conceived the research idea and designed the study. Lixuan Wang and Yi Ye performed the main data analysis. Lixuan Wang wrote the manuscript. Stephen Joseph, Wei Feng, and Guang Yang revised the manuscript. Xiankui Quan and Hongzhou Yu provided experimental equipment. Lixuan Wang designed and collaborated with Ruijie Zhang, Weilong Zhang, Jibin Ning, Jiaqi Gao, and Xiangbei Zhou to complete all experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yongqiang Liu and Nandita Basu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Joseph, S., Feng, W. et al. The performance, pyrolysis mechanism and environmental functions of forest surface fuel biochar. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1037 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03016-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03016-3