Abstract

Earthquake swarms are enigmatic seismic phenomena that occur across diverse tectonic settings, from volcanic to intraplate regions, and are often associated with fluid migration, magmatic activity, or stress redistribution. The Northwest Bohemia/Vogtland region is a globally recognized hotspot and natural laboratory for such activity. This study examines the recent activation of an earthquake swarm in the region after a century of dormancy. By integrating high-resolution seismicity patterns and earthquake source mechanisms with models of fluid migration, we provide a detailed reconstruction of the swarm’s temporal and spatial evolution. Our seismicity modeling suggests the activation of a pre-existing fault by natural hydro-fracturing and hydro-shearing under the influence of ascending magmatic fluids, beginning with a high-pressure CO2-rich fluid intrusion, followed by transitions to low-pressure hydro-shearing on the fault, likely associated with CO2-magma mixtures. Our results emphasize the pivotal role of fluid overpressure and fault zone weakening in controlling swarm dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

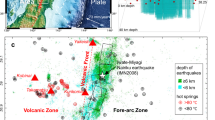

Located within the Bohemian Massif, one of the largest outcrops of Variscan basement in Europe, the Northwest Bohemia/Vogtland region (Fig. 1) hosts one of the most active seismic zones in Central Europe. This region is where the term “earthquake swarm” was first introduced1, highlighting its significance in seismology. Persistent seismic activity makes this region a key site for swarm studies. In addition, widespread carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with magmatic crustal underplating provide an exceptional natural laboratory for investigating interactions between tectonics, magmatism, and fluid migration. The Cheb Basin, situated at the intersection of the Eger Rift and the Mariánské Lázně Fault (Fig. 1), is the center of seismicity and gas emissions2 and is characterized by elevated heat flow, alkaline volcanism, and five Quaternary volcanoes3. Since 1985, an NS trending zone crossing Nový Kostel (NK) (Fig. 1) has episodically produced swarms with the largest seismic moment release in the entire region4. However, in March 2024, an intense seismic swarm emerged in the Klingenthal–Kraslice (KK) zone northeast of NK, after 125 years of rest1. This marks a striking shift in regional seismicity, raising key questions about its underlying mechanisms.

a Regional map showing the tectonic setting and seismic activity from 1982 to 2024. The triangles represent the seismic stations used. The Mariánské Lázně Fault (MLF) and the Bergen Baryt Fault are marked. The recent swarm activity in the Klingenthal–Kraslice region (red) is defined by the black box, which includes a ±2.5 km buffer around the main cluster to account for location uncertainties, especially when comparing with earlier seismicity. The most prominent seismically active area (Novy Kostel) is also highlighted (yellow-orange). b A zoomed-in view of the Klingenthal–Kraslice swarm, with centroid moment tensors (CMTs) for events with MW > 1.2 (lower hemisphere projections of double-couple components). The December 2023 activity is marked with dark red dots, while the main swarm (March–May 2024) is shown as red dots. c Temporal variation of seismicity (1982–2024), showing event magnitudes (ML) and composite moment tensors for larger events from previous studies12,14 and this paper. The earthquakes are compiled from three different catalogs: (1) Neunhöfer (1962–1997)75, (2) West Bohemia Local Seismic Network, WEBNET (1997–2023), (3) Qseek (2023–2024), a high-resolution catalog covering 2023–2024, obtained through machine learning (ML)-based detection and analysis method. The indicated regions include the recent Klingenthal–Kraslice swarm (in red); all events located within the black box in (a), the seismically active Novy Kostel area (yellow-orange), and off-zone events (gray) outside these highlighted regions. The normalized cumulative moment for the Klingenthal–Kraslice and Novy Kostel regions is shown on the right axis.

The mid-crustal earthquake swarms are commonly attributed to fluid transfer from the upper mantle and pore pressure perturbations5. However, the relative roles of magma, CO2, and their interaction with water and rock in triggering swarms and driving upper crustal deformation remain less understood. The new KK swarm began in December 2023 and peaked during the March–May 2024 period. Since then, seismic activity has generally subsided, though intermittent bursts continue. It stands for the first significant earthquake swarm near Klingenthal–Kraslice since 18971, which developed into a phase of strong earthquakes distributed over the entire Vogtland swarm region from 1900 until 19151,6,7,8. There is only evidence of a weaker swarm earthquake activity near KK in 19949 (Fig. 1c). Since the recent activity is the first high-resolution instrumental observation of a massive swarm near KK after a centuries-long hiatus, it provides a unique opportunity to study the spatiotemporal patterns in detail and to compare them with historical swarms.

Our seismic analysis benefits from exceptionally dense observations in close proximity to the swarm, including high-frequency borehole arrays with a sampling rate of 1 kHz (Figs. 1 and S1). By combining seismicity and seismic source studies with fluid intrusion models, we identify a transition from highly buoyant fluids at high overpressure to less buoyant fluids at lower overpressure, e.g., from CO2-rich fluids to CO2-magma mixtures, which cause first hydraulic fractures followed by growth of hydro-shearing on the activated fault. These findings are compared with alternative models and shed light on the crucial role of CO2-rich magmatic fluids in the formation of recurrent earthquake swarms.

High-resolution catalog and moment tensors

In recent years, as part of the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP) “Drilling the Eger Rift” project, a unique network of surface and multiple borehole high-frequency arrays has been established in the study area (Figs. 1 and S1), in addition to the existing monitoring networks10. The infrastructure is located only a few kilometers from the swarm earthquakes, and the sampling rate is up to 1 kHz, which allows a detailed investigation of subsurface processes such as fluid migration and fault zone dynamics. By integrating this network with ML algorithms, we have built a high-resolution earthquake catalog, recording 8069 seismic events from December 2023 to June 2024, including the smallest-size events with magnitudes of ML = −0.5. This represents a tenfold enhancement of events resolved in classical agency catalogs and provides unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution. The enhanced dataset specifies fine-scale fault geometries, detects intricate seismicity patterns that were not formerly resolvable, and documents the detailed history of the swarm with high accuracy.

The earthquakes, confined in a narrow NW-SE trending zone of about 1.2 km width and 2 km length, show systematic spatiotemporal migration patterns. To investigate the source mechanisms, we computed centroid moment tensors (CMT), the first for this focal area, using a Bayesian inversion approach11,12,13. We obtain 64 CMT solutions for events with MW > 1.2. This approach accounts for uncertainties, providing robust estimates of the fault characteristics (see the Methods section). The solutions reveal the activation of a previously unrecognized fault segment, predominantly normal faulting, with strike = 329° ± 27, dip = 60° ± 6, and rake = −62° ± 12 (Fig. 1b), aligning with the spatial extend of the swarm, likely influenced by localized stress accumulation. This discovery is remarkable because other earthquake swarms in the region, such as at NK, have been dominated in the past by strike-slip and thrust faulting (Fig. 1c)12,14. The regional variation of mechanisms and activated faults suggests significant heterogeneity in the stress field, likely influenced by transient deformation, fluid migration, and metasomatic processes within the crust.

Swarm phases

The first micro-earthquakes occurred in December 2023, about 2 km north of the later KK swarm center, at a depth between 10 and 11 km (Fig. 1b). These were the deepest events in the entire sequence. After a period of about 3 months, the swarm moved slightly south to shallower depths and exhibited an unprecedented rate of seismicity between March and June 2024. Since then, the activity has been greatly reduced, but micro-earthquakes occasionally occur for a few days. Figure 2 illustrates the spatiotemporal and magnitude distribution of all events and the CMT results for the earthquakes MW > 1.2, revealing two distinct temporal phases with contrasting seismicity patterns (Figs. 2 and S2). Figure 2a highlights the spatiotemporal distribution of events projected onto the strike and up-dip directions. The activity starts at (0, −0.5) km and progressively extends bidirectionally in up- and down-dip directions (Phase I), and later radially with a central point at (0,0) (Phase II). After 2 months of activity, the distribution forms an almost circular cluster with slight asymmetry along the strike axis.

a The spatial distribution of events projected onto the strike and up-dip directions, forming an elliptical cluster along the fault plane. MW of moment tensors is indicated in the legend; ML (Qseek catalog) scale non-linear to enhance the visibility of small events. Colors are related to the occurrence times in (b), which shows temporal clustering and magnitude evolution (ML for catalog events, MW for CMT solutions), with dashed lines and background shading marking distinct phases linked to rupture dynamics. c compares the regional and source volume vP/vS as a function of time. Uncertainties are plotted as vertical bars. The dashed line indicates a reference ratio of 1.7. The pink and yellow shaded areas indicate the first 29 days in March 2024 and the subsequent 29–70 days, corresponding to Phase I and II, respectively.

The magnitude versus time plot in Fig. 2 reveals distinct episodic bursts of activity. The two main phases, Phase I and II, are marked by the vertical dashed lines and shading. Smaller magnitudes dominate the initial Phase I of bidirectional growth in up- and down-dip directions along the fault until March 29, 2024, corresponding to the early stages of fault activation. As the growth mode of the swarm becomes radial in Phase II, larger magnitudes emerge.

Interestingly, the ratio of P- to S-wave velocity (vP/vS) reflects the different phases (Fig. 2c). We use a double-difference Wadati method15 in moving windows to distinguish vP/vS at the activated fault (source) and averaged over the path between the swarm and seismic stations (regional) (Figs. S3–S6). While the regional vP/vS remains constant at 1.7 over the course of the swarm, the source-related vP/vS is strongly reduced in the initial phase of the swarm and returns to background values during Phase II (Figs. S4 and S5). Such behavior has been observed for NK swarms before [e.g., refs. 15,16], or during dike intrusions on Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland17, and may be explained by the flushing of newly formed pore space close to the intrusion with gaseous fluids in the initial phase of a swarm, which gradually diffuses away over periods of days and weeks.

The reduced vP/vS ratios in the early phase of the swarm correlate with a change in the relative corner frequencies, or stress drops, between earthquakes during Phases I and II. The low ambient noise levels observed in Fig. S7 confirm the high signal quality at both borehole stations, enabling reliable waveform stacking and spectral analyses presented in Fig. S8. Earthquakes of, e.g., ML = 0.7–0.8 have smaller corner frequencies—i.e., lower stress drops—during Phase I than during Phase II (Fig. S8). This analysis is based on the largest events that are available within Phase I, as magnitudes were typically small during that phase. The same magnitude range was also used in Phase II to ensure a consistent comparison. Both full waveform analyses and independent spectral analyses of the P and S waves support the consistent variations in corner frequency between the two phases. An anti-correlation between stress drops and pore pressure has been previously reported for the hydraulic stimulation in Basel18. While high pore pressure, as exhibited in Phase I, can be associated with a greater contribution of distributed fluid flow and co-seismic volume expansion, which leads to slower rupture velocities, we attribute the higher corner frequencies to the higher rupture velocities associated with dominantly shear motion during Phase II.

Hydro-fracture model for bidirectional and radial growth

The first occurrence of earthquakes at greater depths and the subsequent bursts of activity and phases at shallower depths between March and June 2024 indicate that fluids rising from greater depths may have triggered the activity. The reduced vP/vS ratios in Phase I of the 2024 swarm indicate a temporary reduction in P-wave velocities in the source region, and the increase in corner frequencies between Phase I and II suggests that the initial Mode I ruptures were increasingly overwhelmed by shear ruptures. This and the spatiotemporal patterns of the swarm phases can be discussed in the context of pore pressure diffusion [e.g., refs. 19,20] and hydro-fracture models [e.g., ref. 21].

Hydro-facture models have mostly been developed for controlled injection experiments, for example, in cases where fluids are injected into the rock at a constant downhole pressure or flow rate from a sealed wellbore. Few natural processes are known to generate overpressure (pressure above normal stress on a crack or fault), the most important being geochemical process chains during metasomatism, e.g., in the vicinity of carbonatitic melts [e.g., ref. 22], or physical buoyancy effects in closed fracture networks when fluids have lower densities than the host rock. Estimating the overpressure in natural systems at 10 km depth seems challenging at first sight. However, if injection-like processes are observed, we can base our estimate on laboratory experiments for buoyant fluid injections, e.g., in brittle gelatin [e.g., refs. 23,24]. With increasing injected volume, e.g., in the fault beneath KK, an initially penny-shaped circular fracture becomes vertically elongated until the overpressure at its upper tip is sufficient to propagate the fluid-filled fracture further upwards. After that, the fracture will not increase in lateral width and will only grow upward. Therefore, the lateral width of a fracture, together with the fracture toughness of the rock, can be used to estimate the first-order overpressure at the tip.

The static overpressure at the tip of the 3D batch is given by ΔP = 2r0Δρg, where 2r0 is the lateral width of the fracture, g is the gravitational acceleration, Kc is the fracture toughness, and Δρ is the density difference between the fluid and the surrounding rock, which itself can be related to Kc and r0 by [equation A2 in ref. 24, setting Pg = Δρg]

The volume of the fluid entrapped in a buoyant 3D fracture is \(V=\frac{4}{3}rA\approx \frac{2(1-\nu )}{G}\frac{{K}_{c}{r}^{5/2}}{\sqrt{\pi }}\) [see appendix in ref. 24], where ν is the Poisson ratio and G the shear modul of the host rock. The measured lateral extent of the seismic cloud is r0 = 200 m in Phase I and r0 = 900 m in Phase II (Fig. 3a, b). Assuming Kc ≈ 100 MPa m1/2 [e.g., ref. 25], the density differences of the first and second phases are estimated to be 1597 kg m−3 and 176 kg m−3, respectively. For example, if the density of the deep Eibenstock granite host rock is 2620 kg m−3 [see Fig. 5 in ref. 26], then the fluid densities in the first and second batches are 1020 kg m−3 and 2440 kg m−3, respectively. With these density differences and the measured lateral extent, the overpressures are estimated at ≈6 MPa and ≈3 MPa for Phases I and II. The values represent a minimum. They are independent of the question of whether the injection is driven from a self-similar, constant volume fluid batch ascending through the crust, or built up by metasomatic processes in the contact of melt and rock. The lower buoyancy in Phase II is also reflected in the different distribution of events in the up-dip direction. While the distribution of Phase I is asymmetric with a focus in the upper region (Fig. 3a), the event density in Phase II is almost symmetrical in the up-dip direction (Fig. 3b).

a Bidirectional crack growth by fluid injection with high overpressure and buoyancy, and b radial growth under low overpressure and buoyancy, leading to hydro-shearing in the tip region of the penny-shaped crack. For a simplified analysis, cracks are replaced by theoretical models with constant half-width h. Crack growth is considered quasi-static, where the crack size is associated with the fluid or pressure front, respectively.

In the following, we discuss hydro-fracture models and directed pressure diffusion for bidirectional and circular growth in more detail (Fig. 3). While hydraulic diffusion models often assume a constant permeability in the fracture zone, hydraulic fracture models consider the change in permeability (crack thickness) as the crack grows. The bidirectional growth model21 (Fig. 3a) is suitable when the overpressure is so large that the mode I stress intensity factor exceeds Kc. A circular growth as observed in Phase II occurs dominantly at low overpressure and grows by shear motion induced by increased pore pressure, known as hydro-shearing (Fig. 4b).

a Seismicity in Phase I projected onto the fault plane, illustrating bidirectional growth. b Seismicity in Phase II, highlighting radial growth. The inset curves in both panels show the normalized event densities as a function of the up-dip direction. The inlet figures at the top right of (a, b) show numerical simulations of the vertical and lateral shape of an ascending batch of buoyant fluid with Δρ of 1597 and 167 kg/m3, respectively. The color scale indicates the overpressure of the fluid in MPa. The numbers indicate the static overpressure at impact, the lateral extent, and the mean opening of the rising batch. The observed spreading of seismic events is compared with the theoretical growth models: c bidirectional growth model, with a fluid density difference of Δρ = 1597 kg m−3; and d radial growth model, with a fluid density of Δρ = 167 kg m−3. Red curves indicate model predictions, showing good agreement with observed patterns.

Bidirectional flow in a rectangular channel

In the bidirectional fracture model, the laminar fluid flow in the growing crack is controlled by the (over-) pressure at the injection point, the average half-thickness of the crack, h, the fracture toughness Kc, and the geometry of crack growth (curvature of the crack tip line). The over-pressure at the injection point is large at the beginning of crack growth, and drops to zero when growth stops. In between, the over-pressure function is largely unknown. For simplicity, we divide the pressure function into two regimes: (1) a constant over-pressure P0 during the injection phase (constant 2D flux Q), and zero over-pressure during after-growth. If an effective driving stress gradient exists, unilateral growth can develop after injection. We assume an injection line source at the center. During the injection phase, the steady-state viscous flow is described by laminar Hagen-Poiseuille flow with total volume flux Q and the mean velocity21

Here, η is the intrinsic fluid viscosity and geff is the effective driving stress gradient, defined as \({g}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}=\gamma +\partial P/\partial x=\gamma +({P}_{a}-{P}_{0})/a=-\frac{1}{a}({P}_{0}-\frac{3}{4}\sqrt{\pi /a}{K}_{c})\), where γ = Δρg is the static driving stress gradient due to buoyancy, P0 is the injection pressure at the injection point, and Pa is the pressure in the channel at length a from the injection point.

Although the solution represents a steady-state flow, it can be used to approximate slow crack growth for hydro-fracture experiments. Therefore, we assume that the hydro-fracture has a time-dependent length a that increases with velocity v so that the laminar flow is not disturbed. Such a process requires that the pressure at the fracture tips adjusts such that for each instantaneous time, the stress intensity K± at the crack tips of both wings equals the fracture toughness Kc of the rock. As shown in ref. 21, the asymmetric growth velocity v1/2 of the two wings during the injection phase from time t1 to t2 can be equated by

An intrusion associated with an injection under high, almost constant overpressure that abruptly ceases leads to a seismicity front initially growing bidirectionally with higher velocities upwards than downwards. Then, in the so-called “bleed-off” phase, there is a one-sided growth of the seismicity front upwards, which is accompanied by a so-called “back-front of seismicity generation,” which only propagates upwards from the center of the opening fracture. The back-front develops when the internal pressure in the fracture re-organizes into a linear function with depth. With further growth at the longer wing, the point of maximal opening migrates together with the upper crack tip and marks the seismicity back-front behind where the Coulomb stress in the surrounding rock reduces and no longer increases. As shown in ref. 21, the time evolution of the back-front and the final length of the hydro-fracture are independent of other parameters and cannot be varied.

The seismicity cloud of the KK swarm shows during Phase I exactly this predicted pattern (Fig. 4a, c) and can therefore be simulated by the bidirectional growth model. Our modeling results indicate an injection phase lasting 5 days (from March 16, 2024, at 19:00 UTC, to March 22, 2024) at an overpressure of about 6 MPa (pressure above normal stress on the fault) and Kc ≈ 100 MPa m1/2, followed by a bleed-off phase over 7 days until March 29, 2024. Although the fluid viscosity is difficult to determine because the fracture mechanics modeling makes simplified assumptions about the crack opening, the modeling shows that viscosities as small as a few Pa s are sufficient to reproduce the observed growth of the seismicity cloud. The observed one-sided back-front agrees with the predictions. This is a strong indication that hydro-fracturing was the dominant process in Phase I, resulting from the intrusion of a low-viscosity light fluid into a dense rock. As expected from this model, the observed earthquake density in Phase I is asymmetric in the up-dip direction, with a thick bulge at the top (Fig. 4a).

Low-pressure injection leading to radial diffusion and hydro-shearing

In Phase II (t > 29d, March 29, 2024), the seismicity cloud continued to grow, but now radially, starting from the upper end of the previously fractured segment on the fault (Fig. 4b, d). Slow radial growth of a seismic cloud is often explained by pore pressure diffusion [e.g., ref. 27], inducing both shear and opening-mode fractures. Aseismic slip may also play a role28,29,30. Diffusion models suggest a radial growth proportional to \(\sqrt{t}\), equivalent to a radial growth velocity v proportional to r−1. In a fracturing model, radial growth is expected when both buoyancy forces and injection pressures are lower [e.g., ref. 31]. In terms of growth rate, the circumferential length of the crack increases with time, in contrast to the bidirectional growth in Phase I. Therefore, the speed of the seismicity front decreases with increasing radius of the activated fault patch, even if the inflow is constant.

The pressure function from injection with pressure P0 at radius r0 and constant total flux Q into a confined aquifer with half thickness h is described by the Thiem equation, where P(r)−P0 varies logarithmically with radial distance \(\ln (r/{r}_{0})\). The functional form is similar to the problem of radial flow between two parallel disks. Using the same concept of a quasi-static growth of the fractured, penny-shaped area on the fault, growing together with the pressure front, and considering the stress intensity factor of a penny-shaped crack, the radial growth velocity can be described by

Note that the total flux has a unit of m3/s. The time needed to fracture a radius r is calculated by the integral \(t(r)=\int\limits_{0}^{r}1/v(r^{\prime} )dr^{\prime}\). The expected velocity is proportional to \({\left[(r-{r}_{0})/({r}^{4}\ln (r/{r}_{0}))\right]}^{1/3} \sim {r}^{-4/3}\), which is similar to the predictions of pore pressure diffusion.

Our modeling shows good agreement with the observed growth of the seismicity cloud in Phase II (Fig. 4d), if a lower injection pressure of about 3 MPa and Kc ≈ 100 MPa m1/2 are used. The radial instead of bidirectional growth is explained by a higher density of the inflowing fluid. This, together with the lower injection pressure, could also explain that no significant back-front is observed after the inflow has stopped, contrary to borehole injection experiments [e.g., ref. 32]. The injection under low overpressure predicts a symmetrical event density around the center in the up-dip direction, as observed (Fig. 4b).

The role of magmatic fluids in driving swarms—discussion

Swarm activity also occurred in the KK region in 1897, exhibiting multiple phases and similar source mechanisms to the 2024 sequence, allowing for a meaningful comparison between the two swarms (Fig. S9). The recent KK swarm sequence began with initial events in December 2023, preceding the main activity by 3 months. These earthquakes were located approximately 1 km deeper and 2 km north of the subsequent swarm activity, which intensified on March 16, 2024. During the first 5 days of the main activity, a high rate of small-magnitude earthquakes indicated the injection of low-density fluids into a pre-existing normal fault, with bidirectional fracture growth over a lateral width of 400 m and a vertical length of about 1.1 km. According to our modeling, the initial overpressure was about 6 MPa. After the cessation of injection, the fracture continued to grow upward in the fault by about 100 m for 7 days, where a back-front of ceasing seismicity developed behind the upper seismicity front. This asymmetric pattern strongly supports the injection of light fluids with an estimated density of around 1020 kg/m3, assuming a density of the granitic host rock of 2620 kg/m3 26.

The pressurization of the fault could be explained by different processes accumulating CO2. For instance, a buoyancy-driven fracture could have arrived (Fig. 5), originally formed from the degassing of carbonatitic melts at great depth or during ascent. Alternatively, pressurization could have formed by metasomatic processes close to the fault when carbonatitic melts interact with host rocks [e.g., ref. 33].

The smaller batch with volume V1 (Phase I) arrives first, with a larger overpressure ΔP1. The batch with volume V2 feeding Phase II of the swarm has a larger lateral size 2r1 and a smaller overpressure ΔP2. Estimated parameters and literature values for the density and viscosity of CO2 (see supplementary material) and carbonatitic melt [e.g., ref. 76] are given in the upper and lower table on the left, respectively. Both the small overpressure in Phase II and the small density-related buoyancy facilitate hydro-shearing in the fault zone, triggering larger earthquakes.

The filling of pore space by CO2 or water could eventually explain the sudden decrease in vP while vS remains less affected. However, very small vP/vS ratios below 1.4 indicate possible vaporization of fluids associated with an expansion of pore space. Because CO2 is in a supercritical state at a depth of 10 km, only the water component can eventually vaporize (Fig. 6) in the region of the crack tip cavity where tensional suction forces can become extremely large if the host rock pore space is undrained34. Distributed hydro-fracturing and brecciation in the aurora of carbonatitic intrusions can be violent [e.g., ref. 22] and may play a role. Such zones have been highlighted by a reduction of gravity and low vP35. Fracture-induced anisotropy may also affect vP/vS, but studies on this topic are beyond the scope of this article.

After March 29, 2024, the swarm experienced a second phase of activity in which it grew radially within the fault to a radius of about 950 m, starting at the upper end of the seismicity in Phase I. A backfront similar to Phase I is not observed. Because of this changing pattern, the arriving buoyancy-driven fracture must have had different fluid properties and thus different dimensions. Using a similar modeling approach as before, we estimate an initial overpressure during Phase II of only 3 MPa and a fluid density of about 2440 kg/m3. This indicates that after the injection of CO2, a heavier melt or melt brine flowed into the fault (Fig. 5). During this phase, the earthquakes became larger and the corner frequency of their rupture increased, indicating that shearing was more prominent than opening. The lower injection pressure could explain why hydro-shearing became dominant [see ref. 36, for mechanism]. A more detailed analysis of the source spectra and corner frequencies could support these interpretations, but this lies outside the objectives of the present study.

To date, a number of alternative models have been proposed for the Vogtland region. Purely tectonic models based on the interaction of fault networks [e.g., refs. 37,38] have now been ruled out, as modern geodetic data show only minor tectonic deformations, difficult to explain, repeating swarms. Proposals that the swarms are triggered by exogenous environmental factors can also be ruled out39. Most proposals assume transients of CO2 flow, sometimes linked to so-called valve mechanisms in fault zones [e.g., ref. 40]. Decades of extensive measurements in Vogtland region mofettes show that flow transients can be triggered by different mechanisms and are therefore difficult to interpret [e.g., ref. 41]. A possible problem with the flow-controlled valve model is that already small volumes of CO2 are sufficient to build up the excess pressure to reopen sealed fault patches, making it difficult to explain month-long swarms alone. However, detailed analyses show that the swarm patterns result from a combination of fluid intrusion and earthquake interactions driven by co- and postseismic stress transfer, which can explain their duration42,43,44. Similarly, CO2 alone, which is light and tends to move upwards, cannot explain the incremental growth of the NK swarms in about 9 km depth horizontally over the length of more than 20 km since 1985, if not an unbroken sealed layer is assumed at approximately 7 km depth. Although we cannot rule out that previously suggested processes, such as CO2-driven pore-pressure diffusion in combination with earthquake-induced stress changes and rheological boundaries or fault complexity, might also explain the observations, our suggested model provides a straightforward and comprehensive explanation for the observed rapid bidirectional and radial migration phases and vP/vS changes.

Massive CO2 emissions at mofettes and springs extend over an area of 60 × 40 km2, including the locations of different swarms. Helium isotopes in springs indicate that the CO2 is mantle-derived, facilitated by the upwelling and magmatic underplating45. Mantle xenoliths from the tephra deposits in maars indicate that alkaline melts intrude at depths of 45–25 km46,47, which is a favorable condition for the development of light and low-viscosity carbonatitic melts during ascent. Such magmatic processes at Moho depths have long lifecycles, which could also explain the persistent occurrence of swarms, including the reactivation of the KK swarm after a hundred years. Some previous studies suggested that melts were present at the depths of the swarms. This is supported by geological maps that indicate that earthquake swarms occur predominantly close to old magmatic intrusions [e.g., ref. 48]. Reference31 studied the aspect ratio of the seismicity cloud of individual swarms beneath NKC and suggested that melts and CO2 separate during a swarm to explain both upwards and lateral/downwards migration of earthquakes. The analyses estimated a mean overpressure during the later phase of a swarm in 2000 to be around 5 MPa, while a shear stress between 9 and 17 MPa was effective. Other investigations of repeating seismicity clouds yielded an initial overpressure at the beginning of the NK swarm in 2008 of 15–25 MPa5.

Non-differentiated peridotitic melts [e.g., basalts/nephelinites, see refs. 49,50] do not align well with our observations. They typically have high densities, meaning large volumes of melt must accumulate in vertical fractures before the overpressure at the tip is sufficient to cause instability and the entire batch to ascend through the crust. These large-volume intrusions induce relatively strong earthquakes, up to magnitude MW ~ 5, when they penetrate the brittle part of the crust. However, our maximum magnitudes are below MW ~ 3. Additionally, the viscosity of silicate-rich melts may be too high for them to propagate through grain boundaries and faults in the brittle crust to generate hydro-shearing.

This suggests that small volumes of light, low-viscosity melts have been available in our case, from which CO2 is also released. Alkaline or calcium carbonatites could fulfill these conditions. The rise of carbonatite melts to the upper crust overcomes some of the limitations mentioned above. Carbonatites have very low viscosities, similar to water, and can therefore migrate slowly through the crust in small volumes and penetrate grain boundaries and faults without causing strong earthquakes. Their ascent along pre-existing weak zones or in the vicinity of existing intrusions or plutons may explain why earthquake swarms reawaken in the same place after a long time. Another characteristic of carbonatite melts is that they produce CO2 and H2O during their ascent and in contact with the surrounding rock [e.g., ref. 51]. The time scales of this interaction are not fully understood, but can be violent [e.g., pneumatic jackhammer model, ref. 51] as networks of hydraulic fractures and breccia zones are documented in fenite deposits in the volume around carbonatitic intrusions.

Melt-rock interaction and the related hydrothermal systems may lead to the formation of ores and minerals, which have been mined for centuries in the Vogtland and close to Klingenthal. For example, the KK swarm is located on the border of the Eibenstock granite pluton, which covers an area of more than 30 km2, on the edge of which feldspar, barite, and apatite were mined52.

Conclusions

Magmatic fluids in the NW Bohemia/Vogtland swarm region develop and accumulate in the upper mantle and at the crust-mantle boundary. When such deep reservoirs evolve and become unstable, the lower-density melts and fluids may separate and rise further through the crust. When these magmatic fluids encounter the brittle-ductile boundary and interact with pre-existing fault zones, seismic swarms can occur.

Our analysis suggests that the 2024 Klingenthal–Kraslice earthquake swarm—the first significant seismic activity in the area in over 125 years—was driven by such fluid-fault interaction, providing a concrete example of mantle-derived, carbonate-rich fluids interacting with bedrock at the brittle-ductile boundary. This interaction caused 3 months of intense earthquake activity, activating a previously unidentified normal fault at a depth of 10 km. The swarm underwent an unexpected evolution from vertical bidirectional growth to radial growth of the seismic cloud over a period of 70 days. The vP/vS ratio in the source region decreased significantly during bidirectional growth. Source spectra also indicate a different fracture mode during this phase.

The spatial and temporal evolution of the swarm could be modeled using a hydro-fracture model that provides constraints on overpressure, viscosity, and density of the injected fluids. The first phase, which lasted 5 days and involves bidirectional vertical growth, is characterized by very low viscosity and an overpressure of about 6 MPa associated with a higher buoyancy force in the intruding fluid batch of a volume of about 320 m3 ascending from below. This indicates a high H2O or CO2 content with an average density of about 1040 kg/m3.

During the second phase of radial growth, the density difference between the intruded fluids and the host rock decreases, which can be explained by the influx of melt or melt brine with a density of about 2440 kg/m3 but still a very low viscosity. Although the estimated intruded volume is larger at about 13,700 m3, the realized overpressure is smaller at only about 3 MPa, favoring hydro-shearing events and generating earthquakes of magnitude greater than 1.2. Carbonatitic melts would explain such parameters.

Our study exemplifies how seismicity patterns can identify sequential injections of light CO2 and melt-brines of very low viscosity and with densities much smaller than that of the host rock in 10 km depth. We propose that the NW Bohemia/Vogtland swarm region is an area where the ascent of low-viscosity melts into the upper crust, as well as the metasomatism and fenitization of carbon-rich melts, can be studied as they develop today.

Methods

Earthquake detection and localization

We generated the earthquake catalog using Qseek, an automatic waveform-based earthquake detector and locator, as detailed in ref. 53. Qseek combines seismic phase arrival annotations provided by neural network phase pickers and waveform stacking with an efficient adaptive octree search. The resolution of the search volume is iteratively refined toward the seismic source location, enabling fast and accurate detection. The local magnitude was calculated using the formula from ref. 54. Moment magnitude calculations from peak ground motions are included55. Location accuracy is further enhanced by incorporating station-specific corrections (SST) and source-specific station terms (SSST). The method has been validated for multiple large seismic datasets across various regions and geological settings53,56.

Methods implementing SSST can achieve relative locations similar to double difference methods [e.g., refs. 57,58]. In our case, SSSTs were derived from a regional application of Qseek to NW Bohemia and Vogtland for the years 2018 to 2024, including the KK swarm. The waveform attribute stacking approach with static station correction terms, a preliminary version of the Qseek approach, was directly compared to a high-resolution double difference relative location applied to a NW Bohemia earthquake swarm in 2008 using stations from WEBNET59. Results showed very comparable high precision relative and absolute locations, where data errors were in the range between 0.2 and 0.5 km. Compared to 2008, the density and coverage of stations have significantly improved, so we estimate that the uncertainties from the updated Qseek application are in the range of 0.1 km.

The seismic catalog was created using the local velocity model from ref. 60, a modified model version in ref. 61. Waveform data were sourced from three borehole arrays (1D.LWS00, 1D.TIS00, 1D.STC00) of the ICDP (Drilling the Eger Rift) Eger Virtual Network62, along with surface stations operated by WEBNET54,63, SXNET64, TSN65, and BW66, as described in the Data Availability section.

Centroid moment tensor inversion

We applied moment tensor inversion to earthquakes with MW > 1.2 for the 2024 KK swarm (Fig. 1) using a joint inversion of waveform and first motions56. Uncertainties were estimated using a Bayesian bootstrap approach implemented in the open source software Grond67, which combines non-linear inversion and bootstrapping.

The source model parameterization includes centroid location, depth, time, moment tensor components, and optional source duration. Green’s functions (GFs) were precomputed using Qseis68 for a sampling rate of 100 Hz, covering distances of 0–80 km and source depths of 7–13 km with 100 m spacing, based on the velocity model of ref. 60. Theoretical travel times and phase polarities were calculated using the Cake tool69. The inversion minimizes the L1 norm misfit between observed and synthetic data70, balancing weights for signal amplitude, source-receiver distance, phase type, and data type.

Waveforms were inverted in time windows of ±0.25 s around P- and S-wave arrivals in the time domain, with shifts of ±0.15 s allowed for synthetic traces. Approximately 4000 manually verified P- and S-wave arrivals were used, with a frequency range of 1.0–3.0 Hz. After 100,000 iterations, 64 earthquakes with robust centroid locations, low misfits, and sufficient azimuthal coverage were selected for further interpretation (Fig. 1). Full waveform fits are available as online reports and interactive web-based visualizations (see “Data availability section”).

Temporal changes in v P/v S ratios in the swarm volume

The double difference Wadati method was developed by ref. 15 to estimate temporal changes of γ = vP/vS in the source region of an earthquake swarm. The traditional Wadati diagram uses the arrival time difference between the S- and P-waves, tS−tP plotted over tP, for all stations recording the event, which linearly depends on γ and the origin time of the event. Averaging γ for many events provides an average ratio for the crust beneath the seismic network.

We use time differences between P-wave arrivals at each station for pairs of events. Events are described as point sources. The same applies to S-wave arrivals. These double differences are sensitive to velocity changes between the different sources, as effects between the swarm and the stations are canceled out. The challenge of the double difference Wadati approach is to have precise pick times, TP and TS, with accuracies of 4 or 8 ms, respectively, in order to resolve variations in arrival time differences over a path length of 1–2 km. In our case, we take advantage of the 250 Hz sampling rate on all WEBNET stations. Note that borehole chains in Tisova (1D.TIS00), Landwüst (1D.LWS00), and Studenec (1D.STC00) sample with 400 or 1000 Hz.

The theory and inversion approach is described in ref. 15, where the following equations are minimized,

where TSij and TPij are S and P wave arrival times at station j from event i, \({T}_{Pij}^{d}\) is the event-wise demeaned P arrival time. δi is a constant that can be estimated for each event. The symbol Δt refers to arrival time differences. The index l refers to unique permutations of event pairs. The minimum is found from a grid search over possible values of γ, where an L1 norm was implemented.

We only considered earthquakes within a 23 km3 cube centered on the swarm that with at least 14 accurate picks with probabilities greater than 0.8. Stations with a TS−TP difference of more than 4 s and outliers with a deviation of more than 0.05 s from the Wadati curve in a regional (conventional) Wadati plot were removed. We also ensured a systematic input dataset by selecting a set of stations that consistently provided picks for every included earthquake. We tested different station ensembles. Stations from which rays emerge perpendicular to the fault result in very small (or zero) arrival time differences for event pairs and are therefore not suitable for studying velocity ratios. Those associated with rays along the activated fault produced larger arrival time differences that exceeded the pick accuracy. We tested different ensembles of stations. While the general result and trend in vP/vS remained unchanged, the most convincing examples involved stations located approximately 15 km from the sources. We ultimately employed stations WB.LOUD, SX.WERN and SX.WERD for the analysis (see Figs. S1 and S3–S6). Uncertainties of vP/vS in Fig. 2c represent standard deviations estimated from the least squares of residuals.

Phase diagrams of C O 2 and H 2 O

The phase diagram of CO2 is of particularly interesting for reconstructing density and compressibility as a function of depth and temperature and identifying areas where CO2 and H2O undergo phase transitions that could potentially lead to pressure build-up. Figure 6 shows projections of the state of CO2 and H2O in a P-T plane, and the density ρ and P-wave velocity vP along a linear P-T path in the crust from 0 to 10 km depth. Phase diagrams were calculated from refs. 71,72. Density and velocities have been cross-checked against NIST Standard Reference Database 69 for thermophysical properties of fluids73.

At 10 km depth, the ambient pressure is in the range of 270 MPa and the temperature is about 580 K. CO2 is clearly in the supercritical domain and behaves like a fluid with a density of about 1000 kg/m3. In contrast, H2O in 10 km depth is in the fluid state in the subcritical domain and has a density of only about 900 kg/m3. While the density of CO2 continuously decreases when ascending through the crust (Fig. 6b), the density of water increases (Fig. 6d). The self-expansion of CO2 would increase the volume of a batch of constant mass ascending through the crust, and the increase in vertical length of the batch would additionally increase the overpressure at the upper tip of the self-similar fracture. Both could lead to an accelerated ascent, as long as the lithostatic pressure gradient is constant. In contrast, a batch filled with H2O would not necessarily accelerate as the volume and tip overpressure both would decrease along the ascent path. If CO2 and H2O would co-exist in the same fracture or fault, CO2 would move downward while H2O would be pushed upward to 10 km depth. In a depth of 6 km or less, an opposite behavior is predicted, and CO2 would lie on top of the water column.

Data availability

The seismic data used in this study are available through the FDSN data center network under the following codes: 1D (Longterm monitoring of swarm earthquakes in the western Eger rift, https://doi.org/10.14470/6Q705117), operated as part of the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP); TH (Thüringer Seismologisches Netz - TSN, https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/TH), operated by Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany; SX (SXNET - Saxon Seismic Network, https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/SX), operated by the University of Leipzig; BW (BayernNetz - BW, https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/BW), operated by the Bavarian Seismological Network, Germany; GQ (German Strong Earthquake Network), operated by Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), Germany. The seismic data from the ICDP-EGER virtual network are archived at GFZ Data Services (https://doi.org/10.14470/SN852091) and can also be accessed through the virtual network. The fault inventory in Fig. 1 is compiled from three different sources: (1) Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt - LfU Bayern (https://www.lfu.bayern.de/gdi/wms/geologie/dgk25), (2) Sächsisches Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (https://www.geologie.sachsen.de/artus-2-aktive-stoerungszonen-27587.html), and (3) Czech Geological Survey (https://cgs.gov.cz/en/maps-and-data/web-services). Waveform data used in the moment tensor inversion and the seismic catalog produced in this study can be found at the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17703774). The online reports of the results of each earthquake resolved by moment tensor inversion (e.g., waveform fits and uncertainties) can be accessed interactively via the following link: (https://data.pyrocko.org/publications/grond-reports/2024-klingenthal). The earthquake detection and localization framework Qseek can be found under the link (https://pyrocko.github.io/qseek). The probabilistic source inversion method with the Grond framework is available at the link (https://pyrocko.org/grond) under the Pyrocko environment (https://pyrocko.org). The maps are prepared using the PyGMT (https://www.pygmt.org), GMT (ref. 74), Python (http://www.python.org), Matplotlib (https://matplotlib.org) visualization packages and QGIS software (https://www.qgis.org).

References

Credner, H. Die Sächsischen Erdbeben während der Jahre 1889 bis 1897, insbesondere das Böhmische Erdbeben vom 24. October bis 29. November 1897. Abh. Math. Phys. Cl. K. Sächs. Ges. Wiss. 24, 315–398 (1898).

Geissler, W. H. et al. Seismic structure and location of a CO2 source in the upper mantle of the western Eger (Ohře) Rift, central Europe. Tectonics 24, 1–23 (2005).

Rohrmüller, J. et al. Reconnaissance Study of an Inferred Quaternary Maar Structure in the Western Part of the Bohemian Massif Near Neualbenreuth, Ne-Bavaria (Germany). Int. J. Earth Sci. (Geol. Rundsch.) 107, 1381–1405 (2018).

Dahm, T. et al. Eger Rift ICDP: An Observatory for Study of Non-Volcanic, Mid-Crustal Earthquake Swarms and Accompanying Phenomena. Sci. Drill. 16, 93–99 (2013).

Hainzl, S., Fischer, T. & Dahm, T. Seismicity-based estimation of the driving fluid pressure in the case of swarm activity in Western Bohemia. Geophys. J. Int. 191, 271–281 (2012).

Credner, H. Die vogtländischen Erdbebenschwärme während des Juli und des August 1900. Ber. ü. Verh. Kgl. Sächs. Ges. Wiss. Leipzig 52, 153–177 (1900).

Credner, H. Der vogtländische Erdbebenschwarm vom 13. Februar bis zum 18. Mai 1903. Und seine Registrierung durch das Wiechertsche Pendelseismometer in Leipzig. Abhandlungen der Mathematisch-Physischen Klasse der Königlich-Sächsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften (ed. Königlich Sächsische Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften) 419–530 (Teubner, 1904).

Etzold, F. Die sächsischen Erdbeben während der Jahre 1907–1915. Abhandlungen der Mathematisch-Physischen Klasse der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 218–428 (Teubner, 1920).

Neunhöfer, H. & Meier, T. Seismicity in the Vogtland/Western Bohemia earthquake region between 1962 and 1998. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 48, 539–562 (2004).

Fischer, T. et al. ICDP drilling of the Eger Rift observatory: magmatic fluids driving the earthquake swarms and deep biosphere. Sci. Drill. 31, 31–49 (2022).

Plenefisch, T. & Klinge, K. Temporal variations of focal mechanisms in the Novy Kostel focal zone (Vogtland/NW-Bohemia)—comparison of the swarms of 1994, 1997 and 2000. J. Geodyn. 35, 145–156 (2003).

Vavryčuk, V., Adamová, P., Doubravová, J. & Horálek, J. Moment tensor catalogue of earthquakes in West Bohemia from 2008 to 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 2179–2194 (2022).

Wirth, W., Plenefisch, T. & Klinge, K. et al. Focal mechanisms and stress field in the region Vogtland/Western Bohemia. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 44, 126–141 (2000).

Dahm, T., Sileny, J. & Horalek, J. Comparison of moment tensor solutions for the January 1997 West Bohemia earthquake swarm. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 44, 233–250 (2000).

Dahm, T. & Fischer, T. Velocity ratio variations in the source region of earthquake swarms in NW Bohemia obtained from arrival time double-differences. Geophys. J. Int. 196, 957–970 (2014).

Bachura, M. & Fischer, T. Detailed velocity ratio mapping during the aftershock sequence as a tool to monitor the fluid activity within the fault plane. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 453, 215–222 (2016).

Masihi, A. & Fischer, T. In-Situ Vp/Vs ratio variations in seismic swarms as indicator of magmatic processes: Fagradalsfjall volcanic activity, SW Iceland. Geophys. J. Int. 241, https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggaf122 (2025).

Goertz-Allmann, B. P., Goertz, A. & Wiemer, S. Stress drop variations of induced earthquakes at the Basel geothermal site. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L09308 (2011).

Shapiro, S. A., Huenges, E. & Borm, G. Estimating the crust permeability from fluid-injection-induced seismic emission at the KTB site. Geophys. J. Int. 131, F15–F18 (1997).

Shapiro, S., Krüger, O. S. & Dinske, C. Probability of inducing given-magnitude earthquakes by perturbing finite volumes of rocks. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 3557–3575 (2013).

Dahm, T., Hainzl, S. & Fischer, T. Bidirectional and unidirectional fracture growth during hydrofracturing: role of driving stress gradients. Geophys. J. Int. 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JB006817 (2010).

Elliotta, H. et al. Fenites associated with carbonatite complexes: a review. Ore Geol. Rev. 93, 38–59 (2018).

Takada, A. Experimental study on propagation of liquid-filled crack in gelatin: shape and velocity in hydrostatic stress conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 8471–8481 (1990).

Dahm, T. On the shape and velocity of fluid-filled fractures in the Earth. Geophys. J. Int. 142, 181–192 (2000).

Rivalta, E. & Dahm, T. Acceleration of buoyancy-driven fractures and magmatic dikes beneath the free surface. Geophys. J. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.02962.x (2006).

Hofmann, Y., Jahr, T. & Jentzsch, G. Three-dimensional gravimetric modelling to detect the deep structure of the region Vogtland/NW-Bohemia. J. Geodyn. 35, 209–220 (2003).

Shapiro, S. & Dinske, C. Fluid-induced seismicity: pressure diffusion and hydraulic fracturing. Geophys. Prospect. 57, 301–310 (2009).

De Barros, L., Wynants-Morel, N., Cappa, F. & Danre, P. Migration of fluid-induced seismicity reveals the seismogenic state of faults. J. Geophys. Res. 126, e2021JB022767 (2021).

Danré, P., De Barros, L., Cappa, F. & Ampuero, J.-P. Prevalence of aseismic slip linking fluid injection to natural and anthropogenic seismic swarms. J. Geophys. Res. 127, e2022JB025571 (2022).

Danré, P., Garagash, D., De Barros, L., Cappa, F. & Ampuero, J.-P. Control of seismicity migration in earthquake swarms by injected fluid volume and aseismic crack propagation. J. Geophys. Res. 129, e2023JB027276 (2024).

Dahm, T., Fischer, T. & Hainzl, S. Mechanical intrusion models and their constraints on the density of fluids injected in the NW Bohemia swarm region at 10 km depth. Stud. Geofis. 52, 529–548 (2008).

Parotidis, M., Shapiro, S. & Rothert, E. Back front of seismicity induced after termination of borehole fluid injection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018978 (2004).

Vasyukova, O. & Williams-Jones, A. Carbonatite metasomatism, the key to unlocking the carbonatite-phoscorite-ultramafic rock paradox. Chem. Geol. 602, 120888 (2022).

Rubin, A. Tensile fracture of rock at high confining pressure: implications for dike propagation. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 15919–935 (1993).

Vartiainen, H. & Paarme, H. Geological characteristics of the Sokli carbonatite complex, Finland. Econ. Geol. 74, 1296–1306 (1979).

Yuan, Y., Xu, T., Moore, J., Lei, H. & Feng, B. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modeling of hydro-shearing stimulation in an enhanced geothermal system in the Raft River Geothermal Field, USA. Rock Mech. Rock. Eng. 53, 5371–5388 (2020).

Bankwitz, P., Schneider, G., Kämpf, H. & Bankwitz, E. Structural characteristics of epicentral areas in central Europe: study case Cheb Basin (Czech Republic). J. Geodyn. 35, 5–32 (2003).

Heinicke, J., Stephan, T., Alexandrakis, C., Gaupp, R. & Buske, S. Alteration as possible cause for transition from brittle failure to aseismic slip: the case of the NW-Bohemia/Vogtland earthquake swarm region. J. Geodyn. 124, 79–92 (2019).

Vlček, J., Beránek, R., Fischer, T. & Vilhelm, J. Earthquake swarms in West Bohemia are most likely not rain triggered. J. Geodyn. 150, 101908 (2022).

Fischer, T., Matyska, C. & Heinicke, J. Earthquake-Enhanced Permeability - Evidence from Carbon Dioxide Release Following the ML 3.5 Earthquake in West Bohemia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 460, 60–67 (2017).

Woith, H. et al. Effect of pressure perturbations on CO2 degassing in a mofette system: the case of Hartoušov, Czech Republic. Geosciences 13, 2 (2023).

Hainzl, S. & Fischer, T. Indications for successively triggered rupture growth underlying the 2000 earthquake swarm in Vogtland/NW Bohemia. J. Geophys. Res. 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JB001865 (2002).

Hainzl, S. Seismicity patterns of earthquake swarms due to fluid intrusion and stress triggering. Geophys. J. Int. 159, 1090–1096 (2004).

Hainzl, S. & Ogata, Y. Detecting fluid signals in seismicity data through statistical earthquake modeling. J. Geophys. Res. 110, B05S07 (2005).

Hrubcová, P. et al. Active magmatic underplating in Western Eger Rift, Central Europe. Tectonics 36, 2846–2862 (2017).

Daskalopoulou, K. et al. Characterisation of deep intra-continental magma reservoirs—insights from noble gases and p-T estimates into the western Eger Rift (Czech Republic). Chem. Geol. 681, 122722 (2025).

Geissler, W., Kämpf, H., Seifert, W. & Dulski, P. Petrological and seismic studies of the lithosphere in the earthquake swarm region Vogtland/NW Bohemia, Central Europe. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 159, 33–69 (2007).

Heinicke, J. et al. Neogene and Quaternary dikes and related joints as conduits for recent juvenile degassing: case studies from the seismically active region of NW-Bohemia, Czech Republic. Bull. Volcanol. 85, 38 (2023).

Mrlina, J., Kämpf, H., Geissler, W. & Van den Bogaard, P. Assumed quaternary maar structure at the Czech/German border between Mytina and Neualbenreuth (western Eger rift, Central Europe): geophysical, petrochemical and geochronological indications. Z. Geol. Wiss. 35, 213–230 (2007).

Hrubcová, P. et al. Two Small Volcanoes, One Inside the Other: Geophysical and Drilling Investigation of Bažina Maar in Western Eger Rift. Earth Space Sci. 10, e2023EA003009 (2023).

Walter, B. F. et al. Fluids associated with carbonatitic magmatism: a critical review and implications for carbonatite magma ascent. Earth Sci. Rev. 215, 103509 (2021).

Ilgner, E.-A. & Hahn, W. in Die Schwerspatlagerstätte Brundöbra und das Schwerspatvorkommen Schnarrtanne im Ostvogtland/Westerzgebirge (ed. Brause, H.) 1–122 (Sächsische Landesamt für Umwelt und Geologie, 1998).

Isken, M. et al. Qseek: a data-driven framework for automated earthquake detection, localization and characterization. Seismica 4, 1283 (2025).

Horalek, J., Fischer, T., Bouskova, A. & Jedlicka, P. Western Bohemia/Vogtland region in the light of the WEBNET network. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 44, 107–124 (2000).

Dahm, T., Kühn, D., Cesca, S., Isken, M. & Heimann, S. Earthquake moment magnitudes from peak ground displacements and synthetic Green’s functions. Seismica 3, 1205 (2024).

Büyükakpinar, P. et al. Understanding the seismic signature of transtensional opening in the Reykjanes Peninsula rift zone, SW Iceland. J. Geophys. Res. 130, e2024JB029566 (2025).

Lin, G. & Shearer, P. Tests of relative earthquake location techniques using synthetic data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 110, B04304 (2005).

Nooshiri, N., Saul, J., Heimann, S., Tilmann, F. & Dahm, T. Revision of earthquake hypocentre locations in global bulletin data sets using source-specific station terms. Geophys. J. Int. 2, 589–602 (2016).

Grigoli, F. et al. Automated microseismic event location using Master-Event Waveform Stacking. Sci. Rep. 6, 25744 (2016).

Eulenfeld, T., Dahm, T., Heimann, S. & Wegler, U. Fast and robust earthquake source spectra and moment magnitudes from envelope inversion. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 112, 878–893 (2021).

Málek, J., Horálek, J. & Janský, J. One-Dimensional qP-wave velocity model of the upper crust for the west Bohemia/Vogtland earthquake swarm region. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 49, 501–524 (2005).

Dahm, T., Ohrnberger, M., Vollmer, D., Woith, H. & Isken, M. Longterm monitoring of swarm earthquakes in the western Eger rift. https://geofon.gfz.de/waveform/archive/network.php?ncode=_ICDPEGER (2024).

Institute of Geophysics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. West Bohemia local seismic network. https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/WB/ (1991).

University of Leipzig. Sxnet Saxon Seismic Network. https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/SX/ (2001).

Institut fuer Geowissenschaften, Friedrich-Schiller-Universitaet Jena. Thüringer Seismologisches Netz. https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/TH/ (2009).

Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Geophysical Observatory, University of Munchen. Bayernnetz. https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/BW/ (2001).

Heimann, S. et al. Grond—a probabilistic earthquake source inversion framework. http://pyrocko.org/grond/docs/current/ (2018).

Wang, R. A simple orthonormalizing method for stable and efficient computations of Green’s functions. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 89, 733–741 (1999).

Heimann, S. et al. Pyrocko—an open-source seismology toolbox and library. GFZ Data Services. https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.2.1.2017.001 (2017).

Kühn, D., Heimann, S., Isken, M. P., Ruigrok, E. & Dost, B. Probabilistic moment tensor inversion for hydrocarbon-induced seismicity in the Groningen gas field, the Netherlands, part 1: testing. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 110, 2095–2111 (2020).

Span, R. & Wagner, W. A new equation of state for carbon dioxide covering the fluid region from the triple-point temperature to 1100 K at pressures up to 800 MPa. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 31, 1509–1596 (1994).

Wagner, W. & Pr"u, A. Thermodynamic properties of ordinary water. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 25, 378–535 (2002).

Lemmon, E. W., Bell, I. H., Huber, M. L. & MvLinden, M. O. in Thermophysical Properties of Fluid Systems (eds Linstrom, P. & Mallard, W.) NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69 20899 (National Institute of Standards and Technology) (2009).

Wessel, P., Smith, W. H. F., Scharroo, R., Luis, J. & Wobbe, F. Generic mapping tools: improved version released. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 94, 409–410 (2013).

Neunhöfer, H. in Überwachung nichttektonischer Erderschütterungen in Mittel-/Ostdeutschland mit lokalen seismischen Stationen (eds Neunhöfer, H., Börngen, M., Junge, A. & Schweitzer, J.) 201–206 (Jubiläumsschrift, Deutsche Geophysikalische Gesellschaft, 1997).

Kono, Y. et al. Ultralow viscosity of carbonate melts at high pressures. Nat. Commun. 5, 5091 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding of the borehole and surface array by ICDP (ICDP-EGER project). Additional stations were built in the framework of the Central European Volcanic Province Observatory (CVO) of GFZ. P.B. was funded by the DFG project “Characterizing source properties of NW Bohemia/Vogtland earthquake swarms exploiting novel network and waveform processing tool (CHASING),” BU4346/1-1, project number: 517982028. We acknowledge the ICDP-EGER data inventory provided by GFZ Data Services and collaborating institutions, comprising seismic datasets collected in the NW Bohemia–Vogtland region. This work utilized high-performance computing resources made possible by funding from the Ministry of Science, Research and Culture of the State of Brandenburg (MWFK) and operated by the IT Services and Operations unit of the Helmholtz Centre Potsdam. The authors thank Simone Cesca for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript. The authors are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and to Wolfram Geissler for their constructive comments, which greatly helped us improve the manuscript, and to the editor for their valuable guidance. Open access funding provided by GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.B., T.D.; data curation: P.B., S.F., M.O., J.D.; formal analysis: P.B., S.F., S.W.; funding acquisition: P.B.; investigation: P.B., T.D., S.H., S.W.; methodology: P.B., T.D.; project administration: P.B.; resources: P.B., T.D., M.I., M.O., J.D., S.F.; software: P.B., M.I.; validation: P.B., T.D., S.H.; visualization: P.B., T.D., S.H.; writing—original draft: P.B., T.D.; writing—review and editing: P.B., T.D., S.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Wolfram Geissler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Büyükakpınar, P., Dahm, T., Hainzl, S. et al. Modelling of earthquake swarms suggests magmatic fluids in the upper crust beneath the Eger Rift. Commun Earth Environ 7, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03019-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03019-0