Abstract

The origin of intraplate basalts remains controversial, despite numerous isotope and seismic studies. Here we employ thermodynamic modeling with MAGEMin to integrate the Sr-Nd-Hf isotopes of basaltic volcanics with the seismic velocities of their mantle source. The results indicate that residual garnets generate high P-wave velocity anomalies in the mantle, and impart distinctive time-integrated εNd-εHf isotope signatures to the partial melts (i.e., the erupted basaltic magmas). Since the garnet-spinel transition (~42-60 km) is always shallower than the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (~70-100 km), garnet effects may serve as an indicator of thermal magmatic events. These findings suggest that the widely distributed Cenozoic intraplate basalts in Eastern China originated from the lithospheric mantle (<~60 km) that didn’t retain garnet. Two notable exceptions are the Wudalianchi and Nuominhe basalts, which originate from the asthenosphere (~100-140 km) and the lithosphere-asthenosphere transition, respectively. The integrated radiogenic isotope-seismic velocity framework can be applied to intraplate basalts globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The plate tectonics paradigm cannot readily explain the widespread occurrence of intraplate basaltic volcanism1. Therefore, understanding the mantle sources of intraplate basalts is essential for elucidating mantle evolution and Earth’s deep dynamics2,3. At present, both radiogenic isotope systems (e.g., Sr-Nd-Hf) and seismic velocity measurements (P- and S-wave velocity; Vp and Vs) are widely employed to investigate mantle processes associated with basaltic magmatism4,5. However, inconsistencies often arise between these two approaches (e.g., due to their different sensitivities to mantle properties), as exemplified by studies of Cenozoic basalts in Eastern China6,7.

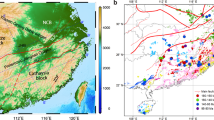

Cenozoic Eastern China represents a typical continental intraplate setting, comprising numerous relatively small but widely distributed volcanic fields that extend over 4000 km from Northeast to Southeast China (Fig. 1). Despite extensive investigations using radiogenic isotopes and seismic velocity data, the origin of these basalts remains debated8,9,10. Existing geodynamic models proposed to explain magma generation include:

-

I.

the Big Mantle Wedge (BMW) above the stagnant Pacific slab5,11,12,13, supported by seismic tomography (stagnant slab in the mantle transition zone with upwellings), OIB-like geochemistry, and slab-fluid signals, mainly applicable to Northeast China;

-

II.

a deep-seated, lower-mantle rooted mantle plume14,15, supported by a vertical low-velocity column extending to >700 km, and OIB-like EM2 isotopic features, with applicability in Southeast China (Leiqiong region, South China Sea, and eastern Thailand);

-

III.

lithospheric thinning and destruction16,17,18, supported by fertile, hydrous mantle xenoliths, recycled oceanic crust pyroxenite endmembers, and thin lithosphere imaged by seismic velocity, with applicability in eastern North China Craton, Mongolia, and eastern Russia;

-

IV.

edge-driven or small-scale convection19, supported by small-volume OIB-like basalts without plume involvement, with applicability in the margins of the North China Craton and coastal areas;

-

V.

Pacific slab rollback and tearing-induced extension20, supported by seismic evidence of slab tearing and segmentation, mainly in Northeast China;

-

VI.

recycled oceanic crust in the source21,22,23, supported by Sr-Nd-Pb-Os isotope ratios indicative of slab contributions, recycled oceanic crust endmember, and pyroxenite xenoliths, with applicability across northeast China, the North China Craton, and Southeast China;

-

VII.

plume-slab interaction models24, supported by OIB and slab-fluid geochemical traits, with applicability in Northeast China and the Leiqiong region.

Part 1 (Thermodynamic modeling) establishes a direct link between Part 2 (Sr-Nd-Hf isotopes) and Part 3 (Seismic velocity) through phase proportions and trace element partitioning during partial melting of mantle rocks. The isotopic maps and seismic tomographic profiles are compiled from previous studies7,70. The topographic map are after Google Earth.

Even within the same tectonic units of Eastern China, multiple geodynamic models can be invoked depending on the chosen lines of evidence. Reconciling these approaches is challenging for several reasons. Notably, interpretations of radiogenic isotopes are limited by uncertainties in trace element behavior during partial melting, even when bulk isotopic ratios appear similar. Furthermore, residual refractory minerals (e.g., garnet and olivine) left after melt extraction can generate positive seismic velocity anomalies25. Similarly, seismic velocity interpretations also face complexities of their own. This underscores the potential of geophysical techniques, particularly seismic tomography, to constrain the mantle sources of the Cenozoic basaltic volcanism. Nevertheless, in the absence of explicit constraints on mineral assemblages, phase properties, and thermal states in the upper mantle, seismic tomography alone provides limited resolution. Thus, integrating knowledge of trace element behavior during melting with the seismic velocities of residual assemblages is necessary to establish a direct genetic connection between radiogenic isotopes and seismic tomography. However, specific methodologies for linking geochemical and geophysical signals remain unresolved.

This study represents the attempt to integrate seismic and isotopic data using thermodynamic modeling, recognizing that mineral assemblages are the key factor for both isotopic compositions and seismic velocities. We employ thermodynamic modeling to simulate progressive partial melting of peridotites and pyroxenites, based on mantle xenolith from Eastern China, under the assumption of rapid and complete trace element and isotope exchange between melt and residues26,27. Because the temperature of partial melting exceeds mineral closure temperatures, diffusive exchange rates of elements and isotopes are sufficiently high that equilibration is achieved within days26,27. The resulting partial melts, characterized by distinct Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf ratios, further evolve after segregation. Previous studies indicate that the Cenozoic basalts experienced no isotope fractionation after melt segregation; thus, the radiogenic isotopic compositions of the partial melts should match those of the erupted basalts. Meanwhile, the residual mantle, having undergone melt extraction, is assumed to have experienced minimal thermal or tectonic disturbance across most regions, due to relatively stable Cenozoic tectonic conditions. This stability is evidenced by the absence of present-day mantle upwelling, substantial heat anomalies, and the predominance of intraplate shallow earthquake28, as well as by low horizontal crustal strain rates29. Consequently, the residual mantle is expected to preserve its seismic velocity characteristics. These assumptions are applied to Cenozoic volcanic regions in Eastern China for modeling, and the results provide insights into regional mantle structures, particularly facies boundaries, thereby advancing understanding of how deep mantle processes influence surface magmatism.

Results and discussion

Melting scenarios and phase variations

Within the modeled pressure-temperature (P-T; see Method) space, the peridotite solidus ranges from ~1200 to 1690 °C between 10 and 50 kbar (P and T increase together). With increasing temperature, partial melting of garnet- (Grt) and spinel- (Spl) facies peridotite above the solidus proceeds to progressively higher melt fractions. As melting advances, the residual lithologies evolve from wehrlite and/or lherzolite, to harzburgite and dunite. Residues comprise mineral assemblages of olivine (Ol) ± orthopyroxene (Opx) ± clinopyroxene (Cpx) ± Grt ± Spl, with two Spl compositional types, i.e., Al- and Cr-rich Spl (Fig. 2 and S1). Grt and Al-rich Spl are the principal indicator minerals that distinguish peridotite facies; their stability is primarily pressure-controlled via a peritectic reaction following a curve from ~17 kbar/1200 °C to ~21 kbar/1350 °C. Within a narrow interval along this curve, Grt and Al-rich Spl may coexist. Grt is less readily consumed at higher pressure. Specifically, Grt is exhausted at ~2.2–38.6 mol.% melting at 21–50 kbar, whereas Al-rich Spl is consumed at ~3.9–2.1 mol.% melting at 10–20 kbar. In contrast, Cr-rich Spl occurs only within a limited P-T region (~10 kbar/1500–1590 °C to ~14 kbar/1610 °C) defined by the univariant reaction. Modeled residues contain only minor Spl overall, with maximum molar proportions of 1.1 (Al-rich) and 0.2 mol.% (Cr-rich).

Ol is the dominant residual phase under all modeled conditions from 10 to 50 kbar, increasing from ~60.6 to 100.0 mol.% with progressive melting. Cpx and Grt reach maxima of 31.1 and 14.1 mol.%, respectively, but are fully consumed along their phase-boundary curves (~10 kbar/1340 °C to ~50 kbar/1710 °C for Cpx; ~21 kbar/1400 °C to ~50 kbar/1800 °C for Grt). Eutectic melting of Cpx and Grt increase Opx contents in the residue to as much as ~33.2 mol.% (normalized to 100), reflecting the role of Opx as a principal peritectic phase. This melting progression drives the assemblages from the wehrlite-lherzolite series to the harzburgite-dunite series, marking a transition from fertile to depleted mantle. Opx is completely dissolved along the phase boundary from ~10 kbar/1530 °C to ~30 kbar/1800 °C.

The pyroxenite solidus is substantially lower than that of peridotite, ranging from 1200 to 1580 °C at 11–50 kbar (Figs. 2 and S2). Progressive melting between 10 and 15 kbar drives the residue from clinopyroxenite through olivine websterite (lherzolite), to harzburgite and dunite with increasing melt fraction. At higher pressures (16–50 kbar), the residue evolves from clinopyroxenite to websterite and may progress to eclogite and/or orthopyroxenite. Although residual mineral assemblages resemble those of the peridotite system, pyroxenite contains only Al-rich Spl; Cr-rich Spl is absent. The Al-rich Spl to Grt transition occurs at lower pressure than in peridotite, following a boundary from ~14 kbar/1200 °C to ~38 kbar/1500 °C. Grt exhibits a broader stability field in the pyroxenite regime, extending from ~14 kbar/1200 °C to ~47 kbar/1790 °C, and becomes the liquidus phase at 31–50 kbar. Opx is stable along the liquidus between 16 and 30 kbar and forms through the peritectic melting of Grt and Cpx. Unlike peridotite melting, enrichment of Ol in the residue occurs only at lower pressures (10–15 kbar), while Cpx can constitute up to ~95.5 mol.% of the residue (normalized to 100). The phase-boundary curves for Ol and Cpx extend from ~10 kbar/1310 °C to ~50 kbar/1760 °C and from ~10 kbar/1470 °C to ~50 kbar/1630 °C, respectively.

Variations in melt composition and the influence of mineralogy

Modeled partial melts of peridotite and pyroxenite across a range of melt fractions are predominantly komatiitic-picritic-basaltic, with broad compositional ranges in SiO2 (42.4–52.9 wt%), MgO (5.9–34.8 wt%), FeO (4.0–17.8 wt%), Al2O3 (4.7–20.9 wt%), and CaO (4.1–14.1 wt%). These variations are governed chiefly by eutectic and peritectic reactions among multiple minerals (Figs. S3–S5).

Ol is Mg-rich, with high forsterite (Fo) contents of 89.6–95.9 in the peridotite system and 80.6–93.5 in the pyroxenite system (Fig. S6). The forsterite component increases with melt fraction (i.e., temperature). Ol also has the lowest SiO2 (39.3–41.9 wt%) of the modeled minerals, and its FeO spans 4.2–18.2 wt% with a negative correlation to temperature. Opx is strongly pressure dependent and Mg-rich, with enstatite (En) contents of En84.5-94.6 in peridotite and En80.2-91.1 in pyroxenite (Figs. S7–S8). Its FeO(T) and Al2O3 contents range from 3.0–9.9 and 1.8–9.5 wt%, respectively, and CaO reaches up to 3.5 wt%. In contrast, Cpx shows a wider En range (Figs. S9–S10): En53.4-78.6 in peridotite and En42.5-78.8 in pyroxenite (10–50 kbar), controlled mainly by temperature. Cpx contains 4.0-10.5 wt% Al2O3 and 0.3-4.2 wt% Na2O, both decreasing with increasing temperature. Grt is dominated by a pyrope component (73.9-78.8%) and differs systematically between peridotite and pyroxenite (Figs. S11–S12). Cr2O3 is 1.4–6.0 wt% (peridotite) versus 0.1-0.6 wt% (pyroxenite); FeO, 4.6–6.8 wt% versus 4.5–11.0 wt%; MgO, 21.0-24.8 wt% versus 15.4–23.8 wt%; CaO, 2.4–6.3 wt% versus 4.2–11.2 wt%; and Al2O3, 19.1–22.4 wt% versus 22.0–23.4 wt%. These differences reflect bulk-composition contrasts (e.g., Cr) between systems, as well as temperature, pressure (affecting Fe, Mg, Cr), and peritectic melting of pyroxenes (affecting Ca, Al). In peridotite, Al-rich Spl contains higher Cr2O3 (4.6–8.3 wt%) but lower FeO (7.7–8.4 wt%), Al2O3 (60.5–64.3 wt%), and MgO (22.5–23.1 wt%) than its pyroxenite counterpart. Cr-rich Spl in peridotite contains even higher Cr2O3 (64.1–67.8 wt%) and FeO (11.8–13.2 wt%) but lower Al2O3 (5.2–8.1 wt%) than Al-rich Spl.

In peridotite (Fig. S4), although Al-rich Spl contains more Al2O3 than Grt, its much lower modeled abundance causes that, by mass balance, melt Al2O3 decrease with increasing pressure as the system transitions from Spl- to Grt-facies peridotite. CaO is buffered by both Cpx and Grt. In the Spl-facies peridotite, CaO is initially released during Cpx melting and then decreases as Ca-poor phases dissovle, peaking at ~18–20 mol.% melting. In Grt-facies peridotite, broader melting intervals for Grt and Cpx buffer CaO, producing a smoother decline. At high melt fractions (>40%), melt CaO converges across pressures because only Ol and Opx remain in the residue, and no Ca-rich phase is left. MgO increases in melt fraction due to enhanced Ol dissolution. Spl-facies peridotites exhibit greater MgO variability than Grt-facies equivalents because Grt buffers melt composition. Among minerals, FeO varies most in Ol (4.2–10.1 wt%), followed by Cpx (3.4–5.0 wt%), Opx (3.0–6.2 wt%), and Grt (4.6–8.2 wt%). Consequently, melt FeO reflects both eutectic melting and changes in residual Ol composition, particularly its lower FeO at high temperature.

In pyroxenite (Fig. S5), melt FeO varies with melt fraction similarly to the peridotite. At lower pressure (<~31 kbar), melt Al2O3 remains relatively constant because peritectic melting of pyroxenes releases comparable amounts of Al2O3 through the melting interval. At higher pressure (>~31 kbar), Al2O3 increases with melt fraction as Opx disappears and Cpx and Grt continue to melt. Differences in CaO trends between peridotite and pyroxenite reflect the greater abundance of Grt in pyroxenite, which shifts the CaO maximum to higher melt fractions. Variations in melt MgO are controlled by the high proportion of Ol melting at relatively low degrees of partial melting (~10–15 mol.%) under high-pressure conditions (42–50 kbar).

The bulk compositions of most modeled melts fall within the range of Cenozoic basaltic volcanics from Eastern China (Fig. S13), indicating that the models are suitable for reconstructing the mantle melting processes that produced these rocks.

Mineral effects on Sr-Nd-Hf isotopes

In the modeled system, Grt, Cpx, and Opx primarily control melt Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf because they host comparatively high concentrations of the relevant elements and exhibit different partitioning behavior. Mineral-melt partition coefficients (D) were calculated for Rb, Sr, Sm, Nd, Lu, and Hf in Grt, Cpx, and Opx using a new dataset that incorporates recent experimental results and is well constrained for our modeling conditions (Figs. S14–S15).

During melting of Grt-facies fertile mantle (lherzolite to wehrlite; Fig. S14), residual Cpx and Grt dominate melt Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf; Opx has a negligible effect on these ratios compared with Grt and Cpx. Because Grt has much higher DLu and DHf than Cpx (Grt DLu/DHf = 6.0–3.6), residual Grt lowers melt Lu/Hf (Fig. S14). Although DSm and DNd are comparable in Grt and Cpx, DSm/DNd is slightly higher in Grt (3.0–5.7) than in Cpx (1.2–3.2), so residual Grt produces greater Sm/Nd fractionation, whereas residual Cpx exerts a moderate effect. Cpx has much higher DRb and DSr than Grt and thus primarily controls melt Rb/Sr. Specifically, lnDRb in Cpx varies from −3.6 to 1.6 with increasing pressure, reaching DRb ≈ 1 at ~22 kbar; lnDSr in Cpx varies less (lnDSr ≈ −1.6 ± 0.2). Consequently, DRb/DSr in Cpx spans 0.1–19.0, yielding melt Rb/Sr variability that depends on whether Cpx remains in the residue at a given pressure. In Spl-facies peridotite, residual Cpx is the dominant control. Thus, contrasting residual assemblages (Grt vs. no-Grt) drive distinct melt-evolution trends. Opx has substantially lower D values than Cpx and Grt and becomes influential only when Cpx and Grt are nearly exhausted—e.g., during the melting of depleted harzburgite-dunite. Residual Opx lowers Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf because its DLu/DHf, DSm/DNd, and DRb/DSr are all >1.

The effects of Grt, Cpx, and Opx broadly resemble those in peridotite (Fig. S15), but mineral-chemistry differences yield greater variability in Grt DLu/DHf, DSm/DNd, and DRb/DSr. As a result, Grt exerts a stronger influence on melt Sm/Nd and Lu/Hf, and at >31 kbar it can be the liquidus mineral. Cpx also affects melt ratios when residual, whereas Opx is fully consumed above 31 kbar. Between 14 and 31 kbar, melt ratios reflect combined controls by Cpx, Opx, and Grt. Melt Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf resemble those in certain peridotite scenarios with similar Cpx-Grt-Opx sequences. Below 14 kbar, pyroxenite melting resembles Spl-facies peridotite, with residual Cpx dominant and Opx negligible. Overall, both lithologies can display melt-evolution trends characterized by the presence or absence of Grt.

The time-integrated evolution of radiogenic Sr-Nd-Hf isotope compositions is governed primarily by melt Rb/Sr, Sm/Nd, and Lu/Hf30. Over time, radioactive decay increases the absolute values of ∆Sr, εNd, and εHf, generating distinctive ∆Sr-εNd-εHf trajectories (Fig. 3). Grt minimally affects ΔSr, producing overlapping ΔSr trends in Grt and no-Grt systems. By contrast, Grt strongly influences Sm-Nd and Lu-Hf isotopic systems, with Lu-Hf more sensitive to residual Grt, whereas Sm-Nd is also affected by residual Cpx. In the absence of Grt, residual Cpx dominates Nd-Hf isotopes. Together, these controls yield distinct εNd-εHf trends during the melting of Spl- and Grt-facies peridotites and pyroxenites.

As with trace-element partitioning, Cpx primarily controls Rb-Sr isotopic system, producing large ∆Sr variations when retained in the residue (peridotite: −3.4 × 10−4 to 5.2 × 10−4; pyroxenite: −2.8 × 10−4 to 74.2 × 10−4). ∆Sr is therefore most sensitive to residual Cpx and relatively insensitive to Spl/Grt facies. Residual Opx plays a minor role compared with Cpx and Grt, but slightly lowers ∆Sr, εNd, and εHf in melts derived from depleted mantle (e.g., when Opx becomes the liquidus phase). In peridotite, εNd-εHf trends diverge at low melt fraction and converge beyond ~30–35 mol.% (Grt-facies) and ~20–25 mol.% (Spl-facies). In pyroxenite, εNd-εHf trends overlap those for both Grt-bearing and Grt-free peridotite. Hence, combining εNd and εHf in natural basalts can constrain the presence of residual Grt and the degree of melting (Fig. 4).

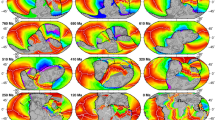

a, d Vp and Vs of minerals and residual mineral assemblages as a function of pressure; b, e Vp/Vs of minerals and residual mineral assemblages as a function of temperature and pressure; c, f Vp/Vs of residual mineral assemblages as a function of melt fraction (mol.%) and pressure; g–h covariation of εNd, εHf and Vp for garnet-bearing and garnet-free residues after melt segregation; i Vp/Vs-εHf projections for peridotite and pyroxenite arrays.

Seismic velocity of residual assemblages

Phase proportions of the residual assemblage (normalized to 100 mol.% after melt segregation), together with modeled thermodynamic conditions, allow estimation of compressional velocity (Vp), shear velocity (Vs), and Vp/Vs using approximate endmember mineral compositions (Fig. 4). For both individual minerals and bulk residues, velocities increase with pressure and decrease with temperature. Bulk Vp/Vs rises with pressure and melt fraction due to evolving mineral proportions. Grt has the highest velocities and Vp/Vs; thus, higher residual Grt yields higher bulk velocities and Vp/Vs. Cpx and Ol have velocities comparable to the bulk residue, whereas Opx has notably lower velocities and ratios. These relationships are consistent with previous tectonophysical studies31, which attribute anomalously low seismic signals in mantle wedges to metasomatism. During progressive melting, the consumption of Grt and Cpx drives a transition from fertile (lherzolite/wehrlite) to depleted (harzburgite/dunite) assemblages, leaving Opx-dominated residues and decreasing both Vp and Vs. Conversely, eclogite-like residues dominated by Grt and Cpx yield anomalously high seismic velocities and Vp/Vs. In nature, elevated regional temperature (e.g., post-thermal events) or incomplete melt segregation (melt retention) cause decreases both velocities and Vp/Vs. Accordingly, positive seismic anomalies are most consistent with residual Grt, implying that the mantle source has experienced substantial melt extraction.

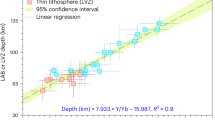

Source estimation based on seismic velocity and Nd-Hf isotopes

Our modeling results demonstrate that the εNd-εHf isotopic system differs in Spl- and Grt-facies mantle sources, with a transitional boundary at ~42–60 km depth corresponding to the pressure at which Grt becomes stable above the solidus. Variations in εNd and εHf provide insights into mantle fertility versus depletion, degrees of partial melting, and melting pressures. Seismic velocity data reveal large-scale mantle structures and effectively highlight compositional heterogeneities. Integrating isotopic data with seismic velocity thus offers a robust means of linking surface basalts to their mantle source regions. When εNd-εHf values are matched with modeled Vp, the boundary between Grt-bearing and Grt-free arrays becomes evident and shows greater sensitivity than ∆Sr-εNd-εHf systems, because εNd-εHf offers a clearer distinction whereas ∆Sr is less diagnostic. The presence of residual Grt after partial melting produces magmas that plot along the Grt-bearing trend in εNd-εHf space and originate from high-Vp mantle regions. This correlation can be applied in reverse to infer magmatic origins; however, caution is still required due to influences such as geothermal gradients, tectonic histories, and mantle rheology. Moreover, pressure estimates from isotopes should align with the depths of seismic anomalies, and estimated melting degrees must remain within natural ranges. Some magmas with Grt-facies isotopic signatures may not erupt at the surface but instead crystallize as plutonic bodies within the crust (86-93 vol.% in various tectonic settings)1, or re-equilibrate completely with Spl-facies mantle prior to ascent.

The modeling of Grt arrays, high-velocity anomalies, and Grt-facies mantle sources is corroborated by natural Grt-bearing mantle xenoliths. In the Colorado Plateau, such xenoliths occur in mafic magmas and derive from depths of 120–140 km32,33. Seismic data reveal high-velocity mantle zones at 80–200 km depth, previously interpreted as delaminated lithospheric mantle34,35. Comparing εNd-εHf compositions of regional mafic rocks with modeling trends shows transitions from no-Grt to Grt arrays (Fig. S16), suggesting magma derivation from the asthenosphere or the base of the lithosphere, and indicating thermal events spanning a broad depth range. These findings support a model of hot asthenospheric upwelling interacting with the lithosphere during extensional tectonics, as documented in the Colorado Plateau35.

Seismic anomaly regions and potential magma sources

Ultramafic xenoliths, including Spl/Grt-facies peridotites and pyroxenites, are commonly found in Cenozoic basalts across Eastern China36. Grt-facies peridotite xenoliths are typically associated with fault-controlled volcanic activity, such as along the Tan-Lu fault, the southeastern coastal gravity zone, and the north-south gravity lineament (GGL)37. These xenoliths are Grt-facies lherzolites and harzburgites, with or without rare spinel, with components of 50-74 vol.% Ol, 9.5-37 vol.% Opx, 3–22 vol.% Cpx, 0.5–16.8 vol.% Grt, and 0–3.2 vol.% Spl (see supporting information for reference). Phlogopite and amphibole are rare. Spl-facies peridotite xenoliths, including lherzolite, harzburgite, and dunite, are more widely distributed. Two types of Spl are recognized: Al-rich Spl, present in both Grt- and Spl-facies lherzolites, and Cr-rich Spl, restricted to Spl harzburgites and dunites. Pyroxenite xenoliths are primarily Spl/Grt-facies clinopyroxenites and websterites hosted in basalts of Southeast China (e.g., Leiqiong, Qilin), North China Craton (e.g., Hannuoba, Yangyuan), and Northeast China (e.g., Jiaohe, Kuandian). The mineral assemblages, proportions, and compositions of peridotite and pyroxenite xenoliths are consistent with modeling results, confirming the suitability of this study for investigating mantle systems in Eastern China.

The xenoliths used in this study are all Grt-facies peridotites from five Cenozoic basalt localities. From north to south, these include Chaoerhe, Shanwang, Nüshan, Xinchang, and Mingxi. Pressure estimates derived from the Cpx-only barometer38, based on mineral compositions within the xenolith, are consistent with results obtained from the two-pyroxene barometer37,39. As mantle xenoliths can be entrained from conduit zones during magma ascent, the inferred pressures therefore constrain the minimum depth of the host magmas’ mantle sources, which are shallower than the zones of positive seismic-velocity anomalies if those anomalies delineate the source regions The calculated pressure conditions and corresponding depths for the different localities are as follows: Chaoerhe (17.7–28.0 kbar, ~53–84 km depth), Nüshan (20.2–31.3 kbar, ~60–94 km depth), Shanwang (24.2–30.5 kbar, ~72–92 km depth), Xinchang (21.0–33.6 kbar, ~63–101 km depth), and Mingxi (24.3–33.4 kbar, ~72–102 km depth). Geophysical data reveal positive Vp anomaly zones at greater depths: Chaoerhe (~100–140 km), Nüshan (~80–160 km), Shanwang (~80-120 km, and Xinchang and Mingxi (~80–140 km). These Vp anomaly zones generally extend deeper than the depths of Grt-bearing mantle xenoliths (Fig. 5), which are entrained by ascending magma. Seismic parameters for these xenoliths, calculated from P-T conditions and mineral proportions, all within the Grt stability field. Such Grt-facies xenoliths do not represent the mantle anomalies, as they have not undergone garnet enrichment through partial melting (i.e., below the solidus on the phase diagram; Fig. S17). Instead, magma sources that experienced partial melting and melt-residue segregation are likely responsible for the positive Vp anomalies.

Boxplots showing the depths of high-Vp regions in representative Cenozoic volcanic fields in Eastern China, compared with single-Cpx barometer pressure estimates for Grt-bearing xenoliths. Circle symbols outside the error bars represent outliers. Xenolith data sources are provided in the Supporting Information. Vp data are from previous seismic studies7.

Implications for the mantle source of Cenozoic basaltic volcanic regions in Eastern China and other intraplate settings

The scarcity of intraplate basaltic magmas containing Grt-facies peridotite xenoliths in Eastern China presents challenges for constraining the mantle sources of the widely distributed volcanic regions (Fig. 6). Consequently, isotopic techniques remain the most effective means of characterizing these sources. The three-dimensional thermal structure of East Asian continental lithosphere exhibits pronounced lateral heterogeneity, although high lithospheric temperatures are largely confined to the Mongolia Plateau, Northeast China, and southeast coast of China40. To enhance the applicability and simplify modeling, temperature effects are neglected to some extent. Accordingly, seismic-velocity anomalies are evaluated relative to regional tectonic units rather than fixed absolute thresholds, to reduce bias that could arise from underrepresenting lateral thermal variability across East and South Asia. Simpler spatial correlations between magma and mantle source regions then provide insights into magma derivation depths and perspectives on thermal events within the mantle system.

Seismic velocity and Vp/Vs profiles of representative volcanic regions in Eastern China, along with normalized εNd-εHf values of Cenozoic basalts compared with modeling arrays. The εNd and εHf values are normalized to 400 Ma according to TDM ages. Circles and solid lines on the profiles mark potential magma sources and the garnet-in depth. Tomographic data are from previous seismic studies7. Abbreviation: Yuyao-Lishui, Zhenghe-Dapu and Lianhuashan (YLZDL) fault, Gravity gradient lineament (GGL). Isotopic data sources are provided in the Supporting Information.

A key boundary within the mantle is the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (LAB), which in Eastern China lies at depths of 70–80 km beneath the eastern North China Craton and South China coast, and 90–100 km beneath the western North China Craton and inland South China37. This depth exceeds the Spl-Grt transition boundary (peridotite ~60 km; pyroxenite ~42 km), allowing Grt to serve as a marker distinguishing lithospheric from asthenospheric mantle signatures. Although overlaps exist between no-Grt and Grt trends, achieving melting degrees of >30–35 mol.% is difficult. Typical mantle melting degrees are ~20–25% for tholeiitic basalts and basanites, and ~25–30% for picrites and komatiites41. Thus, if the isotope data align with overlapping trends, the no-Grt array likely represents their sources. Basaltic samples plotting on the no-Grt array in εNd-εHf space are therefore inferred to originate from melting, or to have undergone complete re-equilibration, in lithospheric mantle source at depths shallower than ~60 km. By contrast, samples plotting on the Grt array require integration with seismic velocities to discriminate between lithospheric basal or asthenospheric origins. In seismic velocity profiles, decreases in Vs from the lithosphere to the asthenosphere must be considered, as they may reflect increased strain rates, the downward extinction of seismic anisotropies, or changes in anisotropy direction42,43. Moreover, Vp is less sensitive to melts than Vs44. As a result, higher Vp/Vs ratios, together with positive Vp anomalies caused by residual Grt, are expected if magma is derived from the asthenosphere.

To test these constraints, Nd-Hf isotopic data, modeling results, and seismic velocity profiles were applied to widespread Cenozoic mafic volcanic regions in Eastern China and surroundings. A total of 583 paired bulk-rock Nd-Hf isotope data from 28 representative volcanic regions were compiled. The εNd-εHf patterns of these magmas, normalized to tDM = 400 Ma (tDM, depleted mantle model ages), were compared with modeling arrays. Results indicate that most Cenozoic mafic volcanic regions in Eastern China and surroundings plot on the no-Grt array. Two exceptions occur in Northeast China: (i) Wudalianchi basalts display distinct Nd-Hf isotopic signatures consistent with the Grt array; and (ii) Nuominhe basalts plot in the transition between no-Grt and Grt arrays.

Several mantle source models have been proposed for the Wudalianchi volcanic field, including subducted slab components in the mantle transition zone, inferred from light Ba isotopes, low δ26Mg, and decoupled Nd-Hf isotopic signatures45,46; an upwelling hydrous mantle plume, inferred from Sr-Nd-Pb isotope47; decompression melting of metasomatized subcontinental lithospheric mantle, supported by Sr-Nd-Pb, Lu-Hf, and Re-Os isotopes48,49; interaction between metasomatized lithospheric mantle and carbonated asthenospheric mantle, indicated by low bulk δ26Mg values50; upwelling of hot, hydrous asthenospheric material above the stagnant Pacific slab51,52, inferred from low Vp anomalies at lithospheric mantle depths; shear-driven local asthenospheric upwelling at the lithosphere base, similarly inferred from low Vp anomaly53.

By integrating modeling with previous studies, the following implications emerge: Wudalianchi basalts exhibit EM1-like Sr-Pb-Nd isotopic characteristics (high 87Sr/86Sr and 207Pb/206Pb ratios, and low 143Nd/144Nd ratios)47, coupled with low δ26Mg and high δ57Fe values, which differ markedly from other Cenozoic mafic volcanism in Eastern China6,50,54,55. The high bulk alkali contents suggest derivation from a peridotite mantle source (given the low alkali contents of pyroxenite melts) and low degrees of melting. Seismic profiles beneath Wudalianchi reveal positive Vp anomalies at depths of 100–140 km and elevated Vp/Vs ratios, indicating an asthenospheric mantle source. The fertile mantle source is likely Grt-facies wehrlite or lherzolite, which underwent and preserved deep-mantle signals, with minimal overprinting by shallow lithospheric mantle processes.

The Nuominhe volcanic field, located ~200 km west of Wudalianchi, suggests a mixed source or incomplete re-equilibration process based on Nd-Hf isotopes. Seismically, Nuominhe may share the same source as Wudalianchi, as both are underlain by continuous regions of positive Vp anomalies. However, partial overlap of high Vp/Vs ratios with positive Vp anomalies suggests a magma source linked to the LAB. This interpretation is consistent with isotopic evidence, including lower 87Sr/86Sr and δ57Fe values, but higher 207Pb/206Pb ratios, relative to Wudalianchi55.

The Wudalianchi and Nuominhe fields lie in a transitional zone between Eastern and Northeastern Asia. Compression of the subducted Pacific slab, due to changes in its subduction angle, may fragment the weak slab. As the slab retains water at depth56, fractures may facilitate its release, triggering partial melting of the overlying asthenosphere and generating hydrous magmas. Consistent with this tectonic setting, pre-erupted Wudalianchi magmas emplaced at depths of 37–47 km contain ~4.5 wt% H2O comparable to arc magmas57. The intersection of multiple structural trends forms a tectonic syntaxis, characterized by distinctive geophysical signatures, commonly observed in continental intraplate settings58.

All other Nd-Hf isotopic data from Cenozoic volcanic regions in Eastern China plot on the no-Grt array. Mantle melting degrees vary substantially, covering the ranges typical of basalts and basanites. These results suggest that: (i) the upper lithospheric mantle is the source of most magmas, and (ii) deeper-derived magmas likely underwent complete re-equilibration with the lithospheric mantle during ascent. These implications do not contradict geodynamic models inferred from geophysical evidence (e.g., plume-shaped seismic anomalies in the deep mantle or metasomatized regions above the subducted slab). However, they suggest that such deep-mantle anomalies may not be directly linked to Cenozoic volcanism. Instead, widespread continental intraplate basalts may reflect shallow mantle responses to deep geodynamic processes or represent the continued evolution of earlier magmatism in which deep-sourced melts erupted before the Cenozoic.

For comparison, Nd-Hf isotopic data from basaltic rocks in global intracontinental settings and Large Igneous Provinces (LIP) are compiled. Normalized results (Fig. S18) show that a large fraction of continental intraplate and rift-related basalts falls within no-Grt arrays. In contrast, LIP basalts, typically derived from deeper mantle sources, exhibit Nd-Hf isotopic values ranging from Grt to no-Grt arrays (e.g., Karoo), reflecting variable melting depths and extensive thermal anomalies. Similarly, Mesozoic basalts from the North China Craton, which plot within the Grt array and preserve deep-mantle isotopic signals, are linked to lithospheric delamination and deep-seated magmatism16,18. Transitional Nd-Hf isotopic compositions—spanning Grt to no-Grt arrays—are also recorded along both the eastern and western margins of the Tibetan Plateau. Positive seismic velocity anomalies in the deep lithosphere-asthenosphere system are observed in volcanic regions of the North China Craton and along Tibetan Plateau margins58, which also represent classic examples of tectonic synaxis in Eastern Asia58. Collectively, these results indicate that shallow lithospheric mantle processes dominate the formation of intracontinental basalts, whereas tectonic syntaxial zones and large-scale thermal events are key to generating deeper, asthenosphere-derived magmas.

Method

Modeling approach

Mineral and melt proportions during partial melting were simulated using MAGEMin59, incorporating updated thermodynamic models for magmatic systems (Supplementary Data 1)60. Simulations were conducted at 10 °C intervals over a temperature range of 1200–1800 °C, using KLB-1 (peridotite) and MIX1-G (pyroxenite) as the starting composition61,62. Pressure was varied from 10 to 50 kbar in 1 kbar increments. The redox state was set to CCO conditions (∆FMQ = −1.9 to −3.0), representative of mantle environments63,64.

Recalibration of partitioning coefficients

Previous experimental studies demonstrate that partition coefficients (D values) are sensitive to pressure, temperature, and composition65,66. Accordingly, the D values for Rb, Sr, Sm, Nd, Lu, and Hf were recalibrated using an empirical equation based on the experimental datasets (Fig. S19). A new thematic database hosted on the OnePetrology platform provides accessible data resources (https://petrology.deep-time.org/subject/detail.html?id=74; off-line version, Supplementary Data 2). Recalibration performance was evaluated through linear regression, yielding R2 values between 0.8 and 1.0.

For garnet (X3Y2Z3O12), the key variables XAl, XCa, and XFM (where XFM = XFe + XMg) were used to determine D values, calculated according to the equation:

Constants A through A6 are listed in Table S1.

For pyroxene [(M2)(M1)(Si,Al)2O6], D values were recalculated using the enstatite component (XEn) and XAl. The corresponding equation is:

Constants A through A5 for clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene are provided in Tables S2 and S3. NBO/T refers to the ratio of non-bridging oxygens to tetrahedral cations.

Trace element partition and radiogenic isotope modeling

The partition coefficients (\({{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Mineral}}}}}\)) were applied to model the dissolution of eutectic minerals and the crystallization of peritectic phases, allowing the calculation of trace element concentrations in all phases. Primitive mantle compositions67 served as the protolith for these calculations. Mass balance was applied as follows:

where \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{{{\rm{Melt}}}}}\) is the concentration of element i in the melt, \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Source}}}}}\) is its concentration in the source, \({{{{\rm{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Melt}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{Mineral}}}}}\) are the melt and mineral fractions.

Using these concentrations, the initial parent/daughter isotope ratios (87Rb/86Sr, 147Sm/144Nd, and 176Lu/177Hf) were computed. The initial ratios (86Sr/87Sr, 143Nd/144Nd, and 176Hf/177Hf), along with decay constants for 87Rb, 147Sm, and 176Lu, follow published values68. All isotopic data were normalized to CURE standards69. Isotopic evolution of melts derived from different protoliths was modeled using:

Here, R represents the isotope ratio, \({{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}^{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) are the initial and final values, respectively, λ is the decay constant, and t is time (e.g., 400 Ma). The resulting Nd-Hf isotopic differences after decay are expressed as:

For Sr isotopes, the corresponding equation is:

The formulations are consistent with standard practices in radiogenic isotope geochemistry.

Data availability

All data supporting this study are provided in the online supplementary files.

References

Perfit, M. R. & Davidson, J. P. Plate tectonics and volcanism. Encycloped. Volcan. 89–113 (2000).

Rudnick, R. L. et al. Petrology and geochemistry of spinel peridotite xenoliths from Hannuoba and Qixia, North China craton. Lithos. 7, 609–637 (2004).

Hoffmann, J. E. et al. The origin of decoupled Hf-Nd isotope compositions in Eoarchean rocks from southern West Greenland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 75, 6610–6628 (2011).

Niu, Y. L. Generation and evolution of basaltic magmas: some basic concepts and a new view on the origin of Mesozoic-Cenozoic basaltic volcanism in eastern China. Geol. J. China Univ. 11, 9–46 (2005).

Xu, Y. G. et al. Generation of Cenozoic intraplate basalts in the big mantle wedge under eastern Asia. Sci. China D. Earth Sci. 61, 869–886 (2018).

Zhou, Z. B. et al. The return of stagnant slab recorded by intraplate volcanism. PNAS. 122, e2414632122 (2024).

Ma, J. C. et al. Seismic full-waveform inversion of the crust-mantle structure beneath China and adjacent regions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2022JB024957 (2022).

Zhang, A. Q. et al. Lithosphere-asthenosphere interactions beneath northeast China and the origin of its intraplate volcanism. Geology 50, 210–215 (2022).

Zhang, H. J. et al. Seismically imaged lithospheric delamination and its controls on the Mesozoic magmatic province in South China. Nat. Commun. 14, 2718 (2023).

Dai, H. K., Xiong, Q. & Zheng, J. P. Mantle dynamics of the long-lived Middle Yangtze basaltic field: insight from a combined geochemical and numerical modeling approach. Geochem. Geophy. Geosy. 26, e2024GC012028 (2025).

Chen, C. X. et al. Mantle transition zone, stagnant slab and intraplate volcanism in Northeast Asia. Geophys. J. Int. 209, 68–85 (2017).

Tian, Y. et al. Mantle transition zone structure beneath the Changbai volcano: Insight into deep slab dehydration and hot upwelling near the 410 km discontinuity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 5794–5808 (2016).

Zhong, Y. et al. Involvement of slab-derived fluid in the generation of Cenozoic basalts in Northeast China inferred from machine learning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5234–5242 (2019).

Yan, Q. S. et al. Hainan mantle plume produced late Cenozoic basaltic rocks in Thailand. Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 8, 2640 (2018).

Wei, S. S. & Chen, Y. J. Seismic evidence of the Hainan mantle plume by receiver function analysis in southern China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8978–8985 (2016).

Sheldrick, T. C. et al. Simultaneous and extensive removal of the East Asian lithospheric root. Sci. Rep. 10, 4128 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Craton destruction 1: cratonic keel delamination along a weak midlithospheric discontinuity layer. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 10040–10068 (2018).

Liu, J. G. et al. Thinning and destruction of the lithospheric mantle root beneath the North China Craton: a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 196, 102873 (2019).

Sun, Y. J. & Liu, M. Edge-driven asthenospheric convection beneath the North China Craton: a numerical study. Tectonophysics 849, 229726 (2023).

Wu, L. L. et al. Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic intraplate extension and tectonic transitions in eastern China: Implications for intraplate geodynamic origin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 117, 104379 (2020).

Xu, Y. G. Recycled oceanic crust in the source of 90-40 Ma basalts in North and Northeast China: evidence, provenance and significance. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 143, 49–67 (2014).

Zeng, G. et al. Magma-magma interaction in the mantle beneath eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 2763–2779 (2017).

Guo, P. et al. Mantle and Recycled oceanic crustal components in mantle xenoliths from northeastern China and their mantle sources. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2019JB018232 (2020).

Chen, S. S. et al. Coexistence of Hainan Plume and Stagnant Slab in the Mantle Transition Zone beneath the South China Sea Spreading Ridge: constraints from Volcanic Glasses and Seismic Tomography. Lithosphere S2, 6619463 (2021).

Zhou, W. Y. et al. High P-T sound velocities of amphiboles: implications for low-velocity anomalies in metasomatized upper mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2023GL106583 (2024).

Smit, M. A., Scherer, E. E. & Mezger, K. Lu-Hf and Sm-Nd garnet geochronology: chronometric closure and implications for dating petrological processes. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 381, 222–233 (2013).

Knesel, K. M. & Davidson, J. P. Insights into collisional magmatism from isotopic fingerprints of melting reactions. Science 296, 2206–2208 (2002).

Liu, M. et al. 5 - Intraplate earthquakes in North China. Intraplate Earthquakes (ed. Talwani, P.) 97–125 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Hao, M., Li, Y. H. & Zhuang, W. Q. Crustal movement and strain distribution in East Asia revealed by GPS observations. Sci. Rep. 9, 16797 (2019).

Iles, K. A., Hergt, J. M. & Woodhead, J. D. Modelling isotopic responses to disequilibrium melting in granitic systems. J. Petrol. 59, 87–114 (2018).

Deng, X. et al. Seismic signals induced by the Metasomatism of mantle wedge by siliceous melts: insights from the elasticity of orthopyroxene at high pressure and temperature. Tectonophysics 846, 229681 (2023).

Riter, J. C. A. & Smith, D. Xenolith constraints on the thermal history of the mantle below the Colorado Plateau. Geology 24, 267–270 (1996).

Alibert, C. Peridotite xenoliths from western Grand Canyon and the Thumb: a probe into the subcontinental mantle of the Colorado Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 99, 21605–21620 (1994).

MacCarthy, J. K. et al. Seismic tomography of the Colorado Rocky Mountains upper mantle from CREST: Lithosphere–asthenosphere interactions and mantle support of topography. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 402, 107–119 (2014).

Sine, C. R. et al. Mantle structure beneath the western edge of the Colorado Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. 35, L10303 (2008).

Fan, Q. C. & Hooper, P. R. The mineral chemistry of ultramafic xenoliths of Eastern China: Implications for upper mantle composition and the paleogeotherms. J. Petrol. 30, 1117–1158 (1989).

Huang, X. L. & Xu, Y. G. Thermal state and structure of the lithosphere beneath Eastern China: A synthesis on basalt-borne xenoliths. JES 21, 711–730 (2010).

Putirka, K. D. Thermometers and barometers for volcanic systems. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 69, 61–120 (2008).

Huang, X. L., Xu, Y. G. & Liu, D. Y. Geochronology, petrology and geochemistry of the granulite xenoliths from Nüshan, East China: implication for a heterogeneous lower crust beneath the Sino-Korean Craton. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 68, 127–149 (2004).

Sun, Y. et al. Three-dimensional thermal structure of East Asian continental lithosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2021JB023432 (2022).

Foley, S. F. & Pintér, Z. Primary melt compositions in the Earth’s mantle. In Magmas under Pressure (eds Kono, Y. & Sanloup, C.) 3–42 (Elsevier, 2018).

Rychert, C. A. et al. The nature of the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2018JB016463 (2020).

Fischer, K. M. et al. The lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 38, 551–575 (2010).

He, E. Y. et al. Strong serpentinization and hydration in the subducting plate of the Southern Mariana Trench: insights from Vp/Vs ratios. J. Geophys. Lett. 52, e2024GL113792 (2025).

Wang, X. J. et al. Mantle transition zone-derived EM1 component beneath NE China: geochemical evidence from Cenozoic potassic basalts. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 465, 16–28 (2017).

Cheng, Y. S. et al. Barium isotope fingerprint for recycled ancient sediment in the source of EMI-type continental basalts. J. Geophys Lett. 52, e2024GL111960 (2025).

Kuritani, T. et al. Transition zone origin of potassic basalts from Wudalianchi volcano, northeast China. Lithos 156-159, 1–12 (2013).

Chu, Z. Y. et al. Source of highly potassic basalts in northeast China: Evidence from Re–Os, Sr–Nd–Hf isotopes and PGE geochemistry. Chem. Geol. 357, 52–66 (2013).

Meng, F. C. et al. Cenozoic potassic volcanic rocks from the Keluo and Wudalianchi volcanic districts, Northeast China: origin from the new sub-continental lithospheric mantle (SCLM) metasomatized by potassium-rich fluids from delaminated lower crust. Front. Earth Sci. 16, 989–1004 (2022).

Tian, H. C. et al. Origin of low δ26Mg basalts with EM-I component: evidence for interaction between enriched lithosphere and carbonated asthenosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 188, 93–105 (2016).

Wei, W. et al. Seismic evidence for a mantle transition zone origin of the Wudalianchi and Halaha volcanoes in Northeast China. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 3, 1–23 (2002).

Yu, W. Q. et al. Magma plumbing system and origin of the intraplate volcanoes in Mainland China: an overview of constraints from geophysical imaging. Geo. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 510, 197–214 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. New Insights into potassic intraplate volcanism in Northeast China from joint tomography of ambient noise and teleseismic surface waves. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB021856 (2021).

Zhao, Y. W. et al. Two episodes of volcanism in the Wudalianchi volcanic belt, NE China: Evidence for tectonic controls on volcanic activities. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 285, 170–179 (2014).

Shi, J. H. et al. Lithology of EMI reservoir revealed by Fe isotopes of continental potassic basalts. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 128, e2022JB025133 (2023).

Tsutsumi, Y. et al. Retention of water in subducted slabs under core–mantle boundary conditions. Nat. Geosci. 17, 697–704 (2024).

Di, Y. K. et al. A method to estimate the pre-eruptive water content of basalts: Application to the Wudalianchi–Erkeshan–Keluo volcanic field, Northeastern China. Am. Mineral. 105, 149–161 (2020).

Yang, W. C. et al. Crust-mantle structure of the typical tectonic syntaxis in East Asia. Geol. Rev. 70, 2051–2058 (2024).

Riel, N. et al. MAGEMin, an efficient Gibbs energy minimizer: Application to igneous systems. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 23, e2022GC010427 (2022).

Holland, T. J. B., Green, E. C. R. & Powell, R. Melting of peridotites through to granites: A simple thermodynamic model in the system KNCFMASHTOCr. J. Petrol. 59, 881–900 (2018).

Dasgupta, R. & Hirschmann, M. M. Melting in the Earth’s deep upper mantle caused by carbon dioxide. Nature 440, 659–662 (2006).

Hirschmann, M. M. et al. Alkalic magmas generated by partial melting of garnet pyroxenite. Geology 31, 481–484 (2003).

Ballhaus, C. Redox states of lithospheric and asthenospheric upper mantle. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 114, 331–348 (1993).

Birner, S. K., Cottrell, E. & Davis, F. A. Deep, hot, ancient melting recorded by ultralow oxygen fugacity in peridotites. Nature 631, 801–807 (2024).

Beattie, P. Uranium-thorium disequilibria and partitioning on melting of garnet peridotite. Nature 363, 63–65 (1993).

Salters, V. J. M., Longhi, J. E. & Bizimis, M. Near mantle solidus trace element partitioning at pressures up to 3.4 GPa. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 3, 1–23 (2002).

Sun, S. S. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geo. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 42, 313–345 (1989).

Söderlund, U. et al. The 176Lu decay constant determined by Lu-Hf and U-Pb isotope systematics of Precambrian mafic intrusions. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 219, 311–324 (2004).

Caro, G. & Bourrdon, B. Non-chondritic Sm/Nd ratio in the terrestrial planets: Consequences for the geochemical evolution of the mantle–crust system. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 3333–3349 (2010).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. Crustal architectural controls on critical metal ore systems in South China based on Hf isotopic mapping. Geology 58, 738–742 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Thomas Sheldrick and Prof. Amiya K Samal for their kind reviewing and constructive suggestions to the article. This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0708604-2), the National Natural Foundation of Science of China (42372058), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (265QZ201901), MSFGPMR201804 and B18048.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The modeling, calculation, and manuscript were completed by Z.Y. under the supervision of T.H., R.B., E.M., M.W., S.B., and Z.Z. The experimental petrological database was finished by Z.Y. Final reviewing and editing were performed by TH., R.B., S.B., and S.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Amiya K. Samal and Thomas C. Sheldrick for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Domenico M. Doronzo and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Hou, T., Botcharnikov, R. et al. Seismic and isotopic evidence for depth-dependent mantle sources of intraplate basalts from Eastern China. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1048 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03024-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03024-3