Abstract

Hydrocarbon seeps release fossil methane into the marine environment, but emission of this seep-derived methane to the atmosphere is challenging to constrain. Here, we measure the concentration and radiocarbon content of dissolved methane in seawater above seeps in the northern Gulf of Mexico that have previously been linked to considerable atmospheric emissions. In bottom waters above the seeps, methane radiocarbon content is close to zero, confirming the release of fossil seep methane. However, radiocarbon signatures approach modern values at shallower depths, indicating that only ~21% of the methane in surface waters is sourced from seeps. We observe a mid-depth methane concentration maximum and radiocarbon minimum at ~200 m below the surface, but this likely reflects lateral advection of fossil methane from shallower seep fields. Our findings are consistent with previous radiocarbon fingerprinting in coastal regions, and suggest that seeps deeper than ~400 m are not a major contributor to atmospheric methane emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methane (CH4) is an important greenhouse gas with an atmospheric warming potential 80 times higher than carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-year time frame1. Over the last two centuries, CH4 emissions have nearly doubled, primarily resulting from human activities, and the atmospheric CH4 inventory is persistently rising at an average global rate of 19 ± 8 Tg CH4/yr1. It is anticipated that CH4 emissions will further increase in response to agricultural practices and increased natural gas utilisation as a fossil fuel, as well as perturbation of natural CH4 sources by climate and land-use change2.

Oceans make a considerable contribution to natural CH4 emissions to the atmosphere3, with sources that can be classified broadly as either modern or fossil. Modern oceanic CH4 is formed via anaerobic or aerobic methanogenesis from relatively modern carbon precursors (e.g., refs. 4,5,6,7,8), while fossil oceanic CH4 is released at the seafloor via hydrocarbon seeps, decomposing clathrates, or degraded subsea permafrost (e.g., refs. 4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13). Fossil oceanic CH4 sources are of particular interest because of (i) the potential for CH4 clathrates to dissociate and subsea permafrost to degrade due to ocean warming, driving a positive climate feedback14 and (ii) the importance of constraining the natural sources of fossil CH4 to the atmosphere in the context of increasing anthropogenic emissions of fossilised CH415.

In oceanic systems, CH4 clathrate hydrate dissociation has the potential to release fossil CH4 into the water column and atmosphere. These ice-like structures, composed of water and CH4 molecules, store approximately 1800 Gt C (1015 g) of CH4 globally and are sensitive to intermediate depth warming14,16. In shallow (<200 m) arctic regions17, decomposing clathrates can contribute CH4 directly to the atmosphere via ebullition, however, some emissions have been suggested to be episodic rather than consistent18. In addition to ebullitive emissions, diffusive sea-to-air fluxes of dissolved seep CH4 can be substantial, as observed at Coal Oil Point in the Santa Barbara Channel19,20.

Outside of these shallow regions, fossil CH4 released via hydrocarbon seeps or decomposing clathrates into deeper water has been shown to drive negligible atmospheric emissions (e.g., refs. 20,21,22). Measurements of the natural radiocarbon (14C) content of CH4 above active seafloor seeps along US margins found fossil CH4 dissolved in deep waters, but only modern CH4 in surface waters when the total water column depth was >500 m9. These results highlight the efficiency of bubble dissolution, aerobic oxidation of CH4, and dilution9 at limiting the transfer of CH4 to the atmosphere from seeps at depths where dissociating hydrates are found in mid-latitude regions (500–600 m). However, contrasting findings suggest that deepwater (>500 m) hydrocarbon seeps can drive substantial diffusive sea-to-air CH4 fluxes, particularly in locations where gas bubbles coexist with oil, protecting CH4 bubbles and slowing dissolution rates (e.g., Gulf of Mexico23).

The transport of CH4 bubbles from the seafloor to surface waters is influenced by myriad factors, including: (i) the bubble size distribution and release depth24; (ii) water temperature, salinity, and dissolved [CH4]; and (iii) the presence of surfactant, hydrate, or oil coatings on the bubble surface25. Simulations using bubble plume models26 suggest that bubbles without an oil coating released at depths >230 m are unlikely to release CH4 to the atmosphere. Nonetheless, recent work modeling the dynamics of oil-coated bubbles in deep ocean conditions27 found that 5 mm diameter gas bubbles released at a water depth of approximately 470 m could transport fossil CH4 to the surface ocean, though only <0.5% of the initial CH4 remained in the bubble. Once dissolved in seawater, CH4 can be diluted through mixing, laterally transported outside the seep field, and oxidized via microbial activities (e.g., refs. 28,29,30), further minimizing atmospheric release. Therefore, due to the complex interplay of physical, chemical, and biological factors influencing the transfer of seep-derived CH4, the contribution of fossil oceanic CH4 to the atmospheric budget remains uncertain.

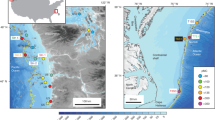

To further elucidate the dynamics of fossil CH4 released from seeps and resolve discrepancies in the release of fossil oceanic CH4 to the atmosphere23,31, we analyzed the concentration and 14C content (Δ14C-CH4) of CH4 dissolved in seawater across the northern Gulf of Mexico. We sampled above previously identified seafloor CH4 seeps and in locations without known fossil CH4 influences (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Our study aims to partition the contribution of fossil CH4 in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, specifically at two seep sites in Green Canyon block 185 (GC-185); Bush Hill (BHS) and a shallow seep (SS) at a water depths of approximately 550 m and 130 m, respectively. BHS is a well-studied seep site associated with oil emissions, resulting in some bubbles being coated with oil23. The CH4 flux from this seep is highly variable and modulated by hydrate formation and dissociation32,33. Despite this variability, the seep is long-lived and supports a hydrocarbon-based ecosystem, as evidenced by authigenic carbonate precipitation34,35,36. In contrast, the SS sites located on the continental shelf of Louisiana do not exhibit oil leakage from the seafloor. To provide a broader environmental context, we also included a site with no observed seafloor seeps as a background site, and collected several surface-only samples, including those from the Mississippi River (MR) plume and an offshore location.

Yellow polygons (with white lines) represent the seep anomalies identified by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Vertical 14C-CH4 distributions were investigated at the BHS, SS, and Background sites, and surface-only samples were collected from the ATGOM-U9, -U10, -U12, and MR plume sites.

Results and discussion

Concentration and 14C content of dissolved CH4 in the water column

Measured CH4 concentrations at the BHS site were around 60 nM in bottom waters and reached their lowest levels (<1 nM) at a depth of ~250 m (Figs. 2a and 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). The concentration exhibited an intermediate peak at ~100 m (17.7 nM), then decreased to 4.3 nM at the surface. Although the magnitudes differed, the vertical structure of the [CH4] profile we observed was consistent with findings from a previous study23 conducted at the same site. At the SS site, water column CH4 concentrations were considerably higher than those at BHS, except for the bottom water, where [CH4] was 35.6 nM. Interestingly, the maximum CH4 concentration of 79.3 nM was observed at a depth of 80 m, approximately 50 m above the seafloor. From there, the concentration gradually decreased towards the surface, where it was measured to be 7.1 nM. For the background site, the bottom water concentration started at 2.1 nM and gradually increased to a maximum of 5.6 nM at a depth of 65 m, before decreasing gradually to 2.6 nM at the surface (Fig. 2a). Atmospheric [CH4] was in the ranges of 1.9 ppm to 2.4 ppm along the entire our study track in Gulf of Mexico (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Vertical profiles of: a dissolved concentrations of measured (colored symbols) and seep-derived CH4 estimated using Fs × [CH4] (open symbols), b Δ14C, and c Seep-sourced fraction of CH4 (Fs). Fs is calculated using two possible 14C-CH4 end-member values for CH4 not sourced from seeps: 132 percent modern carbon (pMC) and 100 pMC, representing atmospheric equilibrium and CH4 formed from contemporary organic matter, respectively. For surface Fs calculation, 132 pMC was used for CH4 not sourced from seeps due to air-sea equilibrium at this station. Surface 14C contents and concentrations of CH4 are also shown in Fig. 3.

The Δ14C-CH4 values observed at our sampling sites spanned a range from 1.5 to 131.9 percent modern carbon (pMC) (Figs. 2b and 3). In our deepest measurement at BHS (470 m; 80 m above the seafloor) Δ14C-CH4 was 1.5 pMC, but 14C content increased to 36.1 pMC at a depth of 200 m, where the CH4 concentration decreased considerably to 1.7 nM. The Δ14C-CH4 value then decreased to 14.8 pMC at 100 m, corresponding to the subsurface concentration maximum (Fig. 2b), before increasing rapidly to 103.9 pMC in the surface water. At the SS site, the Δ14C-CH4 value was 3.4 pMC in bottom waters, and increased to 10.4 pMC and 82.6 pMC at 30 m and the surface, respectively. At the background site where no seafloor seeps have previously been reported, the Δ14C-CH4 values in the bottom and surface waters were 103.1 pMC and 131.9 pMC, respectively. It should be noted that the deepest samples for Δ14C-CH4 measurement were collected approximately 80 m above the seafloor for BHS and 10–20 m for the SS and background sites, to avoid contact between our sampling system and seafloor (see “Methods” section). Therefore, it is likely that the bottom water close to the seafloor may have Δ14C-CH4 values even closer to 0 pMC in the two seep sites (Fig. 2b).

Methane sources in the water column

The Δ14C-CH4 value of 103.1 pMC in bottom waters at the background site (Fig. 2), is similar to that expected for CH4 produced from contemporary organic matter (~100 pMC)5,37. This shallow background site (approximately 170 m of water depth), therefore, likely contains CH4 produced recently from anaerobic respiration of organic matter in the sediment. Recent studies have shown that the 14C content of sedimentary organic matter in the northern GOM ranges from approximately 80–90 pMC, with higher (younger) values closer to the land38,39,40. CH4 produced biologically in sediments at the background site would therefore likely contain ~90 pMC, since CH4 produced from recently fixed organic matter usually matches the 14C content of the organic precursor4,5,6,7. The slightly elevated Δ14C-CH4 value (103.1 pMC) we observed in the bottom water of the background site could result from mixing with surface waters, where Δ14C-CH4 is at atmospheric equilibrium (131.9 pMC). Therefore, measured Δ14C-CH4 at the background site is most consistent with a modern organic matter source of CH4, with negligible influence of seep-sourced fossil CH4.

The Δ14C-CH4 measured in near-bottom waters at both seep sites was found to be strongly depleted (<4.0 pMC) compared to the contemporary value observed in the ocean surface and the background site (Figs. 2 and 3). These depleted Δ14C-CH4 values cannot be explained by the 14C content typically found in GOM organic matter (~90 pMC), ruling out a more modern biological sedimentary source for this CH4. It is widely reported that CH4 derived from gas-hydrate dissociation and natural hydrocarbon seeps is devoid of 14C9. Our Δ14C-CH4 measurements at the BHS and SS sites therefore confirm that the elevated CH4 in bottom waters was indeed derived from natural seeps fed by gas-hydrate dissociation and other sub-seafloor hydrocarbon reservoirs. We note that CH4 leakage from the oil and gas infrastructure near this study site in the northern Gulf of Mexico may also represent an additional fossil CH4 source to the water column (Supplementary Fig. 1). At both seep sites, we observed a general decline in CH4 concentration and a transition towards modern Δ14C-CH4 values moving from the seafloor toward surface (Fig. 2). Previous studies in the northern GOM have reported similar vertical concentration profiles23,41,42 and suggested that the removal was attributed to oxidation42,43. However, if oxidation were the only process influencing the dissolved CH4 concentration, the Δ14C-CH4 profile would remain relatively close to the bottom water endmember values (e.g., 1.5 pMC at BHS) since the unit of pMC removes isotopic fractionation effects (e.g., microbial oxidation) through 13C normalization44. The increase in Δ14C-CH4 with altitude above the seafloor indicates the introduction of contemporary CH4, suggesting that dilution of seep-plume waters with background waters (with low [CH4] and modern Δ14C-CH4) also influences the CH4 distribution in these seep sites.

To calculate the fraction of CH4 dissolved in the water column that originates from seeps (FS), a radiocarbon isotopic mass balance was conducted (Eq. 1).

Here, 14Cm is the measured value of Δ14C-CH4 at a specific location and depth, 14Cs is the end-member Δ14C-CH4 value for seep-sourced CH4 (0 pMC), and 14Cb is the Δ14C-CH4 value for a “background” end-member. For samples in surface water, where CH4 exchanges rapidly with the atmosphere, we used the modern atmospheric end-member of 131.9 pMC measured at the background station for 14Cb. In deeper waters, we set 14Cb to either the atmospheric value or the modern organic matter value of 100 pMC to derive two different estimates of Fs. This balance reveals that CH4 in bottom waters at both seep sites is almost entirely (>99%) seep-derived, and the seep contribution gradually decreases with altitude above the seafloor (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 3), reaching 21% and 37% at the surface of BHS and SS, respectively. At BHS, this vertical trend is interrupted by a subsurface maximum of ~85% seep-sourced CH4 at ~100 m (Fig. 2c), which we discuss in the following sections. We note that Fs was estimated under the assumption of a simple two-endmember mixing between atmospheric and seep-derived components. Therefore, this represents the maximum potential seep contribution, since CH₄ in the surface layer can also be produced from modern dissolved organic carbon (DOC) through aerobic methanogenesis (e.g., ref. 8). In the Gulf of Mexico, the radiocarbon (¹⁴C) content of surface DOC is approximately 90 pMC38, suggesting that the true seep contribution to surface waters could be considerably lower than our estimated Fs if there is also a CH₄ endmember derived from this DOM.

The vertical structure of Fs we calculate at the BHS site indicates that seep-sourced CH4 is largely confined at depth and makes a limited contribution to surface waters, even in this highly active field of >500 m deep seeps. A similar observation was reported in the US-Atlantic margins, where seep CH4 does not reach the surface or atmosphere in water columns deeper than 500 m9. In addition to its limited vertical propagation, our results also indicate that seep-sourced CH4 is localized in its lateral extent. Our background station showed no contribution of seep-sourced CH4 in bottom waters, even though it is situated close to the margin (within ~100 km) of the dense seep fields (Fig. 1), and is downstream with respect to the large-scale GOM loop current45. Surface current velocities were approximately 0.1 ms−1 during this study (Fig. 4), thus, it would take approximately 10 days for water masses to travel from the seep field to the background site. Assuming a CH₄ oxidation rate constant of 0.2 per day, as measured previously in this region46, fossil seep CH₄ inputs would likely not be observed at the surface of the background site, which agrees with the results of this study. This suggests seep CH4 is not transported far from the confines of the seepage region, similar to a previous conclusion in the Santa Barbara Basin28. Furthermore, the fact that the seep-sourced Δ14C-CH4 signal at the BHS site is replaced by a contemporary background signal within a few hundred meters of the seafloor suggests that even within the dense seep field, much of the [CH4] profile is not seep-sourced. It therefore seems that seep CH4 is confined only to the waters surrounding individual seep mounds/anomalies (km scale), as opposed to the more regional-scale dispersal and oxidation which occurred during a large anthropogenic CH4 and oil hydrocarbon release47 and in enclosed basins4.

Daily-mean geostrophic surface currents during the sample collection on: a 7/7, b 7/8, c 7/9, and d 7/10/2022. Data for the surface currents were obtained from NOAA (https://cwcgom.aoml.noaa.gov/erddap/griddap/miamicurrents). Colored dots represent 14C-CH4 dissolved in surface waters in units of pMC.

Surface water radiocarbon in methane

The Δ14C-CH4 signatures measured in surface waters at our background site and in the center of the Gulf of Mexico (ATGOM-9) were 131.9 pMC and 131.8, respectively (Fig. 3), which is comparable to the current atmospheric value of 130–133 pMC48. In pristine marine environments that are unaffected by river inflow and local anthropogenic activities like nuclear power (releasing gaseous 14C as CH4), surface water Δ14C-CH4 tends to reach equilibrium with atmospheric values5,13. This confirms that at our background site (and throughout the central GOM) surface water CH4 is controlled largely by atmospheric equilibrium and shows no influence of natural seepage or local anthropogenic activities.

In contrast to the background site, the surface water Δ14C-CH4 values at both seep sites were depleted relative to the atmosphere and the background site, indicating that the surface CH4 at these locations is influenced by additional sources, although more so at the SS site. The SS site, located approximately 120 km from the shore, is likely influenced by freshwater sources such as the Atchafalaya and Mississippi Rivers (AR and MR, respectively), as evidenced by the surface water salinity of 29.6. However, the Δ14C-CH4 value of MR plume waters (collected ~16 km from one of the main MR outflows at a salinity of 15.0) was 90.3 pMC, and only ~31% of the surface water at the SS site was sourced from the MR plume according to salinity balance. The Δ14C-CH4 value of 82.6 pMC we measured in surface water at the SS site, therefore, cannot be explained as a mixture between the MR plume water and surface water equilibrated with the atmosphere, which would yield ~121.0 pMC.

Furthermore, given the 14C content of DOC measured in the GOM (~90 pMC, 37), aerobic methanogenesis using a DOC precursor cannot explain the Δ14C-CH4 observed at the SS site. Instead, the low Δ14C-CH4 in surface waters likely results from a considerable input of CH4 originating from the seafloor seep (Fs = 37%, Supplementary Table 3). Joung et al.9,28 observed depleted Δ14C-CH4 values in surface waters off the US Atlantic and Pacific margins and concluded that natural seeps on the seafloor can deliver CH4 to the ocean surface at sites with depths shallower than 350 m. Our measurements at the SS site (130 m water depth), therefore, align with previous studies, confirming that SSs can serve as sources of fossil CH4 to the atmosphere.

At the deep seep (BHS) site, the surface Δ14C-CH4 value of 103.9 pMC was found to be slightly depleted compared to atmospheric levels, and slightly higher than contemporary DOC38. The CH4 concentration of 4.2 nM measured in these surface waters was approximately double the air-sea equilibrium concentration of 2.1 nM at the conditions of 2.4 ppm atmospheric pCH4 (the highest atmospheric concentration observed near BHS), salinity of 31, and temperature of 31 °C (Supplementary Figs. 2a and 3), and cannot be explained by bubble-induced supersaturation which is at most 5% under the wind speed conditions we observed <10 km hr−1 (Supplementary Fig. 2b)49. This indicates additional sources of CH4 to the mixed layer, beyond atmospheric equilibration. In oligotrophic oceans with limited phosphate availability, CH4 can be produced through bacterial breakdown of methylphosphonate8. However, even attributing all of the CH4 supersaturation in BHS surface waters (2.3 nM, 55% of total CH4) to biological production would result in a Δ14C-CH4 value of 108.9 pMC, based on mixing calculations using 14C values of DOC measured in the GOM (~90 pMC, 38). This estimate demonstrates that aerobic CH4 production alone cannot account for the observed Δ14C-CH4 of 103.9 pMC at the BHS site. Furthermore, the surface salinity at BHS of 34.0 indicates minimal influence from the MR plume. Therefore, it is likely that surface CH4 for the BHS site includes a contribution from seep sources (Fs = 21% according to our radiocarbon mass balance, Supplementary Table 3). At a neighboring site within GC-185 with a bottom depth of 910 m (ATGOM-U10, ~60 km from BHS), we measured Δ14C-CH4 of 112.0 pMC in surface waters, corresponding to a seep CH4 contribution of 15% (Figs. 2 and 4, and Supplementary Table 3). These findings support previous work that attributed elevated [CH4] in the surface of deep water columns (bottom depth > 500 m) at GC-185 to seafloor seeps23,31. However, the concentrations we observed were relatively low, and we estimate that seeps contribute a minority of surface CH4. Additionally, it is unclear whether the seep-derived CH4 in the surface originates from the deep seafloor seeps themselves (e.g., BHS) or is transported laterally from other seep-impacted sites.

Lateral advection of CH4 from SS sites

The presence of depleted Δ14C-CH4 values in the surface water of the BHS site in GC-185 suggests the existence of fossil (or seep-sourced) CH4 in the mixed layer. There are two potential mechanisms for the delivery of fossil CH4 to surface waters at the BHS: vertical migration from the known seafloor seep at this site, or lateral advection of water impacted by shallower seeps. It seems unlikely that vertical diffusion or upwelling are the only transport mechanisms of fossil CH4 between the seafloor and the sea surface, since the concentration of dissolved CH4 reaches a minimum at intermediate depths, both in our observations (Fig. 2a) and previous studies (e.g., refs. 23,41,43,47).

Bubble transport from the seafloor to the surface has been hypothesized as a vector for seep-derived CH4 to the surface at this site. Solomon et al.23 tracked bubble plumes from the seafloor to the surface using a submersible and analyzed CH4 concentrations in samples collected during ascent. They reported surface CH4 concentrations as high as 1609 nM (608 nM in surface water of BHS). However, the surface CH4 concentration we measured (4.3 nM) was considerably lower than those reported by Solomon et al.23, but similar to those reported by Hu et al.31 (ranging from 1.72 to 4.48 nM). To date, no studies in Gulf of Mexico surface water above deepwater seeps have observed similar high concentrations of dissolved CH4 as were reported in Solomon et al.23.

Solomon et al.23 also observed a mid-depth [CH4] minimum, and suggested that the extremely high surface concentrations they observed could result from bubbles larger than 4.5 mm in size that dissolved in the surface layer, based on a simplified bubble propagation model. In that model, large oil-coated bubbles fully dissolved at the bottom of the mixed layer or shallower, where they encountered sharp density gradients between plume fluids and ambient seawater, causing CH4 to accumulate to 30–954 times atmospheric equilibrium. However, a recent modeling study by Gros et al.27 demonstrated that while large oil-coated bubbles can reach the ocean surface, most of the CH4 they carry will dissolve into the seawater during their ascent. Using a dynamic bubble model (Texas A&M Oil Spill/Outfall Calculator—TAMOC), they simulated 5 mm diameter CH4 bubbles with oil coatings and found no meaningful fraction (<0.1%) of the original CH4 was delivered to surface waters when the release depth was greater than 200 m. This suggests that bubbles formed at the BHS site, with a water depth of ~550 m, would not carry a substantial CH4 content by the time they reach the surface. Moreover, recent models (e.g., refs. 26,27) suggest that rising bubbles rapidly exchange gases with surrounding waters during their whole ascent, rather than dissolving specifically in surface waters. Consequently, the BHS CH4 concentration profiles observed here and in previous work23,31, which decrease rapidly with altitude before increasing again near the surface, likely cannot be explained by the dynamics of vertical bubble transport alone. Instead, the CH4 depletion at mid depths suggests that CH4 released from bubbles is rapidly removed by oxidation and dilution43, and confined within a few hundred meters of the seafloor, while there is an additional influence from lateral transport in the upper water column.

Our measurements reveal a subsurface CH4 concentration peak centered at ~100 m at the BHS site, where [CH4] is ~4-fold higher than at the surface. This further undercuts the hypothesis that elevated surface [CH4] is driven by bubbles “breaking” at the base of the mixed layer23, since the mixed layer was 20–30 m during our sampling (Supplementary Fig. 1), which is typical for summertime at this site44. Subsurface [CH4] peaks have been observed in previous studies in the Gulf of Mexico23,50,51, and are often attributed to CH4 production by microbial processes41,50. However, at the BHS site, the [CH4] peak is accompanied by a subsurface minimum in Δ14C-CH4 of 14.8 pMC (Fig. 2b), which is far too low to be explained by microbial production from a modern organic matter precursor. As for the source, our observations suggest that the elevated subsurface [CH4] originates from a seep source (Fs reaches a peak of ~85% at 100 m, Supplementary Table 3), albeit not the deep seep at this specific location.

One previous study attributed a mid-depth CH4 peak observed in the northern Gulf of Mexico to lateral advection from the edge of the continental shelf across the shelf break51. We therefore explored whether advection of seep-derived CH4 from SSs on the continental shelf could explain the elevated [CH4] with depleted Δ14C-CH4 (relative to atmosphere) that we observed in the top ~100 m at the BHS site. During our sampling period, surface currents in the region surrounding BHS were directed towards the south or southwest (Fig. 4), creating favorable conditions for advection of shelf water across the shelf break. In fact, for most of the sampling period, the BHS site was directly downstream from our SS site (36 km northeast of BHS), allowing our SS samples to be interpreted as an upstream endmember.

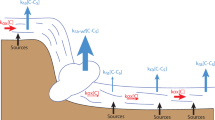

According to a simple mixing and equilibration calculation (e.g., ref. 20), the surface CH4 concentration observed at BHS could be explained as a mixture of ~44% surface water from the SS site and ~56% atmosphere-equilibrated water, which could either represent equilibration of the SS precursor during its advection, or dilution with equilibrated background water. In turn, this would predict a surface Δ14C-CH4 value of 95.5 pMC at BHS, which is similar to the observed value of 103.9 pMC (although we acknowledge this calculation does not account for losses due to oxidation or additional inputs like microbial production). Therefore, it is highly plausible that lateral advection of surface water masses carrying CH4 from SSs, or from any leaks in the oil/gas infrastructure, was responsible for the presence of fossil CH4 in surface water at the BHS site (Fig. 5). The subsurface (~100 m) CH4 concentration peak and Δ14C-CH4 minimum at BHS can then be interpreted as advected near-bottom waters from the SS site or other similar seeps on the continental shelf, which contain almost exclusively seep-sourced CH4 (Figs. 2c and 5). The depth of this peak would therefore depend on the depth of shelf waters being advected offshore, and the penetration depth of cross-shelf currents, which may vary both in space and time.

Reconciling methane dynamics in GOM surface waters

Previous studies have reported contrasting CH4 dynamics in surface waters of the Gulf of Mexico GC-185 region. Solomon et al.23 documented surface CH4 concentrations ranging from 650-1605 nM, representing considerable supersaturation (30-954 times) above atmospheric equilibrium, whereas Hu et al.31 observed only modest supersaturation (4.48 nM, ~2 times equilibrium) at the same location. Hu et al.31 deliberated on the elevated CH4 levels observed by Solomon et al., attributing them to localized hotspots of CH4 emanating from seafloor seeps, which were not pinpointed during resampling. They proposed that the elevated CH4 could originate either from seeps within the sampled sites, or be advected from shallower seep locations to the sampling site. Our new 14C-CH4 measurements confirm that seep-sourced CH4 is present in the surface and mid-depths at BHS, but suggest that it only makes a minor contribution (<21% or <1 nM, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3) to the dissolved mixed-layer CH4 inventory. In addition, our Δ14C-CH4 and CH4 concentration measurements suggest that much of the near-surface seep-derived CH4 was laterally transported to the BHS site, rather than transmitted vertically from the seep at ~550 m depth as posited by Solomon et al.23. During the sampling period for that prior study, (August 14–23, 2003), surface currents were also directed southwards towards the center of the Gulf of Mexico, though considerable variations were observed over the span of hours and days (Supplementary Fig. 4). This flow pattern would be conducive to water mass transport from shallower seep regions to the deeper sites, as postulated for our sampling period, and it may plausibly explain the high CH4 concentrations reported by Solomon et al. Even if the elevated CH4 was transmitted vertically from the 550-deep seep, the considerably lower CH4 concentrations observed in follow-up studies at the same site suggest that CH4 hotspots in surface waters at BHS are extremely limited in space and time, similar to other seep fields28. Alternatively, seepage at BHS could be ephemeral in bubble size distribution, bubble coatings, or seafloor gas release rates, allowing for short episodes that are favorable for bubble propagation through the water column. However, previous studies have shown that under normal conditions, very little CH4 should reach surface waters from 550 m depth in this environment52, which would further diminish the annual atmospheric emissions of oceanic seep-derived CH4.

Overall, our results indicate that fossil seep-derived CH4 makes a limited contribution to surface waters in the GC-185 sector, and suggest that the impact of deep seep-derived CH4 on atmospheric emissions is localized and minor despite the presence of numerous seafloor seeps in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Furthermore, the advection of water masses from SS sites, rather than vertical transmission from deep seeps, appears to be an important factor controlling the water column distribution of seep-derived CH4 in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 5). This supports and builds upon previous findings from the US Atlantic and Pacific margins9, which showed that fossil CH4 is not transmitted to the surface from seeps >500 m deep. Here, we showed that this applies even in regions of dense and active seepage, where oil may provide a protective bubble coating. This strengthens the building consensus that dissociating hydrates in mid-latitudes, which occur at depths >500 m, are unlikely to drive substantial emissions of CH4 to the atmosphere, especially as compared to direct anthropogenic emissions of fossil CH4 to the atmosphere53.

Methods and materials

Site description

The northern Gulf of Mexico harbors a vast number of seep anomalies, with over 36,000 identified (BOEM, https://www.boem.gov/oil-gas-energy/mapping-and-data/map-gallery/seismic-water-bottom-anomalies-map-gallery) (Fig. 1). Among these, the BHS site located in Green Canyon 185 (GC-185) is well-known and situated at a depth of approximately 550 m. The GC-185 gas seeps originate from gas reservoirs present in deep sediments, as well as gas-hydrate dissociation23,34,54,55,56,57,58. Geographically, the major fault system underlying the GC-185 block connects to the Jolliet hydrocarbon and oil reservoirs, intersecting the seafloor at the active site of hydrocarbon discharge (refer to Fig. 2 in 34). Consequently, the gas bubbles in the GC-185 seep fields are occasionally coated with oil, and ongoing gas venting results in visible bubble plumes in the water column as recorded by echo sounders. Additionally, the presence of oil sheen on the water surface can be observed by satellites23,55,58. While sonar was not used to confirm active bubble release from BHS during our sampling, we did observe oil-coated bubbles surfacing at the site. Methane concentrations in this area are strongly elevated, reaching up to 13,660 nM at the bottom and up to 1600 nM in the surface layer23.

A SS site was selected for this study based on previous observations conducted by the BOEM (Fig. 1). This site is located in the continental shelf with a water depth of approximately 130 m and is situated around 130 km from the Louisiana coast. While there is no specific information regarding the geographic features of this site, it is likely to share similarities with the GC block, as it is only about 35 km northeast of GC-185. However, according to the BOEM’s seismic seep field anomaly investigations, this location is not categorized as an oil-related anomaly (neither confirmed-oil nor possible-oil in both positive and negative anomalies). Additionally, due to the shallow water depth (~130 m), it is not expected to harbor gas hydrates on the seafloor. Consequently, the bubbles observed in this system would be classified as “not oil coated,” indicating their origin from natural hydrocarbon seeps.

A background site situated at a water depth of approximately 170 m was also chosen for comparison. This site is located at the head of De Soto Canyon, approximately 60 km off Pensacola Beach, Florida, USA. No seep activity was observed at this site, as reported by the BOEM (Fig. 1).

Sample collection

For the 14C-CH4 analysis, water samples were collected from a total of six sites, including three sites for vertical profile investigations and three surface-only sites. The vertical investigation sites consisted of two seep sites, namely BHS in GC-185 and an SS, along with one background site. The purpose of these vertical profile sites was to examine the CH4 dynamics in the water column. In addition, surface-only samples were collected from three different locations. The first surface-only sample was taken from the MR plume, which represents a distinct water mass influenced by riverine inputs. The second surface-only sample was obtained from a seep field near GC-185, specifically referred to as ATGOM-U10. Lastly, a sample was collected from a far-offshore location with a water column depth of approximately 3000 meters, referred to as ATGOM-U9. These sampling sites were chosen to provide a comprehensive understanding of the CH4 distribution and dynamics, encompassing both vertical profiles and surface conditions in various locations within the study area.

The details of the 14C-CH4 sample collection and measurements can be found in the works of Sparrow and Kessler6,59, as well as Joung et al.9,13,28,60. The equipment specifications used in this study are provided in Sparrow and Kessler59. The process of water sample collection and preparation involved two main steps: field gas sample collection and laboratory gas sample purification. In the field, CH4 was extracted from the water and compressed, then stored in a small gas cylinder. Briefly, a discharge pump was used to draw water from the desired depths and introduce it to the gas extraction system on the deck. The pumped water underwent filtration through sequentially decreasing pore sizes of 100 µm, 50 µm, and 10 (or 5) µm to remove particles that could potentially damage the membrane filters. The filtered water was then passed through the membrane filters, which consisted of a water and a vacuum side. Vacuum pressure was applied to the vacuum side of the membrane while the water flowed through the water side, facilitating the extraction of dissolved gases from the water. The extracted gases were compressed and stored in a gas cylinder, which was transported back to the laboratory for further processing of the samples.

In the laboratory, the gas samples in the cylinder were analyzed for their concentrations, including other carbon-containing gases such as CO2 and CO, to assess the recovery of carbon from CH4 during the final stage of analysis. The gas cylinder was connected to a vacuum line to purify the gas samples. The extracted gas sample was then passed through a molecular sieve and the first liquid nitrogen (LN) trap to remove CO2. The remaining gases, including CO and CH4, were directed through the first oven set at 600 °C to convert CO to CO2. The resulting CO2 was subsequently removed by the second LN trap. Finally, the gases were introduced to the second oven, which was set at 1000 °C to convert CH4 to CO2. The CO2, now trapped in the third LN trap, was transferred to a pre-combusted glass tube and flame-sealed. This CO2-containing glass tube was sent to the Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (AMS) facility at UC Irvine for determination of its 14C values.

To assess the performance of the sample purification system, two standards containing different carbon species (CO2, CO, and CH4) and concentrations were processed alongside every two to three days, following the same procedures as the samples. Analysis of the standards revealed 14C-CH4 values of approximately 0 pMC (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the standards were monitored continuously to ensure the complete removal of CO2 and CO, as well as the full conversion of CH4 to CO2 and subsequent trapping.

To evaluate background carbon in the purification system, ultra-zero-grade air was passed through the system for 1–2 h. This test was conducted daily, just prior to running the samples. The background carbon concentration was found to be less than 0.005 µg/L, which amounted to less than 0.4% of the sample carbon collection (250 µg-C when processing 180 L of sample). Since the gas sample volume used for analysis was typically less than 100 L, the percentile contribution of the background carbon was even lower than 0.3%, similar to the instrumental background level of 0.1% (or 2–3 ‰,61). Nevertheless, this background carbon is not expected to have any impact on the 14C-CH4 values obtained from the samples.

Our measurement technique for 14C in CH4 requires approximately 250 µg of carbon in total. The water volume for CH4 extraction can vary depending on the CH4 concentrations in the water samples. For instance, surface waters with a concentration of 2 nM would typically require over 35,000 L of water, taking into account the gas extraction efficiency of the membrane filters and system cleaning9. Furthermore, discrete bottle samples were also collected at the same locations as the 14C-CH4 sample collection sites to determine the concentrations of CH4. The CH4 concentrations were analyzed following the method described by Weinstein et al.62.

Data availability

All data are available within the article and Supplementary Data, and have been archived on the Figshare repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30559832.v1.

References

Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 673–816 (Cambridge University Press, 2021); https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.007.

Hamdan, L. J. & Wickland, K. P. Methane emissions from oceans, coasts, and freshwater habitats: new perspectives and feedbacks on climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, S3–S12 (2016).

Weber, T., Wiseman, N. A. & Kock, A. Global ocean methane emissions dominated by shallow coastal waters. Nat. Commun. 10, 4584 (2019).

Kessler, J. D., Reeburgh, W. S., Southon, J. & Varela, R. Fossil methane source dominates Cariaco Basin water column methane geochemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L12609 (2005).

Kessler, J. D. et al. A survey of methane isotope abundance (14C, 13C, 2H) from five nearshore marine basins that reveals unusual radiocarbon levels in subsurface waters. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C12021 (2008).

Sparrow, K. J. et al. Limited contribution of ancient methane to surface waters of the US Beaufort Sea shelf. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao4842 (2018).

Karl, D. M. et al. Aerobic production of methane in the sea. Nat. Geosci. 1, 473–476 (2008).

Repeta, D. J. et al. Marine methane paradox explained by bacterial degradation of dissolved organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 9, 884–887 (2016).

Joung, D., Ruppel, C., Southon, J., Weber, T. S. & Kessler, J. D. Negligible atmospheric release of methane from decomposing hydrates in mid‑latitude oceans. Nat. Geosci. 15, 885–891 (2022).

Grabowski, K. S. et al. Carbon pool analysis of methane hydrate regions in the seafloor by accelerator mass spectrometry. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 223, 435–440 (2004).

Pohlman, J. W. et al. Methane sources in gas hydrate‑bearing cold seeps: evidence from radiocarbon and stable isotopes. Mar. Chem. 115, 102–109 (2009).

Winckler, G. et al. Noble gases and radiocarbon in natural gas hydrates. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL014013 (2002).

Joung, D., Ruppel, C., Southon, J. & Kessler, J. D. Elevated levels of radiocarbon in methane dissolved in seawater reveal likely local contamination from nuclear powered vessels. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150456 (2022).

Ruppel, C. D. & Kessler, J. D. The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates. Rev. Geophys. 55, 126–168 (2017).

Hmiel, B., Petrenko, V. V. & Dyonisius, M. N. Preindustrial 14CH4 indicates greater anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions. Nature 578, 409–412 (2020).

Ruppel, C. D. Methane Hydrates and Contemporary Climate Change (Nature Education Knowledge, 2011).

Westbrook, G. K. et al. Escape of methane gas from the seabed along the West Spitsbergen continental margin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L15608 (2009).

Hong, W. L. et al. Seepage from an Arctic shallow marine gas hydrate reservoir is insensitive to momentary ocean warming. Nat. Commun. 8, 15745 (2017).

Mau, S. et al. Dissolved methane distributions and air–sea flux in the plume of a massive seep field, Coal Oil Point, California. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L22603 (2007).

Schmale, O., Greinert, J. & Rehder, G. Methane emission from high‑intensity marine gas seeps in the Black Sea into the atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L07609 (2005).

Kessler, J. D. et al. Basin‑wide estimates of the input of methane from seeps and clathrates to the Black Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 243, 366–375 (2006).

Reeburgh, W. S. Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 486–513 (2007).

Solomon, E. A., Kastner, M., MacDonald, I. R. & Leifer, I. Considerable methane fluxes to the atmosphere from hydrocarbon seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Nat. Geosci. 2, 561–565 (2009).

Socolofsky, S. A. & Adams, E. E. Multi‑phase plumes in uniform and stratified crossflow. J. Hydraul. Res. 40, 661–672 (2002).

Leifer, I. & MacDonald, I. R. Dynamics of the gas flux from shallow gas hydrate deposits: interaction between oily hydrate bubbles and the oceanic environment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 210, 411–424 (2003).

McGinnis, D. F., Greinert, J., Artemov, Y., Beaubien, S. E. & Wüest, A. Fate of rising methane bubbles in stratified waters: How much methane reaches the atmosphere? J. Geophys. Res. 111, C09007 (2006). Oceans.

Gros, J., Arey, J. S., Socolofsky, S. A. & Dissanayake, A. L. Dynamics of live oil droplets and natural gas bubbles in deep water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 11865–11875 (2020).

Joung, D. et al. Radiocarbon in marine methane reveals patchy impact of seeps on surface waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089516 (2020).

Leonte, M. et al. Rapid rates of aerobic methane oxidation at the feather edge of gas hydrate stability in the waters of Hudson Canyon, US Atlantic margin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 204, 375–387 (2017).

Leonte, M., Ruppel, C. D., Ruiz‑Angulo, A. & Kessler, J. D. Surface methane concentrations along the mid‑atlantic bight driven by aerobic subsurface production rather than seafloor gas seeps. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2019JC015989 (2020).

Hu, L., Yvon‑Lewis, S. A., Kessler, J. D. & MacDonald, I. R. Methane fluxes to the atmosphere from deepwater hydrocarbon seeps in the northern Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 117, C01009 (2012).

Tryon, M. D. & Brown, K. M. Fluid and chemical cycling at Bush Hill: implications for gas‑ and hydrate‑rich environments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 5, Q12003 (2004).

Solomon, E. A., Kastner, M., Jannasch, H., Robertson, G. & Weinstein, Y. Dynamic fluid flow and chemical fluxes associated with a seafloor gas hydrate deposit on the northern Gulf of Mexico slope. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 270, 95–105 (2008).

MacDonald, I. R. et al. Gas hydrate that breaches the sea floor on the continental slope of the Gulf of Mexico. Geology 22, 699–702 (1994).

Feng, D., Chen, D. & Roberts, H. H. Petrographic and geochemical characterization of seep carbonate from Bush Hill (GC 185) gas vent and hydrate site of the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pet. Geol. 26, 1190–1198 (2009).

Meurer, W. P., Blum, J. & Shipman, G. Volumetric mapping of methane concentrations at the Bush Hill hydrocarbon seep, Gulf of Mexico. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 604930 (2021).

Graven, H., Hocking, T. & Zazzeri, G. Detection of fossil and biogenic methane at regional scales using atmospheric radiocarbon. Earth’s Future 7, 283–299 (2019).

Walker, B. D. et al. Stable and radiocarbon isotopic composition of dissolved organic matter in the Gulf of Mexico. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8424–8434 (2017).

Chanton, J. Sediment Organic Isotope Data Collected in the Northern Gulf of Mexico Seafloor on Different Cruises from 2010‑05‑01 to 2017‑06‑18 (GRIIDC, 2019); https://doi.org/10.7266/N7Q52N7D.

Rogers, K. L. et al. Mapping spatial and temporal variation of seafloor organic matter Δ14C and δ13C in the northern Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 164, 112076 (2021).

Rakowski, C. V. et al. Methane and microbial dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico water column. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 69 (2015).

Rogener, M. K., Bracco, A., Hunter, K. S., Saxton, M. A. & Joye, S. B. Long‑term impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout on methane oxidation dynamics in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Elem. Sci. Anth. 6, 73 (2018).

Leonte, M. et al. Using carbon isotope fractionation to constrain the extent of methane dissolution into the water column surrounding a natural hydrocarbon gas seep in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 4459–4475 (2018).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Weisberg, R. H. & Liu, Y. On the loop current penetration into the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 9679–9694 (2017).

Chan, E. W. et al. Investigations of aerobic methane oxidation in two marine seep environments: Part 1—Chemical kinetics. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 8852–8868 (2019).

Kessler, J. D. et al. A persistent oxygen anomaly reveals the fate of spilled methane in the deep Gulf of Mexico. Science 331, 312–315 (2011).

Zazzeri, G., Xu, X. & Graven, H. Efficient sampling of atmospheric methane for radiocarbon analysis and quantification of fossil methane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 8535–8541 (2021).

Liang, J. H. et al. Parameterizing bubble‑mediated air–sea gas exchange and its effect on ocean ventilation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 894–905 (2013).

Rogers, K. L. et al. Sources of carbon to suspended particulate organic matter in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Elem. Sci. Anth. 7, 51 (2019).

Brooks, J. M., Reid, D. F. & Bernard, B. B. Methane in the upper water column of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 86, 11029–11040 (1981).

Wang, B., Jun, I., Socolofsky, S. A., DiMarco, S. F. & Kessler, J. D. Dynamics of gas bubbles from a submarine hydrocarbon seep within the hydrate stability zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089256 (2020).

Howarth, R. W. Ideas and perspectives: Is shale gas a major driver of recent increase in global atmospheric methane? Biogeosciences 16, 3033–3046 (2019).

Roberts, H. H. & Aharon, P. Hydrocarbon‑derived carbonate buildups of the northern Gulf of Mexico continental slope: a review of submersible investigations. Geo‑Mar. Lett. 14, 135–148 (1994).

Sassen, R. et al. Massive vein‑filling gas hydrate: relation to ongoing gas migration from the deep subsurface in the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pet. Geol. 18, 551–560 (2001).

MacDonald, I. R. et al. Transfer of hydrocarbons from natural seeps to the water column and atmosphere. Geofluids 2, 95–107 (2002).

Roberts, H. H., Sassen, R. & Milkov, A. V. Seafloor expression of fluid and gas expulsion from deep petroleum systems, continental slope of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Nat. Gas Hydrates. https://doi.org/10.1029/GM124p0145 (2001).

Chen, D. F. & Cathles, L. M. A kinetic model for the pattern and amounts of hydrate precipitated from a gas stream: application to the Bush Hill vent site, Green Canyon Block 185, Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2058 (2003).

Sparrow, K. J. & Kessler, J. D. Efficient collection and preparation of methane from low concentration waters for natural abundance radiocarbon analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 15, 601–617 (2017).

Joung, D., Leonte, M. & Kessler, J. D. Methane sources in the waters of Lake Michigan and Lake Superior as revealed by natural radiocarbon measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5436–5444 (2019).

Beverly, R. K. et al. The Keck Carbon Cycle AMS Laboratory, University of California, Irvine: status report. Radiocarbon 52, 301–309 (2010).

Weinstein, A. et al. Determining the flux of methane into Hudson Canyon at the edge of methane clathrate hydrate stability. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17, 3882–3892 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the excellent support received at sea from the crew of the R/V Hugh Sharp for the collection of these samples, as well as Madeline Every, Sydney Louden, and Rebecca Rust for assistance at sea in collecting these samples. This research was supported by the US National Science Foundation with a grant to J.K. and T.W. (OCE-1851402). D.J. was supported by Global-Learning & Academic research institution for Master’s·PhD students, and Postdocs (GLAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00301938) and by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2022R1A2C109112313).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J., T.W., and J.K. conceptualized and coordinated the study, secured funding, and contributed equally to the writing and organization of the manuscript. D.J., T.W., K.G., J.D., and J.K. conducted field surveys and collected data and samples. DJ processed the 14C-CH4 samples in both the field and laboratory. KG and JD performed gas chromatography and atmospheric CH4 analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks John Pohlman and Ira Leifer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ning Zhao and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joung, D., Weber, T., Gregory, K. et al. Deep Gulf of Mexico seeps are not a significant source of methane to the atmosphere. Commun Earth Environ 6, 999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03027-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03027-0