Abstract

Projecting El Niño-Southern Oscillation responses to future climate change are hindered by limited paleoclimate records spanning past abrupt climate transitions. This study combines multi-proxy records from the Northwest Borneo Trough over the past 30 kyr with transient climate simulations, reconstructing tropical western Pacific hydroclimate during Heinrich events and Bølling–Allerød warming. Results show contrasting responses: Heinrich events saw stronger winter monsoons bringing northern moisture for Borneo’s orographic rain, while Bølling–Allerød warming initiated central Pacific El Niño-like conditions tied to Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet retreat beyond a critical threshold and subsequently sustained by insolation minimum, combined with Southern Hemisphere forcing, leading to regional dryness/seasonal aridity. We demonstrate dual high-latitude controls on western Pacific variability during Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles: hemispheric thermal gradients and ice-sheet topography. These findings reveal the links between ice sheets, insolation, and western Pacific El Niño-like conditions, offering valuable insights into long-term El Niño-Southern Oscillation dynamics and future behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last glacial period, climate variability featured Dansgaard–Oeschger (D–O) oscillations, marked by millennial-scale warmer (interstadial) and colder (stadial) phases1. Some colder D–O stadials align with Heinrich events, identified by ice-rafted detritus in North Atlantic sediments2. Recently, these events have been documented in western Pacific Ocean and tropical Southeast Asia climate records, linked to Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)-driven changes in the East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) and/or the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, high-resolution records from the tropical western Pacific are lacking for assessing climate feedbacks and teleconnections during the abrupt warming of D–O interstadials. Understanding these processes is crucial, as interstadials provide a key analog for the dynamics and sensitivities of the global climate system during periods of rapid warming, which directly informs our understanding of contemporary climate change. Here, our high-resolution sedimentary records from the Northwest (NW) Borneo trough can enhance understanding of western Pacific hydroclimate changes under both D–O stadial and interstadial conditions and their potential links to high northern latitude forcings.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the leading cause of interannual climatic variability, profoundly impacting global temperature and precipitation patterns, and affecting human lives, livelihoods, and health10. To better understand ENSO variability and its potential relationship to orbital or climatic boundary conditions11,12,13,14,15,16,17, a network of paleoclimate records is essential. However, reconstructions of past ENSO variability from multiple paleo-proxy records have largely been limited to the Holocene and last glacial maximum (LGM)12,15,18,19,20,21,22,23, with sparse data at discrete time points over the late Pleistocene15,24,25,26. Additionally, there is a scarcity of high-resolution records capable of capturing ENSO-relevant hydroclimate variability spanning past D–O cycles—periods of millennial-scale climate boundary condition fluctuations27—which are considered key determinants of the long-term evolution of ENSO by both paleoclimate models and data11,13,15,17. A better understanding of how abrupt climate change affects ENSO mechanisms and feedbacks could enhance our knowledge of ENSO’s sensitivity to global climate change and potential responses to future warming. However, the relative roles of climate background conditions and insolation forcing in shaping ENSO behavior during these periods remain unclear. Specially, the Bølling–Allerød (B–A) interstadial or D–O interstadial 1 (14.7–12.9 kyr BP)28, marking the first abrupt Northern Hemisphere (NH) warming during the last deglaciation, could provide critical insights into the discrepancies between observed historical sea surface temperature (SST) gradient trends and climate model projections—where observational records appear to show a “La Niña-like” strengthening of the zonal SST gradient over the past century, whereas most climate model simulations project “El Niño-like” changes toward a weaker gradient—regarding long-term changes in tropical Pacific zonal SST gradients and the Walker circulation under warming scenarios29.

To bridge these knowledge gaps, we analyze a 30-ka high-resolution sedimentary sequence from the NW Borneo trough (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) spanning four D–O cycles, integrated with transient climate simulations. We suggest that the observed changes in our proxy records reflect local precipitation variations over the D–O cycles and can help unravel the tropical western Pacific’s responses at that time. To the best of our knowledge, our results provide the first insights into different hydrological feedbacks in the western Pacific during D–O interstadials and notable links between ENSO behavior and high northern latitude forcing during the B–A interstadial. These findings link climatic boundary conditions and insolation forcing to western Pacific ENSO-like conditions, enhancing our understanding of ENSO’s long-term dynamics and future behavior.

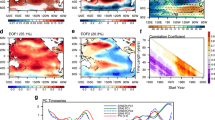

a Hydroclimate changes across the Asian-Pacific region during the B–A interstadial relative to 2015/2016 extreme El Niño conditions. Locations of climate proxy records showing relative hydroclimate changes at B–A as inferred from the synthesis in Supplementary Table 1. Background shading shows precipitation anomalies in GPCP V3.2 data97 are calculated by subtracting the mean of the entire GPCP V3.2 dataset (2001–2020) from the average precipitation during the strong El Niño events in 2015/2016. b Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) from 1980 to 2024. Time series of the ONI tracking the 3-month running-mean of SST in the east-central tropical Pacific since 1980. The El Niño threshold is reached when the ONI reaches +0.5 or greater for 5 consecutive months. Here, the maximum ONI index value presents during the 2015–2016 El Niño. c Locations of core CG18 and published planktonic foraminiferal Mg/Ca-based SST records from the equatorial Pacific referred to in this study15,53,64. The base map shows the modern annual mean SST distribution based on the World Ocean Atlas 2023 dataset98. The isothermal of 28 °C delineates the modern extents of the Indo-Pacific warm pool (IPWP). The dashed rectangles mark the western Pacific warm pool (WPWP), central and eastern equatorial Pacific (CEP and EEP), respectively. Specifically, region “a” is a part of “c” and is highlighted by a black solid-line box.

Results and discussion

Sediment provenance

Sediment provenance is crucial for interpreting geochemical and black carbon (BC) records in marine sediments. Supplementary Fig. 2 presents the relationship between 87Sr/86Sr ratios and εNd values for terrigenous sediments in core CG18 and potential source areas. Core CG18 samples exhibit less negative εNd values than those from the Mekong River30 and Sunda Shelf31, but align with those from NW Borneo31. This suggests that the terrigenous sediments in core CG18 are primarily sourced from NW Borneo.

The modern NW Borneo source-to-sink system is characterized by abundant rainfall, high topographic relief, narrow coastal plains and continental shelves, well-developed submarine channels on the continental slope, and multiple small-sized fluvial drainage basins9. These geological and climatic conditions, coupled with the study core’s proximity to NW Borneo, contribute to NW Borneo being a major sediment source for core CG18. This is corroborated by analyses of clay minerals and magnetic properties of surface sediments in the southern South China Sea (SCS)32.

The εNd values of core CG18 sediments show a stable trend (Fig. 2h), indicating that the sediment sources have remained relatively constant since 30 ka. Over the past 30 kyr, temporal variations in X-ray fluorescence (XRF)-derived element ratios and δ13C of BC in core CG18 primarily reflect riverine inputs and vegetation evolution within NW Borneo.

a The NGRIP δ18O record62 (5-point running average). b Mean grain size at Gulang on the Chinese Loess Plateau45. c Stalagmite δ18O records from Northwest Borneo99. d–h K/Ca and Ti/Ca ratios (this study; 31-point running average), magnetic susceptibility9, Δ13CBC−CO2 (this study), and εNd values9 from core CG18. i Global mean sea level curve over the last 30 kyr50. The vertical pink bars indicate Bølling–Allerød (BA) and Dansgaard–Oeschger (DO) interstadials, while the green bars identify Heinrich (H) events. The black triangles represent calibrated 14C ages.

Rainfall and vegetation responses in NW Borneo during the D–O cycles

Reconstructions of terrigenous flux primarily rely on potassium (K) and titanium (Ti). K predominantly represents clay mineral-bound proxies for fine-grained riverine runoff, such as illite, a major clay mineral in NW Borneo (~70%)33, while Ti is considered conservative during erosion and transport and is more associated with coarse, refractory minerals. Here, K and Ti were normalized against calcium (Ca), derived from biogenic carbonate, as useful proxies of precipitation and associated river runoff over the western Pacific4,8 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

BC residues, produced from incomplete combustion of plants and fossils34, can estimate changes in vegetation type in the source area, particularly the relative abundance of C3 versus C4 plants35,36. This is because the carbon isotope of BC particles (δ13CBC) systematically slightly differs from its precursory biomass due to the burning process37. The δ13C from C4 plants (−12.5 ± 1.1‰ on average) is much less negative than that from C3 plants (−26.7 ± 2.3‰ on average)38. In the tropics, the relative abundance of C3 versus C4 plants is largely controlled by precipitation and related hydroclimate variables, such as relative humidity and evaporation, with dry environments favoring C4 grasses and wet environments favoring C3 trees39. Herein, the effects of changes in the δ13C value of atmospheric CO2 on plants are eliminated using a reliable reconstruction of δ13C values of atmospheric CO2 from Antarctic ice cores40,41,42. The discriminated δ13C values between the atmosphere and BC (Δ13CBC−CO2) can approximately provide information on the distributions of the plant community by excluding changes in δ13C values of atmospheric CO236,43,44.

As shown in Fig. 2, divergent long-term trends in core CG18 proxy records reflect differential sensitivities to external forcings, while Heinrich events (H1, H2, H3) in NW Borneo featured enhanced riverine inputs and C3 vegetation expansion, implying intensified regional convection9. During these cold episodes, an intensified EAWM favors strong equatorward surges of cold air45. These cold surge outbreaks, with strong and concentrated low-level winds, are thought to be blocked and channeled by the adjacent orography (high mountains on the island) of the southern SCS, resulting in local near-surface convection (orographic uplift of moist air along the mountain range) and, eventually, higher rainfall in NW Borneo’s hinterlands46,47,48. The short distance (ca. 50–100 km) and relatively steep gradient from the hinterland to the coastline in NW Borneo facilitate peak transport and delivery of huge riverine sediments to the study core. Hence, our XRF and BC results confirm that a stronger EAWM during cold stadials could have transported high levels of northerly moisture to NW Borneo9. A pollen sequence from core CB19 in the NW Borneo trough demonstrates the downward expansion of upper montane forests with Podocarpus and Dacrydium as the main components during the Heinrich events49. This is consistent with more depleted Δ13CBC−CO2 values observed at core CG18 superimposed on these millennial events (Supplementary Fig. 4), further confirming that Δ13CBC−CO2 variations reflect vegetation changes in NW Borneo.

However, the clear signature of Heinrich events in core CG18 records contrasts with the lack of consistent D–O interstadial signals, revealing a distinct response of western Pacific hydrology to high-latitude abrupt climate change forcing. As displayed in Fig. 2g, from around 8.5 ka onwards, Δ13CBC−CO2 remained at ~−16‰, likely due to sea level rise-induced opening of the Indonesian Throughflow and transition to a present-day climate50,51, suggesting NW Borneo’s vegetation types have remained consistent since then. During D–O interstadials 2, 3, and 4, tropical vegetation responses mostly align with mid-late Holocene and/or current conditions within the NW Borneo catchment, differing from the B–A warming period, characterized by persistent C4 grassland expansion and/or forest contraction, possibly indicating a regionally dry and/or more seasonal aridity at the time. This discrepancy between D–O interstadials might imply the presence of a threshold forcing.

Hydroclimate reconstruction for northern Borneo during the B–A period

As shown in Fig. 2g, the long-term pattern of Δ13CBC−CO2 in core CG18 likely reflects catchment-wide transitions between closed-canopy rainforest and more open ecosystems, possibly with C4 grasses. However, pollen data from core CB19 in the NW Borneo trough, ~30 km from the study core, shows no pronounced increase in grass pollen (e.g., Poaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Herbs) during the B–A warming period (Supplementary Fig. 4). This suggests the δ13CBC values during the B–A (~−21‰; Supplementary Fig. 3e) do not require C4 grass incorporation but may reflect more open, C3 ecosystems with increased dry season water stress. Thus, we interpret depleted Δ13CBC−CO2 in core CG18 as indicating closed-canopy rainforest during Heinrich events, while enriched values suggest more open C3 forest during the B–A interstadial.

Given the multifactorial control on vegetation, temperature is unlikely to be the primary driver of changes in core CG18. The longer Δ13CBC−CO2 record from core CG18 does not align with either the land-temperature changes in NW Borneo52 (Fig. 3e) or the western Pacific warm pool (WPWP) SST stack53 (Fig. 3h) over the past 30 kyr. Although atmospheric CO2 concentrations affect vegetation type and δ13C, favoring C4 grasses at low CO254, the Δ13CBC−CO2 patterns from Marine Isotope stage (MIS) 2 through the Holocene at our site cannot be solely explained by CO2 changes. CO2 was lower during MIS 2 than the Holocene55,56 (Fig. 3j), yet our data shows similar Δ13CBC−CO2 values. Analyses of Indo-Pacific warm pool (IPWP) surface marine sediments indicate that the δ13C of vascular plant fatty acids strongly correlates with rainfall seasonality and average monthly precipitation57. Thus, we interpret the enriched Δ13CBC−CO2 in core CG18 as indicating increased dry season water stress during the B–A interstadial, likely due to reduced precipitation and/or a longer/intensified dry season in NW Borneo (currently July–August).

a The NGRIP δ18O record62 (5-point running average). b The WDC δ18O record63 (9-point running average). c δ13CFA in core 91GGC from Tarakan Delta offshore Northeast Borneo57, Δ13CBC−CO2 from core CG18 (this study). The chronology of core CG18 has been established by 13 accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C ages indicated by black pentagrams below. d δ13C in guano deposits from Niah cave in Northwest Borneo58. e Cave temperature record from Northwest Borneo52. Error bars are two standard errors of the mean. f SON insolation (average Agu. 21-Nov. 20 insolation strength) at latitude 4°N65. g Simulated El Niño/La Niña occurrence ratios per 100 years11,61 (5-point running average), ENSO variability estimated from application of the Zebiak–Cane–coupled ocean–atmosphere model forced by changing orbital parameters24. h Mg/Ca-based sea surface temperature (SST) stacks in the western Pacific warm pool (WPWP), central equatorial Pacific (CEP) and eastern equatorial Pacific (EEP) computed using a sliding rectangular window of 1 kyr width by STATNARY 1.215,53,64. i 231Pa/230Th from the Bermuda Rise67. j Atmospheric CO2 concentrations55,56, the North Hemisphere (solid) and the South Hemisphere (dashed) ice volume converted from ICE-5G reconstruction13 (as equivalent sea-level rise). Vertical pink shadings indicate BA and DO interstadials.

Our Δ13CBC−CO2 records from core CG18 closely match n-alkanoic acid δ13Cwax records in core 91GGC from Tarakan Delta offshore Northeast (NE) Borneo57 (Fig. 3c). Both show marked 13C-enrichment during the B–A compared to Holocene values, indicating coherent vegetation and hydrological changes across NW and NE Borneo. While core 91GGC experienced greater enrichment over the last 4.0 kyr, likely due to local factors like human clearance57. The larger vegetation source areas in marine δ13C records may represent overall watershed conditions. In contrast, δ13C records of insect cuticles in Niah cave guano sediments reflect localized changes around the cave58. Considering the dating uncertainties of radiocarbon dates, the δ13Cguano enrichment in Niah cave is ~1.3 kyr later than marine Δ13CBC−CO2 records from the NW Borneo trough (Fig. 3d), which show increased δ13C at ~13.4 ka, suggesting forest retreat from the continental shelf to the cave area over ~1.3 kyr due to increased dry season water stress. Taken together, enriched δ13C values across NW and NE Borneo during the B–A support regionally drier and/or more seasonal aridity conditions, resulting in more open-canopy C3 forests in the Borneo lowlands.

Driving mechanisms of hydroclimate changes during the B–A interstadial

Comparing our Δ13CBC−CO2 records with other paleoclimate records from the broader Asian-Pacific region (Supplementary Table 1) enhances understanding of the main driving mechanisms influencing the region’s hydroclimate. The δ18Osw record, reflecting salinity variation in the ocean surface layer, integrates large-scale hydrological changes including rainfall, evaporation, advection, and upwelling of water masses59,60,61. Therefore, we exclude western Pacific δ18Osw data from regional comparisons in this study. Nearly all paleoclimate records from the tropical western Pacific, between 15°N and 20°S, and east of 110°E, show enhanced aridity and/or pronounced seasonal drying during the B–A period (Fig. 1a), comparable to the simulation results (Fig. 4a, c). One possible scenario is that the ITCZ shifted sufficiently north to remain north of northern Borneo during most of the year, affecting both water vapor transport and regional rainfall amount. However, as previously noted, the amplitude of this event was superseded by numerous additional D–O interstadial events62,63 (Fig. 3a, b), which do not correspond to large-scale droughts and/or seasonal aridity in the western Pacific. In fact, our Δ13CBC−CO2 records indicate that the mean ITCZ position seemly remained at the same latitude as today throughout D–O interstadials 2, 3, and 4, when Borneo was within the western Pacific deep tropical convection year-round (Supplementary Fig. 5), contrasting with B–A northward shifts. Collectively, these inconsistent patterns argue against shifts in the mean position of the ITCZ as the only or main cause of B–A hydroclimate changes across the tropical Asian-Pacific region.

a TRACE-ALL full-forcing simulations of BA–pre-industrial (PI) annual mean precipitation anomalies with concurrent low-level wind variability. b TRACE-ICE simulations of BA–PI annual mean precipitation anomalies with concurrent low-level wind variability. c TRACE-ALL full-forcing simulations of BA–PI boreal summer (JJA) mean precipitation anomalies with concurrent low-level wind variability. d TRACE-ICE simulations of BA–PI boreal summer (JJA) mean precipitation anomalies with concurrent low-level wind variability. The magenta dot indicates the location of core CG18. Transient simulations employ 500-year time slices from the BA (14.5–14.0 ka) and PI (1.0–0.5 ka) periods.

An alternative explanation involves a major reorganization or longitudinal shift in the Pacific Walker Circulation, resembling ENSO-like behavior in the Pacific ocean–atmosphere system. Paleo-proxy records and modeling results show that B–A rainfall anomalies across the tropical Asian-Pacific region closely mirror modern rainfall patterns during the strong 2015/2016 El Niño (Figs. 1a and 4a, c). Modeling experiments further simulated drier western Pacific conditions during the Allerød period, analogous to extreme modern El Niño events16. Additionally, both TRACE-simulated El Niño/La Niña occurrence ratios11,61 (Fig. 3g) and TRACE-ICE simulations13 (ice-sheet forcing only) indicate prevalent El Niño-like conditions during the B–A. The SST stack based on published planktonic foraminiferal Mg/Ca records from 71 Pacific sites (Fig. 1c) reveals distinct patterns during the B–A: central equatorial Pacific (CEP) warming contrasted with eastern equatorial Pacific (EEP) weak cooling, while WPWP remained stable15,53,64. Concurrently, the scarce δ18Osw–iv records from the CEP—which serve as hydroclimate proxies covering the B–A interval—indicate the prevalence of humid conditions across this data-sparse region (Supplementary Fig. 6). This spatial temperature-rainfall anomaly pattern—characteristic of modern central Pacific El Niño (CP El Niño)—is robustly simulated in TRACE-ICE13. Taken together, these lines of evidence demonstrate that a persistent CP-ENSO-like state dominated the equatorial Pacific during the B–A, driving persistent drought and/or seasonal aridity across the western Pacific region.

According to our Δ13CBC−CO2 records, the B–A is an interval of anomalously low convective activity in the western Pacific relative to D–O interstadials 2, 3, and 4. This convective minimum across the western Pacific corresponds to a minimum in boreal fall September–October–November (SON) insolation at 4°N65 (Fig. 3f). Early experiments using the Zebiak–Cane intermediate coupled ocean–atmosphere model suggested that ENSO variance may be sensitive to boreal fall insolation, due to zonally asymmetric atmospheric heating over the tropical Pacific in late boreal summer/early fall66. Enhanced El Niño variability during insolation minima could subsequently shift convective centers. However, the investigation with the Zebiak–Cane model is forced only by changing orbital parameters and excludes climatic boundary conditions such as atmospheric CO2 changes or continental ice-sheet changes. This may explain these earlier model results of increased ENSO variability across the whole last deglaciation24 (Fig. 3g), while a more rapid increase trend during the B–A is found in this study. This discrepancy possibly indicates that ENSO variability during this time is not triggered alone by precessional insolation forcing. TRACE simulations support this finding: full-forcing runs show indistinct ENSO changes, while TRACE-ICE (ice-sheet forced only) captures enhanced variability under B–A-like conditions11. Proxy reconstructions17 similarly show weak signals, likely reflecting eastern-biased core locations and persistent CP-ENSO-like states.

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations remained stable55 (~226–239 ppm; Fig. 3j), and their warming influence was muted during the B–A by concurrent stability or cooling in WPWP/EEP SST stack53 (Fig. 3h) and Borneo land temperatures52 (Fig. 3e). The AMOC cannot be a primary driver: similar-amplitude AMOC variations in prior D–O interstadials67 (Fig. 3i) lack temporal correspondence with enhanced ENSO variability. Consequently, the abrupt amplification of ENSO variability during the B–A aligns with Laurentide ice-sheet retreat past a critical threshold (e.g., meltwater pulse 1 A)68,69, as simulated in the transient model13. During the B–A, a threshold response at intermediate ice-sheet heights induces two key processes: (1) a northward shift of the NH westerly jet stream70,71,72, generating anomalous easterly winds that extend to the NE tropical Pacific. These winds are amplified by wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback73 and propagate equatorward. (2) Rapid sea-ice expansion over the North Atlantic and North Pacific subpolar regions drives regional cooling72,74,75. This cooling may initiate subtropical North Pacific anomalies that subsequently influence the tropics via WES feedback. Both processes induce pronounced cooling north of the equator in the eastern Pacific, reducing the north–south cross-equatorial SST gradient and weakening the region’s annual cycle13. The attenuated annual cycle may then intensify ENSO activity through the nonlinear mechanism of frequency entrainment11,76,77,78—ENSO may transition from its natural oscillatory mode to a more annual frequency when the annual cycle is sufficiently strong, thereby reducing interannual variability. Conversely, weakening the annual cycle relaxes this phase locking, enabling greater ENSO-driven interannual variability. Given the asymmetric intensity distribution of ENSO events, where El Niño episodes are typically stronger than La Niña, increased ENSO variability tends to favor El Niño-like climatic conditions.

Figure 4 reveals divergent annual and boreal summer (JJA) mean precipitation responses over the western Pacific between TRACE full-forcing experiments and TRACE-ICE simulations, attributable to forcing differences during the B–A. These discrepancies indicate that while NH ice-sheet retreat initiated CP El Niño-like conditions in the tropical eastern Pacific, it alone cannot account for the widespread western Pacific droughts and/or seasonal aridity observed during the B–A. TRACE-ICE’s idealized ice-sheet forcing represents an oversimplification compared to TRACE’s comprehensive drivers, potentially explaining the mismatch with Fig. 1 proxy reconstructions. As previously noted, the limited thermal forcing52,53 from atmospheric CO₂55 (<15 ppm increase) during this transition likely played a negligible role in western Pacific hydroclimate reorganization. Instead, NH ice-sheet retreat beyond a critical threshold, concurrent with a boreal autumn (SON) insolation minimum65 (Fig. 3f) and Southern Hemisphere (SH) cooling associated with AMOC variability79 (e.g., the Antarctic cold reversal80), collectively explain the persistent droughts and/or seasonal aridity across the western Pacific during the B–A (Fig. 5).

During the last deglaciation, boreal fall September–October–November (SON) insolation minima caused uniform cooling of the tropical Pacific atmosphere, generating westerly anomalies over the western equatorial Pacific (WEP). By the onset of the B–A, Northern Hemisphere (NH) ice-sheet retreat passed a critical threshold, inducing eastern equatorial Pacific (EEP) cooling and central equatorial Pacific (CEP) warming, which triggered central Pacific (CP) El Niño-like conditions. This shifted the ascending branch of the Pacific Walker Circulation toward the CEP, causing humid conditions there and further strengthening westerly anomalies—establishing a positive feedback that enhanced CP El Niño. Combined with Southern Hemisphere (SH) forcing, this led to persistent dryness and/or seasonal aridity in the western Pacific, ultimately promoting the retreat of C3 vegetation and expansion of open-canopy lowland C3 ecosystems in Borneo. Note: core CG18 was collected from the Northwest Borneo trough in the southern South China Sea (SCS).

As shown in Fig. 5, both ENSO and SH forcings drove western Pacific aridity during the B–A. During the last deglaciation (~19–11 ka), uniform cooling of the tropical equatorial Pacific surface atmosphere—driven by SON insolation minima—generated westerly anomalies over the western equatorial Pacific (WEP)66 (Figs. 4a and 5). By the onset of the B–A, NH ice-sheet retreat beyond a critical threshold induced EEP cooling and CEP warming, triggering CP El Niño-like conditions. This shifted the Pacific Walker Circulation’s ascending branch toward the CEP, further intensifying the westerly anomalies over the WEP and establishing a positive feedback loop that enhanced CP El Niño development. Regional cooling in the western Pacific52 (Fig. 3e), potentially linked to SH forcings (e.g., northward displacement of the SH westerlies and associated atmospheric reorganization81), intensified subsidence while suppressing deep convection, thereby causing aridification (Fig. 5). This atmospheric adjustment persistently contracted the ITCZ northward over South China and Taiwan Island, markedly intensifying precipitation gradients82,83 (Fig. 1a).

Additionally, large continental ice sheets during the glacial period tend to suppress ENSO variability, as coral proxy results indicate a relatively weak ENSO during times when ENSO likelihood is stronger than today due to a precession-driven minimum in SON insolation24. Ice-sheet melt in high northern latitudes likely initiated weak glacial ENSO variability. Once a critical threshold (e.g., ice thickness) is surpassed during the glacial–interglacial transition, changes in seasonal insolation appear to be the dominant factor influencing western Pacific precipitation during interglacial periods84,85. This influence might have been even more pronounced during the Holocene11,14,18,21,23. Future validation of this hypothesis will require integration of multidisciplinary geological records and modeling datasets, as well as the development of new proxy reconstructions. Simultaneously, as SON insolation diminishes towards its seasonal minimum nowadays (Fig. 3f), our study may offer valuable insights into future changes in the zonal SST gradients across the tropical Pacific—a hotly debated issue marked by ongoing discrepancies between observational records and modeling results29. Specifically, observational records suggest a “La Niña-like” strengthening of the zonal SST gradient over the past century, whereas most climate model simulations project an “El Niño-like” weakening in the future.

In summary, this study integrates multiple proxies (XRF elemental ratios, magnetic susceptibility, BC δ13C in core CG18) with transient climate simulations, revealing strong teleconnections between tropical western Pacific circulation and high-latitude NH processes throughout stadial and interstadial phases of D–O cycles. Building on earlier work9,13, we identify two distinct high-latitude forcing mechanisms governing tropical western Pacific variability during D–O oscillations: (1) hemispheric thermal gradients modulating tropical moisture budgets, and (2) ice-sheet topographic forcing restructuring Pacific Walker Circulation patterns—a tipping point only reached when NH ice sheets shrank past critical thresholds during the glacial–interglacial transition. These findings highlight the necessity of incorporating cryosphere–tropical teleconnections into climate models when simulating D–O cycles. Enhanced representation of these coupled processes will be crucial for developing more accurate predictions of future hydrological changes and ENSO behavior across IPWP regions.

Methods

Core locations and age models

Gravity core CG18 (114.4°E, 6.4°N; total length 650 cm) was retrieved in 2012 from the NW Borneo trough during the SCS survey cruise aboard the R/V Ke Xue Yi Hao (Science I), a research vessel affiliated with the Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOCAS). The coring site is situated on the lower continental slope at a water depth of 2139 m, approximately 180 km seaward of the modern NW Borneo coastline. During the LGM (LGM: 24–18 ka)86, when sea level dropped to ~120 m below present, this location remained ~100 km from the paleo-coastline. The substantially reduced distance to river mouths during this lowstand period enhanced terrigenous sediment supply to the site, making it an optimal archive for studying glacial–interglacial sedimentary evolution.

The chronostratigraphic framework of core CG18 was constructed through accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dating of mixed planktonic foraminifera9. Samples exceeding 8 mg, collected from 13 horizons within the core, were analyzed at Beta Analytic Inc. (Miami, USA). The measured 14C ages were converted to calendar ages using the Marine20 calibration curve87, incorporating a regional marine reservoir correction of 388 ± 34 14C years. This correction was derived from published values at three proximal locations88,89,90. The age-depth model, generated with the Clam software (v2.3.2)91, provides calendar ages with 95% confidence intervals (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

The upper section of core CG18 exhibits a yellowish-brown coloration that gradually darkens with depth, transitioning to a bluish to dark gray hue in the lower part. Above 240 cm, the core is predominantly composed of silty clay, which is fine-textured, cohesive, and relatively homogeneous in lithology. Between 240 and 450 cm, the sediment consists mainly of clayey silt, characterized by reduced clay content, a slight increase in silt fraction, and lower water content. Black organic-rich patches and bands are frequently developed within certain intervals of this zone, while the lithology remains relatively uniform. At the base of the core, between 442 and 444 cm, two distinct sandy laminations are observed, each approximately 1 cm thick. This study focuses on the upper 450 cm of the core, spanning approximately the last 30 ka. Sedimentation rates (cm kyr−1), calculated using Clam91, exhibit temporal variability: rates remained below 15 cm kyr−1 after 13 ka, peaked at ~22 cm kyr−1 during Heinrich Stadial 1 (HS1: 17.5–14.7 ka)92 and ~24 cm kyr−1 during the LGM, and declined to <10 cm kyr−1 by 30 ka (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

XRF scanning elemental abundance

Elemental abundances (in counts per second) in core CG18 were measured by XRF core scanning at ~1 mm interval using the Itrax XRF core scanner, with 20 s count times, 30 kV X-ray voltage, and an X-ray current of 40–55 mA.

Black carbon analysis

BC in core CG18 sediments was isolated following the chemical oxidation protocol93. Approximately 1–2 g dried bulk sediments were sequentially treated with 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) to remove carbonates, followed by hydrofluoric acid (HF, 2 M) and HCl (1 M) to dissolve silicate minerals and refractory oxides. Residual organic matter and kerogen were then oxidized using a potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution (0.1 M K2Cr2O7 in 2 M H2SO4). After each chemical treatment, samples were centrifuged and rinsed with ultrapure water until neutrality. The final residue, operationally defined as BC34,35, was retained for isotopic analysis.

Carbon isotopic compositions (δ13C) of BC were determined using a Thermo FLASH EA 1112 elemental analyzer coupled to a MAT 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the IOCAS. Values are reported in standard δ notation relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite reference. To ensure analytical quality control, duplicate measurements of certified reference materials (including USGS-40 with δ13C = −26.39‰, USGS-64 at δ13C = −40.81‰, IAEA-600 showing δ13C = −27.771‰, and Urea 2a# with δ13C = −9.14‰) were systematically conducted alongside replicate analyses inserted after every ten experimental samples, achieving a measurement precision better than ±0.1‰ for δ13C values.

TRACE and TRACE single-forcing simulations

To investigate hydroclimate evolution over the last deglaciation in the study region, we utilized the transient climate evolution of the past 21,000 years (TRACE-21 ka) experiment11,94,95, a comprehensive transient simulation conducted with the Community Climate System Model version 396. The model is a fully coupled general circulation model incorporating atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land surface components, with a nominal horizontal resolution of T31 (~3.75°) for the atmosphere and land, and approximately 3° (higher in the low latitudes) resolution for the ocean and sea ice components.

TRACE simulation spans from the LGM (21 ka) to the present day and includes time-varying boundary conditions and external forcings of (1) greenhouse gas concentrations (CO2, CH4, N2O) derived from ice core records, (2) orbital parameters following Milankovitch cycles, (3) continental ice-sheet extent and topography from the ICE-5G reconstruction, (4) prescribed freshwater fluxes representing meltwater discharge from retreating ice sheets. To isolate the contributions of individual forcings, a set of single-forcing sensitivity simulations was conducted, corresponding to four types of external forcings: TRACE-GHG, TRACE-ORB, TRACE-ICE, and TRACE-MWF. While these experiments collectively allow assessment of the relative roles of different climate forcings, the analysis and discussion in the manuscript focus specifically on the TRACE-ICE simulation in order to elucidate the role of ice-sheet forcing.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17637184. The modern observed GPCP V3.2, ONI, WOA 2023 and TRMM datasets are available at https://measures.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/opendap/GPCP/GPCPDAY.3.2/, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/world-ocean-atlas-2023/ and https://disc2.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/opendap/TRMM_L3/TRMM_3B43.7/, respectively.

Code availability

TRACE and TRACE single-forcing output can be accessed from the Earth System Grid at https://www.earthsystemgrid.org/project/trace.html.

References

Dansgaard, W. et al. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364, 218–220 (1993).

Heinrich, H. Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130,000 years. Quat. Res. 29, 142–152 (1988).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Increasing Australian–Indonesian monsoon rainfall linked to early Holocene sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci. 2, 636–639 (2009).

Mohtadi, M. et al. Glacial to Holocene swings of the Australian–Indonesian monsoon. Nat. Geosci. 4, 540–544 (2011).

Ayliffe, L. K. et al. Rapid interhemispheric climate links via the Australasian monsoon during the last deglaciation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2908 (2013).

Denniston, R. F. et al. North Atlantic forcing of millennial-scale Indo-Australian monsoon dynamics during the last glacial period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 72, 159–168 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. A contracting intertropical convergence zone during the early Heinrich stadial 1. Nat. Commun. 14, 4695 (2023).

Kuhnt, W. et al. Southern hemisphere control on Australian monsoon variability during the late deglaciation and Holocene. Nat. Commun. 6, 5916 (2015).

Huang, J. et al. Rapid climate links between high northern latitudes and tropical southeast Asia over the last 40 ka. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL107171 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Evolution and forcing mechanisms of El Niño over the past 21,000 years. Nature 515, 550–553 (2014).

Emile-Geay, J. et al. Links between tropical Pacific seasonal, interannual and orbital variability during the Holocene. Nat. Geosci. 9, 168–173 (2016).

Lu, Z., Liu, Z. & Zhu, J. Abrupt intensification of ENSO forced by deglacial ice-sheet retreat in CCSM3. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1877–1891 (2016).

Lu, Z. et al. Increased frequency of multi-year El Niño–Southern Oscillation events across the Holocene. Nat. Geosci. 18, 337–343 (2025).

Rustic, G. T., Polissar, P. J., Ravelo, A. C. & White, S. M. Modulation of late Pleistocene ENSO strength by the tropical Pacific thermocline. Nat. Commun. 11, 5377 (2020).

Hällberg, P. L., Schenk, F., Yamoah, K. A., Kuang, X. & Smittenberg, R. H. Seasonal aridity in the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool during the late glacial driven by El Niño-like conditions. Clim. Past 18, 1655–1674 (2022).

Glaubke, R. H. et al. An inconsistent ENSO response to northern hemisphere stadials over the last deglaciation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107634 (2024).

Moy, C. M., Seltzer, G. O., Rodbell, D. T. & Anderson, D. M. Variability of El Niño/Southern Oscillation activity at millennial timescales during the Holocene epoch. Nature 420, 162–165 (2002).

Koutavas, A. & Joanides, S. El Niño–Southern Oscillation extrema in the Holocene and last glacial maximum. Paleoceanography 27, PA 4208 (2012).

Cobb, K. M. et al. Highly variable El Niño–Southern Oscillation throughout the Holocene. Science 339, 67–70 (2013).

Carré, M. et al. Holocene history of ENSO variance and asymmetry in the eastern tropical Pacific. Science 345, 1045–1048 (2014).

Ford, H. L., Ravelo, A. C. & Polissar, P. J. Reduced El Niño–Southern Oscillation during the last glacial maximum. Science 347, 255–258 (2015).

White, S. M., Ravelo, A. C. & Polissar, P. J. Dampened El Niño in the early and mid-Holocene due to insolation-forced warming/deepening of the thermocline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 316–326 (2018).

Tudhope, A. W. et al. Variability in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation through a glacial-interglacial cycle. Science 291, 1511–1517 (2001).

Sadekov, A. Y. et al. Palaeoclimate reconstructions reveal a strong link between El Niño-Southern Oscillation and Tropical Pacific mean state. Nat. Commun. 4, 2692 (2013).

Driscoll, R. et al. ENSO reconstructions over the past 60 ka using giant clams (Tridacna sp.) from Papua New Guinea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6819–6825 (2014).

Menviel, L. C., Skinner, L. C., Tarasov, L. & Tzedakis, P. C. An ice–climate oscillatory framework for Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 677–693 (2020).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the last glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 14–28 (2014).

Lee, S. et al. On the future zonal contrasts of equatorial Pacific climate: perspectives from observations, simulations, and theories. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 82 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Climatic and tectonic controls on weathering in south China and Indochina Peninsula: clay mineralogical and geochemical investigations from the Pearl, Red, and Mekong drainage basins. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8, Q05005 (2007).

Wei, G. et al. Nd, Sr isotopes and elemental geochemistry of surface sediments from the South China Sea: implications for provenance tracing. Mar. Geol. 319, 21–34 (2012).

Huang, J. et al. Sediment distribution and dispersal in the southern South China Sea: evidence from clay minerals and magnetic properties. Mar. Geol. 439, 106560 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Climatic and tectonic controls on chemical weathering in tropical southeast Asia (Malay Peninsula, Borneo, and Sumatra). Chem. Geol. 291, 1–12 (2012).

Coppola, A. I. et al. The black carbon cycle and its role in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 516–532 (2022).

Shen, X. et al. Increased seasonality and aridity drove the C4 plant expansion in central Asia since the Miocene–Pliocene boundary. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 502, 74–83 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Expansion of C4 plants in south China and evolution of east Asian monsoon since 35 Ma: black carbon records in the northern South China Sea. Glob. Planet. Change 223, 104079 (2023).

Bird, M. I. & Gröcke, D. R. Determination of the abundance and carbon isotope composition of elemental carbon in sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3413–3423 (1997).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature 389, 153–158 (1997).

Schefuß, E., Schouten, S. & Schneider, R. R. Climatic controls on central African hydrology during the past 20,000 years. Nature 437, 1003–1006 (2005).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Eggleston, S., Schmitt, J., Bereiter, B., Schneider, R. & Fischer, H. Evolution of the stable carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO2 over the last glacial cycle. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 31, 434–452 (2016).

Hare, V. J., Loftus, E., Jeffrey, A. & Ramsey, C. B. Atmospheric CO2 effect on stable carbon isotope composition of terrestrial fossil archives. Nat. Commun. 9, 252 (2018).

Farquhar, G. D., Ehleringer, J. R. & Hubick, K. T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 40, 503–537 (1989).

Jia, G., Peng, P. A., Zhao, Q. & Jian, Z. Changes in terrestrial ecosystem since 30 Ma in East Asia: stable isotope evidence from black carbon in the South China Sea. Geology 31, 1093–1096 (2003).

Sun, Y. et al. Influence of Atlantic meridional overturning circulation on the East Asian winter monsoon. Nat. Geosci. 5, 46–49 (2012).

Chen, T. C., Tsay, J. D., Matsumoto, J. & Alpert, J. Development and formation mechanism of the Southeast Asian winter heavy rainfall events around the South China Sea. Part I: formation and propagation of cold surge vortex. J. Clim. 28, 1417–1443 (2015).

Lim, S. Y., Marzin, C., Xavier, P., Chang, C. P. & Timbal, B. Impacts of boreal winter monsoon cold surges and the interaction with MJO on Southeast Asia rainfall. J. Clim. 30, 4267–4281 (2017).

Tangang, F. T. et al. On the roles of the northeast cold surge, the Borneo vortex, the Madden-Julian Oscillation, and the Indian Ocean dipole during the extreme 2006/2007 flood in southern Peninsular Malaysia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L14S07 (2008).

Yang, Z., Lei, Y., Rosenthal, Y., Li, T. & Jian, Z. Late Pleistocene climate induced changes in paleo-vegetation in Borneo: possible implications to human divergence. Quat. Sci. Rev. 267, 107109 (2021).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Hendrizan, M., Kuhnt, W. & Holbourn, A. Variability of Indonesian throughflow and Borneo runoff during the last 14 kyr. Paleoceanography 32, 1054–1069 (2017).

Løland, M. H. et al. Evolution of tropical land temperature across the last glacial termination. Nat. Commun. 13, 5158 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Thermal coupling of the Indo-Pacific warm pool and southern ocean over the past 30,000 years. Nat. Commun. 13, 5457 (2022).

Ehleringer, J. R., Cerling, T. E. & Helliker, B. R. C4 photosynthesis, atmospheric CO2, and climate. Oecologia 112, 285–299 (1997).

Monnin, E. et al. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last glacial termination. Science 291, 112–114 (2001).

Ahn, J. & Brook, E. J. Siple dome ice reveals two modes of millennial CO2 change during the last ice age. Nat. Commun. 5, 3723 (2014).

Dubois, N. et al. Indonesian vegetation response to changes in rainfall seasonality over the past 25,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 7, 513–517 (2014).

Wurster, C. M. et al. Forest contraction in north equatorial Southeast Asia during the last glacial period. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15508–15511 (2010).

Fraser, N. et al. Precipitation variability within the West Pacific warm pool over the past 120 ka: evidence from the Davao Gulf, southern Philippines. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 29, 1094–1110 (2014).

Gibbons, F. T. et al. Deglacial δ18O and hydrologic variability in the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 387, 240–251 (2014).

Xiong, Z. et al. Rapid precipitation changes in the tropical West Pacific linked to north Atlantic climate forcing during the last deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 197, 288–306 (2018).

NGRIP Members High-resolution record of northern hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial period. Nature 431, 147–151 (2004).

WAIS Divide Project Members Onset of deglacial warming in West Antarctica driven by local orbital forcing. Nature 500, 440–444 (2013).

Monteagudo, M. M., Lynch-Stieglitz, J., Marchitto, T. M. & Schmidt, M. W. Central equatorial Pacific cooling during the last glacial maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL088592 (2021).

Laskar, J. et al. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth. Astron. Astrophys. 428, 261–285 (2004).

Clement, A. C., Seager, R. & Cane, M. A. Orbital controls on the El Nino/Southern Oscillation and the tropical climate. Paleoceanography 14, 441–456 (1999).

Henry, L. G. et al. North Atlantic Ocean circulation and abrupt climate change during the last glaciation. Science 353, 470–474 (2016).

Carlson, A. E. & Clark, P. U. Ice sheet sources of sea level rise and freshwater discharge during the last deglaciation. Rev. Geophys. 50, RG4007 (2012).

Deschamps, P. et al. Ice-sheet collapse and sea-level rise at the Bølling warming 14,600 years ago. Nature 483, 559–564 (2012).

Eisenman, I., Bitz, C. M. & Tziperman, E. Rain driven by receding ice sheets as a cause of past climate change. Paleoceanography 24, PA 4209 (2009).

Lee, S. Y., Chiang, J. C. & Chang, P. Tropical Pacific response to continental ice sheet topography. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2429–2446 (2015).

Zhang, X., Lohmann, G., Knorr, G. & Purcell, C. Abrupt glacial climate shifts controlled by ice sheet changes. Nature 512, 290–294 (2014).

Xie, S. P. & Philander, S. G. H. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus A 46, 340–350 (1994).

Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Brady, E. C., Shin, S. I., Liu, Z. & Shields, C. Modeling El Niño and its tropical teleconnections during the last glacial-interglacial cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2198 (2003).

Zhu, J., Liu, Z., Zhang, X., Eisenman, I. & Liu, W. Linear weakening of the AMOC in response to receding glacial ice sheets in CCSM3. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6252–6258 (2014).

Chang, P., Wang, B., Li, T. & Ji, L. Interactions between the seasonal cycle and the Southern Oscillation–frequency entrainment and chaos in a coupled ocean-atmosphere model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 2817–2820 (1994).

Liu, Z. A simple model study of ENSO suppression by external periodic forcing. J. Clim. 15, 1088–1098 (2002).

Timmermann, A., Lorenz, S. J., An, S. I., Clement, A. & Xie, S. P. The effect of orbital forcing on the mean climate and variability of the tropical Pacific. J. Clim. 20, 4147–4159 (2007).

Shakun, J. D. et al. Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nature 484, 49–54 (2012).

Pedro, J. B. et al. The spatial extent and dynamics of the Antarctic cold reversal. Nat. Geosci. 9, 51–55 (2016).

Fletcher, M. S. et al. Northward shift of the southern westerlies during the Antarctic cold reversal. Quat. Sci. Rev. 271, 107189 (2021).

Lu, F. et al. Tipping point-induced abrupt shifts in East Asian hydroclimate since the last glacial maximum. Nat. Commun. 16, 477 (2025).

Ding, X. et al. Lacustrine record of centennial-and millennial-scale rainfall variability of the East Asian summer monsoon during the last deglaciation: multi-proxy evidence from Taiwan. Paleogeogr. Paleoclimatol. Paleoecol. 450, 38–49 (2016).

Carolin, S. A. et al. Northern Borneo stalagmite records reveal West Pacific hydroclimate across MIS 5 and 6. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 439, 182–193 (2016).

Windler, G., Tierney, J. E. & Anchukaitis, K. J. Glacial-interglacial shifts dominate tropical Indo-Pacific hydroclimate during the late Pleistocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093339 (2021).

Mix, A. C., Bard, E. & Schneider, R. Environmental processes of the ice age: land, oceans, glaciers (EPILOG). Quat. Sci. Rev. 20, 627–657 (2001).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20—the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Southon, J., Kashgarian, M., Fontugne, M., Metivier, B. & Yim, W. W. Marine reservoir corrections for the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. Radiocarbon 44, 167–180 (2002).

Dang, P. X., Mitsuguchi, T., Kitagawa, H., Shibata, Y. & Kobayashi, T. Marine reservoir correction in the south of Vietnam estimated from an annually-banded coral. Radiocarbon 46, 657–660 (2004).

Bolton, A., Goodkin, N. F., Druffel, E. R., Griffin, S. & Murty, S. A. Upwelling of Pacific intermediate water in the South China Sea revealed by coral radiocarbon record. Radiocarbon 58, 37–53 (2016).

Blaauw, M. Methods and code for “classical” age-modelling of radiocarbon sequences. Quat. Geochronol. 5, 512–518 (2010).

Denton, G. H., Broecker, W. S. & Alley, R. B. The mystery interval 17.5 to 14.5 kyrs ago. PAGES News 14, 14–16 (2006).

Lim, B. & Cachier, H. Determination of black carbon by chemical oxidation and thermal treatment in recent marine and lake sediments and Cretaceous-tertiary clays. Chem. Geol. 131, 143–154 (1996).

He, F. Simulating transient climate evolution of the last deglaciation with CCSM3 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011).

Liu, Z. et al. Transient simulation of last deglaciation with a new mechanism for Bølling–Allerød warming. Science 325, 310–314 (2009).

Collins, W. D. et al. The Community Climate System Model version 3 (CCSM3). J. Clim. 19, 2122–2143 (2006).

Huffman, G. J. et al. The new version 3.2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly and daily precipitation products. J. Clim. 36, 7635–7655 (2023).

Locarnini, R. A. et al. World ocean atlas 2023, volume 1: temperature. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 89, 52 (2024).

Partin, J. W., Cobb, K. M., Adkins, J. F., Clark, B. & Fernandez, D. P. Millennial-scale trends in West Pacific warm pool hydrology since the last glacial maximum. Nature 449, 452–455 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere appreciation to the crew of R/V KE XUE YI HAO for their professional support during the 2012 South China Sea (SCS) survey cruise. Special thanks are extended to Huan Yu, Jin Liu, and Wenjun Jiao for their valuable experimental assistance. We also acknowledge Yuchen Sun for helpful discussions during manuscript preparation and Hualong Jin for providing the base map for Fig. 5. This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42476054 and 42376053), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF0800503), and the Laoshan Laboratory Fund (LSKJ202204205). Z.L. acknowledges the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet (grant no. 2022-03617) and the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS) at Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. initiated this study and performed lab measurements and data analysis. T.L. and A.L. organized the cruise and sample collection. F.C. and H.S. helped collect the core materials. Z.L. generated and analyzed the modeling data. J.H. and Z.Y. were responsible for data collection and/or synthesis. S.Z. collected SST and δ18Osw–iv data. S.W., Z.L., S.Z., X.M., and Z.Y. contributed to the discussion and commented on the paper. J.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from T.L., A.L., S.W., F.C., Z.L., S.Z., H.S., X.M., and Z.Y. to the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Ignacio Jara and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Yama Dixit, Alice Drinkwater, and Alienor Lavergne. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Yang, Z., Lu, Z. et al. Persistent El Niño-like conditions over the western Pacific during the Bølling–Allerød interstadial. Commun Earth Environ 7, 22 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03053-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03053-y