Abstract

Earlier leaf-out enhances spring moisture exchange between land and atmosphere. However, its impact on precipitation intensity remains unclear, hampering dynamic monitoring on water erosion. Here we combined remote sensing, reanalysis data, and coupled land-atmosphere model to address this knowledge gap. Results observed an increasing trend in spring precipitation accompanied by earlier leaf-out across temperate China. The simulations isolated the phenological impacts and attributed it to the enhancement of nonerosive precipitation. The mid-temperate semi-humid region exhibited the largest increase (3.03 ± 3.66 mm) in response to 14-days leaf-out advancement. Conversely, erosive precipitation declined in sparsely vegetated areas (<50% cover), sharpening the heterogeneity of moisture gradient. Elevated convective available potential energy promoted more frequent precipitation, inhibiting the deep moisture accumulation required for erosive downpours. Simulated erosive precipitation also declined in temperate summer and autumn. Findings highlight vegetation’s role in precipitation redistribution beyond surface interception, requiring conservation planning to consider bidirectional vegetation-climate feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global temperatures are projected to rise by 2.8 °C by the end of this century1. Under the warming conditions, atmospheric moisture content will increase by ~16.8–19.6% according to the Clausius-Clapeyron relation2,3. These dynamics will intensify the hydrological cycle, most evidently in the heightened frequency and intensity of precipitation (PRE)4. Long-term observations have revealed a global increase in extreme PRE, a trend projected by climate models to escalate in forthcoming decades5. These changes will initiate a chain of cascading ecological impacts, with the most immediate manifestation being modifications in water erosion characteristics. These modifications involve raindrop impact dislodging soil particles, followed by further detachment, transport, and deposition through surface runoff, ultimately exacerbating water erosion6. Climate change is expected to emerge as a primary driver of intensified water erosion, potentially accounting for more than 50% of increases in some temperate and subtropical regions7,8. While recent advances in eco-hydrological models have begun to incorporate vegetation feedbacks, projecting their impacts on terrestrial water cycles remains an area of active development. These effects alter canopy transpiration, soil moisture evaporation, PRE interception, groundwater recharge, and atmospheric circulation processes, amplifying uncertainties in future PRE patterns9,10,11,12. Consequently, quantifying vegetation-precipitation feedback mechanisms is critical for monitoring, assessing, attributing, and predicting water erosion dynamics.

Vegetation plays a critical role in sustaining soil stabilization13. Plant root systems extend downward, forming networks that anchor soil particles and reinforce soil structural integrity. These networks not only facilitate the formation of erosion-resistant soil matrices, but also reduce soil displacement by enhancing precipitation infiltration, diminishing surface runoff, and intercepting sediments14. On the other hand, vertically stratified vegetation canopies intercept precipitation and attenuate its kinetic energy, thereby mitigating the effects of splash erosion on topsoil15. Studies have shown enhanced productivity in permanent vegetation zones could alleviate or even offset intensifying water erosion, whereas, under extreme rainstorms, bare lands may experience soil loss more than an order of magnitude above normal annual levels16,17,18. Consequently, vegetation restoration is widely recognized as an effective measure for controlling water erosion19,20. For instance, since the implementation of the “Grain for Green” Project on China’s Loess Plateau, 4.1 ×106 ha of degraded land have been converted to natural vegetation, reducing annual sediment loss by 3.6 ×108 t21. Although the stabilizing effects of vegetation on soil erosion are well-documented, a more complete understanding requires integrating the role of vegetation-climate feedbacks. In water erosion assessment and prediction studies, treating PRE as an isolated external forcing while disregarding vegetation’s modulation of hydrological processes may lead to overestimations or underestimations of erosion rates22.

Vegetation is interconnected with the global hydrological cycle, regulating atmospheric moisture content through transpiration and thereby influencing regional PRE23. This transpiration accounts for 64% of global evapotranspiration (ET) and drives its continuous increase under vegetation greening trends24,25. Part of this water vapor returns to the region as PRE, while the rest can be transported by the atmosphere for days or even months, subsequently affecting PRE in nearby downwind or distant regions26,27. In addition, vegetation modulates near-surface wind speed, thermal circulation, and atmospheric stability by altering surface roughness and albedo, thereby modifying the moisture supply via atmospheric circulation28,29. These intertwined processes introduce spatial heterogeneity in PRE responses, resulting in low regional coherence of precipitation changes30. For instance, deforestation in Brazil elevated local PRE but posed risks of large-scale climatic drought31. Moisture convergence has exhibited a dip-rebound trajectory during afforestation efforts over China’s Loess Plateau22. The impacts of vegetation spatial dynamics on PRE have been extensively studied, but the hydrological consequences of temporal variations in vegetation phenology have only recently gained attention.

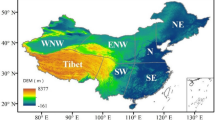

With intensifying climate change, the start of the vegetation growing season has advanced globally by an average of 3.8 days per decade during 1982–200332. Particularly, China has experienced a more pronounced advancement of 5.5 days per decade33. Unlike regional vegetation dynamics, widespread phenological advancement drives large-scale hydrological perturbations33. Such changes have amplified spring evapotranspiration by +0.20 mm·day–¹·yr–¹ in the mid-to-high Northern Hemisphere latitudes25. However, a key challenge lies in elucidating the pathways and mechanisms through which this enhanced atmospheric moisture returns to and influences the land surface. Understanding this mechanism is critical for predicting water erosion, as its changes are primarily driven by PRE intensity rather than total amount9,34. Therefore, we selected China as the study region, where the green-up advance is significant and PRE exhibits high spatial heterogeneity33,35. Based on remote sensing and reanalysis data, we quantified long-term (2001–2020) trends in spring vegetation phenology and PRE, as well as their phase relations across five temperate regions (R1–R5) in China (Supplementary Fig. S1). Then, the modified Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model was employed to simulate changes in erosive and nonerosive PRE response to spring phenological shifts. In addition to isolating the hydrological impacts, this research resolved the causal physical mechanisms linking phenological advancement to hydrological cycle changes. We sought to penetratingly reveal the unbalanced changes between vegetation phenology and hydrologic cycle. These findings shed new light on the interactions between vegetation and PRE, which provided a crucial theoretical foundation for nature-based solutions that curb soil erosion against climate change.

Results

Observing differential shifts in phenology and precipitation patterns

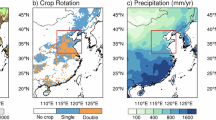

To examine unbalanced shifts between recent phenological changes and PRE dynamics, we first analyze the temporal trends for leaf area index (LAI) and PRE during 2001–2020 spring (from March to May)36 (Fig. 1). Both spring LAI and PRE in temperate China experienced upward non-monotonic trends at regional scale (Fig. 1b–f). Spatially, the upward trend in LAI declined from east to west, with 37.86% of the pixels examined exhibiting a significant increase (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. S2a). However, only 2.24% of the pixels exhibit a significant upward trend in PRE (Supplementary Fig. S2b). The LAI in two semi-humid regions (R1 and R4) increased significantly at rates of 0.032 and 0.055 m²·m–²·decade–¹, far exceeding those of other temperate climate zones (Fig. 1c, e). Because of substantial interannual variability in PRE, temperate climate zones showed no statistically significant linear growth trends (Fig. 1b–f). Monsoon activity, extreme weather, ocean-atmosphere interactions, and other factors contributed to the nonlinear characteristics of spring PRE growth37,38. R4 showed the highest average PRE increase (3.3 mm·decade–¹) from 2000 to 2020, paralleled by non-significant rises in other temperate zones. Based on wavelet coherence analysis, we further observed that these non-stationary time series led LAI during spring, thus revealing a nonlinear trend toward the seasonal advancement of the temperate precipitation cycle (Supplementary Fig. S3). Since both PRE and vegetation cover influence soil water erosion, their combined effects on surface processes need detailed quantification to clarify their ecological consequences.

a LAI and PRE trends averaged over 5° × 5° sample grids in temperate China. Black dots and blocks denote significant LAI and PRE trends (p < 0.05), respectively. Grey pixels indicate areas with stable natural vegetation. b–f Average trends in LAI and PRE in temperate climate zones. R1 Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid region, R2 Mid-Temperate Semi-Humid region, R3 Mid-Temperate Arid region, R4 Warm Temperate Semi-Humid region, R5 Highland Temperate Semi-Arid region. * denotes significant trend (p < 0.05).

Modelling precipitation response driven by earlier leaf-out

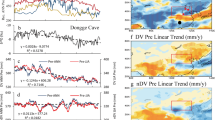

As monthly PRE reanalysis data could not differentiate PRE intensity and quantitatively link its changes to vegetation phenology, WRF model was used to simulate erosive (≥12 mm · d−1) and nonerosive PRE (<12 mm · d−1) changes under various vegetation phenology scenarios (Fig. 2). The Pearson correlation coefficients between WRF-simulated and observed PRE all exceeded 0.7 (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S4). This demonstrated the feasibility of using WRF simulations to isolate the feedback effects of advanced phenology on regional PRE patterns. Driven by 2001–2020 climate data, the multi-year averaged results demonstrated that a 14-day forward shift (Supplementary Fig. S5) of the entire growing season were predicted to elevate spring PRE in temperate zones through increased frequencies of light and moderate rain events (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S6). Specifically, nonerosive PRE increased by 1.14 ± 2.78 mm, 3.03 ± 3.66 mm, and 1.85 ± 3.36 mm in semi-arid and semi-humid regions (i.e., R1, R2, and R4, respectively). In contrast, minimal changes (<1 mm) occurred in the arid interiors of R3, 5, reflecting an amplified response to increasingly stark wet-dry contrasts among climate zones. This mechanism was further evidenced by longitude-dependent patterns in nonerosive PRE (Supplementary Fig. S7). Regional-scale analysis revealed no significant increase in erosive PRE (≥12 mm · d−1) in temperate zones, but intra-climatic redistribution heightened water erosion risks in some areas like central R1,4 and eastern R5 (Fig. 2d). Additionally, temperate phenological advancement was also simulated to trigger PRE redistribution in R6,7, though these non-local effects were not pronounced at regional scales.

a–c Non-erosive ΔPRE, and d–f erosive ΔPRE. ΔPRE represents differences between advanced phenology scenarios and historical baselines, i.e., WRFadvance - WRFhistory. Boxplots in the lower left show ΔPRE variations across climate zones. Areas of statistically significant difference (p < 0.10, two-tailed Student’s t test) are represented by black dots in the spatial plots. R1 Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid region, R2 Mid-Temperate Semi-Humid region, R3 Mid-Temperate Arid region, R4 Warm Temperate Semi-Humid region, R5 Highland Temperate Semi-Arid region, R6 North Subtropical Humid region, R7 Marginal Tropical Humid region.

During summer (from June to August), elevated temperatures broadened the interquartile range of nonerosive ΔPRE across all climate zones compared to spring conditions, which suggests that summer thermal forcing enhanced the intensity and variability of the atmospheric water cycle (Fig. 2b). Notably, regions such as central R1, northern R2, and eastern R5 experienced decreases in nonerosive PRE during summer, despite increases observed in spring. This suggested that vegetation-mediated feedback effects on local moisture recycling are further influenced by monsoon circulation dynamics. Notable reductions in erosive PRE occurred in R1 (−10.07 ± 20.06 mm) and R4 (−7.68 ± 31.78 mm) (Fig. 2e). Conversely, Pacific-adjacent zones R2, 6, 7 exhibited increased water erosion risks, with mean erosive PRE rising by 7.19 ± 27.00 mm, 13.36 ± 45.23 mm, and 16.07 ± 35.85 mm, respectively. However, dense summer canopy interception could partially offset the increased erosive energy. Both inland regions showed limited erosive PRE alterations, but R5 contrasted sharply with R3 through pronounced spatial heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Although our simulation design did not incorporate autumn (from September to November) vegetation dynamics, distinct PRE redistribution patterns were still observed, indicating a time-lag effect of phenological advance on hydrological cycling. Distinct pathways characterized the decline in PRE frequency for R1 and R2: R2 predominantly showed diminished nonerosive PRE, while R1 experienced a more significant reduction in erosive PRE (Fig. 2c, f; Supplementary Fig. S6). R4 exhibited greater spatial heterogeneity in erosive ΔPRE compared to other temperate regions, yet its regional average change was near zero. Similarly, inland regions R3, 5 displayed negligible total ΔPRE. Atmospheric circulation-mediated temperate phenological variations exerted cross-zonal influences, reducing erosive PRE in tropical and subtropical zones. Notably, declining nonerosive PRE in western R6, 7 may limit vegetation growth, potentially increasing surface bareness.

Figure 3 illustrated erosive PRE variations across fractional vegetation coverage (FVC) gradients. The 14-day earlier leaf-out in temperate zones decreased erosive PRE in low-coverage areas (FVC < 50%), with peak average decrease (−61.60 mm) concentrated in 40–45% FVC regions (Fig. 3a). While complex biophysical feedback mechanism in high-FVC regions complicated regional PRE recycling and increased uncertainty, dense vegetation coverage simultaneously mitigated erosion potential by effectively dissipating erosive energy via canopy interception and root stabilization. Both summer and autumn erosive PRE generally declined across coverage gradients, indicating that temperate phenological feedbacks effectively suppress extreme precipitation events (Fig. 3c, e). In contrast, tropical and subtropical zones exhibited increased summer extreme PRE due to non-local phenological influence, particularly in 5–10% coverage areas, where erosive PRE rose by 57.84 mm (Fig. 3d). The north-south divergence in summer erosive PRE changes suggested that phenological feedbacks may shift future erosion hotspots toward tropical and subtropical zones. Spring erosive PRE displayed marked fluctuations around the zero baseline across FVC gradients, reflecting an overall erosion stability in tropical and subtropical zones (Fig. 3b). Autumn patterns in these zones mirrored temperate zones, predominantly showing reduced extreme PRE (Fig. 3b).

Results are shown for (a, c, e) the temperate zone and (b, d, f) the tropical/subtropical zone. The green and blue color schemes correspond to mean PRE values under the WRFadvance and WRFhistory scenarios, respectively. FVC was categorized into 5% increments, where numerical labels indicate the minimum threshold of each coverage class. The error bar denotes one standard error.

Decoding physical mechanisms from phenology-induced precipitation shifts

A process-based physical diagnosis was employed to quantify how advanced vegetation phenology modulates PRE (Methods). These processes are reflected in physical variables, including evapotranspiration (ET), vertically integrated moisture flux (VIMF), convective available potential energy (CAPE), and precipitable water vapor (PWV), which collectively constitute the necessary and sufficient conditions for PRE formation.

Spring phenological advancement exerted significant enhancement on ET within temperate forest ecosystems, particularly in the Khingan Mountains in R2 and the Taihang Mountains in R4 (Fig. 4a). Minimal ET changes observed in grasslands and croplands suggested that spring alterations in local moisture recycling were mainly driven by biophysical feedbacks from forested hydrological systems (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, physiological activity in grasslands and croplands peaked during summer, where phenological shifts further amplified ET (Fig. 4b). For example, R1, which is predominantly covered by croplands, exhibited a mean cumulative summer ET change of 10.12 ± 11.25 mm (Supplementary Table S1). Despite identical autumn vegetation settings in both scenarios, a general reduction in ET processes was observed in the temperate region. This suggested a lag effect in the influence of vegetation phenological changes, where earlier water consumption during the growing season limits the available water during senescence (Fig. 4c). Earlier leaf-out generally enhances spring and summer transpiration, returning more moisture to the atmosphere and, in turn, increasing the contribution of land-surface ET to total PRE (Fig. 2a, d).

a–c Total evapotranspiration (ET), d–f average vertically integrated moisture flux (VIMF), g–i average convective available potential energy (CAPE), and j–l average precipitable water vapor (PWV). Δ represents differences between advanced phenology scenarios and historical baselines, i.e., WRFadvance - WRFhistory. ΔVIMF is the change from the land surface to the 300 hPa pressure level. R1 Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid region, R2 Mid-Temperate Semi-Humid region, R3 Mid-Temperate Arid region, R4 Warm Temperate Semi-Humid region, R5 Highland Temperate Semi-Arid region, R6 North Subtropical Humid region, R7 Marginal Tropical Humid region.

The redistribution of wind speed, humidity, and pressure fields resulting from earlier vegetation phenology also induced changes in VIMF. In spring, ΔVIMF in temperate coastal regions R2, 4 was generally positive, averaging 0.56 and 0.46 kg·m–¹·s–¹, respectively, with the change predominantly directed towards higher latitudes (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table S1). The magnitude of these changes was markedly greater than other climate zones, highlighting enhanced spring moisture-transport capacity in temperate semi-humid regions and increasing the nonlocal moisture supply to regional PRE. In contrast to spring, ΔVIMF in the eastern R4 became negative during summer, and large-scale negative shifts were also observed in the eastern VIMF of R6, 7 (Fig. 4e). The weakening of horizontal moisture transport has become one of the factors contributing to the reduction of both erosive and nonerosive PRE in these coastal regions (Fig. 2b, c). Additionally, the westward ΔVIMF in the eastern R3 explained that the increased PWV in this region was mainly attributable to the moisture transfer from Pacific coastal area (Fig. 4e, k). However, the shortage of CAPE ultimately inhibited PRE formation (Fig. 2b, e and 4h). In autumn, the lagged effects of earlier vegetation phenology manifested as weakened moisture transport in temperate regions and enhanced transport in tropical/subtropical zones (Fig. 4i). These southward moisture shifts subsequently increased the probability of PRE in lower-latitude regions.

CAPE is an indicator of atmospheric stability. During spring, the mean ΔCAPE values in R1, 2, 4 were 11.36, 18.92, and 17.07 J·kg–¹, respectively (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Table S1). These values were higher than those in other climate zones, but substantially lower than the summer differential, suggesting greater energy availability for convective development that facilitates the occurrence of light and moderate precipitation (Fig. 2a). In summer, ΔCAPE further increased across most temperate coastal regions, with the average change in R1 even reaching 121.88 ± 92.97 J·kg–¹ (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Table S1). This signified a considerable buildup of atmospheric convective energy, consequently elevating the probability of short-duration, high-intensity PRE events. However, diminished regional horizontal moisture transport ultimately resulted in less erosive PRE (Figs. 2e and 4e). In autumn, the lagged effect of earlier phenology typically reduced CAPE in the northern temperate zone, thus lowering the likelihood of erosive PRE (Figs. 4l and 2f). Conversely, mean ΔCAPE increased in tropical and subtropical zones, but weakened local ET suppressed the expected intensification of erosive PRE events (Figs. 2f and 4c).

PWV is essential for PRE formation, and its variability is regulated by both local ET and external moisture transport. Following advanced phenology, coastal regions generally exhibited more humid atmospheric conditions in spring, with the mean change in R4 reaching 0.09 ± 0.04 mm (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Table S1). This lowered the vapor pressure deficit, which was conducive to forming nonerosive PRE (Fig. 2a). Summer ΔPWV exhibited a similar spatial pattern, but with a substantially greater magnitude of increase compared to spring. Notably, PWV in inland R3 exhibited an increasing trend in summer. Given the relatively minor changes in local ET, it can be inferred that the increased summer atmospheric humidity was mainly maintained by moisture transported by the monsoon (Fig. 4b, e). Despite generally weakened ET in autumn, PWV in R4 and eastern R6–7 continued to rise (Fig. 4c, f). Conversely, mean PWV in R1 and R2 decreased by 0.04 and 0.06 mm, respectively, indicating insufficient moisture replenishment and a subsequent weakening of moisture cycle processes in mid-high latitude regions (Fig. 2c, f). Importantly, while PWV measures the regional atmospheric moisture content, determining the potential for PRE necessitates analyzing it alongside other physical variables.

Discussion

Precipitation erosivity incorporating vegetation phenology feedback

The IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land underscores that global warming may substantially exacerbate processes driving desertification, land degradation, and food insecurity39. Numerous studies utilizing the revised universal soil loss equation (RUSLE) have projected that increasingly frequent extreme precipitation events in the future will intensify soil water erosion7,8,40. However, this calculation treats crucial factors, including the land cover and PRE erosivity factors, as annual averages, ignoring their inherent seasonal variability and the sub-daily fluctuations in intensity41,42. In fact, peak soil loss often occurs during the early stages of vegetation development, a period characterized by low vegetative soil protection6. Fortunately, the advancing start of growing seasons, driven by global warming, reduces the erosion sensitivity by enhancing land cover during this period32,33. Our results further confirmed the advancing spring leaf-out across temperate China, but this presents new problems. Through the vegetation biological pump, more soil water is transpired into the atmosphere, enhancing PRE sources28,43. The wavelet coherence analysis revealed that the spring PRE variation cycle generally led the vegetation cycle in reaching the seasonal peak across temperate China. This indicated that the advanced phenology also concentrates more PRE within the growing season, potentially heightening the risk of water erosion. To isolate the interactions between vegetation cover and PRE intensity, we advanced the start of vegetation growing seasons by 14 days in the WRF model, and compared subsequent changes in erosive PRE.

Our simulation results showed that earlier vegetation leaf-out increased the frequency of light and moderate PRE events in spring, while negligible change in erosive PRE amounts was observed across seven climate zones. This contrasts with earlier conclusions drawn from remote sensing and reanalysis data, which posited that vegetation greening catalyzes the global water cycle, consequently increasing PRE intensity44. We isolated vegetation feedback from climatic forcing and quantified resultant daily-scale PRE intensity changes. The results demonstrated that advanced vegetation phenology facilitates spring PRE formation, thereby mitigating potential erosive PRE increases from enhanced atmospheric water-holding capacity7,8,40. More importantly, the redistribution effect of advanced phenology on erosive PRE effectively alleviated water erosion pressure in regions with low vegetation cover, as evidenced by statistically significant declines in spring heavy precipitation for areas with FVC < 50%. Similar trends were also observed during summer and autumn. In regions with high vegetation coverage, concomitant with enhanced moist convection and turbulent fluxes23,45, uncertainties surrounding erosive PRE changes under destabilized atmospheric conditions also increase. However, given the interception of PRE energy by canopy foliage and the soil consolidation by root systems, the enhanced PRE erosivity in these regions will be mitigated or even counterbalanced14,15.

Regarding non-local effects, vegetation phenology changes in temperate zones also reconfigure PRE distribution patterns in tropical and subtropical regions. Particularly in summer, moisture transported with atmospheric circulation intensifies erosive PRE in southeastern China. Zan et al. argued that global greening amplified the temporal and spatial disparities in moisture, signifying that wet regions and seasons will become wetter46. Our results further found that advanced vegetation phenology induces the same effect. Despite projected increases in erosive PRE, dense vegetation cover in southeastern China may mitigate this effect. Future erosion hotspots in China are still anticipated to persist primarily on the southwestern plateaus47. Although these regions exhibit high sensitivity to climate-driven warming and moistening trends41,48, our analysis revealed minimal feedback effect of phenological advancement on PRE intensity. In terms of time-lagged impacts, erosive PRE across various vegetation gradients showed a declining trend in temperate zones and other climate regions. This suggests that earlier growing seasons may prematurely deplete soil moisture reserves, consequently suppressing seasonal water cycle intensity in autumn and extensively increasing meteorological drought risks (Supplementary Fig. S8)10,36.

Physical pathways of vegetation phenology influencing hydrological cycles

Although the feedback of vegetation phenology to climate is negligible in the short term, the coupling among vegetation, climate, and hydrological cycles is generally intertwined and exhibits complex dynamics over extended timescales15. The biophysical characteristics of vegetation modulate the hydrological cycle and climate, involving the exchange of water, gases, energy, and momentum43. Therefore, this study utilized the WRF model to deconstruct the impacts of advanced phenology on changes in PRE physical processes (Fig. 5). We found that temperate forests contributed more ET during spring under the influence of advanced phenology. This phenomenon can be attributed not only to the growing seasons of forests starting earlier49, but also to the ability of forests to extract water from deeper soil layers and maintain ET during drier periods23,50. From this perspective, forests act as the primary land cover altering spring moisture recycling patterns, which explains the minimal PRE changes simulated over grassland and desert regions in western China. Spring PWV variations exhibited a stronger spatial polarization between arid and humid regions. This result corroborates prior evidence suggesting that enhanced ET exacerbated existing moisture gradients, leading to increased moisture in wet regions and greater aridity in dry regions37,46. The predominant orientation of the ΔVIMF vectors towards temperate high-latitude humid regions further substantiates this view. Furthermore, advanced phenology partially compensated the weak spring CAPE in the temperate climate zones along the Pacific coast51,52, fostering convective conditions conducive to light-to-moderate PRE.

Prior research based on global observations indicates that the sensitivity of summer ET to vegetation phenological shifts is attenuated by high baseline ET rates and limited soil moisture46. However, our simulations for temperate zones in China demonstrated that advanced growing seasons substantially increased ET, suggesting summer stomatal conductance of temperate vegetation has not yet reached its constrained threshold under current climatic conditions. In-season ET enhancement, coupled with preseason moisture accumulation24,28, elevates PWV across all Chinese climate zones except the Tibetan Plateau, thereby increasing the likelihood of summer PRE51. Notably, despite negligible changes in local ET within inland temperate arid basins, modified atmospheric circulation patterns enhance moisture transport into these regions. Nevertheless, the low ΔCAPE in these regions continues to inhibit the convective conditions necessary for PRE. In other coastal climate zones, summer peaks in CAPE are amplified due to moistening trends driven by phenological advancement28,53. This effect amplifies the potential for deep convection in tropical and subtropical regions, which are characterized by inherently high CAPE, thereby increasing the frequency of extreme PRE events54.

The simulation results indicate that the earlier vegetation leaf-out reduces autumn ET in temperate zones, even though the experimental design did not target phenological changes during this season. This phenomenon can be attributed to the premature depletion of nutrients and soil moisture, which limits transpiration during vegetation senescence36,55. This further elucidates that phenological advancement shifts more atmospheric moisture to spring and summer, while autumn soil moisture struggles to recover through PRE recharge38,56. The positive feedback loop consequently drives a decline in atmospheric PWV at mid- and high-latitudes. Recent studies demonstrate that tropical circulation patterns may counteract changes in local PRE recycling processes, wherein ET-derived moisture returns as local precipitation57,58. In our temperate case study, however, changes in atmospheric circulation enhance the advection of moisture towards tropical and subtropical regions, consequently aggravating climatic aridity in autumn. CAPE exhibits a distinct spatial contrast—increasing in the south and decreasing in the north—that mirrors the spatial polarization of autumn moisture. Contrary to expectations, PRE in southern China has not increased significantly. This may be driven by the wake vertical temperature gradient in autumn, which enhances atmospheric stability and thereby inhibits convective cloud formation and PRE59.

Limitations and future efforts

50% of global soil erosion is caused by water, driven by a complex interplay of factors including climate change, land cover dynamics, soil properties, and topography7,8,40. However, the present study considers only the first two drivers and does not provide a comprehensive simulation or quantification of soil erosion changes induced by shifts in vegetation phenology. This limitation arises because widely used large-scale empirical models for water erosion estimation, such as ULSE and RULSE, primarily rely on annual static input data, making them inadequate for capturing the seasonal mismatches between vegetation dynamics and PRE40. In contrast, process-based models such as the Erosion Productivity Impact Calculator and the Water Erosion Prediction Project can simulate PRE-induced erosion at daily or even hourly scales, but their reliance on extensive and complex physical parameters restricts their applicability at broad spatial scales60. Future research could integrate the complementary strengths of empirical and process-based approaches to quantitatively assess the impacts of phenological advancement on water-driven soil erosion. These impacts are equally important for understanding and monitoring other geomorphic processes, including flash floods, landslides, and debris flows61,62,63,64.

The WRF model was employed to simulate the hydrological feedbacks of phenological advancement across China over the past two decades. To balance computational efficiency with simulation accuracy, the spatiotemporal resolution was set to 6 h and 25 km. However, this configuration limits the ability to capture changes in PRE intensity at the hourly scale, since such intensity is typically derived from the total kinetic energy of a storm and its maximum 30-min precipitation rate65. Consequently, the model exhibits reduced capability in forecasting convective extremes, particularly short-duration heavy precipitation, making it difficult to represent the nonlinear relationship between PRE erosivity and intensity65. Moreover, given the strong influence of underlying surface heterogeneity (e.g., topography, urban land use, and water bodies) on local PRE patterns66, conducting simulations at finer spatial resolutions represents an important avenue for future research. Additionally, due to parameter constraints in the Noah-LSM, groundwater dynamics were not incorporated into our simulations. This omission may introduce errors in representing moisture-cycle efficiency, as groundwater provides substantial subsurface replenishment to vegetation and thereby modifies evapotranspiration intensity—an essential terrestrial source of atmospheric moisture recharge12,28. Therefore, future investigations should aim to systematically refine the representation of multi-source hydrological processes in land–atmosphere interactions through the integration of diverse modeling methodologies.

Data and methods

Study area

This study focused on seven climatic zones in China (Supplementary Fig. S1): the Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid (R1), Mid-Temperate Semi-Humid (R2), Mid-Temperate Arid (R3), Warm Temperate Semi-Humid (R4), Highland Temperate Semi-Arid (R5), North Subtropical Humid (R6), and Marginal Tropical Humid (R7) regions. Since the 1980s, the five temperate regions (R1–R5) have experienced significant spring warming, leading to an advance in spring vegetation leaf-out at a rate substantially exceeding the Northern Hemisphere average32,33,67. Such changes have profoundly affected regional water cycles. Consequently, understanding the vegetation-precipitation feedback mechanisms in these regions is critical for deciphering the spatiotemporal dynamics of global water erosion. The study covered the vegetation growing seasons, including spring (March–May), summer (June–August), and autumn (September–November). To prevent confounding effects from double-cropping systems, relevant pixels were excluded using China’s 1:1,000,000 vegetation map68.

Data sources

The 1-km monthly precipitation dataset for China (MPDC) provided PRE observations for the period 2001–202069. This dataset was developed by downscaling the global 0.5 × 0.5° Climatic Research Unit and high-resolution WorldClim datasets using the Delta method. As previously validated against a network of 496 independent national weather stations, the downscaled data exhibited a 25.7% reduction in mean absolute error and proved effective in capturing detailed spatiotemporal variations in PRE across China69. It was resampled to 500-m resolution using bilinear interpolation for consistency with other datasets. Leaf Area Index (LAI) data were obtained from the Global land surface satellite (GLASS) LAI product with 500 m resolution. This dataset is generated using a bidirectional long short-term memory model that integrates the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) surface reflectance data with existing global LAI products70. Ground-based validation demonstrated that GLASS LAI product achieved higher accuracy than MODIS, with its lower RMSE (0.72) reflecting a more reliable estimation capability of leaf area index across various biomes71. Land cover data were derived from the MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid (version 6.1). This product incorporates temporal smoothing and stability algorithms to enhance classification accuracy and inter-annual consistency. It was used for stable land-cover screening via Google Earth Engine. Specifically, pixels were removed if the Annual International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) classification layer ever labelled them as croplands, urban/built-up lands, or cropland/natural-vegetation mosaics in any year of the study period, ensuring that subsequent analyses captured only unmanaged vegetation dynamics. Finally, both PRE and LAI datasets were masked using the resulting stable land cover data.

The WRF model was configured with leaf area index (LAI) and fractional vegetation coverage (FVC) data derived from the GLASS products. These vegetation parameters, which directly characterize phenological dynamics, modulate biosphere-atmosphere hydrological exchanges and associated climate feedbacks. In this study, the GLASS 8-day composite LAI and FVC datasets, with a spatial resolution of 0.05°, were dynamically incorporated into the WRF simulations. To characterize the typical seasonal cycle of vegetation, multi-year averaged 8-day composites were computed for the period 2001–2020. These data were subjected to bilinear interpolation to align with the spatiotemporal resolution of the regional climate model. The resulting preprocessed LAI and FVC datasets served as the foundation for configuring vegetation phenology in the subsequent simulation experiments. Furthermore, we refined the WRF model’s default snow-free albedo inputs by incorporating GLASS data, thereby enhancing the accuracy of land surface process simulations. The other static geographical data, including soil, land use, and terrain, was obtained from WRF USERS PAGE72,73. This comprehensive data integration strategy enables a more realistic representation of vegetation and land surface characteristics within the model. As a result, it substantially improves the reliability of simulations concerning surface energy budgets, climate feedback mechanisms, and regional hydrological cycle dynamics.

Temporal trends and coherence analysis

The modified Mann-Kendall (M-K) test was used to identify temporal trends in grid-scale spring LAI and PRE74. Comparing to the traditional M-K test, it removes the trend component from the data prior to applying the trend test, specifically to address instances where time series data are not random and are influenced by autocorrelation. The procedure begins by using the Theil–Sen estimator, a robust non-parametric method, to calculate the initial trend slope. If this trend is deemed significant, it is subsequently removed from the original data, resulting in a detrended residual series. The next step involves addressing the lag-one autocorrelation (AR1) by calculating the AR1 coefficient of these residuals and applying a prewhitening technique to eliminate the AR1 component, thereby yielding an independent residual series. Finally, the original trend is reintroduced by combining it with the prewhitened residuals, and the Mann-Kendall test is applied to this final series to evaluate the statistical significance of the trend. Furthermore, linear trend analyses were performed on the mean LAI and PRE for each temperate climate zone to compare variations across regions. The temporal trends identified by different methods exhibit a high degree of consistency (Supplementary Table S2).

Wavelet coherence analysis was employed to investigate the synergistic relationship between multi-year monthly averaged LAI and PRE. This method evaluates localized coherency between two time series in the time-frequency domain by identifying specific frequency bands and temporal intervals75. Wavelet coherence analysis can reveal statistically significant correlations even within regions of low power in the wavelet power spectrum. The wavelet coherence \({R}_{n}^{2}(a)\) for time series X and Y is defined as:

where \({R}_{n}^{2}(a)\) is the wavelet squared coherency; \({W}_{n}^{{XY}}\) denotes the cross-wavelet power spectrum; \({W}_{n}^{X}\) and \({W}_{n}^{Y}\) denote the wavelet transforms of time series X and Y, respectively; \(S\) denotes the smoothing operator in scale and time76. The value of \({R}_{n}^{2}\left(a\right)\) ranges from 0 to 1, and the higher value displays strong correlation at the given frequency and time.

To examine the frequency-dependent lead-lag relationship between time series, we employ phase difference analysis, defined mathematically as:

where \(\xi \) and \({\mathfrak{R}}\) denote the actual and assumed parts of smoothed continuous wavelet transform, respectively. If two time series \(X\) and \({Y}\) are in-phase with \(X\) leading \(Y\), the phase difference \({\varphi }_{{XY}}\) lies within [0, 2π]; otherwise, if \({Y}\) leads \(X\), \({\varphi }_{{XY}}\) falls in [−2π, 0]. Phase opposition is defined by a phase difference of π or −π. Under such a configuration, when \(X\) leads, \({\varphi }_{{XY}}\epsilon [2\pi ,\pi ]\); whereas if \(Y\) leads, \({\varphi }_{{XY}}\epsilon [-\pi ,-2\pi ]\).

Coupled land–atmosphere regional climate model

WRF version 4.2 was employed to simulate and isolate the hydrological impacts of vegetation phenology changes. In this model, the land surface model constitutes a critical component for describing water cycle and energy exchange processes between the land surface and the atmosphere9. Following Yu et al., the Noah land surface model (LSM) was selected to simulate the climatic feedback associated with vegetation phenological variations77. Within Noah-LSM, surface properties are represented using the 24-category United States Geological Survey (USGS) land use and land cover classification. Vegetation growing cycles were parameterized using high-temporal-resolution LAI, FVC, and snow-free albedo data, which enabled accurate phenological representation and systematic evaluation of vegetation-atmosphere feedback mechanisms.

Despite a decelerating trend in temperate vegetation leaf-out advancement across China since the 21st century, leaf-out occurred on average 14.22 days earlier during 1982–199977. To comprehensively represent phenological shifts over the past four decades in temperate China, we adopted a 14-day advancement (Supplementary Fig. S9) in leaf-out timing following the methodological framework of Yu et al.77. Specifically, we computed the multi-year average leaf-out, peak, and dormancy timings for temperate regions during 2001–2020 using LAI and FVC data to reflect recent phenological conditions. This analysis established that peak phenological activity occurs on Julian day 211 (late July), and defined the pre-peak period as the leaf-out phase.

In the experiments, we systematically delayed the growing season of mono-seasonal vegetation by 14 days to reconstruct the early 1980s vegetation characteristics. Identical temporal adjustments were applied to snow-free albedo data, considering the effect of vegetation on solar radiation absorption. Consequently, data corresponding to Julian Days 1–211 were shifted to Julian Days 15–226, while the vegetation dormancy period remained temporally unaltered. These modifications were exclusively implemented for vegetation exhibiting NDVI values exceeding 0.1. The specific experimental configurations comprised:

-

a)

WRFadvance: utilized phenology parameters (LAI, FVC, snow-free albedo) averaged over 2001–2020.

-

b)

WRFhistory: represented historical phenology by applying a 14-day delay to all pre-peak phenology events (i.e., occurrences prior to the 211th Julian Day).

All other experimental conditions between the two model groups, including boundary conditions, atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and land use management practices, were held strictly identical. The scenario simulations spanned the period from January 1st to December 31st annually between 2001 and 2020, incorporating a 2-month spin-up period preceding each simulation year, and the following months were used for analysis. Key physical parameterization schemes comprised the Yonsei University planetary boundary layer scheme, the WRF Single-Moment 3-class microphysics scheme, the Community Atmospheric Model scheme, and the Multi-scale Kain–Fritsch cumulus scheme. Implementation of these schemes adhered to configurations validated in our previous research73. Initial and lateral boundary conditions were provided by the ERA5 6-hourly reanalysis dataset. All simulations were ultimately performed at a spatial resolution of 25 km × 25 km. This controlled-variable experimental design isolated the feedback of advanced spring phenology in temperate vegetation across China on PRE patterns and quantified seasonal variations in the hydrological cycle.

Physical diagnosis of precipitation responses to earlier leaf-out

A detailed physical diagnosis was performed to explore the mechanism underlying PRE changes driven by earlier leaf-out. Based on the outputs of the WRF model, we calculated and compared the differences in evapotranspiration (ET), precipitable water vapor (PWV), vertically integrated moisture flux (VIMF), and convective available potential energy (CAPE) between the two scenarios2,9,10,22. Earlier leaf-out enhances ET as vegetation transpires soil moisture into the atmosphere, providing a primary source for PRE. Meanwhile, these vegetation changes alter the land-surface energy balance, which in turn influences atmospheric structure and moisture transport. We use CAPE to represent changes in atmospheric stability and VIMF to quantify shifts in moisture transport. The integrated response of atmospheric moisture to these vegetation-driven processes is captured by changes in PWV, which serves as a proxy for the potential shifts in PRE probability. Among them, the VIMF is mathematically defined as:

where \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration; \({p}_{s}\) is the surface air pressure at the base of the atmospheric column; \({p}_{t}=300\,{hPa}\) represents the pressure at the top of the column, as water vapor content above this level is typically negligible; \(\vec{{{\rm{V}}}}\) denotes the wind velocity vector at each layer within the column; and \(q\) is the specific humidity at each vertical layer.

CAPE represents the maximum buoyant energy available to an ascending air parcel, calculated by vertically integrating the parcel’s positive buoyancy from its level of free convection (LFC) to its equilibrium level (EL). The specific definition is as follows:

where \({R}_{d}\) is the gas constant for dry air, and \(p\) is the atmospheric pressure. In this context, \({T}_{{vp}}\) and \({T}_{{ve}}\) denote the virtual temperatures of the lifted air parcel and the surrounding environmental air, respectively, which account for the effects of water vapor on air density.

PWV is a critical variable used to indicate the total atmospheric water vapor content in a vertical column. Its distribution and transport are fundamental to understanding the spatiotemporal variability of PRE and the sensitivity to climate change. The calculation is given by:

where \({p}_{z}\) is the surface atmospheric pressure, \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration, \(q\) is the specific humidity, and \(\rho \) is the density of liquid water.

Data availability

The 1-km monthly precipitation data are available at https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2. The GLASS LAI data (500 m) are available at https://www.glass.hku.hk/archive/LAI/MODIS/500M/. The land cover data from the MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid are available at https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/MODIS_061_MCD12Q1. The GLASS LAI data (0.05°) are available at https://www.glass.hku.hk/archive/LAI/MODIS/0.05D/. The GLASS FVC data are available at https://www.glass.hku.hk/archive/FVC/MODIS/0.05D/. The static geographical data used in WRF are available at https://www2.mmm.ucar.edu/wrf/users/download/get_sources_wps_geog.html. The snow-free albedo data from GLASS are available at https://www.glass.hku.hk/archive/Albedo/ABI/0.05D/. The MSWEP precipitation data are available at https://www.gloh2o.org/mswep/. The source data for all figures are publicly available in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30605888.

References

Zhang, Z. et al. Worldwide rooftop photovoltaic electricity generation may mitigate global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 393–402 (2025).

Tian, L. et al. Large-scale afforestation enhances precipitation by intensifying the atmospheric water cycle over the chinese loess plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD036738 (2022).

Huang, S. et al. Widespread global exacerbation of extreme drought induced by urbanization. Nat. Cities 1, 597–609 (2024).

Mullan, D. Soil erosion under the impacts of future climate change: Assessing the statistical significance of future changes and the potential on-site and off-site problems. Catena 109, 234–246 (2013).

Eekhout, J. P. C. & de Vente, J. Global impact of climate change on soil erosion and potential for adaptation through soil conservation. Earth Sci. Rev. 226, 103921 (2022).

Scholz, G., Quinton, J. N. & Strauss, P. Soil erosion from sugar beet in Central Europe in response to climate change induced seasonal precipitation variations. Catena 72, 91–105 (2008).

Borrelli, P. et al. Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015-2070). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 21994–22001 (2020).

Borrelli, P. et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 8, 2013 (2017).

Zhang, B., Tian, L., He, C. & He, X. Response of erosive precipitation to vegetation restoration and its effect on soil and water conservation over china’s loess plateau. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR033382 (2023).

Ge, J. et al. Impact of revegetation of the Loess Plateau of China on the regional growing season water balance. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 515–533 (2020).

Shen, M. et al. Strong impacts of daily minimum temperature on the green-up date and summer greenness of the Tibetan Plateau. Global Change Biol. 22, 3057–3066 (2015).

Young, N. L. et al. A conceptual model for anticipating the impact of landscape evolution on groundwater recharge in degrading permafrost environments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087695 (2020).

Yan, H., Wang, L., Wang, T. W., Wang, Z. & Shi, Z. H. A synthesized approach for estimating the C-factor of RUSLE for a mixed-landscape watershed: A case study in the Gongshui watershed, southern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 301, 107009 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Agricultural land use and management weaken the soil erosion induced by extreme rainstorms. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 301, 107047 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. Global thresholds for the climate-driven effects of vegetation restoration on runoff and soil erosion. J. Hydrol. 647, 132374 (2025).

Ciampalini, R. et al. Modelling soil erosion responses to climate change in three catchments of Great Britain. Sci. Total Environ. 749, 141657 (2020).

Zhang, S., Li, Z., Lin, X. & Zhang, C. Assessment of climate change and associated vegetation cover change on watershed-scale runoff and sediment yield. Water 11, 1373 (2019).

Shmilovitz, Y. et al. Frequency analysis of storm-scale soil erosion and characterization of extreme erosive events by linking the DWEPP model and a stochastic rainfall generator. Sci. Total Environ. 787, 147609 (2021).

Durán Zuazo, V. H. & Rodríguez Pleguezuelo, C. R. Soil-erosion and runoff prevention by plant covers. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 28, 65–86 (2008).

Wu, G. L. et al. Trade-off between vegetation type, soil erosion control and surface water in global semi-arid regions: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 875–885 (2020).

Bai, R. et al. The impact of vegetation reconstruction on soil erosion in the Loess plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 363, 121382 (2024).

Zhang, B., Tian, L., Yang, Y. & He, X. Revegetation does not decrease water yield in the loess plateau of china. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098025 (2022).

Staal, A., Theeuwen, J. J. E., Wang-Erlandsson, L., Wunderling, N. & Dekker, S. C. Targeted rainfall enhancement as an objective of forestation. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17096 (2024).

Yan, Y., Tang, J. & Wang, S. How does greening affect the surface water budget in the Loess Plateau?. Atmos. Res. 311, 107692 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 626–641 (2023).

Gimeno, L. et al. The residence time of water vapour in the atmosphere. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 558–569 (2021).

Cui, J. et al. Global water availability boosted by vegetation-driven changes in atmospheric moisture transport. Nat. Geosci. 15, 982–988 (2022).

Makarieva, A. M. et al. The role of ecosystem transpiration in creating alternate moisture regimes by influencing atmospheric moisture convergence. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2536–2556 (2023).

Wang, X., et al. Vegetation restoration projects intensify intraregional water recycling processes in the agro-pastoral ecotone of Northern China. J. Hydrometeorol. 22, 1385–1403 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. Vegetation restoration increases the drought risk on the loess plateau. Plants 13, 2735 (2024).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Soares-Filho, B. S., Davis, J. L., Abrahão, G. M. & Börner, J. Deforestation reduces rainfall and agricultural revenues in the Brazilian Amazon. Nat. Commun. 12, 2591 (2021).

Caparros-Santiago, J. A. et al. Land surface phenology as indicator of global terrestrial ecosystem dynamics: a systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 171, 330–347 (2021).

Piao, S. et al. Plant phenology and global climate change: current progresses and challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1922–1940 (2019).

Tian, L., Jin, J., Wu, P., Niu, G. & Zhao, C. High-resolution simulations of mean and extreme precipitation with WRF for the soil-erosive Loess Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 54, 3489–3506 (2020).

Wu, S., Yin, Y., Zheng, D. & Yang, Q. Aridity/humidity status of land surface in China during the last three decades. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 48, 1510–1518 (2005).

Lian, X. et al. Summer soil drying exacerbated by earlier spring greening of northern vegetation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax0255 (2020).

Gao, S., Lü, Y. & Jiang, X. Increased precipitation and vegetation cover synergistically enhanced the availability and effectiveness of water resources in a dryland region. J. Hydrol. 654, 132812 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Responses and feedbacks of vegetation dynamics to precipitation anomaly over the semiarid area of north China: Evidences from simulations of the WRF-Noah model. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 804–817 (2023).

Shukla, P. R. et al. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems (IPCC, 2019).

Xiong, M. & Leng, G. Global soil water erosion responses to climate and land use changes. Catena 241, 108043 (2024).

Ying, L. et al. Climate change impairs the effects of vegetation improvement on soil erosion control in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Catena 241, 108062 (2024).

Rao, W., Shen, Z. & Duan, X. Spatiotemporal patterns and drivers of soil erosion in Yunnan, Southwest China: RULSE assessments for recent 30 years and future predictions based on CMIP6. Catena 220, 106703 (2023).

te Wierik, S. A., Cammeraat, E. L. H., Gupta, J. & Artzy-Randrup, Y. A. Reviewing the impact of land use and land-use change on moisture recycling and precipitation patterns. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029234 (2021).

Chen, J., Shao, Z., Deng, X., Huang, X. & Dang, C. Vegetation as the catalyst for water circulation on global terrestrial ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 895, 165071 (2023).

Green, J. K. et al. Regionally strong feedbacks between the atmosphere and terrestrial biosphere. Nat. Geosci. 10, 410–414 (2017).

Zan, B. et al. Spatiotemporal inequality in land water availability amplified by global tree restoration. Nat. Water 2, 863–874 (2024).

Yin, C. et al. Future soil erosion risk in China: differences in erosion driven by general and extreme precipitation under climate change. Earths Fut. 13, e2024EF005390 (2025).

An, Q. et al. Contribution of moisture recycling to water availability in china. Water Resour. Res. 61, e2024WR038054 (2025).

Yu, L. et al. Phenological control of vegetation biophysical feedbacks to the regional climate. Geogr. Sustain. 6, 100202 (2025).

Mu, Y., Biggs, T. W. & Jones, C. Importance in shifting circulation patterns for dry season moisture sources in the brazilian amazon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103167 (2023).

Chen, J., Dai, A., Zhang, Y. & Rasmussen, K. L. Changes in convective available potential energy and convective inhibition under global warming. J. Clim. 33, 2025–2050 (2020).

Yano, J.-I. & Manzato, A. Does more moisture in the atmosphere lead to more intense rains?. J. Atmos. Sci. 79, 663–681 (2022).

Riemann-Campe, K., Fraedrich, K. & Lunkeit, F. Global climatology of convective available potential energy (cape) and convective inhibition (cin) in era-40 reanalysis. Atmos. Res. 93, 534–545 (2009).

Seeley, J. T. & Romps, D. M. Why does tropical convective available potential energy (CAPE) increase with warming?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10,429–10,437 (2015).

Huang, Z., Zhou, L., Zhong, D., Liu, P. & Chi, Y. Declined benefit of earlier spring greening on summer growth in northern ecosystems under future scenarios. Agric. For. Meteorol. 351, 110019 (2024).

Jia, X., Shao, M., Zhu, Y. & Luo, Y. Soil moisture decline due to afforestation across the Loess Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 546, 113–122 (2017).

Hoek van Dijke, A. J. et al. Shifts in regional water availability due to global tree restoration. Nat. Geosci. 15, 363–368 (2022).

Tuinenburg, O. A., Bosmans, J. H. C. & Staal, A. The global potential of forest restoration for drought mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034045 (2022).

Ustrnul, Z., Woyciechowska, J. & Wypych, A. Relationships between temperature at surface level and in the troposphere over the northern hemisphere. Atmosphere 14, 1423 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Modelling the impacts of climate and land use changes on soil water erosion: Model applications, limitations and future challenges. J. Environ. Manag. 250, 109403 (2019).

Fang, Z. et al. Climate change has increased rainfall-induced landslide damages in central China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 119, 105320 (2025).

Fowler, H. J. et al. Anthropogenic intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 107–122 (2021).

Ozturk, U. et al. How climate change and unplanned urban sprawl bring more landslides. Nature 608, 262–265 (2022).

Stoffel, M. et al. Climate change effects on debris flows. In Advances in Debris-flow Science and Practice, 273–308 (Springer International Publishing, 2024).

Gao, G., Liang, Y., Liu, J., Dunkerley, D. & Fu, B. A modified RUSLE model to simulate soil erosion under different ecological restoration types in the loess hilly area. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 12, 258–266 (2024).

Greve, P. et al. Observational evidence of increased afternoon rainfall downwind of irrigated areas. Nat. Commun. 16, 3415 (2025).

Wu, X. & Liu, H. Consistent shifts in spring vegetation green-up date across temperate biomes in China, 1982–2006. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 870–880 (2013).

Zhang, X. Vegetation map of the People’s Republic of China (1:1 000 000)) (Geology Press, 2007).

Peng, S., Ding, Y., Liu, W. & Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1931–1946 (2019).

Ma, H. & Liang, S. Development of the GLASS 250-m leaf area index product (version 6) from MODIS data using the bidirectional LSTM deep learning model. Remote Sens. Environ. 273, 112985 (2022).

Xu, B. et al. An integrated method for validating long-term leaf area index products using global networks of site-based measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 209, 134–151 (2018).

Yu, L., Liu, Y., Liu, T. & Yan, F. Impact of recent vegetation greening on temperature and precipitation over China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 295, 108197 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Enhanced climate mitigation feedbacks by wetland vegetation in semi-arid compared to humid regions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL115242 (2025).

Yue, S., Pilon, P., Phinney, B. & Cavadias, G. The influence of autocorrelation on the ability to detect trend in hydrological series. Hydrol. Process. 16, 1807–1829 (2002).

Zhou, Z. et al. Assessing the responses of vegetation to meteorological drought and its influencing factors with partial wavelet coherence analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 311, 114879 (2022).

Cheng, Q., Zhong, F. & Wang, P. Baseflow dynamics and multivariate analysis using bivariate and multiple wavelet coherence in an alpine endorheic river basin (Northwest China). Sci. Total Environ. 772, 145013 (2021).

Yu, L. et al. Extreme hydroclimates amplify the biophysical effects of advanced green-up in temperate China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 363, 110421 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2024YFD1501600), Strategic Priority Research Program (A) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA28080503), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2023240), and Jilin Province Changbai Elite Talent Program (202441137). The numerical calculations in this study were carried out on the ORISE Supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft. J. Y.: Data Curation, Formal Analysis. H. Z.: Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. W. L.: Writing - Review & Editing. Y. W.: Writing - Review & Editing. H. L.: Project Administration. L. Y.: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Subhankar Das, Violeta Tolorza and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Charlotte Kendra Gotangco Gonzales and Mengjie Wang. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Z., Yang, J., Zhang, H. et al. Biophysical feedback from earlier leaf-out enhances nonerosive precipitation in China. Commun Earth Environ 7, 21 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03054-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03054-x