Abstract

A limitation in characterizing three-dimensional (3D) soil water flow from dye-stained images hinders further insights into the role of 3D root systems. Here we used X-ray computed microtomography, dye-tracing experiments, and 3D soil water flow modeling software to imply the dual function of 3D root systems. Our results revealed that soil water flow traits exhibited depth-dependent changes at the mixed forest stands with loam soils. We also concluded that root systems under loam soil conditions could promote both preferential flow- and soil matrix flow behavior. Preferential flow will dominate soil water flow behavior when the key indicators of root systems traits were less than a critical value; otherwise, soil matrix flow will dominate. Critical values of the indicators inducing the transfer of soil water flow behavior varied for different soil water flow traits. Our study provides an insight into the dual function of root systems from a 3D perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil water flow as the carrier of labile substrates could provide nutrients for vegetation growth1,2,3. In turn, the accumulation of vegetation root systems could also influence the soil water flow behavior, known as “co-evolution”4. This is probably related to two common mechanisms: firstly, coarse root systems strengthen the water retention capacity5 and root systems exudates become hydrophobic6, and secondly, root systems usually affect the soil water flow behavior originating from the heterogeneity of pore space7. Some studies have demonstrated that vegetation-covered areas differ from bare land in terms of the soil water flow behavior due to the impacts of root systems7,8,9. Soil water flow behavior is characterized by two main types: preferential flow and soil matrix flow10,11,12. Preferential flow driven by gravity force mainly moves through soil macropores13, while soil matrix flow is mainly driven by capillary force3,10. The spatial distribution of preferential flow and soil matrix flow at the soil profile is extremely heterogeneous, resulting in their gradually changing role in the soil water flow behavior with increasing soil depth14. In fact, the changing role of the two main types with soil depth could be attributed to the “threshold behaviors”, which may influence the soil water infiltration. For example, root length density below a threshold could correspond to an increase in soil water infiltration, while above this threshold, they observed a decrease in soil water infiltration15. The “threshold behaviors” are usually observed because of the alteration of the internal states or the discontinuous boundary conditions, which could advance the interpretation of the gradually changing role16. However, to our knowledge, there is no threshold behaviors to describe the changing role of preferential flow and soil matrix flow in the root zones.

Broad statements commonly certify the interaction between the root systems from two-dimensional (2D) patterns and soil water flow behavior, which results in the over- or underestimation of the effects of the root systems17. Specifically, detailed knowledge on how root systems impact the three-dimensional (3D) pore structure even soil water flow at a microscale is often contradictory18. Yet available data are scarce to accurately characterize the soil water flow behavior in terms of the effects of the root systems from 3D patterns19. Compared to 2D patterns, 3D patterns could effectively distinguish the spatial shape and distribution of the root systems within the soils20. That is, root systems from 3D patterns might catch more accurate information, such as root branching and growth orientation. In addition, 3D fine root systems could grow in a horizontal orientation, whereas fine root systems from 2D patterns appeared parallel to the main root systems21. However, limited studies reported the dual function of root systems from 3D patterns on soil water flow behavior. Although the dye-tracing experiments have made it possible to indicate soil water flow paths, detailed description of 3D soil water flow behavior has not yet been provided, which also limits accurate analysis of soil water flow behavior5,22,23. For example, one indicator of 3D soil water flow, such as the degree of connectivity, is usually underestimated due to the unresolved 3D flow connections24,25,26. Although the studies obtained from the dye-tracing experiments illustrate the soil water flow paths from 2D patterns with a high spatial resolution, it can’t clearly reveal the actual 3D water flow27. Soil water flow paths are comprised of one or more pore networks, each characterized by multiple paths with different diameter or length, or connectivity24. Those paths are part of the “percolating network”, which comprises a “backbone” fraction (i.e., preferential flow paths) and “edge” fraction (i.e., the areas where preferential flow interacts with the surrounding soil matrix)12,28. To the best of our knowledge, achieving 3D reconstructions of soil water flow based on the dye-tracing experiments is facing great challenges.

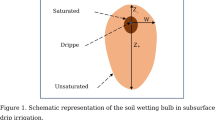

In comparison to traditional assessment of soil water flow behavior from 2D patterns, the 3D patterns have been proposed to effectively imply the efficiency of soil water flow3,5. 3D soil water flow behavior could fully reflect the chance of labile substrates carried by preferential flow paths or stored by the surrounding soil matrix2,29. Preferential flow and soil matrix flow play different roles in soil biogeochemical processes12. In general, preferential flow could not only transmit large volume of water and labile substrates but also supply new inputs. The high degree of preferential flow should improve the convenience of water and labile substrates exchange between preferential flow paths and the surrounding soil matrix. Meanwhile, soil matrix flow might offer the intra-connections between the soil macropores and the surrounding soil matrix and also the inter-connections inside the soil matrix, at which microbial activities occur and byproducts store12,30,31. The connections between the soil macropores and the surrounding soil matrix could be influenced by water pressure. This is because the fast water pressure between the preferential flow paths and the surrounding soil matrix was built as most of the water infiltrates into the preferential flow paths32,33. The difference in water pressure between the two domains leads to water and labile substrates exchange from the preferential flow paths to the soil matrix in the root zones33. The intra-connections and inter-connections could be achieved by pressure propagation and water exchange between the two domains33. However, root systems could form self-organized root channels, resulting in water pressure response when water infiltrates into the channels34. Furthermore, root systems by means of water uptake could induce soil matric suction, causing a significant reduction of water pressure35. Yet, we know very little about “how does root systems coordinate the balance of the intra-connections and inter-connections?”, which particularly limits our understanding of the dual function of root systems. In this study, artificial forests dominated areas were selected to explore root systems in balancing soil water flow behavior. We hypothesized that as root content is below a critical value, preferential flow could dominate the soil infiltration, while soil matrix flow is the main behavior after reaching the critical value. This study involved the reconstruction of the 3D root systems by X-ray microtomography scanning. To visualize the actual 3D soil water flow, the dye-tracing experiments with modules in the 3D soil water flow modeling software were applied. The geometry and topology of 3D soil water flow were analyzed after reconstructions. Soil infiltration experiment was conducted to reflect the soil saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) (Fig. 1).

a Schematic diagram of the mixed forest stands (Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands, Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, and Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands). b Three sampling plots (20 × 20 m) and nine dye-tracing experiments were constructed in each site. Eight vertical dye-stained images were acquired at the interval of 1.0 cm. Soil cores were collected by PVC cylinders corresponding to the dye-stained areas. c CT scanning of the soil cores to reconstruct the actual distribution of root systems in the soil and obtain the 3D root systems traits. d 3D soil water flow reconstruction. The dye-stained images could be categorized into four parts. Blue is preferential flow paths (PFP), light blue is the high interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix (HIA), green is the low interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix (LIA), and white is no interaction area. In addition, CPH (the combination of preferential flow paths and high interaction areas), CPL (the combination of preferential flow paths and low interaction areas), and CHL (the combination of high interaction areas and low interaction areas) patterns were also considered as important soil water flow patterns. e The indicators of 3D root systems traits, including architectural traits, morphological traits, spatial traits, and the root biomass (RB). Root systems architectural traits included root number (RN), root length (RL), root surface area (RSA), and root volume (RV); Root systems morphological traits included root width (RW), root tortuosity, specific root length (SRL), specific root surface area (SRA), and root tissue density (RTD); Root systems spatial traits included root coordination number, root fractal dimension, root growth orientation theta, and Gini index. f Test for soil saturated hydraulic conductivity. g The indicators of 3D soil water flow traits, including architectural traits, morphological traits, spatial traits, and the connectivity degree (Dc). Architectural traits included the cluster number (i,e., 3D soil water flow paths number), the length ratio (Lw), the surface ratio (Sw), and the volume ratio (Vw) of 3D soil water flow paths; Morphological traits included the tortuosity, interconnectivity, connectivity probability (Γw), and Euler-Poincaré characteristic density (χn) of 3D soil water flow paths; Spatial traits included 3D soil water flow paths fractal dimension, the difference between capacity dimension and entropy dimension (D0-D1), generalized dimension spectrum (∆D), and the width of the singularity spectrum (∆α).

Collectively, our study addressed three primary objectives: (1) Revealing the regulation of the changes in the geometry and topology of 3D soil water flow. (2) Exploring the spatial distribution heterogeneity of 3D root systems within the soils. (3) Recognizing the mechanisms of root systems in balancing preferential flow- and soil matrix flow behavior. The obtained understanding could help reveal the forestry soil hydrological processes and provide a scientific basis for sustainable forestry management.

Results

The 3D soil water flow characterization

We achieved 3D reconstruction of soil water flow paths and quantified the geometry and topology of these paths based on the dye-stained images (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrated the investigated architectural, morphological, spatial traits of these paths. The agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis confirmed that a first cluster grouped preferential flow situation (preferential flow paths, PFP; the combination of preferential flow paths and low interaction areas, CPL; and the combination of preferential flow paths and high interaction areas, CPH), while a second cluster associated soil matrix flow situation (low interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix, LIA; high interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix, HIA; and the combination of high interaction and low interaction areas, CHL) (Fig. 2c).

a Samples of 3D soil water flow paths constructed by dye-stained images. b The indicators of 3D soil water flow paths across soil depths. Bars represented mean ± s.e.m. c The agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis of the soil water flow patterns. Two dominated soil water flow clusters could be classified, i.e., preferential flow situation (PFP, CPH, and CPL) and soil matrix flow situation (HIA, LIA, and CHL). d Smoothed curves of generalized additive models showed deviation from the mean model predictions for the Γw as selected response variables with the Vw as the predictor variable. The grey shading represented one SE from the predicted line for the estimated Γw based on the Vw across the mixed forests. e The conceptual diagram of connectivity degree constructing. The lower connectivity probability of 3D soil water flow (Γw) could lead to the lower connectivity degree (Dc) at the same proportion of the volume of 3D soil water flow paths to the total soil layers (Vw). Similarly, the lower Vw could lead to the lower Dc at the same Γw. f The Dc in different soil water flow patterns across soil depths. The higher the value, the darker the color on the contour map. g The soil saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks) across soil depths. The solid line represented the actual value, and the light-blue shading represents standard errors. h The relationship between the constructed comprehensive indicators of 3D soil water flow paths and the original indicator. * was 0.01 < P < 0.05, ** was 0.001 < P < 0.011, *** was P < 0.001 (Pearson correlation analysis). More details on the constructed comprehensive indicators of soil water flow paths were summarized in Supplementary Fig. 4.

For architectural traits, the length ratio (Lw) and the volume ratio (Vw) in the preferential flow situation decreased with increasing soil depth (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1), while in the soil matrix flow situation, they as a whole increased at first and then decreased. Conversely, the maximum number of clusters in the preferential flow situation was at the soil depth of 30–40 cm, while it showed the fluctuating trend with increasing soil depth in the soil matrix flow situation. The surface ratio (Sw) both in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation showed the highest value at the soil depth of 10–20 cm (Fig. 2b). Across the soil depth in the preferential flow situation, the largest Lw (3.09 ± 0.10%) and number of clusters (33.00 ± 15.58 n 400 cm−3) at the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, the largest Vw (47.75 ± 9.47%) at the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands, and the largest Sw (11.03 ± 1.96%) at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands were dramatically concluded. Yet, the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands had the largest Sw (9.23 ± 2.37%), Lw (0.81 ± 0.31%), and Vw (21.61 ± 9.76%) in the soil matrix flow situation, while the largest number of clusters (93.43 ± 19.74 n 400 cm−3) at the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands was illustrated (Supplementary Fig. 2).

With respect to morphological traits, the tortuosity, interconnectivity, and the connectivity probability (Γw) in the preferential flow situation decreased with increasing soil depths (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1), while they increased at first and then decreased with increasing soil depth in the soil matrix flow situation. However, the results of the Euler-Poincaré characteristic density (χn) both in the preferential flow- and the soil matrix flow situation were contrary to the other three indicators of the morphological traits (Fig. 2b). It was showed that the interconnectivity was the largest in the preferential flow situation at the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands across the soil depth, followed by Quercus acutissima Carruth- and Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. Yet, the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands had the smallest tortuosity (1.23 ± 0.02), χn (−3.49 ± 1.61), and Γw (0.66 ± 0.06). In the soil matrix flow situation, it was found that the largest tortuosity, χn, and Γw, but the smallest interconnectivity at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands was indicated in Supplementary Fig. 2.

In the preferential flow situation, both the fractal dimension and the difference between capacity dimension and entropy dimension (D0-D1) of the spatial traits decreased with increasing soil depth, whereas they initially increased and then decreased in the soil matrix flow situation (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1). The generalized dimension spectrum (∆D) and the width of the singularity spectrum (∆α) increased at first and then decreased with increasing soil depth in the preferential flow situation, while in the soil matrix flow situation, they showed fluctuating changes (Fig. 2b). All the four indicators of the spatial traits across the soil depth in the preferential flow situation were the largest at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands, followed by Phyllostachys edulis and Pinus taeda L. dominated stands. However, in the soil matrix flow situation, the fractal dimension and D0-D1 were in the following order: Quercus acutissima Carruth-, Pinus taeda L.-, and Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. We observed that the ∆D and ∆α were the largest at the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands and the smallest at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The generalized additive model exhibited that the Γw was positively correlated to the Vw as the S-shape curve increases (P < 0.001; Fig. 2d). We found that the Γw increased rapidly with the increase of the Vw when Vw < 50%, while the Γw became stable when Vw > 50% (Fig. 2d). Moreover, after the evaluation of the Vw and Γw, the Dc was also quantified (Fig. 2e). The Dc decreased with increasing soil depth when the role of preferential flow dominated the soil water flow behavior, while the Dc increased at first and then decreased with increasing soil depth in the soil matrix flow situation (Fig. 2f). The Dc in the PFP was significantly higher than that both in LIA and HIA (P < 0.001), and the Dc both in CPH and CPL was significantly higher than that in CHL, HIA, and LIA (P < 0.01) (Supplementary Table 2). Notably, there was a strong positive correlation between the Dc and soil water flow connectivity simulated by common methods (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). In the Supplementary Fig. 3c, better common method performance of the integral index of connectivity (IIC) concluded that there was a lower difference between the results of the Dc and predicted soil water flow connectivity. A steeper receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was found for the simulated IIC compared with the connectivity index (CI), the index of soil water flow connectivity (IWFC), and the connectivity function (τ), showing the best performance. In addition, we found that the Ks decreased with increasing soil depth (Fig. 2g). Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated that the constructed comprehensive indicators of 3D soil water flow paths were significantly correlated with the original indicator (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 4).

The partial least squares path modeling analysis (PLS-PM) revealed that the 3D soil water flow paths and the Ks were indirectly influenced by alternating root systems and soil physicochemical properties rather than a direct pathway (Supplementary Table 3). The results concluded that 3D preferential flow behavior could positively drive the changes in the Ks (total effects: 0.69), while the Ks was negatively influenced by 3D soil matrix flow behavior (total effects: −0.16) (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, the linear regression analysis exhibited that the 3D soil water flow connectivity in the preferential flow situation showed strong positive correlations with the Ks, while there was a negative relationship between the connectivity in the soil matrix flow situation and the Ks (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

The 3D root systems quantification

The 3D visualization of the root systems which could characterize their actual spatial distribution was indicated (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5). The root number (RN), root length (RL), root surface area (RSA), root volume (RV), root width (RW), root tissue density (RTD), root fractal dimension, root coordination number, and root biomass (RB) decreased with increasing soil depth significantly (P < 0.05). On the contrary, the specific root length (SRL) and specific root surface area (SRA) increased with increasing soil depth (P < 0.05). Root tortuosity (1.18 ± 0.02), root growth orientation theta (58.44 ± 0.78°), and Gini index (0.32 ± 0.04) showed that there were no significant differences at the different soil depths (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3b–e). Figure 3f demonstrated that the constructed comprehensive indicators of 3D root systems traits were significantly correlated with the original indicator (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 6).

a Samples of the visualization of root systems distribution at the mixed forest stands. The indicators of 3D root systems traits across soil depths, including architectural traits (b), spatial traits (c), morphological traits (d), and root biomass (e). Boxplot center line represented median, box limits the first and third quartiles, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values no further than 1.5×interquartile range (IQR). Points outside the box were outlier. Lowercase letters indicated differences in relevant indicators of 3D root systems traits among different soil depths at the P < 0.05 level (mixed-effects models). f Relationships between the constructed comprehensive indicators of 3D root systems traits and the original indicator. * was 0.01 < P < 0.05, ** was 0.001 < P < 0.011, *** was P < 0.001 (Pearson correlation analysis). More details were summarized in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Three different dominated-vegetation at the mixed forests could lead to the various distribution of root systems among soil depths (Supplementary Fig. 7). As the dominated-vegetation was Quercus acutissima Carruth, the root systems mainly concentrated at the soil depth of 0–10 cm, with RN accounting for 40.59 ± 14.10%, RL 36.98 ± 12.88%, RW 34.91 ± 14.53%, RSA 32.67 ± 12.87%, and root coordination number 40.59 ± 14.10% respectively. At the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, the root systems with the maximum RN (8114.67 ± 5246.03 n 400 cm−3), RSA (228.70 ± 25.90 cm2 400 cm−3), RL (897.12 ± 253.70 cm 400 cm−3), RW (124.46 ± 26.69 cm 400 cm−3), RB (2.59 ± 1.20 g 400 cm−3), root coordination number (16231.33 ± 10492.05 n 400 cm−3) mainly concentrate on the soil depth of 10–20 cm. The root systems uniformly distributed among different soil layers at the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. However, the SRL and SRA showed the largest at the soil depth of 30–50 cm, indicating that the vegetation in this study could still enhance nutrient and water uptake to sustain their productivity under conditions of the low availability of soil resources in the subsoil.

RN, RL, RW, RSA, SRL, SRA, root coordination number, Gini index, root growth orientation theta across the soil depth were in the following order: Quercus acutissima Carruth->Pinus taeda L.->Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. RB and RTD were the largest at the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, followed by Quercus acutissima Carruth- and Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. RV across the soil depth at the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands was the largest. The root tortuosity and fractal dimension showed the similar results across the soil depth between the three stands (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Mechanisms of soil water flow through root systems

The PLS-PM results verified that root systems provided substantial positive contributions not only for the 3D preferential flow behavior (total effects: 0.41 ± 0.09) but also for the 3D soil matrix flow behavior (total effects: 0.44 ± 0.15) (Fig. 4a, c and Supplementary Table 3), implying the dual function of root systems on soil water flow. In further, the root systems had positive total effects on the Ks through influencing the 3D soil water flow (total effects: 0.17 ± 0.01). To be specific, the root systems had indirect effects on the Ks (indirect effects: 0.27 ± 0.06) when the role of preferential flow dominated the soil water flow behavior. However, the root systems had positive direct effects on the Ks (direct effects: 0.29 ± 0.06) when the role of soil matrix flow dominated the soil water flow behavior (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). Pearson correlation analysis and redundancy analysis revealed the relationship between the indicators of root systems traits and 3D soil water flow traits in preferential flow paths and soil matrix flow areas (Fig. 4d, e and Supplementary Table 4), including the comprehensive indicators and the original indicators selected based on the minimum dataset (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a The partial least squares path modeling analysis (PLS-PM) depicted factors influencing the Ks through direct and indirect pathways. Included factors were SOC, chosen soil physical properties, i.e., total soil porosity (TSP), initial soil water content (ISWC), and silt content, 3D soil water flow traits, and 3D root systems traits. The architectural, morphological, and spatial traits of 3D root systems and 3D soil water flow were the corresponding constructed comprehensive indicators obtained from the first principal component (PC1). Significant paths were displayed by solid lines (P < 0.05), while dashed lines represented the paths with P > 0.05. Black and blue lines indicate positive and negative effects respectively, while the indicated values on the lines are the path coefficients for the inner model. The R2 values were listed for response variables. The NFI indicated normed fit index. b The effects of 3D soil water flow paths in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situations on the Ks. c The effects of root systems on 3D soil water flow paths in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situations. d Pearson correlation analysis between the indicators of root systems traits (root biomass and comprehensive indicators) and 3D soil water flow traits (Dc and comprehensive indicators) of preferential flow paths and soil matrix flow areas. e Redundancy analysis of the relationships among selected original indicators based on the minimum dataset. The original indicators included root systems traits and 3D soil water flow traits of preferential flow paths and soil matrix flow areas.

It was evident that there was a critical value of soil water flow behavior at a certain soil depth (Figs. 5a and 6a), that is, the dual function of root systems in balancing soil water flow behavior was illustrated. For the indicators of architectural-, morphological traits, and Dc, the critical value appeared at the soil depth of 10 cm at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands, while it appeared at the soil depth of 20 cm at the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands. However, there was no critical value at the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands, indicating preferential flow dominating the soil water flow behavior across the soil depth (Figs. 5a and 6a). The results of the random forest models showed that RL, RW, RSA, SRA, RTD, RN, RB, root growth orientation theta, Gini index, and root coordination number could significantly cause soil water flow behavior transfer from 3D preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5b). The threshold of the selected indicators of 3D root systems traits driving the transfer was quantified, where the RTD was 0.48 g cm−3 and RL was 225.36 cm 400 cm−3 for the architectural traits of 3D soil water flow, root growth orientation theta was 57.03°, and Gini index was 0.30 for the morphological traits of 3D soil water flow. Moreover, with respect to the Dc of 3D soil water flow, the threshold was as follows: RL was 633.93 cm 400 cm−3, RN was 3819.29 n 400 cm−3, RW was 101.58 cm 400 cm−3, RSA was 193.20 cm2 400 cm−3, and root coordination number was 7640.58 n 400 cm−3 (Fig. 5c).

a The transfer of soil water flow behavior at the mixed forest stands. The regression line across observations was based on a quadratic regression model. The blue fitting line was the variation of the constructed comprehensive indicators and the Dc in the preferential flow path with soil depth and the light-blue fitting curve was the constructed comprehensive indicators and the Dc in the soil matrix flow area. Bar values were the mean ± standard error. For architectural traits, morphological traits, and the Dc of 3D soil water flow, the intersection point of fitting lines was below the soil depth of 10 cm at Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands (i) and below the soil depth of 20 cm at Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands (ii), while there was no intersection point at Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands (iii). With respect to the spatial traits, the intersection point of fitting lines appeared at the soil depth of 20 cm for the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, while it appeared at the soil depth of 30 cm for the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands, while there was no intersection point at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands. b The key indicators of root systems traits inducing the transfer of soil water flow behavior. Soil water flow behavior was recognized as a binary variable, with “0” representing preferential flow dominating the water flow behavior and “1” representing the transfer from preferential flow dominated to soil matrix flow dominated. The soil water flow behavior was response variables and the root morphological trait was the predictor variable. The key indicators were chosen with P < 0.05 from the random forest model. c The critical value of the key indicators of root systems traits inducing the transfer. The logistic regression showed the critical value was obtained when the transfer probability was set at 0.5 (i.e., the inflection point).

a The root systems distribution and soil water behavior were different at the three mixed forest stands. In Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands, root systems were mainly distributed at the soil depth of 0−10 cm. For architectural traits, morphological traits, and the Dc, the transfer of soil water behavior from preferential flow dominating to soil matrix flow dominating appeared at the same soil layer. For the spatial traits, the transfer did not appear throughout the entire soil profile. At Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, root systems mainly concentrated at the soil depth of 10–20 cm. The transfer of architectural-, morphological-, spatial traits, and the Dc for soil water behavior appeared at the same soil layer. At Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands, the root systems evenly distributed across soil depths, and the architectural traits, morphological traits, and the Dc of the preferential flow dominated the water flow behavior at the whole soil profile. Yet, for spatial traits, the transfer appeared at the soil depth of 30 cm. b The relationship between the connectivity of preferential flow paths and the Ks. (i) A well inter-connected preferential flow path (a single water cluster) with a uniformly high Ks denoted by dark shading. The brown line represented soil macropores. (ii) An isolated preferential flow path. It showed lower Ks because the macropore network is poorly connected locally. At the Darcy scale, just a continuous preferential flow path through the sample (dark shading) surrounded by the soil matrix (light shading). (iii) A broken preferential flow path transport. The Ks were now uniformly the lowest. c Dual function of root systems in soil water flow behavior. (i) Root systems showed positive effects on preferential flow and soil matrix flow. (ii) Root channel formation provides preferential paths. The mesh structure during root permeation could induce more active water to the surrounding pores to enhance the connectivity of preferential flow paths. (iii) Root systems could promote the interaction between preferential flow paths and the surrounding soil matrix. Root systems could occupy pores and align the surrounding soil particles. Those newly formed micro- or meso-pores might produce stronger capillary forces to retain water flow. d Effects of root systems on soil water flow behavior. (i) Aggregated root systems stitched preferential flow paths. Fine root systems were fully dyed. (ii) Coarse root systems would result in water accumulation. Coarse root systems were partially dyed.

It was notably conclude that the critical value of the transfer from the spatial traits of 3D soil water flow appeared at the soil depth of 20 cm for the Pinus taeda L.-dominated stands, while it appeared at the soil depth of 30 cm for the Phyllostachys edulis-dominated stands. Yet, there was no critical value at the Quercus acutissima Carruth-dominated stands (Figs. 5a and 6a). RB with a threshold of 2.11 g 400 cm−3 and RW with a threshold of 109.44 cm 400 cm−3 could drive the transfer from the 3D soil matrix flow- to preferential flow behavior, while SRA with a threshold of 79.77 cm2 400 cm−3 could drive the transfer from 3D preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

3D soil water flow traits and their driving mechanisms

We characterized the geometry and topology of 3D soil water flow paths by quantifying indicators in their architectural, morphological, and spatial traits36,37. The consistent correlation between the other indicators in both preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation reflects a common regulation (Supplementary Fig. 9). Positive correlations were found between the architectural traits (Lw, Sw, and Vw), morphological traits (interconnectivity, tortuosity, and Γw), and spatial traits (fractal dimension and D0-D1). This is because the higher Lw, Sw, and Vw result in a larger possibility of the connections between these paths, which would in further form, a uniformly developed ‘percolating network'23,28,38,39. It is no doubt that the number of clusters and χn showed negative correlations with the Lw, Sw, Vw, interconnectivity, tortuosity, Γw, fractal dimension, and D0-D1 (Supplementary Fig. 9). The explanation might be attributed to the formation of isolated soil water flow paths (“scattered network”) due to the increasing clusters37,38,39. Notably, the changes of ∆D and ∆α in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation were not consistent, implying the complex and non-uniform distribution of 3D soil water flow paths40.

Besides to the different role of the “network” in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation, it’s worth noting that the different geometry and topology of 3D soil water flow paths between them should be also fully recognized (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the results of the existing studies3,22, the preferential flow paths distribution at the soil depth of 0–10 cm were well-connected, which could be better explained by large Lw, Sw, Vw, interconnectivity, tortuosity, Γw, and low number of clusters and χn36,38,39. In addition, large fractal dimension, D0-D1, and low ∆D and ∆α in preferential flow paths illustrated their uniform distribution within the soils40. As expected, most of the indicators without the number of clusters, χn, ∆D, and ∆α in soil matrix flow areas were lower than those in the preferential flow paths at the soil depth of 0–10 cm, demonstrating a dispersed distribution of the areas40. In our findings, the preferential flow paths distribution below the 10 cm soil layers was consistent with the previous results22,23, illustrating the gradual development of “scattered network” supported by large ∆D and ∆α40. That is, higher Lw, Sw, Vw, interconnectivity, tortuosity, Γw, fractal dimension, D0-D1 below the soil depth in the soil matrix areas were concluded compared with those in the preferential flow paths. Therefore, the effects of the soil depth promote us to pay attentions to the threshold behaviors of changes in 3D soil water flow behavior.

Although the indicators of the geometry and topology of 3D soil water flow paths showed obvious advantages, the proposed Dc in our study might better characterize the 3D “percolating network”37,41. The Dc in the preferential flow situation was the highest at the soil depth of 0–10 cm, indicating a relatively complete percolating network formed by preferential flow paths, which could be explained by the high Vw and Γw at such a soil layer28. Furthermore, it is essential to consider the “inflection point” when we characterized the relationship between the Vw and Γw (Fig. 2d). When the Vw was the same, Γw might be different, originating from the higher heterogeneity in the morphology of the complex percolating network (Fig. 2e). In our results, the inter-connectivity of soil water flow paths was strengthened with the increase of Vw as the value of Vw was <50%, which further promotes the stability of the percolating network3,28,38. Yet, the Γw approached 1 when the value of Vw was >50%, indicating that the percolation network is composed of a dominant connected water cluster38,41. As expected, the Dc in the preferential flow situation exerted a positive influence on the Ks, while the Dc in the soil matrix flow situation was contrary (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3d). This is because the high Dc in the preferential flow situation indicates a strong inter-connectivity of preferential flow paths, which could reduce the barriers from the surrounding soil particles and promote the infiltrating water to move faster through the existing macropores networks3,42,43. However, the high Dc in the soil matrix flow situation represents the occurrence of large amount of meso- and micro-pores, that is, those pores could produce stronger capillary force and in further store the infiltrating water3,10. The Dc in the soil matrix flow situation could be also promoted around the typically tubular and highly connected root channels44, which results in the increase of the soil matrix flow areas. Such areas could enhance water storage in soils and lead to lower Ks5,10. Therefore, the high Dc in the soil matrix flow situation could inhibit the fast infiltration. Meanwhile, our results demonstrated that the positive effects of the percolating network in the CPH and the CPL on the Ks could be prohibited compared with the effects of the network in the PFP at some degree (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3d). The possible mechanism might be that the soil matrix flow could induce the radial infiltration losses of preferential flow45,46. Especially, the high interaction between the preferential flow paths and the surrounding soil matrix would result in more water storage in soils, which would also explain the phenomenon that the percolating network in the CPH showed a lower positive effect on the Ks than the network in the CPL11 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3d).

In our study, the results revealed that the mechanisms driving the changes in Ks were fully recognized into the following components, i.e., soil water flow traits, root systems traits, soil physical properties, and soil organic carbon (Fig. 4a). In preferential flow situation, soil physical properties exerted positive effects Ks by mainly promoting soil water flow traits, which could be explained by the high total soil porosity and soil moisture. This is because that a high content of the total soil porosity, to some degree, could promote the occurrence of the well inter-connected macropore networks3,45. The inter-connected macropores are hydrologically active to participate in soil water flow events5,17, which could promote the amount of active preferential flow paths (Supplementary Fig. 10). Studies had showed that well-connected preferential flow paths could lead to a uniformly high macroscopic hydraulic conductivity42,46 (Fig. 6b). In addition, a high soil moisture could lead to a strong matric potential of mesopores and micropores, reducing the lateral flow into the surrounding soil matrix and promoting the development of preferential flow paths47,48, and in final resulting in a high Ks42,46. The effects of silt content on the preferential flow paths was not significant in this study (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 10). The PLS-PM also revealed that soil organic carbon indirectly influenced soil water flow traits and Ks by alternating soil physical properties (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). The possible mechanism might be attributed to the positive influences of soil organic carbon on promoting soil aggregation and structuring soil particles49,50. Studies concluded that active soil organic carbon could both increase the content of soil finer particles and improve the stability of the particles51. This is because that soil organic carbon as a organic cementing substance could combine with the particles, which could form a organic-inorganic aggregation52. The formation of the stable aggregation could create larger volumes of macro-, meso-, and micropores, which might in further improve the content of the total soil porosity and soil moisture49,53,54. Similarly, the positive indirect effects of root systems traits on Ks were larger than their direct effects in preferential flow situation (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). The mechanism is that root systems could facilitate soil water flow traits by forming distinctive root channels and then promote the connectivity and size of soil macropores33. In further, the positive effects could be strengthened by soil organic carbon. This is because, on the one hand, soil organic carbon could affect the spatial distribution of the root systems by improving soil structure, in particular soil macropores development49,55. On the other hand, soil organic carbon could promote root systems activity and decomposition, resulting in the formation of biological macropores56. The macropores could promote the occurrence of preferential flow and in further increase Ks (Fig. 4a).

Subsequently, an interesting phenomenon that we could not ignore was that the soil water flow traits in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation exerted different influences on the Ks (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3d). The soil water flow ‘networks’ in the preferential flow situation could be treated as gravity-driven convection transport paths, reducing soil water flow blockage and in further increasing Ks3,39,42. Instead, in the soil matrix flow situation, capillary-driven convection process could lead to slow soil water flow through the soil matrix “network”3,42. This is because the soil matrix “network” could enhance more soil water storage by inducing the radial infiltration losses of preferential flow, which resulting in the decrease of Ks5,10. However, the negative relationship was found between soil physical properties and soil water flow traits in soil matrix flow situation (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 10). In fact, the explanation was obvious. The soil matrix flow could be weakened with the increasing facilitation of preferential flow due to the better soil physical properties3,46. On the contrary, root systems could promote soil water flow traits (Fig. 4c). This is because soil water would persistently transport along the root-soil interface with a high pore-water pressure, resulting in the soil water flow into the surrounding soil matrix33. It was also worth noticing that soil physical properties, root systems traits, and soil water flow traits in the low interaction areas showed no significant direct effects on the Ks (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). The possible explanation is that the low interaction areas with more compacted soil particles could be performed as the storage of the byproducts from the high interaction areas12,22. Instead, the sorption ability of the capillary force in these areas could be neglected to some degree3, which results in their weak effects on the Ks. Although root systems showed positive effects on soil water flow traits, the influences of root systems on the surrounding soil matrix activity decreased with increasing distance from the root-soil interface because of a reduction in the radial confining pressure57. Anyway, both soil physical properties and root systems traits could promote the Ks, whether in preferential flow- and soil matrix flow situation (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). However, the effects of soil physical properties on the change in soil water flow traits were different, either positive (preferential flow situation) or negative (soil matrix flow situation). Root systems traits could facilitate soil water flow traits in the two situations (Fig. 4c).

The dual function of root systems and their critical values

In this study, root systems would improve both preferential flow- and soil matrix flow behavior, implying the dual function of root systems (Fig. 4). Obviously, root systems themselves could form connected root preferential channels by displacing soil particles7,29,34 (Fig. 6c), enhancing the occurrence of preferential flow (Fig. 4c–e). However, it is undeniable that the positive effects of root systems on soil matrix flow behavior could not be neglected58,59,60 (Fig. 4c–e). The possible explanation might be that root growth could promote the formation of new pores and increase the connectivity of the dense mesh structures of pores at the root-soil interface61. The dense mesh structure enhances soil total porosity and also soil macroporosity61,62. However, the increase of soil macroporosity indicates a large interfacial area between soil pores and the surrounding soil matrix, allowing more water infiltration into the matrix23. Moreover, some existing pores are preferentially occupied by root systems, causing macropores splitting into micro- or mesopores3 (Fig. 6c). These pores might produce stronger capillary forces and increase soil matrix flow areas63,64.

We found that root content at all dominated stands together contributed to the S-shape curve changes in the probability of soil water flow behavior transfer (Fig. 5c). A hypothesis that there was a critical value of root systems in balancing the soil water flow behavior was self-evident. Here, the critical values of root systems was illustrated (Fig. 5b, c). For the architectural traits of 3D soil water flow paths, RL and RTD were selected as the key indicators driving the transfer from preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior (Fig. 5b). The critical value of RL in our finding was similar to the existing studies15,65, implying that RL below the critical value promotes the development of preferential flow paths by increasing the length of root-channels. However, they also concluded that RL above the critical value, the root systems would entangle and even form a dense root net, directly reinforcing soils, and in final promoting the water transfer towards the surrounding soil matrix61. Similarly, a large RTD could increase the rough surfaces of root systems66, which in further promotes the resistance of soil water flow and the friction between the flow and the rough surfaces. That is, RTD with a higher value could facilitate the accumulation of soil water flow and in further increase the lateral infiltration into the soil matrix7,29. On the contrary, RTD below the critical value has a lower friction between soil water flow and the rough surfaces of root systems, which is insufficient to balance the gravity29,67. In final, the preferential flow dominates the soil water flow behavior.

It is noteworthy that root growth orientation theta and Gini index were selected when considering the morphological traits of 3D soil water flow paths (Fig. 5b). Similar results were reported68. This is because the large root growth orientation theta above a critical value could enhance the lateral development of soil water flow paths, squeezing soil particles and in further inducing the soil water flow along the root channels, infiltration into the soil matrix69. Interestingly, preferential flow might dominate soil water flow behavior as root growth orientation theta was below a critical value (Fig. 5c). The possible explanation is that root systems with a lower growth orientation theta would grow with a more vertical direction within the soil, which results in the formation of vertical root channels68,69. In agreement with the results68, root systems with high unevenness distribution would effectively contact with soil particles, which increases the adhesion between them at the root-soil interface68,70. The adhesion, which corresponds to the soil capillary force, could promote the soil water flow at the root-soil interface infiltration into the soil matrix65. However, the low Gini index indicates an even distribution of root systems, effectively inhibiting the formation of dense root net61,68. That is, the even distribution of root systems could improve the connections between the root channels at the root-soil interface and the existing soil pores3,44, which in further enhances the occurrence of preferential flow (Fig. 5c).

Interestingly, RB and RW could drive the transfer from soil matrix flow- to preferential flow behavior when considering the spatial traits of 3D soil water flow paths (Fig. 5b, c). In agreement with the results of the previous studies7,29, RW could mainly influence the soil water behavior transfer (Fig. 5b). One possible explanation is that fine root systems could form a well-connected root channel network and also have a substantially higher decomposability compared with coarse root systems, improving the connections between existing pores, reducing the clogging of soil water flow paths, and in final inducing a homogeneous preferential flow behavior5,7,71 (Fig. 6d). Another explanation might be that coarse root systems have high strength to shift soil particles due to their low buckling tendency29,72. In particular, coarse root systems could easily insert the soil macropores when they expand radially, causing the formation of more isolated or scattered soil water flow paths58 and resulting in a gradually obvious soil matrix flow behavior. Similarly, root systems could occupy the soil macropores and suppress the cracks and swelling as RB after reaching the critical value, promoting soil matrix flow behavior73. RB below the critical value could induce the homogeneous preferential flow paths (Fig. 5c). This might be explained by root decomposition hypothesis73. Root channels were formed around them as root systems became impoverished, causing the uniform distribution of preferential flow paths73. However, in our study, SRA could drive the transfer from preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior (Fig. 5b, c), which was also dramatically reported74.

With respect to the Dc, RN, RL, RW, RSA, and root coordination number could drive the transfer from preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior (Fig. 5b, c). Consistent with the results64,75, RN below the critical value would promote the occurrence of preferential flow, but RN after reaching the critical value could increase the soil matrix flow (Fig. 5c). One ecological mechanism might be attributed to the pore blockage caused by the root aggregation after reaching the critical value, enhancing the soil matrix flow43,64,75. Another possible explanation is from the hydrophobic behavior of root exudation caused by large number of root systems, resulting in soil pores clogging73,75. However, our results were different from the findings that RN below the critical value would promote the soil matrix flow, but RN after reaching the critical value could facilitate the preferential flow76. This is because that soil structure in forested lands of our study is stable and complex76, which requires a larger RN to change the soil water flow behavior15. Similarly, the ecological mechanism of root coordination number changing the soil water flow behavior is dramatically parallel to the effects of RN. The larger root coordination number, the stronger root branching strength, which could promote the soil matrix flow by anchoring the root systems to the pore walls and fixing soil particles58,59,60,70. Our results indicated that RSA below the critical value could contribute to preferential flow (Fig. 5c). However, RSA mainly promotes the development of soil matrix flow when it is above the critical value. As stated in the studies34,68, RSA below the critical value could enhance the formation of well-connected root channels. Yet, root systems with a higher RSA tend to contact extensively with the surrounding soil matrix, leading to the increase of soil matrix flow areas10,77. As the results we mentioned before, RL and RW after reaching the critical value could drive the transfer from preferential flow- to soil matrix flow behavior, which was reported by the promising results7,15,65.

Implication and limitations

The implications of our results could be profound especially when considering the 3D reconstruction of soil water flow paths. For example, the accurate indicators of the 3D reconstruction could be effectively applied to the soil hydrological models, increasing the models performance78. In further, the virtual indicators of root systems used in the traditional hydrological models were impractical, reducing the complex effects of root intersection and entanglement67,78,79. Therefore, the application of the actual visualization of 3D root systems could better parameterize the models. Notably, the models only considers the positive effects of root systems on preferential flow behavior, which overlooks the dual function of root systems in balancing soil water flow behavior67. In future, the positive effects of root systems on both preferential flow- and soil matrix flow behavior should be fully considered.

Yet, we should not ignore the limited effects of root systems on soil water flow under different soil texture conditions80,81. This is because that different soil texture conditions could directly shape the heterogeneous distribution of root systems, resulting in various soil structures and the density of soil pores80. Compared with sandy soils, clay/loam soils are more likely to provide more chances for root systems to increase soil porosity during their growth. The possible explanation might be that root systems in clay/loam soils tend to displace soil particles, which could create more root channels at the root-soil interface80. Thus, larger critical values of root systems in clay/loam soils were needed to induce the transfer of soil water flow behavior. Conversely, the less compacted sandy soils with a greater number of macropores could lead to lower critical values of root systems. For example, the critical value of RL was 225.36 cm 400 cm−3 in loam soils of our study area and 40.00 cm 400 cm−3 in sandy soils15. Further studies were required to characterize the critical value of root content under different soil texture conditions, and the transfer of soil water flow behavior with increasing root content should be fully considered (if any).

Methods

Study area

The study area is located at the Xiashu Forest Farm of Nanjing Forestry University, Jiangsu Province, Eastern China (32°07′ N, 119°13′ E) (Supplementary Fig. 11). The climate of the study area is subtropical monsoon, with the mean annual temperature of 15.2 °C. The mean annual precipitation is 1055.6 mm. The study area is a hilly and mountainous area, and the main soil type is yellow-brown loam. The dominated vegetation in the study area was nearly completely destroyed in the 1970s. Furthermore, climate change in recent decades has also led to vegetation degradation82,83. From 1970s to 1980s, large-scale afforestation activities had been implemented, and the afforestation area is maintained at 33,000–66,000 m2 per year. After 50 years of vegetation succession, the structure of vegetation community has become more complex, and mixed forests gradually replace the pure forests3,82. At least two vegetation species coexist at any developmental stage of mixed forest stands84. Therefore, in this study, the experimental areas are conducted at the mixed forest stands at forest age 50 years dominated by Quercus acutissima Carruth, Pinus taeda L., and Phyllostachys edulis, respectively (Fig. 1a).

Field dye-tracing experiments

Three 20 × 20 m experimental sites were established at each mixed forests and 3 experimental plots (2 × 2 m) in each area were randomly selected as the three replicates (Fig. 1b). To avoid interference, at least 2 m of open space was left as a buffer zone between the three replicated plots. The location of the dye tracing experiments was the center of each experimental plot. A square steel frame (70 × 70 cm) was vertically pushed into the soils at a depth of 5 cm (Fig. 1b). The litter was removed from the soil surface without damaging the humus layer. According to the statistical analysis and the frequency of extreme rainfall events in Jiangsu Province, a heavy rainfall of 50 mm h−1 is considered as the extreme rainfall event (national standard DB32/T 4430–2022). Therefore, 50 L dye solution (4 g L−1 Brilliant Blue FCF) was homogeneously applied to the soil surface with 2 h using a small rainfall simulator23,27. The selected concentration of the dye solution 4 g L−1 ensured the visibility of water flow within the soils after dilution and adsorption27. After applying the dye solution, the experimental plot was covered with a plastic sheet to avoid precipitation and evaporation. After 24 h dye solution application, vertical soil profiles with intervals of 1.0 cm were prepared from the soil surface to the maximum dye depth (Fig. 1b). Photographs of the vertical soil profiles were captured using a camera3,7. Around the dye areas, soil samples at 0–50 cm soil depth (0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, and 40–50 cm) were collected for laboratory analysis because the maximum dye depth was 40–50 cm at each plot. At each plot, 3 replicate soil cores using cutting cylinders (7.2 cm diameter, 10 cm height) were collected at each soil depth for measuring soil physical properties. 9 soil cores were excavated per soil depth at the three plots. The soil physical properties included are: soil texture (Clay, Silt, and Sand content; %), soil bulk density (SBD; g cm−3), total soil porosity (TSP; %), soil capillary porosity (SCP; %), soil non-capillary porosity (SNCP; %), initial soil water content (ISWC; %), capillary water holding capacity (CWHC; %), and saturated water holding capacity (SWHC; %). Detailed analysis of soil physical properties has been provided22. In addition, extra soil samples were collected to determine the soil organic carbon (SOC; g kg−1) concentrations with an Elemental Analyzer (Elementar vario, Langenselbold, Germany).

Adobe Photoshop CC 2018 and ENVI 5.3 were used to perform geometric correction, background subtraction, color adjustment, histogram stretching, unsupervised classification, and visual inspection22,85. As proposed3,86,87, the dye-stained soil profiles could be further categorized into four parts: preferential flow paths (PFP), high interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix (HIA), low interaction areas between preferential flow and soil matrix (LIA), and no interaction areas (Fig. 1d). In this study, the combination of preferential flow paths and high interaction areas (CPH), the combination of preferential flow paths and low interaction areas (CPL), and the combination of high interaction and low interaction areas (CHL) should be also considered (Fig. 1d). Therefore, six soil water flow patterns, i.e., PFP, HIA, LIA, CPH, CPL, and CHL, were characterized in our study.

3D soil water flow indicators assessment

In this study, a 3D soil water flow modeling software based on the dye-stained images was developed (Supplementary Fig. 12). Firstly, we focused on each pixel in the images to obtain the 3D image reconstruction. The coordinates of each pixel and its corresponding colour in the images should be stored. Secondly, the images could be compressed uniformly to 500 * 500 pixels. To ensure the high resolution of the compressed images, the compressed images should be transformed into the RGB format by the channel-aligned method. The method mainly calculated the Euclidean distance between the actual colour and the goal colour, and further replaced the actual colour with the goal colour based on the minimum distance. Next, the information of each pixel (i.e., location and colour information) in the compressed images was traversaled and stored. Finally, the coordinates of the above 2D pixel (x, y) should be transformed to 3D space (x’, y’, z’) using linear coordinate transformation method. x’ and y’ are equivalent to the x- and y-coordinate of the 2D pixel, respectively, while z’ is calculated by z’ = k·Δz. In this study, we found k range between approximately 1 and 24, Δz is the layer thickness36,88. The method used in this study could verify the consistency of the x- and y-coordinate with actual facts88. By overlaying each image ten times, we could generate 3D point clouds88. A 3D reconstruction in Visualization Toolkit format of soil water flow paths including location and colour information could be obviously illustrated (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1). To align with the dimensions of the polyvinyl chloride (PVC) cylinder (7.2 cm diameter, 10 cm height) used for 3D root systems reconstruction, we performed the cylindrical segmentation for 3D reconstruction of soil water flow paths (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 12). To be specific, the center of the cylindrical segmentation should be determined firstly. The Euclidean distance between all points in the yz plane and the center of the cylindrical segmentation should be calculated. Afterwards, the points located within the cylindrical segmentation could be saved. During these processes, all attributes of these points were preserved.

Meanwhile, we also developed modules in the 3D soil water flow modeling software to analyze each pixel of the images (Supplementary Fig. 12). Firstly, spatial coordinates of each pixel in the 3D soil water flow model were obtained and converted into integer values. Secondly, a 3D matrix container including coordinates of all pixels based on the extremum of the coordinates was constructed by dynamic grid method. Next, the RGB format should be converted into the gray images and further be conducted by the binarization process to generate a 0–1 matrix. In this study, “1” in the matrix represents the effective voxels, i.e., 3D soil water flow paths, and “0” in the matrix represents the soil matrix. Moreover, the interaction between different voxels should also be recognized.

The information of each voxel was traversaled. If the values of the voxels were “1”, depth-first search algorithm could be applied to traversale the 6 nearest neighbours of the effective voxels41. The connected-effective voxels were labelled as the same clusters and further as the connected 3D soil water flow paths41 (Supplementary Fig. 12). If one or more of the 6 nearest neighbours of the effective voxels were lost, the effective voxel belongs to the surface of a cluster. The surface ratio of 3D soil water flow paths (Sw) in this study was defined as follows:

where Cs was the number of the effective voxels which are attributable to the surface of clusters, Ct was the total number of the effective voxels.

The connectivity probability of 3D soil water flow paths (Γw) in this study was proposed as follows:

where ni was the number of the effective voxels contained in the ith cluster, and N was the total number of clusters. The Γw quantifies how well the effective voxels are connected to each other. For example, Γw takes on a value of 1 if all effective voxels are interconnected, conversely, Γw would decrease, even approaching to 0 as the number of isolated voxels (or clusters) increases28,38. In this study, higher Γw indicates enhanced connectivity of the 3D soil water flow paths (Fig. 2e).

The clusters of 3D soil water flow paths were skeletonized by the homotopic thinning algorithm89,90. The algorithm could preserve the voxels per cluster which are farthest from the nearest surface of clusters, ensuring that the reconstructed topology of 3D skeleton is consistent with the actual topology of 3D clusters89. Meanwhile, the convolution algorithm was used to identify the endpoints (nodes with adjacent voxels were 1) and the branch points (nodes with adjacent voxels were ≧ 3) of the reconstructed skeleton. Immediately, the Kruskal algorithm was applied to check the minimum spanning tree (MST) originated from the undirected graph of these skeleton nodes (endpoints+branch points)91. In final, the chord edges of the undirected graph were detected, and then a loop pattern would form by the combination between chord edges and their corresponding shortest path in the MST (Supplementary Fig. 12). The number of the total loops (T) of the reconstructed 3D skeleton is used to calculate the Euler-Poincaré characteristic (χ)38.

where Nc was the number of clusters of 3D soil water flow paths, H was the number of cavities of the clusters, and the value of H was zero in this study. The Euler-Poincaré characteristic density (χn) could reflect the connectivity of clusters at the different scales38. The density could indicate the topological characteristics of the clusters, but was not related to the volume of the clusters38,41. The negative values of χn could indicate that there is a well-connected network of those paths38.

The length ratio of 3D soil water flow paths (Lw) was defined as the proportion of the effective voxels of the reconstructed 3D skeleton to the total voxels39. The tortuosity of 3D soil water flow paths was the ratio of the actual skeleton length and the Euclidean distance between two skeleton endpoints92. The interconnectivity of 3D soil water flow paths was the ratio of the total number of nodes (endpoints+branch points) and the number of the total voxels39. Vw was defined as the proportion of the effective voxels of the clusters in different soil water flow patterns to the total voxels.

In this study, an indicator of 3D soil water flow paths, which could better reflect the degree of 3D soil water flow paths connectivity (Dc), has been proposed. This is because that both the volume and connectivity of those paths could govern soil infiltration39. Although χn above-mentioned could reflect the connectivity to some degree, the connectivity probability (Γw) was more sensitive to large well-connected clusters, which could be better indicating percolation41. The proposed Dc was as follows.

where Vt was defined as the proportion of the effective voxels of the clusters in different soil water flow patterns to the total 3D soil water flow paths.

In addition, the soil water flow paths connectivity in this study was compared with the simulation results of previous common methods, i.e., integral index of connectivity (IIC)93, connectivity index (CI)94, connectivity function (τ)95, and the index of soil water flow connectivity (IWFC)3 (Supplementary Fig. 13).

The box-counting method was adopted to characterize the spatial heterogeneity of 3D soil water flow paths21,40,96. To quantify the fractal dimension of these paths, at first, the boxes with the side length εi were intersected to the 3D point clouds. εi range must be carefully selected based on the physical dimensions of 3D point clouds and the interval between point clouds21. This process could define the maximum and the minimum of εi. Secondly, the geometric progression method was used to accurately determine the side length of the boxes based on the scaling ratio determination. The ration (g) was calculated in the following formulate.

where εmax was the half of physical dimensions of 3D point clouds, εmin was the average interval between point clouds, and n was scaling number.

Then, the side length of the boxes (εi) can be calculated.

With respect to given 3D point clouds, the natural logarithm of the number of the boxes (log[N(εi)]) was plotted against log(1/εi), and a straight line with slope D (i.e., fractal dimension) was simulated by simple linear regression model21.

In this study, the coefficient of determination (R2 > 0.90) was effectively used to support the fractal assumption21.

Multi-fractal analysis was used to make up the insufficiency of the single fractal dimension in characterizing the spatial heterogeneity of 3D soil water flow paths38. Multi-fractal analysis focuses on analyzing how the normalized probability distribution of 3D soil water flow paths changes with different scales97. In this study, the probability mass of these paths (pi(εi)) should be calculated in the following formulate98.

where Ci(εi) was the number of effective voxels in the ith box, Ct was the total number of the effective voxels.

After the quantification of the probability mass, we used the moment method to analyze the multi-fractal spectrum of the probability mass function98. In fact, mass exponent (τ(q)) and generalized dimension (Dq) used in the moment method functions were mainly considered. τ(q) could be characterized based on the following partition function X(q,εi).

Then, a relationship between X(q,εi) and εi was constructed as:

τ(q) could be constructed by the slope between log(X(q,εi)) and log(εi):

For Dq, it could be calculated by the following formulate:

In this study, the q range between approximately −10 and 10, and the interval of q was 140. The Dq could be defined as:

when q = 1, D1 was entropy dimension:

when q = 0, D0 was capacity dimension:

The larger D0-D1, the higher the discrete probability of 3D soil water flow paths spatial distribution.

In addition, the ∆D was obtained to reflect the heterogeneous probability of the generalized dimension spectrum.

The larger the ∆D, the stronger the heterogeneous probability of 3D soil water flow paths spatial distribution.

Besides to the generalized dimension spectrum ∆D, the width of the singularity spectrum (∆α) was also considered to describe the similarity or differences in the local scaling properties of these paths96. The function αq could be determined by Legendre transformation as follows:

where αmax was the max αq and αmin was the minimum αq.

Laboratory soil infiltration experiments

At each dye-stained area, three intact soil cores (7.2 cm diameter, 10 cm height) at each soil depth (0−10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, and 40–50 cm) were collected (Fig. 1f). Soil cores were collected by PVC cylinders. By ponding water at the top surface of each soil core and draining with the bottom of the core open to the atmosphere for 24 h, we kept the soil water content more consistent and saturated among those soil cores.

Soil saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks, cm/min) was determined using the constant water head method based on Darcy’s law65,99,100. The experimental apparatus used for the constant water head method is shown in Fig. 1f. One empty ring knife was fixed on upper of the PVC cylinder with saturated soils, and then water was flowed into the upper empty ring knife using a Marriote bottle to maintain a stable water head of 3 cm. When we detected the first drop of water, water outflow was measured every 2, 3, and 5 min until the outflow rate of the last five values reached a steady state with <5% differences.

where ∆h (3 cm) was the water head; l (10 cm) was the height of the soil cores; Qn/Tn was the water volume permeated from the soil core at a steady state (cm/min); Qn was the water volume (cm3), Tn was time (min); S was the area of the cross section of the soil core (cm2).

3D root systems indicators measurement

After finishing laboratory soil infiltration experiments, the soil cores were placed into a sealed box, wrapped with sponge, and then scanned by X-ray microtomography to obtain the 3D root systems reconstruction (Fig. 1c). Before the scanning, each soil core must be fully wetted to minimize the influences of the variability of soil water content. Industrial X-ray scanning with the resolution of 56 μm, the energy level of 180 kV, the tube current of 160 μA, and the exposure time of 500 ms was used to image and analyze the 3D root reconstruction. A total of 1000 projection images were collected over a 360° rotation. The projection images were further analyzed as follows (Fig. 1c). (1) ROI acquirement: the “Region of Interest” (ROI) tool in ImageJ software was applied to minimize the disturbance during the PVC collection. The area (7.1 cm diameter) in the center of the soil cores was selected101. (2) Filtering & Resampling: the normalization and the 3D median filter plug-ins in the ImageJ software were used to reduce the negative influences of noise and luminance changes. All projection images were resampled using Avizo 9.0 software (Victor Smorgon Group Inc., Australia). (3) Root visualization: the growth method and the threshold method were used to visualize the root systems. The fixed threshold could be applied to distinguish the root systems, soil pores, and the solid phases. After segmentation, the root systems were visualized20. (4) 3D skeletonization: we skeletonized the root systems to characterize the 3D root systems indicators. The indicators mainly include root number, root length, root surface area, root volume, root fractal dimension, root growth orientation theta, root coordination number, and root tortuosity.

In this study, the Gini index was evaluated to imply the unevenness distribution of root systems in the soil cores. We divided the soil cores into three parts evenly, i.e., upper, middle, and lower parts, and then we analyzed the number of root systems at each part. The definition of Gini index is as follows:

where Xi was the root number in the upper, middle, and lower parts, respectively, n was 3, and i was the rank of values in ascending order. Gini ranges between 0 and 1, the larger the Gini index, the more unevenness distribution of root systems in a single part102.

After characterizing the 3D root system indicators, we would wash the root systems from PVC cylinders slightly. To obtain the root biomass (RB, g), root systems were weighted after oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h. Meanwhile, root morphological traits, i.e., specific root length (SRL, cm g−1), specific root surface area (SRA, cm2 g−1), and root tissue density (RTD, g cm−3)70, were calculated as follows:

More details about the formula and classification for the indicators of the 3D root systems traits are given in Fig. 1e and Supplementary Table 5.

Thresholds detection of root content

In this study, according to the results, the 3D soil water flow behavior under different root content could be divided into two types. The first type is soil water flow behavior dominated by preferential flow10. In this situation, appropriate root content within the soils could form an interconnected pore network. The second type is soil water flow behavior dominated by soil matrix flow10. In this process, the root content is too large to promote the connectivity of soil pores. In our study, the role of preferential flow would dominate the soil water flow behavior when the root content was less than a critical value; otherwise, soil matrix flow would dominate. When the root content is less than the critical value, the contact area between the soil water flow and the soils is reduced, causing an acceleration of the soil infiltration, a higher Ks, and the occurrence of preferential flow. Above the critical value, large root content would block the soil pores development, leading to a decrease in soil porosity and Ks. In final, the limitation for the occurrence of preferential flow was reached and the promotion for the soil matrix flow.

A regression analysis has been widely used for the threshold detection because of the lower amount of data requirements and the effective determination of the threshold103. To detect the “threshold”, the non-linear regression analysis was used to simulate the changes in the role of preferential flow and soil matrix flow with increasing soil depth. To further detect the “threshold” phenomena104, we performed an accurate judgement of 3D soil water flow behavior by constructing a series of binary values (1, 0). During the judgement, “1” indicated a transfer from preferential flow dominated to soil matrix flow dominated, while “0” implied 3D soil water flow behavior dominated by preferential flow. To determine the critical value at which root content could induce the transfer, we determined the probability of the transfer and used the logistic regression analysis for the binary values. In this study, the critical value was defined as the point where the second derivative of the fitted logistic regression curve was zero (i.e., the inflection point)105.

Data analysis

Prior to subsequent statistics, data from the 9 soil cores for each soil depth at each site were averaged to avoid within-plot pseudoreplication106,107. The mixed-effects models were performed on 3D root systems using the lmer function of the “nlme” R package. We treated the soil depth as a fixed effect and the experimental plots as random effects (the experimental plots were already considered as potential random effects during the experimental design)108. Residual normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s Test) were verified. When assumptions were violated, the data were log-transformed. For indicators of root systems showing significant soil depth effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons between soil depths were conducted using Bonferroni-adjusted linear contrasts through the “emmeans” R package. A generalized additive model was used to investigate the non-linear relationship between Γw and Vw. We selected cubic regression splines as smoothing functions to fit the data curvature variations (basis functions k = 15). Parameters were estimated via restricted maximum likelihood to mitigate estimation bias109. The indicators of 3D water flow traits in different patterns were grouped in clusters using the agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis110.