Abstract

Focused groundwater recharge, the concentrated infiltration of water through surface features including streams, depressions, or fractures to the water table, is accepted as the dominant recharge mechanism in arid climates. As climates become increasingly arid, groundwater recharge is expected to shift towards focused mechanisms. Yet the magnitude of focused recharge, its spatial distribution and controls across climate zones remain poorly characterised at the continental scale. Here, we compare historical rainfall tritium with >1700 groundwater tritium measurements to assess the likelihood of focused recharge across the Australian continent, providing important context for water resources management, with global implications. 46% of bores assessed show evidence of focused recharge, suggesting that conventional recharge estimates based on diffuse mechanisms may substantially underestimate total recharge. We show that fractured rock and perennial watercourses are the main landscape features that strongly influence the likelihood of focused recharge. While focused recharge is most common in arid regions, it also occurs in wetter climates where fractured rock enhances subsurface connectivity. As aridity and climate variability intensify, understanding the landscape-climate interactions that enable focused recharge, and how shifts in energy and water availability alter the role of groundwater in the water cycle, will be critical to sustaining groundwater resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Freshwater resources are under increasing stress due to changes in climate conditions1,2, contamination3,4, and overextraction near groundwater-dependent communities5,6,7. As rainfall becomes increasingly variable e.g.8,9,10, groundwater resources are becoming even more critical for sustaining fresh water supply11. With increasing aridity projected due to climate change, groundwater recharge is expected to occur more via focused recharge (e.g., indirect) and less via diffuse (i.e., direct) mechanisms12,13,14. In arid and semi-arid climates, diffuse recharge is often limited by the high evapotranspiration rates that significantly reduce the direct infiltration of rainfall through the unsaturated zone to the water table e.g.15,16.

Focused recharge occurs when infiltrating surface water reaches the water table via preferential pathways or concentrated surface features, rather than uniformly across the land surface. Focused recharge encompasses both localised processes, where water infiltrates through small-scale features, e.g., topographic depressions or geological structures such as joints, cracks and fractures17, and indirect processes, where recharge occurs via surface water features like streams and lakes14,18. Well-established conceptual representations of diffuse and focused recharge can be found in the literature, including streamflow-driven focused recharge (see Fig. 1 in Meixner et al.19), karst-related focused recharge (Figure 4 in Hartmann et al.20), and mountain-system recharge (Fig. 1 in Armengol et al.21). Focused recharge is generally thought to be the dominant recharge mechanism in arid and semi-arid climates13,14,18,22. Over the past four decades, considerable attention has been given to understanding groundwater recharge in arid and semi-arid regions e.g.16,22,23,24,25,26,. Continental-scale recharge assessments, e.g.27,28, have demonstrated that global hydrological models systematically underestimate groundwater recharge compared to field estimates of recharge, particularly in arid regions. High uncertainty in recharge estimates is a key factor underlying these discrepancies and contributes to the large differences observed among global groundwater model outputs, e.g.29. While detailed studies in Africa e.g.30, confirm the dominance of focused recharge in arid climates, the extent at which focused recharge contributes to total recharge across different climate zones and landscapes remains unclear globally, including in Australia. Despite numerous groundwater recharge investigations in Australian arid and semi-arid zones e.g.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, few explicitly quantify or emphasise focused recharge processes e.g.41,42,43,44,. Therefore, a clearer understanding of focused recharge is needed, as it underpins the connections between groundwater and surface water within the hydrologic cycle. Strengthening this understanding will improve the representation of recharge processes in models, leading to more reliable predictions of groundwater availability and sustainability under future climate and land-use change.

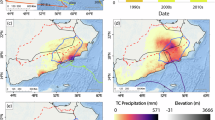

a Map of calculated groundwater-to-rainfall tritium ratios (3HG/3HP5), with locations of observed and interpolated rainfall tritium time series. Insets show zoomed-in views of selected regions: b Perth (Western Australia), c Darwin (Northern Territory), d Lower Burdekin (Queensland), and e Cobram (Victoria). f Conceptual time-series of annual rainfall tritium (3HP) decaying over time since peak tritium activities during nuclear-testing, showing the 5-year mean rainfall tritium (3HP5), groundwater tritium (3HG), and the equation for calculating 3HG/3HP5. g Relationship between groundwater depth in metres below ground surface (mbgs) and 3HG/3HP5, with points coloured by the likelihood of focused recharge (blue = high and grey = low) and fitted exponential decay curve.

Isotopic tracers in groundwater, including tritium, are widely used to estimate recharge rates in relatively young groundwaters (years to decades old) e.g.45,46,47,48, and generally inform the understanding of recharge processes of an aquifer e.g.49,50,51. In the southern hemisphere, tritium is a particularly effective tracer because post-nuclear testing atmospheric tritium activities were much lower than those in the northern hemisphere and have since exponentially decayed, returning close to pre-nuclear testing levels in both the atmosphere and rainfall52. The lower tritium activities in the southern hemisphere enables clearer distinction between modern and older groundwater recharge, allowing confident interpretation of tritium-based groundwater ages in Australia. Tritium, used in conjunction with carbon-14, has also revealed the vulnerability of ‘fossil’ (groundwater recharged >12,000 years ago) groundwaters to modern contamination, attributed to preferential flow and leakage along bore infrastructure, e.g.53,54. Subsequent studies have shown that groundwater pumping can further enhance vertical leakage e.g.55,56. However, these studies primarily focused on vertical mixing processes and did not explicitly examine focused recharge (e.g., leakage from watercourses or topographic depressions) as a mechanism for transmitting modern recharge to greater depths. Thus, links between focused recharge, its related landscape controls (e.g., fractures or access to watercourses) and its ability to transmit modern recharge to the deeper subsurface warrant further investigation.

We present a groundwater tritium dataset containing data from 1734 bores across Australia, compiled from a broad range of sources (see Table S1). We assess the likelihood of focused recharge by comparing groundwater tritium activities (3HG, TU) with rainfall tritium activities (3HP, TU)52,57 and examining relationships with factors that may facilitate focused recharge. Using spatial datasets, such as distance to perennial and ephemeral watercourses, fractured rock regions, and alluvium (Fig. S4a–c), we evaluate the role of landscape features in promoting focused recharge across different climate zones (Fig. S4d), but especially dryland conditions. By assessing where focused recharge is likely to be occurring, we improve the understanding of recharge processes across Australian climate zones. The results are also relevant to regions with similar climatic and landscape conditions globally. The advantage of Australia being in the southern hemisphere enables clearer interpretation of focused recharge compared to regions where atmospheric tritium remains elevated, nonetheless providing a framework applicable to recharge studies and hydrogeological assessments worldwide. The methodology used here provides important context on the likelihood of the occurrence of focused recharge, which can have major implications for water resource management.

Results

Widespread evidence of focused recharge across Australia

To identify evidence of focused recharge, we calculate the groundwater-to-rainfall tritium ratio (3HG/3HP5; Fig. 1f). The rainfall tritium (3HP5) represents a 5-year mean of rainfall tritium activity whereas groundwater tritium is measured at a single point in time (3HG; see Fig. 1f and “Methods” for details). The 3HG/3HP5 varies markedly across Australia (Fig. 1a) and within regions, such as the Perth area (Fig. 1b), with additional regional patterns shown in Fig. 1c-e.

A relatively high 3HG/3HP5 suggests that recharge occurred recently, before radioactive decay could reduce 3HG activities. We then fit an exponential decay curve with depth anchored at a 3HG/3HP5 of 1.0 (Fig. 1g), incorporating a conservative buffer below the curve to account for shallow-depth bias due to shorter residence times and reduced decay. Bores plotting to the right of the buffered curve (blue dots) were classified as high-likelihood focused recharge, while those to the left (grey dots) were classified as low-likelihood (Fig. 1g). We filtered our dataset to exclude bores with sample depths >250 m below ground surface (mbgs), as these samples did not exhibit detectable 3HG, and also removed bores outside the coverage of spatial datasets (see Fig. 1g and “Methods” for details). To evaluate how focused recharge varies with depth, we conduct a systematic assessment of 3HG/3HP5 across defined depth intervals.

Across Australia, 3HG activities range from unquantifiable values (often <0.07) to 19.8 TU, with a mean of ~1.0 TU, while 5-year mean annual 3HP activities (3HP5) range from 1.1 to 42.3 TU, with a mean of ~4.4 TU. 3HG/3HP5 range from <0.001 to 2.01, with a mean of ~0.25 (n = 1668; Fig. 1g). We identify high likelihood of focused recharge in 761 bores (~46%), which provides strong empirical evidence that focused recharge is a geographically widespread process. The 3HG/3HP5 for high-likelihood focused recharge bores range from 0.04 to 2.01, with a mean of 0.44 and a median of \({0.40}_{0.18}^{0.62}\) (\({{median}}_{Q1}^{Q3}\); n = 761) while low-likelihood bores range from <0.001 to 0.84, with a mean of 0.08 and a median of \({0.02}_{0.008}^{0.1}\) (n = 907). Although some high-likelihood bores exhibit relatively low tritium ratios (e.g., ~0.04), such values can occur at greater depths where tritium would typically be absent under diffuse recharge conditions. In these cases, even a small detectable tritium ratio represents an anomalously elevated value relative to depth, indicating rapid transmission of modern recharge through focused recharge processes rather than slow matrix flow. 3HG/3HP5 are highest in shallow (<25 mbgs), high-likelihood focused recharge bores with a mean of 0.59 and a median of \({0.54}_{0.40}^{0.76}\) (n = 299). At greater depths (e.g., >50 mbgs) 3HG/3HP5 for high-likelihood bores remain elevated, albeit at lower values, with a mean of ~0.3 and a median of \({0.18}_{0.08}^{0.41}\) (n = 258). 3HG/3HP5 are substantially lower in shallow, low-likelihood focused recharge bores (<25 mbgs) with a median of \({0.09}_{0.02}^{0.21}\) (n = 504), and deeper bores (>50 mbgs), with a median of \({0.009}_{0.006}^{0.013}\) (n = 240).

The persistence of elevated 3HG/3HP5 at depths >50 mbgs suggests that focused recharge is not merely a shallow process but can contribute to deeper aquifer replenishment. Elevated tritium ratios observed at depths >50 mbgs are commonly associated with bores in fractured rock aquifers, where secondary permeability facilitates rapid vertical transport of recharge to depth, consistent with observations from other highly fractured systems globally, e.g.58. This has important implications for water resource management, as it indicates that even deeper groundwater systems may be more connected to modern recharge processes than previously assumed. However, it is also possible that elevated 3HG/3HP5 may reflect issues with poor bore construction, such as long screened intervals that allow mixing of water from different aquifer layers, or poorly sealed casings that create artificial pathways for tritium to reach greater depths53,59. In some cases, such as in fractured rock settings or coarse-grained soils, focused recharge can contribute to a significant proportion of the total recharge to a system13. Our findings suggest that focused recharge processes, such as those associated with river leakage and recharge through secondary porosity, play a more important role than has been considered in global-scale hydrological models60, which has major implications for water resources management. While some models omit focused recharge entirely e.g.61, others include simplified components such as river- or lake-groundwater interactions to approximate these processes e.g.62,63. More recent approaches have incorporated spatial datasets identifying recharge-prone features, such as karst regions, to parameterise enhance recharge rates e.g.64. However, these models typically do not resolve discrete features like sinkholes or fractures, limiting their ability to represent the heterogeneity of focused recharge. These results support the interpretation by Berghuijs et al.27, who attributed the significant underestimation of recharge in global hydrological models to their coarse resolution. Such models often fail to distinguish between recharge and discharge zones and overlook smaller-scale preferential flow pathways that drive focused recharge.

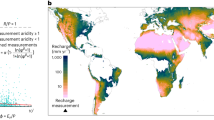

Landscape features are key drivers of focused recharge

To investigate how landscape features influence the likelihood of focused recharge, we use a three-stage approach. First, each bore is evaluated against five landscape feature criteria commonly associated with focused recharge14,17,18. We assess whether bores are: (1) located in a fractured rock aquifer region, (2) screened within or overlain by alluvium, (3) screened within or overlain by carbonate (used as a proxy for karst features; further details in “Methods” subsection: Data analysis), (4) within 500 m of a major perennial watercourse, or (5) within 500 m of a major ephemeral watercourse (see “Methods” subsection: Hydrogeological and climatic spatial datasets). These features are assessed against 3HG/3HP5 residuals individually for bores classified as high-likelihood focused recharge (Fig. S1). Secondly, a Pearson chi-square test is used to statistically compare the relative proportions of bores meeting each of the five landscape criteria between the high- and low-likelihood groups, as defined by their 3HG/3HP5 ratio (Fig. 2). This approach tests whether certain landscape features are more common among bores showing evidence of focused recharge, rather than just examining their overall frequency in the dataset. Thirdly, a landscape score (ranging from 0 to 5) is assigned to each bore based on the number of landscape criteria satisfied. This approach assesses the relationship between landscape features and 3HG/3HP5 residuals (i.e., distance from the fitted exponential curve; Fig. 1g, Figs S2 and S3).

“None” denotes bores that meet none of the five landscape feature criteria. Pearson chi-square test pvalues are presented above the bars (* denotes p < 0.05 and higher proportion of high-likelihood than low-likelihood focused recharge bores in the landscape control category). Counts (n) are presented below the bars.

High-likelihood focused recharge bores in carbonate exhibit the highest median 3HG/3HP5 residuals (\({0.34}_{0.07}^{0.47}\); n = 13), followed by bores located <500 m of perennial watercourses (\({0.27}_{0.15}^{0.44}\); n = 88; see box plots in Fig. S1). In contrast, bores located <500 m of ephemeral watercourses, bores in fractured rock, and bores in alluvium have three of the lowest median residuals (\({0.20}_{0.08}^{0.29}\),\({0.22}_{0.11}^{0.42}\),\({0.21}_{0.11}^{0.38}\), respectively; n = 88, 245, 197; Fig. S1). We note that for ephemeral watercourses and carbonate, the dominance of high-likelihood focused recharge bores is not statistically significant, as later shown, and should be interpreted with caution. While it is not surprising that focused recharge in carbonate geology generally reaches deeper depths than in alluvium, the lower mean 3HG/3HP5 observed for bores near ephemeral streams is somewhat surprising, given the assumed role of these waterways in focused recharge in the arid zone, e.g.12,13,14,65. The lower 3HG/3HP5 for bores near ephemeral streams may reflect the unfavourable conditions for recharge occurring in more arid climates. In these settings, higher evapotranspiration reduces infiltration, and recharge is delayed until precipitation thresholds are exceeded and soil moisture deficits are sufficiently overcome, enabling direct infiltration or runoff generation that supports focused recharge e.g.30,66. Tritium activities may also reflect complex vadose zone processes, including minor evapoconcentration during dry periods and subsequent dilution upon mixing with older groundwater or flushing during episodic recharge events, depending on aquifer mixing and recharge frequency.

Pearson chi-square tests reveal statistically significant associations between focused recharge likelihood and three landscape controls: fractured rock, alluvium, perennial watercourses, and instances where the bore met none of our landscape feature criteria (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). A larger proportion of bores that meet the fractured rock and perennial watercourse criteria are classified as high-likelihood (n = 245 and 88, respectively; Fig. 2) compared to low-likelihood (n = 170 and 70, respectively), indicating that these features are positively associated with focused recharge. In contrast, a greater proportion of low-likelihood bores fall into the “none” category (n = 440 and 331 for low- and high-likelihood, respectively). These bores meet none of the five landscape criteria, indicating that the absence of commonly recognised landscape controls reduces the likelihood of focused recharge (Fig. 2). A greater proportion of low-likelihood bores were similarly observed in the alluvium category (n = 286 and 197 for low- and high-likelihood, respectively). The lack of association between alluvium and focused recharge likely reflects the inherently high variability in alluvium material composition. Alluvium settings in Australia are often characterised by complex stratigraphy, with varying degrees of clay content and layering that can significantly reduce vertical permeability and limit infiltration e.g.12,67. These findings reinforce the general importance of fractured geological settings and perennial surface water-groundwater connectivity in facilitating focused recharge. Interestingly, 326 out of 738 ( ~ 44%) bores where focused recharge is highly likely, meet none of the five assessed landscape criteria (Fig. 2). Other landscape controls, such as localised topographic depressions, presence of lakes or dams, minor watercourses, ephemeral drainage lines, or small-scale zones of high hydraulic conductivity, fall within our definition of focused recharge but were not included in this assessment. These additional landscape features may play important roles at local scales. Moreover, the relatively low-resolution mapping products used to identify geology (e.g., national surface geology map for carbonate and alluvium, and hydrogeological map of Australia for fractured rock) likely also limit our ability to detect smaller-scale features that facilitate focused recharge. In addition, several non-landscape factors may influence 3HG/3HP5 ratios and bore classification, including poor bore construction that creates artificial pathways for tritium to reach greater depths53, long screened intervals that mix waters of different ages59, and older groundwater samples with higher analytical limits of reporting. Other factors such as land cover, irrigation-induced recharge, and groundwater extraction may also alter 3HG/3HP5 ratios through enhanced infiltration or mixing but were not considered in this study. Future research could aim to distinguish focused recharge from anthropogenic influences on vertical flow by examining contaminants and other co-tracers, e.g.54,68, land- and water-use, or by assessing the influence of deep or poorly constructed bore infrastructure on preferential flow.

Among the bores assessed as having a high likelihood of focused recharge, landscape scores range from 0 to 3, with no bores meeting 4 or 5 criteria (Fig. S3). Interestingly, high-likelihood bores with the maximum landscape score of 3 have a higher median residual (\({0.28}_{0.17}^{0.44}\); n = 23) compared to those with a score of 1 (\({0.21}_{0.10}^{0.39}\); n = 287) or 2 (\({0.22}_{0.10}^{0.41}\); n = 120), which exhibit very similar medians and interquartile ranges. High-likelihood bores with a score of 3 also tend to have a relatively shallow median sample depth (\({15.2{m}}_{11.0{m}}^{32.7{m}}\); n = 23), consistent with their clustering near the fitted exponential decay curve (Fig. S3). This clustering likely reflects the dominance and shallow bias of bores screened in alluvium in this group. Bores with landscape scores of 2, located near perennial watercourses and underlain by either alluvium or fractured rock, exhibited the highest median residuals (\({0.28}_{0.15}^{0.46}\); n = 81, \({0.30}_{0.19}^{0.36}\); n = 18, respectively), reinforcing the role of perennial surface water as a strong control on focused recharge e.g.69,70. In contrast, combinations involving bores adjacent to ephemeral watercourses consistently exhibit lower median residuals, regardless of the co-occurring feature (i.e., combined with fractured rock or alluvium; \({0.23}_{0.16}^{0.48}\); n = 20, \({0.20}_{0.11}^{0.30}\); n = 28, respectively), mirroring the trend observed when bores in the ephemeral category were assessed individually. These findings suggest that ephemeral watercourses, even when located in favourable geology like alluvium or fractured rock, may contribute less to focused recharge than perennial systems. This likely reflects the stronger hydrological constraints in ephemeral systems as previously mentioned.

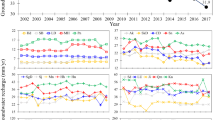

Focused recharge is more likely in arid climates

To assess how aridity influences the likelihood of focused recharge, we group bores into three aridity zones (see definition in Methods subsection: Hydrogeological and climatic spatial datasets, and Figs. S4d and S5): (1) humid and dry subhumid, (2) semi-arid, and (3) arid and hyper-arid, in addition to the landscape controls defined earlier (see Table S4 for bore counts of each subgroup). We use Pearson chi-square tests to examine how high- and low-likelihood focused recharge bores are distributed among the three aridity zone categories (Fig. 3).

Aridity zones are grouped into three categories: (1) humid and dry subhumid (P/PET ≥ 0.5), (2) semi-arid (P/PET from 0.2 to <0.5), and (3) arid and hyper-arid (P/PET < 0.2). Landscape controls are arranged in descending order based on dataset size. H and L denote high- likelihood and low- likelihood focused recharge, respectively. Landscape controls and aridity zones that promote focused recharge are marked in bold and with an asterisk (*). The orange box highlights statistical significance and higher proportion of low likelihood compared to high likelihood focused recharge bores that do not meet any landscape criteria and in the arid zone (arid and hyper-arid). The blue box highlights statistical significance and higher proportion of high likelihood compared to low likelihood focused recharge bores that meet multiple landscape criteria and are in the arid zone (arid and hyper-arid). Where sample sizes were insufficient for a Chi-square test, a Fisher’s exact test was used; these cases are denoted by a hash symbol (#) next to the pvalue. Bore counts for each subgroup are provided in Table S4.

Our results indicate that focused recharge in arid and hyper-arid zones is more likely to occur when favourable landscape features are present (Fig. 3). Bores in arid and hyper-arid regions satisfy the most landscape criteria (alluvium, perennial and ephemeral) and have a statistically significant association with high-likelihood focused recharge (blue box in Fig. 3). Bores near perennial watercourses in arid and hyper-arid regions exhibited significantly higher 3HG/3HP5 residuals (\({0.38}_{0.18}^{0.56}\); n = 29) compared to bores in alluvium or near ephemeral watercourses (\({0.19}_{0.08}^{0.36}\); n = 63 and \({0.15}_{0.07}^{0.20}\); n = 21, respectively). These results underscore the effectiveness of perennial water features in enabling focused recharge under extreme climatic conditions.

Conversely, in arid and hyper-arid climates, the likelihood of focused recharge is low when bores are not situated near any of these five landscape features, highlighting the importance of these features in enabling recharge under extreme conditions (orange box in Fig. 3). Focused recharge is also more likely to occur in semi-arid, humid, and dry subhumid zones when fractured rock is present, whereas this association is not observed in arid and hyper-arid zones (Fig. 3). The absence of a clear relationship in the driest climates likely reflects the limited number of bores located in fractured rock in these zones, with only a small fraction of the total dataset (e.g., 8 out of 102 high-likelihood and 6 out of 212 low-likelihood bores) represented, rather than an absence of the process itself. In the semi-arid zone, focused recharge is particularly associated with proximity to perennial watercourses, although this relationship is only marginally significant (p = 0.047).

In contrast, bores in humid and dry subhumid zones and associated with alluvium have a statistically significant association with low-likelihood focused recharge (Fig. 3). This suggests that the role of alluvium in wetter regions may be less effective or more associated with slower, diffuse recharge processes. This complies with previous findings that a large portion of rainfall is taken up by vegetation in more humid regions where rainfall volumes are higher71, and where fractured rock may facilitate deeper recharge pathways that potentially bypass surficial processes such as evapotranspiration72. This interpretation is supported by the relatively high 3HG/3HP5 residuals in bores associated with alluvium (\({0.34}_{0.24}^{0.42}\); n = 24) which are comparable to those in perennial watercourse bores (\({0.36}_{0.30}^{0.42}\); n = 16) and higher than in fractured rock bores (\({0.26}_{0.16}^{0.42}\); n = 97).

While the importance of focused recharge in arid regions has been widely acknowledged e.g.13,16,30, there has been little empirical validation of this process at large scales. Our national-scale study, based on tritium data from >1700 bores across Australia, quantitatively demonstrates that surface water features, particularly perennial watercourses, are drivers of focused recharge in arid regions. In contrast, we provide evidence that fractured rock plays a dominant role in supporting focused recharge under wetter climatic conditions; however, the apparent lack of focused recharge dominance in arid and hyper-arid fractured rock settings may be influenced by sampling constraints rather than an absence of the process. Importantly, we show that focused recharge is not confined to shallow systems and can contribute meaningfully to deeper aquifers given the existence of appropriate landscape features. This highlights the role of focused recharge in connecting surface water and groundwater, a critical process of the hydrologic cycle—especially in the drylands. However, some uncertainty remains, particularly in cases where deep tritium activities may reflect preferential flow due to legacy bore infrastructure (e.g., poorly sealed or long-screened bores), rather than natural recharge processes. Future research through the analysis of contaminants and other co-tracers (e.g., noble gases) and bore construction data could help disentangle these effects. These findings provide a practical framework for identifying landscape settings conducive to focused recharge, offering valuable process understanding-based guidance for groundwater management and predictive modelling that are transferable to other regions with similar climates and landscape features. While the analysis presented here is specific to Australia, and application of tritium in the northern hemisphere may be more challenging due to higher atmospheric tritium activities, the spatial datasets and methodology employed are globally accessible, enabling similar assessments elsewhere. Ensuring the sustainable use of groundwater is a critical global challenge73,74. Groundwater systems are complex and often poorly understood, making the impacts of depletion difficult and costly to reverse75,76. Increasing climate variability and aridity are intensifying reliance on groundwater resources, leading to overextraction5,6,7, declining water quality3,4, and growing competition for access77. This research provides new insight into where and under what conditions focused recharge occurs in Australia, which may help inform understanding of recharge pathways in data-poor regions. Understanding these processes is essential for improving groundwater management, helping to identify where monitoring of recharge could be conducted or enhanced, and developing targeted, sustainable strategies to secure long-term water availability for communities and ecosystems dependent on groundwater.

Methods

Groundwater and rainfall tritium datasets

Tritium (3H) is a radioisotope of hydrogen, produced naturally in the upper atmosphere, with a half-life of 12.32 years78. While 3H typically occurs naturally in rainfall at concentrations of 1–3 TU in Australia, concentrations increased during various periods of nuclear testing (mainly in the 1950s and 1960s). 3H concentrations in the atmosphere peaked in 1965, with rainfall concentrations reaching between 36.6 and 110.2 TU in Australia52. The short half-life of 3H, together with the lower concentrations in the southern hemisphere78, allows the mean residence time of groundwaters that recharged over the past several decades to be estimated from a single 3H measurement79,80,81.

Groundwater tritium data (3HG) were collated from 59 papers, 10 reports, three theses, and one data repository (Table S1). A large range of quantification or detection limits for tritium were reported in the 3HG data, ranging from 0.02 to 0.7 TU. Where 3HG activities were indicated as being below detection, all values were converted to 0.0225 TU (half of 0.045 TU—the geometric mean of reported quantification limits) for consistency. Bore or sample ID, sample date, latitude, longitude, and screened mid-point of bore were also extracted from the references. Where a sample date range was provided in the reference, an average of the range was calculated and used as the sample date for all bores. Where a month and year was given, the 15th was taken as the day. If no indication of the date or month and year of sampling were given, two years prior to the date of publication was used as the sample date for all bores. Where only eastings and northings were provided in the reference, the Geoscience Australia geodetic calculator grid coordinate application batch processing tool82 was used to convert coordinates to latitudes and longitudes. Where no coordinates were provided, map figures from the reference were digitised to extract approximate coordinates for the bores. Bore logs supplied by the National Groundwater Information System (NGIS) were downloaded from the Australian Groundwater Explorer83 to provide geolocations, bore hole depths, drilled depths, and screened interval depths. Where the mid-point of the bore screen was not provided in the reference a depth was assigned to each bore. The depth assigned to each bore was applied following the approach outlined in ref. 15, in the following order of preference: Screen mid-point depth, sample depth, bore depth and hole depth.

Rainfall tritium data (3HP) comprises amount-weighted annual mean tritium activities (TU), obtained from Tadros et al.52. It includes data from 15 monitoring stations distributed across Australia, covering the period 1960–2011. The locations of these stations are shown in Fig. 1a (open diamonds), with full metadata provided in Table S2. 3HP measurements were carried out as described in Tadros et al.52. Briefly, tritium in the composite monthly rainfall samples were measured at Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) using liquid scintillation counting, following distillation and electrolytic enrichment. The measurement uncertainty is ~±0.15 TU.

3HP were calculated using the formula:

Where xi is the monthly tritium activity (TU), wi is the corresponding monthly rainfall amount (mm), and i = 1 to 12 represents the months from July to June, following Taylor and Fletcher84.

Hydrogeological and climatic spatial datasets

Three spatial datasets were used in our study to extract landscape features relevant to the assessment of focused groundwater recharge, including the surface geology of Australia85, hydrogeology map of Australia86, and national surface hydrology dataset87.

Surface geology attributes (Layer name: GeologicUnitPolygons1M.shp, Field name: LITHOLOGY) and principal hydrogeology attributes (Layer name: hydrogeology.shp, Field name: TYPE) were extracted from polygons from Raymond et al.85 and Brodie et al.86, respectively, at groundwater bore locations using the point sampling tool in QGIS. Extracted surface geology attributes were categorised into eight simpler groups, including igneous/metamorphic, sedimentary carbonate, sedimentary non-carbonate, regolith, aeolian, alluvium, colluvium, and lacustrine. Extracted principal hydrogeology attributes were categorised into either fractured rock or non-fractured rock aquifers.

We extracted major perennial and non-perennial (ephemeral) watercourses from the national surface hydrology dataset87 based on their hierarchy and flow permanence attributes. These linear features were converted to regularly spaced point features at ~100 m (0.001° resolution). The converted watercourse points and groundwater bore points were reprojected to a common projected coordinate system (GDA94/Australian Albers, EPSG:3577) to ensure accurate distance calculations. Distances from each groundwater bore to the nearest major perennial and ephemeral watercourse were then calculated using the distance to nearest hub tool in QGIS.

The aridity-based climate zone, was determined for each bore location using the long-term aridity index spatial dataset from Lee et al15., which is based on precipitation (P) and potential evapotranspiration (PET) data spanning from 1911 to 202088,89. The aridity index was calculated by dividing annual precipitation by evapotranspiration (P/PET). Climate zones were calculated according to ranges of aridity index presented in United Nations Environment Programme90: hyper-arid (P/PET < 0.05), arid (P/PET from 0.05 to <0.20), semi-arid (P/PET from 0.20 to <0.50), dry subhumid (P/PET from 0.50 to <0.65) and humid (P/PET ≥ 0.65).

Data analysis

To assess the likelihood of focused recharge, we calculated the groundwater-to-rainfall tritium ratio (3HG/3HP5), defined as the measured groundwater tritium activity (3HG; in TU) divided by the local 5-year mean annual rainfall tritium activity (3HP; in TU) at each bore location. A 5-year averaging window was used to calculate mean rainfall tritium because assessment of the mean absolute change in groundwater-rainfall tritium ratios for cumulative averaging periods ranging from 1 to 10 years, indicated that beyond approximately five years the mean absolute change stabilised to within ~2% (see Table S6 of the supporting information). This indicates that a 5-year period captures the majority of interannual variability while providing a stable and representative estimate of rainfall tritium activity. Annual time series of 3HP at 15 rainfall stations52 were gap-filled where data was missing. Owing to the exponential decay of 3H shown in Fig. 1f, gap filling was conducted by fitting an exponential curve to 3HP from 1985 to 2012 (except Bundaberg, Charleville, Claredale, Ryde, and Toowoomba, which required data from 1980 to 2012 due to larger gaps in the data). After the preliminary gap-filling, 3HP from Tadros et al.52 were extended beyond 2011 by sampling the gridded predicted rainfall tritium value from Terzer-Wassmuth et al.57 and extracting the value from the pixel in which the bore is located in (except for Mackay which required averaging the nearest three pixels as the Mackay station was not located in any pixels). The value sampled was repeated for all years from 2012 to 2024. A visual representation of the rainfall tritium gap-filling and extension process is provided in Fig. S6.

Time series for six new tritium rainfall stations were interpolated using inverse distance weighting on existing data from the 15 rainfall stations. These new rainfall stations were placed in areas where groundwater tritium data was >500 km away from any of the original 15 rainfall stations. The latitude and longitude for the observed and interpolated tritium rainfall stations are provided in Table S2 and Table S3, respectively. The closest observed or interpolated rainfall station was determined for each bore location using nearest-neighbour spatial analysis in QGIS. The extended 3HP dataset (2012–2024) for various observed and interpolated time series were validated against independent 3HP measurements collected during the extended period, from Melbourne, Darwin, Brisbane, and Katherine79,91,92,D. Irvine, pers. comm.. Absolute residuals between predicted and measured values were acceptable, not exceeding 20%, with a mean residual of 14%, which is in line with global validation conducted by Terzer-Wassmuth et al.57.

We first removed bores with sample depths >250 mbgs as these samples typically did not exhibit detectable 3HG. We also excluded bores located outside the spatial coverage of key datasets used in our analysis (e.g., aridity index-based climate zones and landscape feature layers). We then plotted 3HG/3HP5 against bore sample depth (mbgs) and fitted an exponential decay curve to represent the expected decline in 3HG/3HP5 with depth under typical diffuse recharge conditions. The decay curve was anchored at a 3HG/3HP5 of 1.0 at the ground surface (sample depth of 0 mbgs). We calculated the residual (i.e., the difference between the observed 3HG/3HP5 and the value predicted by the exponential decay curve) for each bore. To separate high- and low-likelihood focused recharge bores, we applied a conservative threshold corresponding to the 55th percentile of the residual distribution. Although all bores that plot to the right of the decay curve in Fig. 1g could be considered high-likelihood focused recharge bores, this threshold provided a balanced and conservative classification, resulting in a lower count of high-likelihood bores than low-likelihood bores (761 and 907 bores, respectively; see Table S5). Bores with residuals greater than the threshold, i.e., bores that plot to the right of the buffered curve (Fig. 1g), were classified as high-likelihood focused recharge bores, while those with residuals at or below the threshold were classified as low-likelihood.

Bores were evaluated against five landscape feature criteria commonly associated with focused recharge. We assessed whether bores are: (1) located in a fractured rock aquifer region, (2) screened within or overlain by alluvium, (3) screened within or overlain by carbonate, (4) within 500 m of a major perennial watercourse, or (5) within 500 m of a major ephemeral watercourse. The fractured rock classification is based on a broad-scale assessment identifying Australian aquifers with the highest water quality and yield at shallow depths86, which may not capture local heterogeneity. Carbonate surface geology was used as a proxy for karst features (e.g., sinkholes) because national-scale datasets of karst or sinkhole distribution are unavailable for Australia. Carbonate aquifers commonly display secondary porosity and conduit flow that promote focused recharge via fractures, dissolution pathways, and sinkholes. Consequently, bores screened within or overlain by carbonate formations are likely to represent environments conducive to focused recharge. Alluvium and carbonate were derived from surface geology datasets representing only surficial units; therefore, bores screened in deeper carbonate aquifers may be misattributed to alluvium in the case where alluvium is overlying carbonate. Detailed lithological logs provide more precise local characterization but were not used due to the large dataset size (>1700 bores). The 500 m buffer distance for major perennial and ephemeral watercourses was chosen to ensure balance in the number of bores classified as high- and low-likelihood focused recharge. Different thresholds would alter the number of bores associated with each watercourse type and result in sample size imbalance (see Table S7 of the supporting information for more details).

The associations between focused recharge likelihood, landscape features and aridity index-based climate zone were assessed statistically using Pearson chi-square tests. We applied Fisher’s exact test where sample sizes were insufficient for a valid Pearson chi-square test. All statistical analyses were conducted using the scipy.stats module from the Scipy library in Python. The full set of scripts used in these analyses is provided in the Hydroshare link in the Source Data section.

Data availability

The output data produced in this study are available as supporting information at the following Hydroshare link: http://www.hydroshare.org/resource/a9da2e2a766f403793bca6dc379715af93. Data used to support the findings in this study were obtained from different sources. Groundwater tritium data sources are listed in Table S1. Rainfall tritium data was provided by ANSTO52. The surface geology of Australia shapefile can be accessed at: https://ecat.ga.gov.au/geonetwork/srv/api/records/c8856c41-0d5b-2b1d-e044-00144fdd4fa685. The hydrogeology map of Australia shapefile can be accessed at: https://ecat.ga.gov.au/geonetwork/srv/api/records/2da7c234-63e9-10b2-e053-12a3070a174b86. The national surface hydrology lines dataset can be accessed at: https://ecat.ga.gov.au/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/8313087. The gridded predicted rainfall tritium map can be accessed at: https://isotopehydrologynetwork.iaea.org/57. The NGIS bore logs from the Australian Groundwater Explorer provided by the Bureau of Meteorology are available at: http://www.bom.gov.au/water/groundwater/explorer/83. Some data presented in this paper has been visualised using scientific colour maps created by Crameri94.

Code availability

The Python script used for data analysis is available at the following Hydroshare link:

http://www.hydroshare.org/resource/a9da2e2a766f403793bca6dc379715af93.

References

Green, T. R. et al. Beneath the surface of global change: Impacts of climate change on groundwater. J. Hydrol. 405, 532–560 (2011).

Wada, Y., Van Beek, L. P. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Modelling global water stress of the recent past: on the relative importance of trends in water demand and climate variability. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 3785–3808 (2011).

Morin-Crini, N. et al. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 2311–2338 (2022).

Schwarzenbach, R. P., Egli, T., Hofstetter, T. B., Von Gunten, U. & Wehrli, B. Global Water Pollution and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 109–136 (2010).

Gleeson, T., Wada, Y., Bierkens, M. F. P. & van Beek, L. P. H. Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature 488, 197–200 (2012).

Wada, Y. et al. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, n/a-n/a (2010).

Werner, A. D. et al. An Initial Inventory and Indexation of Groundwater Mega-Depletion Cases. Water Resour. Manag. 27, 507–533 (2013).

Feng, S. & Fu, Q. Expansion of global drylands under a warming climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10081–10094 (2013).

Huang, J., Yu, H., Guan, X., Wang, G. & Guo, R. Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 166–171 (2016).

Koutroulis, A. G. Dryland changes under different levels of global warming. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 482–511 (2019).

Loaiciga, H. A. & Doh, R. Groundwater for People and the Environment: A Globally Threatened Resource. Groundwater 62, 332–340 (2024).

Acworth, R. I., Rau, G. C., Cuthbert, M. O., Leggett, K. & Andersen, M. S. Runoff and focused groundwater-recharge response to flooding rains in the arid zone of Australia. Hydrogeol. J. 29, 737–764 (2021).

de Vries, J. J. & Simmers, I. Groundwater recharge: an overview of processes and challenges. Hydrogeol. J. 10, 5–17 (2002).

Lerner, D. N., Issar, A. S. & Simmers, I. Groundwater recharge: A Guide to Understanding and Estimating Natural Recharge, International Contributions to Hydrogeology. International Association of Hydrogeologists, Goring, UK 8, (1990).

Lee, S., Irvine, D. J., Duvert, C., Rau, G. C. & Cartwright, I. A high-resolution map of diffuse groundwater recharge rates for Australia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 1771–1790 (2024).

Scanlon, B. R. et al. Global synthesis of groundwater recharge in semiarid and arid regions. Hydrol. Process. 20, 3335–3370 (2006).

Scanlon, B. R., Langford, R. P. & Goldsmith, R. S. Relationship between geomorphic settings and unsaturated flow in an arid setting. Water Resour. Res. 35, 983–999 (1999).

Healy, R. W. Estimating Groundwater Recharge. (Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2010).

Meixner, T. et al. Implications of projected climate change for groundwater recharge in the western United States. J. Hydrol. 534, 124–138 (2016).

Hartmann, A., Goldscheider, N., Wagener, T., Lange, J. & Weiler, M. Karst water resources in a changing world: Review of hydrological modeling approaches. Rev. Geophysics 52, 218–242 (2014).

Armengol, S. et al. Isogeochemical characterization of mountain system recharge processes in the Sierra Nevada, California. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR035719 (2024).

Gee, G. W. & Hillel, D. Groundwater recharge in arid regions: Review and critique of estimation methods. Hydrological Process. 2, 255–266 (1988).

Allison, G. B., Gee, G. W. & Tyler, S. W. Vadose-Zone Techniques for Estimating Groundwater Recharge in Arid and Semiarid Regions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 58, 6–14 (1994).

Li, M., Xie, Y., Dong, Y., Wang, L. & Zhang, Z. Review: Recent progress on groundwater recharge research in arid and semiarid areas of China. Hydrogeol. J. 32, 9–30 (2024).

Owuor, S. O. et al. Groundwater recharge rates and surface runoff response to land use and land cover changes in semi-arid environments. Ecol. Process 5, 16 (2016).

Xu, Y. & Beekman, H. E. Review: Groundwater recharge estimation in arid and semi-arid southern Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 27, 929–943 (2019).

Berghuijs, W. R., Luijendijk, E., Moeck, C., van der Velde, Y. & Allen, S. T. Global recharge data set indicates strengthened groundwater connection to surface fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099010 (2022).

West, C. et al. Ground truthing global-scale model estimates of groundwater recharge across Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159765 (2023).

Reinecke, R. et al. Uncertainty in model estimates of global groundwater depth. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 114066 (2024).

Cuthbert, M. O. et al. Observed controls on resilience of groundwater to climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 572, 230–234 (2019).

Baker, A. et al. An underground drip water monitoring network to characterize rainfall recharge of groundwater at different geologies, environments, and climates across Australia. Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 13, 117–129 (2024).

Barua, S., Cartwright, I., Dresel, P. E. & Daly, E. Using multiple methods to investigate the effects of land-use changes on groundwater recharge in a semi-arid area. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 89–104 (2021).

Boas, T. & Mallants, D. Episodic extreme rainfall events drive groundwater recharge in arid zone environments of central Australia. J. Hydrol.: Regional Stud. 40, 101005 (2022).

Cartwright, I., Werner, A. & Woods, J. Using geochemistry to discern the patterns and timescales of groundwater recharge and mixing on floodplains in semi-arid regions. J. Hydrol. 570, 612–622 (2019).

Crosbie, R. S., Holland, K. L. & McVicar, T. R. Regional-scale partitioning of transmission losses and groundwater recharge using satellite estimates of actual evapotranspiration in an arid environment. Ecohydrology 16, e2490 (2023).

Hocking, M. & Kelly, B. F. J. Groundwater recharge and time lag measurement through Vertosols using impulse response functions. J. Hydrol. 535, 22–35 (2016).

Priestley, S. C. et al. A 35 ka record of groundwater recharge in south-west Australia using stable water isotopes. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 135105 (2020).

Skrzypek, G., Siller, A., McCallum, J. L. & Dogramaci, S. Groundwater recharge through internally drained basins in a semiarid climate, Western Australia. J. Hydrol.: Regional Stud. 47, 101388 (2023).

Wood, C., Cook, P. G., Harrington, G. A. & Knapton, A. Constraining spatial variability in recharge and discharge in an arid environment through modeling carbon-14 with improved boundary conditions. Water Resour. Res. 53, 142–157 (2017).

Xie, Y., Crosbie, R., Yang, J., Wu, J. & Wang, W. Usefulness of Soil Moisture and Actual Evapotranspiration Data for Constraining Potential Groundwater Recharge in Semiarid Regions. Water Resour. Res. 54, 4929–4945 (2018).

Baker, A. et al. Rainfall recharge thresholds in a subtropical climate determined using a regional cave drip water monitoring network. J. Hydrol. 587, 125001 (2020).

Chmielarski, M. et al. Identifying the influence of episodic events on groundwater recharge in semi-arid environments using environmental tracers. J. Hydrol. 633, 130848 (2024).

Cuthbert, M. O. et al. Understanding and quantifying focused, indirect groundwater recharge from ephemeral streams using water table fluctuations. Water Resour. Res. 52, 827–840 (2016).

Robson, T. C. & Webb, J. A. The use of environmental tracers to determine focused recharge from a saline disposal basin and irrigation channels in a semiarid environment in Southeastern Australia. J. Hydrol. 538, 326–338 (2016).

Allison, G. & Hughes, M. The use of environmental chloride and tritium to estimate total recharge to an unconfined aquifer. Soil Res. 16, 181 (1978).

Allison, G. B. & Hughes, M. W. Comparison of recharge to groundwater under pasture and forest using environmental tritium. J. Hydrol. 17, 81–95 (1972).

Cartwright, I. & Morgenstern, U. Constraining groundwater recharge and the rate of geochemical processes using tritium and major ion geochemistry: Ovens catchment, southeast Australia. J. Hydrol. 475, 137–149 (2012).

Cook, P. G. & Robinson, N. I. Estimating groundwater recharge in fractured rock from environmental 3H and 36Cl, Clare Valley, South Australia. Water Resour. Res. 38, 111–1113 (2002).

Cartwright, I., Cendón, D., Currell, M. & Meredith, K. A review of radioactive isotopes and other residence time tracers in understanding groundwater recharge: Possibilities, challenges, and limitations. J. Hydrol. 555, 797–811 (2017).

Li, Z., Chen, X., Liu, W. & Si, B. Determination of groundwater recharge mechanism in the deep loessial unsaturated zone by environmental tracers. Sci. Total Environ. 586, 827–835 (2017).

Telloli, C. et al. Characterization of groundwater recharge through tritium measurements. Adv. Geosci. 57, 21–36 (2022).

Tadros, C. V., Hughes, C. E., Crawford, J., Hollins, S. E. & Chisari, R. Tritium in Australian precipitation: A 50 year record. J. Hydrol. 513, 262–273 (2014).

Jasechko, S. et al. Global aquifers dominated by fossil groundwaters but wells vulnerable to modern contamination. Nat. Geosci. 10, 425–429 (2017).

Cabrera, A., Cendón, D. I., Aparicio, V. & Currell, M. J. Intensive agriculture, a pesticide pathway to >100 m deep groundwater below dryland agriculture, Cordoba Pampas, Argentina. J. Hydrol. 643, 131989 (2024).

Taufiq, A. et al. Impact of excessive groundwater pumping on rejuvenation processes in the Bandung basin (Indonesia) as determined by hydrogeochemistry and modeling. Hydrogeol. J. 26, 1263–1279 (2018).

Thaw, M., GebreEgziabher, M., Villafañe-Pagán, J. Y. & Jasechko, S. Modern groundwater reaches deeper depths in heavily pumped aquifer systems. Nat. Commun. 13, 5263 (2022).

Terzer-Wassmuth, S., Araguás-Araguás, L. J., Copia, L. & Wassenaar, L. I. High spatial resolution prediction of tritium (3H) in contemporary global precipitation. Sci. Rep. 12, 10271 (2022).

Pinti, D. L. et al. Origin of volatile species and aqueous fluids in the Los Humeros Geothermal Field, Mexico. Chem. Geol. 584, 120539 (2021).

Poulsen, D. L., Cook, P. G., Simmons, C. T., Solomon, D. K. & Dogramaci, S. Depth-Resolved Groundwater Chemistry by Longitudinal Sampling of Ambient and Pumped Flows Within Long-Screened and Open Borehole Wells. Water Resour. Res. 55, 9417–9435 (2019).

Reinecke, R. et al. Uncertainty of simulated groundwater recharge at different global warming levels: a global-scale multi-model ensemble study. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 787–810 (2021).

Döll, P. & Fiedler, K. Global-scale modeling of groundwater recharge. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc. 12, 863–885 (2008).

Graaf, de et al. A high-resolution global-scale groundwater model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc. 19, 823–837 (2015).

Müller Schmied, H. et al. The global water resources and use model WaterGAP v2. 2d: Model description and evaluation. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 1037–1079 (2021).

Wan, W., Döll, P. & Müller Schmied, H. Global-Scale Groundwater Recharge Modeling Is Improved by Tuning Against Ground-Based Estimates for Karst and Non-Karst Areas. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR036182 (2024).

Cendón, D. I. et al. Freshwater recharge into a shallow saline groundwater system, Cooper Creek floodplain, Queensland, Australia. J. Hydrol. 392, 150–163 (2010).

Jasechko, S. et al. The pronounced seasonality of global groundwater recharge. Water Resour. Res. 50, 8845–8867 (2014).

Guinea, A., Hollins, S., Meredith, K., Hankin, S. & Cendón, D. I. Characterization of the subsurface architecture and identification of potential groundwater paths in a clay-rich floodplain using multi-electrode resistivity imaging. Hydrological Sci. J. 63, 909–925 (2018).

Lapworth, D. J. et al. Deep urban groundwater vulnerability in India revealed through the use of emerging organic contaminants and residence time tracers. Environ. Pollut. 240, 938–949 (2018).

Cartwright, I., Weaver, T., Cendón, D. & Swane, I. Environmental isotopes as indicators of inter-aquifer mixing, Wimmera region, Murray Basin, Southeast Australia. Chem. Geol. 277, 214–226 (2010).

Meredith, K. T. et al. Evaporation and concentration gradients created by episodic river recharge in a semi-arid zone aquifer: Insights from Cl−, δ18O, δ2H, and 3H. J. Hydrol. 529, 1070–1078 (2015).

Jasechko, S. et al. Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496, 347–350 (2013).

Gleeson, T., Novakowski, K. & Kurt Kyser, T. Extremely rapid and localized recharge to a fractured rock aquifer. J. Hydrol. 376, 496–509 (2009).

Lall, U., Josset, L. & Russo, T. A Snapshot of the World’s Groundwater Challenges. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45, 171–194 (2020).

Gorelick, S. M. & Zheng, C. Global change and the groundwater management challenge. Water Resour. Res. 51, 3031–3051 (2015).

Bierkens, M. F. P. & Wada, Y. Non-renewable groundwater use and groundwater depletion: a review. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 063002 (2019).

Gleeson, T., Cuthbert, M., Ferguson, G. & Perrone, D. Global Groundwater Sustainability, Resources, and Systems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 431–463 (2020).

Wada, Y. & Heinrich, L. Assessment of transboundary aquifers of the world—vulnerability arising from human water use. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 024003 (2013).

Clark, I. D. & Fritz, P. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology. (CRC Press, 1997).

Duvert, C., Stewart, M. K., Cendón, D. I. & Raiber, M. Time series of tritium, stable isotopes and chloride reveal short-term variations in groundwater contribution to a stream. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 257–277 (2016).

Morgenstern, U. & Daughney, C. J. Groundwater age for identification of baseline groundwater quality and impacts of land-use intensification – The National Groundwater Monitoring Programme of New Zealand. J. Hydrol. 456–457, 79–93 (2012).

Stewart, M. K., Morgenstern, U. & McDonnell, J. J. Truncation of stream residence time: how the use of stable isotopes has skewed our concept of streamwater age and origin. Hydrological Process. 24, 1646–1659 (2010).

Geoscience Australia. Grid Coordinate Application Batch Processing. Geodetic Calculators: Grid Coordinate Application Batch Processing https://geodesyapps.ga.gov.au/grid-coordinate-batch-processing (2021).

Bureau of Meteorology. Australian Groundwater Explorer. http://www.bom.gov.au/water/groundwater/explorer/map.shtml (2025).

Taylor, C. B. & Fletcher, E. H. Assessment of Data for Tritium in Southern Hemisphere Precipitation, 1960-1983. 20 (1988).

Raymond, Liu, Gallagher, Zhang, & Highet. Surface Geology of Australia 1:1 million scale dataset 2012 edition. https://doi.org/10.26186/74619 (2012).

BrodieR., Kilgour, B., Jacobson, G. & Lau, J. Hydrogeology Map of Australia (G.Jacobson and JE.Lau Hydrogeology Map). (2019).

Crossman, S. & Li, O. Surface Hydrology Lines (National). (2015).

Bureau of Meteorology. Australian Water Outlook. https://awo.bom.gov.au/ (2022).

Bureau of Meteorology. Decadal and multi-decadal rainfall averages maps. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/maps/averages/decadal-rainfall/ (2023).

United Nations Environment Programme. World Atlas of Desertification: Second Edition. (1997).

Cartwright, I. & Morgenstern, U. Transit times from rainfall to baseflow in headwater catchments estimated using tritium: The Ovens River, Australia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 3771–3785 (2015).

Duvert, C. et al. Seasonal shift from biogenic to geogenic fluvial carbon caused by changing water sources in the wet-dry tropics. JGR Biogeosci. 125, e2019JG005384 (2020).

Lee, S. Focused groundwater recharge driven by landscape controls and climate. HydroShare, http://www.hydroshare.org/resource/a9da2e2a766f403793bca6dc379715af (2025).

Crameri, F. Scientific colour maps. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1243862 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands related to any aspects of this study. We would like to acknowledge the institutions and individuals that collected the data used in this study originally. We are grateful to the three anonymous peer reviewers for their detailed reviews and valuable suggestions. Stephen Lee was supported by a Research Training Programme scholarship (doi.org/10.82133/C42F-K220) through Charles Darwin University and by the Australian Geoscience Council Lee Parkin Australian Geoscience Information Association Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. contributed to research design, collated data, conducted all data analyses and wrote the original manuscript. D.I. conceptualised the idea for the study, providing primary supervision and supported the writing and review of the manuscript. G.R. supported the writing and review of the manuscript. M.C. supported the writing and review of the manuscript. C.T. supported the writing and review of the manuscript. C.D. conceptualised the idea for the study, providing secondary supervision, and supported the writing and review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Nadim K. Copty and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Nicola Colombo. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Irvine, D.J., Rau, G.C. et al. Focused groundwater recharge is controlled by landscape and climate. Commun Earth Environ 7, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03063-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03063-w