Abstract

Extreme heat and heightened ultraviolet radiation are both projected to intensify under climate change, posing increasing risks to public health. Individual differences and demographic trends further complicate the concurrent heat and high ultraviolet stress, leaving global patterns of the compound event underexplored. Here we merged global climate data with the Ultraviolet Index and demographic characteristics for 1960–2100. Our analysis shows Central Asia, North Africa, and India have historically experienced frequent combined stress, with future projections indicating intensification. By the end of this century, population exposure is expected to increase 1.98- to 3.69-fold across emission scenarios relative to the 1960–2022 baseline, with India, China, and Pakistan facing the highest risks. The elderly population (≥ 65 years) is projected to experience a marked increase in exposure. Our findings identify regions and populations most at risk, laying the groundwork for strategies to reduce health risks in a warming world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is increasing the frequency, intensity, and complexity of extreme weather events, posing serious threats to human health and environmental sustainability1,2,3. Among these events, extreme heat is especially concerning due to its global rise and wide-ranging impacts, including higher risks of heat exhaustion and heatstroke4,5,6. Heat stress already ranks among the deadliest natural hazards, with excess mortality disproportionately affecting the elderly and individuals with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases7,8. Heat stress also worsens ecological challenges by intensifying water scarcity9, accelerating soil degradation, and heightening ecosystem vulnerability5, threatening food security, livelihoods, and ecosystem stability. These adverse impacts are projected to intensify worldwide because of ongoing climate warming and demographic shifts10. However, most current research emphasizes climatological dynamics based on percentile thresholds11, overlooking individual differences and future demographic changes, and ultimately underestimating the extent of heat‑stress impacts.

While solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation is essential for vitamin D synthesis, excessive exposure can be harmful12, elevating risks of skin cancer and cataracts in humans and placing photochemical stress on ecosystems. Although global initiatives like the Montreal Protocol have helped reduce harmful UV levels by protecting the ozone layer13, recent findings suggest that cloud cover (CC), aerosol concentrations, and atmospheric circulation patterns (shaped by climate warming) could further alter UV radiation14,15. Such shifts increase the likelihood of simultaneous extreme heat stress and high UV radiation, amplifying heat-related and dermatological burdens.

The concurrent exposure to extreme heat and elevated UV radiation intensifies pressures on public health and ecosystem productivity, potentially triggering cascading effects on heat-related illnesses, air quality, and food security15,16. For example, intense solar UV radiation combined with high heat stress accelerates photochemical reactions that produce ground-level ozone17,18,19, a harmful pollutant affecting humans, crops, and ecosystems. Failure to consider these synergistic interactions risks systematic underestimation or overestimation of health impacts when designing adaptation strategies. Despite these risks, the compound hazard of concurrent extreme heat and high UV radiation, termed compound heat-UV stress (CHUV), remains largely understudied, leaving unanswered key questions about its global distribution, long-term trends, mechanisms, and population impacts.

Here, we examined daily-scale CHUV events from 1960 to 2100 using physiological criteria based on daily climate data and UV index (UVI) information. For the historical analysis (1960–2022), we used data from ECMWF Reanalysis Version 5 (ERA5) and Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) historical simulations. Future projections (2015–2100) utilized CMIP6 outputs under four Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585). Our analysis incorporated location-, age-, and sex-specific factors, including biological differences and adaptive capacity (see “Methods” section). We evaluated the frequency and intensity of CHUV events in historical and future climates and explored the physical processes influencing their evolution. By incorporating population data, we identified regions and demographic groups particularly vulnerable to CHUV events, providing essential insights for targeted mitigation and adaptation measures. Overall, this comprehensive approach to understanding how UV radiation and heat stress interact offers valuable guidance for addressing compound hazards, ultimately aiding in protecting human health and preserving ecological integrity.

Results

Characteristics of CHUV events

We defined CHUV events as occurrences characterized by simultaneous extreme heat stress and high UV exposure. Extreme heat conditions, which can rapidly elevate core body temperature to hazardous levels, were identified based on the local climatic context (e.g., temperature and humidity) and age- and sex-specific human physiological limits20,21 (see “Methods” section). Concurrently, a UVI exceeding 11 poses severe risks, as unprotected skin and eyes can be harmed within minutes22. We accounted for demographic vulnerabilities by computing separate heat stress thresholds for individuals aged 15–64 (working-age population) and those ≥65 years (elderly population), stratified by sex. Among these subgroups, elderly males consistently exhibited the lowest heat tolerance thresholds, making them most susceptible to CHUV risks (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). This heightened susceptibility is primarily attributed to physiological differences where, on average, males have a larger body size and consequently a lower surface-area-to-mass ratio, which is less efficient for heat dissipation. Combined with a typically higher metabolic heat production, these factors mean that elderly males accumulate heat more rapidly under the same environmental conditions, thus reaching critical core temperature limits faster than their female counterparts. Here, we present the spatiotemporal patterns of the frequency of CHUV events (events per year) and their spatial extent (km²), based on the thresholds established for elderly males.

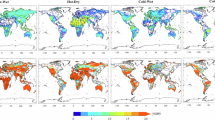

Globally, CHUV events predominantly occur within the latitudinal range of 0–30° N (e.g., parts of Mexico, North Africa, the Middle East, and India), with notable occurrences also observed in Western and Central Australia in the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 1). We observed similar spatial patterns for other demographic subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 4). These events have become increasingly frequent from 1960 to 2022 and are projected to rise through the end of the 21st century (2070–2099), with an approximately 2.0 ± 0.23-fold increase under the high-emission SSP585 scenario. Regions such as central Africa, North America, and Eurasia around 40° N are expected to experience more CHUV events as their geographic footprint expands (Fig. 1a). Consequently, the global area exposed to CHUV events expanded by 63% historically (from 114 to 186 million km²) and is projected to increase by an additional 26–127% through the end of the 21st century. Although historically confined primarily to hot months, CHUV events are anticipated to extend increasingly into spring and fall months, a concerning trend that underscores the need for enhanced preventive measures throughout the year (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Global distribution of average CHUV event frequency during 1960–2022 (events year⁻¹), with mean frequency shown by latitude. Colors from blue to red indicate increasing event frequency (0–10 events year⁻¹), and projected future expansions of CHUV events are highlighted in coral-colored regions. b Global mean frequency of CHUV events historically and under future scenarios. c Total global area affected by CHUV events from 1960 to 2100 (million km²). b, c The historical average (Hist) was calculated using climate data from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset and four general circulation models (GCMs) from CMIP6. Future simulations (SSP126 to SSP585) are based on the four CMIP6 GCMs. Lines represent: Hist (gray line), ERA5 (light green line), CMIP6 (light blue line), SSP126 (blue line), SSP370 (orange line), and SSP585 (red line). Shading indicates ±1 standard deviation across the ERA5 and CMIP6 ensemble (see “Methods” section).

We further investigated changes in the intensity of CHUV events by examining the joint distribution of average wet-bulb temperature (WBT, an integrated metric of temperature and humidity) and the UVI during historical CHUV occurrences (Fig. 2a), as well as at the end of the 21st century under SSP585 (2070–2099; Fig. 2b). We found that Australia and South Africa experienced both extreme heat stress (WBT > 35 °C) and high UV exposure (UVI > 14), while Northern Asia, North Africa, and North America primarily exhibited high heat stress but relatively lower UV levels. By contrast, South America showed more extensive areas of high UV exposure but lower WBT. In future projections, regions that historically faced the highest threats from both heat stress and UV exposure are projected to see intensified CHUV events (WBT > 40 °C, UVI > 16), especially in northern Australia and South Africa. Moreover, the Amazon region is particularly threatened by even higher UV radiation. In addition, Central Africa is anticipated to face increases in both extreme heat and UV exposure, suggesting an overall expansion and intensification of CHUV events in the future.

The intensity is characterized by the combined average WBT and ultraviolet index (UVI) during (a) historical CHUV occurrences (1960–2022), and b projected CHUV events at the end of the 21st century (2070–2099) under a high-emission scenario (SSP585). Colors represent the bivariate combination of WBT (horizontal axis, from 30 °C to 40 °C) and UVI (vertical axis, from 12 to 16), as shown in the inset legend.

Population exposure to CHUV

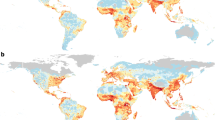

We assessed the global population exposure to CHUV events and identified hotspots primarily concentrated between 30° S and 30° N, notably in Latin America, South and East Asia, and Australia (Fig. 3a). India, China, and Pakistan emerged as the most exposed countries, with population exposure totaling 4.93 × 10⁹, 9.96 × 10⁸, and 9.13 × 10⁸, respectively, making them the three most exposed nations (Fig. 3c). Notably, six of the ten countries with the highest exposure are in Asia, collectively accounting for more than 50% of global CHUV exposure.

a The global spatial patterns of the average annual population exposure to CHUV events during the 2010s. Colors from light to dark red indicate increasing population exposure (10⁴ people). b The historical and future estimates of global total population exposure to CHUV events annually. Lines represent: Hist (gray line), ERA5 (light green line), CMIP6 (light blue line), SSP126 (blue line), SSP370 (orange line), and SSP585 (red line). Shading indicates ±1 standard deviation. c Top 10 vulnerable countries with the most population exposure to CHUV events in the 2010s. Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. d Average annual population exposure in different age groups in the 2010s and under future scenarios (2070–2099). Bars represent the working-age group (15–64 years; light blue bars) and the elderly group (≥65 years; light red bars). Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. Note: the population exposure here refers to the total number of people across all grid cells that experience the occurrence of CHUV events.

From 1960 to 2022, the global population exposure to CHUV events nearly tripled and is projected to rise further under future climate scenarios (Fig. 3b). However, these exposure trends are strongly modulated by divergent population trajectories across SSPs (Supplementary Fig. 8). The highest exposure is projected under SSP370, driven by the combined effect of increased CHUV frequency and the substantial population growth projected for this pathway8. By contrast, exposure under SSP585 is expected to rise mid-century before declining slightly toward 2100. Importantly, this decline does not reflect a reduction in the underlying climate hazard; rather, it is largely attributable to the projected decrease in global population under SSP585, indicating that total exposure is jointly determined by both the frequency of climate hazards and demographic trajectories in the future.

Additionally, we evaluated the relative changes in CHUV exposure across different age groups (Fig. 3d). Our results reveal a pronounced increase in exposure among elderly populations under all future scenarios. By the end of the 21st century (2070–2099), exposure for elderly populations is projected to rise dramatically, ranging from a 1.98 ± 0.61-fold to a 3.69 ± 0.83-fold increase across different scenarios, compared to the historical baseline. Additionally, the working-age population is also likely to experience increasing exposure, especially under SSP370. These findings underscore severe public health risks associated with climate change and demographic shifts, highlighting an urgent need for targeted adaptation strategies.

Attribution of CHUV events

To isolate the drivers of CHUV events, we analyzed the frequency of heat stress-only and high UV-only events separately (Supplementary Fig. 9). During the historical period (1960–2022), the spatiotemporal patterns of CHUV events (Fig. 1) aligned more closely with those of heat stress-only events (Supplementary Fig. 9a, c). This finding is supported by correlation analysis, which shows that the global annual frequency of CHUV events was more strongly associated with heat stress-only events (r = 0.89) than with high UV-only events (r = 0.79). In future scenarios, however, CHUV frequency is projected to correlate strongly with both drivers. Under SSP585, for example, the correlations will substantially strengthen for both heat stress-only (r = 0.96) and high UV-only events (r = 0.95). This intensifying coupling indicates that continued warming will simultaneously exacerbate extreme heat and UV radiation.

To investigate the underlying physical mechanisms of CHUV events, we selected Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India as a case study, which is a hotspot for frequent CHUV occurrences impacting densely populated areas. This region also exemplifies how interactions between large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns (i.e., 500 hPa geopotential height (GH), sea-level pressure (PSL)) and local land-atmosphere feedback processes (i.e., vapor pressure deficit, VPD) result in such compound extremes.

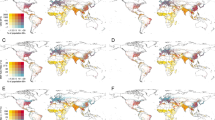

We observed that Andhra Pradesh experienced persistent positive anomalies in mid-tropospheric 500 hPa GH from 1960 to 2022, with values typically ranging from +1 to +4 m (Fig. 4a). These anomalies enhanced large-scale atmospheric subsidence, suppressing cloud formation and reducing convective activity. Such conditions increased incoming solar radiation, elevating surface heat stress and UV radiation exposure. Concurrent positive anomalies in VPD, usually between +0.1 and +0.3 kPa (Fig. 4b), indicate drier atmospheric conditions and heightened evaporative demand. Additionally, the PSL anomalies typically ranged from approximately +10 to +40 Pa (Fig. 4c), further indicating persistent high-pressure conditions. These conditions diminished CC (Fig. 4d) and atmospheric moisture, thereby amplifying heat accumulation and UV intensity.

Panels show anomalies in a 500 hPa GH, b VPD, c PSL, and d CC from 1960 to 2022. e–h Present projected anomalies for these variables from 2070–2099 under SSP585. In all panels, colored shading indicates the magnitude of the anomaly as defined by the corresponding color bar (e.g., yellows/reds for positive anomalies, blues/purples for negative anomalies). a, e Arrows indicate the direction and magnitude of vectors, with the reference vector scale (200 kg m⁻¹ s⁻¹) shown at the top.

Projections for 2070–2099 suggest intensified positive anomalies in 500 hPa GH (Fig. 4e), VPD (Fig. 4f), and PSL (Fig. 4g) over Andhra Pradesh. Compared to the historical period, this region will likely experience elevated mid-tropospheric GHs, signifying increased atmospheric warming and stronger subsidence. This heightened anomaly will further suppress cloud formation and enhance surface warming (Fig. 4h). Enhanced anomalies in VPD suggest conditions will become increasingly arid, with higher evaporative demand and prolonged exposure to intensified UV radiation. Additionally, persistent or expanding high PSL conditions are projected to sustain stable, precipitation-deficient weather, resulting in more frequent and severe compound events of heat stress combined with high UV exposure in this coastal region.

Discussion

Our study reveals, from a physiological perspective, an escalating threat posed by concurrent heat and UV radiation stress, particularly in regions with large and rapidly growing populations, such as Central and South Asia, North Africa, and Northern Australia. We found that these CHUV hotspots align with earlier research identifying distinct hotspots of high temperature and humidity in South Asia10 and intense UV exposure in Australia23. By jointly assessing these stressors, we offer a more comprehensive understanding of the combined risks from heat and UV exposure.

By integrating age- and sex-specific physiological characteristics and demographic shifts, we noted that the elderly population faces higher risks than younger adults, thereby supporting evidence that individual thermoregulatory limits depend on factors such as adaptation capacity and body size20. This diverges from uniform thresholds (e.g., a WBT above 35 °C24), which overlook inter-individual variability and may result in an underestimation of the distinct adaptation abilities among different age groups. We found that India and China are especially at risk, partly due to rising populations25,26 and rapid urban growth27 that intensify local heat and UV exposures. Additionally, our analysis highlights that future exposure is determined by the interaction between changing climate hazards and population trajectories, with scenarios of population growth (e.g., SSP370) showing a dramatic rise in exposure driven by the combined effects of intensifying climatic threats and expanding populations, suggesting that demographic change can also influence climate-related risk assessments. Furthermore, these risks are compounded at the local level; for instance, urban heat-island amplification and high ambient aerosol loads can modify the spectral composition of UV radiation, potentially worsening photooxidative stress and respiratory morbidity in megacities. These findings emphasize the importance of incorporating physiological heterogeneity into heat-UV risk assessments.

CHUV extremes impose an immediate and substantial health burden. Co-exposure magnifies physiological stress and elevates all-cause and cardiorespiratory mortality15. In addition, the impacts of CHUV extremes extend beyond health outcomes to affect labor productivity, energy demand, and healthcare capacity28,29. Over half of the top 20 most exposed countries are in Asia, where the combination of accelerating urbanization and constrained healthcare infrastructure amplifies the vulnerability of the elderly population and outdoor workers. Managing these dual hazards will require comprehensive public health interventions, from expanded heat advisories and improved cooling access to targeted UV protection measures, underpinned by robust risk assessments that account for socioeconomic contexts and demographic changes.

At the process level, we revealed that large-scale atmospheric circulation interacts with local atmospheric drying to establish persistent high-pressure ridges, which suppress cloud formation, increase incoming solar radiation, and trap heat near the surface. These stable conditions may foster a hazardous overlap of intensified heat stress and high UV exposure30, as demonstrated in Andhra Pradesh. Notably, although ozone recovery efforts have curbed one source of excessive UV13, our findings indicate that climate warming has emerged as a primary driver of more frequent CHUV extremes.

Despite these insights, we noted that limitations remain in capturing the evolution of CHUV events, primarily arising from uncertainties in cloud dynamics31, aerosol interactions32, and local-scale feedbacks in future projections33. Another challenge stems from the temporal mismatch between heat and UV metrics. While our analysis employed sub-daily (i.e., 6-h) heat stress observations, the UVI is only available at midday, potentially overlooking short-term overlaps between peak heat and UV levels. Producing the UVI at finer temporal resolutions would therefore enhance our ability to characterize the full extent of CHUV extremes.

Notably, while our model accounts for age- and sex-related physiological changes, it does not explicitly capture the influence of specific health conditions (e.g., metabolic or cardiovascular diseases), which can further exacerbate individual vulnerability. Incorporating such factors is an important direction for risk assessments of specific populations in a warming future. Additionally, our study focuses on survivability limits under resting conditions and does not assess the additional thermal load from physical activity, such as outdoor labor. Future research could extend this analysis to evaluate occupational heat stress by applying the livability component of the physiological framework, which considers variable metabolic rates20. In contrast to demographic-specific vulnerabilities to heat stress, our study applied a uniform UVI to represent population vulnerability, although susceptibility can differ slightly by age (e.g., higher sensitivity in children and the elderly) and race (e.g., darker skin provides partial protection against erythema and skin cancer). Incorporating such differences at the global scale, however, remains challenging due to substantial gaps in population-level UV vulnerability data.

In conclusion, our findings underscore an intensifying risk from compound heat and UV extremes under climate change, emphasizing the importance of age- and sex-specific physiological thresholds in risk evaluations, particularly in densely populated Asian regions. Large-scale atmospheric patterns coupled with local land-atmosphere feedback are key drivers of these events. As these compounding hazards become more frequent, developing integrated heat-UV warning systems and incorporating both meteorological and demographic factors into resilience strategies will be essential for safeguarding global public health.

Methods

Ultraviolet index (UVI)

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is linked to skin cancer and sunburn, but also plays an essential role in vitamin D production12. The UVI is a standardized measure designed to inform the public about potential risks of UV exposure. To enable broad and detailed assessments of UV radiation worldwide, we obtained and used the TEMIS UVI dataset, which comprises two separate UV data records based on different ozone sources (the TEMIS operational ozone record and the multi-sensor reanalysis [MSR-2] ozone record). We selected the MSR-2 record (v2.0–2.2; https://www.temis.nl/uvradiation/UVarchive.php) because it provides long-term daily UVI data (from 1960 onward) at a 0.25° spatial resolution under clear-sky conditions and at local solar noon. This dataset is produced by integrating ground-based UVI measurements with total ozone column (TOC) data and the solar zenith angle (SZA), which is determined by latitude and day of year. Satellite observations are then used to derive global TOC estimates.

Following established UV estimation methods, we built daily UVI projections under multiple future climate conditions by incorporating a variety of predictive variables. Specifically, we trained a machine learning model (XGBoost) using historical daily UVI records and corresponding environmental variables from CMIP6 historical reconstructions. We then applied this calibrated model to project UVI for 2015–2100 under different SSPs and general circulation models (GCMs) from the CMIP6 projected climate trajectories. To capture diverse atmospheric and surface influences on UV, our XGBoost model employed 13 variables: longitude, latitude, elevation, leaf area index, TOC34, total CC34, aerosol optical depth at 550 nm34, near-surface wind speed35, cloud albedo34, near-surface air temperature35, surface downwelling shortwave radiation35, SZA34, and precipitable water35. Each was chosen based on evidence that it affects the scattering, reflection, or absorption of UV radiation. For example, climate change can alter CC, and higher CC tends to reduce UV levels at the surface. A detailed justification of each predictor is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

XGBoost’s gradient-boosted, tree-based framework allowed us to refine the model36, reduce overfitting, and enhance predictive accuracy. We calibrated the model through a grid search of key parameters—such as the number of trees (100–1000), maximum tree depth (1–10), learning rates (0.01, 0.1, 0.5), and gamma values (0–0.2)—and validated the approach with 10-fold cross-validation. The final model displayed robust performance, achieving an R² of 0.96 on the calibration dataset and 0.89 on an independent validation dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating its reliability in simulating UVI. To further evaluate the model’s spatial consistency, we mapped the R² values at each grid cell (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The analysis reveals that the model performs consistently well across most regions, particularly in the mid- and high latitudes, where R² values are overall above 0.8. We observed slightly lower R² values in parts of the tropical belt, likely reflecting the challenges of capturing complex radiative conditions influenced by persistent deep convective CC and seasonally elevated absorbing aerosols from biomass burning. Nevertheless, the overall spatial validation confirms the model’s robustness and suitability for generating a reliable global UVI dataset for our analysis. By integrating this calibrated model with historical and projected CMIP6 climate data, we produced spatially and temporally consistent UVI datasets across different future scenarios.

Heat stress identification

Heat stress is not only influenced by climate conditions (e.g., air temperature and humidity) but also by age and sex. In this study, we extended a newly developed physiology-based model20 to estimate local-, age-, and sex-specific thresholds for extreme heat stress worldwide. This model applies a human-environment heat exchange framework that integrates variations in human physiology, providing an advanced way to assess heatstroke survival limits.

First, we assume that an increase in core body temperature of 6 °C (from 37 °C under normothermia to 43 °C under heatstroke conditions29) corresponds to a cumulative heat accumulation of 17.88 kJ kg−1 37. Over a continuous 6-h exposure to extreme heat, this yields a critical heat storage rate (Ssurv) of 0.82 W kg⁻¹ (17.88 kJ kg⁻¹ divided by 6 h). A core temperature of 43 °C is taken as the lethal threshold for heatstroke20, based on evidence indicating a 99.9% fatality risk once core temperature reaches that level. In our model, the higher vulnerability of groups such as the elderly is represented not by altering this fundamental threshold, but by modeling the accelerated heat accumulation resulting from age-related physiological impairments (e.g., reduced sweating capacity). This accelerated accumulation causes vulnerable individuals to reach the 43 °C threshold under less extreme environmental conditions29. Given a resting metabolic heat production rate (Hprod) of 1.8 W kg⁻¹, the maximum permissible heat loss rate (Hlosspermit) is calculated as 0.98 W kg⁻¹ (Hprod − Ssurv). This resting metabolic rate was used to define the physiological limits of human survivability, representing environmental conditions beyond which survival cannot be maintained even at rest. Although basal metabolic rate varies modestly with age, the primary driver of increased vulnerability in elderly populations is the decline in thermoregulatory capacity (e.g., reduced sweat rates), which we explicitly accounted for through age-specific physiological parameters. Once the required net heat loss to maintain thermal balance surpasses Hlosspermit, heatstroke death becomes unavoidable.

Heat loss occurs primarily via radiation, convection, conduction, and evaporation. These processes depend on both individual physiology (e.g., body mass, height, skin wettedness, and sweat rate) and environmental conditions (e.g., air temperature and humidity). Notably, to account for the effect of solar radiation on heat gain in outdoor, sun-exposed settings, we adjusted the mean radiant temperature (Tᵣ), a key determinant of total radiative heat transfer. Following existing studies38, we assumed Tᵣ = Tₐᵢᵣ + 15 °C under outdoors/sun-exposed conditions, reflecting partly sunny conditions averaged over eight midday hours and simulating the additional heat load from solar radiation20. Our selection of Tᵣ = Tₐᵢᵣ + 15 °C specifically models the outdoors/sun-exposed condition, which represents the high solar radiative forcing associated with direct sun exposure38. This approach is adopted to conservatively assess physiological limits under the high-risk conditions. As the human body largely dissipates heat through sweating and evaporation, the required evaporative cooling (especially over a 6-h exposure) is crucial and is constrained by maximum skin wettedness and maximum sweat rate 39,40. Detailed equations for each component of the heat exchange process are described in the literature20,29.

Because physiological characteristics vary substantially by age and sex, we separated the population into a working-age group (15–64 years) and an elderly group (≥65 years), and we also distinguished males from females. Differences in body mass and sweat rate substantially affect heat dissipation among these groups. In particular, the elderly population faces heightened risks due to reduced sweating capacity and lower heat acclimatization, while sex-based distinctions in body composition further influence heat stress responses.

To account for these factors, we compiled annual, country-specific body mass index (BMI) and height data for males and females across different ages from the NCD-RisC database (https://www.ncdrisc.org/). We derived mean body size within each age group by weighting this information by national population data (https://ourworldindata.org/). For future projections, we used 2022 BMI and height estimates alongside demographic compositions projected by ISIMIP3b, acknowledging the limitation that future changes in BMI and height due to nutrition and other factors remain unquantified. We then applied age-dependent maximum skin wettedness values (0.85 for the working-age population and 0.65 for the elderly population) and maximum sweat rates (0.75 L h⁻¹ for the working-age population and 0.51 L h⁻¹ for the elderly population) to represent differing acclimatization capabilities.

By incorporating these age- and sex-specific parameters, our physiology-based approach determines a 6-h heat survival threshold (defined by combinations of air temperature and relative humidity) for each subgroup and then checks whether local climate conditions meet or exceed these limits (Supplementary Fig. 3). We identify a heat stress event if at least one of the day’s four 6-h intervals exhibits conditions surpassing the subgroup’s survival limit, indicating elevated temperature and humidity levels that exceed the human body’s heat dissipation capabilities21,41. Because our focus was on inevitable heat stress, we recorded at most one heat stress event per day per 0.25° grid cell. Finally, we sum the total population exposure across all grids, stratified by age and sex, providing a comprehensive assessment of heat stress risk.

Definition and characteristics of CHUV

We defined CHUV events as periods when heat stress coincided with intense UV radiation, indicated by a UVI above 11. This threshold represented an extreme risk of harm from unprotected sun exposure42,43. We examined the sensitivity of CHUV event frequency to varying UVI thresholds (Supplementary Fig. 6) and found a consistent increasing trend of CHUV events across a range of values from 9 to 13.

To quantify these events, we analyzed their frequency, intensity, and spatial extent from 1960 to 2022 using reanalysis data (ERA5) and simulations from four global climate models—NorESM2-MM, NorESM2-LM, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, and MPI-ESM1-2-HR—participating in CMIP6 (Supplementary Fig. 7). We also examined future projections spanning 2015 to 2100 under four SSPs (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585). Event frequency was measured as the number of CHUV event days per year, while intensity was evaluated by combining daily air temperature and UVI into a single metric (higher values reflect more severe events). We additionally quantified the total land area (in million km²) experiencing at least one CHUV event per year and population exposure annually, thereby highlighting hotspots where these risks overlap most intensely.

We assessed trends in CHUV event characteristics over time by applying the Mann-Kendall test to each 0.25° grid cell44. We present mean values with error bars representing one standard deviation, highlighting both interannual variability and uncertainties associated with reanalysis data and future model projections.

Association with atmospheric anomalies

The evolution of extreme events is strongly influenced by anomalies in atmospheric circulation20. Therefore, we investigated the atmospheric conditions associated with CHUV events in both the historical period (1960–2022) and the end of the 21st century (2070–2099). To achieve this, we analyzed daily anomalies of mid-tropospheric pressure (represented by 500 hPa GH), atmospheric dryness (VPD), PSL, and CC observed during CHUV events. These anomalies were determined by subtracting the long-term daily climatological means (for 1960–2022) or projected daily climatological means (for future scenarios) from the respective daily values. This approach enables us to assess how large-scale circulation, pressure systems, atmospheric dryness, and CC influence the occurrence and evolution of CHUV events.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

We obtained near-surface temperature, specific humidity, and wind speed from ERA5. The solar ultraviolet radiation dataset can be downloaded from the MSR-2 record (v2.0–2.2; https://www.temis.nl/uvradiation/UVarchive.php). The CMIP6 datasets (NorESM2-MM, NorESM2-LM, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, and MPI-ESM1-2-HR) were sourced from ESGF. We sourced global grid population data from 1960 to 2015 from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (https://data.isimip.org/datasets/f0a03010-fbad-4766-9729-03b138f32d3a/). Future global population (2010–2100) under SSP scenarios was also sourced from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (https://www.scidb.cn/en/detail?dataSetId=73c1ddbd79e54638bd0ca2a6bd48e3ff), as were distributions by age group and sex ratios (https://data.worldbank.org/). Additional age and weight data are available from the referenced global health (https://www.ncdrisc.org/data-downloads-adiposity.html) and demographic datasets. The data that support the findings of this study are stored in an open-access repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1756813945.

Code availability

Data analysis for this work was conducted in MATLAB version 2025a. Code is available upon request from Y.Y. (corresponding author).

References

Ebi, K. L. et al. Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 42, 293–315 (2021).

Yang, Y., Zhao, R. & Biswas, A. Delineating dynamic hydrological response units to improve simulations of extreme runoff events in changing environments. J. Hydrol. 656, 133000 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Climate change impacts on drought-flood abrupt alternation and water quality in the Hetao area, China. Water 11, 652 (2019).

Luo, M. et al. Anthropogenic forcing has increased the risk of longer-traveling and slower-moving large contiguous heatwaves. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl1598 (2024).

Yin, J. et al. Future socio-ecosystem productivity threatened by compound drought-heatwave events. Nat. Sustain. 6, 259–272 (2023).

Li, X. & Wang, S. Recent increase in the occurrence of snow droughts followed by extreme heatwaves in a warmer world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099925 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Fluctuating temperature modifies heat-mortality association around the globe. Innovation 3, 100225 (2022).

Falchetta, G., De Cian, E., Sue Wing, I. & Carr, D. Global projections of heat exposure of older adults. Nat. Commun. 15, 3678 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Timing the first emergence and disappearance of global water scarcity. Nat. Commun. 15, 7129 (2024).

Im, E., Pal, J. S. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Deadly heat waves projected in the densely populated agricultural regions of South Asia. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603322 (2017).

Brunner, L. & Voigt, A. Pitfalls in diagnosing temperature extremes. Nat. Commun. 15, 2087 (2024).

Bernhard, G. H. et al. Stratospheric ozone, UV radiation, and climate interactions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 22, 937–989 (2023).

Barnes, P. W. et al. Ozone depletion, ultraviolet radiation, climate change and prospects for a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 2, 569–579 (2019).

Williamson, C. E. et al. The interactive effects of stratospheric ozone depletion, UV radiation, and climate change on aquatic ecosystems. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 18, 717–746 (2019).

Thomas, P., Swaminathan, A. & Lucas, R. M. Climate change and health with an emphasis on interactions with ultraviolet radiation: a review. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2392–2405 (2012).

Häder, D. et al. Effects of UV radiation on aquatic ecosystems and interactions with other environmental factors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 14, 108–126 (2015).

Hodzic, A. & Madronich, S. Response of surface ozone over the continental United States to UV radiation declines from the expected recovery of stratospheric ozone. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 35 (2018).

Lam, K. S., Wang, T. J., Chan, L. Y., Wang, T. & Harris, J. Flow patterns influencing the seasonal behavior of surface ozone and carbon monoxide at a coastal site near Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 35, 3121–3135 (2001).

Chen, Z. et al. Understanding long-term variations of meteorological influences on ground ozone concentrations in Beijing during 2006–2016. Environ. Pollut. 245, 29–37 (2019).

Vanos, J. et al. A physiological approach for assessing human survivability and liveability to heat in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 14, 7653 (2023).

Raymond, C., Matthews, T. & Horton, R. M. The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw1838 (2020).

Heckman, C. J., Liang, K. & Riley, M. Awareness, understanding, use, and impact of the UV index: a systematic review of over two decades of international research. Prev. Med. 123, 71–83 (2019).

Xiang, F. et al. Weekend personal ultraviolet radiation exposure in four cities in Australia: influence of temperature, humidity and ambient ultraviolet radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 143, 74–81 (2015).

Sherwood, S. C. & Huber, M. An adaptability limit to climate change due to heat stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9552–9555 (2010).

Tuckman, P. J. Historical increases in heat wave exposure due to population and climate changes. Environ. Res. Commun. 7, 41001 (2025).

Yan, D. et al. A data set of distributed global population and water withdrawal from 1960 to 2020. Sci. Data. 9, 640 (2022).

Su, J., Jiao, L. & Xu, G. Intensified exposure to compound extreme heat and ozone pollution in summer across Chinese cities. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 78 (2025).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808–9813 (2019).

Parsons, K. Human Thermal Environments: the Effects of Hot, Moderate, and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort, and Performance (CRC Press, 2007).

Xia, Y. et al. Concurrent hot extremes and high ultraviolet radiation in summer over the Yangtze Plain and their possible impact on surface ozone. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 64001 (2022).

López, M. L., Palancar, G. G. & Toselli, B. M. Effects of stratocumulus, cumulus, and cirrus clouds on the UV-B diffuse to global ratio: experimental and modeling results. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 113, 461–469 (2012).

Wilson, S. R., Madronich, S., Longstreth, J. D. & Solomon, K. R. Interactive effects of changing stratospheric ozone and climate on tropospheric composition and air quality, and the consequences for human and ecosystem health. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 18, 775–803 (2019).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

Weatherhead, B. et al. Ozone and ultraviolet radiation (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

Bais, A. F. et al. Environmental effects of ozone depletion, UV radiation and interactions with climate change: UNEP environmental effects assessment panel, update 2017. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 17, 127–179 (2018).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, San Francisco, 2016).

Xu, X., Rioux, T. P. & Castellani, M. P. The specific heat of the human body is lower than previously believed: the journal temperature toolbox. Temperature. 10, 235–239 (2023).

Guzman-Echavarria, G., Middel, A. & Vanos, J. Beyond heat exposure—new methods to quantify and link personal heat exposure, stress, and strain in diverse populations and climates: the journal temperature toolbox. Temperature 10, 358–378 (2023).

Gagge, A. P. & Gonzalez, R. R. Mechanisms of heat exchange: biophysics and physiology. Compr. Physiol. 1, 45–84 (2011).

Havenith, G. & Fiala, D. Thermal indices and thermophysiological modeling for heat stress. Compr. Physiol. 6, 255–302 (2016).

Mora, C. et al. Global risk of deadly heat. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 501–506 (2017).

Vanicek, K., Frei, T., Litynska, Z. & Schmalwieser, A. UV-Index for the Public (Publication of the European Communities, Brussels, 2000).

Lucas, R. et al. Solar Ultraviolet Radiation: Global Burden of Disease from Solar Ultraviolet Radiation (WHO, 2006).

Mann, H. B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13, 245 (1945).

Yang, Y. Source data for: expanding compound heat and ultraviolet radiation stress amplifies exposure risks for elderly populations [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17568494 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that the computational work involved in this research is fully supported by NUS IT’s Research Computing group. This study is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2022YFC3080300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. R.Z.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Kai Wan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Martina Grecequet.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, R., Yang, Y. Expanding compound heat and ultraviolet radiation stress amplifies exposure risks for elderly populations. Commun Earth Environ 7, 50 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03070-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03070-x