Abstract

Timeframe is a critical factor in understanding the impact of climate change on the evolution of microbial community structure and ecological memory. Here, we demonstrate how bacterial functions have left lasting imprints through their inherent gene-regulatory network traits under alternating wet and dry climatic conditions over loess-paleosol geological time scales. In the drier loess soil, Gammaproteobacteria possess symbiotic nitrogen-fixing genes that promote microbial structural and functional succession over the ten-thousand-year scale and support a nitrogen fixation-comammox-nitrate reduction cycle and nitrogen memory, according to analysis of samples in Luochuan, China. The unique and extreme conditions of the paleoclimate environment can be reflected in the microbial community composition. Nitrogen deficiency in drier loess soil has facilitated shifts in bacterial phyla community composition, driving the evolutionary functional pathways and strong legacy effects. Our findings highlighting the crucial role of specific traits of Gammaproteobacteria as driving forces for stabilizing microbial systems in arid soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is altering the frequency and severity of drought events in global drylands. A more extreme climate would further increase drought intensity in global ecosystems1. Increasing aridity will affect multiple ecosystem structural and functional attributes, e.g., nutrient cycling, microbial communities, and biodiversity loss at local to global scales2,3,4,5,6. How ecosystems respond to each new climate disturbance may depend on the history of previous extreme events. The lasting effects of changing conditions in the past often manifested themselves over time7,8,9. Soil bacteria and fungi played key roles in terrestrial ecosystem responses to climate change, and their current function depended on the chronological sequence of events that shaped the interactions within the community10. However, the time scale is often hardly displayed when trying to understand current microbial dynamics. To date, due to limitations in the temporal scope of case studies, long-term site-specific field studies simultaneously examining how environmental microbiomes respond, adapt, and evolve to climate change, as well as their feedback in specific dry-wet climate regions, have not been recorded. This poses an unprecedented difficulty in identifying and modeling the effects of long-term (1–10 kyr) climate change. Likewise, the historical legacy effects of climate change on the biotic (microbial community) and abiotic (C, N, etc.) link and the allocation, and ecosystem functioning are largely unknown. This information is critical for understanding the effects of long-term drought on the evolutionary scale and evolutionary pathway of soil microbial functions, as well as future alterations of biogeochemical cycles.

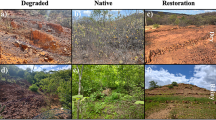

Soil memory connected ecosystem function and climate into a complex adaptive system across time and space, and it provided a way to study the effects of past events on present and future surface responses10. Loess represents one of the most comprehensive and least ambiguous paleoenvironmental records in terrestrial ecosystems. It is also one of the most extensive types of Quaternary deposits11. According to the analysis of multi-source data, in the Chinese Loess Plateau (CLP) of north-central China, the widely developed ‘classic’ interbedded loess (L)-paleosol (S) sequences (LPS) (Fig. 1a–f), with similar initial background conditions12, and in turn controlled by shifts in regional climate, had stored abundant paleoenvironment and paleoclimate information and recorded shifts in the bioclimatic environment13,14,15. Consequently, LPS harbored one of the most valuable Cenozoic climate archives on land16,17,18, offering unique sites and opportunities for exploring the microbial responses to climate change over long-erm temporal scales.

a Location map of the study site, and b the landscape and loess–palaeosol sequence in Luochuan, c Yulin, d Hancheng (ref 51.), e Baqiao and f Lantian. Some images are adapted from SKJ Travel (https://www.skjtravel.net/index.php/component/content/article/337-the-eve-of-battle-traditional-village-lands-changing-on-china-s-loess-plateau).

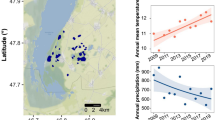

Microbial communities, particular soil bacterial and fungi, had a central role in ecosystem functioning by driving key biogeochemical cycles, such as nutrient cycling19,20, carbon (C) sequestration, and organic matter (OM) decomposition21,22. However, our understanding of how long-term climatic change influence their abundance and diversity remains limited10,23, and this knowledge gap is especially pronounced in arid and semi-arid regions24. Therefore, understanding how environmental microbiomes respond, adapt, and evolve after climate change is the core to our ability to identifying climate–ecosystem feedback. Moreover, this also poses a major challenge for assessing microbial and microbial-mediated biogeochemical cycles under future climate change and developing effective adaptation strategies23. Herein, we conducted a field study in the Luochuan section ( ~ 500 kyr) at the center of the CLP, covering the last five glacial–interglacial periods (from S0 to S5) (Fig. 1b), to assess how intense and long-term changes in climate influence the total soil bacterial and fungal abundance, the relative abundance of major taxa, and functional difference. Based on the availability of key resources, such as water and C25,26, we predicted that SOC acts as a primary controlling factor for the reduction of microbial abundance and diversity, and the formation of functional memory during paleoclimate dry and cold periods. To test the hypothesis, abiotic (e.g., climate proxy indicators of CaCO3, χfd and Rb/Sr ratio, and nutrient elements of C, N and P, and 15N) and biotic factors (e.g., bacterial and fungi diversity, communities, and bacterial function) were investigated, and the co-occurrence patterns of bacteria and fungi were explored in LPS, S and L soils respectively. These attributes largely determine the response of drivers of wet-dry climate change. We also collected the research data of Benthic δ18O stack of deep sea27, and MAP28, LST29 and climate proxy indicators CaCO3, χfd29 and Rb/Sr30 in LPS profile (Fig. 2a-f), for comparison. The specific questions answered included: 1) Do bacterial and fungal communities have legacy effects and responses consistently to dry-wet climate change? 2) What is the succession path and fate of microbial function after ten thousand years of drought stress? and 3) What are the possible mechanisms that influence soil microbiome records in wet and dry climates?

a Schematic diagram of Loess Stratum18 and reconstructed precipitation29. b Benthic δ18O stack. c Frequency magnetic susceptibility (χfd) (black line)29 and records from this study (blue points and fitted line). d CaCO3 conents in this study (blue points and fitted line). e Rb/Sr records, black line31, blue points and fitted line from this study. f 600 kyr land surface temperature (LST) records29. g 15N/14N and TN conduct and h Statistics of species annotation at family and genus levels in this study (blue points and fitted lines).

We found that owing to the recent input of nutrients in the shallow layer of LPS, the diversity and functional distribution of bacteria and fungi were consistent with other global studies31,32,33. However, in the deeper sequences, contrary to what was commonly assumed by theoretical approaches that OM rather than residual nitrogen drives long-term microbial patterns32, the observed soil TN (not SOC), and bacterial abundance, community structure and function followed alternating changes between L and S. And the extent and characteristics of past paleosoil biological activity reflected in soil N stocks rather than OM26,34. We think this knowledge gap may stem from the ecological temporal scale phenomena10. Furthermore, the S harbored more abundant and diversified microbial communities, in contrast, in L more Gammaproteobacteri, together with previous evidence35, which proved to contain strong N-fixing and assisting bacteria35, showed a strong N fixing-comammox-nitrate reduction ‘short circuit’ cycle path, which maintained the bacterial structural operation channel to inhibit the development of complex communities. Overall, our data revealed important N-conversion functions in the paleoclimatic loess microbiota. It demonstrates that climate change is a factor that can profoundly alter soil microbial communities’ structure and that their ultimate functional evolution tends to favor more energy-efficient, short N cycle paths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively analyze the formation and evolution of ecological memory in soil biogeochemical cycles mediated by soil microbial communities in long-term drought events over 10 kyr. Specifically, our work shows the key findings: (1) Bacterial abundance can be used as proxies for paleo-environmental biological reconstruction of long-term dry-wet shift; (2) soil TN15,N (abiotic), and bacterial abundance and function trait (biotic), exhibit climatic legacy effects within gene-regulatory network; (3) The functional evolution of bacterial soil memory is complex, and the time scale of functional stability could reach 10,000 years; We further suggest that Gammaproteobacteria mediated functional short-circuiting of nitrogen cycle in extremely arid environments may be a in long-term evolutionary strategy to stabilize microbial metabolism and cope with drought-induced nitrogen restriction.

Results

Consistent pattern of soil TN and δ15N with the climate proxies in deep LPS

In our data, the χfd, CaCO3 and Rb/Sr ratio data (climate proxy indicators) in LPS reflected shifts in climatic and environmental conditions in the past (Fig. 2c, d, e). Nutrient elements, such as SOC, TN, NH4+, NO3−, and TP were clearly divided into two distinct parts (Fig. 2g, Fig. S1).

In the deeper layers (L2-S5), only TN (150.70-278.50 mg kg−1) and δ15N (0.41-5.55) values, consistent with χfd (5.26–10.93%) and Rb/Sr (0.45–0.96) trends, were generally higher in the S layer compared to the adjacent L layer. TP concentrations exhibited oscillations (492.80–835.50 g kg−1) that were inversely related to the CaCO3 trends (94.26–135.40 g kg−1 in L and 1.20 –84.39 g kg−1 in S). All these parameters showed fluctuation cycles of approximately 10,000 years, which were highly consistent with previous research results on climate change indices presented in Fig. 2a, b, c, e, f.

Similarly, soil moisture (SM) was higher in the S layer than in the adjacent L layer (Fig. S1). However, SOC, NH4+-N, NO3–-N, and pH did not exhibit fluctuating trends, with SOC decreasing with increasing depth. Notably, in the shallow layers (GY-S1), the nutrient elements SOC (2.44-7.81 g kg−1), TN (270.50-1010.60 mg kg−1), NH4+-N (21.22-39.99 mg kg−1), NO3–-N (19.77-38.53 mg kg−1), and TP (0.49-2.17 mg kg−1) showed significantly higher values, increasing 2 to 4 times compared to the deep layers, while pH was considerably lower. This suggests that the deep layer primarily reflects historical climate shifts, while the shallow layer is more significantly influenced by recent nutrient inputs and varying limitations of carbon and nitrogen

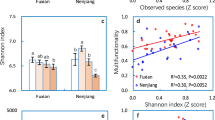

Obvious shifts patterns in bacterial total biomass, diversity and structure between L and S of deep layers

According to the qPCR results, bacterial gene copy numbers (8.09–9.82) were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those of fungal gene copy numbers (7.04–8.15). Both bacterial and fungal copy numbers, along with the Chao1 species richness index, were significantly greater in shallow layers compared to deep layers (p < 0.05). Furthermore, in deep layers, bacterial copy numbers (8.09–8.55), as well as Chao1 (45.67–911.69) and Shannon indexes (0.34–6.73), were generally higher in the S layer than in the adjacent L layer (Fig. 3a). Notably, the average genera and family composition of bacteria exhibited significant variations across L-S depositional cycles within the LPS (Fig. 2h), correlating with climatic factors χfd and Rb/Sr, showing higher values in S compared to adjacent L (Fig. 2e, f). In contrast, for fungi, copy numbers, Chao1, and the Shannon index (Fig. 3b) did not display a clear trend between the L and S layers.

At the community level, a total of 46 bacterial phyla were detected in the soil samples. Nine phyla had an average relative abundance greater than 1%, including unclassified taxa. Bacterial community composition varied significantly between shallow and deep layers. At the phylum level, in shallow layers (GY-S1), there was no notable structural difference in the top 10 taxa between L and S layers, except that Actinobacteria was relatively more abundant in L1-S1 (Fig. 3c). However, in deep layers (L2-S5), significant differences were observed between L and S. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria was higher in L (56.5%–97.5%) compared to S (12.8%–87.2%). Conversely, the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Gemmatimonadetes, and Planctomycetes were higher in S (2.4%–56.2%, 0.2%–14.4%, 0.1%–8.9%, 0.1%–8.7%, and 0.1%–3.6%, respectively) than in L (0.80%–38.84%, 0.1%–6.6%, 0.1%–6.7%, 0.1%–4.9%, and 0.1%–2.3%, respectively). At the class level, not only Gammaproteobacteria but also Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Oscillatoriales were enriched in the S layers of deep layers. In contrast, Gammaproteobacteria were abundant and notably dominant (P < 0.05) in L (Fig. 3e).

Among the 15 fungal phyla detected, three had relative abundances greater than 1%: Ascomycota (68.7%), Basidiomycota (13.4%), and Mortierellomycota (4.3%) (Fig. 3d). In shallow layers, Ascomycota was predominantly composed of Sordariomycetes, particularly in GY, where it accounted for 86.5%. In the deep layers (L2–S5), the classes Sordariomycetes, Dothideomycetes, Saccharomycetes, and Eurotiomycetes were uniformly distributed (13.4%–32.4%, 11.6%–16.8%, 7.0%–21.7%, and 8.1%–10.4%, respectively) (Fig. 3f). Compared to bacteria, the fungal community composition was relatively stable in the deep layers of S and L.

Additionally, the PCoA and analysis of similarities revealed that bacterial communities were significantly clustered at the ASV level (P < 0.01). Significant differences in microbial community composition were observed between shallow layers (GY-S1 for bacteria and GY-S0 for fungi) and deep layers (Figure S2a). Furthermore, fungal communities displayed the highest beta-diversity, indicating greater dispersion (Figure S2b). These results suggest that bacterial and fungal communities in shallow layers (GY-S1) may be more sensitive to modern nutrient inputs. In contrast, the effects of L (dry) and S (wet) cycles on the evolution of bacterial diversity, abundance, and structure in the less disturbed deep layers demonstrated a consistent pattern across different microbial lineages.

Much greater climate shift effect on the co-occurrence networks relationships of bacteria than fungi’s

Bacterial and fungal networks were constructed to determine the co-occurrence patterns of soil bacterial and fungal communities in LPS, with nodes and links calculated based on the robustness of the co-occurrence scores. In comparison to the bacterial network, the fungal network exhibited lower clustering coefficients, path lengths, and degrees. Notably, in the L and S of deep layers, the multiple topological properties of bacterial co-occurrence patterns showed greater variation than fungi, as indicated by the number of nodes and edges, average path length, and degree.

Utilizing the clustered bacterial and fungal network modules, we examined significant modular-trait relationships. According to the connectivity within and among modules (Z and P, respectively), Bacillaceae and Listeriaceae (Firmicutes), Halomonadaceae (Proteobacteria), and four unclassified bacteria (Fig. 4a) emerged as connector hubs within the entire LPS profile (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, in the S of deep layers, 12 bacterial connectors were identified, five of which were unclassified. The remaining seven belonged to Rhodospirillaceae and Hyphomicrobiaceae (Alphaproteobacteria), Nitrosomonadaceae (Betaproteobacteria), Streptomycetaceae and Pseudonocardiaceae (Actinobacteria), and Aneurinibacillus (Firmicutes) (Fig. 4c). In contrast, no connectors were identified in the deep L bacteria (Fig. 4d) and fungi (Fig. 4f), as well as in S fungi (Fig. 4e).

a, b The bacterial and fungal networks in 11 layers of S0 ~ S5. c, d The networks of bacteria in S and L in L2-S5, respectively. e, f The networks of fungi in S and L in L2-S5, respectively. A connection in bacteria stands for a correlation coefficient |r | > 0.7 and P < 0.01, and |r | > 0.5 and P < 0.05 in fungi. The keystone taxa (module hubs and connectors) and their connected edges in the networks are in bold. The size of each node is proportional to the number of connections (degree), and the thickness of each connection between two nodes (edge) is proportional to the value of Spearman’s correlation coefficients. The blue edges indicate positive interactions between two nodes, while red edges indicate negative interactions. The legend shows main modularity class in order of their relative amount. g Topological properties of microbial co-occurring networks in Modularity, Average clustering coefficient, Average path length and Average degree for bacterial and fungal of whole LPS layers (a and b); bacterial of deep S and L (c and d, respectively); fungi in deep S and L (e and f, respectively). h The variation of both phylogenetic diversity and taxonomic diversity of microbial β-nearest taxon index (betaNTI) and RCbray (Bray–Curtis-based Raup–Crick) values in Top and deep layers, respectively. i Give the percent of turnover in community composition governed primarily by variable selection, homogenizing dispersal, dispersal limitation and ecological drift.

In the deep S layers, primary bacterial modules 1, 2, and 4 were positively correlated with C and N contents and diversity, while modules 3, 5, and 6 exhibited significant positive and negative correlations with climatic factors, MAP and LST, respectively (Fig. 5a). The negative interactions suggested intense competition for nutrients among bacterial species. Conversely, in deep L, strongly connected modules 1 and 3 displayed negative correlations with C, N, and diversity, but positive correlations with climate indices. Additionally, the L network had a higher clustering coefficient and lower average path length and degree compared to the S network, indicating stronger inter-species assistance. These results suggest that microbial food webs in L are more interconnected than those in S.

a The correlation coefficients between module eigengenes, soil properties and paleoclimate substitution index. b, c Spearman correlations between environmental factors and bacterial and fungal diversity (qPCR, Chao1 and Shannon index) in GY ~ S1 and L2 ~ S5, respectively. The module eigengene of a module was defined as the first principal component of the standardized module expression data. The numbers in parentheses indicate the nodes observed in each module. SM, soil moisture; SOC, soil organic carbon; TP, total phosphorus; TN, total nitrogen; NH4+-N, ammonium nitrogen; NO3--N, nitrate nitrogen; χfd, frequency magnetic susceptibility. MAP, Reconstructed mean annual precipitation of Luochuan; LST, land surface temperature from Luochuan. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Regarding the fungal networks, in the deep S layers, primary modules 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 were significant negative correlated with C and N contents and diversity, while they exhibited significant positive and negative correlations (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) with climatic factors MAP and LST, respectively. Notably, correlations between models and environmental factors did not differ significantly in L (Fig. 5a). Collectively, these findings suggest that the nodes were influenced by modules associated with C, N, and climate.

Soil N recorded deep layers’ bacterial structure and function

In the shallow layers of GY ~ S1, moderate to strong alternating positive correlations were noted between SOC, total TN, TP, and both fungal abundance and diversity (Fig. 5b). Conversely, in the deeper layers (Fig. 5c), correlations between TN, δ15N, and climatic proxies (χfd, Rb/Sr, CaCO3, TP) with bacterial abundance and diversity exhibited moderate to strong alternating positive and negative trends. Notably, fungal abundance and diversity displayed a significant negative correlation with SOC (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). Overall, in the shallow layers, SM, TN, and SOC emerged as key properties influencing bacterial community structure, while in the deeper layers, TN were identified as the primary influence. Interestingly, in the shallow layers, TP acted similarly to TN as a nutrient; however, in the deeper layers, its effects on bacteria paralleled those of the climatic proxy CaCO3. This finding highlights the distinct differences between the nutrient-influenced shallow layers and the paleo-climatically affected deep layers. Redundancy analysis (RDA) diagrams further elucidated the visual distinctions between the bacterial and fungal communities in shallow and deep layers (Figure S2c, d). In the deep layers (L2 ~ S5), bacterial community structure was predominantly influenced by nitrogen nutrients (TN, NO3–-N), climatic factors (TP, CaCO3), and pH (Figure S2e). Excluding Enterobacteriaceae, the community structures of other dominant families were positively correlated with TN and NO3–-N, while SOC and SM emerged as major influencers on fungal community structure (Figure S2f). In contrast, bacterial and fungal structures in the shallow layers were predominantly shaped by a combination of C, N, and P nutrients. Additionally, the results indicated that climate indices had no direct effect on the dominant fungal community in either layer. Notably, the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae (Gammaproteobacteria) exhibited a significant exponential decrease with increasing TN and SOC levels across the entire landscape position (LPS) (p < 0.01, Fig. 3g, h), suggesting their prevalence under low nutrient conditions.

In the deeper layers, functional annotation predicted by FAPROTAX indicated that microorganisms involved in carbon and nitrogen conversion processes—such as chemoheterotrophy, nitrate reduction, nitrate respiration, nitrite respiration, nitrite ammonification, and nitrogen respiration—accounted for more than 85% of the microbial functional abundance in each layer. Moreover, the number of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) associated with nitrogen cycling functions was more than twice as high in the L layers compared to S layers (Fig. 6a). After L3, these functional characteristics exhibited sharp oscillations between L and S layers, closely aligned with Gammaproteobacteria. This suggests that a tightly connected module 1 was formed in the L layers (Fig. 4d), which showed significant negative correlation with C and N (Figs. 3g, h, 5a), indicating that loess selectively recruited highly conserved microorganisms dominated by Gammaproterbacteria. Notably, these patterns were absent in the shallow layers S and L (Figure S3). Furthermore, structural equation modeling (SEM) for the deep layers (L2-S5) indicated that climate had no significant direct impact on bacteria and fungi (Fig. 6d); rather, it affected bacterial community structure and abundance indirectly through soil N. These findings underscore the idea that, in the deeper layers, soil TN and the associated microbial communities bear a dynamic imprint of past climatic impacts.

Deep layers L-S sequences (L2-S5) a Heatmap of metabolic phenotypes/functions of bacteria, and b Heatmap of abiotic factors. The heatmap of metabolic phenotypes/functions of bacteria data based on OTUs occurrence (number of OTUs capable for each function) from L-S sequences (LPS) samples. c Nitrogen-reduction gene (nifK, copies g-1) and nitrogenase activity (U g-1) of L and S, reflecting the relative N-fixation potential of bacterial communities. d Structural equation modeling of climate and key soil properties on bacteria and fungi. Blue lines indicate positive relationships, while red lines indicate negative relationships. Paths with non-significant coefficients are presented as gray lines. The bacterial and fungal community are represented by the Shannon index. The indicators of latent variable ‘climate’ are MAP, χfd and Rb/Sr. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. e Nitrogen cycling driven by microorganisms in S and L, respectively (ref 12,36.). nif, nitrogenase; amo, ammonia monooxygenase; hao, hydroxyamine oxidoreductase; nxr, nitrate oxidoreductase; nar, nitrate reductase; nir and nrf, nitrite reductase; hh, hydrazine hydrolase; nor, nitric oxide reductase; nos, nitrous oxide reductase. The purple line represented the process of nitrogen fixation, the red line represented the process of nitrification, the yellow line represented the process of denitrification, the blue line represented the process of ammonification, the black line represented the process of anaerobic ammonification, and the dotted line represented the process of dissimilation nitrate reduction.

Discussion

The alternating occurrences of L and S layers in the LPS on the CLP are a result of glacial–interglacial climate cycles18. S reflects processes of pedogenesis, while several abiotic factors primarily influence χfd30, CaCO3 leaching12, Rb/Sr ratio30, TP36, and δ15N37, all of which have been extensively studied in recent decades. We demonstrated that climate-driven changes in Quaternary sediments are imprinted not only in their physical, geochemical, and isotopic properties but also in their biological characteristics. Specifically, we observed moderately positive correlations among bacterial species at the family and genus levels (Fig. 2h), indicating a clear imprint from wet-dry climate shifts. However, at the phylum and class levels, the composition of the top ten bacterial taxa varied significantly between the shallow and deep layers of LPS. Among the numerous abiotic variables, SM and higher nutrient levels (C, N, and P) were key factors influencing bacterial and fungal community structure in the shallow layers (Fig. 5b). Dominant groups included Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, and Acidobacteria, which align with global distributions31,38,39,40,41. In contrast, in the deep layers (L2–S5), Proteobacteria emerged as the most dominant taxon, with nitrogen compounds serving as major factors shaping sediment bacterial community structure (Fig. 5c). Particularly in the L layer, characterized by its highest dominance (Fig. 3c, e), deficiencies in C and N appeared to stimulate its abundance, allowing it to thrive in nutrient-limited conditions (Fig. 3g, h). This could explain the distinct correlations between the relative abundances of dominant taxa and nutrient levels.

Network topology reveals interactions among microorganisms in the deep L and S layers. Our analyses suggest that bacterial ASVs in the deep S layers exhibited significantly higher degrees and betweenness centrality values, indicating more intricate networks characterized by a greater number of nodes and potential edges42 (Fig. 4g). Furthermore, Rhodospirillaceae, Nitrosomonadaceae, and Hyphomicrobiaceae were highly interconnected (Fig. 4c). These keystone taxa may be essential drivers of community structure and ecosystem stability43,44. Conversely, microbial communities in the deep L layers displayed weak connectivity, primarily highlighting the internal cycling of module 1 (Fig. 4d). Loss of linking sites in co-occurrence networks can hinder succession to other species, thereby stabilizing the initial species composition within the bacterial community45,46. Consequently, drought-induced changes in bacterial activity and interactions in L could trigger various extinction events and lead to reduced biodiversity, forming decentralized local conservative networks.

In S layers, climate significantly shaped keystone taxa within bacterial networks, and these communities exhibited complex interactions in the co-occurrence networks. Phylogenetic diversity is anticipated to be enhanced by intra- and inter-specific competitive interactions within ecological communities47. Additionally, the coupling linkages between bacterial in L and fungal networks in L and S layers were largely positive in the co-occurrence networks (Fig. 4d-f), indicating that microbial populations within these networks share similar ecological niches and engage in symbiotic interactions to acquire nutrients48,49. This suggests mutualistic interactions for substrate acquisition. Notably, the abundance and diversity of fungi did not demonstrate significant differences between L and S layers (Fig. 3d, f, Figure S2d, f), highlighting the differing responses and preferences of bacteria and fungi to nutrient conditions (Fig. 5b, c)50. Our findings indicate differences of nutrient availability being responsible for the bacterial and fungal community legacy effects in top and deep dry-wet climate change, the fundamental components of L-layer bacterial networks may also represent late-stage functional evolution.

Based on bacterial abundance (Fig. 3c), co-occurrence patterns (Fig. 4c), and FAPROTAX predictions (Fig. 6a), here, we find the L selectively recruit highly conserved microorganisms dominated by Gammaproteobacteria, exhibited prominent nitrogen-related functions, largely compensating for nitrogen deficiency at these sites (Fig. 3g). To verify this hypothesis, we further measured nitrogen-fixing enzyme activity and the nitrogen-reduction gene (nifK) as indicators of the relative nitrogen-fixation and reduction potential of the bacterial communities. It presents, in the deeper layers (L2–S5), the proportions of nitrogenase and the nitrogen-reduction gene (nifK) were apparently higher in L than that of adjacent S (Fig. 6c), closely paralleled with Gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 3c). Especially from S2 downwards, as the SOC decreased and is less than 2 g kg-1 (Figure S1), the nitrogenase activity increase highly. These indicate that the higher abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in L was dominated by symbiotic nitrogen-fixing taxa that underpin prominent nitrogen-related functions. Importantly, the synergistic effects of Gammaproteobacteria communities have been confirmed by the recently studied in soils and plants51. Moreover, Zhang et al35. revealed specific details of the core microbial community embedded within the Gammaproteobacteria, verifying the endophytic nature and nitrogen-fixing function of the core taxa, including a large proportion of Klebsiella species with high nitrogenase activity. Some non-nitrogen-fixing core taxa with strong respiratory metabolic capacities (e.g., Acinetobacter sp. ACZLY512 and R. epipactidis YCCK550) facilitate biological nitrogen fixation by creating a micro-oxic environment favorable for the process7,52, while ammonia consumption also positively regulates the activation and transcription of nitrogen-fixation genes24,25,26. During dry–cold and warm–humid periods, the co-occurrence patterns of bacteria showed pronounced differences in nitrogen-cycling functions, and the changes in microbially mediated nitrogen functions may reflect drought-dependent adaptive strategies within these communities.

In conditions where primary production is limited by nitrogen, nitrogen-fixing organisms and their symbionts gain a substantial competitive advantage, often surpassing non-nitrogen-fixing organisms53. The activity of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacteria can increase nitrogen fixation, thereby balancing nitrogen availability with other resources, compensating for mechanisms that would otherwise lead to nitrogen limitation, and ultimately alleviating nitrogen deficiency across ecosystems54. Our study indicates that the evolution of microbial functions during dry periods are significantly constrained by nitrogen availability. Furthermore, the specific taxa in module 1 of deep L exhibited strong interconnections, and its network structure was environmentally stable (Fig. 4d), illustrating its greater contributions to network structure and diversity compared to poorly connected taxa55. Given these characteristics, we conclude that the microbial co-occurrence network model for L module 1 represents an internal circulation network of a highly conserved core nitrogen-fixing symbiotic microbial community dominated by Gammaproteobacteria, which encompasses highly efficient nitrogen-fixing and nitrogen-assisting bacteria51.

Here, we found that both abiotic (soil N) and biotic (nitrogen-fixing microorganisms) components left measurable legacies. The formation of ecological memory relies on such informational or material legacies8,17. This suggests that it was the drought-induced biological legacies led the differences in abundance and function compared with the humid periods, revealing a pronounced ecological-memory effect. In fact, previous studies have shown that drought-adapted microbial communities often increase the production of osmolytes46,47, enter dormancy, and form spores49. Integrated multiple lines of soil information—bacterial abundance, co-occurrence networks, functional predictions, enzyme activities, N amount, and their interrelationships—to evaluate the ecological memory of soil bacteria, we demonstrate a trade-off between the physiological responses within microbial communities under long-term drought, shifting metabolic investment toward drought-responsive coping mechanisms, such as nutrient storage49. The composition of soil microbial’ communities changes in response to shifts in their functions, and drought induces specific responses in nitrogen-related active enzymes, significantly intensifying the activities of nitrogen fixation and its associated symbiotic enzymes. The bacterial communities increased their investment in acquiring resources for nitrogen fixation, and different microbial members contributed synergistically to the nitrogen-fixing function, thereby forming ecological memory38.

The microbial functional evolution of soil memory is intricate and long-lasting10. Extended drought conditions lasting over a decade have been shown to enhance microbial diversity and soil abiotic versatility during dry spells, although no significant changes in microbial function were observed38. Thus, we propose that functional evolution in bacteria may require a longer timeframe. Our findings reveal that during dry periods, the functional evolution of bacteria at site L was notably driven by Gammaproteobacteria containing fixing nitrogen-comammox-nitrate reducing microorganisms. In the overall LPS, differences in microbial function began to emerge in L2, with functional evolution characteristics becoming more pronounced in the relatively dry L3 period (Fig. 6a). Accordingly, we suggest that the time required for microbial function divergence may operate on approximately 10,000 years, and that the genus level provides higher resolution for identifying bacterial life-history strategies and responses to environmental stressors (Fig. 2h). Given the limited temporal scope and site specificity of existing climate change research, this timeline cannot be accurately quantified. Nevertheless, while the duration of functional evolution and stabilization may vary across different nitrogen-available soil environments, our comparison of S and L indicates that drought-induced reductions in soil nitrogen input and availability may significantly shorten the evolution timeline.

The extent and characteristics of past biological activity in ecosystems are often reflected in the biogeochemical properties of soils. Warm and wet periods are thought to have supported abundant vegetation and high SOM levels56. However, our results reveal that SOC experienced abrupt shifts and generally low values in the deeper layers (L and S) over the last 500,000 years (Figure S1). This suggests accelerated SOM degradation during these favorable climatic conditions as soil evolved57. Supporting this inference, δ15N trends show more positive values in S soil compared to L layers (Fig. 2g). This isotopic enrichment likely reflects nitrogen mineralization of SOM and increased NH4+-N immobilization during the formation of S53. While past biological activity is generally reflected in SOM stocks rather than N and other elements26,32, the evolution of deep S-L cycles indicated significant N memory (Figs. 2g, 6c, d). We propose that this discrepancy might stem from time-scale issues, as OM has relatively short memories that affect ecosystems over decades to millennia10.

Nitrogen compounds were pivotal in shaping the sediment bacterial community structure (Fig. 6c). Under drought conditions, soil was inherently deficient in both C and N58. Over tens of thousands of years, the functional evolution of bacterial have ultimately resulted in the establishment of a relatively stable and conserved nitrogen-fixation–nitrogen-reduction shortcut cycle in the L layers. Biological N2 fixation is believed to be the primary source of N, contributing more than 97% of N input in natural terrestrial ecosystems59,60. In N-limited L, N-fixing and symbiotic microorganisms would gain a competitive advantage by jointly fixed N to alleviate N limitations in the ecosystem61,62, thereby altering community composition and enhancing functional adaptation in nutrient-poor conditions63,64. This process of symbiotic N-fixation in C and N-limited sites was subsequently reversed53,65. Therefore, a key nitrogen-cycling mechanism, nitrogen fixation–ammonia oxidation and nitrate reduction co-metabolism–re-fixation, emerges as a critical adaptation strategy in response to drought23,66.

Soil memory represents a core component of Earth system dynamics and the co-evolution of land surfaces and climate10. Historical climate processes have shaped specific soil types and regional species pools, thereby influencing species sorting and biotic interactions23,67,68,69. Temporal phenomena are fundamental to ecology8,9, ecosystem responses to new disturbances may reflect the history of previous extreme events38. In this context, ecological memory70 is crucial for predicting the disruptive effects of climate change on ecosystems. Our findings indicate that environmental filtering, species sorting, and biotic interactions significantly shape bacterial assembly within the LPS71 (Fig. 4h, i). The community assembly processes and correlation between community structure, paleosol age, and chemical content suggests that environmental selection and drift are influential forces in the bacterial assembly process of deep layer (Fig. 6a, b). Notably, we observed that the responses of bacterial species abundance, community composition, and functional evolution to climatic shifts were consistent, all reflecting strong biological legacies and abiotic legacies (TN) (Fig. 2g, h). The functioning of microbial systems is intrinsically linked to global climate change. Drought, as a primary filtering factor, inevitably diminishes bacterial diversity, potentially leading to local extinction or replacement of keystone species. In the context of biochemical evolution in deep layers of soil, sufficient time and appropriate diffusion mechanisms allowed the establishment of N-fixing symbiotic bacteria (Gammaproteobacteria) in the regional species pool. This shift altered the composition and function of soil bacterial communities, driving a more energy-efficient “N cycle end-stage pathway mechanism” and promoting nitrogen memory in the soil (Fig. 6e).

Regardless of environmental changes, historical processes leave an indelible mark on community composition, corroborated by the presence of endemic taxa72. Our results provide clear evidence of climate change feedback through shifts in soil microbial diversity and functions within the deep LPS. Unlike previous global surveys of terrestrial ecosystems33, our study found that bacterial communities in L were predominantly composed of N-fixing symbiotic bacteria (Gammaproteobacteria), which mitigate N limitation under drought conditions. Importantly, bacterial diversity serves as a valuable indicator of climatic impacts in the undisturbed deep LPS, providing the temporal resolution necessary to discern interactions across varying time scales and climatic conditions. Our findings underscore the uniqueness of microbial community evolution trajectories and their associated time scales. Furthermore, our data illuminate the intricate connections between soil N memory, bacterial community functions, and climate, illustrating how these factors form a complex adaptive system over time and space. We emphasize the importance of N storage for microbial community evolution, the maintenance of microbial co-occurrence networks, and the potential risks that long-term drought poses to microbial ecological environments.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites and sample collection

Luochuan (LC) Loess section, located in Potou village, Luochuan County, Shaanxi Province, China (109°25′E, 35°45′N), is approximately 138 m thick (Fig. 1b). The entire LPS includes 38 loess and paleosol layers, spanning the interval from ~2.5 Ma BP to the present73,74. In the LPS, alternating layers represented the cycles of glacial–interglacial deposition17 (Fig. 2a). The age scale was established by exploring correlation between the frequency magnetic susceptibility (χfd) data and the SPECMAP marine δ18O record75 (Fig. 2a, b). And the S in the LPS formed during the interglacial period when the climate conditions were thought to be warm and humid. Meanwhile, the L was considered cold and dry condition73,74 (Fig. 2a). Here, the most complete paleoclimate archives were preserved, and potential confounding factors were reduced to a notable minimum74, especially below the S1 layer76.

A total of 78 samples were collected from the upper 50 m in May 2019 and October 2020 in Luochuan. From S0 to S5, which spans the past 500 kyr77, three random samples were collected in each layer. The Luoyang shovel was used to dig a hole 50 cm deep and 10 cm diameter horizontally, and then reach into the bottom to collect the soil samples with small wooden wedges. In addition, soil samples were collected in the upper, middle, and lower layers of S4 and S5 in 2018, and in the S0 and apple orchard (GY) in 2019, respectively.

All samples were sieved (2-mm pore size) and the stones and roots removed to improve soil homogeneity. The sieved samples were stored at 4 °C in preparation for analyses. The bioinformatics samples (quantitative PCR [qPCR] and gene sequencing) were all collected in 50-mL centrifuge tubes, and maintained at –20 °C in preparation for DNA extraction. All soil samples were analyzed within two weeks of collection.

Soil physiochemical characterization

SM was determined by drying in 105°C for 12 h. Soil pH was measured using a DMP-2Mv/pH meter (Quark Ltd, Nanjing, China) after extraction with 1:2.5 (w v-1) soil: water. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was analyzed by the potassium dichromate oxidation method, and soil total nitrogen (TN) was quantified by semi-micro Kjeldahl digestion with selenium (Se), copper sulfate, and potassium sulfate as the catalysts. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N) were extracted by 2M KCl with a soil solution ratio of 1:10 and placed on a mechanical shaker at 300 rpm at 25 °C for 30 min. The extract was filtered by filter paper, and then the concentrations of NH4+-N and NO3–-N were determined by a continuous flow analyzer (Skalar, Breda, the Netherlands). Soil total phosphorus (TP), rubidium (Rb), and strontium (Sr) were determined by wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Soil frequency (χfd) was measured using an MS-2B MS meter. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) contents were determined using the gas method. The δ15N values used a KNO3 (δ15N = 6.27‰) and an international isotope reference material (IAEA-N3; δ15N = 4.70‰) to control the accuracy of the Elemental Analysis by Isotope Ratio Mass Spectroscopy. The standard deviation for repeated sample analyses was greater than 0.3‰.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and Illumina sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using a DNeasy® PowerSoil Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of extracted DNA were measured by NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and DNA quality was determined by 1.2% agar-gel electrophoresis.

The primers 515 F (5’-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and 806 R (5’-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were used to amplify the V4 hypervariable region of 16 s rRNA gene78, whereas primers ITS5F(5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’) and ITS2R (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’ were used to amplify the internal spacer 1 (ITS1) region of the fungal79. The fungi PCR master mix for each 25-µL reaction included 5 µL of 5× reaction buffer, 5 µL of 5× GC buffer, 2 µL of dNTP (2.5 mM), 1 µL of Forward primer (10 µM), 1 µL of Reverse primer (10 µM), 2 µL of DNA Template, 8.75 µL of ddH2O, and 0.25 µL of Q5 DNA Polymerase. Bacterial PCR amplicons were purified using Vazyme VAHTSTM DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) and quantified by the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). See the Xie et al. (2021) for detailed processing.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

To assess the copy numbers of bacterial 16 s rRNA genes and fungal ITS1 regions in the second soil sample, qPCR was performed using a TIB-8600 Real-Time PCR system (Triplex International Biosciences, Fujian, China) Primers were 341 F:5’- CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’/518 R: 5’-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG -3’ and ITS5F: 5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’/ITS2R: 5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’. Copy numbers were quantified by comparing the period during which fluorescence crossed the threshold with a standard curve constructed using continuous dilution of plasmids containing the appropriate template. Each sample was tested in duplicate, and each run included a standard and a negative control80.

Sequencing analysis

Raw sequence data of bacteria and fungi in the second time soil sample were demultiplexed using the “demux” plugin, followed by primer-cutting with the “cut-adapt” plug-in81. The “DADA2” plug-in (Callahan et al., 2016) was then used to perform quality filtering, de-noising, merging, and removing chimeric sequences to obtain amplified sequence variation (ASVs). Using the SILVA Release 132 (bacteria) and UNITE Release 8.0 (fungi) databases, high quality sequences were identified via RDP classifier82.

Assessment of soil nitrogen cycling potential

Soil nitrogen cycling potential was evaluated by assessing two key indicators: nitrogen reduction capacity, estimated via the absolute abundance of the nitrite reductase gene (nirK), and nitrogen fixation capacity, determined through measuring nitrogenase activity.

For the quantification of nirK gene abundance, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using an ABI7300 Fluorescence Quantitative PCR System (Applied Biosystems Inc., USA) with the SYBR Green I dye method83,84. Total genomic DNA was first extracted from soil samples, and the nirK gene fragment was amplified using the specific primers nirK-C2F (5’-TGCACATCGCCAACGGNATGTWYGG-3’) and nirK-C2R (5’-GGCGCGGAAGATGSHRTGRTCNAC-3’). The total reaction volume was 10 µL, consisting of 5 µL of ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR Master Mix (2×, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China), 0.4 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.2 µL of 50× ROX Reference Dye 1, 1 µL of template DNA, and 3 µL of ddH₂O. The thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; a melting curve analysis was subsequentlyconducted to verify the specificity of amplification products. For absolute quantification, a standard curve was constructed using 10-fold serial dilutions (from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁸) of a recombinant plasmid (pMD18-T vector, 2692 bp) containing the target nirK gene fragment (465 bp), and the gene concentration of each sample was calculated based on this curve.

Nitrogenase activity in soil samples was measured an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, assay kit: YJ699610, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). For sample preparation: soil specimens stored at -20 °C were thawed at 2 °C–8 °C, homogenized at 1:9 (w v-1, soil: PBS pH7.4) with a homogenizer, centrifuged at 2000–3000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected as the test sample (sodium azide (NaN₃) was avoided to prevent HRP inhibition). Prior to the assay: 20× wash solution was diluted 1:20 with distilled water, all liquids were shaken well; microplate strips (equilibrated at room temperature for 20 min) were taken, unused strips sealed and stored at 4 °C. Assay steps: ① Add 50 μL standards (0–240 U L-1) to standard wells, 10 μL supernatant + 40 μL sample diluent (5-fold dilution) to sample wells, and nothing to blank wells; ② Add 100 μL HRP-labeled antibody to non-blank wells, seal plates and incubate at 37 °C for 60 min; ③ Wash wells five times (manually: fill with diluted wash solution, stand 1 min, decant and blot dry; automatically: 350 μL wash solution/well, stand 1 min); ④ Add 50 μL each of Substrate A and B, incubate at 37 °C in dark for 15 min; ⑤ Add 50 μL stop solution (color turns blue to yellow), measure absorbance at 450 nm within 15 min. For calculation: an Excel standard curve (X: standard concentration, Y: OD value) was plotted, and the actual activity was obtained by multiplying the diluted concentration (from the curve) by 5.

Bacterial function prediction and phylogenetic community composition

Prokaryotic taxa (FAPROTAX) analysis was used to predict microbial functional groups. First, quality pruning, equivalent sequence assembly and chimera removal were performed on the original data series. Clustering sequence generation operation classification (OTU) with similarity ≥97%, then the remaining abundance tables were constructed and classified using the Greengenes database85. After matching with FAPROTAX database, OTU was labeled with functional information86.

To characterize the phylogenetic community composition of upper and lower soils, combining spatio-temporal data and environmental parameters of microbial communities with zero-sum models of phylogenetic composition within and between communities (Webb, 2000), we quantified the nearest taxa index (betaNTI) and Bray–Curtis-based Raup–Crick (RCbray)87, to describe the processes that control the composition of ecological communities, and understand changes in the relative effects of stochastic and deterministic processes. A detailed description of is provided in researches of Stegen88 and Jiao et al. 89.

Climatic data and statistical analyses

The mean annual precipitation (MAP)28 and mean annual temperature (MAT)29 datasets were used to evaluate correlations between climate and microbial community records in LPS (Fig. 2a, f).

Logarithmic transformation of microbial gene copy numbers was performed before their statistical analysis. Sequence data analyses were mainly performed using the QIIME2 and R software packages v4.0.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The α diversity indices of OTU and ASV-level, such as Chao1 richness and Shannon diversity index, were calculated by using the OTU/ASV table in QIIME2. The Bray-Curtis index was used for Beta diversity analysis to investigate variation in microbial community structures among samples, and visualized via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). Spearman correlation analysis and redundancy analysis (RDA) were calculated using the “states” and “vegan” R packages. Network analysis was done using the “igraph” package, based on the top 100 ASVs that had been filtered out and had occurrence frequencies > 5. And Gephi v0.9.2 (https://github.com/gephi/gephi/releases/download/v0.9.2/gephi-0.9.2-windows.exe) was used to visualize the co-occurrence networks. Two topological parameters were used to estimate the roles of node: within-module connectivity, Zi, quantified the degree of connectivity to other nodes in its own module, and among-module connectivity, Pi, quantified the degree to which node was connected to different modules90. Nodes with high Zi or Pi values were defined as keystone taxa, including module hubs (Zi > 2.5, Pi ≤ 0.62), connectors (Zi ≤ 2.5, Pi > 0.62) and network hubs (Zi > 2.5, Pi > 0.62)91.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the direct and indirect effects of climate index and nutrients on microbial community structure. SEM analysis was performed using AMOS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), the robust maximum likelihood evaluation method. The fitness was examined by non-significant chi-square test (P > 0.05), goodness of fit index and root mean square error of approximation92.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data can be found at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17688824.

References

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Chang 4, 17–22 (2014).

Bálint, M. et al. Cryptic biodiversity loss linked to global climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang 1, 313–318 (2011).

Bellard, C., Bertelsmeier, C., Leadley, P., Thuiller, W. & Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 15, 365–377 (2012).

Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nat 486, 59–67 (2012).

Isbell, F. et al. High plant diversity is needed to maintain ecosystem services. Nat 477, 199–202 (2011).

Penuelas, J. et al. Evidence of current impact of climate change on life: a walk from genes to the biosphere. Glob. Chang Biol. 19, 2303–2338 (2013).

Labouyrie, M. et al. Patterns in soil microbial diversity across Europe. Nat. Commun. 14, 3311 (2023).

Ogle, K. et al. Quantifying ecological memory in plant and ecosystem processes. Ecol. Lett. 18, 221–235 (2015).

Walker T. W. N., et al. A systemic overreaction to years versus decades of warming in a subarctic grassland ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 101–108 (2020).

Rahmati, M. et al. Soil is a living archive of the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 421–423 (2023).

Pécsi, M. Loess is not just the accumulation of dust. Quat. Int 7-8, 1–21 (1990).

Sun, Y. B., An, Z. S., Clemens, S. C., Bloemendal, J. & Vandenberghe, J. Seven million years of wind and precipitation variability on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Earth Planet Sc. Lett. 297, 525–535 (2010).

An, Z. S. The history and variability of the East Asian paleomonsoon climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 171–187 (2000).

Liu, T. S. Loess and Environment (in chinese). J. Xi’ Jiaotong Univ. 22, 7–12 (2002).

Lehmkuhl, F., Zens, J., Krauss, L., Schulte, P. & Kels, H. Loess-paleosol sequences at the northern European loess belt in Germany: Distribution, geomorphology and stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 153, 11–30 (2016).

Liu T. S. Loess and the environment (in Chinese). pp. 44–106 (China Ocean Press, 1985).

An, Z. S. et al. The long-term paleomonsoon variation recorded by the loess-paleosol sequence in Central China. Quatern Int. 7–8, 91–95 (1990).

Maher, B. A. Palaeoclimatic records of the loess/palaeosol sequences of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 154, 23–84 (2016).

Torsvik, V. & Øvreås, L. Microbial diversity and function in soil: from genes to ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5, 240–245 (2002).

van der Heijden, M. G., Bardgett, R. D. & van Straalen, N. M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 11, 296–310 (2008).

Fierer, N. et al. Reconstructing the microbial diversity and function of pre-agricultural tallgrass prairie soils in the United States. Sci 342, 621–624 (2013).

Zhou, J. et al. Microbial mediation of carbon-cycle feedbacks to climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 106–110 (2012).

Hutchins, D. A. et al. Climate change microbiology — problems and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 17, 391–396 (2019).

Maestre, F. T., Salguero-Gomez, R. & Quero, J. L. It is getting hotter in here: determining and projecting the impacts of global environmental change on drylands. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 3062–3075 (2012).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Decoupling of soil nutrient cycles as a function of aridity in global drylands. Nature 502, 672–676 (2013).

Flanagan, P. W. & Cleve, K. V. Nutrient cycling in relation to decomposition and organic-matter quality in taiga ecosystems. Can. J. For. Res. 13, 795–817 (1983).

Lisiecki L. E., Raymo M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, 1071 (2005).

Liu, Z., Wei, G., Wang, X., Jin, C. & Liu, Q. Quantifying paleoprecipitation of the Luochuan and Sanmenxia Loess on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 459, 121–130 (2016).

Lu, H. et al. 800-kyr land temperature variations modulated by vegetation changes on Chinese Loess Plateau. Nat. Commun. 10, 1958 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Distribution of Rb and Sr in the Luochuan loess-paleosol sequence of China during the last 800 kaI-mplications for paleomonsoon variations (In Chinese). Sci. China Ser. D: Earth Sci. 42, 225–232 (1999).

Fan, K. et al. Soil pH correlates with the co-occurrence and assemblage process of diazotrophic communities in rhizosphere and bulk soils of wheat fields. Soil Biol. Biochem 121, 185–192 (2018).

Hunt, H. W., Ingham, E. R., Coleman, D. C., Elliott, E. T. & Reid, C. P. P. Nitrogen limitation of production and decomposition in prairie, mountain meadow, and pine forest. Ecology 69, 1009–1016 (1988).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Sci 346, 1256688 (2014).

Alexander M. Introduction to Soil Microbiology. vol. 125 (WordPress, 1978).

Zhang, L. et al. A highly conserved core bacterial microbiota with nitrogen-fixation capacity inhabits the xylem sap in maize plants. Nat. Commun. 13, 3361 (2022).

Rao, W., Chen, J., Luo, T. & Liu, L. Phosphorus geochemistry in the Luochuan loess section, North China and its paleoclimatic implications. Quat. Int 144, 72–83 (2006).

Liu, J. & Liu, W. Soil nitrogen isotopic composition of the Xifeng loess-paleosol sequence and its potential for use as a paleoenvironmental proxy. Quat. Int 440, 35–41 (2017).

Canarini, A. et al. Ecological memory of recurrent drought modifies soil processes via changes in soil microbial community. Nat. Commun. 12, 5308 (2021).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil. Sci 359, 320–325 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Impact of 25 years of inorganic fertilization on diazotrophic abundance and community structure in an acidic soil in southern China. Soil Biol. Biochem 113, 240–249 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Soil pH is a major driver of soil diazotrophic community assembly in Qinghai-Tibet alpine meadows. Soil Biol. Biochem 115, 547–555 (2017).

Greenblum, S., Turnbaugh, P. J. & Borenstein, E. Metagenomic systems biology of the human gut microbiome reveals topological shifts associated with obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 594–599 (2012).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 567–576 (2018).

Rafrafi, Y. et al. Sub-dominant bacteria as keystone species in microbial communities producing bio-hydrogen. Int J. Hydrog. Energy 38, 4975–4985 (2013).

Barberán, A. & Casamayor, E. O. Global phylogenetic community structure and β-diversity patterns in surface bacterioplankton metacommunities. Aquat. Micro. Ecol. 59, 1–10 (2010).

Wu, L. et al. Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nat. Microbiol 7, 1054–1062 (2022).

Violle, C., Nemergut, D. R., Pu, Z. & Jiang, L. Phylogenetic limiting similarity and competitive exclusion. Ecol. Lett. 14, 782–787 (2011).

Layeghifard, M., Hwang, D. M. & Guttman, D. S. Disentangling interactions in the microbiome: a network perspective. Trends Microbiol. 25, 217–228 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Competitive interaction with keystone taxa induced negative priming under biochar amendments. Microbiome 7, 77 (2019).

Woodward, G. et al. Body size in ecological networks. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 402–409 (2005).

Zhu, Z. et al. Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago. Nat 559, 608–612 (2018).

Murali, R. et al. Diversity and evolution of nitric oxide reduction in bacteria and archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2316422121 (2024).

Vitouse P. M., Howarth R. W. Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea: how can it occur? Biogeochemistry 13, 85–115 (1991).

Vitousek, P. M. & Matson, P. A. J. E. Disturbance, nitrogen availability, and nitrogen losses in an intensively managed loblolly pine plantation. Ecol 66, 1360–1376 (1985).

Zhao, L. et al. Weighting and indirect effects identify keystone species in food webs. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1032–1040 (2016).

Lu, H., Liu, W. & Sheng, W. Carbon isotopic composition of branched tetraether membrane lipids in a loess-paleosol sequence and its geochemical significance. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 504, 150–155 (2018).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Biotic interactions mediate soil microbial feedbacks to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7033–7038 (2015).

Deng, L. et al. Drought effects on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics in global natural ecosystems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 214, 103501 (2021).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Sci 320, 889–892 (2008).

Kumar, U. et al. Long-term aromatic rice cultivation effect on frequency and diversity of diazotrophs in its rhizosphere. Ecol. Eng. 101, 227–236 (2017).

Shao, Y.-H. & Wu, J.-H. Comammox Nitrospira species dominate in an efficient partial Nitrification–Anammox bioreactor for treating ammonium at low loadings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 2087–2098 (2021).

Van Kessel, M. A. et al. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nat 528, 555–559 (2015).

Elser, J. J. et al. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135–1142 (2007).

Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. et al. The application of ecological stoichiometry to plant–microbial–soil organic matter transformations. Ecol. Monogr. 85, 133–155 (2015).

Kuypers, M. M. M., Marchant, H. K. & Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 263–276 (2018).

Adeolu, M., Alnajar, S., Naushad, S. & Gupta, S. R. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 66, 5575–5599 (2016).

Hanson, C. A., Fuhrman, J. A., Horner-Devine, M. C. & Martiny, J. B. H. Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 497–506 (2012).

Morlon, H. et al. A general framework for the distance-decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecol. Lett. 11, 904–917 (2008).

Ricklefs, R. E. A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 7, 1–15 (2003).

Padisák, J. Seasonal succession of phytoplankton in a large shallow lake (Balaton, Hungary)–A dynamic approach to ecological memory, its possible role and mechanisms. J. Ecol. 80, 217–230 (1992).

Louca, S. et al. Function and functional redundancy in microbial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 936–943 (2018).

Gao, Q. et al. The spatial scale dependence of diazotrophic and bacterial community assembly in paddy soil. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 28, 1093–1105 (2019).

Kukla, G. & An, Z. Loess stratigraphy in Central China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 72, 203–225 (1989).

Liu T., Ding Z. Chinese loess and paleomonsoon. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 26, 111–145 (2003).

Porter, S. C. & Zhisheng, A. Correlation between climate events in the North Atlantic and China during the last glaciation. Nat 375, 305–308 (1995).

Huang, T., Pang, Z., Liu, J., Ma, J. & Gates, J. Groundwater recharge mechanism in an integrated tableland of the Loess Plateau, northern China: insights from environmental tracers. Hydrogeol. J. 25, 2049–2065 (2017).

Ding, Z. L. et al. Magnetostratigraphy and sedimentology of the Jingchuan red clay section and correlation of the Tertiary eolian red clay sediments of the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Geophys Res: Solid Earth 106, 6399–6407 (2001).

Walters W., et al. Improved bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V4 and V4-5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys. mSystems 2015, 1: https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00009-00015.

White T., et al. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Biology 31, 315–322 (1990).

Walker, N. J. Real-time and quantitative PCR: applications to mechanism-based toxicology. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 15, 121–127 (2001).

Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 200 (2011).

Koljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271–5277 (2013).

Castellano-Hinojosa, A., González-López, J. & Bedmar, E. J. Distinct effect of nitrogen fertilisation and soil depth on nitrous oxide emissions and nitrifiers and denitrifiers abundance. Biol. Fert. Soils 54, 829–840 (2018).

Gillespie, C. J. et al. Multi-amplicon nitrogen cycling gene standard: an innovative approach for quantifying N-transforming soil microbes in terrestrial ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 195, 109461 (2024).

Lan, Y., Wang, Q., Cole, J. R. & Rosen, G. L. Using the RDP classifier to predict taxonomic novelty and reduce the search space for finding novel organisms. PLoS One 7, e32491 (2012).

Yang, Z. et al. Microbial functional assemblages predicted by the FAPROTAX analysis are impacted by physicochemical properties, but C, N and S cycling genes are not in mangrove soil in the Beibu Gulf, China. Ecol. Indic. 139, 108887 (2022).

Webb CO. Exploring the phylogenetic structure of ecological communities: An example for rain forest trees. Am. Nat. 156, 145–155 (2000).

Stegen, J. C. et al. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 7, 2069–2079 (2013).

Jiao, S., Yang, Y., Xu, Y., Zhang, J. & Lu, Y. Balance between community assembly processes mediates species coexistence in agricultural soil microbiomes across eastern China. ISME J. 14, 202–216 (2020).

Guimerà, R. & Nunes Amaral, L. A. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433, 895–900 (2005).

Olesen, J. M., Bascompte, J., Dupont, Y. L. & Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19891–19896 (2007).

Byrne B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. (Rouledge, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank professor Ravi Naidu (Energy and Resources Global Center for Environmental Remediation (GCER), University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia) for assistance review and editing. The Soil sample collection is supported by the Luochuan Loess National Geopark. Yiguo Hong (Institute of Environmental Research at Greater Bay Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China) provided the protocols for DNA extraction, amplification and library preparation, used to develop the DNA extraction and amplification and Metabarcoding library preparation parts of the Methods section. We further thank Chaochao Guo, Yan Qi, Guixiang Ma and Pengfei Hei assistance in the laboratory. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42372288, 41901034 and 41877179), the Central University Special Fund (300102294903), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (2023-JC-YB-280) and the Forestry Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shaanxi Province (SXLK2022-06-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-X.L. designed and coordinated the study, conducted data analysis and synthesis and wrote the paper. Y.C. and J.L. collected and arranged the data. M.-Y.H., S.H., J.H., W.G., C.Z., A.H., Y.L., and X.L. collected the data and carried out the case study. Z.L., T.W., Y.G., and L.H. arranged the data. Y.M. designed and coordinated the study, conducted the data analysis and revised the paper. Y.H. and M.T. revised the paper. All the co-authors reviewed and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Lei Deng and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: José Luis Iriarte Machuca, Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Chen, Y., Lu, J. et al. Ultimate soil nitrogen microbial function evolution pathway fixation–comammox–nitrate reduction in long–term arid. Commun Earth Environ 7, 64 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03085-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03085-4