Abstract

Precipitation variability in the Mediterranean Basin has traditionally been attributed to large-scale Atlantic climate modes, particularly the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). However, over key regions such as the Italian Peninsula, NAO-based interpretations often fall short in explaining observed hydroclimatic patterns. In this study, we combine deep learning reconstruction of historical precipitation records from 1950 to 2020 with the analysis of atmospheric teleconnection indices and air mass back-trajectory modelling. Using a dataset of more than eleven thousand rain gauge time series, we developed neural network models to produce a continuous and high-resolution precipitation dataset for Italy. Our results demonstrate that Mediterranean teleconnections, especially the Mediterranean Oscillation Index (MOI) and the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO), exert a stronger and more consistent influence on precipitation compared to the NAO. Trajectory analysis using the HYSPLIT model reveals that the Western Mediterranean is the dominant moisture source for central and northern Italy, while the Ionian and Eastern Mediterranean regions become increasingly important in the southern part of the country. These findings underscore the central role of Mediterranean cyclogenesis in shaping regional precipitation dynamics and call for a reassessment of climate interpretation frameworks that have traditionally focused on Atlantic influences alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mediterranean is a geographical area identified as a climate hot-spot1,2, which may have significant implications for a region of high social, economic, cultural, and environmental importance, among the most relevant in the world. Several studies have highlighted possible changes in rainfall patterns, attributed to ocean warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions3,4,5,6. Rising temperatures are expected to affect the intensity and location of cyclogenetic centres7,8,9,10, with potential consequences for the amount and intensity of precipitation events11,12. Mediterranean precipitation is strongly linked to cyclonic systems, which control both the intensity and spatial distribution of rainfall events. Several studies have quantified the contribution of cyclones to precipitation and moisture transport in the region, showing that extratropical and Mediterranean cyclones are responsible for a large fraction of rainfall variability13,14,15. Moreover, projected hydrological changes and increasing population are expected to raise the anthropogenic pressure on groundwater resources16,17,18,19,20,21, which constitute the primary source of drinking water in many regions worldwide22.

To fully understand these precipitation and atmospheric circulation patterns, it is essential to analyse long-term historical series, in order to overcome short-term climate variability23. However, the study of long-term observed data presents numerous challenges that must be addressed to conduct comprehensive climate analyses24. First and foremost, the analysis of long historical observational series is often hindered by data discontinuity and incompleteness23,24. These issues can arise from temporary or prolonged malfunctions, changes in measurement sensors, or the relocation of monitoring stations24. Although many countries have a good historical archive in terms of the number of stations and the length of the series25, detailed analysis of such data often proves complex and problematic.

One possible strategy is to focus on a limited number of selected stations, known as best time series, which allow for consistent analysis over time. However, a low spatial density of measurement points may be insufficient to represent the full climatic variability of the study area, instead reflecting only the characteristics of limited portions of the territory.

The climatic complexity of the Mediterranean basin requires overcoming these obstacles in order to carry out new analyses that can more clearly outline the drivers behind variations in climate patterns. Numerous studies have found statistical correlations between the North Atlantic Oscillation26 and precipitation27,28,29,30, while others have emphasised the importance of alternative climate indices representing broader-scale atmospheric circulation in the Northern Hemisphere, such as the East Atlantic Pattern8,31, or teleconnections more directly related to Mediterranean cyclogenesis, such as the Mediterranean Oscillation Index (MOI)32,33 or the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO)33,34,35. However, no statistically strong correlations have been found for Italy with NAO29,30,36, highlighting the need to identify more complex patterns.

Several studies conducted in the Mediterranean, analysing paleo-variations in rainfall or river regimes over centennial and millennial timescales, compare geological proxies with reconstructions of the region’s main recognised climate driver: the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)37,38. However, many cases show that the relationship between the reconstructed NAO and wet or dry periods is not consistent27,29,30, particularly in some areas such as Italy36,39,40.

This suggests that geological proxies point to the influence of additional climate patterns involved in the complex balance of Mediterranean atmospheric circulation, affecting the distribution of rainfall.

Despite numerous studies, a clear understanding of how different large-scale circulation modes interact in modulating regional precipitation variability is still lacking. This highlights a knowledge gap that the present work aims to address through an integrated analysis combining long-term observational data and atmospheric circulation indices, in order to identify the mechanisms controlling Mediterranean rainfall variability beyond the traditional NAO framework.

Some isotopic studies of precipitation in the Tyrrhenian side of Central Italy indicated the western Mediterranean as the primary moisture source associated with precipitation events41,42, with smaller contributions from the North Atlantic Ocean and continental regions. These evidences were consistent with results from other investigations43,44 identified the Western Mediterranean Sea as the main moisture source region for Mediterranean areas during the wet season from October to March. Conversely45, indicated a lower influence of the Mediterranean than the Atlantic sources (<10% in all seasons), whereas46 found a predominant contribution from the Mediterranean Sea in the warm season.

This study aims to address the scientific gap identified through an innovative approach that integrates deep learning modelling of the largest national precipitation dataset to investigate the synoptic-scale atmospheric patterns associated with precipitation over the Mediterranean region. The starting dataset come from a rainfall dataset repository for Italy composed of more than 11,000 measurement stations. As is often the case with historical climate series, these data are characterised by fragmentation and discontinuities (Fig. 1). To address overcome this issue, we developed deep learning models capable of reconstructing a regular grid of rainfall data for every point of the Italian territory, covering the period from 1950 to 2020. The reconstructed data were then analysed about synoptic atmospheric conditions, exploring the influence of both Atlantic and Mediterranean circulations. This analysis was coupled with a modelling of air mass trajectories and moisture uptake diagnostics, using HYSPLIT47,48, to identify the main moisture source regions.

The combination integration of these two methodologies allows for a better understanding of the origins and atmospheric circulation dynamics responsible for precipitation events along the Italian Peninsula, located strategically at the heart of the Mediterranean.

Results

AI-reconstructed rainfall time series

The Fig. 2 depicts the performance of deep learning models based on dense layers (DL1, DL1STD, DL2, DL2STD) and LSTM architectures (LSTM1, LSTM1STD, LSTM2, LSTM2STD), trained on datasets of varying sizes (n = 5, 10, 15, 20) and evaluated using mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R²). Metrics are reported separately for training, validation, and test datasets, providing a comprehensive assessment across all learning stages.

In the MAE panel, a general consistency across datasets is observed, although some models slightly overestimate errors on the test set compared to the training set. LSTM-based models, particularly LSTM1STD, achieve the lowest MAE values, especially for smaller datasets (n = 5), which indicates a better generalisation capability compared to dense-layer models.

A similar trend is observed in the RMSE results. Differences among training, validation, and test performances remain limited, suggesting good model stability. Standardised models (labelled as “STD”) consistently outperform non-standardised models by achieving lower error magnitudes.

The R² panel shows generally high performance across all models, with most configurations reaching values greater than 0.90. Slight decreases are observed for non-standardised models and for models trained on smaller datasets, particularly in the comparison between training and test results. These findings confirm that standardisation is effective in improving both predictive performance and model stability.

Overall, standardised LSTM models prove particularly effective for small datasets, combining low error rates with strong predictive performance on unseen data.

The comparison with ERA5 reanalysis data shows that the reconstructed monthly precipitation dataset achieves very high correlations across most of the Italian domain (Fig. 3). Both Spearman and Pearson coefficients display median values above 0.8, confirming the robustness of the reconstruction despite the coarser resolution of ERA5 (0.25° × 0.25°, corresponding to approximately 30–40 km) compared to the 10 km resolution of the reconstructed dataset. The spatial distribution of the correlations highlights locally lower values, particularly in some mountainous and coastal areas, where small-scale processes are not fully captured by ERA5. Nevertheless, correlations remain consistently significant across the entire domain. Importantly, all grid cells yielded p-values lower than 0.01, confirming the statistical robustness of the results.

The boxplots (top) show the distribution of correlation coefficients across all grid cells at 10 km resolution, using both Spearman (left) and Pearson (right) metrics. The orange line indicates the median value, and the green triangle indicates the average. The maps (bottom) display the spatial distribution of the correlation values for Spearman (left) and Pearson (right), highlighting generally high and spatially consistent agreement across most of Italy, with local variations in mountainous and coastal areas. All recorded points have a significant statistic with a p-value < 0.01. Basemap: OpenStreetMap contributors.

The Fig. 4 shows the practical application of these models to reconstruct historical cumulative precipitation series at six representative locations across Italy. The curves represent the median annual precipitation trends, while the 90% confidence intervals quantify the uncertainty associated with the ensemble of models.

The width of the confidence intervals is substantially smaller than the natural interannual variability of the precipitation signal. This aspect is particularly evident when comparing the width of the confidence intervals with the amplitude of the 1-year moving average fluctuations. While the climate signal displays significant interannual variability, the modelling uncertainty remains small and stable throughout the period. Therefore, the uncertainty associated with the reconstruction is relatively modest and does not compromise the correct interpretation of historical series evolution (Fig. 4).

The modelling quality highlighted by the MAE, RMSE, and R² metrics is further confirmed by the ability of the models to reconstruct consistent and reliable historical series, with uncertainties that are minor compared to the natural variability of the precipitation data.

A more detailed assessment of model performance across the geospatial domain, including additional maps and correlation analyses, is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Combined circulation patterns

The analysis of precipitation anomalies associated with different phase combinations of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and other major atmospheric circulation indices (AMO, EA, MOI, WeMO) suggests that NAO alone may not fully account for precipitation variability over Italy (Figs. 5 and 6). Although the NAO plays an important role on the regularisation of the precipitation in Italy, but its effect is strongly modulated by interactions with the other indices.

In particular, the impact of the NAO is amplified or even reversed depending on the phase of Mediterranean-related indices such as MOI and WeMO. When a positive NAO phase is combined with a negative MOI phase or a positive WeMO phase, significant positive precipitation anomalies are observed across much of the country (Fig. 5) and the statistical assessment confirms that these results are statistically significant over wide areas (Fig. 6). This indicates that a positive NAO does not necessarily correspond to drier conditions. The behaviour of the WeMO is especially distinctive: during positive WeMO phases, precipitation tends to increase, especially over the Apennine areas, while during negative WeMO phases, a reduction is generally observed along the Ionian and eastern coasts. This pattern contrasts with that of MOI, EA, and AMO, for which negative phases are typically associated with increased precipitation, although the significance analysis (Fig. 6) highlights that when both indices share the same phase the anomalies are generally not significant across Italy, whereas opposite-phase combinations yield statistically robust signals.

The contribution of AMO to precipitation variability over Italy appears relatively minor, although a partial similarity with the EA pattern is observed. Specifically, during negative AMO and EA phases, enhanced precipitation is recorded over southern Adriatic and Ionian areas, whereas positive phases tend to correspond to more widespread reductions. However, as shown in Fig. 6, only some of these anomalies reach statistical significance, underlining the need for caution when interpreting weak signals.

A more detailed analysis of the NAO − EA+ and NAO + EA− combinations reveals a marked longitudinal differentiation in the distribution of precipitation across Italy. Under NAO − EA+ conditions, positive anomalies prevail along the Adriatic coast, while reductions are observed over the Tyrrhenian regions. Conversely, under NAO + EA− conditions, precipitation increases mainly along the Tyrrhenian side, while the Adriatic sector experiences drier conditions. This longitudinal division is largely determined by the presence of the Apennine Mountain range, which acts as a natural barrier, modulating the distribution of moist air masses between the two sides of the peninsula. Atmospheric configurations favouring north and northwestern westerly flows tend to enhance precipitation on the Tyrrhenian side, whereas easterly or southeasterly flows more effectively favour precipitation development along the Adriatic coast, and the significance analysis (Fig. 6) confirms that these longitudinal contrasts are statistically robust.

Additional noteworthy evidence emerges when examining the Ionian area and the eastern sector of Sardinia. In these regions, positive precipitation anomalies are recorded even during NAO+ and WeMO− phases, which elsewhere in Italy are generally associated with precipitation deficits. This behaviour can be attributed to the activation of peripheral cyclogenesis systems developing between North Africa (Atlas Mountains region) and the Middle East. Such systems favour the advection of moist air masses towards the southern Italy, including parts of southern and eastern Sicily, Ionian and eastern Sardinian, leading to localised precipitation increases despite broader dry conditions over the rest of the peninsula.

Overall, these results demonstrate that precipitation variability over Italy cannot be attributed to a single large-scale driver but emerges from the interplay between multiple circulation modes whose influence is further modulated by regional orography. This complexity explains the spatial heterogeneity and the limited statistical significance observed in some areas, highlighting the need for multi-index approaches to properly capture Mediterranean rainfall dynamics.

Back-trajectory analysis

The analysis of air mass back-trajectories (Figs. 7 and 8) obtained using the HYSPLIT model, allows the identification of the main moisture uptake regions that contribute to precipitation across the Italian Peninsula and its major islands. The results reveal a clear spatial variation in the sources of atmospheric moisture, closely linked to geographic position and regional orographic features.

a Point 1; b Point 3; c Point 13; d Point 8. The maps show the spatial distribution of average moisture uptake along the back-trajectories associated with each site. e reports the map of the arrival locations of the trajectories considered in the analysis (1–17). The colour scale indicates the mean intensity of moisture uptake, from lower values (light blue) to higher values (dark blue). Basemap: OpenStreetMap contributors.

As an illustrative example, Fig. 7 reports the average moisture uptake fields derived from back-trajectory analysis for four representative sites distributed across the Italian Peninsula. These points were selected to highlight the diversity of regional behaviours, with northern, central, southern, and insular locations showing distinct patterns of dominant source regions. The maps confirm that the relative contribution of the different basins is strongly modulated by geography and large-scale circulation, providing a useful framework before discussing the broader national-scale patterns.

In Northern Italy, the Western Mediterranean emerges as the primary source of moisture uptake source, followed in importance by the Adriatic Sea. Contributions from the North Atlantic, Central Atlantic, and eastern basins are marginal. This pattern reflects a regime dominated by south-westerly moist flows atmospheric disturbances coming from west and northwest, which collect pick most moisture vapour over the Western Mediterranean before reaching northern Italy.

In Central Italy, the Western Mediterranean constitutes the primary moisture source, particularly along the Tyrrhenian side. This pattern is largely modulated by cyclogenetic activity in the Gulf of Genoa, which interacts with atmospheric disturbances coming from northwest and trigger local cyclogenesis and frequently initiates baroclinic systems responsible for enhanced westerly moisture advection toward the western flanks of the Apennines. East of the ridge, however, the Adriatic Sea and Ionian Seas progressively assume a more prominent role as moisture contributors. This spatial shift underscores the function of the Apennine range as a significant orographic divide, delineating two distinct synoptic regimes: Mediterranean Atlantic westerlies, strongly influenced by mediterranean Genoa cyclogenesis, to the west, and easterly to southeasterly flows associated with Adriatic and Ionian sources to the east.

Moving towards Southern Italy, there is a progressive increase in the contribution from the Ionian Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean, with a corresponding decrease in the influence of the Western Mediterranean49. In these areas, moist air masses more frequently originate from southern and eastern basins, especially during synoptic conditions associated with cyclogenesis between North Africa and the Middle East.

A particular case is represented by Sardinia, where a significant contribution from the North Atlantic is observed alongside that of the Western Mediterranean. This pattern reflects the geographical position of the island, which is more directly exposed to westerly and north-westerly airflows air masses compared to the rest of Italy.

Overall, the results highlight how that the spatial distribution of moisture uptake sources is strongly controlled by both the origin and trajectories of main atmospheric disturbance systems, as well as by the orographic characteristics of the regions and their relative position along major vapour transport pathways. Atmospheric trajectories and their associated moisture uptake source regions contribute to shaping the regional variability in moisture supply across the Italian Peninsula and its major islands.

Discussion

The results of this work contribute to a better understanding of the complex mechanisms that influence precipitation variability over Italy and the broader Mediterranean Basin. By combining historical series reconstruction through artificial intelligence models, teleconnection phase analysis, and the investigation of moisture uptake trajectories, the study offers a multifaceted perspective on the interplay between large-scale atmospheric forcings and regional hydrological behaviour.

While classical interpolation techniques are widely used, the adoption of neural network models in this work primarily responds to the need for efficiently handling and exploiting large climate databases, rather than benchmarking model performance against simpler methods. The reconstruction of precipitation time series through deep neural networks has demonstrated high reliability, with uncertainties significantly lower than the natural interannual variability. This result confirms the potential of artificial intelligence in filling gaps within fragmented historical datasets, as also suggested by recent applications in the field of historical climatology50,51.

The historical series reconstructed in this study demonstrate how the integration of advanced methodologies makes it possible to effectively manage large climate databases and extract meaningful information from them. The consistency of the dataset produced was also verified through comparison with independent reanalysis data (ERA5), using statistical correlation analyses. The results confirm the robustness of the models and their ability to reproduce climate signals consistent with those reported in the literature, even for variables characterised by high spatial and temporal variability such as precipitation. Moreover, the use of this dataset has made it possible to overcome two main limitations of reanalysis products: (i) the historical series reconstructed here are entirely based on statistical–probabilistic approaches, relying solely on observational data and not on physical models; (ii) the spatial resolution achieved is about 7–8 times higher than that of ERA5, improving from approximately 0.25° × 0.25° (about 28 × 28 km) to 10 × 10 km in the dataset developed in this work.

The analysis of atmospheric teleconnections confirms that NAO variability alone is not sufficient to explain the precipitation patterns observed over Italy, in agreement with numerous studies52,53. Our results show that the influence of the NAO is strongly modulated by interactions with other indices, particularly the EA, MOI, and WeMO.

The relatively stronger influence of the MOI compared to the WeMO can be interpreted in light of its synoptic nature and much broader spatial scale. The MOI is defined as the pressure difference between Algiers and Cairo and therefore expresses an east–west gradient that involves the entire Mediterranean Basin. Negative MOI phases have historically been associated with cyclonic conditions over the central and eastern Mediterranean or North Africa, which facilitate the advection of moist air toward Italy, particularly over the southern sector and the Adriatic coast54. In contrast, the WeMO describes a more regional pressure dipole between the Iberian Peninsula and the Gulf of Genoa, whose influence is especially evident in local dynamics such as Genoa cyclogenesis and in certain extreme precipitation events over the western Mediterranean34. This difference in spatial extent and temporal persistence provides a solid explanation for why the MOI emerges as a more robust and consistent index in modulating precipitation variability over Italy compared to the WeMO.

The MOI proves especially relevant in modulating precipitation throughout the study area, with negative phases associated with increased precipitation, especially along the western regions. The presence of a low-pressure trough over the Mediterranean is a key factor in triggering significant precipitation. Regardless of the general distribution of high and low pressures across latitudes, when a trough develops over the Mediterranean region, it is very likely to generate atmospheric instability, leading to increased precipitation. Conversely, when high pressure rises from lower latitudes over the central Mediterranean, especially if persistent, it creates stable atmospheric conditions that result in the absence of significant reduction of precipitation (Fig. 9).Furthermore, the combination of NAO − /EA+ and NAO + /EA− phases generates a marked longitudinal differentiation in precipitation anomalies, confirming the key role of the Apennine chain as an orographic barrier. When a negative NAO phase is combined with a positive EA phase, the upper-level flow tends to shift southward, promoting moisture advection from the southwest to the northeast (Fig. 9). In this case, the jet stream tends to adopt a more zonal or southeastward-tilted orientation, intensifying moisture transport over the western regions while suppressing precipitation along the Adriatic sector (Fig. 9). Similarly, when a positive NAO phase is combined with a negative EA phase, the upper-level westerly flow tends to shift southward, producing comparable effects that enhance precipitation along Adriatic coast55,56 and in southern Italy. The Italian orography, particularly the presence of the Apennines, further accentuates this longitudinal separation.

The grey-to-black lines represent sea level pressure isobars, with lighter shades indicating lower pressure and darker shades indicating higher pressure. Blue dots indicate areas of increased precipitation, while red dots indicate reduced rainfall, as shown in the Mean Sea Level Pressure (SLP). Sea-level pressure isobars are derived from ERA5 Monthly data (ECMWF, via Google Earth Engine: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_ERA5_MONTHLY). Basemap: OpenStreetMap contributors.

The behaviour of the WeMO also reveals similar dynamics, highlighting the need to consider regional teleconnections in climate analyses of the Mediterranean33,57. Our study confirms that positive phases of the WeMO are generally associated with increased precipitation in Italy, while negative phases correlate with a reduction (as observed also by ref. 35), underscoring the importance of this index in modulating the hydrological response of the Mediterranean area.

Our results suggest that the East Atlantic (EA) pattern exerts a stronger modulation of precipitation over Italy than the WeMO, particularly in combination with NAO phases. The EA is not only the second dominant mode of North Atlantic variability but, in some historical periods such as the early twentieth century, it even emerged as the leading mode, surpassing the NAO in its influence on European precipitation58. The physical mechanisms underlying this influence are linked to the EA’s control over the position and intensity of the North Atlantic jet stream and the associated storm tracks, which explain up to one quarter of the interannual variability of European winter precipitation59. Long-term reconstructions further show that the EA interacts non-linearly with the NAO, with opposite-phase combinations producing the largest shifts in jet latitude and the most robust precipitation anomalies across the western and central Mediterranean60. Taken together, these findings reinforce the importance of considering the EA pattern, alongside NAO and MOI, as a key driver of hydro-climatic variability over Italy, while the WeMO remains more confined to regional dynamics.

Recent studies suggest that the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) may become more frequently positive in the future61,62, with direct implications for hydro-climatic regimes in the Mediterranean. Our analysis already shows that NAO+ phases are generally associated with reduced precipitation across much of Italy, particularly in central and southern regions, suggesting that a greater frequency of such conditions could intensify drying trends, especially if combined with a weakening of Mediterranean cyclogenetic areas. This dynamic is further reinforced by rising Mediterranean Sea surface temperatures (SST), which according to the literature weaken both the Icelandic Low and the Genoa Gulf Low63, resulting in reduced Mediterranean cyclogenesis64. The progressive intensification of negative WeMO phases can also be interpreted as a manifestation of this weakening, linked to the expansion of the Azores High and a background state more consistent with NAO+ conditions58. Taken together, these mechanisms are consistent with projections for Italy that indicate an increase in winter precipitation in the North but widespread reductions in other seasons, as highlighted by the most recent statistical downscaling experiments of CMIP6 simulations65. Moreover, while total precipitation is expected to decrease, rising Mediterranean SSTs promote greater atmospheric instability, fostering more frequent and intense extreme rainfall events66,67,68,69. These results reinforce the hypothesis that climate warming will intensify the “hydrological paradox” already observed in the Mediterranean: an overall reduction in annual totals accompanied by an increase in extreme events, placing our findings within a coherent trajectory from past to future.

The analysis of back-trajectories provides an additional interpretative layer, identifying the main moisture sources responsible for precipitation in Italy. Results show that the Western Mediterranean dominates in Central-Northern Italy, especially in the northwestern regions (e.g., Liguria, Tuscany, Piedmont), while the contribution from the Ionian Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean increases progressively toward the South and East, in agreement with previous observations70,71. The North Atlantic, despite being the origin of many frontal systems reaching Italy72,73 contributes only marginally to the moisture associated with precipitation, and primarily in the western regions of the peninsula. These findings suggest that moisture sources largely follow the prevailing large-scale synoptic patterns typically associated with precipitation in different parts of Italy. Indeed, periods marked by enhanced subtropical or Eastern Mediterranean cyclogenesis have been shown to increase moisture contributions from basins such as the Ionian and Aegean Seas74. By contrast, the strong role of the Western Mediterranean reflects the influence of teleconnections such as the NAO and the MOI, which modulate both the frequency and intensity of cyclonic activity over this basin75. Overall, these results highlight that air mass trajectories and associated uptake points are highly sensitive to both the prevailing synoptic configuration, since pressure gradients, cyclonic systems, and associated temperature–humidity contrasts strongly modulate the pathways of air masses and the intensity of evaporation over different basins.

Conclusion

This study combined innovative methodologies, including the reconstruction of historical precipitation series using deep learning models, the analysis of atmospheric teleconnections, and the study of moisture uptake trajectories, to explore precipitation variability in Italy and the complex interplay of climate forcings at both regional and hemispheric scales.

The main findings can be summarised as follows:

-

Combined influence of teleconnections: Precipitation variability in Italy cannot be explained by analyzing individual indices such as the NAO alone. Instead, it requires a combined evaluation of multiple atmospheric signals (EA, MOI, WeMO), also modulated by the presence of the Apennine orography.

-

Dipolar precipitation configurations over Italy: Precipitation patterns can diverge substantially when the NAO is in an opposite phase compared with other circulation modes such as EA or WeMO. These non-coherent configurations alter the trajectory and intensity of synoptic disturbances entering the Mediterranean, generating dipolar responses through the interaction between Atlantic frontal systems and pressure anomalies developing over the central or eastern Mediterranean.

-

Distribution of moisture sources: Moisture uptake analysis reveals a clear latitudinal gradient, with the Western Mediterranean dominating in the North, and a progressively increasing contribution from the Ionian Sea and Eastern Mediterranean toward the South and East.

Although Mediterranean dynamics may play a predominant role, past climate variability is often interpreted primarily in relation to Atlantic circulation patterns. This approach can lead to a simplified or incomplete understanding of the paleoclimate system, which nevertheless forms the basis for developing future climate projections in the context of ongoing climate change. These results suggest that Mediterranean regional dynamics may have played a significant role during certain historical periods, complicating the interpretation of signals recorded in paleoclimate proxies traditionally associated with North Atlantic circulation.

Therefore, future studies should further investigate this hypothesis by integrating the contribution of Mediterranean regional climate signals. The Italian, and more broadly, Mediterranean, hydro-climatic response appears to be extremely sensitive to the dynamic interplay between global forcings and local processes. This complexity highlights the need for multidisciplinary and multiscale approaches to understand and predict future developments in the Mediterranean climate. In this framework, the reconstruction and analysis of atmospheric indices specifically tailored to the Mediterranean basin, alongside traditional indices like the NAO, and the direct tracking of Mediterranean cyclones combined with observational precipitation datasets, could be key to improving our understanding of past climate dynamics and the climate signals recorded in proxies.

Materials and methods

Reconstruction of rainfall time series

The historical time series used in this work originate from a census promoted by the Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA), within the project “Sistema Nazionale per l’Elaborazione e Diffusione di Dati Climatici” (SCIA; https://scia.isprambiente.it/). This portal gathers climate data collected over decades by various institutions dedicated to this activity25.

We downloaded monthly rainfall data from this portal, totalling 11,189 stations and 4,112,999 records from 1860 to 2023. From a preliminary analysis, most stations became active after 1950 (11,024), thus, our subsequent analyses focused on the period from 1950 to 2020.

The data were used to build deep learning models capable of predicting the monthly rainfall value recorded at a station using known values from nearby stations. A total of 16 models were developed, differing in the number of neighbouring stations used, the application of data standardisation, and the neural network architecture.

Each record in the database was used to construct the input matrix for the neural networks, and each temporal record was associated with the precipitation value of the corresponding month from n neighbouring stations, where n assumed values of 5, 10, 15, and 20.

Standardising the input data within the range 0–1 can help neural networks minimise weight values by reducing data dimensionality. Input features with varying dimensions may hinder optimisation functions from achieving a suitable fit (citation).

To tackle the regression task on the available data, two different deep neural network architectures were developed and tested: a fully connected feedforward network (FCNN) and a recurrent network based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) with an encoder-decoder structure.

Both models were implemented using the Keras Sequential API and optimised based on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), chosen for its robustness to outliers.

The fully connected network consists of four hidden layers with decreasing sizes: 4096, 1024, 256, and 64 neurons, respectively, all with ReLU activation functions. Each layer includes L2 regularisation (λ = 0.01) to penalise excessive weights and enhance generalisation. Batch normalisation and a Dropout layer with a dropout rate of 30% follow each layer to prevent overfitting.

To exploit the temporal and sequential dependencies in the multivariate data, a recurrent neural network was implemented using LSTM units (CIT). The architecture follows an encoder-decoder scheme: the encoder comprises two LSTM layers with 64 and 32 units, respectively. The first returns the entire temporal sequence, while the second compresses the information into a final state. This state is then replicated through time using a RepeatVector and fed into the decoder, which consists of two LSTM layers (32 and 64 units) configured to return a sequence.

The decoder output is managed by a TimeDistributed layer that applies a Dense layer independently to each time step, followed by a Flatten layer and two fully connected Dense layers, with the last producing a single continuous prediction.

Both architectures were trained using the Adam optimiser with an initial learning rate of 0.001. To monitor training and prevent overfitting, the following callbacks were used:

-

EarlyStopping: Monitors the validation loss and stops training if no improvement is observed after a defined number of epochs. The model weights are automatically restored to the best configuration.

-

ModelCheckpoint: Saves the model weights corresponding to the best validation performance to preserve the most effective model configuration during training.

The input data were split into three subsets: training (approximately 60%), validation (20%), and test (20%). This division is essential to ensure the fairness and reliability of the model evaluation process. The training set is used to learn the network parameters, the validation set is used to monitor performance during training and prevent overfitting, while the test set provides an independent final assessment of the model’s predictive capabilities. To properly assess model generalisation, we applied both spatially blocked (leave-one-region-out) and temporally blocked (leave-years-out) cross-validation. The detailed procedure and results are reported in the Supplementary Material.

The reconstructed precipitation dataset was validated against ERA5 reanalysis data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://climate.copernicus.eu/climate-reanalysis), which provides a widely used and well-established reference for climate and hydrological studies. To assess the consistency between the two datasets, we calculated both Spearman76 and Pearson77 correlation coefficients at a monthly scale over the common period of analysis. While Pearson’s correlation measures the strength of the linear relationship, Spearman’s correlation also accounts for monotonic but non-linear associations, offering a more comprehensive evaluation of agreement. The correlations were computed at each 10 km grid cell of the reconstructed dataset by comparing the corresponding spatially matched ERA5 time series.

After training, the models were applied over a grid of regularly spaced points (10 km resolution), thus reconstructing a continuous dataset from 1950 to 2020. The model results are available for download via the AI Climate web application (https://lca.dst.unipi.it/AIClimate/), developed as part of this work.

Atmospheric teleconnection analysis

In this study, precipitation is compared with several atmospheric indices: the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO; https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/AMO/) which represents long-term variability in sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic78; North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO; https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/hurrell-north-atlantic-oscillation-nao-index-pc-based), which describes fluctuations in atmospheric pressure differences between Iceland and the Azores and influences the climate of Europe26; the East Atlantic (EA) pattern, a similar but eastward-shifted mode that influences a broader area including southern and central Europe60,79; the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO; https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/), based on the pressure gradient between the Gulf of Cádiz and the Gulf of Genoa, which affects precipitation distribution in the western Mediterranean33; and the Mediterranean Oscillation Index (MOI; https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/), which measures the pressure difference between Algiers and Cairo and is useful for understanding climate variability in the Mediterranean area80.

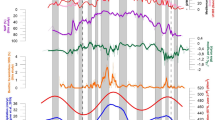

Atmospheric teleconnection indices exhibit marked variability on interannual, decadal, and multidecadal time scales, as shown by their respective monthly historical time series (Fig. 10). These indices capture the influence of large-scale climatic patterns on atmospheric and marine oceanic conditions, such as sea surface temperatures and solar-related activity variability. In this sense, they serve as indicators of the modulation exerted by broader dynamical processes rather than direct drivers. In this context, analysing the combined effects of large-scale synoptic atmospheric configurations is essential for understanding their impact on the spatial distribution of precipitation (Fig. 10).

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), East Atlantic (EA), Mediterranean Oscillation Index (MOI), North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO), Genoa Gulf Sea Surface Temperature (GGSST), Mediterranean Sea Surface Temperature (MSST) and North Atlantic Sea Surface Temperature (NASST). The SST data and trends were computed using ERSST v5 data (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html).

In particular, the AMO shows a cyclic pattern, with prolonged negative phases from the 1960s to the 1990s followed by a positive phase over the past three decades (Fig. 10). The EA index shows a more linear upward trend, while the MOI and the WeMO have recently strengthened, consistent with an intensification of regional pressure gradients. The NAO, although characterised by higher variability, has shifted from a predominantly negative phase (1960s–1980s) to a positive one since the 1990s.

In addition to these atmospheric signals, positive trends in sea surface temperatures are observed in the North Atlantic (NASST), in the Mediterranean (MSST), and in Genoa Gulf (GGSST), one of the main cyclogenetic centres of this area64, indicating a context of progressive warming in the ocean-atmosphere system (Fig. 10).

Given this underlying variability, it is essential to examine the combined effects of different teleconnection patterns on precipitation trends patterns. To this end, all binary combinations between NAO and each of the other indices (AMO, EA, MOI, WeMO) were constructed, considering the positive and negative phases as defined by the sign of the monthly value.

For each combination (e.g., NAO + /AMO − ), the months in which both indices were simultaneously in the indicated phase were selected. The average precipitation recorded during those months was compared to the long-term climatology at each grid point over Italy, resulting in percentage anomalies:

where \({P}_{ph{ase}}\) represents the average precipitation during periods in which the specific phase combination occurs, and \({P}_{{clim}}\) is the climatological mean over the entire analysis period (1950–2020).

To assess the statistical significance of the precipitation anomalies associated with the different combinations of large-scale and regional circulation indices, we implemented a non-parametric bootstrapping approach. For each configuration (e.g., NAO+ | AMO–), we first computed the observed precipitation anomaly as the percentage deviation of the mean precipitation with respect to the climatological mean. Then, to evaluate whether this anomaly could arise by chance, we generated an empirical distribution by resampling with replacement from the full dataset, drawing the same number of years as in the target configuration. The anomaly was recalculated for each bootstrap sample, and this procedure was repeated 5000 times to obtain a robust reference distribution. The p-value was then estimated as the proportion of bootstrap replicates yielding an anomaly of equal or greater magnitude than the observed one. Grid cells with p-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Analysis and moisture uptake diagnostic

The back-trajectory analysis was carried out using the HYSPLIT software47,48, supported by a Python-based Application Programming Interface (API)s developed in Python81. The operational framework presented in ref. 42 was adopted, where further methodological details are provided. The analysis model was performed run at 17 points sites distributed across the entire study area, selected to be representative of climatic variability at the national scale. For each point, using the SCIA database, rainy days with precipitation above the median were selected to include only events with hydrologically significant rainfall. The number of events simulated for each point ranged between 786 and 1212, with a median value of 964 events, representing a statistically significant sample for the study of back-trajectories.

1 × 1° grids from the Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS) 1 × 1° grids, provided by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), were used as meteorological input data. For each rainfall event, 5-day (120-h) back -trajectories were calculated using the geographic coordinates of the 17 analysis points-sites as starting locations.

The model runtime of 5 days backward was chosen to keep choice of a 5-day time horizon aimed to balance accuracy and representativeness, while keeping trajectory uncertainty within acceptable limits. This value is also below the average atmospheric water vapour residence time of 10 days (Numaguti 1999)82.

To trace the air mass responsible for precipitation, the model’s starting elevation was set at 1500 metres above ground level (a.g.l.), due to the lack of direct data on cloud base height (CBH) in the region and time period. This choice is justified by the fact that most atmospheric moisture is concentrated in the first 2000 metres a.g.l.83,84.

Back-trajectory numerical error was estimated by generating reversed trajectories, initialised at the endpoint of the original trajectories and propagated in the opposite direction. Only trajectories with a relative integration error below 5% were selected for further analysis. The error was calculated as the distance between the starting point of the forward backward trajectory and the endpoint of the reversed trajectory, relative to the total path length.

An additional model was applied to identify moisture uptake points along the back-trajectories, following the method proposed by ref. 85 and later adopted by other authors41,42,70,86,87. This approach is based on analysing changes in specific humidity (q, g/kg) at 6-h intervals along the air parcel’s path. Uptake points were identified where the change Δq between time “t” and “t − 6 h” was ≥ 0.2 g/kg and occurred below the planetary boundary layer (PBL). Points above the PBL were excluded, as they are not directly attributable to surface moisture fluxes.

To assess the influence of the identify the major moisture uptake regions on the origin of the air masses associated with precipitation in the selected sites, the area was divided into seven regions (Fig. S6), following a common approach in the scientific literature41,70,86,87: North Atlantic, Central Atlantic, Western Mediterranean, Adriatic Sea, Ionian Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, and Black Sea. In our analysis of moisture uptake, we focused exclusively on oceanic sources, which on average account for about 80% of total contributions42.

Finally, the percentage contribution of moisture uptake (PMU) from each region was estimated as the ratio between the sum of all Δq values detected within that region and the total sum of Δq values across all source regions, as described in ref. 42.

Data availability

All model-derived datasets used in this study are openly available and can be downloaded at the following link: https://lca.dst.unipi.it/AIClimate/. The repository provides full access to the processed outputs, including atmospheric and hydro-climatic variables, as well as the scripts used to generate the derived products.

References

Giorgi, F. Climate change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L08707 (2006).

Lazoglou, G. et al. Identification of climate change hotspots in the Mediterranean. Sci. Rep. 14, 29817 (2024).

Longobardi, A. & Villani, P. Trend analysis of annual and seasonal rainfall time series in the Mediterranean area. Int. J. Climatol. 30, 1538–1546 (2010).

Caporali, E., Lompi, M., Pacetti, T., Chiarello, V. & Fatichi, S. A review of studies on observed precipitation trends in Italy. Int. J. Climatol. 41, E1–E25 (2021).

Deitch, M. J., Sapundjieff, M. J. & Feirer, S. T. Characterizing precipitation variability and trends in the World’s Mediterranean-Climate Areas. Water 9, 259 (2017).

Gonzalez-Hidalgo, J., Blanco, V., Beguería, S. & Peña-Angulo, D. Seasonal precipitation changes in the western Mediterranean basin the case of Spanish mainland, 1916-2015. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 1800–1815 (2024).

Börgel, F., Frauen, C., Neumann, T. & Meier, H. E. M. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation controls the impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on North European climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104025 (2020).

Mikhailova, N. & Yurovsky, A. The East Atlantic Oscillation: mechanism and impact on the European climate in winter. Phys. Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.22449/1573-160X-2016-4-25-33 (2016).

Reale, M. et al. Future projections of Mediterranean cyclone characteristics using the Med-CORDEX ensemble of coupled regional climate system models. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2501–2524 (2022).

Chericoni, M., Fosser, G., Flaounas, E., Gaetani, M. & Anav, A. Unravelling drivers of the future Mediterranean precipitation paradox during cyclones. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 260 (2025).

Brönnimann, S. et al. Influence of warming and atmospheric circulation changes on multidecadal European flood variability. Climate 18, 919–933 (2022).

Luppichini, M., Lazzarotti, M. & Bini, M. Climate change as main driver of centennial decline in river sediment transport across the Mediterranean region. J. Hydrol. 636, 131266 (2024).

Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Quantifying the relevance of cyclones for precipitation extremes. J. Clim. 25, 6770–6780 (2012).

Zappa, G., Shaffrey, L. C., Hodges, K. I., Sansom, P. G. & Stephenson, D. B. A multimodel assessment of future projections of North Atlantic and European Extratropical cyclones in the CMIP5 climate models. J. Clim. 26, 5846–5862 (2013).

Kushabaha, A. et al. ARCHIMEDE—An Innovative Web-GIS Platform for the Study of Medicanes. Remote Sens. 16, 2552 (2024).

Gudmundsson, L., Seneviratne, S. I. & Zhang, X. Anthropogenic climate change detected in European renewable freshwater resources. Nat. Clim. Chang 7, 813–816 (2017).

Jasechko, S. et al. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 625, 715–721 (2024).

Wu, W.-Y. et al. Divergent effects of climate change on future groundwater availability in key mid-latitude aquifers. Nat. Commun. 11, 3710 (2020).

Berthou, S. et al. Influence of submonthly air–sea coupling on heavy precipitation events in the Western Mediterranean basin. Q. J. R. Meteoro. Soc. 142, 453–471 (2016).

Flaounas, E. et al. Assessment of an ensemble of ocean–atmosphere coupled and uncoupled regional climate models to reproduce the climatology of Mediterranean cyclones. Clim. Dyn. 51, 1023–1040 (2018).

Chericoni, M., Fosser, G., Flaounas, E., Sannino, G. & Anav, A. Extreme Mediterranean cyclones and associated variables in an atmosphere-only vs. an ocean-coupled regional model. Weather Clim. Dyn. 6, 627–643 (2025).

Famiglietti, J. S. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Chang 4, 945–948 (2014).

Vicente-Serrano, S. et al. High temporal variability not trend dominates Mediterranean precipitation. Nature 639, 658–666 (2025).

Luterbacher, J. et al. The importance and scientific value of long weather and climate records; examples of historical marine data efforts across the globe. Climate 12, 39 (2024).

Morbidelli, R. et al. A reassessment of the history of the temporal resolution of rainfall data at the global scale. J. Hydrol. 654, 132841 (2025).

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic oscillation: regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269, 676 LP – 679–676 LP – 679 (1995).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M. & López-Moreno, J. I. Nonstationary influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on European precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D20120 (2008).

Luppichini, M., Barsanti, M., Giannecchini, R. & Bini, M. Statistical relationships between large-scale circulation patterns and local-scale effects: NAO and rainfall regime in a key area of the Mediterranean basin. Atmos. Res. 248, 105270 (2021).

Vergni, L. & Chiaudani, A. Relationship between the NAO Index and Some Indices of Extreme Precipitation in the Abruzzo Region. http://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/guidance/hurrell-north- (2015).

Brandimarte, L. et al. Relation between the North-Atlantic oscillation and hydroclimatic conditions in Mediterranean areas. Water Resour. Manag. 25, 1269–1279 (2011).

Polovodova Asteman,I.,Filipsson, H. L. & Nordberg,K. Tracing winter temperatures over the last two millennia using a north-east Atlantic coastal record.Climate 14,1097–1118 (2018).

Unit, C. R. Mediterranean Oscillation Indices (MOI). Preprint at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/ (2021).

Martin-Vide, J. & Lopez-Bustins, J.-A. The Western Mediterranean Oscillation and rainfall in the Iberian Peninsula. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 1455–1475 (2006).

Lopez-Bustins, J. A., Arbiol-Roca, L., Martin-Vide, J., Barrera-Escoda, A. & Prohom, M. Intra-annual variability of the Western Mediterranean Oscillation (WeMO) and occurrence of extreme torrential precipitation in Catalonia (NE Iberia). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 2483–2501 (2020).

Luppichini, M., Bini, M., Barsanti, M., Giannecchini, R. & Zanchetta, G. Seasonal rainfall trends of a key Mediterranean area in relation to large-scale atmospheric circulation: how does current global change affect the rainfall regime?. J. Hydrol. 612, 128233 (2022).

Ferrari, E., Caloiero, T. & Coscarelli, R. Influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on winter rainfall in Calabria (southern Italy). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 114, 479–494 (2013).

Zanchetta, G. et al. Insight into summer drought in southern Italy: palaeohydrological evolution of Lake Pergusa (Sicily) in the last 6700 years. J. Quat. Sci. 37, 1280–1293 (2022).

Zanchetta, G. et al. Beyond one-way determinism: San Frediano’s miracle and climate change in Central and Northern Italy in late antiquity. Clim. Change 165, 25 (2021).

Ferrari, E. & Terranova, O. Non-parametric detection of trends and change point years in monthly and annual rainfalls. In Proc. 1st Italian-Russian Workshop New Trends in Hydrology. Vol. 2823, 177–188 (CNR Publ, 2004).

Caloiero, T., Coscarelli, R., Ferrari, E. & Mancini, M. Precipitation change in Southern Italy linked to global scale oscillation indexes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1683–1694 (2011).

Natali, S. et al. Moisture sources and climatic effects controlling precipitation stable isotope composition in a western Mediterranean island (Pianosa, Italy). Atmos. Res. 294, 106987 (2023).

Natali, S. et al. Assessing moisture origin as a potential driver of event-based precipitation isotope variability in a Western Mediterranean catchment (Apuan Alps, Italy). Clim. Dyn. 63, 159 (2025).

Frot, E., van Wesemael, B., Vandenschrick, G., Souchez, R. & Benet, A. S. Origin and type of rainfall for recharge of a karstic aquifer in the western Mediterranean: a case study from the Sierra de Gador–Campo de Dalias (southeast Spain). Hydrol. Process 21, 359–368 (2007).

Gómez-Hernández, M., Drumond, A., Gimeno, L. & Garcia-Herrera, R. Variability of moisture sources in the Mediterranean region during the period 1980–2000. Water Resour. Res. 49, 6781–6794 (2013).

Batibeniz, F. et al. Identification of major moisture sources across the Mediterranean Basin. Clim. Dyn. 54, 1–19 (2020).

Drumond, A., Nieto, R., Hernandez, E. & Gimeno, L. A Lagrangian analysis of the variation in moisture sources related to drier and wetter conditions in regions around the Mediterranean Basin. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 2307–2320 (2011).

Stein, A. F. et al. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015).

Rolph, G., Stein, A. & Stunder, B. Real-time environmental applications and display system: ready. Environ. Model. Softw. 95, 210–228 (2017).

Buzzi, A., Davolio, S. & Fantini, M. Cyclogenesis in the lee of the Alps: a review of theories. Bull. Atmos. Sci. Technol. 1, 433–457 (2020).

Pham, B. T. et al. Development of advanced artificial intelligence models for daily rainfall prediction. Atmos. Res. 237, 104845 (2020).

Plésiat, É, Dunn, R. J. H., Donat, M. G. & Kadow, C. Artificial intelligence reveals past climate extremes by reconstructing historical records. Nat. Commun. 15, 9191 (2024).

Brunetti, M., Maugeri, M. & Nanni, T. Trends of the daily intensity of precipitation in Italy and teleconnections(*). IL NUOVO CIMENTO https://doi.org/10.1393/ncc/i2005-10227-9 (2006).

Vergni, L., Di Lena, B. & Chiaudani, A. Statistical characterisation of winter precipitation in the Abruzzo region (Italy) in relation to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Atmos. Res. 178–179, 279–290 (2016).

Redolat, D., Monjo, R., Lopez-Bustins, J. A. & Martin-Vide, J. Upper-Level Mediterranean Oscillation index and seasonal variability of rainfall and temperature. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 135, 1059–1077 (2019).

Portal, A., Raveh-Rubin, S., Catto, J. L., Givon, Y. & Martius, O. Linking compound weather extremes to Mediterranean cyclones, fronts, and airstreams. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 1043–1060 (2024).

Flaounas, E. et al. Cyclone contribution to the Mediterranean Sea water budget. Clim. Dyn. 46, 913–927 (2016).

Martinez-Artigas, J., Lemus-Canovas, M. & Lopez-Bustins, J. A. Precipitation in peninsular Spain: Influence of teleconnection indices and spatial regionalisation. Int. J. Climatol. 41, E1320–E1335 (2021).

Halifa-Marín, A. et al. Beyond the NAO: the East Atlantic Pattern’s Role in Early 20th-Century Meteorological Droughts in Western Europe. Int. J. Climat. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.70045 (2025).

Mikhailova, N. V. & Yurovsky, A. V. The East Atlantic Oscillation: mechanism and Impact on the European Climate in Winter. Morskoy gidrofizicheskiy zhurnal https://doi.org/10.22449/0233-7584-2016-4-27-37 (2016).

Mellado-Cano, J., Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Trigo, R. M. & Hernández, A. Examining the north atlantic oscillation, east atlantic pattern, and jet variability since 1685. J. Clim. 32, 6285–6298 (2019).

Visbeck, M. H., Hurrell, J. W., Polvani, L. & Cullen, H. M. The North Atlantic Oscillation: Past, present, and future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12876 (2001).

Mitevski, I., Lee, S. H., Vecchi, G., Orbe, C. & Polvani, L. M. More positive and less variable North Atlantic Oscillation at high CO2 forcing. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 171 (2025).

Frankignoul, C., Friederichs, P. & Kestenare, E. Influence of Atlantic SST anomalies on the atmospheric circulation in the Atlantic-European sector. Ann. Geophys. 46, https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-3390 (2003).

Trigo, I. F., Bigg, G. R. & Davies, T. D. Climatology of cyclogenesis mechanisms in the Mediterranean. Monthly Weather Rev. 130 549–569 (2002).

Fedele, G., Reder, A. & Mercogliano, P. Statistical downscaling over Italy using EQM: CMIP6 Climate Projections for the 1985–2100 Period. Sci. Data 12, 910 (2025).

Gentilucci, M., Barbieri, M., Lee, H. S. & Zardi, D. Analysis of rainfall trends and extreme precipitation in the middle Adriatic side, Marche Region (Central Italy). Water 11, 1948 (2019).

Pumo, D. & Noto, L. V. Exploring the linkage between dew point temperature and precipitation extremes: a multi-time-scale analysis on a semi-arid Mediterranean region. Atmos. Res. 254, 105508 (2021).

Iannuccilli, M. et al. Extreme precipitation events and their relationships with circulation types in Italy. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 4769–4793 (2021).

Noto, L., Cipolla, G., Pumo, D. & Francipane, A. Climate change in the Mediterranean Basin (Part II): a review of challenges and uncertainties in climate change modeling and impact analyses. Water Resour. Manag. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-023-03444-w (2023).

Krklec, K., Domínguez-Villar, D. & Lojen, S. The impact of moisture sources on the oxygen isotope composition of precipitation at a continental site in central Europe. J. Hydrol. 561, 810–821 (2018).

Baldini, L. M., McDermott, F., Baldini, J. U. L., Fischer, M. J. & Möllhoff, M. An investigation of the controls on Irish precipitation δ18O values on monthly and event timescales. Clim. Dyn. 35, 977–993 (2010).

Lionello, P. et al. The Mediterranean climate: an overview of the main characteristics and issues. Dev. Earth Environ. Sci. 4, 1–26 (2006).

Reale, M. & Lionello, P. Synoptic climatology of winter intense precipitation events along the Mediterranean coasts. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 1707–1722 (2013).

Hochman, A. et al. The dynamics of cyclones in the twenty-first century: the Eastern Mediterranean as an example. Clim. Dyn. 54, 561–574 (2020).

Nissen, K. et al. Cyclones causing wind storms in the Mediterranean: characteristics, trends and links to large-scale patterns. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 1379–1391 (2010).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 15, 72–101 (1904).

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient. in Encyclopedia of Public Health (ed. Kirch, W.) 1090–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_2569 (Springer Netherlands, 2008).

Schlesinger, M. E. & Ramankutty, N. An oscillation in the global climate system of period 65–70 years. Nature 367, 723–726 (1994).

Center, C. P. East Atlantic. Preprint at https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/teledoc/ea.shtml (2021).

Palutikof, J. P., Conte, M., Giuffrida, A. & Mazzarella, A. Mediterranean climate variability and predictability. in Mediterranean Climate Variability (eds. Lionello, P., Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. & Boscolo, R.) 125–149 (Elsevier, 1996).

Warner, M. S. C. Introduction to PySPLIT: a Python Toolkit for NOAA ARL’s HYSPLIT Model. Comput Sci. Eng. 20, 47–62 (2018).

Numaguti, A. Origin and recycling processes of precipitating water over the Eurasian continent: Experiments using an atmospheric general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 1957–1972 (1999).

Seidel, D. J. et al. Climatology of the planetary boundary layer over the continental United States and Europe. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D17106 (2012).

Bershaw, J., Penny, S. M. & Garzione, C. N. Stable isotopes of modern water across the Himalaya and eastern Tibetan Plateau: implications for estimates of paleoelevation and paleoclimate. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D02110 (2012).

Sodemann, H., Schwierz, C. & Wernli, H. Interannual variability of Greenland winter precipitation sources: Lagrangian moisture diagnostic and North Atlantic Oscillation influence. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D03107 (2008).

Oza, H., Padhya, V., Ganguly, A. & Deshpande, R. D. Investigating hydrometeorology of the Western Himalayas: insights from stable isotopes of water and meteorological parameters. Atmos. Res 268, 105997 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Temporal variations of stable isotopic compositions in atmospheric water vapor on the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau and their controlling factors. Atmos. Res. 303, 107328 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Autorità di Bacino Distrettuale dell’Appennino Settentrionale— Misure di prevenzione tese a supportare ed ottimizzare la pianificazione di gestione, la programmazione e realizzazione degli interventi di cui al PGRA (F54J16000020001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali, Andrea Columbu, Giovanni Zanchetta, Monica Bini; Methodology: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali; Formal analysis: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali; Investigation: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali; Data curation: Marco Luppichini; Visualisation: Marco Luppichini; Writing—original draft: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali, Andrea Columbu, Giovanni Zanchetta, Monica Bini; Writing—review & editing: Marco Luppichini, Stefano Natali, Andrea Columbu, Giovanni Zanchetta, Monica Bini; Supervision: Giovanni Zanchetta, Monica Bini; Project administration: Monica Bini; Funding acquisition: Monica Bini.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Marco Chericoni, Doğukan Doğu Yavaşlı and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Nicola Colombo and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luppichini, M., Natali, S., Columbu, A. et al. Mediterranean precipitation variability is driven by complex atmospheric mechanisms beyond the North Atlantic Oscillation. Commun Earth Environ 7, 81 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03104-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03104-4