Abstract

Rivers are major pathways for terrigenous plastics to the ocean, yet the spatio-temporal variability of plastic flux remains poorly quantified. Here, we conducted annual field monitoring of plastic particle fluxes in the Yangtze River, accounting for both vertical and horizontal variations in plastic distribution within the estuary. Microplastics were ubiquitous but exhibited spatial and temporal heterogeneity. Microplastics abundance declined with increasing depth, and the central channel exhibited lower microplastic abundance compared to the left and right channels. Monthly trends were consistent across channels within the same water layer. Hydrological patterns primarily regulated microplastic occurrence, with microplastic abundance decreasing at higher flow rates, while particle size correlated positively with flow. We estimated an annual flux of 5.20×1015 microplastic particles, of which 74.6% were small particles, posing substantial ecological risks due to their high toxicity and ingestion potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rivers serve as vital arteries connecting land and sea, acting as crucial channels for the exchange of various pollutants1. A matter of increasing concern is the release of plastic waste from land-based sources, such as rivers and coastal runoff, into the oceans, which accounts for approximately 80% of marine plastic inputs2,3. Recognizing the gravity of this issue, the fifth United Nations Environment Assembly adopted a landmark resolution in 2022 to negotiate a legally binding international agreement that addresses the entire lifecycle of plastics, from production to disposal, with the goal of substantially reducing plastic pollution4. Understanding the fluxes of riverine microplastics into the marine environment is an important scientific step that can inform effective management strategies and support evidence-based policymaking to tackle this global challenge.

However, current estimates of riverine microplastic fluxes are subject to major uncertainties5. Early model-based studies on microplastic fluxes encountered problems related to overestimation and underestimation1,6,7. The primary issue stemmed from the very limited availability of actual measured microplastic data at river estuaries, resulting in uncertainties in model predictions. Relying exclusively on a model that utilizes socioeconomic data such as population figures, plastic production rates, and plastic waste emissions has contributed to considerable fluctuations in the model’s estimates of riverine microplastic flux into the ocean. These variations have been observed across different studies and span several orders of magnitude5. Additionally, this approach overlooks the impacts of numerous artificial barriers, which can obstruct 65% of the plastic waste before it reaches the ocean1,8,9.

The second error arises from the choice of sampling strategy. Widely used trawling or net-based methods tend to capture only the large-sized microplastics (>300 μm), excluding smaller fractions10. However, recent studies show that small-sized microplastics (<300 μm) can dominate both the number and mass of particles in riverine environment8,11,12, indicating that excluding these smaller particles may substantially underestimate microplastic fluxes to the ocean. Their small size facilitates ingestion by plankton, bivalves, fish larvae, and other filter-feeding organisms, leading to physical blockage, reduced feeding efficiency, impaired growth, and reproductive disruption13,14. Furthermore, microplastics can adsorb and transport hydrophobic organic pollutants and heavy metals, acting as vectors for toxic substances that bioaccumulate through the food web15,16,17. In estuarine systems, where salinity gradients and hydrodynamic mixing are pronounced, these particles may accumulate in sediments or benthic habitats, posing long-term risks to benthic communities18. Consequently, accurately quantifying riverine microplastic fluxes is not only essential for estimating plastic inputs to the ocean but also for assessing potential ecological impacts on coastal and marine ecosystems.

The third error originates from the spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the distribution profile of microplastics. Past studies have indicated that large quantities of plastic debris remain concealed beneath the ocean’s surface, and the thermal stratification process can impact the vertical stratification of microplastics19,20. Moreover, flow velocities exhibit variations across distinct positions within the river estuary due to factors like channel topography, bed morphology, fluid dynamics, and potential human interventions21. Consequently, microplastic concentrations vary substantially in time and space due to hydrodynamic complexity, including vertical stratification and lateral heterogeneity influenced by bathymetry, flow velocity, and anthropogenic structures. Depending solely on a single surface water sampling for microplastic concentration to estimate the annual microplastic fluxes at the river estuary is an unreliable approach.

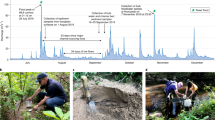

To overcome these limitations, this study conducted a year-round, high-resolution investigation of microplastic distribution and fluxes in the Yangtze River estuary. By integrating vertical and horizontal distribution data with synchronous flow measurements from November 2021 to October 2022 (Fig. 1), we provide an empirically grounded estimate of microplastic discharge. Understanding the complexities of microplastic transport is pivotal for developing sustainable strategies to safeguard the vital interconnectedness between land and sea.

Results and discussion

Hydrological regimes impact microplastic particle abundance

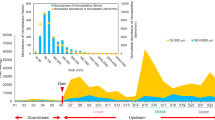

Microplastics were detected in all samples during the one-year monitoring period. The monthly average microplastic abundance at the river estuary was recorded at 9745 ± 3995 nm–3 (Fig. 2a and Table S1), which was 57% higher than the microplastic abundance in the upstream of the Yangtze River utilizing a similar sampling and analytical methodology22. Notably, the presence of microplastics at the river estuary displayed substantial variation across different months, spanning from 1043 ± 1354 nm–3 in October to 26,457 ± 34,216 nm–3 in January (Fig. 2a‒c and Table S1). Such high variability of microplastic abundance was potentially attributed to spatiotemporal heterogeneity driven by hydrological regimes, particle resuspension, and anthropogenic inputs23.

a Variations of monthly average microplastic abundance and hydrological flow rates. b-c Variations of monthly average microplastic abundance in the surface, middle, and bottom layers (b), as well as within the left, central, and right channels (c). d Relative ranking of monthly average microplastic abundances (%) across different water periods (dry, normal, and wet), layers (upper, middle, and lower), and channels (left, central, and right). Percentages indicate comparative abundance levels rather than actual contributions to total microplastic flux.

Our results further suggested that the hydrological regime of the Yangtze River influenced the distribution of microplastics, as substantiated by the anticipated negative association between microplastic abundance and hydrological flow rates (p < 0.1, Figs. 2a and 3). For instance, in June, there was a relatively low microplastic abundance of 3986 ± 1829 nm–3 juxtaposed with a high flow rate of 50,600 m–3 s–1 (Table S1). Conversely, in January, the highest microplastic abundance of 26,457 nm–3 was recorded, whereas the flow rate remained markedly low at 14,000 m–3 s–1 (Table S1).

This inverse relationship can be primarily driven by a balance between mobilization of microplastics from sediments under certain conditions and dilution with increasing discharge24. During low-flow periods, the reduced current velocity may limit hydrodynamic energy, thereby reducing the transfer of microplastics from sediments into the water column25,26. However, sediment disturbance (e.g., by wind, boat traffic, or other physical processes) during low flow may still cause resuspension of particles, including previously deposited microplastics26,27,28. Additionally, the prolonged hydraulic residence time under low discharge conditions allows for the accumulation of suspended particles, including microplastics29. This effect is especially pronounced in tidal estuarine zones, where periodic current velocity inversions caused by tidal cycles interact with riverine flow, leading to complex sediment dynamics and weak net flushing capacity30,31,32,33. Such tidal processes can trap microplastics within the estuary, promoting their local retention and accumulation before eventual downstream export34,35. Conversely, heightened river flow not only dilutes microplastics but also accelerates their transport and deposition, thereby reducing their presence in the water body36,37.

This correlation was further underscored by variations in microplastic abundance during different hydrological periods (Fig. 2d and Table S2). Specifically, during both the dry and normal periods, the average microplastic abundance was substantially higher, with values of 10,338 ± 7384 nm–3 and 11,174 ± 6067 nm–3, respectively, in contrast to the wet period, which exhibited a much lower average abundance of only 3407 ± 902 nm–3 (p < 0.05, Fig. 2d and Table S2). While high flows during wet periods dilute microplastic concentrations in the water column, they may simultaneously enhance long-range transport of microplastics to coastal and offshore regions38. Such transport can increase the exposure risk to marine ecosystems, as microplastics can serve as vectors for harmful pollutants and pose direct threats to marine organisms15,16,17.

High spatial heterogeneity in microplastic distribution throughout the water column profile

The distribution of microplastics in the upper, middle, and lower layers of the river, as well as in the left, central, and right channels, exhibited pronounced heterogeneity, with abundance variations spanning three orders of magnitude, ranging from 100 to 99,600 nm–3 (Fig. 2b, c). The coefficient of variation across the sites ranged from 46% to 130% for each month, highlighting substantial spatial heterogeneity (Table S1). Although a general similarity in the monthly trends of microplastic abundance was observed within the same water layer, pronounced variations in abundance were evident between the different water layers (Fig. 4). These pronounced vertical and horizontal differences indicate that relying solely on surface water measurements can substantially miscalculate total microplastic flux in river estuaries39,40,41. Therefore, both vertical stratification and lateral heterogeneity must be accounted for to obtain accurate flux estimates.

Upon observing the vertical distribution within the river’s central channel, we discovered that the abundance of microplastics gradually decreased as water depth increased (Fig. 2b and Table S1). The annual mean abundance of microplastics in the surface water was 8110 ± 12,400 nm–3, which subsequently decreased to 6878 ± 7761 nm–3 in the middle layer. Finally, in the bottom layer, near the riverbed, the abundance of microplastics further decreased to 4730 ± 4005 nm–3. This differs sharply from lentic reservoirs and inland rivers, where factors such as low flow rates, thermal stratification, and the interaction of microplastics with algae and metals facilitate their deposition, leading to higher microplastic abundance in deeper layers20,42,43. In fast-moving rivers, microplastics predominantly remain on the surface layer due to the substantial disturbances that prevent their smooth settling44,45. These results indicate that changes in the hydrological regime can strongly influence the vertical migration of microplastics. In estuarine systems, this process is further shaped by the maximum turbidity zone, where riverine and tidal currents converge, causing suspended sediments and microplastics to accumulate46. Acting as a dynamic retention area, the maximum turbidity zone traps fine particles and promotes local deposition before they are exported to coastal waters30,47. The location and strength of the maximum turbidity zone vary seasonally with shifts in freshwater discharge and tidal forcing, which in turn regulate the vertical distribution and ultimate fate of microplastics within the estuary26. This quantification also underscores the critical importance of vertical sampling in generating robust and defensible flux estimates, particularly in highly dynamic riverine systems where physical stratification, including potential salinity gradients, may influence microplastic distribution48. Future work incorporating salinity profiles would provide deeper insights into the mechanisms driving vertical heterogeneity.

Regarding the horizontal distribution of microplastics, the total average abundance of microplastics in the left channel (11,075 ± 14,889 nm–3) and right channel (11,610 ± 21,790 nm–3) was 69–77% greater than that in the central channel (6573 ± 7733 nm–3) (Fig. 2c and Table S1). The left and right channels are characterized by shallow water, high turbulence, substantial friction, and slow flow rates, which are more conducive to the accumulation of microplastics46,49. In contrast, the central channel features deeper water and faster flow rates, which promote downstream transport and reduce local retention, consistent with observations from other estuarine systems50,51.

Furthermore, anthropogenic activities may partly explain the lateral heterogeneity observed in microplastic distribution. Microplastics from terrestrial sources are more likely to enter the shallower left and right channels due to their proximity to human settlements, municipal sewage outfalls, port facilities, and ship traffic lanes52,53,54. Such localized inputs can increase both the abundance and retention of microplastics in these channels. To verify this hypothesis, future work could incorporate surrounding land-use data—including industrial zones, wastewater treatment infrastructure, and vessel density maps—to explore possible spatial correlations with microplastic hotspots55.

Small polyethylene and polypropylene (<300 μm) dominate microplastics in the river estuary

Observed microplastic particle sizes ranged between 15 and 3600 μm, with an average mean size of 223 μm (Fig. 5a and Table S3). Approximately 82% of the particles were within the size range of <300 μm, defined here as small-sized microplastics. It is worth highlighting that the commonly employed trawling sampling technique employs mesh sizes ranging from 50 to 300 μm56, potentially overlooking the substantial contamination and associated risks posed by these small-sized microplastics. Laboratory studies have shown that particles in this size range exhibit 3–5 times higher adsorption capacity for persistent organic pollutants compared to larger fragments due to their increased surface area-to-volume ratio57,58. Furthermore, field observations in the East China Sea indicate that 68% of zooplankton species examined contained ingested microplastics predominantly in the 20–300 μm range59,60. This highlights the critical need to prioritize particle-number flux metrics in ecological risk assessments, even if mass-based values appear less alarming8.

a Size distribution of total microplastics and the three dominant polymer types: polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), and the co-polymer of PP and PE (EPM). b Monthly variation in the average mean size with hydrological flow rates. c Changes in microplastic particle size in different channels during dry, normal, and wet periods. d Changes in microplastic particle size in different layers during dry, normal, and wet periods in the central channel.

Neglecting small microplastics can distort our understanding of overall microplastic composition. Of the 6505 identified plastic debris items, a total of 13 distinct plastic polymers were identified in the river estuary (Table S3). Polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and their copolymers constituted 75%, 18%, and 4.5% of the total composition, respectively (Table S3 and Fig. S1). Notably, these three predominant polymers predominantly manifested as small-sized particles (<300 μm), with average particle dimensions of 226, 195, and 222 μm, respectively (Fig. 5a). Consequently, the omission of these small particles can result in an underestimation of the proportions of certain polymer types, such as PE and PP, which pose a threat to marine organisms. The ecological risks associated with these small PE and PP microplastics are particularly concerning in marine environments59,60. Furthermore, processes such as mineralization and oxidative fragmentation disintegrate larger plastic particles into smaller fragments61. Ocean hydrology is stratified and intricate, with a pronounced tendency for the selective deposition of small-sized microplastics in high-calcium and high-salt environments, posing irrevocable threats to benthic ecology18. Due to the relatively low densities of PE and PP, both polymers are neutrally or positively buoyant in seawater, enabling them to remain suspended in the water column for extended periods62. This prolonged residence time increases the likelihood of ingestion by plankton and other filter-feeding organisms, thereby enhancing their potential for bioaccumulation and trophic transfer63. Studies have demonstrated that <300 μm microplastics are readily consumed by copepods, bivalves, and fish larvae, disrupting feeding, energy allocation, and reproduction64,65.

Interestingly, this study revealed a dominant proportion of PE and PP exceeding 90% across the entire cross-section, with proportions of 96%, 96%, and 94% in the surface, middle, and bottom layers, respectively (Table S3). In the surface layer, this proportion was notably higher than that observed upstream under comparable methodologies, where PP and PE together constituted less than 70%8,22,66,67. These findings provide insights into the selective settling and fragmentation of microplastics during transport. Several factors may account for this downstream enrichment of buoyant polymers. First, the low density of PE and PP facilitates their transport over long distances under hydrodynamic conditions, while denser polymers are more likely to settle upstream62. Second, these polymers are commonly used in domestic packaging and cleaning products, and their prevalence in treated and untreated wastewater discharges from urban areas—particularly downstream megacities such as Shanghai—may further increase their downstream concentration68. Third, increasing salinity gradients towards the estuary mouth reduce water density differences relative to these polymers, enhancing their floatability and further promoting their downstream retention and accumulation48. Collectively, these findings imply that polymer-specific characteristics, land use, human activity, and salinity dynamics jointly influence spatial trends in polymer distribution.

The particle size distribution of microplastics exhibited pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity (Figs. 5b, c and S2–3). Notably, the average particle size of microplastics in the central channel exceeded those in the left and right channels (Figs. 5c and S4). Within the central channel, the bottom layer exhibited the largest particle size, followed by the surface and middle layers (Figs. 5d and S4). One possible explanation is that weaker bottom turbulence and increased deposition near the riverbed allow larger particles to settle, especially in the deeper central channel, where shear stress may fall below the critical threshold for resuspension25,69,70. Sediment—microplastic interaction studies have shown that larger microplastics are more likely to be trapped in bed sediments or aggregate with particulate matter under low-energy conditions27,30,70. This could explain the observed accumulation of large microplastic particles in the bottom layer of the central channel.

Furthermore, the particle size of microplastics was positively correlated with the hydrological flow rates (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5b), suggesting that the hydrological regime strongly influenced the distribution and stratification of microplastics. The microplastic particle size averaged 279.29 μm during the wet period, 235.37 μm during the normal period, and 210.25 μm during the dry period. This trend suggests that higher river flow allows larger microplastic debris to enter the river system from surrounding terrestrial sources but also enhances the remobilization of previously deposited microplastics, facilitating their downstream transport toward the estuary (Figs. 5c and S4).

Focusing on the vertical distribution within the central channel, the size patterns varied among water layers and hydrological periods (Figs. 5d and S4). Specifically, the particle size of microplastics in the bottom layer was the largest during the dry period, whereas that in the surface and middle layer reached its peak during the wet period. This suggests that as hydrological flow rates increase, microplastics with larger particle sizes tend to accumulate in surface water. One possible explanation is that during high-flow periods, runoff and stronger turbulence transport greater quantities of large fragments of low-density polymers such as PE and PP from upstream into the river system51. Given their lower buoyancy, these polymers are more likely to remain suspended near the surface rather than settling, thereby contributing to the observed enrichment of larger particles in the surface layer during the wet period70.

Estimation of the fluxes of microplastic in the river estuary

The annual particle flux of microplastics was calculated to be 5.20 × 1015 particles, with the monthly microplastic flux ranging from 2.67 × 1013 to 1.38 × 1015 particles (Table S1). The annual fluxes of PP and PE were found to be 3.83 × 1015 and 9.96 × 1014 particles, respectively, with the remaining polymer types contributing 3.78 × 1014 particles. Notably, the annual flux of small-sized microplastics was determined to be 3.88 × 1015 particles, constituting 74.6% of the total particle flux.

Regarding the vertical distribution of microplastics, exclusively relying on microplastic abundance in the surface layer for estimating microplastic flux, we calculated an annual particle flux of 2.26 × 1020 (Table S4). This result represents an overestimation of approximately four orders of magnitude compared to the calculation using the average microplastic abundance in the river estuary cross-section (5.20 × 1015). Horizontally, the central channel of the river estuary contributed an annual emission of 2.85 × 1015 particles into the marine environment, surpassing the combined particle fluxes observed in both the left and right channels (2.35 × 1015 particles) (Table S5). This disparity is primarily attributed to the much larger water volume passing through the central channel compared with the left and right channels.

The peak total number of microplastic particles transported from the Yangtze River estuary to the ocean occurs during the normal water period (2.28 × 1015 particles), accounting for 44.4% of the annual total (Table S2). The wet period followed, with a total microplastic particle flux of 1.59 × 1015 particles (31.1%). The lowest flux occurred during the dry period, with a microplastic particle flux of 1.26 × 1015 particles, representing only 24.5% of the annual total. For context, the wet period represents 40% of the annual water discharge but occurs over only two months. This indicates that nearly one-third of the annual microplastic loading to the ocean is delivered within a very short time frame, resulting in highly episodic transport events. In contrast, the normal water period extends 5 months, during which moderate but sustained river flows deliver a slightly higher total microplastic flux. Although the increased water volume during the wet period has a dilution effect on microplastic abundance, the elevated flow velocity greatly enhances downstream transport capacity and dispersal. This means that while local abundance and flux may appear reduced, high-discharge events can carry microplastics further offshore8,71,72, extending their spatial reach and increasing ecological risks to pelagic ecosystems and marine organisms beyond the estuarine boundary73. Similar hydrodynamic-driven offshore transport has been observed in other large river systems under high-flow events, underscoring the need to assess the ecological implications beyond estuarine boundaries50,74,75.

Following mass conversion, our estimations indicate that the Yangtze River annually transports approximately 9216 ± 600 tons of microplastics into the ocean based on whole water column measurements (Table S4). Based on morphological classification, an estimated 4.08 × 1015 non-fiber particles and 1.12 × 1015 fiber particles were transported annually (Table S6). Despite the high numerical abundance of fibers, they contributed only 1.7% (160 tons) to the total annual mass flux (9216 tons), whereas non-fiber microplastics accounted for 98.3% (9056 tons) (Table S6), underscoring the dominance of denser, non-fibrous particles in total mass transport. Notably, if flux were estimated using only surface layer abundance, the value would rise to 84,010 tons, representing an overestimation of approximately 8 times (Table S4). This highlights the importance of incorporating vertical microplastic distribution when quantifying riverine plastic export. For comparison with previous studies that relied on surface-layer data, our surface-layer measurement-based assessments are comparatively lower than previous model predictions (3.33 × 105 tons)1. Although their model does include dams and artificial barriers as sinks for plastic particles, our lower value likely reflects additional retention in terrestrial environments, localized sediment trapping, differences in plastic size classes considered, and other hydrodynamic retention processes not fully resolved in large-scale models76. Conversely, our surface-layer estimation falls one order of magnitude above the previous findings using the trawling sampling approach (538‒906 tons) based on several months field research7. The length and continuity of sampling strategy have a major impact on the estimation of flux. Our study has shown that the abundance of microplastics and water flow rate varied in different hydrological periods. Therefore, studies based on short-term sampling may miss peak events or underestimate background variability. Our surface-layer estimation aligns more closely with the estimation by a recent study based on actual measurements (6750‒33,600 tons)6, positioning our findings towards the lower end of this range.

The mass of microplastic was estimated using the particle size for each particle and assuming a simplified spherical geometry, combined with the literature-reported densities of the dominant polymers (see “Methods”). However, this approach, like those used in previous studies, faces substantial challenges in accurately estimating the mass abundance of microplastics, primarily due to uncertainties in volume and density determination. The μ-FTIR technique provides only two-dimensional measurements of particle length and width, without information on thickness, which can lead to substantial errors in volume estimation, particularly for small or thin, planar particles. Natural microplastics also exhibit highly irregular and fragmented shapes, and environmental processes such as prolonged water immersion, biofouling, and weathering can alter their density. Because particle mass scales with the cube of the radius, even minor measurement errors can result in large uncertainties. While direct weighing of individual microplastics is often impractical, future studies employing advanced 3D imaging or micro-CT techniques could greatly improve the precision of microplastic mass and shape characterization77,78, thereby enabling more accurate assessments of microplastic mass fluxes.

Conclusion

This study revealed a substantial discharge of microplastics from the Yangtze River into the ocean and highlighted pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity in their distribution within the estuary. Microplastic abundance exhibited a tentative inverse correlation with flow rate. Larger particles generally accumulated in deeper layers of the central channel, whereas higher flow rates promoted their redistribution toward shallower layers. The annual microplastic particle flux was estimated at 5.20 × 1015 particles (9216 ± 600 tons), with 31.1% of particles transported during the two-month wet period. Notably, relying solely on surface-layer measurements overestimated particle and mass flux by 43 and 8 times, respectively. These findings underscore the importance of spatially and temporally resolved sampling for accurately quantifying microplastic fluxes.

Methods

Study area

The Yangtze River is the longest river in China, spanning over 6300 km in length, with a basin area of approximately 1.8 × 106 km2. The average annual flow is approximately 29,300 m3 s‒1, contributing to a yearly runoff of 9.051 × 1011 m3. The Yangtze River Basin has a high population density, diverse land use patterns, and a developed economy, resulting in a strong demand for plastic products, and consequently, high volumes of plastic waste are discharged into the environment6.

The Yangtze River Estuary is located in northern Shanghai. The Xuliujing monitoring section, situated along its main stem, features a distinctive topography. It is a typical compound-section riverbed divided into a central main channel and side banks on the left and right sides. The annual average water depth of the main channel is approximately 40 m, whereas the side banks on both shores have an average water depth of approximately 10 m.

Sampling method

Three sampling channels were established in the Xuliujing monitoring section of the Yangtze River estuary: left, central, and right (Fig. 1). Surface water samples were collected at 0.5 m below the water surface, bottom water samples were collected at 0.5 m above the riverbed, and middle water samples were collected from the midpoint of the central channel. Surface and bottom water samples were collected from both the left and right banks of Xuliujing, whereas surface, middle, and bottom water samples were collected from the central channel. Water samples were collected using a calibrated depth sampler (model HAQCC15-5L; Beijing Heng Odd Instrument Co., Ltd., China). At each sampling location, two 5 L subsamples were collected and combined into a single composite sample. Depth measurements were obtained using a graduated sounding rod prior to sample collection, enabling precise positioning of the sampler at 0.5 m above the riverbed. All samples were transported to the laboratory in stainless steel containers without filtration during sample collection. Continuous monthly monitoring was conducted from November 2021 to October 2022, spanning one year. Sampling was not performed in April and May due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, but data from the remaining ten months sufficiently captured seasonal variations. During each sampling campaign, seven locations were sampled to represent the cross-sectional distribution of microplastics. At each location, two subsamples were collected and thoroughly mixed to form one composite sample, improving representativeness and reducing local variability. In total, seven composite samples were collected each month, resulting in 70 samples across 10 months. All sampling was conducted during ebb tide, when freshwater discharge is dominant and tidal backflow from the sea is minimal, to reduce the risk of particle retention or seawater intrusion influencing the results79. Hydrological data for the Xuliujing monitoring section were obtained from the Changjiang Water Resources Commission of the Ministry of Water Resources (http://www.cjw.gov.cn/zwzc/zjgb/). Based on the monthly river flow volume, December, January, September, and October were classified as dry periods. November, February, March, and August were designated as normal periods, while June and July were classified as wet periods. This sampling design captured both temporal variability across hydrological periods and spatial heterogeneity within the cross-section. Compared to previous studies that often relied on only a few discrete sampling events or focused solely on surface water, our approach represents a substantially larger sampling effort, consistent with recommendations for high-resolution monitoring in large river systems46,80,81.

Microplastic extraction

Sample pretreatment was conducted according to the method described in previous research82,83. The collected water samples were initially filtered using a vacuum filtration pump through a stainless-steel membrane with a pore size of 0.01 mm. This filtration process retained substances from the water on a stainless-steel filter membrane. The stainless-steel filter membrane containing the filtered material was then placed in a 250 mL glass beaker.

A 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution was used to digest organic matter. The sample solution, containing 20 mL of 30% H2O2, was placed on a temperature-controlled hotplate set at 60 °C to remove organic materials84. This process generated bubbles. After the complete reaction of the bubbles, the organic matter was still visible, and an additional 20 mL of 30% H2O2 was added. In general, two rounds of H2O2 were added. After the absence of bubbles and visible organic matter indicated the completion of dissolution, the sample was transferred to an ultrasonic water bath to subject the substances onto a stainless-steel filter membrane for ultrasonic treatment, thereby shaking them in an aqueous solution. After the ultrasonic treatment, any remaining substances on the stainless-steel filter membrane were rinsed in the sample solution in a beaker using ultrapure water. A saturated NaCl solution (density = 1.2 g cm‒3) was used for flotation at 60 °C for 12‒24 h.

After flotation, the supernatant of the sample solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The filter membrane was placed in a petri dish and dried in an oven at 60 °C. Finally, the test samples were sealed with aluminum foil for subsequent analyses.

Microplastic identification

All samples were observed and photographed using a high-definition microscope (SC-III, Shanghai, China). The suspected microplastic particles were carefully isolated using a sampling needle and transferred onto barium fluoride windows (13 mm diameter, Thermo Scientific, USA) for spectroscopic analysis85. Each window contained approximately 50–1471 suspected particles, a density chosen to prevent particle overlap and ensure accurate individual identification. A micro-fourier transform infrared spectrometer (μ-FTIR, Nicolet iN10MX, USA) was used to detect and identify the polymer types of the samples.

The polymer type of the detected particles was identified by comparing the spectra of the tested samples with those of standard materials in the spectral library of the instrument. If the match exceeded 70%, the particle was identified as a microplastic, and its quantity, type, size, shape, and other characteristics were manually recorded.

In total, 9892 suspected particles were initially suspected, of which 6505 were conclusively identified as microplastics using micro-FTIR, resulting in a detection rate of 65.8%. Microplastic abundance is expressed as nm‒3. The particle sizes were categorized into small microplastics (15–300 μm) and large-sized microplastics (300–3600 μm). The morphologies of the microplastics were primarily fibrous or non-fibrous.

Quality insurance and quality control

A series of measures was implemented to prevent sample contamination. No plastic material was used during the preprocessing. All the experimental tools and instruments were washed with ultrapure water at least three times before use. During the experiments, the researchers wore masks and cotton lab coats. The samples were sealed with aluminum foil to prevent air pollution. The experimental analyses were conducted in a laboratory that was cleaned daily. To assess potential contamination, one procedural blank was included for each batch processed on the same day. The blanks consisted of ultrapure water that was handled identically to the field samples, including being left uncovered near the samples during processing to monitor airborne contamination. No plastic particles were detected in any blank samples, indicating that laboratory contamination was negligible.

Mass conversion

The conversion of the microplastic mass concentration was achieved by distinguishing between two morphologies: fibrous and non-fibrous. Fibrous microplastics are treated as small cylinders, and their particle mass is calculated as follows:

where Mfiber is the mass of fibrous microplastics (g particle‒1), r is the radius of the fibrous microplastic (cm), h is the length of the fiber (cm), and 1.04 is the average density of the microplastics (g cm‒3)86.

Non-fibrous microplastics are treated as flattened spheres, and the particle mass is calculated as follows:

where Mnonfiber is the mass of non-fibrous microplastics (g particle‒1), r is the radius of the sphere (cm), 1.04 is the average density of the microplastics (g cm‒3)86, and α is the shape factor with a value of 0.187.

Estimation of microplastic fluxes from river to sea

Owing to the unique topography of the Xuliujing monitoring section on the main stem of the Yangtze River Estuary, which constitutes a typical compound section, the annual average water depth of the central channel was approximately 40 m, whereas the average water depth on the left and right banks was only approximately 10 m. Consequently, the microplastic flux from the left, central, and right channels into the ocean for the i month was calculated as follows:

where Fi-left, Fi-central, and Fi-right represent the total microplastic flux into the ocean from the left, central, and right channels for the i month (tons), respectively, Ci-left, Ci-central, and Ci-right is the microplastic abundance on the left, central, and right channels for the i month (particle m‒3), respectively, Mi-left, Mi-central, and Mi-right is the particle mass of microplastics on the left, central, and right channels for the i month (g particle‒1), respectively, Qi stands for the river’s discharge for the i month (m3), and the flow coefficients for the left, central, and right channels, bleft, bcentral, and bright are 0.22, 0.67, and 0.11, respectively. These coefficients were determined based on the cross-sectional area88.

The total microplastic flux from the Yangtze River Estuary into the sea in the i month (Fi) was calculated as follows:

The annual microplastic flux into the Yangtze River estuary is calculated as:

Statistical analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate spatial and temporal variations in microplastic abundance and flux. Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the relationship between microplastic flux and hydrological parameters (e.g., discharge, turbidity). All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (v4.2.1), and significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The data used in this study are included in the article and are publicly available through Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26196122.v1. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Code availability

This paper does not report original code(s).

References

Lebreton, L. C. M. et al. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat. Commun. 8, 15611 (2017).

Jambeck, J. R. et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 347, 768–771 (2015).

Morales-Caselles, C. et al. An inshore–offshore sorting system revealed from global classification of ocean litter. Nat. Sustain. 4, 484–493 (2021).

United Nations Environment Assembly. End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi (2022).

González-Fernández, D., Roebroek, C. T. J., Laufkötter, C., Cózar, A. & van Emmerik, T. H. M. Diverging estimates of river plastic input to the ocean. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 424–426 (2023).

Mai, L. et al. Global riverine plastic outflows. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10049–10056 (2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Analysis of suspended microplastics in the Changjiang Estuary: implications for riverine plastic load to the ocean. Water Res. 161, 560–569 (2019).

Gao, B., Chen, Y., Xu, D., Sun, K. & Xing, B. Substantial burial of terrestrial microplastics in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 32 (2023).

Guo, Z. et al. Global meta-analysis of microplastic contamination in reservoirs with a novel framework. Water Res. 207, 117828 (2021).

Nava, V. et al. Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs. Nature 619, 317–322 (2023).

Landebrit, L. et al. Small microplastics have much higher mass concentrations than large microplastics at the surface of nine major European rivers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 32, 10050–10065 (2025).

Poulain, M. et al. Small microplastics as a main contributor to plastic mass balance in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1157–1164 (2019).

Ding, J. et al. Elder fish means more microplastics? Alaska pollock microplastic story in the Bering Sea. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf5897 (2023).

Kvale, K., Prowe, A. E. F., Chien, C. T., Landolfi, A. & Oschlies, A. Zooplankton grazing of microplastic can accelerate global loss of ocean oxygen. Nat. Commun. 12, 2358 (2021).

Marcharla, E. et al. Microplastics in marine ecosystems: a comprehensive review of biological and ecological implications and its mitigation approach using nanotechnology for the sustainable environment. Environ. Res. 256, 119181 (2024).

Yang, H., Chen, G. & Wang, J. Microplastics in the marine environment: sources, fates, impacts and microbial degradation. Toxics 9, 41 (2021).

Ali, S. S., Elsamahy, T., Al-Tohamy, R. & Sun, J. A critical review of microplastics in aquatic ecosystems: degradation mechanisms and removing strategies. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 21, 100427 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Unveiling the vertical migration of microplastics with suspended particulate matter in the estuarine environment: roles of salinity, particle properties, and hydrodynamics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 2944–2955 (2024).

Pabortsava, K. & Lampitt, R. S. High concentrations of plastic hidden beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 4073 (2020).

Zhang, M., Xu, D., Liu, L., Wei, Y. & Gao, B. Vertical differentiation of microplastics influenced by thermal stratification in a deep reservoir. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 6999–7008 (2023).

Talbot, R. & Chang, H. Microplastics in freshwater: a global review of factors affecting spatial and temporal variations. Environ. Pollut. 292, 118393 (2022).

Xu, D., Gao, B., Wan, X., Peng, W. & Zhang, B. Influence of catastrophic flood on microplastics organization in surface water of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Water Res. 211, 118018 (2022).

Leads, R. R. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of microplastic abundance in estuarine intertidal sediments: implications for sampling frequency. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160308 (2023).

de Carvalho, A. R. et al. Urbanization and hydrological conditions drive the spatial and temporal variability of microplastic pollution in the Garonne River. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144479 (2021).

Akdogan, Z. & Guven, B. Modeling the settling and resuspension of microplastics in rivers: effect of particle properties and flow conditions. Water Res. 264, 122181 (2024).

Xia, F., Yao, Q., Zhang, J. & Wang, D. Effects of seasonal variation and resuspension on microplastics in river sediments. Environ. Pollut. 286, 117403 (2021).

Constant, M., Alary, C., Weiss, L., Constant, A. & Billon, G. Trapped microplastics within vertical redeposited sediment: experimental study simulating lake and channeled river systems during resuspension events. Environ. Pollut. 322, 121212 (2023).

Collins, S. F. Bioturbation and the resuspension of plastic pollutants by spawning common carp degrades lake water quality. Sci. Total Environ. 984, 179718 (2025).

Owowenu, E. K., Nnadozie, C. F., Akamagwuna, F., Siwe-Noundou, X. & Odume, O. N. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in functionally delineated hydraulic zones in selected rivers, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Environ. Pollut. 379, 126544 (2025).

Pohl, F., Eggenhuisen, J. T., Kane, I. A. & Clare, M. A. Transport and burial of microplastics in deep-marine sediments by turbidity currents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 4180–4189 (2020).

Leiser, R. et al. Interaction of cyanobacteria with calcium facilitates the sedimentation of microplastics in a eutrophic reservoir. Water Res. 189, 116582 (2021).

Oo, P. Z., Boontanon, S. K., Boontanon, N., Tanaka, S. & Fujii, S. Horizontal variation of microplastics with tidal fluctuation in the Chao Phraya River Estuary, Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 173, 112933 (2021).

Alves, R. S. et al. How does the tidal cycle influence the estuarine dynamics of microplastics? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 211, 117471 (2025).

López, A. G., Najjar, R. G., Friedrichs, M. A. M., Hickner, M. A. & Wardrop, D. H. Estuaries as filters for riverine microplastics: simulations in a large, coastal-plain estuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 715924 (2021).

Li, G., Chen, Z., Bowen, M. & Coco, G. Transport and retention of sinking microplastics in a well-mixed estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 203, 116417 (2024).

Arnon, S. Making waves: unraveling microplastic deposition in rivers through the lens of sedimentary processes. Water Res. 272, 122934 (2025).

Lu, X., Wang, X., Liu, X. & Singh, V. P. Dispersal and transport of microplastic particles under different flow conditions in riverine ecosystem. J. Hazard. Mater. 442, 130033 (2023).

Yin, L. et al. Hydrodynamic driven microplastics in Dongting Lake, China: quantification of the flux and transportation. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 136049 (2024).

Pessenlehner, S., Gmeiner, P., Habersack, H. & Liedermann, M. Understanding the spatio-temporal behaviour of riverine plastic transport and its significance for flux determination: insights from direct measurements in the Austrian Danube River. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1426158 (2024).

Unnikrishnan, V. et al. Insights into the seasonal distribution of microplastics and their associated biofilms in the water column of two tropical estuaries. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 206, 116750 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Insights into the horizontal and vertical profiles of microplastics in a river emptying into the sea affected by intensive anthropogenic activities in Northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 779, 146589 (2021).

Mendrik, F. et al. The transport and vertical distribution of microplastics in the Mekong River, SE Asia. J. Hazard. Mater. 484, 136762 (2025).

Lenaker, P. L. et al. Vertical distribution of microplastics in the water column and surficial sediment from the Milwaukee River basin to Lake Michigan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12227–12237 (2019).

Born, M. P., Brüll, C., Schaefer, D., Hillebrand, G. & Schüttrumpf, H. Determination of microplastics’ vertical concentration transport (Rouse) profiles in flumes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 5569–5579 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Spatio-vertical distribution of riverine microplastics: impact of the textile industry. Environ. Res. 211, 112789 (2022).

Cui, T. et al. From surface to bottom: tracking the temporal and morphological heterogeneity of microplastics in the maximum turbidity zone of the Yangtze Estuary. J. Hazard. Mater. 495, 138944 (2025).

Soler, M., Colomer, J., Pohl, F. & Serra, T. Transport and sedimentation of microplastics by turbidity currents: dependence on suspended sediment concentration and grain size. Environ. Int. 195, 109271 (2025).

Mendrik, F., Fernández, R., Hackney, C. R., Waller, C. & Parsons, D. R. Non-buoyant microplastic settling velocity varies with biofilm growth and ambient water salinity. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 30 (2023).

Zhou, Q. et al. Trapping of microplastics in halocline and turbidity layers of the semi-enclosed Baltic Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 761566 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Accumulation, transformation and transport of microplastics in estuarine fronts. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 795–805 (2022).

He, B. et al. Dispersal and transport of microplastics in river sediments. Environ. Pollut. 279, 116884 (2021).

Chen, Y., Gao, B., Xu, D., Sun, K. & Li, Y. Catchment-wide flooding significantly altered microplastics organization in the hydro-fluctuation belt of the reservoir. iScience 25, 104401 (2022).

González-Fernández, D. & Hanke, G. Toward a harmonized approach for monitoring of riverine floating macro litter inputs to the marine environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 86 (2017).

Österlund, H. et al. Microplastics in urban catchments: review of sources, pathways, and entry into stormwater. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159781 (2023).

Meijer, L. J. J., van Emmerik, T., van der Ent, R., Schmidt, C. & Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Sci. Adv. 7, eaaz5803 (2021).

Prata, J. C., da Costa, J. P., Duarte, A. C. & Rocha-Santos, T. Methods for sampling and detection of microplastics in water and sediment: a critical review. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 110, 150–159 (2019).

Munoz, M., Ortiz, D., Nieto-Sandoval, J., de Pedro, Z. M. & Casas, J. A. Adsorption of micropollutants onto realistic microplastics: role of microplastic nature, size, age, and NOM fouling. Chemosphere 283, 131085 (2021).

Nguyen, T.-B. et al. Adsorption of lead(II) onto PE microplastics as a function of particle size: Influencing factors and adsorption mechanism. Chemosphere 304, 135276 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Retention and characteristics of microplastics in natural zooplankton taxa from the East China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 640-641, 232–242 (2018).

Zheng, S. et al. Characteristics of microplastics ingested by zooplankton from the Bohai Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 713, 136357 (2020).

Andrady, A. L. Weathering and fragmentation of plastic debris in the ocean environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 180, 113761 (2022).

Chubarenko, I., Bagaev, A., Zobkov, M. & Esiukova, E. On some physical and dynamical properties of microplastic particles in marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 108, 105–112 (2016).

Cole, M. et al. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6646–6655 (2013).

Rodrigues, S. M. et al. Bioavailability and ingestion of microplastics by fish larvae in the Douro Estuary. Biol. Life Sci. Forum. 13, 54 (2022).

Cole, M. & Galloway, T. S. Ingestion of nanoplastics and microplastics by Pacific Oyster Larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 14625–14632 (2015).

He, D. et al. Microplastics contamination in the surface water of the Yangtze River from upstream to estuary based on different sampling methods. Environ. Res. 196, 110908 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Microplastic pollution in the Yangtze River basin: heterogeneity of abundances and characteristics in different environments. Environ. Pollut. 287, 117580 (2021).

Sun, J., Dai, X., Wang, Q., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Ni, B.-J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res. 152, 21–37 (2019).

Isachenko, I. & Chubarenko, I. Transport and accumulation of plastic particles on the varying sediment bed cover: open-channel flow experiment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 183, 114079 (2022).

Kumar, R. et al. Effect of physical characteristics and hydrodynamic conditions on transport and deposition of microplastics in riverine ecosystem. Water 13, 2710 (2021).

Frishfelds, V., Murawski, J. & She, J. Transport of microplastics from the Daugava Estuary to the open Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 886775 (2022).

Schreyers, L. J. et al. River plastic transport affected by tidal dynamics. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 589–610 (2024).

van Emmerik, T., Mellink, Y., Hauk, R., Waldschläger, K. & Schreyers, L. Rivers as plastic reservoirs. Front. Water. 3, 786936 (2022).

Ji, X., Yan, S., He, Y., He, H. & Liu, H. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in surface seawater off the Yangtze River Estuary section and analysis of ecological risk assessment. Toxics 11, 889 (2023).

Diansyah, G., Rozirwan, Rahman, M. A., Nugroho, R. Y. & Syakti, A. D. Dynamics of microplastic abundance under tidal fluctuation in Musi estuary, Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 203, 116431 (2024).

Roebroek, C. T. J., Laufkötter, C., González-Fernández, D. & van Emmerik, T. The quest for the missing plastics: large uncertainties in river plastic export into the sea. Environ. Pollut. 312, 119948 (2022).

Parobková, V. et al. Advancing microplastic detection in zebrafish with micro computed tomography: a novel approach to revealing microplastic distribution in organisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 488, 137442 (2025).

Zhu, Z., Parker, W. & Wong, A. Microplastic mass quantification using focal plane array-based micro-fourier-transform infrared imaging. Environ. Eng. Sci. 41, 490–498 (2024).

Khalil, U., Sajid, M., Riaz, M. Z., Yang, S. & Sivakumar, M. Estuarine salinity intrusion and flushing time response to freshwater flows and tidal forcing under the constricted entrance. Water 17, 693 (2025).

Moses, S. R., Löder, M. G. J., Herrmann, F. & Laforsch, C. Seasonal variations of microplastic pollution in the German River Weser. Sci. Total Environ. 902, 166463 (2023).

Lu, H.-C., Ziajahromi, S., Neale, P. A. & Leusch, F. D. L. A systematic review of freshwater microplastics in water and sediments: recommendations for harmonisation to enhance future study comparisons. Sci. Total Environ. 781, 146693 (2021).

Wei, Y., Dou, P., Xu, D., Zhang, Y. & Gao, B. Microplastic reorganization in urban river before and after rainfall. Environ. Pollut. 314, 120326 (2022).

Niu, J., Gao, B., Wu, W., Peng, W. & Xu, D. Occurrence, stability and source identification of small size microplastics in the Jiayan reservoir, China. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 150832 (2022).

Huang, K. et al. Comprehensive assessment of various digestion protocols for extraction microplastics from organic-rich environmental matrices. Water Res. 282, 123935 (2025).

Xie, J., Gowen, A., Xu, W. & Xu, J. Analysing micro- and nanoplastics with cutting-edge infrared spectroscopy techniques: a critical review. Anal. Methods 16, 2177–2197 (2024).

Besseling, E., Quik, J. T. K., Sun, M. & Koelmans, A. A. Fate of nano- and microplastic in freshwater systems: a modeling study. Environ. Pollut. 220, 540–548 (2017).

Cózar, A. et al. Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10239 (2014).

Eo, S., Hong, S. H., Song, Y. K., Han, G. M. & Shim, W. J. Spatiotemporal distribution and annual load of microplastics in the Nakdong River, South Korea. Water Res. 160, 228–237 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues in the Changjiang River Estuary Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resource Survey for help with a range of field sampling and laboratory analyses. We thank for the financial support by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (42125703) and the Research & Development Support Program of China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research (WE0199A042021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and Y.W. designed the study, conducted the analyses, and co-authored the manuscript. D.X. and K.S. provided the analytical guidance and contributed to the manuscript. B.G. acquired the financial support and initiated the microplastics project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communication Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Nezha Mejjad and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Wei, Y., Xu, D. et al. Riverine emission of small plastic particles from Yangtze River into the ocean. Commun Earth Environ 7, 82 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03106-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03106-2