Abstract

The timing of leaf senescence critically shapes ecosystem dynamics by regulating plant productivity and nutrient cycling. While species diversity is recognized as a key driver of ecosystem functioning, its effect on autumn senescence remains poorly understood. To address this gap, here we integrated field observations from Northern China and global remote sensing data to investigate grassland autumn senescence. Our analyses reveal that higher species diversity accelerates autumn senescence, even after controlling for climate and soil factors. Mechanistically, this relationship is mediated by resource allocation strategies: enhanced species diversity promotes the allocation of resources to belowground biomass, thereby reducing aboveground resource availability and triggering earlier senescence. Our findings highlight a negative relationship between species diversity and the timing of autumn senescence in semi-arid grasslands, which facilitates increased carbon allocation to belowground compartments and accelerates the seasonal carbon cycle, offering critical insights into global carbon flux exchange under future climate warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shifts in plant phenology determine the length of the growing season and exert substantial impacts on ecosystem structure, functioning, as well as biophysical (e.g., surface albedo and evapotranspiration) and biogeochemical (e.g., terrestrial carbon cycle) processes1. While the influence of ongoing climate warming on the earlier onset of spring phenology has been well-documented2,3,4, the response of autumn phenology, i.e., the end of the growing season (EOS) to climate change remains unclear. This uncertainty is a critical knowledge gap, as the timing of autumn senescence is a critical regulator of ecosystem-level processes, governing nutrient resorption efficiency and the net seasonal carbon balance, which in turn generate crucial climate feedbacks5. This lack of clarity arises from the complex physiological events involved in the EOS process, including chlorophyll degradation, increased respiration, and nutrient remobilization6. These events are influenced by both abiotic factors (e.g., temperature, water conditions, and day length)7,8 and biotic factors (e.g., metabolic adjustments, vegetation activity, and phloem transport)2,9. Importantly, species diversity plays a critical role in modulating these phenological responses. For example, loss of biodiversity can alter the phenological plasticity of individual plants and reduce their ability to adapt to climatic changes, therefore advance the autumn senescence of tree10. However, the mechanistic role of species diversity in regulating phenological dynamics in grassland remains unclear, contributing to persistent uncertainties in modeling the terrestrial carbon cycle.

Previous field studies and experiments have highlighted the role of species diversity in maintaining the stability of ecosystem functions (e.g., productivity) through an “insurance” mechanism, where asynchronous species responses to environmental fluctuations ensure functional compensation and maintain aggregate ecosystem properties11. Remote sensing analyses have corroborated diversity-stability patterns at landscape scales12, although such approaches often fail to capture phenological variation13. More recent studies reveal that higher species diversity in plants can reduce phenological variability and lower phenological sensitivity to warming10,14, which may in turn reduce opportunities for growing-season extension by advancing spring phenology in anomalously warm years15. Mechanistically, increased diversity tends to reduce community-level phenological variance either by averaging disparate species responses or through dominance by conservative taxa. While such buffering lowers the risk of extreme mismatches and interannual variability, it can also decease response of community to favorable conditions (e.g., unusual warm spring or autumn)16. Consequently, diverse communities may show fewer instances of opportunistic growing-season extension, thereby limiting potential for greater productivity. Moreover, the relationship between productivity and phenology may be bidirectional, higher primary productivity can advance phenology via faster canopy development and local microclimatic feedbacks2,17,18. These considerations motivate our focus on how species diversity and productivity interact to determine phenological events, such as the EOS timing in semi-arid grasslands, ecosystems that are crucial for grazing, carbon storage, and human livelihoods yet are particularly vulnerable to climate change.

The positive relationship between species diversity and ecosystem functioning, commonly measured via productivity metrics, is driven by two key mechanisms: dominance effects and interspecific complementarity19,20,21,22,23. In addition, at landscape scales, species-rich communities with longer phenological periods may further enhance productivity12. For example, higher species diversity often leads to greater belowground biomass and root productivity24,25. This pattern can be attributed to niche complementarity and reduced competition in root systems, which allows for more efficient and extensive soil resource foraging26. Furthermore, root dynamics and carbon allocation patterns are increasingly recognized as key regulators of plant phenology. Strong sink strength in belowground organs (e.g., for nutrient storage or root growth) can accelerate the remobilization of nutrients from leaves27, a key process in senescence28. These considerations motivate our focus on how species diversity and productivity interact to determine phenological events, such as the EOS timing in semi-arid grasslands, ecosystems that are crucial for grazing, carbon storage, and human livelihoods yet are particularly vulnerable to climate change.

Here, we propose a mechanistic framework explaining how plant species diversity may regulate EOS timing in semi-arid grassland ecosystems (Fig. 1). The framework posits that greater species richness can promote niche complementarity and resource partitioning, which often leads to relatively greater investment in root systems to support complementary belowground functions. This shift in allocation alters whole-plant biomass balance and can reduce the proportional importance of aboveground biomass for controlling autumn phenology at the community scale. Simultaneously, increased belowground biomass and root activity can influence EOS may through two pathways: (1) enhanced nutrient remobilization and storage (stronger belowground sinks may increase the translocation of nutrients from leaves to storage organs, thereby accelerating senescence), and (2) altered root-shoot signalling and carbon status (changes in root activity, carbohydrate allocation and phytohormone balances can modify the timing of leaf ageing). Together, these processes can shift the balance toward earlier EOS in species-rich communities that invest more in belowground pools.

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed 448 grassland field samples collected across Northern China (2013–2015) and gridded datasets of global semi-arid grasslands, evaluating species diversity effects on EOS and its drivers. We first quantified the relationship between diversity and EOS. Next, we assessed allometric scaling relationships between ratio of belowground biomass (BGB):aboveground biomass (AGB) and species diversity. To further validate our findings, we applied piecewise structure equation model (piecewise SEM) and partial correlation to test the effect of diversity on EOS and its underlying mechanisms at regional and global scales.

Results

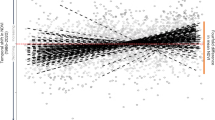

At both global and regional scales, we found a significant negative correlation between species diversity (characterized by species richness as the primary metric, see Method) and EOS. Specifically, EOS advanced 0.69 ± 0.24 days with per species increasing across a broad set of sample data from semi-arid grasslands across Northern China (Fig. 2a). We further tested whether the effect of species diversity on EOS varied among grassland, the results showed that no robust evidence that grassland type changes the effect of richness on EOS, yet differ in baseline EOS (Supplementary Table 1). The relationship between diversity and EOS was negative in 59.1% of Northern Hemisphere grasslands (Fig. 2b), consistent with results from sampled records in Northern China grasslands. Additionally, our partial correlation analysis also showed consistent negative correlations between species diversity and EOS after controlling for environmental factors (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The partial correlation coefficients were −0.17, −0.09, and −0.07 when climatic factors, soil factors, and both climatic and soil factors were controlled for, respectively.

Partial relationships derived from multiple linear mixed-effects models, with EOS (a), AGB (c), and BGB (e) as the dependent variables and species diversity as the independent variable, accounting for the random effects of grassland type. The blue lines depict the predicted mean values from the models, while the surrounding shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI). The hexagonal bins display the distribution of observed data points, adjusted for other covariates, with the color intensity indicating the density of data points. Global analysis of the relationship between EOS (b), AGB (d), and BGB (f) and species diversity using gridded data, with local regression coefficients indicated by the color of the points. The inset bar charts summarize the proportion of local regression coefficients that were positive or negative. The EOS represents the end of the growing season, BGB represents belowground biomass, and AGB represents aboveground biomass.

To deconstruct the mechanisms behind the increased BGB:AGB ratio, we firstly separately analyzed the relationship between species diversity and its individual components. We found that species richness was positively correlated with both AGB and BGB (Fig. 2c–f), consistent with the known biodiversity-productivity relationship. We further tested the hypothesis that greater plant diversity promotes relatively greater carbon allocation belowground (Fig. 3a–d). In our regional dataset from semi-arid grasslands in northern China, species diversity was significantly positive with the ratio of BGB:AGB (slope = 0.99, p < 0.01), indicating that more diverse communities allocate a larger fraction of biomass to roots. The pattern was also robust in both wet and dry condition (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). A broader synthesis across Northern Hemisphere grasslands shows the same pattern with 54.1% of relationships between positive diversity and BGB:AGB (Fig. 3a), consistent with the pattern found in Northern China.

Partial relationships derived from multiple linear mixed-effects models, with ratio of BGB:AGB as the dependent variable and species diversity as the independent variable (a), and EOS as the dependent variable and ratio of BGB:AGB as the independent variable (c), accounting for the random effects of grassland type. The blue lines depict the predicted mean values from the models, while the surrounding shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI). The hexagonal bins display the distribution of observed data points, adjusted for other covariates, with the color intensity indicating the density of data points. Global analysis of the relationship between ratio of BGB:AGB and species diversity (b), and EOS and ratio of BGB:AGB (d) using gridded data, with local regression coefficients indicated by the color of the points. The inset bar charts summarize the proportion of local regression coefficients that were positive or negative. The EOS represents the end of the growing season, BGB represents belowground biomass, and AGB represents aboveground biomass.

Biomass-dependent relationship with EOS were also found when considering species diversity effect, specifically, when separating species diversity from relationship between EOS and ratio of BGB:AGB in linear mixed models. When controlling for the effect of species diversity, EOS dates showed a significant negative correlation with ratio of BGB:AGB (slope = −0.23, p < 0.01, Fig. 3c). The negative relationship between EOS and ratio of BGB:AGB was also tested using partial correlation to exclude environmental factors (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The partial correlation coefficients were −0.23, −0.24 and −0.27 when climatic factors, soil factors, and both climatic and soil factors were controlled, respectively. Across Northern Hemisphere grassland areas, partial regression analysis indicated a negative relationship between EOS and ratio of BGB:AGB (across 61.7% of the area, Fig. 3d).

To test our hypothesis that biodiversity affected EOS may through carbon allocation, we conducted a piecewise structure equation model (piecewiseSEM). We calculated the direct effects of biodiversity on EOS in the piecewiseSEM and the indirect effects through different pathways. The results indicate a strong direct effect of biodiversity on EOS (standardized coefficients β = −0.24, p < 0.01, Fig. 4). In addition, ratio of BGB:AGB may be potential intermediaries between biodiversity and phenological responsiveness. This indirect effect of ratio of BGB:AGB was significantly mediated by soil bulk density and diversity (standardized coefficients β = 0.15 and 0.14, respectively, p < 0.01, Fig. 4). We found no significant direct or indirect effect of other soil properties on EOS. Overall, both the direct and the indirect pathways support the negative correlation between biodiversity and EOS.

Piecewise structural equation modeling (piecewiseSEM) using data from Northern China’s grasslands to explore the direct and indirect effects of species diversity on EOS. The variables and coefficients on the paths of the piecewiseSEM are standardized, negative and positive effects are indicated by red and blue lines, respectively, with solid lines signifying statistically significant relationships (p < 0.05) and dashed lines indicating non-significant relationships, as evaluated by chi-square tests. The EOS represents the end of the growing season, BGB represents belowground biomass, AGB represents aboveground biomass, C:N represents soil carbon-to-nitrogen, BD represents soil bulk density, SOC represents soil organic carbon, SM represents soil moisture, and ratio represents ratio of BGB:AGB. Model fit statistics are reported as χ2 = 8.7, p = 0.07; Fisher’s C = 13.535, p = 0.1; R2 = 0.17.

Discussion

While previous studies have focused mainly on the influence of species diversity on the timing of the growing season onset12, its effect on EOS remains overlooked. Using 448 grassland plots and remote sensing data, we demonstrate a robust negative relationship between species diversity and EOS across semi-grasslands, persisting even after accounting for climatic and edaphic variability (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, we observed species diversity significantly enhances ratio of BGB:AGB (Fig. 3a), which indicates preferential carbon allocation to belowground compartments. This asymmetry driven by increasing diversity indirectly accelerates senescence.

Our results corroborate well-established positive relationships between species diversity and plant biomass across diverse environmental conditions and broad geographic scales11,12,29 (Fig. 2c–f and Supplementary Fig. 1). Higher species diversity likely offers more opportunities for communities to occupy different environmental niches, leading to increased interspecific competition. The plants, especially in grasses, would adjust the opening of stomata to balance carbon acquisition and water demand under competition30. Consequently, grasses may allocate more nonstructural carbohydrates (glucose and starch) to root biomass rather than supporting AGB growth even in the presence of sufficient nutrient availability31,32. This community-wide shift in carbon allocation likely reflects changes in the expression or dominance of key belowground functional traits, such as root:shoot ratio and root turnover, driven by interspecific competition33. Importantly, however, individual-level allocation responses to water limitation differ from emergent community-level patterns. In arid environments, individual plants tends to invest heavily in roots to support water uptake and storage, a strategy driven by resource limitation rather34. This response of individual plants can generate high belowground biomass in low-diversity, water-stressed communities dominated by drought-tolerant species. By contrast, across broader climatic gradients where water and nutrients are not extremely limited, higher species richness promotes belowground carbon through niche complementarity and shifts in community composition35,36. We also observe an increasing BGB:AGB ratio with increasing species diversity in both dry and wet condition (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2), consistent with a relative shift toward greater belowground allocation in more diverse communities.

To ensure reproductive success under such an altered biomass allocation strategy37, grasses may show more rapid nutrient cycling and reabsorption38,39,40, ultimately leading to earlier EOS. Our structural equation models show a larger standardized direct effect of diversity and indirect effect of ratio of BGB:AGB on EOS, indicating that diversity-driven increases in BGB play a key mechanistic role in advancing EOS (Fig. 4). We further examined the negative relationship between diversity and EOS along the water conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3) and observed a stronger effect under wet conditions (Supplementary Table 4), which also support our conclusion that species diversity advancing autumn senescence.

While our study yields robust findings for semi-arid grasslands, their generality may be limited by biome-specific differences in water availability. The ecosystem functions of semi-arid grasslands, especially the underground carbon allocation strategies, may strongly constrained by water availability. In semi-arid systems, water limitation strongly constrains ecosystem functioning and belowground carbon allocation because plants tend to allocate more biomass to roots to acquire scarce water41, resulting in deeper rooting and larger belowground compartments. Consistent with our results, the negative relationship between diversity and EOS also differed between dry and wet conditions, which was stronger under wet conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). Although roots in the topsoil are especially responsive to environmental variation and biotic interactions, we evaluated whether restricting results of BGB to the 0–10 cm layer biased our conclusions. We found that 61.8% of roots were concentrated in the top 0–10 cm (Supplementary Fig. 5), and the ratio of BGB:AGB computed from 0-10 cm was highly correlated with that from 0 to 30 cm (R2 = 0.93, p < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 6). There was no statistical evidence that the effect of species richness on the ratio of BGB:AGB varied with soil depth (Supplementary Table 5). Together, these results indicate that confining BGB to the 0–10 cm layer did not bias our main findings for this semi-arid dataset. This suggests that the diversity-driven allocation signal is robust and likely mediated by functional traits operating within the dominant root zone, rather than being contingent on sampling the entire rooting profile. By contrast, in moister grassland systems, where water is more abundant, plants may allocate proportionally more biomass aboveground to maximize photosynthesis42, and phenological shifts are likely driven more by temperature or photoperiod than by water availability43,44. Therefore, the pathways through which species diversity affects autumn phenology may differ between dry and wet grasslands. Future research can be extended to a wider range of grassland types to explore the generality of the impact mechanism of diversity on phenology, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the response of global grassland ecosystems to climate change.

While our study primarily uses species richness as the main measure of diversity, other plant community diversity, such as evenness and species composition may also affect the carbon allocation strategy and phenological response. To address this potential issue, we tested the relationship between EOS and ratio of BGB:AGB with several species diversity indices, including species richness, the Shannon-Wiener index, Pielou’s evenness, and Simpson’s dominance index. The results showed that species richness was highly correlated with the Shannon-Wiener index (r > 0.7; Supplementary Fig. 7). Furthermore, we found no significant differences in the results of the regression models using either species richness or evenness as independent variables to explain the ratio of BGB:AGB and EOS (Supplementary Table 6). These findings indicate that within our study region, species richness is sufficient to capture the main effects of community diversity on autumn phenology.

Our integrated analysis synthesizing regional field measurements with global satellite observations demonstrates that plant species diversity accelerates EOS through carbon allocation-mediated regulation. The consistency of this pattern across spatial scales establishes species diversity as a critical regulator of grassland carbon cycling phenology, with implications for ecosystem responses to climate change. As climate change alters species diversity and ecosystem dynamics, understanding these linkages becomes critical for predicting grassland resilience. Our work establishes a novel framework linking species diversity, phenology, and resource allocation, emphasizing how asymmetric carbon partitioning may constrain growing seasons under future warming.

Methods

Sample sites

We conducted our study using data from 448 grassland sites surveyed between 2013 and 2015 by the Remote Sensing Investigation of Grassland Resource Degradation in Key Pastoral Areas of Temperate Grassland (2012FY111900) by The Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences45 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 7). All study sites fall within a semi-arid climatic region. The mean temperature and precipitation during the growing season were 17.10 °C and 40.47 mm, respectively. Elevations across the study site ranged from 300 to 1023 meters. The dominant plant species included Leymus chinensis, Stipa caucasica, Stipa grandis, Peganum harmala, Haplophyllum dauricum, Chamaerhodos erecta, Convolvulus ammannii, and Oxytropis racemosa.

Vegetation and soil parameters investigation

In each plot, three 1 × 1 m quadrats were established randomly during peak biomass (from late August to early September). Within each quadrat, we calculated the three widely used species diversity indices, including species richness (the total number of plant species in each plot), Shannon-Wiener diversity Index46, Simpson’s dominance index47, and Pielou’s Evenness Index48. The formulas are as followed:

where \({H}^{{\prime} }\) represents Shannon–Wiener diversity Index, D represents Simpson’s dominance index, \({J}^{{\prime} }\) represents Pielou’s Evenness Index. S represents the total number of species in the plot and \({p}_{i}\) represents relative cover of each species.

Although we calculated four diversity indices (species richness, Shannon-Wiener, Simpson’s, and Pielou’s Evenness), our preliminary analyses revealed that species richness was the most robust and interpretable predictor for the relationships under investigation (Supplementary Fig. 7). While the directional trends were generally consistent across different metrics, the statistical associations were strongest and most consistent for richness (Supplementary Table 6). Therefore, we selected species richness as the primary metric for all subsequent analyses and presentations in the main text. A detailed discussion comparing the responses of different diversity indices and the ecological rationale for focusing on richness is provided in the Discussion section.

All aboveground biomass within each quadrat was harvested, oven-dried at 65 °C to constant mass for 48 h and weighed49,50. For belowground sampling, we randomly collected three soil cores (7.5 cm diameter) at three depth increments (0–10, 10–20 and 20–30 cm) in each quadrat51. Cores from the same depth increment were measured at the plot level, resulting in nine core measurements per plot for each depth. Soil bulk density (BD) samples were collected with the same spatial replication and depth increments using steel cylinder with a core of 5 cm diameter and 5.1 cm height52.

Roots and gravel were separated from soil by gentle washing over a 2 mm sieve. After washing, roots were hand-picked and sorted. Living roots were distinguished from dead roots using visual and tactile criteria (color, elasticity, and cortical integrity). Roots were then placed into paper bags and oven-dried at 65 °C to constant mass before weighing to obtain belowground biomass (BGB) across per depth increment. Soil samples were air-dried, sieved to 2 mm and visible roots and stones were removed prior to analysis. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was determined by the Walkley-Black dichromate oxidation method following standard protocols53. Total soil carbon (TC) was measured by dry combustion using an elemental analyser (Elementar Vario EL III, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany) after grinding subsamples to a fine powder. Total soil nitrogen (TN) was measured by the micro-Kjeldahl method53. The soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N) was calculated on a mass basis as TC/TN. We posit that soil bulk density (BD), soil organic carbon (SOC) content, carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N), and soil moisture (SM) collectively characterize soil texture, nutrient status, and water availability. These critical factors influencing key plant functional processes and phenological events. Therefore, these variables (BD, C:N, SOC, and SM) were incorporated into our structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate how potential factors mediate EOS through their effects on carbon allocation strategy. The statistical summary in different grassland types is provided in Supplementary Table 7.

Global gridded datasets

We further validated our results at large scales using global gridded datasets of species richness, soil properties, and AGB and BGB. Vascular plant species richness was obtained from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) at 10 × 10 m plot size, predicted via machine learning using 140, 601 vegetation plots from 1885 to 201554,55. Soil data came from the International Soil Reference and Information Centre (ISRIC) World Soil Information Global Soil Properties database v2.0 at 250 m resolution, including soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, bulk density, and other properties estimated from 240,000 observations using quantile regression forests56,57. To match our study variables, we extracted data for soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and bulk density across Northern Hemisphere grasslands. AGB and BGB were obtained from Spawn et al. at 300 m resolution, which developed global grassland biomass map using a harmonization approach across many vegetation types58,59. Finally, we focused our analyses on these global gridded data layers (species richness, soil properties, and above- and belowground biomass) specific to Northern Hemisphere semi-arid grasslands according to a global grassland types map60. The map developed a broad definition of grassland as a distinct biotic and ecological unit, noting its similarity to savanna and distinguishing it from woodland and wetland. To focus on the semi-arid grassland, we only include the distribution of grassland which defined as warm semi-desert scrub and grassland, cool semi-desert scrub and grassland, temperate grassland, meadow and shrubland, boreal grassland, meadow and shrubland. This allowed validating our results at broad geographic extents.

Climate data

Gridded monthly climate data (temperature, precipitation, downward surface shortwave radiation (SRAD), SM, and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) were extracted from the TerraClimate dataset61,62. TerraClimate synthesizes high-resolution WorldClimate data with Climate Research Unit Time Series (CRU Ts4.0) and Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA55) outputs, providing additional meteorological variables and longer time series to match the period and variables used in the present study. The climate data were filtered to include only the growing season (May–September) from 2013 to 2015 to coincide with the sampling periods.

Phenology data

We estimated phenological transition dates for each sample site during the 2013–2015 sampling period using a previously developed vegetation index based on near-infrared reflectance (NIRv). This technique provides more accurate estimates of plant phenology than traditional indices like Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)63. The NIRv was derived from the 500 m, 16-day interval Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) MCD43A4 Version 6.1 reflectance product, which includes atmospherically corrected shortwave broadband albedo measurements64. Vegetation Index (VI)-pixel values were masked using a quality control band to exclude the effects of snow and clouds. The NIRv was defined as:

Where \({\rho }_{1}\) and \({\rho }_{2}\) represent bands of MODIS 1 (620-670 nm, Nadir_Reflectance_Band1) and MODIS 2 (841–876 nm, Nadir_Reflectance_Band2), respectively.

After calculating the NIRv vegetation index, we smoothed NIRv data using the weighted Whittaker with dynamic parameter λ in spatial (wWHd) method65 to reduce background noise. Based on the smoothed datasets, we extracted leaf phenology using a double logistic model, which is commonly used to fit a time series of data in when estimating phenology66,67. Compared with other approaches, such as splines and harmonic models, the double logistic model can better capture vegetation “green-up” and senescence phases using separate sigmoid curves. The model was defined as:

Where \({A}_{\max }\) and \({A}_{\min }\) are the maximum of VI and minimum VI, respectively, measured in each year. The parameters \({v}_{1}\) and \({d}_{1}\) represent the VI value and day of the year that the green-up phase begins, respectively. Finally, the parameters \({v}_{2}\) and \({d}_{2}\) represent the VI value and day of year the senescence phase began, respectively.

Statistics

The association between EOS that characterized autumn senescence and grassland species diversity was assessed using linear mixed regression models on IGSNRR sampled grassland data (Fig. 2a). To validate this relationship across Northern Hemisphere semi-arid grasslands, we tested the relationship between global gridded species richness and NIRv-based EOS datasets. Using the “focalReg” function in the terra package, we calculated multi-linear regression within a weighted moving focal window (defined as 9 units) to assess local associations between species diversity and EOS based on globally gridded datasets (Fig. 2b). Partial correlations between EOS and diversity or ration of BGB:AGB were also calculated after controlling for climatic (temperature, precipitation, SRAD and VPD) and soil (SOC, C:N, BD and SM) factors to ensure robust results (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition to the models for EOS and the BGB:AGB ratio, we also fitted separate linear mixed-effects models to test the direct effects of species richness on AGB and BGB (Fig. 2), including the same random effects (grassland type).

To assess whether restricting BGB to the top 0–10 cm would bias results, we conducted sensitivity analyses comparing (i) the proportion of top 0–10 cm root mass located in the total 0–30 cm (Supplementary Fig. 5), (ii) relationship between BGB:AGB ratios computed from 0–10 cm and 0–30 cm profile (Supplementary Fig. 6), and (iii) model comparison results along the root depth (Supplementary Table 5). We further tested the relationship between richness, carbon allocation (ration of BGB:AGB) and EOS is robustness under different water condition using mixed linear models (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4; Supplementary Table 2). The formula can be expressed as follows:

where \(y\) represents response variables such as EOS, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are fixed and random effects, respectively; \({x}_{0}\) is a vector of predict variables, \({x}_{1}\) is a vector of random intercepts, and \(\varepsilon\) is error of the estimate.

We used piecewise structural equation model to explore potential mechanism underlying the impact of biodiversity on EOS (Fig. 3). We hypothesized that the biodiversity affected EOS through carbon allocation strategy. To test this hypothesis, we developed a piecewiseSEM including ratio of BGB:AGB, SOC, C:N, BD and SM to test direct and indirect effects of diversity on EOS using the “piecewiseSEM” package68. PiecewiseSEM translates the path diagram into linear models, capturing main potential explanatory factors and allowing us to evaluate the main contribution of drivers. In our piecewiseSEM Model, we selected species richness as the metric of species diversity after evaluating multiple diversity indices (including the Shannon-Wiener index, Pielou’s evenness, and Simpson’s dominance index). To evaluate our model, we calculated various statistics and fit indices, including the Chi-Squared, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and R-squared. The standardized effects for each path were then calculated. As a complement to our piecewiseSEM approach, we performed the partial correlation analysis on the variables, controlling for the effects of climate factors such as temperature, precipitation, SRAD, and VPD.

All data analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.169.

Data availability

Both data are saved on https://github.com/bobilong/grassland-diversity.

Code availability

Both code are saved on https://github.com/bobilong/grassland-diversity.

References

Li, Y. et al. Local cooling and warming effects of forests based on satellite observations. Nat. Commun. 6, 6603 (2015).

Gu, H. et al. Warming-induced increase in carbon uptake is linked to earlier spring phenology in temperate and boreal forests. Nat. Commun. 13, 3698 (2022).

Kern, A., Marjanović, H. & Barcza, Z. Spring vegetation green-up dynamics in Central Europe based on 20-year long MODIS NDVI data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 287, 107969 (2020).

Piao, S. et al. Leaf onset in the northern hemisphere triggered by daytime temperature. Nat. Commun. 6, 6911 (2015).

Gill, A. L. et al. Changes in autumn senescence in northern hemisphere deciduous trees: a meta-analysis of autumn phenology studies. Ann. Bot. 116, 875–888 (2015).

Keskitalo, J., Bergquist, G., Gardeström, P. & Jansson, S. A cellular timetable of autumn senescence. Plant Physiol 139, 1635–1648 (2005).

Wu, C. et al. Increased drought effects on the phenology of autumn leaf senescence. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 943–949 (2022).

Zhang, G., Zhang, Y., Dong, J. & Xiao, X. Green-up dates in the Tibetan Plateau have continuously advanced from 1982 to 2011. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4309–4314 (2013).

Amico Roxas, A., Orozco, J., Guzmán-Delgado, P. & Zwieniecki, M. A. Spring phenology is affected by fall non-structural carbohydrate concentration and winter sugar redistribution in three Mediterranean nut tree species. Tree Physiol 41, 1425–1438 (2021).

Shen, P. et al. Biodiversity buffers the response of spring leaf unfolding to climate warming. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 863–868 (2024).

Johnson, K. H., Vogt, K. A., Clark, H. J., Schmitz, O. J. & Vogt, D. J. Biodiversity and the productivity and stability of ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 372–377 (1996).

Oehri, J., Schmid, B., Schaepman-Strub, G. & Niklaus, P. A. Biodiversity promotes primary productivity and growing season lengthening at the landscape scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10160–10165 (2017).

Wang, R. & Gamon, J. A. Remote sensing of terrestrial plant biodiversity. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111218 (2019).

Dronova, I., Taddeo, S. & Harris, K. Plant diversity reduces satellite-observed phenological variability in wetlands at a national scale. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl8214 (2022).

Xiong, T., Du, S., Zhang, H. & Zhang, X. Decreasing temperature sensitivity of spring phenology decelerates the advance of spring phenology in northern temperate and boreal forests. Ecol. Indic. 161, 111983 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Leaf senescence exhibits stronger climatic responses during warm than during cold autumns. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 777–780 (2020).

Zani, D., Crowther, T. W., Mo, L., Renner, S. S. & Zohner, C. M. Increased growing-season productivity drives earlier autumn leaf senescence in temperate trees. Science 370, 1066–1071 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Canopy structure regulates autumn phenology by mediating the microclimate in temperate forests. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1299–1305 (2024).

Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486, 59–67 (2012).

Loreau, M. et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. science 294, 804–808 (2001).

Reich, P. B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss escalate through time as redundancy fades. Science 336, 589–592 (2012).

Tilman, D. et al. Diversity and productivity in a long-term grassland experiment. Science 294, 843–845 (2001).

Tilman, D., Isbell, F. & Cowles, J. M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 471–493 (2014).

Ma, Z. & Chen, H. Y. H. Effects of species diversity on fine root productivity in diverse ecosystems: a global meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 25, 1387–1396 (2016).

Gracia, C. et al. Plant diversity loss has limited effects on below-ground biomass and traits but alters community short-term root production in a species-rich grassland. J. Ecol. 113, 662–671 (2025).

Bardgett, R. D. & van der Putten, W. H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515, 505–511 (2014).

Tejera-Nieves, M. et al. Seasonal decline in leaf photosynthesis in perennial switchgrass explained by sink limitations and water deficit. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 2022 (2023).

Kumar, R., Bishop, E., Bridges, W. C., Tharayil, N. & Sekhon, R. S. Sugar partitioning and source–sink interaction are key determinants of leaf senescence in maize. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 2597–2611 (2019).

Jochum, M. et al. The results of biodiversity–ecosystem functioning experiments are realistic. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1485–1494 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Interspecific competition alters water use patterns of coexisting plants in a desert ecosystem. Plant Soil 495, 583–599 (2024).

Podzikowski, L. Y., Heffernan, M. M. & Bever, J. D. Plant diversity and grasses increase root biomass in a rainfall and grassland diversity manipulation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 27 (2023).

Aerts, R., Boot, R. G. A. & van der Aart, P. J. M. The relation between above- and belowground biomass allocation patterns and competitive ability. Oecologia 87, 551–559 (1991).

Qi, Y., Wei, W., Chen, C. & Chen, L. Plant root-shoot biomass allocation over diverse biomes: a global synthesis. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 18, e00606 (2019).

Poorter, H. et al. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 193, 30–50 (2012).

Loreau, M. & Hector, A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72–76 (2001).

Fornara, D. A. & Tilman, D. Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation. J. Ecol. 96, 314–322 (2008).

Bazzaz, F. A., Chiariello, N. R., Coley, P. D. & Pitelka, L. F. Allocating resources to reproduction and defense. BioScience 37, 58–67 (1987).

Fridley, J. D. Extended leaf phenology and the autumn niche in deciduous forest invasions. Nature 485, 359–362 (2012).

Paul, M. J. & Foyer, C. H. Sink regulation of photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1383–1400 (2001).

Wang, Y. & Spalding, M. H. LCIB in the Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 121, 185–192 (2014).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Plant species richness and ecosystem multifunctionality in global drylands. Science 335, 214–218 (2012).

Kazanski, C. E. et al. Water availability modifies productivity response to biodiversity and nitrogen in long-term grassland experiments. Ecol. Appl. 31, e02363 (2021).

Bennie, J., Davies, T. W., Cruse, D., Bell, F. & Gaston, K. J. Artificial light at night alters grassland vegetation species composition and phenology. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 442–450 (2018).

Ojo, T. A., Kirkman, K. & Tedder, M. Effects of warming and rainfall variation on grass phenology and regenerative responses in mesic grassland. South Afr. J. Bot. 174, 107–115 (2024).

Qiao, Y. et al. Large-scale spatial patterns of grassland community properties in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, China. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 73, 560–568 (2020).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

SIMPSON, E. H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163, 688–688 (1949).

Pielou, E. C. Species-diversity and pattern-diversity in the study of ecological succession. J. Theor. Biol. 10, 370–383 (1966).

Castro, H. & Freitas, H. Above-ground biomass and productivity in the Montado: From herbaceous to shrub dominated communities. J. Arid Environ. 73, 506–511 (2009).

Zuo, X. et al. Observational and experimental evidence for the effect of altered precipitation on desert and steppe communities. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 21, e00864 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Above- and belowground biomass allocation and its regulation by plant density in six common grassland species in China. J. Plant Res. 135, 41–53 (2022).

Arnold, K. Methods of Soil Analysis. in Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods (American Society of Agronomy, 1986).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. in Methods of Soil Analysis 961–1010, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.3.c34 (1996).

Sabatini, F. M. et al. Global patterns of vascular plant alpha diversity. Nat. Commun. 13, 4683 (2022).

Sabatini, F. M. et al. Global patterns of vascular plant alpha-diversity [Dataset]. iDiv Data Repository https://doi.org/10.25829/idiv.3506-p4c0mo (2022).

Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil 7, 217–240 (2021).

Poggio, L. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty[Dataset]. SOIL https://files.isric.org/soilgrids/latest/ (2021).

Spawn, S. A., Sullivan, C. C., Lark, T. J. & Gibbs, H. K. Harmonized global maps of above and belowground biomass carbon density in the year 2010. Sci. Data 7, 112 (2020).

Spawn, S. A. & Gibbs, H. K. Global Aboveground and Belowground Biomass Carbon Density Maps for the Year 2010[Dataset]. ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1763 (2020).

Dixon, A. P., Faber-Langendoen, D., Josse, C., Morrison, J. & Loucks, C. J. Distribution mapping of world grassland types. J. Biogeogr. 41, 2003–2019 (2014).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J. & Lister, D. H. CRU TS4.00: Climatic Research Unit (CRU) Time-Series (TS) version 4.00 of high-resolution gridded data of month-by-month variation in climate[Dataset]. Climatic Research Unit https://doi.org/10.5285/edf8febfdaad48abb2cbaf7d7e846a86 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. NIRv and SIF better estimate phenology than NDVI and EVI: Effects of spring and autumn phenology on ecosystem production of planted forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 315, 108819 (2022).

Schaaf, C. & Wang, Z. MODIS/Terra+Aqua BRDF/Albedo Nadir BRDF Adjusted Ref Daily L3 Global − 500m V061 [Data set]. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD43A4.061 (2021).

Kong, D., Zhang, Y., Gu, X. & Wang, D. A robust method for reconstructing global MODIS EVI time series on the Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 155, 13–24 (2019).

Li, X. et al. A dataset of 30 m annual vegetation phenology indicators (1985–2015) in urban areas of the conterminous United States. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 881–894 (2019).

Wu, C. et al. Land surface phenology derived from normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) at global FLUXNET sites. Agric. For. Meteorol. 233, 171–182 (2017).

Lefcheck, J. S. piecewiseSEM: piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 573–579 (2016).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Zhaowen Wu and Heng Zhong for their work collecting our samples. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (32030006), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (Grant No. 2019QZKK0502), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA23100100) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. YJ201936, 2020SCUNL20, SCU2019D013, 2020SCUNL207, SCU2022D003, and lzujbky-2022-ey07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huan Cheng and Yuxin Qiao performed the data analysis. Huan Cheng, Yuxin Qiao, Constantin M. Zohner, and Jianquan Liu wrote the paper. Yuxin Qiao, Huaping Zhong, and HuaZhong Zhu sampled the plots. YunQiang Zhu, Qianru Jia, Yuchuan Yang, and Huaping Zhong contributed to the interpretation of the results. Constantin M. Zohner and Jianquan Liu designed the research. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Chunyan Long and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Somaparna Ghosh A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, H., Qiao, Y., Zhu, H. et al. Species diversity advances autumn senescence via enhanced belowground carbon allocation in semi-arid grasslands. Commun Earth Environ 7, 128 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03109-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03109-z