Abstract

Existing estimates of carbon sequestration by coastal vegetated ecosystems (e.g., kelp forests, seagrass meadows) remain highly uncertain because they utilize few measurements with high uncertainty or focus on individual stocks or fluxes. Here, we combine empirical data with modeling to generate detailed carbon budgets for kelp forests and eelgrass meadows in Nova Scotia, Canada. Our budgeting showed that the release and export of dissolved organic carbon accounts for substantially more carbon sequestered by these habitats than has been estimated globally (98.5 ± 64.6% for kelp and 84 ± 36.0% for eelgrass), suggesting this carbon pathway has been undervalued. Further, kelp forests are estimated to sequester more carbon than eelgrass by ~1.3 orders of magnitude (27 ± 19% and 12.1 ± 6.3% of annual net primary production for kelp and eelgrass) mainly due to their large habitat area, highlighting their significant but largely overlooked role in ocean carbon sequestration relative to other blue carbon ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coastal vegetated ecosystems (e.g. seagrass, salt marsh, mangroves, kelp forests) cycle and store carbon in our oceans, and are increasingly being recognized for their contribution to long-term carbon sequestration1,2,3. These ecosystems (i.e. blue carbon ecosystems, BCEs) are threatened by a variety of stressors, including climate change, fisheries, and coastal development, which can reduce their capacity to sequester carbon and release carbon stored in sediments, further exacerbating climate change4,5. The protection, restoration, and natural enhancement of these ecosystems have therefore been proposed to help limit further emissions and draw down additional carbon as a climate change mitigation tool6. Further, there is increasing interest in including coastal BCEs in national carbon inventories and voluntary carbon markets.

However, knowledge of the contribution of BCEs to long-term carbon sequestration is not well resolved largely because we lack basic data on carbon fluxes, stocks, and the links between fluxes and pools of stored carbon7,8. Existing estimates of the global contribution of kelp forests and seagrass beds to carbon sequestration are based on coarse compilations of studies from disparate geographic regions, species, and time periods, with some flux estimates relying on a limited number of studies leading to high uncertainty2,3. Moreover, many existing estimates focus on only a subset of fluxes7,9,10 or rely mainly on quantifying sediment carbon stocks11. Applying first-order global estimates on local and regional scales may be a good first approximation, but can lead to over- or underestimating the contribution of BCEs to carbon sequestration, which may misguide climate change mitigation efforts.

Detailed accounting of the fluxes and stocks of carbon within a given BCE kelp forest or seagrass system (i.e. a carbon budget) is now needed to reduce uncertainty in estimates of carbon sequestration, but such studies are scarce12,13,14. Considering a system as a whole provides a more accurate picture of the relative importance of different carbon pathways and may yield contrasting patterns to general paradigms. It can also provide insights into sources of variability that need to be characterized to improve overall estimates, and can be used to direct research towards the most critical parameters to resolve. Ultimately, this information provides insights into carbon pathways that may be most at risk from human activities, and inform how BCEs should be managed to maintain their capacity to cycle and store carbon in the long-term. Critically, this information supports a more robust appraisal of the potential for activities like BCE protection, enhancement, and restoration to help mitigate climate change7,10,15.

In this study we developed comprehensive carbon budgets for kelp forests (dominated by Saccharina latissima and Laminaria digitata) and eelgrass beds (Zostera marina) along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, Canada, representing two of the dominant BCEs in the region. The budget is developed using a synthesis of new and existing field measurements, lab and field experiments, and modeling. The results reduce uncertainty in regional estimate of carbon sequestration by these BCEs, allow for direct comparisons of carbon cycling between kelp and seagrass ecosystems, and demonstrate the broad utility of carbon budgeting for advancing blue carbon science.

Results

Carbon stocks and net primary production

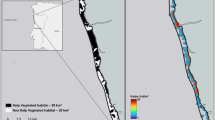

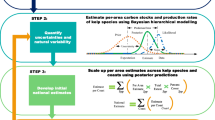

We estimate carbon stocks contained in sediments and living biomass and net primary production (NPP) rates for kelps and eelgrass using field measurements scaled to the region (study domain in Fig. 1A) using species distribution models16,17. Kelps are estimated to occupy nearly 6 times the area of eelgrass beds (1400 km2 vs. 240 km2) (Fig. 1B–D) and contain three orders of magnitude more living biomass, though this biomass does not constitute a long-term carbon sink (Fig. 2.1, 3.1)18,19. Eelgrass beds also contain stored carbon in the underlying sediments, comprised of locally fixed carbon (i.e. autochthonous, e.g. eelgrass leaves, roots, and rhizomes) and carbon imported from adjacent marine and terrestrial ecosystems (i.e. allochthonous). We estimate the regional carbon stock in eelgrass sediments in the top 100 cm at 1.77 ± 1.34 Tg C (all quantities are annual mean ± 1 SD), which exceeds carbon contained in living biomass by either species group (Figs. 1E, F and 3.2), though we note that a portion of this carbon is remineralized in the surface sediment layers. From literature carbon burial rates20 and source contributions to buried carbon19 we estimate that 0.55 ± 0.84% of eelgrass NPP (Eqn 1. see methods) (25% of the total carbon buried) (Fig. 3.3) and 0.23 ± 0.25% of kelp NPP (35.5% of total carbon buried) (Fig. 2.2) is buried within eelgrass beds on an annual basis19.

A Study domain delineated with a black line, including a large context map. B–D Maps of suitable habitat for the two dominant kelps (Laminaria digitata: orange area, Saccharina latissima: blue area)17 and the eelgrass Zostera marina (green area)16 along the Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia. E, F shows the carbon stock contained within living biomass and sediments within each suitable habitat area per m2 (E), and for the whole bioregion (F) and each blue carbon species (Laminaria digitata: orange area, Saccharina latissima: blue area, Zostera marina green area). G, H show bioregional net primary production estimates for each season and an annual total for each blue carbon species (Laminaria digitata: orange area, Saccharina latissima: blue area, Zostera marina green area) per m2 (G), and for the whole bioregion (H). Note, y axis scales vary across parameters to facilitate comparisons across species and seasons and the lower limit is constrained at 0. Data are means or totals ±1 standard deviation. All maps were created with ggplot2 and the marmap packages in R69,70.

Carbon budget totals for both kelp species (Saccharina latissima and Laminaria digitata), including the total amount (upper bound) of carbon estimated to be sequestered by kelp in the bioregion, estimated by summing quantities in the blue boxes only. Dashed lines indicate unknown quantities. Line weights indicate the relative flux through each pathway. DOC is dissolved organic carbon, POC is particulate organic carbon, L is labile, and R is refractory. Data are annual totals or means and the percent of annual NPP ± 1 standard deviation. The inset pie chart shows the relative contribution (as a percentage) of each carbon pathway towards the total carbon sequestration estimate by kelps, with colors representing different pathways (orange: burial within seagrass meadows, blue: burial in bare sediments, green: non-seagrass burial within seagrass meadows (NA for kelp), yellow: POC export, and dark blue: DOC export).

Carbon budget totals for the eelgrass Zostera marina, including the total amount (upper bound) of carbon estimated to be sequestered by eelgrass in the bioregion, estimated by summing quantities in the blue boxes only. Dashed lines indicate unknown quantities. Line weights indicate the relative flux through each pathway. DOC is dissolved organic carbon, POC is particulate organic carbon, L is labile, and R is refractory. Data are annual totals or means ±1 standard deviation. The inset pie chart shows the relative contribution (as a percentage) of each carbon pathway towards the total carbon sequestration estimate by eelgrass, with colors representing different pathways (orange: burial within seagrass meadows, blue: burial in bare sediments, green: non-seagrass burial within seagrass meadows, yellow: POC export, and dark blue: DOC export).

Kelp NPP (985 ± 516 g C m−2 y−1) is comparable to eelgrass NPP (465.17 ± 188.11 g C m−2 y−1) (Figs. 1G, H, 2.3 and 3.4) and both exceed that of phytoplankton on the Scotian Shelf per m2 (123 g C m−2 y−1)21. These quantities represent ~10% and 1% of total annual NPP for the shelf, respectively (phytoplankton NPP = 11.58 Tg C y−1 estimated using a study domain of 94,193 km2) (Fig. 1)21. Grazing accounts for a relatively small percent of NPP for both species groups (kelp: 0.7 ± 1.1%, eelgrass: 7.5 ± 4.2%) (Figs. 2.4 and 3.5)22,23.

Particulate organic carbon

A majority of kelp NPP is lost as particulate organic carbon (POC) through erosion from the distal ends of blades9,24, accounting for 53 ± 51% of NPP annually (Fig. 2.5). Kelp mortality through dislodgement also accounts for a significant source of POC25 (40 ± 32% of NPP, Fig. 2.6). POC production rates peak in summer when warm temperatures and storms cause senescence and loss22 (Fig. 4A, B). The majority of POC is labile or semi-labile26 (hereafter referred to as labile) (Fig. 2.7), with only ~14% of dislodged kelp stipe biomass (2.7% of total POC) estimated to be refractory after a year of degradation under aerobic conditions27 (1.1 ± 2.5% of kelp NPP, Figs. 2.8 and 4C).

Measures of particulate organic carbon (POC) production and export for L. digitata (orange), S. latissima (blue), and Z. marina (green), including refractory (R) and labile (L) components per season or year. A POC production per m2, B total POC production for the bioregion, C total RPOC production for the bioregion, D Bioregion export of POC to the shelf break (total LPOC and RPOC), E total deposition of RPOC in eelgrass beds on the shelf for the bioregion, and F total deposition of RPOC in muddy sediments for the bioregion. Note, y axis scales vary across parameters to facilitate comparisons across species and seasons and the lower limit is constrained at 0. Data are means ±1 standard deviation, with error bars for L. digitata in black, S. latissima in light green, and Z. marina in blue.

If POC is exported to deep water masses (>1000 m) or buried in soft sediments before it is remineralized, it is considered isolated from the atmosphere for climate-relevant time scales (100 years+)9. Kelp POC is negatively buoyant in our region, sinking quickly to the seabed and remaining in the nearshore (0% export to the shelf break) (Figs. 2.9, 2.10 and 4D)17. We estimate that 7.9 ± 2.5 % of kelp POC is transported to nearshore eelgrass beds, mainly in fall (Fig. 4E), amounting to a deposition rate of 0.051 ± 0.13% of NPP as refractory POC (RPOC) annually (Figs. 2.11 and 4E). This refractory portion accounts for about half as much kelp carbon we estimated to be buried per year in eelgrass beds (Fig. 2.2), indicating that some labile POC (LPOC) (Fig. 2.12) may be buried before remineralization. 27.9 ± 7.7 % of kelp POC is transported to bare muddy sediment in the nearshore and on the shelf17, totaling deposition rates of 0.16 ± 0.41% of NPP annually as RPOC (Figs. 2.13 and 4F) and 12 ± 9.4% of NPP as LPOC (Fig. 2.14). We consider our estimated deposition rates of RPOC on mud sediments on the shelf a conservative first-order estimate of the burial rate of this carbon (Fig. 2.15) (compared an estimated 0.9% of NPP in global carbon budgets)3. This quantity accounts for ~0.8% of carbon buried annually on the Scotian Shelf (0.741 Tg C year −1 for the 128,487 km2 domain)28. Kelp has been estimated to contribute 10–32% of the carbon stock in shelf sediments dating > 100 years old elsewhere, indicating that nearshore burial of kelp carbon can contribute to long-term carbon sequestration13,29.

The majority of eelgrass NPP is also released as POC in the form of dislodged or senescing leaves, with seasonal peaks in summer and fall (Figs. 3.6 and 4A, B). Eelgrass POC production rates are two orders of magnitude lower than those estimated for kelps in our region (Fig. 4A, B), though a greater percentage of eelgrass POC is estimated to be refractory (5.5%)30,31 accounting for 2.8 ± 1.4% of NPP (Figs. 3.7, 4C). The remaining POC is estimated to be labile (49 ± 24% of NPP, Fig. 3.8)27. We estimated 12.4 ± 12.2% of dislodged leaves to be transported to nearby eelgrass beds17, mainly in summer (Fig. 4E), amounting to 0.35 ± 0.29% of NPP deposited as RPOC (Fig. 3.9). This is lower than our estimated contribution of eelgrass to the carbon burial rate within beds (Fig. 3.3), indicating that burial of local or imported eelgrass LPOC (i.e., leaves) (Fig. 3.10), and/or roots and rhizomes that remain in situ also likely occurs. 21% ± 7.4 % of eelgrass POC is estimated to be deposited in muddy sediments in the nearshore and on the shelf, (Figs. 3.11, 3.12, and 4F). The refractory portion of this accounts for 0.08% of the total carbon buried on the shelf annually (Fig. 3.13)28.

In contrast to kelp POC, eelgrass leaves are buoyant for a period of about 3 weeks, depending on the water temperature, allowing them to disperse by winds and surface currents before they lose buoyancy during degradation32. Therefore, export rates of eelgrass POC are predicted to be higher than for kelps33, with ~2.1 ± 3.3% of floating eelgrass leaves estimated to reach the Scotian shelf break within the first few weeks following dislodgement (Fig. 4D)17. At this export rate, 0.34 ± 0.41% of NPP is exported as LPOC (Fig. 3.14) and 0.020 ± 0.024% of NPP is exported as RPOC (Figs. 3.15, 4D)17. Eelgrass leaves that lose buoyancy beyond the shelf break may sink to deep water, with some of this carbon likely remineralized during downward transport. Our estimates therefore represent the maximum potential POC sequestration through POC export to deep water (Fig. 2.09, 2.10 for kelp; Fig. 3.14, 3.15 for eelgrass). Summing this with POC burial in eelgrass beds and muddy sediments for each species group (Fig. 2.2, 2.15 and 3.3, 3.13) yields an estimated carbon sequestration by POC for kelp of 0.00462 ± 0.00530 and eelgrass of 0.00180 ± 0.000551 Tg C year −1, representing 0.40 ± 0.50 and 1.6 ± 0.8% of NPP, respectively (Fig. 5A).

Measures of the maximum potential amount of carbon sequestered for L. digitata (orange), S. latissima (blue), and Z. marina (green) as A particulate organic carbon (POC per season or year), calculated as the sum of labile (L) and refractory (R) POC export, and RPOC deposited in mud and eelgrass beds, B dissolved organic carbon (DOC) produced from live plants per season or year, calculated as the sum of labile (L) DOC export and total refractory (R) DOC production. C DOC produced from degrading POC per season or year (sum of LDOC export and total RDOC). Note, y axis scales vary across parameters to facilitate comparisons across species and seasons and the lower limit is constrained at 0. Data are means ±1 standard deviation, with error bars for L. digitata in black, S. latissima in light green, and Z. marina in blue.

Dissolved organic carbon

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is released directly by live kelps and eelgrass during primary production, fragmentation, senescence, and during POC degradation34,35. We measured DOC production in incubation chambers in situ, and found comparable DOC production rates between kelps (64.0 ± 34.5 g C m−2 y−1) and eelgrass (61.9 ± 27.0 g C m−2 y−1) per m2 (Fig. 6A) and on a regional scale (Figs. 2.16, 2.17, 3.16, 3.17 and 6B). This DOC production accounts for 6.6 ± 5.1 % and 13.3 ± 7.9% of NPP for kelp and eelgrass, respectively, although DOC production did not follow seasonal trends in NPP (Figs. 2.16, 2.17, 3.16, 3.17 and 6A, B). Previous studies have found that 35.5% of kelp DOC36 and 40 % of eelgrass DOC37,38 is refractory, resisting degradation for at least one year. Using these estimates, the production of refractory DOC (RDOC) accounts for 2.5 ± 1.9% (Figs. 2.16, 6C) and 4.6 ± 3.1% (Figs. 3.16, 6C) of NPP for kelp and eelgrass. Only a few studies have measured DOC release during POC degradation, estimating that on average 59% and 25% of carbon in POC is released as DOC for kelp and eelgrass within the first two weeks38,39 Using these percentages, we estimate that the release of DOC from POC degradation is a more significant carbon pathway than the release of DOC from attached, growing plants, accounting for 54 ± 42% (Figs. 2.18, 2.19 and 6D) and 12.8 ± 6.3% (Figs. 3.18, 3.19 and 6D) of annual NPP in kelps and eelgrass, respectively, 35.5% and 40% of which is assumed to be refractory (Figs. 2.18, 3.18).

Measures of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) production and export for L. digitata (orange), S. latissima (blue) and Z. marina (green) per season or year, including A DOC production per m2 from live plants, B total DOC production from live plants for the bioregion, C total refractory (R) DOC production from live plants for the bioregion, D total DOC released from POC degradation for the bioregion, E total bioregion export to the shelf break of labile (L) DOC released from live plants, and F total bioregion export to the shelf break of LDOC released from POC degradation. Note, y axis scales vary across parameters to facilitate comparisons across species and seasons and the lower limit is constrained at 0. Data are means ±1 standard deviation, with error bars for L. digitata in black, S. latissima in light green, and Z. marina in blue.

Export of neutrally buoyant DOC is rapid and extensive, with 33.6 ± 19.9% of kelp DOC and 12.0 ± 9.5% of eelgrass DOC being exported to the shelf break within 90 days of release17. We modeled degradation of the labile portion of DOC (LDOC) during export using decay functions in the literature36,40, and merged these with export rates to estimate that 0.055 ± 0.042% of kelp NPP (Figs. 2.20, 6E) and 0.37 ± 0.29% of eelgrass NPP (Figs. 3.20, 6E) is exported to the shelf break as LDOC annually (remineralization in Figs. 2.21, 3.21). The export of LDOC from POC degradation is estimated to account for 3.3 ± 2.0% of NPP for kelp (Fig. 2.22) and 0.065 ± 0.0050% of NPP in eelgrass (Fig. 3.22) (remineralization in Figs. 2.23, 3.23 and 6F). During lateral transport and once this LDOC reaches the shelf break, it has the potential to reach deeper water through downward advection, adsorption and sinking34. Our estimates of LDOC export represent a maximum upper bound of this form of carbon potentially sequestered through deep ocean export from our region.

Using export rates17 and coastal residence times predicted for our region, we expect all RDOC to be advected from coastal waters in our domain to the open ocean in 181–365 days41, indicating that all this carbon is likely exported beyond the 200 m isobath within the time frame over which its persistence has been measured (~6 months)36,38 where it may then be transported to deeper waters and isolated from the atmosphere for climate-relevant time scales. Our estimates of total flux through this pathway therefore represent an upper bound of carbon sequestration via this mechanism (Figs. 2.16, 2.18 and 3.16, 3.18). Total potential sequestration through the formation of RDOC (Figs. 2.20, 2.22 and 3.20, 3.22) and export of LDOC before remineralization (2.17, 2.19, 3.16, 3.18) is 0.308 ± 0.143 Tg C y−1 and 0.011 ± 0.0032 Tg C y−1 for kelp and eelgrass, respectively, representing 26 ± 19% and 10.2 ± 5.0% of NPP (Fig. 5B, C). For kelp, DOC sequestration from POC degradation (Fig. 5C) is an order of magnitude greater than from live plant production of DOC (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

The value of kelp forests and eelgrass beds to carbon sequestration

Summing RDOC from live kelp and degrading POC (Fig. 2.16, 2.18), with the export of LDOC, LPOC, and RPOC to the shelf break (Fig. 2.24), and with the RPOC deposition/burial in soft sediments on the shelf (Fig. 2.2, 2.15) yields a total potential sequestration from kelp forests in our domain of 0.313 ± 0.144 Tg C y−1, accounting for 27 ± 19% of annual NPP (Fig. 2.25). For eelgrass, our calculation also incorporates non-kelp allochthonous carbon burial within eelgrass beds (Fig. 3.3, 3.13, 3.16, 3.18, 3.24, quantity in Fig. 3.25 minus quantity in Fig. 2.2), yielding a total sequestration rate of 0.014 ± 0.004 Tg C y−1, accounting for 12.1 ± 6.3% of NPP (Fig. 3.26). On a per unit area basis, kelp carbon sequestration (124.0 ± 57.1 g C m−2 year−1) is slightly higher but largely comparable to that of eelgrass (56.5 ± 18.5 g C m−2 year−1 for eelgrass) (Fig. 2.25, 3.26). The higher contribution of kelp to carbon sequestration in our region relative to eelgrass is therefore mainly due to the greater predicted habitat area occupied in the study domain is.

Implications

Macroalgal forests have been undervalued relative to other BCEs for their potential contribution to ocean carbon sequestration due to their inability to trap and bury carbon locally, and their inclusion as BCEs remains controversial1,3,14,42. Our study estimates a higher contribution of kelp to ocean carbon sequestration then eelgrass in our region by ~1.3 orders of magnitude, supporting a growing body of knowledge showing relatively high contributions of kelp forests to carbon sequestration compared to other BCEs13,43,44. DOC accounts for the majority of carbon sequestered by kelp forests in Nova Scotia, representing a higher percentage than has been estimated for kelp forests globally (98.5 ± 60.1% of the total carbon sequestered vs. 64% globally)3. This is partially because we include the conversion from kelp POC to DOC in our budget39, which has not been considered previously in estimates of macroalgal carbon sequestration3,13 but may account for a significant flux of carbon to global oceanic DOC pools. We also estimate that POC export and burial accounts for very little stored carbon in Nova Scotia relative to other regions (1.6 ± 1.8 % of total carbon sequestered vs 31% globally)3,9,45 mainly due to a lack of hydrodynamic mechanisms for transporting this carbon to deep offshore sediments17.

By contrast, relatively more carbon is sequestered by eelgrass beds in our region through the burial of allochthonous and autochthonous POC within meadows and on soft sediments on the shelf (13.2 ± 0.44% of total carbon sequestered)19. However, DOC production emerged as the primary sequestration pathway for eelgrass in our region and a more significant flux of carbon to oceanic DOC pools than has been documented elsewhere (84.0 ± 36.0% of total carbon sequestered vs 10.6% globally)2. The conversion from POC to DOC has also not been included in previous estimates of seagrass sequestration, and existing global estimates were generated using measurements from different seagrass species than occur in our region and because generalized DOC remineralization rates for macroalgae were applied to seagrass estimates2.

Discrepancies between our regional carbon budgets and existing global budgets are therefore due to a combination of natural spatial and intraspecific variability within and amongst regions and remaining uncertainties in some carbon pathways (e.g. DOC, carbon burial rates). Further, discrepancies can be explained by inadequate parameterization on a global scale. This shows show how applying generalized estimates to individual regions can lead to inaccuracies in carbon accounting and that focusing on single carbon pathways can distort the relative value of BCEs for carbon sequestration. The relatively high importance of DOC in our carbon budget indicates that further research quantifying the production, transformation, and long-term persistence of DOC from BCEs is urgently needed to improve estimates of the contribution of coastal macrophytes to ocean carbon sequestration, and that solely focusing on POC burial and export will underestimate sequestration. Further, carbon emissions from BCEs have gone largely uncharacterized, and sparse measurements and methodological limitations have precluded accurate estimates of shelf burial rates of BCE carbon, particularly for macroalgae46. Broadly, our result show how carbon accounting can highlight undervalued carbon pathways, reduce uncertainty in existing global estimates of carbon sequestration, and support more robust carbon accounting and strategies for the management of BCEs.

Methods

Study design

The study domain encompassed the mainland Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia, ranging from Cape Sable Island (43.38959, −65.62084) in the southwest and Cape Canso in the Northeast (45.344620, −60.909754) to the edge of the Scotian Shelf break (Fig. 1A). Carbon budgets were generated for the three dominant macrophyte species in the region, Zostera marina, Laminaria digitata, and Saccharina latissima47. Estimates are a compilation and reanalysis of new and existing experimental and observational data from our domain. When using previous studies, priority was given to studies from our region and species, where possible, but in some cases we used data from the same species or genera from different regions. Budget estimates are given as seasonal or annual means, representing quantities ±1 SD per m2 or bioregion (defined as the study domain) basis. Uncertainties were propagated through mathematical operations using standard statistical methods48. Where estimates are presented as % of NPP, values are calculated as in Eqn 1.

Uncertainties are propagated as ±1 SD. Details of how each carbon stock and flux were calculated are below. Note, we have not included emissions of greenhouse gasses (e.g. methane, halocarbons) in our budgets due to a lack of data.

Carbon stocks

Estimates of carbon stocks contained in living biomass and sediments were generated for kelps (living biomass only) and eelgrass using modeled suitable habitat area thresholded to a binary presence/absence (1421 km2 for S. latissima, 1101 km2 for L. digitata, and 240 km2 for Z. marina)16,17 combined with field measurements of carbon stocks per unit area. For S. latissima and L. digitata, biomass and density data were measured using quadrat sampling by SCUBA divers spanning all seasons at 13 sites within the study domain from 2021–2023 (Supplementary Table 1). At each site, divers sampled 6–8, 0.75 m2 quadrats along 1–2 depth strata (3–5 m, 7–9 m). Divers counted the density of kelp stipes (one stipe represents one individual) and then all kelps were collected and placed in a mesh bag. Kelp species were separated and weighed (wet weight, ww) at the surface using a fish scale (±0.01 kg). For carbon stock calculations, kelp biomass (kg ww) and density (ind m−2) data were averaged across all sites and depths, and converted to measures of carbon content per unit area (kg C m−2) using a wet weight to dry weight (dw) conversion factor for each species22 and a dw to carbon conversion factor of 0.349.

For Z. marina, above and below ground biomass data were collected at four sites within the study domain50, including a deep (3.2 m) and shallow (1.8 m) site at two of the four sampled sites (Supplementary Table 2). Above and below ground biomass was estimated using 6 hand cores (10.8 cm diameter) at each site. Both biomass components were summed for each core, converted to an estimate of biomass per m2, converted to carbon using a conversion factor of 0.3651, and then averaged across sites. Sediment carbon content within beds of Z. marina was calculated using data from52, and summed with above and below ground biomass to generate a per m2 estimate of carbon stock contained within live biomass and sediments (top 100 cm) within eelgrass beds. Note, not all of this carbon represents a long-term carbon sink. For eelgrass and kelp, these per m2 measurements were then multiplied by the suitable habitat area for each species in the region to estimate total regional carbon stock within each habitat.

Net primary production (NPP)

Estimates of net primary production were generated from field growth rate measurements of S. latissima and L. digitata using the hole punch method for each species at 7 sites during all four seasons (Supplementary Table 3)22. The data set includes field growth measurements taken in 2008–200922, supplemented with new field data collected using the same methods at two additional sites (Sober Island and Broad Cove) in 2022–2023. In short, blade growth was measured by punching a hole at the base of the kelp blade (n = 10–20 individuals per species) near the meristem, and measuring the distance the hole moved over a period of 2-4 weeks. This distance is converted to a measure of new tissue production (g dw) by excising the blade section after the growth period, drying the tissue at 60 °C for 24–48 hours, and then weighing the tissue. The amount of new tissue produced per day was then calculated by dividing the g dw of the tissue section by the time elapsed, and then converting this to an estimate of carbon production per individual (g C d−1) using a conversion factor of 0.349. Individual growth measurements were then averaged across replicates and scaled to g C m−2 d−1 estimate by multiplying this number by the density of each kelp species as collected in diver quadrats (see above). This rate was converted to a seasonal or annual total by multiplying it by the number of days in each season, and then summing it across the time period. The annual growth for each species was then multiplied by the area of suitable habitat in the domain17 to generate an annual estimate for the entire region. The hole punch method is known to underestimate NPP because this method only accounts for carbon allocated to plant growth53, so growth estimates measured in this study were scaled to NPP using conversion factors measured previously for kelp in our region (2.22, growth = 44% of NPP)54.

For eelgrass, NPP (above and below ground production) was measured in the field at two representative sites in May 2023–2024 using the plastochrone growth method55. Shoot production according to the plastochrone method is based on the measurement of mature plant parts (either above or belowground) and the plastochrone interval55,56 For each sampling period, 20-30 eelgrass shoots at each site were marked with a hole through the middle of the sheath and collected 3-9 weeks later depending on the season. After collection, the number of new leaves since marking (i.e., leaves with no mark) were determined and then used to calculate the plastochrone interval (PI, number of days to produce a new leaf). The leaf PI was assumed equivalent for rhizomes (belowground tissue), given that eelgrass is a mono-meristematic leaf-replacing species that produces a new rhizome internode and node for every new leaf56. To determine aboveground production (g C shoot−1 d−1), the length (mm) of the youngest mature leaf (leaf three) was measured and converted to biomass (g dry mass) then carbon (g C)57, then divided by the PI. Rhizome production (g C shoot−1 d−1) was determined as the dry mass of the rhizome internode between nodes 3 and 4 converted to g C, and divided by the PI. Evidence shows that for eelgrass (Z. marina), the third leaf and the fourth rhizome internode (extending between nodes 3 and 4) are consistently fully expanded and therefore represent mature aboveground and belowground plant parts, respectively56. Finally, net shoot production was determined by summing the corresponding measures of aboveground and belowground production for each shoot. To scale individual shoot growth to growth per unit area (g C m−2 d−1), mean shoot growth (g C shoot−1 d−1) was multiplied by the mean shoot density (number of shoots m−2, n = 3–5 quadrats per site) (Supplementary Table 2). Finally, growth (g C m−2 d−1) was then averaged across the 2 sites, multiplied by the number of days in each season, and then summed for each season and the whole year. The seasonal and annual values for each species was then multiplied by the area of suitable habitat in the domain16 to generate estimates for the entire region. Field growth measures were scaled to NPP using a conversion factor as done for kelp (1.64, growth = 61% of NPP) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

POC production and export

POC production as blade erosion from kelps (i.e. senescence and breakage of blade material from the distal tip) was measured on the same individuals as for the field growth measurements in 2022–2023, and again utilizing previously collected data and methodologies from 2008 to 2009 (Supplementary Table 3)22. Total blade length was measured at the start and end of the measurement period, and the difference in blade length, accounting for growth, is considered the amount of blade material lost to the distal erosion of tissues. The length of this section was converted to carbon by generating a g/cm conversion factor from a section of blade tissue of known length that is excised, dried, and weighed. This is then multiplied by the length of tissue eroded, and then converted to carbon using the conversion factor of 0.349. Individual erosion rate (g C d−1) was then calculated by dividing the amount of eroded tissue by the time elapsed between measurements. Individual measurements were then averaged across replicates and converted to a per m2 and per region estimate using the same method as for growth.

POC production from the mortality of whole kelp individuals (Supplementary Table 5) was measured by marking 10–20 individual kelps of each species with a numbered cable tie at Broad Cove and Sober Island at monthly intervals, and then tracking the survival of each individual between measurement periods. For the data from 2008 to 200922, we used the number of tagged individuals missing between the start and end of the growth measurement periods to estimate loss. The proportion of missing individuals was calculated for each month as a monthly mortality rate (including an estimated 25% relocation error rate) and averaged across months for each season. This mortality rate was corrected to account for only the losses relating to a single year of production by multiplying loss rates by the proportion of individuals in a single cohort estimated to be lost within a year (77% for S latissima 50% for L. digitata)58. This mortality rate was then multiplied by a per individual average biomass (calculated by dividing quadrat biomass by density) to generate a per m2 estimate of POC production through mortality. This was then converted to g C49 to generate a carbon loss rate in g C season−1 per m2, and multiplied by suitable habitat area for each species to generate an estimate for the whole region. We note that density estimates used to calculate POC production from erosion were corrected with mortality rate to avoid overestimating POC production. POC production from erosion and dislodgement were then summed to generate an estimate of total seasonal and annual POC production for each kelp species.

We calculated the amount of this POC that is refractory (RPOC) as 14% of the stipe biomass27, assuming that all blade material is degraded within 12 months given aerobic conditions on the Scotian Shelf59. We calculated stipe biomass using stipe to blade ratios recorded previously for Saccharina latissima and Laminaria digitata60,61 multiplied by biomass lost through plant mortality and corrected to 14%. The remaining POC is assumed to be labile (LPOC).

POC production from senescing and dislodged eelgrass leaves was estimated for each growth sampling interval as the difference between plant aboveground production (described above) (g dw m−2) and the change in aboveground standing biomass (g dw m−2) (Supplementary Table 4)62. Aboveground standing biomass (g dw m−2) is estimated by multiplying shoot density (number of shoots m−2) by the average aboveground biomass per shoot (specific to site)57. POC production estimates were converted to g C using a conversion factor of 0.34, summed across season to generate a carbon loss rate (g C season−1 m−2), and multiplied by suitable habitat area to generate an estimate for the whole region. 5.5% of this POC is assumed to be refractory30.

The amount of POC exported to the shelf break was then calculated for each species by multiplying % POC particle export rates for each season17 by the seasonal LPOC and RPOC production estimates for the bioregion, and then summing these quantities across seasons to generate an annual total POC export estimate in g C region year−1. We note that degradation times at the bottom temperatures experienced in our region would result in negligible losses of biomass over the 90-day export period modeled, so we do not account for degradation in our carbon export estimates17. We also generated estimates of the amount of carbon exported to eelgrass beds and muddy sediments in the nearshore and on the shelf. This was calculated by multiplying seasonal % export estimates (Supplementary Table 6)17 by RPOC and LPOC production, then summing across seasons. We estimated the amount of carbon originating from Z. marina, S. latissima and L. digitata that is buried in eelgrass beds using carbon burial rates (g C m−2 y−1) measured for Z. marina beds20 multiplied by the proportion of sediment carbon that is Z. marina or macroalgae in origin19. Allochthonous carbon burial in eelgrass beds is accounted for in our budget as the total estimated carbon burial rate minus the burial of carbon originating from Z. marina. Sufficient data to estimate the amount of POC from Z. marina, S. latissima, and L. digitata buried in non-vegetated shelf sediments do not exist for our region, but we consider our estimates of RPOC deposition on muddy sediments as a first order estimate of the burial rate of this carbon. All quantities were then multiplied by the area of the bioregion to yield a regional total. The amount of LPOC and RPOC originating from kelp and Z. marina not deposited on muddy sediments or eelgrass beds was assumed to be remineralized.

DOC production and export

DOC production was measured for L. digitata, S. latissima, and Z. marina in situ using incubation experiments conducted in the spring, summer, and fall (winter experiments were not conducted due to logistical limitations) following methodologies used in previous studies63,64,65. Whole eelgrass (including leaves, rhizomes and roots) and kelp (including blades and holdfasts) individuals were collected at two sites each for both species groups. Plants chosen for the incubations were clear of visible epiphytes and epifauna, and were in good condition (i.e. little visible damage and/or degradation of tissues). Plants were collected the week prior to each experimental period to allow for wound healing from collections and stored in ambient seawater until incubations began. DOC production was then measured by containing whole plants in clear plastic bags (16 L) anchored to a lead line on the substratum (25 m in length, plants separated by 50 cm) at 4 m depth. The experimental design consisted of 5 replicates of each species from 2 sites each (n = 10 for each species), and 10 controls (n = 40 total replicates) during each experimental run (except summer where 4 replicates per site, 8 controls, and only 1 eelgrass site were included). Eelgrass individuals were bundled into groups of 10 plants (5 plants in summer) within experimental bags, as DOC production from one individual was expected to be too low to detect relative to the volume of the bag.

For each experimental run, eelgrass, kelp or a bare tag (experimental control) was randomly added inside each bag and the bags were filled with surrounding water (9.0 ± 2.2 L; mean ± 1 SD, Fig. 2) and sealed. In addition to the controls affixed to the lead line, we also collected 5 control bags filled from the surrounding waters at the start and end each deployment. These controls were brought to shore immediately for chemical analysis. DOC production was assessed during 1 daytime period and 1 nighttime period during each experimental run. The deployment duration varied between seasons depending on daylength and time for sunrise and sunset. The night deployment was done during the entire dark phase, with experimental bags deployed within an hour after sunset and retrieved within an hour before sunrise (duration range: 11–14.5 hours). The day deployment was shorter and aimed to be within the peak daylight 10–2 pm (duration range: 4–7 hours). Upon retrieval of the nighttime experiment, bags were returned to shore and kept in the dark before processing (1.5 hours max). Bags were weighed using a digital scale (©Berkley, precision 10 g), and then dissolved oxygen (DO; YSI ODO), temperature and salinity (YSI Pro 30) were measured inside each bag (except for the summer when the YSI ODO was not used). Samples were immediately filtered using a peristaltic pump maintained below 10 psi with 0.45 micron nitrocellulose mixed ester membrane filters. Samples were poisoned with concentrated HgCl2 upon return to the lab and kept at 4 °C until analysis. For one replicate of each treatment and control type, we also measured DO using the Winkler method66. The same kelp and eelgrass individuals were used for the night and daytime experimental runs, and were kept in a cooler on ice between deployments. Within 24 hours of the end of the experiment, we measured the wet weight of each plant and tags before drying the them in a drying oven (60 °C) for 48 hours and measuring their dry weight (DW).

The quantity of DOC produced was measured with a OI Analytical Aurora 1030 W TOC analyzer with a model 1080 autosampler and a combustion unit. Briefly, dried gas from sparged acidified samples was detected using infrared gas analysis with an analytical precision of 0.4 ppm or better (Jan Veizer Stable Isotope Laboratory, University of Ottawa). DOC concentrations (mg C L−1) were then converted to production/consumption rates (mg C L−1 h−1) by first subtracting the start concentration for each deployment, and dividing this amount by the experimental duration. This amount was then multiplied by the volume per bag to create a measure of DOC production per hour (mg C h−1). To account for the biological activity of the surrounding seawater in the treatment bags, the mean DOC production/consumption rate in the control bags was then subtracted from the DOC production/consumption rate of each experimental bag. The DOC production/consumption hourly rate per individual (mg C ind−1 h−1) was then calculated by dividing the DOC production/consumption hourly rate (mg C h−1) by the number of individuals in each bag (eelgrass only).

To estimate the daily DOC production/consumption rates per m2, we extracted information on the total duration in hours above light saturation allowing for photosynthesis (HSat) for kelp and eelgrass for each day in each season assuming the following conditions (depth eelgrass = 1 m, depth kelp = 5 m, attenuation coefficient = 0.33, saturation irradiance (Ik) Ik eelgrass = 100 umol photons m−2 s−167, Ik kelp = 38 umol photons m−2 s−167 at a central geographical location for the south shore of Nova Scotia (latitude: 44.4° N) following Wong & Dowd68. The hourly DOC production/consumption rate per individual (mg C ind−1 h−1) was then converted to a daily rate for each day of the season by multiplying the daytime DOC production/consumption rate by HSat, and then adding this quantity to the product of nighttime DOC production/consumption rate and 24—Hsat (i.e. hours under saturating irradiance) (Supplementary Table 7). Summer data were missing at nighttime due to logistical limitations, therefore we used a 10% decrease of daytime DOC production/consumption rate per biomass to estimate the nighttime value (nighttime DOC production was 10% lower than daytime production during other seasons). We did not run an experiment in winter, so we applied DOC production/consumption rates for spring with winter daily HSat values to calculate winter DOC production. We assume winter is most similar to spring in terms of DOC production given that growth exceeds senescence in both seasons, whereas the opposite is true in summer and fall22. Daily DOC production values per gram dw were multiplied by the per individual biomass in each bag and then multiplied by the density of plants at each site50, and then summed to generate a total DOC production rate for each season (Supplementary Table 7). These quantities were then summed across seasons to generate an annual rate (g C m−2 y−1), and multiplied by the area of suitable habitat for each species to generate an estimate of DOC production for the bioregion.

The amount of DOC in refractory form was then estimated by multiplying each seasonal and annual quantity by the estimated amount of this carbon that is refractory after microbial remineralization, as measured from prior studies: 37.5% for kelp36, and 40% for eelgrass35,37 over a period of 1–6 months. The difference between the total DOC production and the RDOC quantity was considered the labile fraction (LDOC). The amount of DOC released during kelp and eelgrass POC degradation was estimated by multiplying the quantity of LPOC produced during each season by the percent of this carbon released as DOC within the first two weeks of degradation, as measured by experimental studies (59% for kelp39 and 25% for eelgrass38). 37.5% and 40% were used, as above, to convert this DOC quantity to RDOC for kelp and eelgrass, respectively. To quantify export of the LDOC fractions released from live and decaying individuals, we modeled decay of LPOC quantities using an exponential relationship and decay constants found in the literature: k = −0.06 day−1 for kelp36 and −0.01 day−1 for eelgrass37,40. Daily estimates of the % of particles (i.e., carbon) reaching the shelf break17 were then multiplied by the quantity of LDOC remaining on each day to estimate the amount of this DOC exported at each time step. This quantity was then subtracted from the amount available for decay and export during the following time step. The total amount of LDOC exported to the shelf break during each season was then calculated by summing this quantity across the 90 days of the season, and then across seasons for an annual total. Using coastal residence times and export modeling by Krumhansl et al.17 predicted for our region, we expect all RDOC to be advected from coastal waters in our domain to the open ocean in 181–365 days41, indicating that all this carbon is likely exported beyond the 200 m isobath within the time frame over which its persistence has been measured (1 year)36,38.

Data availability

All data are available as supplementary material and at: https://github.com/kirakrumhansl/Carbon-Budget-Code.

Code availability

All code and associated raw data are available at: https://github.com/kirakrumhansl/Carbon-Budget-Code.

References

Nellemann, C. et al. (eds) Blue Carbon: A Rapid Response Assessment (United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal, 2009).

Duarte, C. M. & Krause-Jensen, D. Export from seagrass meadows contributes to marine carbon sequestration. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 13 (2017).

Krause-Jensen, D. & Duarte, C. M. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nat. Geosci. 9, 737–742 (2016).

Trevathan-Tackett, S. M. et al. Effects of small-scale, shading-induced seagrass loss on blue carbon storage: Implications for management of degraded seagrass ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 1351–1359 (2018).

Blain, C. O., Hansen, S. C. & Shears, N. T. Coastal darkening substantially limits the contribution of kelp to coastal carbon cycles. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5547–5563 (2021).

Drever, R. C. et al. Natural climate solutions for Canada. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6034 (2021).

Pessarrodona, A. et al. Carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation using macroalgae: a state of knowledge review. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 98, 1945–1971 (2023).

Macreadie, P. I. et al. The future of Blue Carbon science. Nat. Commun. 10, 3998 (2019).

Filbee-Dexter, K. et al. Carbon export from seaweed forests to deep ocean sinks. Nat. Geosci. 17, 552–559 (2024).

Serrano, O. et al. Australian vegetated coastal ecosystems as global hotspots for climate change mitigation. Nat. Commun. 10, 4313 (2019).

Reynolds, L. K. et al. Ecosystem services returned through seagrass restoration. Restor. Ecol. 24, 583–588 (2016).

Huang, Y. H. et al. Carbon budgets of multispecies seagrass beds at Dongsha Island in the South China Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 106, 92–102 (2015).

Frigstad, H. et al. Blue Carbon – Climate Adaptation, $CO_2$ Uptake and Sequestration of Carbon in Nordic Blue Forests (NIVA Report 7448-2020, Norwegian Institute for Water Research, 2020).

Watanabe, K. et al. Macroalgal metabolism and lateral carbon flows can create significant carbon sinks. Biogeosciences 17, 2425–2440 (2020).

Macreadie, P. I. et al. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 826–839 (2021).

O’Brien, J. M., Wong, M. C. & Stanley, R. R. E. Fine-scale ensemble species distribution modeling of eelgrass (Zostera marina) to inform nearshore conservation planning and habitat management. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 988858 (2022).

Krumhansl, K. A. et al. Pathways of blue carbon export from kelp and seagrass beds along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia. Sci. Adv. 11, eadw1952 (2025).

Fourqurean, J. W. et al. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat. Geosci. 5, 505–509 (2012).

Röhr, M. E. et al. Blue carbon storage capacity of temperate Eelgrass (Zostera marina) Meadows. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 1457–1475 (2018).

Novak, A. B. et al. Factors influencing carbon stocks and accumulation rates in eelgrass meadows across New England, USA. Estuaries Coasts 43, 2076–2091 (2020).

Song, H. et al. Interannual variability in phytoplankton blooms and plankton productivity over the Nova Scotian Shelf and in the Gulf of Maine. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 426, 105–118 (2011).

Krumhansl, K. A. & Scheibling, R. E. Detrital production in Nova Scotian kelp beds: patterns and processes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 421, 67–82 (2011).

Nienhuis, P. H. & Groenendijk, A. M. Consumption of eelgrass (Zostera marina) by birds and invertebrates: an annual budget. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 29, 29–35 (1986).

Krumhansl, K. A. & Scheibling, R. E. Production and fate of kelp detritus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 467, 281–302 (2012).

Filbee-Dexter, K. & Scheibling, R. E. Hurricane-mediated defoliation of kelp beds and pulsed delivery of kelp detritus to offshore sedimentary habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 455, 51–64 (2012).

Hansell, D. A. & Carlson, C. A. (eds) Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter (Academic Press, 2002).

Pedersen, M. F. et al. Carbon sequestration potential increased by incomplete anaerobic decomposition of kelp detritus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 660, 53–67 (2021).

Silverberg, N. et al. Remineralization of organic carbon in eastern Canadian continental margin sediments. Deep-Sea Res. II 47, 699–731 (2000).

Ortega, A. et al. Connected macroalgal–sediment systems: blue carbon and food webs in the deep coastal ocean. Ecol. Monogr. 89, e01366 (2019).

Kuwae, T. & Hori, M. (eds) Blue Carbon in Shallow Coastal Ecosystems: Carbon Dynamics, Policy, and Implementation (Springer Nature, 2019).

Trevathan-Tackett, S. M. et al. Long-term decomposition captures key steps in microbial breakdown of seagrass litter. Sci. Total Environ. 705, 135806 (2020).

Weatherall, E. J. et al. Quantifying the dispersal potential of seagrass vegetative fragments: a comparison of multiple subtropical species. Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 169, 207–215 (2016).

Chang, Y. E. et al. Lateral carbon export of macroalgae and seagrass from diverse habitats contributes particulate organic carbon in the deep sea of the Northern South China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 206, 116672 (2024).

Paine, E. R. et al. Rate and fate of dissolved organic carbon release by seaweeds: a missing link in the coastal ocean carbon cycle. J. Phycol. 57, 1375–1391 (2021).

Pellikaan, G. C. & Nienhuis, P. H. Nutrient uptake and release during growth and decomposition of eelgrass, Zostera marina L., and its effects on the nutrient dynamics of Lake Grevelingen. Aquat. Bot. 30, 189–214 (1988).

Gao, Y. et al. Dissolved organic carbon from cultured kelp Saccharina japonica: production, bioavailability, and bacterial degradation rates. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 13, 101–110 (2021).

Egea, L. G. et al. Marine heatwaves and disease alter community metabolism and DOC fluxes on a widespread habitat-forming seagrass species (Zostera marina). Sci. Total Environ. 957, 177820 (2024).

Pellikaan, G. C. Laboratory Experiments on Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) Decomposition. Neth. J. Sea Res. 18, 360–383 (1984).

Perkins, A. K. et al. Production of dissolved carbon and alkalinity during macroalgal wrack degradation on beaches: a mesocosm experiment with implications for blue carbon. Biogeochemistry 160, 159–175 (2022).

Godshalk, G. L. & Wetzel, R. G. Decomposition of aquatic angiosperms. III. Zostera marina and a conceptual model of decomposition. Aquat. Bot. 5, 329–354 (1978).

Liu, X. et al. Simulating water residence time in the coastal ocean: a global perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 13910–13919 (2019).

Hill, R. et al. Can macroalgae contribute to blue carbon? An Australian perspective. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1689–1706 (2015).

Filbee-Dexter, K. & Wernberg, T. Substantial blue carbon in overlooked Australian kelp forests. Sci. Rep. 10, 12341 (2020).

Franco, J. N. et al. Potential blue carbon in the fringe of Southern European Kelp forests. Sci. Rep. 15, 29573 (2025).

van der Mheen, M. et al. Substantial kelp detritus exported beyond the continental shelf by dense shelf water transport. Sci. Rep. 14, 839 (2024).

Johannessen, S. C. How to quantify blue carbon sequestration rates in seagrass meadow sediment: geochemical method and troubleshooting. Carbon Footprints 2, 5 (2023).

Krumhansl, K. A. et al. Loss, resilience and recovery of kelp forests in a region of rapid ocean warming. Ann. Bot. 133, 73–92 (2024).

Andraos, J. On the propagation of statistical errors for a function of several variables. J. Chem. Educ. 73, 150–154 (1996).

Mann, K. H. Ecological Energetics of the seaweed zone in a marine bay on the Atlantic Coast of Canada. I. Zonation and biomass of seaweeds. Mar. Biol. 12, 1–10 (1972).

Wong, M. C. & M. Dowd. The role of short-term temperature variability and light in shaping the phenology and characteristics of seagrass beds. Ecosphere 14, e4461 (2023).

Postlethwaite, V. R. et al. Low blue carbon storage in eelgrass (Zostera marina) meadows on the Pacific Coast of Canada. PLoS One 13, e0198348 (2018).

Christensen, M. S. Estimating blue carbon storage capacity of Canada’s eelgrass beds. MSc thesis, Univ. British Columbia (2023).

Pessarrodona, A. et al. A global dataset of seaweed net primary productivity. Sci. Data 9, 484 (2022).

Hatcher, B. G. & Chapman, A. R. O. & Mann, K.H. An Annual Carbon Budget for the Kelp Laminaria longicruris. Mar. Biol. 44, 85–96 (1977).

Gaeckle, J. L. & Short, F. T. A plastochrone method for measuring leaf growth in Eelgrass, Zostera marina. Bull. Mar. Sci. 71, 1237–1246 (2002).

Short, F. T. & Duarte, C. M. Methods for the measurement of seagrass growth and production. In Global Seagrass Research Methods (eds Short, F. T. & Coles, R. G.) 155–182 (Elsevier Science, 2001).

Thomson, J. A., Vercaemer, B. & Wong, M. C. Non-destructive biomass estimation for eelgrass (Zostera marina): Allometric and percent cover–biomass relationships vary with environmental conditions. Aquat. Bot. 198, 103833 (2025).

Chapman, A. R. O. Reproduction, recruitment, and mortality in two species of Laminaria in southwest Nova Scotia. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 78, 99–109 (1984).

Hebert, D. et al. Physical Oceanographic Conditions on the Scotian Shelf and in the Gulf of Maine during 2023. Can. Tech. Rep. Hydrogr. Ocean Sci. 380, 71 (2024).

Grebe, G. S. et al. The effect of distal-end trimming onSaccharina latissimamorphology, composition, and productivity. J. World Aquac. Soc. 52, 1081–1098 (2021).

Ronowicz, M., Kukliński, P. & Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M. Morphological variation of kelps (Alaria esculenta, cf. Laminaria digitata, and Saccharina latissima) in an Arctic glacial fjord. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 268, 107801 (2022).

Romero, J. et al. The detritic compartment in a posidonia oceanica meadow: litter features, decomposition rates, and mineral stocks. Mar. Ecol. 13, 69–83 (2008).

Reed, D. C. et al. Patterns and controls of reef-scale production of dissolved organic carbon by giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1996–2008 (2015).

Weigel, B. L. & Pfister, C. A. The dynamics and stoichiometry of dissolved organic carbon release by kelp. Ecology 102, e03221 (2021).

Jimenez-Ramos, R. et al. Carbon metabolism and bioavailability of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) fluxes in seagrass communities are altered under the presence of the tropical invasive alga Halimeda incrassata. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 156325 (2022).

Jones, E., Zemlyak, F. & Stewart, P. Operating manual for the Bedford Institute of Oceanography Automated Dissolved Oxygen Titration System (Can. Tech. Rep. Hydrogr. Ocean Sci. 138, 1992).

Lee, K., Park, S. & Kim, Y. Effects of irradiance, temperature, and nutrients on growth dynamics of seagrasses: a review. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 350, 144–175 (2007).

Wong, M. C. & Dowd, M. Eelgrass (Zostera marina) trait variation across varying temperature–light regimes. Estuaries Coasts 48, 15 (2025).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Pante, E., Simon-Bouhet, B._marmap: import, plot and analyze bathymetric and topographic data. CRAN https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.marmap (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Katie Thistle, Shawn Roach, Thomas Baker, Cody Brooks, Danielle Davenport, Claudio DiBacco, Katherine Lee, Jordan Thomson, Benedikte Vercaemer, Chris Corriveau, and Nick Jeffery for their support in the field. We also thank Wendy Gentleman for early input and feedback on the work. KK discloses support for this work from a Fisheries and Oceans Canada Competitive Science Research Fund grant to KK and KA-S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K. was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing & editing. M.W. was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing & editing. M.P. was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing & editing. M.F. was involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, software, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing & editing. C.–E.G. Gabriel was involved in investigation, methodology, writing—reviewing & editing. Y.W. was involved in Methodology and writing—reviewing & editing. K.A.-S. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—reviewing & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Richard Zimmerman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Nezha Mejjad and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krumhansl, K.A., Wong, M.C., Picard, M.M.M. et al. Blue carbon sequestration dominated by dissolved organic carbon pathways for kelp forests and eelgrass meadows in Nova Scotia, Canada. Commun Earth Environ 7, 98 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03122-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03122-2