Abstract

Slope lineae are enigmatic, bright, and seemingly young features on Mercury. Past investigations hypothesized that lineae occurrence might be tied to volatile loss, analogous to hollows, but no systematic analysis has been conducted. Here, we use a deep learning-driven approach to map 402 slope lineae across the planet. Lineae seem to feature blue spectral slopes and tend to originate from hollows or bright, ‘hollow-like’ features located on the equator-facing walls of young impact craters that penetrated volcanic smooth plains, implying that lineae activity could be driven by heat loss, insolation, and the devolatilization of subsurface phases like sulfur. We do not observe any geomorphic lineae activity between 2011 and 2015, suggesting that activity occurs on timescales longer than ~4 years or below MESSENGER’s spatial resolution. Lineae activity as a geomorphic indicator of recent or ongoing volatile loss on Mercury represents a specific hypothesis that can be scrutinized by ESA/JAXA BepiColombo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Slope lineae—also called bright streaks, slope streaks, or streamers—are bright, elongated features on Mercury’s slopes that were first observed in some of the high-resolution images returned by the MESSENGER spacecraft (Mercury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging1) between 2011 and 2015 (Fig. 1, e.g. refs. 2,3,4). Initially described by ref. 5. in conference proceedings, slope lineae are considered one of the youngest geologic features on the surface of Mercury, along with the so-called hollows, haloed, rimless, bright depressions (e.g., refs. 3, 6, 7). More recently8, (conference proceedings) documented several lineae across the planet. Those preliminary surveys suggested potential, qualitative relations between lineae, the abundance of subsurface volatiles, and smooth plains. Despite those previous efforts, no robust, systematic, quantitative analysis of the abundance, distribution, and geostatistical properties of slope lineae has been conducted to date, and no public catalog is available to guide future science investigations and data acquisition efforts. Because of their importance as potential indicators of geologically-recent or ongoing volatile loss on Mercury, slope lineae have been identified as one of the key science targets of the SIMBIO-SYS instrument suite (Spectrometer and Imaging for MPO BepiColombo Integrated Observatory SYStem) onboard the ESA/JAXA (European Space Agency, Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency) BepiColombo spacecraft that is expected to initiate its nominal science phase in late 20264,9.

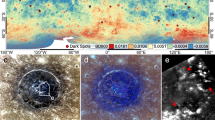

Lineae and hollow/’hollow-like’ source regions identified in MDIS NAC and WAC (Mercury Dual Imaging System Narrow/Wide Angle Camera10) images in Degas crater (a–c, 37.1°N, 127.3°W), Martins crater (d), and another unnamed location (e). a shows a WAC composite of R (430/997 nm), G (430 nm), B (997 nm). a–b Lineae and hollows (Hn, dashed orange & Ln, solid orange) show a similar blue spectral slope, in contrast to the overall background’s (Bn, black) red slope; one background sample (B3) is located outside of the area shown in (a), south of Degas crater. Spectra are G-band normalized mean values derived from 3 × 3 pixel windows; standard deviation indicated by gray bars. Downslope direction indicated by white arrows where appropriate. Image credits: NASA/JHUAPL/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Here, we conduct a systematic, deep learning-driven, global survey of slope lineae across Mercury to (a) characterize the distribution as well as the morphometric and spectral properties of slope lineae before the arrival of BepiColombo, and (b) use a combination of geostatistical as well as change detection approaches to investigate whether lineae are still active today—and whether they might be tied to ongoing volatile loss on Mercury.

Results

Slope lineae distribution, characteristics, and geostatistics

Our detector identifies 925 (expert-reviewed) slope lineae between 84°N and 40°S. Due to MDIS’ (Mercury Dual Imaging System10) repeat coverage in some locations, these detections include duplicates; after de-duplication, a total of 402 unique, individual slope lineae remain all across Mercury. The two main geographic lineae clusters (‘hotspots’) are located in Budh Planitia and Sobkou Planitia (Fig. 2a). Other geographic hotspots are located in Lugus, Caloris, Sihtu, Mercair, Aparangi, and Otaared Planitia, as well as on the Santa Maria, Unity, and Calypso Rupes. The highest spatial density of lineae is observed in Degas crater. The vast majority of lineae has been identified in the northern hemisphere ( ~ 93%) (Fig. 2a). We note a distinct relation between the number of identified lineae and the pixel scale of the available MDIS NAC images, where smaller pixel scales enhance the number of lineae detections, particularly pronounced in Sobkou Planitia and on the Unity Rupes (cf. Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig.1).

a distribution of all identified slope lineae (white arrows, n = 402), heatmap in the background. Slope lineae marker azimuth represents the azimuth of the respective linea. Locations of hollows identified by ref. 14. are indicated (black crosses, n = 19,110); hillshaded topographic map and smooth plains distribution (red-shaded38) in the background. Hot poles are indicated by white dots. MDIS image coverage (n = 112,424) is indicated by histograms on the sides of the map. Distribution of lineae (orange) as a function of (b) topographic elevation, (c) slope angle, and (d) slope aspect, in relation to a sample of 500 randomly-placed points on the surface (‘background’, black); random points limited to 65°N to 35°S. Distribution of lineae inside vs outside of (e) craters larger than 20 km15, (f) smooth plains38, and (g) LRM39, in comparison to hollows14 and the background; box-and-whisker plot in (e) shows the distribution of the lineae host crater diameters ( ~ 90% of the overall identified lineae population).

The identified lineae are between hundreds of meters and several kilometers long and visually resemble the morphology of slope features previously identified on other planets and moons, such as slope streaks and recurring slope lineae on Mars (e.g., refs. 11, 12) and granular flows on the Moon (e.g., ref. 13). The vertical thickness of lineae deposits is unknown. We do not observe any indications of shadows around lineae deposits in the highest-resolution MDIS NAC images (4 images better than 5 m pixel scale, covering 6 lineae), suggesting thicknesses of less than ~7 to ~17 m, considering the respective slope and solar incidence angles. We do not observe any distinctly dim lineae across the planet, potentially indicating an overall lack of old or inactive lineae, but note several lineae that show potential indications of stacking and a possible sequence of linea generations (e.g., Fig. 3c).

On average, lineae are located at slightly lower topographic elevations than the global average (‘background’, Fig. 2b, statistically significant, P < 0.001, t-test), but not as low as hollows (per14), potentially because of their position on crater walls, above hollows that tend to be located on crater floors. Lineae are located on steeper than average slopes (statistically significant, P < 0.001, t-test) and have been identified on inclines as steep as ~35° (Fig. 2c). We note that the used measure of slope is affected by the pixel scale of the available topographic data (665 m/pixel, Supplementary Fig. 2), which is larger than the scale of the individual linea, suggesting that lineae are in fact located on steeper slopes than reported here, on average.

About ~72% of lineae are located in impact craters included in ref.15. ’s global crater catalog with diameters larger than 20 km (Fig. 2e), similar to hollows (per14). A manual check of each linea detection in MDIS data shows that in fact ~90% of all lineae are located in craters, many of which are too small to be considered by the ref. 15 catalog. Overall, the craters that host lineae are relatively young, with a median diameter of ~10 km (Fig. 2e), slightly below the transition between simple and complex craters (per16,17). The small population of lineae that are not located in craters are either hosted by volcanic vents or other topographic features such as mounds and ridges (Fig. 3). When considering crater degradation stages for craters larger than 40 km in diameter18, the number of lineae per host crater is ~2.86 for the youngest craters (class 5), ~0.17 for class 4, ~0.09 for class 3, ~0.02 for class 2, and ~0.18 for the oldest craters (class 1), underlining that lineae are geologically young features.

The vast majority of the identified lineae originate from the very top of the local slope, such as the inner upper rim of impact craters. Lineae source regions are mostly unresolved, but ~87% of all lineae seem to originate from young, bright hollows (‘type 1’, per3) or – predominantly—from small, bright, seemingly ‘hollow-like’ features located along crater rims and other topographic ridges (Figs. 1, 3). We choose the term ‘hollow-like’ because these features appear to resemble sub-MDIS resolution (type 1) hollows, due to their brightness and co-location with resolved hollows (e.g. Fig. 1). About ~8% of lineae appear to originate from spur-and-gully morphologies; we note that spur-and-gully and hollow-like source regions occur simultaneously in some locations, as previously noted by8. The remaining ~5% of source regions remain un-classified; they might be un-resolved or inactive – and less bright – hollows (‘type 2’ or ‘type 3’, per3, Fig. 3b) or could be related to impact events (Fig. 3a, c).

On a global scale, lineae distribution is loosely correlated with the distribution of larger-scale hollow and hollow field-bearing regions as mapped by preceding surveys, which is most pronounced in Budh Planitia (Fig. 2a). However, we note numerous larger-scale hollow-bearing regions without lineae detections (Fig. 3d). We point out that almost all of the hollow-like features that seem to resemble the majority of lineae source regions are too small to be recognized by past manual and automated surveys (e.g. Fig. 1c, d) – and that the lack of high-resolution images might impede the detection of lineae in many hollow-bearing regions (e.g. Fig. 3d), which might explain the (apparently) weak geographic correlation of lineae and larger-scale hollow (field) locations. Multispectral MDIS WAC data that spatially resolve lineae are scarce, but we identify coverage ( ~ 185 m pixel scale) in Degas crater (Fig. 1b). The extracted spectra show (a) a distinct spectral similarity between lineae and hollows, (b) a distinct difference between lineae, hollows, and the background terrain, in particular beyond ~700 nm, and (c) a clear blue spectral slope for lineae.

Globally, lineae tend to be located on equator-facing slopes, with a distinct peak at ~180° (i.e., south-facing, for a largely northern hemisphere-based lineae population). This peak is more pronounced than expressed by hollows and distinct from the background (Fig. 2d). The data also imply a possible relative absence of lineae on east- and, in particular, west-facing slopes. Importantly, the pixel scale of the used auxiliary products (665 m) does not fully capture the geomorphology of smaller craters (<~10 km across), which host the majority of lineae (Supplementary Fig. 2); a manual verification of the actual position of lineae in MDIS NAC images shows that the aspect provided by the global topographic data can be offset by up to 180° in extreme cases, particularly for regions with low slope gradients. We conduct an ablation study and analyze four separate slope aspect distributions that only consider slope aspect values derived for slopes steeper than 5°, 10°, 15°, and 20° - and find that the south-facing peak remains distinct in all of those histograms. South-facing lineae occur all across Mercury, but most distinctively in Degas crater, which hosts ~39 south-facing lineae ( ~ 10% of the overall population). When omitting all Degas lineae from the analysis, the global south-facing trend remains distinct, however. This shows that Degas’ lineae population has an effect on the reported global statistics but is not the only cause of the south-facing peak shown in Fig. 2d.

The Budh and Caloris Planitia lineae clusters are in the proximity of the 180°E hot pole, while other major clusters are located in the proximity of the 0°E hot pole, such as the Santa Maria Rupes, Sihtu, and Otaared Planitia clusters. The largest lineae cluster in Sobkou Planitia is located on the perimeter of the 180°E hot pole. There exist other clusters that are not in the proximity of any of the hot poles, however, such as in Lugus Planitia and on the Unity and Calypso Rupes (Fig. 1a). We note that slope lineae aspect (‘azimuth’)—if insolation-driven—should be predominantly equator-facing but could extend to hot pole-facing in the vicinity of the hot poles, although our data do not seem to show any hot pole-facing trends (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Interestingly, slope lineae are located on terrain that reaches slightly higher (modelled) bi-annual maximum surface temperatures and (modelled) bi-annual thermal surface amplitudes than the background (with a median of 643 K vs 633 K and 542 K vs 531 K, respectively, Figs. 4a, d, 5). These differences are faint, with statistical significance derived by a t-test (P = 0.01, P = 0.01, respectively), but no statistical significance derived by a Mann–Whitney u-test (P = 0.09, P = 0.06, respectively). Similarly, lineae are located in regions that experience slightly higher (modelled) bi-annual maximum temperatures and (modelled) bi-annual thermal amplitudes at 1 m depth (with a median of 251 K vs 247 K and 55 K vs 48 K, respectively), but not at 2 m depth (with a median of 205 K vs 205 K and 6 K vs 6 K, respectively). The temperature distribution shifts at 1 m depth are not statistically significant, but approach statistical significance, particularly the maximum temperature (P = 0.07, P = 0.12, respectively, u-test). We note that the lower-temperature tail of the lineae distribution (Figs. 4a,d,5a,c) can be attributed to high-latitude lineae in the Unity Rupes cluster that is located beyond ~50°N. Interestingly, the majority of the high-latitude, lower-temperature lineae are south- and hot pole-facing (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 4). We note that our analysis of lineae azimuth and their relation with the thermal environment are dominated by the two geographically constrained lineae hotspots in Budh and Sobkou Planitia, the globally heterogeneous MDIS coverage (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the low spatial resolution of the available topographic ( ~ 665 m pixel scale) and model-derived thermophysical data ( ~ 2660 m pixel scale, Supplementary Fig. 2), which limits the overall validity of this analysis.

Distribution of lineae (orange) as a function of (modelled) bi-annual maximum temperature at the surface (a), 1 m depth (b), and 2 m depth (c), as well as (modelled) bi-annual thermal amplitude at the surface (d), 1 m depth (e), and 2 m depth (f), in relation to a sample of 500 randomly-placed points on the surface (‘background’, black); random points limited to 65°N to 35°S; here, thermal amplitude describes the temperature difference between bi-annual maximum and minimum surface temperature (based on40); p values of (two-sample) t-tests and (two-tailed Mann–Whitney) u-tests indicated; shifts of the lineae distribution median value to warmer temperatures is indicated by orange triangles, where present.

Relation between modelled maximum surface temperature and slope lineae (a) and random point latitude (b); relation between modelled thermal amplitude and slope lineae (c) and random point longitude (d); random points limited to 65°N to 35°S. Equator and hot pole longitudes are indicated by vertical dashed lines centered at latitude 0°N and longitudes 0°E and 180°E, respectively. Modelled thermal data based on40.

About ~59% of all lineae (along with their host craters) are located in smooth plains, which is a substantially larger fraction than previously observed for hollows ( ~ 42%14) (Fig. 2f). The tendency of lineae to predominantly occur in volcanic terrain seems to resemble the tendency of lunar granular flows that are largely tied to young impact craters in volcanic mare regions19. About 10% of all identified slope lineae are directly located in LRM (Fig. 2g), which is a factor ~1.5 more than was observed for hollows, but this may be a consequence of the low spatial resolution of the current LRM product (cf.14). We do not observe a qualitative correlation between lineae distribution and the modelled average impact flux as represented by a modelled diurnal average ejecta mass production rate20.

Lineae clusters are not systematically co-located with surface-exposed tectonic features (including presumably recently active lobate scarps21), although there is partial overlap in specific regions such as in the northern Calypso and Unity Rupes and parts of Caloris Planitia (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, many of the major lineae clusters are not co-located with tectonic features, and, similarly, the main clusters of tectonic features (e.g., Borealis and Caloris Planitia) do not overlap with an increased number of lineae. This observation is not fully conclusive due to an overall lack of high-resolution image coverage (particularly in the southern hemisphere, Supplementary Fig. 1) but seems to imply that tectonic seismicity (‘mercuryquakes’) is not a globally pronounced driver of slope lineae formation.

We identify a small number of lineae that are hosted by volcanic vents, but do not observe a general, geographic relation between lineae and vent distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6). Some lineae clusters overlap with vent locations, such as in the Aparangi, southern Caloris, and Sihtu Planitia clusters, but all major lineae clusters are not in the proximity of volcanic vents. Similarly, we do not observe any spatial relation between lineae locations and new impact craters that formed during MESSENGER operations22 (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that small-scale impact events are unlikely to be a main driver of lineae formation.

We perform a manual change detection analysis of 46 locations that feature more than two lineae detections in two different MDIS NAC images (with varying temporal differences and a maximum temporal difference of ~4 years) to (a) identify potential geomorphic modifications of existing lineae and (b) detect newly-formed lineae, but do not identify any such change. The complete lack of observable geomorphic change implies that lineae activity happens on timescales longer than ~4 years and/or is not resolved by MDIS NAC’s spatial resolution, i.e., occurs on spatial scales below ~10 m (i.e., two NAC high-resolution image pixels).

Our slope lineae catalog is openly available here: https://doi.org/10.48620/92770.

Discussion

Our geographic, geomorphic, and geostatistical analysis presents several arguments for devolatilization-driven lineae activity: (1) lineae seem to resemble a blue spectral slope, very similar to hollows (Fig. 1), (2) lineae largely source from hollows and hollow-like features (Fig. 1,3), (3) lineae are mostly hosted by young, small impact craters, i.e., in a geologic context that provides topographic gradients and potentially enables access to a subsurface volatile reservoir, as hypothesized for hollows (Fig. 2), (4) lineae tend to be located on equator-facing slopes (Fig. 2), (5) lineae tend to cluster in terrain with slightly higher (modelled) bi-annual peak temperatures at the surface and at 1-m depth (Figs. 4, 5), and (6) lineae appear to occur on eroded slopes well below the angle of repose of dry regolith (Figs. 2c,3b), supporting the presence of a fluidizing agent like volatiles. These observations suggest that lineae formation could be tied to devolatilization and, potentially, to insolation, but are substantially limited by the spatial resolution and quality of the available topographic (665 m pixel scale) and thermal data (2660 m pixel scale), which is likely insufficient to represent the thermophysical environment at the linea-scale (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We do not find evidence for other drivers of lineae formation: lineae do not seem to be systematically co-located with surface-visible tectonic and volcanic features, new small-scale impact events, or the locations of (potentially) recently active lobate scarps (Supplementary Figs. 5,6,7). Interestingly, lineae do not seem to be abundant in the presumably volatile-rich LRM, although the relative number of lineae in LRM is slightly higher than for hollows ( ~ 10% vs. ~7%, Fig. 2, per14). We note that the hot poles and regions with peak insolation do not necessarily need to feature the highest volatile abundance and devolatilization rates, as they have been exposed to substantially larger temperatures for geologically extended periods of time. Ref. 23 suggest that cold longitudes can accumulate substantially more volatiles and sequester them at shallower depths, which could help explain why lineae distribution includes colder regions and is not more clearly correlated with insolation.

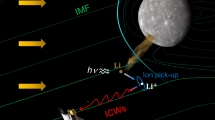

Overall, the combination of two—and possibly three—key factors seems to be driving lineae formation: (A) the presence of an interface between a volcanic smooth plains ‘cap layer’ and a volatile-rich layer underneath, (B) an impact event that penetrates both layers and creates the topographic relief and subsurface fracture networks required for mass wasting as well as the lateral and vertical migration of volatiles and heat, and, possibly, (C) insolation that enhances or drives the devolatilization of near-surface volatiles. We summarize this hypothesis in a preliminary conceptual model (Fig. 6) that can serve as a basis for future investigations and scrutiny.

Young, ~km-sized impact craters penetrate a volcanic smooth plains unit (or another ‘cap’ rock) and an underlying volatile-rich layer; the model is drawing from sketches of the genesis of volatile-rich layers by ref. 42 and laboratory observations of impact-generated fracture patterns by43. The fracture network created by the impact and through subsequent tectonic processes and thermal cycling enables the vertical transport of volatiles and heat, which leads to hollow formation in level terrain, particularly in crater floors with heavily fractured bedrock. At the upper, steepest, predominantly equator-facing sections of the crater wall, devolatilization of near-surface ( ~ top-meter) volatile phases such as sulfur, stearic acids, or fullerenes is potentially enhanced or driven by insolation. Local devolatilization triggers the formation of hollows or hollow-like features along with the continuous, low-volume, terrain-hugging downslope displacement of material, possibly originating from the interface between the (smooth plains) cap and the underlying volatile-rich layer, which might funnel volatiles and heat to specific outcrops in the slope – or feature specific mechanical behavior that is (more) conducive to downslope displacement. Small-scale impact events could trigger the burst release of volatiles and the displacement of material anywhere on a slope; fractures created by small-scale impacts might interweave with the wider fracture network and lead to long-term lineae activity. This conceptual hypothesis can be scrutinized by upcoming BepiColombo investigations.

We note that there are numerous equator-facing walls in young craters that penetrated smooth plains units without any (MDIS NAC-scale) lineae. In addition, there is a small population of lineae that is not located in impact craters, in smooth plains, or on equator-facing slopes. These observations suggest that not all two or three factors and processes might be equally critical for the formation of lineae. For example, it might not be important whether a volatile-rich layer is covered by smooth plains or any other ‘cap’ rock, as long as there exists a cap that shields the underlying volatile-rich layer over geologic time. In addition, other processes might be involved in lineae formation, such as small-scale impact events that could trigger the local, burst-like release of volatiles and the displacement of material on inclined terrain, creating lineae (Fig. 3a,c). The fractures created by small-scale impacts might interweave with pre-existing fracture networks and lead to long-term lineae activity. As impacts would release extensive amounts of volatiles at an instance, the shape of the resulting linea deposits might differ from regular, insolation- or heat flow-driven lineae (e.g., Fig. 3a). Similarly, there might exist (un-recognized) sub-classes of lineae that are driven by different processes and occur in different locations—potentially with or without the involvement of volatiles—that are not resolved by the MDIS NAC data.

The modelled surface temperatures at lineae locations are high enough to enable the sublimation of fullerenes (C60, C70), stearic acid (C18H36O2), and elemental sulfur (S), applying SCArFS model results (Sublimation Cycling Around Fumarole Systems24). At 1-m depth, modelled temperatures are still high enough to enable the sublimation of stearic acid and sulfur, but not fullerenes. Notably, the latitude range of lineae detections exceeds the latitude range predicted by SCArFS for fullerene devolatilization. In addition to those observations,24 highlight several issues that are associated with the delivery and sequestration of fullerenes and stearic acid in sufficient quantities on Mercury, which is why elemental sulfur remains as the most promising volatile phase involved in lineae formation, as is for hollows (e.g., refs. 23,24,25,26).

Estimated horizontal growth rates for hollows – and thus potentially for lineae source regions – are very low (e.g., ~1 cm/10 ka3), but estimated vertical growth rates based on the devolatilization of surface-exposed elemental sulfur are substantially higher, ~0.3 to ~2.5 m/year, for hot pole vs ‘warm meridian’ conditions24. While it is unclear what amount of vertical and horizontal growth is required to trigger linea formation, these rates paired with the MDIS spatial resolution (~3 m pixel scale) and temporal baseline (~4 years) might explain why our meter-scale (geomorphic) change detection analysis yielded no results. In other words, the fact that macroscopic lineae activity is not observable in MDIS data agrees with hollow growth rate estimates, implying that activity happens at small scales and/or on timescales beyond ~4 years.

It remains unclear whether linea formation is a singular process that leads to local volatile depletion or whether linea sites are re-charged through lateral and/or vertical pathways. We note that slow yet continuous re-charging and activity at lineae locations would agree with an insolation- and heat flow-driven formation mechanism that operates over extended periods of time. The same mechanism would also explain why slope lineae appear exceedingly bright and fresh, without any superposed craters. In this way, our hypothesized conceptual model would also imply that lineae actively form and evolve on Mercury today, as inactive lineae should erode quickly under present-day micrometeoroid impact flux conditions (e.g., refs. 27,28,29).

If lineae formation was tied to insolation, lineae activity could be expected to peak over local noon and follow a distinct bi-annual/diurnal trend. In turn, any distinct lineae activity in the early local morning or late afternoon could imply a less important role of insolation. We note that due to their position on slopes, any geomorphic or morphometric change of lineae could be expected to be more pronounced than in and around hollows that are usually located on flat terrain, rendering lineae a potentially more sensitive – and thus more expressive – descriptor of present-day volatile loss on Mercury. One remaining question is concerned with the fate of slope lineae, similar to the fate of hollows: What happens to lineae once all devolatilization activity ceases? One possible explanation is an observational bias introduced by the currently available image data, where inactive lineae might be more easily overlooked due to a lack of contrast with their surroundings (Supplementary Fig. 8), as previously hypothesized by ref. 26 for inactive hollows. Alternatively, inactive lineae might be rapidly eroded (e.g., ref. 3).

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission and SIMBIO-SYS instrument suite will provide the opportunity to test the proposed conceptual model of slope lineae formation, providing more spatial coverage, better spatial resolution ( ~ 6 meter pixel scale, covering at least ~10% of the surface in the 1-year nominal mission, and ~58 m pixel scale globally4, cf. Supplementary Fig. 1), and a long temporal baseline for change detection analyses ( ~ 15 to ~17 years between MESSENGER and BepiColombo). We note that 77% of lineae were identified in images with pixel scales better than 58 m (Supplementary Fig. 1), underlining the importance of spatial resolution for the detection of lineae. A combination of systematic, global mapping of lineae distribution, morphometry, and activity, paired with local, detailed geologic mapping of selected lineae locations and their surroundings with higher-resolution data—and particularly high-resolution topographic and thermophysical models—will help to scrutinize and adapt the hypotheses presented above. We note that our global database of lineae locations can serve as a target list for BepiColombo SIMBIO-SYS observations4. We recommend focusing the SIMBIO-SYS change detection efforts on lineae locations in the proximity of the hot poles – acquiring as high-resolution images as possible –, which are the most likely to experience the highest formation rates, including a ‘control group’ at high latitudes and along the cold meridian. These observations could prove the present-day activity of lineae and provide constraints on their formation rates. Frequent imaging of a small number of lineae clusters over the course of a mercurian day and, particularly, over the course of the later morning, noon, and early afternoon, would enable the verification or rejection of insolation as a key factor of lineae formation, for example, focusing on clusters that showed lineae formation between MESSENGER-BepiColombo. If BepiColombo can confirm the active formation of slope lineae and their association with volatile loss, slope lineae would open a unique, quantitative (geomorphic) window into Mercury’s present-day volatile budget.

Methods

Few-shot learning-driven lineae mapping

We closely follow the methodological approach by ref. 14 who used a convolutional neural network and MESSENGER MDIS NAC data (Mercury Dual Imaging System Narrow Angle Camera10) to catalog more than 19,000 individual hollows across Mercury. A similar approach has been used to map geologic and atmospheric features of interest on planetary bodies across the solar system, such as pitted cones and dust devils on Mars30,31, rockfalls on the Moon32, and lineaments on Europa33. Specifically, we follow14 in considering a total of 112,424 MDIS NAC images, which includes all available images with pixel scales better than 150 m, and excludes images with error flags. Importantly, the illumination and viewing geometry of the NAC dataset is heterogeneous, with incidence, phase, and emission angles ranging from ~0 to ~90; ~25 to ~150°, and ~0 to ~80°, respectively, and pixel scales ranging from ~3 to 150 m (we exclude images with resolutions beyond 150 m14, Supplementary Figs. 1,9). Due to the orbit of MESSENGER, the vast majority of higher resolution NAC images is located in the northern hemisphere, which effectively limits our ability to survey the southern hemisphere for small targets such as slope lineae (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Due to the lack of a-priori knowledge about a sufficient amount of lineae locations that would directly allow us to construct datasets appropriate for convolutional neural network training and testing, we perform a three-stepped approach. In step 1, we utilize the 15 NAC images that cover slope lineae locations as presented throughout the available conference proceedings and literature2,3,5,8,9 to train a first-generation detector. That first detector is deployed on the full MDIS NAC dataset (112,424 images) and is able to identify 22 additional, previously unknown NAC images that contain slope lineae. We use the combination of both image sets (n = 37) to train a second detector, which is in turn able to identify 27 additional images with slope lineae. In a third step, we use our final set of 64 streak-bearing NAC images to train and validate a final, third-generation slope lineae detector, using 226 training/validation and 19 test labels (Supplementary Table 1), with a 90:10 train-validation split to maximize the number of training labels. Here, each label represents a human-drawn, rectangular box around one individual slope linea, tightly encompassing the entire feature.

Following the same procedures as14, we use those labels to fine-tune a pre-trained YOLOv5x model (https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5, PyTorch 1.13.0) and verify its performance. Training logs are showcased in Supplementary Fig. 10. In the testset, the third generation detector achieves a recall of 0.65, a precision of ~0.6 (both at a confidence score of 0.3), and an average precision (AP) of ~0.71. These numbers suggest (a) that the detector is able to identify ~65% of all lineae in the testset; and (b) that ~60% of all detections are correct, at a model confidence score (posterior probability) of 30%. The training and testing requires less than 10 min on a NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (graphic Processing Unit). Assessments of the performance of YOLOv5 and more recent architectures, such as YOLOv8, have shown varied results, where YOLOv5 tends to outperform YOLOv8 (e.g., refs. 34,35,36), which is why we continue to rely on YOLOv5 for this study.

The deployment of the validated detector on the full MDIS NAC dataset (112,424 images) requires less than 60 s and stores full-resolution thumbnails of each linea ‘candidate’ as well as all relevant model and MDIS NAC meta information, such as image acquisition date, incidence, phase, and emission angles, pixel scale, and model confidence. In addition, the pipeline computes and stores the real world coordinates of each candidate, as reconstructed from the associated SPICE kernels and NAC reticles, i.e., the right ascension of the principal points of the camera. Notably, the absolute accuracy of the reconstructed geolocation of all lineae is highly dependent on the accuracy of the meta-information available for each NAC image.

All lineae candidates are manually and independently reviewed and de-duplicated by four human experts who (a) remove all false detections from the dataset and (b) remove all lineae that have been identified more than once, for example, in images taken of the same location (‘de-duplication’). The removal of false detections and de-duplication ensures that the science analysis only considers actual slope lineae—and does not use the same linea several times when computing global geostatistics. Notably, the fact that the detector is able to identify the same linea in several images with different illumination and viewing geometries suggests that it is robust.

Geostatistical analysis and change detection

We conduct a global geostatistical analysis using several pre-existing, auxiliary datasets, specifically a global topographic model (Mercury MESSENGER Global DEM 665 m37), catalogs of smooth plains38, craters larger than 20 km15, craters larger than 40 km with associated degradation stages18, and hollows14, as well as a global map of Low Reflectance Material (LRM39). In addition, we use a thermophysical model developed by ref. 40 to create global maps of bi-annual (diurnal) maximum temperature at surface level and at 1-m/2-m depth as well as bi-annual (diurnal) thermal amplitude at surface level and at 1-m/2-m depth, where thermal amplitude is defined as the temperature difference between the maximum and minimum bi-annual (diurnal) temperature. The thermophysical model solves 1-D vertical heat conduction with depth-dependent thermophysical properties, computes insolation with Mercury’s eccentric 3:2 geometry and ray-traced topographic shadowing that treats the Sun as an extended disk, and includes facet-to-facet self-heating via scattered and re-radiated flux, while neglecting lateral heat transport and atmospheric effects40. We determine the statistical significance of the similarity or differences of relevant lineae and background distributions using a homoscedastic two-sample t-test with an α-value of 0.05. For the analysis of the bi-annual (diurnal) maximum temperature (surface level, 1 m depth, 2 m depth) and the bi-annual (diurnal) thermal amplitude (surface level, 1 m depth, 2 m depth) we additionally use a two-tailed Mann–Whitney u-test with an α-value of 0.05.

Where available, we use several MDIS NAC acquisitions of lineae-bearing locations to manually search for (a) geomorphic changes to existing lineae and (b) newly-formed lineae. Overall, we identify 46 locations across the planet that feature at least two MDIS NAC images, featuring temporal baselines (time difference between the individual acquisitions) of up to ~4 years.

Methodological and data limitations

This analysis is subject to two key limitations: (1) the overall scarcity and heterogeneity of the available MDIS image data (in space, time, and illumination and viewing geometry, Supplementary Fig. 1) and (2) the low spatial resolution of the available global auxiliary data products such as topography ( ~ 665 m pixel scale), LRM ( ~ 500 to ~5000 m pixel scale), and modelled thermophysical properties ( ~ 2660 m pixel scale) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Limitation (1) implies, for example, that our catalog of lineae locations is likely incomplete, particularly in the southern hemisphere, which is likely to affect the accuracy of the reported statistics, such as related to the co-location of lineae with hollows, smooth terrains, and LRM. Limitation (2) implies, for example, that the geostatistical analyses that are related to, for example, the topography and the thermal environment do not properly capture the local, small-scale relations and interactions of lineae to/with their physical environment, which might omit correlations in the reported statistics. Image and auxiliary datasets with higher resolution, as anticipated from the BepiColombo mission, will help to address both key limitations. We underline the importance of further, local studies of the geology of lineae-bearing regions with high-resolution MESSENGER data, where possible, to further inform and guide the upcoming BepiColombo investigations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

This work is exclusively based on open software and data. The produced catalog of slope lineae is openly available in41. MESSENGER MDIS NAC and WAC data are openly available here: https://ode.rsl.wustl.edu/mercury/index.aspx. The USGS topography product that we used (Mercury MESSENGER Global DEM 665 m) is openly available here: https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/mercury_messenger_global_dem_665m.

References

Solomon, S., McNutt, R., Gold, R. & Domingue, D. Messenger mission overview. Space Sci. Rev. 131, 1–4 (2007).

Blewett, D. et al. Hollows on Mercury: MESSENGER evidence for geologically recent volatile-related activity. Science 333, 1856–1859 (2011).

Blewett, D., Ernst, C., Murchie, S. & Vilas, F. Mercury’s hollows. In Mercury: The View after MESSENGER. Cambridge Planetary Science (Solomon, S. C., Nittler, L. R., Anderson, B. J., eds) 324–345 (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Cremonese, G. et al. SIMBIO-SYS: scientific cameras and spectrometer for the bepicolombo mission. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 75 (2020).

Malliband, C., Conway, S., Rothery, D. & Balme, M. Potential identification of downslope mass movements on Mercury driven by volatile-loss. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 50 #1804, (2019).

Dzurisin, D. Mercurian bright patches: evidence for physio-chemical alteration of surface material? Geophys. Res. Lett. 4, 383–386 (1977).

Blewett, D. et al. Multispectral images of Mercury from the first MESSENGER flyby: analysis of global and regional color trends. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 285, 3–4 (2009).

Conway, S. et al. Mass wasting on Mercury – Regolith properties and volatile content. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 56 #19922025 (2025).

Rothery, D. et al. Rationale for BepiColombo Studies of Mercury’s Surface and Composition. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 66 (2020).

Hawkins, S. et al. The Mercury dual imaging system on the MESSENGER spacecraft. Space Sci. Rev. 131, 1–4 (2007).

Morris, E. Auerole deposits of the martian volcano Olympus Mons. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 87, 1164–1178 (1982).

McEwen, A. et al. Seasonal Flows on warm martian slopes. Science 333, 6043 (2011).

Kokelaar, B., Bahia, R., Joy, K., Viroulet, S. & Gray, J. Granular avalanches on the Moon: mass-wasting conditions, processes, and features. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 122, 9 (2017).

Bickel, V. T., Deutsch, A. & Blewett, D. Hollows on Mercury: creation and analysis of a global reference catalog with deep learning. J. Geophys. Res. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2, 1 (2025).

Fassett, C., Kadish, S., Head, J., Solomon, S. & Strom, R. The global population of large craters on Mercury and comparison with the Moon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 10 (2011).

Chapman, C. et al. (2018). Impact Cratering of Mercury. In Mercury: The View after MESSENGER. Cambridge Planetary Science (Solomon, S. C., Nittler, L. R., Anderson, B. J., eds.). 324–345 (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Xiao, Z. et al. Comparisons of fresh complex impact craters on Mercury and the Moon: Implications for controlling factors in impact excavation processes. Icarus 228, 260–275 (2014).

Kinczyk, M., Prockter, L., Byrne, P., Susorney, H. & Chapman, C. A morphological evaluation of crater degradation on Mercury: Revisiting crater classification with MESSENGER data. Icarus 341, 113637 (2020).

Bickel, V. T., Aaron, J. & Goedhart, N. A global perspective on lunar granular flows. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 12 (2022).

Deutsch, A. et al. Temperature-related variations of 1064 nm surface reflectance on mercury: implications for space weathering. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 8 (2024).

Watters, T. et al. Recent tectonic activity on Mercury revealed by small thrust fault scarps. Nat. Geosci. 9, 743–747 (2016).

Speyerer, E., Robinson, M. & Sonke, A. Present day endogenic and exogenic activity on mercury. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100783 (2022).

Verkercke, S. et al. A novel theoretical approach to predict the interannual variability of sulfur in Mercury’s exosphere and subsurface. Frontiers in Astronomy Space Sci. 12, 1565830 (2025).

Phillips, M., Moersch, J., Viviano, C. & Emery, J. The lifecycle of hollows on Mercury: an evaluation of candidate volatile phases and a novel model of formation. Icarus 359 (2021).

Wang, Y., Xiao, Z., Chang, Y. & Cui, J. Lost volatiles during the formation of hollows on Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, 9 (2020).

Deutsch, A., Bickel, V. & Blewett, D. Hollows on Mercury: global classification of degradation states and new insight into hollow evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 130, 2 (2025).

Marchi, S., Morbidelli, A. & Cremonese, G. Flux of meteoroid impacts on Mercury. Astronomy Astrophys. 431 (2005).

Janches, D. et al. Meteoroids as one of the sources for exosphere formation on airless bodies in the inner solar system. Space Sci. Rev. 217, 50 (2021).

Costello, E., Ghent, R., Hirabayashi, M. & Lucey, P. Impact gardening as a constraint on the age, source, and evolution of ice on Mercury and the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, 3 (2020).

Mills, M., Bickel, V., McEwen, A. & Valantinas, A. A global dataset of pitted cones on Mars. Icarus 418 (2024).

Conway, S. et al. A global survey for dust devil vortices on Mars using MRO context camera images enabled by neural networks. Planetary Space Sci. 259 (2024).

Bickel, V. T., Aaron, J., Manconi, A., Loew, S. & Mall, U. Impacts drive lunar rockfalls over billions of years. Nat. Commun. 11, 2862 (2020).

Haslebacher, C., Thomas, N., Bickel, V. LineaMapper: a deep learning-powered tool for mapping linear surface features on Europa. Icarus 410 (2024).

Hirschberg, J., Bickel, V. & Aaron, J. Deep-learning-based object detection and tracking of debris flows in 3-D through LiDAR-camera fusion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 63 (2025).

Vaidya, H., Gupta, A. & Ghanshala, K. K. Detecting buildings from remote sensing imagery: Unleashing the power of YOLOv5 and YOLOv8. Proceedings 3rd Int. Conf. Innov. Sustain. Comput. Technol. (CISCT), Sep. 2023 (2023).

Gasparovic, B., Mausa, G., Rukavina, J. & Lerga, J. Evaluating YOLOV5, YOLOV6, YOLOV7, and YOLOV8 in underwater environment: Is there real improvement? Proceedings 8th Int. Conf. Smart Sustain. Technol. (SpliTech), Jun. 2023 (2023).

USGS (2016). Mercury MESSENGER Global DEM 665m. USGS Astrogeology Science Center. : https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/mercury_messenger_global_dem_665m

Denevi, B. et al. The distribution and origin of smooth plains on Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 5 (2013).

Klima, R., Denevi, B., Ernst, C., Murchie, S. & Peplowski, P. Global distribution and spectral properties of low-reflectance material on Mercury. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 7 (2018).

Cambianica, P. et al. The thermal impact of the self-heating effect on airless bodies. The case of Mercury’s north polar craters. Planet. Space Sci. 253 (2024).

Bickel, V. T. Dataset to: Slope Lineae as Potential Indicators of Recent Volatile Loss on Mercury [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.48620/92770 (2026).

Rodriguez, J. et al. Mercury’s hidden past: revealing a volatile-dominated layer through glacier-like features and chaotic terrains. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 219 (2023).

Polanskey, C. & Ahrens, T. Impact and Spallation Experiments: fracture patterns and spall velocities. Icarus 87, 140–155 (1990).

Acknowledgements

V.T.B. acknowledges the fellowship funding provided by the Center for Space and Habitability at the University of Bern.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.T.B.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization; G.M.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft; S.B.: formal analysis, writing—original draft; G.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft; P.C.: formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft; A.V.: formal analysis, writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Caitlin Ahrens, Giacomo Nodjoumi and David Rothery for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Claire Nichols and Joe Aslin. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bickel, V.T., Munaretto, G., Bertoli, S. et al. Slope lineae as potential indicators of recent volatile loss on Mercury. Commun Earth Environ 7, 49 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03146-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03146-8