Abstract

Plant resins, serving various essential ecological functions, have traditionally been associated with conifers and angiosperms. Previously, the oldest known resin was identified in the late Carboniferous. Here we reveal that substantial amounts of diterpenoid resins were already present on the surfaces of Middle Devonian land plants. These surface resins, preserved alongside plant cuticles, are rich in nonvolatile tetracyclic diterpenoids and likely played a crucial role in facilitating terrestrial colonization by forming an antitranspirant barrier on the surfaces of early herbaceous plants. These findings not only markedly push back the timeline for the emergence of the earliest resin-producing plants, but also provide valuable insights into the adaptive strategies of early terrestrial flora. Moreover, our results suggest an evolutionary transition from surface to internal resins, revealing a more complex history of resin biosynthesis than previously recognized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant resin is primarily a lipid-soluble mixture of volatile and nonvolatile terpenoid and/or phenolic secondary compounds, typically secreted in specialized structures either internally or on plant surfaces1. Historically, these resins have been associated primarily with conifers and angiosperms, playing important ecological roles, including sealing wounds, defense against pathogen infections, and providing resistance to desiccation, ultraviolet radiation, and high temperatures1,2. Fossil resins, often highly resistant to common degradation mechanisms, allow them to be preserved in the geological record. Previously, the earliest known evidence of fossil resin was reported from the late Carboniferous and is associated with gymnosperms1,2,3,4.

Plant cuticles cover nearly all aerial non-woody parts of terrestrial plants. A typical plant cuticle consists primarily of a lipid biopolymer called cutin and a variety of compounds soluble in organic solvents, collectively known as cuticular waxes. In contrast to resins, cuticular waxes are primarily composed of very long-chain fatty lipids, including odd-numbered normal alkanes and even-numbered fatty acids, aldehydes, primary alcohols, secondary alcohols, ketones and esters5,6.

Here we show that abundant diterpenoid-rich surface resins were already widespread on Middle Devonian plant cuticles, substantially extending the geological record of plant resin production. These findings indicate that surface resin secretion played an important role in protecting early terrestrial plants from environmental stresses during land colonization.

Results and discussion

Identification of surface resins

The cuticle layers of the Middle Devonian period (Givetian, 382–387 Ma) were extracted from Chinese cuticle-rich coals7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, notable for their high content of plant cuticles. These cuticles, collected from various regions, are marked by distinctive microscopic features and exhibit a wide range in thickness, from as thin as 1–5 μm to over 300 μm (Table 1). The observed variations suggest that these cuticles originate from a diverse array of early terrestrial plants9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

Surprisingly, microscopic examinations revealed that these fresh cuticles were commonly covered by thin organic films, which displayed a distinctive brown fluorescence under UV light, strikingly contrasting with the yellow fluorescence of the cuticle proper (Fig. 1a–h). Scanning electron microscope observations indicated that these films either spanned continuously across the cuticles or broke into fragments (Fig. 1i, j, l). The thickness of these films varies widely, ranging from less than 1 micrometer to several micrometers, and is directly proportional to the thickness of the underlying cuticles. Films on thicker cuticles were generally thicker and comprised multiple laminar layers (Fig. 1j), while films on thinner cuticles were thinner and typically consisted of a single layer or just a few (Fig. 1i). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy detected minor clay-mineral inclusions within the films (Fig. 1i, l), likely introduced during burial. In some samples, these films notably occluded the pores and guard cells of stomata. Moreover, the films can dissolve completely or nearly so in a dichloromethane-methanol mixture (Fig. 1k, m).

a–h Optical microscope images under fluorescence illumination showing resin films exhibiting brown or dark brown fluorescence on the outer surfaces of cuticles, which fluoresce bright yellow. i SEM back-scattered image of a simpler resin film structure with fewer layers coating a thin cuticle (Inset: EDS spectrum of the resin film). j SEM image of a complex, multilayered resin film coating a thick cuticle (Inset: EDS spectrum of the cuticle). k SEM image of resin film after substantial dissolution in a dichloromethane-methanol mixture, compared to its initial state in (j) (Inset: EDS spectrum of the cuticle). SEM images comparing a resin film before (l) and after (m) partial dissolution in the same solvent (Insets: corresponding EDS spectra highlighting distinct elemental compositions of the resin film (l) and underlying cuticle (m)).

To determine the composition of the films, purified cuticles were extracted using a dichloromethane-methanol mixture. The resulting extracts were then analyzed using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Remarkably, substantial amounts of diterpenoids, alongside conventional wax compounds, were identified in the cuticle extracts (Fig. 2), characterized by a key ion or base peak at m/z 123 in their mass spectra17. The concentrations of these diterpenoids in the maltene fractions are notably high, reaching 180 mg/g, far surpassing those of aliphatic wax lipids and other compounds (Table 1). Diterpenoids are rarely found in cuticles, and the clear positive correlation between the diterpenoid content and the film thickness (Table 1 and Fig. 3) indicates that these compounds originated from the cuticle surface films and are their primary soluble components. Because diterpenoids are signature constituents of plant resins, their presence demonstrates that the films are fossilized diterpenoid resins preserved alongside Middle Devonian cuticles (Fig. 1). Moreover, some micrographs capture these films apparently forming by the coalescence of discrete, micron-scale droplets—very like plant resin exudation—providing further confirmation of their resinous origin (Fig. 1g).

Each data point represents the average diterpenoid concentration in the maltene fractions and the median resin film thickness for a given region. Horizontal and vertical bars indicate the interquartile (middle 50%) range of resin film thickness and the full range of diterpenoid concentration, respectively. The strong positive correlation indicates that regions with thicker resin films generally exhibit higher diterpenoid concentrations.

Resins in plants can be broadly classified into two main types: internal and surface resins1,2. Internal resin, synthesized within endogenous secretory structures or ducts, is commonly found in conifers and angiosperm trees. Surface resin, in contrast, is secreted externally from glandular trichomes or epidermal cells, often forming continuous protective varnishes that coat stipules, leaves, stems, or floral calyxes1,2. The resin films examined in our studies clearly represent this surface resin type. Under favorable geological conditions, these surface resins can be preserved alongside fossilized plant cuticles. Numerous glandular trichomes directly observed on cuticle surfaces, serving as the primary secretory structures of surface resin, further support the presence and classification as surface type (Fig. 4a–d). Exceptionally preserved trichomes, closely associated with resin films, directly confirm that resin secretion occurred externally via these trichome structures (Fig. 4d). However, trichomes commonly detach during fossilization, leaving behind characteristic circular or subcircular perforations and fragmented trichome remains on the cuticles (Fig. 4e–g). These perforations generally range from 10 to 30 μm in diameter, notably smaller than the stomata observed in the same specimens. Moreover, numerous trichome imprints preserved within the resin films clearly originate from these perforations (Fig. 4f, g), providing compelling visual evidence that glandular trichomes were responsible for external resin secretion in these early terrestrial plants. Additionally, various larger structures termed tubercles—conoidal, spiniform, dome-shaped, or flattened—are present on some cuticle surfaces, often encircled by concentric folds of the cuticle (Fig. 4h, i). These tubercles, markedly larger than the trichomes, typically measure approximately 50–100 μm in diameter and 200–400 μm in length. Featuring central canals, they are suggested to have a secretory function and potentially served as additional resin secretion channels18.

SEM images of trichomes on cuticle surfaces: a intact, long-stalk trichome (base diameter 15–20 μm, length approximately 200–300 μm); b distinct star-like trichome; c compressed branching trichome; d detached long-stalk trichome partially covered by resin film; e fragmented hollow trichomes and associated basal perforations. f, g Optical microscope images in transmitted light, highlighting numerous trichome imprints and associated perforations. h SEM image of a tubercle remnant surrounded by small trichome perforations. i SEM image showing tubercles and their distinct basal perforations.

It was previously believed that the earliest known resin was associated with gymnosperms from the late Carboniferous1, and that the oldest known amber, a visually distinct form of fossilized resin, originated around 320 million years ago during the Carboniferous period19. Moreover, surface resin secretion was thought to be exclusive to angiosperms in modern plants. Therefore, the identification of surface resin in Middle Devonian plants is both remarkable and unexpected. This discovery not only pushes back the timeline for the emergence of the earliest resin-producing plants but also overturns the longstanding view that surface resins were produced exclusively by angiosperms1. Consequently, this finding challenges existing paradigms about resin production in plant lineages, suggesting a more complex evolutionary history of resin biosynthesis than previously understood.

Interestingly, spine-like projections with darkened tips have been reported in Lower Devonian cuticles20,21. These structures, which resemble resin canals or resinous materials, were identified based on morphological observations, but no conclusive anatomical or chemical evidence for resin secretion was provided. Further studies are needed to confirm the functional role of these structures and determine whether the darkened tips are indeed resinous materials.

Molecular composition of the surface resin

Diterpenoids identified in resin films primarily consist of tetracyclic diterpanes, accompanied by low abundances of monoaromatic and oxygenated derivatives. The tetracyclic diterpanes eluted between the C18 and C24 normal alkanes on the total ion chromatograms (TIC) of saturated fractions (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1) and have a general formula of CnH2n-6. The carbon number of these compounds typically ranges from C18 to C22, with the C20 tetracyclic diterpanes and their C18–C19 homologues being the most abundant constituents. Particularly in Middle Devonian cuticle extracts, C20 tetracyclic diterpanes (molecular weight 274) have an unusually large number of isomers and homologues (Fig. 2)22,23,24, far surpassing those reported previously. The identified compounds mainly include beyeranes and atisanes, with most of the other unknown compounds interpreted based on their mass spectra and the more stable atisane skeleton (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2)22. The presence of 16β(H)-kaurane, which typically co-elutes with 16β(H)-atisane, is inferred from the occurrence of its homologues. Despite past variations in nomenclature by different scholars23,24, the composition of these tetracyclic diterpanes is consistent in all samples. In addition to the primary tetracyclic diterpanes, their monoaromatic derivatives are also detected in resin films characterized by higher thermal maturity. Conversely, oxygenated derivatives, predominantly consisting of C18 and C19 tetracyclic diterpenoid ketones, are found in high abundance in resin films with lower thermal maturity (Supplementary Fig. 3).

A high abundance of tetracyclic diterpenoids is typically associated with internal resins produced by conifers, though trace amounts occur universally in plants due to gibberellin biosynthesis. These diterpenoid compounds, characterized by beyerane, atisane, and kaurane skeletons, are especially prevalent in the resins of modern conifer families such as Cupressaceae, Podocarpaceae, and Araucariaceae25. Historically, their presence in Carboniferous coals has been attributed to early conifers, particularly the Voltziales26,27. However, exceptionally high concentrations of tetracyclic diterpenoids have also been reported in several Middle Devonian sediments and cuticle-rich coals, including the famous Barzas coal in Russia28. The origin and precursors of these abundant compounds have puzzled researchers29, as conifers had not yet evolved during the Middle Devonian period, and there is no evidence of resinite individuals—fossilized forms of internal resin—in these deposits. Previous research by Sheng et al. suggested a microbial, fungal, or lower plant origin for these tetracyclic diterpenoids in Devonian coals23, while Thomas and Peters et al. suggested that a complex gibberellin synthesis pathway may explain their high abundance during the Middle Devonian30,31. Recently, high abundances of these tetracyclic diterpenoids have also been identified in Upper Devonian coals32. Similarly, the precise origins and sources of these compounds remain unresolved.

Our research provides further insights into this long-standing puzzle, confirming that the high abundances of tetracyclic diterpenoids in the Middle Devonian originated from surface resins, which were already present in early terrestrial flora before the emergence of conifers. This finding suggests that tetracyclic diterpenoid resin secretion evolved much earlier than previously recognized. Consequently, the notable abundances of these compounds in Upper Devonian coals likely originated from similar resins, indicating that resin secretion was also present in Late Devonian, either surface resins or newly evolved internal resins. Collectively, these findings outline an evolutionary diversification of tetracyclic diterpenoid resin biosynthesis, beginning with surface resins in Middle Devonian plants, continuing through Late Devonian, and ultimately transitioning to the distinctly defined internal resin systems characteristic of later Carboniferous gymnosperms, particularly early conifers such as the Voltziales. This evolutionary trajectory provides valuable insights into the timing and early evolution of surface resin production, greatly enhancing our understanding of plant evolutionary biology and biochemical adaptations. Additionally, the widespread occurrence of abundant tetracyclic diterpenoids during the Middle Devonian suggests that early terrestrial plants had already evolved effective biochemical mechanisms for synthesizing and secreting surface resins by that early stage of terrestrial colonization.

In addition to diterpenoids, expected components of cuticular wax were also identified in the extracts of cuticles, including normal alkanes, long-chain fatty acids, alcohols, and esters. In most samples, long-chain normal alkanes displayed a noticeable odd chain-length predominance (Fig. 2). These long-chain normal alkanes typically originated from cuticular waxes and were either synthesized directly by higher plants or derived from defunctionalized acids, alcohols, or esters due to diagenetic alteration31. Other wax compounds with oxygen-containing functional groups were present in low amounts, likely due to extensive defunctionalization over a long geological timeline (Supplementary Fig. 3). The total concentrations of wax lipids in the maltene fractions range from 3 to 33 mg/g (Table 1). These cuticular wax may either be deposited on the surface of the cuticle and mixed with the resin films, or embedded in the cutin matrix as intracuticular waxes.

Facilitating early plant colonization

Various types of resins serve different ecological roles. Internal resin is typically released by a plant when injured, playing a crucial role in sealing wounds and protecting the plant from pathogen infections. In contrast, surface resin, which covers stems, leaves, and sometimes reproductive organs, is commonly found in angiosperm shrubs and herbs, particularly in arid habitats. This type of resin provides additional protection against water loss, ultraviolet radiation, and high temperatures1,2. Our research highlights that surface resins from Middle Devonian plants were notably rich in nonvolatile tetracyclic diterpenoids, which would harden to form a protective barrier upon exposure to air. Deposited primarily along the stems, these resinous layers likely served as an antidesiccant33, playing a crucial role in facilitating early plant colonization of terrestrial environments.

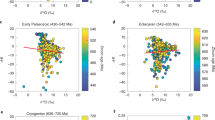

Supporting this interpretation, our quantitative data reveal a strong positive correlation between cuticle thickness and both the thickness and abundance of surface resin, with thicker cuticles consistently exhibiting thicker resin films and higher concentrations of diterpenoids (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Notably, this positive relationship is evident not only across the entire dataset but also within each individual geographic region studied (Fig. 6). Detailed microscopic observations further confirm this pattern at the scale of individual plant organs: sun-exposed surfaces, which naturally have thicker cuticles, display proportionally thicker resin films compared to shaded surfaces, which possess thinner cuticles and correspondingly thinner resin coatings (Fig. 1h). Cuticle thickness itself is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as sunlight exposure, water availability, and temperature, and plants in arid habitats typically evolve thicker cuticles as an adaptation to minimize water loss34,35. Thus, the consistent positive relationship observed between cuticle thickness and resin abundance in Devonian plants strongly suggests that the increased secretion of surface resin was a critical adaptive strategy for these early plants, supplementing enhanced cuticle thickness to effectively counteract environmental stresses and facilitate their successful colonization of terrestrial habitats. Figure 7 presents a detailed reconstruction of the external secretion of surface resins and the formation of protective resin sheet on the cuticle surfaces of early terrestrial plants.

The Middle Devonian cuticles analyzed primarily originate from herbaceous plants9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The early plant Orestovia, identified as the coal-forming plant of the Barzas coal, where abundant diterpenoids were found, was also recognized as herbaceous36,37. Interestingly, similar to modern angiosperm shrubs and herbs that mainly secrete surface resin, these ancient herbaceous plants also secreted abundant surface resin, a trait less frequently observed in trees1. This notable similarity indicates that the ability to produce surface resin has been a critical evolutionary adaptation for herbaceous plants across geological epochs, providing a survival advantage in dry and arid conditions.

Outlook

The evolutionary transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments was a key step in the evolutionary history of early land plants. Overcoming challenges such as minimizing water loss and mitigating ultraviolet radiation exposure was vital. Surface resins, serving as effective antitranspirants, likely played an important role in terrestrial adaptation in early land plants. Given that plant colonization of land dates back to the Ordovician period, it is plausible that these critical adaptations may have begun even earlier than the Middle Devonian period. This work provides a framework for investigating the presence of surface resins in even earlier geological periods, potentially offering groundbreaking insights into the evolution and adaptation mechanisms of early land plants. Moreover, these findings encourage further research into the evolutionary diversification from surface to internal resin systems, potentially offering profound insights into the origins and development of internal resins in plants.

Methods

Materials

Middle Devonian cuticle-rich coals, characterized by their notably high cuticle content, are restricted to a few selected global locations. These include the Barzas coals in Russia, with a cuticle content of 70% to 80%38, and several sites across China. Within China, major deposits are predominantly located in the Bulonggoer (BLG) region of Xinjiang Province, the Wujing (WJ), Batang (BT), Damo (DM), and Baishaping (BSP) areas of Yunnan Province, and the Damaidi (DMD) area of Sichuan Province (Supplementary Fig. 4). The coal deposits from the WJ, BT, DM, BSP, and DMD areas are found in the Haikou Formation, while those in the BLG area occur in the Hujiersite Formation. All these coals and their respective formations have been definitively dated to the Givetian period of the late Middle Devonian7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,39,40,41.

In this study, fresh coal samples were collected from all the aforementioned Chinese locations by excavating trenches perpendicular to the strike of the coal seams. Bulk representative samples of these Devonian coals were carefully extracted and immediately sealed in paper bags to minimize contamination. These samples are characterized by their exceptionally high cuticle contents, typically exceeding 60%, with specimens from the DM and BSP areas commonly exceeding 90%. This high concentration of cuticles imparts a distinct papery texture, allowing them to be easily separated into flexible, leaf-like layers. These coals are colloquially referred to as “paper coal” or “leaf coal”. The maturity levels of these coal samples are generally low, as indicated by vitrinite reflectance (Ro) values ranging from 0.35% to 0.69%. Detailed characteristics of these samples have been extensively documented in previous literature7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Cuticles from these coals exhibit notable regional variation in thickness and microscopic features (Supplementary Fig. 5)11,12,13. Specifically, cuticles from the WJ and BLG coals typically exceed 50 μm in thickness, whereas those from the BSP and DM coals predominantly range between 20–150 μm and 10–50 μm, respectively. In contrast, cuticles from the BT and DMD coals consistently measure less than 10 μm in thickness. Beyond thickness, these cuticles also differ in microstructures (Supplementary Fig. 6). For example, thick cuticles from WJ coals are marked by the presence of numerous tiny pores (<1 μm) that are randomly distributed within the cuticles. In comparison, only a select few cuticles from BLG, BSP, and DM coals exhibit these small pores. Thin cuticles, across the board, tend to display a more uniform and homogeneous structure. Additionally, the unique shapes of stomatal apparatuses observed on the surface of these cuticles further emphasize the distinctive features of each type. This variation in thickness, surface morphology, and microstructure highlights the diversity of early terrestrial plants that contributed to the formation of these coals.

Substantial evidence regarding the botanical origins of these cuticles comes from studies of megafossils and palynology within Devonian cuticle-rich coals. The Middle Devonian coals from the Luquan region of Yunnan (WJ, DM, and BT areas) are primarily derived from Rhyniophytes, Protolepidodendron, Drepanophycus, Psilophyton, and Protopteridium, which are considered the main sources of the cuticles7,8,9,10,11,15. In the DMD coal, Taeniocrada and Barrandeina are the dominant coal-forming plants, while Protolepidodendron and Lepidodendropsis predominate in the BSP coal14. Furthermore, studies on the BLG cuticle-rich coal have shown that herbaceous lycopods were the predominant plants42,43. These coal-forming plants are considered the primary sources of the cuticles analyzed in this study, and as such, their cuticles are expected to be preserved within the coals.

Cuticle purification

In the laboratory, the outer surface of bulk coal samples was removed to further minimize contamination. To facilitate the purification of cuticle layers, the samples were immersed in ultrapure water, which softened and dispersed the material. This was followed by thorough rinsing with ultrapure water to eliminate clay and mineral components, with macerals concentrated using a sieve. Once dried, the sieved samples allowed for the collection of single-layered and sheet-like cuticles through manual selection. If other minor macerals adhered to the cuticle, they were delicately removed using a blade. The distinctive sheet-like and elastic nature of the cuticle, along with its substantial original content enabled the manual section-based purification process to achieve cuticle purity levels exceeding 93%. The selected cuticle layers were then subjected to comprehensive ultrasonic cleaning and carefully cut into 2–4 mm pieces. To further separate the macerals, the cuticle pieces underwent six cycles of freezing and thawing with liquid nitrogen. After these treatments, the cuticle pieces were collected again by manual selection resulting in a final cuticle purity exceeding 98% (Supplementary Fig. 7). Purity assessment was conducted through a systematic maceral counting method (at least 500 points per sample) under a microscope equipped with transmitted light and UV illumination, after crushing the samples to less than 1 mm and forming them into polished slices.

Analytical methods

For chemical analysis, the purified cuticles were ground into a powder finer than 100 mesh and Soxhlet extracted for 48 h using a dichloromethane/methanol mixture in a 1:1 ratio. The extracts were first separated into asphaltene and maltene fractions using n-heptane precipitation. Some maltenes were then fractionated using column chromatography (silica gel over alumina, 3:1) into saturate, aromatic, and NSO fractions by sequential elution with n-hexane, toluene, and chloroform. Prior to gas chromatographic analysis, the maltene and NSO fraction were silylated using BSTFA + TMCS (99/1) for 3 h at 70 °C. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses of the saturated, aromatic, and NSO fractions were conducted using an Agilent Model 6890 gas chromatograph coupled to an Agilent Model 5975i mass selective detector, and fitted with a HP-5MS capillary column (60 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness). The GC operating conditions for the maltene, saturated, and NSO fractions were: 50 °C (1 min) to 120 °C at 20 °C/min, and then to 310 °C at 2 °C/min (hold for 5 min), and the aromatic fraction: 80 °C (1 min) to 310 °C at 3 °C/min (hold for 25 min). The MS transfer line temperature was held at 280 °C and the ion source temperature was 250 °C. The sample was injected in a splitless mode, with an injector temperature at 300 °C. The ion source was operated in the electron impact (EI) ionization mode at 70 eV. Helium was used as the carrier gas (flow rate 1.0 mL/min).

Reference standards of phyllocladanes and kauranes were synthesized through the catalytic hydrogenation of their natural counterparts, phyllocladene and kaurene, respectively. Reduction of phyllocladene yielded 16α(H)- and 16β(H)-phyllocladane in a 4:1 ratio, and similarly for kaurene, with the GC elution order of β before α for both sets of standards. These phyllocladanes and kauranes were analyzed by GC-MS as external standards. Identification of individual diterpenes in the samples was based on a comparison of their mass spectra and retention times with the external standards and those previously reported22,23,44. For quantitative determination of diterpenoid and wax lipid compounds, absolute concentrations of known amounts of standard compounds were added to the maltene fractions prior to the separation steps. The quantification of the compounds was based on their mass chromatogram peak areas compared to those of the internal standards (alkanes: nC24D50, tetracyclic diterpanes: phyllocladane, tetracyclic diterpenoids: kaurenoic acid or 5α-androstenone, esters: ethyl nonadecanoate, alcohols: heneicosanol, fatty acids: 19-methyleicosanoic acid).

Data availability

The supplementary datasets supporting the findings of this study are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30870452). The deposited data include (i) quantitative measurements of cuticle thickness and corresponding surface resin film thickness, and (ii) quantitative data for organic compounds identified in the saturated and maltene fractions of purified cuticle extracts. These datasets provide the source data for the figures and analyses presented in this article.

References

Langenheim, J. H. Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology and Ethnobotany (Timber Press, 2003).

Dell, B. & McComb, A. J. Plant resins-their formation, secretion and possible functions. Adv. Bot. Res. 6, 276–316 (1978).

Pańczak, J., Kosakowski, P. & Zakrzewski, A. Biomarkers in fossil resins and their palaeoecological significance. Earth Sci. Rev. 242, 104455 (2023).

Mastalerz, M. & Zodrow, E. Note on the discovery of Carboniferous amber associated with the seed fern Linopteris obliqua, Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia, Canada. Atl. Geosci. 58, 147–153 (2022).

Walton, T. J. Methods in Plant Biochemistry, vol. 4 of Lipids, Membranes and Aspects of Photobiology (Academic Press, 1990).

Riederer, M. & Markstädter, C. Cuticular waxes: a critical assessment of current knowledge. In Plant Cuticles: An Integrated Functional Approach (ed Kerstiens, G.) 189–200 (Bios Scientific Publishers, 1996).

Song, D. F. et al. Petrology and organic geochemistry of the Middle Devonian cutinitic liptobioliths from Luquan region, Yunnan Province, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 286, 104507 (2024).

Han, D. X. et al. Coal petrology of China 169-171 (China University of Mining and Technology Press, 1996).

Han, D. X. The features of Devonian coal-bearing deposits in South China, The People’s Republic of China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 12, 209–223 (1989).

Dai, S. F., Han, D. X. & Chou, C. L. Petrography and geochemistry of the middle Devonian coal from Luquan, Yunnan province, China. Fuel 85, 456–464 (2006).

Quan, B. & Han, D. X. Fossil communities of coal-bearing formation (Givetian, Middle Devonian) in Luquan, Yunnan—analysis of the origin of cutinitic liptobiolith. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 27, 298–301 (1998).

Song, D. F. et al. Petrology and organic geochemistry of the Baishaping and Damaidi Devonian cutinitic liptobioliths, west of the Kangdian Uplift. China. Pet. Sci. 19, 1978–1992 (2022).

Song, D. F. et al. Petrology and geochemistry of Devonian cutinitic liptobioliths from northwestern China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 253, 103952 (2022).

Wang, Y. B. & Han, D. X. Relationship between material component of Devonian coal and ecological property of early terrestrial plants in Damaidi, Sichuan. Coal Geol. Explor. 1, 1–4 (1998).

Dai, S. F. et al. Recognition of peat depositional environments in coal: a review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 219, 103383 (2020).

Guo, Y. & Wang, D. M. Studies on plant cuticles from the Lower-Middle Devonian of China. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 227, 42–51 (2016).

Noble, R. A. et al. Identification of tetracyclic diterpene hydrocarbons in Australian crude oils and sediments. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1, 32–33 (1985).

Krassilov, K. Orestovia and the origin of vascular plants. Lethaia 14, 235–250 (1981).

Bray, P. S. & Anderson, K. B. Identification of Carboniferous (320 million years old) class Ic amber. Science 326, 132–134 (2009).

Rayner, R. J. New observations on Sawdonia ornate from Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 74, 79–93 (1983).

Edwards, D., Edwards, D. S. & Rayner, R. The cuticle of early vascular plants and its evolutionary significance. In The Plant Cuticle (eds Cutler, D. F. Alvin, K. L. & Price, C. E.) 341–359 (Academic Press, 1982).

Song, D. F., Simoneit, B. R. T. & He, D. F. Abundant tetracyclic terpenoids in a Middle Devonian foliated cuticular liptobiolite coal from northwestern China. Org. Geochem. 107, 9–20 (2017).

Sheng, G. Y. et al. Tetracyclic terpanes enriched in Devonian cuticle humic coals. Fuel 71, 523–532 (1992).

Cheng, D. S., Han, D. X. & Sheng, G. Y. Composition of biomarker in Devonian coals of China and genesis of tetracyclic diterpenoids. Pet. Explor. Dev. 24, 42–46 (1997).

Otto, A. & Wilde, V. Sesqui-, di-, and triterpenoids as chemosystematic markers in extant conifers-A review. Bot. Rev. 67, 141–238 (2001).

Schulze, T. & Michaelis, W. Structure and origin of terpenoid hydrocarbons in some German coals. Org. Geochem. 16, 1051–1058 (1990).

Nádudvari, Á. et al. Preservation of labile organic compounds in sapropelic coals from the Upper Silesian Coal Basin, Poland. Int. J. Coal Geol. 267, 104186 (2023).

Kashirtsev, V. A. et al. Terpanes and sterane in coals of different genetic types in Siberia. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 51, 404–411 (2010).

Killops, S. D. et al. Sedimentary diterpene origins – inferences from oils of varying source depositional environment and age. Front. Geochem. 1241784, 1–21 (2023).

Thomas, J. Biological Markers in Sediments with Respect to Geological Time (University of Bristol, 1990).

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. The Biomarker Guide, Second Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Bushnev, D. A. et al. Geologic and geochemical features of the Upper Devonian coals of the North Timan (the Sula River Coal Field). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 65, 137–153 (2024).

Meinzer, F. C. et al. Effects of leaf resin on stomatal behavior and gas exchange of Larrea tridentata (DC.). Cov. Funct. Ecol. 4, 579–584 (1990).

Goodwin, S. M. & Matthew, A. J. Plant cuticle function as a barrier to water loss. In Plant Abiotic Stress (eds Jenks, M. A. & Hasegawa, P. M.) 14–36 (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2005).

Riederer, M. & Müller, C. Biology of the plant cuticle (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006).

Lapo, A. V. & Drozdova, I. N. Phyterals of humic coals in the USSR. Int. J. Coal Geol. 12, 477–510 (1989).

Snigirevskaya, N. S. & Nadler, Y. S. Habit and relationships of Orestovia (Middle Devonian). Palaeontogr 233B, 11–18 (1994).

Volkova, I. B. Nature and composition of the Devonian coals of Russia. Energy Fuels 8, 1489–1493 (1994).

Marshall, J. E. A. et al. Provincial Devonian spores from South China, Saudi Arabia and Australia. Revue de Micropaléontologie 60, 403–409 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. The Xichong flora of Yunnan, China: diversity in late Mid Devonian plant assemblages. Geol. J. 42, 339–350 (2007).

Xu, H. H. et al. On the Mid Devonian Hujiersite flora from west Junggar, Xinjiang, China, its characteristics, age, paleoenvironment and palaeophytogeographical significances. Acta Palae. Sin. 54, 230–239 (2015).

Xu, H. H. et al. Mid Devonian megaspores from Yunnan and North Xinjiang, China: their palaeogeographical and palaeoenvironmental significances. Palaeoworld 21, 11–19 (2012).

Xu, H. H. et al. Devonian spores from an intra-oceanic volcanic arc, West Junggar (Xinjiang, China) and the palaeogeographical significance of the associated fossil plant beds. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 206, 10–22 (2014).

Noble, R. A. et al. Identification of some diterpenoid hydrocarbons in petroleum. Org. Geochem. 10, 825–829 (1986).

Acknowledgement

We thank D.A. Zinniker for providing detailed comments on the proposed biomarker structures and their stereochemistry. We are especially grateful to the late B.R.T. Simoneit for his valuable suggestions, contributions to manuscript preparation, and assistance in the identification of tetracyclic diterpenoids. We also sincerely thank S. R. Larter for his thoughtful review and constructive feedback on the initial version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42073069 and 42273029). No specific permits were required for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daofu Song conceived the study, conducted the investigation, provided research resources, and wrote the original draft. Tieguan Wang and Ningning Zhong reviewed and edited the manuscript. Honghe Xu contributed to manuscript drafting. Hao Wang, Zhengang Lu, Yue Liu, and Yun Wang contributed to data visualization and research resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Sargent Bray and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yiming Wang and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, D., Wang, T., Zhong, N. et al. Abundant surface resins present on Middle Devonian land plants. Commun Earth Environ 7, 142 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03161-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03161-9