Abstract

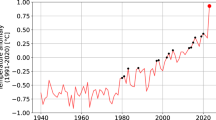

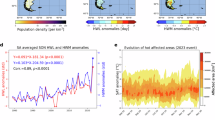

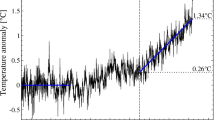

September 2023 featured an unprecedented temperature jump of nearly 0.6 °C above September 2022. Although climate models hardly reproduce such an event, it remains unclear whether the extreme heat could have been caused by internal variability alone or how large an external contribution would be needed to render it plausible. Here we show, based on observational and climate model data, that the temperature jump was virtually impossible under standard anthropogenic forcing, but its probability increases to 0.1% when probabilistic attribution is combined with a process-based analysis to account for contributions that models may underrepresent. Our findings reveal that the heat was disproportionately concentrated over land, particularly in the extratropics. The event resulted from a complex interplay of feedbacks and forcings, with unusually high shortwave forcing amplified by water vapour feedback. Although extreme temperature jumps in September are projected to intensify gradually under additional warming, an internally driven jump of comparable magnitude remains highly unlikely during the next decades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

ERA5 data is publicly available from https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.143582cf, GISTEMP from https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/, HadCRUT from https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/temperature/, and the NINO3.4 time series from https://climexp.knmi.nl/. CMIP6 data is accessible through https://wcrp-cmip.org/cmip-data-access/. The CESM-LE data can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.26024/KGMP-C556. Data from the observationally constrained CESM2 simulation analysed in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. The data needed to reproduce the main figures are available at https://zenodo.org/uploads/18089536.

Code availability

The code used to produce the figures is available at https://zenodo.org/uploads/18089536. Additional code to reproduce the main analysis and intermediate data files is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

GISTEMP Team. GISS surface temperature analysis (GISTEMP), version 4 https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/ (2023).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. Surface air temperature for September 2024 https://climate.copernicus.eu/surface-air-temperature-september-2024 (2023).

Morice, C. P. et al. An updated assessment of near-surface temperature change from 1850: The HadCRUT5 data set. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, e2019JD032361 (2021).

Tippett, M. K. & Becker, E. J. Trends, skill, and sources of skill in initialized climate forecasts of global mean temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110703 (2024).

Hansen, J. E. et al. Global warming has accelerated: Are the United Nations and the public well-informed? Environ.: Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 67, 6–44 (2025).

Minobe, S. et al. Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: beyond the new normal. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 1–11 (2025).

Goessling, H. F., Rackow, T. & Jung, T. Recent global temperature surge intensified by record-low planetary albedo. Science 387, 68–73 (2025).

Mauritsen, T. et al. Earth’s energy imbalance more than doubled in recent decades. AGU Adv. 6, e2024AV001636 (2025).

Loeb, N. G. et al. Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093047 (2021).

Marti, F. et al. Monitoring global ocean heat content from space geodetic observations to estimate the Earth energy imbalance. State Planet 4-osr8, 3 (2024).

Kuhlbrodt, T., Swaminathan, R., Ceppi, P. & Wilder, T. A glimpse into the future: The 2023 ocean temperature and sea ice extremes in the context of longer-term climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 105, E474–E485 (2024).

World Meteorological Organization. El Niño/La Niña update June 2023 https://wmo.int/sites/default/files/2023-11/WMO_ENLN_Update-June2023_en.pdf. Accessed: 2026-01-07 (2023).

Raghuraman, S. P. et al. The 2023 global warming spike was driven by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 11275–11283 (2024).

Tsuchida, K., Kosaka, Y. & Minobe, S. The triple-dip La Niña was key to Earth’s extreme heat uptake in 2022–2023. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5597161/v1 (2025).

Cattiaux, J., Ribes, A. & Cariou, E. How extreme were daily global temperatures in 2023 and early 2024? Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110531 (2024).

Gyuleva, G., Knutti, R. & Sippel, S. Combination of internal variability and forced response reconciles observed 2023–2024 warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL115270 (2025).

Terhaar, J., Burger, F. A., Vogt, L., Frölicher, T. L. & Stocker, T. F. Record sea surface temperature jump in 2023-2024 unlikely but not unexpected. Nature 639, 942–946 (2025).

Schmidt, G. Climate models can’t explain 2023’s huge heat anomaly – we could be in uncharted territory. Nature 627, 467 (2024).

Min, S. K. Human influence can explain the widespread exceptional warmth in 2023. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024 5:1 5, 1–4 (2024).

Lindsey, R. Climate change: Incoming sunlight https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-incoming-sunlight Accessed: 2025-02-24 (2021).

Rantanen, M. & Laaksonen, A. The jump in global temperatures in September 2023 is extremely unlikely due to internal climate variability alone. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–4 (2024).

Jenkins, S., Smith, C., Allen, M. & Grainger, R. Tonga eruption increases chance of temporary surface temperature anomaly above 1.5°C. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 127–129 (2023).

Sellitto, P. et al. The unexpected radiative impact of the Hunga Tonga eruption of 15th January 2022. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–10 (2022).

Schoeberl, M. R. et al. Evolution of the climate forcing during the two years after the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 129, e2024JD041296 (2024).

Watson-Parris, D. et al. Surface temperature effects of recent reductions in shipping SO2 emissions are within internal variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 4443–4454 (2025).

Jordan, G. & Henry, M. IMO2020 regulations accelerate global warming by up to 3 years in UKESM1. Earth’s. Future 12, e2024EF005011 (2024).

Gettelman, A. et al. Has reducing ship emissions brought forward global warming? Geophys. Res. Lett. 51 (2024).

Quaglia, I. & Visioni, D. Modeling 2020 regulatory changes in international shipping emissions helps explain anomalous 2023 warming. Earth Syst. Dyn. 15, 1527–1541 (2024).

Yoshioka, M., Grosvenor, D. P., Booth, B. B. B., Morice, C. P. & Carslaw, K. S. Warming effects of reduced sulfur emissions from shipping. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 13681–13692 (2024).

Yuan, T. et al. Abrupt reduction in shipping emission as an inadvertent geoengineering termination shock produces substantial radiative warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Kusakabe, Y. & Takemura, T. Formation of the North Atlantic warming hole by reducing anthropogenic sulphate aerosols. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–9 (2023).

Hausfather, Z. & Forster, P. Analysis: How low-sulphur shipping rules are affecting global warming https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-how-low-sulphur-shipping-rules-are-affecting-global-warming/ Accessed: 2025-02-24 (2023).

Samset, B. H. et al. Climate impacts from a removal of anthropogenic aerosol emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1020–1029 (2018).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3571–3605 (2020).

Carton, J. A., Chepurin, G. A., Hackert, E. C. & Huang, B. Remarkable 2023 North Atlantic ocean warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL112551 (2025).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Bilbao, R., Donohoe, A. & Materia, S. Record warmth of 2023 and 2024 was highly predictable and resulted from ENSO transition and the Northern Hemisphere absorbed shortwave anomalies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL115614 (2025).

Xie, S. P. et al. What made 2023 and 2024 the hottest years in a row? npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025 8:1 8, 1–4 (2025).

Samset, B. H., Lund, M. T., Fuglestvedt, J. S. & Wilcox, L. J. 2023 temperatures reflect steady global warming and internal sea surface temperature variability. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024 5:1 5, 1–8 (2024).

Samset, B. H. et al. East Asian aerosol cleanup has likely contributed to the recent acceleration in global warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 543 (2025).

Hansen, J. E. et al. Global warming in the pipeline. Oxford Open Climate Change 3, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfclm/kgad008 (2023).

Lenssen, N. et al. A GISTEMPv4 observational uncertainty ensemble. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD040179 (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Soci, C. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis from 1940 to 2022. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 4014–4048 (2024).

Oldenborgh, G. J. V. et al. Defining El Niño indices in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 044003 (2021).

Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI). Climate explorer. https://climexp.knmi.nl/ Accessed: 2025-06-20.

Zhang, T. et al. Towards probabilistic multivariate ENSO monitoring. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10532–10540 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Brunner, L., Hauser, M., Lorenz, R. & Beyerle, U. The ETH Zurich CMIP6 next generation archive: technical documentation. ETH Zürich, Zürich 10, https://zenodo.org/records/3734128 (2020).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 169–180 (2017).

Rodgers, K. B. et al. Ubiquity of human-induced changes in climate variability. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1393–1411 (2021).

Wehrli, K., Guillod, B. P., Hauser, M., Leclair, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Assessing the dynamic versus thermodynamic origin of climate model biases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 8471–8479 (2018).

Wehrli, K., Guillod, B. P., Hauser, M., Leclair, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Identifying key driving processes of major recent heat waves. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 124, 11746–11765 (2019).

Schumacher, D. L., Hauser, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Drivers and mechanisms of the 2021 Pacific Northwest heatwave. Earth’s Future 10 (2022).

Hurrell, J. W., Hack, J. J., Shea, D., Caron, J. M. & Rosinski, J. A new sea surface temperature and sea ice boundary dataset for the Community Atmosphere Model. J. Clim. 21, 5145–5153 (2008).

Cleveland, W. S. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 74, 829–836 (1979).

Philip, S. et al. A protocol for probabilistic extreme event attribution analyses. Adv. Stat. Clim. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 6, 177–203 (2020).

Bartusek, S., Kornhuber, K. & Ting, M. 2021 North American heatwave amplified by climate change-driven nonlinear interactions. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1143–1150 (2022).

Hauser, M. et al. Methods and model dependency of extreme event attribution: The 2015 European drought. Earth’s. Future 5, 1034–1043 (2017).

Hauser, M. mathause/dist_cov: version 0.1.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7922002 (2023).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition (Pearson Education, London, England, 2013), 7edn.

O’Brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41, 673–690 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101003469 (XAIDA project). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme, which coordinated and promoted CMIP6. We thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output. We further acknowledge the CESM2 Large Ensemble Community Project and supercomputing resources provided by the IBS Center for Climate Physics in South Korea. We thank Urs Beyerle for downloading and curating the CMIP6 data at ETH Zurich, and Martin Hirschi for providing ECMWF data. We are also grateful to Mathias Hauser for developing the dist_cov package, which forms the basis of the probabilistic attribution analysis, and for providing guidance. We further thank Mika Rantanen and one anonymous reviewer for their constructive and helpful peer review, and the editor for their valuable guidance.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I.S. conceived the study. S.I.S. and D.L.S. designed the study. D.L.S. performed the CESM2 model simulation. Sv.S. conducted the main analysis, D.L.S. analysed the CESM2 output. D.L.S., S.I.S. and L.G. contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the results. Sv.S. wrote the initial draft; all authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Mika Rantanen and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joy Merwin Monteiro and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seeber, S., Schumacher, D.L., Gudmundsson, L. et al. The observed September 2023 temperature jump was nearly impossible under standard anthropogenic forcing. Commun Earth Environ (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03178-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03178-8