Abstract

The rapid emergence of combination pharmacotherapies offers substantial therapeutic advantages but also poses risks of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The accurate prediction of ADRs with interpretable computational methods is crucial for clinical medication management, drug development and precision medicine. Machine-learning and recently developed deep learning architectures struggle to effectively elucidate the key protein–protein interactions underlying ADRs from an organ perspective and to explicitly represent ADR associations. Here we propose OrganADR, an associative learning-enhanced model to predict ADRs at the organ level for emerging combination pharmacotherapy. It incorporates ADR information at the organ level, drug information at the molecular level and network-based biomedical knowledge into integrated representations with multi-interpretable modules. Evaluation across 15 organs demonstrates that OrganADR not only achieves state-of-the-art performance but also delivers both interpretable insights at the organ level and network-based perspectives. Overall, OrganADR represents a useful tool for cross-scale biomedical information integration and could be used to prevent ADRs during clinical precision medicine.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

This study utilizes TWOSIDES5 (https://tatonettilab.org/resources/tatonetti-stm.html), DrugBank26 (https://go.drugbank.com/releases/latest), Hetionet24 (https://github.com/hetio/hetionet), PrimeKG25 (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/IXA7BM) and ADReCS6 (https://bioinf.xmu.edu.cn/ADReCS/download.jsp) as raw data. The preprocessed data for training, validation and testing OrganADR and baseline models are available via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/15129153 (ref. 48). Source data are available with this paper.

Code availability

OrganADR (v.1.0.0) was developed to conduct data analysis, which is available via GitHub at https://github.com/BoyangLi-BIT/OrganADR (ref. 49) and Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/15129131 (ref. 48). Two-tailed hypothesis testing was performed using scipy.stats package (v.1.11.4) in Python (v.3.10.14).

Change history

30 July 2025

In the version of the article initially published, the Acknowledgements section omitted a funding resource, National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82202072). This is now amended in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Leinonen, H. et al. A combination treatment based on drug repurposing demonstrates mutation-agnostic efficacy in pre-clinical retinopathy models. Nat. Commun. 15, 5943 (2024).

Khunsriraksakul, C. et al. Integrating 3D genomic and epigenomic data to enhance target gene discovery and drug repurposing in transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Commun. 13, 3258 (2022).

Lim, G. B. Benefits of combination pharmacotherapy for HFrEF. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 455 (2020).

Jaaks, P. et al. Effective drug combinations in breast, colon and pancreatic cancer cells. Nature 603, 166–173 (2022).

Tatonetti, N. P., Ye, P. P., Daneshjou, R. & Altman, R. B. Data-driven prediction of drug effects and interactions. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 125ra31 (2012).

Yue, Q.-X. et al. Mining real-world big data to characterize adverse drug reaction quantitatively: mixed methods study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, 48572 (2024).

Bouvy, J. C., De Bruin, M. L. & Koopmanschap, M. A. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in europe: a review of recent observational studies. Drug Safety 38, 437–453 (2015).

Boland, M. R. et al. Systems biology approaches for identifying adverse drug reactions and elucidating their underlying biological mechanisms. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 8, 104–122 (2016).

Ivanov, S. M., Lagunin, A. A. & Poroikov, V. V. In silico assessment of adverse drug reactions and associated mechanisms. Drug Discov. Today 21, 58–71 (2016).

Skou, S. T. et al. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 8, 48 (2022).

Dewulf, P., Stock, M. & De Baets, B. Cold-start problems in data-driven prediction of drug–drug interaction effects. Pharmaceuticals 14, 429 (2021).

Lee, C. Y. & Chen, Y.-P. P. Machine learning on adverse drug reactions for pharmacovigilance. Drug Discov. Today 24, 1332–1343 (2019).

Lee, C. Y. & Chen, Y.-P. P. Prediction of drug adverse events using deep learning in pharmaceutical discovery. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 1884–1901 (2021).

Rezaei, Z., Ebrahimpour-Komleh, H., Eslami, B., Chavoshinejad, R. & Totonchi, M. Adverse drug reaction detection in social media by deep learning methods. Cell J. 22, 319 (2020).

Zhao, H. et al. Identifying the serious clinical outcomes of adverse reactions to drugs by a multi-task deep learning framework. Commun. Biol. 6, 870 (2023).

Zitnik, M., Agrawal, M. & Leskovec, J. Modeling polypharmacy side effects with graph convolutional networks. Bioinformatics 34, 457–466 (2018).

Karim, M. R. et al. Drug–drug interaction prediction based on knowledge graph embeddings and convolutional-lstm network. In Proc. 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics (eds Shi, X. & Buck, M.) 113–123 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Sumgnn: multi-typed drug interaction prediction via efficient knowledge graph summarization. Bioinformatics 37, 2988–2995 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Emerging drug interaction prediction enabled by a flow-based graph neural network with biomedical network. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 1023–1033 (2023).

Wan, G. et al. Multi-organ immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors and their downstream implications: a retrospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol. 25, 1053–1069 (2024).

Langenberg, C., Hingorani, A. D. & Whitty, C. J. Biological and functional multimorbidity-from mechanisms to management. Nat. Med. 29, 1649–1657 (2023).

Lesort, T., George, T. & Rish, I. Continual learning in deep networks: an analysis of the last layer. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.01834 (2021).

Xi, X., Gao, F., Xu, J., Guo, F. & Jin, T. Modeling output-level task relatedness in multi-task learning with feedback mechanism. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.00885 (2024).

Himmelstein, D. S. et al. Systematic integration of biomedical knowledge prioritizes drugs for repurposing. eLife 6, 26726 (2017).

Chandak, P., Huang, K. & Zitnik, M. Building a knowledge graph to enable precision medicine. Sci. Data 10, 67 (2023).

Knox, C. et al. Drugbank 6.0: the drugbank knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, 1265–1275 (2024).

Buning, J. W. et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral hydrocortisone—results and implications from a randomized controlled trial. Metabolism 71, 7–16 (2017).

Nguewa, P. A. et al. Pentamidine is an antiparasitic and apoptotic drug that selectively modifies ubiquitin. Chem. Biodivers. 2, 1387–1400 (2005).

Wood, G., Wetzig, N., Hogan, P. & Whitby, M. Survival from pentamidine induced pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 21, 341–342 (1991).

Buchman, A. L. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 33, 289–294 (2001).

Davies, N. M. & Anderson, K. E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of diclofenac: therapeutic insights and pitfalls. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 33, 184–213 (1997).

Anstey, A. & Lear, J. T. Azathioprine: clinical pharmacology and current indications in autoimmune disorders. BioDrugs 9, 33–47 (1998).

Mozayani, A. & Raymon, L. A. Handbook of Drug Interactions: A Clinical and Forensic Guide (Springer, 2011).

Heymann, R. E. et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled study of amitriptyline, nortriptyline and placebo in patients with fibromyalgia. an analysis of outcome measures. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 19, 697–702 (2001).

Mamoshina, P., Rodriguez, B. & Bueno-Orovio, A. Toward a broader view of mechanisms of drug cardiotoxicity. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100216 (2021).

Clewell, H. J. et al. Review and evaluation of the potential impact of age-and gender-specific pharmacokinetic differences on tissue dosimetry. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 32, 329–389 (2002).

Ye, L., Hou, C. & Liu, S. The role of metabolizing enzymes and transporters in antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 17, 340–360 (2017).

Scarlett, Y. Medical management of fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 126, 55–63 (2004).

Ereshefsky, L. & Sloan, D. Drug–drug interactions with the use of psychotropic medications. CNS Spectr. 14, 1–8 (2009).

Tanvir, F., Islam, M. I. K. & Akbas, E. Predicting drug–drug interactions using meta-path based similarities. In Proc. 2021 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (eds Hallinan, J. et al.) 1–8 (IEEE, 2021).

Jiang, H. et al. Adverse drug reactions and correlations with drug–drug interactions: a retrospective study of reports from 2011 to 2020. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 923939 (2022).

Roitmann, E., Eriksson, R. & Brunak, S. Patient stratification and identification of adverse event correlations in the space of 1190 drug related adverse events. Front. Physiol. 5, 332 (2014).

King, C. et al. Pharmacogenomic associations of adverse drug reactions in asthma: systematic review and research prioritisation. Pharmacogenomics J. 20, 621–628 (2020).

Özçelik, R., Ruiter, S., Criscuolo, E. & Grisoni, F. Chemical language modeling with structured state space sequence models. Nat. Commun. 15, 6176 (2024).

Zheng, S. et al. Pharmkg: a dedicated knowledge graph benchmark for bomedical data mining. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 344 (2021).

Dong, J., Liu, J., Wei, Y., Huang, P. & Wu, Q. Megakg: toward an explainable knowledge graph for early drug development. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.27.586981 (2024).

Brown, E. G., Wood, L. & Wood, S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (meddra). Drug Safety 20, 109–117 (1999).

Li, B., Qi, Y., Li, B. & Li, X. OrganADR_Data_20250403. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15129153 (2025).

Li, B., Qi, Y., Li, B. & Li, X. OrganADR_Code_20250403. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15129131 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82202072). This project is also supported by Beijing Institute of Technology Science and Technology Innovation Plan (grant no. LY2023-32) and Beijing Institute of Technology Science and Technology Innovation Plan, Science and Technology Support Special Program (grant no. 2024CX02046).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bo Li and X.L. conceived the idea and guided the research. Boyang Li developed the model. Bo Li and Boyang Li wrote the manuscript. Boyang Li and Y.Q. contributed to algorithm implementation and results analysis. Bo Li and X.L. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Computational Science thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Kaitlin McCardle, in collaboration with the Nature Computational Science team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

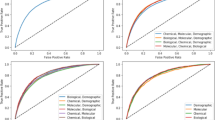

Extended Data Fig. 1 Ablation study and performance with different ADRs’ association matrices and imbalanced datasets.

a, Ablation study of the ADRs’ association matrix and corresponding modules. Minima, maxima, mean and P-value are shown. Sample size is 100. Two-tailed paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test are conducted (determined by normality assessment via Shapiro-Wilk test) using scipy.stats package (version 1.11.4) in Python (version 3.10.14). b, Performance comparison under different ADRs’ association matrices. Sample size is 12. c, OrganADR’s ROC-AUC and accuracy under imbalanced datasets. For x = 0.25, 0.33, 0.67, 0.75, 1.33, 1.5, 3 and 4, sample size is 5. For x = 0.5 and 2, sample size is 10. For x = 1, sample size is 20. For b and c, central line (median), box boundaries (25th-75th percentiles), whiskers extending to minima/maxima within 1.5 interquartile range (IQR) are shown. Outliers are shown as hollow circles.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sects. 1 and 2, Figs. 1–52 and Tables 1–35.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 3.

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4.

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5.

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6.

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1.

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Qi, Y., Li, B. et al. Predicting adverse drug reactions for combination pharmacotherapy with cross-scale associative learning via attention modules. Nat Comput Sci 5, 547–561 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00816-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00816-7