Abstract

As quantum hardware advances toward enabling error-corrected quantum circuits in the near future, the absence of an efficient polynomial-time decoding algorithm for logical circuits presents a critical bottleneck. While quantum memory decoding has been well studied, inevitable correlated errors introduced by transversal entangling logical gates prevent the straightforward generalization of quantum memory decoders. Here we introduce a data-centric, modular decoder framework, the Multi-Core Circuit Decoder (MCCD), which consists of decoder modules corresponding to each logical operation supported by the quantum hardware. The MCCD handles both single-qubit and entangling gates within a unified framework. We train MCCD using mirror-symmetric random Clifford circuits, demonstrating its ability to effectively learn correlated decoding patterns. Through extensive testing on circuits substantially deeper than those used in training, we show that MCCD maintains high logical accuracy while exhibiting competitive polynomial decoding time across increasing circuit depths and code distances. When compared with conventional decoders such as minimum weight perfect matching (MWPM), most likely error (MLE) and belief propagation with ordered statistics post-processing (BP-OSD), MCCD achieves competitive accuracy with substantially better time efficiency, particularly for circuits with entangling gates. Our approach provides a noise-model-agnostic solution to the decoding challenge in deep logical quantum circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recent experimental breakthroughs bring the prospect of logical circuits with quantum error correction to the near future1,2,3. Quantum error correction codes protect logical information by encoding a logical qubit into multiple physical qubits and correcting when the logical information is corrupted. The error syndromes from sequential pairs of stabilizer measurements must be processed by a decoder to determine when a logical error occurs4,5,6,7. However, decoding is itself a challenging task for classical computers. For instance, calculating the most likely error (MLE) in general is a nondeterministic polynomial time (NP)-hard problem8,9 for the surface code10. While solving an NP-hard problem exactly is often infeasible, extensive research has focused on developing efficient approximate decoding strategies. Conventional approaches construct decoding graphs specific to assumed noise model priors and leverage the available efficient graph solvers11,12. However, correlated errors introduce hyperedges that are beyond the reach of matching-based graph solvers13,14 without noise model-driven decomposition15,16,17,18. Because errors inevitably propagate between logical qubits under entangling logical gates, the challenge of correlated errors becomes a key bottleneck issue for decoding logical circuit operations. Hence, an effective, noise-model-agnostic decoder for logical circuits—capable of addressing correlated errors—is critical for generating entangled, fault-tolerant states.

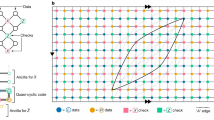

From a data-centric perspective, the objective of a decoder is to determine whether a given syndrome arises from a logical error (Fig. 1a). The challenge is that many physical error configurations manifest an identical syndrome. Conventional algorithmic approaches head-on face the underconstrained inverse problem by manually deriving a probabilistic model for the physical error configurations associated with a given syndrome, relying on the noise model. Driven by the need for noise-model-agnostic and scalable decoders, there have been efforts to develop machine learning (ML)-based decoders. ML decoders frame decoding as a classification problem, aiming directly at the binary prediction of logical error occurrence. By avoiding explicit reconstruction of physical errors, the ML decoder can be more scalable than conventional approaches. Most importantly, ML decoders learn noise from data. The benefits of this noise-model-agnostic approach are twofold. First, it frees ML-based decoders from assumptions embedded in specific noise models. As demonstrated by Varbanov et al.19, the ML-based memory decoder remains robust with increasing Y error rate, a regime where the minimum weight perfect matching (MWPM) performance clearly worsens. Second, it avoids degradation in decoding accuracy20 due to mismatches between the physical noise process \({\mathcal{N}}\) and the assumed prior noise model for the decoder \(\tilde{{\mathcal{N}}}\) (Fig. 1a). However, most ML-decoder efforts have been limited to decoding a single logical qubit, such as a quantum memory19,20,21,22,23,24 or a qubit under single-qubit logical operations3. Here, we develop a modular Multi-Core Circuit Decoder (MCCD) custom-designed from a data-centric perspective (Fig. 1b,c) and demonstrate its efficacy on data from random Clifford circuits simulated with a realistic noise level. We find that MCCD successfully learns to decode correlated errors from a general circuit, demonstrating favorable linear scaling of wall time with circuit depth. Descriptions of the MCCD architecture (Fig. 2), training procedures and numerical details are presented in Methods.

a, Decoding can be framed as a binary classification task. On a physical level, the device noise \({\mathcal{N}}\) causes physical errors, and we detect them by measuring stabilizers, which give rise to error syndromes. Each error syndrome (blue squares for violated Z stabilizers) can result from two classes of X errors: class ‘0’ errors preserve the logical Z, while class ‘1’ errors flip it. Conventional algorithmic decoders infer physical errors from syndromes using the error probability \({p}_{\tilde{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) under a prior noise model \(\tilde{{\mathcal{N}}}\). By contrast, a pretrained ML decoder directly classifies the syndrome as logical 0 or 1. b, A sketch of the logical circuit that prepares a logical Bell pair. H and I correspond to the Hadamard and identity logical operations, respectively. Both logical qubits are initialized in \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}\) state in logical Z basis. The black squares represent quantum error correction (QEC) rounds where stabilizers are measured. Syndromes are constructed from neighboring stabilizer measurements. \({S}_{t}^{(i)}\) refers to the syndromes of logical qubit i at the tth QEC cycle. c, An ML decoder takes sequences of syndromes from different logical qubits and predicts whether a logical error happened for each logical qubit, denoted as \({\mathbf{y}}_{z}^{(i)}\) for logical qubit i. Our ML-based decoder is composed of a decoding module network that parallels the corresponding logical circuits. Prob, probability. d, Entangling logical operations propagates physical error from one logical qubit to the other. As marked by the red lines, a physical X error on the control logical qubit (top) can propagate through a logical CNOT gate to the target logical qubit (bottom). The syndromes of control and target qubit are correlated, and both reflect the original physical X error in the control qubit.

a, For each element in the gate set, we train a separate decoder module. There is a one-to-one mapping between the logical gates (left box) to the ML decoder module (right box). b, Single-qubit decoder module inner structure based on an LSTM core. The hidden state Ht−1 = ct−1, ht−1 (we omit superscript (q)), has two components ct−1 and ht−1, which are designed to keep track of long-term and short-term history correspondingly. Together with the new syndrome St, Ht−1 follows the internal information flow as shown in the box and outputs the updated hidden state Ht. The red-boxed operations represent a linear layer followed by corresponding activation functions (sigmoid σ and \(\tanh\)). The blue circled operations represent element-wise addition (+), multiplication (×) and \(\tanh\). c, To handle correlated decoding, we use a module that input the hidden states \({H}_{t-1}^{(C)},{H}_{t-1}^{(T)}\) and new syndromes \({S}_{t}^{(C)},{S}_{t}^{(T)}\) from both control (C) and target (T) logical qubits. The hidden states are updated simultaneously.

Results

We first train and test MCCD on simulated data from Circuit Type I with only single-qubit gates (Fig. 3a,b). Although training was limited to the circuits of depths up to D = 10, neither the logical accuracy (Fig. 4a,b) nor the wall time (Fig. 4c,d) show any sign of deterioration upon crossing the training depth limit of D = 10. This indicates that MCCD is indeed capable of decoding circuits much deeper than those used for training. Comparison of MCCD performances between code distances d = 3 (Fig. 4a) and d = 5 (Fig. 4b), the improved accuracy of MCCD upon increasing the code distance is consistent with the expected behavior when the noise level, motivated by the experiments2, is below the MCCD’s decoding threshold. Most remarkably, MCCD maintains lower wall time than other decoders as the code distance or circuit depth increases (Fig. 4c,d).

a, A mirror symmetric circuit can be generated for an arbitrary circuit U by concatenating a reversed circuit U† after the forward evolution U. The tilde in \(\tilde{U}\) highlights the existence of noise. In the noiseless limit, the mirror symmetry circuit UU† applied on some initial state \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) should keep the state untouched. Due to the noise, \(\tilde{U}{\tilde{U}}^{\dagger }\left\vert \psi \right\rangle =\left\vert \tilde{\psi }\right\rangle \approx \left\vert \psi \right\rangle\). b, An example of \(\tilde{U}\) sampled from Circuit Type I. c, An example of \(\tilde{U}\) sampled from Circuit Type II.

a,b, Logical accuracy versus circuit depth using surface code with code distance d = 3 (a) and d = 5 (b) for MCCD (red), MLE (orange), BP-OSD (green) and MWPM (blue) decoders. c,d, Wall time taken to decode one syndrome trajectory in log scale with increasing circuit depth for a d = 3 (c) and d = 5 (d) surface code. We evaluate each decoder over 20 independent runs. In each run, we randomly sample 1,000 syndrome trajectories from Type I circuits and average them to obtain a run-level performance estimate. We report the mean across the 20 runs, with error bars showing s.e.m.

When comparing the logical accuracies of the reference decoders for the two code distances d = 3 and d = 5, clearly the noise level of the data is below the error threshold for all the decoders under consideration. Because MLE considers all possible error patterns, it achieves higher accuracy, especially at deeper circuits (Fig. 4a,b). However, this accuracy is achieved at the cost of exponentially increasing wall time (Fig. 4c,d). Meanwhile, while MWPM runs at high speed (Fig. 4c,d), it shows notably lower accuracy compared with MCCD (Fig. 4a,b). Belief propagation with ordered statistics post-processing (BP-OSD) offers better accuracy than MWPM, but its wall time increases sharply with circuit depth for code distance d = 5. In comparison, MCCD shows competitive accuracy with a linear-in-depth wall time scaling.

Inclusion of entangling logical gates, which drastically increases correlated errors, can deteriorate performance and lower the decoding threshold to varying extents for different decoders. Here, we demonstrate that MCCD’s performance remains robust even after the inclusion of entangling logical gates. Building on the above encouraging results on the data from Type I circuits, we follow a curriculum learning approach25 to train an extra module for the logical CNOT gate while keeping single-qubit gate decoder modules and the readout network fixed. To generate diverse training data that include two-qubit logical gates, we sample mirror-symmetric logical circuits sampled from Circuit Type II (Fig. 3a,c). As shown through the improvements in the logical accuracy upon increasing the code distance in Fig. 5a,b, MCCD’s decoding threshold for Type II circuits, which requires correlated decoding, is still above the realistic noise level of our simulated data. Furthermore, our exploration of different noise models showed that MCCD works robustly across different noise models and learns nuanced features of the noise model from data (see Supplementary Section E1 for more details). This extended study used independent training of multiple MCCDs using training data simulated with three different noise models and validation using syndrome data generated with an experimentally motivated noise model. Most importantly, the MCCD’s wall time remains practically linear as a function of circuit depth, even with the correlated errors due to the entangling gates.

a,b, Logical accuracy versus circuit depth using surface code with code distance d = 3 (a) and d = 5 (b) for MCCD (red), MLE (orange) and BP-OSD (green) decoders. c,d, Wall time taken to decode one syndrome trajectory in log scale with increasing circuit depth for a d = 3 (c) and d = 5 (d) surface code. The inset in d shows a zoomed-in view of computing time for the ML decoder in a linear scale. We evaluate each decoder over 20 independent runs. In each run, we randomly sample 1,000 syndrome trajectories from Type II circuits and average them to obtain a run-level performance estimate. We report the mean across the 20 runs, with error bars showing s.e.m.

By contrast, the MWPM, which is comparable to our MCCD in terms of speed for Circuit Type I, is incapable of handling correlated errors in the Circuit Type II data. Hence, we limit the comparison in Fig. 5 to MLE14 and BP-OSD26,27. Unsurprisingly, MLE shows higher accuracy. However, once again, the exponential cost of MLE14 is prohibitively high. While BP-OSD is faster than MLE at low circuit depth, its wall time rapidly increases with circuit depth at code distance d = 5. Hence, MCCD with linear complexity O(D) for the logical circuit of depth D clearly outperforms the conventional decoders in running time, especially in the large depth region.

Note

Toward the conclusion of this work, we became aware of a recent study3 that used a similar approach to train a neural network decoder for the color code, demonstrating its effectiveness on single-qubit Clifford logical circuits. Recent works that appeared after the initial submission of this work extended matching-based approaches for logical circuit decoding28,29. Our benchmarking study shown in Supplementary Section II finds that MCCD achieves higher decoding accuracy than the LoMatching algorithm introduced by Serra-Peralta et al.29. As in the comparison between MCCD and MWPM for Type I circuits, the matching approach offers greater speed at the cost of reduced accuracy. Incorporating Pauli product decoding by modifying MCCD to reduce its computational load represents a promising direction for future work.

Discussion

In summary, we introduced the pretrainable and modular MCCD along with an efficient training scheme, presenting a ML-based decoder that effectively addresses the challenge of decoding logical quantum circuits with correlated errors. Utilizing a data-centric ML approach with dedicated processing cells (PCs) for each gate type, our decoder effectively captures error propagation through both single-qubit and entangling logical operations. The MCCD’s performance demonstrates three key advantages: (1) noise-model agnosticism that allows application to various quantum hardware platforms without detailed knowledge of underlying noise characteristics, (2) high decoding accuracy competitive with conventional decoders and (3) remarkable practical run time efficiency and promising complexity scaling with circuit depth. This linear scaling behavior with a small prefactor makes MCCD particularly suitable for real-time decoding in practical quantum computing environments with deep logical circuits. Furthermore, our modular design enables straightforward extension to new gate sets or improved physical implementations of existing gates as quantum hardware evolves. The combination of accuracy, speed and adaptability positions MCCD as a promising approach for facilitating the path toward fault-tolerant quantum computation.

Interesting directions of future work include the extension of MCCD to include mid-circuit measurement and feedforward operations30, as well as scaling to larger code distances. While we focused on the transversal implementation of logical Clifford gate6,31,32 in this work, the inherent flexibility of MCCD allows for extending the set of logical operations. Such extension will open doors to teleportation-based implementation of non-Clifford logical gates33,34,35 and lattice surgery implementation of entangling gates36,37.

While current experimental demonstrations of error-corrected logical circuits are limited to relatively small code distances2—making MCCD immediately useful—scaling up the code distance will be necessary for real-time decoding of fault-tolerant deep logical circuits. While the results presented in this work already show that MCCD scales favorably with circuit depth, scaling up the code distance will address three potential challenges. First is the practical challenge of needing a large volume of randomized logical circuit simulation data. Leveraging graphics processing unit-accelerated Clifford simulation and parallelization will be helpful (Supplementary Section III and Supplementary Fig. 5). The second challenge is working with the larger dimension of syndrome data for a larger code. Strategies developed by the ML community for increasing the syntax window for large language models could be productive, as the syndrome sequence is a time sequence. Improving the design of each core by utilizing a more effective scaling attention mechanism and incorporating physical knowledge to sparsify attention could be promising. The third challenge is training with increasingly rare events, as logical error rates decrease with increasing code distance. Again, we can leverage the extensive research on training with imbalanced data in the ML community. Transfer learning by initializing training on a small code distance with a larger logical error rate and oversampling rare or ambiguous cases could be a promising strategy. Furthermore, strategic adoption of progress in language models can enable expansion of the syndrome time window of MCCD to capture longer time-scale temporal correlations.

Methods

At a high level, the syndrome data consist of time sequences, each associated with a logical qubit from quantum error correction rounds. Accumulation of physical noise in each individual code block introduces intrasequence time correlations. Without gate operations, each time sequence will be independently time-translation invariant. This structure motivates the usage of a recurrent structure with a hidden state for each logical qubit to capture temporal correlations. Indeed, a recurrent neural network38 with a single recurrent cell was proposed for decoding quantum memory22. Our goal of developing a versatile logical circuit decoder introduces three new challenges: (1) time-translation invariance is broken with gate operations, (2) entangling gates introduce intersequence correlations (Fig. 1d) and (3) the decoder should be able to handle any circuits built with a fixed gate set. The MCCD tackles all three challenges in one swoop by using multiple PCs, one dedicated PC for each logical gate in the gate set (Fig. 2a). The MCCD handles single-qubit logical gates and entangling logical gates on equal footing by simply feeding syndrome data into the corresponding recurrent cell as the data are collected. The only assumption the MCCD makes is the existence of a native logical gate set for a given quantum hardware, which is a universal assumption for digital quantum computers.

Specifically, the MCCD uses one time-dependent hidden state \({H}_{t}^{(q)}\) per logical qubit q to capture its error history and multiple PCs, one for each gate, to build a modularized decoder. The hidden states serve as a memory to keep track of the error history. The PCs and the readout network are trained for a fixed gate set. To decode deep logical circuits, we design each PC based on the recurrent cell of long short-term memory39, which avoids the vanishing gradient problem of standard recurrent neural networks when processing long sequences. This choice is inspired by the successful memory decoding of up to hundreds of quantum error correction rounds using a long short-term memory architecture for a surface code22. Hence each hidden state Ht−1 = (ct−1, ht−1) has two components, ct−1 and ht−1, which track long-term and short-term history, correspondingly.

Before the logical circuit starts to run, we initialize the hidden states \({H}_{0}^{(q)}\) to all zeros for each logical qubit q. When each logical gate is applied at time t and a new round of syndrome St is extracted, we feed the hidden state Ht−1 and the syndrome data St to the gate-specific PC for the cell to output an updated hidden state Ht. The PC for an entangling logical gate must capture the physical process of error propagation through the entangling operation. For this, this PC is designed to take hidden states and syndromes from both logical qubits (for example, the control and target qubits in the case of CNOT gates in Fig. 2c) as inputs and update the two hidden states simultaneously (Fig. 2c). The hidden states provide error history information, while the new syndromes introduce information regarding new physical errors, both of which are necessary for correlated decoding. Finally, a trainable readout network maps the final hidden state to the logical error prediction output \({\mathbf{y}}_{Z}^{(q)}\). To improve performance, we provide the readout network with the final round syndrome measurement constructed from the data-qubit measurement in addition to the hidden state (only half of the stabilizers can be constructed depending on the measurement basis of the data qubits).

For MCCD to be effective, the training must be driven by a physically meaningful loss function and diverse training data that avoid overfitting. We use a training scheme inspired by logical randomized benchmarking40, as random circuits can prevent MCCD from learning subtle fingerprints of specific circuits used in training. We overcome the difficulty of defining a universal loss function while using random circuits by using mirror-symmetric circuits that evolve a state forward by a random unitary U composed of logical gates in the gate set and then backward by U†, as shown in Fig. 3a. As noiseless implementation of U and U† should keep the initial state unchanged, the differences between the final logical measurements and the initial logical preparation offer ground-truth training labels. Therefore, we use the cross-entropy between the model outputs and training labels in these mirror-symmetric circuits as the loss function to guide the training of the MCCD. To ensure diversity in the training data, we opt for a hardware-efficient implementation of random unitaries. Finally, to ensure that MCCD’s training generalizes to new circuits, we train MCCD with data from logical circuit depth D = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (D = 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20) and test the model on a wide range of unseen circuits with depth up to D = 18 (D = 36) for Circuit Type I (Circuit Type II), defined below.

We demonstrate the efficacy and versatility of MCCD by testing MCCD on two types of mirror-symmetric random logical circuit:

-

Circuit Type I: single-qubit-only logical circuits on each logical qubit. We sample a sequence of random single-qubit gates from the gate set {I, X, Y, Z, H}, followed by the sequence in the reverse order (Fig. 3b).

-

Circuit Type II: random scrambling logical circuit, consists of interlacing layers of single- and two-qubit gates. Each single-qubit gate layer contains randomly sampled gates from the gate set {I, X, Y, Z, H}. Each two-qubit gate layer consists of CNOT gates entangling random pairs of logical qubits; each logical qubit is acted on by only one CNOT. Again, the mirror symmetry is enforced by running the gate sequences in reverse order (Fig. 3c).

We generated the training data using the stim package41 to simulate the logical circuits based on surface code with the circuit-level noise model motivated by the experimental noise in neutral-atom platforms2,14. See the ‘Data generation’ subsection for the details of the simulation and the circuit-level noise model. Dividing our study into the above two circuit types achieves two goals. First, it allows us to benchmark against conventional methods on the easier task of decoding circuits (Type I) without correlated error. Second, it allows us to use a resource-efficient curriculum training strategy25. Specifically, the initial phase of training uses Type I circuits, allowing training on data that are cheaper to generate. The resulting modules then serve as initialization for more complicated Type II circuits, focusing training effort on capturing correlated error structures induced by entangling logical gates, which are not present in Type I circuits, while optimizing for lower overall data generation costs.

A meritorious decoder must optimize between two competing needs: accuracy and speed. While a high accuracy is desired, when a decoder’s speed lags behind the clock cycle of the quantum computer, it will add a crippling burden. Hence, we benchmark the performance of MCCD from two perspectives—logical accuracy and wall time—against three established conventional decoders. Specifically, we consider three popular algorithmic decoders: MWPM12,42, MLE14 and BP-OSD26,27. We compare the decoder performances in decoding logical circuits built using surface code-based logical qubits with two different code distances d = 3 and 5 and transversal logical Clifford gates, including {I, X, Y, Z, H, CNOT}. See the ‘Logical gate implementations’ subsection for details about how the transversal logical operations are implemented on a physical level. We note that, in the following numerical demonstrations of algorithmic decoders, we consider an optimal decoder prior that exactly matches the noise model used in logical circuit simulations, that is, \(\tilde{{\mathcal{N}}}={\mathcal{N}}\). Therefore, the performances of conventional decoders represent an upper bound of what one can get in practice, as full knowledge of the physical noise model is inaccessible in a realistic setup.

Architecture

Our modular ML-based decoder consists of three types of module: (1) decoder modules for single-qubit logical operations, (2) a decoder module for the entangling logical operation and (3) a readout module in the logical Z basis. We consider measurements in the Z logical basis to demonstrate the efficacy of our modular ML-based decoder. However, one can handle the X basis logical measurements by either replacing the X logical measurement with an \(\bar{H}\) followed by a logical Z measurement using our pretrained decoder modules, or train an extra readout network for X logical measurements. In the following, we discuss the architecture of the three types of module.

Decoder modules for single-qubit logical operations

To effectively learn how to decode logical circuits, we observe that different logical operations transform error history differently and potentially introduce various types of physical error depending on the physical implementation of the logical gate. Therefore, we need to train a separate decoder module for each distinct logical operation. We utilize different recurrent modules to process the hidden state of a surface code at a specific time point, according to the gate operation at that time point. Therefore, the number of single-qubit LSTM modules needed is equal to the number of different single-qubit gates in the circuit. Each single-qubit LSTM module takes the hidden state from the previous time step and outputs the hidden state for the next time step.

We use an LSTM cell with two layers in the single-qubit decoder modules. Mathematically, each layer in the LSTM module processes the hidden state at time step t in the following way:

In the context of our logical circuit decoder, xt is the new syndrome obtained at the current time step; ct−1 and ht−1 together, Ht−1 = (ct−1, ht−1), is the hidden state of the logical qubit in the previous time step t − 1. The output of the module is an updated hidden state Ht = (ct, ht).

Unlike regular recurrent neural networks, LSTMs introduce a memory cell (ct) that allows information to be stored over long sequences. Three gates control the memory cell: forget gate, input gate and output gate, which decide what information should be removed from the memory cell, added to the memory and passed to the next step, respectively.

The input to the model contains three parts: ht, the hidden state (short-term memory) at time step t; xt, the input at time step t, corresponding to the syndrome measurement in our decoding problem; and ct, the cell state (long-term memory) for the recurrent neural network core. The weight (W) and bias (b) matrices for each gate are multiplied by xt and ht to control how the next step is updated. The output from the LSTM module contains two parts: an updated hidden state for the next time step ht+1 and an updated cell state ct+1. We use only the hidden state from the output of the previous module as the input hidden state for the next module. Because we use different single-qubit LSTM modules for each time step, depending on the single-qubit gate, the recurrent structure differs from the traditional recurrent LSTM core.

Two-qubit LSTM module

To model the entanglement through a two-qubit gate between two previously noncorrelated surface codes, we introduce the two-qubit LSTM module from the onset of entanglement.

The input of the two-qubit LSTM module is the concatenated hidden state from the two separate codes. Because the physical gate operation on the qubits is not symmetrical, we need to keep the order of concatenation consistent with the order of the gate operation. For the sake of simplicity, we always put the hidden state with the control qubit in the first place. As we are using the same architecture for the two-qubit operation, the two-qubit hidden state is transformed similarly to the single-qubit hidden state. The difference is that the dimension of the hidden state is twice as large. From the output of the two-qubit LSTM module, we split the final hidden state into two in the hidden dimension; we then take the first one as the updated hidden state for the surface code containing the control qubit and the other half as the updated hidden state for the surface code with the target qubit.

Auxiliary readout

The auxiliary readout module aims to output the probability of error for a logical qubit. It consists of two linear layers connected by ReLU activation between them. Because we are dealing with multiple logical qubits, we process the single logical qubit hidden state first and concatenate after the readout module. We use the same linear layers for different types of logical qubit, but process them accordingly before the readout.

Main readout

Similar to the auxiliary readout module, the main readout also serves as a classification module, outputting the error probability of the current logical qubit. The difference lies in the input. The syndrome measurement from the final round, which contains only half of the stabilizers constructed from the final data qubit measurements, is concatenated to the hidden state representation before being fed into the main readout.

Loss function

The total loss of our decoder is a weighted sum of the cross-entropy losses of the main and auxiliary readout modules. We choose to weight the auxiliary loss by a factor of 0.5 (ref. 19).

MCCD training

Training pipeline

There are two intertwined tasks in the error correction for the correlated surface code problem: gate-dependent error correction for single qubits and correlated error correction for two qubits for the CNOT gate. We observe that separating the two tasks and training the model sequentially on the two types of module makes the learning process easier, leading to promising results. Therefore, we use a two-stage training strategy, where we first train the single-qubit-related modules in Circuit Type I and then train the two-qubit LSTM core exclusively in Circuit Type II. In the first stage of training, we optimize parameters in all the single-qubit-related modules. These include all recurrent LSTM modules for single-qubit operations, the main readout and the auxiliary readout. After the single-qubit modules are thoroughly trained, we introduce the two-qubit module into the architecture and freeze everything else except the two-qubit PC, which takes the hidden states of the two entangled logical qubits.

Training hyperparameters

The detailed hyperparameters used in the network for training an MCCD for code distances d = 3 and d = 5 are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The hyperparameters used in training are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Please also see the published code (https://github.com/KimGroup/MCCD.git).

Data generation

The surface code

We consider a rotated surface code. An illustration of the code layout is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Logical gate implementations

We focus on Clifford logical gates with transversal implementations in this work. For clarity, in this section only, we denote logical operations with an overbar, \(\bar{U}\) and physical operations without an overbar U.

For single-qubit logical operations, we consider \(\bar{U}\in \{\bar{I},\bar{X},\bar{Y},\bar{Z},\bar{H}\}\). Each single-qubit logical gate \(\bar{U}\) corresponds to a depth-1 physical circuit where each physical qubit is acted on by physical gate U. The Hadamard gate \(\bar{H}\) swaps the \(\bar{Z}\) and \(\bar{X}\) basis, which requires rotating the surface code after applying H on all physical qubits. This rotation can be done ‘virtually’ by keeping track of the rotation on classical software, so that it can be done effectively and noiselessly on the quantum hardware.

For the two-qubit gate, we consider the CNOT gate, also implemented as a transversal operation. Physically, the two surface codes are moved to adjacency and physical CNOT gates are applied pairwise on the physical qubits between the control and target logical qubits.

Stabilizer measurement physical circuits

The stabilizer measurement circuit couples data qubits with the ancilla qubits. Measuring the ancilla qubits gives us the stabilizer measurement records, which are further processed to obtain syndromes and input into our ML decoder model. This circuit, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2, is applied after each logical gate operation.

Experimentally motivated noise model

For the numerical studies presented in the ‘Results’ section, we use the stim package for simulation. We consider a circuit-level noise model motivated by the current experimental capability of neutral atom array-based quantum computers. Specifically, we use a circuit-level noise model that includes the following physical noises:

-

Each two-qubit physical gate is followed by a two-qubit Pauli noise channel with probability [0.0005, 0.00175, 0.000625, 0.0005, 0, 0, 0, 0.00175, 0, 0, 0, 0.000625, 0, 0, 0.00125]

-

Each single-qubit physical gate is followed by a single-qubit depolarizing model with probability [0.0001, 0.0001, 0.0001]

-

On a physical level, the atoms are moved to achieve flexible connectivity between different physical qubits. This comes at the cost of having idling error due to the extra time taken during the physical qubit movement, which is captured as a Pauli noise channel with probability [4 × 10−7, 4 × 10−7, 1.6 × 10−6]. This error channel is applied when physical qubit movement happens.

-

Resetting a physical qubit has a bit flip error probability of P = 0.002.

-

Measuring a physical qubit has a bit flip error probability of P = 0.002.

Other decoders

We benchmark MCCD against three popular decoders: MLE, BP-OSD and MWPM. Here, we specify the numerical details of these methods.

MWPM

We use the open-source library PyMatching42 with the noise model used for data generation as detailed in the ‘Experimentally motivated noise model’ subsection.

BP-OSD

We use the open-source library stimbposd43. We use the exact noise model used for data generation and set the maximal belief propagation iterations to 20.

MLE

We use the algorithm developed and implemented as in ref. 14.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. These data are also available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196063 (ref. 44). The datasets used in this study were generated through quantum circuit simulations using the stim package with experimentally motivated noise models for neutral atom array-based quantum computers, following the simulation methodology detailed by Cain et al.14. Training data consisted of mirror-symmetric random Clifford circuits with varying depths (D = 2–18 for Type I circuits, D = 4–36 for Type II circuits) and code distances (d = 3 and 5) for surface code implementations. Testing datasets were generated using the same simulation framework but with circuit depths extending beyond training ranges. A representative sample of the training and testing datasets is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196063 (ref. 44). The complete datasets can be reproduced using the simulation parameters and noise models detailed in Methods and following the procedures described by Cain et al.14.

Code availability

The code supporting the MCCD findings of this study is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196115 (ref. 45). The code is released under MIT License. The quantum circuit simulations were performed using the open-source stim package available via GitHub at https://github.com/quantumlib/Stim, following the methodology detailed by Cain et al.14. Benchmarking comparisons used PyMatching42 for MWPM decoding, stimbposd43 for BP-OSD decoding and the MLE implementation from Cain et al.14.

References

Acharya, R. et al. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 614, 676–681 (2023).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Lacroix, N. et al. Scaling and logic in the color code on a superconducting quantum processor. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.14256 (2024).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, R2493 (1995).

Calderbank, A. R. & Shor, P. W. Good quantum error-correcting codes exist. Phys. Rev. A 54, 1098 (1996).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer Codes and Quantum Error Correction. PhD thesis, California Institute of Technology (1997).

Knill, E. & Laflamme, R. Theory of quantum error-correcting codes. Phys. Rev. A 55, 900 (1997).

Berlekamp, E., McEliece, R. & van Tilborg, H. On the inherent intractability of certain coding problems. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 24, 384–386 (1978).

Vardy, A. The intractability of computing the minimum distance of a code. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 43, 1757–1766 (1997).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Fowler, A. G., Whiteside, A. C. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. Towards practical classical processing for the surface code. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 180501 (2012).

Higgott, O. PyMatching: a Python package for decoding quantum codes with minimum-weight perfect matching. ACM Trans. Quant. Comput. 3, 1–16 (2022).

Fowler, A. G. Optimal complexity correction of correlated errors in the surface code. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1310.0863 (2013).

Cain, M. et al. Correlated decoding of logical algorithms with transversal gates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 240602 (2024).

Delfosse, N. Decoding color codes by projection onto surface codes. Phys. Rev. A 89, 012317 (2014).

Paler, A. & Fowler, A. G. Pipelined correlated minimum weight perfect matching of the surface code. Quantum 7, 1205 (2023).

Sahay, K., Lin, Y., Huang, S., Brown, K. R. & Puri, S. Error correction of transversal cnot gates for scalable surface-code computation. PRX Quantum 6, 020326 (2025).

Wan, K. H., Webber, M., Fowler, A. G. & Hensinger, W. K. An iterative transversal CNOT decoder. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.20976 (2024).

Varbanov, B. M., Serra-Peralta, M., Byfield, D. & Terhal, B. M. Neural network decoder for near-term surface-code experiments. Phys. Rev. Res. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevresearch.7.013029 (2025).

Bausch, J. et al. Learning high-accuracy error decoding for quantum processors. Nature 635, 834–840 (2024).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Modern Phys. 87, 307 (2015).

Baireuther, P., O’Brien, T. E., Tarasinski, B. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Machine-learning-assisted correction of correlated qubit errors in a topological code. Quantum 2, 48 (2018).

Baireuther, P., Caio, M. D., Criger, B., Beenakker, C. W. J. & O’Brien, T. E. Neural network decoder for topological color codes with circuit level noise. New J. Phys. 21, 013003 (2019).

Google Quantum AI and Collaborators. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature 638, 920–926 (2025).

Bengio, Y., Louradour, J., Collobert, R. & Weston, J. Curriculum learning. In Proc. 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning 41–48 (ACM, 2009); https://doi.org/10.1145/1553374.1553380

Roffe, J., White, D. R., Burton, S. & Campbell, E. Decoding across the quantum low-density parity-check code landscape. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043423 (2020).

Panteleev, P. & Kalachev, G. Degenerate quantum LDPC codes with good finite length performance. Quantum 5, 585 (2021).

Cain, M. et al. Fast correlated decoding of transversal logical algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.13587 (2025).

Serra-Peralta, M., Shaw, M. H. & Terhal, B. M. Decoding across transversal Clifford gates in the surface code. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.13599 (2025).

Zhou, H. et al. Low-overhead transversal fault tolerance for universal quantum computation. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09543-5 (2025)

Bombin, H. & Martin-Delgado, M. A. Topological quantum distillation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 180501 (2006).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. Quantum Inf. Comput. 14, 1338–1372 (2014).

Knill, E. Fault-tolerant postselected quantum computation: schemes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0402171 (2004).

Bravyi, S. & Kitaev, A. Universal quantum computation with ideal Clifford gates and noisy ancillas. Phys. Rev. A 71, 022316 (2005).

Bravyi, S. & Haah, J. Magic-state distillation with low overhead. Phys. Rev. A 86, 052329 (2012).

Horsman, D., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Meter, R. V. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. New J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Litinski, D. & von Oppen, F. Lattice surgery with a twist: simplifying Clifford gates of surface codes. Quantum 2, 62 (2018).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hintont, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Combes, J., Granade, C., Ferrie, C. & Flammia, S. T. Logical randomized benchmarking. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.03688 (2017).

Gidney, C. Stim: a fast stabilizer circuit simulator. Quantum 5, 497 (2021).

Higgott, O. & Gidney, C. Sparse Blossom: correcting a million errors per core second with minimum-weight matching. Quantum 9, 1600 (2025).

Higgott, O. stimbposd: surface code decoder based on belief propagation and ordered statistics decoding. GitHub https://github.com/oscarhiggott/stimbposd (2023).

Zhou, Y. Data for ‘learning to decode logical circuits’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196063 (2025).

Zhou, Y., Multi-Core Circuit Decoder (MCCD). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17196115 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Y.Z. thanks M. Cain for sharing the simulation code used by Cain et al.14. C.W., Y.X., J.P.Z., K.Q.W. and E.-A.K. acknowledge support from the NSF through OAC-2118310. Y.Z. acknowledges support from NSF Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) through DMR-1719875 and from Platform for the Accelerated Realization, Analysis, and Discovery of Interface Materials (PARADIM), supported by the NSF under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2039380. The computation was carried out on the Cornell G2 cluster established in part with the support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative, Grant GBMF10436 to E.-A.K. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and E.-A.K. conceived and led the project. Y.Z. and C.W. implemented the code and performed numerical experiments. Y.Z., C.W., J.P.Z. and K.Q.W. designed the MCCD architecture. Y.X. contributed to data analysis and theoretical interpretation. E.-A.K. supervised the project and secured funding. Y.Z., Y.X. and E.-A.K. wrote the paper with input and revisions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Computational Science thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jie Pan, in collaboration with the Nature Computational Science team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5, discussion and Tables 1–3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Wan, C., Xu, Y. et al. Learning to decode logical circuits. Nat Comput Sci 5, 1158–1167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00897-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00897-4

This article is cited by

-

Efficiently decoding quantum errors with machine learning

Nature Computational Science (2025)