Abstract

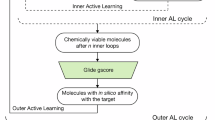

In recent years, artificial intelligence has advanced the design–make–test–analyze cycle, transforming molecular discovery. Despite these advances, the compartmentalized approach to computer-aided molecular design and synthesis remains a critical bottleneck, limiting further optimization of the design–make–test–analyze cycle. Here, to this end, we introduce SynGFN, which models molecular design as a cascade of simulated chemical reactions, enabling the assembly of molecules from synthesizable building blocks. SynGFN features two key ingredients: (1) a hierarchically pretrained policy network that accelerates learning across diverse distributions of desirable molecules in chemical spaces, and (2) a multifidelity acquisition framework to alleviate the cost of reward evaluations. These technical developments collectively endow SynGFN with the capability to explore a chemical space up to an order of magnitude larger (measured in terms of #Circles) than that of other synthesis-aware generative models, while identifying the most diverse, synthesizable and high-performance molecules. We demonstrate SynGFN’s potential impacts by designing inhibitors for GluN1/GluN3A, a therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric disorders.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The building block dataset is available via GitHub at https://github.com/ChemloverYuchen/SynGFN and via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/17034917 (ref. 49).

Code availability

SynGFN is available via GitHub at https://github.com/ChemloverYuchen/SynGFN and via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/17034917 (ref. 49).

References

Ghiandoni, G. M., Evertsson, E., Riley, D. J., Tyrchan, C. & Rathi, P. C. Augmenting DMTA using predictive AI modelling at AstraZeneca. Drug Discov. Today 29, 103945 (2024).

Stach, E. et al. Autonomous experimentation systems for materials development: a community perspective. Matter 4, 2702–2726 (2021).

Segler, M. H. S., Preuss, M. & Waller, M. P. Planning chemical syntheses with deep neural networks and symbolic AI. Nature 555, 604–610 (2018).

Gao, W. & Coley, C. W. The synthesizability of molecules proposed by generative models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 5714–5723 (2020).

Ertl, P. & Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminform. 1, 8 (2009).

Stanley, M. & Segler, M. Fake it until you make it? Generative de novo design and virtual screening of synthesizable molecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 82, 102658 (2023).

Hassen, A. K. et al. Generate what you can make: achieving in-house synthesizability with readily available resources in de novo drug design. J. Cheminform. 17, 41 (2025).

Walters, W. P. Virtual chemical libraries: miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 62, 1116–1124 (2019).

Swanson, K. et al. Generative AI for designing and validating easily synthesizable and structurally novel antibiotics. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 338–353 (2024).

Bengio, E., Jain, M., Korablyov, M., Precup, D. & Bengio, Y. Flow network based generative models for non-iterative diverse candidate generation. In Proc. 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 34, 27381–27394 (Curran Associates, 2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Sample-efficient multi-objective molecular optimization with GFlowNets. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Oh, A. et al.) Vol. 36, 79667–79684 (Curran Associates, 2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Phenyl fused ring compounds and their applications in the central nervous system. CN119371411A, China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) (2025).

Enamine. Enamine https://enamine.net (2023).

Thalji, R. K. et al. Discovery of 1-(1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)piperidine-4-carboxamides as inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 3584–3588 (2013).

Xie, Y., Xu, Z., Ma, J. & Mei, Q. How much space has been explored? Measuring the chemical space covered by databases and machine-generated molecules. In Proc. 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (OpenReview.net, 2023).

Cretu, M. et al. SynFlowNet: design of diverse and novel molecules with synthesis constraints. In Proc. 13th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2025).

Loeffler, H. H. et al. Reinvent 4: modern AI-driven generative molecule design. J. Cheminform. 16, 20 (2024).

Browne, C. B. et al. A survey of Monte Carlo tree search methods. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 4, 1–43 (2012).

Fancelli, D. et al. Potent and selective Aurora inhibitors identified by the expansion of a novel scaffold for protein kinase inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 48, 3080–3084 (2005).

Wang, S. et al. Structure of the D2 dopamine receptor bound to the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone. Nature 555, 269–273 (2018).

Bickerton, G. R., Paolini, G. V., Besnard, J., Muresan, S. & Hopkins, A. L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 4, 90–98 (2012).

Ghose, A. K., Viswanadhan, V. N. & Wendoloski, J. J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1, 55–68 (1999).

Wang, J. et al. Multi-constraint molecular generation based on conditional transformer, knowledge distillation and reinforcement learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 914–922 (2021).

Maurer, T. S., Edwards, M., Hepworth, D., Verhoest, P. & Allerton, C. M. N. Designing small molecules for therapeutic success: a contemporary perspective. Drug Discov. Today 27, 538–546 (2022).

Podda, M., Bacciu, D. & Micheli, A. A deep generative model for fragment-based molecule generation. In Proc. 23rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (eds Chiappa, S. & Calandra, R.) Vol. 108 2240–2250 (PMLR, 2020).

Mohammadi, S., O’Dowd, B., Paulitz-Erdmann, C. & Goerlitz, L. Penalized variational autoencoder for molecular design. Preprint at ChemRxiv https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.7977131.v1 (2019).

Hopkins, A. L., Keserü, G. M., Leeson, P. D., Rees, D. C. & Reynolds, C. H. The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 105–121 (2014).

Bossi, S., Pizzamiglio, L. & Paoletti, P. Excitatory GluN1/GluN3A glycine receptors (eGlyRs) in brain signaling. Trends Neurosci. 46, 667–681 (2023).

Paoletti, P., Bellone, C. & Zhou, Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 383–400 (2013).

Zhu, W., Shenoy, A., Kundrotas, P. & Elofsson, A. Evaluation of AlphaFold-Multimer prediction on multi-chain protein complexes. Bioinformatics 39, btad424 (2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Negative allosteric modulation of GluN1/GluN3 NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology 176, 108117 (2020).

Zeng, Y. et al. Identification of a subtype-selective allosteric inhibitor of GluN1/GluN3 NMDA receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 888308 (2022).

Dalke, A. The chemfp project. J. Cheminform. 11, 76 (2019).

Hartenfeller, M. et al. A collection of robust organic synthesis reactions for in silico molecule design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51, 3093–3098 (2011).

Button, A., Merk, D., Hiss, J. A. & Schneider, G. Automated de novo molecular design by hybrid machine intelligence and rule-driven chemical synthesis. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 307–315 (2019).

Roughley, S. D. & Jordan, A. M. The Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 54, 3451–3479 (2011).

Gaulton, A. et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1100–D1107 (2012).

Yin, X. et al. CODD-Pred: a web server for efficient target identification and bioactivity prediction of small molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 6169–6176 (2023).

Huang, K. et al. Therapeutics Data Commons: Machine Learning Datasets and Tasks for Drug Discovery and Development. In Proc. Neural Information Processing Systems Track on Datasets and Benchmarks (eds Vanschoren, J. & Yeung, S.) Vol. 1 (Curran Associates, 2021).

GOSTAR. https://www.gostardb.com/

Heid, E. et al. Chemprop: a machine learning package for chemical property prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 9–17 (2024).

Sun, J. et al. ExCAPE-DB: an integrated large scale dataset facilitating big data analysis in chemogenomics. J. Cheminform. 9, 17 (2017).

Olivecrona, M., Blaschke, T., Engkvist, O. & Chen, H. Molecular de-novo design through deep reinforcement learning. J. Cheminform. 9, 48 (2017).

Mehta, N. V. & Degani, M. S. The expanding repertoire of covalent warheads for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 28, 103799 (2023).

Malkin, N., Jain, M., Bengio, E., Sun, C. & Bengio, Y. Trajectory balance: improved credit assignment in GFlowNets. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) Vol. 35, 5955–5967 (Curran Associates, 2022).

Hawkins, P. C. D., Skillman, A. G. & Nicholls, A. Comparison of shape-matching and docking as virtual screening tools. J. Med. Chem. 50, 74–82 (2007).

Hawkins, P. C. D., Skillman, A. G., Warren, G. L., Ellingson, B. A. & Stahl, M. T. Conformer generation with OMEGA: algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 572–584 (2010).

Kearnes, S. & Pande, V. ROCS-derived features for virtual screening. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 30, 609–617 (2016).

Zhu, Y. ChemloverYuchen/SynGFN: SynGFN-1.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.17034917 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFA1306400), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 22373085) and Medical Interdisciplinary Innovation Program 2024, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. We are grateful to the organizer of the Shanghai International Computational Biology Challenge for conducting the bioactivity assays. We also express our gratitude to M. Wang from the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College for his assistance with the OpenEye software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. developed SynGFN code, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.C., D.Z., X.W., Y. Li and Y. Liu. evaluated and interpreted the results. S.L., Y.K., B.Z. and C.L. conducted wet-lab experimental validation. T.H. and C.-Y.H. conceived and supervised the project, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Computational Science thanks Longyang Dian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Kaitlin McCardle, in collaboration with the Nature Computational Science team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Explanation of the double sub-flow design of SynGFN and the pre-training strategy.

(a) Explanation of the hierarchical action design adopted by SynGFN, illustrating the process of adding a new reactant in a single step. Current State St represents the building block or intermediate product. Policy model 1 and Policy model 2 are used to predict actions based on the current state and previous actions. For Action 1, the model predicts the reaction to be performed, with probabilities for each reaction. For Action 2, the model predicts the reactants, and their probabilities are determined similarly. Sampled actions correspond to the selected reaction or reactant. (b) Explanation of the flow network behind SynGFN. The flow network is defined as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). Each node represents a state, with intermediate states denoted as x0, x1, and all terminal states as t0, t1. The process of generating objects in the flow network is analogous to water flowing from a start to an endpoint. The probability of taking an action at each state corresponds to the flow through a pipe. A flow-matching constraint ensures that the water entering a state equals the flow out. The flow network constrains the flow through terminal states to their reward feedback R(x). We implement a double sub-flow design for state transitions, representing hierarchical actions. For Action 2, Policy model 2 uses a pre-training strategy via a multi-label classification task to recognize and select reactants that match the specified reactions before training.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Evaluation of SynGFN as a chemical space search algorithm.

(a) Comparison illustration between SynGFN and virtual screening. We enumerated the virtual chemical space constructed from the smallest scale reactant library based on a two-step reaction (with a chemical space size of 300 million molecules) to compare the chemical space search efficiency differences between SynGFN and traditional virtual screening. (b) Comparison of chemical space exploration coverage between the top 10,000 molecules out of 1 million screened by virtual screening and the top 10,000 molecules out of 100,000 searched by SynGFN. We considered the #Circles changes under different threshold t and separately listed the #Circles results under thresholds t of 0.7, 0.75, and 0.8. (c) A t-SNE visualization of the top 10,000 molecules out of 1 million screened by virtual screening and the top 10,000 molecules out of 100,000 searched by SynGFN. (d) Comparison of QSAR activity score distributions between 1 million molecules screened by virtual screening and 100,000 molecules searched by SynGFN. (e) Evaluation of search efficiency between virtual screening and SynGFN. The number of hits under different QSAR activity score thresholds was calculated. To ensure fairness, the number of molecules screened by virtual screening here is also 100,000.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The evaluation of generated molecules.

(a) For three different targets, the QED distribution of the top 1,000 molecules in terms of QSAR activity scores sampled from 10,000 molecules (upper) and all 10,000 molecules (lower) sampled by four different scales of SynGFN models and the baseline models. (b) For three different targets, the logP distribution of the top 1,000 molecules in terms of QSAR activity scores sampled from 10,000 molecules (upper) and all 10,000 molecules (lower) sampled by four different scales of SynGFN models and the baseline models. (c) The t-SNE visualization results of the top 1,000 molecules in terms of QSAR activity scores sampled from 10,000 molecules by four different scales of SynGFN and baseline models under three different targets, along with the existing active molecules for the corresponding targets.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Evaluation of generated molecules.

(a) Comparison of Ligand Binding Efficiency (LBE) score distributions between SynGFN-XL generated molecules (top 1,000 out of 10,000 samples) and existing active molecules under three different targets. (b) The distribution curves of minimum RMSD values between molecules generated by SynGFN and active inhibitors against different targets. (c) Binding mode of the top-1 molecule generated by SynGFN-XL (based on docking scores). The first row shows the position and orientation of the generated molecule in the active pocket of the corresponding protein. The second row shows the interactions between the generated molecule and the corresponding protein (at 3.0 Å cut-off).

Extended Data Fig. 5 SynGFN has substantially accelerated the drug DMTA cycle.

(a) Chemical structures of the candidate compounds synthesized and evaluated for biological activity. Each compound is annotated with its Combo Score and IC50 value. The overlays below depict the align-ment of the generated molecules with the reference molecule: gaussian surface overlap is shown with the corresponding Shape Score, and pharmacophore feature alignment is shown with the corresponding Color Score. (b) Comparison between the synthetic routes proposed by SynGFN and the actual synthetic routes used.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–50, Tables 1–3, Sections 1–3 and reference.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for supplementary figures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

SMILES of all molecules used for display, as well as the SMILES of reactants in their synthetic routes and the corresponding catalog numbers.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

The molecular library from virtual screening and all molecules searched by SynGFN for comparison, along with their scores.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

All molecules generated by SynGFN and all baseline models for testing and evaluation on three targets.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Generated molecules of SynGFN on three targets.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

SMILES of the synthesized molecules D1–D10 involved in the wet-lab experiments, their three scoring results and the IC50 experimental values.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Li, S., Chen, J. et al. SynGFN: learning across chemical space with generative flow-based molecular discovery. Nat Comput Sci 6, 29–38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00902-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00902-w

This article is cited by

-

AI-guided molecular design with recipes included

Nature Computational Science (2025)