Abstract

The scientific literature, media, international summits, and policy forums highlighted enough the people who either move or are willing to move because of environmental reasons. Still, the voluntary environmental non-migrants (ENM), who are assumed to have strong resilience and coping capacity, are inordinately overlooked. The importance of addressing these ENMs has increasingly been emphasised. First, the paper explains the characteristics of ENM, outlining the key distinction between voluntary and forced non-migrants. Second, it emphasises the need to protect populations affected by environmental change and disaster, specifically highlighting oft-neglected ENM policy gaps. Thus, it examines to what extent ENM is addressed in existing global legal and policy responses. Having identified the gaps, it further considers the importance of adaptation strategies and well-planned relocation policies to support non-migration. Finally, it summarises the existing ENM policies’ scope and reflects on the key policy gaps identified to suggest the way forward. This paper urges for a pragmatic and strategic policy approach that ensures bottom-up community-oriented approaches for supporting ENM by: (i) coordinating adaptation activities, (ii) ensuring planned relocation and migration with dignity, (iii) enabling informed decision-making, (iv) mobilising national and international support, and (v) developing appropriate institutional structures for adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the face of adverse climate change impacts, some people may ‘decide to move’ to a safer place either temporarily or permanently, while many are likely to ‘decide to stay’ in their original place1,2,3,4. The people who either move or are ‘willing to move’ because of adverse environmental situations are characterised in the literature using a wide variety of terminologies such as climate refugees, climate migrants, environmental migrants, climate-induced displacement, and environmental displacement etc.5,6,7. These terminologies refer to displacement either internally or internationally, and temporarily or permanently, due to an environmental hazard. Furthermore, the international climate policy discourse explains three human mobility outcomes in the context of climate change: migration, displacement, and planned relocation8. Here migration refers to the voluntary movement of the people; contrary to this, displacement is termed as the forced movement of the people. And planned relocation is defined as the anticipated process of moving to a new place. Given the complexity and difficulties in measuring the influence of climate change on human mobility (see refs. 9,10) the International Organisation for Migration11 estimates that the number of ‘environmental migrants’ in 2050 could fall between 40 million and 1 billion. For instance, according to a global report on internal displacement, in 2021 alone, around 23.7 million people were displaced by disasters in 141 countries, of which 22.3 million were displaced by weather-related disasters12. There is limited empirical research demonstrating the exact types (forced or voluntary) and volume of environmental migrants and non-migrants13,14,15, and many studies confirm that only a fraction of the total number of people affected by disasters worldwide adopts the path of migration16,17,18. Evidence shows that most who experience environmental hazards stay put, even in precarious living situations19. These stayers, either voluntary or involuntary, are termed ‘environmental non-migrants (ENM)’ in this study.

For instance, between 2008 and 2016, it is estimated that about 85% of individuals threatened by disasters worldwide did not relocate20,21. These populations, often referred to as ‘immobile’, ‘non-migrant’ or ‘trapped’, remain in dangerous situations where climate change increasingly exacerbates their vulnerability by affecting their exposure to natural hazards. But not everyone staying is trapped, rather many of them are voluntarily staying, given that they have resources, capabilities and aspirations to stay at risk19. As a result, this immobility has far-reaching implications for the current and future lives of this population as the climate change consequence is not only an immediate livelihoods threat but also contributes to their fragile livelihoods conditions14,15,22. The importance of addressing the needs of these non-migrants in the policy discourses has increasingly been emphasised1.

While the people who either move or are willing to move because of environmental reasons are highlighted in the scholarly literature, media, international meetings, conferences, and policy forums, the ENM is inordinately overlooked19. In particular, the charter and mechanisms of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) systematically overlook the unique characteristics and needs of those stayers at risks, and have no specific reference to ENM19, although some of the recent developments are noticeable in different policy documents.

In 2010, the adoption of the Cancún Adaptation Framework (CAF) by Parties to the UNFCCC was the first explicit acknowledgement of the need for cooperation on human mobility in a changing climate. In 2009, during African Union’s Kampala Convention, policymakers finally recognised the importance of internal migration due to natural or man-made disasters. Again in 2018, the United Nations adopted the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) that includes 12 actions under objectives 2, 5, 21, and 23 that are particular relevance to address the people who are compelled to leave their countries due to adverse effects of climate change and environmental degradation23. Besides, the recent UNICEF’s Guiding Principles for Children on the Move in the Context of Climate Change (2022) addresses the rights and well-being of children and youth moving in the context of climate change. In particular, these principles apply to children who cannot or choose not to move, including children ‘left behind’ by migrating parents, whose enjoyment of rights may be negatively impacted by climate change24. Despite some of these initiatives, examining how the international climate policy, notably in the UNFCCC, systematically neglected the voluntary stayers and other immobile population at risk is evocative.

This paper explores how far ENM has been addressed in international policy responses and argues that more significant consideration of non-migrants is needed. First, it explains the characteristics of ENM, outlining the key distinction between voluntary and involuntary non-migrants and the interrelationship between environmental migration and non-migration. It emphasises the need to protect populations affected by environmental change and disaster, specifically highlighting oft-neglected ENM policy needs. Second, this paper examines to what extent ENM is addressed in existing global policy responses. Having identified the gaps, it further considers the importance of adaptation strategies and well-planned relocation policies to support non-migration. Finally, it summarises the scope of the existing policies and reflects on the vital policy gaps identified to suggest the way forward for supporting ENM. This paper posits that a pragmatic, strategic policy approach to ENM can provide a framework for coordinating adaptation activities, ensuring planned relocation with dignity, enabling informed decision-making, mobilising national and international support, and developing appropriate institutional structures for adaptation.

Demystifying environmental non-migration

The environment-migration literature considers environmental conditions such as push factors25, but the ‘environmental non-migrants’ are the people who stay in an environmentally vulnerable locale despite environmental risks, either voluntarily or involuntarily26. Environmental degradation influences human life in diverse ways. The ‘decision to move’ is the most challenging decision for a person affected or likely to be affected by the impending disaster27. Whether the decision will be of their free will or compelled by some other external factors is generally determined by the unique social, political, environmental, and security context of the concerned person or group of persons20. It is not a linear decision but a complex outcome interrelated with many variable circumstances and factors at a range of spatial and temporal scales14,25 that affects the livelihood conditions26. Thus, non-migration and migration are dynamic, intertwined processes that evolved through risk perception, risk tolerance, and self-efficacy26. There are several dimensions of environmental migration and non-migration that have been debated; for instance, the place of destination, the extent of the move (near or distant), the duration of stay (temporary or permanent), the decision to return, and the time of return all result from a cognitive process weighing the adaptive capacity, availability of resources, the pace of environmental changes, and more28. Several factors that influence non-migration have also been empirically verified26. Like, based on a field survey in Peru, Adams1 identified three reasons for non-migration: high satisfaction levels, resource barriers, and low mobility potential. The reasons identified for ‘low mobility’ include ‘obligations to family members, property or assets, affective and social ties to the location and no suitable alternative location’ (p. 441)1, displaying a complex blend of internal motives and external circumstances. In their study29, elaborate on four dimensions of migrants and non-migrants based on the scale and severity of ‘people-place vulnerability’ and ‘migration continuum’—trapped, displacement, voluntary migration (i.e., migration as adaptation), and voluntary non-migration (i.e., adaption in place). But, in this paper, we employ the ‘capabilities and aspirations’ framework, i.e., immobility in terms of the intersection of one’s capabilities to move or stay and their preference30, and defined environmental non-migrants into two groups: voluntary and forced. Amongst these, voluntary non-migrants are highly neglected in the climate change adaptation policy19.

Voluntary environmental non-migrants

Voluntary environmental non-migrants refer to the people who stay voluntarily at risk19; thus, they do not have a feeling of being trapped or having no choice but to stay. They may choose to stay because of multiple reasons, including strong resilience to cope with adverse situations, availability of and access to financial resources to sustain a livelihood, possessing the education and skill to avail alternative economic opportunities and having strong social networks which provide enormous support1,3,19,31. It can be assumed that overall environmental non-migrants do not move because they deem they can cope with the livelihood risks of environmental change or disaster (e.g., voluntary non-migration) and/or they cannot realise their aspiration to migrate (e.g., involuntarily non-migration)32. One of the prime reasons for such decisions is the intergenerational learnings and practices—thus, they learned to live with environmental disasters from their earlier generations. Furthermore, voluntary non-migrants may have enough money to bear the livelihood costs25,27,33, access to credit34,35, alternative economic opportunities, including remittances36, and vital place attachment1 than the traditional ones. They may be sufficiently socially and politically well-connected to manage a livelihood crisis after an environmental event33. According to Farbotko and McMichael (p. 150)13, these people have ‘an informed, freely indicated preference to remain in sites where there is, or is expected to be, high vulnerability to environmental risk’; thus, they make a conscious and active decision to stay37.

Adaptation strategies can offset voluntary environmental non-migration in the form of in situ adaptation32 or translocal livelihoods38,39, or itself adopted as part of a strategy for resilience40. Translocal livelihoods refer to the adaptation practices when the wage-earners of the family migrate because of better livelihood opportunities and continue to share the burden of their dependants at the origin. This type of translocal livelihoods is very common in the face of slow-onset environmental changes because such slow-onset events (i.e., salinity intrusion, sea level rise) do not always directly affect the livelihoods drastically, and therefore, people accustomed to the changes as part of the fluctuations of their regular livelihood, despite the opportunity to replan their in situ livelihood strategies to overcome impending environmental change32. But there are also evidence that slow-onset environmental changes with their cumulative impacts on resource-based livelihoods, as well as due to their often-prolonged nature are increasingly shaping the need of migration, for instance, the seasonal migration pattern in Bangladesh due to salinity intrusion41 and the pastoralist mobility in Africa due to drought42.

Again, human mobility triggered by rapid-onset natural hazards is primarily determined by the location of homes in areas prone to their impacts, and people’s underlying vulnerability to shocks and stresses that can disrupt or destroy their livelihoods, leaving them with few safe and voluntary solutions to their immediate predicament43. Thus, people who have enough resources or adequate opportunities to overcome the damage and losses caused by rapid-onset hazards remain voluntary and are considered voluntary environmental non-migrants26. Importantly, in all cases, people decide to stay37.

Forced environmental non-migrants

On the opposite end of the continuum of ‘aspiration and capability’ approach, certain people are not capable of handling the livelihood risks of environmental disasters yet are compelled to stay put—they are termed forced environmental non-migrants. They are characterised using various terms such as ‘left behind’, ‘immobile’5,44 and ‘trapped populations’ or ‘trapped non-migrants’22. Biao45 expresses ‘left-behinds’ in terms of suppressing their migration decision through institutional limitations; they are unable to move because of socioeconomic and institutional factors, irrespective of their motivations. In their overview, Toyota et al.40 developed a framework based on ‘household strategy theory’ that sees those ‘left behind’ as part of a strategy directed towards diversifying income sources to reduce economic risks and losses. It is evident that the left-behind peoples are dependent but whether they decide to stay voluntarily is unexplored. In the case of involuntary non-migrants, the capability to migrate is insufficient but the aspiration is present19. However, in the long view, changing resources, strategies, and desires over time also play a vital role in the development (or reduction) of capabilities5. Immobility refers to such contexts where non-migrants have never migrated before, i.e., there is a persistent lack of mobility due to their circumstances.

Environmental non-migrants ‘exist along a continuum’ (p. 429)1. Furthermore, forced and voluntary migration may not be clearly delineated as ‘all migration involves both choices and constraints’ (p. 8)30. When considering these shifting capabilities, there is not an easily discernible answer to why many people at risk do not appear even to seek or attempt migration. It is important to attend to the causes of this immobility, whether forced, involuntary or somewhere in between, especially in cases where migration presents a more outwardly active and favourable, but ultimately discarded or untenable, prospect. By extension, perspectives that broaden the remit of ‘environmental migration policy’ to include non-migration outcomes are necessary. Reviewing how this more extensive group of non-migrants has been addressed in legal and policy responses is the prime task of this review.

Review of existing policy responses to environmental non-migration

In response to environmental change, mobility takes various forms because of a multiplicity of drivers; these forms include evacuation, planned relocation, internal displacement, cross-border displacement, migration as adaptation, and more46. Bettini (p. 35)9 argues that these forms are viewed as mobility responses to climate change and that ‘while these different ‘mobilities’ are understood in a continuum, each speaks to specific audiences and agendas’. Policy responses dealing with this broad population whose migration decision is influenced by environmental events must consider these variables and differences. A close look at the ‘wording’ of the discussions and decisions of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COPs) concerning climate-related human mobility between 2010 and 2015 reveals that the policymakers emphasised ‘enhanced understanding’ of different aspects of human mobility (including non-migration) and displacement47. While the Cancun Agreement (1/CP.16) (p. 4)48 urges the parties to undertake ‘measures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation about climate change-induced displacement, migration and planned relocation’, the Doha decision on loss and damage (3/CP.18) encouraged work to enhance understanding of how impacts of climate change are affecting ‘patterns of migration, displacement and human mobility’ (p. 23)49. Gibb and Ford (p. 1)50 argue that through the aforementioned para 14(f) of COP16, the global community acknowledged that human mobility in the context of climate change may have different forms and dimensions, therefore requiring ‘diverse policy approaches’. The historic Paris Agreement (COP23)51, without having a separate provision on human mobility, broadly recognises the importance of protecting the human rights of people in vulnerable situations, such as children, women, migrants, and indigenous people. Furthermore, the recommendations made by the Task Force on Displacement (TFD) also refer to and include ‘the broader term of human mobility’ and recognise the long continuum of human mobility46. The TFD recommends the state parties to ‘adopt and implement national and subnational legislation, policies, and strategies recognising the importance of integrated approaches to avert, minimise and address displacement related to the adverse effects of climate change and issues around human mobility, taking into consideration human rights’ (p. 9)46.

Although, in the last decade, there have been some optimistic developments in the UNFCCC decisions and processes in regard to human mobility in the context of climate change52 the ENM populations are systematically neglected in international policy discussions13,19. While the literature shreds evidence that a large number of people in the face of extreme environmental events may decide to remain in their original place, the current global migration governance is substantially premised on the concept that ‘people have to be forced to move’ to be entitled to protection53. For example, the only international treaty to deal with refugees, the 1951 Refugee Convention, extends protection only to the people who are compelled to cross an international border due to certain social and political reasons (p. 3)53. Although the Convention excludes the people, who are displaced internationally because of environmental drivers, the principles of non-refoulement and the complementary protection within the international refugee law and human rights provide some limited protection to the people who decided to ‘move’ due to environmental reasons54. Furthermore, the UNHCR’s Legal Considerations Regarding Claims for International Protection Made in the Context of the Adverse Effects of Climate Change and Disasters (2020) provides ‘key legal considerations’ regarding the applicability of the international protection regime including international refugee law and human rights law when cross-displacement occurs in the context of climate change and disasters55. The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement recognises and extends protection to the people displaced internally due to natural or human-made disasters. Furthermore, the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) and Global Compact on Migration (GCM) adopted in 2018 recognise the need for the protection of people displaced because of environmental reasons.

However, people who decide to stay in the face of adverse environmental situations may equally require protection and can pose just as important a policy concern as those who decide to ‘move’. Therefore, focusing exclusively on people who moved the policy interventions may risk leaving behind a vast majority of people who tend to stay in environmentally vulnerable areas.

Therefore, the international legal apparatus needs to recognise the plight of people who remain either voluntarily or involuntarily while others choose to leave to initiate measures for their protection. Sometimes governments follow an easy route to protecting people living in areas affected by severe environmental events by declaring the area uninhabitable and promoting relocation1. However, relocation without proper planning and consultation may further aggravate existing vulnerability56. By understanding the entire continuum of migration decision-making in environmentally vulnerable areas, the global community can instead put policies in place that address people’s vulnerability, choice, and adaptive capacity irrespective of migration outcome. Policy responses need to consider a holistic approach encompassing the concerns of people who are unable or unwilling to move in the face of deteriorating environmental conditions and adopt innovative adaptive measures to make them more resilient to environmental effects and reduce their vulnerability. Specifically, guiding policies are required that engage with the desires as well as the material conditions and capabilities of non-migrants1 to better facilitate adaptation that allows them to survive in place57. The literature review on ENM as stated in the section ‘Demystifying environmental non-migration’ reveals that ENM broadly falls into two categories: (a) voluntary and (b) forced or involuntary. The global policy instruments developed in the context of climate change, disaster and sustainable development, including UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development emphasised strengthening adaptation mechanisms in the environmental vulnerable area to build community/individual resilience through comprehensive climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, sustainable development, infrastructure development and livelihood diversification etc. to help people ‘stay’ in their original places58. However, migration itself is considered an important adaptation and coping strategy in some literature. Furthermore, the UNFCCC Decisions and the TFD recommend undertaking planned relocation of people away from at-risk areas when necessary59. This approach helps people move out of harm’s way in high-risk situations and when the displacement is difficult to avert or prevent46. Thus, the policy development regarding human mobility in the last decade as well as the scholarly literature on climate change and human mobility, reveals the following two main approaches that may be useful in dealing with environmental non-migration, both voluntary and forced.

Strengthening adaptation, promoting resilience

Adaptation depends largely on the adaptive capacity of people to cope with the changing environment. Therefore, the adaptation programs are mainly premised on the concept of capacity building of the people living in environmentally vulnerable areas so that they can be more resilient to the impending change60,61. However, the adaptive capacity of a particular community depends on that community’s socioeconomic needs and livelihood options62. Therefore, the coping capacity can be substantially strengthened by promoting sustainable rural and urban development, such as improving food security, providing shelter, facilitating access to safe water and health care etc.62. (The IPCC defines adaptation as an ‘adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climate stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities’).

The IPCC (2007, 6)63 defines adaptation as an ‘adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climate stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities’. The UNFCCC is the basic legal document for adaptation to climate change. Article 4 of the Convention is the pivotal section for adapting and enhancing adaptive capacity in a climate change regime. Paragraph 1(b) of article 4 provides that parties must formulate and implement national or regional programmes containing ‘measures to facilitate adequate adaptation to climate change’ (UNFCCC, 1992, 5)64. Article 3(3) complements this clause, committing the parties to ‘take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent or minimize the causes of climate change’ (UNFCCC, 1992, 5)64. Thus, the Convention obliges all state parties to address adaptation in a preventive and strategic way through programmes, not merely relying on autonomous adaptation by nature. Significantly, the Cancun Summit in 2010 (COP16) particularly emphasised enhancing action on adaptation, deciding to establish the Cancun Adaptation Framework (CAF). During the same period, the discussion on human mobility and climate change began in the COP’s meetings and decisions. For the first time, the issues of migration, displacement, and planned relocation in the context of climate change were referenced in the CAF, where the states recognised human mobility potentials of climate change impacts48. Recognising the complexities involved in human mobility, the CAF addressed three distinct responses to environmental degradation—migration, displacement, and planned relocation58. The historic Paris Agreement (COP23) also provided a global goal for adaptation to strengthen sustainable development and resilience building51.

Thus, an international framework for adaptation exists within which regional and national initiatives can be developed to respond more clearly and directly to ENM adaptation needs. A Report published by the Platform on Disaster Displacement on Implementing the Commitments Related to Addressing Human Mobility in the Context of Disasters, Climate Change and Environmental Degradation: A Baseline Analysis Report under the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration highlighted the importance of addressing the rights of people with special needs including people with disabilities, older persons and economically and socially marginalised people who may face difficulties in movement and at risk of being trapped in areas affected by disasters and integrating their concerns in the national policy responses23.

However, many scholars and international organisations, including IOM, view migration can be framed as an adaptation65. The exponents of this framing assume that migration can have a positive impact enabling migrants to earn income and send back remittances to the families staying behind regularly. Thus, families can diversify their livelihood65. Studies found some vulnerable areas where remittances sent by migrants have long been a key element of food security. Drawing on case studies in Tanzania, Bolivia and Senegal, Tacoli showed that ‘the most vulnerable households are those that do not receive remittances’66. In the context of ENM, especially in the case of involuntary immobility, the working persons of the household may choose to migrate temporarily to neighbouring cities or across borders for livelihood and send remittances to the family staying put. The remittances help the family attain education, reduce poverty and build resilience to the vulnerability triggered by environmental events. Thus, policy approaches may consider facilitating safe, orderly, and regular forms of migration to the capable working members of the trapped population in supporting adaptation to climate change.

However, some states have already adopted the approach of strengthening adaptation measures and building the resilience of the people living in the areas at risk due to disaster and the effects of climate change to minimise displacement in their national policies, strategies, and national adaptation plans (NAPs) and the nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

For instance, the Displacement Guidelines in the Context of Climate Change and Disasters adopted by Fiji in 2019 acknowledges the importance of exploring all feasible alternatives to avoid displacement and strengthening adaptation and resilience strategies together with the integration of displacement considerations into disaster preparedness strategies as proposed by the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM)67. The Guidelines recognised three phases of displacement – pre-displacement, in-displacement and post-displacement. The pre-displacement phase represents the stage the decision to migrate has not been taken yet and ‘adaptation options are still in place’67. In the pre-displacement process, the government authorities are required to generate awareness among people about the nature and consequences of displacement and implement national adaptation plans and programs to build resilience and avoid displacement67.

The NDCs submitted by Chad, Nigeria, the Republic of Sudan, and Sri Lanka refer to ‘how adaptation measures may allow people to remain in situ’68. For instance, Nigeria emphasised ‘strengthening rural infrastructure and the availability of jobs to discourage out-migration’68.

The NAPs submitted by states under the Cancun Adaptation Framework (CAF) increasingly integrate human mobility within adaptation plans and strategies. The Plans include adaptive measures to reduce the effects of environmental triggers on communities so that the ‘push’ for migration is reduced and displacement can be averted68. However, the plans also acknowledge the need for planned relocation and facilitating migration as an important adaptive strategy.

Thus, the national responses have increasingly adopted measures to build the resilience of vulnerable communities to environmental and climate change impacts aligned with the internationally agreed priorities of minimising and averting displacement. These policies, approaches, and best practices can be replicated in other countries vulnerable to climate change’s effects to prevent and minimise displacement in the context of climate change. The TFD can provide further guidelines for policymakers to integrate this approach in other policy areas such as migration, DRR and sustainable development policies. Also, the international community should provide technical and financial assistance to developing and the least developed countries in planning and implementing the adaptation programs, which may facilitate the people who either ‘choose’ or are ‘forced’ to stay in their original in face of intensifying environmental events.

Planned relocation with dignity and protection from arbitrary displacement

While research studies confirm that most people want to stay in their original place, in certain situations of extreme environmental degradation, when living in the area becomes impossible, planned relocation may inevitably be required69. Climate-related planned relocation is defined by70 as ‘the systematic relocation of people and assets away from places that have become uninhabitable or are considered to be at increased risk to climate change impacts, such as sea level rise, coastal erosion, flooding, thawing permafrost or land loss. Planned relocation can occur at a community, household or individual scale and is carried out under the authority of the State’. The international climate change negotiations emphasise strengthening cooperation among states concerning climate change-related ‘migration, displacement and planned relocation’52. Focusing on ‘planned relocation’ along with the ‘migration and displacement’ in the context of climate change, the international climate change framework emphasises that in dealing with climate-related human mobility, policy responses should encompass the people who are unable to unwilling to move without the assistance of planned relocation. It is encouraging that the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by the state parties within the Paris Agreement (2015) increasingly refer to planned relocation as a necessary adaptation strategy. In particular, The Bahamas, Comoros, Fiji, Haiti, Kiribati, Maldives and Mexico include provisions for the planned relocation of vulnerable people from the areas prone to disaster to safer places.

However, relocation without a concrete plan may further aggravate vulnerabilities rather than reduce existing vulnerabilities from environmental events56,60,70. Any relocation, not only that in the context of climate change, may lead to ‘loss of livelihoods, land and natural resources; food insecurity; homelessness; adverse health consequences; and economic and political marginalization’ (p. 702)70. Furthermore, poorly planned and forced relocations may violate several internationally recognised human rights, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which includes rights to culturally and spiritually important territory (Art. 27, ICCPR)71,72. The potential vulnerabilities are likely to emanate from planned relocation lead migration discourse to consider relocation as a ‘last resort’ (p. 703)70. For example, Vanuatu’s National Policy on Climate Change and Disaster-induced Displacement (2018) considers the planned relocation as ‘an option of last resort’ and the policy instead aims to ‘reduce the triggers of displacement as much as possible’73.

However, international law, in certain exceptional situations when severe environmental disasters or conflict may result in conditions that can thwart ‘national security, public order or public health’, allow governments to relocate people from places where lives are at risk (p. 195)58.

According to the UNHCR74, the evacuation, relocation, or prohibition of return from the affected area must be necessary and proportional to ensuring the safety and health of the people concerned. The UNHCR’s guiding principles on international displacement state that forced evacuation or relocation in the context of disasters are arbitrary ‘unless the safety and health of those affected require their evacuation’ (p. 7)75. de Sherbinin et al. (p. 456)76 state that ‘resettlement should only be considered in cases where in situ adaptation is impossible’; all feasible alternatives must have been explored75. This is consistent with the international law of the right not to be displaced70,77,78.

However, planned relocation with dignity needs careful consideration of several issues, including ‘adequate financial resources, supportive legal and institutional frameworks, careful consideration of land issues, adherence to human rights principles and genuine and equitable community participation with affected people’ (p. 702)70. If resettlement is considered the best option for the welfare of the communities, the relocation process ‘needs to be fair and equitable for the community, with every effort made to improve livelihoods’ (p. 457)76. The relocation process and planning must clearly understand and recognise the needs of the people targeted for relocation. Under no circumstances should they be forced to return to or resettle in any place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at further risk79,80.

Thus, the authorities must establish legal frameworks for relocation/resettlement to protect the affected populations’ welfare and human rights76. The Paris Agreement called on States to ensure that climate-related actions safeguard the substantive and procedural rights, including access to information and public participation enshrined in fundamental international human rights instruments51.

Thus, the policymaking process must ensure that procedural rights such as access to information, decision-making, and effective administrative and judicial remedies of affected individuals and communities are respected. According to the Aarhus Convention81, a successful procedure requires information sharing (Article 5) and participation (Article 7). Therefore, active and effective participation of the affected communities and civil society actors in the policymaking process is essential82. The regulations must be transparent and accessible so that people understand the requirements and plan for themselves accordingly.

The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement emphasise the need for consultation with the affected parties, stating that displaced persons’ free and informed consent shall be sought. The authorities responsible for replacing persons are encouraged to involve those affected, particularly women, in the planning and managing of their relocation. In particular, care should be taken to ensure that ‘proper accommodation is provided to the displaced persons, that such displacements are effected in satisfactory conditions of safety, nutrition, health and hygiene, and that members of the same family are not separated’ (p. 196)58.

Thus, the people affected by disasters should, in principle, be able to provide free and informed consent for relocation and choose freely where to live while displaced. For this, ‘accurate, up-to-date, and culturally relevant information’ must be provided to them so that they can ‘weigh the benefits and the risks involved’ (p. 12)83,84. Fiji’s Planned Relocation Guidelines (2018) is a unique example that safeguards the rights of the persons who choose not to participate in planned relocation. The Guidelines require the government authorities to assist them in determining how planned relocation will impact their lives and ensure their continued access to livelihoods, human rights, and basic services85. Also, the Government authorities must ensure that human rights norms and principles are respected, protected, and fulfilled. The relocation process is carried out in a ‘safe, dignified, and timely manner’85. Also, the Fiji Government established the Climate Relocation and Displaced Peoples Trust Fund, the world’s first-ever relocation fund, in 2019 to facilitate the relocation process in a planned and dignified manner according to the Planned Relocation Guidelines 2018. Fiji’s policy responses including the Displacement Guidelines (2019), the Planned Relocation Guidelines (2018) and the Climate Relocation and Displaced Peoples Trust Fund (2019) represent a holistic approach integrating all aspects of human mobility, engaging the communities in the process of relocation and taking into account the needs of the marginalised groups of the community such as children, the elder and person with disabilities whose mobility may become limited requiring additional support.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that existing policy frameworks on environmental migration tend to privilege the issues of migrants over non-migrants. On the whole, specific legal apparatus for the protection of non-migrants is scarce, with environmental migration itself being a relatively recent introduction to displacement frameworks. However, increasingly, the plight of those who stay in place has begun to be recognised; in particular, the acknowledgement of a wide range of climate-related mobility contexts by the UNFCCC framework allows for the diverse continuum of environmental migration experiences to be brought into the consideration of policymakers50. The current policy discussions provide two broad paths for supporting ENM: in situ adaptation and eventually planned relocation. There is a clear need for more specific policymaking that provides direct guidelines regarding ENM to protect and support non-migrants. Adopting more precise guiding principles would help ensure that these strategies are successful, i.e., they provide community protection, do not violate rights, remain inclusive, remain locally led, and do not exacerbate vulnerabilities.

However, relevant existing policies do demonstrate the potential to support ENM. The Cancun Agreement presented a watershed moment for adaptation, providing a broad framework for developing more specific adaptation policies. Moreover, although climate-related displacement is itself difficult to locate in traditional displacement frameworks, recourse to internationally recognised human rights such as the right to stay, freedom of choice, and freedom of movement can be invoked to support ENM.

States are under obligation to mitigate the potential human rights violations likely to arise from the negative impacts of climate change, taking concrete measures to fulfil, protect and promote internationally guaranteed human rights. Therefore, a rights-based approach to human mobility in the context of climate change and disasters demonstrates the potential for development as a suitable legal apparatus to protect the rights of both migrants as well as non-migrants86. The human rights-based approach requires measures to support the people living in the disaster-affected areas to consider the freedom of choice and movement as well as the unique vulnerability and needs of the disadvantaged group of people who become trapped because of their exposure in the disaster-ridden areas. The human rights framework obliges states to ensure substantive and procedural rights of the people requiring support. Thus, the human rights-based approach protects vulnerable groups and facilitates policy coherence, legitimacy, and accountability87.

It is encouraging that the human rights-based approach has been adopted in some recent national policies and guidelines, including Fiji’s Planned Relocation Guidelines (2018), the Displacement Guidelines in the Context of Climate Change and Disasters (2019), and Bangladesh’s National Strategy on the Management of Disaster and Climate Induced Internal Displacement (NSMDCIID) (2020). The Displacement Guidelines in the Context of Climate Change and Disasters asks the Government to ensure ‘permanent access to (basic) human rights, such as the right to food, water, a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of potentially at-risk groups, and access to social and cultural rights’ following the national policies and international human rights laws67.

For non-migrants, it can bolster the argument for in situ adaptation by legally reinforcing their right to stay. Furthermore, the human rights-based approach requires the authorities to ensure adequate information regarding the potential risks has been provided to people staying in environmentally stressed areas, and concrete measures are undertaken to minimise those risks88. If planned relocation is necessary, the rights-based approach can help rescue this maligned strategy by ensuring it is indeed a last resort and that the dignity and participation of the affected people are assured throughout the process69,88. For example, Fiji’s Planned Relocation Guidelines (2018) and Vanuatu’s National Policy on Climate Change and Disaster-induced Displacement (2018) contain provisions to protect the rights of the people being relocated in the context of climate change.

Thus, the policy responses need to incorporate core human rights principles of participation, transparency, and accountability so that the environmental non-migrants can either stay in their original place with in situ adaptation or relocate with dignity88.

Way forward

In the face of degrading environmental events, especially slow-onset disasters, the decision to move or not to move is guided by multiple interrelated factors and variables, including individual preferences and characteristics. These characteristics may include education, age, gender, religion, assets, and, importantly, livelihood risks and strategies. It is not easy to provide a unique definition and categorisation for people who decide to stay put (i.e., non-migrants) as it varies greatly depending on the particular social and environmental context. Taking such complexities into consideration, this paper has explored to what extent non-migrants (ENM), both forced or voluntary, are addressed and supported in global environmental migration policymaking.

Since the migration decision depends on multifarious interrelated factors, and in the same environmental situation where some people ‘decide’ to move, others ‘decide’ to ‘stay’, both categories of people have complex needs and concerns requiring different protections. However, there is a disconnection in the migration governance exclusively focusing on migration and displacement, leaving behind a large majority of people who are unable or unwilling to migrate. Policymakers should understand that there is a deep interconnection between migration and protective measures for the remaining people. As people generally prefer to stay in their place, the numbers of environmental migrants substantially depend on the protection measures afforded to those who choose to stay.

Law and policy must be developed to help people remain at their homes if it is still feasible, so long as they wish to stay there and to provide protection and assistance. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development suggests developing a comprehensive and integrated approach establishing a mandate to ‘leave no one behind’. This framework now needs to be translated into resilience-building programmes and actions89 and thus, of course, include the issues related to voluntary non-migrants in the face of creeping environmental events.

Furthermore, the ENMs should not be compelled to relocate to another area unless it is absolutely necessary for the people’s safety. Relocation should not be considered the only process for protecting climate change-affected people. However, relocation is a complex process requiring extensive consultation and planning. The affected communities must be involved in decision-making regarding resettlement locations, compensation, and development programs76. The evacuation and relocation programs must ensure that the rights guaranteed by the international human rights standards, such as the right to life, liberty, dignity, and security of the affected people, are respected75. The policy responses must devise innovative adaptation measures to build the capacity and resilience of the people so that people who choose to stay can cope with the changing environment and their livelihoods can sustain despite environmental risks.

References

Adams, H. Why populations persist: mobility, place attachment and climate change. Popul. Environ. 37, 429–448 (2016).

Hunter, L. M. Migration and environmental hazards. Popul. Environ. 26, 273–302 (2005).

Mallick, B. The nexus between socio-ecological system, livelihood resilience, and migration decisions: empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 11, 3332 (2019).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R. K. Pachauri & L. A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 151 (2014).

Schewel, K. Understanding immobility: moving beyond the mobility bias in migration studies. Int. Migr. Rev. 54, 328–355 (2020).

Renaud, F. G., Dun, O., Warner, K. & Bogardi, J. A decision framework for environmentally induced migration. Int. Migr. 49, e5–e29 (2011).

Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Smith, C. D. & Kniveton, D. A discursive review of the textual use of ‘trapped’ in environmental migration studies: The conceptual birth and troubled teenage years of trapped populations. Ambio 47, 557–573 (2018).

Nash, S. L. Knowing Human Mobility in the Context of Climate Change. The Self-Perpetuating Circle of Research, Policy, and Knowledge Production. In: movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 4 (1). http://movements-journal.org/issues/06.wissen/04.nash--knowing-human-mobility-in-the-context-of-climate-change-the-self-perpetuating-circle-of-research-policy-and-knowledge-production.html (2018).

Bettini, G. Where Next? Climate Change, Migration, and the (Bio)politics of Adaptation. Glob Policy 8, 33–39 (2017).

Gemenne, F. Why the numbers don’t add up: a review of predictions and forecasts for environmentally-induced migration. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 41–49 (2011).

IOM. Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation in IOM’s Response to Environmental Migration (IOM, Geneva); https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/ddr_cca_infosheet.pdf (2012).

IDMC & NRC. GRID 2022 – Children and Youth in Internal Displacement. https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC_GRID_2022_LR.pdf (2022).

Farbotko, C. & McMichael, C. Voluntary immobility and existential security in a changing climate in the Pacific. Asia Pac. Viewp. 60, 148–162 (2019).

Thiede, B. C. & Robinson, A. & Gray, C. Climatic Variability and Internal Migration in Asia: Evidence from Integrated Census and Survey Microdata, SocArXiv hxv35, Center for Open Science (2022).

Benveniste, H., Oppenheimer, M. & Fleurbaey, M. Climate change increases resource-constrained international immobility. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 634–641 (2022).

Nawrotzki, R. J. & DeWaard, J. Putting trapped populations into place: climate change and inter-district migration flows in Zambia. Reg. Environ. Chang. 18, 533–546 (2018).

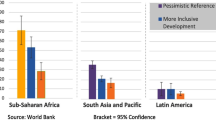

Rigaud, K. K. et al. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration—Academic Commons. (World Bank, Washington, DC, USA, 2018).

Black, R. & Collyer, M. ‘Trapped’ populations: limits on mobility at times of crisis. In Humanitarian Crises and Migration (eds Martin, S.F., Weerasinghe, S. & Taylor, A.) 287–305 (Routledge, London, UK, 2014).

Mallick, B. & Schanze, J. Trapped or voluntary? Non-migration despite climate risks. Sustainability 12, 4718 (2020).

IOM. World Migration Report 1st edn (IOM, Geneva); https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/china/r5_world_migration_report_2018_en.pdf (2018).

CRED. Disasters 2018: Year in Review, Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database (2019).

Foresight. Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities. (The Government Office for Science, London, UK, 2011).

Mochnacheva, D. Implementing the commitments related to addressing human mobility in the context of disasters, climate change and environmental degradation: a baseline analysis report under the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration. Platform on Disaster Displacement (2022).

UNICEF. Guiding Principles for Children on the Move in the Context of Climate Change, Office of Global Insight and Policy. (United Nations Children’s Fund, New York, USA, 2022).

Black, R. et al. Migration as adaptation. Nature 478, 447–449 (2011).

Mallick, B. Environmental non-migration: analysis of drivers, factors, and their significance. World Dev. Perspect. 29, 100475 (2023).

Zickgraf, C. Theorizing (im)mobility in the face of environmental change. Reg. Environ. Change 21, 1–11 (2021).

Hugo, G. Migration, Development, and the Environment. (IOM Migration Research Series, Geneva, 2008).

Hunter, L. M. et al. Scales and sensitivities in climate vulnerability, displacement, and health. Popul. Environ. 43, 61–81 (2021).

Carling, J. R. Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 28, 5–42 (2002).

Warner, K. Coordinated approaches to large-scale movements of people: contributions of the Paris agreement and the global compacts for migration and on refugees. Popul. Environ. 39, 384–401 (2018).

Mallick, B., Sultana, Z. & Bennett, C. M. How do sustainable livelihoods influence environmental (non-) migration aspirations? Appl. Geogr. 124, 102328 (2020).

Warner K., Hoffmaister J. & Milan A. Human mobility and adaptation: reducing susceptibility to climatic stressors and mainstreaming. In Environmental Change, Adaptation and Migration (eds Hillmann, F., Pahl, M., Rafflenbeul, B. & Sterly, H.) (Palgrave Macmillan, London) https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137538918_3 (2015).

Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Sultana, P. & Thompson, P. M. The ‘last resort’? Population movement in response to climate-related hazards in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Policy 27, S44–S59 (2013).

Peth, S. & Birtel, S. Translocal livelihoods and labor migration in Bangladesh: migration decisions in the context of multiple insecurities and a changing environment. In Environment, Migration and Adaptation – Evidence and Politics of Climate Change in Bangladesh (AHDPH) Dhaka (11) (PDF). Translocal Livelihoods and Labour Migration Systems in Bangladesh (eds Mallick, B. & Etzold, B; accessed 6 January 2023); https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265332040_TRANSLOCAL_LIVELIHOODS_AND_LABOUR_MIGRATION_SYSTEMS_IN_BANGLADESH (2014).

Siddiqui, T. International migration as a livelihood strategy of the poor: the Bangladesh case. In Migration and Development: Pro-poor Policy Choices (ed. Siddiqui, T.) (The University Press, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005).

Hjälm, A. The ‘stayers’: dynamics of lifelong sedentary behaviour in an urban context. Popul. Space Place 20, 569–580 (2014).

Etzold, B. & Mallick, B. Moving beyond the focus on environmental migration towards recognizing the normality of translocal lives: insights from Bangladesh. In Migration, Risk Management and Climate Change: Evidence and Policy Responses (eds Milan, A., Schraven, B., Warner, K. & Cascone, N.) 105–128 (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Sakdapolrak, P. et al. Migration in a changing climate. Towards a translocal social resilience approach. DIE ERDE – J. Geogr. Soc. Berl. 147, 81–94 (2016).

Toyota, M., Yeoh, B. S. A. & Nguyen, L. Bringing the ‘left behind’ back into view in Asia: a framework for understanding the ‘migration–left behind nexus. Popul. Space Place 13, 157–161 (2007).

Chen, J. & Mueller, V. Coastal climate change, soil salinity, and human migration in Bangladesh. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 981–985 (2018).

Manzano, P. et al. Toward a holistic understanding of pastoralism. One Earth 4, 651–665 (2021).

Hamani, S. Human mobility in the context of climate change, natural disasters, and conflict. Expert Group Meeting on Affordable Housing and Social Protection Systems for All to Address Homelessness, 22–24 May, Nairobi, Kenya. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/10/final_for_publication_homelesness_egm_proceedings_report_1.pdf (2019).

Bakewell, O. & Jónsson, G. Theory and the study of migration in Africa. J. Intercult. Stud. 34, 477–485 (2013).

Biao, X. How far are the left‐behind left behind? A preliminary study in rural China. Popul. Space Place 13, 179–191 (2007).

IOM & PDD. Meeting report of Task Force on Displacement Stakeholder Meeting. Recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change (IOM, Switzerland); https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/sites/default/files/05092018%20TFD%20Stakeholder%20Meeting%20Report%20%28FINAL%29.pdf (2018).

Serdeczny, O. What Does it Mean to “Address Displacement” under the UNFCCC. An Analysis of the Negotiations Process and the Role of Research. (German Development Institute, Bonn, 2017).

UNFCCC. Decision 1/CP.16, The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention, document FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1 (United Nations, Cancun); https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf (2011).

UNFCCC. Decision 3/CP.18, Doha Agreement, document FCCC/CP/2012/8/Add.1 (United Nations, Doha); https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2012/cop18/eng/08a01.pdf#page=21 (2012).

Gibb, C. & Ford, J. Should the United Nations framework convention on climate change recognize climate migrants? Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 045601 (2012).

UNFCCC. Decision 1/CP.21, Paris Agreement, document FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 (United Nations, Paris); https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (2015).

Naser, M. M. The Emerging Global Consensus on Climate Change and Human Mobility (Routledge, 2021).

UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to The Status of Refugees (accessed 25 August 2016); http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10 (2010).

McAdam, J. Climate Change, Forced Migration and International Law. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012).

UNHCR. Legal considerations regarding claims for international protection made in the context of the adverse effects of climate change and disasters. Int. J. Refugee Law 33, 151–165 (2021).

Fernando, N., Warner, K. & Birkmann, J. Migration and natural hazards: is relocation a secondary disaster or an opportunity for vulnerability reduction? In Environment, Forced Migration and Social Vulnerability (eds Afifi, T. & Jäger, J.) (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12416-7_11 (2010).

ADB. Addressing Climate Change and Migration in Asia and the Pacific – Final Report. (Asian Development Bank, Manila, 2012).

Martin, M., Kang, Y. H., Billah, M., Siddiqui, T., Black, R. & Kniveton, D. Climate-influenced migration in Bangladesh: The need for a policy realignment. Dev Policy Rev. 35, O357–O379 (2017).

The Nansen Initiative. The Realities of Climate Change-related Human Mobility to be Addressed in Paris. Perspective (The Nansen Iniative, Geneva) https://www.nanseninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/24092015_Nansen_Initiative_Perspective_Climate_Change_FINAL_screen.pdf (2015).

Marks, D., Bayrak, M. M., Jahangir, S., Henig, D. & Bailey, A. Towards a cultural lens for adaptation pathways to climate change. Reg. Environ. Change 22, 1–6 (2022).

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A. & Pellegrino, A. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the end of the Millennium. (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1999).

Smit, B. et al. Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. In Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds McCarthy, J. J., Canziani, O. Leary, N. A., Dokken, D. J. & White, K S.) 877–912 (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. and Reisinger, A. (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 104 (2007).

UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, FCCC/INFORMAL/84, GE.05-62220 (E) 200705, online https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 21 Feb 2020) (1992).

Ober, K. & Sakdapolrak, P. How do social practices shape policy? Analysing the field of “migration as adaptation” with Bourdieu’s “theory of practice”. Geogr. J. 183, 359–369 (2017).

Tacoli, C. Not Only Climate Change: Mobility, Vulnerability and Socio-economic Transformations in Environmentally Fragile Areas in Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania. 1–45 (IIED, 2011).

Government of Fiji. The Displacement Guidelines in the Context of Climate Change and Disasters (Government of Fiji, 2019).

Wright, E., Tänzler, D. & Rüttinger, L. Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Responding via Climate Change Adaptation Policy. (German Environment Agency, Berlin, Germany, 2020).

Gromilova, M. Revisiting planned relocation as a climate change adaptation strategy: the added value of a human rights-based approach. Utrecht Law Rev 10, 76–95 (2014).

Farbotko, C. et al. Relocation planning must address voluntary immobility. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 702–704 (2020).

UN. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, A/RES/2200A(XXI) (United Nations, Paris); https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1951/01/19510112%2008-12%20PM/Ch_IV_1p.pdf (1966).

UN. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, A/RES/217(III) (United Nations, Paris); https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/217(III) (1948).

Government of Vanuatu. National Policy on Climate Change and Disaster-induced Displacement (Government of Vanuatu, 2018).

UNHCR. 2009 Global Trends: Refugees, Asylum-seekers, Returnees, Internally Displaced and Stateless Persons, Division of Programme Support and Management, UNHCR, online https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/country/4c11f0be9/2009-global-trends-refugees-asylum-seekers-returnees-internally-displaced.html (accessed on 21 Feb 2020) (2009).

UNHCR. Guiding Principles on International Displacement, E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/protection/idps/43ce1cff2/guiding-principles-internal-displacement.html (1998).

de Sherbinin, A. et al. Preparing for resettlement associated with climate change. Science 334, 456–457 (2011).

Morel, M. The Right not to be Displaced in International Law. (Intersentia, Cambridge, 2014).

Stavropoulou, M. The right not to be displaced. Am. Univ. Int. Law Rev. 9, 689–749 (1994).

Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement. IASC Operational Guidelines on the Protection of persons in Situations of Natural Disaster. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ecd1e733be.html (2011).

Burson, B. Protecting the rights of people displaced by climate change: global issues and regional perspective. In Climate Change and Migration South Pacific Perspective (ed. Burson, B.) 170 (Institute of Policy Studies, 2010).

UNECE. Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. (United Nations, Aarhus, Denmark, 1998).

Zetter, R. The role of legal and normative frameworks for the protection of environmentally displaced people. In Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence (eds. Laczko, F. & Aghazarm, C.) International Organization for Migration, Geneva (2009).

McAdam, J. Building international approaches to climate change. disasters, and displacement. Windsor YB Access Just. 33, 1–14 (2016).

McAdam, J. How to Address the Protection Gaps—Ways Forward. Paper presented at the Nansen Conference: Climate Change and Displacement in the 21st Century, Oslo, 5–7 June (2011).

Government of Fiji. The Planned Relocation Guidelines: A Framework to Undertake Climate Change Related Relocation (Government of Fiji, 2018).

Kolmannskog, V. Climate Change, Human Mobility, and Protection: Initial Evidence from Africa. Refugee Survey Quarterly. 29, 103–119 (2010).

Naser, M. M. Climate change and forced displacement: obligation of states under international human rights law. Sri Lanka J. Int. Law 22, 2 (2010).

Cubie, D. In-situ Adaptation: Non-Migration as a Coping Strategy for Vulnerable Persons 99–114 (Routledge, UK, 2017).

IOM. Climate Change and Migration in Vulnerable Countries: A Snapshot of Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (IOM, Geneva); https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/climate_change_and_migration_in_vulnerable_countries.pdf (2019).

Acknowledgements

B.M. acknowledges the support of Horizon 2020 MSCA grant number 846129 (Project partners: Technische University Dresden, Germany & Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado Boulder, USA), and M.M.N. acknowledges the support of Edith Cowan University (ECU) School of Business and Law Research Fund under which the earlier version of this paper was presented in the international conference on ‘Environmental Non-Migration: Framework, Methods and Cases’, held in 19–21 June 2019, Dresden, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: M.M.N. and B.M. Review and analysis: M.M.N., B.M. and R.P. Results and discussion: M.M.N., B.M., S.H. and A.B. Writing drafts: M.M.N. and B.M. Copy—editing and revision: R.P., S.H. and A.B. Finalising: M.M.N. and B.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naser, M.M., Mallick, B., Priodarshini, R. et al. Policy challenges and responses to environmental non-migration. npj Clim. Action 2, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-023-00033-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-023-00033-w

This article is cited by

-

Environmental immobility: A systematic review of empirical research

Ambio (2025)

-

Unveiling invisible climate im/mobilities: mixed-methods case study of a drought-prone rural area of Kersa, Ethiopia

Regional Environmental Change (2025)