Abstract

Companies can prioritize diverse types of sustainable investment finance to reflect their concerns about climate change and carbon emissions. One such investment avenue is voluntary carbon offset (VCO) projects, in which companies invest to offset their carbon footprint. However, despite growing research into what and how these companies are doing in VCO markets, much remains to be learned about the motivations for such investments. In this paper, we utilized two datasets with a natural linkage to conduct a mixed-method analysis for a group of 186 companies globally with 534 carbon offset projects in 2017. This allowed us to assess motivations that drive companies to invest in the offset projects, and how different motivations map on to specific purchase decisions which then channel into larger financial flows. We identified three corporate motivations for carbon offset investment and found that companies using carbon offsets to achieve carbon neutrality has been coupled with some companies highlighting the importance of using offsets to contribute to “company values” and “market competitiveness.” Our study uncovered two contrasting trends in offset investment. Companies driven by values and market competitiveness demonstrated a willingness to invest in high-cost projects that provide significant local co-benefits. On the other hand, companies motivated by carbon management and efficiency showed a preference for lower-cost projects, particularly those related to renewable energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world is facing significant and growing climate-related risks. Many organizations, including governments, investors, and private companies, are taking action to develop and implement strategies to tackle this challenge. Recognizing their pivotal role in climate solutions, companies are actively seeking avenues to combat climate change, supporting achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the goals of the Paris Agreement through green investment, behavioral change, and emission reductions1.

As companies strive to improve their environmental performance, they often turn to voluntary initiatives. Unlike regulatory compliance, voluntary programs are not mandated by the government and are undertaken at the discretion of companies2. These initiatives are born from the need for alternative political means to improve corporate environmental performance2,3, as existing regulations may not be effective in catalyzing innovative and sustainable practices4. As such, voluntary initiatives can sometimes drive innovation and fund creative solutions either in advance of regulations or in ways that are parallel2,5. There are three main categories of voluntary initiatives: government-sponsored, international voluntary standards, and corporate efforts where individual companies commit to specific environmental performance target4. The private sector’s engagement in international initiatives such as reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) has demonstrated the potential impact of voluntary initiatives in addressing environmental issues6,7,8,9, which can be seen as falling into the first two categories.

The third category involves the use of voluntary carbon markets, also known as voluntary carbon offsets (VCOs) or carbon credits, as an emergent mechanism to address emissions leading to climate change—thus representing a corporate strategy that can potentially contribute to both sustainable development and address climate change. Such activities hold the promise of a so-called sustainability “sweet spot,” where business interests overlap with environmental and social interests10,11,12. By investing in VCO projects, companies can increase climate finance flows—with potential spillover effects—while reducing their own carbon emissions. In addition, investing in voluntary carbon markets can, in some cases, allow companies to support projects that can deliver wider benefits across a diverse set of sustainable development goals. Voluntary carbon offsetting for climate goals has resonance with other visible, voluntary initiatives such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), eco-labeling, green products, zero emissions, and disclosure schemes13,14.

Several studies in the literature have investigated companies using VCO projects to deliver sustainable development benefits and reductions of greenhouse gases. A common thrust of analysis has been to assess the environmental integrity of such projects—namely, whether they are really generating the emissions and sustainability benefits that they claim to. Such studies have raised questions about VCOs and their role in a robust global response to climate change. But the voluntary carbon market also raises other questions about why companies chose to engage in these mechanisms. There is some broader literature on general participation trends and potential perceptions of benefits. Unlike the so-called compliance market, which is driven by regulations and therefore mandatory and limited to a specific set of regulated actors, the voluntary markets offer greater flexibility and broader participation5. Buyers in the voluntary markets ostensibly are motivated to purchase offsets by social responsibility considerations and concerns about climate change to reduce their emissions15,16. Yet other factors may be relevant as well: climate benefits and associated project co-benefits (e.g., health or employment) have been seen to add value to corporate interests via branding, public relations5, and corporate reputation17,18. Some companies have also been willing to pay an additional premium for independent verification of these co-benefits derived from activities generating emissions offsets19.

Companies’ motivations for offset investments may also evolve over time. While many may begin with a goal of reducing emissions to meet an emissions reduction commitment, other motivations may emerge, such as the desire to engage a larger set of sustainability or community benefits that go beyond emissions reductions16,20. As companies navigate this process, they face many choices, including price, technologies, locations, standards, and potential social impacts. These choices can be challenging, but they also offer companies the opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and responsible corporate citizenship.

However, there remain significant gaps in our understanding of what motivates companies to purchase offsets, particularly in categorizing corporate motivations for investing in offset projects and how these companies prioritize local co-benefits in their decisions to invest in carbon offsets. Several studies in the literature have investigated companies using VCO projects to deliver sustainable development benefits beyond the general emission-driven motivation. However, due to data limitations, most existing studies are constrained from drawing broader conclusions about the motivations of these corporate buyers10. In addition, there is no research systematically studying corporate motivations of offset investment and deciding across different project options, and no evidence has been presented regarding which factors determine corporate willingness to pay for carbon offsets.

This study aims to address the following key research questions. First, what are the motivations driving corporations to purchase offsets? By exploring these motivations, we aim to gain insights into the factors influencing corporate decision-making processes regarding offsetting practices, which can help elucidate corporate sustainability strategies and their implications. Second, how does the willingness to pay for the additional co-benefits of offsets vary among companies driven by different motivations? Building upon the motivations identified in the first research question, this analysis will shed light on the heterogeneous preferences and priorities of companies and their implications for sustainable practices. We provide two hypotheses which will be discussed in the “Results” section.

To address these questions, we employed a mixed methods approach to comprehensively examine the corporate carbon offset project investment process, from motivations to decision making and ultimate behavior related to co-benefits. Our research centers on the year 2017, which holds particular significance as it follows the Paris Agreement, thereby providing a relevant context for examining post-Paris corporate sustainable investment priorities. To conduct our analysis, we compiled a comprehensive dataset from various sources, including information on corporate offset investment decisions and the specific offset projects they purchased, drawn from secondary data from corporate CSR reports and from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) Climate Change Questionnaire. One of the advantages of using mixed methods is the embedded linkage between the two datasets used in this paper. By linking corporate commitment from the CSR reports to the projects’ characteristics from the CDP data, we can at least partially validate the outcome from offset investment.

In total, we analyzed 186 corporations with a combined revenue of $3.5 trillion that purchased 534 offset projects executed in 28 countries, 12 sectors, 39 industries, and 73 sub-industries during 2017. We present the distribution of project types aggregated at the country or regional level in Fig. 1. Notably, the 534 projects analyzed in our study accounted for 16.2 MtCO2e, which represents approximately one-third of the total volume of transactions in the voluntary market during that year21.

Results

Our analysis first focused on developing a categorization of primary motivations that drive companies to engage in and invest in voluntary markets. Through our coding strategy (see Methods), we identified 14 indicators, nine metrics, and three primary motivations as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Our data covers a total of 186 companies. 155 companies investing in carbon offsets have treated offsets as an effective way to cut carbon emissions and meet their voluntary mitigation commitments. 60 companies using offset projects as a branding tool to gain a competitive advantage in the market and bring their global and local markets closer. 59 companies have invested in carbon offsets to enhance and live out their corporate values.

Motivation 1: Company carbon management and efficiency

One clear motivation for companies to engage in voluntary carbon markets is to help them achieve emissions reduction goals in a cost-effective manner. 155 companies in our dataset investing in carbon offsets have treated offsets as an effective way to cut carbon emissions and meet their voluntary mitigation commitments. It was expected that a large proportion of companies would be driven by this motivation, which confirms the relevance of motivations described in the literature16,22,23,24,25,26.

With the increasing emphasis on significant emission reductions and global goals for long-term global carbon neutrality, companies progressed beyond general commitments and set more specific and ambitious goals to achieve deeper emission cuts. In doing so, they have engaged in discussions on how to utilize carbon management strategies to achieve emissions reductions efficiently, considering technological and resource constraints as outlined in their corporate CSR reports. Carbon offsets, in this context, can serve as a final step in the carbon management strategy, enabling additional reductions and facilitating progress towards carbon neutrality when other options become costly or infeasible. There are still ongoing discussions and challenges surrounding corporate commitments to carbon neutrality, such as whether they reflect true carbon neutrality at the company level, value chain level, or only represent a small portion of the total emissions. However, these discussions go beyond the scope of this paper. The main message from this motivation is clear: emissions offsets can be used to further reduce emissions once cost-effective internal efforts have been maximized.

Motivation 2: Company market competitiveness

We found that approximately 60 companies used offset projects as a branding tool to enhance their market competitiveness and align their global and local market strategies. These companies invested in carbon offsets as part of their branding and outreach to engage customers and strategic partners within their value chain. The sectors primarily represented in this group include consumer discretionary, industrials, financials, utilities, and technology. For companies in industries such as passenger transportation, transportation & logistics, retail, software, and home and office products, investing in offset projects can raise awareness among their customers about the impact of climate change. Shifting corporate branding and marketing to highlight “climate-positive” products can actively involve consumers as agents of positive change27. More details on the sector and industry distribution can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Such companies may seek to enhance their competitiveness by publicizing their offset activities. For instance, they may create a public-facing carbon offset program targeted at customers or launch an ambitious offset purchasing plan with their local market, either upstream or downstream in the value chain. An example of local markets advertising in the upstream sector of the value chain is Tiffany & Co., an American luxury jewelry and specialty retailer, which “invested in carbon offsets from Kenya’s Chyulu Hills to help meet our climate goals and promote sustainable development in an area of the world where we source colored gemstones and where we support wildlife conservation”28. An example of advertising along both the upstream and downstream value chain is Marui Group Co., Ltd., a Japanese retail company, which noted that “since 2014, we have been conducting carbon offset initiatives in disaster-stricken areas as well as in the areas that produce material for our shoes, the areas in which we open new stores, and other areas that benefit local customers”29.

Motivation 3: Company values

Fifty-nine companies in the sample claimed to have invested in carbon offsets to uphold and embody their corporate values. The ability to align with company values through offset investment is supported by four pillars: supporting SDGs, being responsible for a greater good, strengthening public relations, and committing to philanthropy. Among these pillars, 25 companies focused on supporting SDGs, 24 emphasized their commitment to the greater good, 22 aimed to strengthen public relations, and three companies were primarily committed to philanthropy.

For companies whose values encompass sustainability and human well-being, particularly those whose regular business operations impact emissions, taking actions on climate change is seen as crucial to upholding these values. The pillar of “taking responsibility” through investing in carbon offset projects involves supporting regions vulnerable to climate impacts, or aiding local communities affected by business operations. Companies became active in identifying offset projects for addressing their corporate values and are instrumental in linking co-benefits from projects to local communities. In one example, “the selection of these projects took into account the fact that they were located near the Pelotas Road Pole, which was admitted by Ecosul, a major concessionaire of the Ecorodovias Group, the main channel for the disposal of commodities produced in Rio Grande do Sul to the port of Rio Grande”30.

Motivations and purchasing behaviors are linked with local co-benefits

Our analysis underscores the significance of local co-benefits as a value proposition for offset projects during corporate decision-making. While motivation 1 (company management and efficiency) primarily focuses on driving carbon reductions, motivation 2 (company market competitiveness) and 3 (company values) revolve around financing value creation. We demonstrate that co-benefits serve as a value proposition in the entire purchase process. Our findings can be summarized in three key aspects.

First, corporate commitment to local co-benefits is a crucial factor in motivating companies to invest in offset projects

We analyzed corporate-level data and companies’ CSR reports to evaluate companies’ priority for delivering co-benefits generated from offset projects in local communities. Our analysis focused on various factors such as project selection criteria, project location, project type, and specific benefits. Panel a of Fig. 3. illustrates that among all the criteria mentioned by companies, benefitting local communities ranks as the top criterion. This finding underscores the vital role of co-benefits in driving corporate investment in offset projects. Panel b reveals that companies tend to select project sites in low-income countries. Panel c indicates a higher frequency of community-based projects compared to commercial-based projects. Finally, Panel d highlights the leading benefit that companies prioritize: improved quality of life. This emphasizes how companies place their investment in offset projects to contribute to local communities and make a positive impact on society.

Second, corporations utilize voluntary investment flows to channel finance to local communities

We establish a connection between corporate commitments and project-level data to examine the value proposition of offset projects by examining investment flows. Supporting key regions for corporate business through offset investments is one category within Motivation 2. Companies targeted investments in offset projects in areas where they operate, obtain raw material, conduct business, or have strategic partners, as stated in their CRS reports. Supplementary Table 1 provides details on such commitments from 20 corporates. To validate these commitments, we generated investment flow maps based on the project-level data from CDP. Panel a of Fig. 4 demonstrates how the investment flows align with the major markets of operation of one example, the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group. The company’s business spans Australia, New Zealand, several countries in the Asia Pacific region, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the United States. Panel b shows the two investment flows of Enagás, S.A., a Spain Utility Company, which invested in emissions reduction projects in the countries where it operates, Chile and Peru. Panel c provides an overview of the investment flows for all 20 companies. The finding in Panel c align with the corporate commitments outlined in their CSR reports, providing solid evidence that offset investment flows occur in the global-local direction. This emphasizes the impact of offset projects on the “local” dimension and further supports the importance of local co-benefits in realizing the corporate vision for offset projects.

Third, local communities were important for translating commitment into action on the ground

To examine the practical role of local co-benefits, we employed analytic visualization techniques on project-level data. Specifically, we utilized a word tree tool to analyze how words or word combinations related to the concept of “local” and identified multiple dimensions of local benefits in project descriptions. To present our findings concisely and informatively, we summarized them into a three-category table in Supplementary Table 2, with each column elaborating on our main argument as follows. The links between “local” and community concepts were clearly demonstrated through the beneficiaries associated with the target word. In fact, “community” and “communities” were the two most cited words, accounting for one-third of the group of beneficiaries. Project narratives frequently emphasized the importance of supporting vulnerable and disadvantaged groups such as small landholders, farmers, and women. This highlights the critical role of tailoring projects to the local context. The middle column of Supplementary Table 2 presents different dimensions of “local” benefits from the projects, which were directly linked to the target word. Job creation emerged as the most frequently mentioned benefit, followed by improvements to the environment and biodiversity. By closely aligning a variety of co-benefits to the local context, benefits became intrinsically linked to the local area. Finally, the benefits should be delivered to the beneficiaries through action words, which typically preceded the targeted word. The right column of the table lists all the words that preceded the word “local”, which underscore the positive effects of the projects and their ability to contribute to thriving local communities.

Mapping motivations on to purchasing behaviors

Offset purchasing decisions are a multi-stage process within a corporate entity10 involving different levels of hierarchy. Engaging in carbon management practices such as offset purchasing is often driven, at least in part, by a belief that market-based solutions can be practical in addressing environmental problems by linking a broader environmental goal to a specific financial mechanism. The motivations to engage in company values and market competitiveness are often encouraged by a theory that synergy between corporate sustainability actions and profits can be effective in addressing social problems. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that other motivations are present as well, such as more simply increasing company value or expanding market share. With these potential motivations in mind, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Companies whose primary motivation is to reduce emissions (M1) will prioritize the purchase of cost-effective offset projects (i.e., cheaper projects at a lower cost).

Hypothesis 2: Companies whose primary motivations are driven by non-emissions-related impacts (such as increasing market competitiveness or enhancing company value) (M2 and M3) will place a higher value on co-benefits and may be willing to pay a premium for offsets that achieve these impacts.

The premise of a carbon market is that carbon offsets can be created, regardless of the type of project, if they meet the eligibility requirements and certain standards. It follows that for purpose of reducing emissions, buyers can therefore purchase equivalent offsets from any project type if they are verified. However, beyond the emission reduction benefits, projects can vary widely, and some projects may have the potential to generate more immediate and positive local sustainable development impacts than others. Buyers may be willing to pay a premium for these offsets31,32. Given that different project types are sold at different prices in the market (see Supplementary Fig. 2), we explore the relationship between corporate purchasing decisions and these diverse project types to understand buyers’ preferences.

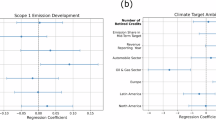

Our analysis finds that different project types tended to attract investments stemming from different corporate preferences and motivations, with 6 out of 11 categories significant at p = 0.090 or lower level. A few project types were significant, including forestry, household devices, and renewable energy (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, we conducted a robustness check to explore the interaction between corporate purchasing decisions and offset standards, and our findings indicate similar trends (see Supplementary Table 4). For detailed results, please refer “Methods”. To further explore which motivation favors specific projects, we provide a more detailed breakdown in Fig. 5 This statistical analysis can elucidate preferences among project types based on different motivations and the preferences between projects within the same motivation.

Green cells indicate a higher average price preference, suggesting that buyers tend to purchase more from projects with higher prices. Yellow-colored cells show that the preference over projects fits the assumption that buyers buy more projects due to the low price of the products. Note 1: The test results compare the average number of projects (number of transactions) within the respective project types, invested by companies driven by separate motivation.

Figure 5 presents three important relationships. First, companies motivated by company values (M2) and market competitiveness (M3) tended to purchase a greater number of offset projects at higher prices compared to those motivated by carbon management and efficiency (M1). In the boxes on the diagonal lines with thick borders, representing the three highest priced project types (household devices, forestry, and chemical process), we observed a significant difference in the number of projects purchased by M1 companies compared to M2 companies and M3 companies. However, no significant differences were observed between M2 and M3 companies. This suggests that M2 and M3 companies purchased more expensive projects than M1 companies. As project types moved towards the right corner of the diagonal line (i.e., offset credits became cheaper), no statistically significant difference in motivations towards project types were observed, except for renewable projects.

Secondly, companies motivated by carbon management and efficiency (M1) were associated with purchasing credits with lower prices and in certain project types. In the boxes marked with white backgrounds with only one or two yellow-colored cells, at least one yellow-colored cell belonged to an M1 company. The presence of yellow cells signifies the preference for a lower-priced project, while green cells show the selection of higher-priced projects. In this context, when M1 companies were faced with an investment decision between two project types, those with a lower price were more associated with M1 companies.

Thirdly, renewable energy projects were favored by all companies, except when compared with forestry projects. With options for investing in renewable energy projects or projects such as chemical processes, energy efficiency/fuel switching, waste disposal, or transportation, companies showed a preference for purchasing renewable energy projects. One reason for this may be that the average offset price of renewable energy is the lowest, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. In addition, renewable energy projects may offer better co-benefits compared to those alternative projects. However, when companies faced investment decisions between renewable energy projects and forestry or household device projects, the low-price factor was no longer a significant factor, suggesting that this had little to no impact on their decision-making.

Overall, this study reveals two contrasting trends in offset investment, driven by pricing signals. On one hand, companies motivated by values and market competitiveness (M2 and M3) are willing to invest more in high-cost projects such as household device and forestry projects, which can provide significant local co-benefits. On the other hand, companies motivated by carbon management and efficiency (M1) are attracted to lower-cost projects, particularly renewable energy projects, as well as other types like chemical processes, energy efficiency/fuel switching, waste disposal, or transportation. These projects not only provide cheaper carbon offsets, but also offer local co-benefits, particularly in the case of renewable energy projects.

Discussion

In this article we identify and examine company motivations for engaging in voluntary carbon offsets, and have assessed the relationship between these motivations and the types of carbon offset projects they invest in. The mixed methods approach enables us to link an analysis of corporate motivations and the assessment of their actual behaviors and co-benefits with a validation process tracing the flow from claim to outcome. The analysis addresses ongoing questions about whether offset investment lead to real co-benefits, as companies often claim in their CSR reports. Our findings on corporate preference towards project types, such as household devices and forests, and offset certificates, such as Gold Standard, were in line with existing literature33,34,35,36.

We further present a comprehensive framework of motivations for corporate offset project investments, highlighting a dual goal for financial and social returns on investments. Within this framework, we formulated two hypotheses, namely that companies motivated solely by emission reductions seek out cost-effective offset projects, whereas those motivated by non-emission impacts place greater value on co-benefits and are willing to pay more to achieve them. Our findings were in line with these hypotheses. Moreover, our analysis reveals that companies with multiple motivations (motivations 2 and 3) place a high premium on offset projects and certificates that generate co-benefits for local communities.

While our study focused on understanding how motivation influences engagement in VCO projects, it is important to recognize another crucial question: why do companies initially engage in voluntary initiatives for environmental performance improvement? Existing literature suggests that voluntary initiatives emerge as a response to the limitations of regulations and the search for alternative political approaches to enhance corporate environmental performance2,3. While current environmental regulations effectively control harmful behavior, they may not adequately inspire or motivate creative responses that lead to greener products and processes4. Hence, voluntary initiatives are believed to encourage innovation and foster creative solutions beyond regulatory requirements2,5. Voluntary programs can be categorized into government-sponsored initiatives, international voluntary standards, and individual corporate efforts committed to specific environmental performance targets4. Voluntary carbon offsetting can be viewed as one of the initiatives aimed at improving corporate environmental performance and touches upon various dimensions of voluntary initiatives, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), eco-labeling, green products, zero emissions, and more14. While the motivation behind engaging in voluntary initiatives is relevant to our study, it is not the primary focus, and we will not attempt to fully address this question within the scope of this paper. However, acknowledging the broader context of voluntary initiatives provides a foundation for understanding the significance of voluntary carbon offsetting as one aspect of corporate environmental performance improvement.

Our study also contributes to the discussion surrounding observed discrepancies between supply and demand of VCOs in the post-Paris period. One key challenge is the lack of a credible and feasible architecture to integrate broader environmental and other co-benefits into credits37,38. This presents a challenge for corporate CSR strategists who may encounter gaps in the types of benefits accruing in places that need them. Figure 1 illustrates the global distribution of project types, revealing that regions like Africa could benefit from a diverse range of project types to support sustainable development efforts. While household device projects offer substantial co-benefits to local communities, there is still a need for renewable energy projects in such regions. By investing in projects that provide higher co-benefits and offer credits at lower prices from renewable energy projects, companies can shift the course of their investment strategy while achieving positive impacts that align with their values and enhance market competitiveness.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the qualitative approach of our mixed method design relied solely on corporate CSR reports, which could introduce potential biases. Although project-level data were used to validate certain aspects of the information provided by companies, this study cannot deliver a complete picture of corporate offset investment decision-making as it solely relied on self-reported information. In addition, for companies that chose not to disclose information on their offset purchases, we were unable to access and evaluate their motivations. The lack of standardized formats for CSR reports may have led to assessment errors during the coding process. Lastly, the study focused on one year of data (2017) due to the need to identify, obtain, and process often disparate data, as well as other data limitations. Extending this study to multiple years would offer a more comprehensive understanding of corporate behavior over time. Despite these limitations, we are confident that the findings of this study are rigorous and can be generalized to the offset investment market. Future research utilizing diverse and comprehensive data sources can address some of these limitations and provide a more nuanced understanding of corporate offset investment decision-making.

This study also identified several key areas for future research that can provide valuable insights for corporate decision-makers and researchers. Conducting targeted interviews with companies representing the three identified motivation categories could provide deeper insights into their decision-making processes. Another potential avenue for future research is to investigate companies that do not mention their offset investments in their CSR reports. This could provide new information that was not captured in our current study. In addition, employing choice models that go beyond traditional discrete choice models can offer a more comprehensive understanding of corporate offset investment decisions. Quantitative statistical models could be utilized to explain these decisions and provide additional insights into the underlying motivations of companies. Exploring these research areas will enable a better understanding of corporate behavior and the development of more effective strategies for encouraging sustainable investment practices.

Methods

This study aims to investigate corporate motivations for voluntary investments in carbon offset projects and the prioritization of local co-benefits in their decision-making process. By addressing the following research questions, this study contributes to the existing literature: (1) What are the motivations driving corporations to purchase offsets? (2) How does the willingness to pay for additional co-benefits of offsets vary among companies driven by different motivations? We seek to answer these research questions by investigating motivations and co-benefits within the voluntary carbon offset (VCO) market. We utilize two primary data sources: published Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports and self-reported data from the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). The Data section provides an in-depth description of these data sources and their utilization to address our research questions. Furthermore, the Strategy section outlines our research strategy, employing a mixed-method approach for comprehensive data analysis and research question resolution. In the Coding Strategy section, we detail our qualitative analysis approach, while the Hypotheses section outlines our quantitative analysis. To ensure the robustness and balance of our study, we incorporate the Balance and Robustness sections, which provide additional support for our quantitative analysis.

A conceptual/theoretical framework

The conceptual framework presented in Fig. 6 below provides support for this study. It illustrates the decision-making process of corporations in purchasing emissions offsets from voluntary markets, leading to the acquisition of carbon credits as final products. Beginning from the left side of the framework, previous research suggests that offset purchasing decisions within corporate entities are often multi-stage, involving various hierarchical levels and offices10. This led us to our first research question. In the literature review, we identified two attributes of motivations aligned with this multi-stage decision process. The first attribute focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, while the second attribute explores motivations beyond emission reductions. These motivations are discussed in detail in the Introduction of the main paper. Through a qualitative analysis using a coding strategy, we identified three motivations: M1 (company carbon management and efficiency), M2 (company market competitiveness), and M3 (company values), which align with achieving additional benefits while reducing emissions. Moving to the right side of the framework, carbon credits have two functions, influenced by the evolution of practices in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) that emphasize sustainable development benefits alongside carbon reductions31,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Carbon offsets, when traded as credits, serve as both a commercial good in voluntary carbon markets and an intangible good with unique consumer behavior. Based on this theoretical foundation, our second research question emerged. To address these research questions, we developed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Companies primarily motivated to reduce emissions (M1) will prioritize the purchase of cost-effective offset projects, opting for lower-cost options.

Hypothesis 2: Companies driven by non-emissions-related impacts (M2 and M3), such as market competitiveness and company values, will place a higher value on co-benefits and may be willing to pay a premium for offsets that achieve these impacts.

We conducted quantitative analysis to further explore the research questions through the lens of the hypotheses.

Approach

This paper assesses the convergence of corporate decision-making, co-benefits of climate finance projects, carbon offsets, and sustainability. We examine these critical issues using the case of the VCO markets for insight into how they can help inspire and reform corporate practice on climate change to support sustainable low-carbon society. These markets offer a helpful lens on corporate social responsibility, particularly how companies might value the sustainable benefits in their decision-making process. First, corporates are the primary buyers in the voluntary markets10. While sometimes individual buyers do engage in these markets, this individual consumption is very limited compared to the corporate consumption. Individuals only made up 5% of the voluntary offset consumers while 80% were companies10. Secondly, the voluntary carbon markets landscape changed rapidly year by year, reflecting at least in part shifting buyers’ preferences among different projects. Over the course of its initial 16-year history, the cumulative volume of pure transacted VCOs (pure transacted offsets are offsets that not used to fulfill the pre-compliance purpose) have exceeded 1.2 billion metric tons (GtCO2e) with a total market value of $6.7 billion50 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Corporate investment decisions on the purchase of emissions offsets from the voluntary markets are private and not subject to disclosure to governments or the public. Thus, it is always challenging to understand why these companies makes these decisions. Internal discussions regarding these decisions are not documented nor are they accessible for public review. The price information for projects is likely a factor in decisions but with opaque markets, but we are unable to compare that factor fully with the others noted here. It is likely that offset purchasing decisions are multi-stage within a corporate entity10, involving different levels of hierarchy and different offices.

However, certain strategies enable at least partial illumination of these motivations. Insights can be obtained through companies’ published CSR reports, and self-reported data (from CDP). There are many ways of studying corporate motivations, such as interviews, social media, or corporate communications. Many companies publish annual CSR reports to communicate the activities and strategies being used to address social and environmental issues. They serve as an indicator of a company’s public stance toward social and environmental responsibility, strategic planning, and the level of integration in the corporate’s business strategic plans51. We chose to use corporate CSR reports as our primary research sources for the following reasons. First, CSR reports per se are one kind of corporate communication that conveys the voice of the companies to both internal and external audiences. Second, purchasing voluntary carbon credits is part of corporates’ CSR strategy, and CSR reports therefore fits this research need, since the intention of studying the corporates’ purchasing behavior of voluntary carbon credits is their motivation, instead of what have they done. In addition, CDP, acting as a not-for-profit organization, provides a channel for large companies globally to participate an standard annual questionnaire52,53 that includes detail on emissions and strategies to address climate change, as well as information on offset projects they invested in during the reporting year.

Data

Company selection

The focus of this research is on companies that have engaged in carbon offsets activities. The year 2017 was selected as it allowed us to obtain a relatively comprehensive list of companies from two datasets, and it was also the year following the Paris Agreement’s entry into force, making it a suitable case to study post-Paris corporate sustainable investment. Companies were identified from the CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2018, specifically Question C11.2 and C11.2a. Question C11.2 asked companies if they had originated or purchased any project-based carbon credits during the reporting period, while C11.2a asked companies to provide details on these credits. From this effort, 414 candidates were identified. We then excluded companies that purchased offset credits to meet compliance requirements or acted as originators of carbon offsets, leaving us with a total of 306 companies for analysis.

CSR reports

Once the target set of corporates were identified, we verified the availability of the CSR reports (free-standing or published jointly with annual reports) using the Corporate Register and the Sustainability Disclosure Database. After the list of companies was finalized, the most recent CSR report was downloaded from corporateregister.com or directly from the companies’ websites. Finally, we obtained 306 CSR/sustainability reports and corporate annual reports. However, after having reviewed all 306 reports, only 186 reports were retained in the final sample. We dropped 120 companies from our sample because their CSR reports did not mention related information about purchasing carbon offsets. A detailed comparison table between these two groups can be found in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Sectoral data

These companies were then classified by industry using the Bloomberg Industry Classification Systems (BICS). In addition, corporate characteristic information, such as headquarters location, primary working currency, number of employees, annual revenue, net income, total assets, operating, and investing, was also obtained from Bloomberg Company Profile 2018.

Project characteristics

Within 186 corporates, we identified from the CDP data 534 projects executed in 28 countries, 12 sectors, 39 industries, and 73 sub-industries. We presented the distribution of project types aggregated at country or regional level in Fig. 1. These 534 projects accounted for 16.2 MtCO2e, which is about one third of the total volume of transactions in the voluntary market of that year. Supplementary Table 7 lists the descriptive statistics of the 186 companies in our dataset. In aggregate, these companies represent $3.5 trillion in revenue, and $0.4 trillion in profits, $3.1 trillion in total assets, and a workforce of 9 million people worldwide. When we compared the data to the list of global Fortune 500, these 186 companies represent one third of the value created by the Fortune 500 companies in the year of 2018. In conclusion, companies in our sample are quite significant offset buyers, and they can be a representative sample to study corporate investment decisions.

Strategy

Methodologically, we adopted the mixed-method research design by combining the inputs of corporate CSR reports and CDP offsets projects to assess the underlying motivations and decisions for corporates to invest in offset projects. “Mixed methods” is a research approach of using both quantitative and qualitative data collectively within the same study to conduct analysis53,54. The essential element of this method is data linkage, or data integration at an appropriate stage53,55.

This paper fulfills the precondition of data linkage and data integration. First, there was a natural linkage between the CSR reports and the CDP Climate Change Questionnaire. They were the same groups of companies reporting different aspects of the offset investment to different audiences and stakeholders. As a result, corporate-level data was constructed from the CSR reports studying the motivations of investment behavior through a defined coding strategy. Meanwhile, the project-level data was extracted from the self-reported CDP data to study the project-specific issues. Second, the two sets of data were integrated into Nvivo 12 through the “case” function. Nvivo is a qualitative data analysis (QDA) computer software package produced by QSR International. Primarily, it is designed for qualitative analysis, but the additional “case” function enables researchers to conduct mixed-methods research. In this function, each individual company was treated as one “case” in the software, allowing analysis of interaction between the specific motivations and project characteristics. In this circumstance, corporate CSR reports act as interviews, and CDP data acts like survey responses. We combined these two datasets for individual corporations. In addition, sectoral data from the Bloomberg Company Profile and the BICS is applied to study corporate aggregated behavior. In conclusion, qualitative data was collected and analyzed first, then quantitative data was collected and used to test findings empirically.

Coding strategy

The first part of our study focuses on underlying motivations behind corporate offset investment behavior to address the first research question, and we have chosen to do a qualitative study using the content analysis. Content analysis is a common method used in qualitative analysis, which comprises a set of methods for systematically coding and analyzing qualitative data for examining trends and patterns in documents6,56. Originally taken from the consumer behavior and marketing field, this approach was later widely adopted in the social and anthropology field57. Recently, content analysis has been used in several studies that examined corporate environmental and social disclosures, as well as corporate risk disclosures58.

We conducted the content analysis of the 186 CSR reports by using a coding strategy to extract corporate motivations for offset investment. To create the coding strategy, we first compiled a wide-ranging set of motivations (we called them metrics in our coding strategy) based on the literature. We began with a deductive content analysis of a pilot study of 20 companies to see whether motivations from the pilot study were closely aligned with those from the literature. We found that most of these motivations would fit under the list we compiled, whereas one motivation that relates to SDGs was not on the list. We agreed that the motivation of supporting SDGs, although not mentioned in the literature, was an essential piece that can perhaps describe the current trend of corporate motivations. Thus, we added it to the coding strategy. Later, when reviewing the CRS reports from the pilot sample, we started to see these motivations could be aggregated into three main themes to describe the underlying motivations behind corporate investment behavior. As a result, we identified three main themes of motivations, namely “company carbon management and efficiency,” “company values,” and “company market competitiveness.” At this point, the preliminary coding strategy was eventually defined as in Supplementary Fig. 4. Once the coding strategy was defined, the coding was applied to the full sample. We made small revisions during the coding process.

This technique of content analysis enables assessment of the frequency with which companies undertake different motivations and sub-motivations to invest in offset projects. It also provides understanding of corporate strategies to enhance the quality and impacts of the projects that they have invested in.

Hypotheses

Due to the dual features of carbon offsets, we developed two hypotheses based on empirical literature rather than on theoretical considerations. Anderson and Bernauer’s study of corporate motivations through interviews and online surveys found that if only from reducing GHG emissions’ perspectives, companies were motivated by the economic efficiency offset projects, which deliver cheaper carbon credits at a lower cost22. Ecosystem Marketplace conducted annual market surveys with a focus on corporate voluntary carbon offset activities using the CDP database. They found that offsetting investments primarily served the purpose of companies choosing to meet a voluntary emission reduction target. Beyond that, it could also help companies to derive value from their offset portfolio through offset purchases—particularly when companies were looking to bring in “beyond climate” benefits, such as co-benefits to the society16,20. Lovell et al. identified three narratives to explain why offset organizations purchase voluntary offset credits: “quick fix for the planet” is based on the science of climate change, “global-local” connections focus on side benefits, and “avoiding the unavoidable” is based on drivers of increasing greenhouse gases26. Two of the three motivations are derived from the logic of emission reductions.

Carbon offsetting has the potential to contribute to a range of other benefits that can fit into a broader goal for corporate social responsibility. Several studies have explored the utilization of VCO projects by companies to achieve specific sustainable development benefits. This extends beyond the primary motivation and enters what is commonly referred to as the “sustainability sweet spot,” where co-benefits play a crucial role in enhancing corporate social responsibility and contribute to the growing trend of companies being willing to pay a premium for projects with better co-benefits. Another study conducted interviews among one carbon offset consulting firm with four of its customers but the data limitations constrained them from drawing a broader conclusions on the motivations of these corporate buyers10.

Furthermore, emission offsets have two embedded features when they are traded in the form of carbon credits. First, carbon offsets are a commercial good that can be purchased in the voluntary carbon markets. Consumer behavior can play an important role in the purchasing process. Second, carbon offsets are also an uncommon intangible good, which means that consumer behavior differs from behavior in relation to conventional goods under certain circumstances. Therefore, based on the qualitative analysis we conducted in the previous section, we can group the three motivations we found and assign them into the two hypotheses. We can then test the hypotheses based on the combined project characteristics and price data.

Balancing test between the M1, M2, and M3 groups

We acknowledge that diverse corporate characteristics, such as size, revenues, net income, total emission status, etc., might also have influence in their decision of offset investments. Simply looking at the correlation might miss these factors. However, we conducted tests to assess the balance of three different groups of companies before we further calculate the t-test. We present the results of the standardized differences in Supplementary Table 8. Overall, these groups are quite balanced, with only two or three variables out of 10 not being balanced. We can conclude that there is adequate balance among these groups of companies. We also conducted a hedonic model with 37 companies who reported the purchased prices of offsets in 2018. We report the results in Supplementary Table 9. We also found that these corporate features do not statistically have an impact on the offset prices.

Robustness

The standards and registry infrastructure are an essential piece of voluntary offset markets in standardizing carbon credits and proving the legitimacy of these credits by third-party verification. Additionality has been an ongoing concern from environmentalists and some buyers who hold skeptical attitudes towards carbon offsetting. To address the concerns, companies purchase the carbon offsets that meet the highest possible standards to avoid criticism from the media and environmentalists5.

Currently, there are five common VCO standards in the market, where the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Gold Standard account for roughly 66 percent and 20 percent (Supplementary Fig. 5) of the transacted offset volumes respectively based on a market survey59. Standards serve the purpose of issuing offsets to a VCO project if the general criteria set by the standards are met, mainly refer to the qualification of validation and verification. On top of these two-primary qualifications, a few standards will issue add-on certification to offer buyers “charismatic” offsets that emphasize co-benefits60. For example, Gold Standard certifies positive co-benefits, and the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standard (CCBS) certifies positive social and biodiversity impacts. In addition, the American Carbon Registry (ACR), listed as the highest priced standard, is recognized for environmental integrity and innovation21.

Figure 7 underscores these insights. First, motivations of company values (M2) and company market competitiveness (M3) drove companies to invest in offset standards either with a higher offset price or having more “charismatic” features, compared to companies with the motivation of carbon management and efficiency. In the boxes (diagonal with thick borders) of the three out four highest-priced offset standards with add-on co-benefits (Gold Standard, CCBS and VCR), there is a statistically significant difference at the number of offset standards being purchased by M1 companies compared by M2 and M3 companies. Companies were indifference in preference for offset standards when moving towards the right corner of the diagonal line (offset credit became cheaper with no add-on features are attached, and there is no statistically significant difference among these four motivations towards offset standards).

When we compare the differences of standards purchased, we always subtract the lower-priced offset standard from the higher-priced standard. Green cells indicate that corporates purchase more from offset standards with a higher average price. Rose-colored cells show that the preference over offset standards fits the assumption that buyers buy more offset standards due to the low price of the standards. T-test results are from comparing the difference of the average number of projects (number of transactions) within the respective project offset standards, invested by companies driven by separate motivations. Note 1: The test results compare the difference of the average number of projects (number of transactions) within the respective credit standard, invested by companies driven by separate motivation.

Second, companies with the motivation of carbon management and efficiency (M1) were attracted by the low-priced offset standards, and they tended to purchase more offsets from this group of standards, namely VCS, CAR, and CDM. The average price of offset credits from this group is below $2/tCO2e. In the boxes (white) that had only one or two yellow-colored cells, at least one of the yellow-colored cells resided in the M1 companies. Yellow-colored cells show that the lower-priced standard was chosen. Thus, when M1 companies faced the investment decision between two offset standards, the one with a lower price had a higher chance to be chosen by M1 companies.

Third, Gold Standard offset credits were favored over other standards by all types of companies, with only one exception, when Gold Standard was compared to VCS by M1 companies. There were two explanations. First, VCS is the most common standard in the voluntary carbon markets with a market share of 66 percent of total transacted credit volumes. Second, lower-priced VCS credits were favored by M1 companies, perhaps related to their tendency purchase relatively large accounts of credits.

Fourth, generally, corporate motivations show a large degree of consistency and orientation, which was aligned with the findings of the purchasing behavior on offset standards. M2 and M3 companies were willing to invest more on offset projects with better add-on features, and willing to pay these offset credits at a higher price. The investment decisions of the M1 companies are primarily related to the low-priced factor. However, when facing choices across project types, they intended to invest in renewable energy projects, which are not only cheap but also can deliver on potential local co-benefits. This observation suggests that co-benefits might be woven into a broader fabric of corporate social responsibility and the decision-making process for offset projects.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data are available on the GitHub from https://github.com/Jiehonglou/Integrating-Sustainable-Development-Goals-into-Climate-Finance-Projects.

Code availability

All data and models are processed in Stata 14.0 and Python. The figures are produced in Python and R. All custom code is available on Github from https://github.com/Jiehonglou/Corporate-Motivations-and-Co-benefit-Valuation-in-Private-Climate-Finance-Investments-Through-VOC.

References

United Nations. Closing Remarks “How the private sector can contribute to achieving the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda”. United Nations https://www.un.org/en/desa/closing-remarks-%E2%80%9Chow-private-sector-can-contribute-achieving-paris-agreement-and (2019).

Gibson, R. B. Voluntary Initiatives and the New Politics of Corporate Greening (University of Toronto Press, 1999).

Weizsäcker, E. U. von, Rosenau, J. N. & Petschow, U. Governance and Sustainability: New Challenges for States, Companies and Civil Society (Routledge, 2005).

Strasser, K. A. Do voluntary corporate efforts improve environmental performance? The empirical literature. Environ. Affairs 35, 25 (2008).

Bayon, R., Hawn, A. & Hamilton, K. Voluntary Carbon Markets: an International Business Guide to What They Are and How They Work (2009).

Dixon, R. & Challies, E. Making REDD+ pay: Shifting rationales and tactics of private finance and the governance of avoided deforestation in Indonesia: private REDD+ finance in Indonesia. Asia Pac Viewp. 56, 6–20 (2015).

Ehara, M. et al. REDD+ engagement types preferred by Japanese private firms: the challenges and opportunities in relation to private sector participation. Forest Policy Econ. 106, 101945 (2019).

Laing, T., Taschini, L. & Palmer, C. Understanding the demand for REDD+ credits. Envir. Conserv. 43, 389–396 (2016).

Parrotta, J., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C. & Grima, N. Forests, Climate, Biodiversity and People: Assessing a Decade of REDD+. (2022).

Bergqvist, M. & Lindgren, C. Environmental, social or economic sustainability: what motivates companies to offset their emissions? http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:740623/FULLTEXT01.pdf (2014).

Hart, S. L. & Milstein, M. B. Creating sustainable value. AMP 17, 56–67 (2003).

Savitz, A. & Weber, K. The Triple Bottom Line (Weber, 2014).

Kreibiehl, S. et al. SP1M5 Investment and Finance (2022).

Lozano, R. Towards better embedding sustainability into companies’ systems: an analysis of voluntary corporate initiatives. J. Cleaner Prod. 25, 14–26 (2012).

Anja, K. Carbon Offsets 101. 20, (2007).

Goldstein, A. Buying in: Taking Stock of the Role of Carbon Offsets in Corporate Carbon Strategies. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/buyers-report-2016-final-pdf.pdf (2016).

Pohl, M. & Tolhurst, N. Responsible Business: How to Manage a CSR Strategy Successfully (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Tolhurst, N. & Embaye, A. Carbon Offsetting as a CSR Strategy. vol. Chapter 19, Responsible Business: How to Manage a CSR Strategy Successfully (2010).

ICROA & Imperial College. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Carbon Offsetting. https://www.icroa.org/resources/Documents/ICRO2895%20ICROA%20online%20pdf_G.pdf (2014).

Goldstein, A. Bottom Line: Taking Stock of the Role of Offsets in Corporate Carbon Strategies. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/buyers-report-032015-pdf.pdf (2015).

Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace. Financing Emissions Reductions for the Future: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2019. (2019).

Anderson, B. & Bernauer, T. How much carbon offsetting and where? Implications of efficiency, effectiveness, and ethicality considerations for public opinion formation. Energy Policy 94, 387–395 (2016).

Goldstein, A. & Hamrick, K. Sharing the Stage: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2014. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/doc_4501.pdf.pdf (2015).

ICROA & Imperial College. Business Leadership on Climate Action: Drivers and Benefits of Offsetting. https://www.icroa.org/resources/Documents/ICRO4535%20Ofsetting%20Report%202017_FINAL.pdf (2016).

ICROA & University of Bristol. Insetting: Developing Carbon Offset Projects with a Company’s Own Supply Chain and Supply Chain Communities. https://www.icroa.org/resources/Pictures/ICROA%20Insetting%20Report_v300.pdf (2015).

Lovell, H., Bulkeley, H. & Liverman, D. Carbon Offsetting: Sustaining Consumption? Environ. Plan A 41, 2357–2379 (2009).

New Climate Economy. Unlocking the Inclusive Growth Story of the 21st Century: Accelerating Climate Action in Urgent Times. https://newclimateeconomy.report/2018/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2018/09/NCE_2018_FULL-REPORT.pdf (2018).

Tiffany & Co. Tiffany & Co._2017 Sustainability Full Report.pdf. https://media.tiffany.com/is/content/Tiffany/2017_Tiffany_Sustainability_Full_Report (2017).

Marui Group Co., Ltd. Marui Group Co., Ltd._Co-Creation Sustainability Report 2017. https://www.0101maruigroup.co.jp/en/sustainability/pdf/s_report/2017/s_report2017_ena4.pdf (2017).

EcoRodovias Infraestrutura e Logística SA. EcoRodovias Infraestrutura e Logística SA_Sustainability Report Ecorodovias 2018.pdf. (2019).

Hultman, N. E., Lou, J. & Hutton, S. A review of community co-benefits of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab6396 (2019).

Lou, J., Hultman, N., Patwardhan, A. & Qiu, Y. L. Integrating sustainability into climate finance by quantifying the co-benefits and market impact of carbon projects. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 137 (2022).

Netter, L., Luedeling, E. & Whitney, C. Agroforestry and reforestation with the Gold Standard-Decision Analysis of a voluntary carbon offset label. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 27, 17 (2022).

Parnphumeesup, P. & Kerr, S. A. Willingness to pay for gold standard carbon credits. Energy Sources, Part B: Econ, Plan. Policy 10, 412–417 (2015).

Depoers, F., Jeanjean, T. & Jérôme, T. Voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions: contrasting the carbon disclosure project and corporate reports. J. Bus. Ethics 134, 445–461 (2016).

Sullivan, R. & Gouldson, A. Comparing the climate change actions, targets and performance of UK and US retailers: comparing the climate actions of UK and US retailers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 23, 129–139 (2016).

Kreibich, N. & Hermwille, L. Caught in between: credibility and feasibility of the voluntary carbon market post-2020. Climate Policy 21, 939–957 (2021).

Macquarie, R. Searching for trust in the Voluntary Carbon Markets. Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/searching-for-trust-in-the-voluntary-carbon-markets/ (2022).

Cames, M. et al. How additional is the Clean Development Mechanism? Analysis of the Application of Current Tools and Proposed Alternatives (2016).

Ellis, J. & Kamel, S. Overcoming barriers to clean development mechanism projects. OECD, 1–50 (2007).

Gillenwater, M. What is additionality? Part 1: A long standing problem. in vol. Discussion paper No. 001, Version 2, (Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, 2011).

Haya, B., Ranganathan, M. & Kirpekar, S. Barriers to sugar mill cogeneration in India: Insights into the structure of post-2012 climate financing instruments. Climate Dev. 1, 66–81 (2009).

Hayashi, D. & Krey, M. Assessment of clean development mechanism potential of large-scale energy efficiency measures in heavy industries. Energy 32, 1917–1931 (2007).

Heuberger, R., Brent, A., Santos, L., Sutter, C. & Imboden, D. CDM Projects under the Kyoto Protocol: A Methodology for Sustainability Assessment – Experiences from South Africa and Uruguay. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 9, 33–48 (2007).

Lou, J. Prioritizing local benefits in climate projects yields higher investment. Nature Portfolio Earth and Environment Community http://earthenvironmentcommunity.nature.com/posts/title-prioritizing-local-benefits-in-climate-projects-yields-higher-investment (2022).

Michaelowa, A. Interpreting the Additionality of CDM Projects: Changes in Additionality Definitions and Regulatory Practices over Time. In Legal Aspects of Carbon Trading : Kyoto, Copenhagen, and beyond, 248–271 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Purohit, P. CO2 emissions mitigation potential of solar home systems under clean development mechanism in India. Energy 34, 1014–1023 (2009).

Purohit, P. & Michaelowa, A. Potential of wind power projects under the Clean Development Mechanism in India. Carbon Balance Manag. 2, 8 (2007).

Restuti, D. & Michaelowa, A. The economic potential of bagasse cogeneration as CDM projects in Indonesia. Energy Policy 35, 3952–3966 (2007).

Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace. State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2021. (2021).

Tate, W. L., Ellram, L. M. & Kirchoff, J. F. Corporate social responsibility reports: a thematic analysis related to supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 46, 19–44 (2010).

Ben-Amar, W. & McIlkenny, P. Board effectiveness and the voluntary disclosure of climate change information: BOARD effectiveness and voluntary climate change disclosures. Bus. Strat. Env. 24, 704–719 (2015).

Shorten, A. & Smith, J. Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base. Evid. Based Nurs. 20, 74–75 (2017).

Creswell, J. W. & Clark, V. L. P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. (SAGE Publications, 2017).

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W. & Stick, S. L. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods 18, 3–20 (2006).

Stemler, S. An Overview of Content Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 7, 137–146 (2001).

Kolbe, R. H. & Burnett, M. S. Content-analysis research: an examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. J. Consum. Res. 18, 243–250 (1991).

Goldstein, A., Turner, W. R., Gladstone, J. & Hole, D. G. The private sector’s climate change risk and adaptation blind spots. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 18–25 (2019).

Hamrick, K. & Gallant, M. Voluntary Carbon Markets Insights: 2018 Outlook and First-Quarter Trends. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Q12018VoluntaryCarbon.pdf (2018).

Conte, M. N. & Kotchen, M. J. Explaining the price of voluntary carbon offsets. Clim. Chang. Econ. 01, 93–111 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the seminar participants at the Center for Global Sustainability of the University of Maryland for their suggestions and recommendations during the preparation of this manuscript. Open Access funding are provided by the Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. designed the original study, conducted the entire analysis, and wrote the paper. N.H. provided guidance on the initial co-benefits project with the methodology design and contributed to the writing of the paper. N.H., A.P., and I.M. contributed to the design of the study and provided guidance during the analysis and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, J., Hultman, N., Patwardhan, A. et al. Corporate motivations and co-benefit valuation in private climate finance investments through voluntary carbon markets. npj Clim. Action 2, 32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-023-00063-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-023-00063-4

This article is cited by

-

Towards more effective nature-based climate solutions in global forests

Nature (2025)

-

Assessing airline communication for voluntary carbon offsets

npj Sustainable Mobility and Transport (2025)

-

Carbon credit does not buy moral credit: moral licensing and perceived hypocrisy of carbon emission offsetting and reduction

Climatic Change (2025)

-

Is Corporate Offsetting a Good Idea?

European Business Organization Law Review (2025)