Abstract

Climate advocates look optimistically to policy feedback as a mechanism for locking-in a decarbonization policy trajectory, but little research has examined whether and how climate legislation creates constituencies that could provide future political support. This article focuses on incentive programs supporting investment in solar PV and the potential for policy feedback through participating households. We first develop a framework of feedback potential that considers the volume and partisanship of incentive program beneficiaries and their distribution across electoral districts. We then apply the framework to New York State’s solar PV incentive program, which enabled over 140,000 households to install solar PV. We find that the number of solar PV incentive beneficiaries is positively associated with Republican vote share, suggesting potential for a strong pro-solar constituency in the pivotal, Republican-led districts. Within electoral districts, however, beneficiaries skew Democratic, raising questions about the direction of policy feedback. The results carry implications for the kind of politics that incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act may set in motion in the coming years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the face of considerable political barriers to climate action, policy feedback has emerged as a key framework for climate advocates for designing a political strategy to accelerate the energy transition and “lock-in” a decarbonization trajectory1,2,3,4,5. The theory of policy feedback holds that the passage of specific legislation directly affects the attitudes, interests, and behavior of the electorate and other actors that can influence policy outcomes6,7,8. Initial legislative victories can thus create a constituency to bolster political power in future contests, allowing policy expansion and entrenchment9. Despite the prominence of the policy feedback framework in both scholarly and policy discourses about achieving a rapid energy transition, little research has directly examined whether and how actual climate legislation creates the types of electoral constituencies that would be effective in shaping future policy trajectories.

Here, we focus attention on a particular type of legislation—financial incentive programs targeted at end-consumers—and focus on potential feedback through the electorate. Financial incentive programs are a pillar of energy transition policy in the United States. Such programs have, for example, played an instrumental role in the emergence of self-sustaining electric vehicle (EV) and residential solar photovoltaics (PV) industries10,11 and are a central piece of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the signature climate bill passed by the Biden administration in 202212. Researchers have suggested that broad public benefits from incentive programs may create important political support for entrenching energy transition policies, especially in a political environment marked by high levels of partisan polarization13,14,15.

We draw on the theory of policy feedback to, first, develop a framework for conceptualizing the potential for positive policy feedback that considers (1) the existing policy preferences of partisan elites, (2) the volume of beneficiaries, (3) the partisan make-up of the beneficiaries, and (4) the distribution of beneficiaries across empirical electoral districts. We then apply the framework in the context of an incentive program that supported the installation solar PV among 142,046 households in New York State. Across three types of electoral districts, US House of Representatives, NYS Assembly, and NYS Senate, we find that Republican-led districts, which could be decisive for future energy transition policy, have more PV incentive beneficiaries, suggesting a strong pro-solar constituency, but beneficiaries skew Democratic, raising concerns about the direction of policy feedback. We conclude by discussing the implications of these findings for the potential role of policy feedback in shaping a decarbonization policy trajectory in the United States.

Policy feedback theory holds that the end of one policy contest provides essential conditions for the next one7,16. The theory draws attention to how specific elements of enacted policies enable and constrain future political action. From this perspective, it is essential to consider the sequence of policymaking, because early policy outcomes can either reinforce or undermine future policy trajectories1. The ramp up of military spending during the Cold War provides an illustrative example. The federal defense dollars created public support for the military-industrial complex by building a broad, geographically distributed coalition composed of the beneficiaries of federal programs, including defense workers, military contractors, labor unions, and current and retired member of the military17. The so-called “warfare state” thus provided financial security for a large fraction of Americans and across every congressional district, ensuring that any proposed cut to defense spending would face a formidable political challenge. A second, canonical example of policy feedback is the Social Security Act of 1935. Although its passage was highly contested at the time, once in place, the broad base of material beneficiaries ensured that the programs became politically entrenched18.

A parallel strategy may be available for building political support for an energy transition9,19. Policies that provide subsidies for renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies offer a straightforward example of how this might work. The financial incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles (EVs) increase the number of EVs on the road, but also increase the numbers of EV drivers and of workers at EV manufacturing plants, all of whom may support future initiatives to develop reliable EV-supporting infrastructure. Seen through the lens of policy feedback, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) could serve as a cornerstone of this political strategy. According to widely cited estimates, IRA will provide up to $1.1 trillion to U.S. households, businesses, and local governments to make investments in clean energy and energy efficiency12. In the process, the policy could expand its political constituency by giving firms, workers, unions, and end-consumers a material stake in the energy transition.

In this study, we will limit the scope of attention to mass politics (i.e., the electorate), setting aside the mobilization of organized interests in policy feedback, which has received attention elsewhere (e.g., ref. 4). Researchers have identified several specific ways that public policies shape political participation and attitudes among the mass public. Scholars distinguish between resource and interpretive policy feedback effects20. Resource effects refer to the material benefits and costs that the policy implies for individuals. In this case, policies affect political behavior by raising the material stakes. Characteristics of program design influence the efficacy of resource effects. These include the program’s size and ability of beneficiaries to recognize the benefits and to trace them to their source, the physical proximity of the beneficiaries, and modes of program administration7. Interpretive effects have a subjective element and depend on the process of political learning20. Interpretive effects depend on the message that individuals receive when they engage with the government program directly. Interpretive effects also depend on the policy’s perceived effects for the broader community (such as one’s town or the country as a whole), which individuals develop through political learning processes like engagement with mass communication and cues from elites20.

Political polarization presents a unique set of challenges to designing legislation that yields positive policy feedback3,21. Political polarization in the United States has been accompanied by a politics that is becoming more nationalized, wherein national party elites have increasingly strong influence on the beliefs and preferences of partisans, while material interests and local context has diminished effect22. Relatedly, the rise of “negative” polarization—an affective hostility toward the out-party group—has made it more difficult for the party that passes a particular program to win out-party adherents even when the policy provides local benefits23,24. This pattern suggests that positive policy feedback will depend critically on managing the interpretive effects of legislation.

Policies thus shape the boundaries of their own political constituency in material and symbolic ways. But, in the context of a politically polarized public, what characteristics of a policy constituency enable it to provide effective political support for entrenching or expanding the policy? This is a critical question for understanding whether and how initial policies can anchor ambitious decarbonization policy trajectories. The present study evaluates the policy feedback potential from a New York State financial incentive program designed to support household investment in solar PV systems. Such programs exist across many states and are also a key component of IRA, which includes incentives for PV and for many other renewable and energy efficient household technologies12.

Next, we draw on policy feedback theory and explicitly incorporate political geography to develop a set of expectations about what constitutes an effective program constituency. Individuals who install a solar PV system through a financial incentive program gain a significant material benefit. They also learn about the solar industry and typically gain a positive, first-hand experience with the technology. For these reasons, beneficiaries of these programs could increase their support for future expansion and entrenchment of solar-friendly legislation13,14. Past empirical research tends to focus on the volume8 and, to a lesser extent, partisanship13 of constituencies that new policies mobilize. We argue, however, that a complete framework for assessing the potential for an effective policy feedback constituency must additionally consider the existing preferences of partisan elites and the distribution of beneficiaries across empirical electoral districts. These two factors are present in theoretical treatments of policy feedback theory17,18, but are rarely explicitly incorporated in empirical studies of policy feedback and mass political behavior. Below we develop a framework for evaluating policy beneficiaries’ potential to form an effective constituency for policy feedback that incorporates all four factors: (1) the existing policy preferences of partisan elites, (2) the volume of beneficiaries, (3) the partisan make-up of the beneficiaries, and (4) the distribution of beneficiaries across empirical electoral districts.

First, the existing policy preferences of partisan elites form an essential context for evaluating policy feedback. Under extreme political polarization, local elected officials tend to default to the national party’s position on pollical issues, and this default preference is especially strong for highly salient political issues22. This makes it easier to secure future support for related policies among co-partisan elected officials and concentrates the need for building support for the program among out-partisans. In national debates, the Republican Party has tended to oppose subsidies for renewable energy technologies, especially when such supports are cast as climate change mitigation efforts25. The Democratic Party, on the other hand, has been overtly supportive of policies that incentivize investment in renewable energy26. The significant influence of national partisan preferences means that local Republican officials will require more pressure from their constituents to support (or at least not oppose) future solar-friendly legislation, whereas Democratic officials may support such legislation without local pressure.

Next, the volume and partisan composition of program participants within specific electoral districts determine the level of influence that the solar constituency will play. In terms of size, elected officials are more likely to respond to a larger, well-resourced segment of their electorate than a smaller and less resourced one27. We expect the volume of solar incentive program participants to track with several features of the natural, built, and social environment that have been found to be influential for PV adoption. Homeowner-occupied, low-rise single-family houses are best suited for installing residential solar PV systems28. Relatedly, a comprehensive study of residential solar installations in the United States found an inverse-U-shaped relationship between population density and solar deployment rates, with the peak adoption rates in suburban communities29. Socio-economic factors also matter, including residents’ income, education, and race or ethnicity13,30. We expect electoral districts where these factors are more favorable to have larger numbers of households taking advantage of the solar PV incentive program.

In terms of partisan composition, elected officials are more likely to respond to the preferences of co-partisan constituents than to out-partisans. The major electoral risk facing most elected officials in the U.S. today is from a primary challenge31. This electoral reality ensures that elected officials depend primarily on support from co-partisans for re-election. Solar incentive beneficiaries will only form an effective policy constituency, if enough of them share the party affiliation of their elected officials. This is particularly important in Republican-led districts, where officials may oppose future solar-friendly policy as a default. Indeed, if solar PV adopters skew dramatically Democratic, it could reinforce a politicized view of the policy and entrench Republican opposition.

Previous research appears to suggest that solar PV enjoys support from both Republican and Democratic voters. Studies that examine the partisan gap in household adoption of solar PV find only a modest gap favoring Democrats13,15. Mildenberger and co-authors interpret this result as implying a “growing constituency of relevance for policymakers on both sides of the ideological aisle.”13 But this previous research does not consider how solar PV adopters are distributed across empirical electoral districts. Political geography is essential to consider, because the statistical estimate of a modest partisan gap found in previous research can imply very different policy feedback potential.

To appreciate the importance of political geography, consider the three stylized patterns of electoral districts presented in Fig. 1. Each pattern includes two electoral districts a Republican-led one (top) and a Democrat-led one (bottom). The square cells in each district represent the district’s voters, colored red and blue for Republican and Democratic supporters, respectively, and the sun symbols indicate solar PV adopters (and incentive beneficiaries) among the electorate. Note that each two-district pattern in Fig. 1 has the same total volume of solar adopters (20) as well as within-district parity in partisan PV adoption (i.e., each district has an equal proportion of Republican and Democrat PV adopters). However, the structure of between-district differences in adoption rates implies different policy feedback potential. In Pattern 1, the Republican-led district, has no PV adopters at all—partisan parity exists because no one adopts. No program beneficiaries are thus available in the district that most requires public support. By comparison, Patterns 2 and 3 are expected to have greater potential for policy feedback. In Pattern 2, each district has the same number of adopters, forming a modestly sized constituency in both districts, and in Pattern 3, all adopters concentrate in the Republican-led district, forming a potentially important, bipartisan constituency to sway the elected official in greatest need of political pressure.

Each pattern shows two electoral districts a Republican-led one (top) and Democrat-led one (bottom). The cells in each district represent the district’s electorate, colored red and blue for Republicans and Democrats, respectively, and the sun symbols indicate solar PV adopters (and incentive beneficiaries) among the electorate. Note that each pattern has the same total volume of solar adopters as well as within-district parity in partisan PV adoption (i.e., each district has an equal proportion of Republican and Democrat PV adopters). See text for details.

While in Fig. 1 we assume that Republican and Democratic voters are equally likely to benefit from the solar incentive program, empirical studies document substantial between-community variation in the partisan gap as well as an average gap slightly favoring Democrats13. Therefore, the magnitude of the partisan gap within specific electoral districts could further influence the political potential of the district’s solar beneficiaries. Consider the three stylized examples of Republican-led districts in Fig. 2, each one with ten PV installations. A Republican elected official may be pressured by a Republican or a bipartisan solar constituency (as in Pattern 1 and 2, respectively), but the effect of a primarily Democratic constituency (as in Pattern 3) could be the opposite, reinforcing the view that solar PV subsidies represent a politicized program favored only by Democrats and unpopular with the Republican base.

The cells in each district represent the district’s electorate, colored red and blue for Republicans and Democrats, respectively, and the sun symbols indicate solar PV adopters (and incentive beneficiaries) among the electorate. Note that each pattern has the same total volume of solar adopters. Pattern 1 has a partisan gap favoring Republican voters, Pattern 2 has no partisan gap, and Pattern 3 has a partisan gap favoring Democratic voters.

The goal of the empirical analysis that follows is to assess the policy feedback potential from one prominent solar incentive program, taking into account the four elements highlighted here: of (1) volume, (2) partisanship, and (3) political geography, and (4) focusing special attention on the solar constituencies in Republican-led districts, which are expected to require more constituent pressure to support energy transition policies.

We analyze the composition and distribution of households who took advantage of New York State’s financial incentive program to install a residential solar PV system. Deployment of residential solar technology is a key component to rapid energy transition scenarios in the U.S. and globally32,33. A solar PV incentive program offers an ideal setting for evaluating the potential for positive policy feedback for several reasons. First, such programs confer a large financial benefit to participants34. The benefit consists of large upfront savings on the system purchase, state and federal tax credits, and continued savings on the electricity bill, including through a net metering arrangement that pays New Yorkers for extra power they produce. Second, the benefit is easily traceable to government policy. Solar installers prominently advertise the state and federal incentives, making it clear to the solar-installing homeowner that they are beneficiaries of a government program. Finally, there is potential for powerful interpretive effects. Homeowners who install solar generally have positive experiences, finding their system to be reliable and cost effective. Positive experiences with renewable energy may lead homeowners to be more receptive to messages that emphasize the feasibility and imperative of energy transition policy14.

Results

Who are the beneficiaries of the solar PV incentive program in New York and might they coalesce into a potent policy feedback constituency in future policy contests? To answer this question, we organize the analysis at the level of three different types of electoral districts: U.S. Congressional Districts, New York State Senate Districts (the upper legislative house), and New York State Assembly districts (the lower legislative house). The New York State Legislature and the U.S. Congress will play pivotal roles in deciding the future of decarbonization efforts. Across the different electoral districts, we measure (1) the volume of solar PV program beneficiaries and (2) their partisan affiliations. See the Methods section for details about the data and measurement.

We first examine the volume of PV projects across electoral districts. Figure 3 reports the relationship between district partisanship, measured as the Republican vote share in the 2020 presidential election, and the (logged) number of solar PV installations in the electoral district. Across all three types of electoral districts, greater Republican vote share is associated with greater participation in the PV incentive program. Among U.S. Congressional districts and NYS Senate districts, three of the top four districts with the highest solar deployment levels are led by Republican elected officials. The top two highest-deploying NYS Assembly districts are also Republican-led.

The relationship is presented separately for (a) U.S. Congressional districts, (b) NY State Assembly districts, and (c) NY State Senate districts. Points are colored according to party control (the single grey point if for an Assembly District for which party control could not be established). OLS regression line shown with 95% CIs.

It appears, therefore, that Republican electoral districts have a larger pool of individuals who could form a political constituency in support of future solar-friendly policies. The observed pattern is not necessarily attributable to partisan preference for solar PV, because electoral districts differ in their housing stock, socio-demographic make-up, and other factors previously found to affect PV adoption rates. To better understand the relationship between district partisanship and volume of solar PV adopters, we fit negative-binomial count models predicting the number of PV installations in an electoral district as a function of Republican vote share, adjusting for the district’s population density and its square, the rate of homeownership, and median income. Table 1 reports the results. The positive relationship between Republican vote share and solar PV deployment (Model 1 for each type of district) disappears after adjusting for the included co-variates (Model 2). In fact, the coefficient on Republican vote share is negative in the adjusted models across district types, although it is only statistically significant for NYS Assembly districts, where the sample size is largest (n = 139). Confounding the relationship between vote share and solar PV adoption were differences in population density and homeownership rates between Republican- and Democratic-leaning electoral districts. In line with previous findings, we estimate a curvilinear effect of population density, with middle-density, suburban-style communities hosting the most solar PV systems29. High-density, urban areas, which describes many electoral districts that are Democratic strongholds, have much lower PV installation rates. Low-density, rural areas also have lower rates, but this describes a relatively small number of electoral districts overall. Homeownership rates also positively predict PV installations, but the effect is only statistically significant for NYS Assembly districts.

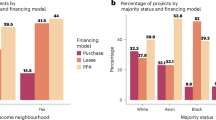

Next, we examine the partisan composition of the PV adopters in each electoral district. Are PV adopters in Republican-led congressional districts representative of the district’s Republican-leaning electoral constituency? Or are PV adopters more likely to be Democrats? To assess the partisan balance of PV-installing households, we use the three matched-samples, which pair each household that took advantage of the PV incentive program with a randomly selected, non-participating household from the same district. If beneficiaries of the PV incentive program are representative of the electoral constituency, then we should expect an approximately equal distribution of partisan affiliations in the adopting and non-adopting sets of households. In each district, we calculate the average homeowner party affiliation proportions for PV adopting and non-adopting households.

Figure 4 plots the difference between these proportions across electoral district. In each plot, bars to the right of zero indicate that PV adopters in that district were more likely to be Democrats than randomly sampled non-adopters and bars to the left of zero indicate that PV adopters were less likely to be Democrats than the random sample of households. To reduce noise in the presented results, we limit the plots to districts with at least 200 PV installations. The bar colors in the plots identify the party of the elected official of each district. The pattern is unambiguous— except in a very small number of districts, PV adopting households are more likely to be Democrats than randomly selected households. Most notably, this result holds across all Republican-led Congressional (panel A), State Assembly (panel B), and State Senate districts (panel C). In many districts, the magnitude of these differences is substantial. The proportion Democrat is at least 0.10 higher among PV adopting households compared to non-adopters in three Republican-led Congressional districts, eleven Republican-led State Assembly districts, and six Republican-led State Senate districts. Of all Congressional districts, a Republican-led one has the largest imbalance—PV-adopting homeowners are 0.46 registered Democrats, whereas just 0.22 of randomly selected households are Democrats, a difference of 0.24.

The differences are presented separately for (a) U.S. Congressional districts, (b) NY State Assembly districts, and (c) NY State Senate districts. Positive differences indicate that PV-adopting households had higher proportions of homeowners registered as Democrats and negative difference indicate that non-adopting households had greater shares of Democrats. The color of each bar corresponds to the party of the local elected official (Republican = red; Democrat = blue).

Figure 5 presents the same set of plots showing the difference in proportion Republican between adopting and non-adopting households. There is clear evidence of a Republican imbalance as well. Republicans are underrepresented among PV adopters, relative to non-adopters in 76% of electoral districts, including in 63%, 63%, and 55% of Republican-led Congressional, NYS Assembly, and NYS Senate districts, respectively.

The differences are presented separately for (a) U.S. Congressional districts, (b) NY State Assembly districts, and (c) NY State Senate districts. Positive differences indicate that PV-adopting households had higher proportions of homeowners registered as Republicans and negative difference indicate that non-adopting households had greater shares of Republicans. The color of each bar corresponds to the party of the local elected official (Republican = red; Democrat = blue).

We quantify the average partisan imbalance between PV adopting and non-adopting households by using the set of matched datasets and regressing an indicator for PV adoption on household party affiliation shares using a linear probability model (LPM). Note that our goal here is not to estimate a causal effect of party affiliation, but simply to measure how representative, in terms of party affiliation, PV adopting-households are of the typical household in the electoral district. In addition to partisan preferences, the observed partisan gaps in PV adoption could be due to differences in homeowner characteristics (e.g., income, education), home characteristics (e.g., property type, home size). In other words, we are only concerned here with the composition of solar PV program constituency—who benefits, not why. For this analysis, we additionally break down the Democrat and Republican party affiliations by whether the voter recently participated in a primary election. Primary election participation indicates a more committed partisan and a more involved voter. The model also includes proportions of unaffiliated voters and Independent voters, as well as minor party affiliations, including the Working Families Party (a progressive third-party), Conservative Party (a party that positioned to the right of the Republican Party), the Green Party, and the Libertarian Party. Results are presented in Table 2.

The results are similar across the different types of districts. Consistent with previous findings13, households owned by individuals who are not registered to vote (the reference group) are least likely to have a solar PV system. Among homeowners registered to vote, Republicans are the least likely to install solar PV, with only minor differences between those who participated in the primaries and those who did not. Democrats are much more likely to take advantage of the PV incentive program than expected by chance. Households with 100% of owners who are primary-voting Democrats have a probability of being PV adopters between 0.15 and 0.17 higher (depending on the type of electoral district) than unregistered homeowners and non-primary Democrats have an increased probability in the 0.10–0.11 range. Minor parties suggest that there is a consistent gradient along the liberal-conservative dimension. Conservative Party affiliates are most like Republican party members, with coefficient estimates below all other types of voters except Republicans. Estimates for Independents and unaffiliated voters are between those of Republicans and Democrats, whereas Working Families Party and Green Party members, two parties positioned to the left of Democrats, have probabilities of being PV incentive beneficiaries that are consistently higher than even the primary-voting Democrats. Finally, Libertarian Party affiliates also have among the highest probabilities of using the incentive program to install solar—approximately on part with Working Families Party members.

The within-district partisan gaps favoring Democrats and other liberal parties are an important feature of the PV incentive program constituency, but it is also notable that Republican-led households still make up a sizeable share of PV adoptions in their respective districts. For example, although the Republican proportion of PV adopters does not reach the expected proportion based on the composition of the electorate, Republican PV adopters make up at least a third of all PV adopters in 5 of the 8 Republican-led Congressional districts, 22 of 43 Republican-led NYS Assembly Districts, and 9 of 20 NYS Senate Districts.

Discussion and conclusions

This article assessed the potential for policy feedback from a financial incentive program that supports household investment in renewable energy. We advanced a framework for measuring the potential effectiveness of a program constituency that considers the volume and partisanship of program beneficiaries, their distribution across empirical electoral districts, and the context of elite policy preferences. Applying the framework to the case of solar PV incentives, we found higher rates of program beneficiaries in districts that are more Republican, suggesting a potentially large pro-solar constituency in the politically important, Republican-led districts. Within districts, beneficiaries skew Democratic, however, which raises questions about the direction of policy feedback.

Our framework and findings extend recent efforts to empirically measure the advocacy potential of solar PV adopters. Whereas previous research focused only on within-community differences in PV adoption13, we highlight the theoretical importance of between-district differences as well and show that Republican-led districts hold an advantage in the volume of adopters, likely due to the more amenable housing stock found in such communities. Consistent with results by Mildenberger et al.13, we find that PV adopters tend to be more politically active than non-adopters, which suggests a higher potential for advocacy by adopters. Our results provide a more nuanced picture of primary-voting patterns among PV adopters, however. Mildenberger and colleagues13 reported a uniform effect of primary-voting on PV adoption across partisan affiliations, but we find that only Democratic primary voters are substantially more likely to be adopters compared to their non-primary voting counterparts. This suggests a somewhat less politically potent pro-solar, Republican constituency.

Our results carry important implications for the kind of politics that incentive-focused climate policies may set in motion. In the coming years, millions of Americans are slated to become beneficiaries of financial incentive programs funded by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the 2022 legislation earmarking billions of dollars to support household investment in solar PV, electric vehicles, energy efficient electric appliances, and home energy efficiency retrofits. It is critical to understand how these benefits will be distributed and how to manage the interpretive effects of these programs. This article offers a framework for thinking about the potential for feedback effects of this policy. From a benefits perspective, it is important to ensure that decisive electoral constituencies, including voters outside Democratic strongholds, receive financial support. Due to the relatively higher homeownership rates and more amenable housing stock for solar PV, in particular, there is good reason to believe that households in Republican-leaning districts will take advantage of the many home-improvement incentives. Electric vehicle adoption requires investment in charging infrastructure, and governments should be mindful to support investment across politically diverse regions. Equally important, however, are the interpretive effects—what voters come to subjectively believe about the program and its benefits for their community through experience with it as well as through engagement with political media. Government agencies implementing IRA must be mindful of possible political backlash. From this perspective, IRA incentives are much preferable to regulatory bans, such as bans of gas stoves, the mere mention of which produced immediate polarized backlash35. Because incentives through IRA produce direct savings and leave the choice with the homeowner, the program may help mute politicization and increase adoption by Republicans, who have been shown to be more attuned to the economic case for investment in energy technologies15.

We note some important limitations of our study that should be addressed in future research. We leveraged high-resolution data on PV adoption to estimate the volume and partisan make-up of beneficiaries, but we focused on a single state, New York, which leans heavily Democratic. There is important regional heterogeneity in New York that allows us to explore patterns in Republican strongholds, but it is still possible that dynamics may differ in states with different partisan make-ups as well as with different policy designs and implementations. Additionally, we did not test whether and how policy beneficiaries changed their political behavior, which is necessary to close the cycle of policy feedback. Future research should thus seek to measure the effect of policy benefits on attitudes and behavior, and it should pay particular attention to heterogeneity along partisan lines. A recent study of Swiss voters provides some initial evidence, showing that the perceived effectiveness of prior benefit-conferring policies strongly predicts support for carbon pricing and, critically, that observed density of EV chargers, a material benefit of a specific transition policy, increases public support for carbon pricing in the transportation sector14. Even besides individual-level changes in attitudes and political behavior, however, much work remains to show that policy beneficiaries coalesce into effective policy constituencies. An effective constituency requires organization. How might the presence of specific organizations or social movements help to create a collective identity and provide the infrastructure to mobilize support for the next round of energy transition policies? To understand the effectiveness of policy feedback as a political strategy for locking in a decarbonization trajectory, future research should explore this and related questions.

Methods

We measure program participation and partisanship at the household level by combining three sources of administrative records. First, we used records from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) to identify households participating in the solar incentive program. Second, we use a property file compiled from public tax assessment rolls and obtained from ATTOM Data Solutions, a company specializing in property information, to identify each residential property in New York State. Third, we obtained the voter registration file for New York State, which contains party registration information on each registered voter in New York State. We applied a probabilistic record-linking algorithm developed by Enamorado and colleagues36 to merge the three datasets, creating a household-level dataset that identifies for each household in the property file, each homeowner’s party registration (if registered to vote) and whether or not they received a solar PV incentive through NYSERDA to install a solar PV system as well as additional information about each solar PV projects. Next, for each electoral district, we identify the party of the local official elected in 2020 and the Republican and Democratic vote shares in the 2020 presidential election by aggregating precinct-level election results from the MIT Election Data and Science Lab37. Finally, using geographic coordinates of each property and/or project, we joined the linked household-level dataset with a geographic boundary file of each of the three types of electoral districts.

We note several data limitations that introduce measurement error and restrict the available sample for the household-level analysis. The NYSERDA dataset did not contain street address information for 3.3% of the installed PV projects. In such cases, we used the Zip code to assign the project to an electoral district. When the Zip code crossed district boundaries, we assigned a proportional fraction of the project to each overlapping district. Due to similarity of addresses, input errors, and unconventional address formats some PV projects could not be reliably matched to a unique record. In any record-linking algorithm, there is an inherent trade-off between accuracy and coverage. We prioritize accuracy, which yields lower measurement error of party affiliation, but also increases the rate of false negatives. We reliably matched 91,459 projects to a unique address in the property file (69% of all projects with complete address information), and thus our household-level analyses are limited to this sample. Although this decreases the size of the available sample, we do not expect the restriction to bias our results, because the failure to match a project is related to address quality and non-uniqueness, variables that should be unrelated to party affiliation.

The resulting data thus enable us to achieve our two measurement objectives: (1) to examine the distribution of the subsidized PV systems across electoral districts and (2) to compare the partisanship of adopting households relative to non-adopting households in each district. For the first objective, we use three electoral-district level datasets (one for each type of district) and fit count models to identify the association between the partisan vote share and the number of PV projects in the district receiving incentives. We also adjust models for a district’s demographic and built-environment characteristics, which we obtain from the 5-year 2020 American Community Survey (ACS). For our second objective, to compare the partisanship of adopting and non-adopting households, we construct three matched household-level samples, one for each type of district. For each sample, we pair a household that installed solar PV with a randomly selected household from the same electoral district that did not install solar PV (see ref. 13 for an analogous comparison strategy). If PV-installing homeowners are more likely to be Democrats than a randomly selected homeowner in the district, this would contribute to a local perception that the PV-incentive program primarily benefits Democrats and could signify a challenge to Republican support for solar-friendly policies.

Data availability

Addresses of solar PV projects in New York State are made available to the author through a non-disclosure data sharing agreement with NYSERDA and cannot be shared publicly. PV project information without addresses and contact information for making additional data requests are available at38. The author can make anonymized and/or aggregate data available upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to produce the figures and tables in the manuscript is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YDIKOC.

References

Meckling, J., Kelsey, N., Biber, E. & Zysman, J. Winning coalitions for climate policy. Science 349, 1170–1171 (2015).

Aklin, Mel, M. & Urpelainen, J. Renewables: The Politics of a Global Energy Transition (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2018).

Hacker, J. S. & Pierson, P. Policy Feedback in an Age of Polarization. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 685, 8–28 (2019).

Stokes, L. C. Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States. (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Lockwood, M. Policy feedback and institutional context in energy transitions. Policy Sci. 55, 487–507 (2022).

Skocpol, T. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Harvard University Press, 1992).

Campbell, A. L. Policy Makes Mass Politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 15, 333–351 (2012).

Flores, R. D. Do Anti-Immigrant Laws Shape Public Sentiment? A Study of Arizona’s SB 1070 Using Twitter Data. Am. J. Sociol. 123, 333–384 (2017).

Schmid, N. & Lumsden, C. Sowing the seeds of change: Policy feedback and ratcheting up in South African energy policy. Energy Policy 178, 113597 (2023).

Matisoff, D. C. & Johnson, E. P. The comparative effectiveness of residential solar incentives. Energy Policy 108, 44–54 (2017).

Münzel, C., Plötz, P., Sprei, F. & Gnann, T. How large is the effect of financial incentives on electric vehicle sales? – A global review and European analysis. Energy Econ. 84, 104493 (2019).

Bistline, J. E., Mehrotra, N. R. & Wolfram, C. Economic Implications of the Climate Provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2023, 77–182 (2023).

Mildenberger, M., Howe, P. D. & Miljanich, C. Households with solar installations are ideologically diverse and more politically active than their neighbours. Nat. Energy, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0498-8 (2019).

Montfort, S., Fesenfeld, L., Stadelmann-Steffen, I. & Ingold, K. Policy sequencing can increase public support for ambitious climate policy. Policy Soc. 42, 454–477 (2023).

Dokshin, F. A. & Gherghina, M. Party affiliation predicts homeowners’ decisions to install solar PV, but partisan gap wanes with improved economics of solar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2303519121 (2024).

Mettler, S. & Soss, J. The Consequences of Public Policy for Democratic Citizenship: Bridging Policy Studies and Mass Politics. Perspect. Polit. 2, 55–73 (2004).

Brenes, M. For Might and Right : Cold War Defense Spending and the Remaking of American Democracy (University of Massachusetts Press, 2020).

Campbell, A. L. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Political Activism and the American Welfare State (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Eicke, L. & Weko, S. Does green growth foster green policies? Value chain upgrading and feedback mechanisms on renewable energy policies. Energy Policy 165, 112948 (2022).

Jacobs, L. R., Mettler, S. & Zhu, L. The Pathways of Policy Feedback: How Health Reform Influences Political Efficacy and Participation. Policy Stud. J. 50, 483–506 (2022).

Pastashnik, E. Countermobilization: Policy Feedback and Backlash in a Polarized Age (University of Chicago Press, 2023).

Hopkins, D. J. The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized. (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Abramowitz, A. I. & Webster, S. The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century. Elect. Stud. 41, 12–22 (2016).

Mason, L. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Coley, J. S. & Hess, D. J. Green energy laws and Republican legislators in the United States. Energy Policy 48, 576–583 (2012).

Trachtman, S. & Meckling, J. The climate advocacy gap. Clim. Change 172, 24 (2022).

Butler, D. W. Representing the Advantaged: How Politicians Reinforce Inequality (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Gao, X. & Zhou, S. Solar adoption inequality in the U.S.: Trend, magnitude, and solar justice policies. Energy Policy 169, 113163 (2022).

Yu, J., Wang, Z., Majumdar, A. & Rajagopal, R. DeepSolar: A Machine Learning Framework to Efficiently Construct a Solar Deployment Database in the United States. Joule 2, 2605–2617 (2018).

Dokshin, F. A. & Thiede, B. C. Revised estimates of racial and ethnic disparities in rooftop photovoltaic deployment in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 6, 752–755 (2023).

Brady, D. W., Han, H. & Pope, J. C. Primary Elections and Candidate Ideology: Out of Step with the Primary Electorate? Legis. Stud. Q. 32, 79–105 (2007).

Creutzig, F. et al. The underestimated potential of solar energy to mitigate climate change. Nat. Energy 2, 17140 (2017).

Bogdanov, D. et al. Radical transformation pathway towards sustainable electricity via evolutionary steps. Nat. Commun. 10, 1077 (2019).

O’Shaughnessy, E., Barbose, G., Wiser, R., Forrester, S. & Darghouth, N. The impact of policies and business models on income equity in rooftop solar adoption. Nat. Energy 6, 84–91 (2021).

Milman, O. Down To earth: how gas stoves ignited an American culture war (The Guardian, 2023).

Enamorado, T., Fifield, B. & Imai, K. Using a Probabilistic Model to Assist Merging of Large-Scale Administrative Records. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 353–371 (2019).

MIT Election Data and Science Lab. Precinct-Level Returns 2020 by Individual State. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NT66Z3 (2022).

Solar Electric Programs Reported by NYSERDA: Beginning 2000, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (2024).

Acknowledgements

I thank Mircea Gherghina for his research assistance. An earlier version of the paper was presented and received valuable the 2023 Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. This study was supported by an Insight Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#430190283).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A.D. designed the research, conducted the analysis, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dokshin, F.A. Assessing potential for policy feedback from renewable energy incentive programs. npj Clim. Action 3, 83 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00164-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-024-00164-8