Abstract

Homeowner insurance is a cornerstone of modern society. It underpins broader housing markets, provides financial security for families and individuals, and is a source of resilience for communities recovering from disasters. However, climate change and urban development in hazard-prone areas are undermining this critical institution, forcing private insurers to retreat from high-risk regions and leaving homeowners in the lurch precisely when they are most in need of coverage. This perspective explores the cascading effects of this crisis and advocates for a multi-faceted set of reforms that address three interrelated problem domains—enhancing innovations in pricing and underwriting, improving transparency of data and risk assessment practices, and bolstering resilience of the built environment—to ensure sustainable protection for the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In late 2024, Hurricane Helene made landfall on Florida’s west coast as a formidable Category 4 storm, unleashing not only strong winds and deadly storm surge on beachfront areas but also swiftly penetrating inland to affect communities in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia. The hurricane’s intense rainfall led to unprecedented dam failures and landslides, particularly in the mountainous regions of North Carolina—areas not prepared to handle the impacts of tropical cyclones and/or their remnants1. The start of 2025 featured multiple major urban wildfires that left parts of southern California reeling after more than 18,000 properties in and around Los Angeles were damaged or destroyed. The footprint of damage consumed an area twice the size of Manhattan and was poised to become the costliest sequence of wildfires in U.S. history2. Yet, the aftermath of Hurricane Helene and the California wildfires underscore an even more disturbing trend affecting a growing swath of U.S. states. From the flood-prone streets of Miami to the fire-threatened homes of Malibu, a significant number of U.S. homeowners lack adequate insurance to cover property damage from such disasters.

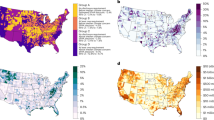

Alarmingly, while many of those affected by Helene were insured against wind hazards, a significant majority did not carry separate flood policies essential for managing water-related damages, as illustrated in Fig. 1. These flood policies, primarily provided through the federal National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), are crucial for recovery. However, NFIP coverage remains poorly understood and insufficiently purchased, leaving many homeowners unprotected3,4,5. Similarly, the California wildfires exposed even more gaps in insurance coverage. Due to persistent losses from wildfires and restrictive rate-setting rules, the largest private insurers in the state have been refusing to renew policies in California or withdrawing from the market altogether6. This has shifted the burden of protection to the state-backed California FAIR plan, as shown in Fig. 1. Initially designed as a “residual” market covering individuals unable to obtain standard home insurance, the FAIR plan is now facing liquidity challenges as subscriptions to its expensive but still under-capitalized insurance program threaten its reserve capacity7,8,9.

Public perception exists that private insurance itself contributes to some of these adverse dynamics. For instance, scholars have highlighted the industry’s short-term focus – rooted in the annual nature of most insurance contracts – as a challenge to longer-range strategic planning10,11, its development of complex forms of securitization, which require frequent reassessments of underwriting (pricing) practices12,13, and a tendency to shift financial risk towards individual property owners which may lead to an erosion of public trust in collective risk pooling that many consider a key benefit of insurance14,15. Others have pointed out that climate change is exacerbating some of these trends as insurers grapple with how to manage rising uncertainties around both hazard (e.g. frequency of extreme events, sea level rise, greater temperature extremes, etc.) and exposure (e.g. where/how people live and other socioeconomic factors)16. However, to meaningfully address these challenges and explore valid avenues for reform, it is crucial to examine the situation from the perspective of the re/insurance industry itself.

Since the mid-2010s, the U.S. market has consistently experienced more financially damaging years than profitable ones17,18. That is, insurers often find themselves paying out more in claims than they receive in premiums. This has led to premium increases of up to 50% and the reduction or withdrawal of coverage even in areas previously considered to be ‘lower risk’ such as Iowa, Arkansas, and Utah17,18. In 2023 alone, insurers reported significant losses on homeowners’ policies in 18 states—a stark rise from previous years—reflecting the industry’s strain17. While losses are linked to an increase in the frequency and severity of climate-driven disasters, they are further intensified by a net migration of Americans into hazard-prone areas like floodplains, coastal counties, and the Wildland-Urban Interface, the so-called WUI19,20,21.

Vulnerabilities of new arrivals, some of them displaced from over-priced housing markets in other parts of the country22, are often exacerbated by weak or inconsistently enforced land-use policies that might otherwise mitigate growing exposure23,24. Additionally, global interdependence means that concurrent disasters across multiple regions put more pressure on limited reinsurance capital, creating financial instability that reduces the capacity of these companies to absorb future risks25. Finally, operational challenges add extra drag to these financial strains. Disaster-induced surges in filed claims can overwhelm existing processing systems, while inflation and supply chain disruptions inflate rebuilding costs, further stretching insurers’ reserves26,27.

In response, both primary insurance carriers and reinsurers have pursued various strategies, including investing in advanced risk models often in partnership with academic institutions28, securing alternative risk capital using financial vehicles like catastrophe bonds and insurance-linked securities, and collaborating with government programs such as the NFIP or hybrid, public-private “Protection Gap Entities”25. However, the unpredictability of climate extremes, along with the fact that many of these efforts are in their early stages, is still leading insurers to exit from risky markets and leaving homeowners without coverage for their most valuable assets17,29,30.

The growing void in the homeowner’s insurance market raises crucial questions: What are the broader societal and economic consequences of insurers pulling back from high-risk areas? More critically, how should the escalating costs associated with climate change be socially distributed? This perspective explores the ripple effects of insurers retreating from hazard-prone areas and advocates for a targeted, multi-faceted set of strategies focused on enhancing risk transfer mechanisms, advancing transparency about data use and risk assessment practices, and bolstering the governance of local resilience to secure sustainable solutions for communities living on the edge of uninsurability.

Cascading effects of insurer retreat

In the U.S., the ongoing retreat of insurers from climate risk-exposed regions represents a profound shift in the financial security of homeowners, renters, and the broader economy. Driven by the increased frequency and severity of natural disasters, this exodus is creating substantial gaps in insurance coverage in places where it is needed most. The implications of this shift are extensive, affecting everything from property values and mortgage accessibility to local economies and government budgets, and necessitating a reassessment of risk management and underwriting strategies nationwide31.

Prospective homeowners in some of these areas are facing challenges in obtaining private insurance, a requirement for securing traditional mortgage loans32,33,34. Existing homeowners who manage to secure insurance may face steep premium hikes at renewal time or, worse, receive non-renewal notices32. This situation may strip people of adequate protection against potential disasters, leaving them financially exposed in the event of property damage. Instability in the insurance market can also directly affect renters. Landlords facing higher insurance costs or unable to obtain coverage pass these costs onto tenants through increased rent or choose not to invest in maintaining or improving properties, potentially leading to deteriorating living conditions. Renters experience fewer coverage options and higher costs, exacerbating their vulnerability in these markets35.

In the face of shrinking insurance options, local real estate markets are also poised to suffer with broader economic repercussions that could be profound22,33,34,36. As securing insurance becomes a greater challenge in certain parts of the country, the barrier to entering the housing market rises, deterring new buyers and cooling off real estate transactions, particularly in regions most vulnerable to climate change. This situation could lead to significant slowdown in home purchases, extended listing periods for homes and may influence overall real estate market dynamics, subtly shifting the landscape of homeownership in areas most at risk from climate change36,37. Unlike during the subprime mortgage crisis from 2007 to 2010 where property values eventually rebounded, properties that are literally underwater or otherwise uninsurable may never recover their value38. This devaluation has cascading effects on local economies, especially those heavily reliant on real estate and construction sectors. For instance, there are growing concerns about changes in retirement patterns as the cost of insurance becomes an important driver in whether seniors think they can afford to move to certain parts of the country39,40. Also, as home values drop and the properties become harder to sell, municipal tax bases are likely to shrink, resulting in decreased funding for public services, including those essential for climate adaptation measures41,42. This situation could create a vulnerability double-bind: areas most in need of adaptation investments might find themselves least able to afford them, exacerbating their exposure to risk.

The exodus of insurers from climate-related hazard-prone areas could also intensify the strain on government-sponsored programs and enterprises, such as the California FAIR plan mentioned above. These government programs serve as “insurers of last resort,” offering necessary insurance options when the private market fails to do so. However, the expansion of such state-backed insurance plans in response to the withdrawal of private insurers from high-risk markets can precipitate several significant challenges. Due to their lack of diversification and heavy reliance on state funding through taxation, these plans can lead to a heightened risk of public default32,43,44. Particularly problematic is the scenario in which taxpayers living in areas less affected by natural disasters are tasked with subsidizing the losses in high-risk regions45. This financing model can foster resentment and widen economic disparities, potentially sapping the public’s willingness to support these state-funded insurance mechanisms. Moreover, as private insurers withdraw from high-risk zones, there is a concerning trend toward the shifting of high-risk loans to government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Such a shift can accumulate climate-related risks on these public entities, inflating a climate risk bubble that poses a threat to financial stability46,47.

Therefore, growing concerns about these impacts on local real estate markets, municipal tax receipts, and the broader financial system underscore the urgent need for a reevaluation of how climate risks are governed and financed, necessitating collaborative efforts among key stakeholders to devise a more sustainable set of insurance-oriented solutions22.

A multi-faceted approach to safeguard our communities

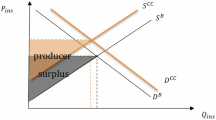

Ensuring that communities remain protected in the face of a changing climate calls for a multi-faceted approach structured around three critical problem domains: enhancing innovations in pricing and underwriting, addressing gaps in data availability and modeling capacity, and mitigating societal and infrastructural vulnerabilities by advancing resilience, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Here’s how we can forge a path forward:

Enhancing innovations in pricing and underwriting

Risk transfer lies at the heart of any insurance program, enabling policyholders to pool their exposure and compensate those who incur covered losses. However, research indicates that climate change may exacerbate the concentration of losses by intensifying extreme weather events48,49. As these losses continue to grow, one potential way to bolster reinsurance capacity beyond a certain threshold is through a federal catastrophe backstop program specifically tailored for highly climate-vulnerable areas—covering those rare tail events with excessive losses once they exceed a prescribed limit50,51. Modeled after the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA), such a program could feature industry-wide loss triggers and reinforce risk-sharing between private insurers and the federal government, all while preserving the vital role of private reinsurance51. Still, several limitations warrant careful consideration. First, frequent or predictable losses—particularly in regions repeatedly struck by disasters—could challenge the program’s financial sustainability, as backstops are most effective when events remain relatively infrequent. Second, a federally backed fund risks creating moral hazard, where policyholders or local governments may feel less urgency to invest in mitigation or relocate away from high-risk zones if they expect federal support. Third, cost allocation and funding mechanisms need to be equitable and transparent, avoiding overly burdening taxpayers. To ensure a well-informed approach, a dedicated commission of key stakeholders—including government agencies, reinsurers, and insurers—should conduct a comprehensive analysis of existing models such as TRIA and state-level residual markets. The goal should be to develop a framework that enhances, rather than replaces, the private market while providing a stronger role for the federal government in shaping local governance of vulnerability and risk mitigation measures.

Risk transfer innovations in the private sector may also help boost insurance resilience in the face of climate challenges. For instance, a mechanism called parametric insurance offers a quicker and simpler alternative to traditional indemnity forms of risk transfer. Unlike indemnity insurance, which requires a detailed assessment of actual damages incurred before any payout is made, parametric insurance automatically triggers payouts when specific, predefined weather-based parameters are met, such as reaching certain hurricane wind speeds. This approach promises faster recovery with lower premiums and can be scaled to community-based models, where local governments or nonprofits serve as risk aggregators52. An example of community-based parametric insurance is a pilot project run by the nonprofit Center for NYC Neighborhoods, where the nonprofit prioritizes which individuals in the community are most in need of aid after an event53. That said, parametric insurance has also been criticized for its reliance on simplified models and proxies, with triggers designed by third-party companies whose methods are not always easy to scrutinize54. This field deserves more research, but in the least, advancing credible parametric approaches will require effective collaboration among insurers, communities, and governments to refine risk parameters and guarantee timely payouts55.

A last component of improving risk transfer mechanisms is making sure they are based on risk-based premium pricing, leveraging granular hazard data to set premiums that more appropriately reflect a property’s actual level of risk56. This approach may discourage development in high-risk areas by highlighting the significant financial costs associated with such decisions. Governments and urban planners can use this data-driven pricing model to enforce zoning laws and promote the adoption of enhanced building codes and protective measures, ultimately reducing the impact of natural disasters23,24. However, for homeowners historically pushed into risky areas due to discriminatory housing and insurance practices such as redlining, some equity-oriented insurance assistance should be made available57. Additionally, given the uncertainties associated with using granular climate data in decision-making, further research and development are essential to better understand these uncertainties and their implications for equity and fairness in the rate-setting process.

Addressing gaps in data availability and modeling capacity

The insurance sector is often recognized as the best source of information regarding natural hazard risk, and municipalities, utilities, and other public entities are increasingly turning to the sector to assist in planning for climate impacts58. At the same time, the climate risk information accessible to homeowners and municipalities is limited, costly, and often derived from largely black box catastrophe or climate risk models, making it difficult for customers, regulators, or the public at large to assess their scientific rigor. This lack of full transparency, coupled with the high resource demands for municipalities to monitor insurance or bond ratings, highlights significant gaps in data accessibility and oversight59.

Governments must enhance climate resilience by improving the accessibility of climate risk data to homebuyers through public disclosure regulations. By ensuring data transparency, coupled with initiatives to educate homebuyers on interpreting this data, individuals can better navigate real estate purchases that may become future climate lemons59,60. However, widespread data disclosure may also disrupt property valuations. To address this, state officials should convene stakeholder platforms, what sociologists of innovation call “hybrid forums,” with the goal of gathering property owners, consumer advocates, insurers, risk modelers, regulators, and real estate professionals, to deliberate and help devise balanced public policies in consideration of diverse interests61,62,63.

Lastly, leveraging climate projections into catastrophe models, data analytics, and insurance products is also a crucial pathway for innovation in the insurance industry that will enable insurers to better understand and forecast climate-enhanced hazards. To gain the confidence of consumers, regulators, and other stakeholders, the industry should participate in defining minimum data use and traceability standards for such techniques that balance the public benefits of transparency with the profit imperatives of proprietary risk assessment companies59,64,65.

Mitigating societal and infrastructural vulnerabilities

Improved risk information must also be paired with initiatives to reduce physical vulnerability. To protect communities from the growing threats of climate change, state and municipal authorities need to step up and apply fixes at the local level that include strengthening building codes and adopting more anticipatory land-use planning. It is essential that building codes are regularly reviewed and updated to keep pace with the latest climate science and building technology66. For example, during Hurricane Ian (2022), most buildings constructed under Florida’s modern code sustained minimal or no structural damage, with an assessment of 455 homes showing no visible wind damage. In contrast, older buildings experienced 1.9 to 2.3 times more severe damage, highlighting the importance of robust, regularly updated codes66.

Moreover, encouraging homeowners to adopt individual adaptation measures may significantly mitigate risk and enhance resilience to climate-related hazards. Actions such as implementing fire-resistant materials in construction and elevating structures to protect against flood damage are vital steps in safeguarding homes. To incentivize adaptation, financial mechanisms such as tax credits, rebates, or insurance premium discounts might be effective in making the upfront investment in safer, durable infrastructure more appealing67,68,69. Data on the effectiveness of such measures is still sparse at a national level, and the proprietary nature of insurance claims currently limits the amount of empirical evidence available for analysis. Consequently, further research and real-world public-private collaboration are necessary to evaluate how these strategies can be effectively scaled and integrated into the insurance industry.

Incorporating the rising risk of climate extremes into land-use planning and directly reducing community vulnerabilities is also an important piece in solving the insurance crisis puzzle. Strategies should include limiting development in high-risk zones, assessing the protective value of surrounding landscapes (such as preventing the paving-over of water permeable grasslands as a buffer to riverine and precipitation flooding), and potentially encouraging property buyouts in increasingly uninsurable areas using federal funds70. The federal government could make municipalities’ access to disaster recovery funds contingent on pre-disaster mitigation investments that boost infrastructure resilience, reduce post-disaster costs, and align financial and housing security with the realities of climate risk71. It should be noted that many land-use planning agencies, particularly in states experiencing escalating climate risk, have had their planning authorities scaled back and are in need of renewed support to align with modern resilience objectives41,72,73.

Conclusion

The homeowner’s insurance market in the U.S. faces significant challenges from climate change and urban development, threatening millions of families around the country. It is aptly described as the “canary in the climate coal mine”74. This perspective highlights the crisis, its cascading effects, and potential strategies to mitigate these effects across three key domains: enhancing innovations in pricing and underwriting, bridging gaps in data availability and modeling capacity, and mitigating vulnerabilities in the built environment. Moving forward, the focus must shift to scaling these interventions through continued research, pilot projects, and collaborative partnerships among governments, insurers, communities, and urban planners. These efforts should aim to create adaptable, equitable, and scalable solutions that address the diverse needs of various geographic and socio-economic contexts. This work serves as a foundation for advancing discussions and fostering collaborative action to tackle the daunting challenges facing the U.S. homeowners’ insurance market.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Thiem, H. & Lindsey, R. Hurricane Helene’s extreme rainfall and catastrophic inland flooding. NOAA Climate.gov (7 November 2024).

Sorkin, A. R., Mattu, R., Warner, B., Kessler, S., J. de la Merced, M., Hirsch, L., & Weiser, B. California wildfires lay bare an insurance crisis. The New York Times (14 January 2025).

Zhang, F., Lin, N. & Kunreuther, H. Benefits of and strategies to update premium rates in the US National Flood Insurance Program under climate change. Risk Anal. 43, 1627–1640 (2023).

Kunreuther, H. Improving the national flood insurance program. Behav. Public Policy 5, 318–332 (2021).

Botzen, W. W. Economics of insurance against natural disaster risks. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Kaufmann, L. California’s insurance crisis: LA fires, payouts, and long-term impact. Bloomberg (18 February 2025).

Howard, L. S. California’s insurance crisis worsens amid wildfire risks. Insurance Journal (2025).

Flavelle, C. California’s insurance system faces crucial test as wildfire losses mount. The New York Times (14 January 2025).

Frank, T. California’s insurer of last resort is a ‘ticking time bomb’. E&E News (Politico) (2024).

Johnson, L. Catastrophic fixes: cyclical devaluation and accumulation through climate change impacts. Environ. Plan. A 47, 2503–2521 (2015).

Jarzabkowski, P. et al. Insurance for climate adaptation: opportunities and limitations. Global Commission on Adaptation, UN, Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Washington, DC, U.S. https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/28797/ (2019).

Taylor, Z. J. The real estate risk fix: residential insurance-linked securitization in the Florida metropolis. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 52, 1131–1149 (2020).

Johnson, L. Catastrophe bonds and financial risk: securing capital and rule through contingency. Geoforum 45, 30–40 (2013).

Horn, D. P. & Webel, B. Natural Disasters and the Homeowners Insurance Market. Congressional Research Service, No. IN12375. https://crsreports.congress.gov (2024).

Cevolini, A. & Esposito, E. From pool to profile: social consequences of algorithmic prediction in insurance. Big Data Soc. 7, 2053951720939228 (2020).

Lucas, C. H. & Booth, K. I. Privatizing climate adaptation: how insurance weakens solidaristic and collective disaster recovery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11, e676 (2020).

Flavelle, C. & Rojanasakul, M. As insurers around the U.S. bleed cash from climate shocks, homeowners lose. The New York Times (18 December 2024).

Cooley, P. Home insurance was once a ‘Must.’ Now more homeowners are going without. Washington Post (28 May 2024).

Katz, L. & de la Campa, E. Thousands more people are moving in than out of fire- and flood-prone America, fueled by migration to Texas and Florida. Redfin News (05 August 2024).

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The State of the Nation’s Housing 2023. Harvard Graduate School of Design, Harvard Kennedy School. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_The_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2023.pdf (2023).

Modaresi Rad, A. et al. Human and infrastructure exposure to large wildfires in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1343–1351 (2023).

Taylor, Z. & Knuth, S. The Insurance Crisis is a Housing Crisis - Climate and Community Institute (2024).

Hemmati, M., Mahmoud, H. N., Ellingwood, B. R. & Crooks, A. T. Unraveling the complexity of human behavior and urbanization on community vulnerability to floods. Sci. Rep. 11, 20085 (2021).

Hemmati, M., Mahmoud, H. N., Ellingwood, B. R. & Crooks, A. T. Shaping urbanization to achieve communities resilient to floods. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 094033 (2021).

Jarzabkowski, P., Chalkias, K., Cacciatori, E. & Bednarek, R. Disaster Insurance Reimagined: Protection in a Time of Increasing Risk (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Jarzabkowski, P., Bednarek, R., Chalkias, K. & Cacciatori, E. Enabling rapid financial response to disasters: knotting and reknotting multiple paradoxes in interorganizational systems. Acad. Manag. J. 65, 1477–1506 (2022).

Cusick, K., Canaan, M. & Sharma, N. Climate change and home insurance: US insurers have been hit hard by severe weather-related claims. Deloitte Insights https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/financial-services/financial-services-industry-predictions/2024/climate-change-home-insurance-resiliency.html (2024).

Gallagher Research Center. Global risk of tropical cyclones. Gallagher Re. https://www.ajg.com/gallagherre/news-and-insights/global-risk-of-tropical-cyclones/ (2024).

Schwarcz, S. L. Insuring the ‘uninsurable’: catastrophe bonds, pandemics, and risk securitization. Wash. U. L. Rev. 99, 853 (2021).

Bittle, J. The problem keeping insurance execs up at night? ‘Kitty-Cats.’ Grist (2024).

Senate Budget Committee. Next to Fall: The Climate-driven Insurance Crisis is Here and Getting Worse. https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/next_to_fall_the_climate-driven_insurance_crisis_is_here__and_getting_worse.pdf (2024).

Nevitt, M. & Pappas, M. Climate risk, insurance retreat, and state response. Ga. Law Rev. 58, 1603 (2023).

Keys, B. J. & Mulder, P. Property Insurance and Disaster Risk: New Evidence from Mortgage Escrow Data (No. w32579) (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024).

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The State of the Nation’s Housing 2024. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_The_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2024.pdf (Harvard University, 2024).

Potter, C. & Godshall, L. Renting at the edge of the world: climate change protections failing renters. Wash. Univ. J. Law Policy 74, 117 (2024).

Kim, K. & Lin, X. Climate Risks in the Commercial Mortgage Portfolios of Life Insurers: A Focus on Sea Level Rise and Flood Risks. NAIC CIPR Research Fellows Program Report (2023).

Clayton, J., Devaney, S., Sayce, S. & Van de Wetering, J. Climate risk and real estate prices: what do we know? J. Portf. Manag. 47, 75–90 (2021).

Keenan, J. M. & Bradt, J. T. Underwater writing: from theory to empiricism in regional mortgage markets in the U.S. Clim. Change 162, 2043–2067 (2020).

White, M. Extreme weather and rising insurance rates squeeze retirees. The New York Times (04 February 2022).

Rissman, P. Climate change is a financial threat to your retirement. Rights CoLab https://rightscolab.org/climate-change-is-a-financial-threat-to-your-retirement/ (2024).

Shi, L. & Varuzzo, A. M. Surging seas, rising fiscal stress: exploring municipal fiscal vulnerability to climate change. Cities 100, 102658 (2020).

Gray, I. The treadmill of protection: how public finance constrains climate adaptation. Anthropocene Rev. 8, 196–218 (2021).

Born, P., Cole, C. & Nyce, C. Citizens and the Florida residential property market: how to return to an insurer of last resort. J. Insur. Regul. https://doi.org/10.52227/25056.2021 (2021).

Ubert, E. Investigating the difference in policy responses to the 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons and homeowner insurance crises in Florida and Louisiana. Socio-Econ. Rev. 15, 691–715 (2017).

Kousky, C. & Medders, L. The evolution of Florida’s public-private approach to property insurance. Florida Policy Project. Retrieved from https://floridapolicyproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FINAL_Florida-Insurance-Market-Report.pdf (2024).

Ouazad, A. & Kahn, M. E. Mortgage Finance and Climate Change: Securitization Dynamics in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters. National Bureau for Economic Research Working Paper 26322 (2019).

Sastry, P., Sen, I. & Tenekedjieva, A. M. When insurers exit: climate losses, fragile insurers, and mortgage markets. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4674279 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4674279 (2023).

Newman, R. & Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 6103 (2023).

Fraser-Baxter, S. When risks become reality: extreme weather in 2024– World Weather Attribution (2024).

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Climate Change and Insurance. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-08/59918-Climate-Change-Insurance.pdf (2024).

Ceres. Ceres 10-point Plan for the Insurance Industry. https://www.ceres.org/resources/reports/ceres-10-point-plan-for-the-insurance-industry (2024).

Kousky, C., Wiley, H. & Shabman, L. Can parametric microinsurance improve financial resilience of low-income households in the United States? A proof-of-concept examination. Econ. Disaster Clim. Change 5, 301–327 (2021).

NYC Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. Press Release: MOCEJ and CNYCN Launch Innovative Pilot to Address Flooding (2023).

Johnson, L. Rescaling index insurance for climate and development in Africa. Econ. Soc. 50, 248–274 (2021).

Aguiton, S. A. A market infrastructure for environmental intangibles: the materiality and challenges of index insurance for agriculture in Senegal. J. Cult. Econ. 14, 580–595 (2021).

de Ruig, L. T. et al. How the USA can benefit from risk-based premiums combined with flood protection. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 995–998 (2022).

Elliott, R. Insurance and the temporality of climate ethics: accounting for climate change in U.S. flood insurance. Econ. Soc. 50, 173–195 (2021).

Collier, S. J. & Cox, S. Governing urban resilience: insurance and the problematization of climate change. Econ. Soc. 50, 275–296 (2021).

Condon, M. Climate services: the business of physical risk. Ariz. St. L. J. 55, 147 (2023).

Hino, M. & Burke, M. The effect of information about climate risk on property values. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2003374118 (2021).

Callon, M., Lascoumes, P. & Barthe, Y. Acting in an Uncertain World: An Essay on Technical Democracy (MIT Press, 2011).

Gray, I. Hazardous simulations: pricing climate risk in U.S. coastal insurance markets. Econ. Soc. 50, 196–223 (2021).

Jasanoff, S. Uncertainty (MIT Press, 2022).

Chegwidden, O. & Frank, S. What metadata are necessary for interpreting a climate risk assessment? Carbon Plan https://carbonplan.org/blog/climate-risk-metadata (2023).

Mankin, J. S. The people have a right to climate data. The New York Times (20 January 2024).

Giammanco, I. M., Newby, E., Pogorzelski, W. H. & Shabanian, M. Observations of Building Performance in Southwest Florida during Hurricane Ian (2022): Part II: Performance of the Modern Florida Building Code. IBHS Research Executive Summary (Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, 2023).

Kunreuther, H., Michel-Kerjan, E. & Tonn, G. Insurance, Economic Incentives and Other Policy Tools for Strengthening Critical Infrastructure Resilience: 20 Proposals for Action (The Wharton School–University of Pennsylvania, 2016).

Mol, J. M., Botzen, W. W. & Blasch, J. E. Risk reduction in compulsory disaster insurance: experimental evidence on moral hazard and financial incentives. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 84, 101500 (2020).

Javeline, D., Kijewski-Correa, T. & Chesler, A. Do perverse insurance incentives encourage coastal vulnerability? Nat. Hazards Rev. 23, 04021057 (2022).

Siders, A., Hino, M. & Mach, K. The case for strategic and managed climate retreat. Science 365, 761–763 (2019).

The White House. Executive Order on Climate-Related Financial Risk. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/05/20/executive-order-on-climate-related-financial-risk/ (2021).

VanderMeer, J. The annihilation of Florida: an overlooked national tragedy. Current Affairs (18 May 2022).

Patterson, T. How Houston’s layout may have made its flooding worse. CNN (28 August 2017).

Keyes, B. Your homeowners’ insurance bill is the canary in the climate coal mine. The New York Times (07 May 2023).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Brian Kerschner from Gallagher Re for his support in creating the graphics. We also appreciate Professor Adam Sobel from Columbia University and Desmond Carroll from Gallagher Re for their valuable feedback and insights. Lastly, we are grateful to the reviewers and editors for their thoughtful comments, which have helped enhance this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., I.G., and S.B. conceived and developed the idea for this article. M.H. and I.G. wrote the initial draft of the paper. M.H., I.G., and S.B. edited the manuscript and wrote the subsequent and final drafts. M.H. and I.G. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This perspective reflects the independent and shared views of its co-authors. As noted in the author affiliations, M.H. and S.B. are employed by Gallagher Re, a reinsurance brokerage firm. While we do not identify any conflicts of interest in the solutions proposed, in the interest of full transparency, we reaffirm these affiliations for the reader’s awareness.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hemmati, M., Gray, I.P. & Bowen, S.G. The growing void in the U.S. homeowners insurance market: who should bear the rising cost of climate change?. npj Clim. Action 4, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00231-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00231-8

This article is cited by

-

Physical climate risk creates challenges and opportunities in US municipal finance

Nature Cities (2026)