Abstract

As the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, China would make important contributions to the achievement of the Paris goals if it made economy-wide, strong policy interventions to combat climate change. Despite a growing number of studies on China’s climate governance, the overall landscape of China’s climate policy and its key characteristics remain underexamined. To address this knowledge gap, we developed a dataset of 358 climate-related policies adopted by China’s central government in 2016–2022 and assessed key policy mix characteristics including policy density, balance and intensity. Our findings reveal that higher policy density does not equate to stronger action. Significant variation also exists in alignment with China’s Nationally Determined Contributions, especially in high-emitting sectors. Moreover, despite a relatively balanced mix of regulatory, economic, and informational instruments, this balance does not guarantee intensity. Our study shows challenges in China’s policy coherence and calls for stronger mechanisms to integrate national goals into sectoral policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Paris Agreement established in 2015 sets the goal to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 °C, but its implementation relies on Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by individual countries, serving both as commitments and as the main mechanism for discerning a country’s level of climate ambition1,2. A critical condition for the Paris Agreement’s success is thus the support of major emitters, who need to make ambitious targets and effectively implement them3,4. As the world’s largest emitter, the policies chosen and actions taken by China will have significant implications for the global net zero transition. Given China’s political context, public policy interventions are likely to play a key role in the country’s climate action5,6. While there is a burgeoning literature on climate governance in China and policies needed for the country’s decarbonization7,8,9,10,11,12, we still lack an understanding of the overall landscape of China’s climate policy and key designed features of existing policies. This gap hinders our ability to investigate how China operationalizes its climate ambition through national-level policy arrangements.

To bridge this gap, we situate our study in the broader debate on climate policy ambition to assess policy mixes of China’s national climate policy12,13. Compared to the existing research, it seeks to make two contributions. First, unlike previous work modeling the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of a small number of policies, often within specific sectors14,15,16,17,18,19,20, we provide a comprehensive view of policies across all sectors and issue areas and assess their interconnections. This holistic approach enables us to investigate the dynamism in policymaking—including policy durability and change—which is crucial given the Paris Agreement’s reliance on a ratchet-up mechanism to increase ambition over time. Second, previous studies have paid insufficient attention to the detailed design features of individual policies, including distinct instrument types employed and their alignment with the country’s NDCs. We argue that climate policy ambition can be effectively captured through the combined assessment of policy density, policy mix balance, and policy intensity. Policy density reveals the extent of policy activities1; policy mix balance highlights the diversity of instruments being employed21, and policy intensity reflects the depth and strength of individual policies. Focusing on only one aspect—such as strong policy objectives or diverse instruments—is insufficient to guarantee the high ambition of policies in a given field. Together, these indicators uncover the key policy design features that shape policy effectiveness and, therefore, can shed light on how countries operationalize their climate commitment and goals.

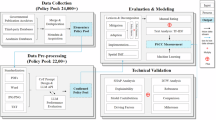

In conducting our analysis, we built a dataset containing all types of policy documents issued by different national government agencies in China to tackle climate change since the adoption of the Paris Agreement (N = 358). In our study, we define ‘policy’ as an official document that outlines objectives, strategies or actions related to climate change. Accordingly, from a legal perspective, a policy can serve various functions ranging from laws and regulations to plans and guidance. For each individual document, we identified specific instruments, which are the key components of that policy and the measures employed to achieve its stated objectives. Our analysis draws on theories of policy mix to examine three key characteristics of China’s climate policy mixes: policy density (the number of policy documents), policy mix balance (the variety and distribution of policy instruments within those policy documents), and policy intensity (the strength of individual policy)21,22. We also investigated sectoral and temporal variations in China’s climate policy mix to identify existing patterns and potential gaps.

Four findings are worth noting. First, there is a disconnect between policy density and intensity. We find that a high number of policies does not necessarily translate to high policy intensity and strong actions. This is evident in sectors like energy, electricity and heating, which, despite being the largest emitters and having numerous policies, only have moderate policy intensity scores. This disconnect indicates that policy proliferation without policy strength may not effectively advance climate actions. Conversely, sectors like agriculture and land-use change and forestry (LULUCF), demonstrate high policy intensity with fewer policies, suggesting these sectors may be underrepresented, they are implementing stronger actions and policies. Second, the study highlights that a balanced policy instrument mix does not guarantee policy ambition. While China’s climate policies exhibit a relatively balanced distribution of instruments—with regulatory tools being the most common and economic (e.g., green finance and incentives) and informational instruments (e.g., education and outreach) also playing significant roles—the mere presence of a balanced mix is insufficient. Third, there is significant variation in sectoral alignment with China’s NDCs. High-emitting sectors such as transportation and buildings exhibit relatively low policy intensity and limited contributions from the “objectives” and “scope” elements—this result means that policies in these sectors do not align well with China’s NDC targets (“objectives”) and cover a relatively small number of actors and actions (“scope”), and therefore raise concerns about their capacity to achieve their decarbonization targets (see Methods for the definitions of different intensity elements). Fourth, challenges remain in policy coherence and integration, particularly regarding the alignment between individual sectoral policies and national climate goals. The limited contribution from the “objectives” element across many policies highlights a misalignment between national goals and sectoral actions. This misalignment raises concerns about the mechanisms through which national climate objectives are integrated into specific policies. The observed gaps could hinder the achievement of China’s ambitious climate targets, suggesting a need for stronger institutional mechanisms to ensure horizontal (across sectors) policy coherence.

In the public policy literature, the term ‘policy mix’ denotes instances where policymakers employ bundles of instruments with the expectation of achieving policy goals more efficiently and effectively than using a single instrument8,21,22,23,24,25. The rationale for focusing on policy mix is that no single instrument can address all of the identified failures and bottlenecks, and numerous policy interventions are required to induce and accelerate fundamental transitions, which interact with each other in policy mixes21. The combination of policy instruments and their interplay constitutes a multi-level and nested phenomenon, where the design and selection of instruments represent constrained efforts to align goals and expectations across all policy elements23. This feature of policy mix serves as a vital reference point for assessing collective effectiveness across different policy levels.

The nature of a policy mix can be described by several characteristics, which can influence policy performance24. To empirically evaluate policy mixes, we focus on three characteristics suggested by Schmidt and Sewerin21 and Schaffrin et al. 25, policy density, policy mix balance and policy intensity as shown in Fig. 1. Together they can show the range of problems being targeted, the instruments being used and also the likelihood of a given policy being effective.

First, policy density accounts for the number of policies within a specific field of attention and the policy activities to which the government attaches1,21,26,27. Second, Schmidt and Sewerin21 introduce the concept of policy mix balance, which evaluates the dispersion of policy instrument types within a policy mix. A balanced combination of different instruments is viewed as conducive to social-technical transitions, as the diverse choice of instruments is more likely to address wider scope and relevant actors. Third, policy intensity, as defined by Schaffrin, Sewerin, and Seubert25, refers to the “strictness” of policies by considering key design features including the level of involvement, scope of governmental intervention, and allocated resources. Our operationalization of this concept draws on Schaffrin et al.25 by assessing six features—objectives, scope, integration, budget, implementation, and monitoring efforts, with the assumption that policies with higher scores of intensity are more likely to achieve their goals.

According to the existing literature on China’s climate governance, we expect a few trends in the three characteristics of policy mixes under investigation. To begin with, China’s climate governance should be understood within the context of the country’s overall governance structure28. China’s climate policymaking often uses a ‘target responsibility system’ by allocating specific targets by the central government to various levels of local governments and state-owned enterprises. This system is characterized by a clear upward accountability: the main objective of the lower level of government is to fulfill the tasks assigned by the higher level12,29. Given this hierarchical and centralized structure, focusing on national-level policies provides a crucial first step in understanding how China’s climate efforts are shaped from international commitments to domestic actions.

While subnational governments play an important role in disseminating, interpreting, and implementing climate policies, their actions are largely guided by national directives. They are key points for utilizing resources and ensuring policy enforcement within their jurisdictions. In other words, the central government sets overarching climate goals and policies, and provincial and local governments are responsible for tailoring and executing these policies according to local contexts30,31,32. In this system, the Five-Year Plan (FYP) serves as an anchor in coordinating and aligning various policy initiatives across different sectors and levels of government. It provides a comprehensive framework for integrating and prioritizing policies related to economic development, environmental protection, social welfare, and other key areas33.

The formulation of the FYP involves extensive internal coordination among ministries and relevant bodies before its official release. Specifically, on climate-related issues and targets, different ministries submit early drafts and proposals to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which coordinates the integration of these inputs into the overarching plan7,12. This collaborative process lays the groundwork for sector-specific policies, including all initiatives related to climate actions, well before the FYP’s formal announcement. As a result, when the FYP is officially released in March12, these policies can be swiftly formalized and implemented. Therefore, we expect the number of climate policies in China to be higher during the year when the FYP is issued.

Considering potential sectoral variation, the energy sector is the largest contributor to China’s carbon emissions and holds huge potential for emissions reduction. Within the energy sector, studies also highlight electricity generation as the largest direct source of carbon emissions in China and the huge potential of stimulating clean power on the supply side16,34. Hence, we expect that energy, electricity and heating is the sector having the highest policy density. Meanwhile, given the significance attached to energy transition by Beijing in China’s climate policy35,36, we also expect this sector to demonstrate higher policy intensity compared to other sectors in China’s climate policy mixes.

On policy instruments chosen by the Chinese government, existing literature underscores China’s authoritarian governance, characterized by a top-down, command-and-control policymaking style6,37,38. However, recent studies on China have also found a strategic blend of hierarchical and market-based instruments, orchestrated through centralized planning, in specific sectors and regions8,11,39,40,41. Given these accounts, it is necessary to empirically assess the dominant types of instruments in China’s climate policy mix in the post-Paris era. On market-based and economic instruments, recent research has suggested China’s growing effort to build emissions trading schemes (ETS)9,33,40,42. These tools are seen as not only beneficial for emissions reduction but also for unlocking economic growth opportunities33. In this respect, a plausible expectation is that as China’s climate governance framework matures, the use of tradable permits like ETS will increase.

We take an exploratory approach to unpack the overall landscape of China’s climate policies in the post-Paris era, rather than strictly testing pre-defined hypotheses. To investigate China’s climate policy mixes, we built a database of the climate policies adopted by the national government from 2016 to 2022. As the first mapping of China’s climate mixes, we chose to focus on national-level policies given that policies made at the center sets the stage for provincial and local actions due to China’s authoritarian governance structure30. Our dataset includes all policies relevant to climate mitigation and adaptation actions that are listed in China’s NDC.

The data collection strategy involved integrating data from multiple open and trustworthy sources43,44 with thorough documentation to ensure comprehensive coverage and accuracy. Policies were cross-checked and manually verified by two authors to guarantee relevance and inclusion (see details in the Methods section). In total, we identified 358 policies that are “in force” till the time we conduct our assessment (September 2023) in 11 sectors over a seven-year period (see details in Supplementary Note 3). Within these 358 policies, 292 policies are mitigation policies, 9 policies are adaptation policies, and 53 policies address both mitigation and adaptation aspects.

To measure policy density, we count the number of policy documents published each year across different sectors. For example, the policy density of the building sector in 2020 is the number of policy documents classified as building-sector policies published in that year.

For policy mix balance, we first identify different types of instruments within each policy document, following the nine-instrument framework proposed by Schmidt and Sewerin21. Policy mix balance is then calculated using the 1-Simpson Index45 for each year and sector. In this index, the highest value is 1, which indicates a perfectly balanced mix of different instrument types and the lower the score is, the less balanced the relevant policy mix is (i.e., the instruments are more concentrated into specific types) (see details in the “Methods” and Supplementary Note 1).

To analyze policy instrument adoption trends, we also group instruments into a second typology, where economic-related instruments are combined into the “Economic Instruments” category and “education and outreach” is merged with “research, development, and deployment (RD&D)” into the “Information and Education” category. This dual approach allows us to track policy instrument adoption over time in a comparative manner while maintaining a detailed balance calculation as well as detailed information on the important individual economic instruments (e.g., green finance and tradable permits).

We employ the Index of Policy Activity (IPA) framework22 to assess policy intensity at the individual policy level. The IPA evaluates six key elements (integration, scope, objectives, budget, implementation, and monitoring) using pre-defined scoring systems. A higher score for each element indicates a stronger focus on that aspect within the policy. These scores are combined to yield an overall intensity score for each policy.

We made several key adjustments to adapt the IPA to our study and accommodate to China’s unique climate policy landscape. First, to ensure the IPA framework captures both mitigation and adaptation actions, we expanded the “scope” element to include specific climate actions outlined in China’s NDCs, where both aspects are explicitly addressed. This adaptation also allowed us to cover policies across multiple sectors, as the NDCs reference climate actions from various sectors, ensuring sectoral expansion beyond the original IPA’s focus on the energy sector. Additionally, this expansion enabled us to measure each individual policy’s climate action coverage – the breadth with respect to the NDCs. Second, we refined the “objective” elements by translating abstract policy objectives into more measurable descriptions, ensuring their alignment with the broader targets in China’s NDCs. This adjustment allowed the IPA framework to better measure how closely individual policy objectives correspond to the country’s overall NDC goals. These adaptations ensure that our revised framework can effectively assess the intensity of China’s whole national climate policy mix across all sectors, cover both mitigation and adaptation efforts, and measure the alignment with the NDC goals (see details in the Methods and Supplementary Note 2).

Results

Policy density over time and across sectors

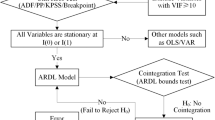

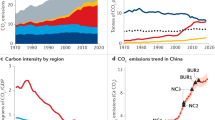

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal patterns in the density of the policies over time and across sectors in our dataset. 2021 is by far the peak in policy density, with 101 climate policies adopted by Beijing. Subsequently, 2022 follows closely with 79 policies, while 2016 also exhibits a substantial policy output with 51 measures. Other years exhibit varying degrees of density, ranging from 41 policies in 2020 to 18 policies in 2018. This result suggests that more policies were issued immediately after the central government publishes the overall FYP (China’s FYPs are usually published in October), with peak densities occurring in the years following the introduction of new FYPs, as observed in 2016 and 2021. This aligns with our expectation of the potential impact of the FYP as the foremost strategic policy framework on policymaking in China from a top-down perspective. By contrast, 2018 recorded the fewest policies (18), possibly due to the ministry‐level reorganization in that year, when some policy design responsibilities on climate change were shifted from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) to the newly formed Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). This transition may have briefly reduced institutional capacity to issue new policies, but future research studying a longer time period is needed to assess whether the low density in 2018 is truly caused by the government’s administrative restricting or simply due to the downturn in the middle of China’s five-year plan cycle.

When analyzing policy density across sectors, the energy, electricity, and heating sector notably stands out with 97 policies (27%), indicating that high priority has been given by Beijing to address climate change. Additionally, among the 358 climate policies studied, 27% (N = 95) address issues across various sectors, known as “cross-cutting area” policies. This trend suggests the Chinese government’s recognition of climate change as a policy problem across different sectors. The transportation sector ranks third with 49 policies, followed by industry (35), land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) (22), waste (16), and a few other sectors. It is worth noting that the agricultural sector, despite its significant contribution to GHG emissions, has a relatively small number of policies, with no policy issued between 2016 and 2020.

Policy mix balance and the changing popularity of different instrument types

Our analysis of the policy mix balance utilized the nine typologies of instruments. We find a consistent and high level of balance (0.8–0.9) observed in the distribution of policy instruments across all seven years (Fig. 2). This balance score, similar to that observed in OECD countries, suggests a diversified approach in China’s climate policy mix at the national level21. Notably, the high balance score persisted even when comparing years with a high or low number of policy documents. This suggests that the high balance level is robust and independent of policy density. A further breakdown by sectors shows similar results (Fig. 5), with all sectors achieving a high balance (median = 0.86), and the commercial and residential sectors displaying the highest (0.89) and the public sector the lowest (0.81). Overall, China’s national climate policies since 2016 demonstrate a well-balanced mix of instruments across sectors. This diversity of policy tools chosen by the Chinese government suggests a comprehensive approach to addressing climate change, which contradicts with the conventional wisdom that China’s authoritarian government prefers top-down regulations to promote climate action.

To gain further insights into the composition of this policy mix, we adopted a second, broader of five instrument types. This simplified typology groups the original nine types into broader categories to facilitate comparison and to track the prevalence of policy instruments—the proportion of policy documents that incorporate a specific type of policy instrument—across the dataset more effectively. Figure 3 presents the results of instrument prevalence from 2016 to 2022 and over 11 sectors. Regulatory instruments were the most common throughout all years and sectors, with a relative rate of 87.89%. This means that 87.89% of policy documents adopt regulatory instruments for governing climate change. That said, we observed a slight declining trend in their use, from 90.02% in 2016 to 88.61% in 2022 (see Fig. 3a).

For the second most prevalent instrument type, economic instruments were utilized in 73.10% of all policy documents through various mechanisms such as green finance and incentives, tax, and tradable permits. The trend in the adoption of economic instruments was not clearly increasing. Given their importance and potential, we examined the distribution of different subtypes of instruments in this category more closely. We observed an increasing trend in the use of tax instruments, while the adoption of tradable permits remained steady, with approximately 18.54% of policies incorporating this instrument throughout the studied years. Contrary to our prediction, we did not find an increasing trend in the adoption of tradable permits. Notably, peaks occurred in 2016 and 2021—both significant years possibly due to the submission of China’s first NDCs and their updates. Additionally, China’s official launch of its national carbon emission trading scheme in 2021 may also explain the peak in that year. Approximately 66.74% of climate policies employed information and education instruments, and we observed a growing trend in the adoption of this type of instrument.

Instrument prevalence also varied across sectors (see Fig. 3b). Regulatory instruments remained the most common type in most sectors, with an average prevalence of 91.91%, except in agriculture and commercial and residential. In these two sectors, information and education instruments were identified in 100% of policies, indicating a strong preference for this type of instrument. Conversely, voluntary agreements were consistently less popular across all sectors; on average, only 25.67% of policies adopted voluntary-based instruments.

Policy intensity and its drivers

We employed a content-based coding procedure to analyze each policy document and assess its intensity. This analysis reveals how policymakers prioritize and allocate resources across different areas of the policy. Our examination of temporal trends in policy intensity reveals a dynamic picture as shown in Fig. 4. While 2016 recorded the highest intensity score (3.06 out of 6), the following years saw a decline, reaching a low point of 2.28 in 2018. Interestingly, intensity scores have shown a gradual rise since 2019, reaching 2.67 in 2021. However, it is worth noting that peak intensity did not coincide with the issuance year of FYPs. Overall, the trend suggests a potential decline in average intensity from 2016 to 2022.

Figure 4 provides a breakdown of the overall intensity scores and the contributions from the six elements of our revised IPA framework. A key finding is the prominence of integration within China’s climate policies. Across all years, the integration element remained as the most influential factor among others, with average scores ranging from 0.92 to 0.6. This highlights the interconnectedness within China’s national climate policies, where policies often connect to existing frameworks, serve as frameworks themselves, or are published to implement prior climate policies.

Moreover, high average scores for implementation (0.6) and monitoring (0.5) elements indicate a strong emphasis on practical execution and continuous oversight. This reflects the central government’s focus on effective policy enforcement and evaluation. Specifically, the attention given to implementation suggests stringency in institutional settings during the policy realization stage, while the strong monitoring score indicates established procedures and entities tasked with evaluating ongoing policy effectiveness. This dual focus on execution and oversight reflects a strategic approach taken by the central government to ensure that policies can be enforced and adaptable over time.

In contrast to these strengths, the objective element, reflecting alignment with China’s NDC goals, presents a more nuanced picture. The average score was 0.26 between 2016 and 2022, with the highest score (0.43) recorded in 2016 and the lowest (0.13) in 2020. While this element holds significant weight in our framework by reflecting alignment with the national NDCs, its overall contribution is relatively modest, considering its full score is 1. Similarly, the low budget score (0.15) raises concerns about how the implementation of these policies will be financed, as many policies appear to lack explicit budgetary allocations. This could ultimately limit the long-term effectiveness of these policies.

Additionally, lower average scores for scope (0.36) suggest a weaker emphasis on both the breadth and clarity of target groups and climate actions. The limited scope defined in many policies indicates that these policies may not comprehensively cover all relevant actors and climate actions necessary to achieve the stated goals. Furthermore, even within the areas covered, policies may lack specificity, leaving ambiguity about who is responsible for implementation and what specific actions are required. This combination of limited coverage and high ambiguity could hinder effective implementation by creating uncertainty about responsibilities and by failing to mobilize some important stakeholders. Addressing both the breadth and clarity of policy scope is essential for enhancing policy effectiveness.

Overall, China’s climate policy intensity presents a mixed picture. While strong emphasis on integration, monitoring, and implementation is encouraging, shortcomings in objective, scope, and budget need to be addressed to ensure policies are well-aligned, clearly targeted, and financially viable.

We further investigated sectoral variations in policy intensity (median = 2.6). As shown in Fig. 5, LULUCF (3.31) and agriculture (3.22) emerged as the sectors with the highest average intensity scores, exceeding the midpoint of 3. The cross-cutting areas (2.81) and waste sector (2.78) also displayed relatively high intensity. A critical finding is the disparity between emission levels and policy intensity in some key sectors. Notably, the energy, electricity, and heating sector, despite being the largest emitter, only achieved a moderate intensity score (2.61) and transportation (2.15) and buildings (2.11) also exhibited relatively low-intensity scores.

To better understand the observed sectoral variations, we analyzed the contributions of individual elements to overall intensity (see Fig. 6). We pay special attention to the objective and scope elements because in our adapted IPA framework these two elements are closely related to alignment with China’s NDCs.

Our results indicate that three sectors—energy, electricity, and heating; industry; and transportation—share a common pattern, with integration, implementation, and monitoring being the primary drivers of their intensity scores, while the contributions from the objective and scope elements are limited. This suggests that policies in these sectors may not fully align with the objectives outlined in China’s NDCs and may have a narrow coverage of climate actions and targeted actors.

Several other sectors also show limited contributions from the objective and scope elements. In particular, the transportation, commercial and residential, and waste sectors have among the lowest average scores in these elements. This raises concerns about the extent to which policies in these sectors reflect and incorporate the country’s NDC objectives and their capacity to achieve the stated decarbonization targets. The public sector, transportation, and industry also show low contributions from the scope element, which may indicate a rather narrow coverage of climate actions and targeted actors in policy design within these sectors.

In contrast, the LULUCF sector shows a significant role of the objectives element (see Fig. 6c), indicating its close alignment with the country’s NDCs. The cross-cutting areas exhibit a substantial contribution from the scope element(see Fig. 6b), reflecting a comprehensive approach that addresses both the supply and demand sides of related climate actions and target multiple actors. This is a governance holistic approach emphasizing policy interconnectedness. Therefore, to raise ambition in China’s climate policy and generate more effective climate action, a useful strategy is to increase policy intensity in terms of objective and scope elements in high-emitting sectors.

The analysis also reveals some noteworthy gaps in specific sectors. For instance, the building sector has no budget allocated across all studied years (see Fig. 6d), indicating a lack of financial consideration and arrangement in this specific area. In addition, the waste sector demonstrated limited integration of Chinese NDCs in their objective settings, highlighting a potential disconnect between waste policies and China’s broader climate goals. These observations underscore the need for targeted improvements and considerations in specific sectors to enhance the overall effectiveness of China’s climate policies.

Discussion

Investigating countries’ policy outputs to combat climate change can provide valuable empirical evidence of state-led climate action across time and issue areas. In this study, we collected and analyzed all 358 national climate policies published from 2016 to 2022 in the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter—China. Our analysis focuses on key design features of China’s national climate policy mix, which include density (number of policies), balance (distribution of instruments), and intensity (overall stringency). To our knowledge, this is the first systematic analysis of China’s policy mixes in the post-Paris Agreement era.

An innovative aspect of our study is to examine the alignment between individual climate policies and China’s NDCs, which contributes to the broader debate in the literature of climate policy and politics on the gap between ambition and action. In doing so, we introduced a revised policy intensity framework, that builds on the existing IPA, but captures the nuances of an individual country’s climate policy landscape. Specifically, we benchmark the elements of “scope” and “objective” in the policy intensity measure against the country’s NDCs to assess the extent to which individual policies align with the country’s ambition indicated in its NDCs in terms of both breadth and stringency.

Our analysis reveals several critical insights. First, while the number of climate policies—referred to as policy density—offers valuable insights into governmental focus on climate-related issues19, our findings indicate that a high number of policies does not necessarily equate to increased policy intensity. In the context of China, a growing number of policy outputs are likely to signal increased government focus on specific climate-related issues, but the relevant actions may not be ambitious enough. For instance, the energy, electricity, and heating sector, despite being the largest emitter and receiving significant policy attention (high policy density), only achieved a moderate policy intensity score. This disconnect underscores that policy proliferation without corresponding policy strength may not effectively advance climate goals46. This finding thus raises a broader theoretical question about the relationship between policy proliferation and policy impact, and more research is needed to assess whether or not more policies will lead to fragmentation, overlap, or confusion among implementing agencies and stakeholders.

Next, our findings suggest that while policies may be thematically aligned with national climate commitments, the depth of this alignment varies across sectors. High-emitting sectors like transportation and buildings exhibit relatively low policy intensity and limited contributions from the objective and scope elements. This raises concerns about the extent to which policies in these sectors reflect and incorporate NDC objectives and their capacity to achieve the stated decarbonization targets. The lack of clear objectives and comprehensive scope in these sectors is likely to hinder the effectiveness of policy implementation, indicating a need for more targeted and ambitious policy design. In contrast, sectors such as agriculture and the LULUCF demonstrate high policy intensity with fewer policies. This pattern suggests that these sectors, though possibly underrepresented in China’s climate policy discussions, are implementing stronger policies that align closely with the country’s NDC goals. In particular, the substantial contribution of the objective element in these sectors indicates a deliberate alignment with national commitments, offering a model for other sectors to emulate. Our findings on policy intensity also raise an interesting question on the relationship between policy processes and policy intensity. While some literature may expect the intensity of policies in the same area would increase over time due to potential feedback effects or path dependency47,48, our study does not show a clear trend of entrenchment. In other words, there is no guarantee that the intensity of a series of policies made after a new strategy plan or roadmap will grow. Future research is thus needed to investigate the conditions under which policy density can have positive feedback on policy intensity.

Additionally, our analysis of policy instruments reveals a relatively balanced distribution in China’s climate policy mix, with regulatory tools being the most common but economic instruments (e.g., green finance, tax, and tradable permits) and information and education instruments (e.g., research, development and demonstration) also play significant roles. This blend of different instruments reflects a combination of authoritarian and liberal features in China’s climate governance—a trend that had already started before the Paris Agreement as noted by previous studies8,29. In other words, Beijing is now apt to choose different types of instruments in pursue its climate goals instead of mainly relying on top-down regulations. Our result therefore adds more nuances to the debate on China’s authoritarian or coercive environmentalism6,37,49.

On this finding, an important caveat is that the mere presence of a balanced instrument mix does not guarantee strong policy action. For example, sectors like buildings exhibit a high balance score but low policy intensity and limited alignment with NDCs. This suggests that a balanced policy mix—where various types of instruments are diversely represented—does not necessarily lead to strict policies. In fact, the policy mix balance indicator captures the diversity of instruments but does not account for their approaches to achieving policy goals. Determining whether a balanced policy mix is inherently good remains challenging. Further research should explore the link between specific instrument combinations and policy outcomes and stringency to identify the ideal balance of instruments in different contexts and sectors, to advance our understanding of effective climate policy mix.

Lastly, our finding on the limited contribution from the objective element (which measures each policy’s alignment with China’s NDCs) in the policy intensity score highlights a potential misalignment in China between national goals and sectoral policies. This result echoes some previous studies on China’s policy the pre-Paris era, which find that China’s climate targets often remain “soft constraints,” overshadowed by more binding environmental objectives12. This misalignment raises important questions on policy coherence and suitable mechanisms to integrate national goals into sectoral policies50. While existing theories on policy integration emphasize the importance of coherent policy frameworks that align objectives across different levels of governance, our empirical evidence does not suggest this trend. As a result, the observed gaps may hinder China’s achievement of its climate goals pledged to international community, and for this reason, stronger institutional mechanisms seem needed to ensure horizontal policy coherence.

Based on our findings, we can make several policy recommendations to strengthen climate action in China. Overall the Chinese government should prioritize improving policy coherence and strengthening the alignment of sectoral objectives with the country’s NDCs. In other words, policymakers should focus not only on the quantity of policies but also on their quality and strategic alignment. More specifically, enhancing clarity and comprehensiveness in policy objectives and scope can help ensure that policies are targeted, actionable, and aligned with national goals. This includes clearly defining target groups, responsibilities, and specific climate actions required. Meanwhile, while maintaining a balanced mix of policy instruments is important, greater emphasis should be placed on selecting and tailoring instruments that are effective for specific sectors and goals. This may involve increasing the use of market-based instruments in sectors where they are underutilized or enhancing regulatory measures where rapid change is needed. Finally, enhancing the budget element in policy intensity is crucial. Explicit budgetary allocations and financial mechanisms are necessary to support policy implementation and signal governmental commitment to stakeholders.

While this study provides a comprehensive analysis of China’s climate policy mix, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our analysis focuses on national-level policies, potentially overlooking significant regional and local initiatives that contribute to China’s overall climate efforts. Given China’s top-down governance structure, provincial and municipal policies play crucial roles in policy interpretation, implementation, and innovation. Future research should incorporate sub-national policies to provide a more holistic understanding of China’s climate governance.

Second, the assessment of policy intensity is based on document analysis and coding on policy design, which may not fully capture the nuances of policy implementation and effectiveness on the ground. There may be discrepancies between policy design and actual practice due to factors such as institutional capacity, enforcement mechanisms, and stakeholder engagement. Empirical studies examining the implementation processes and outcomes of these policies would complement our findings and provide deeper insights into their real-world impacts.

Methods

Construction of the Database

Our research procedure began with collecting policy documents and establishing a database of national climate policies in China. The initial stage of policy data collection involved a comprehensive review of existing policy inventories. The Tufts Climate Policy Inventory was cross-referenced with the China Carbon Neutrality Tracker to ensure a comprehensive capture of national-level climate policies published between 2016 and 2022. To ensure the policy data is line with the research purpose, these policies were cross-checked with the climate actions outlined in China’s NDCs submitted to the UNFCCC. Subsequently, a systematic search of national and ministerial government websites was conducted utilizing a predefined set of keywords related to climate change and energy policy. The identified policies were then incorporated into the existing dataset.

Prior to the main coding phase, a detailed codebook was developed for categorizing policy instrument types and assessing policy intensity (see them in Supplementary Notes1 and 2). To ensure the applicability of the codebook to the policy context in China, the original English framework was adapted through rigorous progress of translation and pilot testing by the author team. Two rounds of pilot coding were conducted to refine the codebook and address challenges in interpreting and applying the English categories to policy documents in Chinese. This iterative process resulted in a robust codebook that accurately captured the meanings of the language used in China’s climate policy.

To enhance reliability, three researchers independently coded a sample of policies using the final codebooks, with a 14% overlap for intercoder reliability checks. Disagreements were then resolved through group discussion. For a detailed representation of how the policy document was coded, please refer to Tables S1a and S2a in the Supplementary materials.

Measuring policy density

To measure policy density, we calculate density at policy (document) levels, and sum density by both year and sector.

Measuring policy mix balance and instrument prevalence

For the policy mix balance, we follow the application from Schaffrin et al.22, the 1-Simpson Index45 using the equation below is calculated as the policy mix balance indicator.

We first identify different types of instruments within each policy document, following the nine-instrument framework proposed by Schmidt and Sewerin21. These nine types of instruments (Green Finance and Incentives, Regulatory Instruments, Education and Outreach, Research, Development and Demonstration (RD&D), Framework Policy, Tax, Voluntary Agreements, Tradable Permits, and Public Investment) are tracked by year and sector. Policy mix balance is then calculated using the 1-Simpson Index for each year and sector, where a value of 1 indicates a perfectly balanced mix of instrument types, and lower values signify a less balanced mix with a higher concentration of specific instrument types (details in the “Methods” and Supplementary note 1).

Equation to calculate 1-Simpson Index for Policy Mix’s Balance:

The 1-Simpson index (ranging from 0 to 1) measures policy mix balance. Applied to the entire policy mix, it represents the probability that two randomly selected policies are of different instrument types. A higher index value indicates greater balance across instrument types, while a lower value signifies lower balance (or higher concentration). Although balance is a novel characteristic and does not assess mix consistency, it offers a direct, independent measure. In our study, we calculate and aggregate balance annually and per sector.

To track the evolving landscape of policy instruments, we also analyze the popularity of different instrument types over time and across sectors. Recognizing that the “Regulatory Instruments” category has a higher level of abstraction compared to the other instrument types, we incorporated the typology from the Climate Policy Database51 to allow for more meaningful comparisons of instrument adoption trends.

For this purpose, we merged the original four economic-related instruments (Green Finance and Incentives, Tax, Public Investment, and Tradable Permits) into a single category called “Economic Instruments.” Additionally, we combined “Education and Outreach” with “RD&D” to form the “Information and Education” category. This revised typology provides a more consistent level of abstraction across categories, ensuring that our comparison of instrument adoption and popularity is robust and methodologically sound. This adapted typology allows for meaningful comparisons of policy instrument adoption trends while maintaining the original nine-instrument framework for the calculation of policy mix balance. It is worth noting that our calculation of the prevalence of instrument types does not measure the absolute number of each type of instrument. In other words, our approach only identifies the presence of a given instrument type in each policy document (e.g., 1 if a regulatory instrument is present, 0 if not). As a result, certain nuances—such as the total count of a specific type of instrument—are not captured. We acknowledge this limitation in our approach and invite future research to explore more granular assessments that consider absolute counts and stringency at the instrument level.

Validation on the assumption of 1-Simpson balance indicator

An important assumption underlying the interpretation of the policy mix balance index is that a more balanced policy mix that employs diverse policy instruments is more likely to address the target issues and reach relevant actors as much as possible21.

To verify this assumption and enhance the robustness of our research, we tested the correlation between the balance indices and the scope dimension of policy intensity, including target actors and target actions. As shown in Table 1, we found a statistically significant correlation between balance indices and the intensity score of actor and action. This correlation supports the notion that a balanced and diverse policy mix is associated with broader and more comprehensive policy reach.

Alternative measures of policy mix diversity

To provide a more comprehensive assessment of policy mix diversity, this section explores the application of additional metrics. Specifically, we explored two alternative indices of diversity, i.e., Shannon’s entropy52 and normalized-median evenness (NME)53. Similar to the 1-Simpson Index, a higher value of Shannon’s entropy and NME indicates a more diverse policy mix regarding its policy instrument types.

The equation below defines Shannon’s entropy:

where pm is the fraction of policies employing policy instrument m in the policy mix.

Based on Shannon’s entropy, Gauthier & Derome53 further proposed NME to better distinguish evenness (i.e., the extent to which different policy instruments are evenly distributed) from richness (i.e., the number of policy instrument types). NME can be expressed as follows.

We compared and tested the correlation between 1-Simpson Index, Shannon’s entropy and NME to examine the robustness of policy mix balance analysis. Descriptive results and correlation test results are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Measuring policy intensity

In our study, we drew on the index of policy activity (IPA)21,22,25 framework to assess the intensity of individual climate policies in China. The IPA delineates six key elements: integration, scope, objectives, budget, implementation, and monitoring. These elements serve as indicators of a policy’s overall intensity and are evaluated systematically. The intensity of each element is determined, resulting in a weighted score for each policy’s overall intensity. Aggregating these scores across policies within a given year and sector yields the overall IPA, providing an intensity score for the entire policy mix. To enhance the applicability of the IPA to the Chinese context, we introduce modifications to the intensity elements and grades, especially to ensure alignment of our scores with China’s NDCs. Below are our scoring systems for the six dimensions of policy intensity and more details can be found in Supplementary Note 2.

-

1.

The policy integration score (0–1) reflects how well the policy connects to other policies, with 1 given to framework policies or those linked to them, 0.5 for closely related policies, and 0 for unrelated policies.

-

2.

The scope score (0–1) has two components: The scope score assesses a policy’s breadth in terms of actor coverage and climate action coverage, each contributing up to 0.5 points for a maximum total score of 1.

We first evaluate the range of actors targeted by the policy, recognizing that broader actor inclusion enhances policy effectiveness. Actor coverage (0–0.5), where 0 is for one target group, 0.125 is added for each individual/company demand/supply group, 0.125 for state/government action, and 0.5 is for all groups;

Example of actor coverage scoring:

-

Policy example: A policy targeting supply-side companies and demand-side individuals.

-

1.

Calculation:

-

Base score: 0 (for the first actor group)

-

+0.125 for demand-side individuals (additional actor group)

-

Total Actor Coverage Score: 0.125

-

-

1.

-

Policy example: A policy targeting all actor groups.

-

1.

Total Actor Coverage Score: 0.5

-

1.

-

We then assess the number of climate actions addressed by the policy, based on key actions identified from China’s NDC Key Action Areas. And climate action coverage (0–0.5), where 0 is for one action, 0.1 is added for each additional action, up to 0.5 for all six actions. Six key climate actions were identified and summarized from China’s NDC Key Action Area.

They are (1) National strategies and institutional development; (2) Emission reduction actions in the energy sector (clean use of traditional energy sources and energy efficiency improvement, development of new energy sources); (3) Emission reduction actions in other sectors (buildings, transport, etc.) and cross-sectoral emission reduction actions; (4) Ecosystem carbon sinks; Green economy and carbon trading market construction; (5) Climate adaptation-related actions.

Example of climate action coverage scoring:

-

Policy example: A policy addressing emission reduction in the energy sector and ecosystem carbon sinks.

-

1.

Calculation:

-

Base score: 0 (for the first climate action)

-

+0.1 for ecosystem carbon sinks (additional action)

-

Total Climate Action Coverage Score: 0.1

-

Combined scope score calculation

-

1.

Total scope score = Actor coverage score+ Climate action coverage score

-

2.

Maximum total scope score: 1

-

1.

Note: Our assessment of scope is conducted at the individual policy level, allowing for a structured evaluation of each policy’s coverage. However, this approach does not fully capture how multiple narrow-scope policies within a sector and year may collectively result in a broad policy mix. Since our sector-year scope score is calculated as the mean of individual policy scores, it may underestimate the overall policy coverage when many targeted policies contribute to a comprehensive mix. We acknowledge this as a limitation and suggest that future research explore complementary measures to assess policy mixes.

-

3.

The objectives score (0–1) evaluate how closely the policy’s goal aligns with China’s first NDCs’ targets: 0 for no mention of targets, 0.125 for mentioning macro targets like “carbon peaking” or “carbon neutrality”, 0.25 for mentioning indirect/non-quantitative targets, 0.5 for mentioning indirect targets with specific percentages/numbers, 0.75 for mentioning direct climate targets without specifics, and 1 for mentioning direct climate targets with specific percentages/numbers from the NDCs.

Definition of direct and indirect objectives:

-

Direct objectives: Primary, quantitative targets explicitly outlined in China’s first NDCs:

-

1.

Carbon emissions peak: Achieve the peaking of carbon dioxide emissions around 2030 and make best efforts to peak earlier.

-

2.

Carbon intensity reduction: Lower carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by 60% to 65% from the 2005 level.

-

3.

Non-fossil fuel share: Increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20%.

-

4.

Forest stock volume: Increase the forest stock volume by around 4.5 billion cubic meters compared to the 2005 level.

-

1.

-

Indirect objectives: Policy goals that indirectly contribute to achieving the direct objectives. They may not be explicitly stated in the NDCs but are crucial for achieving the direct targets. Indirect objectives may include policies focusing on areas such as:

-

1.

Installed capacity: Increasing the capacity for renewable energy generation.

-

2.

Power generation volume: Boosting the amount of energy produced from non-fossil fuel sources.

-

3.

Energy efficiency: Enhancing efficiency in various sectors to reduce energy consumption intensity. For example, a policy aiming to “Improve energy efficiency in the industrial sector by 10% by 2025” supports the Carbon Intensity Reduction target indirectly and would score 0.5.

-

1.

Note: If a policy relates to multiple objectives, we record only the highest applicable score.

-

4.

The budget score (0–1) The budget score reflects the level of financial commitment indicated in the policy, which is crucial for its effective implementation. The scoring criteria are: 0 for no budget mention, 0.5 for a general reference, and 1 for a specific amount.

Example: a policy stating, “In 2021, the total central subsidy funds for biomass power generation are 2.5 billion yuan, of which: 2.0 billion yuan is allocated for non-competitive allocation projects” The policy provides specific budget amounts and detailed allocations so graded with 1.

Note: policies that only collect revenue (e.g., a tax instrument) without detailing public spending or dedicated funds do not receive a budget score.

-

5.

The implementation score (0–1) assesses clarity and rigor of a policy’s implementation details. The scoring criteria are:

-

0 for no mention of procedures,

-

+0.25 for each of the following elements, up to a maximum of 1:

-

1.

Assigning implementation responsibilities to actors and establishing rules.

Example: The policy specifies that the “Ministry of Environment is responsible for enforcing emission standards.”

-

2.

Coordinated implementation involving one or more actors.

Example: The policy states that “the National Development and Reform Commission will collaborate with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology to implement energy-saving measures.”

-

3.

Strict procedures with no flexibility in standards or rules.

Example: The policy mandates “all new industrial projects must meet advanced energy efficiency levels without exceptions.”

-

4.

Sanctions for non-compliance.

Example: The policy indicates that “regions failing to meet targets will have their responsible officials held accountable according to regulations.”

-

1.

-

-

6.

Finally, the monitoring score reflects the robustness of the policy’s monitoring mechanisms:

-

0 for no monitoring,

-

0.5 for monitoring by the implementing agency

Example: the policy notes that “the National Energy Administration will oversee and monitor the implementation of renewable energy projects.”

-

1 for independent monitoring or a dedicated monitoring entity.

Example: the policy establishes “a new independent committee to monitor and report on climate change initiatives.”

-

Detailed grading criteria and more examples are provided in Supplementary Note 2 for further reference.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed in this study are included in the article and its supplementary materials files. The raw data of all policies analyzed and their instruments and intensity scores were uploaded in the Dataset file.

References

Schaub, S., Tosun, J., Jordan, A. & Enguer, J. Climate policy ambition: exploring a policy density perspective. Polit. Gov. 10, 226–238 (2022).

Steinebach, Y., Hinterleitner, M., Knill, C. & Fernández-i-Marín, X. A review of national climate policies via existing databases. npj Clim. Action 3, 80 (2024).

Roelfsema, M. et al. Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 11, 12 (2020).

Skjaerseth, J. B., Andresen, S., Bang, G. & Heggelund, G. M. The Paris agreement and key actors’ domestic climate policy mixes: comparative patterns. Int. Environ. Agreem. 21, 59–73 (2021).

Rogge, K. S., Kern, F. & Howlett, M. Conceptual and empirical advances in analysing policy mixes for energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 33, 1–10 (2017).

Li, Y. S., Judith. China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet. 240 (WILEY, 2020).

Shao, J. & Huang, P. The policy mix of green finance in China: an evolutionary and multilevel perspective. Clim. Policy https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2023.2202181 (2023).

Li, L. L. & Taeihagh, A. An in-depth analysis of the evolution of the policy mix for the sustainable energy transition in China from 1981 to 2020. Appl. Energy 263, 12 (2020).

Duan, H. B., Mo, J. L., Fan, Y. & Wang, S. Y. Achieving China’s energy and climate policy targets in 2030 under multiple uncertainties. Energy Econ. 70, 45–60 (2018).

Gallagher, K. S., Zhang, F., Orvis, R., Rissman, J. & Liu, Q. Assessing the Policy gaps for achieving China’s climate targets in the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 10, 10 (2019).

Ma, W. T., de Jong, M., de Bruijne, M. & Mu, R. Mix and match: configuring different types of policy instruments to develop successful low carbon cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 282, 14 (2021).

Teng, F. & Wang, P. The evolution of climate governance in China: drivers, features, and effectiveness. Environ. Polit. 30, 141–161 (2021).

Röser, F., Widerberg, O., Höhne, N. & Day, T. Ambition in the making: analysing the preparation and implementation process of the Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 20, 415–429 (2020).

Li, Z. & Hanaoka, T. Plant-level mitigation strategies could enable carbon neutrality by 2060 and reduce non-CO2 emissions in China’s iron and steel sector. One Earth 5, 932–943 (2022).

Qi, T., Winchester, N., Karplus, V. J., Zhang, D. & Zhang, X. An analysis of China’s climate policy using the China-in-Global Energy Model. Econ. Model. 52, 650–660 (2016).

Duan, H. B. et al. Assessing China’s efforts to pursue the 1.5°C warming limit. Science 372, 378–385, (2021).

Cheng, J. et al. A synergistic approach to air pollution control and carbon neutrality in China can avoid millions of premature deaths annually by 2060. One Earth 6, 978–989 (2023).

Cui, Q. & Lei, Y.-l Pathways analysis to reducing aircraft emissions for China-Foreign routes. npj Clim. Action 2, 15 (2023).

Nascimento, L. & Höhne, N. Expanding climate policy adoption improves national mitigation efforts. npj Clim. Action 2, 12 (2023).

Xiang, C., Zheng, X., Song, F., Lin, J. & Jiang, Z. Assessing the roles of efficient market versus regulatory capture in China’s power market reform. Nat. Energy 8, 747–757 (2023).

Schmidt, T. S. & Sewerin, S. Measuring the temporal dynamics of policy mixes—an empirical analysis of renewable energy policy mixes’ balance and design features in nine countries. Res. Policy 48, 103557 (2019).

Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S. & Seubert, S. The innovativeness of national policy portfolios—climate policy change in Austria, Germany, and the UK. Environ. Polit. 23, 860–883 (2014).

Howlett, M. & Cashore, B. The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: understanding policy change as a methodological problem. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 11, 33–46 (2009).

Rogge, K. S. & Reichardt, K. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: an extended concept and framework for analysis. Res. Policy 45, 132–147 (2016).

Schaffrin, A., Sewerin, S. & Seubert, S. Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Stud. J. 43, 257–282 (2015).

Bauer, M. W. & Knill, C. A conceptual framework for the comparative analysis of policy change: measurement, explanation and strategies of policy dismantling. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 16, 28–44 (2014).

Pischke, E. C. et al. From Kyoto to Paris: measuring renewable energy policy regimes in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Mexico and the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 50, 82–91 (2019).

Ran, R. Perverse incentive structure and policy implementation gap in China’s local environmental politics. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 15, 17–39 (2013).

Qi, Y. & Wu, T. The politics of climate change in China. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 4, 301–313 (2013).

Li, X., Pattberg, P. & Widerberg, O. China’s climate governance from 2009 to 2019: motivations, instruments, actors, and geopolitics. Clim. Policy 24, 378–395 (2024).

Gong, W. L. Temporary leaders and stable institutions: how local bureaucratic entrepreneurs institutionalize China’s low-carbon policy experiments. China Q. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305741022000790 (2022).

Westman, L. K., Broto, V. C. & Huang, P. Revisiting multi-level governance theory: Politics and innovation in the urban climate transition in Rizhao, China. Political Geogr. 70, 14–23 (2019).

Hepburn, C. et al. Towards carbon neutrality and China’s 14th Five-Year Plan: Clean energy transition, sustainable urban development, and investment priorities. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 8, 8 (2021).

Xu, W. H., Xie, Y. L., Xia, D. H., Ji, L. & Huang, G. H. A multi-sectoral decomposition and decoupling analysis of carbon emissions in Guangdong province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 298, 13 (2021).

Yu, H. China’s Energy Transition: Approaches, Progress, and Prospects. China Q. Int. Strateg. Stud. 08, 175–195 (2022).

NDRC. (ed National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)) 219 (https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202105/P020210527785800103339.pdf 2016).

Gilley, B. Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environ. politics 21, 287–307 (2012).

Alkon, M. & Wong, A. Authoritarian energy transitions undermined? Environmental governance cycles in China’s power sector. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 68, 101531 (2020).

Guan, T. & Delman, J. Energy policy design and China’s local climate governance: energy efficiency and renewable energy policies in Hangzhou. J. Chin. Gov. 2, 68–90 (2017).

Li, W. & Jia, Z. J. Carbon tax, emission trading, or the mixed policy: which is the most effective strategy for climate change mitigation in China? Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 22, 973–992 (2017).

Davidson, M., Karplus, V. J., Zhang, D. & Zhang, X. L. Policies and Institutions to Support Carbon Neutrality in China by 2060. Econ. Energy Environ. Policy 10, 7–24 (2021).

Chen, X. & Lin, B. Towards carbon neutrality by implementing carbon emissions trading scheme: Policy evaluation in China. Energy Policy 157, 112510 (2021).

The Climate Policy Lab at The Fletcher School, T. U. (https://www.climatepolicylab.org/national-climate-policy-inventories).

Progress-iGDP, I. f. G. D. (Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, https://ccnt.igdp.cn/en/action-database).

Simpson, E. H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 163, 688–688 (1949).

Knill, C., Schulze, K. & Tosun, J. Regulatory policy outputs and impacts: Exploring a complex relationship. Regul. Gov. 6, 427–444 (2012).

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S. & Auld, G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sci. 45, 123–152 (2012).

Sewerin, S., Cashore, B. & Howlett, M. New pathways to paradigm change in public policy: combining insights from policy design, mix and feedback. Policy Polit. 50, 442–459 (2022).

Lo, K. How authoritarian is the environmental governance of China? Environ. Sci. Policy 54, 152–159 (2015).

Nilsson, M. et al. Understanding Policy Coherence: Analytical Framework and Examples of Sector–Environment Policy Interactions in the EU. Environ. Policy Gov. 22, 395–423 (2012).

Agency., N. I. W. U. A. R. A. P. N. E. A. (NewClimate Institute; Wageningen University and Research & PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency., 2023).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Gauthier, J. & Derome, N. Evenness-Richness Scatter Plots: a Visual and Insightful Representation of Shannon Entropy Measurements for Ecological Community Analysis. mSphere 6, https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.01019-01020 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sebastian Sewerin for his valuable comments on early versions of the intensity coding scheme. We are also grateful to Karin Ingold, Marlene Kammerer and Paula Castro for inviting us to present our work in the Policy Indices Workshop at the University of Bern in March 2024 and constructive feedback provided by the workshop participants. In addition, Mathieu Blondeel and other colleagues at VU Amsterdam provided helpful feedback on an early draft. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which helped strengthen the quality of this work. X.L.’s work was supported by the China Scholarship Council (Grant Number 201906360164) as well as the GeoClimRisk Project of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, funded by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) on behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office as part of the Climate Diplomacy Action Programme (CDAP), and implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Y.G.’s work was supported by the China Scholarship Council’s studentship at the University of Bath. Y.S.’s work was supported by the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/X035956/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. L. Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration. S. H. Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing. Y. G. Investigation, Validation. Y. S. Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., He, S., Gu, Y. et al. Unpacking China’s climate policy mixes shows a disconnect between policy density and intensity in the post-Paris era. npj Clim. Action 4, 30 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00233-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00233-6

This article is cited by

-

Interactive effects of climate physical risks, climate policy uncertainty, and sustainable energy transition in China

Discover Sustainability (2025)