Abstract

Urban biodiversity has recently emerged as a key focus in urban planning discourse and is the cornerstone of the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030. This strategy proposes ambitious urban greening plans for cities with over 20,000 inhabitants to address urban biodiversity holistically. In their way of developing urban biodiversity-based imaginaries, future uncertainties, complex terminology, and data attainability hinder the efforts of small to large cities in addressing urban biodiversity satisfactorily. Based on comparative case studies of Heidelberg, Hanover, Cesena, and Florence, we developed explorative research that sources from urban, social, and political science methods that investigate the complexity of urban biodiversity between past experiences, present discourses, and future imaginaries. By analysing policy documents, urban actors’ discourses, and the physical manifestation of the UGPs in these four cities, we argue that size does not matter. Instead, cultural and communication gaps should be addressed behind an underdeveloped and superficial public debate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nature has always played an important role in urban settlements. Based on the first studies on ecosystems in the urban context in the 1970s1,2, urban biodiversity research started concentrating, among others, on how urban planning copes with natural elements within the built environment3,4,5. In the European context, the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 (EU-BDS) provides a reference for urban planning in the member states to address urban biodiversity. The EU-BDS proposes a scenario for reversing the disappearance of green spaces, acknowledging that urban biodiversity plays a central role in increasing humans’ physical and mental well-being. To accomplish this reversion, the EU-BDS is urgently calling for cities “with at least 20,000 inhabitants to develop ambitious urban greening plans (UGP) by the end of 2021” to bring nature back into our lives (Target 14, p. 13 ref. 6). A UGP represents an opportunity for cities to promote a holistic view of urban biodiversity by being properly integrated into urban planning, policies and practices across Europe (p. 7 ref. 7). The following year, the UGP was renamed the urban nature plan (UNP), reflecting the EU’s evolving sensibility toward nature beyond just greenery8. Nevertheless, the what, who and how of integration are fundamental questions the EU-BDS does not thoroughly address. Additionally, there is the risk that the bland request from the EU does not represent a sufficient push for cities to engage in the draft of such plans. Especially for smaller cities, which are known to lack resources and expertise, draughting and implementing a UGP may be difficult. To obtain economic support from the national and the EU level, cities are asked to quickly develop narratives of innovations, often resulting in unrealisable promises9. Haarstad et al. recently developed a critical stance of this ‘politics of urgency’’ according to which some actors’ interests, valuable discourses and alternative possibilities may be discarded or left unseen in the name of quickly responding to urgent challenges (pp. 3–5 ref. 10). This approach tends to disregard conflicts and resistance in favour of an apolitical understanding of climate change-related actions11.

According to Westman and Castán Broto, urban planning is living in an era in which cities are governed and designed following climate change-related narratives. By defining urban climate imaginaries as “collective discourses surrounding the urban that reflect the aspirations of [the] future”, they argue that the formation of future imaginaries is a result of discursive practices, whereby certain visions of the future are more convincing than others (p. 80 ref. 12). As the future is, per definition, unknown, decisions on ‘the’’ future to enact are not only the result of rational choices. Rather, actors decide based on a complex system of personal beliefs and interpersonal influences formulated as a narrative exercise to convince the hearing with the most credible scenarios13. Those most credible imaginaries pervade the discourse over valid alternatives that, lacking authoritative support, are automatically excluded from the debate14. Three decades ago, Maarten Hajer described the discursive process of environmental policies, arguing that “[a]ny understanding of the state of the natural (or indeed the social) environment is based on representations” (p. 17 ref. 15). His discourse-coalition approach suggests that groups of actors form coalitions when sharing common ideas, out of which convincing storylines are produced and reproduced16. With this perspective, the argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning understands actors’ discourses as their ability to shape reality through which it is possible to explain reasons for action or non-action attributable to personal and shared beliefs of the world17.

Thus, exploring the dynamics by which urban actors form discourse coalitions around urban biodiversity’s future(s) is relevant to understanding how urban biodiversity planning can be transformed4,5,10. We have observed an exponential interest in urban biodiversity and climate change in urban studies, focusing especially on the reasons for the action and inaction of public administrations. The majority agree that the absence of an overarching vision and governance schemes allowing cross-collaboration are the main obstacles to urban biodiversity planning and implementation. However, how different narratives are discussed is rarely addressed in the urban planning literature (Supplementary Note 1).

While many concepts that refer to nature in the city exist, it appears beneficial for the purpose of this paper to refer to urban biodiversity as this concept is well-defined in the scientific literature; additionally, biodiversity is explicitly used in the EU-BDS. Departing from the understanding of urban biodiversity as “the variety and richness of living organisms […] and habitat diversity in and on the edge of human settlements” (p. xvii ref. 18), our urban planning perspective focuses on the interplay between natural elements and human beings. Following urban biodiversity research19, we refer to urban biodiversity as the variety and richness of living organisms and habitats within the built environment and the perception that humans have about this relationship. We argue that approaching urban future imaginaries based on this definition of urban biodiversity from a discourse perspective can be beneficial in improving the understanding of how these futures are discussed and how they influence actors’ imaginations and the physical environment. We refer to urban biodiversity-based imaginaries as collective discourses about desirable futures based on urban biodiversity debated among coalitions of urban actors in the present, informed by past experiences, and that materialise in future-oriented policy documents. The adjective “desirable” explicitly refers to the efforts of urban actors in building such imaginaries essentially “grounded in positive visions of social progress” (p. 4 ref. 20). Because cities with at least 20,000 inhabitants are directly addressed by the EU-BDS, and small- to large-sized cities have a higher share in Europe than in other continents21, it seems worthwhile to explore these kinds of cities in this research. Therefore, we ask: How do urban actors discuss the construction of urban biodiversity-based imaginaries and their translation into urban projects in small and large cities?

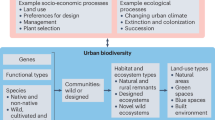

With reference to the definition of urban biodiversity provided in this paper, we focus our analysis on the relationships between natural elements and humans within the built environment from a discourse perspective. Thus, we have organised our research into three dimensions to answer our research question (Fig. 1). First, we acknowledge that various urban actors have different perceptions of urban biodiversity, which are highly controversial because linked to subjective values rooted in each country’s planning system and culture and each person’s past4,14. By accounting for legal requirements and cultural beliefs, we want to investigate the context that determines how urban actors understand urban biodiversity in the first place. Second, the bargaining effort we intend to investigate implies a dialogical relation between these different understandings in the present as an attempt to shape reality15. Thus, we aim to study how urban actors form discourse coalitions to communicate urban biodiversity publicly and which strategy they use to discuss urban future imaginaries. Third, the result of the discussion is reflected in the physical manifestation of the urban actors’ imaginations in urban planning documents12,20. Here, we look at how urban actors imagine urban biodiversity as the materialisation in the UGPs of urban biodiversity-based imaginaries and their influences on the urban environment.

With a relational perspective on urban biodiversity, our research design integrates different urban, social and political science methods. We conduct a comparative case study analysis to infer differences and similarities between small- and large-sized cities in the EU. The selection of the case studies focuses on identifying outstanding cities in planning and implementing urban greening. We refer here to this sample as committed cities. The final selection comprises Heidelberg and Hanover in Germany and Cesena and Florence in Italy (Fig. 2). First, we perform a policy document analysis to provide an overview of each city’s policy context on different levels (national, regional and local). Second, we look into each city’s current UGPs (June 2024) to understand how urban biodiversity is framed. The dynamics between the discourse and the diverse actors that are ideationally connected and form discourse coalitions are studied through a discourse network analysis (DNA), a combination of qualitative content and social network analysis (SNA). Discourse analysis studies language-in-use, which aims to understand how knowledge is produced and reproduced between actors through analysing written texts (p. 176 ref. 22). SNA is a method to visualise and study relational empirical evidence. The information is visualised in network graphs, with nodes often representing actors (or other entities) and ties representing a relationship between them (such as communication, exchange or sharing of the same beliefs). DNA offers a new perspective to trace the coevolution of actors and issues dynamically over time23. This method allows the operationalisation of the content and the structure of the discourse on a respective issue24. Using local newspaper articles, we can trace the narrative evolution around urban biodiversity-based imaginaries of diverse urban actors forming discourse coalitions in the public debate. Through spatial analysis and fieldwork, we investigate how discourse influences the physical world by understanding the geography of the projects debated in the newspaper articles. Finally, the knowledge acquired through the methods above is validated and complemented through semi-structured interviews with the main actors involved in producing such imaginaries.

This figure shows the details of the four committed cities analysed in this paper: Heidelberg, Hanover, Cesena and Florence. For each city, data are reported as follows: population; political composition of the city council; policy documents at various levels; n. of newspaper articles analysed; n. of statement coded. The documents are categorised as follows according to the German and Italian systems: federal o regional (R), regional or metropolitan (M), local (L), and UGP (U).

Results

Understanding urban biodiversity

Influenced by geographies, the object of urban biodiversity has changed considerably over time and, accordingly, the ways through which human beings have dealt with nature in the urban context25. Choosing a definition thus has implications on urban biodiversity planning concerning which forms of nature are included or excluded, by whom, and for what purposes (p. 308 ref. 4). This section provides information from policy documents—considering formal and informal planning—at different levels of governance—EU, national, regional and local—and expert interviews to identify current cultural influences and planning practices about urban biodiversity. For a thorough analysis of the national level, refer to Arlati26.

Heidelberg is a city in the federal state (Bundesland) of Baden-Württemberg and one of the first members of the Alliance of Local Authorities for Biological Diversity. The federal state’s strategy for natural protection has set objectives for protecting nature in the urban environment since February 2014 (pp. 14-15 ref. 27). It fosters the concept of the compact city (Stadt der kurzen Wege) as the main planning framework for urban development, which considers both the living quality of people and biodiversity (ibid., p. 34). On July 31, 2020, the federal state draughted the Biodiversity Strengthening Law (BiodiveStärkG), showing a strong commitment towards biodiversity at the federal-state level28. Referring to the National Strategy on Biological Diversity (Nationalen Strategie zur biologische Vielfalt) of 2007, Heidelberg is aligned with many other cities to reach the goals of this strategy by sharing the implementation between federal, state and local authorities. Noteworthy, 40% of Heidelberg municipal territory is occupied by an urban forest (Heidelberger Stadtwald). Together with the Neckar River, these two natural elements provide relevant leisure opportunities for people and space for nature to thrive. However, the urban forest and river system reduce the land for further urban development, increasing land use-related conflicts significantly. The national level is, however, mentioned as the reference point for the local biodiversity strategy. In its strategy, the city of Heidelberg states that achieving the goals and implementing the measures will be a joint task within the municipalities. This applies to the actors in the public sector and the public itself, which must be involved in implementing measures. Potential conflicts mentioned in the document highlight that species, nature, and climate protection goals can collide with those of a municipality’s economic growth and housing development. In Heidelberg, the influences from the EU-BDS are not claimed in the documents analysed, as these were draughted before the publication of the European strategy. The interviewees from the landscape office and an environmental organisation (HE_1, HE_2, HE_3) defined biodiversity from a more practical perspective, giving various examples such as maintaining or increasing tree cover in the city, green roofs, selecting high-quality plants (in terms of biodiversity benefits), greening facades, greening open spaces and squares and removing sealed surfaces.

Hanover is the capital city of the federal state Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony) and became the Federal Capital of Biodiversity in 2011. It is a founding municipality of the Alliance of Local Authorities for Biological Diversity. Biodiversity refers to the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (Bundesamt für Naturschutz) and includes species diversity, ecosystem variety and genetic differences within species. Accordingly, providing clean water, fresh air, a stable climate and fertile soil is vital for human quality of life and survival. Animals, plants, fungi and microorganisms are essential in maintaining these conditions (p. 6 ref. 29). The topic of integration with other policy fields is highlighted in the federal state’s strategy. The intermediary level of the Hanover Region provides additional instruments to guide landscape and spatial planning, stating that the landscape should be permeable to protect biodiversity and that cities should be structured by green corridors (p. 19 ref. 30). The ‘More Nature in the City’’ programme launched in 2009 by the City of Hanover aimed to secure and improve biodiversity through sustainable use. As part of the federal ‘Biodiversity’’ programme, Hanover has participated in the five-year cooperation project ‘Cities Dare Wilderness’’ since 2016. At the same time, a pilot programme called Urban Greenery—Species-rich and Diverse (Stadtgrün—Artenreich und Vielfältig) within the “National Strategy on Biological Diversity at Municipal Level” had been implemented. Hanover’s sensitivity towards urban biodiversity is attributable to both the EU-BDS and the white and green papers at the national level31. The head of the department of urban greenery defines urban biodiversity as primarily sustainable. This means that it should be planned from a long-term perspective, with more free spaces of high quality against their impact on nature conservation, species protection, and biodiversity. The aim is to preserve these green spaces equally with their effects on climate protection and climate change adaptation (HA_1). One interviewee (HA_2), an expert who has campaigned for biodiversity for many years as part of the insect alliance, refers to the UN definition of biodiversity, which includes diversity within species and ecosystems. Both areas are key recreational spaces in Hanover, providing residents and visitors with beautiful natural environments. Like Heidelberg, Hanover praises an important experience with the biodiversity topic mirrored in the richness of the interviewees’ definitions.

Cesena is a city in the Emilia–Romagna region. The regional strategy for mitigation and adaptation to climate change mentions urban greening concerning air quality in urban development, while biodiversity is addressed only in areas outside the urban fabric32. A more direct connection is present in the Agenda 2030 strategy, which aims to plant 4.5 million trees in the next five years to support regional urban biodiversity33. At the local level, the action plan for sustainable energy and climate describes urban biodiversity as important to counter climate change-related disasters and to foster health and security34. In the current local urban plan, draughted with the neighbouring city to share the efforts and resources (CE_1b), biodiversity is addressed, mainly outside the urban environment, as in the regional policies. However, the interviewees have reported a more holistic understanding of urban biodiversity: from the public administration view, urban biodiversity is defined as infrastructure, thus providing services to the city, such as water and air systems (CE_1a; CE_1b), while from the citizen initiative, through the concept of habitat, suggesting that green spaces in the built environment function as contact between nature and other layers of the cityscape, such as mobility (CE_2). The interviews also revealed that a unique document addressing urban biodiversity planning at the local level is currently missing, whereby taking consistent action is difficult for the urban actors. This also hinders access to information for citizens who want to inform themselves about this topic. The public administration interviewee reported rather limited support from the regional level concerning urban biodiversity planning, which de facto contributes only economically (CE_1a). The necessity to gather experience pushed Cesena to look at the international context, subscribing to the Green City Accord on December 21, 2020. With the commitment to addressing urban planning with projects related to biodiversity, this subscription was vital for Cesena for three reasons: first, the funds offered by the accord were consistent and purposefully organised; second, it allowed them to share experiences in a network of cities; and third, it provided a set of quantitative indicators to benchmark its advancements practically (CE_1b).

Florence is the capital of the Tuscany region. At the regional level, policy objectives related to urban biodiversity are stated by the strategic regional framework for sustainable and just development covering 2021–2027. The aim is to foster an ecological transition for a greener Toscana to contrast climate change by supporting biodiversity in the urban context and reducing pollution (p. 35 ref. 35). At an intermediate level, the sustainable development strategy of the Metropolitan City of Florence suggests in one of its ten objectives to address climate mitigation and adaptation through reforestation and urban greening measures (p. 33 ref. 36). At the city level, the urban plan of Florence, although relatively old, considers private and public urban greening simultaneously as an integrated part of the planning process (p. 62 ref. 37). Although awareness seems to be relatively high, Florencethe interviewees described Florence as a complicated city that has to deal with several problems linked to its historical traditions. On the one hand, there is the presence of conservatism from politicians and professionals (FI_1), whereby historic gardens and landscapes should not be ruined by introducing new species or realising new greening respectively (FI_2). On the other hand, Florence has to deal with mass tourism every year: being a rather small and dense city, this creates considerable land use problems when planning for urban biodiversity, especially in the city centre. The EU Green Deal, in particular, is an important reference for Florence, which points to realising urban biodiversity under the flag of ecological transition and environmental justice. Through the engagement of citizens, implementing nature in the urban context becomes an occasion to share and live in the city as a tool of climate democracy (FI_1). The complexity of the urban environment of Florence and the need to valorise every square metre translates into the understanding of urban biodiversity as composed of big parks and small natural elements found within brick walls: urban biodiversity is considered thus a concept through which open spaces can be planned (FI_1; FI_2) or even left unplanned (FI_3).

Communicating urban biodiversity

Urban actors who share the same understanding form coalitions centred around storylines that strengthen their common interests (p. 65 ref. 16). This section presents our results from observing the dynamic evolution of the public debate from the local news using DNA with the support of expert interviews. Because of readability, the figures presented in this section depict only the year with the highest frequency of nodes and the last 12 months of data collection. A complete picture of the graphs year by year can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

In Heidelberg, several actors are involved in the debate on urban biodiversity conservation (Fig. 3). The Landscape and Forestry Department (Landschafts- und Forstamt) and the municipal administration are the primary driving forces, supported by the environmental organisation NABU and engaged citizens. The dominant concepts in the debate are ‘urban greening for biodiversity’’ and ‘for humans’’. The debate has gradually evolved, yet it has not reached the intensity initially anticipated. Notably, there is a discrepancy between the intended and actual use of public space, which has become a prominent issue in 2022. One interviewee highlighted the importance of the Landscape and Forestry Department but also pointed to internal conflicts with the Urban Planning Office when it comes to implementing or maintaining green spaces (HE_2). Another interviewee from an environmental NGO mentioned that there seemed to be a lack of communication and coordination between departments (HE_1). The interviewee further explained that in the conflict between housing and greenery in the city, the former always wins. According to the interviews, there has been a recent shift in public opinion, with citizens emphasising trees and greenery in urban areas since 2018–2020. One interviewee posited that urban planners frequently designed public spaces without incorporating green spaces, a practice that is no longer tenable today (HE_2). In the interviews, the importance of biodiversity had been pronounced, such as a leading manager (HE_2) from the landscape office stating, “… everyone agrees: We need more greenery; we need more trees. We must take a stand against … the overheating of our cities.” It is important to mention that the public debate on biodiversity is not very extensive. The presence of the Stadtwald and of the green areas around the Neckar River probably generate a conviction that the existing green areas suffice. Even if we look at which public areas are being discussed, there are only a few areas in the old city centre (Fig. 8).

The figure depicts one-mode networks for the year with the highest frequency of nodes (left) and one-mode networks for the last 12 months of analysis (right) for Heidelberg. Only the top ten frequent nodes are visualised. The size of the nodes represents the frequency (number of times the concept or organisation appear in the articles in the respective time). The strength of the links is bigger according to the edge weight (number of concepts the actors share with each other or the number of actors that mention the same concepts in the respective time). The organisations are citizens (cyan), economy (yellow), grassroots initiative (green), NGO (red), politician (light blue), public administration (blue), public-sector economy (light green), and science and education (pink) (Supplementary Note 3).

In the case of Hanover, the dominant concepts are the ‘conflicting use of public spaces’ and ‘urban greening for biodiversity conservation’ (Fig. 4). The discussion then moved on to the proposition that green spaces are crucial for biodiversity conservation. The discourse analysis revealed that the Department of Environment and Urban Greenery (Fachbereich Umwelt und Stadtgrün) plays a pivotal role in the debate, demonstrating notable engagement and influence. The findings of our interview with a department representative in question corroborate this impression. The situation in Hanover is characterised by a positive tradition, with a significant number of historic gardens and a culture that supports and appreciates them. Furthermore, greening activities are supported in both the debate and practice by a diverse range of actors, including political parties, the media, and citizens. The discourse is developing from a very limited (2020) to a differentiated discourse (2024). One expert in a leading position in the Department of Environment and Urban Greenery (HA_1) confirmed a high level of awareness of green issues or ecological concerns in urban society. Hanover is a city of gardens, with the Eilenriede and the Herrenhausen Gardens, for example, and many other historic green spaces and parks (HA_3). The interviewee defined urban biodiversity and emphasised the importance of native plants. Although urban greenery has a high status in the consciousness of citizens, it is crucial to know which plant species are present. Another interviewee (HA_2) recalled that funding has also been made available for biodiversity, and positions for maintenance and care have been created. Adequate administrative infrastructure and a supportive political climate are crucial for submitting applications and implementing biodiversity measures. According to this person interviewed, the Krefeld study in 2018, an important scientific study documenting a dramatic decline in insect biomass in Germany, brought the issue of insect mortality to the attention of the general public and the insect alliance was founded (HA_2). This insect alliance is characterised by considerable support and influence and a notable level of visibility (HA_2). The insect alliance has focused on clear communication and unites different urban actors who joined voluntarily without any membership fee under a common logo (HA_3).

The figure depicts one-mode networks for the year with the highest frequency of nodes (left) and one-mode networks for the last 12 months of analysis (right) for Hanover. Only the top ten frequent nodes are visualised. The size of the nodes represents the frequency (number of times the concept or organisation appear in the articles in the respective time). The strength of the links is bigger according to the edge weight (number of concepts the actors share with each other or the number of actors that mention the same concepts in the respective time). The organisations are citizens (cyan), economy (yellow), grassroots initiative (green), NGO (red), politician (light blue), public administration (blue), public-sector economy (light green), and science and education (pink) (Supplementary Note 3).

Since 2020, the importance of biodiversity has permeated the discourse in Cesena, probably linked to the awareness derived from the subscription to the Green City Accord (Supplementary Fig. 13). In this period, actors frequently mention the concepts of ‘participation’’ and ‘implementation of new green’’ projects to underline the necessity to cooperate and expand and enhance city green areas. The discourse coalition in the debate comprises various actors: the public administration and other political groups (e.g., PD Cesena) play a dominant role (Fig. 5 bottom). Another important organisation is the Citizens Council for the Environment (Consulta per l’Ambiente (CpA)), which was formed with the help of the public administration (Supplementary Fig. 13, year 2021). Through this council, which has mainly a consulting function but can propose new ideas, economic actors, NGOs, and citizens can be directly involved in the decision-making about environmental topics. At this point, we can observe a rather broad coalition of actors in the debate about urban biodiversity-related arguments, including politicians, public actors, and laypersons. Interestingly, Cesena is the only case linking urban biodiversity as a measure to address health issues, probably related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, concepts of ‘security’’ and ‘requalification’’ have acquired more importance, while social-related concepts (such as ‘participation’’ and ‘other imaginaries’’) are less central (Fig. 5 top-left). This happened at the expense of a more consistent involvement of the CpA, as reported in an interview with the citizen initiative (CE_2). The NGOs were particularly active but suffered from a too-ideologic perspective that led to many proposals being discarded; similarly, economic actors saw their pragmatism as being outclassed by such actors and lacked the time and resources to keep being involved voluntarily (CE_2). At this stage, the debate seems more centralised around the public administration and its departments, whereby citizens and grassroots initiatives are even disjointed from the main coalition (Fig. 5 bottom-left). In 2023, the biodiversity topic has gradually left the debate, favouring greater attention to ‘disaster prevention’’ linked to a great flood that occurred in the Region. This concept was used in the local elections of May 2024, creating relevant divides in the political parties. In the last year of analysis, we witnessed a reversed trend when ‘cross-collaboration’’ returned as a central concept, showing the need to involve other organisations in greening measures (Fig. 5 top-right). The discourse coalition is highly diversified, including different levels of governance and political parties. This reflects the willingness of the newly elected government to maintain a relationship with the citizens and the CpA. However, the interviews depict a scenario where citizens reactively engage with urban biodiversity, thus perceiving the work of the public administration as an attack on urban green spaces (CE_1a).

The figure depicts one-mode networks for the year with the highest frequency of nodes (left) and one-mode networks for the last 12 months of analysis (right) for Cesena. Only the top ten frequent nodes are visualised. The size of the nodes represents the frequency (number of times the concept or organisation appear in the articles in the respective time). The strength of the links is bigger according to the edge weight (number of concepts the actors share with each other or the number of actors that mention the same concepts in the respective time). The organisations are citizens (cyan), economy (yellow), grassroots initiative (green), NGO (red), politician (light blue), public administration (blue), public-sector economy (light green), and science and education (pink) (Supplementary Note 3).

In Florence, concepts of ‘participation’’ and ‘cross-collaboration’’ are central to the local debate of 2020, while the actual measures have a secondary importance. The public administration is very active in this process; this is the case for the government and specific departments (Fig. 6 bottom-left). From 2021 to 2022, the concepts of ‘urban greening for humans’’ and ‘biodiversity’’, the push towards ‘requalification’’ projects and problems related to ‘security’’ acquire more relevance, showing a more action-oriented discourse (Supplementary Fig. 14). This might be linked to the draft of the EU Green Deal and the EU-BDS at the end of 2020. Since 2022, more diverse types of organisations have started to participate in the greening discourse, building complex networks among them and reducing the centrality of the municipal actors (Fig. 5 bottom-left). While the debate seems multifaceted initially and mainly populated by governmental actors, it evolves into a more precise and concrete debate about ‘financial aspects’ and conflictual situations related to ‘practices of tree cuts@ in which economic actors and politicians participate. The years from 2022 to 2024 correspond to some of the most conflictual situations, whereby groups of citizens react heavily to the actions of the public administrations (FI_1). Accordingly, a researcher interviewed specifies that citizens and grassroots initiatives lack the expertise to understand the operations of the public administrations (FI_2): political actors take advantage of this situation to oppose key decisions, such as the planting action in the urban centre and the tree cuts in ‘Viale Redi and Viale Corsica’ (Fig. 8). These approaches are explained by relative mistrust in the political class and a generally low awareness towards implementing natural elements in favour of more graspable topics such as mobility (FI_2). As a result, we witnessed a shift in the last two years of analysis towards ‘sustainable mobility’’ issues, while biodiversity is included as a side effect, as the prominence of the ‘greening elements as added value’ concept demonstrates (Fig. 6, top-right). This is also visible in the limited number of newspaper articles retrieved for 2024. This might explain the delay in implementing the UGP postponed to the end of 2024, as shown by the relative centrality of the ‘reference to a plan’ concept. However, in the last months of analysis, the debate started to be populated by many different actors, which reveals a new understanding of the complexity of urban biodiversity and the willingness to change trajectories.

The figure depicts one-mode networks for the year with the highest frequency of nodes (left) and one-mode networks for the last 12 months of analysis (right) for Florence. Only the top ten frequent nodes are visualised. The size of the nodes represents the frequency (number of times the concept or organisation appear in the articles in the respective time). The strength of the links is bigger according to the edge weight (number of concepts the actors share with each other or the number of actors that mention the same concepts in the respective time). The organisations are citizens (cyan), economy (yellow), grassroots initiative (green), NGO (red), politician (light blue), public administration (blue), public-sector economy (light green), and science and education (pink) (Supplementary Note 3).

Imagining future urban biodiversity

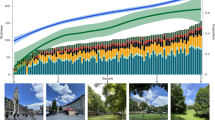

Following the definition of urban climate imaginaries as “collective discourses surrounding the urban that reflect the aspirations of future […] imaginaries, which are created in narratives and reproduced in policy documents” (p. 80 ref. 12), this section investigates how urban actors’ imagination of urban biodiversity materialises into urban biodiversity-based imaginaries, merging data from the UGPs (Fig. 7), spatial analysis (Fig. 8), and expert interviews.

This figure shows to which extent the UGPs analysed for each city comply with the UGP guidance draughted at the EU level. The flags represent the six milestones described in the guidelines: the dotted lines denote an absence of the milestone; normal lines indicate that the milestone is partially present; filled areas signify a complete presence of the milestone. Florence performs worst because we refer here to the political programme and not to the UGP, which was not published when writing this paper.

This figure shows the spatialisation of the public debate in Heidelberg and Hanover (top) and Cesena and Florence (bottom). The marked areas are the projects mentioned in the newspaper articles we analysed; the black dots show the number of articles where a project is mentioned. The areas in green correspond to the projects exclusively supported by the urban actors, while the red ones are characterised by various degrees of conflict (authors).

At the local level, Heidelberg has had a Biodiversity Strategy since 2021. This strategy includes the results from the Urban NBS project (2015–2019) to define strategies and approaches for urban biodiversity with the participation of different public actors and NGOs38. The Heidelberg biodiversity strategy aims to make the best use of available resources by identifying key areas for action for the species and habitats in and around Heidelberg and prioritising the actions needed to promote and protect biodiversity. The second cornerstone of the strategy refers to the proper integration of urban greening in urban planning and the support of biodiversity in the inner-city areas (ibid., p. 33). The biodiversity strategy is comprehensive and ambitious. It includes a detailed analysis of the status quo of flora and fauna, a relatively detailed action and time plan for the foreseen measures, and an indication of a communication strategy about the measures and the respective monitoring. Interestingly, this UGP does not entail a proper vision. Additionally, there is no mention of a participatory approach in draughting such a plan (Fig. 7). This could be a symptom of a rather silo situation, as discussed previously in the understanding and communicating sections. From our investigation in the spatial analysis (Fig. 8), we find that the main areas in the public discourse are on both sides of the river Neckar, a few places in the old city and other places more in the periphery of the city. When we visited these sites, we were left with the impression that they are not always green spaces that are convincing from a biodiversity point of view. For example, this is the case of the ‘SRH Uni Campus’’ and ‘Der Andere Park’’, where the natural elements are presented more in terms of aesthetics and human health rather than providing benefits for biodiversity. One interviewee from an environmental NGO (HE_1) explained that the biodiversity strategy focuses more on the agricultural spaces outside the city. Another interviewee, a leading manager of the landscape office (HE_2), referred to “Oasis”, an idea that had been put forward by the mayor of Paris at some point and had been imported to Heidelberg by the mayor of Heidelberg. This idea translates into plans that envision implementing greenery in places that are not necessarily suitable for parks, especially obsolete traffic areas, school playgrounds or all kinds of areas that can contribute to a bioclimatic improvement in the city centre. The interviewee further explained that the most ecologically sensible way to create living space is through re-densification, limiting green spaces in the city and reducing fresh air corridors (HE_2). According to this conflict, “multifunctionality” would be the key term, meaning that different aspects must be considered. The city can no longer afford to use public space un-ecologically; this starts with selecting plant varieties that must be considered for biodiversity.

In December 2020, the municipality of Hanover draughted the concept for open spaces Stadtgrün 2030. It represents the result of the participatory process Mein Hannover 2030 to “keep Hanover as green as it is” (p. 4 ref. 31). Urban greening and biodiversity measures are fundamental to addressing climate change and protecting nature in the urban context (ibid., pp. 12–14), giving importance to nature-experiencing activities, education, and biodiversity. The plan is complete compared to the other cities: it presents a clear long-term vision divided into specific goals, it provides a thorough analysis of the status quo of ecosystems and proposes a detailed action plan for the next years to implement the measures (Fig. 7). Additionally, the plan offers a comprehensive framework that connects the UGP to various local and regional plans and regulations, highlighting the holistic feature of this plan and the willingness to consider different levels of action. One interviewee in a leading position (HA_1) of the urban greenery department explained that this document is the conceptual basis for further landscaping measures, i.e. the redesign and redevelopment of green links, green corridors, and town squares. The interviewee also explained that the Department of Urban Greenery is well-staffed. The person interviewed further pointed out a great appreciation among the population for urban greenery and a corresponding awareness of local politics that urban greenery has a high value. The interviewee also highlights Hanover’s success due to ‘Eilenriede’’, one of the largest city forests in Europe, offering numerous recreational activities, and ‘Maschsee’’, an artificial lake south of the city centre (Fig. 8). These two projects are fundamental parts of the green corridor strategic approach of the landscape plan at the metropolitan level. The relatively low ratio of conflictual projects and their good distribution in the municipal area demonstrated the success of the communication aspect in Hanover, as described in the previous section. Another interviewee from the insect alliance (HA_2) referred to the conflict between creating urban housing due to rising individual people’s demand and biodiversity and urban greening. Accordingly, housing issues are often the stronger ones in this conflict. However, the interviewees (HA_1, HA_2; HA_3) stated that the capacity of the urban greenery department is large enough to continue expanding future green spaces and maintaining and caring for existing ones. We can conclude here that the well-staffed urban greenery department, sufficient financial resources, and strong community support will ensure that the city’s green spaces and biodiversity are maintained and enhanced in the future.

With the Green City Accord subscription, Cesena became one of the first small cities in Italy to show commitment towards urban biodiversity. Based on the five spheres of action of the Green City Accord, the Objectives and Strategies for a Greener Cesena planning document was draughted in July 2023. This document was developed with the support of the CpA, relying on extensive participation. The UGP does refer to the EU regulations and to the Green City Accord but does not link to other levels of governance (Fig. 7). However, it represents a first attempt to holistically formulate precise targets for future orientation not only to urban biodiversity projects but also to air, quarter, waste management, and noise, demonstrating a holistic approach to the management of urban futures. Concerning the biodiversity sphere of action, this document contains targets by 2030 “to encourage the establishment of nature in the city” (translation by authors, p. 15 ref. 39). The UGP of Cesena has the form of a strategic document with an inventory of the existing natural species (although limited), while the action plan is sketched without the indication of a time horizon. The interviewees from the public administration pointed out that realising a UGP as defined by the EU guidance40 would require more time, budget, and expertise (CE_1a). Building the inventory already consumed considerable resources as data acquisition is still onerous. At the same time, the analysed document includes important details that go beyond a general strategic document as it aims to differentiate types of green spaces precisely: doing that would allow for planning different levels of maintenance, from the playground to the urban forest and allocate resources accordingly (CE_1a; CE_1b). Looking at the projects debated in the newspaper articles, these are situated largely outside the city centre (Fig. 8). These interventions consist of rather large areas that address biodiversity with diverse objectives: some projects are thought for educative purposes or leisure (e.g., ‘Savio river’’), while others are purposefully for enhancing biodiversity (e.g., ‘Polmone verde’’). Most conflictual projects are the most recent ones, close to the centre, and circumscribed to specific small areas or buildings. The reasons can be mainly adduced to the decreased participation visible during the period analysed (Fig. 5). Thus, engaging various urban actors and citizens more comprehensively in implementing the strategy is an important future step. Following a narrative that sees urban biodiversity to be curated as a child (CE_2), future efforts should invest in raising awareness and a sense of ownership towards the public spaces and nature they host, which is reflected in the vision proposed by the UGP analysed. The inventory is, therefore, only the first step, but preparing a real planning effort in the future is necessary to benefit from the information acquired (CE_1a; CE_1b).

The programme The City We Are, The City We Will Be represents the most up-to-date political statement on Florence’s commitments to urban biodiversity. Urban biodiversity projects are presented for future projects and existing areas, from implementing new green elements (the air factories) to requalifying historical ones41. The programme is divided into a more strategic part with general goals and an action plan that specifies such goals (Fig. 7). Because of its status as a political programme, this document does not provide an adequate picture of the status quo and does not include a time plan for the implementation of the measures it proposes. This programme does not result from a participation process but clearly states the willingness to involve citizens more extensively in the future. In 2023, the draft of the UGP was announced and is expected to be ready by the end of 2024. The interviewees refer to a draughting process involving an ample range of urban actors, from landscape architects to medical doctors, with the vision of realising a holistic plan for the open spaces where public and private spaces are equally considered (FI_1; FI_2). In the fieldwork, it was noticed that in the historical centre, the few visible green elements are installed in private businesses, in pots as a traffic management device, and on private balconies or terraces (Supplementary Fig. 19). The UGP inventory was filled with an extended deployment of digital and human resources to identify all these elements. As the expert interviews state, data are paramount in correctly identifying the planning of measures and their consequent implementation. The spatialisation of the public debate shows a rather diverse set of projects equally distributed between outside and inside the urban centre (Fig. 8). Notably, compared to Cesena, Florence presents more conflictual projects, some located in the central part of the municipal territory (‘‘Urban centre’’, ‘Viale Redi and Viale Corsica’’). Like Cesena, most conflicts are polarised around misinterpreting public administration actions, but in Florence, those are actively supported by political parties (Fig. 6). According to the interviewees, the reasons are attributed to the conservatism (FI_1) or the lack of interest of certain actors (FI_2). Although stated in the programme, the engagement of citizens is envisioned in classical terms as a consultation period after the UGP draughting (FI_1). A representative from the economic sector stated that public administration actors are advanced in understanding the importance of urban biodiversity, but citizens still cannot deal with such complexity (FI_3). The necessity of sensitising citizens to prevent a priori blockade and reduce mistrust towards the institutions is a future step to improve urban biodiversity in Florence (FI_2).

Discussion

The results above present how urban actors understand, communicate and imagine future urban biodiversity (for a summary, see Supplementary Fig. 20). Combining the three dimensions, we aim to shed light on how urban biodiversity-based imaginaries are debated in small and large cities and which influences these imaginaries have on the urban environment.

By looking at how urban actors understand the “nature around them” (p. 14 ref. 25), we have confirmed through the analysis of the UGPs and the interviews the existence of various definitions of urban biodiversity, ranging from practical examples (solutionism) to broader concepts of ecological networks (ecosystem) and elements of urban transformation (planning tool). Notably, the interviewees all confirmed a generally increase in the sensitivity towards urban biodiversity topics (HE_3; HA_3; CE_2; FI_2; FI_3). However, especially in the case of Heidelberg, the interviewees agree on a generally low political commitment towards such topics (HE_1a and HE_1b; HE_2), which results in urban biodiversity being outclassed by other issues26. This is due to various influences from the EU level through the EU-BDS, for example, or concerning natural disasters, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The national and regional levels proved to be positively influential in the two German cases, while in Italy, these remain distant or are perceived as obstacles. The European and national are also mentioned for their funding programmes. The federal level is a reference point for planning directions in the two German cities, while the regional level in Italy was regarded in the interviews as non-supportive. If the document analysis and the interviews revealed the presence of funding schemes at the federal and regional levels, a lack of other types of support is reported in the Italian cases, such as expertise and further directions in planning urban biodiversity. As actual planning documents struggle to handle the future uncertainty and complexity of urban biodiversity4, incremental urbanism and similar approaches might provide a solution42. Nevertheless, city administrations often lack the resources and expertise to invest in such complex processes, especially in smaller cities. Hanover, the biggest city in the sample, does not share these concerns. In this respect, Cesena shows how urban green spaces can be defined according to different degrees of naturality, leading to a more accurate allocation of maintenance resources (HE_1; CE_1b; FI_3). This seems fundamental in the absence of local public procurements and recent public budget cuts, as witnessed in Heidelberg, and in the light of a weak contribution of the regional level in Italy (HE_2). Last, if urban actors understand the importance of urban biodiversity, it is the opinion of the interviewees that work must be done to sensitise citizens. Because urban biodiversity-related measures do not yield immediate or observable results, as nature requires time for growth, the interviewees suggest the public administration should raise awareness of these aspects among citizens (HE_2; HA_3; CE_2; FI_3).

Second, we have identified different debate patterns in the public discourse about urban biodiversity in the four cities to infer how urban actors communicate urban biodiversity. Generally, we have observed a tendency towards mainly process-related concepts in Italy (e.g., ‘participation’’ and ‘cross-collaboration’’). Conversely, the debate is dominated by more substance-oriented concepts in German cities (e.g., ‘urban greening for biodiversity’’ and ‘climate change’’). The public administration plays a prominent role in fundamentally enabling the debate on urban biodiversity and fostering its implementation. Two reasons can be identified as contributing to this outcome. First, such interventions are implemented on public land. Second, the public administration represents the municipal planning interest. This suggests the potential to prioritise urban biodiversity in the political agenda43, which is reflected in the discourses analysed (Figs. 3–6). Following 2022, the public debate becomes highly diversified with the participation of other types of actors. This demonstrates an increasing awareness of the complexity of addressing urban biodiversity projects, with significant implications for practical implementation15. However, the interviews and spatial analysis reveal further challenges. At the organisational level, the public administration still suffers from the silo effect: this is observable in Florence from the DNA results, and it was mentioned by the interviews for Heidelberg (HE_1a; HE_1b). Urban biodiversity usually loses against more pressing issues such as housing (Heidelberg) and mobility (Florence): these topics are more accessible for all urban actors, especially citizens. Additionally, discourses on historical heritage preservation of buildings and gardens hinder maintenance and requalification in Hanover and Florence. On the measure level, implementing mitigation or adaptation measures is sometimes a polarising issue, especially in Heidelberg and Florence. The tendency to understand urban biodiversity as fundamentally an adaptation measure leads to implementing green elements as a side effect (‘‘green as added value’’), whereby the focus lies on the building or the infrastructure. Concerning participation, we have identified the difficulties in engaging citizens. DNA revealed various conflictual reactions from citizens ascribable to typical NIMBY situations. This is mainly due to a top-down and siloed communication style, such as in Heidelberg (HE_2) and Florence (FI_1), and a lower awareness of these topics among the population in Cesena (CE_2). With the insect alliance, Hanover anticipates these hindrances through intense communication and diffusion of knowledge (HA_2; HA_3). However, conflictual situations can result in beneficial discussions: the CpA in Cesena is a good example of a local initiative directly engaging citizens in defining plans and future interventions (CE_2).

Lastly, understanding and communicating urban biodiversity translates into urban biodiversity-based imaginaries built on diverse narratives of the future through which urban actors imagine future urban biodiversity. The UGPs analysed present various degrees of obligations and foci on urban biodiversity, but most remain at the strategic document level without fixing clear responsibilities. As other studies confirmed44, these documents do not manage to fulfil the ambitious design of a UGP as per the EU-BDS. Smaller cities do not possess enough economic and human resources to engage in a real plan. In comparison, bigger cities struggle with integrating these UGPs into the overall planning framework and with the pressure of implementing urgent actions. These challenges could be attributed to the intrinsic indefinability of nature when producing such imaginaries, whereby “the term “green” is currently in danger of becoming inconsequential in everyday language” (p. 2 ref. 45). In such narratives, the concept of urban biodiversity is usually idealised, for which no conflicts and uncertainties are foreseen46. Thus, working with such a complex concept would require an effective communication strategy to show an alternative understanding of urban biodiversity that promotes conversations and allows conflictual situations rather than refusing them. This step is often overlooked due to the pressure cities face to urgently deliver tangible results in an era when time is no longer an available resource (FI_1)42. Urban actors in Heidelberg deploy mainly top-down communication (HE_2), while Florence is willing to share the plans with its citizens only after completion (FI_1). Similarly, although Hanover strongly focuses on communication, institutionalised participatory processes are not envisioned for the urban biodiversity or greening plans, but the process is open for citizens to provide new ideas (HA_1). Finally, the UGPs analysed vary considerably in their proposed measures, from general considerations to specific actions. Generally, the ‘promoted’ biodiversity-related projects in Fig. 8 are well-distributed among the municipal territory and have important spatial extensions, whereas the ‘conflictual’ projects are mainly in the centre and regard small areas (Supplementary Figs. 15–18). This is unsurprising, as having a completely natural element within the urban centres is worsened by density and land use conflicts (HE_1; FI_3). The fieldwork revealed a general tendency to prefer relatively curated forms of urban greening with few attempts to improve and manage biodiversity in these areas (Supplementary Fig. 19). This was also confirmed in the interviews, especially for Heidelberg, where, although the documents depict a virtuous case, the dynamics between the different urban actors involved in the strategy draft and its implementation correspond to a few interventions dealing with urban biodiversity in the inner city.

We are aware that the selection of the four cities represents a biased sample to a certain extent. These committed cities are used to a specific vocabulary and set of practices, which we could define as a ‘discursive bubble’’. The selection was guided by the need to ensure the presence of data to work on, answering essentially methodological questions. Additionally, the selected cities share similar political orientations concerning their government constellation. Further research could compare cities within and outside this bubble to specifically look at how the discourse changes. This could show whether discussing urban greening and biodiversity is an elitist debate for most privileged cities only. The newspaper articles analysed tend to report the voices of specific actors, mainly affiliated with the public administration, which could falsify our conclusions on which actors are driving the debate on urban biodiversity. We have observed that media are seen with diffidence by many urban actors and are often misused; however, media could play a greater role in communication with the broader public. Additionally, the representations of the debates for the four cities are limited to the top concepts and organisations for simplicity. Unavoidably, this choice results in a partial view of the cases. However, the methods deployed in this explorative research complement each other to grasp the complexity of urban biodiversity-based imaginaries. Despite the difficulties in merging different scientific traditions, we suggest expanding future research in urban biodiversity by exploring the intersections between different disciplines and methods.

We are witnessing a cultural turn through which the dependency of human-made systems on ecological ones is becoming always more evident. The newly generated urban biodiversity-based imaginaries contain the promise to bring alternative ways of thinking into everyday planning to pursue the transformative change we crave4. On this line of thought, we have argued that the construction of urban biodiversity-based imaginaries should be analysed at the intersection between different understandings in the past, communication strategies in the present, and future narratives generated by urban actors. We have investigated cities of diverse sizes in two European countries with the same policy framework but inherent cultural, political and geographical differences. As argued above, we can state that the construction of urban biodiversity-based imaginaries has less to do with sizes and geographies but rather is dependent on urban actors and cultural dynamics. The understanding of urban biodiversity from different actors is vague and unclear, opening a too broad range of possibilities under which everything can be understood as such14,45. It is foremost a concept that suffers from an excessive level of scientific complexity and abstraction. While some urban actors can exploit vagueness to justify desirable urgent actions, an abstract idea is not appealing enough to convince others about its necessity13,20. This would eventually lead to abandoning those imaginaries for which it is difficult to create a convincing storyline. In this sense, good data collection and monitoring are necessary to support evidence-based decisions about the future. Thus, urban actors should plan for such investments, as these weigh considerably on the municipal budget, not only in economic terms: while the UGPs provide a credible and desirable vision of a biodiversity-based future, they lack a proper discussion on “how to bring the plans on the ground” (CE_1a). The regional level should be more active in supporting local public administration with more expertise, data provision, and transparency in communication rather than limited to funding schemes. Thus, good communication and awareness-raising strategies coupled with a robust data-driven vision remain important to including laypersons5 to reduce the knowledge gap on urban biodiversity and mistrust towards institutions. This also means going beyond the current understanding of participatory processes based mainly on consensus and embracing conflicts4. It is advisable to create a body that mediates between the public administration and the citizens to engage them in the planning process, improve communication, and spread enthusiasm among urban actors (HA_3). In this sense, some of the interviewees call for a more active engagement of the public administration in allowing for shared decisions and spreading culture towards urban biodiversity. As Haarstad nicely hints, instead of being kept in the spiral of innovation and solutionism, urban actors should rather formulate reimaginaries where past, present, and future dialogue, thus avoiding the engagement with new branded concepts and addressing more fundamental cultural gaps (p. 186 ref. 47). This novel approach to urban planning, which prioritises and communicates the fostering of biodiversity, should result from a comprehensive strategy that acknowledges the intrinsic value of nature and its role in climate change adaptation and mitigation as well as biodiversity conservation. Rather than focusing on isolated policy areas, a more holistic approach (multifunctionality) is essential to develop a coherent plan for open urban spaces.

Methods

Case study selection procedure

The case study selection is meant to acquire a manageable set of committed cities concerning urban biodiversity planning and implementation in Europe (Supplementary Note 2). Different databases were consulted following recent studies concerning European municipalities and their commitment to defining policies for climate neutrality48,49. Successively, committed cities have been catalogued according to their participation in an EU-funded project from the Cordis Database, focusing on urban greening and biodiversity actions. Cities with a population below 20,000 were discarded per the EU-BDS. Germany and Italy present the highest number of cities that follow the criteria from these databases. Both economically prosperous countries and influential in the world scenario as members of the G7, Germany and Italy represent an interesting lens that exemplifies the northern and southern socio-political situations in Europe50. In both countries, the state has delegated municipalities the responsibility of planning to address climate change locally51. Germany and Italy present similar polycentric configurations of urban centres with a high ratio of small- to large-sized municipalities, thus functioning as potential examples to analyse policy responses towards climate change in Europe. We refer to the categorisation of city sizes as in the study of (p. 4 ref. 49). Four cities were considered reasonable to have a certain degree of variability while being able to analyse the cases with enough depth52. Cities with particular statuses (such as capital cities or city-states) were discarded a priori and considered too special. The final selection was made according to the concept of matching cities that identified the pairs53 considering the number of inhabitants, the political orientation of the public administration, the presence and the year of draughting the strategy or plan for urban biodiversity (see Fig. 2).

Policy document analysis

To identify the relevant documents at the regional and local levels that provide the contextual framework for the UGP draughting, we searched for ‘biodiversity’ + ‘strategy OR plan’ + ‘name of the region/city’. Most of the documents were not easily retrieved from a simple Google search but had to be looked for on the respective websites of the responsible institutions. It is important to note that navigating through the institution’s website was rather arduous. Some relevant documents were found only after reading the UGP, which reports on integration with other policy documents or were mentioned by the interviewees.

The UGPs were retrieved directly from the official websites of the four cities. Specifically, we have looked at the respective urban greening and biodiversity planning departments for the most updated plan or strategy. Once the UGPs were found, we thoroughly analysed these documents based on the elements a UGP should have according to the most up-to-date guidance40. We posed the following questions about the six milestones (MS): Was the plan designed based on a participatory process (MS1)? What urban imaginary does the plan or strategy propose, and how is urban biodiversity defined (MS2)? Is the strategy or plan mainly considering green areas, or does it contain references to biodiversity specifically, such as plants and animal species (MS3)? What goals are listed, and how are these prioritised and categorised in space and time (MS4)? Is there a communication strategy for the planned targets and interventions (MS5)? Is a monitoring strategy considered to report on the interventions’ development and performance (MS6)? The results are presented in Fig. 7.

Discourse network analysis

The newspaper articles were searched in four local newspapers, namely ‘Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung’ for Heidelberg, ‘Hanoversche Allgemeine Zeitung’ for Hanover, ‘CesenaToday’ for Cesena, and ‘FerenzeToday’ for Florence. The use of local newspapers is a proven, accessible and reliable source, available online daily54. A possibly high circulation rate and press quality criteria must be considered when selecting the local newspaper. For the data collection, a period was chosen to search with specific keywords for the thematic articles. The EU Green Deal was draughted at the end of 2019, followed by the EU BDS 2030 in May 2020. Therefore, the year 2020 was chosen as a turning point in the EU context when talking about biodiversity was officially embraced by European institutions and policies. At the end of June 2024, the EU Nature Restoration Law was adopted by the European Parliament, making the draughting of a UGP obligatory. Thus, the period between January 2020 and June 2024 was chosen for the analysis as a transition phase of what we could define as ‘the voluntary discourse on urban biodiversity’ in the political debates in European cities.

For the German case studies, the keywords searched are “biodiversity” (Biodiversität) OR “urban greening” (Stadtgrün). For the Italian case studies, the search on the websites of the two newspapers was limited to “urban greening” (verde urbano) because of the difficulties in using Boolean strings. Having the same starting point allows us to deepen the specificities and analyse anomalies of the case studies. To code the newspaper articles, we created a codebook containing different deductively created categories; further categories are inductively added during the coding process. The categories are both general cross-case and case-specific categories. To manually code the newspaper articles, we used the software discourse network analyser (https://www.philipleifeld.com/software/software.html). In the coding process, four dimensions for each statement were categorised: 1) name of the actor, 2) affiliation of the actor, 3) concept, which is a general category of a statement, and 4) agreement or disagreement with this category. The newspaper articles were coded in the discourse network analyser (DNA) software version 3.0.10. Statements of actors in direct or indirect speech were coded with information on the actor, the organisations the actor is affiliated to, the concept, and agreement or disagreement on the concept. We analysed 327 newspaper articles in this period and coded 1465 statements organised into 35 concepts. The actors were divided into eight organisational types: public-sector economy, science and education, grassroots initiative, NGO, politician, government, economy and citizen.

The data coded in the dna software was successively analysed and visualised in the visone software version 2.2855. We built one-mode discourse networks for each city annually from January 2020 until June 2024. One-mode actor networks represent actors’ networks connected by sharing concepts, and one-mode concept networks show concepts connected by actors sharing the respective concepts. We used the subtract function, which shows the congruence subtracted by the discrepancy between the nodes56. The position of the nodes is based on their degree of centrality; the size of the nodes represents the frequency of appearance in the respective newspaper articles, while the thickness of the ties is based on the edge weight, representing the number of times the actors mention these two nodes. For better visualisation, we use a threshold of the networks, and only the nodes with the ten highest degrees of centrality were selected for representation. Detailed information on organisations, concepts, and the complete yearly DNA is available in Supplementary Note 3. Supplementary Note 8 provides an overview of the organisations in their original language alongside the English translations used.

Spatial analysis

The spatial analysis was performed by identifying the geolocation of the projects mentioned in the newspaper articles. The maps in Fig. 8 show what we call spatialisation of the discourse. The portraited projects do not represent exhaustive inventories of all biodiversity-related areas in the four cities. Rather, they mirror the importance of projects that deserve to be advertised by the discussant (called ‘promoted’’) or are objects of conflictual situations (called ‘conflictual’’). For more precise information about each project, see Supplementary Note 4. The authors conducted fieldwork to visit most of the identified projects and support the bi-dimensionality of the maps with real-world pictures (Supplementary Note 5).

Interviews

At least three interviews per city were conducted following a semi-structured questionnaire (Supplementary Note 5). The main scope of the interviews was to validate the findings collected through the other methods described above. The main actors mentioned in the newspaper articles were chosen as interviewees and thus are involved to some extent in the projects considered in the analysis. Through snowballing, other relevant interviewees were identified. The complete list of interviewees and further information are reported in Supplementary Table 5. The interviewees in each city belong to different types of organisations to grasp the impression of the context from various perspectives and include a broad spectrum of urban actors. The questions posed referred to 1) the personal definition of urban greening, 2) their role in the process of the plan or strategy development, 3) their impression of the public debate on urban biodiversity, 4) their ideas of the future work to be done concerning urban greening, and 5) the enquiry for further contacts. All interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min and were conducted in person, during the fieldwork, or via Zoom. All of them were recorded and transcribed. The coding was organised into five macro-categories: the definition of urban biodiversity, the process of planning document draughting, the sensitivity of public opinion, future perspectives and challenges.

Data availability

Supplementary information file is publicly available and can be accessed at the HafenCity Universität Hamburg repository at the following link: urn:nbn:de:gbv:1373-repos-14424.

Change history

23 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00269-8

References

Sukopp, H. On the early history of urban ecology in Europe. Preslia, 74, 79–97 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73412-5_6 (2002).

McDonnell, M. J. The history of urban ecology. An ecologist’s perspective. (edited by Niemelä, J.) In Urban Ecology. Patterns, Processes, and Applications (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Ibsen, P., Kucera, D., Piper, S. & Jenerette, G. D. Urban Climate and the Biophysical Environment (edited by Nilon C. H. & Aronson M. F.) In Routledge Handbook of Urban Biodiversity (Routledge, 2023).

Bulkeley, H. et al. Cities and the transformation of biodiversity governance (edited by Visseren-Hamakers I. J. & Kok M. T. J.) In Transforming Biodiversity Governance 144, 293–312 (2022).

Nilon, C. H. et al. Planning for the future of urban biodiversity: a global review of city-scale initiatives. BioScience 67, 332–342 (2017).

EC. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing nature back into our lives (Europeon Union, 2020).

Wilk, B., Schauser, I. & Vetter, A. Tackling the climate and biodiversity crises in Europe through Urban Greening Plans. Recommendations for avoiding the implementation gap. (ICLEI Europe, 2021).

EC. Urban Nature Platform. Available at https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/urban-environment/urban-nature-platform_en (European Comission, 2022).

Hodson, M., Evans, J. & Schliwa, G. Conditioning experimentation: the struggle for place-based discretion in shaping urban infrastructures. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 36, 1480–1498 (2018).

Haarstad, H., Grandin, J., Krzyżak, J. & Johnson, E. Why the haste? Introduction to the slow politics of climate urgency (Haarstad H., Grandin J., Kjærås K. & Johnson E. Haste) In The Slow Politics of Climate Urgency (UCL Press, 2023).

Holgersen, S. The geography of the ‘world’s greenest cities’: a class- based critique. In Haste. The Slow Politics of Climate Urgency (UCL Press, 2023).

Westman, L. & Castán Broto, V. Urban Climate Imaginaries and Climate Urbanism (edited by Castán Broto V., Robin E. & While A.) In Climate Urbanism (Springer Int. Publishing, 2020).

Beckert, J. What makes an imagined future credible? MPIfG Discussion Paper 24/5 (2024).

Brown, N., Rappert, B. & Webster, A. Contested futures. A Sociology of Prospective Techno-Science (Ashgate, 2000).

Hajer, M. A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse. Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process (Clarendon, 1995).

Hajer, M. A. Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice (edited by Fischer F. & Forester J.) In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (Duke Univ. Press, 1993).

Fischer, F. & Forester, J. (eds.). The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (Duke Univ. Press, 1993).

Müller, N., Werner, P. & Kelcey, J. G. Front matter (edited by Müller N., Werner P. & Kelcey J. G.) In Urban Biodiversity and Design (Wiley, 2010).

Nilon, C. H. & Aronson, M. F. (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Urban Biodiversity (Routledge, 2023).

Jasanoff, S. Future imperfect: science, technology, and the imaginations of modernity (edited by Jasanoff S. & Kim S.-H.) In Dreamscapes of modernity. Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power (The Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, 2015)

EU & UN-Habitat (eds.). The state of European cities 2016. Cities leading the way to a better future (European Commission, 2016).

Hajer, M. A. & Versteeg, W. A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. J. Environ. Policy Plan.7, 175–184 (2005).

Leifeld, P. Discourse Network Analysis: Policy Debates as Dynamic Networks. (edited by Victor J. N., Montgomery A. H. & Lubell M.) In The Oxford Handbook Of Political Networks (Oxford University Press, 2017)

Nagel, M. & Bravo-Laguna, C. Analyzing multi-level governance dynamics from a discourse network perspective: the debate over air pollution regulation in Germany. Environ. Sci.34, 62–80 (2022).

Nilon, C. H. History of Urban Biodiversity Research and Practice. (edited by Nilon C. H. & Aronson M. F.) In Routledge Handbook of Urban Biodiversity (Routledge, 2023).

Arlati, A. National parliamentary discourses on urban greening and biodiversity implementation in Germany and Italy. In Conflicts in Urban Future-Making. Governance, Institutions, and Transformative Change, edited by Grubbauer M., Manganelli A. & Volont L. (Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, 2024).

Bundesland Baden-Württemberg. Naturschutzstrategie Baden-Württemberg. Biologische Vielfalt und naturverträgliches Wirtschaften – für die Zukunft unseres Landes. Ministerium für Ländlichen Raum und Verbraucherschutz, February 2014.

Bundesland Baden-Württemberg. Biodiversitätsstärkungsgesetz. Stärkung der biologischen Vielfalt. Ministerium für Umwelt, Klima und Energiewirtschaft Baden-Württenberg, 28.11 (2023).

Bundesland Niedersachsen. Niedersächsische Naturschutzstrategie. Ziele, Strategien und prioritäre Aufgaben des Landes Niedersachsen im Naturschutz. Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Umwelt, Energie und Klimaschutz, May 2017.

Region Hannover. Regionales Raumordnungsprogramm Region Hannover 2016, (2016).

Landeshauptstadt Hannover. STADTGRÜN 2030. Ein Freiraumentwicklungskonzept für Hannover, December 2020.

Regione Emilia-Romagna. Strategia di mitigazione e adattamento per i cambiamenti climatici della Regione Emilia Romagna (2019).

Regione Emilia-Romagna. Regional strategy “20230 agenda for sustainable development”. Emilia-Romagna. Il futuro lo facciamo insieme (2021).

Comune di Cesena. PAESC Cesena. Piano d’azione per l’energia sostenibile e il clima (2019).