Abstract

Local governments are at the forefront of climate action. Responsible for regulating land use and development, they influence greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilience. There is limited research exploring integration and mainstreaming of adaptation and mitigation actions across whole built environment policy portfolios, or comparing local government contexts, e.g., urban vs rural. We developed an approach to assess integration of adaptation and mitigation actions across policy portfolios and applied it to policy portfolios of three diverse local government areas in Victoria, Australia: the City of Melbourne, the City of Greater Geelong, and the Wellington Shire Council. We find that while climate change adaptation and mitigation actions are integrated, they are not mainstreamed into the built environment policy instrument portfolios. Wellington, a rural local government, has half the number of policy instruments of the others investigated, resulting in fewer climate actions across its policy portfolio. These scalar challenges should be addressed in climate planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions rose 12% during the period 2010–20191, despite international commitments to limit warming to 1.5 °C through the Paris Agreement2. International policy commitments have been assessed to be inadequate to meet the Paris Agreement targets, with a significant gap between ambition and reality3. Emissions scenarios indicate that if the current policy commitments do not change, we should anticipate global warming to reach 3.2 °C above pre-industrial levels by 21001. Additionally, there is a gap between the actions being taken to adapt to climate change, and what is needed4. This lack of adequate action will have significant impacts for humans and the natural environment5,6. Concerted effort is now needed to ensure deep and steep emissions reductions are achieved across all sectors, to keep the Paris Agreement goals alive, and thus reduce the impacts and harm to the environment and populations that will occur with every increase in warming7. Work must also be undertaken to adapt to the impacts of climate change that have not been avoided due to current and historical GHG emissions and if the global goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C is not achieved (as per the current trajectory). Action is needed across all sectors of society, we need to do “everything, everywhere, all at once”8.

Despite this urgency, climate change action has not reached its full potential across a number of sectors. In particular, the built environment, which is the source of 67–72% of total GHG emissions [1 p.12], has great potential to move from status quo, to reduce emissions. Hence, in built environments, climate change transformation is necessary: the integration of adaptation and mitigation actions with the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C and being well adapted to that new regime9. We risk ‘malaction’, if we don’t reduce emissions sufficiently to achieve the 1.5 °C goal, or if our adaptation actions are not adequate for the impacts that result9. This situation could arise through inadequate acknowledgment of the extent of warming that is likely to occur, or for not mitigating sufficiently9.

Local governments are at the forefront of climate change action. In many countries, local governments are responsible for managing the use and development of land, which can have significant implications for greenhouse gas emissions and resilience to climate change risks. There is a growing body of research that explores the quality of local governments’ climate change-focussed plans and whether they are integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation goals. In the first IPCC chapter to explicitly address the relationship between adaptation and mitigation, Klein et al.10 discuss that in order to reduce the risks of climate change, it will be important for policies to have a portfolio of diverse adaptation and mitigation actions. They also recognised that it is important that climate change action extends beyond climate change plans, to policies that effect the way in which land is developed and used10. Despite this articulated importance, there has been limited research to explore the integration of adaptation and mitigation actions in local governments’ built environment policy portfolios, i.e., the group of diverse decision-making instruments (legislation, regulations, strategies, guidelines voluntary instruments and programmes) that is influential in determining the form and function of the built environment11. Definitions of key terms used in this paper can be found in Box 1.

In addressing climate change, there are two key categories of action that must be undertaken: mitigation and adaptation (see Box 1). Through the Paris Agreement, the international community has agreed to achieve zero net emissions by 2050, which has been assessed to facilitate limiting warming to 1.5 °C, and thus reduce the risk of harm from climate change impacts6. Adaptation requires locally relevant information about the likely impacts of climate change-exacerbated natural phenomena such as heat waves, wildfire, extreme rainfall events, and sea level rise. There is a significant and growing body of literature that explores the value of and types of such actions. For example, in the IPCC’s sixth assessment Working Group III report, a chapter on Urban Systems and Other Settlements12 focusses on mitigation actions. Additionally, in the Working Group II report, a chapter on Cities, Settlements and Key Infrastructure13 addressed adaptation actions. We summarise these in Table 1 combined with other literature.

In policy development, it has been typical practice to consider climate change mitigation and adaptation actions separately10,14. Howarth and Robinson14 believe this has occurred for a number of reasons, including the prioritisation of mitigation in international governance; national climate change action lacking coherence in many contexts; different priorities that countries have depending on their individual context; and that adaptation and mitigation policy instruments and mechanisms differ. The lack of an integrated approach could lead to poor progress toward effective climate action and development14. It could also potentially lead to a range of unintended consequences, including maladaptation14.

Increasingly, literature recognises the interrelationships between actions to address climate change as neutral, positive (synergies or ‘win-wins’) or negative (trade-offs)15,16. For example, even when the main purpose of an action is mitigative, it can have adaptation co-benefits, and, therefore, positive interrelationships. Likewise, an action can have negative outcomes for other policy goals, including climate change-related goals. For example, an adaptation action (e.g., installing an air conditioner for thermal comfort during heat waves), if run on non-renewable energy resources, is maladaptive9 and will actually contribute to further climate change. Recognising this, in organising the content of Table 1, we arrange climate change actions into three broad groups: those with the primary purposes of (1) mitigation, (2) adaptation, and (3) those with a prima facie co-benefit.

An integrated approach to adaptation and mitigation action has developed apace since the Paris Agreement. It emphasises the benefits of mitigation and adaptation being integrated within systems9, including with actions to achieve sustainable development2. Despite this emphasis, there has been limited guidance on how to achieve integration in practice. To fill this gap, there has been an increasing body of research conducted to explore how to successfully integrate climate change mitigation and adaptation actions. This has included approaches to institutionalising the two through adaptigation17. While there have been studies to assess the level of integration of adaptation and mitigation, they have focused predominantly on the assessment of climate change adaptation plans (CCAPs)18,19,20. A detailed scoring framework18 has been developed to assess the extent to which mitigation and adaptation were integrated in 147 urban climate change action (CCA) plans in Europe,19. The analytical framework (an ‘urban climate change integration index’) considered whether the CCAPs explicitly stated co-benefits, synergies, trade-offs or conflicts between mitigation and adaptation within the plans.

Some view climate change policy as siloed21, e.g, sitting outside of other policy domains. Yet there is increasing support for the integration of climate change policy with broader sectors (such as the built environment) given its complex and cross-cutting nature10,14,22,23,24,25. The siloed nature of climate change policy has been identified as a potential reason why there is limited capacity to design and implement policy across sectors21. Most recently, the IPCC recognises the importance of climate-resilient development pathways that integrate adaptation and mitigation in order to progress the achievement of sustainable development26. It has been identified that the optimal policy mix for successfully integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation action will vary between contexts, depending on the local values and characteristics of a community25. A review of the relationship between climate change adaptation and mitigation actions, and their integration15, showed how a portfolio of policy instruments can enable synergies. Calls have been made for guidance to assist the development of an appropriate policy mix to address mitigation, adaptation and development that is socially and economically justifiable, and how to most effectively mainstream26. In an analysis of climate change action in 261 European cities, it was found that national mandates influence the local uptake of adaptation policies, indicating the importance of vertical integration27. There is also a need to consider conflict with non-climate goals16, for example, the achievement of equity/justice, and of sustainability. Yet there has been limited research to explore how this integration might be best achieved28.

Looking across multiple policy instrument types, Viguie and Hallegatte27 explored three separate policies in Paris: a greenbelt policy, a zoning policy to reduce flood risk, and a transportation subsidy. They used an integrated city model to quantify trade-offs and synergies between these policies. They found that the consequences of each policy were not simply additive, but rather provided win-win strategies, which were likely to be more politically acceptable. Hence, they advocate the mainstreaming of climate policy within urban planning27.

Given that the interrelationships between adaptation and mitigation actions will vary with the local context, we look at their integration in an ‘interrelationship neutral’ manner, that is, not seeking to evaluate whether trade-offs are occurring. Hence, we define the integration of adaptation and mitigation as occurring when actions to address both mitigation and adaptation are enacted within, (1) each policy instrument singly; and (2) across all instruments in a portfolio. Local governments each have different communities, social and economic contexts, and environments. Therefore, it is assumed that local-level actions to address land use and development, and climate change will differ except for those mandated by higher levels of government.

Despite the increase in academic and practical attention to integrate adaptation and mitigation, further research is needed to consider integration across a whole portfolio of policy instruments. Recent research looked at the integration of emission reduction goals across a whole policy portfolio in an Australian context and found that there was limited integration of Paris Agreement-aligned targets across the whole portfolio7. Additionally, there is a lack of guidance on how effective integration of adaptation and mitigation actions might be achieved in a built environment policy portfolio, and how it may be mainstreamed. This paper seeks to make a contribution to this field by developing an approach to assess the integration of climate change adaptation and mitigation actions in single policy instruments, and policy portfolios, and then apply it to the built environment policy portfolios of three diverse local governments in the state of Victoria, Australia: the City of Melbourne (responsible for the central business district of the state’s capital city); the City of Greater Geelong (responsible for the state’s second largest city and numerous growth areas), and Wellington Shire Council (a regional local government, comparable in size to Lebanon, with coastal, farmland and mountain environs).

Local government in Australia has an important role in defining locally relevant policy that influences land use and development. Accordingly, each of these three local government areas faces different issues relating to: constraints to continued land use and development; challenges in managing population growth; and climate change risks. We are interested to consider the varying equity implications for climate change action between the three local government areas, and in particular, the spatial and temporal dimensions of fairness relevant to climate change and its impacts29. We address the following research questions in this paper:

-

Does the built environment policy portfolio of each local government area integrate and mainstream climate change mitigation and adaptation actions?

-

How do the policy portfolios of the three local government areas compare in terms of climate change integration, and what are the implications of these differences?

The three local governments of focus are located in the state of Victoria, Australia. Thus, their international, national and state policy context is consistent. In Australia, there is a division of powers between the three levels of government30. As such, there is a limited role for the federal government in terms of land use planning, with some influence responding to climate change31,32. It is noteworthy that local government in Australia is relatively limited in its finance33 and power in comparison to most international equivalents34. In parallel, there is a considerable difference in Australian councils’ capacity to provide services and to take actions beyond statutory minima in the built environment35. Australia’s federation requires state legislation to establish most of the responsibilities and mechanisms for the management of the built environment. In Victoria, large state departments have wide-ranging responsibilities. The Department of Transport and Planning includes agencies responsible for urban planning, transport, housing and major projects. Oversight of building standards is maintained by the Victorian Building Authority. Local government in Victoria derives its primary powers and responsibilities from the Local Government Act (2020) of the Victorian State Parliament, enabled by the Victorian Constitution (1975). Local government has responsibilities for a range of matters relating to the built environment, including land use planning. This occurs within the parameters established by the Planning and Environment Act (1987), in conjunction with a variety of other acts including the Local Government Act (2020), Environmental Protection Act (2017), Transport Integration Act (2010) and Climate Change Act (2017). While the Planning and Environment Act (1987) primarily sets out processes and responsibilities, the state-derived and managed Victoria Planning Provisions are the primary regulatory instrument used by local government to manage built environment change, albeit with scope for local variations33. Accordingly, many aspects of local governments’ built environment actions occur within parameters established by state or nationally established frameworks, several of which put forward ambitions targets that respond to climate change7. It is within this State and National context that the comparison of the three local governments was conducted. The full suite of built environment policy instruments (in addition to those laws listed above) applicable at the state, national and international level applicable to the case study local governments can be found in ref. 36.

Recently, the state and federal governments have reiterated the importance of assisting population growth and increased housing production/provision in light of housing shortages (demand exceeding growth and availability) and housing affordability concerns. This includes the Victorian Government’s Housing Statement37 which identifies that the state will need 1.6 million homes by 2051 to keep the problem from getting worse. They set a target to build 800,000 homes in the decade 2023-2024. This aligns with the National Housing Accord 202238, which seeks to deliver 1 million new homes nationally over 5 years from 2024. A proportion of these will be ‘affordable’ and there are energy efficiency requirements too. However, there is limited evident consideration of how this growth might be achieved in a manner that responds adequately to the need to reduce GHG emissions and adapt to climate change, particularly in relation to the embodied emissions of new development and associated infrastructure, if existing resources can not be utilised/reused.

In the case study state of Victoria, there are 79 local governments: 22 in metropolitan Melbourne and an additional nine with a metropolitan-rural interface. The locations of the three local governments chosen for comparison in this research are shown in Fig. 1, and a comparison of their key characteristics is shown in Table 2. The information provided in Table 2 shows the significant differences between the local governments, particularly Wellington’s economic, social and spatial differences. Additionally, the plans and opportunities for future growth differ between each local government.

Panel 1 shows the location of the three local government areas in relation to the State of Victoria (the City of Melbourne is indicated with a star). Panel 2 shows the location of the City of Melbourne in relation to the greater metropolitan area of Melbourne. Panel 3 shows the location of the state of Victoria in relation to Australia. Note: base plans were sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

Results

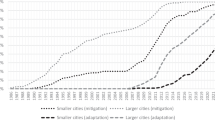

A comparison of the policy portfolios of the three local government areas is illustrated in Fig. 2. It shows that Wellington has fewer built environment policy instruments (9) meeting the study inclusion criteria compared to Geelong (23) and Melbourne (25).

The detailed analysis of each policy instrument can be found in the Data File (Table A1 Wellington, Table A2 Geelong and Table A3 Melbourne) available at39, which shows the coverage of each mitigation, adaptation and co-beneficial action investigated, by policy instrument.

Integrating and mainstreaming climate change mitigation and adaptation actions for each local government

In terms of addressing the first research question, of whether the built environment policy portfolio of each local government integrates and mainstreams climate change mitigation and adaptation actions we can first look to the analysis provided in Tables A1–3 (Data File39). Of all the policy instruments analysed, only two did not integrate a climate change adaptation and mitigation action. These are,

-

the Wellington Domestic Wastewater Management Plan

-

the Geelong Municipal Road Management Plan

Many policy instruments across each local government include only a small number of the actions investigated. For example, of 42 possible actions, ‘vegetation management’, an action that has both adaptation and mitigation benefits, is the only action covered in the City of Melbourne’s Heritage Design Guide.

In looking across the portfolio for each local government, we can see a range of actions to address both adaptation, mitigation and co-benefits. The policy portfolios for each local government do integrate adaptation and mitigation actions. The last row of each table in the Supplementary Data File39 provides a total – the number of instruments that mention each action. They show that some actions are not addressed in any of the policy instruments of a policy portfolio. Thus, the integration may be considered not to be mainstreamed. Overall, Tables A1–3 indicate that climate change has not been mainstreamed into any of the three portfolios; it does not appear to have been used as a systematic40 frame of reference during policy-making22.

A comparison of the three local governments

In addressing the second research question, relating to how the policy portfolios of the three local government areas compare, we can look to Fig. 3 for a comparison of each of the climate actions investigated. Here we see that each local government has a distinctly different policy portfolio in terms of how it incorporates climate change action. Figure 3 displays the integration of climate action within the policy portfolio of the three local government areas in Victoria: Melbourne, Geelong and Wellington. Figure 3a shows the number of policy instruments that include at least one mention of each adaptation action investigated; 3b shows the number of policy instruments that include at least one mention of each mitigation action investigated, and 3c shows the number of policy instruments that include at least one mention of the co-beneficial actions investigated. For each local government, the most frequently mentioned mitigation actions across the portfolio were energy efficiency, walking and cycling. We see differences in the portfolios depending on urban growth type, with Geelong’s mitigation actions including measures such as urban infill, transit-oriented development, density, and compact city, more than the other local governments, which is appropriate for its growth context and existing urban form12.

The most frequently mentioned adaptation actions across the portfolios related to risk reduction, emergency response and hazard reduction. The co-beneficial actions are mentioned across more policy instruments than the single focused adaptation or mitigation actions. As can be seen here, given the smaller number of policy instruments that Wellington Shire has, it has fewer instruments that address each of the actions identified.

Figure 4 provides a comparison of the types of climate change actions addressed in each local government’s built environment policy portfolio as a percentage of the total actions addressed in each policy portfolio (see Tables A1-A3 in the data file). For all local government policy portfolios investigated, co-beneficial actions received the highest percentage of coverage – over 38% of each portfolio. Figure 4 shows that the City of Melbourne policy portfolio had the highest percentage of co-beneficial actions – where 50% of the actions identified were co-beneficial actions. Geelong has the highest percentage of mitigation action with 35%. The detail in Fig. 3 shows Geelong’s focus on a range of planning and design features that can facilitate growth in a mitigation-sensitive manner – a critical issue for Geelong given its high anticipated growth and existing urban form. Likewise, Wellington has the highest percentage of adaptation actions, which is not surprising given their rural location and vulnerability to climate change risks such as bushfire and flooding41.

A comparison of the three local government areas: the City of Melbourne, the City of Greater Geelong and the Wellington Shire Council. Measured by presence or absence of each action per policy instrument in the portfolio. Total present actions for each category (adaptation, mitigation and co-beneficial) were calculated across each portfolio. The percentage represents the split between total adaptation, mitigation and co-beneficial actions per local government policy portfolio.

Discussion

Tables A1–3 show that for each local government, the planning schemes (the only regulatory document for each) – have the highest percentages of actions covered compared to any other instrument (noting many actions are absent). This is not surprising given that their purpose is wide-reaching:

To provide a clear and consistent framework within which decisions about the use and development of land can be made. To express state, regional, local and community expectations for areas and land uses. To provide for the implementation of State, regional and local policies affecting land use and development. To support responses to climate change (Clause 01 of the Victorian Planning Provision on 1st November 2022)

The planning schemes are a core part of the respective policy portfolios – subordinate to the Planning and Environment Act. They are mature instruments that are required by the state, with some locally determined content. However, they are not retrospective and are only activated when land-use changes of certain types are proposed. Other policy instruments in each portfolio are developed to complement the planning scheme or act separately from it.

Wellington Shire Council has significantly fewer policy instruments in its portfolio, and therefore fewer opportunities to implement adaptation and mitigation actions, hence we discuss their portfolio in detail here, and reflect on what this may also mean for other rural local governments. Across the policy portfolio for Wellington, certain actions are conspicuous by their absence, which exemplify the differences between Wellington and the more urbanised Geelong and Melbourne. Examples are ‘transit-oriented design’ (mitigation) and ‘nature-based solutions (NBS)’ (co-beneficial). These can be explained by, respectively, Wellington’s low density and absence of public transport hubs, and as Moosavi and Browne42 showed in a different context, potentially less familiarity with, and slower uptake of the concept of NBS in regional or non-academic circles, including policies. Given Wellington’s large size, transport-related mitigation actions will be beneficial to consider. However, those with significant potential, such as transition of the vehicle fleet, may well be beyond the scope of the built environment policy portfolio.

For Wellington, the document with the highest percentage of mitigation actions was the Planning Scheme (83%), followed by the Regional Growth Plan (50%) and the Sustainability Strategy (50%). The Domestic Wastewater Management Plan and Integrated Water Management Plan had no mitigation actions, whereas all others had less than 50% of investigated mitigation actions addressed in the instrument. The policy instruments with the highest percentage coverage of adaptation actions were the Planning Scheme and Council Plan (50%), followed by the Gippsland Regional Climate Adaptation Strategy (45%). All others had less than 30% of adaptation actions addressed, with the Open Space Plan and Domestic Wastewater Management Plan each having none. However, they did have co-beneficial actions that can contribute to adaptation. The Integrated Water Management Plan had the highest coverage of co-beneficial actions (73%), followed by the Open Space Plan. The Planning Scheme, the Council Plan and the Infrastructure Design Manual each with 64%. The Domestic Water Management Plan had no actions covered.

In terms of the Wellington Shire Council built environment policy mix, it could be assessed that there is integration of adaptation and mitigation actions across the policy portfolio in simple terms. However, there is an opportunity for greater holistic integration. For example, it would be beneficial for the following to occur:

-

The Domestic Wastewater Management Plan to address climate change (both adaptation and indirect impacts on mitigation)

-

The Gippsland Regional Climate Change Adaption Strategy – opportunity for greater action articulation, particularly mitigation action

-

While the Integrated Water Management Plan addresses adaptation quite well, there is an opportunity for addressing mitigation actions more directly

-

Gippsland Regional Growth plan – greater attention to adaptation

-

Greater mix of policy instruments – regulations and laws in particular

-

Across the policy portfolio – greater coverage of urban form-related mitigation actions and greater coverage of adaptation actions, particularly in relation to adapting existing infrastructure.

Research has shown that for climate change adaptation, fairness is an important guiding principle. However, it has also been show that some components of fairness – such as spatial dimensions – have received less attention than others – such as distributive and procedural components29. In comparing the three local governments in our study, and understanding their characteristics (Table 2), we can anticipate that in future, it will be important for higher levels of government (e.g. state and federal), who have influence over distribution of resources, to consider aspects of fairness when planning for climate change adaptation, and in particular spatial components of fairness. This will assist local governments, such as Wellington, in rural locations with more challenging socio-economic characteristics, and complex land management contexts in their adaptation planning.

Our research has provided the following insights:

-

A limited set of actions to address climate change adaptation and mitigation is activated in built environment policy instruments. There is potential to incorporate further climate change action within built environment policy portfolios in the local government areas investigated.

-

There is considerable difference between the amount and type of climate change policy instruments between local governments. The potential for climate change actions varies considerably across local government areas. Attention needs to be paid to the specific characteristics of a local government to maximise the benefits of actions.

-

While local governments have some scope to develop specific actions and local initiatives, this occurs within a complex and often constrained range of state and sometimes nationally established frameworks, which also need full consideration and continual renewal.

-

The rapid growth expected in some local government areas provides an important opportunity to integrate climate change actions in the built environment – effective policy can assist achieve this.While co-beneficial actions are critical, they should provide specific references to how mitigation and adaptation actions are addressed, outlining potential trade-offs and synergies.

-

The framework used for analysis could be used by other jurisdictions in the assessment, renewal and design of built environment policy portfolios for climate action

In future research, it would be beneficial to move beyond an interrelationship neutral consideration of integration to consider whether trade-offs or conflicts arise between the implementation of adaptation and mitigation action – which would require a close examination of development examples and interviews with key stakeholders. Additionally, consideration of how these actions to address climate change are integrated vertically between other levels of governance in practice would be beneficial.

Research method

In this paper, we undertake a comparative critical review of the policy portfolio for each of the three local government areas, focussing on local-level policy instruments. The three local governments were chosen for their contrasting characteristics (as described earlier in the paper). Our project’s expert reference group encouraged the comparison of the City of Melbourne with local governments representative of other development contexts in the state, including rapidly developing and rural areas. The key components of the research method are outlined here.

The built environment policy instrument portfolios

The criterion for an instrument to be included in the analysis was that it had to be “influential in guiding decision-making (of public or private actors) about the form and function of the built environment at the scale of the local government”. In turn, the definition of built environment used was from the 2016 Australian State of Environment Report43 [p. 2]. To identify all policy instruments that fulfilled this criterion, the three local governments’ websites were systematically searched, and all council-authored documents were downloaded for analysis. Additional relevant documents were sourced from regional authorities, NGOs and professional organisations. Policy instruments that were effective 1st November 2022 were the focus. Each instrument was categorised for its type, governance level, sector and the life stages for which it is relevant as defined in ref. 36. Members of the research team then collectively decided which documents conformed to the criterion. This yielded 57 instruments; 25 for the City of Melbourne, 23 for the City of Greater Geelong, and 9 for the Shire of Wellington, thus forming each local government’s policy portfolio for the purposes of this research. The list of instruments evaluated is available in Tables A1-A3 in the associated data file39.

Method of assessing the policy instruments

The assessment approach was informed by the method described in11, but with a particular focus on assessing two of the portfolios’ attributes; the inclusion of climate actions (adaptation, mitigation and co-beneficial) across policy instrument content singularly, and then across each local government’s built environment policy portfolio – at the local governance level. Each instrument’s documentation was systematically searched for the inclusion of mitigative, adaptive and co-beneficial policy actions using the key words in Table 1, in a process described in Table 3. If an instrument was found to contain a keyword, then the context was checked, and if the word was used to describe a policy action about that issue, then, using an Excel spreadsheet, a 1 was recorded for that action, for that instrument. If the instrument’s documentation did not mention that keyword, 0 was recorded. Note, the action was included whether or not its stated purpose was to address climate change, the fact that the action was being taken was sufficient for our analysis. This resulted in a matrix of approximately 2394 binary-coded (0 red or 1 green) cells (57 instruments by 42 actions), presented in Tables A1-A3 in the Data File39. Summary data that capture key themes are presented in Figs. 2 to 4.

Data availability

Data is available at: Hurlimann A, Brown GR, Moosavi S, March A. (2025) Supplementary data file for article: Integrating adaptation and mitigation actions within built environment policy portfolios: An Australian local government comparison. Figshare, The University of Melbourne: Melbourne. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26188/28630199.

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022).

United Nations, Paris Agreement. 2015, Viewed online 2/11/2017 at: http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf.

United Nations Environment Program, Emissions Gap Report 2022. The Closing Wondow: Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies., Nairobi: United Nations Environment Program. (2022).

United Nations Environment Program, Adaptation Gap Report 2024: Come hell and high water, UN Environment Program: Nairobi. (2024).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for Policy Makers: Synthesis Report of The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; World Meteorological Organisation; United Nations Environment Program. (2023).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/ (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2018).

Hurlimann, A., et al., Translating global emission reduction goals into built environment policy: An ambitious yet inadequate policy mix for Victoria, Australia. Climate Policy, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2025.2459319 (2025).

United Nations Secretary General, Press Release: Secretary-General’s video message for press conference to launch the Synthesis Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change., 20th March. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2023-03-20/secretary-generals-video-message-for-press-conference-launch-the-synthesis-report-of-the-intergovernmental-panel-climate-change. (United Nations, 2023).

Hurlimann, A. C., Moosavi, S., and Browne, G. R., Climate change transformation: A definition and typology to guide decision making in urban environments. Sustain. Cities Soc. 70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102890 (2021).

Klein, R. J. T., et al., Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation, in Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Parry, M. L. et al.) 745–777 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007).

Browne, G. et al. Better policy to support climate change action in the built environment: A framework to analyse and design a policy portfolio. Land Use Policy 145, 1–11 (2024).

Lwasa, S., et al., Urban systems and other settlements., in IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change P. R. Shukla, et al., Editors., Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. (2022).

Dodman, D., et al., Cities, Settlements and Key Infrastructure., in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, H.-O. Pörtner, et al., Editors., Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. (2022).

Howarth, C. & Robinson, E. J. Z. Effective climate action must integrate climate adaptation and mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 300–301 (2024).

Landauer, M., Juhola, S. & Söderholm, M. Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation: a systematic literature review. Clim. Chang.: Interdiscip. Int. J. Devot. Descript. Causes Implic. Clima Chang. 131, 505–517 (2015).

Van Asselt, H., T. Rayner, and Å. Persson, Climate Policy Integration, in Research Handbook on Climate Governance, K. Bäckstrand and E. Lövbrand, Editors. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham UK. (2015).

Gopfert, C., Wamsler, C, and Lang, W, A framework for the joint institutionalization of climate change mitigation and adaptation in city administrations. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, p. 1. (2019).

Grafakos, S. et al. Integration of mitigation and adaptation in urban climate change action plans in Europe: A systematic assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 121, 109623 (2020).

Reckien, D. et al. How are cities planning to respond to climate change?: Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J. Clean. Prod. 191, 207–219 (2018).

Grafakos, S., et al., Analytical framework to evaluate the level of integration of climate adaptation and mitigation in cities. Clim. Change, 154: p. 87–106 (2019).

Boyd, D. et al. Mitigation co-benefits of climate change adaptation: A case-study analysis of eight cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 77, 103563 (2022).

Adelle, C. & Russel, D. Climate Policy Integration: a Case of Déjà Vu?. Environ. Policy Gov. 23, 1–12 (2013).

Dupont, C., Climate Policy Integration in the EU, in The Economic, Social and Political Elements of Climate Change, W. L. Filho, Editor, Springer-Verlag: Berlin. p. 385–404. (2011).

Viguié, V., Hallegatte, S. & Rozenberg, J. Downscaling long term socio-economic scenarios at city scale: A case study on Paris. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 87, 305–324 (2014).

Klein, R. J. T., Schipper, E. L. F. & Dessai, S. Integrating mitigation and adaptation into climate and development policy: three research questions. Environ. Sci. Policy 8, 579–588 (2005).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.] 184 https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647 (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023).

Viguie, V. and Hallegatte, S., Trade-offs and synergies in urban climate policies. Nature Climate Change. 2, 334–337. (2012).

Daniell, K. A. et al. Aiding multi-level decision-making processes for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Reg. Environ. Change 11, 243–258 (2011).

Graham, S. et al. Towards fair local outcomes in adaptation to sea-level rise. Clim. Change 130, 411–424 (2015).

Parliamentary Education Office. The roles and responsibilities of the three levels of government. 19th July 2022 [cited 2023 25/7/2023]; Available from: https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/how-parliament-works/three-levels-of-government/the-roles-and-responsibilities-of-the-three-levels-of-government/. 2022.

Nalau, J., Preston, B. L. & Maloney, M. C. Is adaptation a local responsibility?. Environ. Sci. Policy 48, 89–98 (2015).

Hurlimann, A., Flood and Fire and Famine: Australia as an outlier of planning for climate change, in Planning in an uncanny world: Australian urban planning in international context, N. Phelps, J. Bush, and A. C. Hurlimann, Editors. Routledge New York. p. 51–69. (2022).

Dollery, B., Crase, L. & Byrnes, J. Local government failure: Why does Australian local government experience permanent financial austerity?. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 339–353 (2006).

Althaus, C., Bridgman, P., and Davis, G., The Australian Policy Handbook: a practical guide to the policy-making process. 5 ed., Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin. (2013).

Dollery, B., Wallis, J. & Allan, P. The debate that had to happen but never did: The changing role of Australian local government. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 553–567 (2006).

Hurlimann, A. et al. Climate change transformation in built environments – A policy instrument framework. Urban Clim. 53, 101771 (2024).

Department of Premier and Cabinet, Victoria’s Housing Statement: The decade ahead 2024-2034, https://www.vic.gov.au/housing-statement (Victorian Government, Melbourne, 2023).

Australian Government, National Housing Accord 2022. Australian Government: Canberra. https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/sites/ministers.treasury.gov.au/files/2022-10/national-housing-accord-2022.pdf (2022).

Hurlimann, A., et al., Supplementary data file for article: Integrating adaptation and mitigation actions within built environment policy portfolios: An Australian local government comparison, https://doi.org/10.26188/28630199 (Figshare. The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, 2025).

Pittock, J., Hussey, K. & Dovers, S. Ecologically sustainable development in broader retrospect and prospect: evaluating national framework policies against climate adaptation imperatives. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 22, 62–76 (2015).

Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, CSIRO, Gippsland Climate Projections, State Government of Victoria: Melbourne. https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/media/ccia/2.2/cms_page_media/508/Vic%20Climate%20Projections%202019%20Regional%20Report%20-%20Gippsland_20200219.pdf (2019).

Moosavi, S., Browne, G. R. & Bush, J. Perceptions of nature-based solutions for Urban Water challenges: Insights from Australian researchers and practitioners. Urban For. Urban Green. 57, 126937 (2021).

Coleman, S., Australia state of the environment 2016: built environment, in independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment and Energy, Department of the Environment and Energy: Canberra. (2017).

Wurundjeri. Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP). Cultural Heritage [cited 2024 November 1]; Available from: https://www.wurundjeri.com.au/services/cultural-heritage/rap/. (2024).

Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. The responsibilities of the RAP. Home [cited 2024 November 1]; Available from: https://www.wadawurrung.org.au/. (2024).

GLaWAC. Our Story. We are Gunaikurnai [cited 2024 November 1]; Available from: https://gunaikurnai.org/our-story/. (2024).

ABS, Regional Population Growth Australia, 2022-23, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/2022-23 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 2019).

Thompson, J. et al. A global analysis of urban design types and road transport injury: an image processing study. Lancet Planet. Health 4, e32–e42 (2020).

DEECA, Barwon South West Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action: Melbourne (2021).

DEECA, Greater Melbourne Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action: Melbourne (2021).

DEECA, Gippsland Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action: Melbourne (2021).

Department of Transport and Planning. Developing a new Plan for Victoria: Statewide housing targets. [cited Viewed 2025 at: https://engage.vic.gov.au/project/developing-a-new-plan-for-Victoria/page/housing-targets-2051 25/2/25]. (2025).

.id Community. Local government economic profiles [cited 2024 October 17]; Available from: https://economy.id.com.au/. (2024).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Search Census data Viewed 16/10/2024 at: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/search-by-area]. (2021).

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 87310DO008_202408 Building Approvals Australia, August, (Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, 2024).

Remplan. Remplan Region Explorer. [cited 2024 Viewed 16/10/2024 at: https://app.remplan.com.au/]. (2024).

Victorian Auditor-General's Office. Results of 2022–23 Audits: Local Government. Viewed 16/10/2024 at: https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/report/results-2022-23-audits-local-government?section=]. (2024).

City of Melbourne, Annual Report 2022-2023., City of Melbourne: Melbourne. (2023).

City of Greater Geelong, Annual Report 2022-2023., City of Greater Geelong: Geelong. (2023).

Wellington Shire Council, Wellington Shire Annual Report 2022/23, Wellington Shire Council: Sale. (2023).

Sharifi, A. Co-benefits and synergies between urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141642 (2021).

Howlett, M. What is a Policy Instrument? Tools, Mixes, and Implementation Styles, In: Designing Government: From Instruments to Governance (eds Eliadis, P. et al.) 31–50 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP 200101378. We thank Ella Anderson for research assistance with a component of the literature reviewed in this paper. We acknowledge discussions with colleagues that have contributed to components of this work including Judy Bush, Georgia Warren-Myers and Josh Nielsen. We thank our Expert Reference Group for their advice and suggestions across the project duration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H: conceptualised the research idea for the paper; wrote the original draft of the paper; conducted review and editing; developed Figures 2, 3 and 4; Box 1; Tables 1, and A1–3. G.B: conducted the data analysis, contributed to writing the original draft of the paper; conducted review and editing; developed Figure 1, Tables 2 & 3, and contributed to Tables A1-3. All authors: contributed to the research method design and reviewed/edited the manuscript drafts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hürlimann, A., Browne, G.R., Moosavi, S. et al. Integrating adaptation and mitigation actions within built environment policy portfolios: an Australian local government comparison. npj Clim. Action 4, 51 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00256-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00256-z

This article is cited by

-

Smart cities, hot cities: ML-based forecasting of urban heat patterns

Discover Sustainability (2025)