Abstract

Globally, river basins are increasingly vulnerable to climate change. There is a dearth of information on the adaptation responses in Africa’s river basins, especially regarding whether the response process is incremental or transformative. The study applied a household questionnaire to survey 1,500 farmers across the ten major river basin sites, examining their perceived impacts of climate change and adaptation responses. Through a participatory process, we identified (a) the major challenges and potential opportunities during the adaptation process and (b) evaluated if the adaptation process was incremental or transformative. The results revealed that the local farmers perceived multiple climate change impacts, with the majority responding through agriculture intensification and diversification. The study observed that almost all the river basin sites faced similar challenges, although some were context-specific. The climate change adaptation process was largely incremental; however, three river basins in Southern and Eastern Africa exhibited transformative adaptation processes due to strong social capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Africa’s river basins flow and extend beyond boundaries, demonstrating an interdependent socio-ecological system among countries1,2. Observed climate change impacts in Africa’s river basins are due to the rise in temperature and increased rainfall, coupled with frequent droughts and floods. The river flows in Southern and West Africa is declining due to declining trends of annual rainfall, coupled with increased temperature and frequent droughts2,3,4.

In most of Africa’s river basins, huge uncertainty exists regarding the impact of climate change on local communities due to limited studies and unreliable climate models2. For the remote river basin regions, field studies on the local subsistence farmers cannot only reveal the impacts of climate change relevant to the local communities5, but can also help in collecting baseline information and data crucial for formulating an effective adaptation response strategy6,7. The local indigenous knowledge of subsistence farmers is increasingly becoming relevant to climate change research in remote parts of the world with limited data8,9,10.

The current research studies on climate change impacts and local adaptation responses in Africa11,12,13 are insufficient in the major river basins. The IPCC Sixth Assessment report has reported observed climate change impacts on local communities living near major river ecosystems in Africa2. Between 2000 and 2015, the local population vulnerable to floods in Africa and Asia increased by 22%14. By 2050, approximately one billion people in Sub-Saharan Africa will be vulnerable to climate change15. The IPCC Sixth Assessment report warns that the increased amount of rainfall and rise in temperatures necessitate more local adaptation responses in the river basin regions.

Climate change impacts are anticipated to become more devastating in the African continent. For the local communities to adapt, incremental adaptation responses must be coupled with transformational adaptation responses7,16,17. Recent studies on climate change adaptation in Africa have demonstrated incremental changes rather than transformative change17,18.

In this study, we first aim to evaluate the perceived climate change impact and local adaptation responses in the 10 major river basins in Africa (Table 1). The study applied a semi-structured questionnaire, which was administered to 1500 subsistence farmers (150 at each study site), and conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with the local elders of the community. Following ref. 19, as a guide, we came up with a list of (a) observed climatic changes, (b) impacts of climate change on the local agricultural economy, and (c) local adaptation responses that were relevant to each study site.

Secondly, we examined for each study site (a) the main challenges and opportunities for adaptation using the IPCC guidelines provided by ref. 16, and (b) if the local adaptation responses were incremental or transformative, using the framework applied by ref. 17. This comparative study revealed common patterns across the river basins in perceived climate change impacts and adaptation responses. However, some site-specific attributes could be considered if we are to assist the local subsistence communities to better adapt to the climate change impacts and develop sustainable, transformative solutions. This research study serves as a baseline for integrating indigenous and local knowledge20 on climate change adaptation into climate change research in remote and data-deficient river basin regions in Africa. This will significantly contribute to the formulation of sustainable policies and practices on transformative climate change adaptation.

Results

Perceived climate change impacts in the river basins

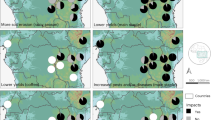

Eight climate change impacts were reported by local respondents in almost all the study sites (8 out of 10 river basin sites), which include reduced river flow due to declining trends in annual rainfall, increased soil erosion, lower crop yield (main staple crop) and milk production, increased crop and livestock diseases and reduced human health (Fig. 1). Landslides occurrence was less reported in almost all the river basin sites while lower cash crop yield (fruits, tea and coffee) was only reported in four sites (Fig. 1). These perceived climate change impacts were closely linked to eight different climatic changes which the local respondents observed. These include increased temperatures, below-average precipitation, late onset of long rains, more prolonged dry spells, more showers, more extreme floods and droughts, and increased wind strength during the rainy season (Fig. 2).

The data shows the percentage of respondents from each study site representing climate change impacts, with 150 respondents per site. It’s important to note that the responses were based on predetermined questions, and some impact-related questions did not apply to certain sites. The map was created using ArcMap 10.8.

Previous study by ref. 14 observed similar climatic change impacts in a few of Africa’s river basins, however, we now extend these to the major river basins in Africa, including the Congo river (CR), Mara river (MR), Zambezi river (ZR), Niger river (NGR), Nile river (NIR), Volta river (VR), Orange river (OR), Limpopo river (LR), Okavango river (OKR) and Senegal river (SR). Few studies on Africa’s river basin have been able to acknowledge reduced human health as a climate change impact, even though it has been reported by the ref. 2. The local respondents in this study linked reduced human health to an increase in water-borne diseases (cholera, dysentery, and typhoid) and the spread of malaria in all river basin sites. Since it is a public health concern, it necessitates further investigation.

The late onset of long rains and below-average precipitation, which was widely reported, affected the crop yield of the main staple crops (maize, beans, cassava, Irish potatoes, and yams). This has led to the sowing of staple crop seeds twice during the planting season. “These days, due to unpredictable rainfall patterns, we plant the seeds twice if they die due to lack of moisture” (farmer comment in the Mara river basin, Kenya). The declining trends in annual rainfall have led to reduced river flow. Farmers relying on river water for irrigation have been impacted; some, who grow short-term or horticultural crops, have experienced low crop yields and increased pests and diseases. The IPCC report acknowledges the changes in the rainfall patterns in the river basins, which have negatively affected the livelihoods of the local population residing near the rivers in Africa. The scientific community is increasingly recognizing the uncertainty of data collected by the weatherman and the lack of a comprehensive view on ongoing climate change impacts experienced by the locals21,22,23. Our results agree with this statement, illustrating that local farmers in Africa’s major river basins are experiencing a wide range of climate change impacts simultaneously, and most of the impacts are well spread across the river basins.

Local adaptation responses to climate change impacts in the river basins

Eight on-farm and off-farm climate change adaptation responses were reported by a large percentage of the local respondents in almost all the river basin sites (8 out of 10 river basins). These include the use of improved crop varieties, a change of planting dates, the sowing of seeds twice (in case they die), an increase in the use of pesticides and fertilizers, increased irrigation, soil conservation techniques, an increase in livestock rearing, vegetable/fruit production, sell of firewood and charcoal, small business venture, timber/lumbering activities and diversification in off-farm labor (Figs. 3 and 4). In the four cash crop growing sites—coffee, tea, and citrus fruits—the farmers adopted new crop varieties that are resilient to the impacts of climate change. They also increased their use of pesticides. Additionally, one off-farm and one on-farm climate change adaptation response were reported in three of the sites. For example, there was an increase in farm size along the Orange river and Limpopo river in Southern Africa and a rise in mining activities along the Congo river in the Democratic Republic of Congo (see Figs. 3 and 4). Although local respondents are aware of the impacts of climate change and have high literacy rates, over 60% of those surveyed across seven river basin sites rely on Indigenous Local Knowledge (ILK) to make decisions about when to sow their seeds (see Table 1). However, the importance of ILK for local farmers is expected to diminish over time due to changes in climatic patterns, which include alterations in rainfall patterns such as a delayed onset of the long rains, prolonged dry spells, and decreasing trends in the overall amount of rainfall during these periods24,25.

The data shows the percentage of respondents from each study site representing the on-farm adaptation response, with 150 respondents per site. It’s important to note that the responses were based on predetermined questions, and some questions did not apply to certain sites. The map was created using ArcMap 10.8.

The data shows the percentage of respondents from each study site representing the off-farm adaptation response, with 150 respondents per site. It’s important to note that the responses were based on predetermined questions, and some questions did not apply to certain sites. The map was created using ArcMap 10.8.

We examined whether the increased number of perceived climatic changes significantly influenced the adaptation responses by applying the mixed-effects model (see “Methods” section). For instance, in the Mara river basin (Kenya), it was demonstrated that the farmers who were able to track meteorological information sent by the government to their mobile phones from previous years achieved increased crop production due to better on-farm decisions, for example, good timing of the planting season and rainfall patterns. We established that there was no significant relationship between the proportion of perceived climatic change and the proportion of climate change adaptation responses (slope = −0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.162 to 0.113) (see Fig. 5). Household wealth status was a major driver of climate change adaptation. This was evident as the poor households applied very few climate change adaptation measures, as compared to the average wealthy households (difference = −0.035, 95% CI = −0.067 to −0.003), while the rich households adopted more adaptation responses as compared to the average wealthy household (difference = 0.028, 95% CI = −0.031 to 0.089). The river basin sites also significantly influenced the climate change adaptation responses. Generally, in the river basin sites that exhibited a low proportion of climatic change adaptation responses, the households were poor (even the wealthy households in the Congo, Okavango, and Niger river basins were rather poor). Households near the Mara, Nile, Volta, Orange, and Limpopo rivers that reported more adaptation responses were generally wealthier, but even poorer households also showed notable climate change adaptation responses (see Fig. 5).

The graph shows a linear mixed-effects model of adaptation based on household wealth status, with the study site as a random effect (95% confidence level). The river basin sites are plotted for the average proportion of adaptation, respectively. CR Congo river (Democratic Republic of Congo), OKR Okavango river (Angola), NGR Niger river (Mali), SR Senegal river (Senegal), ZR Zambezi river (Zambia), VR Volta river (Ghana), NIR Nile river (Uganda), MR Mara river (Kenya), LR Limpopo river (South Africa), and OR Orange river (South Africa).

Discussion

The overall results obtained on the local climate change adaptation responses in the river basin sites reveal that most of the local farmers responded to the climate change impacts through the application of diverse adaptation responses, with a large percentage on agricultural intensification. In almost all river basin sites, farmers adopted new crop varieties that are resilient to adverse weather changes, coupled with intensive fertilizer and pesticide applications and soil conservation measures, as shown in Fig. 3. These adaptation measures were largely supported by external stakeholders (Table 2). In the Congo river basin site (Democratic Republic of Congo), the extension services from the government on the farm inputs (fertilizers, pesticides) were not readily available. This is due to the ongoing conflict in the Eastern part of the country and a lack of basic infrastructure (roads and bridges) to transport the farm inputs. However, there was a high penetration of over 70% of improved hybrid maize seeds (the main staple crop) in most of Africa’s river basin sites. Overall, the climate change adaptation measures or responses by the farmers in the river basins tend to be more behavioral as opposed to technological or science-based.

Agricultural intensification practices by the local farmers were not largely driven in response to the climate change impacts, but also by other emerging factors. These include land fragmentation as a result of high population, which necessitated improved productivity on the small land size (Table 1), the global trade system, and the government policies on agriculture (for instance in the Mara river basin, Kenya, the government is encouraging farmers to embrace the hybrid maize, potatoes and beans varieties with less emphasis on the traditional crops such as millet, sorghum, cassava, sweet potato and yams). Regardless of the emerging factors driving agricultural intensification, the sustainability of the intensive use of chemicals (pesticides, herbicides) and fertilizers should be explored further. These practices have led to high water pollution in the river basin sites, thus becoming a major threat to freshwater biodiversity. There were also instances where the local farmers reported that the high cost of improved seeds led them to still reuse previous harvest seeds, which led to low crop yields.

A closer examination exposes certain limitations of organic farming in comparison to conventional methods26. Organic agriculture is frequently presented as being more sustainable than conventional farming, which relies heavily on fertilizers and pesticides. While organic farming—characterized by the avoidance of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides—can be a viable option for some farmers, utilizing these methods to support a growing population would involve significant trade-offs. The patterns of adoption for these sustainable agricultural technologies underscore the influence of market dynamics and risk management on farmers’ choices concerning crop and soil management practices. Consequently, any discussion about sustainability must take into account these economic factors and the financial implications of proposed interventions for farmers26.

Most of the river basin sites had similar on-farm climate change adaptation responses; however, there were significant differences in the off-farm adaptation responses due to context-specific factors. For instance, farmers in the Mara, Orange, Limpopo, Nile, Volta, and Zambezi rivers have diversified into vegetable and fruit production due to nearby urban markets and export opportunities. In contrast, those along the Congo, Niger, Senegal, and Okavango rivers focus on diversification primarily for food security, supported by NGOs and national governments. The context-specific factors also influenced specific adaptation responses, for instance, in the Congo river basin site, the farmers opted to engage more in mining and lumbering activities due to the ravaging war conflict in the Eastern part of the country. Few local farmers invested in animal rearing, as there was the likelihood of conflict affecting the farming activities and frequent displacement from their land.

There is increased adoption of the early warning system as a strategy to mitigate climate change impacts. The farmers in the Mara, Orange, Limpopo, Nile, Volta, and Zambezi rivers embraced the use of USSD code messages as an early warning strategy. The meteorological department, in collaboration with agricultural research institutions and national governments, would periodically send short messages regarding key agricultural information. These messages include optimal planting dates, rainfall patterns, crop pests and disease management, animal pest and disease control, flood and drought warnings and responses, human health issues, and access to new seed varieties and fertilizers.

Various forms of climate change adaptation are becoming increasingly common in African countries, one of which is rural-to-urban migration27. However, climate change is not the only reason for this outmigration; other interdependent factors, such as socio-political, economic, and environmental influences, also play a significant role28. This study did not recognize rural-to-urban migration as a climate change adaptation response. Local farmers in the river basin areas attach great sentimental value to their land due to its productivity in food production. Some farmers at the Mara river basin (Kenya) commented, “Our land has high food productivity, therefore it is much easier to earn income and live in the rural areas as opposed to urban centers where there are limited opportunities.” These findings corroborate the study by ref. 29.

The data collected during FGDs at the river basin sites, coupled with the IPCC list of challenges and potential opportunities on climate change adaptation30, identified the socio-physical (lack of strong farmers’ associations, roads, and limited land) and financial factors (low credit access) as the main challenges affecting adaptation in almost all the study sites (see Table 3). Other factors include governance/institutional factors (inability to form associations and lack of existing agricultural policies that incentivize farmers); knowledge, awareness, and technology (low skill level on new technologies). The national agricultural policies and existing regulations need to be evaluated by governments to enhance climate change adaptation and resilience for local farmers. A participatory approach should be adopted to engage farmers through FGDs that explore the challenges they encounter in adapting to climate change in their specific regions.

The identified potential opportunities in the study include high mobile penetration and communication, along with a growing awareness of climate change impacts (see Table 3). These findings support the study by ref. 31. The improved access to affordable mobile phones and low-cost communication technology across Africa, particularly in the interior and remote parts of the continent (for instance, the Congo river basin) has led to increased awareness and dissemination of information on weather, climate, pests and diseases, new technology, credit access, farm inputs, market prices and access. The support from external stakeholders/actors and the farmers’ entrepreneurial skills proved to be an opportunity in most river basin sites (see Table 2). Most local farmers were willing to experiment with new ideas and technologies. For instance, the farmers at the Mara river, Kenya, and the Nile river, Uganda, commented that, “Our farms are becoming more productive as we adopt new techniques like drip irrigation, minimum tillage, organic fertilizers, biogas capture, and zero grazing. While some methods have faced challenges, we remain open to new ideas.” Our study shows that despite the high initial costs of technologies such as biogas capture and drip irrigation, many farmers are willing to adapt and diversify their income, especially with improved access to information and markets in the region.

Our study, based on the framework provided by ref. 17, found that most river basin sites demonstrated incremental rather than transformative climate change adaptation. However, the Orange, Limpopo, Mara, Nile, and Volta river basins showed signs of moving toward transformative adaptation (see Table 2 and Fig. 5). The transformational characteristics observed across the five sites include the exchange of knowledge and new ideas among farmers, access to credit, and a willingness among farmers to experiment with innovative practices. For example, in the Mara river basin, farmers received subsidized government fertilizers and seeds. They also benefited from strong social networks known as SACCOs (Savings and Credit Cooperatives), which provided access to loans and farm inputs on credit. Wealthy farmers along the Orange and Limpopo rivers were willing to share their expertise on improved seeds, effective fertilizers, and techniques for managing pests and diseases. They also provided their fellow farmers with access to new hybrid seeds for trial purposes at no cost. In the Nile river (Uganda), the presence of farmers’ associations and increased remittances from urban areas, due to better access to markets for their produce, has shown how willing the farmers are to diversify their responses to the impacts of climate change. In the Volta river region of Ghana, strong government support, the presence of farmers’ associations, and the sharing of knowledge among local farmers have contributed to a more effective response to the impacts of climate change. These various factors highlight that there are multiple pathways towards transformational adaptation. This aligns with previous studies17,18,32, which have shown that climate change adaptation in Africa tends to be incremental, with some regions slowly progressing towards transformative change.

Two key areas of priority have been identified to enhance the resilience and adaptation responses of local farmers to the impacts of climate change across Africa’s river basins (see Table 4 and Box 1). These recommendations are based on information collected during the study and discussions held with local stakeholders at the 10 river basin sites. The first priority focuses on increasing access to loans, markets, skill development, and knowledge exchange among stakeholders. The second priority addresses government policy and governance issues, which significantly affect the adaptation process. Many remote communities are often marginalized in socio-economic development projects, and their concerns are not adequately represented in political discussions. The participatory approach used during FGDs at the village level was crucial for identifying the key priority areas to address. This approach is becoming increasingly important due to the involvement of research experts from various sectors who can collaborate and share knowledge and ideas to improve community livelihoods33,34. River basins are sensitive ecosystems and culturally diverse areas that can benefit from a participatory process. By engaging stakeholders from different socio-economic and environmental backgrounds, we can create transformative pathways to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Methods

Data collection and analysis

Ten local study sites were selected in the 10 river basins encompassing geographical (amount of rainfall), socio-economic (local living standards, market access), and political aspects (different countries (Fig. 6)). The selection of the study sites encountered challenges, such as ongoing conflict in Eastern Congo. In each of the river basin study sites, four villages were selected along the river basin. The villages were selected based on access by road. In each of the four villages, FDGs were carried out with village elders. The study’s objective was clearly outlined to the village chief, who discussed it with the elders (above 55 years old). FDGs were applied to formulate a standard semi-structured questionnaire based on the study context and to foster trust among the local population. The questionnaire for the 10 sites entails a list of (1) observed climatic changes, (2) impacts on the local agriculture, and (3) local adaptation responses35, that were suitable for each study site, as agreed by the FDGs stakeholders. Data on the local agents of change (government, NGOs, local CBOs) empowering local communities to respond to climate change impacts and perceived challenges regarding adaptation were collected during FDGs.

CR Congo river (Democratic Republic of Congo), OKR Okavango river (Angola), NGR Niger river (Mali), SR Senegal river (Senegal), ZR Zambezi river (Zambia), VR Volta river (Ghana), NIR Nile river (Uganda), MR Mara river (Kenya), LR Limpopo river (South Africa), OR Orange river (South Africa). The map was created using ArcMap 10.8.2.

In each of the four villages, we administered semi-structured questionnaires to an average of 38 randomly selected households (total n = 150 per river basin study site) to interview approximately 50% males and 50% females, particularly the head of the household (the decision maker). In every village, the household selection was done through walking along the main access road or accessible footpath, and every third household on the right side was selected. In case the head of the household was not present, the immediate next-door household was selected. The head of the household who opened the house door (male or female) was the first to be interviewed, until the required sex quota for the village was attained; as a result, the other sex was interviewed in the next-door household. This was done due to the absence of a register for the households in most study sites. The “main access road” technique could have resulted in interviewing wealthier households in Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda. As the main objective of this research study was based on comparison across study sites as opposed to within study sites, we concluded this could not affect the overall research; however, future research could examine the household differences within study sites.

The data collected in the questionnaires entailed household characteristics and assets, observed climatic changes, impacts on the local agriculture, the local climate change adaptation responses, climate change literacy level (being aware of climate change coupled with the know-how and acknowledgment that it is human-induced), and climate information services36.

The method and questionnaire applied were based on the guidelines of the “Local Indicator of Climate Change Impacts,” which was a research project that aimed at obtaining data on the role of the local and indigenous knowledge in research on climate change35. We revised the framework formulated by ref. 37, whereby the climatic changes and the climate change impacts observed were differentiated. We complied with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change16 and the word “climate change” was applied to imply changes in the climate that occur due to average changes or variation of its characteristics over a long time. The word “local perception of climate change” was applied to imply information obtained from local communities or people concerning climate change (temperature, rainfall).

The FDGs and household questionnaires were conducted using the local languages that is Kikongo (Congo river), Swahili (Mara river), Luganda (Nile river), Bambara (Niger river), Chewa/Tonga (Zambezi river), Zulu/Xhosa (Orange river), Zulu/Xhosa (Limpopo river), Umbundu/Kimbundu (Okavango river), Wolof (Senegal river), Akan/Ewe (Volta river) and were administered by local correspondents and some co-authors between September, 2024 and July, 2025. All the local inhabitants who participated in the FDGs and household questionnaires volunteered to participate and were educated on the study objectives: to examine and understand the climate change impacts and local adaptation measures undertaken by the local communities. Informed consent was obtained orally in the local language, clearly outlining the study objectives, emphasizing that participation was completely voluntary, ensuring confidentiality, and explaining the procedure for withdrawal during the study.

Data were collected at each study site by a researcher from the same tribal group being studied, a reliable person, or an insider. Due to this, coupled with the use of a standard questionnaire, we can conclude that the local researcher’s positionality was relatively uniform. As a result of the highly dependent agriculture-based local economies, the study respondents were referred to as farmers. Most of our study respondents practiced subsistence farming with a few cultivating cash crops (fruit and nut farming) (Table 1).

To examine differences across the study site, the functional unit applied for analysis was the percentage (%) of respondents per study site. At first, differences in responses within one field study site concerning sex (male/female) were analyzed by a paired t-test; however, the sex factor was not significant due to most of the households being male-headed, and most of the women were married. Therefore, analysis based on sex was not taken into consideration in this study. We examined whether (1) perceiving more climatic changes or (2) household wealth or income status had an influence on the climate change adaptation responses through the application of a mixed-effects model. In every study site, the proportion of perceived climatic changes, impacts, and local adaptation responses from the respondents was calculated. The hierarchical models were applied to examine variability in adaptation responses within and between study sites. To carry out this, a linear mixed-effect model was fitted in the Ime4R package v.1.1-3138. The relationship between adaptation and climatic changes, along with household income or wealth status, was modeled using fixed effects, while the study site was treated as a random effect. Climate changes and household wealth status were allowed to vary among different levels of the random effect. This evaluation is particularly important for wealth since it serves as a relative index for individual study sites, and wealth status tends to vary more significantly within an unequal system. However, it enables variation of observed climate change impacts between study sites. The response variable was based on the proportion of potential adaptations seen in a household (which varies from zero to one). The Gaussian error distribution for the hierarchical model was applied since the response variable was almost normally distributed. The confidence interval for linear model coefficients was derived by parametric bootstrapping.

The households on each site were categorized into three wealth categories (poor, average, and wealthy) based on a wealth index derived from 10 asset measures specific to an individual study site39,40, which were pointed out during the FGDs. The list of assets applied for each study site is in the supplementary information. The assets not owned by over 25% of households were weighted 0.25 times greater than the common assets owned by the households.

Challenges and potential opportunities

During the 12-month research study, we conducted monthly webinars with all co-authors, particularly experienced experts at each study site, to share insights across these locations. In the sixth webinar, we recognized that some challenges identified in one study site could be viewed as opportunities in another. As a result, we shifted our focus to include these opportunities. Initially, the team responsible for each study site applied the information on challenges reported in FGDs to classify each site’s top three major challenges, as described by ref. 16, which includes both physical and economic challenges. Next, we also classified the top three opportunities, based on data collected at the field study sites. It is important to note that although some challenges and opportunities may not appear among the top three in a specific study site, they can still be relevant across different sites. We highlighted the common challenges and opportunities from the 10 study sites within the river basins, especially those frequently mentioned across the sites.

Transformational adaptation to curb climate change impacts

All the team members in charge of the study sites deliberated on the transformational adaptation process at their respective study sites through FGDs and adopted the framework by ref. 17. The framework stipulates five areas or factors that need to be considered, which include (change agents learning through engagement, generalization of pathways, impacts on various sectors and across scales, and the sustainability aspect of change) (see Table 2).

The qualitative assessment of each river basin study site was assigned points along a spectrum from incremental to transformational change. This grading system classifies the sites on a scale from 0, representing only incremental change, to 5, which reflects a highly transformational change. The assessment is based on five factors that indicate the likelihood or unlikelihood of the transformational change process, as outlined in Table 2.

The analytical process offers a chance to characterize transformational change based on assessing the social dynamics and multiple factors, as opposed to deciding on whether the change is transformational or not. The incremental changes are widely known to agglomerate into transformational changes over time. The main key priority areas for advancing transformative climate change adaptation in Africa’s river basins are highlighted in Box 1.

Study limitations

This study presents a comprehensive range of local climate change adaptation responses that could be applied in other major river basins across Africa and worldwide. However, it did not assess the effectiveness or long-term sustainability of the responses, which requires further evaluation, as noted in ref. 18. The study focuses on the impacts of climate change on the livelihoods of local farmers; however, factors such as population growth, advancements in technology, new agricultural policies, social dynamics, and globalization are also influencing small-scale farmers41.

Overall, the climate change adaptation measures adopted by farmers in the river basins tend to be more behavioral than technological or science-based. Farmers who embraced the intensive use of fertilizers were primarily motivated by the desire to enhance land productivity and increase their income, rather than explicitly adapting to climate change. The sustainability of employing chemicals, such as pesticides and herbicides, in conjunction with fertilizers requires further investigation.

It is also important to recognize that climate change is not the sole factor driving rural-to-urban migration. Other interrelated influences, including socio-political, economic, and environmental factors, significantly contribute to this phenomenon28. This study did not identify rural-to-urban migration as a response to climate change adaptation.

Villages were selected based on their accessibility by road. This “main access road” approach may have skewed the results by leading to interviews primarily with wealthier households in Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda. Given that the primary objective of this research was to draw comparisons across study sites rather than within them, we concluded that this aspect did not affect the overall findings. However, future research could delve into household differences within specific study sites.

Data collection at each site was conducted by a researcher from the same tribal group being studied or by a trusted local insider. This consistency, combined with the use of a standardized questionnaire, suggests that the local researcher’s perspective was relatively uniform. The differences in responses within a single field study site based on gender (male/female) were analyzed using a paired t-test. However, the gender factor was found to be non-significant, given that most households were male-headed and many of the women surveyed were married. Consequently, gender analysis was not incorporated into this study.

Therefore, these factors should be taken into account when developing future climate change adaptation measures. To enhance transformational adaptation processes, the study recommends that local and national stakeholders be actively involved in future efforts34.

Ethics statement

This research received approval and support from Tongji University in China. All participants provided their informed consent before the study began. Additionally, local community authorities, including chiefs and village elders, were consulted before commencing the research. This involved explaining the study’s objectives, methodology, and the potential benefits of the research. We adhered to the ethical research guidelines provided by the British Sociological Association when administering the questionnaires and conducting interviews.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Nijsten, G. J. et al. Transboundary aquifers of Africa: Review of the current state of knowledge and progress towards sustainable development and management. J. Hydrol. Regional Stud. 20, 21–34 (2018).

IPCC. Climate Change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Pörtner, H. O. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Thompson, J. R., Crawley, A. & Kingston, D. G. Future river flows and flood extent in the Upper Niger and Inner Niger Delta: GCM-related uncertainty using the CMIP5 ensemble. Hydrol. Sci. J. 14, 2239–2265 (2017).

Descroix, L. et al. Evolution of surface hydrology in the Sahelo-Sudanian Strip: an updated review. Water 6, 748 (2018).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

Dickerson, S., Cannon, M. & O’Neill, B. Climate change risks to human development in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the literature. Clim. Dev. 6, 571–589 (2021).

Adger, W. N. et al. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 112–117 (2013).

IPCC. Summary for policymakers. in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (eds Field, C. B. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

UN. Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) (UN, 2002).

Fedele, G. et al. Transformative adaptation to climate change for sustainable social-ecological systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 101, 116–125 (2019).

Petzold, J. et al. Indigenous knowledge on climate change adaptation: a global evidence map of academic literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 113007 (2020).

Owen, G. What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature. Glob. Environ. Change 62, 102071 (2020).

Klenk, N. et al. Local knowledge in climate adaptation research: moving knowledge frameworks from extraction to co-production. WIREs Clim. Change 8, e475 (2017).

Nakashima, D. et al. Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation (UNESCO, 2012).

Call, M. & Gray, C. Climate anomalies, land degradation, and rural out-migration in Uganda. Popul. Environ. 41, 507–528 (2020).

Castro, B. & Sen, R. Everyday adaptation: theorizing climate change adaptation in daily life. Glob. Environ. Change 75, 102555 (2022).

Henrique, K. P. & Tschakert, P. Everyday limits to adaptation. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2, kgab013 (2022).

Jaspars, S. & Maxwell, D. Food Security and Livelihoods Programming in Conflict: A Review (HPN, 2009).

Bates, D. et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Córdova, A. Methodological Note: Measuring Relative Wealth Using Household Asset Indicators (Vanderbilt University, 2009).

Berman, R. J., Quinn, C. H. & Paavola, J. Identifying drivers of household coping strategies to multiple climatic hazards in Western Uganda: implications for adapting to future climate change. Clim. Dev. 7, 71–84 (2014).

Dawson, N., Martin, A. & Sikor, T. Green revolution in sub-Saharan Africa: implications of imposed innovation for the wellbeing of rural smallholders. World Dev. 78, 204–218 (2016).

Junqueira, A. B. et al. Interactions between climate change and infrastructure projects in changing water resources: an ethnobiological perspective from the Daasanach, Kenya. J. Ethnobiol. 3, 331–348 (2021).

Savo, V. et al. Observations of climate change among subsistence-oriented communities around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 462–473 (2016).

Reyes-García, V. et al. Local indicators of climate change: the potential contribution of local knowledge to climate research. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1, 109–124 (2016).

Reyes-García, V. et al. A collaborative approach to bring insights from local observations of climate change impacts into global climate change research. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 39, 1–8 (2019).

Rao, N. et al. A qualitative comparative analysis of women’s agency and adaptive capacity in climate change hotspots in Asia and Africa. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 964–971 (2019).

Filho, W. L. et al. Introducing experiences from African pastoralist communities to cope with climate change risks, hazards and extremes: fostering poverty reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 101738 (2020).

Filho, W. L. et al. Impacts of climate change to African indigenous communities and examples of adaptation responses. Nat. Commun. 12, 6224 (2021).

Mapfumo, P. et al. Pathways to transformational change in the face of climate impacts: an analytical framework. Clim. Dev. 9, 439–451 (2017).

Berrang-Ford, L. et al. A systematic global stocktake of evidence on human adaptation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 989–1000 (2021).

Reyes-García, V. et al. Local indicators of climate change impacts described by indigenous peoples and local communities: study protocol. PLoS ONE 18, e0279847 (2023).

Salerno, J. et al. Smallholder knowledge of local climate conditions predicts positive on-farm outcomes. Weather Clim. Soc. 14, 671–680 (2022).

Acevedo, M. et al. A scoping review of adoption of climate-resilient crops by small-scale producers in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Plants 10, 1 (2020).

Zickgraf, C. Climate change and migration crisis in Africa. In The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises (eds Menjívar, C., Ruiz, M. & Ness, I.) 347–364 (Oxford Academic, 2019).

Reyes-Garcia, V. et al. Protocol for the collection of cross-cultural comparative data on local indicators of climate change impacts. (2022).

IPCC. Interlinkages between desertification, land degradation, food security and greenhouse gas fluxes: Synergies,trade-offs and integrated response options. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (IPCC, 2019).

Cuni-Sanchez, A. et al. Perceived climate change impacts and adaptation responses in ten African mountain regions. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 153–161 (2025).

IPCC. Climate-Resilient Pathways: adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Barros, V. R. et al.) (IPCC, 2014).

Rosenzweig, C. & Neofotis, P. Detection and attribution of anthropogenic climate change impacts. WIREs Clim. Change 4, 121–150 (2013).

Gaffney, J. et al. Science-based intensive agriculture: Sustainability, food security, and the role of technology. Glob. Food Secur. 23, 236–244 (2019).

Borderon, M. et al. Migration influenced by environmental change in Africa: a systematic review of empirical evidence. Demogr. Res. 41, 491–544 (2019).

Wyborn, C. et al. Co-producing sustainability: reordering the governance of science, policy, and practice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 44, 319–346 (2019).

Chambers, J. M. et al. Six modes of co-production for sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 4, 983–996 (2021).

Karuri, A. N. Adaptation of small-scale tea and coffee farmers in kenya to climate change. In African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation (eds Walter, L. F. et al.) Vol. 1 (Springer, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.N. conceived the study and designed the methodological approach. Data were collected by T.J.N., J.B., Q.J., G.B., and F.L. Data analysis was led by T.J.N. and F.L. The writing of the manuscript was contributed to by all the authors. T.J.N. led the statistical analysis. All co-authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tinega, J.N., Balagizi, J., Jia, Q. et al. Climate change impact and adaptation responses in Africa’s major river basins: increasing resilience through transformative adaptation. npj Clim. Action 4, 119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00311-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00311-9