Abstract

Gridded meteorological datasets—reanalyses and climate simulations—are increasingly central to renewable energy yield assessments, offering complete, physically consistent atmospheric variables required to transform resource data into power output. This review delivers the first holistic synthesis of methodologies and uncertainties across the full modeling chain for both wind and solar energy, from resource characterization to energy yield and bankability metrics. It emphasizes the rising use of long-term, spatially resolved data to improve site selection, financial planning (P50/P90), and climate risk assessment. The review addresses critical modeling steps—vertical extrapolation, air density correction, irradiance decomposition—and quantifies sources of uncertainty inherent in each. By integrating historical and climate-future perspectives, it defines best practices for robust, transparent, and reproducible energy yield assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global transition toward renewable energy is a central pillar of efforts to mitigate climate change and enhance energy security. Wind and solar power, in particular, have witnessed exponential growth in deployment due to technological advancements, policy support, and decreasing costs1. However, these investments are only viable if underpinned by accurate resource assessments that estimate the long-term energy yield of proposed or existing installations. Renewable energy resource assessment is essential for evaluating the technical and economic feasibility of wind or solar farm projects during the development phase2,3. Since wind and solar resources are geographically uneven, effective planning requires understanding where the strongest resources are located, how much is available, when they can be harnessed for electricity generation, and how local constraints—such as land use or regulatory restrictions—may affect project potential (Fig. 1). These questions are typically addressed through statistical analyses that produce standard assessment maps. The process begins with collecting or modeling data on wind speeds, solar irradiance, and other relevant variables, and converting them into expected energy output using simulation tools. Areas unsuitable for development, such as dense urban zones, steep terrain, large water bodies, or protected lands, are excluded from consideration. Conversely, regions offering favorable conditions—such as supportive policies, infrastructure access, or economic incentives—are highlighted. By combining maps of electricity production potential with exclusion criteria, these assessments help identify optimal locations for maximum energy yield.

Schematic diagram of the process for evaluating sites suitable for the installation of renewable energy projects using gridded climate datasets. This review addresses the assessment of the power production potential in the dashed box. Adapted from Drobinski (2025) (in French)149.

From a financial perspective, energy yield estimates influence every stage of project development, including initial feasibility studies, investment attraction, loan structuring, and insurance underwriting. Investors and lenders rely on probabilistic indicators such as P50 (median production) and P90 (production level exceeded with 90% confidence) to assess expected returns and exposure to risk4. These indicators are integral to financial models that determine debt sizing and revenue expectations over the plant’s lifecycle5. An underestimate or overestimate of energy production can lead to significant financial consequences, potentially resulting in underperformance relative to debt obligations or missed investment opportunities.

The energy yield from wind and solar sources is inherently variable and uncertain. For wind energy, key uncertainties arise from interannual variability, turbine performance modeling, wind flow modeling across complex terrains, and extrapolation from measurement heights to hub heights4,6. For solar energy, variability in irradiance due to cloud cover, temperature impacts on photovoltaic (PV) efficiency, and differences in solar radiation datasets all contribute to uncertainty7. Traditionally, on-site measurements over short periods (1–4 years) are extended to longer periods (typically 20 years) using statistical methods such as Measure-Correlate-Predict (MCP)8. However, this introduces risks if the chosen reference period fails to capture the full range of climate variability.

The renewable energy industry increasingly employs long-duration gridded meteorological datasets, commonly known as reanalyses, to supplement or replace direct measurements. These datasets—including global and regional reanalyses are based on assimilating and combining large volumes of historical observations into numerical weather prediction models to reconstruct past atmospheric conditions9,10. Despite limitations in temporal resolution (typically a few hours) and spatial resolution (often tens of kilometers or more), reanalyses offer consistent global coverage and increasingly include energy-specific variables.

In addition to reanalyses, several global wind and solar datasets are produced directly from observational data without the dynamical constraints of numerical weather prediction models. For wind, the global mapping of wind resources demonstrated that observationally derived wind climatologies can provide valuable first-order assessments of global wind power potential11. For solar energy, large satellite-based irradiance datasets such as the NSRDB and the CM-SAF/SARAH products deliver multi-decadal estimates of surface radiation derived from geostationary satellite imagery. These datasets generally offer better representation of cloud-related irradiance variability than reanalyses and have become essential benchmarks for validating climate-model-based or reanalysis-based solar assessments. They complement gridded model products by providing observationally grounded estimates of renewable resources.

Finally, gridded data from climate models are increasingly used for prospective assessments of renewable energy resources under future climate scenarios12,13,14,15. These models support the analysis of long-term trends in wind and solar energy potential as well as the broader impacts on energy markets16. A further development in prospective modeling is the inclusion of both renewable resource availability and end-use energy demand within the same climate-modeling framework17. This ensures meteorological consistency between the weather patterns driving energy production and those driving electricity demand. While gridded datasets offer valuable insights, their outputs are subject to substantial uncertainties arising from natural climate variability, model-specific biases, and differing future emissions pathways.

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the modeling chain used to estimate wind and solar energy yields from gridded climate datasets—spanning from historical reanalyses to future climate simulations. It critically examines each transformation step from resource data to energy output, identifying key sources of uncertainty and evaluating commonly used modeling approaches. Section “Gridded datasets for wind and solar resources assessment” reviews the main gridded datasets used for wind and solar assessments, including reanalyses, satellite-derived products, and climate projections. Section “Translating spatially resolved renewable resource data into energy production estimates” focuses on the physical and statistical models that convert meteorological inputs into energy production estimates, detailing processes such as vertical extrapolation, irradiance decomposition, and air density correction. Section “Probabilistic energy yield estimation” addresses how temporal resolution limitations are managed and how probabilistic metrics like P50 and P90 are derived for financial applications. Finally, Section “Best practices and conclusions” outlines best practices for producing transparent, accurate, and reproducible energy yield estimates, with emphasis on uncertainty quantification, long-term variability, and climate risk integration.

Gridded datasets for wind and solar resources assessment

Gridded meteorological datasets, particularly global and regional reanalyses, have become central to the long-term assessment of wind and solar energy resources. Their increasing use is driven by the variable nature of renewable energy sources and the corresponding need for long and homogeneous time series to support project planning, investment risk analysis, and the calibration or debiasing of climate simulations. Among the most widely utilized are ERA518, MERRA219, CFSR20, and JRA5521, which assimilate large volumes of historical observations into numerical weather prediction models to reconstruct past atmospheric states with temporal consistency and global coverage.

Wind energy applications using reanalyses

ERA5, developed by ECMWF within the Copernicus Climate Change Service, is particularly valued for its hourly temporal resolution, 31 km horizontal resolution, and direct provision of wind speeds at 100 m above ground level—an altitude directly relevant for modern wind turbines. This represents a substantial improvement over its predecessor ERA-Interim (e.g., 6-hourly data, ~79 km resolution) and has positioned ERA5 as the leading reanalysis product in many contemporary wind energy studies22,23. Compared to MERRA2, which offers wind speed data up to 50 m and coarser resolution (~50 km), ERA5 delivers better spatial fidelity and wind speed representation24. The availability of wind data at 100 m is essential as turbine hub heights now commonly exceed 80 m both onshore and offshore25,26,27.

ERA5 has been successfully used to assess wind resources in diverse locations, including North East Scotland28, Lebanon29, Qatar30, South and Southeast Brazil31, the Mediterranean32, the Caspian Sea33, and globally26. Terrestrial applications include sites in Poland34, Ethiopia35, and Colombia36. However, ERA5’s accuracy varies by region and terrain complexity. While it generally performs well in flat or offshore areas37, its performance degrades in mountainous or land-use heterogeneous regions due to under-resolved local acceleration effects25,38. Validation studies, such as those using Vestas mast data38, confirm systematic underestimations in such environments. A known bias in ERA5 is its delayed morning wind speed recovery caused by data assimilation at 1000 UTC37. This affects the diurnal cycle representation and can impact daily energy estimates. Additionally, reanalysis datasets often do not include variables such as air density at turbine hub heights, requiring users to calculate it indirectly using pressure and temperature data, often leading to errors if not properly corrected39. Vertical interpolation between 10 m and 100 m using power laws has been found sufficient for many applications40, although caution is warranted in highly stratified or unstable atmospheric conditions.

To enhance wind resource resolution in areas where global reanalyses underperform, regional reanalyses such as COSMO-REA622,37, COSMO-REA222,41, HARMONIE42, and MESCAN-SURFEX43 offer finer spatial resolutions ( ~ 6 km or better). These datasets are often integrated into regional wind atlases, such as the Global Wind Atlas (GWA). The GWA leverages mesoscale modeling through the WRF (Weather Research and Forecasting) model, dynamically downscaling ERA5 input using high-resolution topography and surface roughness data, and applying microscale modeling with the CFD-based WAsP model to correct for terrain and surface heterogeneities. This hybrid modeling chain enables the GWA to produce wind climatologies at resolutions of 250 m or finer, substantially improving site-specific accuracy over global datasets alone44,45. The Global Wind Atlas thus acts as a bridge between global reanalysis and localized wind resource mapping, offering publicly accessible high-resolution data through an interactive platform. However, like other regional products, its open-access data are often limited to summary layers (e.g., mean wind speed, power density), which can restrict their utility for detailed, time-resolved modeling22. Nevertheless, the GWA remains a valuable tool for preliminary site selection and long-term strategic planning, especially in data-sparse regions.

Wind resource potential modeling frequently involves fitting statistical distributions to wind speed—either historical or synthetic46. The Weibull distribution is widely used in the wind energy sector due to its simplicity and analytical tractability47. Its probability density function is given by

where v is the wind speed, A is the scale parameter and k the shape parameter. However, its use is necessary primarily when only long-term mean wind statistics are available (e.g., annual-average datasets). When high-frequency data (e.g., hourly reanalysis or mast measurements) are available, an empirical wind-speed distribution can be derived directly, making parametric assumptions unnecessary. Nevertheless, Weibull functions remain common in software tools such as WAsP, and bankability assessments, making it easier to communicate results with stakeholders and investors. However, this approach has no strong theoretical foundation and assumes unimodal, isotropic, and circular wind patterns—conditions often violated in complex terrains such as mountainous, forested, or coastal regions48,49. In such cases, the Weibull distribution tends to underestimate both weak and strong winds and overestimate moderate winds, leading to cumulative underestimation of wind energy potential50,51,52. The WAsP method, which emphasizes fitting the distribution to strong winds (more critical for energy production), performs better than general fitting approaches, which tend to match the entire distribution and may poorly capture the production-driving extremes53. Even then, reliance on a Weibull model, especially with limited parameters, can lead to systematic underestimation or overestimation depending on site conditions. Alternative distributions such as bimodal Weibull54,55, elliptical, Rayleigh-Rice49, or non-Gaussian formulations have been proposed to better model such complex wind regimes. These approaches improve accuracy, especially in areas with anisotropic winds, although they require more detailed input data and calibration. The limitations of parametric models such as the Weibull distribution—especially its inability to capture multimodality—have prompted the exploration of non-parametric approaches, such as the quantile-quantile techniques, or similar such as CDF-t56.

Solar energy applications using reanalyses

In the solar domain, similar limitations and opportunities apply. While reanalyses like ERA5 and MERRA2 provide useful irradiance estimates, satellite-derived datasets are generally more accurate, especially in capturing cloud variability and atmospheric transmittance. Products such as SARAH57, CM-SAF58, and NSRDB59 outperform reanalyses in estimating global horizontal irradiance (GHI), particularly in cloud-prone or convective regions. Tools like PVGIS60,61 and renewables.ninja62 integrate these datasets to produce multi-year PV output estimates across global domains. However, validation of modeled PV performance remains predominantly limited to European case studies63,64,65.

ERA5 has shown significant improvement over earlier reanalyses, with global mean biases in irradiance reduced by 50–75%64, and strong performance observed in Australia66 and the Mediterranean region67. Still, biases persist in regions like Asia68,69, Norway70, and Brazil71. ERA5-Land, introduced in 2019 with 9 km horizontal resolution, offers some refinement, though studies indicate that gains over MERRA2 are modest in many cases72.

To address spatial limitations and promote energy access planning, the Global Solar Atlas (GSA) provides high-resolution solar resource data (250–1000 m) derived from satellite imagery processed through the Solargis model chain, which incorporates cloud and aerosol observations, radiative transfer models, and terrain corrections to calculate the global horizontal irradiance, the direct normal irradiance, and PV output potential. Its methodology ensures consistency with ground measurements via site-specific bias corrections and temporal averaging of up to 20 years of data73. Unlike typical reanalysis-based platforms, the GSA offers open-access data suitable for feasibility screening, electrification planning, and early-stage project development, particularly in data-sparse developing regions. Although the GSA primarily provides climatological summaries, its spatial resolution and bias-adjusted modeling make it a reliable reference for solar development, especially where direct ground validation is limited. As with the Global Wind Atlas, access to high-resolution, quality-assured data through the GSA significantly enhances decision-making and early resource screening across the solar energy sector.

Renewable energy resource projections in future climate

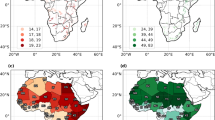

As renewable energy planning increasingly incorporates long-term horizons, climate projections have become essential tools for evaluating how wind and solar resources may evolve over future decades. In contrast to reanalyses—which provide high-resolution, observation-informed reconstructions of past atmospheric conditions at hourly to sub-daily intervals—climate projections are forward-looking simulations driven by scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions, land-use change, and other external forcings. These projections, produced through initiatives like CMIP and CORDEX, offer multi-model ensembles that capture a range of plausible climate futures. However, they typically operate at coarser spatial and temporal resolutions—often providing monthly or daily outputs such as temperature, wind speed, and irradiance, over 30-year climatological periods—limiting their ability to resolve short-term variability or fine-scale geographic features. Nonetheless, they are crucial for assessing long-term trends, variability, and extremes in renewable energy potential under different climate scenarios. Gridded climate change projections, derived from general circulation models (GCMs) and downscaled through either regional climate models (RCMs) or statistical techniques, have been increasingly applied to assess the potential impacts of climate change on solar and wind energy resources. Dynamical downscaling involves nesting high-resolution RCMs within GCMs, enabling better representation of orography, land-sea contrasts, and localized weather patterns. Projects such as CORDEX provide ensembles of such simulations at 50 km or finer resolution74,75. Studies on wind energy change in anthropogenic scenarios have been conducted using both downscaling approaches for regions such as Europe and North America56,76,77,78,79,80,81, suggesting that projected changes in mean wind speeds and energy density are modest—often less than 10 percent—and generally within the bounds of natural interannual variability77,82. In addition to average conditions, gridded climate projections have also been employed to explore potential changes in wind speed variability and extreme wind events for turbine design and load calculations76,79,83. However, these extremes are inherently rare, and their quantification remains a significant modeling challenge due to the limited ability of current tools to accurately simulate such events84,85. Similar approaches have been used to investigate the impact of climate change on solar radiation, a major driver of solar energy86,87,88.

Translating spatially resolved renewable resource data into energy production estimates

Translating gridded meteorological data from reanalyses or climate model outputs into renewable energy production estimates involves applying a series of physical and statistical models that convert resource variables—such as wind speed, solar irradiance, temperature, and pressure—into spatially resolved power output (Fig. 2). These datasets typically provide all the necessary atmospheric variables to support this transformation which has been used in assessment studies using reanalyses79,89 or in wind energy prospective13,15, solar energy prospective90 or both14,91 using climate projections. The resulting energy production estimates serve as the foundation for deriving probabilistic indicators such as P50 and P90, which are critical for project bankability and risk assessment. However, each step in this modeling chain introduces uncertainties that must be carefully quantified and, where possible, mitigated.

Wind energy production modeling

Converting wind energy resource data into wind power output requires several key modeling steps to account for physical and technical factors that influence turbine performance (Fig. 2a). First, vertical extrapolation is necessary because gridded reanalyses and climate simulations rarely provide wind speed data exactly at the turbine hub height, which typically ranges between 80 and 120 meters. Second, air density correction must be applied, as power output depends not only on wind speed but also on air mass; however, this step is frequently overlooked despite its significant influence, especially in regions with notable temperature or elevation variability. Finally, wind speed is mapped to power output using the turbine’s power curve, a nonlinear relationship that defines how much electricity is produced at different wind speeds. Each of these steps introduces uncertainties that propagate through the modeling chain and must be carefully considered when estimating energy yield.

Vertical extrapolation of wind speeds

In wind energy assessments, wind speed from gridded datasets often needs to be extrapolated from lower elevations—such as 10 m or 50 m—to typical wind turbine hub heights, which range from 80 to 120 m. Two main methods are widely employed for vertical extrapolation: the logarithmic law and the power law. The logarithmic law, derived from boundary layer theory, is theoretically valid under neutral atmospheric conditions and is expressed as

where z is the height, κ = 0.4 is the Von Karman constant, v∗ is the friction velocity and z0 the surface roughness length, both assumed altitude-independent92. When measurements are available at two levels, roughness length can be estimated by rearranging this equation, and then wind speed at a target height can be calculated. However, in reality, thermal stratification is rarely neutral, and generalizing this approach to non-neutral conditions requires knowledge of the Monin-Obukhov length, which is often difficult to determine in practice. Furthermore, as turbine hub heights increase, they may extend beyond the surface layer, reducing the validity of surface-based extrapolation methods92. The empirical power law, often preferred for its simplicity, is commonly expressed as

where vref is the wind speed at a reference level zref where it is generally available in gridded datasets (i.e. most often at zref = 10 m). The exponent α, referred as wind shear coefficient, typically ranges from 0.1 to 0.4, reflecting the impacts of atmospheric stability and surface roughness. The α standard value of 1/7 (or 0.14) is, however, frequently used in wind atlases and climate analyses when only a single height measurement is available15,93. Calibration of α is generally performed on average wind profiles, often categorized by wind direction, season, or time of day. Though convenient, using a constant α can introduce errors exceeding 10% when actual stratification deviates from neutral conditions40. Therefore, more complex expressions exist, which are more difficult to calibrate94. Methods have been developed to calculate the exponent α from the parameters in the logarithmic law. For example, expression of α as a function of vref and z0 such as95

or incorporating z0 only with stability dependent coefficients, such as96

have been proposed. However, these complicated approximations reduced the simplicity and applicability of the general power law, so empirical expression of α best fitting the available wind data has also been proposed, such as97

Studies have shown that the vertical wind gradient, and therefore α, varies significantly on diurnal and seasonal timescales40,98. These differences reflect the underlying atmospheric dynamics: stable nocturnal conditions typically result in stronger wind gradients, while daytime instability fosters vertical mixing that flattens the profile99.

To address these complexities, more advanced methods have been developed, including time-varying α values derived from multi-level measurements or machine learning models trained on meteorological variables. While such approaches can improve accuracy— halving root-mean square error in some cases for 20 m extrapolations—they require dense datasets, which are not always available94. The European Wind Energy Association (EWEA) has concluded that extrapolation introduces limited errors when the height difference is small (e.g., 20 m), but becomes increasingly problematic with larger gaps, such as extrapolating from 10 or 40 m up to 80 or 90 m100,101. Indeed, root-mean square error increases from around 4% for a 20 m extrapolation to over 12% for a 60 m extrapolation, with biases as high as −5% for power law methods40. Efforts to reduce extrapolation errors through data stratification—by time of day, season, or wind direction—offer marginal improvements (reduction in the root-mean square error by less than -15%). The most significant gains occur when profiles are calibrated at hourly resolution, nearly halving the root-mean square error compared to using an annual average profile. However, when gridded datasets provide wind speeds at two or more vertical levels (e.g., 10 m and 100 m in ERA5), wind speeds at intermediate heights can be interpolated using logarithmic or polynomial vertical profiles. This avoids purely extrapolating from a single low-level measurement and typically reduces uncertainty relative to single-level methods.

Conversion to power and air density correction modeling

The conversion of wind speed to wind power is nonlinear and turbine-specific, governed by a power curve P(v) supplied by turbine manufacturers102. This curve relates wind speed to power output and includes cut-in, rated, and cut-out thresholds. The power production over a time period T is given by83:

where p(v) is the probability distribution of hub-height wind speeds. Converting wind speed to wind power is an area of research that is still very active103,104,105. Errors in wind power estimates can range from a few percent to over 50%, depending on the method used to model the power curve106,107—for example, whether a parametric or non-parametric approach is employed104. Combining Weibull distributions with nonlinear power curves has been shown to increase estimation errors, with studies reporting 5–10% average underestimations—and larger errors at sites with bimodal wind regimes50,51.

However, the energy performance of a wind turbine depends more largely on the atmospheric conditions and in particular on the density of the air, which depends on air temperature T and pressure P through the perfect gas law, P = ρRT, where ρ is the air density and R the perfect gas constant. Most studies neglect the impact of air density, as power curves are calibrated for standard air density (1.225 kg/m³)108, even if this impact is not negligible. Deviations due to temperature, pressure, and altitude can lead to errors if uncorrected27,39. The root-mean square error between the calculated and measured power maybe reduced by 20% when the temperature is used as input of the modeled wind power109. However, the error can vary by more than 200% when different methods to account for air density are applied105. An accurate estimate of air density is a prerequisite for reducing uncertainty in wind energy assessment. To introduce the air density correction (temperature, pressure and altitude effect) while using the power curves determined in standard atmospheric conditions, the wind speed must be corrected by multiplying it by the factor (ρ/ρ0)1/3 110:

Correcting the temperature and the pressure for the altitude of the hub of the windturbine using a standard atmosphere can easily be applied to gridded reanalyses or climate simulations39, with

The relative errors are the strongest in atmospheric conditions different from the standard atmosphere with temperatures above 25°C or below 5°C, while the pressure effect operates at a lower order39. This method has demonstrated a reduction in power estimation error by up to 6.5% in real-world datasets.

A further source of uncertainty—often overlooked when using gridded reanalyses or climate simulations—is the reduction in wind power availability arising from turbine–turbine and farm–scale interactions. Wind turbines extract kinetic energy from the atmosphere, creating wakes that slow down the downwind flow and reduce power production in downstream turbines. At large scales, very extensive wind farms may also reduce regional wind speeds due to the cumulative drag imposed on the boundary layer111. Global simulations that explicitly represent wind turbine drag show that this effect can modestly decrease large-scale wind speeds112. Because most reanalyses and climate models do not incorporate these feedbacks, energy yield assessments based solely on their wind fields may slightly overestimate resource availability, particularly for densely clustered wind developments.

Solar energy production modeling

Modeling the PV power consists in, first, calculating the solar global in-plane irradiance (I) and PV cell operating temperature (Tcell), and then, using a PV performance model, calculating the power produced at the maximum power point (PPV) (Fig. 2b). Uncertainties associated with modeling photovoltaic (PV) producible fall into three main categories: the estimation of temperature-induced efficiency losses, the modeling of diffuse and direct irradiance in energy output calculations, and the representation of sub-daily variability in PV production.

Modeling of solar producible

The most straightforward modeling approach accounts only for temperature-related losses, without explicitly modeling producible energy. This efficiency loss depends on the cell temperature Tcell, which can be estimated using the expression:

In this formulation, Tday is the average daytime air temperature, calculated as the mean of daily maximum and minimum temperatures113. The coefficient a, representing solar absorption, is commonly set to 0.9 (ranging between 0.75 and 1 in the literature114,115), while the heat loss factor U is taken as 29 W m⁻² K⁻¹ (ranging between 14 and 42 W m⁻² K⁻¹ in the literature114)—both standard values used in the PV technology modeling platforms such as PVsyst and PVGIS116,117. The quantity Iday is the daily global horizontal irradiance. This formulation has been employed in many applications89. To improve accuracy, this model can be expanded to include wind effects on heat dissipation. In such cases, the heat loss coefficient U is redefined as a function of wind speed: \(U={U}_{c}+{U}_{v}\bar{v}\) with Uc a constant and Uv, the heat loss coefficient associated with the wind speed. This yields a more refined empirical relationship118:

Here, T(t) is the near-surface air temperature at 2 meters, I(t) is incoming shortwave radiation at the surface, and v(t) is wind speed at 10 meters. The coefficients are c1 = 4.3 °C, c2 = 0.943, c3 = 0.028 °C m2 W−1 and c4 = −1.528°C sm−1. These variables are available in gridded climate datasets and numerical simulations. Empirical studies show that crystalline silicon PV efficiency decreases by approximately 0.3–0.6% per °C increase in cell temperature relative to standard test conditions60,119,120,121,122,123,124 but this relative reduction can exceed 0.6% per °C for cell temperature exceeding 50°C123.

Once cell temperature is estimated, converting irradiance to PV power output is relatively straightforward. The potential PV energy output, PPV(t), is given as119

where I(t) is the instantaneous irradiance ISTC = 1000 W m−2 is the irradiance under standard test conditions (STC), used for calibrating PV module capacities, and η is the module’s electrical efficiency at the reference cell temperature TSTC under STC. For TSTC = 25°C, the efficiency η ranges typically between 5% and 18% depending on the technology with on average, highest values for monocrystalline silicon115,119,124.

The performance ratio PR(t) accounts for efficiency losses due to temperature and is expressed as

In this equation, γ is the thermal response coefficient of the PV technology. A typical value is 0.45–0.5% per °C with observed extremes ranging from 0. 11% per °C to 0.98% per °C115,119,123,125. Given the broad range of PV technologies, using validated simulation tools and datasets is advisable. Platforms such as PVsyst and PVGIS offer reliable, user-friendly environments for modeling a variety of PV technologies under different climatic conditions. In the absence of detailed system specifications, a default assumption is that crystalline silicon panels dominate the global PV market, accounting for approximately 95% of installations, with monocrystalline silicon-based solar cells replacing the multicrystalline silicon-based solar cells as the technology dominating the market126,127. These prevalence figures can guide the choice of representative coefficients for modeling purposes when project-specific data are unavailable.

Modeling of direct and diffuse radiation and total incident radiation on the PV panel

To compute global solar irradiance on the plane of a photovoltaic (PV) panel, several inputs are typically required: global horizontal irradiance (GHI), diffuse horizontal irradiance, direct normal irradiance, the panel’s tilt angle, and occasionally the local ground albedo. In systems with sun-tracking capabilities—whether single-axis or dual-axis—the angle of inclination can vary throughout the day to maximize energy capture. In many climate reanalysis datasets or simulations, however, only global horizontal irradiance is provided. As a result, it is often used directly in PV production models, including those estimating PV cell temperature (Fig. 2b). While this approach is common, a more accurate method involves decomposing the GHI into its diffuse and direct components before projecting onto the inclined plane. This improves both the estimation of cell temperature and the producible PV energy. Several models exist to derive these components from horizontal irradiance and to calculate the total irradiance incident on an inclined surface.

A widely used approach correlates the ratio of diffuse to total irradiance, Id/I, with the clearness index, kT, defined as the ratio of observed global irradiance I to extraterrestrial irradiance I0 (about 1361 W m−2)128 on a horizontal plane. One of the reference models is that of Erbs et al.129:

The model proposed by Orgill and Hollands130, also widely used and similar in outcome, is defined by

A recent comparison shows that the Helbig et al.131 model outperforms the Erbs et al.128 model in certain contexts7. It is defined by

with \({\theta }_{z}\) the solar zenith angle.

For daily (or monthly) values, hereafter referred as Id,day and Iday, similar correlations exist. Erbs et al.128 proposed

for sunset hour angles less than or equal to 81.4°, and:

for sunset hour angles greater than 81.4°. Another widely cited model is that of Collares-Pereira and Rabl132

Once the direct and diffuse components are obtained, the next challenge is to compute the radiation on an inclined surface based on values measured on a horizontal surface. This requires knowing the angular distribution of radiation components. The total irradiance IT incident on a tilted surface can be expressed as

where the terms represent contributions from direct beam, isotropic diffuse, circumsolar diffuse, horizontal diffuse, and reflected radiation from the ground, respectively. Many models exist to compute these terms, ranging from simple to highly complex113. The isotropic sky model assumes uniform solar radiance across the entire sky dome and performs well under fully overcast conditions133. The classic Liu and Jordan model uses this approach and expresses the irradiance on a tilted surface as134

where ψ is the angle between the solar direction and the panel’s normal, and ε is the tilt angle of the surface. More advanced models extend this by introducing anisotropy and better accounting for clear-sky conditions135:

Klucher136 developed an “all-sky” anisotropic model that smoothly transitions between overcast and clear-sky conditions using a modulation function:

where F = 1-(Id/I)2 modulates the transition. Under overcast skies, F = 0, and the model reduces to the isotropic case. Under clear skies, F ≈ 1, and the model approximates the Temps and Coulson anisotropic formulation135. In a climate modeling context, the Klucher model136 was applied to reanalysis irradiance data from CORDEX and MERRA-2 at each grid point89. There, the partitioning between global and diffuse radiation is determined using the daily clearness index kT,day and the solar elevation angle. The clearness index for a given day is defined as kT,day = Iday / I0,day, where I0,day is the daily extraterrestrial radiation.

Finally, as for wind energy, some global climate model-based gridded datasets also incorporate the feedback loop between solar energy extraction and surface temperatures112 but most do not, enhancing the level of uncertainty.

Dealing with temporal resolution limitations

The temporal resolution of gridded climate datasets plays a critical role in accurately modeling renewable energy yields, as their native time steps directly influence how well variability and extremes in wind and solar resources are captured throughout the modeling chain. For wind energy, the nonlinear nature of the turbine power curve makes it particularly sensitive to data averaging. Relying on daily-averaged wind speeds rather than hourly data can lead to underestimations of energy potential by 5–15%53. To mitigate this, studies have used parametric distributions like the Rayleigh distribution to simulate intra-daily wind variability and estimate energy production when only coarse-resolution data are available, such as those from CMIP or CORDEX climate models89.

For solar energy, the relationship between temperature and PV producible is linear, which reduces sensitivity to temporal averaging. However, much of the variance in PV output stems from the diurnal cycle of irradiance on tilted surfaces. As such, accounting for hourly variability remains important for confidence in PV modeling. Unlike reanalysis datasets such as MERRA-2 or ERA5, which offer fairly high temporal resolution, most climate simulations—such as those from the CMIP or CORDEX ensembles—may only provide daily-mean irradiance values at the surface and at the top of the atmosphere. To reconstruct diurnal variability, hourly extraterrestrial irradiance at the top of the atmosphere, I0(t), is computed using calendar and solar geometry data, and the hourly surface irradiance I(t) is approximated by multiplying I0(t) by the daily clearness index kT,day, assumed to remain constant throughout the day, i.e. I(t) = kT,day I0(t)89. While this method captures the shape of the daily irradiance curve, it does not account for intra-day fluctuations in kT, such as those caused by transient cloud cover. The uncertainty associated with this daily-to-hourly approximation has not yet been fully characterized in the literature.

Probabilistic energy yield estimation

Once the gridded climate variables converted into energy production estimates, the resulting time series at each grid point are used to derive probabilistic indicators critical for financial planning—namely P50, P75, P90, and P99. These metrics represent the annual energy production levels expected to be exceeded with respective probabilities and are fundamental to assessing investment risk and structuring project finance. Their calculation typically assumes that annual net production values follow a normal distribution, with the mean corresponding to P50 and the standard deviation σ used to compute the desired quantiles4,137,138:

where x = 84, 90, or 95 and erf is the error function and erf-1 its inverse. The larger the difference between P90 (or other quantiles x) and P50, the larger the distribution and the more uncertain the energy estimate. The accuracy and the precision of the pre-construction energy estimates can dictate the profitability of the wind or solar project.

The main sources of uncertainty in long-term wind and solar energy yield predictions, and needed to estimate σ, stem from two broad areas. The variability and estimation of the resource, and uncertainties in system performance parameters139,140. Specifically, wind and solar resource uncertainties include year-to-year climate variability and errors from transposition models described in Section “Translating spatially resolved renewable resource data into energy production estimates”.

On the system side, for wind energy yield, uncertainties come from production losses due to wake effects, availability, curtailment, turbine performance, environmental and electrical losses. Experts have been dedicated to eliminating such prediction errors in the past decade141. Recently the reported average energy prediction bias is declining140, as wind energy yield assessment process include accounting for additional factors in wind resource assessment and operation, accounting for meteorological effects on power production, improving modeling and measurement techniques and correcting for previous methodology shortcomings. For solar energy yield, uncertainties arise from inaccuracies in module power ratings, degradation over time, dirt and soiling, snow cover, system availability, and other losses such as inverter inefficiencies and modeling limitations139,142,143. Each of these contributes variably to the total uncertainty, which was found to be around 8%.

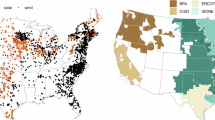

However, one key issue that gridded realayses or climate simulations can overcome for both solar and wind energy yield estimation is the uncertainty caused by the period over which the assessment is conducted. Twenty-year average values are less uncertain than one-year values because the variability inherent in one-year values is averaged over the long term. Industry practice typically relies on around ten years of data to assess wind and solar resources, yet natural variability is driven by atmospheric processes operating on both high and low frequencies. These low-frequency fluctuations—often referred to as climate oscillations—are characterized by persistent spatial patterns, usually spanning ocean basins, and time series that describe their amplitude and phase. Fig. 3a illustrates the cumulative density function of the ratio of actual to estimated production for 139 U.S. wind farms between 2001 and 2009. On average, actual P50 values are 7% lower than those estimated during site assessments. The interannual to decadal variability of low-level wind speed in North America from 1950 to 2010 is significantly negatively correlated with the large body of warm water in the Western Pacific, called the Western Hemisphere Warm Pool (WHWP)144. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, strong WHWP activity lead to notably reduced regional wind speeds, whereas weaker WHWP years before corresponded with increased wind speeds (Fig. 3b). If other sources explain the overestimation of P50 such as curtailment145, the length of the assessment period is key for reducing bias on P50 estimate, as the interannual variability of the historical wind resource can lead to 1–7% uncertainty on the wind energy yield144. Similar discrepancies have been observed in Europe146 as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) plays a major role in shaping winter wind variability regionally, raising concerns about the financial viability of wind projects and the risk of deterring future investments40. Similar impact of regional climate variability can affect solar PV energy yield. Fig. 3c is similar for a PV farm in Canada between 1974 and 1989139. On average, actual P50 values are 3% higher than the P50 value estimated over 1964-1973 period. As for wind speed, solar radiation is subject to interannual to decadal variability. Studies point to a downward trend or dimming from the 1950s to the mid 1980s, followed by an upward or brightening trend in many locations147. The low-frequency variability of surface radiation in North America is closely linked to the Decadal Pacific Oscillation (DPO)148. The DPO is a long-term pattern of sea surface temperature variability in the Pacific Ocean, typically fluctuating between warm and cool phases over periods of 10 to 30 years (Fig. 3d). It influences large-scale atmospheric circulation and climate patterns across the Pacific basin and adjacent continents, including North America. During the positive phase of the DPO, there is a decrease in surface radiation across much of North America, while the negative phase corresponds with increased surface radiation. This relationship is primarily attributed to changes in cloud cover and atmospheric circulation patterns driven by DPO-related sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific.

Cumulative density function of the ratio of the wind (a) and solar (b) energy yield (P50) (2001 to 2013 for wind energy yield; 1974 to 1989 for solar energy yield), to that estimated on previous assessment period (unknown pre-construction assessment period for estimated wind energy yield; 1964 to 1973 for solar energy yield). c Western Hemisphere Warm Poll (WHWP) index (c) and Decadal Pacific Oscillation (DPO) index (d) as a function of time. The red bars, resp. blue bars, correspond to the positive phase, resp. negative phase, of the WHWP and DPO. Data sources: DNV GL (2014) for wind energy yield148; Thevenard and Pelland (2013) for solar energy yield142; NOAA website noaa.gov for WHWP and DPO indices.

So, a robust strategy to assess wind or solar energy yields involves generating energy production time series from long-term gridded datasets (typically spanning 20 years or more) and fitting empirical distributions directly to these data—an approach that helps minimize the risk of bias in P50 estimates and reduces the likelihood of mismatch between predicted and actual performance, which is critical for financial risk management and investor confidence.

Best practices and conclusions

Accurate and robust renewable energy assessments depend not only on the availability of gridded meteorological datasets but also on careful methodological choices throughout the modeling chain. The use of reanalyses and climate simulations offers a consistent, spatially and temporally resolved basis for estimating wind and solar energy potential. However, these datasets must be selected, processed, and interpreted with attention to their limitations and the specific requirements of energy modeling.

A first best practice concerns the selection and validation of datasets. Reanalyses such as ERA5 and MERRA-2 provide extensive temporal coverage and contain variables relevant to energy applications, including wind speed at turbine hub height and surface irradiance. For solar applications, satellite-derived datasets like SARAH or the Global Solar Atlas often yield more accurate irradiance estimates, particularly in regions with complex cloud dynamics. Regardless of the source, it is essential to validate model outputs against local ground-based measurements when available. This step helps identify and correct for systematic biases, especially in areas with complex terrain or atmospheric conditions.

Modeling energy production from climate variables requires translating atmospheric parameters into electrical output, a process that introduces several layers of uncertainty. In wind energy modeling, vertical extrapolation from standard data levels to turbine hub height must be handled with care, ideally incorporating site-specific information on atmospheric stability and surface roughness. Air density corrections are also critical, as neglecting the influence of temperature and pressure variations can lead to significant under- or overestimation of energy output. Similarly, for solar energy assessments, modeling must consider both the transformation of horizontal irradiance into panel-plane irradiance and the thermal behavior of PV modules. Temperature-dependent losses and performance ratio adjustments are necessary to accurately reflect real-world production.

Temporal resolution plays a key role in minimizing errors in energy yield estimation. Hourly data allow better representation of the nonlinear response of wind turbines to wind speed and capture the diurnal variability of solar irradiance more effectively than daily averages. When only daily data are available—such as in many climate model outputs—temporal disaggregation techniques can be applied, but these introduce additional uncertainty that must be acknowledged in the final estimates.

A fundamental aspect of best practice is the explicit quantification and communication of uncertainty. Rather than relying on parametric assumptions like normality, empirical distributions should be derived from long-term energy production time series. Using datasets with 20 or more years of data allows a more reliable estimation of P50, P90, and other probabilistic indicators that are critical for financing decisions. Uncertainty arises from a combination of resource variability, model assumptions, and technical losses, and must be accounted for across all modeling stages. Furthermore, interannual to decadal climate variability—linked to large-scale modes—can significantly influence wind and solar production. Short-term assessments are unlikely to capture these fluctuations and may lead to biased estimates of long-term energy yield.

Incorporating projections of future climate change requires additional care. Downscaling methods—either statistical or dynamical—should be employed to improve the spatial and temporal resolution of global climate models, and their assumptions must be clearly stated and tested against observations. Ensemble approaches that combine results from multiple models and scenarios are essential to capture the range of plausible futures and to avoid over-reliance on any single simulation. Yield metrics should be calculated separately for each member before aggregation to preserve meaningful estimates of spread and central tendency.

Ultimately, the credibility and usefulness of renewable energy assessments depend not only on technical rigor but also on integration into financial and policy frameworks. Hybrid approaches that combine reanalysis, satellite, and in situ data enhance confidence in yield estimates and are particularly valuable in data-sparse regions. Ensemble modeling and probabilistic output should be directly incorporated into financial risk assessments, supporting more resilient investment strategies. Policymakers and regulators can foster best practices by mandating the use of validated datasets, supporting transparency in modeling approaches, and promoting access to high-resolution climate and energy data. Investments in training, standardized tools, and open-access platforms will further empower stakeholders to make informed decisions.

Looking ahead, the integration of gridded meteorological datasets into renewable energy assessment is poised to deepen as both the energy sector and climate science evolve. Emerging reanalyses with finer spatial scales and enhanced data assimilation will help bridge current gaps in representing complex terrain, coastal processes, and cloud dynamics, thereby reducing uncertainties that remain persistent in wind and solar yield modeling. Parallel advances in satellite missions—particularly those resolving aerosol–cloud interactions and land–atmosphere coupling—offer the prospect of improved irradiance estimates and better harmonization between observational and model-based products.

Another major direction concerns the coupling of energy system modeling with physically consistent climate projections. As long-term planning increasingly accounts for climate risk, yield assessments will need to incorporate multi-model ensembles, explicit representation of low-frequency variability, and bias-aware downscaling methods that maintain the coherence between meteorological drivers of both energy production and energy demand. Future work should also address feedbacks of large-scale renewable deployment on the atmosphere, which current gridded datasets typically omit but may become non-negligible in regions of high wind or solar penetration.

Methodological innovations are equally important. Hybrid frameworks that fuse reanalysis, satellite data, machine-learning emulators, and sparse in situ observations hold promise for operationalizing uncertainty quantification and delivering more resilient P50/P90 indicators. As the industry shifts toward real-time monitoring and adaptive forecasting, the boundary between “resource assessment” and “resource management” will continue to blur, encouraging modeling approaches that are dynamic rather than strictly pre-construction focused.

Finally, as open-access platforms and standardized tools proliferate, community-driven benchmarking and reproducibility standards will become central to ensuring trust in energy-yield calculations. Strengthening these shared infrastructures will be essential not only for project development but also for fostering equitable access to high-quality renewable resource information in regions where measurement networks remain sparse.

In conclusion, the reliable assessment of renewable energy potential using gridded datasets requires coordinated attention to data quality, modeling methodology, uncertainty treatment, and communication. By adopting these best practices, energy developers, researchers, and decision-makers can enhance the credibility of their assessments and reduce financial risk.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Hassan, Q. et al. A comprehensive review of international renewable energy growth. Energy and Built Environment, in press https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbenv.2023.12.002 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Ren, J., Pu, Y. & Wang, P. Solar energy potential assessment: a framework to integrate geographic, technological, and economic indices for a potential analysis. Renew. Energy 149, 577–586 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. A multi-criteria methodology for wind energy resource assessment and development at an intercontinental level: Facing low-carbon energy transition. IET Renew. Power Gener. 17, 480–494 (2023).

Clifton, A., Smith A. & Fields, M. Wind plant preconstruction energy estimates: current practice and opportunities. Technical report, NREL/TP-5000-64735, 72 (2016).

Raikar, S. & Adamson S. Renewable Energy Finance: Theory and Practice 298 (Academic Press, 2019).

Mora, E. B., Spelling, J., van der Weijde, A. H. & Pavageau, E. M. The effects of mean wind speed uncertainty on project finance debt sizing for offshore wind farms. Appl. Energy 252, 113419 (2019).

Migan-Dubois, A., Badosa, J., Bourdin, V., Torres Aguilar, M. I. & Bonnassieux, Y. Estimation of the uncertainty due to each step of simulating the photovoltaic conversion under real operating conditions. Int. J. Photoenergy 2021, 4228658 (2021).

Carta, J. A., Velázquez, S. & Cabrera, P. A review of measure-correlate-predict (MCP) methods used to estimate long-term wind characteristics at a target site. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 27, 362–400 (2013).

Gualtieri, G. Reliability of ERA5 Reanalysis data for wind resource assessment: a comparison against tall towers. Energies 14, 4169 (2021).

Victoria, M. & Andresen, G. B. Using validated reanalysis data to investigate the impact of the PV system configurations at high penetration levels in European countries. Prog. Photovolt. 27, 576–592 (2019).

Archer, C. L. & Jacobson, M. Z. Evaluation of global wind power. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D12110 (2005).

Tobin, I. et al. Assessing climate change impacts on European wind energy from ENSEMBLES high-resolution climate projections. Clim. Change 128, 99–112 (2015).

Tobin, I. et al. Climate change impacts on the power generation potential of a European mid-century wind farms scenario. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 34013 (2016).

Tobin, I. et al. Vulnerabilities and resilience of European power generation to 1.5°C, 2°C and 3°C warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 44024 (2018).

Cai, Y. & Bréon, F. M. Wind power potential and intermittency issues in the context of climate change. Energy Convers. Manag. 240, 114276 (2021).

Alonzo, B., Concettini, S., Creti, A., Drobinski, P. & Tankov, P. Profitability and revenue uncertainty of wind farms in Western Europe in present and future climate. Energies 15, 6446 (2022).

Jacobson, M. Z. On the correlation between building heat demand and wind energy supply and how it helps to avoid blackouts. Smart Energy 1, 100009 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J. Clim. 27, 2185–2208 (2014).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 93, 5–48 (2015).

Camargo, L. R., Gruber, K. & Nitsch, F. Assessing variables of regional reanalysis data sets relevant for modelling small-scale renewable energy systems. Renew. Energy 133, 1468–1478 (2019).

Rapella, L., Faranda, D., Gaetani, M., Drobinski, P. & Ginesta, M. Climate change on extreme winds already affects off-shore wind power availability in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 18 034040 (2023).

Olauson, J. ERA5: The new champion of wind power modelling? Renew. Energy 126, 322–331 (2018).

Gualtieri, G. Improving investigation of wind turbine optimal site matching through the self-organizing maps. Energy Convers. Manag. 143, 295–311 (2017).

Soares, P. M., Lima, D. C. & Nogueira, M. Global offshore wind energy resources using the new ERA-5 reanalysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 1040a2 (2020).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J., Bukovsky, M. S., Leung, L. R. & Sakaguchi, K. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 627–643 (2020).

Ulazia, A., Nafarrate, A., Ibarra-Berastegi, G., Sáenz, J. & Carreno-Madinabeitia, S. The consequences of air density variations over Northeastern Scotland for offshore wind energy potential. Energies 12, 2635 (2019).

Ibarra-Berastegi, G., Ulazia, A., Saénz, J. & González-Rojí, S. J. Evaluation of Lebanon’s offshore-wind-energy potential. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 7, 361 (2019).

Aboobacker, V. M. et al. Long-term assessment of onshore and offshore wind energy potentials of Qatar. Energies 14, 1178 (2021).

Tavares, L. F. D. et al. Assessment of the offshore wind technical potential for the Brazilian Southeast and South regions. Energy 196, 117097 (2020).

Soukissian, T. H., Karathanasi, F. E. & Zaragkas, D. K. Exploiting offshore wind and solar resources in the Mediterranean using ERA5 reanalysis data. Energy Convers. Manag. 237, 114092 (2021).

Farjami, H. & Hesari, A. R. E. Assessment of sea surface wind field pattern over the Caspian Sea using EOF analysis. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 35, 101254 (2020).

Jurasz, J., Mikulik, J., Dabek, P. B., Guezgouz, M. & Kazmierczak, B. Complementarity and ‘resource droughts’ of solar and wind energy in Poland: an ERA5-based analysis. Energies 14, 1118 (2021).

Nefabas, K. L., Söder, L., Mamo, M. & Olauson, J. Modeling of Ethiopian wind power production using ERA5 reanalysis data. Energies 14, 2573 (2021).

Ruiz, S. A. G., Barriga, J. E. C. & Martínez, J. A. Wind power assessment in the Caribbean region of Colombia, using ten-minute wind observations and ERA5 data. Renew. Energy 172, 158–176 (2021).

Jourdier, B. Evaluation of ERA5, MERRA-2, COSMO-REA6, NEWA and AROME to simulate wind power production over France. Adv. Sci. Res. 17, 63–77 (2020).

Dörenkämper, M. et al. 2020: The making of the new european wind atlas–part 2: Production and evaluation. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5079–5102 (2020).

Dupré, A., Drobinski, P., Badosa, J., Briard, C. & Plougonven, R. Air density induced error on wind energy estimation. Ann. Geophys. Disc. https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-2019-88 (2019).

Jourdier B. Ressource éolienne en France métropolitaine: méthodes d'évaluation du potentiel, variabilité et tendances [Wind resources in metropolitan France: methods for assessing potential, variability and trends, in French]. PhD from Ecole Polytechnique, 229pp https://theses.hal.science/tel-01238226 (2015).

Wahl, S. et al. A novel convective-scale regional reanalysis COSMO-REA2: Improving the representation of precipitation. Meteorol. Z. 26, 345–361 (2017).

Ridal, M., Olsson, E., Unden, P., Zimmermann, K. & Ohlsson A. Uncertainties in ensembles of regional re-analyses. Deliverable D2.7 HARMONIE reanalysis report of results and dataset. Report of EU Seventh Framework Programme UERRA project (#607193). https://uerra.eu/publications/deliverable-reports.html (2017).

Bazile, E. et al. Uncertainties in ensembles of regional re-analyses. Deliverable D2.8 MESCAN-SURFEX surface analysis. Report of EU Seventh Framework Programme UERRA project (#607193). https://uerra.eu/publications/deliverable-reports.html (2017).

Badger, J., Frank, H., Hahmann, A. & Hansen, J. C. Wind-climate estimation based on mesoscale and microscale modeling: statistical–dynamical downscaling for wind energy applications. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 53, 1901–1919 (2014).

Global Wind Atlas (GWA) https://globalwindatlas.info/en/about/method (2023).

Carta, J. A., Ramírez, P. & Velázquez, S. A review of wind speed probability distributions used in wind energy analysis: Case studies in the Canary Islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 933–955 (2009).

Celik, A. N. Energy output estimation for small-scale wind power generators using Weibull-representative wind data. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 91, 693–707 (2003).

Tuller, S. E. & Brett, A. C. (1984). The characteristics of wind velocity that favor the fitting of a Weibull distribution in wind speed analysis. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 23, 124–134 (1984).

Drobinski, P., Coulais, C. & Jourdier, B. Surface wind-speed statistics modelling: alternatives to the weibull distribution and performance evaluation. Bound.-Layer. Meteorol. 157, 97–123 (2015).

García-Bustamante, E., González-Rouco, J. F., Jiménez, P. A., Navarro, J. & Montávez, J. P. The influence of the Weibull assumption in monthly wind. Wind Ener. 11, 483–502 (2008).

Chang, T. J. & Tu, Y. L. Evaluation of monthly capacity factor of WECS using chronological and probabilistic wind speed data: a case study of Taiwan. Renew. Energy 32, 1999–2010 (2007).

Jaramillo, O. A. & Borja, M. A. Wind speed analysis in La Ventosa, Mexico: a bimodal probability distribution case. Renew. Energy 29, 1613–1630 (2004).

Jourdier, B. & Drobinski, P. Errors in wind resource and energy yield assessments based on the Weibull distribution. Ann. Geophys. 35, 691–700 (2017).

Akdag, S. A., Bagiorgas, H. S. & Mihalakakou, G. Use of two-component Weibull mixtures in the analysis of wind speed in the Eastern Mediterranean. Appl. Energy 87, 2566–2573 (2010).

Carta, J. A. & Ramírez, P. Analysis of two-component mixture Weibull statistics for estimation of wind speed distributions. Renew. Energy 32, 518–531 (2007).

Michelangeli, P. A., Vrac, M. & Loukos, H. Probabilistic downscaling approaches: application to wind cumulative distribution functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L11708 (2009).

Müller, R., Pfeifroth, U., Träger-Chatterjee, C., Trentmann, J. & Cremer, R. Digging the METEOSAT treasure—3 decades of solar surface radiation. Remote Sens. 7, 8067–8101 (2015).

Schulz, J. et al. Operational climate monitoring from space: the EUMETSAT satellite application facility on climate monitoring (CM-SAF). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1687–1709 (2009).

Sengupta, M. et al. The national solar radiation data base (NSRDB). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 89, 51–60 (2018).

Huld, T., Müller, R. & Gambardella, A. A new solar radiation database for estimating PV performance in Europe and Africa. Sol. Energy 86, 1803–1815 (2012).

European Commission Joint Research Center. Photovoltaic geographical information system (PVGIS). EU Sci Hub - Eur Comm 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/pvgis (2020).

Pfenninger, S. & Staffell, I. Long-term patterns of European PV output using 30 years of validated hourly reanalysis and satellite data. Energy 114, 1251–1265 (2016).

Atencio Espejo, F. E., Grillo, S. & Luini L. Photovoltaic power production estimation based on numerical weather predictions. IEEE Milan PowerTech., Milan, Italy, https://doi.org/10.1109/PTC.2019.8810897 (2019).

Urraca, R. et al. Evaluation of global horizontal irradiance estimates from ERA5 and COSMO-REA6 reanalyses using ground and satellite-based data. Sol. Energy 164, 339–354 (2018a).

Urraca, R. et al. Quantifying the amplified bias of PV system simulations due to uncertainties in solar radiation estimates. Sol. Energy 176, 663–677 (2018b).

Huang, J., Rikus, L. J., Qin, Y. & Katzfey, J. Assessing model performance of daily solar irradiance forecasts over Australia. Sol. Energy 176, 615–626 (2018).

Psiloglou, B. E., Kambezidis, H. D., Kaskaoutis, D. G., Karagiannis, D. & Polo, J. M. Comparison between MRM simulations, CAMS and PVGIS databases with measured solar radiation components at the Methoni station, Greece. Renew. Energy 146, 1372–1391 (2020).

Jiang, H., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Bai, Y. & Bai, Y. Surface diffuse solar radiation determined by reanalysis and satellite over East Asia: evaluation and comparison. Remote Sens. 12, 1387 (2020a).

Jiang, H., Yang, Y., Bai, Y. & Wang, H. Evaluation of the total, direct, and diffuse solar radiations from the ERA5 reanalysis data in China. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 17, 47–51 (2020b).

Babar, B., Graversen, R. & Boström, T. Solar radiation estimation at high latitudes: assessment of the CMSAF databases, ASR and ERA5. Sol. Energy 182, 397–411 (2019).

Salazar, G., Gueymard, C., Galdino, J. B., de Castro Vilela, O. & Fraidenraich, N. Solar irradiance time series derived from high-quality measurements, satellite-based models, and reanalyses at a near-equatorial site in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 117, 109478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109478 (2020).

Ramirez Camargo, L. & Schmidt, J. Simulation of multi-annual time series of solar photovoltaic power: Is the ERA5-land reanalysis the next big step? Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 42, 100829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2020.100829 (2020).

Global Solar Atlas. https://globalsolaratlas.info/support/methodology (2023).

Jacob, D. et al. EURO-CORDEX: new high-resolution climate change projections for European impact research. Reg. Environ. Change 14, 563–578 (2014).

Ruti, P. M. et al. MED-CORDEX Initiative for Mediterranean climate studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 1187–1208 (2016).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J. & Kjellström, E. Potential climate change impact on wind energy resources in northern Europe: analyses using a regional climate model. Clim. Dyn. 25, 815–835 (2005).

Pryor, S. C., Schoof, J. T. & Barthelmie, R. J. Empirical downscaling of wind speed probability distributions. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D19109 (2005b).

Sailor, D. J., Smith, M. & Hart, M. Climate change implications for wind power resources in the Northwest United States. Renew. Energy 33, 2393–2406 (2008).

Pryor, S. C. & Barthelmie, R. J. Climate change impacts on wind energy: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 14, 430–437 (2010).

Hueging, H., Haas, R., Born, K., Jacob, D. & Pinto, J. G. Regional changes in wind energy potential over Europe using regional climate model ensemble projections. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 52, 903–917 (2013).

Reyers, M., Pinto, J. G. & Moemkena, J. Statistical–dynamical downscaling for wind energy potentials: evaluation and applications to decadal hindcasts and climate change projections. Int. J. Climatol. 35, 229–244 (2015).

Pryor, S. C., Schoof, J. T. & Barthelmie, R. J. Winds of change? Projections of near-surface winds under climate change scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L11702 (2006).

Leckebusch, G. C., Weimer, A., Pinto, J. G., Reyers, M. & Speth, P. Extreme wind storms over Europe in present and future climate: a cluster analysis approach. Meteorologische Z. 17, 67–82 (2008).

Makkonen, L., Ruokolainen, L., Räisänen, J. & Tikanmäki, M. Regional climate model estimates for changes in Nordic extreme events. Geophysica 43, 25–48 (2007).

Lavaysse, C., Vrac, M., Drobinski, P., Vischel, T. & Lengaigne, M. Statistical downscaling of the French Mediterranean climate: assessment for present and projection in an anthropogenic scenario. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 651–670 (2012).

Wild, M., Folini, D., Henschel, F., Fischer, N. & Müller, N. Projections of long-term changes in solar radiation based on CMIP5 climate models and their influence on energy yields of photovoltaic systems. Sol. Energ. 116, 12–24 (2015).

Agbor, M. E. et al. Potential impacts of climate change on global solar radiation and PV output using the CMIP6 model in West Africa. Clean. Eng. Technol. 13, 100630 (2023).

Hua, Y. et al. The impact of climate change on solar radiation and photovoltaic energy yields in China. Atmosphere 15, 939 (2024).

Tantet, A. et al. E4Clim 1.0: The energy for climate integrated model: description and application to Italy. Energies 12, 4299 (2019).

Jerez, S. et al. The impact of climate change on photovoltaic power generation in Europe. Nat. Commun. 6, 10014 (2015).

Delort Ylla, J., Tantet, A. & Drobinski, P. Impact of climate change on high-VRE optimal mixes and system costs: The case of France. Adv. Geosci. 65, 159–169 (2025).

Drobinski, P. et al. The structure of the near-neutral atmospheric surface layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 61, 699–714 (2004).

Reyers, M., Moemken, J. & Pinto, J. G. Future changes of wind energy potentials over Europe in a large CMIP5 multi-model ensemble. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 783–796 (2016).

Schallenberg-Rodriguez, J. A methodological review to estimate techno-economical wind energy production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 21, 272–287 (2013).

Spera, D. & Richards, T. Modified power law equations for vertical wind profiles. In Proceedings of the Conference and Workshop on Wind Energy Characteristics and Wind Energy Siting. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Spera/publication/23833371_Modified_power_law_equations_for_vertical_wind_profiles/links/57dc56b808ae5292a379b258/Modified-power-law-equations-for-vertical-wind-profiles.pdf?origin=publication_detail&_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6Il9kaXJlY3QiLCJwYWdlIjoicHVibGljYXRpb25Eb3dubG9hZCIsInByZXZpb3VzUGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIn19&__cf_chl_tk=1dfsHH1lpfgMepVtoV2LBqk1b1pL0X.AW5BTpcD.0Zo-1751636458-1.0.1.1-Cubith.d.qpqCUbrDsq0p.LgiDoxGdhsgrXAyD_gtnI (1979).

Smedman-Högström, A. S. & Högström, U. A practical method for determining wind frequency distributions for the lowest 200 m from routine meteorological data (for wind power studies). J. Appl. Meteorol. 17, 942–954 (1978).

Manwell, J. F., McGowan, J. G. & Rogers, A. L. Wind energy explained. Theory, design and application. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 689 pp. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119994367 (2009).

Bartholy, J. & Radics, K. Wind profile analyses and atmospheric stability over a complex terrain in southwestern part of Hungary. Phys. Chem. Earth 30, 195–200 (2005).

Jacobson, M. Z. & Kaufman, Y. J. Wind reduction by aerosol particles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L24814 (2006).

Mortensen, N. G. & Jørgensen, H. E. Comparison of resource and energy yield assessment procedures. EWEA Wind Resource Assessment Technology Workshop, Bruxelles https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/118434032/Comparison_of_Resource_and_Energy_Yield_paper.pdf (2011).

Mortensen, N. G. & Jørgensen, H. E. Comparative resource and energy yield assessment procedures (CREYAP) Part II. EWEA Wind Resource Assessment Technology Workshop, Dublin. https://core.ac.uk/download/43253844.pdf (2013).

Dupré, A. et al. Sub-hourly forecasting of wind speed and wind energy. Renew. Energy 145, 2373–2379 (2020).

Carrillo, C., Obando Montaño, A. F., Cidrás, J. & Díaz-Dorado, E. Review of power curve modelling for wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 29, 572–581 (2013).

Lydia, M., Suresh Kumar, S., Immanuel Selvakumar, A. & Edwin Prem Kumar, G. A comprehensive review on wind turbine power curve modeling techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 30, 452–460 (2014).

Pelletier, F., Masson, C. & Tahan, A. Wind turbine power curve modelling using artificial neural network. Renew. Energy 89, 207–214 (2016).

Shokrzadeh, S., Jafari Jozani, M. & Bibeau, E. Wind turbine power curve modeling using advanced parametric and nonparametric methods. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 5, 1262–1269 (2014).

Lydia, M., Immanuel Selvakumar, A., Suresh Kumar, S., Edwin, P. rem & Kumar, G. Advanced algorithms for wind turbine power curve modeling. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 4, 827–835 (2013).

Wagenaar, J. W. & Eecen, P. J. Dependence of power performance on atmospheric conditions and possible corrections. Technical Report, ECN-M–11-033, 1-12. https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34631331/c9w8g0/m11033.pdf (2011).

Fischer, A., Montuelle, L., Mougeot, M. & Picard, D. Statistical learning for wind power: a modeling and stability study towards forecasting. Wind Energy 20, 2037–2047 (2017).

IEC. Part 12-1: Wind turbines - Part 12-1: Power performance measurements of electricity producing wind turbines. International Standard IEC 61400-12-1 report, 556 pp. https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/5429 (2005).

Jacobson, M. Z. & Archer, C. L. Saturation wind power potential and its implications for wind energy. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 109, 15,679–15,684 (2012).

Jacobson, M. Z., Delucchi, M. A., Cameron, M. A. & Mathiesen, B. V. Matching demand with supply at low cost among 139 countries within 20 world regions with 100% intermittent wind, water, and sunlight (WWS) for all purposes. Renew. Energy 123, 236–248 (2018).

Duffie, J. & Beckman, W. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes 4th edn. 910 (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Siegel, M. D., Klein, S. A. & Beckman, W. A. A simplified method for estimating the monthly-average performance of photovoltaic systems. Sol. Energy 26, 413–418 (1981).

Tonui, J. K. & Tripanagnostopoulos, Y. Performance improvement of PV/T solar collectors with natural air flow operation. Sol. Energy 82, 1–12 (2008).

Psomopoulos, C. S., Ioannidis, G. C., Kaminaris, S. D., Mardikis, K. D. & Katsikas, N. G. A Comparative evaluation of photovoltaic electricity production assessment software (PVGIS, PVWatts and RETScreen). Environ. Process. 2, 175–189 (2015).

Kandasamy, C. P., Prabu, P. & Niruba, K. Solar potential assessment using PVSYST software. In Int. Conf. on Green Computing, Communication and Conservation of Energy (ICGCE), Chennai, India http://www.rmd.ac.in/ICGCE2013/contact.html (2013).

Chenni, R., Makhlouf, M., Kerbache, T. & Bouzid, A. A detailed modeling method for photovoltaic cells. Energy 32, 1724–1730 (2007).

Dubey, Sarvaiya, J. N. & Seshadri, B. Temperature dependent photovoltaic (PV) efficiency and its effect on PV production in the world - a review. Energy Procedia 33, 311–321 (2013).

Huld, T. & Amillo, A. M. G. Estimating PV module performance over large geographical regions: the role of irradiance, air temperature, wind speed and solar spectrum. Energies 8, 5159–5181 (2015).

Herteleer, B., Huycka, B., Catthoor, F., Driesen, J. & Cappelle, J. Normalised efficiency of photovoltaic systems: Going beyond the performance ratio. Sol. Energy 157, 408–418 (2017).

Sarmah, P. et al. Comprehensive analysis of solar panel performance and correlations with meteorological parameters. ACS Omega 8, 47897–47904 (2023).

Hudișteanu, V. S., Cherecheș, N. C., Țurcanu, F. E., Hudișteanu, I. & Romila, C. Impact of temperature on the efficiency of monocrystalline and polycrystalline photovoltaic panels: a comprehensive experimental analysis for sustainable energy solutions. Sustainability 16, 10566 (2024).

Bamisile, O., Acen, C., Cai, D., Huang, Q. & Staffell, I. The environmental factors affecting solar photovoltaic output. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 208, 115073 (2025).

Mavromatakis, F. et al. Modeling the photovoltaic potential of a site. Renew. Energ. 35, 1387–1390 (2010).

Hosenuzzaman, M. et al. Global prospects, progress, policies, and environmental impact of solar photovoltaic power generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 41, 284–297 (2015).

IEA. Special Report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains. International Energy Agency, Report, 126 Available at https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/08/special-report-on-solar-pv-global-supply-chains_f884fe79/9e8b0121-en.pdf (2022).

Gueymard, C. A. Revised composite extraterrestrial spectrum based on recent solar irradiance observations. Sol. Energy 169, 434–440 (2018).

Erbs, D. G., Klein, S. A. & Duffie, J. A. Estimation of the diffuse radiation fraction for hourly, daily and monthly- average global radiation. Sol. Energy 28, 293–302 (1982).

Orgill, J. F. & Hollands, K. G. T. Correlation equation for hourly diffuse radiation on a horizontal surface. Sol. Energy 19, 357–359 (1977).

Helbig, N., Löwe, H. & Lehning, M. Radiosity approach for the shortwave surface radiation balance in complex terrain. J. Atmos. Sci. 66, 2900–2912 (2009).

Collares-Pereira, M. & Rabl, A. The average distribution of solar radiation—correlations between diffuse and hemispherical and between daily and hourly insolation values. Sol. Energ. 22, 155–164 (1979).

Hottel, H. & Woertz, B. B. Performance of flat plate solar heat collectors. Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 64, 91–104 (1955).

Liu, B. Y. H. & Jordan, R. C. The long-term average performance of flat-plate solar-energy collectors: with design data for the U.S., its outlying possessions and Canada. Sol. Energ. 7, 53–74 (1963).