Abstract

Forests currently store more carbon in their vegetation and soil than all of the carbon in earth’s atmosphere. But how much additional CO₂ can be removed and sequestered by forests in the future, and at what cost? This study examines the potential and costs of forest-based mitigation in 215 countries, utilizing a dynamic economic model, FAO data, and new estimates of feasible area and pace of forest restoration. It finds that at a carbon price of $100/tCO2 in 2050, 8 GtCO₂ could be sequestered through forest mitigation activities. Of that total, 38% would come from afforestation and reforestation, 26% from avoided deforestation, and 37% from changes in forest management. The majority of mitigation is expected to come from tropical regions, although this share decreases with higher levels of incentives. In a scenario in which afforestation and reforestation activities are limited to observed historical rates, mitigation potential is up to 42% lower in 2050 under high carbon payments, particularly impacting mitigation in temperate forests. These findings inform the cost and scale of meeting national forest-based mitigation targets, and provide a robust foundation for guiding policymakers in the development of evidence-informed forest-based mitigation actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forests play a pivotal role in global climate regulation, storing enormous quantities of carbon and acting as significant carbon sinks1,2. Forests also account for approximately 10–15% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions, due to emissions from deforestation and forest degradation3. Preserving and enhancing forest cover is therefore essential for limiting warming to 1.5 °C, as well as maintaining biodiversity, supporting livelihoods, and ensuring ecosystem services.

The potential for forests to contribute to climate change mitigation is substantial: the IPCC projects that activities related to agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) could mitigate between 8 and 14 gigatons of CO₂ equivalent per year from 2020 to 20504. This potential stems primarily from reduced deforestation, improved management, and restoration efforts, emphasizing the critical role of forests in global climate strategies.

In recent years, forests have gained significant recognition in global climate policy frameworks for their essential role in climate mitigation efforts. This includes the Global Stocktake process under the Paris Agreement, in which countries have set targets for cross-sectoral mitigation, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Notably, over 100 nations - collectively home to more than 90% of the world’s forested land – have explicitly included forests in their NDCs5. In 2025, countries began the process of updating their NDCs to include revised 2030 targets as well as new 2035 targets6.

As nations intensify efforts to meet greenhouse gas reduction commitments, rigorous assessment of future forest carbon sequestration pathways and the associated costs of achieving country-specific mitigation targets has become increasingly critical7. Yet, the capacity to conduct robust national-scale assessments remains constrained by the need to simultaneously account for complex international market interactions and highly context-specific information on domestic markets, policy frameworks, and biophysical land characteristics. Economic and integrated assessment models (IAMs), which play a central role in guiding climate mitigation strategies, typically operate at coarse spatial resolution because they must consider multiple sectors at the global scale to estimate the optimal portfolio of mitigation activities across time and space. Consequently, they are not designed to capture the heterogeneity and dynamics of land-use processes at the national level. Moreover, inconsistencies between model structures and national greenhouse gas inventory reporting systems—particularly in how anthropogenic land-based carbon removals are defined, quantified, and reported—further exacerbate these limitations8. Collectively, these challenges reduce the precision and policy relevance of national assessments of forest-based mitigation potential.

The analysis presented in this paper seeks to help bridge this gap by integrating insights from global market assessments of forest mitigation potential with country-based estimates, thereby improving the alignment between global modeling frameworks and national policy contexts. We employ the open-source intertemporal economic optimization model of the global forest sector (Global Timber Model, GTM), which has been widely applied in the literature on forest-based climate change mitigation at both national and global scales4,9,10,11,12. GTM is used to establish a reference trajectory of future CO₂ fluxes from forests and forest products in the absence of price incentives targeting forest-based mitigation activities. This reference trajectory is then compared to scenarios that incorporate carbon pricing.

The scenario design applied in this analysis includes nine carbon price scenarios, with initial payments ranging from $5 to $200 per tCO₂e and increasing over time at a rate of 3% per year. Land managers are modeled as a single welfare-maximizing agent who responds to these carbon price incentives when making decisions about forest and timber management. Specifically, mitigation incentives are represented as rental payments for carbon sequestration and annual subsidies for carbon stored in harvested wood products9,10,11, combined with a demand for timber products which drives the primary forest management decisions. For each scenario, the model estimates the resulting changes in deforestation, forest management practices (e.g., extended harvest rotations), and re/afforestation activities. Abatement from forests is quantified as the annual difference between net CO₂ fluxes from forests in the baseline scenario and those under each price incentive scenario. Consequently, for every time period, multiple abatement pathways are represented, corresponding to different levels of carbon incentives.

There are no limits or constraints on forest-based mitigation activities at the country level outside biophysical limits already included in the model (e.g., trees could not be planted in areas that are not suitable under current climate conditions) as in the previous studies conducted with GTM9,10,11. However, given the uncertainty surrounding future responses to price incentives for forests, we simulated the same carbon prices under two different assumptions on land available for forest conversion at the country level. The first assumption (presented in the main text) limits future new forest area at the country level to the estimates from Bastin et al.13, which report a maximum potential forest restoration of 5,111 million hectares globally. The maximum size of forests at the country level has been defined in order to preserve biodiversity and food security. The second assumption adds additional constraint on future afforestation and reforestation rates using historical data from Ling et al.14, which identified at the global level approximately 3.71 million hectares per year of regenerated forests between 2000 and 2015. This regeneration rate has been incorporated into the GTM as an upper limit for the annual increase in forest area through afforestation and reforestation efforts, and the results are presented in the “Constrained scenario” section.

For each scenario, the model estimates the optimal level of four potential mitigation activities in each region in response to carbon payments: avoided deforestation, forest management activities, increasing harvest rotations, and re/afforestation (including natural forest regeneration and intensively managed timber plantation establishment). Forest-based mitigation activities have been identified for each GTM region by estimating changes in forest cover, forest management, and timber production. Each activity has been mapped to a specific carbon pool to better understand how countries respond to price mechanisms, considering the dynamic context of forest-based decision-making and interactions between countries through the international timber market. Finally, regional results are downscaled at the country level, using information on historical and current forest cover, carbon in forests, and timber production from the FAO FRA country database15 and FAO Stat16 (see Methods).

This simplified downscaling process enables the development of country-specific Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (MACCs), which are essential for redefining national mitigation commitments. These MACCs provide insights into projected CO₂ fluxes from forests and identify abatement opportunities across the forest landscape at various carbon price levels. By analyzing a diverse range of policy incentives, this research aims to improve understanding of how forests can be effectively managed to mitigate climate change. Ultimately, the findings offer a starting point for policymakers and stakeholders to shape future forest-based climate strategies and estimate the optimal mix of mitigation activities in their portfolios.

Results

Global

Results show that global forests will continue to act as a net sink of CO2 in the future, mainly driven by increased sequestration in temperate region managed forests, which offset net emissions from deforestation in the tropics. In 2050, without carbon price, GTM projects about 1.8 GtCO2 net sequestration with uneven distribution across world countries. The introduction of price incentives for forest sequestration drives an increase of net annual sequestration from 0.8 GtCO2 to 13.6 GtCO2 in 2050, depending on the scenario. As expected, higher carbon prices drive greater sequestration, with mitigation more than tripling as the price rises from $5/tCO₂ to $10/tCO₂—an increase from 0.8 GtCO₂ to 3.1 GtCO₂. However, as prices continue to increase, the additional mitigation achieved per extra dollar declines, indicating a steeper global marginal abatement cost curve for forests. For example, doubling the price from $100 to $200 results in only a 27% increase in mitigation. Nevertheless, shape of the curve suggests that the maximum global sequestration potential is not yet reached even at the highest price scenario of $200/tCO₂ (which corresponds to a carbon value of about $432 in 2050). In contrast, for specific regions or forest types, the shape of the marginal abatement curve exhibits clear signs of saturation, indicating that biophysical and land-use constraints are binding at high price levels. This implies that further price increases in these areas yield negligible additional sequestration, reflecting the exhaustion of cost-effective mitigation potential.

The model allows each region or country to respond to carbon price signals through alternative strategies that reflect local biophysical conditions, economic structures, and land-use dynamics. These responses depend on factors such as the existing carbon stock in forests, expected timber production to meet future demand, and the opportunity cost of converting land to forests, among others. In practice, countries can reduce deforestation, expand forest area through afforestation and reforestation on previously forested or new land, or modify forest management and harvesting decisions to enhance carbon storage. These strategies operate through both the extensive margin—increasing forest area—and the intensive margin—increasing carbon density or prolonging carbon retention in existing forests. The relative contribution of each margin varies across regions and price levels, reflecting differences in land availability, opportunity costs, and management potential. Analyzing the response along these two dimensions provides a clearer understanding of the magnitude and composition of forest-based mitigation potential and how it evolves as carbon prices rise.

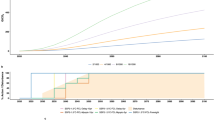

Figure 1A shows that under a carbon price of 100$/tCO2 in 2050 global forest could sequester around 8 GtCO₂, with around 2 GtCO2 of mitigation is from avoided emissions from deforestation or forest conversion, 3 GtCO2 from afforestation and reforestation activities while the remaining 2.9 GtCO2 is delivered by changes in forest management and harvesting decision to increase carbon sequestered per hectare of area. Under higher carbon payments, all mitigation activities increase their potential contribution; however, forest management accounts for a growing share of total sequestration. This shift reflects the fact that afforestation and reforestation opportunities are constrained by country-specific land availability, as highlighted by Bastin et al.13, which estimates ~900 million ha of additional land globally suitable for new tree canopy cover (excluding existing forests, agricultural land, and urban areas). The maximum amount of global mitigation from afforestation and reforestation is estimated around 4.9 GtCO2 in 2050. As a reference, Deprez et al.17 identified the maximum mitigation from afforestation and reforestation to be is 3.8 GtCO2/yr in 2050, to limit negative impacts of forest-based mitigation on biodiversity and food security.

A Shows global marginal abatement cost curves by mitigation pathway, including avoided deforestation, changes in forest management, and afforestation/reforestation. B Presents the same marginal abatement cost curves grouped by dominant forest type: boreal, temperate, subtropical, and tropical forests. In both panels, the y-axis indicates CO2 prices in 2050, and the x-axis shows the mitigation delivered in 2050, measured in gigatonnes of CO₂ (GtCO₂).

Moreover, mitigation from avoided deforestation is inherently dependent on the projected baseline, since only the deforestation expected to occur in the absence of carbon payments can be avoided. This means that the magnitude of potential mitigation is capped by these baseline projections rather than by carbon prices alone. Under current projections, this potential is estimated to be around 2.2 GtCO₂ in 2050, indicating that while avoided deforestation is a critical component of forest-based mitigation, its contribution is ultimately bounded by the underlying land-use trajectory in the baseline scenario.

Once land suitable for new forest establishment is saturated, additional mitigation is increasingly achieved through changes in management intensity and harvesting decisions on existing forest lands. This dynamic illustrates how biophysical land constraints shape the marginal abatement cost curve and influence the relative contribution of mitigation across the extensive and intensive margins. One important response to higher carbon payments is the extension of forest rotation lengths and the reduction of harvesting rates, which indirectly lowers timber production. Globally, total harvest volumes between now and 2050 are projected to decline by 1% to 24% relative to the baseline, as retaining biomass in forests becomes more valuable than harvesting it for trade in global timber markets. However, even at a high carbon price scenario of $200, there is no complete shift away from timber harvesting, since demand for timber remains robust and substitution options are often costly. Over longer time horizons, the marginal impact of carbon prices on timber supply diminishes, indicating a degree of complementarity between carbon sequestration and timber production. In particular, increased tree planting can help offset reduced harvests from existing forests, thereby meeting part of future demand. For example, between 2050 and 2100, the change in harvesting relative to the baseline is projected to range from +1% to –19%.

For each of the 215 countries, the dominant forest type—categorized as tropical, subtropical, temperate, or boreal—was identified following the FAO definition of forest, with dominance defined as covering more than 50% of the total forest area. These classifications were then aggregated to estimate the average mitigation potential by forest type.

Figure 1B shows that across all price levels, tropical forests contribute the largest share of global mitigation, reaching approximately 5.9 GtCO₂ at the highest carbon price tested. Their contribution grows rapidly at low carbon prices, increasing from 0.42 GtCO₂ at $5/tCO₂ to 3.26 GtCO₂ at $20/tCO₂, indicating substantial low-cost abatement opportunities in tropical regions. Temperate forests represent the second largest source of mitigation, increasing steadily from 0.16 GtCO₂ at low carbon prices to 4.77 GtCO₂ at the highest price level.

In contrast, subtropical and boreal forests contribute less overall. Subtropical mitigation reaches 1.69 GtCO₂ at $200/tCO₂, while boreal forests peak at 1.24 GtCO₂. Both exhibit flatter marginal responses to rising carbon prices, consistent with lower biomass density and more limited land availability for expansion.

Overall, these results indicate that tropical and temperate forests dominate the global forest mitigation potential across all price levels, together accounting for more than 80% of total mitigation at high carbon prices. Boreal and subtropical forests play a more modest but still meaningful role, particularly at medium price ranges. The shape of the response curves for each forest type further suggests that tropical forests display high initial responsiveness, whereas temperate forests continue to increase their mitigation contribution more gradually as prices rise.

Country-specific forest-based mitigation opportunities

We develop marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves for forests covering 215 countries, which together account for more than 99% of the expected global forest mitigation potential (presented in the Supporting Information). Countries lacking detailed information on current and historical forest area, aboveground carbon stocks, or timber production were excluded from the analysis, as it was not possible to apply our downscaling methodology in those cases. Among the 215 countries analyzed, we identified 12 representative countries projected to contribute more than 65% of global forest mitigation by 2050 across all carbon payment scenarios. These countries were selected not only for their mitigation significance but also because they capture the diversity of forest types, biophysical conditions, economic systems, and historical land-use dynamics observed globally. This representative subset enables a more detailed exploration of heterogeneous mitigation responses and underlying drivers while maintaining global relevance.

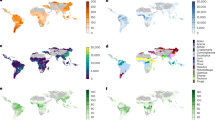

Figure 2 shows country-level results and highlights the highly uneven distribution of forest-based mitigation potential across country and forest types, with a few countries accounting for a large share of total abatement. At low carbon prices, mitigation is concentrated in a handful of countries, while at higher price levels, more countries contribute increasingly significant volumes.

The figure shows country-level forest mitigation potential in 2050, accounting for all forest-based activities under different CO₂ price scenarios. The y-axis indicates the CO₂ price scenario, while the x-axis shows the mitigation potential by country in 2050, measured in million tonnes of CO₂ (MtCO₂). Notes: White bars show the mitigation contributions of the rest of the countries (RO) by forest type. Only Canada and Russia have boreal forests as the dominant forest type.

Across all price levels, tropical forests contribute the largest share of global mitigation, with Brazil being the dominant country. Historically, Brazil has experienced a substantial decline in forest area, from 589 million hectares (Mha) in 1990 to 497 Mha in 202015. Under a future baseline scenario without carbon price incentives, forest area is expected to continue declining at a similar rate. As a result, forest carbon stocks are projected to decrease, and Brazil’s forests are expected to remain a net source of emissions, releasing more carbon through harvesting and land-use change than they sequester annually.

The introduction of a global carbon price on forest carbon storage has the potential to reverse deforestation trends and increase forest area compared with the current trajectory. When the carbon price exceeds $20/tCO₂, net deforestation is projected to reach zero. Notably, even at a relatively low carbon price of $5/tCO₂, Brazilian forests have the potential to become a net carbon sink, as emissions from harvesting and deforestation are offset by increased carbon sequestration through afforestation, reforestation, and improved forest management.

From 1990 to 2020, Indonesia experienced a significant decline in forest area, losing approximately 1.4 million hectares per year15. Despite this loss, the country still accounts for 38% of the forest area and 43% of aboveground carbon in the Southeast Asia region. Future projections indicate that, without price incentives, forest area will continue to decrease but at a lower rate than historical trends. Despite deforestation and harvesting causing around 160 million tons of CO₂ emissions in 2050, carbon removals counterbalance these, resulting in projected net sequestration of 240 million tons of CO₂. Model projections indicate that carbon price of just $5 could reverse this trend, leading to an increase in forest area. Moreover, under a price of $35/tCO2, deforestation of natural forests is projected to stop in the whole region. In 2050, Indonesia’s forests have the potential to mitigate 480 million tons of CO2/yr, assuming a price of $100/tCO2.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a crucial player in the Sub-Saharan region’s environmental landscape, accounting for approximately 37% of aboveground carbon and 22% of total forest area15. However, since 1990, the country has faced a decline in forest area, losing about 0.8 million hectares annually, and resulting in significant net emissions from forests. Encouragingly, if price incentives exceed $20 per ton of CO2 starting now, this downward trend could be reversed, leading to a net increase in forest area. Additionally, in 2050, the mitigation potential of the forests in DRC is estimated to reach 264 million tons CO2 under the highest carbon payment schedule.

Since 1990, Peru has seen a decline in its forest area, from 76 million hectares to 72 million hectares in 2021, with an average of 0.17 million hectares of deforestation per year and 0.024 million hectares of forest expansion per year. Despite this reduction, the country remains an important player in the Latin America region as, excluding Brazil, it accounts for approximately 23% of aboveground carbon and 21% of total forest area15. Without effective price incentives, forests in the country are projected to continue declining in the future. At a carbon price of at least $35 per ton of CO2 this trend could reverse stopping deforestation of natural forests in the region. Looking ahead to 2050, Peru’s forests have the potential to mitigate 251 million tons CO2 under the highest carbon payment schedule.

Mexico plays a vital role in Central America’s environmental health, representing about 47% of aboveground carbon and 70% of the region’s total forest area15. However, the country has experienced a slight decline in forest area since 1990, decreasing from 71 million hectares to 66 million hectares in 2021. If price incentives exceed $20 per ton of CO₂, this downward trend could be reversed, leading to an increase in total forest area and a halt in natural forest deforestation in the future. Results show that in 2050, Mexico’s forests are projected to mitigate 200 million tons of CO2/yr, under high carbon payments.

In 2020, India accounted for approximately 66% of aboveground carbon, 80% of forest area 84% of timber production in the South Asia region15. Since 1990, net forest area has experienced a slight increase from 64 million hectares to 72 million hectares. Model projections in 2050 indicate that forest area will stabilize without price incentives, and it could more than double if carbon prices reach $50 or higher still within the country-specific limit from Bastin et al.13. In 2050, India’s forests have the potential to mitigate up to 596 million tons of CO2.

China and Australia stand out among countries in which subtropical forests are the predominant forest type.

From 1990 to 2020, China experienced an increase in its forest area by 2 million hectares per year which outweighed a deforestation rate of 0.3 Mha in the same period15. Even without price incentives, the net forest area is expected to continue growing, albeit at a reduced rate of 0.25 million hectares annually. However, if a carbon price of $200 is implemented, this growth rate has the potential to continue, allowing for a robust expansion of forested land. This could lead to net carbon sequestration reaching more than 1 GtCO2 under the highest price scenario in 2050.

As of 2021, Australia accounted for approximately 90% of the forest area, 76% of aboveground carbon and 40% of industrial timber production in the Oceania region15, with its forest area remaining stable over the past 30 years. Looking ahead, projections indicate that forest area in Australia could remain stable or increase by 7%, depending on the price incentives implemented within the system. If effectively introduced, these incentives could lead to a maximum of 200 million tons of CO2 additionally sequestered in 2050.

Europe and the United States account for over 50% of global temperate forest area and could contribute up to 80% of the total expected mitigation potential from temperate forests in 2050.

From 1990 to 2020, the U.S. forest area experienced a slight annual increase of 0.25 million hectares mainly driven by demand for timber products. Similar factors will drive future land projections with about additional 0.5 million hectares per year without any price incentives. However, with the introduction of price incentives, this growth could accelerate significantly to 3 million hectares per year by 2050. Such measures have the potential to lead to net carbon sequestration of approximately 1 gigatons of CO2 for a carbon value of $100 in 2050, demonstrating the substantial impact that economic incentives could have on enhancing forest management and conservation efforts in the United States under the $200/tCO2 scenario, the United States is the single largest contributor, with almost 3.0 GtCO₂ mitigation.

Europe has experienced a slight but steady increase in total forest area over the past three decades, rising from 994 million hectares in 1990 to 1,017 million hectares in 202015. This net gain of approximately 23 million hectares reflects the impact of afforestation efforts, natural forest regeneration, sustainable forest management practices. Looking ahead, under future projected baseline scenarios, European forests are expected to continue functioning as a natural carbon sink. However, the introduction of carbon price incentives can significantly enhance this mitigation potential. For small carbon price incentives (below $20/tCO₂), afforestation and reforestation activities are projected to contribute the most to emission reduction, while at higher carbon price levels, changes in forest management and rotation practices are expected to play a more dominant role. With the implementation of such incentives, carbon sequestration from European forests could increase substantially, reaching up to 1.2 GtCO₂ by 2050. While these projections highlight the critical role of forests in climate mitigation, ensuring forest quality and resilience remains essential to sustaining these carbon benefits in the face of climate change, pests, and wildfires.

Russia and Canada are the two countries with boreal forests as their predominant forest type.

In the last 30 years reported in the FAO15, Russia maintained a stable forest area, a trend projected to continue in the future without price incentives. However, introducing such incentives could significantly increase the value of forests, with the area potentially increasing by 4 million hectares per year. In 2050, this expansion is estimated to lead to a maximum net carbon sequestration of 400 million tons of CO2.

Similarly, from 1990 to 2020, Canada maintained a stable forest area15. In the absence of price incentives, forest area is projected to increase by 0.1 million hectares per year. With effective carbon price incentives, this growth is projected to increase to 3.5 million hectares annually. In 2050, under the highest carbon price scenario, net additional forest carbon sequestration is equivalent 820 million tons of CO2 relative to the baseline.

Limiting annual reforestation potential: a constrained scenario

We tested the same price incentive scenarios within a constrained framework, where future reforestation and afforestation rates at the country level are limited to observed historical trends as reported by Ling et al.14. Under this scenario, results indicate a significant decline in global carbon mitigation potential in 2050, with reductions ranging from 20% under the low carbon price scenarios to as much as 42% under the high price incentive scenario, delivering a maximum mitigation of 7.9 GtCO₂. Notably, all forest biomes are projected to achieve less mitigation for the same price under this constraint, with temperate forests experiencing the most substantial decline in percentage terms. This highlights how sensitive the results are to the pace of afforestation and reforestation activities available in the model, and these results could be interpreted as a conservative estimate of mitigation potential if the historical patterns limiting planting do not shift or do not accelerate with carbon price incentives. Fig. S1 illustrates the impact of constraints on afforestation and reforestation rates by comparing the maximum achievable carbon sequestration (MAC) from global forests in both unconstrained and constrained scenarios. It highlights that limited mitigation strategies in the constrained scenario led to less overall mitigation for the same price incentive and that for the same price incentive a much lower global mitigation could be achieved.

Discussion

This study offers critical insights into the role of forests in climate mitigation under varying carbon pricing scenarios, and presents future projections of forest market dynamics, carbon sequestration, and land use that highlight opportunities and constraints associated with forest-based mitigation pathways. By comparing net emissions under a baseline scenario – absent any mitigation policy or carbon price - with those under multiple carbon price trajectories, the analysis generates marginal abatement cost curves (MACCs) for forests at global, regional, and national scales. These MACCs provide a valuable framework for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of forest mitigation actions and can inform both national climate planning and international cooperation results.

Importantly, to explore uncertainty in mitigation potential, the study tests two bounding scenarios. The more optimistic scenario considers only biophysical constraints, using country level estimates of potential forest area from Bastin et al.13. In contrast, the more conservative scenario combines this biophysical limit with an additional constraint on the rate of reforestation and afforestation, based on observed historical trends reported by Ling et al.14. This range provides useful insight in how these factors could influence future attainment of mitigation targets. Moreover, constraints from new studies18,19 could be integrated in the future. The advantage of this approach is that the constraints are directly included into the economic model, ensuring that decisions made at the forest level account for the limits on changes in forest area, rather than applying these restrictions through post-processing. The same inputs can also be replaced to test alternative assumptions, allowing for greater flexibility and robustness in scenario analysis.

Additional constraints—such as socio-economic, institutional, or political factors—could be incorporated into future iterations of the model. For example, by integrating national-level data and detailed stakeholder input, this work could support the development and refinement of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.

Beyond supporting national mitigation planning, the results also have implications for global restoration goals. For example, the Bonn Challenge seeks to restore 350 million hectares of degraded land by 2030. According to the unconstrained scenario, that target could be reached under a global carbon price of $150 per ton of CO₂. However, under the more constrained scenario reflecting the observed pace of historical forest expansion, only 51 million hectares of additional forest area is projected by 2030. This divergence highlights the importance of transparent scenario design and the need to communicate uncertainty in policy-relevant modeling. These results also emphasize the need for further research informing investments in key steps in the forest restoration pipeline including tree seedling production and infrastructure, workforce development, and planting strategy20.

This study is subject to several limitations. It assumes well-defined property rights, which may not hold in many regions where land tenure is unclear or contested. It also assumes perfect information among all actors, overlooking the role of information asymmetry or limited access to relevant data. The analysis does not account for free-riding behavior, where actors benefit from others’ mitigation efforts without contributing themselves. Lastly, the impacts of climate change are not directly modeled, even though they could substantially influence forest growth, productivity, and vulnerability—thereby altering the effectiveness and costs of forest-based mitigation strategies21.

Despite these limitations, the study represents the first comprehensive effort to produce country-level estimates of forest mitigation potential across a range of carbon prices. It provides a valuable foundation for developing targeted and cost-effective forest mitigation strategies. While uncertainties in future socio-economic conditions and sectoral responses remain, the estimates presented offer an important starting point for scenario analysis and strategic planning in the forestry sector. For instance, mitigation from avoided deforestation emissions is strongly influenced by assumptions on baseline deforestation trends, which in turn depend on socio-economic and technological factors affecting future land demand. These insights underscore the need to integrate both biophysical and socio-economic dimensions into policy design to maximize the effectiveness and resilience of forest-based climate mitigation strategies.

Looking forward, several research directions can support the development of a more integrated approach to forest-based activities—one that simultaneously supports timber production, biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, and ecosystem resilience.

First, future work should explore how forest-based strategies can contribute not only to climate mitigation but also to broader sustainability goals, such as the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)’s Land Degradation Neutrality goal and the Global Biodiversity Framework’s target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. Although the current GTM framework enables assessment of carbon and market outcomes, it can be extended to evaluate biodiversity impacts, by differentiating between natural and managed forests. Integrating metrics describing biodiversity and other conservation targets into the model would allow researchers to evaluate the feasibility and cost of achieving multiple environmental goals simultaneously together with synergies and trade-offs. Overlaying model projections with spatial data on ecosystems and biodiversity could also help identify priority areas for conservation and restoration efforts at the national level.

Second, forest resilience to natural disturbances such as wildfires and pest outbreaks is becoming increasingly important in a changing climate. GTM can support resilience assessments by simulating future socio-economic and policy scenarios in the absence of disturbances and then comparing outcomes to scenarios that include disturbance effects derived from external models such as dynamic global vegetation models (DGVMs). Additionally, the model can be used to simulate adaptive management strategies aimed at reducing vulnerability, such as altering species composition, increasing thinning, or implementing prescribed burns. Figure S2 presents a simplified example of how climate change impacts on forests can be integrated into the MACC framework by applying results from Favero et al.22 to evaluate the effect of disturbances on forest mitigation potential in Australia. This case illustrates how mitigation, adaptation, and impact modeling can be brought together in a comprehensive framework for future analyses.

Third, growing interest in forest biomass products as a climate solution—in sectors ranging from energy to construction—requires a better understanding of supply potential and indirect effects. Products such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), and cross-laminated timber (CLT) all rely on sustainable biomass supply chains23,24. Estimating future biomass supply at the country level, and assessing how increased demand affects land use, food production, and forest carbon stocks, is critical. For example, collecting forest residues for bioenergy can help reduce wildfire risk by lowering fuel loads, but it may also reduce forest carbon stocks. These trade-offs vary significantly across regions, depending on local harvesting practices, bioenergy needs, and exposure to climate risks. Spatially explicit assessments are therefore necessary to understand how biomass expansion may alter the results presented in this study and to design strategies that balance mitigation, resilience, and ecological integrity.

In summary, this study lays the groundwork for a more integrated approach to forest-based climate solutions. Expanding the scope of forest-based modeling frameworks like GTM to address the interlinked goals of mitigation, adaptation, biodiversity, and ecosystem services, will be essential for designing policy and investment strategies that align national forest objectives with global climate and sustainability targets.

Methods

The Global Timber Model

The forestry model used in this analysis is the Global Timber Model (GTM), which was initially developed to study dynamic forest markets and policies. GTM combines spatially detailed data on forests with an economic model that weighs optimal forest management alternatives25.

GTM contains 350 world timber supplies i in 16 regions. Forest resources are differentiated by ecological productivity and by management and cost characteristics. To account for differences in ecological productivity, different land classes in different regions have different yield functions for timber, derived from the underlying inventory data. Moreover, forests are broken into different types of management classes. The first type is moderately valued forests, these are forests managed in rotations and located primarily in temperate regions. The second type are natural inaccessible forests, located in regions that are costly to access to be managed for timber production. A third type is low-value forests located in temperate and boreal areas that are lightly managed, if they are managed at all. These low-value lands in temperate and boreal zones are linked to inaccessible types directly, such that when inaccessible forests are harvested in boreal and temperate zones, they are converted to semi-accessible forests. A fourth category includes low-value timberland in inaccessible and semi-accessible regions of the tropical zones. The fifth type includes the high-valued timber plantation that is managed intensively; these forests can principally be found in subtropical regions of the United States, South America, southern Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Indonesia, and Oceania.

GTM is an economic model of forests that maximizes the net present value of consumers’ and producers’ surplus in the forestry sector. By maximizing the net present value, the model optimizes the age of harvesting timber a and the intensity of regenerating and managing forests \({m}_{t}^{i}\). It is an optimal control problem given the aggregate demand function, starting stock, costs, and growth functions of forest stocks. GTM relies on forward-looking behavior and solves all time periods at the same time; this means that when land owners make decisions today about forest management, they do so by considering the implications of their actions today on forests in the future with complete information. The result is a forecast of what a competitive market would also do with forestland.

Mathematically, this optimization problem is written formally as:

In Eq. (1), \({\rho }^{t}\) is a discount factor, \(D\left({Q}_{t}^{{ind}},{Z}_{t,{RCP}}\right)\) is a global demand function for industrial wood products given the quantity of wood \({Q}_{t}^{{ind}}\) and average global consumption per capita \({Z}_{t}\) from the SSP225.

Industrial timber demand follows the general functional form \({Q}_{t}^{{ind}}={A}_{t}{\left({Z}_{t}\right)}^{\theta }{P}_{t}^{\omega }\), where \({A}_{t}\) is a constant, θ is income elasticity, \({P}_{t}\) is the timber price, and ω is price elasticity. The global demand function is for industrial round wood, which is itself an input into products like lumber, paper, plywood, and other manufactured wood products.

We assume there is an international market for timber across the 16 regions that leads to a global market clearing price.

In this version of the model, we do not assume bio-energy demand driven by alternative price incentives in order to isolate the effects of investments only forest mitigation activities without indirect effects from the energy system. Other versions of the model have already assessed the effects of future bio-energy demand combined with forest sequestration policies at the regional and global level (Favero et al.26).

Equation (2) shows that the total quantity of wood depends upon the area of land harvested in the timber types in i for each age a and time t (\({H}_{a,t}^{i})\) and the yield function (\({V}_{a,t}^{i})\) which is itself a function of ecological forest productivity \({\theta }_{t}^{i}\) which changes depending on natural forest productivity and management intensity \({m}_{t0}^{i}\).

\(C\left({Q}_{t}^{{ind}}\right)\) is the cost function for harvesting and transporting logs to the center (mills or power plants) from each of timber type.

The stock of land in each forest type adjusts over time according to:

The initial stocks of land \({X}_{t}^{i}\) are given and all choice variables are constrained to be greater than or equal to zero and the area of timber harvested \({H}_{a,t}^{i}\) does not exceed the total timber area. \({G}_{t}^{i}\) is the area of timber regenerated land planted and \({N}_{t}^{i}\) is the new forest planted. \({C}_{G}^{i}\left(\cdot \right)\), is the cost function for planting land in temperate and previously inaccessible forests while \({C}_{N}^{i}\left(\cdot \right)\) is the cost function for planting forests in subtropical plantation regions.

In the main text, afforestation and reforestation activities were constrained at the country level using inputs from Bastin et al.13. Specifically, Bastin et al. reported country-based forest restoration potential in absolute terms, with a maximum global forest area of 5,111 million hectares. We applied these maximum values to each country i to limit the amount of new forest area available at the national level when downscaling regional estimates of forest expansion (see Eq. 4). In addition, we tested an extra constraint on the 10-year annual average rate of forest expansion by using country-specific estimates of afforestation and reforestation rates from Ling et al.14. This constraint may underestimate potential annual carbon sequestration at the national level, as historical rates may not reflect future expansion potential under strong policy incentives (see Eq. 5). Finally, refer to Fig. S1 for the effects of the two land constraints.

GTM considers the competition of forestland with farmland using a rental supply function for land represented by \({R}_{t}^{i}\left(\cdot \right)\) in Eq. 1. In GTM the demand for land from the forestry sector competes with the demand for land from agriculture and pasture. The land supply functions are region-specific, which considers biophysical and economic characteristics of each region. With a GHG price incentive on forest mitigation the value of forestland increases relative to other uses. This drives the demand for new land to be converted to forests. Land is converted into forests if forestland prices rise relative to farmland prices. The total amount of forestland is therefore endogenous in the model. This rental supply function is restricted to land that is naturally suitable for forests and it assumes that the least productive crop- and pasture- land will be converted first and that rental rates increase as more land is converted and thus becomes scarcer.

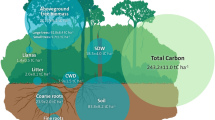

The model is also developed to account for the global forest carbon stocks and flows and introduces incentives to increase its flux and/or stock. Carbon is tracked in four pools, biomass carbon, soil carbon, forest product carbon, and slash.

Biomass carbon \({C}_{a,t}^{i}\) accounts for the carbon in all components of the living tree, including roots, as well as carbon in the forest understory and the forest floor, but does not include dead organic matter in slash, which is contained in a separate pool. For this analysis, we assume that carbon is proportional to total biomass, such that carbon in any forest of any age class is given as:

where \({\sigma }^{i}\) is a species dependent coefficient that converts biomass to carbon and the volume is not only affected by management decisions \({m}_{t0}^{i}\) but also by the assumed change in natural forest productivity \({\theta }_{t}^{i}\).

Given this, the total forest carbon pool \({{TFCP}}_{t}^{i}\) for each timber type is calculated as:

Carbon in harvested forest products \({{HC}}_{t}^{i}\) is estimated by tracking forest products over time as follows:

where \({\kappa }^{i}\) is the proportion of harvested timber volume that is carbon stored permanently and it is estimated to be 0.30.

Soil carbon\(\,{{SOLC}}_{t}^{i}\) is measured as the stock of carbon in forest soils of type i in time t. The value of \(\bar{K}\), the steady state level of carbon in forest soils, it is unique to each region and timber type. The parameter \({\mu }^{i}\) is the growth rate for soil carbon. In this analysis, we capture the marginal change in carbon value associated with management or land use changes. When land use change occurs, we track net carbon gains or losses over time as follows:

Finally, we measure slash carbon \({{AS}}_{t}^{i}\) as the carbon left over on site after a timber harvest.

Over time, the stock of slash \(S{P}_{t}^{i}\) builds up through annual additions, and decomposes as follow:

Decomposition rates \({\vartheta }^{i}\) differ, depending on whether the forest lies in the tropics, temperate, or boreal zone.

In Eq. (1), the term \({{CarbInv}}_{t,{level}}\) represents the carbon price incentives for forests. Under the baseline scenario without investments in forest mitigation, \({{CarbInv}}_{t,{scenario}}=0.\) Mitigation incentives are represented in the model in the form of rental payments \({R}_{t}^{c}\) for carbon sequestration and annual incentives \({P}_{t}^{c}\) for carbon in timber products as follows:

The first part of Eq. 11 is the carbon transferred to long-lived wood products (\({{HC}}_{t}^{i}\)) from each forest i valued at the carbon price \({P}_{t}^{c}\). The change in soil carbon (\({{SOLC}}_{t}^{i}\)) when land switches between forests and agriculture is also valued at the carbon price. The second term is the annual rent, \({R}_{t,}^{c}\), whereby the total carbon stocks in forests \({{TFCP}}_{t}^{i}\) are rented during the time period that the carbon is stored following previous studies9,10,11,26,27. The rental value for carbon is:

where r is the interest rate.

In order to test different levels of investments in forest mitigation, we simulate 9 price incentive scenarios in which \({P}_{t}^{c}\) starts at $5, $10, $20, $35, $50, $75, $100, $150, and $200 and growing at 3% per year.

Abatement from forests is measured as the annual difference between net CO2 flux from forests in the baseline relative to the price incentive scenario. Therefore, for every time period, multiple abatement pathways are modelled, reflecting a range in carbon incentives. GTM models 16 world regions and estimates the abatement for each of them and finally aggregates it at the global level.

Finally, the model is calibrated to regional forest inventory to the extent possible, and recent analysis indicates that future market and land use projections are robust to parametric uncertainty related to forest growth and land supply parameters28. Another GTM paper provides a historical calibration exercise with the model performing a simulation of a historical time to illustrate the important contributions of management to the evolution of terrestrial carbon stocks historically29.

Activities

GTM responds to different carbon payments by adjusting forest management activities and/or converting land to and from forest use. Country-level responses are influenced not only by the trade-offs between timber production—to meet global demand—and carbon mitigation in response to price incentives, but also by decisions made in other countries, as all interact through the global timber market.

We calculate carbon mitigation from forests as the change in carbon flux across four carbon pools— biomass, soil, harvested wood products (market), and slash—relative to the baseline. Within these pools, we identify four primary activities in response to the implemented scenarios and infer their mitigation potential by comparing changes in forest area and forest management practices between the carbon scenario and the baseline.

First, since carbon rentals are applied to the carbon stock stored in existing forests, a key model response is the projected reduction in deforestation under the baseline scenario. Preventing forest loss helps preserve existing aboveground carbon stocks. We estimate mitigation from reduced deforestation as the product of the average carbon density (tC/ha) of different forest types in each region and the area of forest loss avoided. This reflects the emissions that would have occurred under the baseline but were prevented. Moreover, because forests where deforestation has been avoided continue to grow—albeit at a declining rate as forests age —we also account for the additional carbon sequestration that occurs over time.

Second, establishing new forests on previously non-forested land or cleared forest land (i.e., through afforestation or reforestation) increases aboveground carbon stocks over time. We quantify mitigation from these activities as the product of the average aboveground carbon density (tC/ha) and the area of new forest established, relative to the baseline scenario. As these forests age, their carbon density increases, contributing to additional sequestration. Furthermore, converting non-forest land to forest also enhances soil carbon stocks, providing an additional source of mitigation.

Third, changes in forest management—such as adjustments to harvest intensity or rotation length—can influence the accumulation of aboveground biomass. We estimate the mitigation impact of these management interventions as the difference between GTM’s total projected aboveground carbon and the combined contributions from avoided deforestation and afforestation/reforestation (described above). This residual represents the portion of aboveground carbon change specifically attributable to forest management practices. This category also includes increases in carbon sequestration per hectare driven by natural processes such as carbon fertilization, since for extensive mitigation we used historical forest yield data that were not affected by fertilization.

Fourth, since carbon payments also apply to carbon stored in harvested wood products, the model can respond to a carbon price signal by modifying harvesting practices, increasing the longevity of wood products, or reallocating production toward more durable product categories relative to the baseline scenario.

It is important to note that, because the policy is implemented at the global level, changes in land use or forest management in one country can indirectly influence outcomes in others. As a result, carbon stored in one or more of the pools may decline in certain regions—not only due to local mitigation constraints but also as a consequence of leakage or market-driven responses to policy impacts elsewhere. This underscores the importance of evaluating net global impacts across all carbon pools and participating countries.

Downscaling

To better capture the spatial and sectoral heterogeneity of mitigation outcomes, we adopted a two-step approach. First, within each GTM region, we identified the forest-based activities driving carbon mitigation by estimating the effects of carbon payments on forest area, type, and composition—distinguishing between natural (unmanaged) and managed forests. This allowed us to quantify emissions from deforestation and forest conversion, as well as carbon removals associated with afforestation and reforestation.

Second, these region-level results were downscaled to the country level to better reflect spatial heterogeneity. To further refine our assessment of mitigation potential, we decomposed outcomes into two components: forest carbon–driven (e.g., avoided deforestation, afforestation) and market-driven (e.g., shifts in harvesting practices), recognizing that factors beyond forest carbon stocks—such as timber market dynamics—can significantly shape mitigation responses. This approach captures, for example, how a country within a GTM region that holds a relatively small share of the region’s aboveground carbon but a large share of its timber production may respond differently to carbon payments than a country with high forest carbon density and limited harvesting activity. We used information on historical and current forest cover, carbon in forests and timber production from the FAO FRA country database15 and FAO Stat16.

For instance, within the GTM region Central America, Mexico accounts for 69% of the region’s forest area, 47% of its aboveground carbon, and 68% of its timber production. Relying on only one of these metrics to allocate regional results could lead to either an over- or underestimation of the country’s actual mitigation potential relative to the region it represents in the model. To address this, we apply a combination of indicators: the country’s shares of forest area and aboveground carbon, along with the maximum forest area available from Bastin et al.13, to estimate mitigation from increase in carbon in biomass and soil. In addition, the country’s share of timber production within the region is used to estimate avoided emissions from harvesting and the carbon stored in harvested wood products.

Data availability

The model output data generated by GTM that was used to visualize the results have been deposited on the Research Gate repository.

Code availability

GTM code used for this paper is available on the Global Timber Model Code Repository at the following link: https://u.osu.edu/forest/coderepository/.The code for this paper is included in the folder ‘Austinetal2025’.

References

Ellison, D., Pokorný, J. & Wild, M. Even cooler insights: On the power of forests to (water the Earth and) cool the planet. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17195 (2024).

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631, 563–569 (2024).

Shukla, P. R. et al. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. (IPCC, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157988.002.

Nabuurs, G.-J. et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC (eds. Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.009.

Fyson, C. L. & Jeffery, M. L. Ambiguity in the land use component of mitigation contributions toward the Paris Agreement goals. Earth’s Future 7, 873–891 (2019).

Srouji, J. et al. Next-Generation Climate Targets: A 5-Point Plan for NDCs. (World Resources Institute, 2024). https://www.wri.org/insights/next-ndcs-5-point-plan.

Caldwell, M., Alayza, N. & Larsen, G. Paying for the Paris Agreement. (World Resources Institute, 2022). https://doi.org/10.46830/wrirpt.21.00150.

Gidden, M. J. et al. Aligning climate scenariosto emissions inventories shifts global benchmarks. Nature 624, 102–108 (2023).

Austin, K. G. et al. The economic costs of planting, preserving, and managing the world’s forests to mitigate climate change. Nat. Commun. 11, 5946 (2020).

Austin, K. G. et al. Targeting climate finance for global forests. Nat. Commun. 16, 6443. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61657-6 (2025).

Favero, A. et al. Investing in US forests to mitigate climate change. Carbon Balance Manag 20, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-025-00292-6 (2025).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potential in the U.S. Forestry and Agriculture Sector. (EPA, Washington, DC, 2024).

Bastin, J. F. et al. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Ling, P. Y. et al. Mapping global forest regeneration – an untapped potential to mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 054025 (2023).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Global Forest Resources Assessment FRA Platform. (FAO, 2021).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT. (FAO, Rome, 2025). https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

Deprez, A. et al. Sustainability limits needed for CO₂ removal. Science 383, 484–486 (2024).

Fesenmyer, K. A. et al. Addressing critiques refines global estimates of reforestation potential for climate change mitigation. Nat. Commun. 16, 4572 (2025).

Mo, L. et al. Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential. Nature 624, 92–101 (2023).

Fargione, J. et al. Challenges to the reforestation pipeline in the United States. Front. For. Glob. Change 4, 629198 (2021).

Golub, A., Sohngen, B., Cai, Y., Kim, J. & Hertel, T. Costs of forest carbon sequestration in the presence of climate change impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 104011 (2022).

Favero, A., Mendelsohn, R., Sohngen, B. & Stocker, B. Assessing the long-term interactions of climate change and timber markets on forest land and carbon storage. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 014051, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd589 (2021).

Favero, A., Baker, J., Sohngen, B. & Daigneault, A. Economic factors influence net carbon emissions of forest bioenergy expansion. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 41, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00698-5 (2023).

Lan, K., Favero, A., Yao, Y., Mendelsohn, R. O. & Wang, H. S. H. Global land and carbon consequences of mass timber products. Nat. Commun. 16, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60245-y (2025).

Daigneault, A. & Favero, A. Global forest management, carbon sequestration, and bioenergy supply under alternative shared socioeconomic pathways. Land Use Policy 103, 105302 (2021).

Favero, A., Daigneault, A. & Sohngen, B. Forests: Carbon sequestration, biomass energy, or both?. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6792 (2020).

Favero, A., Mendelsohn, R. & Sohngen, B. Using forests for climate mitigation: Sequester carbon or produce woody biomass?. Clim. Change 144, 195–206 (2017).

Sohngen, B., Salem, M. E., Baker, J. S., Shell, M. J. & Kim, S. J. The influence of parametric uncertainty on projections of forest land use, carbon, and markets. J. For. Econ. 34, 129–158, https://doi.org/10.1561/112.00000445 (2019).

Mendelsohn, R. & Sohngen, B. The net carbon emissions from historic land use and land use change. J. For. Econ. 34, 263–283, https://doi.org/10.1561/112.00000505 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: K.A., A.F.; Methodology: K.A., A.F.; Investigation: K.A., A.F.; Visualization: K.A., A.F.; Writing: K.A., A.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Favero, A., Austin, K. Charting our forest future: national supply curves for forest-based CO₂ mitigation. npj Clim. Action 5, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-026-00335-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-026-00335-9