Abstract

This paper explores the mechanical intelligence of a mountain goat-type hoof designed for passive dynamic slip resistance on inclined natural surfaces. We hypothesised that specific hoof features can be tuned to leverage sloped terrain characteristics to reduce slip. We took a situated heuristics-based approach to iteratively design the hoof, conducting multiple experiments in an Alpine-type environment. Results show that combining surface geometry, material, and direction-dependent compliance in various degrees of freedom is key to reducing slip. Indoor tests across slope angles and loads show that stick-slip events correlate with reduced slip distance following a forced slip from rest. Additionally, tests on different slope surfaces showed that the passive slip dynamics also depend on the mechanical properties of the slope itself. Overall, these results affirm that a situated heuristics-based design approach effectively builds mechanical intelligence in a robot, enabling it to optimise interactions with its environment for improved slip resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advancements in actuation and control strategies have resulted in increasingly agile and robust quadruped robots. Legged robots are particularly desirable for their natural ability to navigate challenging terrain, such as rocky ground or debris, where robots equipped with tracks or wheels may struggle or fail. However, the concentrated pressure on the feet during walking can increase the risk of slipping on slopes. Most commercially available robots use round, rubber feet, which offer simplicity and consistent traction regardless of the leg’s angle relative to the surface. Notable quadrupeds using rounded rubber feet include Spot by Boston Dynamics1, ANYmal by ANYbotics2 and the quadruped range by Unitree3. These rubber feet are also more robust than mechanically complex designs, with fewer components to fail. Rather than being heavily optimised for specific terrain types, they perform reliably across a wide range of environments.

However, these rounded, rubber feet are still prone to slipping, especially on rocky or complex surfaces, limiting the application of these robots in environments with uneven terrain, such as mountain environments or urban rubble. Surface contaminants such as water, mud, plant matter, and grit can further worsen their performance in outdoor walking. On slopes, the normal force on the surface substantially reduces while the tangential component of the weight increases, making a robot more prone to slippage. Unstable surfaces may also collapse underfoot, causing additional slippage.

Land animals provide an interesting bio-inspiration for slip reduction on slopes. They have evolved to navigate challenging terrain, with their feet serving as the crucial point of contact that enables movement. Even similar groups of animals, like ungulates, have vastly varying foot morphology that helps them move effectively and efficiently in their environment.

The morphological features of natural feet are closely adapted to the environment in which they evolved. This tunes passive dynamic interactions with the environment to maximise the efficiency and reliability of achieving survival goals. An example is how the morphological features, such as the contact geometry and structural stiffness, can give rise to passive slip-reduction dynamics that emerge from the interaction with the environment. This, in turn, reduces the need for frequent closed-loop control involving the Central Nervous System (CNS). This shared problem-solving between the passive dynamics and the CNS is an example of what is known as ‘embodied intelligence’4.

Lauder et al. first showed that a dead trout body can passively synchronise with a turbulent stream of water to swim upstream5. Later, they showed, using a soft robotic phantom fish that passive thrust against the stream peaks for a certain stiffness of the body6. These results show the importance of the morphological features of the physical body to poise itself to exhibit meaningful and predictable behaviour during interactions with the natural environment. The results in passive dynamic walking7 also support this phenomenon, where a passive dynamic walker can use just the gravitational force along the slope of a ramp to reach steady state walking without any sensing or closed-loop control. The ideas proposed in Templates and Anchors8 show that meaningful behaviour in natural environments can emerge with an interplay between neural and mechanical systems to pose the body towards stable and efficient locomotion.

In this paper, we are focusing on improving the quadruped foot design for improved stability on slopes. Existing research has focused on enhancing traction by examining hooves; the most commonly studied hooves belong to the goats and their close relatives (the Caprinea). Many of these animals, perhaps most notably the North American mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus)9 and European alpine ibex (Capra ibex)10 live in alpine environments, which are rugged, mountainous areas where steep, rocky terrain and various surfaces are common. These environments often consist of cliffs, rocky outcrops, and sparse vegetation, which require sure-footedness and agility to navigate safely11. The hooves of these animals are highly specialised to help them survive in such challenging conditions.

Zhang et al.12 generated a model from a 3D scan of a domestic goat hoof, subsequently demonstrating via simulation that the morphology of the hoof generally improved slip resistance on flat surfaces compared to a pure round or cylindrical foot. However, this result did not account for differences in surface area between the hoof and control, limiting the applicability of its findings. In a similar study, Li et al.13 created a bionic hoof that took inspiration from the micro-structures and wider morphology of a reindeer hoof, also a two-toed ungulate. This study performed physical tests in the context of frozen soil and hard ground, finding experimentally that the specific shape of the two-toed hoof improved traction compared to a control of a similar surface area. Inspiration from the micro-structures of hooves was also utilised by Cong et al.14. They designed an abstracted robotic end-effector with the goal of improving vibration reduction during ground impacts. This research found benefits in reducing impact vibration, but it did not test its relevance to frictional vibration, which is more useful for investigating slip resistance. Abad et al.15,16 provided a simplified model of the goat foot anatomy consisting of three joints: fetlock, pastern, and coffin, which provide roll, yaw, and pitch rotations, respectively. They showed that mimicking the toe shape and joint structure improved traction when compared to a round foot. They additionally found that specific tuning of joint stiffness could allow for further improvement16.

Crucially, existing studies have largely evaluated the performance of bio-inspired designs on planar surfaces, with several only tested in simulations. Li et al.13 introduced slightly loose terrain, but real-world robotic locomotion in mountainous environments requires navigating highly complex, varied, and sometimes steep surfaces, such as mud, rocky ground, or scree. Additionally, wet weather can greatly affect terrain stability and coefficients of friction between the feet and ground surfaces, dramatically reducing grip.

Building on this gap, Ranjan et al.17 advanced the field by developing a bio-mimetic robotic hoof designed to handle uneven terrain. Expanding on Abad’s work, they provided stiffness bounds for joint rotation in roll and yaw directions, calculated through an analytical model of the hoof. This approach allows passive adaptation to uneven surfaces, balancing adaptability and stability and outperforming hemispherical control feet in stability across varied terrains.

Despite the advantages of recent research, designs such as those of Abad et al.15,16 and Ranjan et al.17 are also relatively complex (high in number of components), which increases the number of potential failure points in a long, autonomous, and dirty locomotion task. Moreover, Ranjan’s design adapts well to specific uneven terrain but may struggle in other natural environments encountered by quadrupeds, such as mud or scree, and as such does not provide a general solution. Furthermore, many morphological features of the mountain goat hoof, which are considered necessary from observations made by Chadwick11, have yet to be explored. These include using the hard edge of the toe to grasp small rock features, the sharp point of the toe to dig into soft surfaces, and the gap between the toes, trapping objects.

Designing a resilient foot with the tuned morphology, structure and materials to interact with a wide range of surface features for traction would typically require accurate modelling and simulation of foot-terrain interaction. However, the current state of foot modelling is significantly limited18. Most existing models are confined to two-dimensional sagittal-plane dynamics, assume flat and rigid ground surfaces, enforce no-slip contact, and utilise overly simplified friction laws. Additionally, these models often rely on rigid or lumped foot geometries, which do not account for compliance, foot adaptability, or interactions with soft or irregular terrain. While these frameworks have primarily been developed for human gait modelling, even this relatively well-studied area lacks generalizable methods for simulating compliant 3D foot interactions. The challenges are even greater for non-human or bio-inspired morphologies.

In contrast, the field of terramechanics offers a more developed modelling ecosystem, albeit limited to wheel-soil interaction. Empirical models, such as those proposed by Bekker19,20, provide quick approximations and have been successfully used to predict traction in homogeneous, well-characterised soils. However, these models lose accuracy in complex or uncharacterised terrains. High-fidelity simulations, such as Discrete Element Method (DEM)21, can capture terrain deformation and transient dynamics but are computationally expensive and require many tuned input parameters that can be very time-intensive and sometimes impractical to acquire for new terrains.

In summary, there is currently no modelling framework capable of accurately predicting the performance of a compliant, 3D bio-inspired foot interacting with unstructured, complex, deformable natural terrain. We believe this lack of modelling tools has halted the development of an advanced but functional robotic foot.

This paper presents an innovative foot design developed using a situated heuristic approach that encodes mechanical intelligence into the hoof without requiring modelling or simulations. This led to a novel foot design that exhibits an interplay among morphology, structure, material and surface features to improve traction across various terrains, outperforming current state-of-the-art designs. Unlike previous research, this design incorporates multiple features without compromising on simplicity, marking a significant advancement toward developing an effective, terrain-adaptive foot for quadruped robots used in alpine exploration.

Results

Description of key terms

Let us first explain some terms we use in the rest of the paper.

Morphological features

These include the geometric features, degrees of freedom (DOFs), structural parameters, and mechanical impedance distribution of a mechanism. For instance, in the case of a hoof, the morphology of a camel hoof will be different from a mountain goat hoof in terms of the geometric features, such as: the contact surface shape; the number of joints; the skeletal structure; the compliance at different joints; and the softness of key parts such as pads at the contact surface. In this study, we used the mountain goat hoof primarily as a biological reference to form initial hypotheses about the morphological features most relevant to slip reduction. Two aspects were identified as particularly important: (i) pronounced edging to enhance grip through terrain engagement, and (ii) structural compliance that enables passive flapping, which facilitates adaptive surface contact and energy dissipation22.

Mechanical intelligence

The ability of a mechanism or a network of physically connected mechanisms to render a passive dynamic response leading to an intended outcome given a class of external forces. For instance, we say that the hoof has mechanical intelligence if its morphological features are in a certain range to emerge transient passive dynamics leading to slip reduction on a range of slope types.

Situated heuristics-based design

This design approach involves first making certain observations about the mechanical properties of objects in the environment that a robot would physically interact with and interpreting them relative to a set of survival goals. Then a set of initial key morphological features are designed based on heuristics. This step, of course, can be supported by multibody simulations. Then, a preliminary hardware prototype is tested in the target environment with as diverse scenarios as possible while collecting measurements to quantify how well the survival goal is met compared to a baseline control. The measurements are carefully analysed and new designs are made to test variations of the identified strong morphological traits. These new designs then go into the next round of testing within the target environment, and the process of eliminating or freezing negative or neutral traits and developing positive traits repeats. For instance, in the goat hoof, different variations of digit tips and side edge shapes can be tested to derive deeper insights about the phenomenon of edging. This process of design evolution is repeated several times till a robust solution is obtained.

Key factors for mechanical intelligence in a hoof to survive on Alpine-type slopes

The inspiration for this study stems from the remarkable ability of mountain goats to traverse extremely rugged and steep terrains. A visual illustration of this capability is provided in Fig. 1. In A Beast the Color of Winter: The Mountain Goat Observed, Douglas H. Chadwick11 details how the mountain goat hoof is uniquely adapted for stability and grip in rugged alpine terrain. Each hoof consists of two keratin-wrapped toes capable of catching small rock features, with tapered tips that dig into softer surfaces like dirt, aiding traction on uphill slopes. A soft, slightly protruding pad on the underside provides additional friction on smooth surfaces, while the toes’ ability to spread apart enhances grip by creating a braking effect and offering redundancy if one toe slips. Loose or solid surface materials can also lodge between the toes, further increasing braking capacity. Alternatively, the toes can close in a pincer-like grip around ridges for enhanced hold on rock features.

a The goat ascends a steep slope by engaging various features of its hooves: the tip of the front left hoof and the side edge of the front right hoof. It stabilises its body by standing on the hind limbs and using the base of the feet for traction. b Engagement of the hoof base during stance. c Close view of the hoof structure. Photos are provided by Darryn Epp, written permission is given to use and adapt them.

In Fig. 1a, the mountain goat is seen ascending a steep rocky slope, with the tip of the front left hoof and the side edge of the front right hoof engaged with elevated terrain features. Meanwhile, the hind limbs are used for support, with the base of the hooves providing the necessary traction. Figure 1b highlights the engagement of the hoof base during stance, and Fig. 1c offers a more detailed view of the hoof structure. The functional use of various hoof features, as observed in such terrain interactions, is discussed in detail later in this section.

We observe that tuning the morphological parameters of one part of a larger network of mechanical systems can influence the dynamic behaviour of the entire network. Therefore, mechanical intelligence can be evolved in a network by taking a situated heuristics-based design innovation approach.

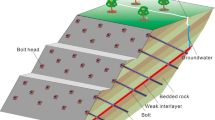

In the case of a mountain goat-type hoof interacting with a natural slope, the hoof can be treated as one mechanical system with a set of tunable morphological parameters. The soil/rock conditions in the slope form another mechanical system we cannot tune. Given external forces such as the weight of a robot on the hoof, the two mechanical systems form a physically connected network. If a slip initiates between the two, the nature of their interaction forces can be influenced by tuning the morphological parameters of the hoof.

The transient dynamics can depend on the slope type such as grass, mud, or rock as well as surface conditions such as dry, wet, roughness, and the slope angle. It can also depend on the morphological parameters of the hoof. The morphological features on the hoof side are not limited to geometries, but include support from structural compliance as shown in Fig. 2c, where the compliance allows the two tips to passively find the best rock feature to sit on depending on the surface geometry.

Therefore, we can say that the morphological parameters of the hoof are best evolved if it can reduce slippage in a range of natural slope types. Figure 2 illustrates the possible interactions between our hoof design and an alpine environment, based on observed interactions of hoofs by Chadwick11. These possibilities show that multiple morphological features in the hoof should take a dominant role in any given interaction scenario. For instance, when the tip or the side edge is bearing the weight of the robot on a slope, a phenomenon called edging plays a dominant role in keeping the hoof from slipping. Edging is used by rock climbers in which the sharp edge of the shoe is employed to secure footholds on small ledges or narrow features.

The toe pitch compliance allows the soft pads, which provide friction on flatter surfaces, to conform to uneven surfaces as shown in Fig. 2d, k and maintain traction when the leg-surface angle is low (Fig. 2e, f). Furthermore, the total compliance of the hoof allows the toes to splay (Fig. 2g), causing a braking effect.

When interacting with surfaces that may cause slipping due to its inherent instability, we hypothesise that the hoof can make a stabilising mechanical connection. Figure 2h, j shows how the toes can trap mud or grass between them, causing a braking effect. The pointed toes can dig into soft surfaces (Fig. 2i), also causing braking. The large level of compliance can allow the hoof to make two points of contact on terrain such as loose pebbles, making a more stable footing (Fig. 2k). The hoof can also combine features to react to complex surfaces. By combining compliance and a hard edge, the hoof can pinch features as seen in Fig. 2i, o. The pointed toe can become wedged in narrow features such as a crack (Fig. 2m), and when on a flat surface, it can also edge on protrusions (Fig. 2m), combining pad friction and edging.

These phenomena show that the hoof should develop certain morphological features that mirror the features of slopes it frequently interacts with.

Situated heuristics-based design innovation

Extensive rounds of comparative testing helped us identify positive, negative, and neutral traits, leading to a design with complex, emergent interactions (Fig. 2). At key stages of this evolution, we conducted comparative tests in the uplands of the Peak District National Park, UK, ensuring that the dynamic coupling between hoof and terrain was grounded in a real environment rather than an approximation. Figure 12 represents the key stages of this situated heuristic-based design innovation process. Thirty-two hoof variations are identified, demonstrating how we evolved two simple hoof designs into a mechanically intelligent design.

Our design abstracted the key morphological features of the hoof identified in biological studies11 and the state-of-the-art research outlined in the ‘Introduction’ section. The primary findings from the literature emphasise the importance of compliance, toe separation, toe shape and material selection. We applied these features to a single-part polyurethane hoof. This hoof aims to bring the advantages of a goat hoof to alpine quadrupeds without compromising on reliability and performance in dirty environments due to mechanical complexity.

The design consists of two independent toes with tuned compliance within the roll and pitch and resultant compliance in the yaw, as seen in Fig. 3a. The toes are pointed with a sharp edge. The compliance in pitch is limited in the clockwise direction of Fig. 3a. The body of the hoof is made from Shore A 80-hardness PU (polyurethane) rubber (Fig. 3bii, while the convex pads are made from softer Shore A 60-hardness PU (Fig. 3biii) and a rigid insert provides a mechanical connection point to the leg (Fig. 3bi).

a The engineered hoof has different degrees of compliance in roll, pitch, and yaw. It is made from three parts: (bi) a solid insert to provide a mechanical interface, (bii) a cast PU Shore-A 80 body, and (biii) PU Shore-A 60 pads. (c) We compared the hoof to a SotA (State-of-the-Art) foot in outdoor experiments. The images of the hoof and SotA foot are at the same scale. The SotA foot was based on the foot used on the ANYmal Quadruped43 to maximise traction.

By virtue of being a single-piece hoof without mating parts, contaminants such as water, grit, and mud have very little effect on the hoof’s mechanical function. Temperature has been seen to affect the hoof’s compliance properties, becoming stiffer during cold weather; however, this could be accounted for by creating a range of designs for different temperature environment bands.

Experimental results within an alpine environment

The hoof was compared to a state-of-the-art (SotA) foot based on a design commonly used in quadruped robots (see Fig. 3c), in order to evaluate whether a mechanical intelligence approach offers improvements over existing solutions. Due to the limited controllability during outdoor testing, a comparative methodology was adopted. Instead of benchmarking against other bio-inspired designs, we selected the SotA foot because it currently offers the highest performance across diverse natural terrains and is widely adopted in quadruped platforms for this reason. The SotA foot excels on natural terrain, thanks to its air bladder and soft polyurethane (PU), which enhance surface contact. Its tread design improves grip and water drainage. The foot’s ball is angled at 15° relative to the leg axis, allowing effective performance on varied slopes.

The maximum load that the two test feet could bear before slipping was measured across various natural surfaces and gradients. It was hypothesised that features depicted in Fig. 2 would be activated during these tests to enhance traction, whereas the SotA foot would rely solely on classical friction and would struggle on steep gradients.

To undertake these experiments in the Peak District National Park, UK, we developed a portable test rig described in Fig. 4. The rig imparts an axial force through the leg F, of which Fcos(θ) is parallel to the surface, trying to initiate a slip. This simulates the quadruped standing statically on the surface, where level ground is when θ = 90°. The force F can be increased by adding weights to m, until a slip is initiated. The force F can be described as:

here, F0 is the baseline force when m = 0.

It is important to note that m is limited to 5 kg; therefore, in many experiments, a slip was not initiated. This is made clear in the results.

Figure 5 presents a selection of five out of the 12 tested surfaces to help the reader visualise the experimental setup, alongside corresponding graphs that show the maximum force each foot withstood before slipping. In downhill scenarios, both the SotA foot and the hoof perform similarly, as classical friction is the dominant mechanism (see Fig. 6). However, on steeper uphill inclines, the SotA foot’s performance deteriorates due to its reliance on classical friction, whereas the hoof retains traction through edging.

Maximum recorded stable force F plotted against θ. Mean (μ) and S.D. (σ) of F are annotated. a steep downhill test on wet rock (see Supplementary Fig. 3b), b downhill test on wet rock (see Supplementary Fig. 3d), c flat test on wet rock (see Supplementary Fig. 4e), d steep uphill test on wet rock (see Supplementary Fig. 5k), e uphill test on muddy path (see Supplementary Fig. 4h).

The “maximum” force was either the highest applied force that the foot withstood without slipping, or simply the maximum force applied in the case where the foot did not slip. The plot has been visually separated into downhill and uphill tests, and the data points grouped to show the trend. Please note that most of the plotted forces above 40N were non-slips; therefore, the disparity between the state-of-the-art (SotA) and hoof in uphill conditions would be more pronounced.

It is important to note that most data points with forces exceeding 40N correspond to non-slip trials (i.e., the foot did not slip even under the maximum load applied), suggesting that the performance gap in uphill conditions may be understated. Additionally, while the SotA foot generally exhibits symmetrical performance around θ = 90°, an outlier at θ = 110° is observed. This deviation is attributed to rain during that trial, which further diminished the effectiveness of classical friction.

Overall, the results indicate that the hoof delivers more consistent traction across a range of inclines typical of alpine environments. This aligns with our hypothesis and supports the idea that edging can offer superior static traction where classical friction alone becomes insufficient.

Observations of the hoof during the experiments showed that edging and pad friction are important morphological features of natural hooves. The independent toes appeared to improve pad friction as they conformed to the surface and allowed for the toes to edge on different small features. In Fig. 5d, the sharp toe tips dug into the mud, causing significantly better performance, as predicted. In Fig. 5b, it was observed that the feature described in Fig. 2n was in use, outperforming the control even at a low θ.

Furthermore, on grass, the hoof outperformed the SotA foot, exhibiting more controlled slipping. This is because grass became trapped between the hoof’s toes, requiring the hoof to tear through it, thereby dissipating energy, in alignment with Fig. 2j. The hoof also showed promising performance using side edging compared to the SotA foot. Further details of these experiments and experimental data are provided in the Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2.

These results suggested that our situated heuristic-based design was successfully encoding mechanical intelligence into the hoof, creating a new quadruped foot with potentially enhanced traction in alpine terrain.

Experimental results under controlled conditions

To evaluate the performance of our engineered hoof, it is essential to understand its behaviour under both static and dynamic loading conditions. Furthermore, we aim to investigate the effects of different terrain inclinations, impact force levels, and initial conditions on hoof stability. To compare the hoof performance, a cube foot and a ball foot were used as controls (Fig. 7). The ball foot is constructed from the same soft rubber as the hoof pad, while the cube foot uses the same hard rubber as the hoof body. By comparing the hoof to these two controls, we gained insights into how the hoof’s performance differs from conventional friction mechanisms and basic edge designs.

To this end, we have designed a test rig (see Fig. 8) that vertically holds a spring-loaded boom. The hoof or control foot can be mounted at the lower end of this boom, with a load cell positioned in between. Various objects can be placed beneath the foot to simulate different terrain conditions. The compressed springs can be released with a latch mechanism to apply an impact force to the hoof (for more details, see Fig. 13 and the section ‘Experimental methods under controlled conditions’ for more information).

The spring mechanism was compressed to provide three levels of impact force: 76.61 N, 164.63 N, and 208.64 N, respectively (see the section ‘Experimental methods under controlled conditions’ for more information). Verifying this impact force data from the load cell, we observe that these values are approximately similar during the initial impact conditions, but because of the foot/hoof stiffness and its interaction with the terrain, a higher oscillating force was observed due to the weight of the boom, which can reach approximately up to 310.19 N. Therefore, this experiment simulates a condition similar to a goat dynamically placing its hoof on a rock. The interaction with the ground is influenced not only by the force exerted when the hoof makes contact with the terrain but also by the inertia of the limb and the body.

Reflective markers were placed on the respective test feet to record their feature’s 3D position through a calibrated motion capture system (see ‘Experimental methods under controlled conditions’ for more information).

A comparison of the interaction between the foot and the terrain in different scenarios is shown in Fig. 9, where the slippage behaviour of different foot features on an inclined slab is represented in 3D plots. Each sub-plot compares the slip distances of five foot types—hoof tip, hoof side edge, hoof base, cube foot, and ball foot—under identical impact force levels and terrain slope angles. The foot features were tested on two slope inclinations (43° and 50°), and three force levels (1, 2, and 3). For each foot type, five randomly selected marker trails are plotted per condition to illustrate variability in slip behaviour across test repetitions. From these plots, it can be inferred that as the impact force on the foot increases, the sliding distance increases for each feature. Additionally, when the slab inclination was increased from 43° to 50° and an additional load of 1.076 kg was added to the boom, even more slipping was observed in all the respective cases.

The slip trails were captured using a motion capture system by tracking a marker placed on each foot feature of interest. Each sub-plot compares the slip distances of five foot types—hoof tip, hoof side edge, hoof base, cube foot, and ball foot—under identical impact force levels and terrain slope angles. Two slope inclinations (43° and 50°) and three force levels (1, 2, and 3) were tested. For each foot type and condition, five randomly selected marker trails are shown to highlight variability in slip behaviour. Due to variations in setup and motion capture calibration, the starting points of the marker trajectories differed. To enable consistent visual comparison, the Z-positions of all trails were translated to begin at a height of 350 mm. The X-positions were offset to 10, 40, 70, 100, and 130 mm for hoof tip, hoof side edge, hoof base, cube foot, and ball foot, respectively, to prevent visual overlap between different foot types. Additionally, individual trails within the same foot type were offset using fixed spacing to reduce clutter. The variation in marker position along the X-axis was normalised to enhance visualisation of vibration along the Z-axis. All distance measurements are in millimetres (mm).

As a first observation, at a slab inclination of 43° and the lowest loading level 1, the ball foot performs reasonably well. The compliance of the ball foot material appears to provide a grip on the slab through material deformation23. However, as the loading increases, the slip distance increases severely. When the slab was inclined to a steeper slope of 50°, even the slip distance for force level 1 is considerably large, which gets much worse when the loading was increased further. This highlights that while the ball foot benefits from its soft material, it is not enough for handling higher loads or steeper slopes. A better foot design is needed for quadrupedal robots to move more reliably on uneven terrain. To observe median slip distances of different foot features, Fig. 11 can be followed.

Compared to the ball foot, the hoof tip showed similar performance under low loading at a 43° slope. However, unlike the ball foot, its performance did not worsen as much when the impact force increased at the steeper 50° slope. It seems that the stiffness and compliance in the pitch joint of the hoof help stabilise motion and reduce slip distance, suggesting that some degree of compliance in the foot design is beneficial. Similar behaviour is observed for the side edge of the hoof under low loading at a 43° slope. However, as the loading increased, the performance of the side edge deteriorated. In contrast, the hoof base performs exceptionally well in all scenarios.

To understand why the ball foot slips, one might consider that it lacks a sharp edge, which reduces its ability to engage or “edge” with the ground’s surface features and resist slipping. To assess this design alternative, we also tested the cube foot with edges similar to the front tip and side edge of the hoof. However, we observed that the median sliding distance of the cube foot is not less than that of the ball foot. The difference in the median slip distance is significant, where the cube foot performs worse than the ball foot (see Fig. 11 and Table 1). The edging phenomenon that seemed promising with the hoof testing in static loading conditions in outdoor settings performs moderately when tested standalone in dynamic loading conditions.

The outdoor tests clearly demonstrate that features such as pad friction and hard edges are crucial for reducing hoof slip. However, when these features are tested individually through the controls, their behaviour differs. This suggests that the interaction between these two parameters, when combined in the hoof, creates an integrated effect that significantly reduces slip. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of the hoof is crucial to comprehending how these features have evolved in mountain goats, and how they can be utilised for a robot foot.

To ensure the replicability of these results, we performed multiple trials of experiments for each configuration, varying the starting point location on the slab. These starting points are marked on the slabs shown in Fig. 14g. Using the slip trails recorded with the motion capture system, we calculated the slip distance for each trial. Distributions of the slip distances for all the trials that relate to each testing configuration are presented in Fig. 10. For the full selection of slip distance distributions, please see Supplementary Fig. 6.

If we consider that in any condition a slippage of about 250 mm is hazardous for the robot and will not allow it to gain stability, the cube foot only survives in level 1 loading conditions (Fig. 9). In contrast, the ball foot performs well for level 1 loading conditions and higher, when the terrain slope is (43°). The hoof tip survives in level 1 and level 2 loading conditions, whereas it marginally fails for level 3 loading conditions. The hoof side edge is stable in level 1 loading condition, whereas it becomes unstable in level 2 and level 3 loading conditions. In comparison to all the cases, the hoof base presents very low slipping without much variability in the slip distance.

The behaviours of different hoof features raise the question of what made one feature more effective than another at reducing slip when interacting with the terrain. To assess this, it is necessary to understand the transient behaviour of the hoof features and their usefulness in the hoof morphology during the interaction with the terrain. Specifically, we aim to investigate how the hoof vibrates upon contact with terrain features and whether any stick-slip phenomena occur. To portray it, we perform a wavelet transform on the marker tracking data acquired using the Vicon motion capture system. To evaluate the performance of various foot features, we calculate the slip distance distribution for all test trials conducted for each feature. The average wavelet transform across all trials is then plotted for each feature (Fig. 10).

In the average wavelet transform plots for all three hoof features, we observe multiple sharp vertical line elements with small gaps in the high-frequency range of 70–106 Hz. This line-gap-line behaviour indicates a slip-stick-slip phenomenon. During the line portion of the plot, slip occurs, generating high frequencies in the foot feature. Conversely, when there is a gap, the hoof feature sticks to the terrain, causing the vibration to dampen.

This phenomenon resembles the behaviour of an antilock braking system (ABS) in automobiles24, where the disk undergoes rapid cycles of stopping and releasing within a fraction of a second. The advantage of this braking phenomenon is the predominance of static friction. When the system transitions from static to dynamic friction, the force required to sustain motion decreases. Continuous locking and unlocking of the disc brake compels the system to predominantly utilise static friction, thereby facilitating more rapid vehicle deceleration. In the context of ABS, this phenomenon is achieved through electronic braking pulses25,26.

In our design, however, this behaviour emerges as an interaction between the morphology of the hoof and the slope. This inherent characteristic imparts passive dynamics to the foot, enabling it to dissipate energy more efficiently to achieve shorter slip distances.

To investigate the statistical significance of slip distance reduction across five hoof and control feet features, two ground slopes, and three loading conditions, a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed. Due to two slopes and three force levels, there are six cases for comparing the foot features. To understand the statistical significance, a null hypothesis is considered that assumes that the difference in slip distance between any two features in a given case is not significantly different. Using a significance level of α = 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected when the p-value is less than 0.01, indicating that the observed difference between the two groups is statistically significant.

Table 1 shows statistically significant differences in slip distances for pairs with “*” at the end of the corresponding p-values. When comparing slip performance between the cube foot and the ball foot, the ball foot remained significantly more stable on a 43° slope (statistically significant). However, as the slope increased to 50°, both foot types experienced greater slip distances, and the difference between them was no longer statistically significant. To clarify the variability in slip distances, Fig. 11 presents a box-and-whisker plot showing the median slip distances of five different foot features—the hoof tip, hoof side edge, and hoof base—compared with the cube foot and ball foot in their respective cases. The trends described above are clearly visible in these plots. Notably, the hoof base demonstrates outstanding performance. At a 43° slope, the ball foot exhibits slightly greater slip than the hoof base, although this difference is not statistically significant. However, at a 50° slope, the ball foot slips significantly more. The cube foot consistently slips significantly more than the hoof base under all conditions.

The hoof side edge shows significantly greater slip at lower load levels, where the hoof base performs better. With increased load, the hoof base also experiences higher slip, rendering the difference with the side edge statistically insignificant. The hoof tip follows a similar trend to the side edge, with no statistically significant difference in slip distance between the two. Nonetheless, inspection of the median slip distances in Fig. 11 reveals that, at a 50° slope, both the hoof side edge and hoof tip outperform the cube and ball foot across all force levels.

Furthermore, combining all the cases for one foot feature, our analysis revealed that the median slip distance for the hoof base is 75.6% shorter than that of the ball foot, and 79% shorter than that of the cube foot, both of which were used as control designs in this study. This substantial reduction highlights the effectiveness of the hoof base in minimising slip distance across varying terrain conditions.

Discussion

No matter how simple a robot’s hardware might be, when it is in contact with a natural environment, the coupled dynamics can exhibit non-linear and discontinuous state transitions. Therefore, a model-based design approach for stability, such as contraction analysis in the state space27, or high-fidelity simulations such as DEM21, can sometimes result in a system that differs significantly from predicted results. However, the analytical approaches that approximate non-linear dynamics to Linear Time Varying (LTV) systems show that the right kinematic functions (broadly referred to as morphology in this paper) in the robot design lead to contraction of the volume for the state trajectories over time leading to deterministic outcomes agnostic of the initial conditions27. In other words, correct morphological features in the hoof would lead to autonomous reduction in slip distance and severity even after the slip starts.

Studies on the evolution of species argue that the adaptations in the morphology of species are linked to those in their habitats28. Therefore, a change of habitat and population dynamics would lead to changes in the morphology of species. An example is how fish scales would adapt to minimise drag and how the shape and stiffness of the fish body would evolve to efficiently couple with turbulence in a stream to swim upstream5. In this way, the morphology of the organism and the morphology of the immediate environment form a closed circuit—a phenomenon for which the term ‘ghost circuit’ has been coined due to the transient nature of these natural systems29.

In the case of designing a hoof to allow a legged robot to be stable on slopes, the interplay between the hoof and its natural terrain introduces considerable complexity that challenges traditional analytical design methods. Unlike typical friction models for homogeneous contact surfaces, the time-varying and complex surfaces of natural rocks or grassy banks pose an enormous challenge to such approaches. The LuGre friction model is the most accurate frictional model that can be used30. This model accounts for more complex surface interactions, velocity, and acceleration by modelling each surface with bristles which can latch together. This modelling technique manages to simulate important and complex temporal features seen in friction such as stick-and-slip. Although this can be used to analyse a hoof design, the LuGre friction model still cannot represent constantly varying surfaces with contaminants and geometric features such as cracks, valleys, peaks and ledges. Furthermore, as noted in a review of foot-ground interactions, introducing a compliant foot with complex 3D morphology cannot be adequately modelled.

The nature of these complex ‘ghost circuits’, and the lack of a suitable paradigm to model them, provided the inspiration for the design approach described in this work29. A situated heuristics-based design approach for robots emphasises tuning morphological features to achieve mechanical intelligence with predictable, passive behaviour. This method is especially useful when the material properties and environmental interactions are complex and challenging to model.

The repeated testing we performed in alpine environments during the design process allowed the hoof design to evolve efficiently and be directly tuned toward the terrain of interest. Based on initial test rounds we were able to quickly confirm the potential of specific parts of the hoof morphology—that is, the hard, keratinous edge, and the soft lower pad—that had been identified in previous literature but remained broadly untested. Repeated testing allowed the combination of these features, and the desired compliance of the system, to be developed further in the synthetic design.

In parallel with its biological inspiration, the final hoof design exhibits two primary modes of operation, determined by the slope angle relative to the direction of motion. When moving uphill, traction is primarily achieved through an ‘edging’ effect using the hard, pointed tip. In contrast, during downhill movement, the soft pad becomes the dominant contact surface, maximising friction through increased compliance. This dual-mode functionality allows the hoof to adapt its mechanical properties to suit opposing demands. Alongside these two principal behaviours, the hoof also engages in numerous subtle and unpredictable interactions with natural terrain—such as trapping blades of grass between the toes or wedging its sharp tip into surface cracks—highlighting the complexity and adaptability of its morphology.

Designing comparatively simple robotic elements with specific environments in mind seems to present advantages over a more traditional ‘catch-all’ approach that is currently employed in state-of-the-art (SotA) quadrupeds. The final outdoor experiments performed in the Peak District National Park support this conclusion, demonstrating the improvement in performance of the hoof design over a representative SotA control. This increased stability can in turn reduce the need for more complex computational management, potentially resulting in simplified, lighter, and more efficient robotic systems. This use of morphological and structural features that interact with the chaotic natural environment to yield predictable responses, thereby reducing the burden on the central nervous system, is a core principle of embodiment and a foundation of biologically inspired robotics29,31.

Our method of design does have its drawbacks, namely the intensive design process, requiring rapid design and prototyping abilities along with regular access to the target environment. For instance, we created at least thirty-two prototypes and conducted eighteen rounds of testing, four in remote alpine-type environments in snow and rain. Consequently, an optimal solution may be unattainable, as achieving it would require an impractically high number of prototypes and testing rounds, much like the extensive time frames needed for animals to adapt using evolution. Furthermore, the resulting design functions as a kind of “black box”, much like evolution or machine learning, making it effective but challenging to extract generalisable insights or new design principles.

In this process, we did not use any numerical simulations to support the design iteration process. However, in future, an interesting approach would be to combine hardware experiments of multiple design variations in real environments with digital twins in simulated environments. This combination would allow for frequent validation of the simulated designs, while also utilising tools like Quality Diversity algorithms to generate promising designs within the parameter space, which could then be used to speed up the evolution of certain morphological features32.

To further evaluate its effectiveness, we conducted controlled laboratory experiments and analysed the resulting foot-terrain interactions using wavelet analysis to examine the frequency characteristics of stick-slip events.

In examining the detailed individual force level average wavelet plots for the tip’s interaction with the terrain (Supplementary Fig. 7), high-frequency stick-slip behaviour appears consistently across all force levels on the 43° slope and at lower force levels on the 50° slope. At the highest force on the steeper slope, a shift to mid-range frequencies occurs, correlating with increased slip distances (Supplementary Fig. 6). Similarly, the hoof side edge (Supplementary Fig. 8) shows consistent high-frequency stick-slip across all tests.

The hoof base (Supplementary Fig. 9) exhibits shorter-duration stick-slip, particularly at low force levels, where damping of the hoof vibration occurs rapidly and slip is effectively reduced. At higher force levels, the stick-slip behaviour is consistently observed over a short span of time, which appears to contribute to a more rapid decrease in slip distance. Supplementary Movie 1 shows evidence of high-frequency fluttering about the pitch axis, resembling a chopping action that promotes kinetic friction33.

In comparison to the hoof, the cube foot exhibits similar stick-slip behaviour, but the chopping phenomenon is noticeably weaker and less consistent across trials. As a result, high-frequency events occur sporadically, and mid-to-low frequency vibrations dominate throughout the slip motion. This suggests that the presence of a side edge alone is insufficient to consistently generate the multiple chopping events needed to dissipate energy through static friction. Both geometric features and structural compliance are essential to achieve the intended passive dynamic behaviour. The average wavelet plots for the cube foot (Supplementary Fig. 10) show that on the 43° terrain slope, stick-slip activity resembles that of the hoof’s side edge but with lower convolution, leading to comparable slip distances. However, on the 50° slope at force levels 2 and 3, the interaction is dominated by mid-to-low frequency components, and high-frequency stick-slip becomes irregular, resulting in increased slip distances.

In the case of the ball foot, high-frequency stick-slip events are observed but are more widely spaced (Supplementary Fig. 11) than those of the cube foot. This suggests that the ball foot primarily operates in the dynamic friction zone, resulting in greater slip distances. The dominance of low-frequency components further indicates limited engagement with static friction, reducing the foot’s ability to dissipate energy effectively. As a result, the ball foot experiences increased slip. Examining the detailed individual force level average wavelet plots, we observe that for the 43° terrain slope, the high-range frequency stick-slip behaviour is present at all force levels. However, when the terrain slope is increased to 50°, mid-to-low-range frequencies dominate, and the foot seems to be consistently sliding under dynamic friction, which causes an increase in the slip distance.

These experimental insights show that multiple morphological features are important to render predictable and goal-oriented passive dynamic behaviours under different interaction scenarios. While individual features such as sharp edges, tips of the digits, and compliant joints contribute to slip reduction, their functional value depends on how they respond to different environmental conditions such as the rough features on slopes, surface friction, etc. Therefore, a physically grounded design approach is needed, where the critical morphological features are iteratively tuned.

The complexity of the test environments also presents a problem when attempting to numerically quantify the effectiveness of the hoof prototype. The experimental techniques used in this study clearly demonstrate the potential of the hoof, and the design approach used to create it. However, the results are far from exhaustive, and further investigation would be necessary to demonstrate that the described hoof design represents a generally superior solution to the current state-of-the-art designs for robotic quadrupeds. Most obviously, comprehensive testing with a mature sensor-equipped quadruped robot in alpine environments would be necessary. Differences in local geology and climate, such as precipitation and temperature, also imply the need for testing in a variety of alpine locations, and additional non-alpine but equally difficult terrain. This would not only clarify the effectiveness of the hoof design and the morphological features it encodes, but also represent a further step in the situated heuristics-based process that would enable continued understanding and improvement of the design.

The design process presented in this paper was inspired by the difficulty of properly understanding the behaviour of complex mechanical parts removed from their environment, as this constitutes breaking the ‘ghost circuit’ that they form together. Controlled experiments do, however, still represent the best recourse when attempting to investigate the underlying principles that govern these systems, but they will always struggle to fully reproduce the behaviour of the systems in situ. Slipping is a complex process that involves multiple dependent factors. The laboratory experiments presented in this paper make an attempt to isolate specific variables of interest that are determined from observation of the foot designs in their intended environments. The combination of these experimental techniques forms the empirical backbone of the design approach.

In our results, we observed that the hoof base performs exceptionally well in dynamic scenarios, particularly in reducing slip. Under multiple impact loading conditions in structured testing, the hoof base stabilised rapidly with minimal slipping. In mountain goats, this hoof base appears to be a dynamic feature used when descending slopes or leaping between cliffs.

In outdoor static loading tests, we found that the hoof tip and hoof side edge perform particularly well. These features intrude into terrain irregularities, creating an interlocking effect between the terrain and the hoof’s compliant material and edges. Such characteristics are primarily beneficial in static loading situations, assisting in uphill climbing or descending slopes slowly by lodging securely into the terrain.

Each hoof feature, therefore, serves a distinct purpose, and goats employ them in a highly specific manner. The integration of all these features, in the right proportions and coupled with appropriate foot dynamics, enables these animals to traverse highly uneven terrains with remarkable agility and stability.

Comparing our design with other bio-inspired foot designs34,35,36,37,38,39,40 offers useful context, but direct comparisons are challenging. Many existing designs are scaled for specific robots, and rescaling them for our test rig could compromise their performance. Moreover, most were not tested under the same rigorous conditions used in this study, and some were evaluated only on full robotic platforms36,39,40, which we did not have access to. Given these limitations, we used primitive shapes as consistent and replicable baselines. Nevertheless, to ensure meaningful context, we have included a comparative qualitative analysis with bio-inspired foot designs available in the literature.

Among these, early implementations in the Oncilla34 and Cheetah-cub35 robots provide notable examples of bio-inspired foot strategies. These systems employed short feet with torsion springs at the leg ends to introduce passive compliance. While effective for basic locomotion, these designs primarily focused on spring-loaded ankle behaviour and did not explore detailed foot-terrain interaction. Building on this, a more advanced compliant foot based on granular jamming was developed for Oncilla36, using a latex membrane filled with rubber granules. The membrane could transition between fluid-like and solid-like states under vacuum pressure, mimicking the soft pads found in animal paws. However, this design omitted functional toe structures, which are believed to play a key role in force transmission and forward propulsion. Though the experiments performed were simple, they assessed sliding friction by pulling the platform laterally and evaluated damping by dropping it onto concrete from a height. Locomotion tests on flat ground demonstrated speeds on par with Oncilla’s fastest gaits.

Another notable bio-inspired design is an adaptive, compliant foot modelled after a salamander, aimed at replicating ground reaction force (GRF) patterns observed in the animal37. The prototype, scaled from the tiger salamander’s foot, used a simplified three-finger structure by fusing digits while preserving functional behaviour. Remarkably, it reproduced biological GRF patterns without active control, suggesting that its mechanical structure alone can generate complex locomotion dynamics. Experiments showed strong terrain adaptability and impact resilience without disrupting gait phases. However, this design has not been evaluated for locomotion over continuous uneven terrain or in scenarios involving slippage.

Chatterjee et al.38 introduced a multi-segmented adaptive foot inspired by avian anatomy, aimed at providing passive support while standing. The design resists both slipping and sinking, enhancing horizontal force generation on soft and hard substrates, and reducing sinkage compared to ball or cylindrical feet. In tests involving static leg pushes over different substrates, their two-segment foot performed poorly on sand but outperformed other designs on wood, stone, and pebbles. However, the evaluation was limited to static loading and did not address dynamic foot-terrain interaction.

In another approach, SoftFoot-Q40 is designed for quadrupeds with design principles derived in 41 to enhance stability by improving adaptability on uneven terrain and reducing slippage. The SoftFoot-Q was tested alongside ball and flat feet on the ANYmal robot. Across several trials, including gentle slopes (inclination < 25°), SoftFoot-Q outperformed the others, reducing slippage by 23.2% compared to ball feet and 34.9% compared to flat feet.

Compared to these prior studies, the present work advances the state of the art by introducing an iterative design strategy for a novel, bio-inspired hoof. Similar to the granular jamming-based foot in 36, this design features a soft footpad that provides both impact damping and enhanced traction across various surfaces. It also explicitly incorporates functional toes that actively engage terrain features, such as rock crevices or muddy banks, mirroring strategies used by animals in nature.

The design further integrates passive dynamic principles, as seen in the salamander-inspired foot37, enabling mechanical adaptation to varying locomotion demands. While the multi-segmented foot in ref. 38 shows strong static performance through horizontal force distribution, its dynamic behaviour on slopes remains untested. Although SoftFoot-Q provides valuable insights from full-robot tests, it does not emulate more advanced animal strategies like ridge anchoring or toe-edge insertion into deformable terrain.

In contrast, the hoof design presented here is evaluated under significantly harsher conditions. Static experiments were conducted on real, irregular terrain with slopes up to 50°, the steepest among the reviewed studies. These tests were performed in natural, not simulated, environments over multiple days, during rain and snow, conditions that may have damaged other foot designs. Fully modelling the transient interactions between a mechanical system and its environment in simulations or laboratory tests would be incredibly complex. In this paper, we proposed a different approach—a ‘situated heuristics-based design’ method that focuses on developing robotic elements directly in context, allowing for rapid evolution and tuning of a design to its environment. This method was used to design a mountain goat-inspired hoof, demonstrating the phenomenon that mechanical intelligence can emerge a deterministic dynamic outcome, such as slip resistance.

In both outdoor and laboratory experiments, we find that the compliance of the hoof supports its geometric features to enmesh with the slope, eliciting a deterministic outcome of shorter expected slip distances. We found that structural features developed in the hoof model allowed it to support higher loads without slipping on steep slope inclinations when compared to a state-of-the-art quadruped foot model. Features such as the two coupled but compliant hard-edged toes can autonomously find geometric and material features on the surface of slopes, such as edges, cracks, and soft mud, to produce meaningful interactions that improve stability. Controlled experiments show that forward slipping (toes facing downhill) exhibits the highest intensity of stick and slip episodes accompanied by a lowest expected distance of passive slipping under a load. The tips of the hoof digits and the side edge also show slip resistance superior to single-feature controls such as a rounded (isolating friction) or a cube-shaped foot (isolating edge interactions), which clarifies the inter-dependence of distinct morphological features. Further testing of the design on a state-of-the-art quadruped robot in varied alpine conditions is needed to fully confirm its general effectiveness and its performance in specific terrains. The results presented in this paper show the usefulness of taking a situated heuristics-based design innovation process to build mechanical intelligence that can generate passive dynamic outcomes by creating a ‘ghost-circuit’29 between the robotic part, such as a hoof, and the environment.

Methods

Situated heuristics-based design innovation process

To design the hoof, we took a situated heuristics-based design approach42, in which the hoof design rapidly evolved through interactions with natural terrain to emerge mechanical intelligence. We began with two simple, hoof-inspired designs based on fundamental morphological traits identified in previous research: a hard-edged aluminium ‘toe’ and a 3D printed dual-toe model with a rubber pad. From this starting point, we iteratively eliminated less effective features and further explored promising ones. Our strategy involved a rapid design-build-test-learn process, where tests served as preliminary evaluations to gain insights into feature effectiveness rather than providing conclusive proof of superiority. As this experimentation required the hoof to be tested in unstructured, alpine-type environments, we performed our major tests within the Peak District National Park due to its relative accessibility, and our minor tests on an assortment of rocks in the lab with different levels of contaminants (water, mud and plant matter). Details of this process are outlined in Fig. 12.

It starts with a set of assumptions about the key morphological features in the hoof that would effectively couple with envisaged features on natural slopes the hoof is tested. Real world tests inform what features should be kept and what can be removed. These features involve geometric features such as the toe and side edge shapes as well as structural features such as the compliance of certain areas in the hoof that would maximise the efficacy of the geometric features in slip resistance.

This iterative process, analogous to ‘selective breeding,’ led us to understand early on that although a rigid metal toe has the best static performance, a certain level of structural and material compliance is required to stop the hoof after slip ignition. Further independent compliance between the two toes was discovered to be a positive trait as it allowed each toe to self-select an edge with good traction, creating redundancy and extra traction. After the “Stage 2 Optimised Hoof” was created (Fig. 12), we undertook extensive experiments to test the hoof’s performance in comparison to controls, both outdoors in the UK Peak District and in the lab, as outlined in the ‘Results’ section.

The rubber material for the hoof was PU (Poly-Urethane) due to its properties, ease of prototyping and range of hardnesses. The hardness rather than the specific type of rubber was optimised through our design process, and vulcanised rubber (used in climbing shoes) or thermoplastic rubbers may have more suitable properties and should be explored. PU is durable, impact resistant, has good elasticity properties, and is resistant to weather and temperature. PU has high abrasion, water, and UV resistance and can work within the extreme ranges of natural temperatures, making it ideal for harsh outdoor environments. PU has predictable elasticity properties and can withstand a high load before permanently deforming and effectively absorbing shock and vibrations.

Design of SotA foot, ball foot and cube foot

Figures 3 and 7 show the four feet that were tested upon. The SotA (State-of-the-Art) foot was directly inspired by the foot that the ANYmal quadruped has used on outdoor expeditions2,43. The foot consists of a truncated hollow PU Shore-A 60 rubber sphere (diameter 55 m and wall thickness 4.5 mm) sealed onto a 3D-printed part. This creates a foot with high friction and conformability. Added tread mimics the ANYmal foot to help with traction. This foot was used during outdoor experiments to provide an indication as to whether the hoof is an improvement on existing state-of-the-art designs. Please note this is not identical to the ANYmal foot and was not provided by ANYbotics, but instead designed as an effective analogue.

Two control feet were used for lab experiments to isolate edging and classical friction. A 45 mm cubic control made from PU Shore-A 80 rubber, the same material as the hoof body, to test a foot designed only to edge and a 30 mm diameter ball foot made from PU Shore-A 60 rubber, the same material in the hoof pads, to test a foot designed only to use classical friction.

Field experimental methods within Alpine-type environments

To collect data in challenging environments, we designed a portable test rig capable of measuring the static frictional force limit and slip distance. This rig is built to withstand harsh weather conditions whilst being highly portable. The test rig (Fig. 4) has three inbuilt sensors. A single-axis force sensor measures the axial force applied by the rig to the foot, and two inclination sensors which, through forward kinematics, calculate the slip-distance of the foot. The force sensor was calibrated with a function generated from recordings of reference masses up to 6 kg. Inclination sensors were first calibrated by suspension from the laboratory ceiling for a period of several hours to allow them to stabilise, and setting the stable measurement as the zero point. During each outdoor trial, the stable position of the foot model prior to the addition of weight was used as a reference point from which slip distance was calculated. The lengths of the two rods, L1 and L2, were measured using a ruler, and the angle of the surface was measured using an external inclination sensor. To apply force to the test foot, we utilised precise 0.5 kg weights suspended from the rig as shown in pink in Fig. 4. The weights were carefully and slowly added at approximately 5s intervals until slipping occurred. This method allows for discrete force application, providing a low-precision measurement of the static frictional limit force but with sufficient resolution to differentiate performance between individual feet.

The hoof and SotA foot were faced frontward (e.g. Fig. 2a, c, i, l) on 12 different natural surfaces with a wide range of inclinations. We tested both the extremes of negative and positive slope angles as we wanted to study cases where the hoof would likely slip. In total, 121 individual experiments were performed on both feet, approximately five per foot per surface; all of these can be seen in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, and 5. Additional tests, such as side-edging and grassy slope trials, provided intriguing preliminary insights but lack sufficient data for strong conclusions; these results are available in the Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Experimental methods under controlled conditions

In our outdoor experiments, we primarily examined the foot-terrain interaction differences between the hoof and the control feet under various terrain conditions with static loading. These static loading tests provide insights into scenarios where a stable interaction is initially present, and an increase in the loading condition leads to foot slippage once the static friction threshold is surpassed. While these tests are informative for understanding and comparing foot feature performance, they do not capture the full spectrum of interactions that can occur between the foot and the terrain.

Typically, in the context of ungulates, scenarios such as careful walking, seeking a place to grip when climbing uphill, or slowly placing the hoof on a rock feature to descend downhill can be considered close-to-static interaction scenarios. However, activities like running and jumping uphill or downhill to avoid predation or to graze on difficult-to-reach vegetation require an understanding of the dynamic behaviour of hoof-terrain interaction. In these scenarios, interaction is facilitated by an impact force, with the foot approaching the terrain with comparatively higher force and velocity in comparison to the static tests.

To understand this behaviour, we require a setup that can reliably reproduce similar impact forces and interaction configurations for the hoof and control feet repeatedly. Therefore, we designed and fabricated a new test rig to perform dynamic experiments in indoor settings.

The rig designed for testing the hoof consists of a cuboid frame of aluminium profile sections measuring 680 mm × 380 mm × 770 mm. A sliding holder mechanism mounted on the top frame moves along the horizontal Y-axis, which is guided by rollers and a precision linear rail to prevent wobbling. A vertical aluminium boom is mounted onto the holder. This boom can slide freely up and down along the Z-axis, guided by linear rails to restrict movement in other directions. At its lower end, a 20 kg RS PRO compression load cell is installed to measure impact force, with the test foot attached below it. Together, the sliding holder and boom provide two degrees of freedom (2-DOF): one along the Y-axis and one along the Z-axis. To apply impact forces during tests, a spring-loaded mechanism is mounted to the holder. It uses two parallel compression springs (each with a stiffness of 1.63 N/mm) and a Maxon EC-40 motor to compress them. The springs are released manually using a latch, creating a controlled impact on the foot (Fig. 13). To mount the test slab at a specific angle, a rectangular aluminium frame is attached to the base structure. The inclination of this frame can be adjusted using fasteners, allowing for precise control of the terrain slope during testing.

In this test rig, the sliding holder and boom create a 2-DOF configuration that allows the foot to adapt to the terrain’s curvature and surface features, enabling natural sliding in response to vertical (Z-direction) forces. In biological or robotic systems, such horizontal movement is typically constrained by muscles or actuators (e.g., hip, knee, or ankle joints). However, in this setup, the horizontal movement was intentionally left unconstrained to isolate and investigate the mechanical behaviour of the foot independently of any active control mechanisms.

The terrain used in these experiments, a natural limestone slab, contained small perturbations as feature elements of 0–2 mm height. Such a terrain ensures that the features are neither too large, which would provide direct edging from the start and restrict foot movement immediately, nor too small, which would fail to provide any interaction details and make only initial static friction or foot material deformation as the primary source of frictional force. The top surface of the slab is shown in Fig. 14g. In some limited cases where foot sliding was excessive, we also used a sandstone slab with feature elements of 0–6 mm height to find out if the sliding was reduced. The top surface of this slab is shown in Fig. 14h.

Three markers were placed on each feature that contacts the terrain. In the case of hoof tip (a) and hoof base (c) a total of 6 markers were placed. Whereas, for hoof side edge (b), cube foot (d), and ball foot (e) 3 markers were attached to each. Apart from marker placement, this figure also represents how the features were placed against ridges (pictures on top a–e) and flat surfaces (pictures bottom a–e) in the initial position. Picture (f) showcases how cameras are pointed towards the markers in different orientations. The surfaces of the limestone slab (g) and the sandstone slab (h) were used for foot-terrain experiments with the test rig. Markings on the slabs indicate the different initial conditions considered in various tests performed.

To understand the dynamics of various hoof and control foot features, it is crucial to accurately determine their positions in 3D space. Given that the foot is composed of a deformable material, developing a mathematical model to write its dynamics would be cumbersome. Instead, an intuitive approach would be to capture the dynamics directly, thereby providing a more accurate representation of the interactions occurring in natural terrains. Therefore, we used a motion capture system to record the feature dynamics. For that, we utilised a Vicon Tracker motion capture system44. We installed four Bonita-10 cameras around the test rig. This system operates using infrared light, comprising a light source and a camera sensor that detects the reflected light. Reflective markers are affixed to the foot, which are tracked by the Vicon cameras. An illustration of the test rig with the Vicon camera setup is provided in Fig. 8b. Reflective markers were placed on the respective foot features to capture their interaction behaviour with the terrain. To recognise the position of any object in the 3D space, the motion capture system requires at least 3 markers placed on the object. In hoof tip and hoof base tests, 3 markers were placed on each toe to record the position of both toes. Therefore, 6 marker trails can be seen in Fig. 9 for these cases. For the hoof side edge and the other two control feet, only 3 markers were attached to the testing feature. A representation of the foot and attached marker orientations is presented in Fig. 14.

To visualize the objects we run Vicon Tracker 3.10.0 on a Windows 11 X-64 based computer. To visualize the markers appropriately we adjust the aperture, focal length, and focus of the individual camera. This is an important step to make sure that only the makers are visible in the capture system and that any other anomaly is either suppressed or moved out of the capturing frame. Furthermore, we used a 5-marker T-shaped calibration wand45 to calibrate the camera setup. At least 2000 wand counts were recorded, and for a preferred calibration, image error must not exceed 0.25. A new calibration was performed every day as the total dataset of foot-terrain interaction was recorded over multiple days. To track an object through the camera system we select 3 markers placed on any feature, create a virtual object, and provide names for each marker. Top, left, and right terms were used for marker names to distinguish between their data. Top marker data was preferred in all the calculations, but choosing any other marker would have not made any difference. To store each marker-related data a MATLAB script was used that communicates with Vicon Datastream SDK46 for MATLAB to store the camera sensor’s marker position data.

The hoof comprises three main features: tip, side edge, and base. The tip and the side edge are sharp, hard features, whereas the base is a relatively softer feature with a bigger contact area. To properly assess the performance of these features, we select 2 control feet (see Fig. 7). Firstly, a slab angle was determined by placing the hoof tip against the limestone slab and gradually increasing the slab orientation. The point at which the tip began to slide was considered as an almost-critical point—this slope was measured at 43°. At this slope, the tip is almost stable and does not portray a rapid movement in the tip if perturbed minimally. To determine a critical case an additional load of 1.076 kg was added to the boom and the slab angle was increased till the tip became highly unstable. This was done to ensure that the hoof would slide with minimal perturbation under the impact load. This approach was adopted to simulate conditions where the hoof is highly susceptible to slipping, thereby allowing for a more precise analysis of the factors that contribute to the prevention of hoof sliding. To test the five aforementioned features on these two slopes 43° and 50° of The springs were compressed in three levels, 23.5 mm, 50.5 mm, and 64 mm in level 1, level 2 and level 3, which provide an approximate impact force of 76.61 N, 164.63 N, and 208.64 N, respectively. Multiple trials of each of these combinations were performed to understand the reliability of the results. During the experiments, it was observed that the initial position of the foot influenced the resulting sliding distance. For instance, when the foot was placed on a ridge, the sliding distance tended to be slightly shorter compared to cases where the slip was initiated from a nominally rough, flat surface. To address this variability, multiple starting positions were selected across the limestone slab to initiate slippage. This approach allowed the inclusion of a diverse range of contact scenarios, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of slip behaviour across different terrain features. These starting points are marked on the limestone slab presented in Fig. 14g. The number of trials performed for each combination is presented in Table 2.

Data acquisition was synchronised with the PC clock so that both force and tracker data could be recorded for the same time period. Due to the time delay of this calculation step, the motion capture system recorded the data with a frequency of approximately 245 Hz instead of delivering it at 250 Hz, which was the acquisition rate requested in the MATLAB script. The load cell data was recorded with a 1000 Hz sample rate.

The data from the motion capture system and the load cell were recorded for 10 seconds for each trial. To calculate the slip distance, the first and last values of the top marker’s Y and Z positions were used. The sliding of the foot occurs in less than 2 s. An extended recording time was employed to ensure that if the foot stops or reaches the end limit, it does not restart the motion.