Abstract

Designing robotic grippers that integrate rich sensing with low degrees of freedom while maintaining high dexterity remains a critical challenge in robotics. Although high-resolution tactile sensing, particularly vision-based tactile sensing, has advanced considerably and been incorporated into grippers, most prior work has concentrated on fingertips, leaving the functional role of the palm largely overlooked. Moreover, the potential of the palm to provide actuation alongside support and tactile feedback still remains underexplored. Herein, this work introduces a tactile-reactive gripper that integrates an active tactile palm capable of both actuation and high-resolution vision-based sensing, together with reconfigurable compliant fingers equipped with fingertip tactile arrays. The resulting architecture enables multi-sensing fusion to support adaptive grasping and contact-rich manipulation through coordinated palm-finger interactions. Extensive evaluations, including YCB benchmarking, diverse in-hand manipulation tasks, fruit-picking, and industrial application cases, demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed active tactile palm in enhancing dexterity and sensing, enabling challenging tasks with only seven degrees of freedom. The results provide a new reference for the design of tactile grippers that combine mechanical simplicity with advanced perception and high dexterity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the primary interface between robots and their environment, robotic grippers have attracted significant attention for their role in enabling versatile tasks across manufacturing, agriculture, and, more recently, domestic and assistive services1. Beyond grasping objects of varying size, shape, and stiffness, many applications require dexterous capabilities that emulate or complement human in-hand manipulation2. Conventional single degree-of-freedom (DOF) parallel-jaw grippers, with fixed configurations, are limited to simple grasping and lack adaptability. This constraint has motivated research into anthropomorphic hands with higher DOFs and reconfigurable finger structures, offering enhanced dexterity and task flexibility3,4.

While a high-DOF design with more actuation units could broaden dynamic gripping and dexterous manipulation capabilities, increased DOFs inevitably introduce greater mechanical complexity and require more sophisticated control strategies5. To address this trade-off, several studies have explored reconfigurable multi-fingered robotic grippers that aim to balance actuation complexity with dexterous capability6,7,8. In parallel, recent progress in tactile sensing has enabled finer-grained perception and expanded the application scope of tactile-reactive grippers9,10,11,12,13. For example, Cong et al. embedded a 4 × 4 force-sensitive resistor array into a Fin Ray gripper to provide basic force feedback14. Chen et al. integrated compact strain gauge sensors into the beams of Fin Ray fingers, enabling precise control of contact force between the fingers and objects15. More recently, Huang et al. developed a triple-layer piezoresistive sensor with a resolution of 16 × 16, applied to a Fin Ray structure to enhance spatial tactile representation in imitation learning16. To achieve higher-resolution tactile information for manipulation and feedback control, several promising attempts have integrated vision-based tactile sensors, particularly the GelSight family17, into soft robotic systems18. She et al. embedded a miniature camera into a soft robotic finger covered by a rigid exoskeleton, achieving combined proprioceptive and contact tactile sensing19. Zhao et al. introduced the GelSight Svelte Hand, in which each finger consists of a semi-flexible backbone and a soft silicone skin with an embedded vision-based tactile sensor20. Liu et al. demonstrated the first integration of a GelSight sensor at the tip of a Fin Ray finger21, combining passive adaptability with high-resolution tactile sensing through embedded vision.

Despite recent efforts toward full-coverage tactile grippers that extend the perception area beyond the fingertips22,23,24,25, actuation remains predominantly restricted to the fingers. The interaction between the object and the palm is often overlooked, despite palm-object contact playing a significant role in many grasping and manipulation tasks26,27. Benefiting from the skeletal and muscular structure of the human hand, the metacarpal bones provide the structural foundation of the palm28,29. The palm connects to the wrist proximally and articulates with the five fingers distally, forming a central platform that links the two. This anatomical configuration not only allows the palm to flex but also enables it to envelop objects with a large contact area during grasping, corresponding to the power-palm and power-pad grasp categories in the GRASP Taxonomy30. Beyond its role in static grasping, the palm contributes significantly to fine, dexterous in-hand manipulations. Its functions can be categorized into three main roles: support, sensing, and actuation (Fig. 1a). When facing upward, the palm acts as a mechanical stabilizer that enables the fingers to manipulate an object28. Compared with a single finger, it also provides a much larger tactile sensing area, allowing perception of object geometry and material properties during interactions. In certain tasks, the palm further contributes to manipulation through functional actuation. For example, during bottle-cap opening, effective palm-object interaction in humans is enabled by coordinated reconfiguration of palm skeletal structures, most notably the carpal-metacarpal articulations. Such reconfiguration adjusts the contact area, contact orientation, and force distribution between the palm and the cap, increasing friction and enabling the fingers to rotate the bottle body and separate the cap.

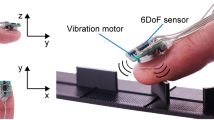

a Functional comparison between the human palm and the proposed robotic gripper with an active tactile palm. Three representative roles of the palm are illustrated: ① supporting the object on the palm to cooperate with the fingers during in-hand manipulation, ② providing tactile sensing of object geometry and material properties, and ③ actuating by pressing the palm on a bottle cap to enable in-hand cap removal. b The proposed gripper grasping a strawberry. c Mechanical design and overall structure of the proposed gripper. d Active palm module. A linear actuator is mounted on the base frame with three guide rails, enabling vertical sliding of the palm with a travel range of 0–20 mm. e Each finger is actuated by two servo motors and fabricated by 3D printing with TPU (95A). A tactile array sensor is mounted on the fingertip. f Three representative grasping configurations achievable with the proposed gripper.

Building on this biological inspiration, recent advances in palm tactile sensing, particularly through vision-based tactile sensors, have already achieved resolutions that surpass those of the human hand31,32,33. In terms of actuation, several studies have shown that introducing additional DOFs into the palm can improve gripper flexibility, especially in combination with compliant fingers28,34,35,36,37. From a sensing perspective, while tactile sensors on grippers have been widely adopted to capture local contact features, the integrated sensing of contacts from both the fingers and the palm remains insufficiently investigated, especially given the heterogeneity of their sensing modalities. Moreover, these heterogeneous signals differ in spatial structure, which may limit their effective use for manipulation without an explicit fusion mechanism. Effectively leveraging multi-sensory information therefore requires a dedicated fusion network for contact-rich manipulation. Addressing these gaps requires innovative gripper designs that combine mechanical adaptability with dense tactile sensing, enabling contact-rich and more challenging dexterous in-hand manipulation tasks.

Inspired by the multifunctionality of the human palm, we posit that equipping a tactile palm with simple linear actuation, together with reconfigurable multi-fingers endowed with tactile sensing, provides a practical way to emulate the highly coupled and hybrid passive-active functional roles observed in human manipulation, thereby enabling tactile-reactive grippers to achieve more human-like dexterity.

Herein, this study introduces a novel robotic gripper that integrates three compliant fingers with an active tactile palm, enabling dexterous in-hand manipulation through multi-sensory fusion (Fig. 1b). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to integrate an actuated vision-based tactile palm into a multi-finger gripper for dexterous manipulation, thereby combining actuation and high-resolution tactile perception in a single palm structure. The key contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Inspired by the role of the human palm in daily manipulation, we present a three-finger gripper featuring reconfigurable Fin Ray compliant fingers and an actuated tactile palm. The design integrates multiple tactile-sensing modalities, combining fingertip tactile arrays with a vision-based GelSight sensor embedded in the palm. This configuration allows the palm not only to act as a passive support surface but also to actively contribute to manipulation and perception.

-

2.

We propose a multi-sensory control framework that coordinates finger kinematics with dense tactile feedback from the active palm, ensuring secure, adaptive, and perception-driven contact during manipulation.

-

3.

We validate the effectiveness of the proposed system through extensive experiments on a wide range of objects. The results confirm the advantages of incorporating an active tactile palm, demonstrating robust grasping and dexterous in-hand manipulation capabilities. More broadly, our findings establish a new reference for designing low-DOF tactile grippers that combine simplicity with high dexterity.

Results

Design of 7-DOF tactile-reactive gripper

The design objective is to achieve multi-modal sensing fusion combined with dexterous motion capabilities, thereby enabling both robust grasping and fine in-hand manipulation. Figure 1c presents an overview of the proposed gripper, which consists of three fully actuated and kinematically identical fingers. For the active palm design, the motion is constrained to be perpendicular to the palm surface (Fig. 1d). This is realized by mounting a linear actuator inside the base frame, providing a maximum stroke of 20 mm, and mechanically linking the output rod to the palm base. A GelSight Mini sensor38 is mounted on the top of the palm base, while the bottom contains three hollow rings that are guided by rails integrated into the gripper base frame. This structural arrangement reduces interference between the palm and the fingers, thereby enlarging the gripper’s effective workspace. Detailed dimension is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

For the finger design, each finger is capable of performing anthropomorphic radial-ulnar deviation and flexion-extension motions of the proximal phalanx. Together with the 1-DOF actuation provided by the active palm, the gripper has a total of 7-DOF. The two-DOF from the finger are actuated by a pair of orthogonally arranged rotary motors located at the finger base (Fig. 1e). The compliant finger is fabricated by thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) materials, which provides compliance for grasping objects of varying geometry without explicit contact modeling. At the fingertip of each finger, a 16 × 8 tactile array sensor (50 × 25 mm2), adapted from 16, is integrated. Changes in resistance under applied pressure transduce mechanical stimuli into electrical signals, with a spatial resolution of approximately 3 mm2 per element. This thin and flexible tactile array delivers rich spatial contact information, such as contact location and grasping force, which can be extracted through feature mapping.

At the initial position, the three first-joint servo motors are mounted on the gripper base frame at the vertices of an equilateral triangle. The second joint is initialized such that the contact surface of the Fin Ray finger is parallel to the rotation axis of the first joint. The first joint, connecting the palm and the finger, provides radial-ulnar deviation with a range of ±60°, while the second joint enables flexion-extension with a range of +30° (inward) to −60° (outward). Owing to the large rotational range of the first joint, the gripper supports three grasping configurations (Fig. 1f): a cage grasp for large spherical objects and enabling in-hand rotation, a parallel pinch for small and thin objects, and a power grasp for heavy tools such as a drill or hammer. Detailed fabrication processes are provided in the “Methods” section.

Manipulability and workspace

Since all three fingers of the proposed gripper are kinematically identical, the net forces acting on the object or the overall manipulability in space can be regarded as the superposition of three identical contributions. Therefore, the analysis can be simplified to a single finger. Considering the translational manipulability of one finger, we assume that the finger is rigid and that the midpoint of the fingertip is used as the contact position.

In general, manipulability characterizes the ability of a robotic finger to generate motions or forces in arbitrary directions within its workspace, typically represented through the properties of the Jacobian matrix. To evaluate the kinematic performance in this work, two metrics are selected following39,40,41. The isotropy index μ, defined as the inverse condition number of the Jacobian matrix \({\bf{J}}({\bf{q}})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3\times 2}\), evaluates the isotropy of manipulability and reflects how uniformly motions can be generated in different directions:

where \({\bf{q}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2}\) is the joint position, and \({s}_{\min }\) and \({s}_{\max }\) are the minimum and maximum singular values of the Jacobian, respectively. Besides, Yoshikawa manipulability ω quantifies the overall magnitude of manipulability and is proportional to the volume of the velocity ellipsoid39:

A smaller condition number, corresponding to a larger value of μ, indicates that the manipulability ellipsoid is closer to a sphere. This implies that the fingertip motion induced by joint movements is more uniformly distributed in space. In contrast, a larger manipulability volume ω suggests that the fingertip has greater freedom to move in all directions at a given configuration. The isotropy analysis revealed a favorable distribution of performance across the workspace (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Approximately 30.8% of the configurations exhibited strong kinematic performance (μ ≥ 0.8), while 41.8% demonstrated medium performance (0.2 ≤ μ < 0.8). In contrast, 27.4% of the workspace showed poor isotropy characteristics (μ < 0.2). The distribution of ω is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b and exhibits a similarly non-uniform, but well-structured pattern. While the minimum value of ω = 84.9 occurs at an isolated near-singular configuration, more than 90% of the workspace maintains manipulability values over an order of magnitude higher, indicating that low manipulability is confined to a small subset of extreme configurations rather than representing typical behavior. It is worth noting that the 2-DOF finger design appears to lack sufficient kinematic redundancy, which constrains the system’s ability to avoid singular configurations. This limitation arises because the current analysis considers only finger mechanisms and does not account for the active tactile palm, whose contribution cannot be readily captured by existing manipulability metrics. As shown in later sections, the active tactile palm substantially enhances overall manipulation capability and provides additional effective degrees of freedom that help mitigate these kinematic constraints.

The workspace of the gripper was estimated using a Monte Carlo method combined with forward kinematics, based on the joint limits of each finger. Within the feasible rotation ranges, 5000 random joint angle samples were generated for each joint. The corresponding fingertip positions were then computed and plotted in a 3D coordinate system, and the set of all sampled points was used to approximate the overall workspace of the gripper. The object-level workspace was defined as the union of the convex hulls formed by the fingertip positions of the three fingers. The results (Supplementary Fig. 2c) demonstrate that the gripper achieves a broad and effective coverage around the base coordinate system, with an estimated convex hull surface area exceeding 440 cm2. Based on the single-finger coordination defined in Supplementary Fig. 1, the workspace of an individual finger spans 177.6 mm along the X-axis, 261.9 mm along the Y-axis, and 46.8 mm along the Z-axis.

Grasping capability

The grasping capability of the proposed gripper was evaluated using the YCB Gripper Assessment Benchmark42. A total of 28 objects with diverse geometry, weight, and softness were selected from the YCB object set43, as shown in Fig. 2a. Experiments were conducted across all object categories using each of the gripper’s three grasping configurations.

a YCB object set. b The proposed gripper performing three grasping configurations: cage grasp (left two columns), parallel pinch (third column), and power grasp (last column). c Results of the YCB Grasping Capability Assessment Benchmark. For rigid objects, each square is divided into left and right halves, representing the lifting and rotation stages, respectively. Each stage was scored based on completion. Tests were repeated at the origin position \({\mathcal{O}}\) and under 1 cm offsets Δx, Δy, and Δz. For articulated objects, only the lifting criterion is evaluated. The 20 cells indicate grasp outcomes, with yellow denoting success and blank cells denoting failure. The top two rows also show the best grasping configuration for each object and the corresponding tactile feedback during grasping.

The benchmarking procedure followed a standardized protocol. First, the gripper was moved to a predefined grasping position and the fingers were closed around the object. Next, the gripper lifted the object vertically by 30 cm and held it for 3 s. Following the lift, the gripper was rotated about the y-axis of the end-effector frame and held in the rotated position for another 3 s. Lifting and rotation were scored independently, with each action contributing up to 2 points: (1) 0 points if the object was dropped; (2) 1 point if it was retained with visible motion (slip); and (3) 2 points if it remained stable throughout. For articulated objects in the YCB object set, only the lifting stage was evaluated according to the benchmark definition, and no rotation score was assigned. In this case, a successful grasp was defined as lifting the object without falling.

To evaluate robustness under positional uncertainty, each object was tested in four different initial placements. First, the object was placed on a 1 cm-thick platform on the table, and the grasping procedure described above was executed. The same procedure was then repeated with the object displaced by 1 cm along the x- and y-axes of the local table frame, respectively. For z-axis perturbation, the platform was removed so that the object rested directly on the table, lowering its height by 1 cm. Z-axis perturbation was applied only to spherical and tool objects, but not to flat objects. Grasping scores were recorded for all objects across the four placements.

Similar to 23, fingertip tactile arrays were used to control an adaptive grasping strategy. Specifically, a threshold-based controller mapped tactile feedback to grasping force, as detailed in the “Methods” section. Unlike 23, the additional palm DOF allowed the tactile palm to be actuated after a grasp was secured, actively sensing the surface geometry of the object. This provided dual feedback from both fingertip and palm sensors. Representative grasping trials are shown in Supplementary Movie 1 and Fig. 2b. The gripper was mounted on a UR5e arm (Universal Robots Inc.), and each object was tested with all three grasp configurations. For each object, the best performance across configurations is reported in Fig. 2c.

Relying on fingertip tactile feedback, the gripper demonstrated strong performance on round objects. For the smallest spheres, however, the inward finger angles resulted in minimal contact area, leading to a lack of tactile feedback and grasping failures when lateral offsets were introduced along the x- or y-axis. Similar failure cases occurred for thin objects such as small-sized washers, where excessive inward angles prevented stable contact. Overall, the gripper achieved scores of 136/144 (94%) for round objects, 24/96 (25%) for flat objects, and 111/128 (87%) for tools.

For articulated objects, the proposed three-finger design showed some limitations compared with four-finger grippers8,23, particularly when grasping heavier chains with low friction, where slippage occurred. In contrast, for ropes with higher friction, the three-finger cage grasp succeeded in all cases. The gripper achieved a score of 15/20 (75%) for articulated objects.

Overall, the proposed gripper obtained a total score of 286/404 (71%) in the YCB Gripper Assessment Benchmark, outperforming previous works, including the hydra hand8, the GTac-Gripper23, and the RUTH gripper44 by 7%, 6%, and 15%, respectively. These results demonstrate that integrating tactile sensing with the proposed gripper enables adaptive grasping of objects with diverse positions, shapes, sizes, and weights.

Repeatability

We follow the benchmark described in ref. 45 to evaluate the repeatability of the proposed gripper. Specifically, the finger is first commanded to a reference (home) pose and then driven to three distinct disengaged poses, selected such that all degrees of freedom of the finger are actuated and joint loading from the reference configuration is fully released. The finger is subsequently returned to the reference pose, and the resulting positional deviation is measured using a plunger-style digital indicator (DIGR-0105, Clockwise Inc.). Since all three fingers share identical kinematic and mechanical designs, a single representative finger is selected for evaluation.

In addition to the finger, repeatability testing is also conducted for the active palm. As the palm mechanism has a single translational degree of freedom, only one additional disengaged pose beyond the home position is required to fully excite its motion range. The palm is repeatedly commanded between the home position and the disengaged pose, and the positional deviation upon returning to the home position is recorded using the same measurement setup.

Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie 2 (n = 35 trials) present the results. The finger achieves a mean positional error of 0.4311 ± 0.0317 mm, while the palm exhibits a smaller error of 0.0377 ± 0.0090 mm. These results indicate high positioning repeatability and mechanical robustness, particularly in light of the compliant nature of the finger design.

In-hand manipulation capability

To evaluate the in-hand manipulation capability of the proposed gripper, five standard test objects were selected from ref. 44, including a Rubik’s cube, two cylindrical objects with diameters of 40 mm and 60 mm, a 50 mm hexagonal prism, and a 50 mm square prism. All prisms had a height of 100 mm. The objects were indexed from 1 to 5, each with an ArUco marker attached to the top surface for pose tracking. The coordinate system definition is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. For in-hand translation tasks, three trajectories were tested: 50 mm along the x-axis, 50 mm along the y-axis, and 20 mm along the z-axis. The x- and y-axis displacements were chosen to ensure fair comparison across all objects rather than to represent the gripper’s maximum reachable workspace. The z-axis translation was constrained by the stroke of the linear actuator. The target angular displacement was 15° around the pitch, roll, and yaw axes. For in-hand rotation tasks, the target rotation was selected to ensure stable and repeatable evaluation across all objects. The maximum achievable in-hand rotation in pitch and roll is object-dependent. Rubik’s Cube with a low center of mass can achieve stable rotations exceeding 30°, whereas for the remaining prism-shaped objects with a height of 100 mm, rotations beyond ~15° often resulted in unstable contact. A similar limitation applies to yaw rotation when a single maneuver is required to be valid for all objects. Therefore, 15° was adopted as a conservative target rotation for all objects in the pitch, roll, and yaw directions.

Controller design for in-hand translation was based on kinematic modeling and finger motion planning. Relying on the simplified point-contact model (Supplementary Fig. 4 and detailed in the Supplementary Notes), and parameterized by the known object width, we constructed a closed-loop kinematic framework to compute the target finger positions required for the desired translation, from which finger trajectories were subsequently planned. In contrast, because of the higher complexity of object rotational kinematics, in-hand rotations were implemented with a threshold-based controller that used ArUco marker feedback without explicit motion planning.

The object state is defined as \({\bf{x}}=[x,\,y,\,z,\,\theta ,\,\phi ,\,\psi ]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{6}\), where (x, y, z) denotes the Cartesian position, and (θ, ϕ, ψ) correspond to pitch, roll, and yaw angles, respectively. The tracking error is defined as the difference between the final state and the target state along each dimension. Supplementary Movie 3 and Fig. 3a present the in-hand manipulation experiment. Fig. 3b reports the translation errors and their distributions (n = 10 trials). For in-hand rotations, only rotational errors were evaluated, since coupled finger-palm kinematics inevitably induced translation. The results are shown in Fig. 3c (n = 10 trials). The tracking errors demonstrate robust performance: most translational errors along the x-, y-, and z-axes were within 0–7.5 mm, while rotational errors remained within 0.1 rad. The only exception occurred during y-axis translation of the hexagonal prism, where larger rotational errors arose due to limited contact areas (single-edge contacts) between the object and the fingers. For in-hand rotations, all rotational errors were within 0.1 rad.

a Five selected standard objects and their assigned IDs. b Overlay snapshots of in-hand object translation and rotation along + x, + y, + z, + θ, + ϕ, and + ψ (from left to right columns), showing both the initial and final states. Each row corresponds to the in-hand manipulation of one object. c Error distributions for in-hand translation tasks, including displacement and rotational errors. d Error distributions for in-hand rotation tasks, including rotational errors.

It is worth noting that the active palm contributed substantially to dexterity during in-hand manipulation. For example, z-axis translation was achieved solely through the palm DOF, while larger rotation angles were obtained by pushing the object against the palm edge. In addition, owing to the large radial-ulnar deviation workspace provided by the first joint of each finger, the proposed gripper has the potential of performing in-hand translations along arbitrary directions within the x-y plane. These results demonstrate that the proposed gripper with an active palm enables precise and omnidirectional in-hand manipulation in Cartesian space. To further demonstrate tracking performance, the translation and rotation trajectories of the Rubik’s cube are reported as a representative example in Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6.

Multi-sensing perception and classification

While the grasping benchmark primarily relied on fingertip tactile arrays for grasp control, this section evaluates the multi-sensing perception capability of the proposed gripper using object classification as a representative task. A total of eight objects (Fig. 4a) were selected, which can be divided into two categories based on geometry: (1) cylindrical beverage cans of different sizes, and (2) spherical objects of varying sizes and materials. The multi-sensing system of the gripper consists of three modalities: fingertip tactile arrays \({I}_{array}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{16\times 8\times 3}\), palm tactile images \({I}_{image}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{320\times 240}\), and proprioception signals from servo motor encoders \({{\bf{q}}}_{prop}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2\times 3}\).

a The selected objects for classification. b Multi-sensing cross-attention fusion network. The tactile difference image is processed through a visual encoder, while tactile arrays are processed through a multi-layer perceptron, then combined with proprioceptive inputs and fed into the cross-attention module. For each sensing, queries are generated from the modality itself, while keys and values are derived from all other sensing. The attended representations from each are concatenated and passed through a fusion layer to produce a unified representation. Finally, an MLP classifier is utilized for object classification. c Classification results across different sensing modalities. All sensing fusion achieves the highest overall classification accuracy of 98.96%.

We designed an automatic data collection platform that allowed the gripper to grasp objects in a palm-down orientation. For each object, 120 trials were collected (Supplementary Fig. 7a). As shown in Fig. 4b, the classification framework employed a ResNet1846 encoder (pre-trained and frozen) for the palm tactile images, and a multilayer perceptron (MLP) encoder for the fingertip tactile arrays. The extracted feature vectors, together with normalized proprioception data, were then passed to a cross-attention fusion module, and the fused feature were classified using a three-layer MLP. Detailed network architecture and parameter settings are provided in the “Methods” section and Supplementary Fig. 8.

To validate the effectiveness of multi-sensing fusion, we conducted an ablation study using identical encoders across modalities and the same cross-attention module for feature fusion. The classification results are shown in Fig. 4. As illustrated in the dataset visualization (Supplementary Fig. 7b), single-modality performance was lower due to task-specific challenges: palm tactile images struggled to discriminate cans with similar ring textures; fingertip tactile arrays were limited by similar grasping poses and small diameter differences between cans; and proprioception alone yielded the lowest accuracy, as objects with similar geometry produced nearly indistinguishable joint readings. The single-modality accuracies were 90.62%, 92.19%, and 86.45%, respectively. Dual-modality fusion improved performance, achieving accuracies of 93.23%, 94.79%, and 91.15%. Confusion matrices are presented in Supplementary Fig. 9a to Supplementary Fig. 9c. In addition, we conducted ablation studies comparing the proposed cross-attention fusion module with three alternative strategies: (1) direct concatenation, (2) self-attention fusion, and (3) a simplified cross-attention variant that concatenates attention outputs without the fusion layer or residual MLP. All methods are trained under identical protocols and hyperparameter settings, with the feature fusion strategy being the only varying component. When all methods were provided with all sensing modalities as input, the proposed approach achieved the highest classification accuracy of 98.96%, outperforming direct concatenation (95.83%), self-attention (96.35%), and the simplified cross-attention variant (96.88%) by 3.13%, 2.61%, and 2.08%, respectively.

3D visualization of the multi-modal attention space (Supplementary Fig. 9d) and attention distribution (Supplementary Fig. 9e) demonstrated adaptive sensing selection, dynamically adjusting the contribution of each sensing according to object characteristics. Compared with existing tactile-reactive grippers that typically combine only a single tactile modality with proprioception such as refs. 5,9,10,12,16,19,23,47, the proposed gripper leverages multi-tactile sensing fusion to extract effective object-contact features. This not only enhances classification performance but also provides a promising foundation for downstream tasks such as visualtactile policy learning16,48,49.

Fruit picking

Using robotic grippers for fruit harvesting, particularly for fragile fruits such as strawberries, requires precise coordination between dexterous finger motions and fingertip tactile feedback. While previous grippers have demonstrated effective performance in strawberry picking or harvesting through novel structural designs50,51,52, their applicability has largely been limited to a single type of fruit. In this section, we leverage the compliant finger design and multi-sensing capability of the proposed gripper to evaluate its performance in fruit picking, in addition to its general dexterous manipulation capabilities.

The strawberry was selected as the test object, and the gripper was configured in the parallel pinch mode using threshold-based controllers (n = 5 trials). Figure 5a shows experimental snapshots. During T1−T2, the robot arm descended toward the table while the two opposing fingers were actuated under controller feedback, with the third finger kept fixed. Once the fingertip contact thresholds were exceeded (T3), finger motion stopped and the active tactile palm was engaged to contact the strawberry surface, providing high-resolution surface geometry information while simultaneously stabilizing the grasp. It is worth noting that during the gentle pressing of the tactile palm, the gripper was also capable of estimating fruit hardness, as demonstrated in ref. 53. Finally, at T4, the robotic arm lifted the gripper to complete the picking process.

a Demonstration of the proposed gripper picking up a strawberry from a desk. The two tactile array sensors in the parallel pinch configuration provided force feedback for handling the fragile fruit, after which the active palm moved downward to contact the fruit surface, stabilizing the grasp while capturing its surface geometry. b Qualitative results of the gripper performance on fragile fruit. The first row shows images captured under incandescent light, and the second row under UV light. Surface images of the same strawberry before and after the experiments are compared with a naturally bruised fruit. By day 4, the naturally bruised fruit exhibited darker coloration under incandescent light and larger recessed regions under UV light, whereas the experimental fruit showed no visible bruising. c Demonstration of the gripper picking and placing various fruits to assemble a fruit plate. d Tactile features sensed on the five fruits by the proposed gripper. The first column shows the GelSight tactile depth image from the active palm, and the last three columns show the tactile array signals from the fingers.

To evaluate whether the grasping process caused damage to the strawberries, we adopted the bruise detection method from ref. 54 using ultraviolet (UV) light. Compared with images captured under incandescent lighting, bruises are more easily identifiable to the human eye under UV illumination54. Following this approach, we designed a UV light box with two UV lamps mounted beneath the box top to provide an enclosed imaging environment, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 10. Fig. 5b shows the condition of the strawberries from day 1 to day 4 (left to right). The first row presents images captured under incandescent light, while the second row shows images under UV light. In addition to the experimental fruit, a naturally bruised fruit was included as a comparison. Bruised areas gradually enlarged over time and were particularly prominent under UV light, appearing as recessed regions. Under incandescent light, bruised regions were also visible as areas of darker coloration. Nevertheless, as shown for both the front and back of the experimental fruit, no visual bruise/damage features were detected after 4 days.

To further demonstrate the adaptability of the proposed gripper for picking different types of fruit, we conducted a fruit-plating experiment in which the gripper successfully picked five kinds of fruit without causing damage—strawberry, guava, tomato, kiwi, and grape (corresponding to T1-T5)—as shown in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Movie 4 (n = 11, total number of trials). In this experiment, to highlight the role of the active palm in object geometry perception, the grasping pose of the robot arm was predefined from an external RGB-D camera (RealSense D415, Intel), and the placing poses were also predefined. The gripper relied on tactile image feedback, using the same image encoder as in the previous section, to classify the fruits and place them into different subsections of the plate. The tactile feedback for different fruits, including palm tactile images and fingertip tactile arrays from all three fingers, is shown in Fig. 5d. These results demonstrate that the proposed gripper can successfully handle fragile fruits, highlighting its versatility and generalizability.

Applications

Finally, we demonstrate several applications that integrate the dexterity and multi-sensing capability of the proposed gripper, primarily involving in-hand manipulation.

The first application is an industrial task of installing a light bulb (Supplementary Movie 5). Different from previous task settings in which screwing was performed with the socket positioned on the ground and the gripper inserting the bulb from above47,55, our task requires inserting the bulb upward into the socket, which is more challenging: the gripper not only need to apply torque for rotation but also maintain an appropriate upward force to insert the bulb base into the socket, rather than relying on gravity as in the downward installation scenario.

The experimental setup involved the light bulb being initially placed vertically in a packaging box, with the following assumptions: (1) the bulb was placed upright with known initial x- and y-coordinates (but unknown height), and (2) the trajectory and target in-hand manipulation (insertion) pose were known. Based on this, Fig. 6a shows snapshots of the experiment. At T1, the gripper was configured in the parallel pinch mode to enable grasping within the narrow packaging box. The robotic arm then used the tactile palm to explore along the z-axis and determine the palm’s location until the contact mask exceeded a threshold (T2). This was followed by tactile-array-based grasping using a threshold controller, after which the arm moved the light bulb to the insertion pose. At T5, the gripper was switched to the cage grasping configuration, and from T6 onward, in-hand manipulation was initiated using a model predictive control (MPC) for tactile-reactive manipulation9,56, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. The active palm controller facilitated stable pushing contact by regulating the contact area between the palm surface and the light bulb. Analysis of the palm pushing maneuver revealed a strong correlation between contact area and palm actuator displacement (Fig. 6c, R2 = 0.994). By incorporating this kinematic relationship into an MPC scheme, the system could dynamically adjust contact geometry to maintain consistent pushing forces throughout the manipulation task. More details of the tactile-MPC controller are provided in the “Methods” section. Finally, the three fingers of the gripper executed repeated grasp-rotate-release cycles until the bulb was fully inserted and lit at (T6). In addition, Fig. 6d shows the commanded active palm position and the corresponding changes in contact area during the in-hand manipulation process from T6 to T8. We evaluated the final in-hand manipulation stage, and under the experimental assumption that the lightbulb remained upright throughout the trial, the proposed gripper achieved a 100% success rate (n = 10 trials).

a Demonstration of the proposed gripper completing upward light bulb installation. The gripper first employed the pinch configuration to explore the z-axis position of the bulb using the tactile palm (T1-T2), then grasped the bulb based on fingertip tactile feedback, moved to the installation pose, and switched to the cage grasp configuration (T3-T5). During in-hand manipulation (T6-T8), the tactile palm dynamically adjusted the contact geometry to maintain consistent pushing forces, while the three fingers executed repeated grasp-rotate-release cycles until the bulb was fully inserted and lit (T8). b Control loop integrating the active tactile palm for completing the light bulb installation task. c Verification results showing a strong correlation (R2 = 0.994) between contact area and palm actuator displacement, forming the basis for the MPC model. d Active palm position commands and corresponding contact area changes during in-hand manipulation (T6-T8). e Failure cases highlighting the importance of the palm: the bulb cannot be correctly inserted (misalignment) without palm support (left), and excessive palm force generates friction that prevents rotation (right). f Threshold-based control loop for in-hand object reorientation using fingertip tactile arrays for pose estimation and finger actuation for pose adjustment. g In-hand reorientation of a grasped cylindrical object. h Error distribution of the final estimation error under three target orientations. i Demonstration of the active palm perception for artificial strawberry identification and picking. j Demonstration of the syringe actuation.

To further demonstrate the functionality of the active palm in this task, comparative experiments of two light bulb installation scenarios are presented in Fig. 6e. The left panel shows a failure case when the palm was fixed: without supportive force from the palm, the light bulb could not be smoothly inserted into the socket to properly engage with the threads, resulting in misalignment. The right panel shows another failure case when a large force was applied, where the active palm was commanded to reach its maximum displacement (20 mm) through interpolation. However, the excessive friction generated at the socket interface prevented the bulb from rotating, leading to installation failure.

The second application demonstrates in-hand object reorientation (Supplementary Movie 6), leveraging both fingertip sensing capabilities and the gripper’s kinematic dexterity. In this task, the gripper grasps a cylindrical prism (90 mm diameter) with a textured contact surface featuring raised protrusions. The system utilizes the finger tactile arrays to estimate the grasped object’s orientation and employs the third finger to reorient the object to target poses along the negative pitch axis.

This reorientation task was formulated as a model-based control problem, with the control architecture illustrated in Fig. 6f. The tactile array measurements were processed through an orientation estimation module (detailed in “Method” and Supplementary Algorithms) that leverages contact strength distribution and contact area data to extract and fit a linear feature representing the object’s in-hand pose. The estimated orientation σest was then fed into a closed-loop control system, where the error between the desired orientation σdes and the current estimate was computed. After filtering and saturation, when this error fell below a predefined threshold, the third finger motion was terminated. Throughout the reorientation maneuver, the two grasping fingers maintained fixed positions to preserve stable object containment.

Experimental validation employed an ArUco marker affixed to the cylindrical prism to provide ground-truth (GT) orientation measurements, with the angular pose error used as the evaluation metric. Three target angles were evaluated: σdes = 10°, 25°, and 35°. The in-hand reorientation results, presented in Fig. 6h, demonstrate achieved angular errors of 0.0201 ± 0.0106 rad, 0.0417 ± 0.0158 rad, and 0.0457 ± 0.0196 rad (mean ± standard deviation, n = 10 trials), respectively.

We further conducted additional experiments demonstrating how an active tactile palm enables unique manipulation capabilities (Supplementary Movie 7). As illustrated in Fig. 6i, the gripper can reconfigure its finger joints to allow the palm to actively sense object features, particularly for objects with similar visual appearances that are difficult to distinguish using vision alone. In this application, three real strawberries and one artificial strawberry were placed on the table. Initially, the gripper reconfigures by extending the first joints of all fingers, enabling closer palm contact with each candidate object. The active palm employs the same tactile sensing methodology described in earlier sections, acquiring high-resolution surface geometry information without causing damage to delicate objects. The gripper system moves to the each candidate and repeats the active sensing process until the palm detects the artificial strawberry (T2), characterized by its rigid structure and distinct surface features (T3). Upon successful identification, the gripper transitions to a parallel pinch configuration (T4), utilizing the fingertip tactile arrays to execute secure grasping. Finally, the robotic manipulator lifts the selected object to complete the picking task (T5). This approach offers significant advantages over conventional arm-based manipulation strategies. The active palm approach through in-hand manipulation demonstrates potential for improved efficiency and enhanced safety through localized tactile exploration, reducing the mechanical demands on the primary manipulator. In this task, classification success rate is used as the evaluation metric, and the system achieved a 100% accuracy in identifying the artificial strawberry across 20 classifications.

Syringe actuation represents another compelling demonstration of the active tactile palm’s capability, as illustrated in Fig. 6j. The experimental sequence begins with the gripper securing the syringe body using a parallel pinch configuration while positioning the syringe plunger in contact with the palm surface. By executing a coordinated z-translation primitive, the palm advances the plunger while the fingers maintain a stable grip on the syringe barrel, effectively ejecting the contents through controlled linear motion. Supplementary Fig. 11 presents an additional challenging manipulation scenario: opening a child-resistant bottle cap, which requires the cap to be pressed downward before unscrewing through coordinated finger-palm interaction (corresponding to the motivational example in Fig. 1). In this task, task completion success rate is adopted as the evaluation metric, and the syringe actuation was completed with a 100% success rate across all 10 trials.

To further demonstrate the functionality of the active tactile palm in side-grasp scenarios, Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Fig. 13 present two representative experiments: dynamic fast lifting of an unbalanced object and precision peg-in-hole insertion. In the lifting task, the palm primarily enhances grasp stability during rapid motions, whereas in the peg-in-hole task, it is actively used for local feature (hole) localization and pose estimation. Together, these tasks exemplify the gripper’s ability to execute complex, multi-stage manipulation behaviors that are challenging for conventional grippers. They highlight capabilities that extend beyond the grasping and manipulation paradigms discussed in previous sections. In particular, the coordinated actuation between the fingers and the active palm enables the system to apply simultaneous multi-directional forces and motions, underscoring the unique design advantages of integrating an actively controlled tactile palm with dexterous finger manipulation.

Discussion

In summary, the proposed gripper demonstrates that a compact design with only seven degrees of freedom is capable of achieving robust grasping of diverse objects, fine-grained perception, and dexterous in-hand manipulation through effective coordination between the fingers and the active tactile palm. This result highlights that high manipulation performance does not necessarily require high-DOF designs, but can also be realized through finger-palm synergy. Furthermore, the integration of multi-sensing enables the gripper to extract rich contact information, providing both stability in grasping fragile objects and adaptability in more complex manipulation scenarios.

One of the most compelling findings of our research is the demonstrated effectiveness of the active tactile palm. Specifically, under low-DOF constraints, the actuated palm not only exhibits potential for enhancing dexterous manipulation but also provides perceptual capabilities through tactile feedback. By integrating comprehensive tactile feedback with highly flexible joint functionality, the active tactile palm enables more complex manipulations that approach the dexterity of human hands, accomplishing tasks that other tactile grippers lacking such design cannot achieve.

From a hardware perspective, the design is compact and modular, with all components fabricated via 3D printing and tactile sensing implemented using open-source or commercially available sensors. Compared to state-of-the-art high-DOF tactile hands that require sophisticated design and complex assembly processes3,4,24,57, our three-finger-plus-palm structure accomplishes a range of complex tasks through relatively simple palm-finger coordination. In contrast to conventional low-DOF two-finger tactile grippers5,9,12,13,19,41, the proposed design delivers substantially greater manipulation capability, particularly for in-hand manipulation tasks. Compared to high-DOF robotic hands with a larger number of actuated fingers, for common contact-driven tasks such as grasping that do not require high kinematic redundancy, the proposed gripper can be effectively operated using a low-DOF design without incurring a speed disadvantage. Although robotic hands with more independently actuated fingers may achieve fine in-hand adjustments or multi-contact manipulations more quickly, this trade-off does not diminish the versatility of the proposed gripper.

Nevertheless, the proposed gripper faces certain limitations in manipulating very small and flat objects. Additionally, the use of commercial GelSight sensor as the tactile palm constrains the supporting surface area, thereby limiting in-hand manipulation performance for objects requiring extensive palm contact (e.g., wide objects). This limited surface area also leads to center-of-mass instability, which further complicates manipulation control. Moreover, the current finger geometry imposes additional constraints during in-hand manipulation. The relatively large finger width can cause contact points to shift along the finger pads during rotation, reducing contact stability and limiting the maximum achievable rotation in a single manipulation step. In addition, the finger length may be insufficient for tall objects, leading to inadequate contact support and a higher effective center of mass, which further increases the likelihood of slip or instability during contact-rich manipulation. Potential improvements include incorporating soft fingernail extensions into the Fin Ray structure9 to better accommodate these challenging objects, as well as developing larger tactile sensors or implementing multi-level palm platforms with adjustable height and diameter35.

Beyond hardware design improvements, learning-based manipulation methods can be developed and tested in unstructured environments involving irregularly shaped objects and dynamic disturbances. Benefiting from our gripper’s multi-sensing capabilities, which demonstrate outstanding contact-rich feature extraction compared to other grippers that only possess tactile sensing modality on fingertips with proprioception, we envision leveraging the active tactile palm through policy learning methods to accomplish more complex manipulation tasks in the future.

Methods

Gripper fabrication

All rigid components of the proposed gripper, including the base, intermediate support, and top palm, were fabricated by 3D printing (X1C, Bambu Lab) using Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) material. Three Dynamixel XC330-M288-T servo motors were mounted around the center of the gripper base at 120° intervals (with their output shafts oriented outward), providing radial-ulnar deviation motion for each finger. A linear actuator (PQ12-R, Actuonix) was installed in a central slot of the base to drive the active palm. The second rotational joint of each finger, responsible for flexion-extension motion, was actuated by a Dynamixel XM430-W350-T servo motor. One end of the joint was coupled through a hinge frame and secured with a needle roller thrust bearing (5909K14, NSK) to the output of the first joint using a screw bushing, while the opposite end was supported by an idle bearing to provide additional mechanical stability for finger mounting. Each finger’s second joint was directly fastened to a 3D-printed TPU finger (Ultimaker TPU 95A, 100% infill).

The compliant Fin Ray structure of the fingers was modeled using the static structural module of ANSYS Workbench (ANSYS Inc.) with the finite element method (FEM). Material properties for TPU were set according to datasheet specifications: Young’s modulus of 26 MPa, Poisson’s ratio of 0.45, yield stress of 8.6 MPa, and density of 1.22 g/cm3. The Fin Ray design was adapted from UMI finger58 and modified to meet the requirements of our gripper. Specifically, the finger length was constrained by the palm: when the palm was fully extended and the fingers were closed, the remaining gap allowed clearance for at most a 5 mm-diameter sphere, ensuring palm tactile feedback for fruits such as strawberries. The finger thickness was set to 25 mm to accommodate the tactile array sensor. The two primary design parameters affecting the compliance of the Fin Ray structure were the number and thickness of the rays. Their mechanical effects were systematically evaluated using FEM simulations, and the results are presented in Supplementary Fig. 14. To ensure precise tactile signals without artifacts from sensor bending, the first design criterion limited fingertip displacement under a 10 N load to less than 5 mm, which is particularly important for delicate objects such as strawberries that tolerate a maximum grasping force of only 6 N59. In addition, considering fingertip width, a combined geometry-stress criterion was applied to prevent excessive bending and structural interference: a clearance constraint was imposed to maintain structural integrity, and a stress threshold of 3 MPa was enforced at the estimated maximum finger force of 40 N, corresponding to 35% of the material yield stress (8.6 MPa). This ensures both mechanical safety and long-term durability, consistent with design practices in soft robotic systems60. Based on this analysis, a configuration with seven rays and 2 mm thickness was selected as the optimal balance between compliance and strength. Each fingertip was equipped with a tactile array sensor bonded to the Fin Ray surface using clear adhesive transfer tape (467MP, 3M). The tactile array sensor adopts a triple-layer design, consisting of a piezoresistive layer (Velostat) sandwiched between two orthogonally aligned layers of conductive yarn that serve as electrodes, with polyimide sheets applied as protective outer layers16. The resistance of the piezoresistive layer varies with applied pressure, enabling each sensing point to transduce mechanical stimuli into electrical signals. To enhance surface contact and friction during grasping, a high-friction gripping material (TB641, 3M) was applied as the outermost coating. All remaining components were assembled using conventional fasteners.

Tactile-reactive finger controller

We adopted a threshold-based stopping condition that leverages the tactile arrays at the fingertips as grasping force feedback, as shown in Fig. 6f. This strategy was applied in the grasping capability benchmarking, fruit-picking, and multi-sensing perception and classification experiments. For the first two tasks, the finger motions were set to be synchronous, where the finger actuator positions and stopping times were identical. The termination condition qf is defined as:

where ΔCf denotes the change in the number of non-zero contact pixels, and ΣSf represents the cumulative signal strength obtained by summing all 16 × 8 taxels of the tactile array. The weighting vector \([\begin{array}{cc}\alpha & (1-\alpha )\end{array}]\) linearly projects these two features into a scalar, with α ∈ [0, 1] balancing the contributions of contact area and signal magnitude. In the controller, finger f continues flexion while qf < Tth, where Tth is a hand-tuned threshold for closed-loop grasp termination. On the other hand, during the multi-sensing perception and classification experiment, the thresholding method was applied independently to each finger with a smaller threshold in order to collect high-quality data and ensure that every tactile array contained features. Note that both α and Tth are task-specific. For example, in picking fragile fruit, the weight assigned to cumulative signal strength is dominant, and Tth is set much smaller than in grasping YCB rigid objects.

Tactile-reactive palm controller

The contact area in all tasks was obtained using a fixed-depth threshold followed by image morphological filtering. For threshold-based tasks, such as sensing the surface geometry of grasped fruit after finger closure, the palm was driven by interpolated linear actuator motion and stopped once the measured contact area exceeded the predefined threshold.

For dynamic tasks, the control feedback is derived exclusively from the contact area measured by the palm’s GelSight sensor, as shown in Fig. 6b. A strong linear correlation between contact area and palm displacement was verified even in single-object contacts against a fixed surface (Fig. 6c). Hence, the tactile-MPC model remains consistent with the formulation used for parallel DOF control in refs. 9,56. The system dynamics are defined as:

where c, p, v, and a represent the contact area, position, velocity, and acceleration of the palm, respectively. Kc denotes the scalar factor in the linear assumption. The cost function regulates the real-time contact area to remain stable, allowing the active palm to dynamically adjust and provide consistent support. Defining a feedback state vector \({{\bf{y}}}_{n}={[\begin{array}{cc}{c}_{n} & {v}_{n}\end{array}]}^{T}\), and let N denote the prediction horizon. The cost function is defined as:

where \({\bf{Q}}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{Q}_{c} & 0\\ 0 & {Q}_{v}\end{array}\right]\) is the weight matrix, \({{\bf{e}}}_{n}={{\bf{y}}}_{n}-\left[\begin{array}{l}{c}_{\mathrm{desired}}\\ 0\end{array}\right]\) is the error vector, and \({{\bf{a}}}_{n}={[{a}_{n},{a}_{n+1},\ldots ,{a}_{n+N-1}]}^{T}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) is the control input sequence.

Here, P is a scalar that amplifies the terminal cost to accelerate convergence. The controller aims to regulate the contact area to the desired value cdesired while minimizing residual motion, with vn → 0. The weights Qc, Qv, and Qa determine the relative importance of contact-area tracking, velocity damping, and control effort.

The optimal control sequence is obtained by solving the following constrained optimization problem:

subject to the system dynamics in Equation (4) and bounds on pn, vn, and an. In the light bulb installation experiment, the desired contact area was set to 8000, which provided sufficient support force while avoiding excessive friction that would hinder in-hand manipulation.

Experimental setups for multi-sensing fusion

We collected 120 samples per object for training the multi-sensing perception network. For each object, 96 samples (80%) were randomly selected for training and 24 samples (20%) for testing. During data collection, each finger was individually actuated to obtain clear tactile array signals.

The proposed architecture comprises three sensing-specific encoders. Visual inputs are different images, obtained by subtracting a base-clear image reference, resized to 224 × 224, and processed by a pretrained ResNet-18 encoder, yielding 512-dimensional embeddings. Tactile arrays from all three fingers are concatenated, normalized, and encoded using a three-layer MLP, producing 64-dimensional features. Proprioceptive joint states are normalized and incorporated directly without additional encoding. Cross-attention fusion first projects all sensing features into a unified 128-dimensional space. Each modality then serves as a query that attends to the other two modalities as key-value pairs, enabling adaptive information fusion. The attention outputs are concatenated without intermediate learning and fused via a learnable linear projection, followed by residual feature enhancement using a two-layer MLP. For fair comparison with bi-modal variants, identical architectural configurations were maintained across all fusion strategies, differing only in the input modality combinations. Finally, classification is performed by a three-layer MLP. The network was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 32, cross-entropy loss, a StepLR scheduler, and 50 training epochs.

Tactile array processing for orientation estimation

The orientation estimation module operates on a normalized tactile contact map I ∈ [0, 1]16 × 8 and outputs an angle θ relative to the array axes, as presented in Supplementary Algorithms. We first form a binary support \(B={\mathbb{1}}[I > {t}_{b}]\) with threshold tb ∈ (0, 1) and extract connected components \({\mathcal{C}}=\{{C}_{k}\}\). Components with insufficient support are filtered, and the dominant contact island is selected via a size-intensity score \(s(C)=| C| \cdot \mathop{\max }\limits_{p\in C}I(p)\), yielding \({C}^{* }=\arg \mathop{\max }\limits_{C\in {\mathcal{C}}}s(C)\). Let P = {(x, y) ∈ C*} be the pixel coordinates (array map frame), and require \(| P| \ge {N}_{\min }\) to ensure stability. The contact orientation is estimated by fitting a line to P using total least squares method: compute the sample mean \(\overline{{\bf{p}}}\) and covariance matrix Σ; the orientation is obtained by computing the dominant axis of the contact points. This axis is given by the principal eigenvector v = (vx, vy) of Σ, and the orientation angle is defined as the azimuth of this eigenvector in the two-dimensional plane, quantified relative to the x-axis in a counterclockwise direction.

Data availability

Data availability: All data supporting the findings of this study are available in this manuscript and its Supplementary Information and by request from the corresponding author.Code availability: The code for the kinematic model, tactile-reactive controllers, orientation estimation module, and cross-attention fusion can be found at: https://github.com/YuHoChau/7-DOF-Tactile-Gripper.

Code availability

The code for the kinematic model, tactile-reactive controllers, orientation estimation module, and cross-attention fusion can be found at: https://github.com/YuHoChau/7-DOF-Tactile-Gripper.

References

Navarro, S. E. et al. Proximity perception in human-centered robotics: a survey on sensing systems and applications. IEEE Trans. Robot. 38, 1599–1620 (2021).

Billard, A. & Kragic, D. Trends and challenges in robot manipulation. Science 364, eaat8414 (2019).

Shaw, K., Agarwal, A. & Pathak, D. Leap hand: low-cost, efficient, and anthropomorphic hand for robot learning. Robot. Sci. Syst. (RSS) (2023).

Wan, Z. et al. Rapid hand: A robust, affordable, perception-integrated, dexterous manipulation platform for generalist robot autonomy. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.07490 (2025).

Wilson, A., Wang, S., Romero, B. & Adelson, E. Design of a fully actuated robotic hand with multiple gelsight tactile sensors. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2002.02474 (2020).

Kim, Y.-J., Song, H. & Maeng, C.-Y. Blt gripper: An adaptive gripper with active transition capability between precise pinch and compliant grasp. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 5518–5525 (2020).

Ruotolo, W., Brouwer, D. & Cutkosky, M. R. From grasping to manipulation with gecko-inspired adhesives on a multifinger gripper. Sci. Robot. 6, eabi9773 (2021).

Chappell, D., Bello, F., Kormushev, P. & Rojas, N. The hydra hand: a mode-switching underactuated gripper with precision and power grasping modes. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 8, 7599–7606 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Zhou, P., Wang, S. & She, Y. In-hand singulation, scooping, and cable untangling with a 5-dof tactile-reactive gripper. Adv. Robot. Res. 202500020 (2025).

Do, W. K., Aumann, B., Chungyoun, C. & Kennedy, M. Inter-finger small object manipulation with densetact optical tactile sensor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 9, 515–522 (2024).

Jiang, J., Zhang, X., Gomes, D. F., Do, T.-T. & Luo, S. Rotipbot: robotic handling of thin and flexible objects using rotatable tactile sensors. IEEE Trans. Robot. 41, 3684–3702 (2025).

She, Y. et al. Cable manipulation with a tactile-reactive gripper. Int. J. Robot. Res. 40, 1385–1401 (2021).

Yuan, S. et al. Tactile-reactive roller grasper. IEEE Trans. Robot. 41, 1938–1955 (2025).

Cong, Q., Fan, W. & Zhang, D. Tacfr-gripper: a reconfigurable fin-ray-based gripper with tactile skin for in-hand manipulation. Actuators, 13, 521 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Intrinsic contact sensing and object perception of an adaptive fin-ray gripper integrating compact deflection sensors. IEEE Trans. Robot. 39, 4482–4499 (2023).

Huang, B., Wang, Y., Yang, X., Luo, Y. & Li, Y. 3d vitac: learning fine-grained manipulation with visuo-tactile sensing. In Proceedings of Robotics: Conference on Robot Learning(CoRL) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.24091 (2024).

Yuan, W., Dong, S. & Adelson, E. H. Gelsight: high-resolution robot tactile sensors for estimating geometry and force. Sensors 17 https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/17/12/2762 (2017).

Romero, B., Veiga, F. & Adelson, E. Soft, round, high-resolution tactile fingertip sensors for dexterous robotic manipulation. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 4796–4802 (IEEE, 2020).

She, Y., Liu, S. Q., Yu, P. & Adelson, E. Exoskeleton-covered soft finger with vision-based proprioception and tactile sensing. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 10075–10081 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhao, J. & Adelson, E. H. Gelsight svelte hand: a three-finger, two-dof, tactile-rich, low-cost robot hand for dexterous manipulation. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.10886 (2023).

Liu, S. Q. & Adelson, E. H. Gelsight fin ray: Incorporating tactile sensing into a soft compliant robotic gripper. In Proc. IEEE 5th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), 925–931 (IEEE, 2022).

Liu, S. Q., Yañez, L. Z. & Adelson, E. H. Gelsight endoflex: A soft endoskeleton hand with continuous high-resolution tactile sensing. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Lu, Z., Guo, H., Zhang, W. & Yu, H. Gtac-gripper: A reconfigurable under-actuated four-fingered robotic gripper with tactile sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 7232–7239 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Embedding high-resolution touch across robotic hands enables adaptive human-like grasping. Nat. Mach. Intell. 7, 889–900 (2025).

Lu, Z., Gao, X. & Yu, H. Gtac: A biomimetic tactile sensor with skin-like heterogeneous force feedback for robots. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 14491–14500 (2022).

Feix, T., Romero, J., Schmiedmayer, H.-B., Dollar, A. M. & Kragic, D. The grasp taxonomy of human grasp types. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 46, 66–77 (2015).

Bullock, I. M., Ma, R. R. & Dollar, A. M. A hand-centric classification of human and robot dexterous manipulation. IEEE Trans. Haptics 6, 129–144 (2012).

Pozzi, M., Malvezzi, M., Prattichizzo, D. & Salvietti, G. Actuated palms for soft robotic hands: review and perspectives. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 29, 902–912 (2023).

Skirven, T. M., Osterman, A. L., Fedorczyk, J. & Amadio, P. C. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity, 2-volume set E-book: Expert Consult (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011).

Feix, T., Romero, J., Schmiedmayer, H.-B., Dollar, A. M. & Kragic, D. The grasp taxonomy of human grasp types. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 46, 66–77 (2016).

Zhang, X., Yang, T., Zhang, D. & Lepora, N. F. Tacpalm: A soft gripper with a biomimetic optical tactile palm for stable precise grasping. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 38402–38416 (2024).

Zhang, N. et al. Soft robotic hand with tactile palm-finger coordination. Nat. Commun. 16, 2395 (2025).

Lei, Z. et al. A biomimetic tactile palm for robotic object manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 11500–11507 (2022).

Yoon, J. et al. A three-finger adaptive gripper with finger-embedded suction cups for enhanced object grasping mechanism. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 10, 915–922 (2024).

Teeple, C. B., Kim, G. R., Graule, M. A. & Wood, R. J. An active palm enhances dexterity of soft robotic in-hand manipulation. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 11790–11796 (IEEE, 2021).

Pagoli, A., Chapelle, F., Corrales, J. A., Mezouar, Y. & Lapusta, Y. A soft robotic gripper with an active palm and reconfigurable fingers for fully dexterous in-hand manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 6, 7706–7713 (2021).

Subramaniam, V., Jain, S., Agarwal, J. & Valdivia y Alvarado, P. Design and characterization of a hybrid soft gripper with active palm pose control. Int. J. Robot. Res. 39, 1668–1685 (2020).

GelSight Inc. Gelsight mini datasheet https://www.gelsight.com/wp-content/uploads/productsheet/Mini/GS_Mini_Product_Sheet_10.07.24.pdf (2024).

Yoshikawa, T. Manipulability of robotic mechanisms. Int. J. Robot. Res. 4, 3–9 (1985).

Vahrenkamp, N., Asfour, T., Metta, G., Sandini, G. & Dillmann, R. Manipulability analysis. In Proc. 12th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, 568–573 (IEEE, 2012).

Zhou, J., Huang, J., Dou, Q., Abbeel, P. & Liu, Y. A dexterous and compliant (dexco) hand based on soft hydraulic actuation for human-inspired fine in-hand manipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 41, 666–686 (2025).

Calli, B. et al. Benchmarking in manipulation research: Using the Yale-CMU-Berkeley object and model set. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 22, 36–52 (2015).

Calli, B. et al. The ycb object and model set: towards common benchmarks for manipulation research. In Proc. International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), 510–517 (IEEE, 2015).

Lu, Q., Baron, N., Clark, A. B. & Rojas, N. Systematic object-invariant in-hand manipulation via reconfigurable underactuation: Introducing the Ruth gripper. Int. J. Robot. Res. 40, 1402–1418 (2021).

Falco, J. et al. Benchmarking protocols for evaluating grasp strength, grasp cycle time, finger strength, and finger repeatability of robot end-effectors. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 644–651 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (IEEE, 2016).

Su, C., Wang, R., Cui, S. & Wang, S. Tit hand: A novel thumb-inspired tactile hand for dexterous fingertip manipulation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–13 (2024).

Luu, Q. K. et al. Manifeel: benchmarking and understanding visuotactile manipulation policy learning. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.18472 (2025).

Heng, L., Geng, H., Zhang, K., Abbeel, P. & Malik, J. Vitacformer: learning cross-modal representation for visuo-tactile dexterous manipulation. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.15953 (2025).

Xiong, Y., Ge, Y., Grimstad, L. & From, P. J. An autonomous strawberry-harvesting robot: design, development, integration, and field evaluation. J. Field Robot. 37, 202–224 (2020).

He, Z., Liu, Z., Zhou, Z., Karkee, M. & Zhang, Q. Improving picking efficiency under occlusion: design, development, and field evaluation of an innovative robotic strawberry harvester. Comput. Electron. Agric. 237, 110684 (2025).

Parsa, S., Debnath, B., Khan, M. A. & E, A. G. Modular autonomous strawberry picking robotic system. J. Field Robot. 41, 2226–2246 (2024).

Yuan, W., Zhu, C., Owens, A., Srinivasan, M. A. & Adelson, E. H. Shape-independent hardness estimation using deep learning and a gelsight tactile sensor. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 951–958 (IEEE, 2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Deep learning-based postharvest strawberry bruise detection under uv and incandescent light. Comput. Electron. Agric. 202, 107389 (2022).

Lee, Y., Lee, J., Jung, D., Park, D. I. & Kim, U. Index gripper: Industrial dexterous robotic gripper capable of all-orientational object manipulation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 30, 3404–3414 (2025).

Xu, Z. & She, Y. Letac-mpc: Learning model predictive control for tactile-reactive grasping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 40, 4376–4395 (2024).

Su, C., Wang, R., Cui, S. & Wang, S. Tit hand: a novel thumb-inspired tactile hand for dexterous fingertip manipulation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–13 (2024).

Chi, C. et al. Universal manipulation interface: In-the-wild robot teaching without in-the-wild robots. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS) (2024).

Dimeas, F., Sako, D. V., Moulianitis, V. C. & Aspragathos, N. A. Design and fuzzy control of a robotic gripper for efficient strawberry harvesting. Robotica 33, 1085–1098 (2015).

Miron, G. & Plante, J.-S. Design principles for improved fatigue life of high-strain pneumatic artificial muscles. Soft Robot. 3, 177–185 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by USDA under award No. 2023-67021-39072, No. 2024-67021-42878; NSF under award No. 2322056, No. 2423068, and No. 2520136. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the USDA or NSF. We thank Sheeraz Athar, Zhixian Hu and Zijing Huang for the helpful discussions and feedback on the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and Y.S. proposed the research. Y.Z. developed the robot hardware, controller designs, implementations, and experiments. W.S.L., Y.G., and Y.S. provided advice on experiments. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.Z. and Y.S. are inventors on a patent application related to the technology described in this work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Lee, W.S., Gu, Y. et al. Tactile-reactive gripper with an active palm for dexterous manipulation. npj Robot 4, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-026-00079-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-026-00079-y