Abstract

Traditional approaches to maritime security focus on state and economic perspectives. We suggest that a more holistic approach to maritime security is needed that encompasses state, economic, human and environmental security to make maritime security more equitable, sustainable and responsive to contemporary social and environmental challenges. Adopting a normative human and eco-centric approach to maritime security, which revolves around the needs of coastal communities and the imperative of ocean sustainability, can be guided by four principles: participation and pluralism, autonomy and agency, equity and justice, and coherence and coordination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maritime security is an increasingly used concept and framing, notably described as a ‘buzzword’ that encompasses a range of approaches and definitions1,2,3. However, its traditional definitions lack sufficient consideration of contemporary issues, and of human and ecological security. Initially dominated by concerns of geopolitical tensions, economic control and safety at sea, academic understanding of maritime security has evolved to include a ‘matrix’ of approaches including the marine environment, economic development, national security and human security1,4. Yet despite broad scholarly engagement, practical applications of maritime security still largely adhere to traditional definitions linked to international relations and security perspectives, focusing on safety, economic security, borders and the role of the state5. Meanwhile, both the research and practice of maritime security have failed to adequately embed critical considerations of human security (ref. 6: 283). Similarly, there has been little engagement with ecological security, a concept which reframes the object of security in terms of ecosystems and shared vulnerabilities of human and non-human lives7.

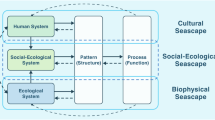

In this Perspective we argue for building on traditional approaches to maritime security by integrating often-overlooked social and ecological dimensions. We begin in the next section by exposing the limitations of current approaches that centre state and economic security, and delving into contemporary drivers of change that demand a broader perspective. We then present four guiding principles – (i) participation and plurality; (ii) autonomy and agency, (iii) equity and justice, and (iv) coherence and coordination – that should underpin the new conceptualisation of maritime security, drawing on examples from around the world. Finally, we conclude with a call to action, urging researchers, policymakers and practitioners alike to integrate new dimensions and narratives of maritime security into work on sustainable and socially-just futures. The holistic approach outlined in this paper offers opportunities to bridge the gap between traditional (top-down) state-centric and economic views of maritime security, the urgent needs of (bottom-up) coastal communities, and (systems level) promotion of ocean sustainability (Fig. 1). By doing so, this paper provides a more holistic and inclusive framework for addressing maritime security, focusing on addressing the voices and concerns of vulnerable and marginalised coastal populations while also accounting for the rapidly changing, multifaceted risks to these populations and ecosystems.

Security discourses can be characterised in terms of whose security is under consideration7, and what is valued as worthy of protection. Here we draw on broader approaches from maritime security scholarship1 and the marine social sciences37 to advocate for maritime security to be understood more holistically - not only in terms of security for nation-states and the economy, but also for humans and the natural environment. Figure provided by Stacey McCormack, Visual Knowledge Pty. Ltd.

Shortcomings in the current approach to maritime security

In writing this Perspective we acknowledge that, in 2025, the traditional approach to maritime security remains highly relevant. For instance, piracy in the Gulf of Aden continues to pose a significant threat to international shipping lanes, critical infrastructure in the sea is being sabotaged in Europe, while intensifying state conflicts in the South China Sea highlight persistent geopolitical contestations over maritime boundaries and resources, to name just three. These examples underscore the political relevance of robust maritime security measures to safeguard national interests, reducing risks to economic investments, and ensuring the safety of maritime navigation. States – individually and collectively – remain key agents in advancing security, where competing needs as well as emerging issues are adjudicated, including through military conflict.

However, state capacities to address complex maritime security issues such as deep-sea mining, migration across the Mediterranean sea into Europe, or seafloor claims in the Arctic, are also increasingly under strain or are outpaced by rapidly evolving economic and environmental changes, many of which are transboundary or global in nature. The livelihoods of those living on the coasts, such as small-scale fishers8, now face unprecedented pressures from rapidly emerging, competing economic activities including tourism, reclamation, mariculture, shipping and mining9,10,11. Many of these economic changes along the coastlines are increasingly associated with various forms of ‘ocean grabbing’, ‘coastal squeeze’, and other injustices which compromise livelihood security and are distributed differentially through class, ethnicity, gender and colonial histories9,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Other social and economic developments present emerging challenges and opportunities for maritime security too. For example, forms of ocean governance that combine different forms of authority and shift the locus of power and decision making away from the state alone18,19, advancements in surveillance technologies including drones and satellites20,21, and greater recognition of Indigenous and local knowledge in policy8 all have implications for maritime security; including monitoring and enforcement of fisheries. There is now also increasing attention to social issues that can impact maritime security, such as labour standards in ocean sectors22,23. And from an ecological perspective, environmental degradation caused by climate change and marine heatwaves24, overfishing, mining, pollution and other anthropogenic factors are synergistically combining to effect profound changes on the marine environment25,26.

Ultimately, such economic and environmental changes directly threaten human, food and livelihood security. For small island developing states, climate change arguably poses the ultimate security challenge to their continued viability27. The impacts of the declines of marine ecosystems and fisheries more broadly pose huge challenges to the security of coastal livelihoods, particularly in tropical regions28. Small-scale fisheries account for approximately 90% of total employment in fisheries, and about 492 million people are partially dependent on small-scale fisheries for employment or subsistence8, while aquatic animal foods globally supplied 15 percent of animal proteins and 6 percent of all proteins in 2021, accounting for a greater share in low-income countries than high-income countries29. Globally, the ocean economy is estimated to have a GDP of up to $US 6 trillion30, but estimated losses from mismanagement of $US 1 trillion31.

Viewed through a human security lens, these drivers of change all act to shape and influence the more conventionally understood aspects of maritime security – when the livelihoods of ocean-dependent people become increasingly at risk, this can lead to social or political unrest, or economic instability. Traditional approaches, however, tend to account for these drivers of change through a more limited frame of state and economic security, with insufficient attention to human and environmental dimensions. On the contrary, these approaches can regard oceans and seas as a basis for reproducing state and financial security whether for sovereign territory or as resources for economic exploitation [see refs. 32,33]. Consequently, the dominance of traditional, state-centric approaches to maritime security can implicitly and explicitly marginalise the views of minority groups, and obscure the significance of environmental sustainability. As such we are also witnessing state behaviours, particularly geopolitical competition and violent conflicts over contested waters, themselves causing further human and environmental insecurities. As an alternative, Pacific scholars have long advanced eco-centric values toward, and custodial and embedded relationships with the Pacific Ocean34, which include resisting its past and present militarisation35.

A combination of a) changing environmental and social-economic conditions and b) entrenched interests that uphold a traditional approach to maritime security that prioritises state and economic interests are threatening both environmental and human security in the oceans. Ultimately, this will have negative implications for all forms of maritime security. There is, therefore, a need to rethink the more traditional approaches to maritime security. An expanded approach to maritime security should effectively account for who and for what reasons maritime security is framed, and explicitly focus on the human and ecological dimensions of maritime security.

Four principles for rethinking maritime security

To address the need for a more holistic and more normative conceptualization of maritime security, this Perspective develops a set of four principles: (1) participation and plurality, (2) autonomy and agency, (3) equity and justice, and (4) coherence and coordination (Fig. 2). While we draw broadly on a human security approach that challenges the primacy of state institutions and ‘high politics’36, the development of these principles is also informed by interdisciplinary insights from the critical marine social sciences37 about ocean governance. Crosscutting all of these principles is an explicit normative focus that aims to rebalance traditional approaches to maritime security by prioritising human and environmental dimensions. While concrete application of these four principles will vary according to context, illustrative examples provide guidance (Boxes 1–4). Specifically, we explore participation and pluralism through a case study of networked community-based institutions in Box 1, autonomy and agency through a case study of maritime cultural heritage in Box 2, equity and justice through a case study of the gender transformative approach in Box 3, and coherence and coordination through a case study of the High Seas Treaty in Box 4.

Participation and pluralism

An initial step in an expanded perspective of maritime security is to explicitly consider questions of context and recognize that any approach to maritime security must account for the diverse interests and needs for which maritime security can be deployed38. Different types of states have different approaches to maritime security. For example, ‘great powers’ such as the USA and China prioritize strategic dominance and control over key maritime routes, while small island developing states often focus on protecting their vulnerable maritime environments and the resources therein for economic development amid the effects of climate change. Middle powers, such as Australia, seek to balance these interests with regional stability, economic considerations and environmental sustainability. All emphasise different types of maritime security that are relevant to their national interests and capacities, and reflect their relative vulnerabilities to different risks. Global oceans governance regimes, such as for the high seas, have important roles to play in facilitating the participation of all states to govern these issues39.

Within states, the interest of large companies involved in shipping and transport often differ significantly from other sectors such as small-scale fishers or small-scale tourism operators, who are more likely focused on community-level livelihoods (e.g., Box 1). These differing interests can subsequently be supported or privileged by states differentially, granting established economic actors increased power. Additionally, within states, cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping how maritime security is perceived and implemented. For example, Indigenous coastal communities may prioritize the protection of marine estates and cultural heritage sites, while urban populations might focus on coastal housing and property values changing in response to climate change, the economic benefits of maritime trade or having seafood available in shops. At the level of governance, numerous environmental governance theories offer diverse means of participation, institutional configurations and decision-making structures, but are not often engaged with in coastal/ocean contexts40. And beyond human dimensions alone, diverse marine ecologies and animals have distinct interests and needs for protection41, which differ from land-based considerations given the uniqueness of ocean contexts42.

Recognizing this plurality requires a holistic understanding of the various dimensions of maritime security – state, economic, environmental and human security – and effectively enabling participation so that these plural perspectives are made visible, represented in decision-making fora, and collectively validated.

Autonomy and agency

Agency is about ‘people’s ability to choose in ways that align with their values and goals, and to act to realise their goals’43. For maritime security policies that are sensitive to social and economic considerations to be effective, they must adequately consider the autonomy and agency of diverse coastal communities and nations. Agency is crucial in multiple domains (e.g., Box 2). From one standpoint, agency forms a key component of procedural justice through participation in governance. In terms of pragmatic or utilitarian dimensions, greater agency for traditionally less powerful or marginalised maritime and coastal sectors can also confer legitimacy for governance. Ultimately, it can facilitate innovation and generate stronger linkages between policies and needs, knowledge, priorities and perspectives of those closest to the ground, based on local conditions44,45. Beyond procedural and utilitarian considerations alone, greater agency for coastal communities also means recognising the diverse forms of vulnerability that impact people’s lives, and which can be addressed through, for example, human-rights based approaches46.

Recognition of autonomy is about acknowledging rights and sovereignty among diverse groups and nations. This means, for example, valuing Indigenous knowledge and worldviews which is indispensable to reframing the referent object, goals and means of security47. When groups such as small-scale fishers are provided with autonomy through tenure and management rights, they are able to monitor and enforce their own rules and territorial boundaries in line with their own preferences, and in doing so, improve their own environmental and human security48,49,50. When groups of nations are able to express and assert their vision in regional ocean governance processes, this can produce outcomes that better reflect local realities and meet local needs51,52. As we are seeing in various areas of global governance, incorporating diverse perspectives enhances the durability of peace53 and can lead to more ambitious political reform goals54. It provides space for voices calling for re-orienting prevailing approaches to oceans and seas away from domination, extraction and conquest.

Equity and justice

This principle emphasizes the need to ensure that maritime security policies and practices do not disproportionately benefit certain groups while marginalizing others17. Equity broadly calls for fair distribution of resources, opportunities and mitigation of risks associated with maritime activities, while justice calls for explicit recognition of and actions relating to structurally vulnerable groups55,56.

While maritime security is typically understood as a relatively unproblematic normative commitment and end-state, traditional approaches to maritime security can also generate and intensify negative consequences for marginalised sectors, actors, and the environment57. The securitisation of small-scale fisheries through increased surveillance and regulation in areas near ports can intensify existing inequities58, while a focus on border protection can marginalise groups with traditional patterns of cross-border fishing, movement and trade59. Increasing marine protected areas to secure ecosystems and implement nature-based solutions for coastal climate adaptation can also exclude people, ignore tenure rights and threaten livelihoods60. While realist approaches to maritime security typically view power relations as interactions between states61, greater consideration of equity and justice can inform more nuanced approaches to power that better address the maritime security needs of marginalised groups within states, such as small-scale fishers, women (e.g., Box 3), Indigenous maritime groups, migrants and children62. Justice is central because these groups face either discrimination from or disenfranchisement by states, and are deprived of economic opportunities to directly shape their living conditions, yet are also most affected by the adverse consequences of political and economic processes from which they are structurally excluded. Access to justice can be an important means of redress and resolving conflicts when human security is undermined63.

While only one among many different justice frameworks, the emerging agenda of ‘blue justice’ synthesises procedural, distributional and recognitional justice dimensions in relation to the oceans10,13,64. Many of the advocated policy recommendations are highly relevant to the field of maritime security13. For example, explicit considerations of equity among different groups, and better representation of all stakeholders in decision-making platforms are broad features that can be meaningfully applied across maritime security policies typically associated with top-down approaches. More specifically, taking into account pre-existing rights and tenure over coastal and ocean spaces through policy instruments such as the Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines is a prerequisite for ensuring that maritime security strategies reduce risks and vulnerabilities of those connected most closely to ocean spaces57,65.

Coherence and coordination

This principle emphasizes the need for integrated and harmonized policies and actions across different scales, sectors and levels of governance. Policy coherence66 is a vision and no panacea on its own67, but coordination can help reduce risks, reconcile differences and navigate tensions and conflicts. Greater attention to coherence and coordination is critical for ensuring that the interaction effects of multiple, different policy interventions do not counteract each other, or generate negative trade-offs at the expense of already vulnerable groups68.

While in many cases the concept of maritime security implies an inherent disconnect between states, there are many lessons from the governance of transboundary marine resources across states that can support more coordinated approaches (e.g., Box 4). Similarly, while maritime security often involves territorial disputes as in the South China Sea, marine resources play a significant role in shaping conflicts and cooperation in the ocean69. In this sense, policy coherence in the management of transboundary marine resources within and between states can contribute to creating stability in maritime space. For example, in addition to the fundamental role of international law70, regional institutions can play valuable roles that bridge between international and national interests71,72.

Fragmented, incoherent approaches to maritime security can also lead to conflict not only between states, but policy and implementation failures between and within them9,73,74, as well as marginalising considerations of social equity75. For example, when policies to protect marine resources in the name of enhanced maritime security fail to consider social and economic factors, this can generate significant negative social impacts76,77, which can then in turn undermine efficacy of ocean governance and conservation78.

Greater attention to coordination in maritime security policies would ultimately facilitate better recognition of and capacity to address the trade-offs involved. It would also highlight key dimensions of governance that are relevant for improved outcomes, in particular, transparency and accountability79,80.

Conclusion

This paper offers preliminary points of dialogue on how to enable a more holistic and human- and eco-centric approach to maritime security than current approaches. We emphasise four principles to serve as starting points to think about how to move beyond conceptions and practices of maritime security largely dominated by state and economic interests, and that respond to new and intensifying drivers of change. In contrast to a state lens, a global lens centres an ecological perspective and shared cross-border environmental challenges, and a local lens brings human security into focus.

These principles can serve as starting and reference points for dialogue and debate in concrete and context-specific strategy and policy arenas. Different actors including policymakers, researchers and other stakeholders will all have different ways in which the approach outlined in this Perspective can be progressed. In doing so, all actors can play a role to catalyse a more holistic approach to maritime security that can better address the increasingly urgent needs of diverse communities and environments in the maritime realm.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bueger, C. What is maritime security?. Mar. Policy 53, 159–164 (2015).

Germond, B. The geopolitical dimension of maritime security. Mar. Policy 54, 137–142 (2015).

Bruwer, C. Transnational organised crime at sea as a threat to the sustainable development goals: Taking direction from piracy and counter-piracy in the Western Indian Ocean. Afr. Secur. Rev. 28, 172–188 (2019).

Bueger, C. & Edmunds, T. Beyond seablindness: a new agenda for maritime security studies. Int. Aff. 93, 1293–1311 (2017).

Kismartini, K., Yusuf, I. M., Sabilla, K. R. & Roziqin, A. A bibliometric analysis of maritime security policy: Research trends and future agenda. Heliyon 10, e28988 (2024).

Amirell, S. E. Global maritime security studies: The rise of a geopolitical area of policy and research. Secur. J. 29, 276–289 (2016).

McDonald, M. Ecological Security: Climate Change and the Construction of Security (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

FAO, Duke University & WorldFish. Illuminating Hidden Harvests – The contributions of small-scale fisheries to sustainable development. (FAO, 2023).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat. Sustain. 2, 991–993 (2019).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Mar. Policy 125, 104387 (2021).

Fabinyi, M. et al. Coastal transitions: Small-scale fisheries, livelihoods, and maritime zone developments in Southeast Asia. J. Rural Stud. 91, 184–194 (2022).

Bavinck, M., Jentoft, S. & Scholtens, J. Fisheries as social struggle: a reinvigorated social science research agenda. Mar. Policy 94, 46–52 (2018).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Environmental (in) justice in the Anthropocene ocean. Mar. Policy 147, 105383 (2023).

Cohen, P. J. et al. Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 171 (2019).

Belton, B. et al. Farming fish in the sea will not nourish the world. Nat. Commun. 11, 5804 (2020).

Allison, E. H. et al. The human relationship with our ocean planet. In The Blue Compendium: From Knowledge to Action for a Sustainable Ocean Economy 393–443 (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Spalding, A. K. et al. Engaging the tropical majority to make ocean governance and science more equitable and effective. NPJ Ocean Sustain 2, 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-023-00015-9 (2023).

Vandergeest, P., Ponte, S. & Bush, S. Assembling sustainable territories: Space, subjects, objects, and expertise in seafood certification. Environ. Plan. A 47, 1907–1925 (2015).

Schlüter, A. et al. Broadening the perspective on ocean privatizations: an interdisciplinary social science enquiry. Ecol. Soc. 25, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11772-250320 (2020).

Toonen, H. M. & Bush, S. R. The digital frontiers of fisheries governance: fish attraction devices, drones and satellites. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 22, 125–137 (2020).

McCauley, D. J. et al. Improving Ocean Management Using Insights from Space. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 17 (2024).

Tickler et al. Modern slavery and the race to fish. Nat. Commun. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07118-9 (2018).

Vandergeest, P. & Marschke, M. Beyond slavery scandals: Explaining working conditions among fish workers in Taiwan and Thailand. Mar. Policy 132, 104685 (2021).

Ainsworth, T. D., Hurd, C. L., Gates, R. D. & Boyd, P. W. How do we overcome abrupt degradation of marine ecosystems and meet the challenge of heat waves and climate extremes?. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 343–354 (2020).

Nash, K. L. et al. Planetary boundaries for a blue planet. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1625–1634 (2017).

Jouffray, J. B., Blasiak, R., Norström, A. V., Österblom, H. & Nyström, M. The blue acceleration: the trajectory of human expansion into the ocean. One Earth 2, 43–54 (2020).

Thomas, A. et al. Climate change and small island developing states. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45, 1–27 (2020).

Lam, V. W. et al. Climate change, tropical fisheries and prospects for sustainable development. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 440–454 (2020).

FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action. (FAO, 2024).

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Trade and Environment Review 2023: Building a Sustainable and Resilient Ocean Economy Beyond 2030. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditcted2023d1_en.pdf (2023).

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Ocean Promise. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-06/UNDPOceanPromise_V2.pdf (2022).

Tickner, J. States and Markets: An Ecofeminist Perspective on International Political Economy. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 14, 59–59 (1993).

Jackman, A., Squire, R., Bruun, J. & Thornton, P. Unearthing feminist territories and terrains. Polit. Geogr. 102180, 1–12 (2020).

Hau’ofa, E. We are the Ocean: Selected Works (University of Hawaii Press, 2008).

Teiawa, T. bikinis and other s/pacific n/oceans. Contemp. Pac. 6, 87–109 (1994).

Newman, E. Human security. In Routledge Handbook of Peace, Security and Development 33–44 (Routledge, 2020).

Spalding, A. K. & McKinley, E. The state of marine social science: Yesterday, today, and into the future. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 17, 143–165 (2025).

Bradford, J. & Edwards, S. Evolving Stakeholder Roles in Southeast Asian Maritime Security: Workshop Report. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-Maritime-Security-Stakeholders-Workshop-Report.pdf (2022).

Lothian, S. L. International cooperation: the linchpin to the successful implementation of the BBNJ agreement. In The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Policy and Law 1–21 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024).

Partelow, S. et al. Environmental governance theories: a review and application to coastal systems. Ecol. Soc. 25, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12067-250419 (2020).

Swanson, H. A. Methods for multispecies anthropology: Thinking with salmon otoliths and scales. Soc. Anal. 61, 81–99 (2017).

Steinberg, P. & Peters, K. Wet ontologies, fluid spaces: Giving depth to volume through oceanic thinking. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 33, 247–264, https://doi.org/10.1068/d14148p (2015).

Manlosa, A. O., Albrecht, J. & Riechers, M. Social capital strengthens agency among fish farmers: Small scale aquaculture in Bulacan, Philippines. Front. Aquacult. 2, 1106416 (2023).

Westley, F. R. et al. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 18, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05072-180327 (2013).

Galappaththi, M., Armitage, D. & Collins, A. M. Women’s experiences in influencing and shaping small-scale fisheries governance. Fish Fish 23, 1099–1120 (2022).

Allison, E. H. et al. Rights-based fisheries governance: from fishing rights to human rights. Fish Fish 13, 14–29 (2012).

Ban, N. C. & Frid, A. Indigenous peoples’ rights and marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 87, 180–185 (2018).

Basurto, X. How locally designed access and use controls can prevent the tragedy of the commons in a Mexican small-scale fishing community. Soc. Nat. Resour. 18, 643–659 (2005).

Cinner, J. E. et al. Bright spots among the world’s coral reefs. Nature 535, 1–17 (2016).

Basurto, X. et al. Illuminating the multidimensional contributions of small-scale fisheries. Nature 637, 1–10 (2025).

Pratt, C. & Govan, H. Our sea of islands, our livelihoods, our Oceania—Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: A catalyst for implementation of ocean policy. http://www.academia.edu/download/30283728/000937_684.pdf (2010).

SPC. A new song for coastal fisheries—Pathways to change: The Noumea strategy. (Secretariat of the Pacific Community, 2015).

UN Women. Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace. https://wps.unwomen.org/ (2015).

Willis, R., Curato, N. & Smith, G. Deliberative democracy and the climate crisis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 13, e759 (2022).

Chu, E. K. & Cannon, C. E. Equity, inclusion, and justice as criteria for decision-making on climate adaptation in cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 51, 85–94 (2021).

Crosman, K. M. et al. Social equity is key to sustainable ocean governance. NPJ Ocean Sustain 1, 4 (2022).

Gill, D. et al. Triple Exposure: Reducing negative impacts of climate change, blue growth, and conservation on coastal communities. One Earth 6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.01.010 (2023).

Ayilu, R. K. Limits to blue economy: challenges to accessing fishing livelihoods in Ghana’s port communities. Marit. Stud. 22, 11 (2023).

Fabinyi, M. et al. Fisheries trade and social development in the Philippine-Malaysia maritime border zone. Dev. Policy Rev. 32, 715–732 (2014).

Sowman, M. & Sunde, J. Social impacts of marine protected areas in South Africa on coastal fishing communities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 157, 168–179 (2018).

Klein, N. Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Shepherd, L. & Hamilton, C. (eds). Gender Matters in Global Politics: A Feminist Introduction to International Relations (Routledge, 2023).

Ratner, B. D., Åsgård, B. & Allison, E. H. Fishing for justice: Human rights, development, and fisheries sector reform. Glob. Environ. Change 27, 120–130 (2014).

Blythe, J. L. et al. Blue justice: A review of emerging scholarship and resistance movements. Coast. Futures 1, e15 (2023).

Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Barragán-Paladines, M. J. & Franz, N. (Eds.). The Small-scale Fisheries Guidelines: Global Implementation (Springer, 2017).

Cejudo, G. M. & Michel, C. L. Addressing fragmented government action: Coordination, coherence, and integration. Policy Sci 50, 745–767 (2017).

Yunita, A. et al. The (anti-) politics of policy coherence for sustainable development in the Netherlands: Logic, method, effects. Geoforum 128, 92–102 (2022).

Nilsson, M. et al. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain. Sci. 13, 1489–1503 (2018).

Zhang, H. & Bateman, S. Fishing militia, the securitization of fishery and the South China Sea dispute. Contemp. Southeast Asia 39, 288–314 (2017).

Mossop, J. Maritime security and the law of the sea. In Routledge Handbook of Maritime Security 86–95 (Routledge, 2022).

Campbell, B. & Hanich, Q. Principles and practice for the equitable governance of transboundary natural resources: cross-cutting lessons for marine fisheries management. Marit. Stud. 14, 1–20 (2015).

Mahon, R. & Fanning, L. Regional ocean governance: Polycentric arrangements and their role in global ocean governance. Mar. Policy 107, 103590 (2019).

Fanning, L. & Mahon, R. Governance of the Global Ocean Commons: Hopelessly Fragmented or Fixable? Coast. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2020.1803563 (2020).

Voyer, M. et al. Assessing policy coherence and coordination in the sustainable development of a Blue Economy. A case study from Timor Leste. Ocean Coast. Manag. 192, 105187 (2020).

Brugere, C., Troell, M. & Eriksson, H. More than fish: Policy coherence and benefit sharing as necessary conditions for equitable aquaculture development. Mar. Policy 123, 104271 (2021).

De Santo, E. M. Militarized marine protected areas in overseas territories: Conserving biodiversity, geopolitical positioning, and securing resources in the 21st century. Ocean Coast. Manag. 184, 105006 (2020).

Na’puti, T. R. & Frain, S. C. Indigenous environmental perspectives: Challenging the oceanic security state. Secur. Dialogue 54, 115–136 (2023).

Partelow, S. et al. Five social science intervention areas for ocean sustainability initiatives. NPJ Ocean Sustain 2, 24 (2023).

Blasiak, R. et al. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Mar. Policy 107, 103508 (2019).

Barclay, K. M. et al. Social harvest control rules for sustainable fisheries. Fish Fish 24, 896–905 (2023).

Steenbergen, D. J. & Adhuri, D. S. I-LMMA’s ‘5-50-500’ Program: Scaling community-based fisheries management in eastern Indonesia. Mid-term review report. [unpublished], Indonesia Locally Managed Marine Area network: i-iv; 1-75 (2018).

Carlisle, K. & Gruby, R. L. Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons. Policy Stud. J. 47, 927–952 (2019).

Fortnam, M. et al. Polycentricity in practice: Marine governance transitions in Southeast Asia. Environ. Sci. Policy 137, 87–98 (2022).

Paramita, A. O. et al. Can the Indonesian Collective Action Norm of Gotong-Royong Be Strengthened with Economic Incentives? Comparing the Implementation of an Aquaculture Irrigation Policy Program. Int. J. Commons 17, 462–480 (2023).

Henderson, J. Oceans without history? Marine cultural heritage and the sustainable development agenda. Sustainability 11, 5080 (2019).

Schwerdtner Máñez, K. et al. The future of the oceans past: towards a global marine historical research initiative. PLoS One 9, e101466 (2014).

Strand, M., Rivers, N. & Snow, B. The complexity of evaluating, categorising and quantifying marine cultural heritage. Mar. Policy 148, 105449 (2023).

Breen, C. et al. Integrating cultural and natural heritage approaches to Marine Protected Areas in the MENA region. Mar. Policy 132, 104676 (2021).

Fowler, M. E. Aboriginal maritime landscapes in South Australia: The balance ground. (Routledge, 2019).

Harper, S. & Martin, A. Gender and the Ocean: Marine Resources and Spaces for All. In The Ocean and Us 309–319 (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Mangubhai, S., Barclay, K. M., Lawless, S. & Makhoul, N. Gender-based violence: Relevance for fisheries practitioners. Fish Fish 24, 582–594 (2023).

McDougall, C. et al. Toward structural change: Gender transformative approaches. In Advancing gender equality through agricultural and environmental research: Past, present, and future 365–401 https://hdl.handle.net/10568/116031 (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2021).

Sverdlik, A. Gender and intersectionality in action research. IIED, London. Available at https://www.iied.org/20036iied (2021).

Blasiak, R. & Claudet, J. Governance of the High Seas. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 49, 549–572 (2024).

Österblom, H. & Folke, C. Emergence of global adaptive governance for stewardship of regional marine resources. Ecol. Soc. 18, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05373-180204 (2013).

Levin, L. A., Amon, D. J. & Lily, H. Challenges to the sustainability of deep-seabed mining. Nat. Sustain. 3, 784–794 (2020).

Hornidge, A., Partelow, S. & Knopf, K. Knowing the Ocean: Epistemic Inequalities in Patterns of Science Collaboration. In Ocean Governance: Knowledge Systems, Policy Foundations and Thematic Analyses 25–45 (Springer, 2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center and the Australian Research Council (DP220101503) for funding support. SP is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 101164978) for the project SharedSeas. We thank Stacey McCormack, Visual Knowledge Pty. Ltd., for the creation of Figures 1 and 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F., C.C., K.B., N.J.B., E.C., H.N., S.P., A.Y.S., N.S., D.S., B.S., and M.T. wrote the main manuscript text, designed Figure 2 and reviewed the manuscript. NJB designed Figure 1. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabinyi, M., Cvitanovic, C., Barclay, K. et al. Rethinking maritime security from the bottom up: Four principles to broaden perspectives and centre humans and ecosystems. npj Ocean Sustain 4, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00130-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00130-9