Abstract

Are climate-resilient small-scale fisheries more resilient in general? Small-scale fisheries are increasingly exposed to a multitude of shocks that threaten their productivity and existence. Understanding whether resilience is specific to, or generalizable across, “domains” (e.g. environmental, market, social) can help design policy interventions to support small-scale fisheries. Here, we test whether fishing economic units that exhibit higher resistance to climate shocks are also more resistant to shocks from other domains. We analyzed long-term fisheries production data from 237 economic units that were subject to two recent major shocks: a period of frequent and intense marine heatwaves (2015-2016) and market disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022). In 86.1% of the cases (N = 204), economic units exhibited similar resistance for both shocks, and concordance was higher for fishing units with low catch diversity and a balanced market portfolio. Our work suggests that resilience may be generalizable across domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small-scale fisheries are integral components of most coastal social-ecological systems. They serve as an essential driver of local economies and food security, and provide livelihoods and sustenance to millions of people worldwide1,2. However, climate change, social unrest, and unforeseen global market disruptions –such as the COVID-19 pandemic– threaten small-scale fisheries and the important benefits they provide3,4,5. As climate change and other shocks continue to intensify and become more frequent, it is important that we understand the resilience of fishing communities to multiple pressures.

The resilience of a social-ecological system can be understood as the product of three components: resistance, recovery, and robustness6. Resistance refers to a system’s ability to absorb the impact of a shock without suffering substantial disruptions to its functionality. Recovery pertains to the speed and effectiveness with which the system returns to its pre-shock state. And robustness refers to the probability of a system retaining its identity after withstanding a shock6. Here, we examine the general ability of small-scale fishers, fishing cooperatives, and fishing companies (termed “economic units”) to resist climate and market shocks like marine heatwaves or market disruptions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively. Specifically, we focus on economic units’ ability to maintain a baseline level of revenue while resiting climate and market shocks.

Previous work has shown that marine heatwaves and the COVID-19 pandemic had large negative impacts on small-scale fisheries performance. For example, catch –and presumably revenues– decreased by up to 50% when small-scale fisheries in the Baja California Peninsula were exposed to an intense regime of marine heatwaves7. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented market shocks that affected all sectors of the seafood supply chain, including catch, processing, distribution, and sales, which resulted in large economic losses to fishers worldwide4,5,8,9,10. These shocks arose from different domains, but they also affected the fisheries through different pathways. Extreme marine heatwaves acted as a supply-side shock because fishers couldn’t harvest their target species due to mortality or temporary redistribution of marine taxa. On the other hand, the COVID-19 shock was a demand-side shock because trade flows were affected, which prevented fishers from selling their catch5,11.

Regardless of the source and pathway followed by each shock, an important observation has emerged: Not all fisheries were equally affected during these events. The reduction in catch during the marine heatwave regime was not homogeneous across economic units7 and, during the pandemic, some fishers swiftly adapted their distribution channels, changed target species, and engaged in other economic activities that allowed them to stay afloat11. The heterogeneity in impacts from and resistance to shocks observed across multiple systems begs the question: does resistance to climate shocks also coincide with a greater ability to resist market disruptions? In other words, is the “resistance” component of resilience generalizable across domains? We hypothesize that economic units that have demonstrated high resistance to climate extremes can also resist other perturbations such as market shocks, which would be indicative of generalizability in resilience.

To test our hypothesis, we focused on a region that has been exposed to at least two different types of shocks, and where the performance of its fisheries can be tracked before, during, and after each shock6. Many regions meet the first requirement because most small-scale fisheries have been exposed to multiple shocks (see refs. 12,13). However, the second requirement is harder to meet because small-scale fisheries are often data-limited systems. The Baja California Peninsula (Mexico; Fig. 1) meets both requirements because small-scale fisheries in the region were exposed to extreme climate and market shocks brought about by marine heatwaves7 and COVID-19 disruptions4,11, and there is a considerable availability of long-term and high resolution fisheries data.

We approach our central question about generalizability in resilience by combining a quantitative analysis of fisheries production data with a qualitative analysis of ethnographic data. For the quantitative analysis, we leverage long-term administrative fisheries data to 1) estimate the impact of each shock on economic performance of 237 economic units, 2) test for concordance between impacts from climate and market shocks, and 3) investigate the degree to which known determinants of adaptive capacity and resilience influence the magnitude of shocks of each system and historical variation in their revenues. To allow for comparison across hundreds of economic units, we focus on fishing revenues as our state variable. In this context, small-scale fisheries whose revenues are least affected by a shock are understood to be the most resistant, and therefore more resilient6.

We recognize that fishing and fisheries entail complex human activities that encompass more than just the financial performance of a fishery, involving the opinions, expectations, and beliefs of various individuals and communities14, sometimes with differing perspectives on relevant problems to be addressed. Accordingly, we also analyze ethnographic data from five different fishing cooperatives spanning four localities in Baja California and Baja California Sur, all of which are present in our fisheries production data. The inclusion of ethnographic data in the form of vignettes aims to bolster our quantitative analysis, shedding light on the interactions between the social and environmental components of small-scale fisheries15, thus offering a deeper understanding of how humans closely interact with biological organisms and ecological communities (sensu lato). Simultaneously, it explores how adaptation and change mutually influence individuals and human systems16.

This study area extends across the Pacific coastline of the Baja California Peninsula (Fig. 1), from the USA-Mexico international border (around 32.5°N) to Bahia Magdalena (around 24.5°N). The area hosts a diverse range of small-scale fisheries that have sustained local communities for generations17. The region’s high productivity and rich biodiversity support a variety of commercially important species such as red spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus), abalone (Haliotis spp.), sea cucumber (Apostichopus spp.), sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and Mesocentrotus franciscanus), sand bass (Paralabrax nebulifer), sheephead (Semycossyphus pulcher), jacks (Seriola lalandi and S. rivoliana), and wavy turban snail (Megastraea spp.), among others11,18,19. Fishing operations encompass a spectrum of gear types reflective of the ecological diversity of the marine ecosystem. Fishers use hook-and-line and gillnets to catch finfish, or rely on highly selective traps and hand-collection via hookah diving to catch invertebrates17. Catch harvested by the region’s small-scale fisheries enters a dynamic supply chain that links local fishers to regional and international markets in Mexico, the United States, and Asia.

Results

Changes in revenues during shocks

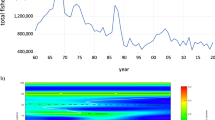

We begin our results with an overview of the average impacts of each shock on the standard-normalized revenues (simply “revenues” from hereinafter) across all economic units. Revenues during both shocks were below the baseline revenue levels, although there is considerable variation between economic units (Fig. 2A). Our generalized linear mixed model shows that fisheries revenues were lower during each shock, relative to the baseline (Fig. 2B and Table 1). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic [\({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{2i}}\) = -0.324 (SE = 0.069, p < 0.01)] was stronger than that of the marine heatwaves [\({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{1i}}\) = -0.250 (SE = 0.052, p < 0.01)]. These coefficients indicate that, on average, annual revenues were 0.25 and 0.324 standard deviations below the baseline mean during the marine heatwave regime and the COVID-19 period, respectively. Our model explains 14.5% of the variance in standard-normalized revenues (conditional R2 = 0.145; Table 1). Fixed effects alone accounted for 1.6% if the variation (marginal R2 = 0.016). Using semi-partial R2 defined as Δ-marginal R2, we estimated unique contributions of MHW: 0.29% (Δ-marginal R2 = 0.0029; 95% bootstrap CI: 0.0006-0.0079) and C19: 1.02% (Δ-marginal R2 = 0.0102; 95% CI: 0.0029-0.0216) (See methods for details).

A Shows 23 years of standard-normalized revenues from fishing. Points (and error bars) show annual means (and standard deviation) across all economic units. Each thin line in the background corresponds to an economic unit. B Shows central coefficient estimates for the impact of each shock on standard-normalized revenues (See Table 1). Thick error bars show standard errors and thin bars show 95% confidence intervals. MHW: Marine heatwave regime; C19: COVID-19 disruptions.

Two additional patterns emerge. First, heterogeneity in responses is substantial between economic units. The standard deviations of the unit-specific random slopes of marine heatwave and COVI-19 are \({\sigma }_{{\gamma }_{1i}}=0.436\) and \({\sigma }_{{\gamma }_{2i}}=0.893\) (Table 1), respectively. This indicates that many units experience impacts that differ from the average effect. Second, these unit-specific sensitivities co-vary positively: the correlation between the MHW and C19 random slopes is ρ = 0.552 (Table 1), meaning units that are more affected by one shock tend also to be more affected by the other. Note that Mexico experienced recessions during 2001–2003 and 2008–2009, but only the first event is captured by our data (Fig. 2). This was a period where Mexican exports suffered reductions20. Our results are robust to the exclusion of pre-2004 data from the baseline, to estimating housing market crash (’08–’09) effects, and to different specifications and definitions of shock periods (See Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Throughout workshops conducted with five cooperatives along the Pacific coast in 2022 and 2023, participants were asked to document the shocks experienced by their cooperative over its lifetime. An outline of our workshop activity is provided in Supplementary note 3 of our supplementary materials. Thematic coding of ethnographic data revealed that multiple drivers of change and shocks impacted the fisheries in all fishing cooperatives, with high variation among cooperatives in their perceived relative importance (Fig. 3). In particular, while “Climate change” or “Environmental change” were common answers in four of the five cooperatives (recorded 47 times), none of the participants from California San Ignacio labeled climate change or environmental shock as such. Conversely, this same cooperative (as well as Buzos y Pescadores and Nacionales de Abulón) highlighted social problems more frequently than other categories (see Fig. 3). The COVID-19 pandemic was explicitly cited as a driver of change in only two of the five cooperatives, with a total of 25 mentions (Fig. 3). See Supplementary Table 2 for explicit frequencies by cooperative and problem identified. All codified workshops and interviews are open-access and can be found at ref. 21, and a semantic network is provided in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The response is measured as the number of times (counts) members of each of the five cooperatives identified a category as a driver of change for their fisheries. The category 'Other' encompasses specific local issues of each cooperative. The numbers in the panel titles indicate the total number of responses from each cooperative.

Analysis of these data, contextualized with individual statements and direct field observations, revealed that answers related to social problems were more frequent (mentioned 52 times) and widespread across all cooperatives. Social problems are understood as disruptions to daily life that affect essential systems, including security, social services, public education, and healthcare. These issues challenge the resilience of human communities and often arise from environmental, economic, or political changes, increasing their complexity and impact on community stability and functionality.

The prevalence of social problems as salient responses, coupled with testimonies gathered during interviews and insights from informal interactions, suggests that cooperative members may prioritize social problems over other problems, including environmental or climatic impacts, particularly during periods of administrative turbulence and financial instability. Conversely, fishing cooperatives that self-reported effective administrative procedures and financial stability were better able to re-organize their sale strategies after the markets crashed during the pandemic. N, a fisher in Bahía Asunción recalls that “during the pandemic, there were two or three months where there was no market in which we could sell. What do you do when you can’t work and need to make a living? Well, these circumstances forced us to explore other markets, even national markets that demanded our product to be delivered in completely different ways from those we were already used to due to the demands of international buyers. Naturally, the volumes weren’t as high as we’d like, but we had to pursue sales during this time of the pandemic” (N., Bahía Asunción, June, 2023).

Concordance between climate and market impacts

We now move onto presenting the impacts specific to each economic unit, as well as the concordance analysis where we tested for the association between impacts. We found that 79.7% (N = 189) of economic units saw reductions in revenues during the marine heatwave regime, and 70.9% (N = 168) of economic units saw revenue reductions during the COVID-19 disruptions. But are these the same economic units? We identified a significant association between the impacts on revenues from the two different shocks in a majority of units (Fig. 4). The concordance analysis of these data yields a Kendall correlation coefficient of τb = 0.622, indicating a positive and statistically significant concordance between the two shocks (p < 0.01). This analysis shows concordance in responses to shocks for 86.1% of the units (N = 204; 68.4% with negative and 17.7% with positive impacts from both shocks). A remaining 11.4% (N = 27) of economic units were negatively impacted by marine heatwaves and positively impacted by COVID-19, while the opposite was true for 2.5% of them (N = 6).

The main plot shows a scatterplot of the pairwise magnitudes of the impact of two different shocks for each economic unit (i.e.γ1i and γ2i). Each point is an economic unit. Points lying closest to the origin at (0,0) correspond to the lowest impacts, and therefore the most resistant economic units. Conversely, points furthest away from the origin are the ones impacted the most, and are therefore the less resistant. Contour lines show a 2-dimensional density distribution of the data on the cartesian plane. Numbers within each quadrant indicate the proportion of observations contained in them, and gray panels indicate concordance quadrants where the sign of both impacts for a given economic unit is the same. Marginal densigrams show the distribution of the data along each axis; note the bias towards negative impacts.

Our ethnographic data offer further insights into the sources of resilience against these shocks. During the COVID-19 pandemic those reliant on lobster fisheries faced challenges during the closure of the Chinese seafood market9. However, upon its reopening, they experienced a surge in prices for their product, which served as compensatory revenue. Similarly, during the marine heatwaves, economically valuable fisheries such as abalone and lobster were negatively impacted. Yet, through redistribution of marine taxa, marine heatwaves may produce a temporary inflow of other species. When fishers are legally permitted to capture these now-abundant species, they can make use of a portfolio effect, offsetting losses from one fishery by bolstering revenues from another. This scenario underscores the rationale behind our following analyses, which focus on the intersection of resilience and diversity metrics.

To exemplify the aforementioned intersection, an experienced fisher from Bahía Asunción mentioned that from 1997 to 1999, during an extreme El Niño event, the cooperative was confronted with a high mortality of marine snails, clams, and lobster that impacted their yields. During that time, they focused on fishing with nets, particularly targeting California halibut (Paralichthys californicus, P. woolmani) and occasionally capturing dogfish (Galeorhinus galeus), which they used for their own consumption or exchanged with others for necessities. “Whatever surplus we had [O. said], we sold to cover expenses such as fuel or to seek loans, often from within the cooperative. It was a period where economic struggles were anticipated, so the key was to keep working. Sometimes, if a product wasn’t accepted by the cooperative as a marketable item, we found independent buyers who would purchase these products from us individually, providing our families with an alternative income source. Our approach wasn’t about getting rich but surviving and overcoming crises, whether from hurricanes or economic downturns. We’ve managed to weather such challenges, awaiting better times ahead. As they say, ‘We’ve come through it.’” (O., Bahía Asunción, March, 2023).

Drivers of resilience and concordance

What might explain why we see concordance for some, but not all economic units? We investigated how two known drivers of resilience (catch diversity and reliance on export markets) related to the impacts estimated in the previous section. We find that economic units with higher taxonomic diversity of catch showed smaller negative impacts of marine heatwave on revenues (Table 2, column 1). The coefficient on taxonomic diversity of catch is estimated at -0.206 (p < 0.05), while the coefficient of reliance on export markets is also negative (-0.088) but not statistically different from zero (p = 0.488). The pattern holds for impacts sustained during COVID-19 disruptions, with a negative coefficient of -0.273 (p < 0.1) on taxonomic catch diversity and -0.171 on reliance on export markets, which was also not significant (p = 0.61; Table 2, column 2). These findings only provide a partial view into domain-specific resilience.

When we used the coefficient of variation (Equation (3)) as an outcome variable to test for generalized resilience, we found that higher catch diversity and higher reliance on export markets were both weakly associated with lower coefficients of variation of revenues (i.e. less variation and thus more resilience; Table 2, column 3). In this case, only the coefficient measuring reliance on export markets was statistically significant (-0.331; p < 0.05), but that on catch diversity was also large and negative (-0.115;; p = 0.45).

Concordance was also partially driven by diversity in catch and reliance on export markets. Recall, however, that concordance simply measures whether the impacts from different shocks move in the same direction (i.e. resilience is generalized). Concordance between shocks increases as catch diversity decreases (Fig. 5A). Fig. 5 shows the same data as Fig. 4, but this time split into groups of low, medium, and high catch diversity (Fig. 5A) or reliance on export markets (Fig. 5B). Economic units with low catch diversity showed the highest concordance [τb = 0.659 (p < 0.01)], while those with medium or high diversity showed more moderate associations [τb = 0.619 (p < 0.01) and τb = 0.561 (p < 0.01), respectively]. In the case of reliance on export markets (Fig. 5B), economic units with low and medium reliance showed greater concordance [τb = 0.632 (p < 0.01) and τb = 0.669 (p < 0.01), respectively] than for those who specialize on export markets [τb = 0.562 (p < 0.01)].

A Separates economic units based on the observed catch diversity. B Separates economic units based on the proportion of catch destined to export markets. Contour lines in all panels show a 2-dimensional density distribution of the data on the cartesian plane. Note how the concordance between shocks is stronger for those with low diversity (A-Low) and medium reliance on export markets (B-Medium).

Notably, ethnographic data indicate that economic diversification is not limited to the waterfront. During a workshop with the Cooperative Ensenada, held in June 2023, we learned that many of the people working for the cooperative, especially fishers, diversified their investments and immersed themselves in agricultural activities such as cattle ranching and growing onions and other cultivars. Others developed a trade as mechanics, blacksmiths, and construction workers. Lastly, other fishers have alternative apparel stores and invest in real estate rentals among other economic ventures.

Discussion

The marine heatwave regime and the market disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic provided a unique natural experiment to investigate concordance in resilience of small-scale fisheries along the Pacific coastline of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Impacts of (and resistance to) each shock had been previously examined in the literature4,7,11, but the impacts during both shocks had not been simultaneously estimated and compared for the same set of economic units. Our work makes the following contributions: (1) we simultaneously quantify the impacts from two shocks, (2) we investigate the heterogeneity in responses among economic units, and (3) we compare the impacts from both shocks. By doing so, we show that both shocks led to temporary decreases in revenues for most economic units. However, our main finding is that we show a positive concordance in the direction and magnitude of impacts, suggesting generalized resilience. We also found evidence that the taxonomic diversity of catch and reliance on export markets might mediate generalizability of resilience in small-scale fisheries. Finally, ethnographic data confirm that our quantitative analysis reflects fishers’ perceptions of these shocks and their responses to them.

Our incorporation of ethnographic data also suggests that the way researchers frame questions and perspectives on shocks, climate change, and environmental impacts significantly shapes their ability to understand and interpret fishers’ responses in ways that align with local realities. When asked about market disruptions or heatwaves, fishers often intertwine these concerns with issues such as road maintenance, health services, and a perceived rise in crime (c.f.22). The complexity of these responses–where different aspects of fishers’ lives intersect–demonstrates how environmental and economic shocks manifest within both local and translocal contexts. This, in turn, provides crucial insights into how fishing communities experience and build resilience to such shocks, while also revealing the broader social dimensions through which these impacts unfold. The following paragraphs expand on our interpretation of these results, highlight implications for policy and management interventions, and discuss potential limitations of our work and directions for future research.

Our analysis revealed significant negative impacts of both marine heatwaves and COVID-19 disruptions on fisheries revenues, consistent with previous analyses of the impacts of each shock4,7,11. The substantial variation in the magnitude and direction of the impacts from each shock suggests that the capacity of small-scale fisheries to respond to shocks may be context-dependent and locally driven23,24. Consistent with our main hypothesis that resilience to climate shocks implies resilience to market shocks, we observed a moderate level of concordance between the impacts of marine heatwaves and COVID-19 disruptions. While a majority of economic units experienced reduced revenues during each shock, the degree of agreement varied, suggesting differential responses to environmental and market stressors. Understanding the processes behind these deviations may prove a fruitful area of research for future work.

We also show that known drivers (diversity of catch and markets, as well as institutional arrangements) influence the resilience of small-scale fisheries to external shocks. While previous literature has emphasized the role of governance structures and institutional arrangements in fostering adaptive capacity25, we find that factors such as catch diversity and reliance on export markets may play important roles in mitigating the impacts of shocks (e.g. ref. 26). Higher catch diversity and reliance on export markets were weakly associated with lower revenue losses (i.e. higher resistance) during both marine heatwaves and COVID-19 disruptions, indicating greater adaptive capacity of economic units with diversified portfolios and market connections. Furthermore, these factors also contributed to reduced variability in long-term revenues, suggesting that operational flexibility and market integration play crucial roles in mitigating the impacts of shocks. These conclusions align with the findings of ref. 27, who showed that fishers who fared better during the COVID-19 disruptions were those who leveraged their ability and willingness to learn how to use social media to explore new markets from younger people.

Resilience has been associated with a diversified catch portfolio or a diversified market28,29. In contrast, the association between reliance on export markets and variation in revenue may be puzzling. The relationship between reliance on export markets and resilience should not be taken as a causal link. Instead, it is likely that reliance on export markets and resilience are both determined by other attributes that confer resilience. For example, engaging in international operations requires large capital investments and asset holding, strong foundations in administration, and an efficient supply chain. These attributes echo four of five key domains thought to support adaptive capacity: assets, flexibility, ability to organize, and agency to determine a response3. When borders were closed during the pandemic, these vertically integrated economic units were able to swiftly adapt to targeting local markets. Another potential explanation pertains to the portfolio of species that are exported versus sold domestically. Exported species include invertebrates such as lobster, sea urchin, abalone, and sea cucumber. These typically fetch higher prices compared to species consumed domestically, such as finfish. When international trade was disrupted, fishers targeting these high value species were still able to find a domestic market for their products using their national distribution channels and greater operational capacity. Both explanations are supported by our ethnographic observations, as well as previous work in the region4 and elsewhere30.

Interestingly, economic units with low catch diversity exhibited stronger concordance between shocks. Recall that concordance is merely a measure of the generalizability of resilience, not of resilience itself. Economic units with low catch diversity were frequently the ones with large negative impacts from both shocks. We note, however, that those focusing on only a few species are also those who have medium to high reliance on export markets.

We show that resilience is, to a degree, generalizable across domains. This implies that actions and investments designed to foster resilience in one domain may indirectly foster resilience in other domains. Our findings therefore have important implications for the development of policies and management strategies aimed at enhancing the resilience of small-scale fisheries. Our results suggest that policies that allow fishers to diversify their catch portfolio could buffer against the adverse effects of both environmental and economic disturbances28,31. This is also supported by existing literature. For example, when faced with environmental extremes, small-scale fishers in Baja California are known to shift their effort towards a few climate-resilient and high-value species11,31. On the other hand, small-scale fishers in Kenya and Ecuador provide further examples of diversification as an adaptive response, but this time to COVID-19 disruptions. In each country, small-scale fishers switched to different species or began selling their catch directly to seafood consumers, as opposed to middlemen30,32. It is important to note that fishers can only legally undertake these adaptive actions if they hold permits to those high-value and climate-resilience fisheries. Policies that incentivize diversification of catch must contemplate the inherent tradeoffs of inducing overfishing and fleet overcapacity.

It is essential to acknowledge several limitations of this study. We focused on revenue as a proxy for resilience because revenue data was readily available, but we recognize that other dimensions exist, such as social well-being, food and nutritional security, and ecological sustainability, which warrant further investigation. However, we highlight that revenue is often considered an important bottom-line, especially in regions where fishers live at or below the poverty line33 and the closure of markets due to COVID-19 or reduced landings during marine heatwaves are first order impacts on income.

Our analysis is constrained by data availability and granularity, limiting the depth of understanding regarding the underlying mechanisms driving resilience dynamics. For example, we do not observe the geographic location of each economic unit’s fishing activity, which hinders our ability to measure their direct exposure to warm-water events during marine heatwaves as done elsewhere in the literature (e.g. ref. 7). We also don’t observe other important measures and determinants of adaptation and resilience, such as assets, community structure, networks of communication which could increase precision in our models of driver of resilience24,26. Similarly, our inference is hindered by the lack of a temporal evaluation of the other potential shocks experienced by the fishers (but see Supplementary Table 1 for other shocks), and note that ethnographic methods can help fill in the gaps when data sets are not readily available, as done in ref. 34. Our work thus paves the way for future research that could empirically explore how additional factors such as governance structures, institutional arrangements, and socio-cultural dimensions shape resilience.

We must also emphasize the observational nature of our work. While marine heatwaves and market disruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic can be considered as exogenous to fisheries production, our data are not analyzed in a causal inference framework. For instance, we do not have counterfactual communities that could allow us to implement a difference-in-differences approach. Instead, we estimate reductions in revenue to each economic unit relative to their baseline revenues outside the two shock periods. This means that while we can confirm that changes in revenues coincide with each of these shocks, we can not causally attribute the entirety of variation to these shocks. This is because other time-varying and unobserved factors influencing fisheries production and profitability might have changed at the same time as we observe these shocks. Yet, we are unaware of any other disruptions that would coincide with our shock periods and that would result in decreases in revenues. Similarly, taxonomic diversity of catch and reliance on export markets are, to an extent, endogenous. This is because economic units can decide whether or not they engage in different fisheries, within the constraints provided by fisheries regulations.

Conclusion

We examined whether climate-resilient fisheries were also more resilient to market shocks. Using long-term data of small-scale fisheries exposed to environmental and market shocks, we find that most of the 237 economic units for which data are available were similarly affected by both shocks. By the concordance between shocks we conclude that climate-resilient fisheries are generally more resilient to market shocks, and that this may generalize to other types of shocks. Our work contributes to a growing body of literature on resilience of small-scale fisheries and coastal social-ecological systems, and highlights areas where single-domain interventions might enhance resilience in more than one domain. Importantly, we show that fishers can articulate what has empirically occurred. Therefore, their oral histories should be valued as additional and valid data points in understanding how fishing communities experience and build resilience to these shocks.

Methods

Data sources and sample construction

Our work leverages administrative fisheries production data for the quantitative portion of the analysis and ethnographic data for the qualitative analysis. Each data set and their respective analyses are described in detail below. However, our division of the timeline into three periods is common to both approaches and is as follows. The first period pertains to the intense marine heatwave regime, which developed late in 201435,36. Therefore, we categorize 2015 and 2016 as years impacted by marine heatwaves. The second period refers to the period between 2020 and 2022, years that were impacted by COVID-19 disruptions. While lockdowns and the most severe disruptions occurred during 2020, the global public health crises declaration by the World Health Organization prevailed through May 5, 202337. The remaining years (2000–2014 and 2017–2019) are considered the “baseline” period. This baseline period denotes years not impacted by marine heatwaves or COVID-19 disruptions, but it does not assume absence of other shocks that might affect revenues. Data from these baseline years allow us to establish the expected revenue during years without heatwaves and without COVID-19 disruptions, but includes any negative and positive shocks that might have occurred then as has previously been suggested, mainly through ethnographic research34.

To understand the impact of climate and COVID-19 shocks on small-scale fisheries production, we use publicly available fisheries production data reported to CONAPESCA, Mexico’s fishery management agency. The data include monthly records of seafood production and retail prices in Mexico, from 2000 to 2022, for all registered economic units.

Catch data are reported into 38 retail product categories, which we re-classify into 28 taxonomic groups based on the species and species groups caught and traded. We attempt to obtain the highest taxonomic resolution relevant to the group’s market value. For example, the data report “atún” (tunas), “bonito” and “macarela” (mackerel) and “sierra”. All are Scombrids, but when it comes to market value, tunas are far more valuable than smaller Scombrids. In this case, we group tunas into “Tunnus” and the other fish into “Scombrids”. For a full list of market and taxonomic groups see Supplementary Table 3.

The data are roughly reported on a monthly basis, so we aggregated the data annually. We then filtered data to retain observations belonging to small-scale economic units that report their wild-caught products in the states of Baja California and Baja California Sur, and for which taxonomic information is available (N = 1000 economic units). We then remove data for freshwater species and species that are not distributed in the area, as well as economic units that operate in the Gulf of California. We further restricted economic units to those with >10 years of data, and that we observe in all three periods of interest (N = 302). Finally, we remove economic units with <5 years of observations during the period leading to the marine heatwave regime (2000–2014), and units with revenues that fluctuate by more than five standard deviations relative to their historical mean (likely erroneous data entries). The final data set contains 237 economic units.

After the filtering and aggregation procedures, we manually assigned each economic unit a category that indicates their type (i.e. a fisher, fishing cooperative, or a fishing company) based on the economic unit’s name. We also identified each taxonomic category as having a predominantly domestic or international target market based on existing literature38,39. These categories are only meant to indicate the prevalent end-market of a product, but we recognize that no species is exclusively exported or exclusively locally consumed. Our final data set contains the revenue derived from fishing 28 groups of species for 237 economic units operating in the Pacific coastline of the Baja California Peninsula between 2000–2022. Revenues were reported in nominal terms, so we used Mexico’s annual consumer price index40 to standardize them to 2019 Mexican pesos.

We use these data to calculate our two main outcomes of interest. Annual revenues by economic unit are used to track the performance of the system through time41. Then, we use the coefficient of variation of annual revenues as a measure of the long-term variation in revenues from each economic unit. We also calculated relevant explanatory variables, like catch diversity and reliance on export markets (Equations (4) and (5), respectively). All computed measures are defined below.

The total annual revenues (Rit) to economic unit i at time t are given by the sum of the revenues across all their target species groups:

where rijt represents the revenue of economic unit i from fishing species group j at time period t. To allow comparison between vastly different economic units, we standard-normalize revenues of each economic unit by subtracting the sample mean of the revenues (μi) and dividing by the sample standard deviation (σi) for all years baseline years (i.e. \(t\in \left(2000:2014,2017:2019\right)\)):

The coefficient of variation is simply the ratio of sample standard deviation to the mean:

We use the Simpson’s index of diversity to characterize each economic unit’s catch diversity, that is:

where \({\bar{r}}_{ij}\) is the sum of all revenues perceived by economic unit i from fishing species group j across all years t (i.e.\({\bar{r}}_{ij}=\mathop{\sum }_{t = 1}^{T}{r}_{ijt}\)). This approach balances the number of species groups and the relative contribution of each group to the total revenue stream of each economic unit. The index is bound between 0 (when the economic unit’s revenues are from one sspecies group only) and \(1-\frac{1}{J}\) (when all species groups J contribute equally to the revenues of the economic unit).

Reliance on export markets is described as the proportion of all revenue to unit i that is attributable to species groups identified as mainly having an export market:

where E is a vector whose elements Ej = 1 if the endmarket is an export market and Ej = 0 otherwise. Therefore, a value of Mi = 0 implies that economic unit i specializes in domestic markets, a value of Mi = 0.5 implies it has a balanced portfolio of domestic vs. export markets, and a value of Mi = 1 implies they specialize in export markets.

We also employed an ethnographic approach to understand fishers’ perceptions of the impacts of both marine heatwaves and the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach involves engaging in informal conversations during everyday events and community activities, such as cooperative assemblies, fishing preparations, community tours, and formal conversations with structured questions administered in workshops that we organized to investigate specific topics related to shocks and resilience in fishing. This methodology allowed us to interact with 169 individuals living in four communities in the central region of Baja California, which are home to five fishing cooperatives: (1) “Ensenada” in El Rosario, (2) “Buzos y Pescadores de Baja California” in Isla Natividad, (3) “Pescadores Nacionales de Abulón” in Isla de Cedros, and (4) “Leyes de Reforma” and (5) “California de San Ignacio” in Bahía Asunción (Fig. 1). Whenever feasible, interactions were captured through audio recordings and supplemented with contextual information recorded ipso facto in ethnographic fieldnotes. These recordings and notes were then utilized to create daily entries in a field journal42.

Audio recordings of interactions with local community members were transcribed and categorized using the software Atlas.ti 8. To move beyond a mere anecdotal description, we employed an inductive thematic coding approach. This involved assigning codes to sentences or words referring to specific actions, attributes, or behaviors, as outlined by ref. 43. Our coding process aimed to identify emergent patterns in the data by initially organizing them into large thematic categories, which were then further refined with additional codes. This facilitated the exploration of agreements and discrepancies among individuals and communities.

Additionally, to understand and interpret fishermen risk perceptions (i.e., climate change, market/commercialization problems, social problems, sanitary problems, political problems and fisheries output) and their subcomponents (e.g., security and delinquency, pollution, trash, isolation and lack of communication infrastructure, tourism/gentrification, to name a few) we relied on emic definitions given by individual participants organized through a pile sorting approach44. Pile sorting is an emic and participatory method in which participants construct cultural domains by grouping items (often represented on cards) into piles based on criteria that are most salient to them, thus creating meaning for complex issues within their own social and cultural frameworks45.

In our study, we applied the pile sorting method to understand local perceptions of risk and change, following the approach of ref. 46. We first asked cooperative personnel to freely list all the problems or concerns that posed risk or change in their daily lives. These items were then written on cards and used in a pile sort exercise. Participants were asked to sort the cards into groups according to perceived similarity or relatedness. After sorting, each group was discussed collectively to determine the nature and significance of the items it contained. Through consensus, participants then assigned a name or label to each pile, which served to define thematic categories of risk and change relevant to their lived experience.

Data analyses

To understand whether climate-resilient fisheries are also more resilient to market shocks we must first measure their impacts from each shock. Therefore, we estimate the impact of each shock on normalized revenues using a generalized linear mixed model. We regress the annual normalized revenues on two sets of dummy variables that indicate whether a given year was exposed to marine heatwaves or COVID-19 disruptions, and we allow for random effects of each shock by economic unit. Following notation from ref. 47, our main specification is:

where MHWt and C19t are dummy variables and EU denotes economic unit i. MHWt = 1 during years corresponding to the marine heatwave regime (2015-2016) and 0 otherwise. Similarly, C19t = 1 during years corresponding to the COVID-19 disruptions (2020-2022) and 0 otherwise. Therefore the coefficients \({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{1i}}\) and \({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{2i}}\) represent the mean deviation of standard normalized revenues relative to the baseline and thus capture the average impact of each shock. For example, \({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{1i}} < 0\) implies that, during the marine heatwave regime, average standard-normalized revenues across all economic units were lower than the baseline.

The coefficients γ1i and γ1i capture the average impact of each shock on each economic unit. This means that economic units that are more resistant than average are characterized by values of \({\gamma }_{1i} > {\mu }_{{\gamma }_{1i}}\) or \({\gamma }_{2i} > {\mu }_{{\gamma }_{2i}}\), and units that are less resistant than average will show values of γ1i and γ2i lower than \({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{1i}}\) and \({\mu }_{{\gamma }_{2i}}\), respectively. Note that we do not estimate an intercept because, in the absence of a shock, standard-normalized revenues should also be 0 by construction. We later perform robustness checks where we relax this assumption and allow for a free-varying intercept (β0), where we modify the annual ranges for the baseline, marine heatwave and COVID-19 periods, and where we account for the potential effects of the 2008 financial crisis (See Supplementary Table 1). Model fitting was performed with the lme4 package48 in R version 4.5.1 (2025-06-13) through RStudio 2025.05.049.

We computed semi-partial R2 as delta-marginal R2. That is, we calculated the difference between the full model’s mariginal R2 and the marginal R2 of reduced models with the focal fixed effect and its corresponding random slope removed. We then calculated 95% confidence intervals via parametric bootstrap CIs (1,000 simulations; tossing simulations with singular fit).

For the ethnographic component of our research, we identified instances where two or more codes occurred together in the same data context. We conducted a co-occurrence analysis to assess the proximity of codes. This method helped us identify connections between concepts, revealing patterns in the data from detecting covert relationships between different concepts within a dataset50.

In the specific context of this research, co-occurrence analysis allowed us to understand complex relations between marine heatwaves, the COVID-19 pandemic, and fisheries production. It is important to acknowledge that the complete understanding of these links involves examining specific quotations where concepts co-occur and understanding the underlying contextual meanings behind these associations50.

For this analysis, we used the Co-Occurrence Tool in ATLAS.ti. We entered the codes “COVID” and “COVID Pandemic” to examine their co-occurrence with the following codes: “economy,” “market,” “heat wave,” “risk,” “climate change,” and “environment.” When entering these codes, additional codes such as “price increase” and “product inflation” also emerged.

We asked whether economic units that experienced a reduction in revenues during the marine heatwave regime also exhibited a reduction in revenues during the COVID-19 shock. This implies a relationship in which the impacts move in the same direction, but not necessarily at the same rate. This means that the unit most impacted by marine heatwaves does not necessarily have to be the unit most impacted by COVID-19. We tested for a monotonic relationship between impacts to each economic unit. We use Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient (τb), which summarizes the concordance between two variables and ranges from -1 (negative association) to 1 (positive association); a value of zero indicates no association51. This test for concordance between impacts is simultaneously a test for concordance in resistance, because the most resistant economic units are the ones that exhibit the smallest impact. Therefore, high concordance between impacts equates to high concordance in resistance.

We test for the association between resistance and two hypothesized drivers of environmental and economic resilience: diversity of catch and reliance on export markets. We first model the economic-unit specific impacts from marine heatwave and COVID-19 (i.e.γ1i and γ2i) in response to both drivers using multiple linear regressions. We multiplied outcome variables by -1 to more easily interpret the regression coefficients from this analysis. That is, a positive coefficient means that an increase in the driver is associated with an increase in the magnitude of the negative impact, and vice versa.

We also model the coefficient of variation of revenue (See Equation (3)) as a function of diversity of catch and reliance on export markets. This is a test for generalized resilience, where a positive coefficient on a driver indicates that it is associated with increased variation in revenues, while a negative coefficient is associated with a decrease in variation. All multiple linear regressions incorporate fixed-effects by type of economic unit.

Finally, we investigated how catch and market diversity drive concordance between shocks. Specifically, we partitioned our sample into three taxa diversity and three market diversity groups by dividing each into three equally spaced bins (i.e., 0–0.33; 0.33–066; and 0.66–1). We then performed a concordance analysis for each subset of data falling into each bin.

Data availability

All data are available on GitHub at: https://github.com/jcvdav/resilient_ssf.

Code availability

All code is available on GitHub at: https://github.com/jcvdav/resilient_ssf.

References

Allison, E. H. et al. Vulnerability of national economies to the impacts of climate change on fisheries. Fish Fish 10, 173–196 (2009).

Basurto, X. et al. Illuminating the multidimensional contributions of small-scale fisheries. Nature 637, 875–884 (2025).

Cinner, J. E. et al. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 117–123 (2018).

Lopez-Ercilla, I. et al. The voice of Mexican small-scale fishers in times of COVID-19: Impacts, responses, and digital divide. Mar. Policy 131, 104606 (2021).

Mangubhai, S. et al. COVID-19 highlights the need to improve resilience and equity in managing small-scale fisheries. NPJ Ocean Sustain 3, 61 (2024).

Grafton, R. Q. et al. Realizing resilience for decision-making. Nat. Sustain. 2, 907–913 (2019).

Villaseñor-Derbez, J. C., Arafeh-Dalmau, N. & Micheli, F. Past and future impacts of marine heatwaves on small-scale fisheries in Baja California, Mexico. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 623 (2024).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Social equity and marine protected areas: erceptions of small-scale fishermen in the Mediterranean Sea. Biol. Conserv. 244, 108531 (2020).

Knight, C. J., Burnham, T. L. U., Mansfield, E. J., Crowder, L. B. & Micheli, F. COVID-19 reveals vulnerability of small-scale fisheries to global market systems. Lancet Planet Health 4, e219 (2020).

Macusi, E. D. et al. Impacts, challenges, and adaptation of small-scale fishers during the COVID-19 pandemic in selected tropical countries. Aquat. Sci. 86, 33 (2024).

Micheli, F. et al. Social-ecological vulnerability to environmental extremes and adaptation pathways in small-scale fisheries of the southern California current. Front. Marine Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1322108 (2024).

Gephart, J. A., Deutsch, L., Pace, M. L., Troell, M. & Seekell, D. A. Shocks to fish production: identification, trends, and consequences. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 24–32 (2017).

Ilosvay, X. E. E., Molinos, J. G. & Ojea, E. Stronger adaptive response among small-scale fishers experiencing greater climate change hazard exposure. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–9 (2022).

Vina, M. Conservación, bienestar y las ecologías de compartir en la Costa Sur de la Provincia de Manabí, Ecuador. Vol. 224–244 (El Colegio de Michoacán 2022).

Biersack, A. & Greenberg, J. B. Reimagining Political Ecology: Culture/power. Vol. 440 (2006).

Aswani, S. New directions in maritime and fisheries anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 122, 473–486 (2020).

McCay, B. J. et al. Cooperatives, concessions, and co-management on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Mar. Policy 44, 49–59 (2014).

Díaz, G. P., Weisman, W. & McCay, B. Co-responsibility and participation in fisheries management in Mexico: lessons from Baja California Sur. Pesca y Conserv 1, 1–9 (2009).

CONAPESCA. Anuario Estadístico de Acuacultura y Pesca. https://www.gob.mx/conapesca/documentos/anuario-estadistico-de-acuacultura-y-pesca (2022).

Mejía Reyes, P., Díaz Carreño, M. A. & Vergara González, R. Recessions in mexico at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Prob. Des. 48, 57–84 (2017).

Garibay-Toussaint, I. & Narchi, N. E. Dises: Pathways and Constraints to Adaptation in Coastal Social-Environmental Systems. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/QW8G0S (2025).

Reilly-Moman, J. Social indicators of climate resilience: engaging care on latin america’s coasts. AGUFM 2022, SY42A–06 (2022).

Adger, W. N. et al. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim. Change 93, 335–354 (2009).

Willroth, P., Massmann, F., Wehrhahn, R. & Revilla Diez, J. Socio-economic vulnerability of coastal communities in southern thailand: the development of adaptation strategies. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 2647–2658 (2012).

Frawley, T. H. et al. Self-governance mediates small-scale fishing strategies, vulnerability and adaptive response. Glob. Environ. Change 84, 102805 (2024).

Dolan, A. H. & Walker, I. J. Understanding vulnerability of coastal communities to climate change related risks. J. Coast. Res. 39, 1316–1323 (2006).

Espinoza-Tenorio, A. et al. Between uncertainty and hope: Young leaders as agents of change in sustainable small-scale fisheries. Ambio 51, 1287–1301 (2021).

Dee, L. E. et al. Functional diversity of catch mitigates negative effects of temperature variability on fisheries yields. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283, 1836 (2016).

Mason, J. G. et al. Attributes of climate resilience in fisheries: from theory to practice. Fish Fish 23, 522–544 (2022).

Viteri Mejía, C. et al. Fishing during the “new normality": social and economic changes in Galapagos small-scale fisheries due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Marit. Stud. 21, 193–208 (2022).

Finkbeiner, E. M. The role of diversification in dynamic small-scale fisheries: lessons from baja California Sur. Mexico. Glob. Environ. Change 32, 139–152 (2015).

Lau, J. et al. COVID-19 impacts on coastal communities in Kenya. Mar. Policy 134, 104803 (2021).

Teh, L. S. L., Teh, L. C. L., Giron-Nava, A. & Sumaila, U. R. Poverty line income and fisheries subsidies in developing country fishing communities. npj Ocean Sustain. 3, 1–9 (2024).

Garibay-Toussaint, I. et al. Combining the uncombinable: corporate memories, ethnobiological observations, oceanographic and ecological data to enhance climatic resilience in small-scale fisheries. Front. Marine Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1458059 (2024).

Laufkötter, C., Zscheischler, J. & Frölicher, T. L. High-impact marine heatwaves attributable to human-induced global warming. Science 369, 1621–1625 (2020).

Arafeh-Dalmau, N. et al. Extreme marine heatwaves alter kelp forest community near its equatorward distribution limit. Front. Marine Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00499 (2019).

World Health Organization. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.who.int (2025).

Trejo, V. N. H. Estudios Sobre Economía Ambiental y Agrícola En México (Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, 2019).

FAO. Mexico GLOBEFISH Market Profile - 2020 en. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cc5625en (2023).

OECD. Prices - Inflation (CPI) - OECD Data en. https://data.oecd.org/price/inflation-cpi.htm (2023).

Grafton, R. Q., Squires, D. & Fox, K. J. Private property and economic efficiency: a study of a common-pool resource. J. Law Econ. 43, 679–714 (2000).

Bernard, H. R. Unstructured and semistructured interviewing research methods in anthropology. In Qualitative and Quantitative Approach (ed. Leavy, P.) (1995).

Urquhart, C. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide 2 edn (SAGE Publications, 2022).

Arabie, P. & Boorman, S. Multidimensional scaling of measures of distance between partitions. J. Math. Psychol. 10, 148–203 (1973).

Horne, L. R., de Urioste-Stone, S., Daigle, J. & Noblet, C. Using pile sorts to understand perceptions of climate change. In Sustainable Tourism VIII, (eds. Syngellakis, s. et al.)175–183 (WIT Press, 2018).

Boster, J. The successive pile sort. Cult. Anthropol. Methods 6, 7–8 (1994).

Gelman, A. & Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/hierarchical Models 1st edn, Vol. 648 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2025).

Contreras, R. B. Examining The Context In Qualitative Analysis: The Role Of The Co-occurrence Tool In ATLAS. https://atlasti.com/manuals-and-documents (2011).

Kendall, M. G. & Gibbons, J. D. Rank Correlation Methods (E. Arnold ; Oxford University Press 1990).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge all cooperatives and participants in ethnographic study. This project was supported by NSF DISES grant 2108566. N.A.D was also supported by the Estate Winifred Violet Scott (Australia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JCVD conceived the project, curated the data, designed the analysis, carried out analysis, and wrote the manuscript. JL conceived the project, designed the analysis, wrote the first draft, and edited the manuscript. IGT collected data, designed analyses, and analyzed ethnographic data, and edited the manuscript. NEN collected, designed analyses, and analyzed ethnographic data, and edited the manuscript. ROC edited the manuscript. COJ edited the manuscript. GADL edited the manuscript. JT procured funding and edited the manuscript. NAD edited the manuscript. SF edited the manuscript. CBW procured funding and edited the manuscript. FM conceived the project, procured funding and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villaseñor-Derbez, J.C., Lynham, J., Garibay-Toussaint, I. et al. Climate-resilient fisheries are more resilient in general. npj Ocean Sustain 4, 56 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00154-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00154-1