Abstract

Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) is a crucial tool for the sustainable use of ocean resources, requiring the negotiation of trade-offs among ecological, economic, and social interests. This study validates a participatory four-block methodology—preparation, option setting, trade-off negotiation and implementation—applied across six European case sites within the MSP4BIO project. It produced practical guidance—especially for the ‘Trade-off Negotiation’ phase, in a participatory context. This process was operationalized across the sites through three core phases: (I) preparation, (II) collaborative engagement with stakeholders, and (III) post-meeting consolidation. Participatory mapping tools such as SeaSketch were used to visualize spatial conflicts and support stakeholder engagement. Findings show that trade-offs are highly context-specific, requiring flexible, data-driven, and inclusive decision-making processes. Common challenges include data limitations, varying technical capacities, and the need for stronger integration of MSP and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). A qualitative cross-case comparison emphasized the importance of harmonized and adaptive methods to support participatory governance, and ecological resilience in the face of climate change and increasing anthropogenic pressures on marine environments. This study is the first operational test in case sites, across six European sea basins, and present the comparative validation of the Calado et al1. Trade-offs method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maritime spatial planning (MSP) is a strategic approach that has emerged as a critical tool for the sustainable use of marine resources2,3. This approach aims to mitigate conflicts among different sectors, fostering harmony between maritime activities and the ecological boundaries of marine ecosystems. Central to MSP is the challenge of balancing competing interests and needs, which inherently requires negotiation and compromise, and primarily an in-depth analysis and understanding of trade-offs as part of the decision-making process4,5.

This analysis involves assessing the potential benefits and costs of different uses or management strategies, considering ecological, social, and economic factors. A careful evaluation of these various factors and interests is fundamental for identifying near-optimal solutions that reconcile current and future human uses, as well as maritime development and conservation efforts4,5,6,7.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) represent one of the most effective area-based tools for conserving marine ecosystems and restoring ocean natural capital. They help safeguard biodiversity and enhance ecological resilience7,8. Integrating MPAs into MSP allows decision-makers to better balance conservation goals with resource use, promoting a more inclusive and sustainable blue economy. Together, MPAs and MSP can strengthen ocean governance by aligning conservation with strategic spatial management in increasingly disputed marine environments. However, to ensure long-term success, it is crucial that MPA design and implementation processes prioritize inclusivity, equity, and adaptability, especially as forthcoming restrictions on extractive activities may challenge social sustainability5,9.

Several types of trade-offs that arise in MSP and marine conservation have been identified1,10,11. These trade-offs can be categorized into five general types:

-

1.

Trade-off between conservation and economic development objectives: MSP necessitates a delicate equilibrium between safeguarding marine ecosystems and supporting economic activities, such as fishing, shipping, and tourism12,13,14. For instance, the designation of MPAs can restrict opportunities for fishing and tourism, affecting the monetary revenue generated from these activities15.

-

2.

Trade-off between short-term and long-term benefits: It is necessary to balance the immediate gains of specific activities and the long-term benefits of preserving marine ecosystems15. For instance, permitting oil and gas exploration and drilling may offer short-term economic benefits but could produce irreversible impacts on the environment and marine life16.

-

3.

Trade-off between exclusive uses and shared uses: Decision-making on allocating marine space may involve trade-offs between exclusive use for a specific activity or multiple shared uses. This requires considering diverse stakeholder interests and balancing activities like fishing, recreational zones, shipping lanes, and conservation activities17,18.

-

4.

Trade-off between specific stakeholder interests: Divergent priorities and objectives among stakeholders, including commercial fishermen, local communities, conservation organizations, researchers, maritime tour operators, and non-governmental organizations, necessitate trade-offs to accommodate varied perspectives15,19.

-

5.

Trade-offs between local and regional interests: While MSP can benefit local communities through economic development and job creation, it must also account for the impact of human activities on the global ocean ecosystem11. Over-fishing in one region, for example, can detrimentally affect fish populations in other areas.

Importantly, these trade-offs are context-specific and depend on the unique circumstances of each MPA and/or MSP process. Therefore, the objective of this work is to validate these five typologies of trade-offs through the drivers and objectives set in six representative case sites from European sea basins, selected within the context of the MSP4BIO project11. Additionally, it aims to present the implementation of a common and coherent approach and guidance that supports comparative analyses of trade-offs across Europe, despite the context-specific conditions of each case site, facilitating the generation of insights and recommendations for managing future trade-offs in MSP and MPA processes.

The rationale for the pan-European implementation of a coherent trade-off analysis methodology is based on the fact that, despite overarching EU-established aims, MSP and MPA processes across Europe have generally been conducted in a fragmented and uncoordinated manner between Member States, resulting in significant methodological variability among countries20,21. While the context-specific adaptation of methods and analysis of outcomes is understandable and even necessary—given distinct national priorities, governance frameworks, stakeholder dynamics, and data availability—the lack of methodological coherence and standardized approaches poses substantial challenges for cross-national coordination20,22. This fragmented landscape underscores the need for harmonized methodologies and guidelines to enhance transboundary cooperation, ensure the comparability and transferability of knowledge and lessons learned, and ultimately promote coherent and integrated spatial planning strategies across the European seas. Despite the rapid evolution of MSP literature over the last decade, this study is the first Trade-offs method in MSP, with an operational and clear methodology (offering also guidance for tailored methods if needed) for testing in case sites, across six European sea basins, and presents the comparative validation of the Calado et al.1 trade-offs method.

Successfully meeting Europe’s ambitious conservation and restoration targets in the coming decade demands, now more urgently than ever, coordinated and integrated spatial planning actions. These efforts must strategically balance economic development with environmental sustainability, while ensuring effective conservation and restoration practices that maintain and recover resilient, healthy marine ecosystems. In this context, the methodology and guidelines presented by Calado et al.1 and applied in this study represent the first comprehensive effort to establish a fully operational approach for participatory-based trade-off analysis tailored to be applied across Europe.

Results

Evaluating the methodological approach to trade-offs: insights from the case studies

This section presents site-specific outcomes from the application of the guided trade-off methodology. It is important to note that many of the insights presented here, particularly those related to natural habitats and perceived trade-offs, are based on declarative statements provided by members of the Communities of Practice (CoP) during participatory sessions. As such, they reflect stakeholder perceptions and context-specific knowledge. Across all case study sites, the core trade-off encountered was between conservation goals and economic development (Table 1). However, the way this trade-off manifested, and the degree to which it was negotiated, varied depending on ecological, social, and governance contexts.

In the Azores Case Study, Graciosa Island, one of the nine islands of the Azores archipelago, was selected as a reference to develop the MSP4Bio activities. Its manageable scale, the existence of a well-identified and representative group of stakeholders, and ongoing conservation and spatial planning initiatives provided a suitable context for testing trade-off negotiation processes.

In this case, trade-off negotiations centered on expanding protection around an existing MPA through the proposal of a new protected area under International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) category VI. This category designates areas managed primarily for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems and resources. The trade-offs identified included conflicts between marine conservation and economic development, ecological integrity and human use, exclusive versus shared uses, and between specific stakeholder interests.

Stakeholders from various sectors, including members of the Regional Government and Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), as well as the Fishermen’s Association and tourism sector representatives, who later joined the original CoP, collaborated to spatially represent potential conflicts, their area of use, and perceived vulnerabilities related to climate change. The participatory mapping, supported by the SeaSketch tool, facilitated a better comprehension of competing interests, like tourism and conservation. A dedicated forum was proposed for the Praia Islet, a small yet ecologically significant area located off the eastern coast of Graciosa Island, to foster stakeholder engagement. The discussions were based on mapped outputs and centered on measures such as limiting tourism activities and prohibiting fishing to enhance ecological protection in the proposed area.

Participants outlined conditions for supporting a new MPA, including participatory monitoring, increasing ocean literacy, proposing alternative schedules for residents, providing scientific data supporting MPA needs, and creating special conservation areas for sustainable use. Balancing exclusive and shared uses, as well as addressing specific stakeholder interests, remained central themes throughout the trade-off discussions. It was also concluded that integrating new members into the CoP is essential for enriching perspectives or using a more flexible working group. Several arguments and trade-off scenarios were explored, such as the impact of marine reserves on tourism-related businesses and the trade-off between ecological integrity and human use. Key themes emerging from the workshop included the importance of participation, ocean literacy, and effective stakeholder communication and engagement.

Challenges emerged, particularly regarding logistical constraints for in-person meetings and difficulties in reaching consensus on trade-offs. However, the structured participatory approach fostered deeper engagement, leading to co-developing recommendations for improvement, such as holding meetings in fishermen’s communities, increasing stakeholder involvement in surveillance efforts, and addressing stakeholder fatigue.

For the Bay of Cadiz Case Study, the methodology was applied to explore how to support more effective and coordinated management of the ‘Fondos Marinos de la Bahía de Cádiz’ MPA, which has been largely considered a ‘paper park’ due to limited enforcement and the lack of effective management. The core trade-off identified in this site was between marine conservation and local economic practices, particularly illegal but culturally embedded shellfish harvesting. The trade-off between ecological and cultural values in the Bay of Cádiz Natural Park is particularly evident in the widespread practice of shellfish harvesting, which often occurs in conflict with the legal framework. Despite that, this activity has become culturally embedded and socially accepted due to its strong traditional roots and the absence of effective social transition for workers displaced from low-skilled occupations that no longer exist. The species most frequently targeted include Ruditapes decussatus, Ruditapes philippinarum, Scrobicularia plana, Magallana gigas, and Ostrea edulis. While shellfish harvesting represents an important livelihood strategy for local communities, the lack of implementation of regulations and the disorganized growth of this activity exert significant pressure on local marine resources and undermine conservation efforts in the area. Survey responses and stakeholder dialogs highlighted the complex interplay between ecological degradation and socio-economic dependence on unregulated activities.

Participatory mapping sessions, also facilitated by the SeaSketch tool, were held with an expanded set of stakeholders, including representatives from a private company, a scientific institution, regional and local administrations, representatives from the Ministry, and surveillance services, who were outside the original CoP. Their inclusion was crucial for integrating broader institutional perspectives, improving data accuracy, and fostering interagency coordination. This inclusive approach helped to spatially identify critical areas of overlap between conservation priorities and human activities, while also capturing culturally sensitive practices. The mapping process served to visualize the extent of informal harvesting zones and areas perceived as ecologically vulnerable.

Due to insufficient protection measures and limited enforcement, stakeholders have largely accepted new designations with minimal resistance. The trade-off between ecological and cultural values focuses on the widespread practice of illegal shellfish harvesting, which is culturally accepted despite its ecological impact. A significant issue raised was the lack of effective spatial management and the absence of enforcement of existing regulations. For instance, despite only 25 licenses being issued for shellfish harvesting, it is estimated that more than a thousand individuals operate illegally in the area.

The discussion was guided by specific arguments and proposals. Although the organizers made an effort to address trade-offs based on survey results, participants emphasized the need to take a step back and focus more on governance rather than management.

Consensus was difficult to achieve, particularly on issues like illegal activities, traditional uses, and balancing conservation with development. Despite these challenges, several recommendations were proposed, including the incorporation of traditional and cultural practices within conservation efforts, stressing the need for economic alternatives for those engaged in illegal activities; the improvement of local stakeholders integration in decision-making process, the enhancement of governance structures; the allocation of greater efforts to surveillance and control tasks, especially in the most sensitive zones; and zoning/planning in advance for those military areas that may be decommissioned or repurposed in the future.

Different stakeholders expressed a variety of opinions, many of which were influenced by their specific interests and roles in the Bay. Some emphasized the need for stronger surveillance and stricter enforcement of existing laws to protect the ecological integrity of the area. Others advocated for the inclusion of traditional and cultural practices within conservation efforts, stressing the need for economic alternatives for those engaged in illegal activities. A recurring theme was the importance of integrating these diverse perspectives through enhanced participation and dialog within a flexible and inclusive governance framework. Education and awareness-raising efforts among local communities were also identified as crucial for changing perceptions and fostering compliance with conservation goals.

In addition, there is a need to enhance the governance framework to support future planning initiatives. This includes addressing the shortcomings of previous efforts in the Bay of Cádiz. Understanding why past initiatives have not yielded substantial results is essential to avoid repeating mistakes.

SeaSketch was recognized as a valuable instrument for planning; however, in smaller, highly detailed areas like the Bay of Cádiz, where some stakeholders have “owned” the space traditionally, discussions over a map became very loud. SeaSketch was generally perceived by participants as a useful tool to visualize spatial information and support marine planning. In the Bay of Cádiz, the workshop was intensive, yet the time available was insufficient to comprehensively address the diverse issues raised by participants. Although a substantial amount of spatial information was gathered—reflecting the diversity of sectors represented—participants were reluctant to engage in detailed discussions on specific spatial measures or trade-offs. Instead, discussions gravitated toward governance challenges, particularly the complexity created by overlapping legislation across different governmental levels in the area. This experience suggests that future interactions would benefit from multiple rounds of consultation, possibly through sector-specific sessions or extended discussions, to ensure both governance concerns and spatial measures are adequately addressed. Nevertheless, the methodology fostered critical reflection on institutional failures and the importance of stakeholder inclusion, thereby reinforcing the relevance of participatory governance in addressing socio-ecological trade-offs.

In the North West Mediterranean Case Study, the goal was to discuss how to extend the network of strictly protected areas (SPA) within the Pelagos sanctuary to address marine mammals’ conservation targets, complying with the national goals of France and Italy. The identified trade-offs included conflicts between marine mammals’ conservation and the ongoing development of maritime traffic, as well as between short-term and long-term benefits.

For large cetaceans, the primary threat stems from maritime traffic and the associated risk of collisions. Their protection is a complex challenge, particularly due to the high mobility of individuals and the difficulty of properly locating areas of interest that remain over seasons and years. As a result, conservation measures often involve large spatial areas, which can have significant impacts on maritime activities. The challenge of implementing strong protection for marine mammals has not yet been fully addressed globally, raising questions about the appropriate size of protected areas and the type of measures to apply. Trade-off measures are thus to be found to provide better protection of marine mammals in the area to prevent collision risks.

The identification of critical habitats, such as feeding and breeding grounds, was carried out in collaboration with experts, NGOs, and maritime representatives. Tools and data from international frameworks like IMMAs and the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and contiguous Atlantic area (ACCOBAMS) supported this effort. The mapping process helped localize threats (e.g., collision zones) and contextualize them within broader transboundary dynamics.

Scenarios were co-developed to explore feasible mitigation measures such as traffic deviation and speed reductions. These measures could have substantial economic impacts on the maritime sector, with few arguments in favor of lowering or compensating for these costs. Therefore, economic resistance was noted, particularly from the shipping sector. One potential solution discussed was the implementation of a cetacean presence alert broadcast to enforce mitigation measures only when necessary. Such systems already exist, notably REPCET, and have been implemented for several years by shipping companies in the Mediterranean, particularly within the Pelagos Sanctuary.

To be effective, spatial protections and associated measures should be implemented at a transnational scale. This underlines the complexity of cross-border cooperation. Existing tools such as IMMAs, PSSA, ACCOBAMS, Pelagos Agreements, Natura 2000, and MPAs should be used for proposing different scenarios to protect specific areas based on scientific data or expert knowledge (aggregation areas, critical life-cycle areas such as feeding/foraging or breeding areas) for each species (e.g., the Western Ligurian Sea and Genoa Canyon zone is identified as a high-density area for Cuvier’s beaked whales).

A central challenge is to find viable compromises with maritime stakeholders, who may be reluctant to reduce vessel speeds due to concerns about competitiveness. Investigating how to transition from voluntary measures toward regulatory mechanisms could be an option to reduce impacts on marine mammals in the key areas identified. This case emphasized the added value of embedding participatory processes within existing international agreements to improve legitimacy, scale appropriateness, and long-term effectiveness of spatial conservation strategies.

Gdansk Bay, part of the Baltic Sea, is the Case Study focused on the designation of new MPAs in Gdansk Bay, Poland, with the goal of preserving unique and sensitive habitats. Key proposals include the Long Sandbank, Seagull Sandbank, and the Vistula Lagoon Gateway Marine Sanctuary. These areas aim to protect essential habitats, such as Zostera beds and important migratory bird sites, while addressing potential conflicts with human activities like tourism and fishing.

The primary trade-off identified was between economic activities (especially expanding tourism infrastructure and fishing) and environmental conservation needs. A spatial trade-off is also evident, as high-density tourism zones overlap with protected areas, causing direct conflicts in regions like the inner Puck Bay and the Vistula inlet. A significant issue highlighted was the rising impact of tourism, particularly unregulated tourism expansion in coastal parts of protected areas. This sector’s growth is viewed as a potential threat to ecological balance, with calls for targeted regulations to mitigate its impact. Meanwhile, the economic impact of coastal fisheries is diminishing due to regulatory and generational shifts.

Representatives from regional and local public administration, key transnational governance bodies related to MSP and MPA management, and local actors participated in the mapping process. This step enabled visualization of Zostera beds and migratory bird habitats in conflict with human activity zones, particularly in areas like Puck Bay. Mapping also facilitated the identification of emerging threats, such as unregulated tourism expansion.

Negotiation centered on identifying acceptable conservation boundaries and use restrictions. The discussion was guided by four regional guiding questions, with a primary focus on balancing economic interests and environmental protection within MPAs. These questions directed participants toward identifying conflict areas and discussing sustainable solutions, an important step to ensure that management measures are grounded in local realities, enhancing both legitimacy and long-term compliance.

Participants generally agreed on the importance of Gdansk Bay’s ecological areas, with broad support for creating MPAs to protect sensitive habitats. However, there were differing views on how to balance conservation with economic interests, particularly regarding tourism. Some emphasized stricter regulations on tourism, while others acknowledged the potential economic consequences of reducing activities like coastal fishing. The shift in conflict areas from fisheries to tourism was noted, suggesting a need for updated conservation strategies and policies that account for this change.

Overall, the structured methodology enabled stakeholders to articulate concerns, visualize impacts, and collaboratively shape MPA proposals that balanced ecological needs with evolving economic trends.

For the Bulgarian part of the Black Sea Case Study, the main goal of the trade-off exercise was to support the expansion of MPAs by preserving the valuable mobile species (marine mammals and fish) and sensitive coastal and marine habitats. The case study also accommodates many maritime uses: shipping, fishery, tourism, scuba diving, etc., and it is one of the best ecologically preserved sites to be proposed for the enlargement of existing MPAs, and to be integrated in the revision phase of the national MSP plan. The site is also one of the most promising areas for the development of Offshore Wind Farms (OWF) in the Bulgarian sea waters.

Trade-offs involving marine conservation, economic development, and ecological integrity, exacerbated by limited operational MPA management and fragmented institutional responsibilities, were discussed. Participants drew polygons in surveys indicating areas of human use, which were then examined on dynamic maps to identify conflicts; during participatory mapping—supported by the SeaSketch tool—CoP members explored conflicts between marine activities and MPAs, potential compatible uses for extended MPAs, and the allocation of areas for future OWF development. Climate change issues and the cross-border context of MPAs' coherence and management were also considered.

Despite the importance of MPAs, they still lack operational management plans, and the majority of maritime activities and blue sectors are concentrated onshore. This presents challenges in terms of limited sea space for both existing and emerging sectors, especially given the European Green Deal (EGD) targets on climate change adaptation and Biodiversity Strategy (e.g., development of OWF and 30% protected areas). There is also a need for more thorough and regular research into the behavior of marine mammals offshore, including tracking their food chains.

Structured negotiations addressed key questions about aligning MSP and MPA processes, integrating climate change considerations, and prioritizing cumulative impact management. The process helped clarify trade-off arguments, such as balancing energy transition needs with biodiversity protection. Participants emphasized the need to balance ecosystem conservation with human activities, acknowledging that some activities, such as agriculture, illegal bottom trawling, urbanization, and maritime defense, have a significant negative impact on the environment, leading to habitat destruction and biodiversity loss. There was a shared recognition of the need for better coordination and cooperation among institutions for integrated MSP and MPA management, as well as improved relations between planning measures and management processes (such as MSP, territorial planning, and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive [MSFD]).

Challenges in defining clear trade-off arguments were noticed. Recommendations emphasized the need for balancing among the uses and MPAs as both are in the most crowded onshore areas, developing opportunities for compatibilities and multi-use options among the blue economy sectors and environmental protection, improving planning and management measures, and enhancing alignment of MSFD and MSP processes to better integrate MPAs in MSP, and transnational/cross-border MSP.

The Belgian part of the North Sea Case Study, in support of the EU Biodiversity Strategy’s strict protection targets, proposed locations for marine reserves to be added as part of the revision process of the MSP. The trade-off between actions at different scales was discussed. The limits of looking at the targets from a country-by-country perspective were highlighted—protection targets should be approached on a broader scale. For example, protecting 10% of French waters protects more features than protecting 10% of Belgian waters; however, another CoP member argued that every ecosystem is unique, and Belgian waters host distinct ecological systems not found in French waters.

The trade-off between coastal protection and biodiversity protection was also discussed. Stakeholders engaged in scenario discussions to evaluate potential reserve configurations. One of the proposed locations for a marine reserve is currently a sand extraction site, and due to climate change, demand for sand will increase for coastal protection purposes. Uncertainty around the effectiveness of the marine reserve proposals in protecting and restoring gravel bed features was also raised as a discussion point. One scientist argued that removing pressures in a specific area might not guarantee ecological improvement, as mobile species may still face external pressures beyond the reserve’s boundaries, especially in the busy North Sea.

Diverging views emerged regarding ecological priorities and acceptable trade-offs, particularly when ecological benefits clashed with local recreational or extractive activities. While no full consensus was reached, the process clarified the need for broader-scale ecological planning and supported the use of cross-border strategies. The Belgian case highlighted the strengths and limitations of SeaSketch, particularly in data-rich environments with high stakeholder expectations. It reinforced the importance of planning approaches that address overlapping pressures and extend beyond administrative boundaries to reflect ecosystem realities.

In parallel, this case study also brought attention to pelagic habitats, which face growing pressures from eutrophication, hydrodynamic change, and pollution. Discussions focused on improving spatial protection for pelagic biodiversity using integrative frameworks and emphasized the need to consider dynamic ecosystem features like plankton and larval dispersal in MSP. The participatory approach also highlighted the limitations of conventional 2D mapping for pelagic systems, with suggestions for enhanced tools and data, including transboundary perspectives and the use of immersive technologies.

Cross-site comparison and emerging implications

Stakeholder engagement (CoP and non-CoP participants) emerged as a central pillar in testing the proposed trade-off methodology, revealing varying levels of participation, challenges, and successes. These differences reflected the diversity of regional governance structures, stakeholder dynamics, and planning priorities.

While most participants across the case studies were members of established CoPs, some sites adopted broader engagement strategies. For instance, in the Bay of Cádiz, the deliberate inclusion of additional regional stakeholders—beyond the original CoP—was essential for collecting baseline information, integrating diverse perspectives, and laying the groundwork for future governance frameworks.

Similarly, the Azores and the Belgian North Sea demonstrated a flexible and inclusive approach, incorporating new participants into existing CoPs, which allowed fresh perspectives to enrich discussions and increase the overall representativeness of the process. This proactive engagement helped prevent issues such as limited or inconsistent participation, which were more pronounced in sites that relied solely on pre-established CoP members.

Despite the broader approach, engagement in the Bay of Cádiz exposed deeper governance challenges. The difficulty in reaching consensus was compounded by weak institutional structures and the cultural acceptance of informal practices, such as illegal harvesting, highlighting the need to strengthen governance capacity and institutional trust.

The Belgian North Sea test site showcased advanced stakeholder engagement on technically complex issues, such as pelagic diversity and the designation of marine reserves. In the Northwest Mediterranean, stakeholder input was vital in assessing economic impacts and negotiating the feasibility of transnational cooperation to protect highly mobile marine mammals. The Black Sea case study demonstrated the value of multi-sectoral engagement, with stakeholders from fisheries, energy, and conservation sectors jointly addressing competing uses, such as offshore wind development versus habitat protection. This highlighted the importance of integrated, cross-border maritime spatial planning for resolving intersectoral conflicts.

Finally, in the Baltic Sea, participatory mapping was a successful tool for stimulating stakeholder dialog, supporting the development of new MPA proposals. However, a lack of robust data—particularly concerning tourism impacts—limited more detailed analysis and evidence-based decisions.

Overall, the application of the participatory trade-off methodology enabled meaningful and often innovative engagement across all sites. The use of flexible formats, evolving CoP structures, and context-sensitive facilitation proved critical to navigating trade-offs and promoting transparent, inclusive, and socially legitimate decision-making processes.

Regarding ecosystem services mapping, despite the support received from the University of the Azores (UAc), many case study sites faced significant barriers related to data availability and technical capacity. Spatial datasets required for mapping marine ecosystem services were either scarce or difficult to access. Furthermore, due to project constraints, the support from UAc was only possible relatively late in the process, leaving limited time for adequate implementation. Additionally, the lack of specialized skills in geomatics and GIS among local teams—such as spatial data handling, map interpretation, and ecosystem service modeling—further limited the feasibility of applying the mapping methodology.

Moreover, marine environments pose specific challenges regarding data acquisition. Available datasets often lack sufficient spatial resolution, full geographic coverage, or biophysical detail necessary for accurate ecosystem services mapping. As a result, among all case study sites, only the Baltic Sea site fully employed ecosystem service mapping, utilizing existing geo-referenced data from a prior study. In contrast, the Western Mediterranean site focused on identifying criteria and indicators as a basis for stakeholder discussion and information gathering.

The MSP4BIO project strategically selected six case studies to enable comparative analysis across varying ecological, socio-economic, and governance contexts11. Common goals across case study sites included: 1. Conflict mapping: All sites demonstrated a shared interest in identifying spatial conflicts between human activities and marine conservation objectives. Mapping these tensions is considered a key step toward sustainable spatial planning and effective ecosystem management; 2. Involvement of diverse stakeholders: Each site adopted an inclusive approach to stakeholder engagement, involving regional authorities, NGOs, industry representatives, fishers, and tourism operators. This diversity of perspectives supports a more holistic and participatory decision-making process; 3. Marine conservation objectives: Most case studies pursued conservation goals, either through the establishment of new MPAs, the expansion of existing networks, or through the resolution of user conflicts to enhance ecosystem resilience and management effectiveness.

A range of context-specific goals emerged, each shaped by local challenges and priorities, including the following: 1. Strategic focus in Cadiz: The Cadiz site emphasized strategic objectives, such as placing the MPA on the political agenda, while other sites focus more on operational goals of creating or extending protected areas; 2. Marine Mammal conservation in the Western Mediterranean: This region stood out for its targeted focus on the conservation of marine mammals, particularly in relation to maritime traffic, underscoring the importance of species-specific considerations in spatial planning; 3. Climate change awareness in the Azores: The Azores site highlighted stakeholder perceptions of climate change, reflecting a strong emphasis on long-term environmental impacts; 4. Offshore wind development in the Black Sea: The Bulgarian Black Sea site focused on potential conflicts arising from offshore wind energy projects, highlighting specific considerations related to renewable energy; 5. Pelagic prioritization in the North Sea: The Belgian North Sea case study prioritized different aspects of marine conservation, with one emphasizing the establishment of marine reserves and the other focusing on pelagic biodiversity and habitat management.

For the spatial layers, each case study site was tasked with describing those used for the actual area, the proposed area, and layers related to climate change. The methodological choices varied across sites, reflecting distinct planning priorities and data availability.

Regarding the layers used to define the actual area, three approaches can be identified: one based on participatory methods, another using environmental or ecosystem features, and a third, the use of the marine space via existing layers. Cádiz Bay and the Azores follow the participatory approach; participants were presented with a map and asked to draw areas on SeaSketch. In Cádiz Bay, stakeholders were asked to identify the areas most crucial for the development of their activities. In the Azores, current users were consulted to define both the core areas of their activities and the zones of conflict. The other case study sites follow the second approach, focusing on environmental and ecosystem characteristics. However, the North Sea site relied solely on existing MPA layers for this purpose.

Each case study analyzed the areas of conflict identified by stakeholders within the proposed area. In the NW-Med, a more specific area was defined based on data analyzed using the IMMA criteria.

Climate change was addressed through diverse methodological approaches across the case studies, each tailored to local contexts and objectives. In most cases, the primary focus was on understanding stakeholder perceptions of climate change.

In Cádiz Bay, stakeholders identified the most climate-vulnerable areas (by drawing the areas in a SeaSketch survey) based on four key criteria: risks to populations, infrastructure, economic activities, and environmental conservation. This integrated approach combined local perceptions with a structured assessment of impacts. Stakeholders were also asked to highlight the areas most sensitive to climate change, reinforcing the connection between spatial planning and vulnerability analysis.

In the Azores, the focus was on gathering user perceptions regarding the likelihood of changes due to global warming and their impacts on ecosystem services, with an emphasis on identifying potential mitigation strategies. Participants were asked three guiding questions: “How likely is it that the area will change as a result of global warming?”; “What would be the impact of global warming?”; and “How does global warming affect ecosystem services?”. This structured framing helped stakeholders articulate spatially relevant concerns.

In the North Sea, approaches varied from spatially focused questions on climate change perceptions, where CoP members were asked to represent perceived climate impacts on maps, to broader discussions on the impacts of climate change on pelagic communities, without using spatial data.

In contrast, the NW-Med employed predictive models to map whale foraging areas, using environmental data such as chlorophyll concentration to model climate-induced changes and their effects on species. The Baltic Sea region, however, did not include climate change scenarios due to data limitations, concentrating instead on ecosystem service assessments. In the Black Sea (Bulgaria), there was recognition of the need for a better understanding of climate vulnerability and for new modeling efforts on marine mammal distributions.

These differences reflect the diverse ways in which local data limitations and technical capacities are addressed, as well as the varied needs and priorities of stakeholders involved in MSP processes. SeaSketch emerged as the most commonly used participatory tool, supporting stakeholder engagement by facilitating discussions, capturing perceptions of environmental change, and visualizing spatial data derived from climate models across a range of marine settings.

Trade-off arguments were an essential part of the exercise, with each case study required to describe the arguments used to explore competing objectives. A portfolio of these arguments was used to standardize the terminology and offer a common reference framework across all case studies. While each site presented unique considerations, one key argument was consistent across all: the trade-off between conservation and economic development. This trade-off entails finding an optimal balance between sustainable practices and economic growth while minimizing environmental harm.

The NW-Med and North Sea case study sites emphasized two key trade-off arguments: trade-offs between short-term and long-term benefits and trade-offs between local and regional interests. The trade-off between short-term and long-term benefits involves immediate economic or practical advantages, which may come at the cost of long-term ecological or socio-economic consequences. Regarding the second argument, both sites agree on the importance of considering broader, transnational scales for greater efficiency.

The trade-off between exclusive and shared uses was highlighted by both Cádiz Bay and the Azores. This argument relates to the allocation of marine resources or spaces, where the challenge lies in deciding whether to restrict access to certain groups (exclusive use) or open it up to a wider array of stakeholders (shared use). The difficulty here is in designing policies that reconcile both types of use, ensuring the interests of diverse stakeholders are addressed without compromising sustainability.

The Azores further emphasized the need to account for the specific interests and needs of different stakeholders. As marine spaces serve a variety of purposes, managing competing interests requires careful negotiation and trade-offs. For instance, recreational boating and tourism interests may conflict with conservation goals, prompting the need to regulate and condition access in a way that minimizes adverse impacts on the marine ecosystem.

Cádiz Bay, on the other hand, highlighted the added complexity of trade-offs in regions where illegal activities are prevalent. Although these activities are unauthorized, they are often tacitly accepted and do not immediately appear as conflicts. This complicates the management of marine resources, as the existence of unregulated uses can obscure the true scope of pressures on the environment.

The application of the methodology placed particular emphasis on the use of participatory mapping tools, revealing key strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with its implementation (SWOT). The purpose of this SWOT analysis was not to assess Seasketch but rather to understand barriers to the step of using participatory mapping tools and how to overcome them. As in most cases, the site used Seasketch, and the analysis is focused on that tool as representative. While some case sites focused their review specifically on the selected participatory mapping tool, assessing its potential benefits and limitations within the context of their respective marine planning projects, this approach provided a focused evaluation of the tool’s applicability and effectiveness across various geographic and socio-economic contexts.

One of the key strengths of SeaSketch is its value as a tool for gathering spatial information and structuring discussions on effective area management. It plays a key role in guiding conversations toward actionable outcomes, effectively minimizing circular debates related to area diagnostics. Its hybrid flexibility enables both remote and in-person formats, making it particularly useful in managing fragmented territories and geographically dispersed stakeholders. Furthermore, the tool has proven effective for trade-off analysis at both local and cross-border scales, helping identify critical ecological areas such as nursery and feeding zones, especially pelagic habitats. The methodology, supported by SeaSketch, has been instrumental in fostering productive discussions, especially during in-person events that facilitated the inclusion of new stakeholders. The clarity of the methodology in posing questions has contributed to informed decision-making. Factors such as data availability, leveraging stakeholder knowledge, local area familiarity, and building upon existing research have played a crucial role in the overall success of the approach.

However, weaknesses were identified in sites where SeaSketch was used in small-scale MPAs requiring a high level of detail. In such cases, the tool’s broad planning scope was less well perceived, with stakeholders requiring detailed information that was not available for such scales. CoP members have also expressed a need for additional time to review and discuss SeaSketch results. Additionally, digital literacy gaps, limited availability of quality spatial data, and logistical issues (e.g., travel costs for in-person meetings) hindered full participation and slowed the process.

Mapping trade-offs related to species location and collision risks—particularly for cetaceans—has also proven difficult. Issues such as implementing robust protection measures for cetaceans and determining appropriate area sizes for conservation remain unresolved. Several problems were identified during the survey process, including the inability to consult spatial allocations and the lack of high-quality spatial data, especially in the Bulgarian portion of the Black Sea. These difficulties, alongside challenges for CoP members with limited digital skills, indicate a need for other complementary methods (e.g., paper maps) despite the adaptable features of the tool. A comprehensive framework that includes scenarios and incorporates ecological and socio-economic criteria is essential for effective trade-off analysis. But its full comprehension might be hindered by poor digital skills on the stakeholder’s side.

In the Belgian Part of the North Sea, participants found SeaSketch less appealing, firstly because they already use and are familiar with “The Reef” tool, and also due to existing spatial designations and difficulties visualizing data during the survey. The survey process led to silent periods during workshops, which negatively impacted group dynamics. Technical questions, particularly those requiring socio-economic knowledge, posed challenges, highlighting the need for a more user-friendly interface. The tool’s limited use in the meetings, especially with respect to incorporating uploaded data as base maps, further emphasizes the need for enhanced adaptability. Although SeaSketch can incorporate custom basemaps authored in ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Server, and MapBox, each of which can accommodate custom vector and raster data layers. Additionally, the limitations in capturing the complexity of pelagic systems prompted suggestions for the already existing and used tools, such as “The Reef”, a virtual reality system used for marine training in Ostend, indicating the need for different technological solutions in certain contexts.

On the other hand, SeaSketch offers promising opportunities for strengthening strategic maritime planning. In the Azores, the integration of meetings in fishermen’s communities has enhanced stakeholder involvement, improving surveillance and gaining unanimous support for a proposed MPA at Level VI (IUCN).

Furthermore, SeaSketch has the capacity to integrate both socio-economic and ecological criteria, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of MSP and MPA management. The tool fosters collaboration among authorities and various stakeholders, creating a conducive environment for information exchange and joint decision-making. The tool benefited from stakeholder awareness and easy identification on the map. Its ability to integrate transboundary information and highlight data gaps contributes to informed decision-making, positioning SeaSketch as an instrumental tool for proactive planning and collaboration in diverse maritime environments.

Although the tool was not deemed ideal for spatial planning discussions in the Belgian case study, it was viewed as potentially appropriate for data collection and for applications at smaller scales (e.g., at the harbor level), where users can more easily construct a mental map of the area.

Nonetheless, SeaSketch faces several challenges in the context of weak governance, political inertia, and illegal activities, all of which create a complex environment for effective planning. The role of SeaSketch in this context requires careful consideration to avoid potential misuse (e.g., underrepresented voice) and ensure its continued effectiveness. It may be best utilized at different stages of the management cycle—either supporting early political decisions by highlighting opportunities and conflicts or being employed during later planning stages.

Additionally, logistical challenges such as difficulties in arranging meetings, time constraints, and stakeholder fatigue complicate the implementation of in-person meetings. In some regions, SeaSketch may overlap with ongoing initiatives and may be more relevant at a basin scale. In regions like Bulgaria, the onshore sea space faces overcrowding, limited offshore alternatives, a shortage of trained human resources, and gaps in data related to climate change in MSP and MPA plans. Stakeholder fatigue and the risk of duplicate efforts due to multiple ongoing projects further exacerbate these challenges. Moreover, the complexity of climate change and plankton dynamics is often overlooked, as these topics are perceived as too complex and are hindered by existing knowledge gaps.

Discussion

The implementation of the four-stage participatory trade-off methodology1 across six diverse case study sites demonstrated its adaptability and effectiveness in MSP contexts. Despite each site presenting context-specific challenges, the methodology consistently facilitated the identification, visualization, and negotiation of trade-offs between conservation goals and human activities.

A central strength of the approach lies in its structured yet flexible design, which guided stakeholders through complex decisions in an inclusive and iterative manner without imposing a ‘one size fits all’ solution. Its strong ability to balance methodological consistency with contextual adaptability enhances both the relevance and comparability of results across regions, making the method practical and broadly applicable. The robustness of the methodology was evident, particularly in pilot sites like the Bay of Cádiz and the Azores, where trade-off discussions directly benefited from the sequencing of stakeholder engagement, scenario building, and spatial negotiation.

The three-step process—starting from issue identification, progressing to participatory mapping, and culminating in trade-off negotiation—provided clarity and direction. Participatory mapping, in particular, proved critical for making conflicts tangible and facilitating consensus, especially where competing claims to space (e.g., conservation vs. economic use) required transparent discussion. Importantly, incorporating non-academic critical cartography into spatial planning can enhance the process by bringing in local knowledge, identifying potential social conflicts, and strengthening the legitimacy of decisions through broader stakeholder participation23.

The methodology also surfaced key operational gaps that require refinement, such as limited stakeholder capacity, uneven technical literacy, and fragmented data availability. In response, pilot sites highlighted the importance of early technical training, streamlined basemap preparation, and user-friendly participatory tools (e.g., SeaSketch) to maintain engagement and enhance decision quality.

Several key trade-offs were evident across the six case-study sites. Trade-offs were found to be multi-scalar and deeply context-specific, confirming the premise that no one-size-fits-all solution exists in MSP. This reinforces the need for participatory and adaptive approaches. However, recurring patterns emerged across all six case studies, offering broader insights:

Conservation vs. Economic Development: This underlying tension shaped most trade-off scenarios, reflecting the universal challenge in MSP of balancing environmental sustainability with ongoing socio-economic activities. For example, in the Bay of Cádiz, the conflict between marine conservation and illegal shellfish harvesting underscored the need for better governance, awareness-raising, and stakeholder collaboration. The inclusion of stakeholders in the decision-making process represents a fundamental pillar of good governance, as it not only ensures transparency and legitimacy, but also fosters greater ownership and acceptance of the decisions that emerge from the process24,25. Similarly, in the Black Sea, integrating OWFs with MPA revealed the necessity for spatial and operational management strategies capable of balancing biodiversity conservation with energy development goals. Given the current race to meet the objectives of the European Green Deal and achieve carbon neutrality26, OWFs are becoming increasingly common. Consequently, trade-offs involving OWFs are expected to become more prominent10, highlighting the importance of proactively identifying and negotiating these potential conflicts.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Outcomes: Stakeholders often weighed immediate economic gains against longer-term sustainability1,10,11. In the NW Mediterranean, balancing conservation of marine mammals with maritime traffic highlights the importance of viewing short-term losses through the lens of long-term ecosystem resilience. The Azores offered a positive example where climate change perceptions guided stakeholder-driven long-term planning.

Local vs. Regional/Global Considerations: In the Belgian North Sea, decisions about locations of marine reserves for biodiversity protection required reconciling localized recreational activities with broader ecological goals. This demonstrates the importance of broader-scale coordination to achieve effective biodiversity outcomes, particularly in areas subject to intense, overlapping use. Regionally coordinated approaches offer a valuable framework to address such complexity, enabling countries to align local priorities with shared conservation objectives27.

The analysis of the case studies highlights several key lessons regarding the use of a guided trade-off methodology for MSP. These lessons emphasize the critical role of stakeholder engagement, adaptability to local contexts, and managing the complexity of balancing competing interests. Key insights include:

The methodology’s participatory design, including clear trade-off arguments, workshops, and CoPs, was instrumental in capturing diverse perspectives—from fishers and NGOs to planners and local governments. CoPs can serve as a valuable mechanism to promote greater participation and inclusiveness in MSP, while also facilitating knowledge exchange and strengthening the integration of stakeholder perspectives and concerns into planning processes28.

Participatory mapping enhances scientific understanding while also building trust and collaboration among stakeholders, thereby supporting more inclusive and robust ocean governance23,29. Tools like SeaSketch supported dialog but also revealed shortcomings, such as participation fatigue and uneven access to spatial literacy, as observed in the Belgian and Baltic cases. Improving community of practice models and adopting participatory monitoring approaches can help sustain long-term engagement.

While all sites recognized the need to address climate impacts, the Azores and West Mediterranean made the most explicit efforts to leverage climate models and stakeholder perceptions into spatial planning. This revealed not only the strategic value of aligning MSP with climate adaptation but also the ongoing need for better climate data frameworks. The integration of climate change considerations into conservation strategies is essential, as climate impacts pose a significant threat to biodiversity and ecosystem services, potentially shifting species distributions, altering community structures, and disrupting marine-based economies30,31.

The use of co-developed scenarios enabled sites to move beyond polarized positions and explore mutually acceptable solutions. This was particularly evident in the Azores, where tailored stakeholder dialogs helped balance tourism, conservation, and economic uses. Starting with simpler issues (e.g., in Cádiz Bay) also proved effective in building trust before tackling more complex trade-offs.

A guided methodology helped sites address uncertainties and trade-offs not only between sectors but within sectors (e.g., conservation priorities vs. governance realities). The importance of governance improvements, such as aligning MSP processes with policy frameworks like the MSFD, was repeatedly stressed. In cases like the Baltic and Black Seas, better alignment facilitated resolving cross-border conflicts tied to marine activities.

The findings from this study suggest several critical implications for the future of MSP, both within and beyond the EU. The methodology tested offers a replicable model for negotiating competing claims, co-developing scenarios, and building legitimacy through inclusive spatial planning. This represents a clear opportunity to institutionalize participatory trade-off methodologies as a core component of planning practice. Incorporating tools such as participatory mapping and CoPs into EU guidance could enhance not only stakeholder engagement but also the effectiveness of spatial planning decisions.

In addition, the approach’s adaptability across highly diverse contexts—ranging from small island regions like the Azores to transboundary areas, such as the Baltic Sea—demonstrates its potential transferability to non-EU settings. This is especially relevant for regions facing similar challenges in balancing conservation with development, including the Global South, small island developing states (SIDS), and areas with limited governance capacity. Promoting such methodologies globally could support the implementation of the UN Ocean Decade and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) by embedding social equity and local knowledge into marine planning.

Finally, an effective MSP should create space for transparent negotiation rather than relying solely on technical or expert-driven solutions. This requires investments in capacity-building, accessible participatory tools, and mechanisms to sustain engagement beyond project cycles. Participatory trade-off methodologies offer a pathway to anticipate conflict, build resilience, and align local actions with long-term policy goals. Embedding these methods into MSP frameworks could foster a more integrated, equitable, and forward-looking approach to ocean governance.

Conclusions

The application of a guided trade-off methodology across diverse marine contexts demonstrated the value of participatory, adaptive, and context-sensitive approaches in managing competing objectives within MSP. By combining issue identification, participatory mapping, and trade-off negotiation, the process enabled more transparent decision-making and fostered inclusive dialog among stakeholders. Notably, the methodology was tested in a wide range of socio-ecological and governance settings, proving to be both robust and flexible. This versatility reinforces its potential for broader application across different maritime planning contexts.

While all case sites addressed the trade-off between conservation and economic development, the analysis revealed that trade-offs are deeply influenced by local realities, highlighting the importance of tailored approaches that align with specific socio-ecological and governance contexts of each region.

Participatory mapping tools, particularly SeaSketch, proved highly effective in visualizing spatial conflicts and engaging stakeholders. However, their effectiveness was occasionally constrained by limitations in data availability, scale, and technological capacity, emphasizing the need for more flexible and resource-sensitive tools to support inclusive mapping and negotiation processes.

Importantly, the presence of uncertainties, including climate change impacts and illegal activities, reinforced the need for iterative learning, proactive planning, and adaptive governance frameworks. Future MSP initiatives should embed regular feedback loops, scenario-based thinking, and capacity-building efforts to ensure that planning remains responsive to evolving challenges and inclusive of diverse perspectives.

In light of the forthcoming revision of the EU MSP Directive32, it is recommended that the lessons learned from this study be systematically considered during preparatory discussions. Integrating these insights would strengthen the case for nature-inclusive approaches within the Directive’s future framework.

Ultimately, the study highlights that balancing ecological integrity with human use requires not only robust methodologies but also a genuine commitment to participatory principles and adaptive governance. The tested methodology, proposed by Calado et al.1 offers a structured yet flexible approach for integrating stakeholder perspectives, managing spatial trade-offs, and enhancing the legitimacy of marine planning outcomes. Its adaptability to diverse contexts demonstrates its potential for extrapolation to non-EU territories, supporting the effective integration of participatory approaches into conservation-related aspects of MSP processes globally.

Methods

Case study sites

To thoroughly test the application of the methodology introduced by Calado et al.1 (described in the section “The applied participatory-based trade-off methodology”) in the present study, six diverse case study sites were selected, encompassing all major European sea basins (Fig. 1). The Azores (Portugal) and the Bay of Cádiz (Spain) were included as case studies in the Atlantic, the Belgian case in the North Sea, the Bulgarian case in the Black Sea, Gdansk Bay (Poland) in the Baltic Sea, and the North-West Mediterranean Sea. Collectively, these locations span the broad spectrum of Europe’s ecological and environmental conditions, socio-cultural and economic contexts, varied policy and governance structures, and differing degrees of data availability, effectively capturing the complex realities faced by European marine management (Table 2). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Azores (PARECER 16/2023, approved on 3 March 2023).

Geographical distribution of the MSP4Bio case sites (types of environments and sectors covered) (https://msp4bio.eu/).

The applied participatory-based trade-off methodology

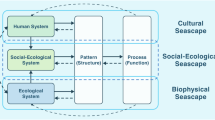

Balancing and reconciling the complex landscape of stakeholders’ needs, objectives, and interests in MSP requires a structured approach to trade-off analysis to ensure efficient and effective decision-making processes. The methodology proposed by Calado et al. 1 provides a clear set of procedural steps and operational guidelines for applying trade-off analysis within MSP and MPA processes. This methodology considers that decision-making processes based on trade-offs can be structured into four sequential ‘building blocks’ (Fig. 2): Know and prepare: The foundational building block upon which all other blocks are implemented. It involves clearly defining goals, thoroughly screening the available biological and human activities data within the area of interest, and developing a comprehensive understanding of local actors directly or indirectly involved and affected by the processes required to achieve the defined goals. Set options: This stage aims to design a set of alternative solutions to achieve the goals established in the initial building block. To do so, the best available science-based knowledge and tools to address ecological and environmental phenomena are implemented. Once identified, these alternative solutions are ranked and adjusted to incorporate future changes in the system of interest (e.g., climate change) and uncertainty in planning. Trade-off negotiation: Building on the previous two blocks, this focuses on presenting, arguing, and negotiating the identified solutions, leveraging participatory strategies. In this phase, negotiation with stakeholders, practitioners, and governmental actors may benefit from drawing inspiration from previously used arguments and successful case studies. Assume, implement, and mainstream: This building block focuses on converting the identified and agreed-upon solutions into practical and achievable steps. It requires policy and decision-makers to take ownership of the solutions and implementation strategy, ensuring their seamless integration into routine actions.

For such a complex decision-making process, the methodology proposed by Calado et al.1 outlines detailed, step-by-step guidelines for effectively developing and implementing the third building block, ‘trade-off negotiation’, in a participatory context. This methodology was applied across the six case study sites through the execution of three primary operational steps: (I) preparation, (II) collaborative engagement with stakeholders, and (III) post-meeting (Fig. 3). For more information, resources, and data sources, please visit the MSP4BIO project website at https://msp4bio.eu/.

(I) Preparation: Based on the conservation goals and solutions defined in the first two building blocks, the preparation step involved identifying, collecting, and harmonizing relevant spatially explicit ecological, environmental, and human activities data. Information on management areas and administrative boundaries was included. In the case study sites, this was achieved through a comprehensive screening of the data collected by national monitoring programs and publicly accessible research-specific datasets. This information was further enriched with data from European data infrastructure repositories, such as EMODnet. When necessary, the collected data were further processed and integrated using specialized models and tools designed to support ecologically and environmentally informed decision-making processes (a technical description of these tools can be found in Cambra et al.33 and Kotta et al.34). These tools were employed to enhance the clarity and usability of the information collected for decision-making purposes.

In association with the collection of relevant spatial data, a comprehensive list of ecological and environmental criteria, socio-economic criteria, and relevant ecosystem services was compiled for each case study site for prioritization in the trade-off analysis. The criteria were defined by applying the conceptual advances, methodologies, and recommendations outlined in Bongiorni et al.35 and Cambra et al.33 for ecological and environmental aspects and Pegorelli et al.36 for socio-economic aspects. The final selection of criteria and ecosystem services was collaboratively established through participatory processes within the CoP formed at each case study site. More than 50 stakeholders were identified and involved in the CoPs. They were chosen for the direct role in test-site planning and biodiversity management, as well as the relevance of MSP4BIO outcomes to their activities, with each CoP comprising MSP and MPA practitioners and other maritime-use management participants (typically 5–10 members)37. Although not initially planned within the scope of the project, an introduction to ecosystem service mapping was provided to all the pilot sites by the UAc in order to further advance the application of the methodology.

During the preparatory phase, a tool for the participatory development of the trade-off analysis was selected for each case study site. A comprehensive overview of available tools and strategies for efficient, context-specific data collection was compiled, drawing in part from Burnett’s38 evaluating participatory mapping software. Case study leaders retained the flexibility to select and adapt the most appropriate tools and approaches based on the overarching process structure and the specific needs of their local contexts.

A crucial step in the preparatory phase involved building a project in a participatory mapping tool. This required the development of a site-specific survey by the designated project lead or official entity responsible for facilitating stakeholder engagement. The survey, designed to address locally relevant issues and priorities, was structured into three interconnected components: Part I—Data collection and perception, Part II—Data analysis and validation, and Part III—Perception of change. In Part I, stakeholders contributed spatial and contextual knowledge through participatory mapping of current uses, conflict areas, and zones with potential for conservation. This phase also explored stakeholders’ priorities and perceived values of ecosystem services. In Part II, the collected data were analyzed and integrated into spatial planning scenarios, which were then discussed and refined collectively. This step included the validation of proposed solutions using tools like the ‘Portfolio of Arguments’ (a list of several trade-off arguments provided in Gutierrez et al.11) and facilitated consensus-building around ecological and socio-economic goals. Finally, Part III focused on future-oriented thinking, assessing stakeholders’ perceptions of environmental change—especially under climate change scenarios—and their implications for the use of ecosystem services and spatial planning. Surveys and mapping tools helped visualize expected impacts and identify adaptation needs.

SeaSketch, a participatory mapping tool, in the case of this study, focused on MPA/MSP processes39, was made available to all partners, along with a two-day training session with the developer (as part of the Azores partner’s work proposal). This, combined with some characteristics of the tool (e.g., ease of use for stakeholders; Fig. 4), led most of the case site leaders to choose this participatory mapping tool.

(II) Collaborative engagement with stakeholders: To ensure the co-development of context-sensitive and widely accepted spatial solutions, the CoP was established in each case study site. These CoPs brought together key local stakeholders—such as maritime spatial planners, MPA managers, NGO representatives, and sectoral actors—who were actively engaged throughout the entire process. The engagement process relied on a structured sequence of interactions, including interviews, focus workshops, and participatory mapping sessions, designed to capture diverse perspectives, generate local data, and validate proposed strategies.

During implementation (Fig. 5), several key steps were followed, including the introduction of trade-offs, ecological values and goals, application of the survey and participatory tool, analysis and decision-making, and documentation phase, all key discussion points were recorded using a standardized template (for further details, see Gutierrez et al.11 and Calado et al.1). Across all phases, transparency, inclusivity, and iterative dialog were central to the methodology. Results were fed back to the CoPs for reflection and refinement. The authors have obtained written consent to publish the images.

(III) Post-meeting: following the stakeholder meetings, a third and final step focused on consolidating the outcomes through post-meeting activities: This included the preparation of a meeting report summarizing key points of discussion, trade-offs identified, and any preliminary agreements reached. Additionally, feedback was provided to stakeholders to ensure transparency and demonstrate how their contributions were considered in the process. This step aimed to reinforce trust, maintain stakeholder engagement, and document the participatory process in a structured and accessible format.

Individual and comparative assessment of trade-off analysis implementation across case study sites

To assess how trade-off analysis was implemented across the case study sites, a qualitative comparative analysis was adopted, considering the contextual characteristics, stakeholder composition of the CoPs, methodological adaptations, and the nature of trade-off arguments developed at each location. Each site engaged in the structured application of a common analytical framework, yet tailored the process to fit local priorities, data availability, and stakeholder capacities (Fig. 6).

A central element of the exercise was the identification and articulation of trade-off arguments based on a shared portfolio of concepts, ensuring a degree of consistency across all sites. This portfolio defined key dimensions—economic, environmental, and social—and provided templates for classifying the competing interests identified during stakeholder engagement processes.

In addition, the Strengths–Weaknesses–Opportunities–Threats (SWOT) analysis was conducted to evaluate the entire methodology, highlighting its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. This approach enabled a focused evaluation of the methodological applicability and its effectiveness in varying geographic and socio-economic contexts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the MSP4BIO project (https://msp4bio.eu/), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the MSP4BIO project.

References

Calado, H., Gutierrez, D. & De Bruyn, A. Navigating trade-offs on conservation: the use of participatory mapping in maritime spatial planning. NPJ Ocean Sustain. 4, 8 (2025).

Ehler, C., Zaucha, J. & Gee, K. Maritime/marine spatial planning at the interface of research and practice. In Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future (eds. Zaucha, J. & Gee, K.) 1–21 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Ehler, C. & Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning, a Step-by-Step Approach towards Ecosystem-Based Management. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and Man and the Biosphere Programme. IOC Manual and Guides No. 53 http://hdl.handle.net/1834/4475 (2009).

Hogg, K., Gray, T., Noguera-Méndez, P., Semitiel-García, M. & Young, S. Interpretations of MPA winners and losers: a case study of the Cabo De Palos-Islas Hormigas Fisheries Reserve. Maritime Stud. 18, 159–171 (2019).

Hogg, K., Markantonatou, V., Noguera-Méndez, P. & Semitiel-García, M. Incentives for good governance: getting the balance right for Port-Cros National Park (Mediterranean Sea, France). Sci. Rep. Port-Cros Natl Park 30, 165–178 (2016).

Lester, S. E. et al. Evaluating tradeoffs among ecosystem services to inform marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 38, 80–89 (2013).

Sala, E. et al. Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature 592, 397–402 (2021).

Gonçalves, E. J. Marine Protected Areas as Tools for Ocean Sustainability. In Blue Planet Law. Sustainable Development Goals Series (eds Garcia, M. d. G. & Cortês, A.) (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24888-7_11.

Boussarie, G., Kopp, D., Lavialle, G., Mouchet, M. & Morfin, M. Marine spatial planning to solve increasing conflicts at sea: a framework for prioritizing offshore windfarms and marine protected areas. J. Environ. Manage. 339, 117857 (2023).

de Queiroz, J. D. G. R., Gutierrez, D. & Calado, H. M. G. P. Trade-offs in marine policy decisions through the lens of literature. Oceans 5, 982–1007 (2024).

Gutierrez, D. et al. Trade-Offs Method for Protection and Restoration in MSP—ESE3 (Deliverable D4.3, WP4 of the MSP4BIO Project, GA No. 101060707). (MSP4BIO Project, 2024).

Brown, C. J. & Mumby, P. J. Trade-offs between fisheries and the conservation of ecosystem function are defined by management strategy. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12, 324–329 (2014).

Villasante, S., Lopes, P. F. M. & Coll, M. The role of marine ecosystem services for human well-being: disentangling synergies and trade-offs at multiple scales. Ecosyst. Serv. 17, 1–4 (2016).

Boudouresque, C., Cadiou, G., Guerin, B., Le Diréach, L. & Robert, P. Is there a negative interaction between biodiversity conservation and artisanal fishing in a Marine Protected Area, the Porto Cros National Park (Mediterranean Sea)?. Trav. Sci. Parc Natl Port-Cros 20, 147–160 (2004).

Fortnam, M., Chaigneau, T., Evans, L. & Bastian, L. Practitioner approaches to trade-off decision-making in marine conservation development. People Nat. 5, 1636–1648 (2023).

Kapoor, A., Fraser, G. S. & Carter, A. Marine conservation versus offshore oil and gas extraction: reconciling an intensifying dilemma in Atlantic Canada. Extr. Ind. Soc. 8, 100978 (2021).

Yates, K. L., Schoeman, D. S. & Klein, C. J. Ocean zoning for conservation, fisheries and marine renewable energy: assessing trade-offs and co-location opportunities. J. Environ. Manage. 152, 201–209 (2015).

Crona, B. et al. Sharing the seas: a review and analysis of ocean sector interactions. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 063005 (2021).

Smythe, T., Bidwell, D., Moore, A., Smith, H. & McCann, J. Beyond the beach: tradeoffs in tourism and recreation at the first offshore wind farm in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70, 101726 (2020).

Zaucha, J. et al. Implementing the EU MSP Directive: current status and lessons learned in 22 EU Member States. Mar. Policy 171, 106425 (2025).

Calado, H., Frazão Santos, C., Quintela, A., Fonseca, C. & Gutierrez, D. The ups and downs of maritime spatial planning in Portugal. Mar. Policy 160, 105984 (2024).