Abstract

Substance use disorder (SUD) is characterized by behaviors of impaired control, physical dependence, social impairments, and risky use, regardless of the substance used—yet no prior work has predicted these behaviors directly. This study of 3476 adults used 15 judgment variables, derived from a picture rating task, with contextual variables to predict the SUD-defining behaviors, recency of four categories of substances being used, and SUD severity. This study achieved up to 83% accuracy and 0.74 AUC ROC for SUD behavior and moderate-high prediction for substance use with a balanced random forest approach, and 84% accuracy for predicting SUD severity. Judgment variable profiles revealed that participants with higher SUD severity are more risk-seeking, less resilient to losses, have more approach behavior, and have less variance in preference. This study argues that distinct constellations of 15 judgment variables yield a scalable system for addiction assessment, which can support research across a broad range of addictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Addiction costs American society approximately more than $700 billion a year1. It involves complex motivational, neurocognitive, and social processes, including destructive behaviors2,3. Most prediction studies of addiction have focused on issues related to specific substances as opposed to the destructive behaviors that generalize across substances and are important constructs for addiction. Addiction is defined by the substance use to alter mentation and a set of destructive behaviors that frame repetitive use of short-term reward with reduced concern for negative consequences. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) defines 11 of these destructive behaviors that can be binned within four categories of behavior regardless of substance used. Successful prediction of these four categories of behavior, regardless of substance used, would identify variables for addiction study that were not substance dependent and assess general processes implicated in addiction.

In current parlance, clinicians discuss substance use disorder (SUD) rather than ‘addiction’, which ranks among the most prevalent health risks in the USA, contributing to significant mortality from overdoses4. SUD is characterized by eleven criteria in the DSM-5 that are grouped into four primary categories related to impaired control, physical dependence, social impairments, and risky use5. The Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS) questionnaire is used in clinical settings to screen for SUD6. It includes temporal substance use questions and questions pertaining to the four DSM-5 categories: (i) Extensive time spent procuring substances or recovering from the effect(s) of substance use, (ii) substance use despite social problems including fights and trouble with other people, (iii) reduced involvement with activities at work, school, home, or social events, and (iv) withdrawal symptoms that can lead to continued substance intake to reduce symptoms6,7. These four categories of DSM-5 criteria capture self-destructive behaviors that are henceforth referred to as “SUD behavior” variables, and the questions related to the type of substance used are referred to as “substance use” variables. Per DSM-5 criterion, the severity of the SUD depends on the number of SUD behaviors identified, regardless of the type of substance being used5,8.

Machine learning efforts with SUD have used large variable sets including electronic health records and extensive demographics (e.g., »100 input variables) from questionnaires9,10,11,12,13,14, clinical data15,16, social media posts17,18, neural measures from MRI19, and/or behavioral data from cognitive tasks20,21,22. These large variable sets add multiple dimensions to the characterization of SUD across study participants, producing higher accuracies and lower unexplained variance to model complex relationships between predictors and outcome variables. Such research yields challenges, including significant computational requirements, prohibitive privacy concerns, lengthy and costly data acquisition, and difficulties with interpreting the meaning of the SUD prediction. The current study sought to bypass these challenges by using a small set of cost-effective cognitive science and survey variables that can be acquired on any personal digital device, accessible by 92% of the US population23 and 85% of the world population24, to predict SUD behaviors and substances used. This study utilized cognitive science variables based on a common feature of SUD, namely impaired judgment resulting from changes to reward and aversion-based preference25,26.

Preferences are reflected in the judgments individuals make to either approach or avoid events in the real world27. Abnormalities in reward/aversion judgment have been linked to both SUD28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 and other mental health conditions that can be comorbid with SUD, like major depressive disorder37,38,39, anxiety40,41, chronic stress41,42,43, and suicidality44,45,46,47. A range of monetary and emotional stimuli tasks have identified specific judgment alterations occurring with SUD: altered value-based decision making28, discounting of delayed rewards29,30, altered sensitivity to rewards31,32, more risk-seeking behavior32,33,36,48, and less engagement in rewarding activities34,35. These alterations represent changes in judgment, leading to changes in psychological well-being.

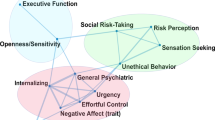

Some of the alterations in judgment observed in SUD appear related to variables that mathematically represent biases in judgment49,50, such as Loss Aversion51 and Risk Aversion52. Recent work has shown that a short 3–4 min picture rating task captures approach and avoidance preferences and can be used to compute a small set of 15 judgment variables53,54,55,56, including analogs for Loss Aversion and Risk Aversion (Fig. 1, Table 1). The methodology to extract judgment variables from ratings is called relative preference theory (RPT) and quantifies how individuals assess value based on their pattern of prior reward and aversion assessments (e.g., a value function), set limits to valuation in the context of uncertainty and risk (e.g., a limit function), and balance positive and negative assessments (e.g., a tradeoff function) (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). The picture rating task in these studies reflects incentive reward as opposed to reinforcement reward. It was adapted from an operant keypress task based on reinforcement reward27,57,58,59,60,61,62,63 so that the task was more easily implementable on a smartphone or digital device (Fig. 1 and Table 1). From a psychological framework, judgment-based preferences reflect ‘liking’ when a rating task is used, versus ‘wanting’ when an operant keypress task is used27,53,54,55,56,64,65, and the judgment precedes an actual decision. This contrasts with an economic perspective where preference can be measured from forced choice data based on decisions (for instance, via axioms of revealed preference, for the preferences revealed by purchases or other measures66). The psychological perspective of judgment has been mapped onto reward circuitry using an operant keypress to regress against fMRI activation58,59,61,62 and morphometric structures60. This psychological perspective on judgment has also been (i) compared to a behavioral economic perspective using a Kahneman task65 to quantify similarities and differences, (ii) integrated with signal detection theory to model mechanisms at the level of behavior63, and (iii) implemented with sound stimuli as opposed to images to model music preferences and show generality across stimulus modalities57. This psychological framework for preference has been shown to meet Feynman's criteria for lawfulness both as an operant keypress (i.e., wanting) task27 and as a rating (i.e., liking) task56.

a An example picture from the picture rating task where participants were asked to rate how much they liked or disliked an image on a scale of −3 (dislike very much) and +3 (like very much), with 0 being neutral. b Visual representation of the x–y plane for relative preference theory (RPT) value function fitting and resulting features extracted. c Visual representation of the x–y plane for RPT limit function fitting and resulting features extracted. d Visual representation of the x–y plane for RPT tradeoff function fitting and resulting features extracted. e Each of the 15 features and their abbreviated terms.

Using machine learning approaches, these 15 judgment variables derived from the picture rating task (based on a psychological framework), along with a small set of contextual variables about demographics and survey questions theorized to affect judgment and mental function67,68,69,70,71, have been shown to predict multiple medical and mental health conditions with high accuracy. These included: depression history72, suicidality54, anxiety55, and vaccine uptake53.

Given these results, this study sought to predict SUD behaviors, along with the recency of substance use and the composite severity of SUD (see Table 2 for the GAIN-SS used herein6), using the same 15 reward/aversion judgment variables (henceforth ‘judgment variables’, Fig. 1, Table 1) derived from the picture rating task. The use of a limited set of mathematical cognitive science variables to predict SUD would contribute to our understanding of how psychological processes underlie the variance in mental health conditions, potentially impacting treatment development and efficacy, and offering a method to study human behaviors not possible with animal models.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Questionnaire responses were collected in December 2021. Participants between 18 and 70 years of age were recruited by Gold Research Inc. (San Antonio, TX) using multiple methods: (1) by invitation only using customer databases from large companies that participate in revenue-sharing agreements, (2) via social media, (3) through direct mail53,54,55,73,74,75. All participants were reimbursed $10 for their participation. Recruited respondents followed a double opt-in consent procedure to participate in the study (see below in the section “Ethical statement”); during this process, they also provided demographic attributes, including age, race, gender, and others. This information was used to ensure that recruited participants represented the U.S. Census at the time of the survey (December 2021). Outside of this information, subjects were fully anonymized before data collection. During the study, respondents were also prompted with repeated test questions to screen out those providing random and illogical responses and/or those showing flatline or speeder behavior. Data from those flagged as non-adherers were removed. To ensure adequate samples of participants with mental health conditions, Gold Research oversampled 15% (60,000/400,000) of the sample for mental health conditions. Gold Research reported that >400,000 respondents were contacted to complete the questionnaire. Gold Research estimated that of the >400,000 participants, >300,000 (75%) either did not respond or declined participation. Of the remaining 25% (100,000/400,000) who clicked on the survey link, >50% did not fully complete the questionnaire. Of the ≥48,000 participants who completed the survey, those who did not clear data integrity assessments were omitted. Participants meeting quality assurance procedures (including survey completion as described in the section “General data exclusion”) were selected, with a limit of 4000–4050 total participants. Eligible participants were required to be between 18 and 70 years of age at the time of the questionnaire, could comprehend the English language, and had access to an electronic device (e.g., laptop, cell phone). Data from 4019 anonymized participants (mean age ± std = 51.4 ± 14.9 years) passed Gold Research’s initial data integrity assessments, were then sent to the research team. Participants provided informed consent as described in the section “Ethical statement”.

Ethical statement

Participation was offered with language noting that Gold Research was administering an emotional health questionnaire on behalf of Northwestern University, with the phrasing: “We will be evaluating how different emotions and experiences are connected and may relate to our emotional health”. All participants provided written informed consent, including their primary participation in the study and the secondary use of their anonymized, de-identified (i.e., all identifying information removed by Gold Research Inc. prior to retrieval by the research group) data in secondary analyses. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for Northwestern University (NU) and the University of Cincinnati (UC) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number STU00213665 for NU and 2023-0164 for UC).

General data exclusion

Gold Research excluded participants using four criteria:(1) participants selected the same response throughout any section of the questionnaire (e.g., selecting option “1” for all questions), (2) participants indicated they had ten or more clinician-diagnosed illnesses out of a possible 17 (data not described here), (3) if the answers for education level and years of education did not match, and (4) if they completed the questionnaire in less than 800 seconds. After filtering for these criteria, Gold Research provided the research team with data from 4019 participants. These data were further screened using responses from the picture rating task. These procedures have been adapted from Stefanopoulos et al. (2024)56, and are detailed under the section “Data filtering based on picture rating task”. In short, participants were excluded if there was minimal variance in picture ratings (i.e., all pictures were rated the same or varied only by one point), the quantitative feature set derived from the picture rating task was incomplete, and/or there were extreme outliers (see section “Judgment variables from picture rating task”). Using these stringent exclusion criteria, data from 3476 participants were cleared for statistical analyses. The remaining 3476 participants had complete data (no missing values) for all the variables involved in this study.

Survey questionnaires and scoring for contextual variables

Participants completed the survey using the online platform provided by Gold Research, Inc. Participants were asked to self-report (a) demographics that have relationships with brain function and behavior58,76,77 including age, gender assigned at birth (sex), annual household income (income), marital status (marital), employment status (employment), level of education (edu), number of years of education (edu_years), ethnicity (race), (b) two COVID-19 questions: (i) if the participant had ever tested positive for COVID-19 (test) and (ii) if the participant was ever diagnosed by a clinician with COVID-19 (diagnosis) and (c) mental health questionnaires. The complete text regarding these questions is listed below:

Age:

Please indicate your age (scroll bar response with integer years).

Sex:

Are you…(gender assigned at birth):

-

1.

Male

-

2.

Female

-

3.

Other or Prefer Not to Answer

Income:

Which of the following best reflects your annual household income?

-

1.

Under $25,000

-

2.

$25,000 but <$50,000

-

3.

$50,000 but <$75,000

-

4.

$75,000 but <$100,000

-

5.

$100,000 but <$150,000

-

6.

$150,000 but <$300,000

-

7.

$300,000 or more

Marital:

Which of the following best describes your marital status?

-

1.

Single

-

2.

Married

-

3.

Divorced

-

4.

Separated

-

5.

Widowed

-

6.

Living with a partner

-

7.

I prefer not to answer this question

Employment:

Please describe your current employment situation…?

-

1.

Unemployed

-

2.

Full-time employment

-

3.

Part-time employment

-

4.

Self-employed

-

5.

More than one job

-

6.

Retired 7. Other

There are two pieces of information asked for in the following question. Select the highest level of education you have achieved, and enter the total number of years you completed below.

Edu:

Please select the highest level of education you have achieved:

-

1.

Some High School. Enter a number between 8 and 12 below

-

2.

High School Graduate. Enter a number between 11 and 14 below

-

3.

Some College. Enter a number between 13 and 16 below

-

4.

Bachelor Degree. Enter a number between 15 and 17 below

-

5.

Some Graduate School. Enter a number between 15 and 21 below

-

6.

Graduate Degree. Enter a number 18 or greater below

-

7.

Post-Doctoral Training. Enter a number >18 below

Edu_years:

Please indicate the total number of years of education you completed (scroll bar response with integer years).

Race:

Do you consider yourself…(select only one response)

-

1.

White

-

2.

African American

-

3.

Hispanic

-

4.

Asian or Pacific Islander

-

5.

Native American or Alaskan Native

-

6.

Mixed Racial Background

-

7.

Other Race

-

8.

Prefer Not To Answer

Test:

Have you ever tested positive for COVID-19? Y/N

Diagnosis:

Have you ever been diagnosed with COVID-19 by a medical clinician? Y/N

Following data filtering as described above and elsewhere53,54,55,73,74,75, the 3476 participants were categorized as predominately female (61.5%), married (51.4%), white (85.7%), employed full-time (35.8%) with some college education (29.6%), and on average older (mean age = 51 years) (see Table S6 for a complete summary).

This study used anxiety and depression along with demographics and picture rating-derived variables (described below) to assess substance use, SUD behaviors, and composite severity. Anxiety was queried using the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) questionnaire, which is commonly used to measure trait and state anxiety78 in clinical settings. Only the 20-state anxiety (STAI-S) questions were deployed in the online survey of this study. Participants were instructed to answer each question based on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Moderately so; 4 = Very much so) based on how they feel right now, that is, at the time of the survey. The questions were scored following the instructions in the score key for the form Y-1 of STAI (https://oml.eular.org/sysModules/obxOml/docs/ID_150/State-Trait-Anxiety-Inventory.pdf). The scored sum of STAI-S ranged from 20 to 80 and is hereafter referred to as ‘STAI score’ and/or ‘anxiety score’.

The patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)79 was used in this study to quantify depression. PHQ-9 is a multipurpose instrument for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression in clinical settings79,80,81. PHQ-979 consists of nine questions, which were answered by the participants based on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Not at all; 1 = Several Days; 2 = More than half the days; 3 = Nearly Every Day) based on how often they were bothered by the problems in the past two weeks. The scored sum of PHQ-9 ranged from 0 to 27 and is hereafter referred to as ‘PHQ score’ and/or ‘depression score’.

The response set to demographics, COVID-19 variables, and anxiety and depression scores is referred to as ‘contextual variables’ hereafter.

Substance use and substance use disorder (SUD) behavior questionnaire

The Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS) questionnaire (Chestnut Health Systems, Bloomington, IL) has been validated to pinpoint diagnostic criteria for (1) externalizing and internalizing mental health disorders, (2) substance use (including alcohol use) disorder, and (3) crime and violence disorders in both adolescents and adults6,82,83,84,85,86. It is used in clinical settings to screen for behavioral health disorders, including substance use disorders87,88,89,90. In this study, we adapted the five questions from the GAIN-SS substance disorder screener (version 3.0). The first question from the GAIN-SS substance disorder screener6 was broken down into four questions to separate out alcohol and substance (cannabis, opioid, and stimulant) use. The first four questions are referred to as ‘substance use variables’ and the last four questions are referred to as ‘SUD behavior variables’. These eight questions, along with their abbreviations, are listed in Table 2. The four SUD behavior questions cover the four criterion categories defined by DSM-5 for SUD, independent of the substance being used. Each of these questions in this study asks when the participants last experienced a behavior based on the time blocks: 0 = Never; 1 = 1+ years ago; 2 = 4–12 months ago; 3 = 2–3 months ago; 4 = In the past month. This study analyzed each question separately, in addition to the total score, against contextual and picture-rating derived (see below) variables. The total score was computed by counting the number of responses from the past one year; the responses ‘Never’ and ‘1+year ago’ were not included in the scoring. For all the substance use questions (alcohol, cannabis, opioid and stimulant use) one or more than one response from the past one year (responses: “2”, “3” or “4”) was given as a count of 1, i.e. the maximum score for the four substance use questions was 1. For the rest of the SUD behavior questions, the responses from the past one year (responses: “2”, “3”, and “4”) were counted and added to the final score. The total score could range from 0 to 5, where 0 reflects no recent substance use or SUD behaviors and the total scores of 1–5 reflect substance use and/or SUD behaviors in the past one year. The total GAIN-SS score is referred to as composite severity.

Picture rating task

Participants were shown 48 (two sets of 24 pictures with survey questions in between the two sets) unique color images from the International Affective Picture System IAPS91,92. Six picture categories were used: (1) sports, (2) disasters, (3) cute animals, (4) aggressive animals,(5) nature (beach vs. mountains), and (6) men and women in bathing suits, with eight pictures per category (48 pictures in total, a sample image is shown in Fig. 1a), with all pictures in a category having similar published calibration. These images act as mildly emotional stimuli91,92 that are employed to assess both positive and negative value (i.e., reward or liking vs. aversion or disliking) and have been broadly used and validated in research of human emotion, attention, and preference. Images were displayed on participants’ personal devices with a maximum size of 1024 × 768 pixels. Below each picture was a rating scale from −3 (dislike very much) to +3 (like very much), where 0 indicated a neutral point (Fig. 1a). While there was no time limit for selecting a picture rating, participants were asked in the instructions to rate the images as quickly as possible and to use their first impression. Once a rating was selected, the next image was displayed.

The instructions displayed before the start of the picture rating task in the survey were as follows:

“The next part of this survey involves looking at pictures and then responding how much you like or dislike the image. Please rate each image on a scale from −3 (Dislike Very Much) to +3 (Like Very Much). Zero(0) is neutral… meaning you have no feelings either way. The images are a set of photographs that have been used by scientists around the world for over 20 years. It is important you rate each picture based on your initial emotional response. There are no right or wrong answers… just respond with your feelings, and rate the pictures very quickly. Use the drop down box to select rating between −3 and 3”.

Judgment variables derived from a picture rating task

Data from the picture rating task were analyzed using a computational framework to characterize preference judgments. Referred to as relative preference theory (RPT)27,57,63, this framework has been adapted to derive judgment features from picture ratings as opposed56,72 to operant keypressing27,58,59,61,62,63,93. For each participant, picture ratings from each of the six image categories were split into two sets—positive and negative ratings. For each of these two sets, and for all six categories, the mean, Shannon entropy27,94, and variance were calculated. The Shannon entropy originates from information theory and characterizes the degree of uncertainty across a set of responses27,94. It quantifies the pattern of judgments made about items in each set of pictures. This yielded \(\left({{\boldsymbol{K}}}^{+},{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}^{+},{{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{+}\right)\) for the positive ratings and \(\left({{\boldsymbol{K}}}^{-},{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}^{-},{{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{-}\right)\) for the negative ratings for all six categories and resulted in a total of 36 \(\left({\boldsymbol{K}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma }},{\boldsymbol{H}}\right)\) variables. It should be noted that for the computation of H, data were screened for cases where K = 0 for a given category (i.e., cases where the subject made all neutral ratings to neither approach nor to avoid any picture in a given category). Computation of H for a given picture category requires that be K > 0 given that H computation results in an undefinable log10(0/0) when K = 0. In such cases, H was set to 0 for categories in which the subject rated “0” for all the stimuli.

These 36 \(\left({\boldsymbol{K}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma }},{\boldsymbol{H}}\right)\) variables were then used to graph three separate curves for value, limit, and tradeoff functions (see Fig. 1b–d) were plotted using MATLAB and the library polyfit, following other publications27,56,57,58,63 for each participant. This framework has been described and validated in previous work27,56 with demonstrated relationships to brain circuitry58,62 and psychiatric illness, as well as predictive capabilities in the context of mental health disorders54,55 and complex decisions53. This framework has been shown to be lawful in that it is mathematically discrete, recurrent, robust, and scalable27,56,63. Representative curves from 500 randomly selected participants out of the 3476 cohort are shown in Fig. S1. Goodness of fit for these functions is described below and summarized in Table S7 and Fig. S1.

Three frameworks were used to mathematically plot the positive and negative components of K, H, and σ (Fig. 1). A value function was fit with either logarithmic or power law frameworks using K and H terms, for positive and negative values separately. A limit function was fit as a quadratic function using K and σ terms, for positive and negative values separately. A tradeoff function was fit as a radial function, using H+ and H− terms. These models were first fit at the group level to inform fitting at the individual level. Participants were excluded if individual curve fits were not consistent (i.e., same direction) with group-level fittings. The RPT framework fits reward/aversion curves and derives mathematical features from these graphical plots that are psychologically interpretable, scalable, recurrent, and discrete27,56,63. At least 15 variables can be extracted from this framework51,52,56 (Fig. 1b–d, Table 1). Each variable describes a quantitative component of the reward/aversion processing involved with judgment behavior. The term ‘judgment variables’ will be used hereafter in reference to these features. Summary statistics for all 15 judgment variables obtained from all participants are reported elsewhere53,54,55,56 and summarized in Table S7B. These variables are described below in psychological terms and organized relative to the curve from which they were extracted:

(1) The (K, H) curve, which consists of (K+, H +) on the positive x-axis and (K−, H−) on the negative x-axis is analogous to the value function from Kahneman’s Prospect Theory. The features that were extracted from this curve include: Loss Aversion (LA), Risk Aversion (RA), Loss Resilience (LR), Ante and Insurance.

Loss Aversion (LA)

Loss aversion was computed as the absolute value of the ratio of the linear regression slope of (log K−, log H−) to the linear regression slope of (log K+, log H+). It intuitively measures the degree to which one overweighs losses relative to gains and is a fundamental measure in Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory, although it uses different variables. Studies of monetary gambles in a Kahneman-designed game of chance show similar values for Loss Aversion during uncertainty as an operant keypress task reflecting reinforcement reward65. In this study, we used a rating task sans uncertainty, so it is not directly comparable to a keypress task or monetary gambles.

Risk Aversion (RA)

Risk aversion is extracted as the ratio of the second derivative of the (K+, H+) curve to its first derivative, which itself produces a curve. To produce a unitary value for prediction, we calculated Risk Aversion at K+ = 1.5. Informally, RA measures the degree to which an individual prefers a likely reward in comparison to a better but more uncertain reward. RA is a common notion in economics that studies decision-making under uncertainty.

Loss Resilience (LR)

Loss resilience is defined to be the absolute value of the ratio of the second derivative of the (K−, H−) curve to its first derivative, which also produces a curve. For prediction, we calculated LR at K− = −1.5. Informally, loss resilience is the degree to which an individual prefers to lose a small, defined amount in comparison to losing a greater amount with more uncertainty associated with this loss.

Ante

Ante is the value of K+ when setting H+ = 0. It intuitively measures the stake one needs to engage in a game of chance and models the amount of a bid an individual is willing to make to enter a game of chance like poker.

Insurance

Insurance is the value of K− when setting H− = 0. It intuitively measures how much insurance an individual might need against bad outcomes. It mirrors the ante, but in the framework of potential losses.

(2) The (K,\({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)) curve, which consists of (K+, \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)+) on the positive x-axis and (K−, \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)−) on the negative x-axis is analogous to the mean-variance curve derived from portfolio theory95. It calibrates preference magnitude (i.e., K) relative to the variance in rewards and sanctions. The (K, \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)) curve models the following question: Would an individual prefer a dollar with probability one, or a value drawn from a normal distribution with a mean of two and variance of two? The features that are extracted from this curve include: Peak Positive and Negative Risk, Reward and Aversion Tipping Point, and Total Reward and Aversion Risk.

Peak Positive Risk (Peak PR)

The peak positive risk is the value of \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)+ where the derivative dσ+/dK+ is equal to zero. Intuitively, this represents maximum variance for approach behavior. It models where increases in positive value transition from a relationship with increases in risk to a relationship with decreases in risk. Markowitz described decision utility as dU = K−b\({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)95\(,\) so Peak PR models when variance changes from potentially weighing against a decision to facilitating a decision.

Peak Negative Risk (Peak NR)

The peak negative risk is the value of \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)−, where the derivative d\({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)−/dK− is equal to zero. Intuitively, this represents the maximum variance for avoidance behavior. Like with the peak positive risk, this transition point is important to consider for avoidance decisions in the context of Markowitz’s decision utility95.

Reward Tipping Point (Reward TP)

The reward tipping point is the value of K+ where the derivative d\({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)+/dK+ is equal to zero. Intuitively, this represents the rating intensity with maximum variance for approach behavior, and signals the amount of reward needed before an individual potentially decides to approach a goal-object.

Aversion Tipping Point (Aversion TP)

The aversion tipping point is the value of K− where the derivative d\({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)−/dK− is equal to zero. Intuitively, this represents the rating intensity with maximum variance for avoidance behavior, and signals the amount of aversive value needed before an individual potentially decides to avoid a goal-object.

Total Reward Risk (Total RR)

The total reward risk is the area under the curve on the positive quadrant of the graph of (K+, \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)+). Intuitively, this variable represents the relationship between K+ and \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)+ and can be thought of as a quantity that measures the amount of value one overall associates with positive stimuli.

Total Aversion Risk (Total AR)

The total aversion risk is the area under the curve on the negative quadrant of the graph of (K−, \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)−). Intuitively, this variable represents the relationship between K− and \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\)− and can be thought of as a quantity that measures the amount of value one overall associates with negative stimulus.

(3) The (H+, H−) curve allows the comparison of patterns in approach and avoidance judgments. The RPT Features that are extracted from this curve include: Reward-Aversion tradeoff, Tradeoff Range, Reward-Aversion Consistency and Consistency Range.

Reward-Aversion tradeoff (RA tradeoff)

The reward-aversion tradeoff is the mean of the polar angles of the points in the (H+, H−) plane. Intuitively, this measures the mean ratio of entropies or patterns in the approach to avoidance behavior.

Tradeoff range

This is the standard deviation of the polar angles of the points in the (H+, H−) plane. Intuitively, this measures the standard deviation in the patterns of approach and avoidance behavior. This variance represents the spread for positive preferences and negative preferences across a set of potential goal-objects and is one measure of the breadth of an individual’s (or group’s) preferences.

Reward-Aversion consistency (RA consistency)

The reward-aversion consistency measures the mean of the distances of the data points in the (H+, H−) curve to the origin. Intuitively, this defines how individuals can have strong preferences (i.e., biases) for the same thing, reflecting conflict, or have low preferences for something, reflecting indifference. This gets at the consistency or compatibility of approach and avoidance, and how you can both like and dislike something, or be indifferent to both its positive and negative features.

Consistency range

The consistency range measures the standard deviation of the distances of the data points in the (H+, H−) plane to the origin. Intuitively, this measures how the points in the H+H− plane vary with radial distance from the origin. The variance in this radial distance will reflect how much an individual goes between having conflicting preferences and having indifferent ones.

Goodness of fit

Goodness of fit for these functions was assessed by computing \({R}^{2}\) values, adjusted \({R}^{2}\) values (accounting for degrees of freedom), and \(F\)-statistics for each participant’s model fit (Table S7A). Individual participants’ \(\left({\boldsymbol{K}},{\boldsymbol{H}}\right)\) value functions were fit by concave logarithmic, or power-law functions (Table S7, Fig. S1). \({R}^{2}\) values ranged from 0.85 to 0.94 for logarithmic fits of the value function, which was considered very high. Concave quadratic fits across individual participants’ \(\left({\boldsymbol{K}},{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\right)\) data are displayed in Fig. S1, and goodness of fit is assessed using the same metrics as with the \(\left({\boldsymbol{K}},{\boldsymbol{H}}\right)\) data (Table S7A). All \({R}^{2}\) values for the quadratic fits exceeded 0.80 and ranged from 0.84 to 0.96. Lastly, radial functions were fit to test for trade-offs in the distribution of \({{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{-}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{+}\) values across categories for each individual participant. Figure S1 displays radial fits across individual participants’ \(\left({{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{+},{{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{-}\right)\) and \(\left({{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{+},{{\boldsymbol{H}}}^{-}\right)\) data points for a random sample of participants.

Data filtering based on picture rating task

-

1.

For fitting models to participants’ ratings, data were further screened for inclusion/exclusion criteria as follows53,54,55: Valid entropy (H) calculations (as described above),

-

2.

Exclusion of extreme outliers in the variables extracted from the graphs as follows: loss aversion values > 200 (resulting in N = 42 exclusions) and positive quadratic area > 100 (resulting in N = 5 exclusions).

-

3.

At least three points for a non-linear fit, or sufficient data points to fit the model with a computable R2.

-

4.

Consistency of individual and group models. This last criterion meant that the curve concavity for individual subject fits be consistent with the curve concavity of the group-level fits (and boundary envelopes).

Criteria (3) and (4) are important operational definitions since there is a potential for convergence failures with curve fitting. These exclusions resulted in the removal of 543 from the initial cohort of 4019, and 3476 participants out of 4019 met all quality assurance criteria for picture rating data and survey data.

Prediction analysis

All analyses were performed in R. Judgment and contextual variables (including demographics, COVID-19, and mental health questions) were used in the prediction analyses. The responses from each GAIN-SS question were divided into two classes recent and not-recent, where recent included the responses from the past one year (responses: 2, 3, and 4) and not-recent responses included never and more than a year ago (responses: 0 and 1). Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and Balanced Random Forest (BRF) analyses were used to classify recent versus not-recent substance use and SUD behaviors for each of the eight questions and to classify the total score into high and low classes. The total score was divided into high and low classes based on threshold values of 1–5. All values below a given threshold were labeled as ‘low’, and values above and equal to the threshold were labeled as ‘high’.

Data were divided into train and test sets with a 70%:30% ratio. Logistic Regression (LR) was implemented using the command ‘glm’ from the open-access package ‘stats’ in R. To predict the class of the data points in the test set, ‘predict’ from the package ‘stats’ was used to get the estimated predicted probabilities of the data points from the fitted model.

Data were divided into train and test sets with a 70:30% ratio for Random Forest (RF) and Balanced Random Forest (BRF) analyses. RF and BRF approaches were implemented using the command ‘randomForest’ from the open-access package ‘randomForest’ in R. The number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split was 5, and the number of trees grown was 1000. No hyperparameter tuning was performed. The BRF performs random down-sampling of the majority class at each bootstrap sample to match the number of samples in the majority and minority classes for training the model. The BRF approach was used in addition to the standard RF analysis because of the greater class imbalance of recent vs. not-recent and high vs. low when the threshold for total score was 2–5 (e.g., the high class occupied only 8.54% and 6.24% of the dataset for threshold values of 2 and 3, respectively). Note that BRF only performs down-sampling while training the model and once the model is trained, calculates the prediction metrics on the complete imbalanced train and test sets.

For LR, RF, and BRF, out-of-bag (OOB) accuracy was reported for the training set. The model was then tested with the imbalanced test dataset, and the prediction metrics of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC ROC (area under the receiving operating characteristic curve), Balanced Accuracy (mean of sensitivity and specificity), PPV (positive predictive value), and NPV (negative predictive value) were reported for the test set. Here, ‘recent/high’ was considered as the positive class. For each analysis, percentages of the data points for each class relative to the entire dataset were also reported. The entire procedure was repeated for each question and each threshold value (i.e., 1–5) for the total score.

BRF analyses were re-run with the above procedure, omitting the mental health variables as predictors and using only judgment and demographic variables as the predictors.

A more generalized procedure, using the entire dataset, with 10-fold cross-validation with 10 repeats, was also implemented for all BRF analyses independently. This set of prediction analyses was performed in Python (version 3.12.1) using the open-source packages ‘imblearn’ (version 0.12) and ‘sklearn’ (version 1.4.1) for cross-validation. The BRF approach was trained on the Gini criterion with no maximum tree depth, so nodes were expanded until leaves were pure or contained at most one sample. In the BRF approach, an ensemble of 100 trees was constructed, where each bootstrap sample was randomly down-sampled to create a balanced dataset of both classes (that is, 50% of positive and 50% of negative data). The sampling strategy used was ‘majority’. Balancing was used for training only, and not for testing within cross-validation. No hyperparameter tuning was performed. The entire dataset was used for the cross-validation approach. Ten-fold cross-validation was repeated 10 times, and the average output metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC ROC (area under the receiving operating characteristic curve), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were reported for all analyses.

Relative importance of features

The relative importance of features was calculated for the best-performing algorithm out of LR, RF, or BRF analyses based on prediction metrics. Relative importance of the features was computed using the commands ‘varImpPlot’ and ‘importance’ from the open-access package ‘randomForest’ in R. The judgment and contextual variables were sorted based on the mean decrease in Gini scores and were plotted by decreasing feature importance, with the most important features appearing at the top of the plot. Gini score is a fundamental outcome of the random forest algorithms, as it shows for each feature how large the discriminative value is for separating the data points into different classes. That is, how important was each variable in the classification, or how much was the uncertainty reduced in the model, leading to accurate predictions. The higher the mean decrease Gini score, the more important the feature was for the classification. The relative importance of the features was analyzed by normalizing the Gini score of each feature to the sum of all Gini scores. This gives the relative proportion of the importance for each feature, with the sum for all features being 1.

Post-hoc analysis: Judgment variable differences

Judgment variables were divided into two groups corresponding to (i) recent and not-recent responses to each substance use and SUD behavior question and (ii) high and low for the best performing threshold for composite severity. These groups were tested for differences in the distribution medians using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (significance level, α < 0.05). If the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test exhibited significant differences, the groups for judgment variables were then tested for the direction in location shift using a one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (significance level, α < 0.05). p-values for both the tests and the direction of location shift of the judgment variable distribution median for the recent/high group relative to the not-recent/low group were reported. Direction indicated if the judgment variable median was greater or lower for the participants in the recent/high as compared to the non-recent/low group.

Results

Adults (ages 18–70) were recruited for this study in December 2021 from across the United States. After quality assurance (see the “Methods” section), the response data from 3476 participants included: (i) eight demographic variables, (ii) two variables regarding past COVID-19 infection, (iii) two mental health variables including depression and anxiety scores computed from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)79 and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)78, respectively, (iv) 15 judgment variables computed from a simple picture rating task, and (v) SUD behaviors including alcohol and three categories of substance use, computed from the ‘substance disorder screener’ of the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS) questionnaire6. Variables (i)–(iii) are hereafter referred to as contextual variables, as done in other publications54,55. Three machine learning algorithms, Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and Balanced Random Forest (BRF) were used to perform three types of prediction analyses using variables from (i)–(iv). These three prediction analyses categorized: (a) ‘recency’: recent vs. not-recent responses for four individual substance use questions (see questions #1–4 in Table 2), (b) ‘recency’ responses for four SUD behavior questions (see questions #5–8 in Table 2), and (c) composite severity: high vs. low for total scores based on threshold values of 1–5 for the composite GAIN-SS survey scores. For (a) and (b) in the recency prediction analysis, individual question responses from the past year were labeled as recent, and responses from ‘more than a year ago’ or ‘never’ were labeled as not-recent. For (c) the composite severity prediction analysis, the total score was computed by counting the number of responses from the past year for all individual questions, once the substance use variables had been consolidated into one variable as done in the standard GAIN-SS survey (see the “Methods” section). Composite severity was based on the presence/absence of the four SUD behaviors and the presence of at least one substance used. Participants were labeled as high and low using threshold values of 1-5; values below a threshold were labeled as low, and values above and equal to the threshold were labeled as high. Given BRF outperformed LR and RF for prediction metrics like sensitivity and balanced accuracy and had the highest values of AUC ROC, results from LR and RF are placed in Supplemental Material (Tables S1 and S2). Gini scores from BRF analyses were used to identify the importance of features used for prediction. Judgment variables were further assessed for differences between recent and not-recent groups. Going forward, the recent vs not-recent prediction analyses for questions #1–4 (please see numbering in Table 2) are hereafter referred to as ‘substance use’ and for questions #5–8 as ‘SUD behavior’. Given the ordering of questions in the GAIN-SS, we present results going forward for ‘substance use’ first and ‘SUD behavior’ second, even though the primary focus of this paper is the prediction of SUD behavior. The high vs. low analyses for the total GAIN-SS score are hereafter referred to as ‘composite severity’. To assess the relative effects of mental health variables on prediction, BRF analyses were repeated without mental health variables (PHQ-9 and STAI) as predictors. BRF was also re-run with a more generalized 10-fold cross-validation approach for the confirmation of prediction results.

Prediction analysis for substance use and SUD behavior

For substance use, prediction results were different for cannabis, opioids, and stimulants in comparison to alcohol. For questions regarding cannabis, opioid, and stimulant use, out of bag (OOB) accuracy ranged from 77% to 84%, and accuracy ranged from 77% to 82%, AUC ROC ranged from 0.69 to 0.74, sensitivity ranged from 55% to 65%, PPV ranged from 17% to 32% and specificity and NPV were high (81%–84%; 92%–98% respectively) (Table 3A). Alcohol use prediction performed poorly relative to other substance use questions, with alcohol metrics lower by 16–23% compared to them.

BRF performed better with higher values for all prediction metrics of SUD behavior as compared to substance use. The out-of-bag (OOB) accuracy ranged from 82% to 83%, accuracy ranged from 81% to 83%, and AUC ROC ranged from 0.72 to 0.74 (Table 3A). Sensitivity values ranged from 61% to 64% with high specificity values between 83% and 84%. PPV ranged from 17% to 22% and NPV ranged between 97% and 98%.

Despite a greater class imbalance between recent vs not-recent classes for questions #2–8 (please see Table 2 for question numbering as shown in the ‘Percentage of data’ column), moderate sensitivity values of 58–65% were observed. The lowest performance metrics were observed for alcohol use with a 42% sensitivity and 61% accuracy (Table 3A).

BRF analyses without the mental health predictors (PHQ-9/depression score and STAI/anxiety score) produced comparable results to above with accuracies ranging 60–83% and AUC ROC 0.54–0.76 for substance use and SUD behavior questions (see Table S8A).

BRF analyses with 10-fold cross-validation provided prediction metrics close to the train/test technique with more robust AUC ROC values ranging from 0.61 to 0.85 for substance use questions and AUC ROC values between 0.83 and 0.86 for SUD behavior questions and accuracies ranging between 58% and 76% (see Table S9A).

Prediction analysis for composite severity

The OOB accuracy and accuracy ranged from 59% to 84% and with an AUC ROC of 0.58–0.75 for the classification of high vs. low for composite severity (Table 3B), depending on the threshold. For thresholds of two and above, accuracy was always above 80% and AUROC above 0.70. A clear class imbalance was noted for thresholds of two and above, as depicted in the ‘Percentage of data’ column of Table 3B, yet this imbalance did not affect prediction results and produced moderate to high sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV metrics. With a threshold of five, only 3% of participants were in the high group (i.e., those indicating five or more substance use behaviors), resulting in a sensitivity of 64.5%. The best classification performance was achieved with a threshold value of four (accuracy 84%, sensitivity 65%, specificity 85%, AUC ROC 0.75, PPV 19% and NPV 98%).

BRF analyses without the mental health predictors (PHQ-9/depression score and STAI/anxiety score) also produced high accuracies (78–81%) and high AUC ROC values (0.68–0.72) for thresholds two and above (Table S8B).

The composite severity prediction analyses were repeated using 10-fold cross-validation with BRF and comparable prediction metrics to train/test technique were obtained (as listed in Table S9B), with accuracies 59–76% and high AUC ROC values ranging from 0.82 to 0.87 for thresholds of two and above.

Relative importance of contextual and judgment features

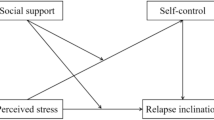

For the prediction of substance use and SUD behavior, contextual variables for age, depression (via PHQ score), and anxiety (via STAI score) were consistently the most important features, barring the alcohol use variable (see Fig. 2b–h). Combined, the three contextual variables contributed between 24% and 41% of the relative importance (Table S3B–H) and the 15 judgment variables contributed a combined 43–58% of the relative importance (Fig. 2 and Table S3). Across seven of the eight recency analyses, there was a consistent pattern of judgment variables being in the middle of the importance plot, lower than the top three contextual variables and higher than the remaining eight to nine contextual variables. This pattern was not observed for the alcohol use question where the top-most contributing variables were the judgment variables (Fig. 2a, Table S3A), collectively contributing 69% of relative importance.

Balanced Random Forest (BRF) analyses were used to classify recent versus not-recent classes for all substance use and SUD behavior variables. The predictors are arranged according to the mean decrease in Gini scores with the most important predictors for classification listed on the top. Plots correspond to each of the eight questions (as listed in Table 2) (a) alcohol, (b) cannabis, (c) opioid, (d) stimulant, (e) time spent, (f) social problems, (g) isolation and (h) withdrawal symptoms.

For the prediction of the composite severity (thresholds 2–5), age, PHQ score, and STAI score were again the most important features for BRF analyses (Fig. 3b–e), contributing 33–40% of relative importance. The 15 judgment variables contributed 43–55% of relative importance (Table S4B–E), with decreasing importance as the threshold increased. For the threshold of one, the top-most important features were the judgment variables with collectively 69% of relative importance.

Balanced Random Forest (BRF) analyses were used to classify high versus low for the composite GAIN-SS score. The predictors are arranged according to the mean decrease in Gini scores with the most important predictors for classification listed at the top. Plots a–e correspond to BRF analyses with thresholds (th) of 1–5, respectively.

For all analyses, the remaining contextual variables (education group, education in years, marital status, race, sex, and COVID-19 test and diagnosis) were consistently the lowest in classification importance, contributing a combined relative importance of 7–12% (Tables S3 and S4).

Judgment variable differences by three analyses: substance use, SUD behavior, and composite severity

Judgment variables were analyzed by: (i) recent vs. not-recent responses for substance use, (ii) SUD behavior (please see Table 2), and (iii) high vs. low composite severity groups using a threshold of 4 for total GAIN-SS scores. For this composite severity analysis, only one threshold was assessed, namely a threshold of 4 (th = 4), since it had the best performance for prediction analysis. Fourteen out of the 15 judgment variables differed across substance use, SUD behavior, and composite severity using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (α < 0.05; Tables 4A and S5A). One-sided Wilcoxon rank sum tests were then used to explore the location shift in the medians of the recent/high vs. not-recent/low groups with the null hypothesis that the median of the judgment variable distribution of recent/high group would be greater than or equal to not-recent/low group (α < 0.05; Tables 4A and S5A).

The location shifts for all judgment variables for SUD behavior and composite severity are summarized in Table 4B and substance use is summarized in Table S5B. For all recency analyses and composite severity analyses, the recent/high group had greater medians for Reward Aversion tradeoff and Reward Aversion consistency and lower medians for Tradeoff range and Consistency range when compared to the not-recent/low group. This was consistent across all recency and severity analyses (Tables 4B and S5B).

Those with more recent SUD behaviors and higher composite severity had greater medians for Loss Aversion (questions: time spent, isolation), Ante (questions: isolation), and Total Reward Risk (question: time spent) (Table 4B). The recent/high group had lower medians for Risk Aversion (questions: social problems, isolation, withdrawal symptoms, th = 4), Loss Resilience (questions: stimulant, social problems, th = 4), and Aversion Tipping Point (question: time spent) (Table 4B).

The recent group for substance use had greater medians for Loss Aversion (questions: cannabis, opioid, stimulant), Ante (questions: cannabis, opioid, stimulant), Insurance (question: alcohol), Reward TP (question: alcohol), and Aversion TP (question: opioid) (Table S5B). The recent group had lower medians for Risk Aversion (questions: cannabis, opioid, stimulant), Peak PR (question: alcohol), Peak NR (question: alcohol), Reward TP (question: stimulant), and Aversion TP (question: stimulant) (Table S5B). Total AR showed no significant differences across any analyses.

Discussion

This study sought to predict SUD behavior, along with substance use and composite severity, through a small set of judgment and contextual variables. Five general outcomes were observed for this study. First, SUD behavior was predicted with a high accuracy of 82–83% and moderate-high AUC ROCs between 0.72 and 0.74 using a train/test framework. Second, substance use itself was predicted with moderate-high accuracy (77–82% with AUC ROC 0.69–0.74) for cannabis, opioid, and stimulants, and lower results for alcohol use. Third, prediction accuracies for composite severity were between 81% and 84%, with a peak AUC ROC when the threshold was set to four out of a total of five. Similar prediction results were obtained independently with robust AUC ROC values using a cross-validation framework. Fourth, the top predictors were contextual measures of depression, anxiety, and age, with judgment variables consistently in the middle, and a large set of contextual variables at the bottom of importance plots. Fifth, judgment variables had a combined relative importance of 43–58% across all predictors for all questions, except alcohol use, where they were higher. Lastly, the judgment variables exhibited significant median shifts against SUD behavior and substance use, with unique constellations of judgment variables for each of the four SUD behaviors and four substance use variables.

This study used small sets of judgment and contextual variables to produce machine learning (ML) prediction results comparable to other published studies that depended on large variable sets or expensive neuroscience measures. Most studies predicting substance use depend on extensive sets of demographics, socio-environmental, mental health, family history, and lifestyle variables for prediction. Such is the case for studies predicting marijuana use using an elastic net with an AUC of 0.859 or using RF with an AUC of 0.9710. Using RF, another study with a large feature set predicted opioid use with an AUC of 0.8211. Prediction of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use produced an RMSE of 0.91 with a multivariate covariance generalized linear model in yet another study using a large feature set12. Studies like Jing et al. 202015 and Hu et al. 202016 have used psychological and health assessments resulting in a thousand variables to predict a substance use trajectory with 71–93% accuracy using RF and Naïve Bayes models. Other studies have used hundreds of variables from electronic health records and demographics to predict substance use with RF, resulting in an AUC ROC of 0.7313 and accuracies between 53% and 75%14 in clinical populations for ADHD and bipolar disorder. Recent neuroimaging studies involving tens of thousands of voxels and incorporating machine learning techniques to predict substance use96 have reported high accuracies of 82.7% and AUC ROC of 0.89219. Studies using social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram used text extraction from millions of posts to predict substance use with an AUC ROC of 0.8617 and alcohol use with an AUC ROC of 0.6518. Our study added to these works by predicting SUD behaviors and four categories of substance use independent of each other, using a small set of cognitive science variables as predictors.

To date, a limited set of studies have used behavioral data from cognitive tasks to predict substance use or its severity20. For example, Ahn and colleagues21 used behavioral data from five neurocognitive tasks indexing impulsivity to classify cocaine-dependent users from healthy controls with an AUC ROC of 0.91 with a Least Absolute shrinkage and selection operator classifier. Another study22 used an extensive dataset including behavioral data from a monetary choice questionnaire, stop signal task, and face recognition task, along with demographics, history of alcohol use and smoking, family history of substance use, trait and personality questionnaires, genetics, and brain volume and function to classify binge drinkers from non-drinkers using regularized logistic regression with an AUC ROC of 0.96. These cognitive tasks were completed by participants under supervision. Some studies10,11,12,13,22 used highly correlated predictors like current use of one substance to predict the use of the same or other drugs, or history of substance use. It has been noted that the use of one substance is commonly comorbid with the use of other substances to enhance similar effects or to get intoxicated faster (i.e., polysubstance use)4,97. The current study supports these prior works by adding accurate and sensitive prediction of SUD behaviors, substance use itself, and SUD severity via the implementation of machine learning and a short cognitive task that can be performed without supervision on a personal electronic device. Such assessments might enable the identification of early risk factors, monitoring of neurocognitive changes, and provide targets for early intervention.

The most important features for the prediction of SUD behavior in this study, along with substance use and composite severity, were contextual variables for depression, anxiety, and age, barring alcohol use as discussed below in the context of study limitations. It should be noted that separate studies have also shown anxiety55 and depression72 to be predicted with high accuracy from the same judgment variables, and some overlap in predictive contribution is expected. The mediation and moderation analyses in these published studies model anxiety55 and depression55 (reflecting complex interactions between contextual variables (e.g., demographics, mental health scores) and judgment variables, indicating that they form a system. These findings communicate that predictive accuracy arose from the combined effects of judgment and contextual variables rather than any single variable type in isolation. Depression and anxiety scores were also higher for the participants with recent substance use and SUD behaviors (see Fig. S2). Depression and anxiety can lead to substance use behaviors as self-treatment98,99,100. The prescription of psychoactive drugs for these mental health conditions can also induce substance use behaviors in high-risk individuals101. Conversely, these mental health conditions could be induced by the pharmacologic effects of substance use102,103. This naturally contributes to their strong predictive weight in the models in this study. To address this concern, additional analyses were conducted excluding depression and anxiety scores as predictors. The resulting performance metrics were comparable (see Table S8), indicating that judgment and demographic variables together still provide robust predictive capacity for substance use and SUD behaviors.

The 15 judgment variables contributed a cumulative relative importance of 43–58%. These variables quantify distinct components of judgment, including biases in judgment (i.e., the bounds to rationality as described by Kahneman50), which are pertinent to the study of altered judgment in substance use and SUD behaviors. Gini scores were minimally different across these judgment variables, consistent with other studies53,54,55 suggesting further research is needed to assess how these judgment variables interact or cluster together across different SUD behaviors. When the threshold was increased for segregating high vs. low composite severity, the prediction metrics improved for BRF (using both train/test and cross-validation frameworks), suggesting that more severe SUD were classified with higher accuracy. For the prediction of total severity (for thresholds 3–5) and SUD behavior (for social problems and withdrawal symptoms), employment status had a Gini score higher than for the judgment variables. This observation raises the hypothesis that current employment status may become important for the prediction of severe substance use behaviors. Such a hypothesis is consistent with other studies that have linked unemployment with increased substance use104. For alcohol use, the topmost predictors were the 15 judgment variables with 69% of cumulative relative importance, but the moderate-to-low accuracy and sensitivity measures for prediction (both train/test and cross-validation frameworks) suggest further research is warranted before interpreting the pattern of altered judgment variables with alcohol use. For all analyses, a majority of demographics, including number of years of education, marital status, race (ethnic group), sex, and the COVID-19 history variables, were consistently at the bottom of the relative importance plot, contributing only 7–12%, cumulatively. A similar effect has been reported in other prediction studies of mental health and medical judgment53,54,55, which raises a hypothesis for further study that contextual variables with low Gini importance values may still have salient effects in associative studies but not be predictive with large samples.

Judgment variables based on reward and aversion assessments provide an opportunity for interpretation of findings that are not possible with big data approaches using large sets of clinical variables. Specifically, unique patterns of judgment variable median shifts help in the interpretation of SUD behaviors. In this study, unique increases or decreases in judgment variables were observed with all SUD behavior variables. These judgment variable patterns for SUD behavior are discussed since these variables cover the four criterion categories defined by DSM-5 for SUD, independent of the substance being used. At this time, no DSM-5 framework exists for SUD behaviors across the broad array of putative addictions, unrelated to the use of substances, yet the ability to predict each SUD behavior with high accuracy raises the hypothesis that these behaviors may relate to a broader range of addictive conditions, such as overuse of food, overuse of gaming, or overuse of social media. Testing such a hypothesis might involve substituting questions about food, gambling, or social media for the substance use questions in the GAIN-SS and framing the four SUD behavior questions around the problem in question. With this hypothesis in mind, we discuss the unique patterns of median shifts in judgment variables for SUD behaviors in the text that follows.

Some judgment variables, such as the four judgment variables from the tradeoff function (Fig. 1d), showed the same direction of change across all SUD behavior variables and composite severity (Table 4B). Of these four measures, Reward Aversion Tradeoff describes the relative weighting of the approach to avoidance behavior, and Tradeoff range measures the variance of this relative weighting. Reward Aversion Consistency measures how conflicted or indifferent someone is in their reward-aversion preferences towards similar things, and Consistency range measures how much someone swings between the conflict or indifference. Together, higher reward aversion tradeoff and higher reward aversion consistency point to more approaching behavior with higher conflict towards both positive and negative stimuli (e.g., you both like and dislike something). Both the Tradeoff range and the Consistency range quantify the breadth of an individual’s set of positive and negative preferences; these variables were uniformly reduced for each question, which is consistent with reports of restriction in the set of activities and things an individual finds rewarding, which has been described as an important feature of substance use34,35. The similar constellation of these four judgment variable differences across all SUD behavior questions raises the hypothesis that they may be general variables framing addictive behaviors.

Judgment variables from the value function (Fig. 1b) and limit function (Fig. 1c) showed different patterns in their alterations across the four SUD behaviors. For example, the recent SUD behavior of time spent for substance acquisition or use showed increased Loss Aversion, along with lower Aversion Tipping Point (Aversion TP) and higher Total Risk Reward. A higher Loss Aversion corresponds to an overweighting of bad outcomes relative to good ones, which appears contrary to previous studies105,106 (please see Supplemental Material for longer discussion regarding Loss Aversion). When there is no uncertainty around a judgment (unlike the framework of reinforcement reward when there is uncertainty around a judgment65), those spending more time using or acquiring substances show a greater concern for losses over gains. The Aversion TP quantifies the negative value at which there is peak risk to overcome before making an avoidance action, and if it is lower, there is a lower aversive value to overcome before avoidance occurs. The higher Total Reward Risk suggests individuals see both greater risk around reward and reward itself, so the presence of increased risk is due to the increased assessment of reward, namely, reward is more meaningful. The SUD behavior of time spent for substance acquisition or use thus appears to reflect (a) an overweighting of losses when there is no uncertainty framing this assessment, (b) less negative value needed for avoidance (as for avoiding activity like work or family responsibilities), and (c) finding reward (as from substance use) more meaningful. Judgment variable shifts for other SUD behaviors are discussed in detail in Supplemental Material.

Participants with higher composite severity had lower Risk Aversion, lower Loss Resilience, greater Reward Aversion tradeoff, lower Tradeoff range, greater Reward Aversion consistency, and lower Consistency range. Lower Risk Aversion indicates individuals would prefer more possibilities for potential gain than realized gain (as opposed to one bird in the hand, they prefer two birds in the bush). Individuals with higher composite scores would prefer actions that lead to increased uncertain outcomes, which is consistent with risk-seeking in people with recent substance use behaviors32,33,36,48,107. The same gambler’s mentality applies to aversion and sanctions, namely, persons preferred more possibilities for potential loss than realized loss. Lower Loss Resilience also points to having a reduced ability to rebound from bad outcomes. In summary, individuals with higher composite scores are more risk-seeking32,33,36,48,107, less resilient to losses, have approaching behavior with higher conflict towards both positive and negative stimuli, and a restriction in the set of activities and things an individual finds rewarding34,35.

Several limitations should be noted. First, participants with mental health conditions were oversampled to meet criteria for other survey components not discussed here. This oversampling could potentially bias results, and future work might utilize a general population sample to verify the presented findings. Second, all variables were self-reported and not collected from clinical records or framed as a controlled trial with investigator-administered survey instruments. Given that this study was performed with double-blinding and anonymization of data before its collection, it allowed subjects to be more open in their responses, reducing concern for this issue. Thirdly, participants were recruited from the United States, where substance use prevalence may be impacted by region and culture, thereby affecting prediction results. Fourth, data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic when the incidences of anxiety and depression were reported higher108,109, potentially leading to a greater incidence of substance use behaviors. Fifth, the low to moderate prediction results for alcohol use may be due to lower alcohol usage reporting from young adults because of reduced socialization during lockdown and social distancing110,111. Alcohol use was reported to be more than twice as much as cannabis, and approximately tenfold opiate and stimulant use; it is possible that the reporting for opiates and stimulants produced anchoring effects that reduced the reporting for alcohol. It will be important to prospectively investigate if similar behavioral patterns predict substance use behaviors in the absence of a pandemic.

This study represents one of the first to integrate a computational cognition framework with machine learning to assess how human judgment can be used to predict SUD behavior, along with substance use and composite severity. The SUD behavior variables used in this study cover the four criterion categories defined by DSM-5 for SUD, independent of the substance being used. The computational cognition framework consisted of 15 judgment variables extracted from a short (3–4 min), simple, and unsupervised picture rating task that can be easily completed on a personal electronic device. Using these judgment variables, along with a small set of contextual variables (e.g., demographics, depression and anxiety scores, and COVID-19 history), this study achieved moderate to high prediction metrics for substance use and up to 83% accuracy and 0.74 AUC ROC for SUD behavior. This work produced up to 84% accuracy for composite severity prediction. In these prediction analyses, the most important variables were three contextual variables (age, depression, and anxiety scores), contributing 24–41% of relative importance, whereas judgment variables contributed up to a cumulative value of 58% of the total relative importance. Judgment variables exhibited unique profiles across each of the four SUD behavior variables. Judgment variable profiles also revealed that participants with higher composite severity scores are more risk-seeking, less resilient to losses, have approach behavior with higher conflict towards both positive and negative stimuli, and a reduced variability in their set of preferences. This study supports the hypothesis that biases in human judgment, with context, can accurately predict SUD behaviors and the substances used. These results could improve diagnostics, prognostics, treatment development, and efficacy for SUD. Given these results for predicting SUD behaviors, it is possible they might be generalized to other conditions focused on short-term repetitive reward at the expense of potential sanctions; in this context, SUD behaviors would frame a hypothesis generalizing addiction beyond just substance use.

Data availability

Data used in predictive and statistical analyses have been uploaded as an appendix.

Code availability

Code used for prediction analysis has been provided at the end of Supplemental Information file.

References

NIDA. Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction: Introduction https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/introduction?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Hyman, S. E. Addiction: a disease of learning and memory. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1414–1422 (2005).

Hyman, S. E. The neurobiology of addiction: implications for voluntary control of behavior. Am. J. Bioeth. 7, 8–11 (2007).

CDC Yellow Book 2024. Substance Use & Substance Use Disorders https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/additional-considerations/substance-use.

DSM V. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder Fifth Edition Text Revision. Textbook of Psychiatry for Intellectual Disability and Autism Spectrum Disorder 609–623 (DSM V, 2022).

Dennis, M. L. T., Feeney, L. H., Stevens, L. & Bedoya, B. A. GAIN-SS Global Appraisal of Individual Needs-Short Screener (GAIN-SS): Administration and Scoring Manual Version 2.0.1. 1–26 http://www.chestnut.org/LI/gain/GAIN_SS/index.html (2007).

Jonaki et al. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Vol. 74 (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015).

Azmi R. J. & Doug M. B. Substance Use Disorder—StatPearls—NCBI Bookshelf (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Vázquez, A. L. et al. Innovative identification of substance use predictors: machine learning in a national sample of Mexican children. Prev. Sci. 21, 171-–181 (2020).

Parekh, T. & Fahim, F. Building risk prediction models for daily use of marijuana using machine learning techniques. Drug Alcohol Depend. 225, 108789 (2021).

Han, D. H., Lee, S. & Seo, D. C. Using machine learning to predict opioid misuse among U.S. adolescents. Prev. Med. 130, 105886 (2020).

Ruberu, T. L. M. et al. Joint risk prediction for hazardous use of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco among adolescents: a preliminary study using statistical and machine learning. Prev. Med. Rep. 25, 101674 (2022).

Zhang-James, Y. et al. Machine-learning prediction of comorbid substance use disorders in ADHD youth using Swedish registry data. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61, 1370–1379 (2020).

Oliva, V. et al. Machine learning prediction of comorbid substance use disorders among people with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Med. 11, 3935 (2022).

Hu, Z. et al. Analysis of substance use and its outcomes by machine learning: II. Derivation and prediction of the trajectory of substance use severity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 206, 107604 (2020).

Jing, Y. et al. Analysis of substance use and its outcomes by machine learning I. Childhood evaluation of liability to substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 206, 107605 (2020).

Ding, T., Bickel, W. K. & Pan, S. Multi-view unsupervised user feature embedding for social media-based substance use prediction. In EMNLP 2017—Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Proc 2275–2284 (conference proceeding article, 2017).

Hassanpour, S., Tomita, N., DeLise, T., Crosier, B. & Marsch, L. A. Identifying substance use risk based on deep neural networks and Instagram social media data. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 487–494 (2019).

Kulkarni, K. R. et al. An interpretable and predictive connectivity-based neural signature for chronic cannabis use. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 8, 320–330 (2023).

Christensen, E. et al. Neurocognitive predictors of addiction-related outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 152, 105295 (2023).

Ahn, W. Y., Ramesh, D., Moeller, F. G. & Vassileva, J. Utility of machine-learning approaches to identify behavioral markers for substance use disorders: impulsivity dimensions as predictors of current cocaine dependence. Front. Psychiatry 7, 181011 (2016).