Abstract

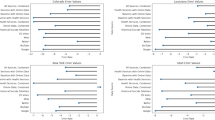

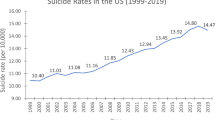

This study aimed to categorize county clusters of multidimensional social determinants of health (SDOH) using unsupervised machine learning and to analyze their association with county-level suicide rates, considering temporal, geographic and demographic variation. We analyzed aggregated SDOH data across 3,018 US counties for 2009, 2014 and 2019, which were linked to county-level suicide rates from the National Vital Statistics System. We identified three distinct SDOH clusters: ‘REMOTE’ (rural, elderly, marginalized environments, old housing, traditional systems, empty houses), ‘COPE’ (complex family dynamics, high consumption of health services, poverty, extreme heat) and ‘DIVERSE’ (dense, immigrant rich, environmentally challenged, economically unequal, racial/ethnic diversity, saturated health care, expensive housing). We used negative binomial regression after identifying clusters to estimate the associations between county-level SDOH clusters and suicide rates. Compared with other clusters, REMOTE was associated with higher overall suicide rates, particularly among men; COPE showed elevated suicide rates among whites; and DIVERSE exhibited increased rates among women and Black and Hispanic populations. The distribution of suicide rates across US states corresponded to the variations in SDOH cluster distribution within each state. These findings provide a foundation for designing more effective, data-driven suicide prevention strategies tailored to specific regional and demographic contexts.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$79.00 per year

only $6.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All raw data in this study are publicly available and can be retrieved from the US National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Mortality Data (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/deaths.htm) and US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Social Determinants of Health Database (https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html).

Code availability

Data analysis was performed using R version 4.4.2, leveraging several specialized packages to ensure robust and reproducible results. The ‘NbClust’ package (version 3.0.1) was used to determine the optimal number of clusters, while ‘cluster’ (version 2.1.6) facilitated clustering techniques and visualization. Core statistical computations and modeling were conducted using the ‘stats’ package (version 3.6.2). For regression modeling, including elastic net and regularization, the ‘glmnet’ package (version 4.1.8) was employed. In addition, geographically weighted regression was implemented using the ‘spgwr’ package (version 0.6-37). Code is available at github.com/X-PLORE-Lab/sdoh_clustering_suicide.

References

Stone, D. M., Mack, K. A. & Qualters, J. Notes from the field: recent changes in suicide rates, by race and ethnicity and age group—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 72, 160–162 (2023).

Provisional Suicide Deaths in the United States, 2022 (CDC, 2023); https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/s0810-US-Suicide-Deaths-2022.html

Bridge, J. A. et al. Suicide trends among elementary school-aged children in the United States from 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 673–677 (2015).

Opara, I. et al. Suicide among Black children: an integrated model of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicide and intersectionality theory for researchers and clinicians. J. Black Stud. 51, 611–631 (2020).

Martínez-Alés, G. et al. Age, period, and cohort effects on suicide death in the United States from 1999 to 2018: moderation by sex, race, and firearm involvement. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3374–3382 (2021).

AACAP AACAP Policy Statement on Increased Suicide Among Black Youth in the US (AACAP, accessed 12 October 2023); https://www.aacap.org/aacap/Policy_Statements/2022/AACAP_Policy_Statement_Increased_Suicide_Among_Black_Youth_US.aspx

Xiao, Y. & Lu, W. Temporal trends and disparities in suicidal behaviors by sex and sexual identity among Asian American adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e214498 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Cerel, J. & Mann, J. J. Temporal trends in suicidal ideation and attempts among US adolescents by sex and race/ethnicity, 1991–2019. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2113513 (2021).

Lindsey, M. A., Sheftall, A. H., Xiao, Y. & Joe, S. Trends of suicidal behaviors among high school students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics 144, e20191187 (2019).

Disparities in Suicide | Suicide Prevention (CDC, accessed 19 January 2024); https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/disparities-in-suicide.html

About Multiple Cause of Death, 2018–2023 Single Race (CDC, accessed 1 January 1 2024); http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-expanded.html

Social Determinants of Health (CDC, accessed 12 October 2023); https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html

Social Determinants of Health (NCHHSTP and CDC, accessed 19 January 2024); https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/socialdeterminants/index.html

VanderWeele, T. & Robinson, W. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology 25, 473–484 (2014).

Shrider, E. A., Kollar, M., Chen, F. & Semega, J. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 (US Government Publishing Office, 2021).

Cyr, M. E., Etchin, A. G., Guthrie, B. J. & Benneyan, J. C. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 974 (2019).

Robertson, R. A., Standley, C. J., Gunn, J. F. III & Opara, I. Structural indicators of suicide: an exploration of state-level risk factors among Black and White people in the United States. J. Public Ment. Health 21, 23–34 (2022).

Smith, N. D. L. & Kawachi, I. State-level social capital and suicide mortality in the 50 US states. Soc. Sci. Med. 120, 269–277 (2014).

Hoffmann, J. A., Farrell, C. A., Monuteaux, M. C., Fleegler, E. W. & Lee, L. K. Association of pediatric suicide with county-level poverty in the United States, 2007–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 287–294 (2020).

Knipe, D., Padmanathan, P., Newton-Howes, G., Chan, L. F. & Kapur, N. Suicide and self-harm. Lancet 399, 1903–1916 (2022).

Luby, J. & Kertz, S. Increasing suicide rates in early adolescent girls in the United States and the equalization of sex disparity in suicide: the need to investigate the role of social media. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e193916 (2019).

Mustanski, B. & Espelage, D. L. Why are we not closing the gap in suicide disparities for sexual minority youth? Pediatrics 145, e20194002 (2020).

Tsai, A. C., Lucas, M. & Kawachi, I. Association between social integration and suicide among women in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 987–993 (2015).

de Leo, D. Ageism and suicide prevention. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 192–193 (2018).

Van Orden, K. A. & Conwell, Y. Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment. Health 20, 240–251 (2016).

Tsai, A. C., Lucas, M., Sania, A., Kim, D. & Kawachi, I. Social integration and suicide mortality among men: 24-year cohort study of US health professionals. Ann. Intern. Med. 161, 85–95 (2014).

Perry, S. W. et al. Achieving health equity in US suicides: a narrative review and commentary. BMC Public Health 22, 1360 (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. Patterns of social determinants of health and child mental health, cognition, and physical health. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4218 (2023).

Skinner, A., Osgood, N. D., Occhipinti, J. A., Song, Y. J. C. & Hickie, I. B. Unemployment and underemployment are causes of suicide. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg3758 (2023).

Graves, J. M., Abshire, D. A., Mackelprang, J. L., Amiri, S. & Beck, A. Association of rurality with availability of youth mental health facilities with suicide prevention services in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2021471 (2020).

Bower, M. et al. The impact of the built environment on loneliness: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health Place 79, 102962 (2023).

Kind, A. J. & Buckingham, W. R. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2456–2458 (2018).

Flanagan, B. E., Gregory, E. W., Hallisey, E. J., Heitgerd, J. L. & Lewis, B. A social vulnerability index for disaster management. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 8, 3 (2011).

Kirkbride, J. B. et al. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry 23, 58–90 (2024).

Sussell, A. Suicide rates by industry and occupation—National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7250a2 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. Impacts of land use and population density on seasonal surface water quality using a modified geographically weighted regression. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 450–466 (2016).

CDC/ATSDR SVI Data and Documentation Download | Place and Health (CDC and ATSDR, accessed 6 May 2023); https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/data_documentation_download.html

Liu, S. et al. Social vulnerability and risk of suicide in US adults, 2016–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e239995 (2023).

Bundy, J. D. et al. Social determinants of health and premature death among adults in the USA from 1999 to 2018: a national cohort study. Lancet Public Health 8, e422–e431 (2023).

Masulli, F. & Rovetta, S. Clustering high-dimensional data. In Proc. Clustering High-Dimensional Data: First International Workshop, CHDD 2012, Naples, Italy, May 15, 2012, Revised Selected Papers (eds Masulli, F. et al.) 1–13 (Springer, 2015).

Zhang, C.-H. & Huang, J. The sparsity and bias of the Lasso selection in high-dimensional linear regression. Ann. Stat. 36, 1567–1594 (2008).

Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A. & Auerbach, R. P. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: a systematic review. Am. J. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864 (2021).

Mock, C., Quansah, R., Krishnan, R., Arreola-Risa, C. & Rivara, F. Strengthening the prevention and care of injuries worldwide. Lancet 363, 2172–2179 (2004).

Thomson, R. M. et al. How do income changes impact on mental health and wellbeing for working-age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 7, e515–e528 (2022).

Blumenthal, D., Fowler, E. J., Abrams, M. & Collins, S. R. Covid-19—implications for the health care system. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1483–1488 (2020).

Beseran, E. et al. Deaths of despair: a scoping review on the social determinants of drug overdose, alcohol-related liver disease and suicide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912395 (2022).

Ramchand, R., Gordon, J. A. & Pearson, J. L. Trends in suicide rates by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2111563 (2021).

Kolak, M., Bhatt, J., Park, Y. H., Padrón, N. A. & Molefe, A. Quantification of neighborhood-level social determinants of health in the continental United States. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e1919928 (2020).

Sit, H. F., Hall, B. J. & Li, S. X. Cultural adaptation of interventions for common mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 374–376 (2023).

Talukder, S. et al. Urban health in the post-2015 agenda. Lancet 385, 769 (2015).

Romanello, M. et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet 398, 1619–1662 (2021).

Bennett, K. J., Borders, T. F., Holmes, G. M., Kozhimannil, K. B. & Ziller, E. What is rural? Challenges and implications of definitions that inadequately encompass rural people and places. Health Aff. 38, 1985–1992 (2019).

Dwyer-Lindgren, L. et al. Cause-specific mortality by county, race, and ethnicity in the USA, 2000–19: a systematic analysis of health disparities. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01088-7 (2023).

Imbens, G. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials: a commentary on Deaton and Cartwright. Soc. Sci. Med. 210, 50–52 (2018).

Deaton, A. & Cartwright, N. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med. 210, 2–21 (2018).

Lund, C. et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 357–369 (2018).

Frank, J. et al. Work as a social determinant of health in high-income countries: past, present, and future. Lancet 402, 1357–1367 (2023).

Bhugra, D. & Ventriglio, A. Commercial determinants of mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 69, 1065–1067 (2023).

Dwyer-Lindgren, L. et al. Life expectancy by county, race, and ethnicity in the USA, 2000–19: a systematic analysis of health disparities. Lancet 400, 25–38 (2022).

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) (AHRQ, accessed 1 May 2023); https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/index.html

Hwong, A. R. et al. Climate change and mental health research methods, gaps, and priorities: a scoping review. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e281–e291 (2022).

Helbich, M. et al. Natural environments and suicide mortality in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional, ecological study. Lancet Planet. Health 2, e134–e139 (2018).

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: 10th Revision (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, accessed 10 January 2024); https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en

About Multiple Cause of Death, 1999–2020 (CDC, accessed 4 September 2023); https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2020 (CDC, accessed 4 September 2023); https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html#Assurance%20of%20Confidentiality

Müllner, D. Modern hierarchical, agglomerative clustering algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1109.2378 (2011).

Murtagh, F. & Legendre, P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 31, 274–295 (2014).

Laszlo, A. M., Hulman, A., Csicsman, J., Bari, F. & Nyari, T. A. The use of regression methods for the investigation of trends in suicide rates in Hungary between 1963 and 2011. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 50, 249–256 (2015).

Lindén, A. & Mäntyniemi, S. Using the negative binomial distribution to model overdispersion in ecological count data. Ecology 92, 1414–1421 (2011).

Bouwmeester, W. et al. Prediction models for clustered data: comparison of a random intercept and standard regression model. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 19 (2013).

Santosa, F. & Symes, W. W. Linear inversion of band-limited reflection seismograms. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 7, 1307–1330 (1986).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 58, 267–288 (1996).

Hastie, T., Friedman, J. & Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning (Springer, 2001); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21606-5

Ismail, N. & Zamani, H. Estimation of claim count data using negative binomial, generalized Poisson, zero-inflated negative binomial and zero-inflated generalized Poisson regression models. Casualty Actuarial Society E-Forum 41, 1–28 (2013).

Chai, T. & Draxler, R. R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE). Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 7, 1525–1534 (2014).

Rural Classifications (USDA ERS, accessed 8 September 2023); https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the US National Institute of Mental Health (RF1MH134649; Y.X.), American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (YIG-2-133-22; Y.X.), Mental Health Research Network (Y.X.), Google (Y.X.), the US National Institute on Drug Abuse Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH, Y.X.), the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24DA061696-01; A.C.T.) and the Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Consortium to Advance Health Equity and Researcher Diversity (AIM-AHEAD), a program of the US National Institutes of Health (1OT2OD032581-02-259; Y.X., J.P.). The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We would like to acknowledge Dr L. Snowden for his invaluable contributions to this work. Dr Snowden was engaged in the conceptualization and early writing of this manuscript prior to his passing in January 2025. As a pioneering scholar and leader in mental health services research, his intellectual guidance shaped this paper and many others in the field. We are honored to carry forward his legacy through this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., Y.M. and J.J.M. carried out concept and design. Y.X., Y.M., T.T.B., A.C.T., L.R.S., J.C.-C.C., J.P. and J.J.M. carried out acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. Y.X. and Y.M. drafted the paper. Y.X., Y.M., T.T.B., A.C.T., L.R.S., J.C.-C.C., J.P. and J.J.M. provided critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content. Y.X. and Y.M. carried out statistical analysis. Y.X. obtained funding. Y.X. provided administrative, technical or material support. Y.X. and Y.M. had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Y.X. and Y.M. have made equal contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.C.T. reports an honorarium from Elsevier for his work as co-editor in chief of the Elsevier-owned journal SSM-Mental Health. J.J.M. reports royalties for commercial use of the C-SSRS from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene and for the Columbia Psychiatry Pathways App from Columbia University. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–9, Tables 1–20, Results 1–3 and Methods 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Meng, Y., Brown, T.T. et al. Machine learning to investigate policy-relevant social determinants of health and suicide rates in the United States. Nat. Mental Health 3, 675–684 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00424-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00424-4