Abstract

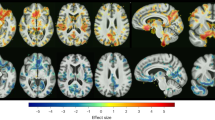

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent condition that profoundly impairs quality of life across diverse populations. Despite widespread use, current antidepressant and psychotherapeutic treatments exhibit limited efficacy and unsatisfactory response rates. Progress in developing effective therapies is hampered by the insufficiently understood heterogeneity of MDD and its elusive underlying mechanisms. Here, to address these challenges, we develop a novel machine learning framework that identifies structure–function covariation through target-oriented fusion of structural and functional connectivity, which robustly predicts individual-level antidepressant response (sertraline, R2 = 0.31; placebo, R2 = 0.22). Validation in an independent escitalopram-medicated MDD cohort confirms the biomarker’s generalizability (P = 0.01) and suggests an overlap of psychopharmacological signatures across selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Our models highlight the right precuneus as a common key region for both sertraline and placebo responses, with the right middle frontal gyrus and left fusiform gyrus specific to sertraline and the left inferior and middle frontal gyri to placebo. We also find that structural connectivity is more predictive of sertraline response, while functional connectivity better predicts placebo response. The framework further decomposes the overall predictive patterns into three constitutive network constellations (default-mode regulatory, affective and sensory processing), which exhibit distinct generalizable structure–function covariation and treatment-specific association with personality traits and behavioral/cognitive profiles. These findings provide unique insights to the structure–function covariation in patients with MDD, its association to the heterogeneity in antidepressant response and the dissection of the intricate MDD neuropsychopharmacology, paving the way for precision medicine and development of more targeted antidepressant therapeutics. Clinicaltrials.gov registration: Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care for Depression (EMBARC), NCT01407094.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$79.00 per year

only $6.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The EMBARC cohort is publicly available through the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive (NDA) (https://nda.nih.gov/edit_collection.html?id=2199). The CAN-BIND-1 cohort is available under a data use agreement with Brain-CODE, based at the Ontario Brain Institute (https://www.braincode.ca/content/canadian-biomarker-integration-network-depression-can-bind-0).

Code availability

All analyses were conducted in MATLAB (version R2022b), and the code is available via our GitHub repository at https://github.com/Xiaoyu-Tong/TargetOrientedMultimodalFusion--AntidepressantResponse.

References

Lai, C.-H. Promising neuroimaging biomarkers in depression. Psychiatry Investig. 16, 662 (2019).

Kambeitz, J. et al. Detecting neuroimaging biomarkers for depression: a meta-analysis of multivariate pattern recognition studies. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 330–338 (2017).

Buch, A. M. & Liston, C. Dissecting diagnostic heterogeneity in depression by integrating neuroimaging and genetics. Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 156–175 (2021).

Kraus, C., Kadriu, B., Lanzenberger, R., Zarate, C. A. Jr & Kasper, S. Prognosis and improved outcomes in major depression: a review. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 127 (2019).

Runia, N. et al. The neurobiology of treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 132, 433–448 (2022).

Enneking, V., Leehr, E. J., Dannlowski, U. & Redlich, R. Brain structural effects of treatments for depression and biomarkers of response: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Psychol. Med. 50, 187–209 (2020).

Fu, C. H. et al. Neuroanatomical dimensions in medication-free individuals with major depressive disorder and treatment response to SSRI antidepressant medications or placebo. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 164–176 (2024).

Widge, A. S. et al. Electroencephalographic biomarkers for treatment response prediction in major depressive illness: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 44–56 (2019).

Tozzi, L., Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N., Korgaonkar, M. S. & Williams, L. M. Connectivity of the cognitive control network during response inhibition as a predictive and response biomarker in major depression: evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 462–472 (2020).

Wu, W. et al. An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 439–447 (2020).

Zhao, K. et al. Individualized fMRI connectivity defines signatures of antidepressant and placebo responses in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2490–2499 (2023).

Geddes, J. R. et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361, 653–661 (2003).

Kanai, T. et al. Time to recurrence after recovery from major depressive episodes and its predictors. Psychol. Med. 33, 839–845 (2003).

Breedvelt, J. J. F. et al. An individual participant data meta-analysis of psychological interventions for preventing depression relapse. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 154–163 (2024).

Honey, C. J. et al. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2035–2040 (2009).

Fotiadis, P. et al. Structure–function coupling in macroscale human brain networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 688–704 (2024).

Sui, J., Adali, T., Yu, Q., Chen, J. & Calhoun, V. D. A review of multivariate methods for multimodal fusion of brain imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods 204, 68–81 (2012).

Zhang, Y.-D. et al. Advances in multimodal data fusion in neuroimaging: overview, challenges, and novel orientation. Inf. Fusion 64, 149–187 (2020).

Tulay, E. E., Metin, B., Tarhan, N. & Arıkan, M. K. Multimodal neuroimaging: basic concepts and classification of neuropsychiatric diseases. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 50, 20–33 (2019).

Maglanoc, L. A. et al. Multimodal fusion of structural and functional brain imaging in depression using linked independent component analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 241–255 (2020).

Burke, M. J. et al. Placebo effects and neuromodulation for depression: a meta-analysis and evaluation of shared mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 1658–1666 (2022).

Pecina, M., Heffernan, J., Wilson, J., Zubieta, J.-K. & Dombrovski, A. Prefrontal expectancy and reinforcement-driven antidepressant placebo effects. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 222 (2018).

Lii, T. R. et al. Randomized trial of ketamine masked by surgical anesthesia in patients with depression. Nat. Ment. Health 1, 876–886 (2023).

Savarese, P., Silva, H. & Maire, M. Winning the lottery with continuous sparsification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 11380–11390 (2020).

Trivedi, M. H. et al. Establishing moderators and biosignatures of antidepressant response in clinical care (EMBARC): rationale and design. J. Psychiatr. Res. 78, 11–23 (2016).

Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb. Cortex 28, 3095–3114 (2017).

Buckner, R. L., Krienen, F. M., Castellanos, A., Diaz, J. C. & Yeo, B. T. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 2322–2345 (2011).

Choi, E. Y., Yeo, B. T. & Buckner, R. L. The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 108, 2242–2263 (2012).

Zhang, Y.-R. et al. Personality traits and brain health: a large prospective cohort study. Nat. Ment. Health 1, 722–735 (2023).

Korgaonkar, M. S., Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N., Fornito, A. & Williams, L. M. Intrinsic connectomes are a predictive biomarker of remission in major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 1537–1549 (2020).

Williams, L. M., Debattista, C., Duchemin, A., Schatzberg, A. F. & Nemeroff, C. B. Childhood trauma predicts antidepressant response in adults with major depression: data from the randomized international study to predict optimized treatment for depression. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e799 (2016).

Damsa, C. et al. ‘Dopamine-dependent' side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a clinical review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 1064–1068 (2004).

Xue, W. et al. Molecular mechanism for the allosteric inhibition of the human serotonin transporter by antidepressant escitalopram. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 13, 340–351 (2022).

Sui, J. et al. In search of multimodal neuroimaging biomarkers of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 78, 794–804 (2015).

Foti, D., Carlson, J. M., Sauder, C. L. & Proudfit, G. H. Reward dysfunction in major depression: multimodal neuroimaging evidence for refining the melancholic phenotype. NeuroImage 101, 50–58 (2014).

Scheepens, D. S. et al. The link between structural and functional brain abnormalities in depression: a systematic review of multimodal neuroimaging studies. Front. Psychiatry 11, 485 (2020).

Johnston, J. A. et al. Multimodal neuroimaging of frontolimbic structure and function associated with suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 667–675 (2017).

Shi, J., Zheng, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Q. & Ying, S. Multimodal neuroimaging feature learning with multimodal stacked deep polynomial networks for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 173–183 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Multimodal neuroimaging feature learning for multiclass diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 1132–1140 (2014).

Lei, D. et al. Integrating machining learning and multimodal neuroimaging to detect schizophrenia at the level of the individual. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 1119–1135 (2020).

Weigand, A. et al. Predicting antidepressant effects of ketamine: the role of the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex as a multimodal neuroimaging biomarker. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 1003–1013 (2022).

Tong, X. et al. Symptom dimensions of resting-state electroencephalographic functional connectivity in autism. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 287–298 (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Connectome analysis of functional and structural hemispheric brain networks in major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 136 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Distinct MRI-based functional and structural connectivity for antidepressant response prediction in major depressive disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. 160, 19–27 (2024).

Kato, M. et al. Discontinuation of antidepressants after remission with antidepressant medication in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 118–133 (2021).

Hansen, R. et al. Meta-analysis of major depressive disorder relapse and recurrence with second-generation antidepressants. Psychiatr. Serv. 59, 1121–1130 (2008).

Williams, N., Simpson, A. N., Simpson, K. & Nahas, Z. Relapse rates with long-term antidepressant drug therapy: a meta-analysis. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 24, 401–408 (2009).

Cheng, W. et al. Functional connectivity of the precuneus in unmedicated patients with depression. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3, 1040–1049 (2018).

Tong, X. et al. Individual deviations from normative electroencephalographic connectivity predict antidepressant response. J. Affect. Disord. 351, 220–220 (2024).

Buchsbaum, M. S. et al. Effect of sertraline on regional metabolic rate in patients with affective disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 41, 15–22 (1997).

Cooper, C. M. et al. Cerebral blood perfusion predicts response to sertraline versus placebo for major depressive disorder in the EMBARC trial. eClinicalMedicine 10, 32–41 (2019).

Mayberg, H. S. et al. The functional neuroanatomy of the placebo effect. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 728–737 (2002).

Rolle, C. E. et al. Cortical connectivity moderators of antidepressant vs placebo treatment response in major depressive disorder: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 397–408 (2020).

Gabbay, V. et al. Striatum-based circuitry of adolescent depression and anhedonia. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 52, 628–641. e613 (2013).

Avissar, M. et al. Functional connectivity of the left DLPFC to striatum predicts treatment response of depression to TMS. Brain Stimul. 10, 919–925 (2017).

Otte, C. et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 1–20 (2016).

Bhatia, K. D., Henderson, L. A., Hsu, E. & Yim, M. Reduced integrity of the uncinate fasciculus and cingulum in depression: a stem-by-stem analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 235, 220–228 (2018).

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Wager, T. D. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 603–611 (2015).

Li, K. et al. Aberrant resting-state functional connectivity in MDD and the antidepressant treatment effect—a 6-month follow-up study. Brain Sci. 13, 705 (2023).

Mayberg, H. S. et al. Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical response. Biol. Psychiatry 48, 830–843 (2000).

Roberts, A. C. The importance of serotonin for orbitofrontal function. Biol. Psychiatry 69, 1185–1191 (2011).

Hornboll, B. et al. Acute serotonin 2A receptor blocking alters the processing of fearful faces in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 903–914 (2013).

Preller, K. H. et al. Effects of serotonin 2A/1A receptor stimulation on social exclusion processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5119–5124 (2016).

Ray, D., Bezmaternykh, D., Mel’nikov, M., Friston, K. J. & Das, M. Altered effective connectivity in sensorimotor cortices is a signature of severity and clinical course in depression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2105730118 (2021).

Wüthrich, F. et al. The neural signature of psychomotor disturbance in depression. Mol. Psychiatry 29, 317–326 (2024).

Ding, Y. et al. Disrupted cerebellar-default mode network functional connectivity in major depressive disorder with gastrointestinal symptoms. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 833592 (2022).

Scalabrini, A. et al. Abnormally slow dynamics in occipital cortex of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 374, 523–530 (2025).

Zhu, M. et al. Over-integration of visual network in major depressive disorder and its association with gene expression profiles. Transl. Psychiatry 15, 86 (2025).

Harmer, C. J., Duman, R. S. & Cowen, P. J. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 409–418 (2017).

First, M. B. Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Biometrics Research Department, 1997).

Nogovitsyn, N. et al. Hippocampal tail volume as a predictive biomarker of antidepressant treatment outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder: a CAN-BIND report. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 283–291 (2020).

Lam, R. W. et al. Discovering biomarkers for antidepressant response: protocol from the Canadian Biomarker Integration Network in Depression (CAN-BIND) and clinical characteristics of the first patient cohort. BMC Psychiatry 16, 1–13 (2016).

Leucht, S., Fennema, H., Engel, R. R., Kaspers-Janssen, M. & Szegedi, A. Translating the HAM-D into the MADRS and vice versa with equipercentile linking. J. Affect. Disord. 226, 326–331 (2018).

Raichle, M. E. & Snyder, A. Z. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. NeuroImage 37, 1083–1090 (2007).

MacQueen, G. M. et al. The Canadian Biomarker Integration Network in Depression (CAN-BIND): magnetic resonance imaging protocols. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 44, 223 (2019).

Veraart, J. et al. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. NeuroImage 142, 394–406 (2016).

Tustison, N. J. et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1310–1320 (2010).

Andersson, J. L. R. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage 125, 1063–1078 (2016).

Andersson, J. L. R., Graham, M. S., Zsoldos, E. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. Incorporating outlier detection and replacement into a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images. NeuroImage 141, 556–572 (2016).

Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111–116 (2019).

Avants, B. B., Epstein, C. L., Grossman, M. & Gee, J. C. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med. Image Anal. 12, 26–41 (2008).

Zhang, Y., Brady, J. M. & Smith, S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20, 45–57 (2002).

Greve, D. N. & Fischl, B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. NeuroImage 48, 63–72 (2009).

Pruim, R. H. et al. ICA-AROMA: a robust ICA-based strategy for removing motion artifacts from fMRI data. NeuroImage 112, 267–277 (2015).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Steps toward optimizing motion artifact removal in functional connectivity MRI; a reply to Carp. NeuroImage 76, 439–441 (2013).

Yeh, F. C., Wedeen, V. J. & Tseng, W. Y. Generalized q-sampling imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1626–1635 (2010).

Yeh, F. C., Verstynen, T. D., Wang, Y., Fernandez-Miranda, J. C. & Tseng, W. Y. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS ONE 8, e80713 (2013).

Yeh, F. C. Shape analysis of the human association pathways. NeuroImage 223, 117329 (2020).

Thomas Yeo, B. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Weinberg, R. & Patel, Y. C. Simulated intraclass correlation coefficients and their z transforms. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 13, 13–26 (1981).

Fouladi, R. T. & Steiger, J. H. The Fisher transform of the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient and its square: cumulants, moments, and applications. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 37, 928–944 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R01MH129694 to Y.Z. and philanthropic funding and grants from the One Mind-Baszucki Brain Research Fund, the SEAL Future Foundation and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation to G.A.F. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, and the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, nor were they involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication. We would also like to acknowledge the individuals and organizations that have made data available for this research, including CAN-BIND, the Ontario Brain Institute, the Brain-CODE platform and the government of Ontario.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.T. conceptualized and designed the work, wrote the code, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted and revised the paper. K.Z. preprocessed and interpreted the data and revised the paper. G.A.F., H.X. and N.B.C. interpreted the data, refined the design of the work and revised the paper. C.J.K., D.J.O., Y.S., C.B.N., M.T. and A.E. interpreted the data and revised the paper. Y.Z. conceptualized and designed the work, oversaw the analysis and interpretation of the data and revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.A.F. received monetary compensation for consulting work for SynapseBio AI and owns equity in Alto Neuroscience. C.J.K. reports equity from Alto Neuroscience. C.B.N. is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Texas Child Mental Health Consortium and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. C.B.N. is a consultant for ANeuroTech, Abbott Laboratories, Engrail Therapeutics, Clexio Biosciences Ltd., Sero (previously Galen Mental Health LLC), Goodcap Pharmaceuticals, Sage Therapeutics, Senseye Inc., Precisement Health, Autobahn Therapeutics Inc., EMA Wellness, Denovo Biopharma LLC, Alvogen, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Reunion Neuroscience, Kivira Health, Inc., Wave Neuroscience, Patient Square Capital LP, Invisalert Solutions Inc. and Neurocrine Biosciences, LLC. C.B.N. owns the following patents: method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US patent no. 6,375,990B1), method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay (US patent no. 7,148,027B2) and compounds, compositions, methods of synthesis and methods of treatment (CRF receptor binding ligand) (US patent no. 8,551, 996 B2). C.B.N. owns stock in Corcept Therapeutics Company, EMA Wellness, Precisement Health, Relmada Therapeutics Inc., Signant Health, Galen Mental Health LLC, Kivira Health, Inc., Denovo Biopharma LLC and Senseye Inc. A.E. reports salary and equity from Alto Neuroscience and equity in Mindstrong Health. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Data driven dimensionality and dissimilarity of dimension compositions of the latent space.

As the degree of sparsity increases, the latent space dimensions derived from both the L0-regularized (a) and L1-regularized (b) framework first exhibit a shrinkage of degree of freedom (decrease in number of dimensions), demonstrating the data driven dimensionality property that the framework can judge on its own whether a feature is adequately informative to be included in the sparse latent space. However, while the latent dimensions derived with L0-regularization show decent dissimilarity with each other (as quantified by their pairwise cosine similarity), the dimensions derived with L1-regularization gradually converge. After the dimensionality reaches a relative stable number, the L0-regularized framework further enhance the degree of orthogonality across dimensions, while the L1-regularized counterpart further aggregates information from dimensions and emphasizes the dominant dimension. Together, the differences in the properties of latent space demonstrate the unique advantage of L0-regularized framework over its L1-regularized counterpart — the L0-regularization imposes penalty on the occurrence of features in dimensions, especially the features with contribution to multiple dimensions, therefore yielding distinct dimensions with decent dissimilarity with each other. The sparsity parameters (\({\lambda }_{{fusion}}\) and \({\lambda }_{{pred}}\)) are harmoniously adjusted and kept same for L0- and L1-regularization. The colormap of latent space shows the weights of informative connectivity features with respect to each of the latent dimensions. The blankness in the rightmost part of latent space is the eliminated dimensions that are automatically set to zero vectors by the framework due to their inadequate informativeness. The latent space of one cross-validation fold is shown for each regularization paradigm as the representative example.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–11.

Supplementary Data

Appendix A.

Supplementary Data

Appendix B.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, X., Zhao, K., Fonzo, G.A. et al. Generalizable structure–function covariation predictive of antidepressant response revealed by target-oriented multimodal fusion. Nat. Mental Health 4, 85–101 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00541-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00541-0