Abstract

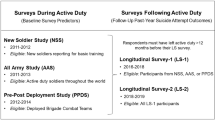

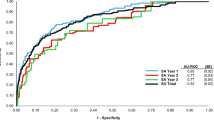

US veterans are significantly more likely than civilians to die by suicide. Machine-learning models have been developed to target high-risk transitioning service members for suicide prevention interventions to reduce veteran suicides. These models are suicide method-agnostic. However, firearms are involved in most veteran suicides, and firearm-specific preventions exist. We used data from US Army veterans from 2010 to 2019 (N = 800,579) to develop and compare firearm-specific machine-learning models with a method-agnostic model to predict firearm suicides among transitioning Army veterans up to 10 years after discharge. The models performed comparably overall (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.710–0.708; integrated calibration index = 0.0003–0.0005% for firearm-specific and method-agnostic models, respectively), with the best model depending on the intervention threshold. Results from this study show the method-agnostic model was better at predicting firearm suicides at the highest intervention threshold, whereas the firearm-specific model was better at lower thresholds. When considering fairness with respect to sex and race/ethnicity, the firearm-specific model was best across all thresholds. Thus, model choice depends on weighing numerous factors, and optimal thresholds might differ for coordinated firearm-specific and method-agnostic interventions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$79.00 per year

only $6.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

STARRS-LS Wave 1, Wave 2 and Wave 3 data, as well as data from the earlier Army STARRS New Soldier Study (NSS), All Army Study (AAS) and Pre and Post Deployment studies (PPDS), are available through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/35197). STARRS-LS and Army STARRS data are restricted from general dissemination, meaning that a confidential data use agreement must be established before access. Researchers interested in gaining access to the data can submit their applications via ICPSR’s online Restricted Contracting System. Guidelines for applying for access to this data can be found under the data and documentation tab at the above URL. The STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) data are not available for public release.

Code availability

Code used to produce the statistical output can be located via https://osf.io/csm59/. Because the data used in this study are not publicly available and require DoD clearance to access, we cannot post the source code used to read in the Army administrative data (which requires DoD clearance) and create the 1,700+ variables used in this analysis. However, we have provided detailed appendices about each of the variables used as covariates in the analyses and have provided here the statistical code for generating the tables and figures.

References

WISQARS Fatal and Nonfatal Injury Reports (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2024); https://wisqars.cdc.gov/reports/

Department of Defense Annual Report on Suicide in the Military: Calendar Year 2021 Vol. 2024 (Department of Defense, 2022); https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/2022%20ASR/FY21%20ASR.pdf?ver=soZ94xt2yM905wj9TbwI3g%3d%3d%E2%80%8B

2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2023); https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

Ravindran, C., Morley, S. W., Stephens, B. M., Stanley, I. H. & Reger, M. A. Association of suicide risk with transition to civilian life among US Military service members. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2016261 (2020).

Shen, Y.-C., Cunha, J. M. & Williams, T. V. Time-varying associations of suicide with deployments, mental health conditions, and stressful life events among current and former US Military personnel: a retrospective multivariate analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1039–1048 (2016).

VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide Version 3.0 (US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2024); https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/mh/srb/

Veterans Transitioning from Service (US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2024); https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/transitioning-service/resources.asp

Nock, M. K., Ramirez, F. & Rankin, O. Advancing our understanding of the who, when, and why of suicide risk. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 11–12 (2019).

Kennedy, C. J. et al. Predicting suicides among US Army soldiers after leaving active service. JAMA Psychiatry 18, 1215–1224 (2024).

Kearns, J. C. et al. A practical risk calculator for suicidal behavior among transitioning US Army soldiers: results from the Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers-Longitudinal Study (STARRS-LS). Psychol. Med. 53, 7096–7105 (2023).

Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Veterans Affairs & Secretary of Homeland Security. Joint Action Plan for Supporting Veterans During their Transition from Uniformed Service to Civilian Life (US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018); https://www.va.gov/opa/docs/joint-action-plan-05-03-18.pdf

Those Who Serve: Addressing Firearm Suicide Among Our Nation’s Veterans (Everytown Research & Policy, 2024); https://everytownresearch.org/report/those-who-serve/

Kaczkowski, W. et al. Notes from the field: firearm suicide rates, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2019–2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 72, 1307–1308 (2023).

Stanley, I. H., Embrey, E. P. & Bebarta, V. S. Actualizing military suicide prevention through digital health modernization. JAMA Psychiatry 81, 1173–1174 (2024).

Raines, A. M. et al. Comparing the interactions of risk factors by method of suicide among veterans: a moderated network analysis approach. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 133, 273–284 (2024).

Ammerman, B. A. & Reger, M. A. Evaluation of prevention efforts and risk factors among veteran suicide decedents who died by firearm. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 50, 679–687 (2020).

LeardMann, C. A. et al. Prospective comparison of risk factors for firearm suicide and non-firearm suicide in a large population-based cohort of current and former US service members: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 36, 100802 (2024).

Vickers, A. J., van Calster, B. & Steyerberg, E. W. A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagn. Progn. Res. 3, 18 (2019).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777 (Curran Associates, 2017); https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3295222.3295230

Kaufman, E. J., Song, J., Xiong, R., Seamon, M. J. & Delgado, M. K. Fatal and nonfatal firearm injury rates by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2019 to 2020. Ann. Intern. Med. 177, 1157–1169 (2024).

Paashaus, L. et al. From decision to action: suicidal history and time between decision to die and actual suicide attempt. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 28, 1427–1434 (2021).

Cai, Z., Junus, A., Chang, Q. & Yip, P. S. The lethality of suicide methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 300, 121–129 (2022).

Constans, J. I., Houtsma, C., Bailey, M. & True, G. The Armory Project: partnering with firearm retailers to promote and provide voluntary out-of-home firearm storage. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 53, 716–724 (2023).

Kelly, T., Brandspigel, S., Polzer, E. & Betz, M. E. Firearm storage maps: a pragmatic approach to reduce firearm suicide during times of risk. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, 351–353 (2020).

Betz, M. E., Barnard, L. M., Knoepke, C. E., Rivara, F. P. & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. Creation of online maps for voluntary out-of-home firearm storage: experiences and opportunities. Prev. Med. Rep. 32, 102167 (2023).

Extreme Risk Protection Orders (Giffords Law Center, 2024); https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/who-can-have-a-gun/extreme-risk-protection-orders/

Swanson, J. W. et al. Suicide prevention effects of extreme risk protection order laws in four states. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 52, 327–337 (2024).

Miller, M., Zhang, Y., Studdert, D. M. & Swanson, S. Updated estimate of the number of extreme risk protection orders needed to prevent 1 suicide. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2414864 (2024).

Zeoli, A. M., Frattaroli, S., Aassar, M., Cooper, C. E. & Omaki, E. Extreme risk protection orders in the United States: a systematic review of the research. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 8, 485–504 (2025).

Kravitz-Wirtz, N., Aubel, A. J., Pallin, R. & Wintemute, G. J. Public awareness of and personal willingness to use California’s Extreme Risk Protection Order Law to prevent firearm-related harm. JAMA Health Forum 2, e210975 (2021).

Dempsey, C. L. et al. Association of firearm ownership, use, accessibility, and storage practices with suicide risk among US Army soldiers. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e195383 (2019).

Barber, C. W. & Miller, M. J. Reducing a suicidal person’s access to lethal means of suicide: a research agenda. Am. J. Prev. Med. 47, S264–S272 (2014).

Pallin, R., Spitzer, S. A., Ranney, M. L., Betz, M. E. & Wintemute, G. J. Preventing firearm-related death and injury. Ann. Intern. Med. 170, ITC81–ITC96 (2019).

Anestis, M. D., Bryan, C. J., Capron, D. W. & Bryan, A. O. Lethal means counseling, distribution of cable locks, and safe firearm storage practices among the Mississippi National Guard: a factorial randomized controlled trial, 2018–2020. Am. J. Public Health 111, 309–317 (2021).

Simonetti, J. A., Rowhani-Rahbar, A., King, C., Bennett, E. & Rivara, F. P. Evaluation of a community-based safe firearm and ammunition storage intervention. Inj. Prev. 24, 218–223 (2018).

National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2023); https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

Stanley, I. H. et al. Project Safeguard: challenges and opportunities of a universal rollout of peer-delivered lethal means safety counseling at a US Military installation. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 54, 489–500 (2024).

Houtsma, C., Hohman, M., Anestis, M. D., Bryan, C. J. & True, G. Development of a peer-delivered lethal means counseling intervention for firearm owning veterans: peer engagement and exploration of responsibility and safety (PEERS). Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 55, e13138 (2024).

Shenassa, E. D., Rogers, M. L., Spalding, K. L. & Roberts, M. B. Safer storage of firearms at home and risk of suicide: a study of protective factors in a nationally representative sample. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 58, 841–848 (2004).

Betz, M. E. et al. Firearm suicide prevention in the US Military: recommendations from a national summit. Mil. Med. 188, 231–235 (2023).

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2011. Pub. L. No. 111-383 (US Congress, 2011); https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4638

Haviland, M. J. et al. Assessment of county-level proxy variables for household firearm ownership. Prev. Med. 148, 106571 (2021).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 22, 267–275 (2013).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (tripod) the tripod statement. Circulation 131, 211–219 (2015).

Efron, B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 414–425 (1988).

Bansal, A. & Pepe, M. S. Estimating improvement in prediction with matched case-control designs. Lifetime Data Anal. 19, 170–201 (2013).

Jiang, T. et al. Using machine learning to predict suicide in the 30 days after discharge from psychiatric hospital in Denmark. Br. J. Psychiatry 219, 440–447 (2021).

Saxe, G. N., Ma, S., Ren, J. & Aliferis, C. Machine learning methods to predict child posttraumatic stress: a proof of concept study. BMC Psychiatry 17, 223 (2017).

Polley, E. C., LeDell, E., Kennedy, C., Lendle, S. & van der Laan, M. J. SuperLearner: super learner prediction (R package). GitHub https://github.com/ecpolley/SuperLearner (2024).

Polley, E. C., Rose S., & van der Laan M. J. in Targeted Learning: Causal Inference for Observational and Experimental Data (eds Rose, S. & van der Laan, M. J.) 43–66 (Springer, 2011).

LeDell, E., van der Laan, M. J. & Petersen, M. AUC-maximizing ensembles through metalearning. Int. J. Biostat. 12, 203–218 (2016).

Kabir, M.F. & Ludwig, S.A. Enhancing the performance of classification using super learning. Data-Enabled Discov. Appl. 3, 5 (2019).

Kennedy, C. Guide to SuperLearner (University of California, 2017); https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SuperLearner/vignettes/Guide-to-SuperLearner.html

Wright, M. N. & Ziegler, A. Ranger: a fast implementation of random forests for high dimensional data in C++ and r. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v077.i01 (2017).

Niculescu-Mizil, A. & Caruana, R. Predicting good probabilities with supervised learning. In Proc. 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning 625–632 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2005); https://doi.org/10.1145/1102351.1102430

Jiang, X., Osl, M., Kim, J. & Ohno-Machado, L. Calibrating predictive model estimates to support personalized medicine. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 19, 263–274 (2012).

Hanley, J. A. & McNeil, B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143, 29–36 (1982).

Davis, J. & Goadrich, M. The relationship between precision-recall and ROC curves. In Proc. 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning 233–240 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2006); https://doi.org/10.1145/1143844.1143874

Austin, P. C. & Steyerberg, E. W. The integrated calibration index (ICI) and related metrics for quantifying the calibration of logistic regression models. Stat. Med. 38, 4051–4065 (2019).

Austin, P. C. & Steyerberg, E. W. Graphical assessment of internal and external calibration of logistic regression models by using loess smoothers. Stat. Med. 33, 517–535 (2014).

Vickers, A.J., Van Calster, B. & Steyerberg, E.W. Net benefit approaches to the evaluation of prediction models, molecular markers, and diagnostic tests. Br. Med. J. 352, i6 (2016).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Making 26, 565–574 (2006).

Van Calster, B. et al. Reporting and interpreting decision curve analysis: a guide for investigators. Eur. Urol. 74, 796–804 (2018).

Barocas, S., Hardt, M. & Narayanan, A. Fairness and Machine Learning: Limitations and Opportunities (MIT Press, 2023); https://fairmlbook.org/

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013); https://support.sas.com/software/94/

R Core Team: The R Project for Statistical Computing (R Foundation, 2021); https://www.r-project.org/

Acknowledgements

The Army STARRS Team consists of co-principal investigators R. J. Ursano (Uniformed Services University) and M. B. Stein (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); site principal investigators J. Wagner (University of Michigan) and R. C. Kessler (Harvard Medical School); Army scientific consultant/liaison K. Cox (Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs)). Other team members are P. A. Aliaga (Uniformed Services University); D. M. Benedek (Uniformed Services University); L. Campbell-Sills (University of California San Diego); C. L. Dempsey (Uniformed Services University); C. S. Fullerton (Uniformed Services University); N. Gebler (University of Michigan); M. House (University of Michigan); P. E. Hurwitz (Uniformed Services University); S. Jain (University of California San Diego); T.-C. Kao (Uniformed Services University); C. J. Kennedy (Massachusetts General Hospital); L. Lewandowski-RompsD (University of Michigan); A. Luedtke (University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center); H. H. Mash (Uniformed Services University); J. A. Naifeh (Uniformed Services University); M. K. Nock (Harvard University); N. A. Sampson (Harvard Medical School); R. Shor (Uniformed Services University); and A. M. Zaslavsky (Harvard Medical School). C.H. and E.R.E. were supported in part by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service (CSR&D) VA-STARRS Researcher-in-Residence Program (project SPR-002-24F). C.J.K. was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH135131). Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001-15-2-0004). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense or the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. and R.C.K. were responsible for the study concept and design. C.J.K., H.L., N.A.S., J.C.G., B.P.M. and R.C.K. acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. C.H., C.J.K., H.L. and R.C.K. were involved in drafting of the manuscript. C.J.K. and H.L. conducted the primary statistical analyses. B.P.M., J.W., M.B.S., R.J.U. and R.C.K. obtained funding. E.R.E., N.A.S., J.C.G., B.P.M., M.K.N., J.W., M.B.S., R.J.U. and R.C.K. provided technical, administrative and material support. C.J.K., N.A.S., J.C.G., B.P.M., M.K.N., J.W., M.B.S., R.J.U. and R.C.K. provided study supervision. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

In the past 3 years, R.C.K. was a consultant for Cambridge Health Alliance, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Child Mind Institute, Holmusk, Massachusetts General Hospital, Partners Healthcare, Inc., RallyPoint Networks, Inc., Sage Therapeutics and University of North Carolina. He has stock options in Cerebral Inc., Mirah, PYM (Prepare Your Mind), Roga Sciences and Verisense Health. In the past 3 years, M.B.S. received consulting income from Actelion, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Aptinyx, atai Life Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bionomics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Clexio, EmpowerPharm, Engrail Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Roche/Genentech. He has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals and EpiVario. He is paid for his editorial work on Biological Psychiatry (deputy editor) and UpToDate (co-editor-in-chief for psychiatry). No other disclosures reported.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Jim Schmeckenbecher and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1, Tables 1–6, Measures and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Houtsma, C., Kennedy, C.J., Liu, H. et al. Predicting firearm suicide among US Army veterans transitioning from active service. Nat. Mental Health 4, 125–135 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00559-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00559-4