Abstract

Population growth and urbanization are driving the demand for centralized wastewater treatment, a primary source of N2O and CH4 emissions. We have conducted the first comprehensive assessment of CH4, N2O and NH3 emissions across diurnal, day-to-day and seasonal scales at 96 US water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) that collectively treat 9% of US centralized wastewater. Facility-level emissions were scaled to the national level using a probabilistic approach. Here we show that the measured emissions were 1.9 times higher for N2O (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.3–2.6) and 2.4 times higher for CH4 (CI: 1.9–2.9) than current US inventories. Considering the cumulative climate impacts of CH4 and N2O, the top 10% of emitters contributed 74% of the carbon footprint, with the top half contributing 98%, highlighting priorities for mitigation. Although detected at only a small fraction of facilities, measurements of NH3 emissions (86 kt yr−1 in the USA) suggest WRRFs are an overlooked source of urban NH3. Finally, the contribution of centralized wastewater treatment to global greenhouse gas emissions will increase 2- to 17-fold by 2100 under future scenarios. Overall, greater consideration of wastewater treatment emissions is needed to reach sustainability targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Wastewater treatment uses biological processes to remove contaminants and produce clean water, but current processes also emit methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), the two most important anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs) after carbon dioxide (CO2). With 100-year global warming potentials (GWP100) of 28 and 265, respectively, CH4 and N2O are collectively responsible for 22% of the warming since 18501. While CH4 mitigation has been a target of recent environmental legislation to fight climate change due to its short lifetime (~9 years)2, N2O emitted into the atmosphere will remain there, on average, for 116 years3, posing long-lasting impacts on climate and stratospheric ozone depletion. Wastewater treatment is a primary urban source of N2O and CH4. In addition, wastewater often contains high concentrations of ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4+), which can volatilize directly and/or be produced during the treatment of extracted solids4. Gaseous NH3 is the primary base in the atmosphere and reacts quickly with acidic compounds (for example, sulfuric acid and nitric acid) to create fine particles, degrading air quality and negatively impacting human health5 and ecosystems6,7.

Current national estimates of wastewater-derived emissions of CH4 in the USA are underestimated by about a factor of two8,9, while those of NH3 and N2O emissions are highly uncertain10. These estimates are largely based on the guidelines of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which recommend the use of emission factors (EFs), conventionally defined as emissions normalized by influent 5-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) loading for CH4 and influent total nitrogen (TN) loading for N2O and NH3 (refs. 4,11,12). For all species, the measurements contributing to these recommended EFs are limited to a few water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) that may not be representative of those in the USA or the world, more generally. For example, the IPCC-recommended N2O EF for centralized aerobic treatment, the most common treatment type in the USA, varies over three orders of magnitude13,14. Indeed, this variability manifests itself in the uncertainty of national emissions estimates. For example, the current US inventory of N2O emissions from WRRFs reported a 95% confidence interval ranging from 9.9 to 47.1 MtCO2-equivalent (MtCO2e), with an upper bound nearly three times the inventory value10. Nation- and city-wide net-zero and sustainability plans must, therefore, consider the impact of wastewater treatment as the world seeks enhanced living standards and economic growth amidst a growing urban population.

Many previous emission measurement efforts have generally targeted individual processes at single WRRFs, offering insight into process-level variations, such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen concentrations, biochemical reactions, flow variability, and their relationship with gaseous emissions15,16,17,18, as well as highlighting the importance of seasonal and diurnal variabilities in quantifying a facility’s footprint18,19. Such targeted sampling, however, often neglects unknown and/or fugitive emissions throughout the plant, leading to potential biases in facility-integrated emissions estimates20,21. Therefore, more recent studies used tracer-release methods20,22, for instance, to capture these facility-integrated emissions. These methods, however, require many human hours and on-site access, making its scalability unfeasible.

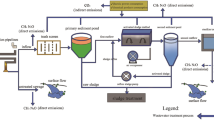

Given the impact of environmental factors and operational conditions on the formation and emission of these gases during the wastewater treatment process9,23, we have developed a mobile-based measurement platform to capture a representative sample of CH4, N2O and NH3 emissions from WRRFs. When used in combination with inverse Gaussian plume dispersion methods and Bayesian inference, this method can efficiently quantify facility-integrated emissions and their associated uncertainties8. Compared with other monitoring techniques, such as off-gas and chamber measurements, this mobile-based approach incorporates, indiscriminately, emissions from all sources in a facility. Furthermore, the efficiency and adaptability of this method allowed us to examine a wide range of WRRFs that differ in size, geographic location and treatment process across various diurnal and seasonal timescales.

Although these measurements are, individually, a snapshot of emissions in time, statistics across a large sample converge on the population mean. As such, this method has allowed us to build statistically robust estimates of CH4, N2O and NH3 emissions from the US wastewater treatment sector for the first time. While wastewater treatment is an important source of CO2, mainly through indirect emissions from energy consumption, direct emissions of CO2 were not quantified in this study due to contamination from on-road sources. While traditional WRRFs have focused on removing carbon, nitrogen and other contaminants from wastewater, many are in the process of transformation to also recover energy and resources with the goal of achieving a net-zero emission, circular water economy. Therefore, more robust inventories of GHG and NH3 emissions could be used to help develop effective mitigation policies towards realizing these sustainability goals.

Facility measurements

We measured atmospheric mole fractions of the target species downwind of a total of 109 WRRFs, with treatment capacities ranging from less than 3 × 102 m3 d−1 to more than 2 × 106 m3 d−1 (<0.1 to >100 million gallons per day (MGD)), across eight states in the USA, primarily in the Northeast (n = 85) and California (n = 18), with several in the Midwest (n = 6; Supplementary Information, section 1). In total, the sampled WRRFs treat, on average, around 1.1 × 107 m3 d−1, or about 8.8% of the total flow to US centralized domestic WRRFs (1.3 × 108 m3 d−1 according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA))24. A total of 3,307 cross-plume transects passed quality control across the 109 facilities. We conducted quarterly analyses at a subset of 37 facilities and one diurnal study (roughly every 2 hours for 24 hours) to quantify seasonal and diurnal variabilities, respectively. This sampling strategy of incorporating many facilities over varying time spans was used to capture the well-established variability of GHG emissions, particularly those of N2O, and biases associated with short-term measurements given this variability23,25,26. After all of the quality control measures needed for successful quantification of facility-level emissions were applied individually for each gas, we quantified the emissions of at least one gas from 96 WRRFs. This dataset comprises measured emissions data from the largest number of facilities incorporated into a single study so far, and greater than the number of facilities used to inform the current guidelines of the IPCC (14 and 30 facilities for CH4 and N2O, respectively)27. Moreover, the number of facilities sampled is greater than the number considered in two recent review papers on CH4 (ref. 9) and N2O (ref. 23), which explored literature data on 101 and 51 facilities, respectively. Finally, only two previous studies4,28 have investigated facility-integrated emissions of NH3, and therefore this work markedly expands the available dataset. In summary, this study provides the most comprehensive dataset so far in terms of the number of facilities and temporal scales spanned.

Quantifying emissions and emission factors

The measured emission rates (ERs) from the 96 successfully sampled WRRFs exhibited high variability and skewness, ranging over several orders of magnitude independent of the gas that was considered (Fig. 1). For instance, facility-averaged CH4 ERs ranged from 0.02 to 224 gCH4 s−1 (1.7 × 10−3 to 19.4 tCH4 d−1), while N2O emissions spanned from 0.002 to 28 gN2O s−1 (1.7 × 10−4 to 2.4 tN2O d−1) and NH3 emissions varied from 0.002 to 33 gNH3 s−1 (1.7 × 10−4 to 2.9 tNH3 d−1). Large site-to-site variability with respect to influent flow rate, influent nutrient concentration, treatment type and so on, contributes to these orders of magnitude ranges for each gas.

a–c, ERs of CH4 (n = 94; a), N2O (n = 86; b) and NH3 (n = 80; c) as functions of influent BOD5 loading for for CH4 and TN loading for N2O and NH3. d, The number of successfully sampled facilities (n = 96) categorized by secondary treatment type, along with the subset of each that treats solids using AD. A2O, anaerobic/anoxic/oxic; AAS, advanced activated sludge; CAS, conventional activated sludge; MBR, membrane bioreactor; OD, oxidation ditch; RBC, rotating biological contactor; SBR, sequencing batch reactor; USG, unspecified suspended growth.

Facility-averaged ERs tended to scale with the respective influent nutrient loading (BOD5 for CH4 and TN for N2O and NH3), suggesting that the current normalization of emissions by the respective loading data is valid. However, for a given loading, the measured emissions still varied by more than two orders of magnitude in some cases, highlighting the degree of site-to-site variability. The WRRFs were categorized according to their secondary treatment type (Supplementary Information, section 2). However, due to the small sample size for each type, as well as the uncertainty of what treatment was actually occurring at each facility, we cannot conclude any significant relationship between treatment process and measured emissions.

To translate measured ERs into EFs, we developed a database of influent characteristics for each sampled facility using a tiered approach in which the relevant data were obtained sequentially from discharge monitoring reports, open records requests, custom survey responses, facility websites, state databases and the US EPA Clean Water Needs Surveys (CWNS) (Supplementary Information, section 2). Through this approach, we obtained site-specific BOD5 and TN data for 76 and 22 of the 96 successfully quantified WRRFs, respectively, for each observational period. To quantify the EFs from the remaining sites (that is, those without known loading data), where only BOD5 data were available, a ratio-based approach was used, and where neither BOD5 nor TN data were available, default values of 200 mgBOD5 l−1 and 35 mgTN l−1 were assumed. No sites with only TN data were sampled.

Compared with previous measurement studies, this is the largest single dataset (n = 96) of measured EFs from WRRFs. The mean (minimum, 25th, 50th, 75th percentiles, maximum) facility-averaged EFs were 0.067 (0.0005, 0.012, 0.034, 0.089, 0.54) gCH4 gBOD5−1 (n = 94), 0.052 (0.0001, 0.003, 0.009, 0.036, 1.8) gN2O gTN−1 (n = 86) and 0.021 (0.0001, 0.001, 0.003, 0.007, 0.69) gNH3 gTN−1 (n = 80). The mean EFs of CH4 and N2O are 3.7 and 2.1 times greater than the default IPCC EFs of 0.018 gCH4 gBOD5−1 (centralized aerobic, excluding anaerobic digestion and discharge) and 0.025 gN2O gTN−1 (centralized aerobic treatment, excluding discharge), respectively27. As has been observed in previous studies9,18,29, anaerobic digestion (AD) can lead to drastically increased CH4 emissions at a given facility, so comparison with this default IPCC value must be taken in that context. The resulting EFs were highly variable for each of the three gases and their respective distributions exhibited high skewness, each with a few facilities that exhibited large emissions relative to the nutrients treated. For instance, the mean N2O EF (0.052 gN2O gTN−1) was fivefold greater than the median N2O EF (0.009 gN2O gTN−1). Among this high variability, no definitive relationship could be established between EFs and secondary treatment type (Supplementary Information, section 3), in large part due to the small sample size and uncertainty in facility treatment processes.

Such variability was also observed in previous studies in which several facilities were measured. For instance, Ahn et al.17 observed N2O EFs ranging from 1 × 10−4 to 1.8 × 10−2 gN2O g−1 total Kjeldahl nitrogen across 12 US WRRFs, whereas Delre et al.30 measured EFs from <1 × 10−3 to 5.2 × 10−2 gN2O gTN−1 and 1.6 × 10−4 to 9.1 × 10−2 gCH4 g−1 chemical oxygen demand from five Scandinavian WRRFs. This largely unexplainable range of EFs creates a major challenge in generalizing measured emissions to larger-scale applications, such as inventory generation.

Finally, the measured NH3 EFs were in general agreement with those reported in the two only other known studies of full-scale WRRF measurements (9 × 10−4 gNH3 gTN−1 (ref. 4), 3 × 10−3 gNH3 gTN−1 (ref. 28), assuming 4,750 gTN PE−1 yr−1). Samuelsson et al.4 found that the primary source of NH3 emissions at the single measured facility was from sludge treatment, a process that can vary widely between facilities, from dewatering and off-site disposal to on-site composting and/or digestion. The relationship between solids treatment and NH3 emissions may partially explain the wide range of measured NH3 EFs reported here.

Previous work has shown that facilities with AD are responsible for around 72% of US sector-wide CH4 emissions, despite treating only 55% of US wastewater9. As has been noted in previous studies, significant CH4 emissions come from leaks in digesters and incomplete biogas burning29,31. To understand the extent of CH4 emissions from WRRFs with and without AD, we investigated facilities that exclusively use conventional activated sludge (CAS) as their secondary biological treatment process to minimize the influence of other treatment differences on the observed variability of CH4. Facilities using only CAS were chosen as a case study because they are the most abundant both in our study (Fig. 1d) and across the USA. In total, we successfully quantified CH4 EFs from 47 CAS facilities, 37 of which we could assign to a specific solids treatment process (Supplementary Information, section 2). Of these, we found that facilities with AD (n = 22) had a mean CH4 EF of 0.071 gCH4 gBOD5−1, while facilities with other known solids treatment (n = 15) had a mean EF of 0.028 gCH4 gBOD5−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, facilities with AD emit 2.5 times more CH4 relative to waste treated than those without AD (two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.03).

Updated US emissions inventory

We scaled our measurements to the sector using a statistical approach to incorporate uncertainty from all variables (Fig. 2). The measurement-informed CH4 emissions inventory (Fig. 2a) for the US domestic wastewater sector is 17.9 MtCO2e yr−1 (95% confidence interval (CI): 14.2–21.9 MtCO2e yr−1), which is around 2.4 times greater than the US EPA inventory for domestic wastewater emissions, excluding septic systems (7.6 MtCO2 yr−1)10. The EPA inventory was created following IPCC guidelines, which were developed primarily from non-US WRRFs and thus may not be representative of US facilities. In addition, the updated inventory reported here is 64% greater than that of Song et al.9 and 38% greater than that of Moore et al.8 (after correcting for the use of different GWP100), which analysed only a subset (63 facilities and 95 observational periods) of the dataset presented here (94 facilities and 305 observational periods). Compared with the previous estimate, our results exhibit a greater skewness due to the incorporation of several large (>10 MGD) facilities with high EFs, which increased the overall sector-wide total.

a–c, Probability density functions (PDFs) of US sector-wide domestic wastewater treatment emissions of CH4 (a), N2O (b) and NH3 (c). d, PDF of combined direct GHG emissions of CH4 and N2O. The dashed black lines and grey shaded regions in a, b and d depict the means and 95% CIs from the US EPA inventory for 202210, respectively, and the orange lines and shaded regions depict the means of the updated, measurement-informed inventory and associated 95% CIs, respectively.

Similarly, sector-wide emissions of N2O (Fig. 2b) are 31.5 MtCO2e yr−1 (95% CI: 20.3–41.7 MtCO2e yr−1), 1.9 times greater than the US EPA inventory of domestic wastewater emissions, excluding effluent emissions (16.2 MtCO2e yr−1), although within the 95% CI of 9.9–47.2 MtCO2e yr−1. By contrast, Song et al.26 found N2O emissions to be 11.6 MtCO2e yr−1 (or 75% of the current US EPA value) using a data mining and statistical upscaling technique. In addition, the results of Song et al.26 did not include emissions from side-stream treatment, which may contribute significantly to the emissions measured at individual facilities. The present study provides the largest and most comprehensive dataset of measured emissions from wastewater facilities, highlighting the high site-to-site variability in EFs that lead to a heavily skewed probability distribution, yet more emissions data are needed to precisely quantify sector-wide emissions in the USA. Finally, the combined climate effect of CH4 and N2O lead to direct GHG emissions of 49.8 MtCO2e yr−1 (95% CI: 36.3–65.5 MtCO2e yr−1; Fig. 2d), dominated by N2O emissions, similar to the findings of Parravicini et al.32.

NH3 emissions from the US domestic wastewater sector (Fig. 2c) are 86 ktNH3 yr−1 (95% CI: 28–143 ktNH3 yr−1). Because only 12 of the 80 successfully measured WRRFs exhibited detectable NH3 emissions, a statistical approach was used to assess values below the detection limit, defined for each transect using the measured mole fraction variability (see Methods). A sensitivity study (Supplementary Information, section 4) showed that, by instead assuming that all emissions below the detection limit were precisely 0 gNH3 s−1, sector-wide NH3 emissions were only marginally different (73 ktNH3 yr−1, 95% CI: 28–137 ktNH3 yr−1). The skewed distribution of EFs drives the uncertainty of the estimate. Although very few measurements of NH3 emissions have been conducted at the plant scale, our estimate is more than two orders of magnitude greater than current EPA estimates (<1 ktNH3 yr−1) and the same order of magnitude as on-road non-diesel light-duty vehicle emissions (77 ktNH3 yr−1)33. Thus, wastewater treatment may be an underestimated and overlooked NH3 source in urban regions, where reactions with co-located sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides create particulates and degrade air quality.

In all three cases, the measurement-derived emissions are greater than the current inventories. In part, this is due to the plant-integrated measurement approach, which captures all emissions regardless of knowledge of source location. For example, while aeration tanks should not produce CH4, poor aeration may create anaerobic conditions that lead to CH4 production and emission. The extent to which unintended or unrecognized emissions contribute to our greater measured emissions compared with the inventories is unclear.

We investigated the notion of super-emitters by calculating the carbon footprint of each facility using the measured CH4 and N2O emissions (n = 84). The carbon footprint is defined as the GWP100-weighted summation of CH4 and N2O emissions in CO2 equivalents. When comparing the facility-level EFs of both gases, facilities with greater CH4 EFs tended to exhibit greater N2O EFs (Fig. 3a). Because CH4 and N2O follow different formation pathways, this suggests that inefficiencies at individual facilities are generally not isolated to individual processes.

a, Comparison of the EFs (n = 84) of N2O and CH4, as normalized by influent TN and BOD5, respectively. The secondary treatment process and average flow rate of each facility are depicted, as well as those with and without AD. The top 10% of emitters (n = 9) are denoted by ×. The horizontal and vertical dashed lines represent the 75th percentiles of the N2O (0.036 gN2O gTN−1) and CH4 (0.089 gCH4 gBOD5−1) EFs, respectively. b, Cumulative distribution of the carbon footprint and flow across the measured sites. The vertical dashed black line depicts the top 9 (10.7%) plants, and the horizontal blue and orange dashed lines represent the cumulative fraction of flow and carbon footprint contributed by the top 9 (10.7%) plants, respectively. The carbon footprint is defined as the GWP of each gas (28 for CH4 and 265 for N2O) multiplied by the ER of that gas (\(Q_{{\rm{CH}}_4}\) and \(Q_{{\rm{N}}_{2}{\rm{O}}}\)).

The cumulative distribution of the carbon footprint across the measured sites (Fig. 3b) reveals that the top 11% of facilities (n = 9) contribute to 74% of the total measured carbon footprint. This is more skewed than the distribution of facilities by flow, which shows that the top 11% of facilities treat only 62% of the measured flow. Each of these nine facilities used AD and the secondary treatments were CAS, anaerobic/anoxic/oxic and step feed. While the treatment process used may contribute to these increased emissions relative to influent nutrient content, the wide range of EFs for each of the sampled treatment categories suggest that there are other driving factors (Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

The top 50% of facilities are responsible for more than 98% of the measured carbon footprint. Therefore, because of the general correlation between emissions and treatment capacity, mitigation efforts are best focused on larger facilities, which should also have more resources for such practices. For example, the nine largest facilities, which collectively treat 175 ktBOD5 yr−1 and 31 ktTN yr−1, together average EFs of 0.17 gCH4 gBOD5−1 and 0.30 gN2O gTN−1. If the EFs from these facilities were mitigated to equal the median EFs (that is, 0.034 gCH4 gBOD5−1 and 0.009 gN2O gTN−1), the apparent emissions avoided would equate to 23.8 ktCH4 yr−1and 9 ktN2O yr−1 (3.1 MtCO2e yr−1 combined). Nonetheless, by ignoring the top nine emitters and scaling the emissions of the remaining facilities to the national sector-wide total as above, the results from a sensitivity study maintain that current inventories are still underestimated for all three gases (Supplementary Information, section 5).

Finally, we identified super-emitter facilities, here defined as those that emit more than the 75th percentile in both CH4 per influent BOD5 (0.089 gCH4 gBOD5−1) and N2O emissions per TN treated (0.036 gN2O gTN−1; Supplementary Information, section 5). These facilities contribute a large and disproportionate amount to the sector’s carbon footprint, especially when such high EFs are associated with large volumes of treated waste, and are therefore high priority with regards to the mitigation of sector-wide emissions. It is likely that high-throughput facilities, owing to their greater resources, may use certain treatment processes that contribute to greater nutrient removal and possibly greater associated emissions.

Discussion and conclusions

As global populations grow and become more urbanized, demand for centralized wastewater treatment will increase. The removal of organics and nitrogen from the wastewater stream is necessary to meet water quality standards and improve living standards throughout the world. However, CH4, N2O and NH3 are formed and/or released during the wastewater treatment process in varying amounts, depending on a myriad of factors that remain unclear. In other words, environmental efforts are currently focused on local effects, largely neglecting the emissions of long-lived gases (CH4 and N2O) that contribute to detrimental global effects. If our results are representative, domestic WRRFs alone are responsible for 2.5%, 8.1% and 1.6% of total CH4, N2O and NH3 emissions in the USA, respectively (currently reported as 1.1%, 4.1% and <1%; Table 1).

Our US N2O emissions estimates are greater than those of the US EPA, in the opposite direction of the findings of Song et al.26, who categorized and analysed measurements from existing literature. In addition to the inclusion here of all processes within the footprint of each sampled facility, a potential explanation for this may be that most measurement studies examine select components at facilities and probably do not capture unintended or unexpected sources from inefficient operational components elsewhere. For example, Yver Kwok et al.20 measured component-level CH4 emissions totalling only around 8% of the total emissions measured using off-site methods; a similar aggregation of component-level emissions studies has been shown to underestimate emissions from the oil and gas sector34. There may also be reasons for the optimal operation of the examined components during the time of measurement as they are the focus of a monitoring study, and studies requiring on-site permission may be biased towards those facilities with better operations and management. Similar operational biases have been observed in measured emissions from oil and gas operations35.

N2O emissions from wastewater treatment are increasing both in the USA (15% per decade)10 and globally (9% per decade)36, especially in the context of increasing implementation of biological nitrogen removal by more facilities, while CH4 emission trends are more complicated, in part due to the transition from decentralized to centralized treatments. When coupled with increases in renewable energies, direct GHG emissions from the wastewater sector will become even more important in the net-zero plans of cities. For instance, we estimate that the relative contribution of wastewater treatment to New York City’s overall emissions will increase fivefold by 2050 (1.3% to 7%) using reported projections of population and GHG emissions and recalculating WRRF contributions based on our measurements (Supplementary Information, section 6).

According to recent estimates, 48% of wastewater produced globally is released into the environment untreated37. In addition to calls to decrease the amount of untreated wastewater to mitigate GHG emissions38,39, significant population growth is likely, especially in cities, leading to more centralized wastewater treatment. If our results are representative of global facilities and future treatment, we project that the expansion of wastewater treatment and the resulting CH4 and N2O emissions will increase its relative contribution to global GHG emissions 2- to 17-fold by 2100 (Fig. 4), depending on the shared socioeconomic pathway (SSP) and global emissions reduction scenarios (Supplementary Information, section 7). This contrasts with current global efforts (for example, the European Union Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive and China’s 14th Five-Year Plan) to decarbonize the wastewater treatment sector. While we caution that only US WRRFs were considered in this global analysis and future work is needed to examine the representativeness of these results in the context of WRRFs globally, we acknowledge that the IPCC-based methodologies are particularly suspect, given their extrapolation of data from only 14 and 30 facilities for CH4 and N2O, respectively.

a, Projections of direct CH4 and N2O emissions from global centralized wastewater treatment under the five shared SSPs as defined by the IPCC. The lines represent expected values and the shaded areas denote 95% CIs. b, Proportion of projected global emissions direct from centralized wastewater treatment under the five SSPs, considering a scenario of future pledges and international targets (Supplementary Information, section 7). The bars span the 95% CIs of a Monte Carlo simulation and the colours correspondto the legend in a (Supplementary Information, section 7).

The information available at the facility level is insufficient to explain the observed site-to-site and day-to-day variability in emissions from the sampled WRRFs. Therefore, we stress the need for more frequent and widespread monitoring efforts, similar to the ongoing work in the oil and gas sector in the USA40, including intensive chemical analyses, that can lead to widespread reporting of facility-level emissions and overall transparency. Furthermore, information on the studied WRRFs at the process level comes, in large part, from the CWNS 2004 and is only partially updated up to 2012 (Supplementary Information, section 2). To make sense of the measured emissions and to recommend treatment processes, it is critical that expanded and more detailed reporting be done on, for instance, specific water and solids treatment processes, the type of waste treated and nutrient removal.

Finally, the emissions measured in this study originate almost exclusively within the footprint of the facility and do not include emissions associated with effluent downstream in receiving waters (for example, from biogeochemical processes and outgassing of dissolved gases, off-site sludge processing). Therefore, while greater nutrient removal may lead to increased emissions at individual WRRFs, longitudinal and life cycle analyses are needed to fully investigate the differences in overall emissions relative to input nutrients. It is crucial to investigate the relationship between wastewater nutrient removal and air emissions to determine environmentally sustainable treatment processes that are mutually beneficial for both air and water.

Methods

Mobile measurements

The mobile laboratory used in this study consisted of high-frequency and high-sensitivity sensors to measure the mole fractions of various trace gases in the atmosphere, mounted about 2 m above ground level on top of an electric vehicle to prevent self-sampling of any possible emissions from the vehicle itself (for example, tyres, fluids or occupant breath). Accompanying meteorological measurements were captured at a height of about 3 m. Under normal operation, the mobile laboratory consisted of the following instruments and the associated measurements were collected:

-

Airmar WX200: air temperature, wind speed and direction, and ambient pressure, 1 Hz

-

LI-COR LI7700: CH4 mole fraction41, 10 Hz

-

LI-COR LI7500: CO2 and water vapour mole fractions, 10 Hz

-

Custom open-path quantum cascade laser (QCL) based sensor42: N2O and carbon monoxide (CO) mole fractions, 10 Hz

-

Custom open-path QCL-based sensor43: NH3 mole fraction, 10 Hz

For the two custom open-path QCL-based sensors, spectroscopic effects related to fluctuations in air temperature were corrected during pre-processing following Pan et al.44. For the LI7700 device, these effects were corrected in real-time by the instrument, as detailed in Burba et al.45.

Emissions quantification

A complete discussion of the method used to quantify facility-integrated emissions from high-frequency mobile-based measurements can be found in ref. 8, a summary of which is provided here. This method has been validated over multiple controlled release experiments8 and is similar to the plume-integrated approach used by Caulton et al.46, which was validated using a large eddy simulation47.

Following Moore et al.8 (section 2.1 and supplementary information section 1 of ref. 8), sampling paths were chosen based on the availability of public roads as well as forecast and actual local winds, such that complete plume traversal was ensured. The background concentrations of the observational periods are defined as the fifth percentile of the measured mole fractions.

The following quality control steps were taken to ensure that individual transects were adequate for source rate inference for a given gas:

-

1.

Transects passed a visual inspection for signals from sources that were not the focus of the current study, such as roadside or underground natural gas leaks, but that might cause narrow but high-magnitude spikes in CH4 (supplementary information section 3 in ref. 8).

-

2.

Transects had plume widths of at least 1 s of consecutive measurements (that is, 10 data points at 10 Hz) above background levels, as defined by the fifth percentile mole fraction during the given observational period.

-

3.

Transects consisted of <20% of ‘not a number’ (NaN) values, assigned during the screening process (supplementary information section 3 in ref. 8).

-

4.

Upon modelling the plume with the associated meteorological parameters (see below), measurements extended cross-wind-wise beyond 10% of the maximum modelled enhancement on both sides of the plume centre (Supplementary Fig. 20).

In addition to these quality control steps, due to instrument availability or failure, not all gases were measured during each observational period. Overall, we sampled 109 sites, with 96 sites passing quality control measures, deeming them ‘successfully sampled’ as we were able to quantify their emissions. Out of the 96 successfully sampled sites, we quantified emissions of CH4, N2O and NH3 from 94, 86 and 80 WRRFs, respectively, after quality control was applied.

Measured enhancements (that is, mole fractions above the fifth percentile background), in addition to in situ measurements and meteorological reanalysis data from each observational period, were used to quantify emissions and their associated uncertainties using a plume-integrated inverse Gaussian plume technique with Bayesian source rate inference8,48,49. Specifically, the Gaussian plume dispersion model was used to predict mole fractions along the measurement path:

where the concentration, C, at a point in space, (x, y, z), is a function of the ER, Q, the mean wind speed, \(\bar{u}\), at a height of 2 m, stability parameters in the horizontal and vertical directions, σy and σz, respectively, and the source height, h, taken to be equal to 2 m.

Both the measured and modelled concentrations were integrated along the path to minimize the impact of atmospheric dispersion variability in the horizontal direction. The measured and modelled concentrations across a wide range of possible ERs were used as inputs to a Bayesian framework, following Bayes’ theorem:

where \(p({Q|}{\bf{C}},{\bf{m}}^{\prime} )\) is the posterior PDF for the ER, Q, based on the information contained in the measured concentrations, C, given other model parameters, m′. \(p\left({\bf{C}}|Q,{\bf{m}}^{\prime} \right)\) is the likelihood function, \({p}_{0}({Q|}{\bf{m}}^{\prime})\) is the prior distribution of model parameters and the denominator, \(p({\bf{C}}|{\bf{m}}^{\prime})\), is the evidence function and simply ensures that the posterior PDF, \(p\left(Q|{\bf{C}},{\bf{m}}^{\prime} \right)\), integrates to unity.

We used an adapted Gaussian form of the likelihood function that includes consideration of the detection limit:

This takes an exponential form if the measured integrated concentration for the jth transect, \({c}_{j}^{\;y}\), is less than the threshold concentration, \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}},\;j}^{\;y}\), calculated as integrated noise equal to three times the background variability in the measured mole fraction, and the Gaussian form otherwise. In other words, where \({c}_{j}^{\;y} < {c}_{{{\rm{th}}},\;j}^{\;y}\), the likelihood function takes the exponential form with a high probability of a low, but non-zero ER. \({c}_{j}^{* y}\left(Q\right)\) is the cross-wind integration of the modelled mole fraction assuming a given value of Q. σe is the noise power and is discussed below. Here, α encompasses the probability of detection (POD) and is given by the equation:

where β is the inverse of the POD. The primary difference between the emission calculation presented here and that used by Moore et al.8 is that previously, a POD of 50% (that is, β = 2) was used for the estimated detection limit for each observational period (supplementary information section 6 in ref. 8). For this study, we adopted a 25% POD (that is, β = 4) at the estimated detection limit, Qth,j, defined as:

which selects the candidate ER, Q, with the integrated model concentration closest to the threshold concentration.

The adoption of a 25% POD results in slightly decreased estimated ERs for measurements at or below the detection limit. Specifically, a sensitivity analysis of CH4 emissions revealed that the average relative difference for facilities emitting less than 0.1 gCH4 s−1 was around 40% (50% POD greater than 25% POD), and the effect quickly dropped off with increasing emissions, with facilities emitting less than 10 gCH4 s−1 exhibiting a relative difference of 10% and those emitting more than 10 gCH4 s−1 exhibiting a 7% difference. Although the overall results of this study were not significantly different using a 50% POD, our data are better represented using a 25% POD as it yields ER estimations equal to or less than the detection limit (that is, when the exponential distribution is selected as the likelihood function).

We assumed no knowledge of emissions before sampling and, as a result, took the initial prior PDF to be uniform. After the first transect, the posterior PDF, \(p(Q|{\underline{C}},{\underline{m}}^{\prime} )\), from the previous transect was used as the prior in what is referred to as the updated prior method49:

where:

The final posterior PDF was then used to calculate the ER and uncertainty for that sampling period. Following Moore et al.8, we incorporated uncertainty related to (1) the choice of dispersion model, (2) atmospheric variability and (3) model assumptions into our analysis via the noise power, σe (supplementary information section 5 in ref. 8). Where the average location of plume centres on left- and right-bound transects (relative to the source, looking downwind) were greater than 10 m difference downwind of the source, σe was calculated individually for ‘near’ and ‘far’ transects. Individual transects could exhibit high uncertainty, but with more data (that is, transects) used to inform the results, uncertainty was minimized. Thus, a target of ten transects was used as it was found, through a combination of measurements and large eddy simulations, to be optimal in maximizing the efficiency of the approach while minimizing uncertainty47.

Measurable emissions (that is, greater than the detection limit) of at least one species were detected from 82% of successfully sampled WRRFs (79 out of 96). Specifically, 31 WRRFs emitted only detectable CH4, 38 had measurable emissions of both CH4 and N2O, 2 had measurable emissions of CH4 and NH3, and 8 had measurable emissions of all 3 gases. In addition, the median duration of all observational periods was 38 min, including time spent measuring wind. The mean (standard deviation) duration was 46 (29) min, with a maximum duration of 251 min.

Facility-level data acquisition

Publicly available data for influent flows and organic/nitrogen loading for individual facilities are limited. These data are critical to accurately report EFs and further contextualize measured emissions. Therefore, we took a tiered approach to quantify facility flow rates and nutrient loading specific to the sampling date, through which we obtained the relevant data sequentially through discharge monitoring reports, open records requests and surveys, facility websites, state databases and the US EPA CWNS. Similarly, even basic information on the treatment processes used by WRRFs is seldom available to the public. Thus, a similar tiered approach was used to categorize the secondary wastewater treatment and solids treatment for each sampled WRRF. These two approaches are described in detail in Supplementary Information, section 2.

Facility-level to national-level scaling

We used a novel probabilistic technique to scale the emissions of each gas from the more than 3,000 individual transects to the entire US domestic wastewater treatment sector, treating each sampled facility with equal weight. Note that this does not include the effects of diurnal or seasonal variability (Supplementary Information, section 8); however, as presented in Supplementary Information, section 9, accounting for these effects introduced greater uncertainty and altered our results by 1% and 6% for CH4 and N2O, respectively. Figure 2a–c shows the probability distributions of sector-wide emissions of CH4, N2O and NH3 in the USA. For reference, in this figure, the CH4 and N2O emissions for 2022 from the US EPA inventory10 are presented as black dashed lines with the 95% CIs indicated by grey shading. These are compared with the mean scaled value for each gas along with the 95% CI from bootstrapping, presented as orange solid lines and orange shaded regions, respectively. These distributions are positively skewed, which is unsurprising given the similar distributions of both the size of US WRRFs and their respective EFs.

We scaled the measured ERs from individual observational periods to a national-scale sector-wide emissions estimate as follows:

-

1.

Beginning with the ER posterior PDFs resulting from the mobile measurement method discussed above and in ref. 8 to quantify individual facility emissions for any given observational period, we produced EF PDFs for each observational period by using Monte Carlo sampling. The probability distributions for flow rates and influent nutrient (BOD5 and TN) concentrations were assumed to be of the Gaussian form with mean and standard deviation, as specified in Supplementary Information, section 2. For each observational period, we took 10,000 random samples, with replacement, from these three PDFs to develop a PDF of EFs for each observational period. Negative emissions were not considered, so all sampled values below zero were removed.

-

2.

We then developed facility EF PDFs by taking the average of all PDFs for each facility, weighting each observational period equally.

-

3.

Each facility was then categorized as small (<1 MGD), medium (1–10 MGD) or large (>10 MGD), as specified by the US EPA, and 10,000 random samples from the facility EF PDFs, with equal weighting, were taken to produce a PDF representative of that size category.

-

4.

These size category EF PDFs were then multiplied by the amount of wastewater treated by that category, according to the US EPA. Specifically, small, medium and large facilities treat 11%, 27% and 62% of the centralized domestic wastewater in the USA, respectively. By applying this binning approach, we are, in essence, weighting observed EFs by facility size to limit the influence of high EF variability for smaller facilities given the outsized contribution of large facilities to the total waste treated. Furthermore, while Song et al.9 applied a similar scaling approach, binning by treatment process and using Monte Carlo sampling, insufficient data on sampled facility treatment processes and the nature of facility-integrated emissions prevented the use of that method. These percentages were multiplied by the total organics (10,216 ktBOD5 yr−1) and nitrogen (2,560 ktTN yr−1) treated by centralized domestic WRRFs (84%). These values of BOD5 and TN were calculated from the data in tables 7–12 and equations 7–35 of ref. 10. The assumption of 84% of domestic wastewater treated centrally also comes from chapter 7 of the same source. The resulting PDFs were taken to be the total annual emissions for each size category.

-

5.

Finally, these PDFs were summed to a PDF of total, sector-wide emissions for each respective gas, as shown in Fig. 2.

The sector-wide emissions reported in the main text were calculated as the mean of the total annual emissions calculated above. Finally, the 95% CIs reported in the main text were calculated using a bootstrapping technique, recreating the sampling above, with replacement, and determining the spread of the computed means across 200 iterations and reporting the 2.5 to 97.5 percentiles. Table 2 summarizes the fraction of US facilities and total wastewater flow by size category, as well as their relative contribution to the sector-wide emissions of CH4, N2O and NH3.

Statistics

The two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test was used throughout this study to test for a significant difference between central tendencies of two distributions of independent samples. We used this test as it is non-parametric and is meant to handle non-normal (for example, heavily skewed), although similar distributions that exist throughout the data. We used the scipy.stats mannwhitneyu function and reported the resulting p values wherever noted in the manuscript.

Data availability

Raw mobile measurements are not provided to maintain the anonymity of individual sampled facilities. For each observational period, discrete probabilities across a range of emission rates, from which measured emissions and uncertainties were inferred, are anonymized and available at https://doi.org/10.34770/xjeq-c385. The average measured meteorological conditions and ERA5 reanalysis data necessary for the determination of atmospheric stability class and Gaussian plume dispersion modelling are available at https://doi.org/10.34770/xjeq-c385. Facility discharge monitoring reports are available at https://echo.epa.gov/, ERA5 data are available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47, US EPA Clean Water Needs Survey data are available at https://www.epa.gov/cwns, projected global GHG emissions are available at https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/ and projected global wastewater treatment data are available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118921. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All software used for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Forster, P. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) Ch. 7 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Prather, M. J., Holmes, C. D. & Hsu, J. Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 6–10 (2012).

Prather, M. J. et al. Measuring and modeling the lifetime of nitrous oxide including its variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 5693–5705 (2015).

Samuelsson, J. et al. Optical technologies applied alongside on-site and remote approaches for climate gas emission quantification at a wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 131, 299–309 (2018).

Gu, B. et al. Abating ammonia Is more cost-effective than nitrogen oxides for mitigating PM2.5 air pollution. Science 374, 758–762 (2021).

Holtgrieve, G. W. et al. A coherent signature of anthropogenic nitrogen deposition to remote watersheds of the Northern Hemisphere. Science 334, 1545–1548 (2011).

Phoenix, G. K. et al. Impacts of atmospheric nitrogen deposition: responses of multiple plant and soil parameters across contrasting ecosystems in long-term field experiments. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 1197–1215 (2012).

Moore, D. P. et al. Underestimation of sector-wide methane emissions from United States wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 4082–4090 (2023).

Song, C. et al. Methane emissions from municipal wastewater collection and treatment systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 2248–2261 (2023).

US EPA. Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 1990–2022 (2024).

Hwang, K. L., Bang, C. H. & Zoh, K. D. Characteristics of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from the wastewater treatment plant. Bioresour. Technol. 214, 881–884 (2016).

El-Fadel, M. & Massoud, M. Methane emissions from wastewater management. Environ. Pollut. 114, 177–185 (2001).

Foley, J., de Haas, D., Yuan, Z. & Lant, P. Nitrous oxide generation in full-scale biological nutrient removal wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 44, 831–844 (2010).

Masuda, S., Sano, I., Hojo, T., Li, Y. Y. & Nishimura, O. The comparison of greenhouse gas emissions in sewage treatment plants with different treatment processes. Chemosphere 193, 581–590 (2018).

Czepiel, P., Crill, P. & Harriss, R. Nitrous oxide emissions from municipal wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29, 2352–2356 (1995).

Czepiel, P. M., Crill, P. M. & Harriss, R. C. Methane emissions from municipal wastewater treatment processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 2472–2477 (1993).

Ahn, J. H. et al. N2O emissions from activated sludge processes, 2008–2009: results of a national monitoring survey in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 4505–4511 (2010).

Daelman, M. R. J., van Voorthuizen, E. M., van Dongen, U. G. J. M., Volcke, E. I. P. & van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. Methane emission during municipal wastewater treatment. Water Res. 46, 3657–3670 (2012).

Daelman, M. R. J., van Voorthuizen, E. M., van Dongen, U. G. J. M., Volcke, E. I. P. & van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. Seasonal and diurnal variability of N2O emissions from a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 536, 1–11 (2015).

Yver Kwok, C. E. et al. Methane emission estimates using chamber and tracer release experiments for a municipal waste water treatment plant. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 2853–2867 (2015).

Gålfalk, M., Påledal, S. N., Sehlén, R. & Bastviken, D. Ground-based remote sensing of CH4 and N2O fluxes from a wastewater treatment plant and nearby biogas production with discoveries of unexpected sources. Environ. Res. 204, 111978 (2021).

Delre, A., Mønster, J., Samuelsson, J., Fredenslund, A. M. & Scheutz, C. Emission quantification using the tracer gas dispersion method: the influence of instrument, tracer gas species and source simulation. Sci. Total Environ. 634, 59–66 (2018).

Vasilaki, V., Massara, T. M., Stanchev, P., Fatone, F. & Katsou, E. A decade of nitrous oxide (N2O) monitoring in full-scale wastewater treatment processes: a critical review. Water Res. 161, 392–412 (2019).

US EPA. Sources and Solutions: Wastewater; https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/sources-and-solutions-wastewater (accessed 12 November 2023).

Daelman, M. R. J., De Baets, B., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Volcke, E. I. P. Influence of sampling strategies on the estimated nitrous oxide emission from wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 47, 3120–3130 (2013).

Song, C. et al. Oversimplification and misestimation of nitrous oxide emissions from wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1348–1358 (2024).

Doorn, M. et al. 2019 refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Chapter 6 Wastewater Treatment and Discharge. Wastewater Treatment and Discharge 5, 7–65 (2019).

Valach, A. C., Häni, C., Bühler, M., Mohn, J. & Schrade, S. Ammonia emissions from a dairy housing and a wastewater treatment plant 1 quantified with an inverse dispersion method accounting for deposition loss ammonia emissions; inverse dispersion method. J. Air Waste Manage. 73, 930–950 (2023).

Yoshida, H., Mønster, J. & Scheutz, C. Plant-integrated measurement of greenhouse gas emissions from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 61, 108–118 (2014).

Delre, A., Mønster, J. & Scheutz, C. Greenhouse gas emission quantification from wastewater treatment plants, using a tracer gas dispersion method. Sci. Total Environ. 605–606, 258–268 (2017).

Tauber, J., Parravicini, V., Svardal, K. & Krampe, J. Quantifying methane emissions from anaerobic digesters. Water Sci. Technol. 80, 1654–1661 (2019).

Parravicini, V., Nielsen, P. H., Thornberg, D. & Pistocchi, A. Evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions from the European urban wastewater sector, and options for their reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156322 (2022).

US EPA. 2020 National Emissions Inventory; https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-inventories/2020-national-emissions-inventory-nei-data (accessed 21 August 2021).

Zavala-Araiza, D. et al. Super-emitters in natural gas infrastructure are caused by abnormal process conditions. Nat. Commun. 8, 14012 (2017).

Alvarez, R. A. et al. Assessment of methane emissions from the US oil and gas supply chain. Science 361, 186–188 (2018).

Law, Y., Ye, L., Pan, Y. & Yuan, Z. Nitrous oxide emissions from wastewater treatment processes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 1265–1277 (2012).

Jones, E. R., Van Vliet, M. T. H., Qadir, M. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Country-level and gridded estimates of wastewater production, collection, treatment and reuse. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 237–254 (2021).

Höglund-Isaksson, L., Gómez-Sanabria, A., Klimont, Z., Rafaj, P. & Schöpp, W. Technical potentials and costs for reducing global anthropogenic methane emissions in the 2050 timeframe—results from the gains model. Environ. Res. Commun. 2, 025004 (2020).

de Foy, B., Schauer, J. J., Lorente, A. & Borsdorff, T. Investigating high methane emissions from urban areas detected by TROPOMI and their association with untreated wastewater. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 044004 (2023).

US EPA. Biden-Harris administration announces availability of $350 million in grants to states to cut methane emissions from oil and gas sector; https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-announces-availability-350-million-grants-states-cut (30 August 2023).

McDermitt, D. et al. A new low-power, open-path instrument for measuring methane flux by eddy covariance. Appl. Phys. B 102, 391–405 (2011).

Tao, L., Sun, K., Miller, D. J., Khan, M. A. & Zondlo, M. A. Current and frequency modulation characteristics for continuous-wave quantum cascade lasers at 906 μm. Opt. Lett. 37, 1358 (2012).

Miller, D. J., Sun, K., Tao, L., Khan, M. A. & Zondlo, M. A. Open-path, quantum cascade-laser-based sensor for high-resolution atmospheric ammonia measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 81–93 (2014).

Pan, D. et al. A new open-path eddy covariance method for nitrous oxide and other trace gases that minimizes temperature corrections. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1446–1457 (2022).

Burba, G., Anderson, T. & Komissarov, A. Accounting for spectroscopic effects in laser-based open-path eddy covariance flux measurements. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2189–2202 (2019).

Caulton, D. R. et al. Importance of superemitter natural gas well pads in the Marcellus shale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4747–4754 (2019).

Caulton, D. R. et al. Quantifying uncertainties from mobile-laboratory-derived emissions of well pads using inverse Gaussian methods. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 15145–15168 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Estimation of methane emissions from the US ammonia fertilizer industry using a mobile sensing approach. Elementa 7, 19 (2019).

Albertson, J. D. et al. A mobile sensing approach for regional surveillance of fugitive methane emissions in oil and gas production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2487–2497 (2016).

Roe, S. M. et al. Estimating Ammonia Emissions from Anthropogenic Nonagricultural Sources (Emission Inventory Improvement Program, 2004).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation’s Energy and Environment programme (G-2020-12453, to M.A.Z., Z.J.R. and F.M.H.) and NASA’s Future Investigators in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology (FINESST) programme (80NSSC21K1632, to D.P.M. and M.A.Z.). We thank C. Beale, R. Wang and X. Guo for their helpful discussions and assistance with field logistics and data acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P.M. led sampling strategy development, data acquisition, data analysis and the writing of the manuscript. N.P.L. contributed equally to data acquisition and led sensor maintenance, assisted in data analysis and overall guidance. C.S. and J.-J.Z. provided domain guidance. H.Y. and L.T. led sensor development. J.M., V.I.S. and L.P.W. assisted in data acquisition. N.E.R.-R. and F.M.H. provided guidance on data acquisition and project development. Z.J.R. provided project and domain guidance. M.A.Z. guided the overall project scientifically and logistically, including contributions in writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks Yiwen Liu, Hong-Cheng Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Figs. 1–20 and Tables 1–11.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Average WRRF emission rates and nutrient load, including WRRF treatment information and throughput.

Source Data Fig. 2

Probability distributions of US estimated emission inventory from WRRFs.

Source Data Fig. 3

Average emission factors for each sampled WRRF, cumulative distribution of GWP across all facilities.

Source Data Fig. 4

Projected emissions and contributions of WRRFs to overall future global emissions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, D.P., Li, N.P., Song, C. et al. Comprehensive assessment of the contribution of wastewater treatment to urban greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions. Nat Water 3, 1114–1124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00490-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00490-z