Abstract

Agricultural irrigation has experienced rapid expansion, and its growing freshwater consumption is potentially exacerbating water scarcity issues. Previous studies predominantly relied on observations or land-only simulations, often neglecting land–atmosphere interactions or failing to capture long-term evolution. We therefore analyse the effects of historical irrigation expansion on water fluxes and resources using seven Earth system models. Here we show that irrigation expansion in many regions substantially decreases the net water influx from the atmosphere to land, further aggravating the existing drying trends caused by climate change. For example, irrigation expansion changed the trend of this net influx from −0.664 ( ± 0.283) to −1.461 ( ± 0.261) mm yr−2 in South Asia after 1960. Consequently, the local terrestrial water storage depletion rate is substantially enlarged by irrigation expansion (for example, from −2.559 ( ± 0.094) to −16.008 ( ± 0.557) mm yr−1). Our results attribute the land water loss to irrigation expansion and climate change, calling for immediate solutions to tackle the negative trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Irrigation considerably enhances crop yields and plays a crucial role in ensuring food security, supporting ~40% of global food and fibre production on ~17% of the world’s cropland1. Driven by population growth and rising living standards, the area equipped for irrigation has expanded rapidly2. In the early 1900s, this expansion mainly occurred in North America, particularly in the western USA, where federal funding under the ‘Reclamation Act of 1902‘ supported efforts to convert desert and semi-arid lands into irrigated farmland3. During the second half of the twentieth century, several national and regional initiatives contributed to further growth, such as the ‘Green Revolution’ of India4 and Saudi Arabia’s agricultural support policy5. These efforts help explain the accelerating rate of expansion in global irrigated area after the 1950s2.

Irrigation has long been the largest contributor to freshwater withdrawal and consumption, accounting for over 70% of global freshwater withdrawals and ~90% of total consumption6,7. Consequently, the rapid expansion of irrigated cropland has driven a continuous rise in both global and regional irrigation water withdrawal (IWW)8,9. This growing demand for freshwater can substantially affect local water availability, and many studies have linked irrigation expansion to streamflow reductions or lake shrinkage in recent decades10,11,12. In response, concerns over the sustainability of irrigation water use have arisen, leading to the emergence of ‘sustainable irrigation’—a practice aimed at ensuring crop yields while avoiding freshwater resources depletion and aquatic ecosystems degradation. This concept has been widely studied and assessed13,14,15. For example, based on a previous study, half of the irrigation expansion in the twenty-first century has been deemed unsustainable16.

Due to limited surface water availability, groundwater has become a vital source of irrigation, particularly in intensively irrigated regions with arid and semi-arid climates. A global inventory based on national and sub-national data shows that groundwater irrigation supports 38% of global area equipped for irrigation and accounts for 43% of freshwater used for irrigation17. However, as groundwater-fed irrigation expands, recharge rates have failed to offset withdrawals, resulting in widespread declines in groundwater levels. For instance, in the US High Plains, groundwater levels are estimated to have dropped by an average of 4 metres between the 1950s and 200718. In the North China Plain, most villages experienced a decline in groundwater depth from 1995 to 2014, with many reporting total decreases of ≥ 1.5 m (ref. 19). Similarly, satellite-based data indicate that groundwater levels in North India declined at a rate of ~4.0 cm yr−1 during the early 2000s20.

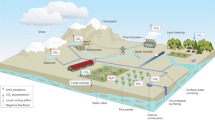

With its considerable amount of water consumption, irrigation has become an increasingly substantial forcing in the Earth system, substantially altering the land energy balance and water cycle8,21,22. One major impact of irrigation is the enhancement of land evapotranspiration, which intensifies with the expansion of irrigated areas. For example, a multi-model study found that irrigation expansion shifted the evapotranspiration trend over densely irrigated pixels from near neutral to approximately 40.42 mm yr−2 (equivalent to 3.14 W m−2 yr−1 for the latent heat flux) between 1960 and 201421. These changes in energy and water fluxes can, in turn, influence large-scale climate dynamics, potentially altering precipitation patterns23,24,25. Long-term simulations show that irrigation expansion between 1960 and 2014 led to an ~21.90 mm yr−1 increase in precipitation over the most densely irrigated pixels21. However, the precipitation response to irrigation varies across regions, for example, irrigation increases rainfall over the North China Plain and Saudi Arabia25,26 but decreases the precipitation in India and the mid-western United States24,27. This suggests that changes in precipitation may offset or aggravate irrigation-induced water depletion. Therefore, accounting for land–atmosphere interactions is essential when assessing the impacts of irrigation expansion on water availability.

Constrained by long-term data availability, most observation-based studies cover only a small region or a short period18,20, so global land system models have been widely used to detect irrigation-induced impacts on water resources at large scales in previous studies28,29. However, these models have external climate datasets as input and thus ignore the land–atmosphere interactions, which may induce uncertainties, as previously discussed. Additionally, most of these studies used static irrigation maps, preventing them from capturing the evolving impacts of irrigation associated with its spatial and temporal changes. To address these issues, we analyse outputs from the IRRigation Model Intercomparison Project (IRRMIP)9, in which seven Earth System Models (ESMs) performed land–atmosphere coupled simulations for the period 1901–2014 with transient land use and management. We first quantify the historical irrigation expansion and consequent increase in irrigation water use. Then, we separate the effects of irrigation expansion from other forcings by comparing outputs from two experiments, with irrigation expansion (tranirr) and without irrigation expansion (1901irr). Finally, the spatial and temporal patterns of changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration, runoff and terrestrial water storage are analysed to reveal the evolution of land water availability during the study period.

Rapid irrigation expansion and increase in irrigation water withdrawal

In IRRMIP, areas equipped for irrigation (hereafter irrigation area) are obtained from the Land-Use Harmonization 2 (LUH2) dataset based on multiple sources30. Many grid cells in South Asia and East Asia, and some in Central North America, have experienced strong irrigation expansion since 1901 (Fig. 1a), with increases in the irrigated fraction of over 40% by 2014 (Fig. 1b,c). Globally aggregated results show that irrigation area increased rapidly from ~0.5 million km2 in 1901 to ~2.7 million km2 in 2014, representing a 5.4-fold increase over 114 years9. Increased irrigation area directly drives an increase in IWW (Fig. 1e,f). Globally aggregated values range from ~200–500 km3 yr−1 in 1901 to ~900–4,000 km3 yr−1 in 2014 (simulated by seven models: CESM2, CESM2_gw, NorESM2, E3SMv2, MIROC-INTEG-ES, IPSL-CM6 and CNRM-CM6-1)9.

a–c, Irrigated grid cell fraction in the year 1901 (a) and 2014 (b) and their difference (c). d, Temporal trend of the terrestrial water storage (TWS) from April 2002 to February 2024. The trend is calculated via linear regression, and only values with a p value ≤ 0.1 are shown. e,f, Multi-model mean simulated annual irrigation water withdrawal of the simulations with irrigation expansion in the first (e) and the last (f) 30 years. Green and red boxes indicate the boundaries of the four climate reference regions. TWS data are taken from ref. 62 at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° and monthly interval. Region boundaries in a–f indicate the spatial coverage of four climate reference regions, which are adapted from ref. 31 under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.

Four climate reference regions are selected for the following analysis: South Asia, Mediterranean, Central North America and West Central Asia31 (Fig. 1a), as many grid cells experience irrigation expansion, and simulations from seven ESMs show a high level of agreement over these regions. In South Asia, irrigated cropland expanded gradually from ~0.13 million km2 in 1901 to ~0.25 million km2 by 1960, then grew rapidly to over 0.7 million km2 by 2014 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). This acceleration was probably driven by government efforts and subsidies—supported by international donors such as the World Bank—to promote the development of private pumping wells4. As a key policy during the ‘Green Revolution’ period, this initiative not only substantially increased the area equipped for irrigation but also deepened the region’s reliance on groundwater. Similarly, in the Mediterranean, irrigated farmland increased from less than 0.05 million km2 to ~0.11 million km2 by the 1960s, then surged to over 0.20 million km2 in the early 2000s (Extended Data Fig. 1b). This shift in the rate of expansion can be attributed to several post-war development projects32. In Central North America, irrigated area began at nearly zero in 1901 and increased steadily—with varying rates—to ~0.13 million km2 by the 1990s. It then declined slightly to around 0.12 million km2 by 2000 and has remained nearly constant since (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The expansion in the early twentieth century may be linked to the introduction of the ‘Reclamation Act of 1902’3. In West Central Asia, the area equipped for irrigation increased steadily from ~0.06 million km2 in 1901 to ~0.33 million km2, with the most rapid expansion occurring between 1970 and 1990 (Extended Data Fig. 1d). This growth may be attributed to the construction of dams and reservoirs as part of several national initiatives, such as the ‘Southeastern Anatolia Project’ in Turkey33 and Iran’s National Water Resources Development Plan34. Despite the wide range, seven models agree that IWW increases steadily over all four regions, with mean values approaching ~80, 18, 18 and 40 mm yr−1 in the year 2014, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1e–h).

Changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration and runoff

Here we calculate the impacts of all historical climate forcings (for example, greenhouse gas emissions, aerosol concentrations, land-use change, irrigation expansion) on precipitation, evapotranspiration and runoff (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c) (Methods). Comparing the last 30 years (1985–2014) to the first 30 years (1901–1930), substantial changes (≥ 50 mm yr−1) occur only in low- and mid-latitude regions, with a decrease in most regions except South Asia and the eastern part of Central Africa, and oppositely, in high-latitude regions there are smaller increases in precipitation, consistent with patterns observed in long-term reanalyses35 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Those modifications in precipitation patterns then drive the changes in evapotranspiration (Extended Data Fig. 2b) and runoff (Extended Data Fig. 2c). After separating the impacts of irrigation expansion from other forcings (Methods), we find that irrigation expansion generally has much less pronounced impacts than other forcings on water fluxes, especially on precipitation and runoff (Extended Data Fig. 2d–i). The only exception is that in some regions (for example, South Asia, Central North America and West Central Asia), evapotranspiration is substantially enhanced (≥ 50 mm yr−1) (Extended Data Fig. 2h).

To explore how water fluxes and impacts of different forcings evolve with time, we separate the study period into six 19-year periods and calculate the mean annual precipitation, evapotranspiration and runoff over four climate reference regions (Fig. 2). Models agree that irrigation expansion can increase evapotranspiration, and this increase is relatively substantial in drier regions such as West Central Asia (Fig. 2b,e,h,k). In the last 19-year period (1996–2014), the difference in multi-model mean evapotranspiration between tranirr and 1901irr reaches 58.2 (South Asia, with the 25th to the 75th percentile value range of 32.9 to 76.1), 17.0 (Mediterranean, 6.2 to 25.8), 14.9 (Central North America, −1.4 to 33.6) and 36.9 (West Central Asia, 17.9 to 44.4) mm yr−1 over four regions, respectively (Fig. 2b,e,h,k). Changes in precipitation are less pronounced and diverging among regions and models, for example, in the last 19-year period (1996–2014), multi-model mean precipitation is reduced by ≥ 7.7 (−68.2 to 45.5) mm yr−1 in South Asia (Fig. 2a), increased by ≥ 18.6 (−11.6 to 47.0) and 21.2 (−4.6 to 40.3) mm yr−1 in Central North America and West Central Asia but not affected in the Mediterranean (mean value −0.1, and the range −9.8 to 5.7 mm yr−1) (Fig. 2d,g,j). Regarding the runoff, multi-model mean results show a positive change caused by irrigation expansion, as irrigation activities relocate water from various sources to the crop field, re-generating runoff (Fig. 2c,f,i,l). However, simulations with irrigation expansion have larger ranges than those without irrigation expansion, which can be explained by different implementations among models (Table 1). For example, in CESM2 and NorESM, the irrigation water is directly withdrawn from local runoff, leading to a decrease in runoff.

a–l, Multi-year mean simulated multi-model mean (bars), 25th and 75th percentile values (error bars) of precipitation (P; a,d,g,j), evapotranspiration (ET; b,e,h,k) and runoff (R; c,f,i,l), with and without irrigation expansion during six 19-year periods (I: 1901–1919, II: 1920–1938, III: 1939–1957, IV: 1958–1976, V: 1977–1995, VI: 1996–2014) over South Asia (a–c), Mediterranean (d–f), Central North America (g–i) and West Central Asia (j–l). The 25th and 75th percentile values shown here are the mean value of the annual 25th and 75th percentile values calculated in each year of seven models during the period. Black dots indicate the 19-year-mean values of each model.

Extra evapotranspiration is not offset by enhanced precipitation

To quantify the changes in regional terrestrial water, we use precipitation minus evapotranspiration (P − ET), which indicates the net input of water from the atmosphere to land. An increase in P − ET contributes to local water storage and outflow to neighbouring regions, whereas a decrease may reduce the water outflow or even deplete local water resources. In our simulations, all forcings combined (Table 2) cause a reduction of P − ET across vast parts of the global land in low- and mid-latitude regions, including North America, the northern part of South America, the Mediterranean, western parts of Central and South Africa, West Central Asia and South China (Fig. 3a). Among them, the decrease in Central North America, the Mediterranean, West Central Asia and the northern part of South Asia, is triggered by irrigation expansion (Fig. 3e). Changes in climate explain the decrease in other regions and also the increase in a few regions, such as the eastern parts of Central Africa, Japan, Northeast Russia and a small part of South India (Fig. 3c).

a–f, Impacts of all forcings (a,b), other forcings (c,d) and irrigation expansion (e,f) on P − ET (a,c,e) and TWS (b,d,f). The impacts are computed through a comparison of multi-year mean values over different periods or different experiments (Table 2). Results of P − ET shown are the multi-model mean value across seven models, and hatches indicate that ≥ six out of seven models show consistency in the sign of change (≤ −20 or ≥ 20 mm yr−1). Results of TWS shown are the multi-model mean value across five models with groundwater withdrawal implementation (CESM2_gw, CNRM-CM6-1, MIROC-INTEG-ES, E3SMv2 and IPSL-CM6) and hatches indicate that ≥ three out of five models show consistency in the sign of change (≤ −50 or ≥ 50 mm). Region boundaries in a–f adapted from ref. 31 under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.

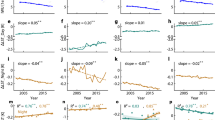

P − ET is reduced by irrigation expansion in all four climate reference regions, with varying relative importance across the regions. In South Asia, irrigation expansion results in a decrease in P − ET, and this negative trend intensifies with time (−0.418 mm yr−2 before 1960 and −0.797 mm yr−2 after 1960). As a result, irrigation expansion slows the increasing trend before the year 1960 (+1.194 in 1901irr to +0.776 mm yr−2 in tranirr) and exacerbates the negative trend after 1960 in regional mean P − ET (−1.461 mm yr−2) (Fig. 4a,b). At the end of the study period, the reduction reaches ≥ 50 mm yr−1. A similar pattern is observed in the Mediterranean, where irrigation expansion decreases local P − ET by 0.078 and 0.338 mm yr−2 during pre- and post-1960 periods and therefore contributes to an overall decreasing trend of −0.425 mm yr−2 after the year 1960 (Fig. 4c,d). In Central North America, irrigation expansion has a smaller impact on P − ET, but other forcings lead to a reduced P − ET (−0.209 mm yr−2), and irrigation expansion aggravates this decreasing trend (to −0.299 mm yr−2) (Fig. 4e,f). In West Central Asia, other forcings lead to a slightly rising trend (+0.023 mm yr−2), but irrigation expansion has a pronounced decreasing impact (−0.140 mm yr−2), reversing the trend to −0.116 mm yr−2.

a–h, Regionally average annual land P − ET anomaly from both simulations with (tranirr) and without irrigation expansion (1901irr) and the difference between them (tranirr − 1901irr) over South Asia (a,b), the Mediterranean (c,d), Central North America (e,f) and West Central Asia (g,h). All values shown are the relative values to the mean value during the first 19 years (1901–1919) in the simulation without irrigation expansion (1901irr). Solid lines indicate the multi-model (seven models) mean values and ranges indicate the 25th and the 75th percentile values. Curves were smoothed using Savitzky–Golay filtering (order = 2, window = 19)73. * after the numbers indicates the significance of linear regression analysis, among which ** indicates that p value is less than 0.05 and *** indicates that p value is less than 0.01. All p values are calculated under the null hypothesis that the true coefficient between the time and land P − ET is zero. These statistics are two-sided and follow a t distribution with N − 2 degrees of freedom (N indicates the number of years in the study period, for example, N equals 60 when the study period is 1901 to 1960). The numbers in brackets indicate the interval at 0.05 confidence level.

Loss of terrestrial water resources is not compensated by inflow from upstream regions

Considering that the decrease in P − ET affects local water availability, we then assess whether the water loss is compensated by enhanced inflow from neighbouring regions. To this end, we analyse the simulated change in terrestrial water storage (TWS) anomaly, which is the sum of surface and subsurface water on land, including soil moisture, groundwater, snow and ice cover, water stored in vegetation, river and lake water. We first calculate the trend of monthly TWS during the period April 2002 to February 2024 from the satellite-based observations (Fig. 3d) and find a decreasing trend over many irrigation hot spots, including Southwest USA, the Mediterranean, West Central Asia, North India and North China Plain. A previous study based on the same dataset, but during the period from April 2002 to March 2016, has attributed the decrease over many regions mentioned above to groundwater depletion or the decline in lake levels36.

Examining TWS from IRRMIP, we now focus on five ESMs, CESM2_gw, MIROC-INTEG-ES, CNRM-CM6-1, IPSL-CM6 and E3SMv2, because CESM2 and NorESM2 do not account for groundwater withdrawal (Methods). Changes between the two periods (1901–1930 and 1985–2014) show large spatial heterogeneity, but the general pattern is similar to that of precipitation, except in very high-latitude regions, where TWS is greatly decreased, possibly due to glacier and ice melt (Fig. 3b). The impacts of irrigation expansion on TWS can be divided into two opposing effects: (1) water withdrawn from surface and subsurface sources directly decreases the water storage and (2) water applied into fields increases local soil moisture, and return flow may recharge local water resources. Mean values simulated by five models reveal that the first effect dominates in most intensely irrigated regions, which also plays a more important role than other forcings (Fig. 3d,f).

Considering the various groundwater implementations among models (Methods), we show the time series of TWS simulated by the two groups of models (Fig. 5). The first group (solid lines and ranges) consists of CESM2_gw, MIROC-INTEG-ES, E3SMv2, IPSL-CM6 and CNRM-CM6-1, in which groundwater withdrawal for irrigation is implemented; the second (dashed lines) consists of CESM2 and NorESM, in which groundwater is not used, and ocean water is withdrawn to close the water balance when needed. Results of the first group show that irrigation expansion substantially changed the evolution of TWS in all four regions (Fig. 5a,c,e,g). The decreasing rate is higher in the second part of the study period, for example, −3.655 mm yr−1 before 1960 and −13.449 mm yr−1 after 1960 in South Asia, −1.834 mm yr−1 before 1960 and −6.172 mm yr−1 after 1960 in West Central Asia (Fig. 5b,d,f,h). The models in group 2 do not produce a difference between the two simulations.

a–h, Regional average annual land TWS anomaly from both simulations with (tranirr) and without irrigation expansion (1901irr) and the difference between them (tranirr − 1901irr) over South Asia (a,b), the Mediterranean (c,d), Central North America (e,f) and West Central Asia (g,h). All values shown are the relative values to the mean value during the first year (1901) in the simulation without irrigation expansion (1901irr). Solid lines indicate the multi-model (five models with groundwater withdrawal implementation: CESM2_gw, CNRM-CM6-1 and MIROC-INTEG-ES, E3SMv2 and IPSL-CM6) mean values and ranges indicate the 25th and the 75th percentile values. Dashed lines indicate the mean values of two models without groundwater withdrawal implementation (CESM2 and NorESM2). Curves were smoothed using Savitzky–Golay filtering (order = 2, window = 19)73. * after the numbers indicates the significance of linear regression analysis, among which ** indicates that p value is less than 0.05 and *** indicates that p value is less than 0.01. All p values are calculated under the null hypothesis that the true coefficient between the time and land P − ET is zero. These statistics are two-sided and follow a t distribution with N − 2 degrees of freedom (N indicates the number of years in the study period, for example, N equals 60 when the study period is 1901 to 1960). The numbers in brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study, we use ESMs as the main research tool to quantify the impacts of irrigation expansion on water resources while considering land–atmosphere interactions. However, we acknowledge that ESMs are limited in many aspects of crop and irrigation representations, such as (1) globally uniform irrigation parameters, (2) the lack of crop rotations and multiple growing seasons and (3) limited irrigation techniques representation. Moreover, some models do not explicitly account for groundwater consumption, and other models do not set a limit on the water consumption for irrigation, resulting in an under- or overestimation of irrigation water withdrawal. Furthermore, human interventions in the local water cycle, including reservoir construction and management, water extractions for other sectors (for example, domestic and livestock use) are not accounted for or are inadequately represented in most ESMs used in this study. Efforts are being made to implement irrigation techniques37,38, dam management39 and various water-use sectors40 in ESMs, but their performance heavily depends on the availability of external datasets or parametrizations. Apart from the processes and parameters directly related to irrigation practices and water abstraction, other aspects of different ESMs also introduce uncertainties. For example, the ESMs used in this study show large discrepancies in simulated precipitation over different regions, based on a previous evaluation41, which can substantially affect irrigation water demand. Similarly, the differences in simulated evapotranspiration across models42 can also influence the soil moisture, which is the key variable determining irrigation frequency and amount in many ESMs, and influencing the models’ hydrologic response to irrigation through its impact on the present-day hydrological regime. Although the results of IRRMIP provide important insights, concerted efforts are required, including model development and observational data generation, to better understand the role of irrigation in the Earth system.

The impact of irrigation expansion on water fluxes strongly depends on the volume of irrigation water, but its relative importance is typically more pronounced in arid and semi-arid regions, such as West Central Asia and the Mediterranean (Figs. 2 and 4). These regions have a drier background climate, so the majority of precipitation is lost as evapotranspiration, and this loss is further enhanced by irrigation expansion (Fig. 2). However, precipitation does not show a similar increasing trend, and consequently, the net atmospheric water input to land (P − ET) in these regions continues to decrease over the twentieth century (Fig. 4c,d,g,h). Both simulated (Fig. 3b) and observed data (Fig. 3d) show that TWS decreases over a large part of these regions, confirming that local water resources are being depleted due to irrigation expansion. In South Asia, irrigation expansion has reduced P − ET at the highest rate (Fig. 4a,b), and together with the climate change after 1960, a sharp decreasing trend of 1.461 mm yr−2 is reached. Although its relative impacts are less pronounced due to its wet background climate (Fig. 2a,c), most models considering groundwater pumping simulate a declining TWS there. Considering the high irrigated fraction and dense population here, local water availability will be increasingly concerning. In Central North America, despite the impacts of irrigation expansion are relatively small, the decreasing trend in P − ET induced by other forcings also threatens local water supply (Fig. 4e,f). Apart from these four regions, other irrigation hotspot areas, such as East China, California, the Nile Basin and Southeast Australia, also face this issue (Fig. 3). Our results indicate that irrigation-induced water depletion has become a common issue shared by many irrigation hotspot areas, and climate change may aggravate the scarcity of water resources, especially over arid and semi-arid regions.

Consistent with our findings, previous studies based on simpler calculations already concluded that many existing and newly expanded irrigated croplands over South Asia, East Asia and Central North America are not sustainable15,16, with substantial agricultural blue water (freshwater found in rivers, lakes and aquifers) scarcity issues43. More localized studies also confirm the depletion impacts of irrigation on local water resources19,44,45,46. Results of this study, at a global scale, reveal again that most irrigation hotspot regions face risks in terms of water availability, particularly in drier regions. This water depletion is not only caused by irrigation expansion but also driven by climate change. Interestingly, this work highlights the urgent situation over the Mediterranean and West Central Asia, despite the fact that these are not the most intensely irrigated regions. A previous study has already found that many countries in these regions do not have enough water resources to close the yield gap47, and therefore some prompt solutions are needed before local terrestrial water resources dry out, such as the adoption of sub-optimal irrigation (sacrificing part of crop yield) and water-saving irrigation techniques, for example, drip and sprinkler irrigation. Unfortunately, they are currently not yet widely used in many intensely irrigated countries such as India, China and many African nations48. Numerous studies have demonstrated that these techniques can reduce water consumption without compromising crop yields at the regional scale49,50. Considering that higher efficiency often encourages farmers to expand irrigated area, strong policies are then also required to avoid this paradox51.

Considering global population growth, irrigated cropland is expected to expand to ensure future food security52, whereas the global water gap is projected to widen under a warming climate53. Therefore, selecting suitable areas for irrigation expansion is becoming increasingly important. Although several efforts have been made to explore the potential for sustainable irrigation expansion under future climate scenarios54, many have not been implemented due to the substantial economic investment required55 and limited socio-economic capacities—particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia43. To address these challenges, intercontinental collaboration is essential to provide financial support and promote equitable development in these regions. However, in many other regions, even with the regulating function of dams and reservoirs, local water availability is projected to be unable to meet irrigation water requirements56, indicating that more solutions are needed to decrease irrigation water demand.

Global food trade can reduce the amount of water used for irrigation, if water-intensive crops are produced in regions with rich water resources and exported to water-scarce regions. On the basis of previous studies, virtual water trade helped save 119 × 109 m3 blue water (freshwater found in rivers, lakes and aquifers) and 105 × 109 m3 green water (water stored in the soil and used by plants) in 2008 and shows a positive trend over time57. However, currently, unsustainable irrigation water use still plays an important role in global virtual water trade58, indicating that there is room for optimization of the global crop trade network. Dietary changes have also been increasingly highlighted in recent studies, both for individual health and environmental protection59,60. Different amounts of water are needed to produce the same quantity of food or calories from different crops, referred to as the water footprint, which also differs across regions and periods61. Thus, transitioning to less water-intensive crops can offer another approach to mitigate water scarcity.

Methods

IRRMIP, ESMs and GRACE dataset

To analyse the impacts of historical irrigation expansion (1901–2014), the IRRigation Model Intercomparison Project (IRRMIP) was launched, with seven Earth System Models (ESMs) performing two land–atmosphere coupled experiments, with and without irrigation expansion. In the simulations with irrigation expansion (tranirr), transient irrigation extent from the Land-Use Harmonisation Project phase 2 (LUH2)30 is used, whereas in those without irrigation expansion (1901irr), the magnitude and pattern of irrigated cropland are fixed at the level in the year 1901. Other forcings, such as land-use changes and greenhouse gas emissions, are kept transient in both experiments. A more detailed simulation protocol can be found in the first paper of IRRMIP9. One exception is that in 1901irr of the IPSL-CM6, irrigation is entirely switched off.

In the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2)62 and the Norwegian Earth System Model version 2 (NorESM2), water is withdrawn from the main river channel next to the grid cell in the routing model, which exchanges information with the land model (the Community Land Model version 5: CLM5) every time water is abstracted. When the amount in the main channel cannot satisfy the water demand, water from the ocean will be abstracted to close the water balance. In addition, to represent the impacts of irrigation on local water resources, the amount of irrigation water withdrawal is subtracted from local runoff outputs. In CESM2_gw, water demand for irrigation is directly withdrawn from the main river channel next to the grid cell in the routing model. If it cannot meet the demand (only 90% of the runoff can be used for ecological reasons), groundwater will be abstracted to cover the rest of the demand. There is only unconfined groundwater in the model (groundwater in saturated soil) and the change in groundwater table affects inter-grid cell baseflow63,64. In the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SMv2), water demand for irrigation is pre-separated into surface water and groundwater demands based on a dataset of areas equipped for irrigation with surface and groundwater17. Surface water demand is conveyed to the routing model, and the routing model gives feedback to the land model on whether the surface water demand is satisfied based on local runoff, local streamflow and upstream reservoirs. As for the Centre National de Recherches Météorologiques Climate Model version 6 (CNRM-CM6-1), the irrigation water flux is imposed from an external dataset based on global hydrological model simulations65. The demand is pre-separated into surface water and groundwater demands, the same as in E3SMv2, and surface water is withdrawn from conceptualized small reservoirs, which can be recharged by rivers66. A capacity is assigned for each reservoir, based on the same historical irrigation water withdrawal dataset65. MIROC-INTEG-ES also considers three types of water resource to meet the irrigation water demand: river discharge, reservoir storage and groundwater. The order of priority for water intake sources is set in this order; whereas the model uses river water as the primary water resource for irrigation, if the river cannot supply enough water and a reservoir exists in the grid cell, the water stored in the reservoir is used for irrigation, and if there is no water in the reservoir or there is no reservoir, the groundwater is used for irrigation67. In the Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace Climate Model version 6 (IPSL-CM6), three sources are used: streamflow, overland water and renewable groundwater, and the fraction of groundwater demand is calculated before water withdrawal, based on AQUASTAT census area equipped for groundwater irrigation68. A table summarizing the key features of irrigation water withdrawal for irrigation is given below (Table 1). A more detailed description of all models regarding other aspects of irrigation can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

In this study, the TWS data used for trend analysis is from the twin Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, which measure the gravity field once per month since the year 2002 at ~400-km spatial resolution69. The high-degree coefficient estimations generally have larger errors, due to modelling and instrument errors and the weaker observability in the east–west direction70. To address this issue, mass concentration blocks are commonly used, and we choose the version RL0602 product during the period 2002–2024, with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° (ref. 71). Temporal trends are deduced from a linear regression between TWS data and time over each grid cell, and we only keep the linear TWS trends with R2 ≥ 0.6 and p value < 0.1.

Separation of irrigation expansion-induced impacts

The simulations were performed with varying spatial resolution (CESM2, CESM2_gw and NorESM2: 0.9° × 1.25°; MIROC-INTEG-ES: 1.4° × 1.4°; E3SMv2 and CNRM-CM6-1: 0.5° × 0.5°). We first regrid the outputs from E3SMv2, MIROC-INTEG-ES and CNRM-CM6-1 to 0.9° × 1.25° using second order conservative remapping. Then, to quantify the impacts of different forcings (irrigation expansion against greenhouse gas emissions, land-use change and so on), we separate both experiments (tranirr and 1901irr) into two periods (1901–1930 and 1985–2014) and calculate their average water fluxes (Table 2). Finally, we select four climate reference regions with intense irrigation and models’ agreement about changes in water variables (South Asia, Mediterranean, Central North America and West Central Asia)31 and calculate regional average water fluxes.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

GRACE Terrestrial Water Storage anomaly data are accessible via https://www2.csr.utexas.edu/grace/RL0602_mascons.html. The spatial range of climate reference regions can be obtained via Github at https://github.com/SantanderMetGroup/ATLAS (ref. 31). Data generated in this article are available via Figshare with the license CC BY 4.0 at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29664485.v1 (ref. 72).

Code availability

Codes used for calculation and plotting in this paper are provided via Github at https://github.com/YiYao1995/Yao_et_al_2025_Irrigation-induced_land_water_depletion_aggravated_by_climate_change.git.

References

Crops and Drops (FAO, 2002).

Siebert, S. et al. A global data set of the extent of irrigated land from 1900 to 2005. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 1521–1545 (2015).

Shubitz, S. Irrigating the West: Interest Group Lobbying and the Reclamation Act of 1902 (SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals, 2021).

Subramanian, K. Revisiting the Green Revolution: Irrigation and Food Production in Twentieth-Century India (King’s College London, 2015).

Al-Shayaa, M., Baig, M. & Straquadine, G. Agricultural extension in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: difficult present and demanding future. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 22, 239–246 (2012).

Döll, P., Fiedler, K. & Zhang, J. Global-scale analysis of river flow alterations due to water withdrawals and reservoirs. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 2413–2432 (2009).

Wada, Y., Graaf, I. & Beek, L. High-resolution modeling of human and climate impacts on global water resources. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 8, 735–763 (2016).

Cook, B., Shukla, S., Puma, M. & Nazarenko, L. Irrigation as an historical climate forcing. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1715–1730 (2015).

Yao, Y. et al. Impacts of irrigation expansion on moist-heat stress based on IRRMIP results. Nat. Commun. 16, 1045 (2025).

Yasarer, L., Taylor, J., Rigby, J. & Locke, M. Trends in land use, irrigation, and streamflow alteration in the Mississippi River alluvial plain. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 66 (2020).

Yin, Z. et al. Irrigation, damming, and streamflow fluctuations of the Yellow River. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 1133–1150 (2021).

Wine, M. & Laronne, J. In water-limited landscapes, an anthropocene exchange: trading lakes for irrigated agriculture. Earth’s Future 8, e2019EF001274 (2020).

Oster, J. & Wichelns, D. Economic and agronomic strategies to achieve sustainable irrigation. Irrig. Sci. 22, 107–120 (2003).

Rosa, L. et al. Closing the yield gap while ensuring water sustainability. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104002 (2018).

Rosa, L. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 063008 (2022).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of twenty-first century global irrigation expansion has been in water-stressed regions. Nat. Water 2, 254–261 (2024).

Siebert, S. et al. Groundwater use for irrigation-a global inventory. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1863–1880 (2010).

Scanlon, B. et al. Groundwater depletion and sustainability of irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9320–9325 (2012).

Wang, J., Jiang, Y., Wang, H., Huang, Q. & Deng, H. Groundwater irrigation and management in northern China: status, trends, and challenges. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 36, 670–696 (2019).

Rodell, M., Velicogna, I. & Famiglietti, J. Satellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in India. Nature 460, 999–1002 (2009).

Al-Yaari, A., Ducharne, A., Thiery, W., Cheruy, F. & Lawrence, D. The role of irrigation expansion on historical climate change: insights from CMIP6. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002859 (2022).

McDermid, S. et al. Irrigation in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 435–453 (2023).

Thiery, W. et al. Present-day irrigation mitigates heat extremes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 1403–1422 (2017).

Chou, C., Ryu, D., Lo, M., Wey, H. & Malano, H. Irrigation-induced land-atmosphere feedbacks and their impacts on Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 31, 8785–8801 (2018).

Kang, S. & Eltahir, E. Impact of irrigation on regional climate over Eastern China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5499–5505 (2019).

Lo, M. et al. Intense agricultural irrigation induced contrasting precipitation changes in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064049 (2021).

Alter, R., Fan, Y., Lintner, B. & Weaver, C. Observational evidence that Great Plains irrigation has enhanced summer precipitation intensity and totals in the midwestern United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 16, 1717–1735 (2015).

Haddeland, I. et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3251–3256 (2014).

Leng, G., Huang, M., Tang, Q. & Leung, L. A modeling study of irrigation effects on global surface water and groundwater resources under a changing climate. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 7, 1285–1304 (2015).

Hurtt, G. et al. Harmonization of global land use change and management for the period 850-2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5425–5464 (2020).

Iturbide, M. et al. An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: definition and aggregated datasets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2959–2970 (2020).

Molle, F. & Sanchis-Ibor, C. in Irrigation In The Mediterranean: Technologies, Institutions And Policies (eds Molle, F., Sanchis-Ibor, C. & Avellà-Reus, L.) 279–313 (Springer, 2019).

Bilgen, A. The Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) revisited: the evolution of GAP over forty years. New Perspect. Turkey 58, 125–154 (2018).

Saatsaz, M. A historical investigation on water resources management in Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22, 1749–1785 (2020).

Gu, G. & Adler, R. Spatial patterns of global precipitation change and variability during 1901–2010. J. Clim. 28, 4431–4453 (2015).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018).

Yin, Z. et al. Improvement of the irrigation scheme in the ORCHIDEE land surface model and impacts of irrigation on regional water budgets over China. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001770 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. Implementation and evaluation of irrigation techniques in the community land model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2022MS003074 (2022).

Vanderkelen, I. et al. Evaluating a reservoir parametrisation in the vector-based global routing model mizuRoute (v2. 0.1) for Earth system model coupling. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 15, 4163–4192 (2022).

Taranu, S. et al. Bridging the gap: a new module for human water use in the Community Earth System Model version 2.2. 1. EGUsphere 2024, 1–44 (2024).

Li, Z., Liu, T., Huang, Y., Peng, J. & Ling, Y. Evaluation of the CMIP6 precipitation simulations over global land. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002500 (2022).

Wang, Z., Zhan, C., Ning, L. & Guo, H. Evaluation of global terrestrial evapotranspiration in CMIP6 models. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 143, 521–531 (2021).

Rosa, L., Chiarelli, D., Rulli, M., Dell’Angelo, J. & D’Odorico, P. Global agricultural economic water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6031 (2020).

Dangar, S., Asoka, A. & Mishra, V. Causes and implications of groundwater depletion in India: a review. J. Hydrol. 596, 126103 (2021).

Konikow, L. Groundwater Depletion in the United States (1900–2008) (USGS, 2013).

Xanke, J. & Liesch, T. Quantification and possible causes of declining groundwater resources in the Euro-Mediterranean region from 2003 to 2020. Hydrogeol. J. 30, 379–400 (2022).

Davis, K. et al. Water limits to closing yield gaps. Adv. Water Resour. 99, 67–75 (2017).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. Water savings potentials of irrigation systems: global simulation of processes and linkages. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 3073–3091 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Did water-saving irrigation protect water resources over the past 40 years? A global analysis based on water accounting framework. Agric. Water Manage. 249, 106793 (2021).

Touil, S. et al. A review on smart irrigation management strategies and their effect on water savings and crop yield. Irrig. Drain. 71, 1396–1416 (2022).

Grafton, R. et al. The paradox of irrigation efficiency. Science 361, 748–750 (2018).

Arboleda-Obando, P., Ducharne, A., Cheruy, F. & Ghattas, J. Joint evolution of irrigation, the water cycle and water resources under a strong climate change scenario from 1950 to 2100 in the IPSL-CM6. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-2024-41 (2025).

Rosa, L. & Sangiorgio, M. Global water gaps under future warming levels. Nat. Commun. 16, 1192 (2025).

Rosa, L. et al. Potential for sustainable irrigation expansion in a 3 °C warmer climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29526–29534 (2020).

Wichelns, D. & Oster, J. Sustainable irrigation is necessary and achievable, but direct costs and environmental impacts can be substantial. Agric. Water Manage. 86, 114–127 (2006).

Schmitt, R., Rosa, L. & Daily, G. Global expansion of sustainable irrigation limited by water storage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2214291119 (2022).

Konar, M., Dalin, C., Hanasaki, N., Rinaldo, A. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Temporal dynamics of blue and green virtual water trade networks. Water Resour. Res. 48, W07509 (2012).

Rosa, L., Chiarelli, D., Tu, C., Rulli, M. & D’Odorico, P. Global unsustainable virtual water flows in agricultural trade. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 114001 (2019).

Wang, L., Gao, B., Hu, Y., Huang, W. & Cui, S. Environmental effects of sustainability-oriented diet transition in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 158, 104802 (2020).

Clark, M., Hill, J. & Tilman, D. The diet, health, and environment trilemma. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 109–134 (2018).

Mialyk, O., Schyns, J., Booij, M., Su, H., Hogeboom, R. & Berger, M. Water footprints and crop water use of 175 individual crops for 1990–2019 simulated with a global crop model. Sci. Data 11, 206 (2024).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The community earth system model version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Felfelani, F., Lawrence, D. & Pokhrel, Y. Representing intercell lateral groundwater flow and aquifer pumping in the community land model. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR027531 (2021).

Golaz, J. et al. The DOE E3SM coupled model version 1: overview and evaluation at standard resolution. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2089–2129 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Reconstruction of global gridded monthly sectoral water withdrawals for 1971–2010 and analysis of their spatiotemporal patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 2117–2133 (2018).

Decharme, B., Costantini, M. & Colin, J. A simple approach to represent irrigation water withdrawals in Earth System Models. J. Adv. Modeli. Earth Systems, 17, e2024MS004508 (2025).

Yokohata, T. et al. MIROC-INTEG-LAND version 1: a global biogeochemical land surface model with human water management, crop growth, and land-use change. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 4713–4747 (2020).

Arboleda-Obando, P., Ducharne, A., Yin, Z. & Ciais, P. Validation of a new global irrigation scheme in the land surface model ORCHIDEE v2.2. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 2141–2164 (2024).

Tapley, B., Bettadpur, S., Ries, J., Thompson, P. & Watkins, M. GRACE measurements of mass variability in the Earth system. Science 305, 503–505 (2004).

Schutz, B., Tapley, B. & Born, G. Statistical Orbit Determination (Elsevier, 2004).

Save, H. CSR GRACE and GRACE-FO RL06 Mascon Solutions v02 (GRACE, 2020); https://www2.csr.utexas.edu/grace/RL06_mascons.html

Yao, Y. Yao_et_al_irrigation-induced_land_water_depletion_aggravated_by_climate_change. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29664485.v1 (2025).

Savitzky, A. & Golay, M. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 36, 1627–1639 (1964).

Acknowledgements

The computational resources and services used in this work for the storage and analysis of IRRMIP data were provided by the VSC (Flemish Supercomputer Center), funded by the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO) and the Flemish Government–department EWI. S.J.D.H. acknowledges funding by BELSPO (B2/223/P1/DAMOCO). L.R.L. and T.Z. acknowledge funding from the Office of Science, US Department of Energy (DOE) Biological and Environmental Research through the Water Cycle and Climate Extremes Modeling (WACCEM) scientific focus area funded by the Regional and Global Model Analysis programme area for performing the simulations and analyses, and the E3SM project through the Earth System Model Development programme area for performing the model development. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) is operated for DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. A. Ding acknowledges funding by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 42301363), Anhui Province Youth Science and Technology Talent Lift Program (number RCTJ202404) and Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (number 2308085QD118). Y.P. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (awards 2127643 and 2324837). J.J. was supported by the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Science (GISS) Climate Impacts Group, the Future of Life Institute and the US Department of Agriculture. W.T. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Framework research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 101076909; ‘LACRIMA’ project). The computational resources and services used in this work for the simulations and storage of CESM data were provided by the VSC, funded by the FWO and the Flemish government–department EWI. Y.S. was supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (grant number 22K14101).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. designed the study, performed all analyses and wrote the paper with support and editing from W.T., A. Ducharne, B.I.C., A. Ding, S.J.D.H., P.S., K.S.A., P.F.A.-O., J.C., M.C., B.D., D.M.L., P.L., L.R.L., M.-H.L., N.D., R.-J.W., T.Z., J.J., S.S.M., Y.P., Y.S., T.Y., L.G. and S.I.S. Y.Y. and W.T. coordinated IRRMIP. The IRRMIP simulations were performed by Y.Y., S.J.D.H., P.L. and D.M.L. for the CESM2 model, by R.-J.W., M.-H.L. and Y.P. for the CESM2_gw model, by N.D. and K.S.A. for the NorESM2 model, by T.Z. and L.R.L. for the E3SM model, by P.F.A.-O. and A. Ducharne for the IPSL-CM6 model, by J.C., M.C. and B.D. for the CNRM-CM6-1 model, and by Y.S. and T.Y. for the MIROC-INTEG-ES model. A. Ding pre-processed the GRACE TWS data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks Lorenzo Rosa and F. Lambert for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Area equipped for irrigation and irrigation water withdrawal in four climate reference regions.

Varying evolution in area equipped for irrigation and irrigation water withdrawal in four regions. Area equipped for irrigation (AEI) in the region South Asia (a), Mediterranean (b), Central North America (c), and West Central Asia (d). Annual simulated irrigation water withdrawal (IWW) from seven Earth System Models in four regions of the experiment with (tranirr) and without irrigation expansion (1901irr) (e-h). Solid lines are the mean value of seven Earth System Models, and ranges indicate the maximum and minimum values. Curves indicating irrigation water withdrawal were smoothed using Savitzky-Golay filtering (order=2, window = 19)73.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Impacts of different forcings on precipitation, evapotranspiration, and runoff.

Impacts of all forcings (a-c), other forcings (b, f), and irrigation expansion (g-i) on precipitation (P: a, d, g), evapotranspiration (ET: b, e, h), and runoff (R: c,f,i). The impacts are computed through a comparison of multi-year mean values over different periods or different experiments (see Table 2). Results shown are the multi-model mean value across seven models, and hatches indicate that ≥6 out of 7 models show consistency in the sign of change (≤-20 or ≥20 mm yr−1). Region boundaries in a–i adapted from ref. 31 under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Thiery, W., Ducharne, A. et al. Irrigation-induced land water depletion aggravated by climate change. Nat Water 3, 1424–1435 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00529-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00529-1

This article is cited by

-

Past and future change in global river flows

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Irrigation increased historical land surface and groundwater loss

Nature Water (2025)