Abstract

Plasmids facilitate antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene spread via horizontal gene transfer, yet the mobility of genes in wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) resistomes remains unclear. We sequenced 173 circularised plasmids transferred from WWTP effluent into Escherichia coli and characterised their genetic content. Multiple multidrug-resistant plasmids were identified, with a significant number of mega-plasmids (>100 kb). Almost all plasmids detected existed with other plasmids i.e. as communities rather than lone entities. These plasmid communities enabled non-AMR plasmids to survive antimicrobial selection by co-existing with resistant partners. Our data demonstrates the highly variable nature of plasmids in addition to their capacity to carry mobile elements and genes within these highly variable regions. The impact of these variations on plasmid ecology, persistence, and transfer requires further investigation. Plasmid communities warrant exploration across biomes, as many non-resistant plasmids escape elimination by co-existing with AMR plasmids in the same bacterial host, representing a previously unrecognised survival strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rising threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is of critical importance for worldwide health with the World Health Organisation predicting that the current trajectory of AMR dissemination will lead to a post-antibiotic era within this century1. The threat of AMR can be viewed through the context of One Health as it has been linked to factors related to human, environmental and animal health. Within this framework, it has been shown that wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) can harbour significant reservoirs of antimicrobial resistant bacteria (ARB) and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs)2,3,4,5. These localised concentrations of AMR are considered potential hotspots for the dissemination of ARGs between bacterial populations via horizontal gene transfer through ARGs contained on mobile genetic elements (MGEs)5. Amongst MGEs, plasmids play a consistent role in the dissemination of ARGs within bacterial populations6,7.

Previous WWTP studies have focused on the detection and classification of ARGs and ARB using traditional gene detection methods such as PCR8,9, qPCR10 and culture. While some metagenomic analysis has characterised plasmids in WWTP11, most have focused on identification of the ARGs content. Short-read sequencing of metagenomes does not allow for the best possible characterisation and resolutions of plasmids and their functional composition12. Comparative genomic studies have allowed for the confirmation and quantification of ARGs in diverse metagenomes as well as elucidating potentially coevolving gene groups such as metal resistance genes (MRGs) and virulence factors13,14,15.

Although many studies have generated WWTP resistome data, the question remains as to which of these genes are mobile and which are co-transferred on plasmids. We aimed to answer this question. We resolved and closed circular plasmid sequenced AMR plasmids identified within WWTP effluent that had been previously characterised for ARGs10. We aimed to characterise their ARGs, metal resistance genes, virulence factors, and mobility genes and compare them with databases to evaluate their similarity with plasmids across human, animal, and environmental biomes. By analysing the plasmids present per E. coli we could identify which plasmids co-existed together in a community and which did not. We define the “plasmid community,” as a robust ensemble of plasmids co-existing within a bacterial cell. We have also characterised highly related plasmids and compared the variability of their genetic compositions across the collection of plasmids.

Results

The plasmids identified were circularised, analysed and classified into groups based on their sequence similarity. The sequence sizes of the circular plasmid (n = 173) ranged from 2337 bp to 292,404 bp. Mega-plasmids with a length of over 100 kb encompassed 36% of the plasmids. Antimicrobial resistance and non-AMR plasmids were co-transferred and in some cases were co-dependent on another plasmid for mobilisation. The plasmids were predominantly detected in communities greater than one plasmid within each E. coli and single plasmid occupancy was rare (Supplementary data 1: Plasmid descriptions).

Antimicrobial resistance

Within the community of plasmids sequenced 42% contained at least one ARGs. Across this study of the plasmids a total of 33 different ARGs conferring resistance across ten antimicrobial classes (aminoglycosides, quinolones/fluoroquinolones, macrolides, polymyxins, beta-lactams, rifamycins, chloramphenicols, dihydrofolate synthesis inhibitors, sulfonamides and tetracyclines) were detected (Fig. 1). Multidrug-resistant (MDR) plasmids, with up to 12 ARGs accounted for 73% of the AMR plasmids. No carbapenemase genes were detected. The plasmids containing ARGs were predominantly conjugative, two exceptions were a 5481 bp ARGs plasmid was non-mobilizable and the ARGs containing 5553 bp and 3463 bp were both mobilizable (Supplementary data 1: ARGs).

A block of light brown indicates the presence of one of the 33 different ARGs on the plasmid. The inner ring describes each plasmid by name and is coloured by group. Indicative plasmids with no ARG (only black blocks present) are included to demonstrate the presence of related plasmids with no ARGs. The phylogenetic tree shows the relatedness of the plasmids. Most plasmids contained more than one ARG and were predominantly MDR plasmids.

The total DNA extracted from the same WWTP effluent samples had previously been analysed for ARGs using qPCR arrays and microbiome content and the samples for antimicrobial chemical composition10,16,17. The ARGs detected in the previous study of the same WWTP effluent samples via qPCR array analysis correspond with those detected on the plasmids (Supplementary data 1: ARG_qPCR). The ARGs not detected on the plasmids in this study included chromosomally mediated efflux pumps e.g. mexB or those detected in Gram-positive bacteria e.g. vanB. The lack of the efflux pump genes is most probably due to the fact that this study analysed only plasmids and not chromosomes, where these genes reside. The vanB gene is found in Gram-positive bacteria. One limitation of this study is the use of the Gram-negative bacteria E. coli as the only plasmid capture bacteria. Thus, the lack of the ARGs detected in Gram-positive bacteria may be due to the lack of Gram-positive plasmid capture host in this study. In addition, two Inc genes (incN and incP) detected using qPCR were also detected on the plasmids. The ARGs qnrB and tetB were detected on the plasmids but not detected in the previous analysis using qPCR arrays. Thus, the plasmid ARGs analysed were representative of those present on Gram negative bacterial plasmids detected using qPCR.

The colistin resistance gene mcr-9 was detected on highly related plasmids all over 285Kb (s25–s31). These plasmids also contained aminoglycoside (aac(3)-IIb, aac(6’)-IIc, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id), beta-lactam (blaTEM-1), extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) (blaSHV-134), trimethoprim (dfrA19), tetracycline (tetD), macrolide (ereA2) and sulphonamide (sul1) resistance genes (Fig. 1). Five of the seven mcr-9 positive plasmids also contained the quinolone resistance gene qnrA which and two copies of sul1. No other plasmids in this study contained qnrA genes. They were contained on plasmids of replicon groups IncHI2A, IncHI2 and RepA. The mcr-9 gene was flanked by IS5-like element IS903B and an IS6-like element IS26. In two plasmids the qnrA gene and one copy of sul1 was absent due to an absence of a 3147 bp section of plasmid. These plasmids also contained genes conferring resistance to up to 24 different metals, including arsenic, mercury, nickel, lead, copper, potassium tellurite and the biocide quaternary ammonium compounds (Fig. 2; Supplementary data 1: Metal_Resistance). No virulence genes were detected.

A block of green indicates the presence of one of the different metal or biocide resistance genes on the plasmid. The inner ring describes each plasmid by name and is coloured by group. Indicative plasmids with no metal nor biocide resistance genes (only black blocks present) are included to demonstrate the presence of related plasmids lacking these genes. The phylogenetic tree shows the relatedness of the plasmids. Where multiple metal resistance genes were identified they were predominantly operons of genes conferring resistance to one metal e.g. mercury resistance and not multiple metals.

The fluoroquinolone resistance genes aac(6’)Ib-cr and qnrB genes were only detected together on the same plasmid (Fig. 1). They were present on 54 - 55Kb, IncN replicon group plasmids together with genes conferring resistance to aminoglycosides (aadA16), trimethoprim (dfrA), sulphonamide (two copies of sul1) and tetracycline (tetA). These resistance genes, except tetA, were contained on a class 1 integron. No metal resistance nor virulence genes were detected, only the biocide resistance gene qacEdelta1 (Fig. 2).

Beta-lactam resistance genes blaTEM-1, blaTEM-122, blaTEM-150 and ESBL genes blaTEM-12 and blaSHV-134 were detected across many plasmids (Fig. 1). The ESBL blaSHV-134 and beta-lactamase blaTEM-1were the only co-occurring beta-lactamase gene. These co-occurrences were present with mcr-9 and other genes as previously described. Where the blaTEM-1 gene was present in the absence of blaSHV-134 it was detected on plasmids with aminoglycoside (aph(3’)-Ia) and tetracycline resistance (tetB) genes, a mercury resistance gene operon comprising seven genes and the virulence gene senB (toxin) but without the senB associated cjrABC co-transferred genes associated with virulence in E. coli (Supplementary data 1: Virulence_Factors). The blaTEM-1gene was detected on another plasmid with chloramphenicol resistance (catI) and no metal resistance nor virulence genes. The remaining blaTEM-1 plasmids contained no additional antimicrobial, metal resistance nor virulence genes. The blaTEM-122 and blaTEM-150 were present on different plasmids but each plasmid also contained aminoglycoside (aac(3)-IIe and ant(3”)-IIa), trimethoprim (dfrA1), sulphonamide (sul1), and tetracycline (tetA) resistance genes. These plasmids also contained metal resistance genes conferring resistance to mercury, quaternary ammonium compounds and potassium tellurite but no virulence genes. The blaTEM-12 gene was present with no other ARGs and no metal resistance nor virulence genes on one plasmid and with aminoglycoside (ant(3”)-IIa) and macrolide (mphE and msrE) resistance genes and biocide resistance gene qacE on another plasmid. When blaSHV-134 was present in the absence of blaTEM-1 it was on plasmids also containing aminoglycoside (ant(3”)-IIa, aadA2), chloramphenicol (cmlA), sulphonamide (sul3) and tetracycline (tetA) resistance genes. They also contained the biocide resistance qacF gene but no metal resistance genes and no virulence genes. The plasmids containing the beta-lactamase/ESBL genes contained a wide variety of replicon types: IncHI2 and IncHI2A with repA, IncFII, IncFII with IncI1, IncA/C2, IncFIA with IncFIB and IncFII or ColRNAI. Only resistance plasmids from the IncN replicon group or those containing no AMR genes contained no beta-lactamase genes.

Aminoglycoside resistance genes were detected in the presence of mcr-9, quinolone resistance genes or beta-lactam/ESBL genes. There were no plasmids which contained only aminoglycoside resistance genes. Macrolide, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim and sulphonamide resistance genes were also never detected alone. With the exception of one instance of tetA, which was detected with no other AMR genes, nor replicon type and on a small (<6Kb) plasmid, the tetracycline resistance genes were also not detected as the sole ARGs on a plasmid.

The plasmids lacking ARGs but with metal resistance genes formed two groups; one group of conjugative plasmids (140 kb) with a seven gene mercury resistance operon and no virulence genes and replicon group IncFII (25_4, 26_3, 27_3, 28_3, 29_4, 30_9, 31_5) (Fig. 2). The other group were 139Kb conjugative plasmids containing sitABC genes (iron transport system) and virulence genes icsP/sopA, the iroBCDEN and iucABCD operons and iutA on IncFIB and IncFIC plasmids. The iron transport system (sitABC) is classified as a virulence factor in addition to a metal resistance mechanism.

The plasmids which contained no ARGs, metal resistance nor virulence genes varied in size from 2337 bp to 113,760 bp. The S32_20 plasmid was the largest at 113,760 bp, a non-mobilizable plasmid containing three phage types. This was essentially a plasmid of phage and contained an IncFIB replicon. Within this group of plasmids only the 56Kb was a conjugative plasmid, which contained the IncX replicon. The remainder of the plasmids above 7000 bp were approximately 34 Kb. The 34 Kb plasmids were IncP, and mobilizable but non-conjugative. They all contained heat resistance genes, which may serve as the selective pressure for their persistence (Supplementary data 1: Bakta). Most of the plasmids less than 7KB contained a Col replicon but some contained no replicon. Most of these small plasmids were mobilizable but the 2337 bp plasmids were non-mobilizable. The reason for the maintenance or transfer of these small plasmids is unclear as they do not appear to provide any known advantage nor function to the bacterial host.

Toxin-antitoxin systems

Detection of toxin-antitoxin system (TAS) related features identified 32 distinct genes. These genes were located across the entire plasmid group with larger plasmids containing a more diverse collection. Some smaller plasmids that were classed as non-resistant were identified to contain complete TAS such as the ccdA and ccdB system. There were also several instances where plasmids contained a single TAS feature or no TAS genes at all (Fig. 3; Supplementary data 1: Toxin_Antitoxin).

A block of blue indicates the presence of one of the different toxin anti-toxin genes on the plasmid. The inner ring describes each plasmid by name and is coloured by group. Indicative plasmids with no toxin anti-toxin genes (only black blocks present) are included to demonstrate the presence of related plasmids lacking these genes. The phylogenetic tree shows the relatedness of the plasmids.

Global relatedness and enrichment analysis

The entire PLSDB plasmid dataset was clustered with the 173 plasmids (Fig. 4). A distance score of 0.1 is assumed to equate to ≥90% ANI. Using species level taxonomic association, the plasmids in this study were clustered significantly more with PLSDB plasmids associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli. It is important to note that the plasmids were captured in E. coli, which indicates the species association of plasmids. Significantly P( < 0.005) less clustering was determined with PLSDB plasmids associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas putida, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus mirabilis, Yersinia enterocolitica, Aeromonas salmonicida, Aeromonas caviae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Cronobacter sakazakii, uncultured bacterium and Enterobacter roggenkampii. The plasmids in this dataset were found to cluster more significantly P( < 0.005) with PLSDB plasmids associated with bovine faeces, cattle, ground turkey, pig farm pigs and human stool and urine samples while clustering significantly less with PLSDB plasmids associated with human blood and rectal swabs, food, sewage, soil, and water (Supplementary data l: PLSBD_matches).

Each circle is a plasmid, and each cluster of the same coloured circles are highly related plasmids. The circles with black labels are from this study and those with yellow labels are from PLSDB i.e. global plasmids. The lines between the circles indicate high levels of relatedness. The links between the clusters indicate commonality across the plasmids contained in the clusters. Several clusters of plasmids from this study are unique and not connected to plasmids in PLSDB but are related to each other e.g. light blue cluster.

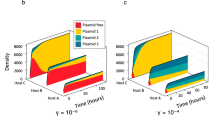

By analysing the plasmids present per E. coli we could identify which plasmids co-existed together (communities) and which did not. Four conjugative mega plasmids (224 Kb, 139 Kb, 102 Kb and 96 Kb) co-existed in the same E. coli (Table 1). In addition, subsets of these plasmids existed together either as three plasmids e.g. E. coli S3, which lacked the 96Kb plasmid, but contained 4 additional small plasmids (each less than 5Kb) or E. coli S42 which contained three plasmids and lacked the 224 Kb plasmid and E. coli S43 was missing the 139 Kb plasmids but neither contained additional plasmids (Supplementary data 1: Plasmid_descriptions). These plasmids contained the replicon groups IncH1, IncH 2 and RepA (224 kb), IncFIB and FIC (139 Kb), IncFII (102 Kb) and IncFII and IncI1 (96 Kb). There was very little overlap in the ARGs content across this co-existing community plasmids, only the ant(3”)-IIa and tetA were present in two plasmids (224 Kb and 102 Kb) (Supplementary data: ARG). All plasmids were selected on tetracycline. The two plasmids lacking tetracycline resistance genes were only able to survive in the E. coli due to the presence of those with tetracycline resistance genes. The non-tetracycline resistance plasmids contained either only the blaTEM-1 or no ARGs (96 kb and 139Kb, respectively). While virulence genes were co-transferred with ARGs they were not transferred on the same plasmid. The E.coli containing the 224 Kb, 139 Kb, 102 Kb plasmids contained four additional small plasmids (2337, 3463, 4358 and 4927 bp). However, when the 96Kb plasmid was a component of the plasmid community no small plasmids were present.

There were two further sets of community pairs of mega plasmids. One comprised two plasmids of 287 or 292 Kb and 140 Kb with or without small plasmids and the other a 178 Kb and 117 Kb plasmid with a 5.5 Kb plasmid (Table 1). The plasmids belonged to different replicon groups 1) IncHI2A, IncH2B, RepA (287/292Kb) and IncFII (140 Kb) and no replicon group (6 Kb) and 2) IncIA/C2 (178 Kb) and no identified replicon groups in 117 Kb or 5.5 Kb plasmids. The 287/292Kb plasmids carried 11 or 13 different ARGs, including tetD conferring tetracycline resistance on which the colonies were selected, while the 140 Kb plasmids contained no ARGs. Both the 287/292 Kb and 140 Kb plasmids contained mercury resistance genes and the 290 KB plasmid additionally contained a further 17 metal resistance genes. The plasmids 287/292 Kb and 140 Kb co-existed with a 5553 bp small plasmid, which was not detected in any other sample or with the three small plasmids (3463, 4358, 6314 bp) together or with no small plasmids.

The 178 Kb plasmid contained ARGs ant(3”)-IIa, mphE, msrE and blaTEM-12 and the 117 Kb plasmid contained only blaTEM-12. Escherichia coli isolates containing these plasmids were selected on ampicillin, enabled by the blaTEM-12 genes. The 178 Kb plasmid contained the qacE gene. This plasmid community also contained a 5481 bp small plasmid, which was not detected in any other sample.

A community of medium sized plasmids (34, 55, 56 Kb) were also detected with non-mega plasmids in E. coli isolates. The E. coli containing these plasmids also contained up to five different small plasmids (Table 1) either all together in one isolate or a subset of the small plasmids across isolates. All of the detected small plasmids were also detected in the isolates containing mega plasmids, which suggests that the small plasmids were not aligning themselves with plasmids of a certain size nor selective trait. No isolates contained only small plasmids, even those that contained the selective resistance gene.

Escherichia coli containing the community of 96 Kb, 114 Kb or 144 Kb plasmids existed without small plasmids (Table 1). There was no pattern of a specific replicon group present on the plasmid communities that lacked small plasmids in comparison with those containing small plasmids. For example the replicon groups of mega plasmids transferred with 3463 bp plasmid were IncF, IncH and RepA. The replicon groups of the 114 Kb or 144 Kb plasmids were IncF and the 96 Kb plasmid contained IncF and IncI. There was no distinct pattern of gene content across the small plasmids to indicate why they were not part of the same community as certain larger plasmids. There was also no distinct pattern across the 96 Kb, 114 Kb or 144 Kb plasmids to indicate why the small plasmids were not transferred with only these plasmids. All were conjugative plasmids. The only unusual finding was the presence of three phages in the sample containing the 114 Kb plasmids. If this is a phage plasmid this suggests that phage plasmids are not present in plasmid communities with other plasmids. The 114 Kb and 144 Kb plasmids were the only plasmids detected solely as single plasmids in the samples.

Plasmids genetic rearrangements

Due to the methodology used we have sequenced and selected several groups of highly similar plasmids. When the plasmids were analysed however they were not identical and many contained genetic rearrangements.

Each similar plasmid was grouped together. There was more genetic variation within the small plasmids groups than large plasmids groups. Group 0 contained 18 plasmids all 4358 bp in length (Supplementary data 1: Plasmids descriptions). There were reshuffling and inversion events present across the plasmids. Within group 0 there were three basic sets of gene arrangements (Table 1 in Supplementary data 2). The presence of mbeD gene in plasmid s11_53 is of interest as it is suggested to be required for plasmid mobilisation18. This is based on similarities between TraM and MbeD and as the TraM is known to bind to one site at oriT of the ColE1 plasmid the MbeD would play a role in initiating plasmid transfer in the donor cells18. These all contained the col replicon groups.

Group 1 comprised seven plasmids of 2337 bp length. The rearrangement events were described as inversions and reshuffling events (Supplementary data 1: Bakta, Supplementary data 2). Each plasmid consisted of an RNAi and two hypothetical genes (hypothetical gene 1 and hypothetical gene 2): in S21_217 one hypothetical genes was 185 bp and in S17_40 and S3_14 it was 368 bp and the remainder (13_53, 14_44, 22_135 and 23_50) it was 542 bp. There were unaligned beginning events in plasmids S17_40 and S3_14 of four nucleotides. The reshuffling events occurred in plasmids S13_53 compared with 14_44 and S21_217 compared with S17_40 only. One of the reshuffling events were between the start of one plasmid and the end of the other in regions of the plasmids that were not annotated as having a specific function. The other reshuffling events were along the ncRNA RNAI and one hypothetical gene (S13_53). There were no shuffling events in the second hypothetical gene region in S13_53. However, the plasmids S22_135 compared with S3_14 or S23_50 contained reshuffling events in this region. Most plasmids contained a reshuffling event of approximately half the length of the plasmids in comparison with the others in the specific groupings above. Inversions occurred across the two groups comprising 1) S13_53, S14_44, S21_217 and S17_40 and 2) S22_135, S3_14, and S23_50. There were no inversion events within the groups e.g. none between S13_53 and S14_44. The inversion events occurred across the entire plasmids and ranged in size from 180 bp to 2155 bp, which are the same inversions.

Group 2 comprised nine plasmids of 3463 bp length and different gene combinations (Table 2 in Supplementary data 2). In four cases the mobC was replaced by a hypothetical gene and in one plasmid the lipoprotein gene was replaced by a hypothetical gene. mobC is a mobility gene, required for the transfer of the plasmid in the presence of a conjugative plasmid.

Group 3 comprised a group of 14 plasmids 4927 bp in size (Table 3 in Supplementary data 2). Some plasmid pairs were identical and contained no rearrangements (S10_69 and S23_47, S19_38 and S22_120, S13_50 and S16_31). The identical plasmids were isolated from different samples, for example, S23_47 from WWTP1 at timepoint 1 and S10_69 from WWTP1 timepoint 3, which was six months later than timepoint 1.

Group 4 comprised 13 plasmids all 6314 bp in length with unaligned beginning or end, inversions and reshuffling events. These small plasmids, except 12_42 and 25_8, contain the traD gene (Table 4 in Supplementary data). TraD is a hexameric ring ATPase that forms the cytoplasmic face of the conjugative pore and it interacts with TraM.

The Group 5 plasmids (n = 16) plasmids comprised two sub-groups. There were no statistical differences between S9_32, S10_33, S12_25, S18_28 and S19_22 (Supplementary data 2). There were also no changes between plasmids: S11_31, S13_30, S14_22, S15_23, S16_21, S17_20, S20_28, S21_28, S22_30, S23_26 and S24_31 (Supplementary data 2). When plasmids in both groups were compared all rearrangement events were within the origin of replication, which comprise collapsed repeats, tandem duplications, collapsed tandem repeats, deletion, insertion and duplication events.

Group 6 contains seven plasmids. They are identical to each other. These plasmids contained no AMR genes, but contained mercury resistance genes and were 140,332 bp in length. All plasmids contained insertion sequences and transposons but there were no variations within the plasmids. Co-existing plasmids in the same community as group 6 contained rearrangements e.g. Group 7. Thus, the rearrangements were not inhibited by the host E. coli. The plasmids in group 7 were 224Kb (n = 14), 287 Kb (n = 2) or 292Kb (n = 5) in size. The plasmids of the same sizes were identical, resulting in three different plasmid types in this group (Supplementary data 2). In the 224 Kb plasmids relocations with insertions were mainly based around IS elements or transposons that differ in the 224 Kb plasmids in comparison with the other two plasmids 287 Kb or 292 Kb. While they were all IncH plasmids with many conserved genes across the plasmids the sizes of DNA variation was relatively large. For example a fragment of 11,214 bp was inserted into plasmids at the same location across the 287 Kb or 292 Kb plasmids in comparison with the 224 Kb plasmids or in reverse a deletion of 11,214 bp occurred in the 224 kb at location 23,079 bp. While only 5Kb differed between plasmids 287 Kb and 292 kb the genetic variation was distributed across different sections of the plasmid via insertions and deletions. One example was a region of 4952 bp insert in 292 Kb (at location 229,318 to 234,270 bp), which was absent from 287 Kb. This region encoded an additional sul1, hypA (hydrogenase maturation factor), ampR, qnrA and an IS91 encoded by rPS27A. At the same location and prior to these genes both plasmids contained rPS27A. In a previous study the insertion of qnrB beside/near oriC resulted in increased bacterial mutation rate and suggested that qnrB acts as a DNA replication initiation activator19. However, there were no mutations in oriC genes of the plasmids in our study. The Group 10 plasmids comprised 14 different plasmids ranging in size from 96,358 bp to 97,016 bp with the replicon groups IncI and IncFII (Supplementary data 1: plasmid_descriptions, replicon). This is the only group of plasmids to contain the shufflon. Shufflons are present on IncI plasmids. The shufflon provides variety to the tip of the PilV adhesin. PilV recognises specific lipopolysaccharide structures on the surface of the recipient cell during mating20,21. Within this group of plasmids rearrangements or changes occurred only within the shufflon region between 78,901 and 80,359 bp across all plasmids (Supplementary data 2). The event length ranged from 12 bp to 348 bp deletions or insertions within this region. There were no other rearrangements on these plasmids. Group 13 contained two identical plasmids: S46_2 and S47_2, which had no rearrangements. Group 14 shared a large proportion of genes that are not replicons nor ARGs. Based on the identical nature of plasmids of the same size, group 14 comprised three groups. 14 A: 144,214 bp (n = 2), 14B: 138,989 bp (n = 14), and 14 C: 101594 bp (n = 15) (Supplementary data 2). In Group 16 (n = 16) there were no AMR, metal resistance, nor virulence genes present. They were all IncP plasmids. Plasmids of the same size were identical. This resulted in seven unique plasmids for rearrangement comparisons. All rearrangements within this group comprised tandem duplications or collapsed tandem repeats within the region of the origin of replication. The rearrangements varied in size from 50 bp to 332 bp. All tandem duplications ended at 1745 bp and varied in length from 145 bp to 264 bp and all occurred in the origin of replication. No rearrangements were detected in the other regions of these plasmids.

When analysing the rearrangements of large plasmids three patterns emerged:

-

1.

All plasmids within a group of IncF plasmids or IncA/C were identical i.e. no rearrangements occurred.

-

2.

Plasmids contained rearrangements close to or within the origin of replication in IncH or IncN or IncP plasmids

-

3.

Plasmids rearrangements were limited to within the shufflon, on the IncI plasmids

Discussion

Most studies of environmental biomes have focused on ARGs, cultured bacteria or chemical analysis of antimicrobials when addressing the question of AMR presence and potential transmission. While these data provide some of the information required the mobility of the ARGs remains ambiguous. As analysis of AMR plasmids predominantly focused on those of AMR pathogens we have a bias in our current knowledge of plasmid mediated AMR. In addition, research to date almost exclusively focused on the analysis of single AMR plasmids within pathogens. Knowledge concerning the ecology of AMR plasmids has followed, predominantly focusing on single AMR plasmids in pathogens. However, we must focus on the reality of AMR plasmids, which is the ecology of plasmids as they exist in nature in both commensal and pathogenic bacteria. Researchers, and this study have identified that AMR plasmids co-exist in the same bacterial cell22,23,24,25. We have found that the diversity of plasmid sizes and types composing the plasmid communities is very large and there were no distinct patterns of co-existing plasmid communities. However, most of our knowledge of AMR plasmids is still based on single plasmids24. While there are also microbe–plasmid communities that should be considered as complex adaptive systems, this study focused initially on describing the AMR plasmid communities capable of co-existing within the E. coli cells26. In addition, metagenome assembled genome analysis is possible but it is still difficult to assemble circularised complete plasmids from these data due to a bottleneck in metagenomic data assembly27.

We analysed a wide array of AMR plasmids from WWTP effluent for which we already knew there was a range of ARGs present and through hybrid sequencing of each plasmid provided a complete plasmid map of the circularised plasmids. Limitations of this study are the use of only E. coli as the recipient host for the plasmids and selection of AMR plasmids. This results in the analysis of AMR selected plasmids capable of survival in E. coli and not e.g. plasmids in Gram-positive bacteria. Thus, the absence of data in this study does not indicate that the plasmids do not exist within the samples, but that we have not yet generated circularised plasmids for all plasmids within the samples. Through analysis of the circularised plasmids we then identified the co-selection genes that were transferred alongside the ARGs. Thereby providing a greater understanding of the potential selection and transmission of these plasmids. In addition, we provided an analysis of co-existing plasmid communities. In the process of the analysis we identified that multiple plasmids were present in E. coli together. These data suggest to us that plasmid analysis and that of AMR plasmids may be more representative of the real world situation when they are analysed as communities, rather than analysing only the single AMR plasmids, and as such will be discussed in this manner with the aim of understanding what traits may be moving together as plasmid communities.

A wide array of ARGs were detected on the sequenced plasmids, including clinically important ESBL genes, colistin resistance and fluoroquinolone resistance genes. However, no carbapenemase genes were detected. The ARGs clustering together on the same plasmid and frequently on the same mobile element suggests that ARGs are moving as groups across bacteria rather than being integrated individually into the plasmid. The prominence of plasmids lacking ARGs, metal resistance genes and virulence factors is of particular note within this study. The classification of 46% of isolated plasmids that appear to persist despite having no apparent selective advantage nor confer a selective marker has not been previously noted. Despite some Toxin Anti-toxin-systems being identified which may explain their presence, most of these non-resistant plasmids did not contain any genes which could be found to account for their persistence. Most of these plasmids could be classified as mobilisable which in association with their smaller size could lead to persistence via co-transfer with the larger conjugative mega plasmids that were co-transferred. The presence of currently unidentified genes that could pertain to their ability to survive is also possible due to the large number of hypothetical genes that were identified on these plasmids. The ancestry of these plasmids also showed that they form distinct groups unrelated to those that contain known drivers of persistence such as ARGs. This suggests that the plasmids have not likely previously held ARGs and instead have evolved separately and consequently must have their own factors for persistence and survival. This observation leads to the possibility that these non-resistant plasmids are more common than expected and could have been inadvertently ignored in previous studies due to the studies focus on ARGs determination and short-read exclusive sequencings inability to fully resolve circularised plasmids thus leading to their characterisation as fragmented assemblies12.

The quantity of plasmids that could be classified as mega plasmids was of particular importance due to the elevated levels of clinically relevant ARGs present. This dataset was shown to be statistically enriched for mega plasmids when compared to PLSDB and therefore questions arise as to the reasons for their presence and ability to persist despite their hypothesised metabolic cost to their host. The distribution of mega plasmids analysed across families identified that Pseudomonadaceae, Rhizobiaceae, Burkholderiaceae and Enterococcaceae had distinct mega plasmid “peaks” in their distribution. Thus, these families appeared to have a larger than average proportion of mega plasmids relative to other sized plasmids28. Escherichia coli is in the family Enterobacterales and thus not included in these families. In a previous study using the same samples as in this study we demonstrated that Irish WWTP effluent has been shown to contain some of the highest antibiotic concentrations in Europe and this could provide a setting where the collective selective pressure against multiple antimicrobial classes allows for the development and perseverance of MDR mega plasmids17. The plasmids also contained a large number of metal resistance and virulence factors, which could possibly bring about survival through effective mutualism with their host, when present in pathogenic bacteria. Some however, contained toxin anti-toxin-systems that would suggest a more parasitic persistence coevolutionary synergy29. The plasmids large size, multiple interspersed incompatibility groups, and polarised compositional distances between otherwise unrelated plasmids could also suggest that these mega plasmids were the result of the fusion of smaller plasmids coexisting in the WWTP environment.

Our analysis of gene rearrangements across the highly similar plasmid within the population of plasmids analysed has provided further insights into how plasmids exist within E. coli within a complex biome and how they vary when compared with each other. This type of analysis has not to our knowledge been performed with plasmids as they are usually not analysed in this manner. We expected rearrangements to be proportional to plasmid size i.e. large rearrangements in the large plasmids, including loss of segments containing ARGs, as they are frequently present on mobile elements. However, genetic rearrangement was not proportional to plasmid size. The shufflon containing plasmids were large conjugative plasmids but the region of variation was restricted to beside or within the shufflon region. The shufflon provides variety to the tip of the PilV adhesin. PilV recognises specific lipopolysaccharide structures on the surface of the recipient cell during mating20. The level of variation was higher in the small (<7 Kb) plasmids than the larger plasmids, which demonstrates that while they are highly conserved in their size their content moves or some is lost. If large plasmids are assumed to confer a larger replicative burden, then large plasmids have a comparatively smaller barrier to incorporating new genes. However, this was not the case in this study. Across all plasmids the variations in gene content occurred most frequently at the region around or within the origin of replication. What this data demonstrates is the highly variable nature of plasmids in addition to their capacity to carry mobile elements and genes within these regions provides them with the capacity to co-exist in nature in several different versions. The impact of these variations is currently unknown but it opens an area of further study to understand the impact of such variations on plasmid ecology, persistence and transfer. As genetic changes are required for adaptation these variations are important in understanding how they are selected and how they drive plasmid and plasmid community evolution. Genetic rearrangements have been discussed in the context of recombination errors where plasmids are linearised first and then recombined in E. coli30. If this occurs then recombination error may lead to a wide variety of plasmid rearrangement and could explain some of the changes in the plasmids30.

The plasmid size was not a limiting factor in the plasmid communities with up to four mega plasmids co-existing in one community. Plasmid communities comprised multiple plasmids with genes conferring resistance to the same antimicrobial or metal or plasmids. How would this be an advantage to the bacterial host if carrying more plasmids confers more cost to the host but does not provide more protection or advantage? In addition, plasmids with ARGs existed in communities with plasmids containing no identifiable selective trait. This community provides the plasmids lacking the selective trait the ability to hide and be protected from the antimicrobial without themselves having to carry the ARGs. However, how the host bacteria gain from the carriage of the additional plasmid is unclear. Small plasmids frequently co-existed with large plasmids and with other small plasmids. In some plasmid communities, the small plasmids were present only when one large plasmid was lost, suggesting an exclusion property of the small plasmids on the large plasmids or vice-versa.

These data demonstrate that we need to change our understanding of plasmids. We need to change from analyzing one or two co-existing plasmids in vitro to investigating the real-world to describe the plasmid co-existing communities. We now have the technology to do this, and these plasmids should be used to understand plasmid dynamics and to re-understand our basic knowledge of plasmids as entities that exist within bacteria as communities. This is vital to understand the ecology and evolution of plasmids and to understanding the transmission of ARGs from and to the environment or complex biomes. This knowledge is also vital to assess the risk of transmission of ARGs and their global impact on human, animal or environmental health.

Our study offers a novel understanding of the WWTP effluent plasmidome. The evidence provided suggests that the current knowledge of mega plasmids in particular should be expanded through the use of next generation sequencing technologies that fully elucidate their genetic composition. Our data indicates that plasmids exist predominantly as communities rather than single entities. This needs to be further explored across biomes as we identified many plasmids hiding with AMR plasmids and thus are escaping elimination by co-habiting the same E. coli or multiple plasmids providing the same selective advantage.

Methods

Sample collection

Effluent collected from two WWTPs were used as the source of plasmids to be transferred into Escherichia coli. The WWTPs and the AMR genes detected are previously described10. Exogenously extracted plasmids were transferred to E. coli from WWTP effluent samples (nsamples = 43) using previously described methods31. Briefly, the transferable plasmid populations from each of the ‘donor’ WWTP effluent samples were individually transferred to the ‘recipient’ rifampicin-resistant E. coli DH5α via biparental mating. Exogenous transconjugants were selected on Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) agar (Sigma) with rifampicin (100 mg l−1) and ampicillin, tetracycline, or colistin at CLSI guidelines breakpoint concentrations for E. coli32. Transconjugants were selected from the resulting plates and stored in glycerol stocks at −80 °C.

DNA extraction and sequencing

Plasmid extractions were performed using the Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Plasmid kit following the low-copy number protocol according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Illumina short-read sequencing was performed with plasmid extractions and the quality assessment using NanoDrop and Qubit as per the sequencing centre (Novogene) guidelines. Extracted DNA was sequenced by Novogene using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with PE150 and Q30 ≥ 80%. This provided far greater than 100X coverage for each plasmid. Long-read sequencing was performed on all extracted plasmids using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION. Ligation library preparation was performed using the SQK-LSK-109 Ligation Sequencing kit according to the protocols. Multiplexing was performed with the NBD-104 Barcoding kit.

Sequencing data quality control, assembly and annotation

Raw short reads were filtered and trimmed using Cutadapt v.3.033. Raw long reads were processed using Filtlong v.2.034 for size and quality, with demultiplexing steps and adapter removal utilising Guppy v.6.1.235. Hybrid assembly was performed using Unicycler v.0.5.036 with default settings. Visual assessment of assembled contigs was performed with Bandage v.0.8.137. This allowed for an easy inspection of circularised contigs. Plasmid identification among consensus sequences was performed using Platon v.1.5.038 utilising default settings. Each circularised plasmid was annotated using BAKTA v.1.2.2 using default settings39.

Sequencing data analysis

Each circularised plasmid was analysed using ABRicate v.1.0.140 for ARGs using the Comprehensive Antimicrobial Resistance Database (CARD) v.3.0941, for metal and biocide resistance with BacMet v.2.042 (using a previously published back translated dataset43), for virulence factors using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) v.0.544 and plasmid replicon type was determined using PlasmidFinder v.2.145. The predicted plasmid mobilisation was determined using the MOB-Suite, MOB-Typer v3.0.346 with default settings. Toxin-antitoxin systems (TAS) were characterised using the TASER analysis pipeline provided by the TASmania TAS database47.

The genomic similarity of each circular plasmid was assessed against all plasmids in PLSDB v.0.1.7 using the distance Mash dist algorithm in Mash v.2.2.248. Mash combines the high specificity of matching-based approaches with the dimensionality reduction of statistical approaches, enabling accurate all-pairs comparisons between many genomic entities. Instances where both the distance score (D) and P-value (P) ≤ 0.1 were considered homologous and retained for further inspection. Each retained hit was further annotated using the metadata provided by PLSDB. The 0.1 score filters were chosen to replicate the cut-offs used during the construction of PLSDB v.0.1.749. The MASH distance score is highly correlated to the average nucleotide identity (ANI; a pairwise measure of genomic similarity between two genome’s coding regions subtracted from 1 (1 − ANI) and a distance score of ≤0.05 equates to a ≥ 95% ANI48. A distance score of 0.1 is assumed to equate to ≥90% ANI.

The first clustering of plasmids found them to be in a small number of groups using rounds of sequence comparisons using NUCmer50. The data was then reformatted to generate the coordinates on both plasmids using the NucDiff wrapper around NUCmer51.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI BankIT and are listed according to the plasmid names in the supplementary data sheet and the manuscript. The Genbank accession numbers in NCBI are: PQ040465, PQ040466, PQ040467 - PQ040472, PQ040473 - PQ040504, PQ040505 - PQ040525, PQ040526 - PQ040558, PQ040559 - PQ040590.

References

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112642 (2014).

Rizzo, L. et al. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 447, 345–360 (2013).

Chu, B. T. T. et al. Metagenomics Reveals the Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plants on the Dispersal of Microorganisms and Genes in Aquatic Sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e02168–17 (2018).

Alexander, J., Hembach, N. & Schwartz, T. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance dissemination by wastewater treatment plant effluents with different catchment areas in Germany. Sci. Rep. 10, 8952 (2020).

Li, Q., Chang, W., Zhang, H., Hu, D. & Wang, X. The Role of Plasmids in the Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Transfer in ESBLs-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated From Wastewater Treatment Plants. Front Microbiol. 10, 633 (2019).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00088–17 (2018).

Ebmeyer, S., Kristiansson, E. & Larsson, D. G. J. A framework for identifying the recent origins of mobile antibiotic resistance genes. Commun. Biol. 4, 8 (2021).

Ferro, G., Guarino, F., Castiglione, S. & Rizzo, L. Antibiotic resistance spread potential in urban wastewater effluents disinfected by UV/H2O2 process. Sci. Total Environ. 560–561, 29–35 (2016).

Mao, D. et al. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in two municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 85, 458–466 (2015).

Pärnänen, K. M. M. et al. Antibiotic resistance in European wastewater treatment plants mirrors the pattern of clinical antibiotic resistance prevalence. Sci. Adv. 27, eaau9124 (2019).

Li, A. D., Li, L. G. & Zhang, T. Exploring antibiotic resistance genes and metal resistance genes in plasmid metagenomes from wastewater treatment plants. Front Microbiol. 6, 1025 (2015).

Arredondo-Alonso, S., Willems, R. J., van Schaik, W. & Schürch, A. C. On the (im)possibility of reconstructing plasmids from whole-genome short-read sequencing data. Microb. Genom. 3, e000128 (2017).

Li, L.-G., Xia, Y. & Zhang, T. Co-occurrence of antibiotic and metal resistance genes revealed in complete genome collection. ISME J. 11, 651–662 (2017).

Shaw, L. P. et al. Niche and local geography shape the pangenome of wastewater- and livestock-associated Enterobacteriaceae. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe3868 (2021).

Abe, K., Nomura, N. & Suzuki, S. Biofilms: hot spots of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in aquatic environments, with a focus on a new HGT mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 96, 31 (2020).

Do, T. T., Delaney, S. & Walsh, F. 16S rRNA gene based bacterial community structure of wastewater treatment plant effluents. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 366, fnz017 (2019).

Rodriguez-Mozaz, S. et al. Antibiotic residues in final effluents of European wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 140, 105733 (2020).

Yamada, Y., Yamada, M. & Nakazawa, A. A ColE1-encoded gene directs entry exclusion of the plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 177, 6064–6068 (1995).

Li, X. et al. The plasmid-borne quinolone resistance protein QnrB, a novel DnaA-binding protein, increases the bacterial mutation rate by triggering DNA replication stress. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 1529–1543 (2019).

Ishiwa, A. & Komano, T. The lipopolysaccharide of recipient cells is a specific receptor for PilV proteins, selected by shufflon DNA rearrangement, in liquid matings with donors bearing the R64 plasmid. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263, 159–164 (2000).

Brouwer, M. S. M. et al. The shufflon of IncI1 plasmids is rearranged constantly during different growth conditions. Plasmid. 102, 51–55 (2019).

Lopez J. G., Donia M. S. & Wingreen N. S. Modeling the ecology of parasitic plasmids. ISME J. 2021 Oct;15:2843-2852. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00954-6.

San Millan, A. et al. Multiresistance in Pasteurella multocida is mediated by coexistence of small plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3399–3404 (2009).

San Millan, A., Heilbron, K. & MacLean, R. C. Positive epistasis between co-infecting plasmids promotes plasmid survival in bacterial populations. ISME J. 8, 601–612 (2014).

Dionisio, F., Zilhão, R. & Gama, J. A. Interactions between plasmids and other mobile genetic elements affect their transmission and persistence. Plasmid. 102, 29–36 (2019).

Pilosof, S. Conceptualizing microbe-plasmid communities as complex adaptive systems. Trends Microbiol. 31, 672–680 (2023).

Kerkvliet, J. J. et al. Metagenomic assembly is the main bottleneck in the identification of mobile genetic elements. Peer J. 12, e16695 (2024).

Hall, J. P. J., Botelho, J., Cazares, A. & Baltrus, D. A. What makes a megaplasmid? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 377, 20200472 (2022).

Ni, S. et al. Conjugative plasmid-encoded toxin–antitoxin system PrpT/PrpA directly controls plasmid copy number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2011577118 (2021).

Saunders, ConleyE. C. & Saunders, V. A. JR. Deletion and rearrangement of plasmid DNA during transformation of Escherichia coli with linear plasmid molecules. Nucleic. Acids Res. 14, 8905–8917 (1986).

Smyth, C., Leigh, R. J., Delaney, S., Murphy, R. A. & Walsh, F. Shooting hoops: globetrotting plasmids spreading more than just antimicrobial resistance genes across One Health. Micro. Genom. 8, mgen000858 (2022).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility. CLSI Document M100S. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;., p.:M100 (2018).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

GitHub - rrwick/Filtlong: quality filtering tool for long reads. https://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong.

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M. & Holt, K. E. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome. Biol. 20, 129 (2019).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005595 (2017).

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J. & Holt, K. E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352 (2015).

Schwengers, O. et al. Platon: identification and characterization of bacterial plasmid contigs in short-read draft assemblies exploiting protein sequence-based replicon distribution scores. Micro. Genom. 6, 1–12 (2020).

Schwengers, O. et al. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genom. 7, (2021).

Seeman, T. Abricate. Github; https://github.com/tseemann/abricate.

Jia, B. et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic. Acids Res. 45, D566–D573 (2017).

Pal, C., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Rensing, C., Kristiansson, E. & Larsson, D. G. J. BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic. Acids Res. 42, D737–43 (2014).

Leigh, R. J., McKenna, C., McWade, R., Lynch, B. & Walsh, F. Comparative genomics and pangenomics of vancomycin-resistant and susceptible Enterococcus faecium from Irish hospitals. J. Med. Microbiol. 71, 001590 (2022).

Chen, L., Zheng, D., Liu, B., Yang, J. & Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis-10 years on. Nucleic. Acids Res. 44, D694–D697 (2016).

Carattoli, A. et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903 (2014).

Robertson, J. & Nash, J. H. E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 4, e000206 (2018).

Akarsu, H. et al. TASmania: A bacterial Toxin-Antitoxin Systems database. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006946 (2019).

Ondov, B. D. et al. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome. Biol. 17, 1–14 (2016).

Galata, V., Fehlmann, T., Backes, C. & Keller, A. PLSDB: a resource of complete bacterial plasmids. Nucleic. Acids Res. 47, D195–D202 (2019).

Kurtz, S. et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome. Biol. 5, R12 (2004).

Khelik, K., Lagesen, K., Sandve, G. K., Rognes, T. & Nederbragt, A. J. NucDiff: in-depth characterization and annotation of differences between two sets of DNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 12, 338 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by co-funded PhD studentship from The Kathleen Lonsdale Institute for Human Health Research, Maynooth University and the Irish Environmental Protection Agency (Grant 2019-W-PhD-14) to Prof Fiona Walsh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S. performed the experiments, data analysis and wrote the manuscript, R.L. performed data analysis, T.T.D. performed experiments and F.W. generated the research project, supervised the work, obtained the funding and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smyth, C., Leigh, R.J., Do, T.T. et al. Communities of plasmids as strategies for antimicrobial resistance gene survival in wastewater treatment plant effluent. npj Antimicrob Resist 3, 78 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-025-00151-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-025-00151-x