Abstract

This paper explores the dissemination and impact of Russian anti-war discourse on X (Twitter) following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. It examines the dynamics of this discourse within the Russian-speaking segment, identifies key actors and communities, assesses the role of bot accounts, and analyzes dominant narratives and communication strategies through framing analysis. The methodology employs a mixed-methods approach, including data collection via the Twitter API, social network analysis, bot detection, community detection, natural language processing with BERTopic, and framing analysis using the BEND model. This includes examining persuasion tactics in two distinct discourses: one involving anti-war opposition accounts and the other centered on pro-government narrative accounts. The findings provide insights into the dynamics of Russian anti-war discourse on X (Twitter), highlighting prevalent narratives and communication strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia’s political landscape was characterized as a hybrid regime, combining elements of both democracy and autocracy1. During this period, the balance between democratic and authoritarian features within the Russian political system remained in flux, with ruling elites adapting their strategies to prevailing circumstances. A significant area of contention was the media and communication sector, where the Russian government, in response to growing demand for opposition voices, maintained a mixed media system comprising both state-controlled and independent outlets2.

However, this landscape shifted following the anti-government protests of 2011–2012, as Vladimir Putin’s regime confronted what is commonly referred to as the “dictator’s dilemma.” This dilemma emerged when efforts to enforce censorship and regulate the Internet clashed with the rise of new media formats that enhanced public access to information, encouraged debate, and facilitated mobilization against the government3. The repressive environment intensified after the pro-Navalny protests in 2021, which were marked by the swift detention of opposition leader Alexei Navalny upon his return to Russia from Germany, where he had been receiving treatment following a poisoning incident the previous year. Navalny was subsequently incarcerated as a political prisoner and died in prison in 2024.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 marked a critical turning point, leading to the implementation of a series of restrictive regulations that severely curtailed freedom of speech. These measures underscored the government’s stance on media technologies, signaling a strategic shift in its approach to information control. The Kremlin’s subsequent crackdown on independent media and free expression reflects its perception of an existential threat to the regime, prompting an intensified response from the ruling elites. This pattern of repression highlights the government’s recognition of the risks associated with freedom of speech and its potential impact on political stability.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has further exposed the increasingly authoritarian nature of Vladimir Putin’s once-hybrid regime, which now exhibits zero tolerance for political dissent. This shift has led to even harsher restrictions on independent media and non-profit organizations, including the enactment of laws such as the “foreign agents law,” the “undesirable organizations law,” and a prohibition on referring to the “special military operation” as a war. Concurrently, the government has expanded its internal propaganda capabilities and imposed measures to restrict Russian citizens’ access to social media. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace noted that Russia’s political system, once described as hybrid authoritarianism, has evolved into a fully mature authoritarian regime, leading to a point of no return in its shift towards authoritarianism. This transformation was marked by the erosion of political pluralism, suppression of opposition, and the establishment of mechanisms to control public discourse4.

Given the escalating consequences of protest, including imprisonment, a growing number of individuals have turned to online platforms to anonymously express anti-war sentiments. However, due to extensive state-imposed restrictions, assessing the actual discourse on the war and public sentiment within Russia remains challenging. Social media platforms such as X (Twitter), where Russian users could voice their opinions, offer a valuable avenue for analysis. Understanding the dissemination and impact of Russian anti-war discourse on social media is crucial for gaining insights into public attitudes and the willingness to voice opposition despite government repression. This evolving landscape underscores the importance of monitoring and analyzing digital narratives and dissent in an increasingly restrictive political environment.

The purpose of this paper is to identify and analyze anti-war messages posted in Russian language on X, examining their structure and presence. Investigating the consequences of Russian anti-war discourse within the current geopolitical context is essential for understanding how this discourse develops, the groups involved, and their modes of interaction. Furthermore, this research provides insight into how the discourse evolves in response to governmental restrictions and explores the roles of social media actors, state-funded accounts, and bots in shaping narratives. A comprehensive examination of Russian anti-war discourse on X contributes to a deeper understanding of digital narrative dissemination, propaganda, public sentiment, and state control within the broader geopolitical landscape.

Many scholars agree that the Russian media system is shaped by a tension between democratic norms and market principles that were artificially implemented in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union, alongside paternalistic institutions inherited from the Soviet era5,6,7. This dynamic has been explored extensively through the lens of hybrid political systems, propaganda, and the role of digital technologies in sustaining state influence. Russia’s media environment, which initially included pluralistic and commercial elements, has gradually transitioned into a more repressive and centralized system dominated by state power. Zassoursky6 highlights that Russian media never fully shed its propaganda legacy, instead adapting to the needs of ruling elites through the rise of a media oligarchy. While commercialization initially diversified media voices, it eventually became entangled with political power, leading to renewed elite control. In this context, even as the Russian media system adopted certain market principles and experimented with private ownership and non-profit models, the extent to which journalistic autonomy and press freedom truly developed remains deeply questionable8.

As Kiriya5 contends, the Russian media system incorporated market-driven dynamics alongside government control. This dual structure generates tensions between liberal values and the informal rules imposed by ruling elites, including oligarchs and the siloviki (derived from the Russian word “silovye struktury”, meaning “force structures”), a group comprising members of the country’s security services, military, law enforcement, and intelligence agencies. The siloviki group holds substantial influence over Russian politics and governance, particularly during Vladimir Putin’s presidency, given his own background in the KGB, the Soviet-era intelligence agency. This group emphasizes state control, centralization of power, and national security, playing a critical role in shaping policy decisions and bolstering regime stability. Their influence extends beyond governmental roles, as they also exert considerable control over key industries, including energy and media, thereby consolidating power across various sectors of the economy and society.

Today, the Russian media system is characterized by significant “intrusion of the state in social life, which forms particular practices of commercial and state-dependent agents in the field of pressure on the media by means of control over content and news“5. State control formulates a particular social discourse of ‘us,’ those who support governmental policies, versus ‘them,’ liberal opponents who are presented by state media as either ‘foreign agents’ or enemies from the West. Such binary discourse has led to the segmentation and isolation of particular social groups, creating obstacles to media pluralism9. Most accessible news organizations are owned by the state, oligarchs, or other elites who are inclined to represent the official point of view5,10.

At the same time, this dynamic has generated a parallel public sphere in Russia where alternative opinions find their audience5. It includes independent online media and provides its audience with critical coverage despite political and economic pressures. However, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Kremlin initiated a series of repressive measures against liberal media and reporters, leading to the introduction of war censorship laws and forcing journalists to leave the country in search of refuge abroad. Today, media institutions that still operate in Russia must adhere to the rules established by the state, conforming to the official public discourse promoted by the Kremlin to maintain social stability and ensure the reproduction of the power elite. A large portion of independent outlets have been absorbed into the official system and are owned by state-related actors. However, even Russia’s prominent liberal independent media such as Echo Moskvy (owned by the Russian state-controlled energy corporation Gazprom) and Novaya Gazeta (owned by businessman Alexander Lebedev, a former KGB agent) ceased their activities in Russia following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

As the introduction of democratic norms into the Russian media system remained largely superficial9, state pressure on the free press has steadily increased, resulting in a highly controlled media and information environment. This control is characterized by censorship, the monopolization of key media outlets by state-affiliated entities, and the systematic restriction of independent journalism. Consequently, the media serves as a tool for promoting state narratives while limiting dissenting voices and alternative perspectives5,9.

Digital tools are also subject to government control, as seen in the case of the Russian search engine Yandex. Often described as the “Russian Google,” Yandex has gradually evolved from a private technology company into a tool of the Russian government’s information control strategy. The process began with institutional capture: in 2009, Yandex sold a “golden share” to state-owned Sberbank after political negotiations, giving the Kremlin leverage over the platform’s governance11. Subsequent regulatory frameworks made news aggregators legally responsible for their content, pressuring Yandex to privilege state-approved outlets while excluding unregistered or oppositional media12. Empirical studies demonstrate the effects of this political appropriation. Makhortykh et al.13 show how Yandex complied with a Russian court order during the 2021 parliamentary elections by suppressing results related to Alexei Navalny’s Smart Voting initiative and, in some cases, amplifying conspiracy narratives aligned with Kremlin discourse. Similarly, Kravets14 documents the systematic bias of Yandex’s Top-5 news in Belarus: the majority of headlines originated from Kremlin-linked outlets, opposition voices were progressively excluded, especially after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and coverage disproportionately featured Russian actors framed positively. Through a combination of state capture, regulatory pressure, and algorithmic manipulation, Yandex has become a central instrument of the Kremlin’s propaganda ecosystem at home and abroad.

The legal environment in Russia poses significant risks to anti-war expression. Laws enacted in 2022, such as Criminal Code Article 207.3 (“spreading false information” about the armed forces) and Administrative Code Article 20.3.3 (“discrediting the army”) have been used extensively to penalize anti-war voices, with over 10,000 administrative and hundreds of criminal cases recorded15. With recent censorship laws, not only media and journalists but also ordinary citizens face punishment by the state for expressing opinions that contradict the official Kremlin stance. Social media, once a platform for relatively free political expression and activism, has increasingly come under state control and surveillance. While social media platforms and international networks such as YouTube and X are still used to share information, mobilize, and express dissent, they operate within a highly restrictive and contentious environment.

VKontakte, Russia’s largest social media platform, has long been criticized for its proximity to the Kremlin. After its founder Pavel Durov was ousted in 2014, the platform came under the control of government-aligned companies, making it a tool for state surveillance and propaganda. Similarly, Telegram, despite its reputation for encrypted communication and its role in facilitating political mobilization and protests, has a more complicated relationship with the Russian government. While Telegram initially resisted government censorship and bans, it has more recently faced accusations of cooperating with authorities, raising concerns about its reliability as a safe platform for dissent. Investigations suggest potential cooperation with authorities and vulnerabilities to surveillance, raising risks for opposition content creators16.

X, despite being prohibited in Russia since the start of the war in Ukraine, remained a vital tool for political expression. It has played a key role in amplifying Russian anti-war sentiments, with users sharing opposition content, firsthand accounts, and information about the consequences of the war. At the same time, the usage of X is skewed toward younger, urban, and politically active users. Although access to X and other banned platforms is restricted in Russia, many citizens circumvent these limitations through virtual private networks (VPNs). VPNs have enabled anti-government voices to persist online and allowed the flow of uncensored information in and out of the country despite increasing censorship. Russia’s leading independent, non-governmental polling and sociological research organization Levada Center report indicates that by 2025 around 36% reported using VPNs regularly or occasionally17.

However, while using a VPN in itself has not been known to lead directly to prosecution, recent legislation imposes fines for accessing content labeled ‘extremist’ via VPN and much higher penalties for promoting or operating VPN services18,19. Russia’s new VPN regulation does not impose a full ban but significantly raises risks for users by introducing fines for advertising VPNs, expanding criminal liability, and adding VPN use as an aggravating circumstance in prosecutions. While authorities frame the law as targeting access to “extremist materials,” experts warn that it may lead to automated traffic monitoring, device checks by police, and wider surveillance under existing data retention laws. These measures are expected to foster self-censorship, with many citizens likely to avoid downloading or using VPNs out of fear of penalties, even for legal purposes. Ultimately, the regulation contributes to a more restrictive digital environment, where uncertainty around enforcement and the risk of criminalization push individuals and businesses toward compliance with state narratives and away from tools that enable access to independent information. The increasing legal restrictions and surveillance capabilities significantly heighten the risk associated with accessing dissenting content18,19. Despite these dangers, social media remains an important avenue for Russian people to access independent information, organize politically, and challenge state narratives. Yet, the government’s increasing control over domestic platforms and its restrictive regulations on international platforms have significantly narrowed the space for free and open political discourse.

Propaganda and disinformation have become central instruments for the Kremlin in advancing its political goals and strategic narratives. A broader body of scholarship situates Russian media strategies within global debates on propaganda and disinformation, highlighting the adaptability of authoritarian regimes in exploiting new technologies to disseminate narratives, fragment public discourse, and generate informational uncertainty20,21. Pomerantsev20 characterizes Russia’s postmodern propaganda style as one that destabilizes truth by flooding the public sphere with contradictory messages while simultaneously promoting regime interests. This perspective aligns with Darczewska’s22 analysis of Russian information warfare, which underscores how disinformation and censorship operate as integral components of hybrid conflict. In this environment, Russia’s digital propaganda, supported by troll farms and automated bot networks, plays a central role in shaping the discourse around the war in Ukraine and beyond.

The rise of social media and the computational power of the Internet have significantly amplified the reach and influence of these efforts, facilitating the dissemination of political messaging aimed at shaping and controlling social discourse. Prior research has documented disinformation operations orchestrated by Kremlin-affiliated actors, such as the Internet Research Agency (IRA), which have sought to influence political and social discourse in various countries. The IRA has been identified as a primary source of malicious online activity, employing divisive messaging on social media to manipulate public opinion, promote strategic narratives, and foster destabilization, polarization, information disorder, and societal distrust. Notable instances include interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the 2020 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, and other socio-political events23,24,25. Scholars have identified propaganda and disinformation narratives associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine26,27. Additionally, journalists identified “Operation Doppelgänger,” which took place in 2022, exposing it as a Russian disinformation campaign that created fake websites mimicking legitimate news outlets to spread pro-Russian narratives and undermine support for Ukraine28,29.

Russia’s contemporary propaganda strategy relies heavily on obfuscation and psychological manipulation, often inducing audiences to act in ways that align with the Kremlin’s interests without their conscious awareness. This strategy represents a continuation of Soviet-era Cold War disinformation tactics30. The Russian government employs propaganda not only to incite opposition within foreign societies but also to mobilize domestic support through state-controlled media channels and digital platforms. The selection of propaganda dissemination channels is largely determined by the accessibility and receptiveness of specific target audiences. A significant focus of Russian propaganda efforts has been to deepen divisions between Russia and the international community by cultivating a siege mentality and portraying Russia as a besieged nation encircled by hostile adversaries27.

For Russian leadership, propaganda serves as a mechanism to justify aggressive foreign policies under the pretext of national defense while simultaneously suppressing domestic opposition by branding dissenters as traitors. The dissemination of disinformation narratives concerning Ukraine predates the 2022 invasion and can be traced back to the 2014 annexation of Crimea. During that period, researchers identified several recurring themes in Russian propaganda against Ukraine, including efforts to undermine Western-backed reforms, isolate Ukraine from its allies, and advocate for closer ties with Russia31. A key component of these narratives was the claim that Ukraine was secretly controlled by “Western curators” who imposed excessive costs on cooperation. Among these recurring disinformation themes was the allegation that the United States was operating secret biological laboratories in Ukraine, an accusation with historical precedents dating back to Soviet Cold War disinformation campaigns31,32,33.

The evolution of digital propaganda and disinformation strategies has been shaped by technological advancements and the shifting media landscape34. Consequently, it is imperative to systematically monitor and analyze media discourse, particularly on social media platforms, which are frequently exploited for manipulative purposes. Recent trends, including the proliferation of automated bot activities and other coordinated influence operations25,35, underscore the necessity of identifying these activities and conducting comprehensive analyses of the narratives and communities involved in the dissemination of disinformation. Case studies in this domain provide critical insights into the techniques employed to propagate harmful disinformation and offer valuable lessons for developing countermeasures.

Recent tactics for influencing public opinion include the convergence of multiple social media platforms, the deployment of autonomous bots, and the utilization of big data36. These technological tools enable targeted influence operations with unprecedented precision and speed, granting actors significant persuasive power while maintaining the fundamental characteristics of propaganda. As Hyzen36 observes, propaganda seeks to persuade and influence through ideological symbols, eliciting specific responses, reinforcing collective identities, and fostering loyalty. Ultimately, propaganda constitutes a form of persuasive communication designed to advance ideological objectives, shape public perceptions, and institutionalize the allegiance of target audiences. Propaganda is often constructed through framing of the narratives, where specific aspects of reality are highlighted, exaggerated, or distorted to align with particular ideological, political, or social agendas. By selectively presenting information, omitting key details, or using emotionally charged language, propagandists craft compelling stories that shape public perception and influence collective beliefs.

Framing is a fundamental process in communication that influences how individuals perceive events, issues, and actors. It involves selecting certain aspects of reality and making them more salient while omitting or downplaying others, thereby shaping interpretations and guiding audiences toward certain perspectives37,38. While framing is a common mechanism in all forms of communication, it plays a particularly significant role in propaganda, where it is strategically employed to construct narratives that align with ideological, political, or strategic objectives.

Although frequently associated with propaganda, framing is a broader communicative process utilized in various domains, including journalism, political discourse, and advertising. By structuring information in a way that highlights certain aspects while minimizing others, communicators can influence public opinion and decision-making processes. Within the context of information dissemination, framing serves as a strategic tool to reinforce ideologies, evoke specific emotions, and legitimize particular courses of action.

Framing occurs at multiple levels, including within media content, social structures, and digital environments. It is embedded in textual and visual representations through language choices, imagery, and selective information. Additionally, it is reinforced by social institutions such as political organizations, educational systems, and online communities that propagate dominant narratives while marginalizing dissenting perspectives39. In contemporary digital environments, social media platforms play a critical role in disseminating framed messages, as algorithmic filtering tailors content to specific audiences, reinforcing ideological silos and creating echo chambers.

The framing process has traditionally been conceptualized as a psychological phenomenon, involving complex cognitive mechanisms that shape how individuals select, process, and interpret information. Entman40 defined framing as the act of “select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text”. However, some scholars argue that framing is not solely a cognitive process but also an organizational practice influenced by institutional communication routines and socio-political contexts39.

Framing not only shapes public opinion but also plays a role in historical memory construction and political mobilization. Propaganda often simplifies complex realities into dichotomous narratives, such as ‘good’ versus ‘evil’, ‘order’ versus ‘chaos’, or ‘us’ versus ‘them,’ thereby reinforcing polarized worldviews. This reductionist approach is particularly effective in moments of crisis when individuals seek clarity and certainty. Understanding framing as a communicative process is essential for understanding the discourse and it is crucial to analyze how messages are structured, which purposes they serve, and how they influence public perceptions. Recognizing framing techniques enables individuals to critically assess the messages, question dominant narratives, and resist manipulative messaging designed to shape their attitudes and actions.

This study employed BERTopic analysis for topic modeling and BEND framework of information maneuvers for analyzing framing in Russian anti-war discourse on X. Together, these methods combine quantitative scalability with qualitative interpretive depth. BERTopic identifies what is being discussed, while BEND analysis reveals how it is framed and strategically deployed, enabling a comprehensive understanding of information framing processes in the discourse. Using BERTopic, recurring linguistic patterns and topic clusters can reveal emphasis frames embedded in large-scale text data, while BEND maneuver analysis can identify strategic uses of these frames, including emotional amplification, polarization, or legitimization. This combined approach allows researchers to capture not only the content and structure of discourse but also the strategic communicative techniques employed across multiple modes of online messaging, providing a comprehensive understanding of framing in the discourse.

This study aims to identify and examine anti-war messages in the Russian language on X, with a focus on actors, communities, frames, and information maneuvers. The following research questions guide the analysis:

RQ1: How has Russian anti-war discourse on X evolved over time?

RQ2: Who are the most influential actors and communities within this discourse?

RQ3: What are the predominant narratives and frames (information maneuvers) advanced by these actors and communities?

Results

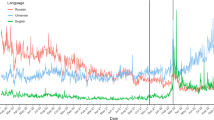

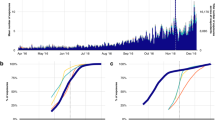

As a result of data collection, our dataset contains 657,548 tweets with 497,431 retweets and 163,205 users (see Fig. 1 for details on tweets over time and bot/not bot users).

Figure 1 illustrates a noticeable decline in the number of tweets starting in March-April 2022, with two significant spikes observed around October 2022. This trend likely reflects several key factors. The first major factor is the blocking of X in Russia in March 2022, which significantly hindered access to the platform without the use of a VPN. Such a policy change likely contributed to a decrease in user activity, as accessing X became more challenging.

In addition to the platform’s accessibility issues, these patterns could also be attributed to the Russian government’s implementation of restrictive censorship laws. Specifically, the government introduced laws that prohibit referring to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a “war,” instead mandating the use of terms that downplay the conflict. This legal framework also criminalizes discussions deemed harmful to the state, such as labeling actions by the Russian military as “discrediting.” Under these laws, individuals found guilty of disseminating “false” or “unreliable” information about the Russian armed forces could face severe penalties, including up to 15 years of imprisonment. These strict legal consequences likely contributed to self-censorship among Russian users, dissuading them from tweeting about the invasion due to the fear of legal repercussions.

The spikes observed in October 2022 can be linked to the Russian government’s announcement of a partial mobilization, which called up a significant number of citizens for military service. This major political event likely prompted a surge in discourse about the invasion, leading to increased tweeting activity. It is worth noting that this spike could also reflect heightened public attention to issues related to the mobilization and its implications for the ongoing conflict.

Finally, the volume of tweets from bots mirrors the broader patterns of user-generated content. This suggests that automated accounts are not only mirroring the general trends in tweet volume but are also engaging with the same topics. The alignment of bot activity with user behavior indicates that bots may be replicating or amplifying the dominant discourse during key moments, such as the mobilization announcement. The high number of retweets further illustrates this trend.

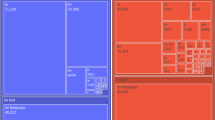

Figure 2 illustrates the dominant role of bots in this particular discussion. The number of accounts identified as bots exceeds that of non-bot accounts, indicating that automated systems are heavily influencing the discourse. Furthermore, the volume of messages posted by bots is substantially higher than that posted by non-bot users, further highlighting their significant presence in the conversation.

X influencers

In our dataset, several accounts and individuals emerged as key super spreaders, including members of the Russian opposition, notably those associated with the Anti-Corruption Foundation, an organization founded by opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Additionally, the list encompassed European politicians, human rights advocacy organizations, news and opinion outlets, independent newsrooms, and anti-war activist groups.

However, an anomaly was observed among the leading super spreader accounts, particularly those referencing the “No war” slogan. These accounts were not only aligned with anti-war, pro-Ukraine, pro-opposition, and pro-Navalny discourses but also included more ideologically divergent accounts. ZavtraRu, a far-right Russian newspaper that positions itself as a conservative, ultranationalist, and anti-capitalist outlet, was identified as a prominent super spreader. Similarly, @DenTvRu, associated with Den TV (a far-right television station with an online presence) also emerged as a key contributor to the spread of content. Den TV is known for propagating Russian state narratives, conspiracy theories, and ultranationalist rhetoric.

Upon further analysis of the hashtags and tweets disseminated by various accounts, significant differences in narrative framing were evident between the anti-war channels and the far-right outlets Zavtra and Den TV. Anti-war accounts predominantly employed the #nowar hashtag, often in conjunction with other anti-war hashtags, such as #StopPutin and #NoWarWithUkraine. In contrast, Zavtra and Den TV used #nowar hashtag alongside pro-government propaganda hashtags, including #Z, #ДаПобеде (“Yes to Victory”), and #СлаваРоссии (“Glory to Russia”). These combinations reflect a strategic effort to co-opt the anti-war sentiment to further advance pro-government and ultranationalist narratives.

Further examination revealed significant instances of hashtag hijacking within both pro-war and anti-war groups. Hashtag hijacking refers to a form of digital manipulation in which a hashtag is co-opted for purposes other than its original intent, often by associating unwanted or counter-narrative content with a popular hashtag, thereby amplifying its reach to a broader audience41. We visualized the network of certain hashtags used in the dataset and identified multiple instances where pro-government hashtags were employed alongside anti-war hashtags, a tactic further illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 illustrates a network of pro-war hashtags that are used alongside anti-war hashtags such as #NoWar and #StopWar. Among these, hashtags like #StopUkrainianNazism, #StopZelensky, and #WarInDonbass8Years are prominent. These hashtags are central to a broader Russian state propaganda campaign designed to justify Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, shift blame, and maintain both domestic and international support for its actions. Kremlin has consistently framed its 2022 invasion as a necessary intervention rather than an act of aggression. By deploying these hashtags often in conjunction with anti-war hashtags, the Kremlin could seek to reinforce the narrative that the conflict originated in 2014 with alleged Ukrainian aggression against civilians in Eastern Ukraine, particularly in predominantly Russian-speaking regions such as Donetsk and Luhansk.

These hashtags exemplify how the pro-Kremlin information spreaders attempt to deflect responsibility from Russia while portraying Ukraine as the aggressor and Russia as a liberator defending ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking Ukrainians from attacks by Zelensky government. Within Russia, these hashtags reinforce the state’s official narrative that Ukraine is a Nazi state perpetrating genocide against Russian speakers. This rhetoric has been instrumental in legitimizing the invasion under the pretexts of “denazification” and “civilian protection.” Additionally, these hashtags serve to suppress anti-war sentiment within Russia by framing military actions as defensive rather than offensive.

A qualitative analysis of these hashtags reveals that both pro-Kremlin and anti-war actors strategically co-opt hashtags from the opposing side to advance their own messaging. Figures 4 and 5 provide examples of this cross-utilization and the competing narratives propagated through these digital campaigns.

Leiden clustering for community detection

After applying Leiden clustering to the entire communication network, the largest ten communities were analyzed. The top influencers in the four largest groups exhibited genuine anti-war sentiments, comprising opposition leaders and independent media such as Alexey Navalny, Ilya Yashin, MediaZona, and OVD-Info, among others. However, groups #5 and #6 were predominantly composed of Russian politicians, state-funded media, and influencers, including MFA Russia, RIA Novosti, and the Russian State Duma’s official account. Group #7 featured the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and other opposition activists as key influencers, while group #8 consisted of pro-Ukraine users and Ukrainian politicians. Group #9 was primarily composed of Russian anti-war singers and performers, whereas group #10 also had anti-war accounts as the main influencers. This distribution highlights the existence of multiple and diverse, sometimes opposing, groups within the conversation, all utilizing the same hashtag, such as #NoWar.

A separate Leiden clustering was conducted for the coordinated communication network. While Russian state propaganda and government-affiliated accounts were present in groups #5 and #6 in the general communication network, they were specifically identified in the two largest clusters of the coordinated communication network. In contrast, the third and fourth largest groups consisted of anti-war and pro-Ukraine accounts. Groups #5 and #6 also contained accounts with anti-Putin and pro-Navalny narratives that posted anti-war messages. Groups #7 to #9 predominantly disseminated anti-war and pro-Ukraine messages, while cluster #10 contained numerous influential accounts promoting Russian propaganda. This analysis indicates that although Russian pro-government discourse is not dominant in the general communication network, it is spread in larger clusters in the coordinated communication network.

As a result of the Leiden clustering analysis, two representative communities were selected: one representing discourse led by influential pro-opposition and anti-war accounts, and another representing pro-war discourse. In terms of composition, both groups contained users identified as bots by Bot-Hunter detection tool. Within the opposition and anti-war community (21,436 users), 56% of the accounts were classified as bots, contributing 75% of the total messages. In the pro-government community (7558 users), 60% of the accounts were identified as bots, responsible for 72% of the tweets. This analysis demonstrates that both groups employed bots to disseminate their messages and amplify their narratives. We compare these two communities, their thematic content, and framing through the application of the analysis of BEND maneuvers.

Topic modeling with BERTopic

To capture the thematic structure of Russian-language Twitter discourse surrounding the war in Ukraine, we applied BERTopic to the full dataset of processed tweets, as well as to two distinct communities identified through network analysis: a pro-government cluster (21,996 tweets) and a pro-opposition cluster (119,290 tweets). The models produced interpretable and coherent topic structures, with coherence scores of 0.57 for the full dataset, 0.85 for the pro-government community, and 0.74 for the pro-opposition community.

Across the entire dataset, topic modeling revealed a broad spectrum of discourse centered on anti-war sentiment, civic activism, and criticism of Russian military actions. Prominent topics included references to “Russia Ukraine war, Putin, anti-war sentiment,” “Peace slogans and anti-war activism,” and “Protests, petitions, and activism,” indicating a sustained digital mobilization against the war. Additional themes such as “Police arrests and political repression,” “Censorship and fear,” and “TV broadcasts and propaganda” point to a discursive field shaped by both resistance and control. Symbolic forms of dissent, like “Ukrainian flag symbols,” “Cats as anti-war symbols,” and “Graffiti protests,” emerged alongside more conventional activism, suggesting that users adapted to repression through highly creative means.

The prominence of topics related to historical parallels (e.g., “WWII and Nazi Germany”), children and education, and digital spaces (e.g., “Twitter activism”) reflects how the anti-war discourse integrated moral, historical, and informational dimensions (see Fig. 6 for more details).

In the pro-opposition community, topic modeling revealed a complex landscape of resistance shaped by both visible and symbolic acts of protest. High-frequency topics such as “Anti-war protests and activism,” “On-air protest against propaganda,” and “Street protests and detentions” captured direct challenges to state narratives. Region-specific clusters, including “Protests in Dagestan” and “Yakut traditional dances,” illustrated localized forms of dissent often absent from national media.

Equally significant were topics documenting state repression, including “Fines and trials,” “Censorship and fear,” and “Graffiti protests and detentions.” These narratives foregrounded the personal risks associated with protest, particularly for children, educators, and journalists. Despite this, users continued to share stories of resistance through symbolic channels, cats as anti-war icons, snow-writing protests, or anonymous graffiti, highlighting a resilient civic culture under authoritarian constraints.

Other topics played a prominent role, and the discourse often emphasized solidarity with Ukraine and broader democratic values. Online platforms like Twitter functioned as alternative public spheres, enabling information exchange, mobilization, and counter-narratives. While these spaces were also targets of censorship, they provided crucial symbolic and practical infrastructure for sustained dissent. The coherence score (0.74) indicates consolidated and consistent framing across topics (see Fig. 7 for more details).

Within the pro-government community, the discourse was dominated by themes that sought to discredit, mock, or delegitimize anti-war activism. The most coherent topics focused on accusations of hypocrisy, performativity, and foreign influence, such as “Criticism of selective anti-war stance,” “Accusations of paid anti-war pro-Ukraine statements,” and “Mockery of anti-war celebrities.” Users often contrasted the anti-war movement’s silence on the Donbas conflict or on Israeli actions in Gaza with its vocal condemnation of Russia, framing this as evidence of double standards and Western manipulation.

Several topics directly attacked the moral credibility of cultural figures and celebrities, portraying them as opportunistic, financially motivated, or traitorous. Other clusters emphasized patriotism and justified the war as a defense of Russian sovereignty, while portraying pacifist or humanitarian rhetoric as naïve or dangerous. These narratives collectively constructed anti-war activism as foreign-aligned, morally suspect, and disconnected from Russian realities, thereby reinforcing a pro-state, pro-military identity. The coherence score (0.85) indicates that this cluster is ideologically consolidated, with highly consistent framing across topics (see Fig. 8 for more details).

Taken together, the topic modeling results reveal a highly polarized and contested discursive field. The full dataset reflects a heterogeneous landscape of opposition, moral critique, and symbolic protest, while the pro-government cluster constructs a counter-narrative that delegitimizes dissent through accusations of hypocrisy and betrayal. The opposition community, in contrast, documents both the diversity of anti-war expression and the pervasiveness of state repression. These parallel discourses illuminate how the Russian-language Twitter sphere has become a site of struggle over truth, legitimacy, and national identity. Protest is alternately framed as civic courage or as foreign-funded treachery; repression is either a necessary defense or a violation of human rights. These dynamics underscore the complex ways digital publics negotiate power, identity, and resistance in authoritarian contexts during wartime.

Analysis of BEND maneuvers in the discourse

As a result of the framing analysis through application of BEND maneuver framework, we found that the pro-government community’s discourse was predominantly framed using the Back, Dismiss, Distract, and Engage maneuvers. Specifically, tweets from this discourse largely supported the war in Ukraine while criticizing anti-war arguments, undermined anti-war narratives by emphasizing the defense of the Russian-speaking Donbas region, and propagated anti-Zelenskyy messages, labeling the official Ukrainian government as a Nazi regime and justifying the war as a fight against Nazis. Additionally, the Distract maneuver was employed through criticisms of the West’s involvement in the war in Gaza, while the Engage maneuver was used to draw attention to pro-war messages. In contrast, the discourse of opposition actors was primarily framed with the Build, Dismay, Enhance, and Negate maneuvers. These tweets aimed to build an anti-war community through the use of anti-war hashtags and news, criticized the government, and shared news related to the war. Their narratives supported Ukraine and anti-war protests, while also expressing anti-war and anti-Putin sentiments (see Fig. 9).

When comparing the likelihood of maneuver use between the discourse of two communities, we observe that the discourse with the pro-government actors is more likely to employ positive community maneuvers such as Bridge and Build, as well as the negative narrative maneuver Distract and the positive narrative maneuver Engage. In contrast, the discourse with the opposition community is more likely to use positive narrative maneuvers like Enhance and Explain, along with the negative community maneuver Neglect (see Fig. 10).

After comparing the use of BEND maneuvers by bots and non-bots in each community discourse, we found that bots and non-bots exhibit similar patterns in the pro-government discourse, with both focusing primarily on positive narrative maneuvers, including Enhance, Neglect, Engage, and Explain (see Fig. 11). In contrast, the opposition discourse shows notable differences. Bots in the opposition group use significantly more positive narrative maneuvers, such as Enhance and Explain, while non-bot accounts are more likely to employ the Back and Engage maneuvers, which are positive community and narrative maneuvers (see Fig. 12).

A direct comparison of bots from the opposition and pro-government discourses reveals that bots in the pro-government discourse are more likely to use the Back, Boost, Bridge, Build, Distort, Distract, Engage, and Narrow maneuvers. In contrast, bots in the opposition discourse are more likely to use the Enhance, Explain, and Neglect maneuvers (see Fig. 13). For additional examples of tweets from both groups, refer to Fig. 14.

Discussion

Following our analysis of Russian anti-war discourse on X, several significant insights have emerged. We observed a notable decline in tweet activity overtime, likely due to X blockage in Russia and restrictive laws enacted by the Russian government regarding the portrayal of the war in Ukraine. Additionally, our investigation revealed a substantial presence of bots in the discussion, outnumbering non-bot users in both quantity and volume of messages posted. Further exploration identified various accounts and individuals as top super spreaders, ranging from those associated with the Russian opposition to pro-government actors.

Analysis of communication networks using Leiden clustering unveiled distinct communities, including an opposition-led anti-war cluster and a pro-government cluster, both containing substantial bot activity. BERTopic analysis reveals the content dimensions of these communities, showing how topics are structured around opposing frames: opposition actors frame the war in terms of civic courage, anti-war mobilization, and state repression, while pro-government actors frame the conflict as defensive, patriotic, and morally justified, often delegitimizing anti-war voices as foreign-influenced or hypocritical. These topics illustrate the cognitive structures through which audiences process and interpret information, highlighting the interaction between narrative content and framing mechanisms in shaping public perception.

BEND maneuver analysis complements this by capturing the strategic deployment of these frames in communication. Pro-government actors predominantly employ Back, Dismiss, Distract, and Engage maneuvers to reinforce pro-war frames, discredit dissent, and amplify state-aligned narratives. Opposition actors primarily use Build, Dismay, Enhance, and Negate maneuvers to construct anti-war frames, foster solidarity, and counter state propaganda. Bots largely replicate these patterns, intensifying the salience of particular frames within each community.

The pro-Kremlin narratives identified in the discourse typically frame the war as a defensive operation against alleged Ukrainian aggression to justify Russian military actions, often portraying the conflict as an act of self-defense. For instance, Kremlin-aligned narratives claim that Ukraine committed genocide against Russian speakers prior to 2022, employing hashtags such as #StopUkrainianAggression to reinforce these claims. Pro-Kremlin accounts and bots flood social media platforms with identical pro-Kremlin messages to manipulate trending topics and amplify propaganda narratives. Additionally, these accounts engage in coordinated “hashtag hijacking,” inserting false narratives into broader discussions. Such efforts are a part of information strategy that integrates historical revisionism, victim-blaming, and manipulative rhetoric to justify Russia’s war and undermine global support for Ukraine. This strategy is also deployed against Russian opposition discourse, where pro-Kremlin actors seek to discredit anti-war voices, exacerbate societal divisions, and diminish support for those who have fled Russia due to their opposition to the war.

Taken together, these findings underscore how framing operates in multi-way processes in Russian-language Twitter discourse. This approach illustrates the intricate interplay between narrative, strategy, and audience perception, highlighting how both pro-government and opposition actors actively shape interpretations of the war. The study demonstrates that online discourse under authoritarian conditions is not only polarized but also carefully framed and strategically disseminated, offering critical insights into the mechanics of digital propaganda and counter-propaganda in contemporary Russia.

This study has several limitations related both to computational topic modeling and to the nature of Russian Twitter discourse. While BERTopic provides advantages over traditional methods in detecting themes and frames within short texts, topic modeling remains an interpretive exercise. The process of clustering and reducing topics involves a series of technical choices that shape the resulting narratives. Clustering outcomes in BERTopic are sensitive to model parameter choices, meaning that alternative configurations could yield slightly different topic structures. The model is better at detecting dominant narratives but may underrepresent marginal or less frequent voices in the data. Model can also struggle with figurative speech, sarcasm, or rapidly evolving slang, which are common features of online political debate.

Bot detection analysis could also present a limitation of this study for detecting automated accounts. As a computational tool, its classifications may include false positives or negatives, particularly in the context of nuanced or event-specific discourse. Although Bot-hunter has been validated in prior studies, we did not conduct manual validation on our dataset. Consequently, the proportion of bots reported should be interpreted as an estimate rather than an exact measure of automated activity.

Analyses of Russian Twitter discourse face several broader limitations. Twitter is less representative of the Russian population at large, as its user base skews toward younger, urban, and politically active groups, while many Russians also use platforms such as VKontakte or Telegram. This makes it likely that the Twitter audience examined in this study reflects a digitally literate, politically engaged population. Another limitation of this study is that by focusing exclusively on tweets containing anti-war hashtag, the dataset may exclude other Russian oppositional voices who do not use this hashtag. Also, the Russian government’s restrictions on social media and increasing platform censorship limit participation and may bias the observable discourse. Since our dataset was collected specifically using anti-war–related terms, any presence of pro-Kremlin propaganda within the data is limited to this particular context, making it challenging to generalize findings to broader propaganda strategies. Although we identified coordinated communication patterns, bot activity, and strategic narrative framing, it is difficult to definitively classify these behaviors as part of a disinformation campaign, as determining intent in online discourse remains inherently challenging.

Bot activity, coordinated campaigns, and inauthentic amplification blur the boundary between genuine public opinion and manufactured propaganda, complicating interpretation. Finally, geopolitical and temporal dynamics, such as shifts after major political events or platform bans, mean that Twitter data may capture only a partial and volatile picture of the Russian information environment.

Kremlin propaganda operates through a multi-layered disinformation ecosystem that disseminates narratives via hashtags and online communities across various platforms and audiences. Analyzing how these narratives spread, the tactics employed, and their intersections with broader disinformation strategies is crucial for understanding their impact. Given that these narratives are often amplified through coordinated efforts and interconnected communities, it is essential to identify both the strategies used within similar communities and the methods employed to propagate these narratives beyond their initial audience. Furthermore, analyzing influencers who bridge multiple communities is critical, as they play a key role in the dissemination of disinformation.

Future studies could also expand the analysis of discourse by examining a broader range of euphemisms and ideological terms beyond anti-war narratives such as “special military operation” (SVO), “denazification,” “russky mir,” and similar formulations which are frequently deployed to legitimize the war effort and suppress dissenting voices. Future research could also expand the analysis to include multiple keywords, alternative hashtags, or network-based identification related to war discourse. Their systematic study could provide deeper insights into the dynamics of state-sponsored framing and propaganda.

Future research could also further examine the role of bots, artificial intelligence (AI), and automation in amplifying disinformation. Additionally, further exploration is needed to develop counter-disinformation strategies, particularly those that involve collaboration between governments, social media platforms, and community organizations to build societal resilience against harmful information campaigns. The application of AI tools for analyzing posting patterns, network clusters, and linguistic inconsistencies is also essential for identifying and mitigating disinformation campaigns. Given the constantly evolving nature of disinformation tactics, a comprehensive approach combining governmental and industry actions, media literacy initiatives, community engagement, and AI-driven detection methods is necessary to help democratic societies disrupt and neutralize malicious information.

Methods

Data collection and analysis

The study’s data collection and methodologies adhere to procedures in social cybersecurity research42,43,44. To address our research inquiries, we collected a dataset of tweets using the Python package twarc, conducting an archive search via the Twitter API (version 2) with academic access. Tweets on anti-war discourse from February 2022 to November 2022 were collected based on the list of relevant keywords. The keyword search included the phrase “нет войне” and the hashtag #нетвойне (“no to war”) to identify relevant tweets. The raw X data were converted into a meta-network consisting of user, tweet, hashtags, and URL communication networks using ORA software for network analysis45. A mixed-method approach was employed, incorporating quantitative and computational methods for data collection and analysis, alongside qualitative investigations of tweets, users, and narratives. For details on the methods used in this study, see Fig. 15.

To detect bot activities, we utilized Bot-Hunter, a tiered supervised machine learning tool for bot detection and characterization46. The methodology also included network analysis of X data to identify key actors and influencers, including super spreaders and super friends, as well as Leiden clustering to detect communities within the network. We then examined communication and persuasion maneuvers using the BEND framework and employed BERTopic for topic modeling in two prominent communities: the anti-war opposition discourse and pro-government propaganda discourse. Additionally, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the most influential users and communities in the network, their corresponding tweets, and the narratives that emerged within each community.

For influencer analysis, we used ORA software to compute network metrics and generate lists of the most influential accounts. Influencers are defined as accounts that significantly shape discourse within the social network due to their strategic network position. Their narratives have the potential to influence public opinion and drive engagement. Identifying these key influencers is crucial for understanding the broader implications of information operations. ORA software identified X influencers based on network metrics computed from communication networks. Specifically, we categorized influencers into super spreaders (determined by out-degree centrality, PageRank centrality, and k-core) and super friends (identified using total degree centrality and k-core). Super spreaders are users who consistently generate widely circulated content, while super friends engage in sustained two-way interactions, contributing to the formation of dense and resilient communication networks.

To detect communities participating in X conversations, we applied the Leiden clustering algorithm, which partitions networks and moves nodes to ensure well-connected communities. The Leiden algorithm is more efficient and produces better partitions than alternatives such as Louvain clustering47. After identifying the communities, qualitative methods were employed to compare content and user characteristics across groups. We conducted influencer analysis within the largest Leiden communities, identifying key attitudes expressed by prominent influencers in each group. Given the large number of communities and actors, our focus remained on the most influential users (with highest in-degree centrality), whose content has the widest reach within each community. Additionally, we applied Leiden clustering to detect coordinated communication, defined as actions taken by users in a synchronized manner over the same period. Coordination was operationalized as the use of the same user mentions, hashtags, and URLs within a five-minute interval48. Finally, Leiden clustering helped identify two primary communities for deeper investigation and comparison: the anti-war opposition community and a community of discourse organized with highly influential pro-government pro-war accounts.

BERTopic analysis

To identify major topics within the anti-war opposition and pro-government communities, we employ BERTopic modeling, which has demonstrated superior performance over traditional topic modeling approaches such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), particularly for short-text documents49. The BERTopic pipeline consists of generating vector representations of text using a BERT-based embedding model, followed by dimensionality reduction and clustering to group similar documents50. For this study, we used the paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2 model, a powerful multilingual transformer trained on more than 50 languages, including Russian. This model is particularly suitable for Twitter data because it balances computational efficiency with strong performance in capturing semantic similarity across short, noisy, and context-dependent texts.

In terms of accuracy and reliability, BERTopic has been shown to produce more interpretable and thematically coherent clusters than LDA and other classical methods, especially in multilingual and short-text settings. While topic models are inherently probabilistic and thus subject to some degree of variability, the combination of contextual embeddings, dimensionality reduction, and density-based clustering improves robustness and reduces the risk of generating spurious topics. Accordingly, the approach provides a reliable method for capturing dominant narratives within Russian-language discourse on Twitter, while maintaining sufficient flexibility to detect emerging or minority perspectives.

BEND framework

Furthermore, this study employs a network-based approach to uncover the narratives and frames used in discourse with both anti-war opposition accounts and pro-government propaganda accounts. Social media information frames are strategic techniques designed to manipulate information flow to influence public perception and opinion. To characterize these frames, we applied the BEND maneuvers framework, which classifies 16 categories of information frames used for persuasion and manipulation51. The BEND framework serves as a critical tool for understanding strategic engagement and information influence52. It categorizes maneuvers into narrative maneuvers, which focus on message content, and network maneuvers, which reveal network structures and community interactions. ORA and NetMapper software was used to conduct BEND analysis (see Fig. 16 for an overview of BEND maneuvers).

The BEND framework integrates multiple existing frameworks, including the SCOTCH framework, which summarizes the contribution of social media actions to broader campaigns53, and the ABCD framework, which categorizes information maneuvers based on Actors, Behaviors, Content, and Distribution54. This framework has been previously applied to analyze the influence of information in contexts such as COVID-19 narratives in Pennsylvania55 and discourse surrounding Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny42. In this study, we compare BEND maneuvers across opposition and pro-government discourse groups, as well as among bots identified in both groups.

In our study, we integrate BERTopic and the BEND framework to operationalize an approach to framing analysis in digital discourse. BERTopic is used to identify semantic clusters within the corpus of anti-war discourse. These clusters serve as proxies for potential frames, reflecting the recurring themes and narrative structures that shape how information is organized and perceived. By detecting these topics, we obtain a data-driven overview of the cognitive structures, the “incoming frames”, that underpin discourse in the Russian Twitter sphere.

BEND maneuvers, in turn, provide a complementary perspective by focusing on the communicative strategies employed by actors to influence, reinforce, or shift these frames. Whereas frames represent the audience-facing cognitive schema, BEND captures the observable, actionable behaviors of message senders, such as amplifying certain messages (Excite, Explain), suppressing opposing narratives (Distract, Dismiss), or mobilizing collective action (Engage). Through BEND, we can analyze the outgoing frame management, showing how actors attempt to shape the perception of others within certain topic clusters.

By combining BERTopic and BEND, our approach allows for a holistic view of framing in digital discourse: BERTopic identifies what is being framed (topic clusters and thematic structures), while BEND captures how it is being framed (strategic maneuvers that influence interpretation). This dual method bridges the gap between cognitive and communicative dimensions of framing, making it possible to empirically observe the strategies through which discourse actors activate, reinforce, or contest frames in a social media dataset.

Data availability

No data is provided with this manuscript. Data and code can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, in accordance with the policy of Twitter/X.

References

Petrov, N., Lipman, M. & Hale, H. E. Three dilemmas of hybrid regime governance: Russia from Putin to Putin. Post-Sov. Aff. 30, 1–26 (2014).

Denisova, A. Democracy, protest and public sphere in Russia after the 2011–2012 anti-government protests: digital media at stake. Media Cult. Soc. 39, 976–994 (2017).

Shirky, C. The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs Foreign Affairs 90, 28–41 (2011).

Kolesnikov, A. Putin’s war has moved Russia from authoritarianism to hybrid totalitarianism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/04/putins-war-has-moved-russia-from-authoritarianism-to-hybrid-totalitarianism?lang=en (2022).

Kiriya, I. New and old institutions within the Russian media system. Russian J. Commun. 11, 6–21 (2019).

Zassoursky, I. Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia (Routledge, 2016).

Vartanova, E. The Russian media model in the context of post-Soviet dynamics. in Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, (eds Hallin, D., Mancini, P.) pp. 119–142 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

De Smaele, H. The applicability of Western media models on the Russian media system. Eur. J. Commun. 14, 173–189 (1999).

Becker, J. Lessons from Russia: a neo-authoritarian media system. Eur. J. Commun. 19, 139–163 (2004).

Hinck, R. S., Kluver, R. & Cooley, S. Russia re-envisions the world: Strategic narratives in Russian broadcast and news media during 2015. Russian. J. Commun. 10, 21–37 (2018).

Sanovich, S., Stukal, D. & Tucker, J. A. Turning the virtual tables: government strategies for addressing online opposition with an application to Russia. Comp. Polit. 50, 435–482 (2018).

Kiriya, I. From “troll factories” to “littering the information space”: control strategies over the Russian internet. Media Commun. 9, 144–154 (2021).

Makhortykh, M., Urman, A. & Wijermars, M. A story of (non) compliance, bias, and conspiracies: How Google and Yandex represented Smart Voting during the 2021 parliamentary elections in Russia. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 3. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/a-story-of-noncompliance-bias-and-conspiracies-how-google-and-yandex-represented-smart-voting-during-the-2021-parliamentary-elections-in-russia/ (2022).

Kravets, D. Yandex’s Top-5 news as a tool of Russia’s propaganda abroad: a case study of Belarus. Int. J. Press/Politics 0, 1-24. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/19401612251349018 (2025).

OVD-Info: Cracking Down on Freedom of Expression: How Russian Authorities and Big Tech Companies Silence Dissent. OVD-Info https://ovd.info/en/advocacy/impact-disinformation-enjoyment-and-realisation-human-rights (2025).

Loucaides, D. The Kremlin Has Entered the Chat. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/the-kremlin-has-entered-the-chat/ (2023).

Levada Center: Problemy s dostupom k internet-resursam i polʹzovanie VPN: [Problems accessing internet resources and VPN usage]. Levada Center. https://www.levada.ru/2025/04/22/problemy-s-dostupom-k-internet-resursam-i-polzovanie-vpn-mart-2025/ (2025).

Castro, C. A new chapter in repressive Internet regulation in Russia—experts explain how Russia’s new law will affect VPN users. TechRadar https://www.techradar.com/vpn/vpn-privacy-security/a-new-chapter-in-repressive-internet-regulation-in-russia-experts-explain-how-russias-new-law-will-affect-vpn-users (2025).

Darbinyan, S. Russia’s internet crackdown is in a dangerous new phase. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8a71052d-d26d-4d71-95d8-c8886ca4fdea (2025).

Pomerantsev, P. Nothing is True and Everything is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia (Public Affairs, 2014).

Yablokov, I. Conspiracy theories as a Russian public diplomacy tool: the case of Russia Today (RT). Politics 35, 301–315 (2015).

Darczewska, J. The anatomy of Russian information warfare: The Crimean operation, a case study. Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW) https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/point-view/2014-05-22/anatomy-russian-information-warfare-crimean-operation-a-case-study (2014).

Badawy, A., Addawood, A., Lerman, K. & Ferrara, E. Characterizing the 2016 Russian IRA influence campaign. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Bastos, M. & Mercea, D. The public accountability of social platforms: lessons from a study on bots and trolls in the Brexit campaign. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20180003 (2018).

Linvill, D. L. & Warren, P. L. Troll factories: manufacturing specialized disinformation on Twitter. Political Commun. 37, 447–467 (2020).

Alieva, I., Kloo, I. & Carley, K. M. Analyzing Russia’s propaganda tactics on Twitter using mixed methods network analysis and natural language processing: a case study of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. EPJ Data Sci. 13, 42 (2024).

Geissler, D., Bar, D., Prollochs, N. & Feuerriegel, S. Russian propaganda on social media during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. EPJ Data Sci. 12, 35 (2023).

Alaphilippe, A., Machado, G., Miguel, R., Poldi, F. Doppelgänger – Media clones serving Russian propaganda. EU DisinfoLab. https://www.disinfo.eu/doppelganger/ (2022).

Bernhard, M., Hock, A., Thust, S. Inside Doppelgänger – How Russia uses EU companies for its propaganda. CORRECTIV. https://correctiv.org/en/fact-checking-en/2024/07/22/inside-doppelganger-how-russia-uses-eu-companies-for-its-propaganda/ (2024).

Oliker, O. Russia’s new military doctrine: Same as the old doctrine, mostly. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/01/15/russias-new-military-doctrine-same-as-the-old-doctrine-mostly/ (2015).

Pomerantsev, P. et al. Why conspiratorial propaganda works and what we can do about it: Audience vulnerability and resistance to anti-Western, pro-Kremlin disinformation in Ukraine. Lond. School Econ.Polit. Sci. https://www.lse.ac.uk/iga/assets/documents/arena/2021/Conspiratorial-propaganda-anti-West-narratives-Ukraine-report-light.pdf (2021).

Ellick, A. B., Westbrook, A. & Kessel, J. M. Meet the KGB spies who invented fake news. New York Times 12 (2018).

Alieva, I., Ng, L. H. X. & Carley, K. M. Investigating the Spread of Russian Disinformation about Biolabs in Ukraine on Twitter Using Social Network Analysis. in IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), pp. 1770–1775 (IEEE, 2022b).

Wanless, A. & Berk, M. The changing nature of propaganda: coming to terms with influence in conflict. in The World Information Warpp. 63–80 (Routledge, 2021).

Starbird, K. Disinformation’s spread: Bots, trolls and all of us. Nature 571, 449–450 (2019).

Hyzen, A. Revisiting the theoretical foundations of propaganda. Int. J. Commun. 15, 3479–3496 (2021).

Gitlin, T. The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left (University of California Press, 2003).

Gamson, W. A. & Modigliani, A. The changing culture of affirmative action. Res. Political Sociol. 3, 137–177 (1987).

Entman, R. M., Matthes, J. & Pellicano, L. Nature, sources, and effects of news framing. in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, pp. 175–190 (Routledge, 2009).

Entman, R. M. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58 (1993).

Xanthopoulos, P., Panagopoulos, O. P., Bakamitsos, G. A. & Freudmann, E. Hashtag hijacking: What it is, why it happens and how to avoid it. J. Digit. Soc. Media Mark. 3, 353–362 (2016).

Alieva, I., Moffitt, J. D. & Carley, K. M. How disinformation operations against Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny influence the international audience on Twitter. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 12, 80 (2022).

Alieva, I., Ng, L. H. X. & Carley, K. M. Investigating the Spread of Russian Disinformation about Biolabs in Ukraine on Twitter Using Social Network Analysis. in IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), pp. 1770–1775 (IEEE, 2022).

Uyheng, J. & Carley, K. M. Characterizing bot networks on Twitter: an empirical analysis of contentious issues in the Asia-Pacific. in International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling and Simulation (pp. 153–162) (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Carley, K. M. ORA: A Toolkit for Dynamic Network Analysis and Visualization. in Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining (Springer, 2014).

Beskow, D. M. & Carley, K. M. Bot-hunter: a tiered approach to detecting & characterizing automated activity on Twitter. in SBP-BRiMS: International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling and Simulation Vol. 3. (2018).

Traag, V. A., Waltman, L. & Van Eck, N. J. From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–12 (2019).

Magelinski, T., Ng, L. & Carley, K. M. A synchronized action framework for detection of coordination on social media. J. Online Trust Safety 1, 1−24 (2022).

de Groot, M., Aliannejadi, M. & Haas, M. R. Experiments on generalizability of BERTopic on multi-domain short text. arXiv.org. (2022) https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.08459 (2022).

Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05794. (2022).

Beskow, D. M. & Carley, K. M. Social cybersecurity: an emerging national security requirement. Mil. Rev. 99, 117–127 (2019).

Carley, K. M. Social cybersecurity: an emerging science. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 26, 365–381 (2020).

Blazek, S. SCOTCH: A framework for rapidly assessing influence operations. Atlantic Council (2021). Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/geotech-cues/scotch-a-framework-for-rapidly-assessing-influence-operations/.

Alaphilippe, A. Adding a ‘D’ to the ABC Disinformation Framework (Brookings, 2020).

Alieva, I., Robertson, D. & Carley, K. M. Localizing COVID-19 misinformation: a case study of tracking Twitter pandemic narratives in Pennsylvania using computational network science. J. Health Commun. 28, 76–85 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Center for Computational Analysis of Social and Organizational Systems (CASOS) and the Center for Informed Democracy and Social-cybersecurity (IDeaS) at Carnegie Mellon University.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.A. conceptualized the study and performed the data collection, analysis and writing. K.M.C. reviewed the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alieva, I., Carley, K.M. Dynamics of Russian anti-war discourse on X (Twitter): a computational analysis using NLP and network methods. npj Complex 3, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44260-025-00059-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44260-025-00059-7