Abstract

In Indonesia, smallholder farmers play a crucial role in preserving biodiversity and cultural practices closely tied to food security. However, they face numerous sustainability challenges. Agroecology offers a promising approach to address these challenges by putting emphasis on earth’s carrying capacity and social equity. This study surveyed 442 smallholder farmers in different sub-districts of Malang and Lamongan provinces to assess their perceptions around agroecological principles. Using a 5-point Likert scale, the study captured and analyzed farmers’ perceptions and correlated these with their agricultural practices. Practices such as the overuse and underuse of fertilizers and imprudent pesticide applications were documented, while uncertainties in farmers’ capacity in adapting to unforeseen events were apparent. Despite limited awareness about biodiversity loss and soil degradation, many farmers believed in their potential to contribute to environmental restoration and most of them expressed satisfaction with their quality of life and income levels. Such insights were used to determine transition pathways towards more agroecological farming systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smallholder farmers, typically operating on farms smaller than two hectares, play a significant role in global agriculture. In low and lower-middle-income countries, such as those in Asia and the Pacific, approximately 80% of farms fall into this category. These farms collectively occupy 30-40% of agricultural land and contribute approximately 30% of global food production1. In tropical regions, smallholder farmers are particularly noted for their vital role in preserving biodiversity within agricultural landscapes1,2. Their deep knowledge of crop ecology, biodiversity, and motivations are deeply rooted in their cultural heritage, encompassing long-held traditions and values3. Over recent decades, tropical agriculture has undergone significant transformations driven by population growth, migration, and the expansion of cultivated land. Trends in smallholder farming have shown an increasing reliance on inorganic fertilizers, pesticides, and improved seeds, similar to trends observed in other parts of Asia where modernization policies have led to increased use of these inputs4,5. Understanding these trends is essential for contextualizing the potential for agroecological transitions in Indonesia. These changes have also led to a rapid decline in species diversity and environmental degradation6. Undoubtedly, the role of smallholder farmers in the tropics is pivotal in pursuing sustainable food production, as the sustainability of agriculture relies heavily on their perception, decisions, and farming practices7.

While technological advancements and resource availability significantly enhance agricultural productivity and livelihoods, adopting these innovations is intricately linked to farmers’ perceptions and decision-making processes8. Human behavior is complex, context-dependent, and dynamic, beginning with perception9. The perceptions are deeply intertwined with an individual’s societal position and prevailing social norms. For example, higher socioeconomic status and greater access to information tend to increase the perceived importance of sustainable agriculture10.

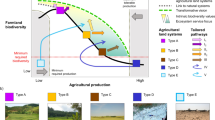

Agroecology, as defined by the FAO11, simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agriculture and food systems. It involves reducing and eliminating synthetic inputs such as inorganic fertilizers and pesticides while enhancing biodiversity and ecosystem services. Agroecology is underpinned by three operational principles: (1) strengthen the resilience of farming systems, (2) improve resource use efficiency and (3) secure social equity and responsibility10. There is growing evidence of agroecology’s potential to address multiple challenges in the food production system and the transition from conventional farming to agroecology is possible with the presence of key change agents and enabling environments1,12,13,14. Agroecological transition is the significant temporal and spatial shift in a farm or food system through the application of agroecological principles15. These transitions are crucial for sustainable food production systems and require a comprehensive understanding of farmers’ perceptions and capabilities. Farmers play a pivotal role in driving these transitions, and their perceptions, goals, and knowledge must align with broader food system support, including access to knowledge, markets, and social networks for the transition to occur.

Indonesia, the fourth most populous country globally, faces the pressing challenge of sustaining its massive population, with over 50% residing on Java Island. The country boasts rich biodiversity and cultural heritage rooted in millennia of agricultural traditions16, making the preservation of these resources paramount. Indonesia offers examples where specific farming communities have tested agroecological practices to varying degrees. In East Java, farmers practice traditional rice polycultures called complex rice systems (CRS) that integrate several plant and animal species in the farms17. CRS, examined in detail, had higher resilience to the effects of extreme weather events, less reliance on agrochemicals, and higher and stable rice yields over time than conventional monoculture18. There is, however, consistent pressure to increase rice yields in Java, which supplies the highest amount among all the provinces in the country19. Farmers’ agroecological practices amidst growing development pressure make East Java an ideal study site for an in-depth examination of their perceptions and practices and entry points for agroecological transition.

This paper specifically aims to answer two key research questions: (1) What are the farmers’ perceptions of agroecology? and (2) Where are the entry points for agroecological transition through potential change in the farmers’ perception and practice?

Results

Farmers profile

In the study sites, most farmers are smallholders having less than two hectares of land. The average landholding size was 0.46 hectares in Malang and 0.57 hectares in Lamongan (Table 1).

The demographic profile indicates that farmers are mostly middle-aged, with a median age of 55 in Malang and 52 in Lamongan. The farmers in both regions have considerable farming experience, averaging 29 years in Malang and 27 years in Lamongan, with some individuals having up to 65 years of experience. The family involvement in farm work is low, with a median of one family member in Malang and two in Lamongan. The data also show that most of the farms are fully owned by the farmers—90% in Malang and 88% in Lamongan—providing them with significant autonomy in decision-making. Gender distribution among the farmers shows a notable male dominance in both regions. In Malang, 76% of the farmers were male and 24% were female. Similarly, in Lamongan, 77% of the farmers were male, and 23% were female. This disparity is also reflected in educational attainment, where 76-78% of the farmers who attended school were male, and only 23-24% were female. In Malang, 44% of the farmers had completed primary education, 48% had secondary education, 3% had a university education, and 6% had no formal education. In contrast, Lamongan had a higher percentage of secondary education completion (72%), with 24% having primary education, 5% possessing a university education, and 1% with no formal education.

The aspirations of farmers regarding their agricultural activities vary between the two regions. In Malang, 59% of the respondents expressed a desire to increase their production and sales, while 20% preferred to maintain their current production levels. Only 6% of the farmers in Malang showed interest in diversifying their crops and adopting more environmentally friendly farming practices, and a mere 1% are seeking alternative livelihoods beyond farming. In contrast, in Lamongan, 46% of the respondents aimed to increase their production and sales, while 20% were satisfied with their current output. Interestingly, 15% of Lamongan farmers expressed a desire to switch to more sustainable farming methods and crop diversification, and another 1% sought non-farming livelihoods.

Farmers’ perception on agroecological practices

This section presents the farmers’ perceptions on various aspects of agroecological principles. The analysis is structured into two parts: an overview of perceptions on ecological concepts, environmental change, and social dynamics (Table 3), followed by an in-depth examination of specific agroecological concepts and actions.

Overview of perceptions

Awareness on ecological concepts and response to environmental change: Farmers demonstrated an awareness of biodiversity, soil health, climate change, and agrochemical use. Respondents acknowledged the importance of biodiversity and its role in farming, recognized human activities as contributors to climate change, and noted the impact of extreme weather events on crop yields. However, they expressed neutral views on the consequences of species loss for their farms. Perceptions on fertilizer and pesticide use were mixed. While farmers believed they could replenish soil nutrients and that collective action had a more significant impact, many assumed biodiversity could naturally recover and considered it the responsibility of governmental and non-governmental organizations to restore it.

Awareness on the state of their environment and social relations: Farmers largely agreed that their local air and water quality were good and expressed satisfaction with their income and profession. They held neutral views on soil health and adaptability to change. However, there was strong disagreement regarding the presence of new agricultural alliances with private or environmental sectors, suggesting limited external support. Additionally, there was consensus on the declining state of biodiversity, soil health, and farmers’ capacity to adapt to abrupt changes. Farmers’ views on youth involvement, labor availability, and access to information were divided.

In-depth exploration of perceptions

Farmers showed an eco-conscious perception towards the concept of biodiversity, indicating a good understanding of its importance (Fig. 1a). In Lamongan, farmers recognized biodiversity loss but were uncertain about its extent, and they considered the available plant and animal species sufficient for their needs. In contrast, respondents in Malang were unsure if any biodiversity loss had occurred in their area, suggesting that such loss might not be easily observable, although there is a strong baseline awareness of biodiversity, supported by the diversity of species they grow in their farms and home gardens.

The radar charts display the median Likert scale scores (1–5) for each statement, with the parentheses indicating significant spatial differences (p < 0.05) within a site (S=significant, NS=nonsignificant). The left panel represents “Ecoconscious” farmers (a, b), while the right side shows “Econeutral/skeptic” farmers (c). The green shading marks the agreement zone, while red shading represents disagreement (Likert scale scores of 1 and 2). The red and blue lines indicate responses from Lamongan and Malang, respectively.

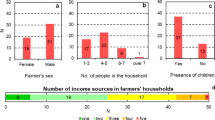

Regarding soil quality, farmers in Malang remained neutral, while those in Lamongan believed that the soil needs rest but also depends on commercial inorganic fertilizers to maintain good soil quality (Fig. 2a). The optimal use of nitrogen in paddy fields was used as the benchmark for assessing the appropriate application of fertilizers. Farmers believed they were optimizing fertilizer use by splitting applications according to plant growth stages, but there was an apparent lack of awareness regarding the optimal use of nitrogen fertilizers (Fig. 1b). This was verified by asking farmers about their actual nitrogen use in rice fields. The data indicated that most farmers in Malang and Lamongan applied more nitrogen than recommended (Fig. 3), with Malang farmers applying the most. The recommended amount of N for rice is between 100–150 kg/ha20; however, 75% of Malang farmers and 53% of Lamongan farmers exceeded this amount (Fig. 3). Conversely, 22% of Lamongan farmers and 10% of Malang farmers applied less than the recommended range. Overuse of nitrogen can lead to environmental degradation, while underuse can deplete soil nutrients. Interestingly, higher nitrogen use in Malang (median yield of 6 t/ha) did not translate into higher yields compared to Lamongan (8.04 t/ha), highlighting inefficiencies in fertilizer use. The results also indicate that a majority of the respondents adopt an imprudent approach to pesticide use, as evidenced by the prevalent belief that pesticides do not pose a threat to the environment (Fig. 1b). Conversely, approximately 20-40% of the respondents in Lamongan have consistently demonstrated a more cautious perspective. This implies a diversity in the level of consciousness and orientation towards pesticide use among the farmers.

The radar charts display the median Likert scale scores (1–5) for each statement, with the parentheses indicating significant spatial differences (p < 0.05) within a site (S=significant, NS=nonsignificant). The left side represents “Ecoconscious” farmers (a, b, c), while the right side shows “Econeutral/skeptic” farmers (d, e). The green shading marks the agreement zone, while red shading represents disagreement (Likert scale scores of 1 and 2). The red and blue lines indicate responses from Lamongan and Malang, respectively.

Both groups were neutral on observing soil degradation in their areas (Fig. 2d), likely because soil degradation is not readily observable, especially when farmers can access fertilizers and restore nutrients in the soil. Farmers in both sites agreed that crops take nutrition from the soil. Despite signs of soil degradation, farmers from both sites did not express an intention to shift away from farming. Climate change awareness was limited, with farmers in Lamongan attributing it to natural events, while Malang respondents remained uncertain. Extreme weather events were acknowledged as threats to crop yields, but personal experiences with such events varied.

Farmers from both regions believed that they could take action to improve the soil fertility, and that collective action would have a greater impact than individual actions (Fig. 1b). In Lamongan, farmers were optimistic about their ability to increase biodiversity, whereas Malang farmers were neutral. Farmers shared individual strategies for biodiversity and soil restoration (Fig. 4).

Despite the dominance of rice farming in the region, the survey documented 24 species cultivated across different food groups, including cereals, roots/tubers, vegetables, fish/seafood, fruits, sugar, pulses, and meat. Lamongan farmers cultivated a greater diversity of crops than Malang farmers (Table 2). The potential impacts of resource use inefficiency, such as water and air pollution and water depletion, were also considered.

Perceptions of water and air quality were largely positive, with 83-97% of respondents reporting no significant water scarcity or pollution (Fig. 2a). However, some Lamongan farmers reported localized water issues. Similarly, most farmers considered their air quality favorable, with no significant pollution concerns (Fig. 2d).

Labor costs were perceived differently between the two provinces. Farmers in Malang perceived labor as affordable (Fig. 2b), while Lamongan respondents found it expensive (Fig. 2e). Labor scarcity in Lamongan has driven a preference for mechanization, with 74% of respondents indicated a preference for machinery over hired labor (Fig. 2b). This preference aligns with the limited family labor availability, as most farms are operated by one or two family members only.

In terms of community resilience, farmers believed they could meet their daily food needs (Fig. 2c) and disagreed with the notion that farming alone is insufficient for them to adapt to change (Fig. 2e). However, when asked about adaptation in more detail, they expressed neutrality, except when income support from family and savings was involved (Fig. 2c).

The results show that farmers in Lamongan and Malang have different perceptions regarding access to information about farming, its usefulness, and the existence of farmer-researcher partnerships. Farmers in Lamongan hold negative views, whereas those in Malang express positive ones (Fig. 2b). Preferred information sources were consistent across both areas, with personal experience, agricultural extension agents, and peer farmers ranking highest, followed by television and YouTube. Less favored sources included university education, parental experience, google, books, radio, leaflets/posters, and agricultural input sellers (Supplementary Fig. 1). In terms of forming new alliances, farmers in both regions have limited awareness of partnerships with private and environmental sectors. Nevertheless, a significant portion of farmers—42% in Malang and 38% in Lamongan—acknowledged the agricultural sector’s (government and NGO) role in improving their farming practices.

Youth involvement in farming remains a concern, with most farmers largely agreed that youth showed little interest in farming (Fig. 2b). This perception aligns with the demographic data, where youth (ages 20-36) constituted only 4% of the sample population. The farmers, however, believed that young people are not entirely disinterested in farming (Fig. 2e), suggesting that other factors might impede youth participation, such as economic or social barriers. In terms of income and well-being, most farmers expressed satisfaction with their earnings from agriculture and planned to continue farming (Fig. 2b), which affirms the viability and rewarding nature of agriculture as a livelihood in these regions.

The study also examined gender dynamics in resource ownership, decision-making, and the division of labor among farmers (Fig. 5). In Lamongan, where aquaculture is prominent, farmers owned various assets such as transportation, cell phones, jewelry, appliances, houses, agricultural land, and farm equipment. However, ownership of certain assets like fishpond equipment, poultry, and both small and large livestock is limited (below 50%). Asset ownership exhibits clear gender differentiation: men predominantly own farm equipment while women typically possess poultry, other small animals, and jewelry. Other assets, such as houses and appliances, are jointly owned. Decision-making authority also follows a gendered pattern, with men controlling farm-related assets and women overseeing household-related assets. The division of labor in Lamongan is distinctly gendered, with men mainly handling farm chores except for crop planting and harvesting and poultry care, where women are significantly involved. A minor proportion of farm work is collaboratively undertaken by both genders, showing some cooperation and flexibility. Women primarily manage household chores, while both genders contribute to elder care, community work, and religious activities. However, men are more likely to participate in farmer meetings, potentially gaining greater access to information and networks. Although women generally manage the income, financial decisions are made by both spouses.

In Malang, a mountainous district with a diverse agricultural sector, farmers also own similar assets, such as transportation, cellphones, appliances, houses, non-mechanized farm equipment, and agricultural land. Almost all of them responded to having jewelry and mechanized farm equipment, which suggests a higher level of wealth and modernization. About 70% of farmers own poultry and other small animals, whereas less than 50% own small and large livestock. Only 3% possess fishpond or fishing equipment, which aligns with Malang’s ecological constraints against aquaculture. The gender division of ownership in Malang mirrors that of Lamongan, with husbands having greater ownership of farm and fishpond equipment, poultry, small and large livestock, cellphones, and transportation, while wives predominantly own jewelry. Ownership of houses and appliances is shared between spouses. Decision-making power is similarly gender-divided, with husbands influencing farm-related assets and wives influencing household-related assets.

The division of labor in Malang is more skewed towards men than in Lamongan, with men dominating all farm-related tasks, including planting and harvesting. Approximately 50% of respondents report sharing some farm duties with their spouses, indicating a relatively lower degree of cooperation and flexibility. Women predominantly manage household chores in Malang. Consistent with the patterns observed in Lamongan, both men and women participate in elder care, community work, and religious activities. Men are more frequently involved in attending farmer group meetings. While women generally manage the income, financial decision-making is undertaken jointly by both spouses.

Discussion

The demographic data indicate that most farmers are smallholders with extensive farming experience, yet they operate within the constraints of limited land and resources. The gender disparity in both educational attainment and farm ownership reflects broader socio-cultural dynamics that could influence the adoption of agroecological practices. The significant male dominance in farming activities, combined with the limited involvement of women, particularly in decision-making processes, highlights the need for targeted interventions to promote gender equity in agriculture. The low involvement of youth in farming is particularly concerning for the long-term sustainability of agriculture in these regions. With the farming population aging, there is an urgent need to engage younger generations in agriculture. Innovative strategies, such as integrating modern technologies and providing agricultural entrepreneurship training, could make farming more attractive to the youth.

While most aim to increase farm productivity and profitability, a smaller portion prioritizes the sustainability of their practices. These findings align with previous reports of challenges of smallholder farmers to achieve sustainable development goals21 and priority of profitability over sustainability by smallholder farmers22.

The farmers have a good level of awareness of biodiversity, as evidenced by their positive perceptions and diversity of plant species they grow in their farms and home gardens. This was also supported by a study done in the same area that quantifies the carbon and biodiversity value of farmers’ home gardens and border trees or trees they grow in the boundary of their farms1. However, this awareness does not consistently translate into sustainable farming practices. The data reveals a significant gap between knowledge and action, particularly concerning nitrogen use in rice farming. Farmers in both regions exceed recommended nitrogen levels, with Malang farmers applying almost four times the optimal amount. This over-reliance on inorganic fertilizers points to a disconnect between environmental awareness and practical application, a finding consistent with previous studies in Indonesia23.

The challenges of observing and responding to long-term environmental changes, such as biodiversity loss and soil degradation, are evident in the farmers’ neutral responses to related survey questions. This suggests that these phenomena are not readily observable at the farm level or are not prioritized by the farmers, possibly due to the immediate pressures of maintaining productivity24. However, the farmers’ willingness to engage in community actions that promote biodiversity and soil health presents a valuable entry point for agroecological interventions. Strengthening farmers’ capacity to monitor and respond to environmental changes, supported by research institutions, could bridge the gap between perception and practice.

The study also highlights the importance of experiential knowledge among these farmers, which, coupled with their relatively high levels of formal education, suggests a potential openness to new information and practices. Initiatives like Agroecological Crop Protection25, which integrate ecological principles into practical farming solutions, could be particularly effective in these regions. To facilitate this transition, it is crucial to establish strong partnerships between farmers and research institutions, ensuring that scientific knowledge is accessible and applicable to smallholder contexts26.

The food systems in Malang and Lamongan can be classified as intermediary, representing a transitional phase between traditional and modern systems. This is characteristic of many regions in Asia, where people predominantly purchase unprocessed or minimally processed foods from local markets or grocery stores27 rather than supermarkets. Although most food consumed by farmers is sourced externally, staple grains are still largely produced on their farms, indicating a degree of food self-sufficiency. However, this self-sufficiency is limited, making farmers vulnerable to fluctuations in food prices and availability, as well as to natural disasters and climate change, which could disrupt their food production and access. Moreover, farmers report insufficient access to financial support during crises, further limiting their capacity to cope with food shocks and threatening their food security and nutrition. To address these challenges, it is crucial to support social initiatives that are community-driven and aim to shift norms toward agroecological principles14. Strengthening local food production and consumption can enhance community resilience, laying the groundwork for a more robust and diverse food system in East Java.

The study’s findings on resource use efficiency indicate significant opportunities for improving both environmental sustainability and farm profitability. The over-application of fertilizers, imprudent pesticide use, and high labor costs are critical issues28 that must be addressed to enhance the sustainability of farming systems. Despite these challenges, the farmers generally perceive their water and air quality as good, indicating a lack of awareness or delayed recognition of the environmental impacts of their practices. This delayed perception is a common challenge in natural resource management, where the consequences of unsustainable practices may not become apparent until they are irreversible29.

Given that most farmers own their land, there is a strong incentive for them to invest in improving their farms’ long-term viability. Approaches such as integrated pest management, organic farming, and precision agriculture could offer viable solutions. However, changing farming practices is neither a simple nor a rapid process. It requires overcoming the barriers of habit, inertia, and uncertainty, which can influence the farmers’ decision-making and behavior. The habitual nature of farming practices, as explained by reinforcement learning30 and habitual behavior theories31, suggests that people respond to stimuli through repeated reinforcement. Therefore, interventions must be designed to gradually shift farmers’ practices through iterative learning32 and positive reinforcement. This could involve providing immediate, tangible benefits from adopting sustainable practices, thus aligning environmental goals with the farmers’ economic motivations.

Improving resilience remains a significant challenge for farmers, though it aids in mitigating the shocks and stresses impacting their food systems. Resiliency can be enhanced through practices that restore soil health and biodiversity, such as agroforestry, conservation agriculture, or crop rotation33,34. However, this study shows that the farmers hold a neutral or ambiguous perception regarding the extent and impact of soil degradation and biodiversity loss, along with the difficulty in observing and measuring these parameters at the individual level. Farmers’ definitions and indicators of soil health and biodiversity may differ from those used in scientific contexts, influencing their assessments and valuations of these factors35. Therefore, resiliency may not serve as an effective entry point for engaging farmers in sustainability interventions if they do not perceive an urgent or tangible benefit. In contrast, resource use efficiency presents a more compelling entry point, as the farmers showed a greater certainty and interest in this area, often observing the benefits more quickly and directly. This behavior aligns with the literature on sustainability challenges, which suggests that people prefer interventions with more immediate and tangible benefits than those with more deferred and diffuse benefits36. To improve both the sustainability and resilience of the food system, it is crucial to align interventions with farmers’ preferences and motivations and to develop strategies that bridge environmental and economic goals. For instance, using composts could simultaneously improve resource use efficiency and enhance soil quality and fertility. Adopting a participatory approach to involve farmers in defining and measuring sustainability indicators, along with leveraging community-based initiatives, can further aid in designing effective interventions that foster both resource use efficiency and resilience, promoting collective action and social learning.

Social equity, particularly in terms of access to knowledge and resources37, remains a significant challenge for the agroecological transition in these regions. The study reveals a mixed picture, with farmers in Lamongan expressing more negative views on access to information and the effectiveness of farmer-researcher partnerships than those in Malang. This disparity highlights the uneven distribution of support services and the need for more inclusive and widespread knowledge dissemination strategies. Both horizontal (farmer-to-farmer) and vertical (across institutions) transmission of knowledge is necessary for spurring effective food systems change as defined in social theory12. Moreover, community resilience analysis indicates that farmers are inadequately prepared for abrupt shocks, such as disasters or large-scale pest infestations, where knowledge and partnerships can be crucial.

The findings also emphasize the critical role of youth involvement in agriculture. With only a small proportion of young people engaged in farming, there is an urgent need to create more attractive pathways for youth in agriculture. This could involve integrating modern technologies into farming practices, promoting agricultural entrepreneurship, and framing farming as an environmentally and socially valuable profession. Furthermore, the study points to the potential for strengthening social relations and forming new alliances across sectors. The current lack of collaboration between farmers and the private and environmental sectors suggests untapped opportunities for supporting agroecological transitions. Given that 90% of the farmers’ harvest is sold locally, engaging local consumers, who are crucial stakeholders in the food system, and promoting gender-equitable approaches38 to resource ownership and decision-making are also essential for building resilient and sustainable agricultural communities.

To facilitate the agroecological transition for smallholder farmers in East Java, several strategic actions are recommended:

-

i.

Educational Outreach and Capacity Building on Agroecology: Bridging the gap between awareness and practice requires targeted educational programs that engage farmers in participatory learning experiences. These programs should focus on the long-term benefits of agroecological practices and involve joint monitoring of environmental changes.

-

ii.

Promoting Resource Efficiency Initiatives: Given the concerns over resource use efficiency, particularly in fertilizer and pesticide management, programs aimed at training farmers in integrated pest management (IPM) and judicious input use should be strengthened. Such initiatives will help reduce reliance on chemicals and enhance environmental sustainability.

-

iii.

Strengthening Social Relations and Solutions: Community-based approaches should be prioritized to improve resilience against environmental and economic shocks. Establishing farmer cooperatives, which can leverage collective purchasing and marketing power, share risks, and provide mutual financial support systems, is crucial. Additionally, establishing partnerships across financial and environmental sectors will help bridge knowledge and financial gaps.

-

iv.

Policy Support and Incentives: Policymakers should develop frameworks that incentivize sustainable practices. This could include subsidies for agroforestry/regenerative agricultural practices, support for local consumption, and improved market access for smallholders. Such policies would enhance income security and encourage the adoption of agroecological practices.

-

v.

Monitoring and Evaluation of Agroecological Transitions: Continuous monitoring and evaluation are essential to assess the progress of agroecological transitions39. This process should include both biophysical and socioeconomic metrics to provide a holistic view of the impacts and to inform adaptive strategies.

Overall, this study has provided critical insights into smallholder farmers’ perceptions of agroecology in East Java. The findings indicate that while there is a general awareness of biodiversity and its importance, this awareness does not consistently translate into sustainable farming practices. The observed gap between knowledge and practical application underscores the need for targeted educational interventions focused on the long-term benefits of agroecological practices. Resource use efficiency emerges as a significant concern, with issues such as the over-application of fertilizers and pesticides posing threats to both environmental sustainability and farm profitability. Addressing these challenges requires not only technical solutions but also behavioral changes facilitated through participatory approaches and iterative learning processes. Social equity, particularly in terms of access to information and youth involvement in agriculture, remains a critical area for intervention. The study highlights the need for inclusive knowledge dissemination strategies and the development of pathways that make agriculture more attractive to younger generations. Additionally, promoting stronger social networks and partnerships across sectors will be essential in bridging existing gaps and supporting a more resilient and sustainable food system.

This study attempted to capture the complex and dynamic cognitive and environmental processes to understand the farmers’ collective thinking and actions. From which patterns and entry points for change can be discerned. The study’s reliance on self-reported data and Likert-scale statements that were locally translated may have introduced biases or confusion and limited the ability to capture the full complexity or precision of farmers’ perceptions. Additionally, the cross-sectional design does not account for changes in perceptions over time or the influence of external factors, highlighting the need for more robust mixed-method approaches in future research.

Methods

Conceptual framework

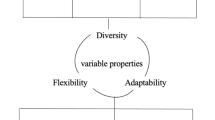

Sustainability in agriculture has been at the forefront due to the growing concerns about the long-term capacity of agroecosystems amid degrading environments, pollution, and climate change. Here, sustainability is defined as “a multidimensional concept of a dignified life for the present without compromising a dignified life in the future or endangering the natural environment and ecosystem services40. The ability of an agro-ecosystem to produce food depends on the natural resources and processes therein, which must operate within safe limits to maintain sustainability41.

In this study, sustainability is viewed through the lens of agroecology. Agroecology relies on the hypothesis that restoring the ecological structure and process in agroecosystems will sustain the delivery of ecosystem services crucial to the long-term performance of agriculture. The three pillars of agroecology considered in this study are resilience, resource-use efficiency, and social equity.

Human perception, a critical factor influencing behaviors toward agroecology, is the process by which individuals sense and interpret their social and biophysical environment9. As illustrated in Fig. 6, cognitive processes such as attention, updating/learning, valuation, and choice are innate parts of human perception that happen before the performance of a behavior. Aside from the perception, self-efficacy is another factor affecting the choice of sustainable behaviors. Self-efficacy is the belief that one can perform an action and is thus a motivational construct underlying choices, effort, persistence, and achievement42.

Adopted from the Human Behavior—Cognition in Context (Hub-CC) Framework8. The image “Rice Farmer Illustration” by Jom Plang is sourced from Canva, free to use by the author.

Cultural heritage and contexts and social class orientation developed in different ecological contexts affect farmers’ goals/motivation, knowledge, and assets. This all affects farmers’ perceptions. A holistic understanding of these connections helps explain why farmers think and act the way they do while understanding the cognitive processes involved in perception and behavior allowed us to identify entry points for change.

Study sites

The study was conducted in the districts of Lamongan and Malang in East Java, with two types of agroecosystems: lowland-sea and upland-lowland, respectively (see Fig. 7). Lamongan has a land area of 181,280 hectares, with a per capita land availability of 0.15 ha43, and around 85% of its land area is used for rice cultivation. The district is situated at an elevation of 2-50 meters above sea level (masl) and is known for its rice-fish farming systems, where brackish rice fields support the integration of shrimp farming systems44.

Malang, one of the most populous regions in East Java, has a per capita land availability of 0.13 ha. It has a land area of 353,065 hectares, with 49% used for agriculture. Its elevation ranges from 239–1157 masl, creating diverse lowland-upland ecosystems.

Drafting of the questionnaire and collection of data

The questionnaire was designed based on the three operational principles of agroecology: resilience, resource-use efficiency, and social equity. Indicators relevant to these principles and sustainable agriculture, drawn from the literature27,30,31,45,46,47,48,49, formed the basis for a set of 86 statements aimed at capturing respondents’ understanding and perception of these indicators.

The first part of the questionnaire was designed to collect the farmers’ profiles, including farm size and ownership, farmers’ age, education, gender, farming experience and objectives of farming, and family labor. The second part of the questionnaire was focused on perceptions on different topics related to agroecology. Respondent’s consent was secured before the data collection. The resilience section consisted of 52 statements, covering topics such as biodiversity loss, soil degradation, the concept and observation of climate change hazards, and community action. The resource use efficiency segment contained 20 statements, addressing topics on fertilizer and pesticide usage, labor productivity, air quality, and water quality. Lastly, the social equity part focused on 14 statements related to producers’ knowledge and practices, the formation of new alliances across disconnected domains, youth involvement, and income and well-being. To balance the tone of the statements, they were framed in both eco-conscious and eco-skeptic/neutral tones50. The farmers were asked to respond to each statement by using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly agree. Information on selected farming practices was also collected to provide a reference point for comparing perceptions with actions. Under the resilience section, the number of crops or fish that an individual farmer grows and the actions an individual can take to increase biodiversity and improve soil nutrients were asked. The nitrogen use per hectare of rice production and the yield data were collected for the resource use efficiency segment. Under social equity, the data collected were the source of information about farming and the ownership, decision-making, and division of labor between men and women. Data was collected digitally using the Open Data Kit app during surveys conducted with 442 farmers randomly sampled from five Malang districts and seven Lamongan districts in April and July 2022.

Data analysis

To provide an overview, the topics covered by the survey were clustered into three main groups: (a) awareness on ecological concepts, (b) response to environmental change, and (c) awareness on the state of their environment and social relations. The responses to the statements under the “awareness on ecological concepts” and “response to environmental change” statements were classified into two interpretative groups as (1) eco-conscious and (2) eco-skeptic/neutral. The responses were interpreted as “eco-conscious perception” if the respondents strongly agree/agree to eco-conscious statements or disagree to eco-skeptic statements. While “eco-skeptic/neutral perception” is the opposite; if the respondents strongly agree/agree/ or neutral to eco-skeptic/neutral statements or disagree to eco-conscious statements. Eco-conscious perception means farmers have knowledge of ecological concepts/processes and it translates to their care for the environment while eco-skeptic/neutral suggests limited ecological awareness or a lack of prioritization of environmental concerns .

The responses under the “awareness on the state of the environment and social relations” were interpreted as: (1) indication of a healthy state, (2) indication of a frail state, and (3) indication that state is not easily observable, or farmers are not aware, or it is not in their priority. The responses were interpreted as an indication of a “healthy state” if the respondents agree to eco-conscious statements or disagree to eco-skeptic statements, “frail state” if respondents agree to eco-skeptic/neutral statements or disagree to eco-conscious statements, and “state is not easily observable, farmers are not aware or not a priority” if they answered neutral. See Table 3.

Given that perceptions are known to vary between different environments51, the Kruskal-Wallis test (KW test) was used to investigate statistical relationships among farmers’ perceptions within different agroecosystems. This non-parametric test determined significant variations in farmers’ perceptions across different sub-districts in Malang and Lamongan. Statistical significance was tested at p < 0.05, with significantly different perceptions considered more impactful in the analysis. The median response for each question in each site was calculated to show central tendencies in perceptions, see Supplementary Table 3.

Data availability

The data is available upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

Kull, C. A. et al. Melting Pots of Biodiversity: Tropical Smallholder Farm Landscapes as Guarantors of Sustainability. Environment 55, 6–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2013.765307 (2013).

Asmara, D. H. et al. Spatial identification of lost-and-found carbon hotspots at Javanese rice systems, Indonesia. Agric. Syst. 214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103834 (2024).

Britwum, K. & Demont, M. Food security and the cultural heritage missing link. Glob. Food Secur.-Agr. 35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100660 (2022).

Khumairoh, U. et al. Linking types of East Javanese rice farming systems to farmers’ perceptions of complex rice systems. Agric. Syst. 218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104008 (2024).

Owemigisha, E. et al. Exploring knowledge, attitudes and practices of farmers at the edge of Budongo forest on agrochemicals usage. Sustain. Environ. 10, https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2023.2299537 (2024).

Lopez, M. I. & Suryomenggolo, J. Environmental resources use and challenges in contemporary Southeast Asia introduction. Asia Transit. 7, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8881-0_1 (2018).

ul Haq, S., Boz, I. & Shahbaz, P. Measuring Tea Farmers’ Perceptions of Sustainable Agriculture and Factors Affecting This Perception in Rize Province of Turkey. J. Agr. Sci. Tech.-Iran. 24, 1043–1056 (2022).

Meijer, S. S., Catacutan, D., Ajayi, O. C., Sileshi, G. W. & Nieuwenhuis, M. The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J. Agr. Sustain. 13, 40–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2014.912493 (2015).

Constantino, S. M., Schlüter, M., Weber, E. U. & Wijermans, N. Cognition and behavior in context: a framework and theories to explain natural resource use decisions in social-ecological systems. Sustain Sci. 16, 1651–1671, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00989-w (2021).

Füsun Tatlıdil, F., Boz, İ. & Tatlidil, H. Farmers’ perception of sustainable agriculture and its determinants: a case study in Kahramanmaras province of Turkey. Environ., Dev. Sustain. 11, 1091–1106, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-008-9168-x (2009).

FAO. Agroecology Knowledge Hub, http://www.fao.org/agroecology/home/en/ (2021).

Ong, T. W. Y. & Liao, W. Y. Agroecological Transitions: A Mathematical Perspective on a Transdisciplinary Problem. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00091 (2020).

Wezel, A. et al. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agron. Sustain Dev. 29, 503–515, https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009004 (2009).

IPES-Food. Breaking away from industrial food and farming systems: Seven case studies of agroecological transition. (2018).

Jones, S. K. et al. Research strategies to catalyze agroecological transitions in low- and middle-income countries. Sustain Sci. 17, 2651–2652, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01205-z (2022).

Wahyono, E. & Huda, N. Agricultural Extension Education in Indonesia in the Colonial Period 1900-1941. 2020 30, 15, https://doi.org/10.15294/paramita.v30i1.22893 (2020).

Khumairoh, U., Lantinga, E. A., Schulte, R. P. O., Suprayogo, D. & Groot, J. C. J. Complex rice systems to improve rice yield and yield stability in the face of variable weather conditions. Sci. Rep.-Uk 8, 14746, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32915-z (2018).

Khumairoh, U., Lantinga, E. A., Handriyadi, I., Schulte, R. P. O. & Groot, J. C. J. Agro-ecological mechanisms for weed and pest suppression and nutrient recycling in high yielding complex rice systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 313, 107385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2021.107385 (2021).

Makarim, A. Bridging the rice yield gap in Indonesia., 112-121 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok, Thailand, 2000).

Chivenge, P., Sharma, S., Bunquin, M. A. & Hellin, J. Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency-A Key for Sustainable Rice Production Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.737412 (2021).

Abraham, M. & Pingali, P. in The Role of Smallholder Farms in Food and Nutrition Security (eds Sergio Gomez y P., L. Riesgo & K. Louhichi) 173–209 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Eisenmenger, N. et al. The Sustainable Development Goals prioritize economic growth over sustainable resource use: a critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective. Sustain. Sci. 15, 1101–1110, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00813-x (2020).

Devkota, K. P. et al. Economic and environmental indicators of sustainable rice cultivation: A comparison across intensive irrigated rice cropping systems in six Asian countries. Ecol. Indic. 105, 199–214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.05.029 (2019).

Brussaard, L. et al. Reconciling biodiversity conservation and food security: scientific challenges for a new agriculture. Curr. Opin. Env Sust. 2, 34–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2010.03.007 (2010).

Deguine, J.-P. et al. in Advances in Agronomy 178 (ed D. L. Sparks) 1-59 (Academic Press, 2023).

Aerni, P., Nichterlein, K., Rudgard, S. & Sonnino, A. Making Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) work for development in tropical countries. Sustainability 7, 831–850 (2015).

Velten, S., Leventon, J., Jager, N. & Newig, J. What is sustainable agriculture? A systematic review. Sustainability 7, 7833–7865 (2015).

Prihandiani, A., Bella, D. R., Chairani, N. R., Winarto, Y. & Fox, J. The Tsunami of pesticide use for rice production on Java and its consequences. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 22, 276–297, https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2021.1942970 (2021).

Fernández-Llamazares, A. et al. Local perceptions as a guide for the sustainable management of natural resources: empirical evidence from a small-scale society in Bolivian Amazonia. Ecol. Soc. 21, https://doi.org/10.5751/Es-08092-210102 (2016).

FAO. Sustainability assessment of food and agriculture systems. Indicators., (Rome, Italy, 2013).

Slätmo, E., Fischer, K. & Röös, E. The framing of sustainability in sustainability assessment frameworks for agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 57, 378–395, https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12156 (2017).

Kolb, D. A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. (Prentice Hall, 1984).

Octavia, D. et al. Smart agroforestry for sustaining soil fertility and community livelihood. Sci. Technol. 19, 315–328, https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2023.2269970 (2023).

Duffy, C. et al. Agroforestry contributions to smallholder farmer food security in Indonesia. Agroforest Syst. 95, 1109–1124, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-021-00632-8 (2021).

Veisi, A., Khoshbakht, K., Veisi, H., Talarposhti, R. M. & Tanha, R. H. Integrating farmers’ and experts’ perspectives for soil health-informed decision-making in conservation agriculture systems. Environ. Syst. Decis. 44, 199–214, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-023-09923-0 (2024).

Carolan, M. S. Do you see what I see? Examining the epistemic barriers to sustainable agriculture. Rural Sociol. 71, 232–260, https://doi.org/10.1526/003601106777789756 (2006).

Magrini, M. B. et al. Agroecological transition from farms to territorialised agri-food systems: issues and drivers. Agroecol. Transitions, 69–98, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01953-2_5 (2019).

Qanti, S. R., Peralta, A. & Zeng, D. Social norms and perceptions drive women’s participation in agricultural decisions in West Java, Indonesia. Agric. Hum. Values 39, 645–662, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10277-z (2022).

Ewert, F., Baatz, R. & Finger, R. Agroecology for a sustainable agriculture and food system: from local solutions to large-scale adoption. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 15, 351–381, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-102422-090105 (2023).

Alaoui, A., Barao, L., Ferreira, C. S. S. & Hessel, R. An overview of sustainability assessment frameworks in agriculture. Land 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040537 (2022).

Rockström, J. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475, https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a (2009).

Schunk, D. H. & DiBenedetto, M. K. in Advances in Motivation Science 8 (ed. A. J. Elliot) 153-179 (Elsevier, 2021).

BPS-Statistics. (BPS-Statistics of Lamongan Regency, 2021).

Nurhidayati, D. R. et al. Rice-FISH FARMING System in Lamongan, East Java, Indonesia: SWOT and PROFIT EFFICIENCY ANalysis. Agric. Socio-Econ. J. XX, 311–318 (2020).

Chopin, P., Mubaya, C. P., Descheemaeker, K., Öborn, I. & Bergkvist, G. Avenues for improving farming sustainability assessment with upgraded tools, sustainability framing and indicators. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 41, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-021-00674-3 (2021).

Siebrecht, N. Sustainable agriculture and its implementation gap-overcoming obstacles to implementation. Sustainability 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093853 (2020).

SRP. Sustainable Rice Platform Performance Indicators for Sustainable Rice Cultivation (Version 2.1). (Bangkok, Thailand, 2022).

Gennari, P. & Navarro, D. K. The challenge of measuring agricultural sustainability in all its dimensions. J. Sustain. Res. 1, e190013, https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20190013 (2019).

de Olde, E. M., Oudshoorn, F. W., Sorensen, C. A. G., Bokkers, E. A. M. & de Boer, I. J. M. Assessing sustainability at farm-level: Lessons learned from a comparison of tools in practice. Ecol. Indic. 66, 391–404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.01.047 (2016).

Bloem, J. R. & Rahman, K. W. What I say depends on how you ask: Experimental evidence of the effect of framing on the measurement of attitudes. Econ. Lett. 238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2024.111686 (2024).

Ricart, S., Gandolfi, C. & Castelletti, A. Climate change awareness, perceived impacts, and adaptation from farmers’ experience and behavior: a triple-loop review. Reg. Environ. Change 23, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02078-3 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation through the CORIGAP project entitled “Closing Rice Yield Gaps in Asia with Reduced Environmental Footprint” (grant no. 81016734). The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr. Grant Singleton for securing the initial funding for the CORIGAP project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.: Data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. R.F.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing - review and editing. U.K.: Data collection, formal analysis, visualization, review and editing. A.R.: Data planning and analysis. D.H.A.: Data analysis. A.L.: Review and editing. S.Y.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing - review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Batas, M.A.A., Flor, R.J., Khumairoh, U. et al. Understanding smallholder farmers’ perceptions of agroecology. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00056-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00056-2