Abstract

Responsible plant nutrition requires innovation to improve nutrient use efficiency across diverse agricultural systems. This review highlights nanofertilizers, biofertilizers, and next-generation enhanced-efficiency fertilizers, examining nutrient-release mechanisms, yield impacts, environmental outcomes, and commercialization challenges. However, limited field data and standardized testing hinder progress. To advance fertilizer research, investments in shared protocols, global research networks, and pre-competitive studies are essential to close knowledge gaps, ensure food security, and reduce environmental harm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The large-scale production of mineral fertilizers was a major agricultural advancement that helped increase crop yields and economic development to feed a growing population1,2. However, the uneven use of fertilizers has resulted in nutrient surpluses in many parts of the world, as well as severe shortages in other areas3. Optimizing fertilizer inputs to increase crop production efficiency and reduce environmental impact is not trivial, and efforts are complicated by interactions and variability among plant, nutrient, edaphic, and climatic factors4,5,6. For the last two decades, the public and private sectors have promoted 4 R Nutrient Stewardship as the overarching concept for best fertilizer management practices, and its four pillars include applying the rate nutrient source at the right rate, right time, and right place7. Fundamentally, 4 R Nutrient Stewardship is not a one-size-fits-all approach, and the selection of fertilizer products and management practices is based on site conditions that may vary spatially and temporally. In practice, fertilizer management consists of suites of strategies that must be adapted to local conditions and to the fertilizer products (i.e., nutrient sources) applied. Though seemingly intuitive, this nimble aspect of nutrient management convolutes efforts to isolate the impacts of specific fertilizer products or management practices on crop production or environmental outcomes8. For instance, enhanced-efficiency fertilizers are products designed to enhance nutrient use efficiency9,10,11. Yet, teasing out which enhanced-efficiency fertilizer products work where, when, and at which rate is not always straightforward. Previous research suggests that certain fertilizer products may be more effective for a given combination of rate, timing, and placement12, while production and environmental outcomes likely depend upon the type of fertilizer, cropping system, and biophysical conditions13. To further complicate matters, the addition of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers may even lead to unintended consequences such as pollution swamping in some years14 but not others15, leading to uncertainty in their overall environmental impacts.

Advancements in fertilizer products are part of a new paradigm for responsible plant nutrition that advocates for a food systems and circular economy approach to feed the growing world population, improve soil and human health, mitigate and adapt to climate change and reduce environmental impacts16. Meeting these challenges requires innovation in science and technology to optimize nutrient use efficiency in diverse agricultural systems worldwide. However, as it stands, research on the use and effectiveness of the diverse fertilizer products remains limited, such as for nanofertilizers, biofertilizers, and next-generation enhanced efficiency fertilizers. A broader assessment of technology, data, and knowledge gaps is needed to help prioritize research and innovation to understand and manage the more nuanced impacts of fertilizers within the context of biophysical constraints and variable crop nutrient demand.

Recognizing that there is a wide range of innovations emerging that hold promise to enhance the use efficiency of plant nutrients (Table 1, Supplementary Data 1 and 2), the goal of this review paper is to identify priority areas for future research on efficient nutrient management and fertilizer technologies with a focus on nanofertilizers, biofertilizers, and next-generation enhanced efficiency fertilizers. Our first objective is to review the defining characteristics and modes of actions of these three categories of fertilizer technologies. Our second objective is to summarize evidence from the available scientific literature on the fertilizer use efficiency and environmental outcomes of these technologies. Our final objective is to recommend strategies for the prioritization of fertilizer research to address the limitations and uncertainties in the current literature. We explore the existing literature to examine scientific evidence for efficacy as a necessary (but not sufficient) element for a new fertilizer product to be effective for farmers. Additional research on a comprehensive listing of all available products or studies, market analyses, and detailed life cycle analysis of these fertilizer products is out of scope for this paper, but valuable future work to consider for promising fertilizer technologies.

Foundational research on enhanced efficiency fertilizers

The need for enhanced efficiency fertilizer (EEF) products was realized in the 1960s in light of the impacts of soil properties and crop growth on variable nutrient demand at different crop phenologic stages and the existence of many loss pathways17,18,19,20,21,22 (Fig. 1). The International Fertilizer Association (IFA) defines slow release fertilizers as products that release nutrients at a slower rate than their reference via biological, chemical, or biochemical mechanisms23, which are not necessarily well-controlled24. Examples include products such as sulfur-coated urea, neem-coated urea, urea supergranules, plant food sticks, and partially acidulated phosphate rock. Controlled release fertilizers (CRF), on the other hand, are products that release nutrients at a controlled rate relative to their reference through physical mechanisms such as coatings, encapsulation, or occlusions23. Examples include products such as polymer-coated fertilizers (Urea, NPKS, other straight fertilizers) or polymer-sulfur-coated urea. A third category is stabilized nitrogen fertilizers in which a more controlled-release or conversion is achieved through enzyme inhibitors (e.g., urease and nitrification inhibitors) designed to temporarily slow the biogeochemical transformation of urea or ammoniacal fertilizers24,25,26. Trenkel17 provides more detailed information on these major categories of EEFs and how they have been used in agriculture so far.

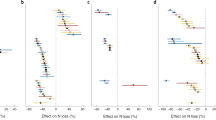

There is evidence that EEFs can have agronomic and environmental benefits. Meta-analyses suggest that yields are slightly higher on average when fertilizer is physically protected27,28 or treated with urease and/or nitrification inhibitors13,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, but the yield and/or recovery benefits are small and tend to depend on certain environmental conditions like soil pH37. In a second-order meta-analysis, Lam et al.9 concluded that EEFs reduced nitrate leaching by 17–58%, ammonia volatilization by 50–74%, and nitrous oxide emissions by 28–49%. One exception, however, was that the addition of nitrification inhibitors can lead to pollution swapping, by reducing nitrous oxide emissions and nitrate leaching at the expense of increasing ammonia emissions13,32,38,39. Nevertheless, the inclusion of both urease and nitrification inhibitors was effective at preventing this trade-off between mitigating ammonium versus nitrate losses9. The efficacy of nitrification inhibitors mitigating nitrous oxide losses is also similar across different types of inhibitor compounds and fertilizer sources, including both inorganic and organic fertilizers40. These results were confirmed by two other second-order meta-analysis studies, which reported that EEFs consistently reduced nitrous oxide emissions released to untreated fertilizers in agricultural soils41 and had the largest impact on increasing crop yields and nitrogen uptake while reducing nitrous oxide emissions, ammonia volatilization, and nitrogen surplus42.

Despite the evidence for the beneficial impacts of EEFs (Table 2), controlled and stabilized fertilizers products make up a fraction of the fertilizer market. Although demand for specialty fertilizers, including stabilized nitrogen fertilizers and controlled-release fertilizers, grew by 5% in 2023, these formulations make up less than 10% of the fertilizer market (IFA, personal communication). Cost is often cited as the major barrier to large-scale adoption13,43, with prices of EEFs being 30% to 10-fold greater than standard NPK fertilizers44. Additional barriers include environmental concerns associated with the use of non-biodegradable plastics in the case of polymer-coatings45. There have also been a few instances where the inappropriate use of inhibitors has inadvertently caused health concerns, such as in dairy production systems in New Zealand46. Hence, we recommend the following six criteria for any new EEFs breaking into the mainstream market: (1) meets the nutritional requirement of the crop, (2) includes biologically meaningful release mechanisms, (3) can be easily and safely transported, stored, and applied, (4) is environmentally safe, (5) poses no human or animal health risks, and (6) can be manufactured affordably at scale. In the following section, we will explore novel fertilizer products aiming to break through to the mainstream market (Fig. 2).

Nanofertilizers

Definitions and modes of actions

Nanoscale particles generally range from 1 to 100 nm in size and may be made from a wide range of raw materials47. At present, however, nanofertilizers are poorly regulated, and marketed fertilizer products may exceed this size range despite their use of the term “nanoscale.” Nanomaterials can be produced at low cost and at scale through top-down approaches, which utilize physical or chemical processes to grind, etch, or mill bulk materials to nanoscale particles or emulsions47. Mechanochemistry methods can also yield nanoscale products48. This contrasts with bottom-up approaches that involve smaller building blocks at the atomic or molecular scale to create nanoscale materials through self-assembly. Alternatively, nanofertilizers can be produced through biological or “green” synthesis methods49.

The primary argument for nanofertilizers as EEFs is that the high surface area and small size of the fertilizer particles may enhance the uptake of nutrients by plants through nanoscale pores in plant tissues, complexation with transporters or root exudates, and exploitation of ion channels50,51. This is of particular interest for foliar applications of fertilizer nutrients that tend to be less available to plants following soil application, such as phosphorus, manganese, iron, or zinc. Alternatively, nanostructures that encapsulate soluble fertilizers may control the release of nutrients of more mobile nutrients52. As outlined by Mastronardi et al.47, there are three main types of nanofertilizers: (i) nanoscale bulk fertilizer inputs (e.g., emulsified urea and ammonium salts sheared to nanoscale), (ii) nanoscale additives (e.g., NPK fertilizer containing nanocarbons), and (iii) nanoscale coatings or hosts (e.g., zeolite added to a composite fertilizer). Others conceptualize nanofertilizers by their composition52 (i.e., metallic nanomaterials, ceramic nanomaterials, and polymeric nanomaterials) or properties53 (i.e., nutrient-based, action-based, and consistency-based). The exploration of novel raw materials to manufacture nanofertilizers is an area of active research and development. Given that new ideas are emerging and being tested, we identify that more frequent reviews of literature might be needed.

Agronomic and environmental impacts

The impact of nanofertilizers on agronomic and environmental outcomes is still poorly understood, and a systematic, physiological, and molecular level understanding of their modes of action is needed54. Kah et al.55 performed a meta-analysis of 29 studies and reported positive effects on germination, plant growth, or yield for nanoscale macronutrients, micronutrients, and macronutrient carriers. However, the authors stated issues with low sample size, pervasive lack of fertilizer use efficiency data, absence of cereal crop studies, and little representation of field scale experiments. In another synthesis, Raimondi et al.56 found only nine studies that examined the impact of nanofertilizers on crop growth under field conditions. Of these, the majority were focused on micronutrient nanofertilizers, and the authors found that the studies reported mostly positive effects on various traits of interest, including yield, fruit set, soil properties, crop physiology, or water and nutrient use efficiency. Likewise, Quintarelli et al.57 reported enhanced stressed tolerance and biofortification of plants treated with nanofertilizers while also discussing the role of nanoparticles in achieving other plant production goals such as nanopesticides.

In a third analysis, Nongbet et al.58 reviewed 11 studies on the effects of foliar application of nanofertilizers, reporting enhanced yield, crop quality, growth, and disease suppression in all but one study, while acknowledging a lack of studies investigating environmental impacts. Lastly, Li et al.59 reviewed the ammonia mitigation efficiency of zeolite additives reported in seven papers and found reductions ranging from 25–50%, however, only one of these studies was a field study. To date, assessments of the environmental impacts of nanofertilizers under field conditions are lacking; only one study investigated nitrous oxide emissions60, and two monitored nitrate movement by soil depth61,62. While Hofmann et al.63 recognized the potential benefits of nano-carriers and nanoscale fertilizers (both macronutrients and micronutrients) to plant growth (as recently explored in a special issue64), field research is still needed before the technology can be considered commercialization-ready based on the scientific evidence of its performance.

Limitations and uncertainties

Depending on the nutrient, there may be an apparent contradiction with nanofertilizers in which the greater surface area, faster dissolution, and higher saturation solubility might actually lead to greater reactivity, decreased nutrient use efficiency, and exacerbated environmental losses47. Considering the lack of field trials53, the behavior of nanofertilizers beyond petri dishes and in the soil environment is poorly understood52,65. While foliar application of nanofertilizers could aid nutrient assimilation, we need a greater understanding of factors that regulate leaf and cellular uptake mechanisms, particularly in light of the heterogeneity of plant tissues and the barriers that nanoparticles must cross51. Furthermore, Mastronardi et al.47 states that many studies lack evidence on greater nutrient uptake and differences in dissolution kinetics and do not always identify the mechanisms for the positive effects on plant growth, while Husted et al.51 point to the lack of experimental controls. In general, sophisticated labeling techniques must be applied in combination with molecular studies to unravel the direct and indirect interactions that nanoparticles may trigger in plants and soil and their fate in the environment66.

Recently, nano-urea and nano-diammonium phosphate (DAP) have been commercialized in India and other countries. Claims have been made that small foliar applications of nano-urea appear to result in similar or even higher crop yields than those achieved with recommended, much larger amounts of granular nitrogen fertilizer67,68. This will require further independent evaluation, both in terms of mode of action and efficacy in the field. Many of the field trials conducted so far lack proper control treatments and measurements, so there are still no clear explanations for the potential underlying mechanisms or the long-term consequences of using products such as nano-urea or nano-DAP69. Recently, a first field trial was published that had a proper experimental design, including two extra controls with just spraying water or spraying dissolved urea, a robust set of measurements, proper data analysis, and interpretation70. This study was performed in soil in Punjab, India, that had no excessive N background. The results showed a 13–17% yield decrease in rice and wheat due to applying nano-urea in combination with a reduced normal N rate. In other words, contrary to what had often been claimed, the application of a small amount of N as nano-urea could not substitute for larger amounts of N needed by the crop and commonly applied through granule fertilizers. The experiment also showed that there was no unknown ‘biostimulatory effect’ due to the nanoparticles, i.e., the yields in treatments in which only dissolved urea was foliar-applied were the same as applying nano-urea.

More worrisome, but an opportunity for research and development, is the lack of functional nanoscale devices that release nutrients based on plant signals or in response to changing nutrient levels in the soil50. Little is understood about the potential for bioaccumulation of many nanoscale particles in the food chain, and there is some evidence of detrimental impacts of nanoparticle accumulations in plants71 and on soil microbiome72. Other potential barriers include the delivery at field scale, regulatory and safety concerns53, and consumer acceptance63,65. To overcome these constraints, researchers might look to the field of pharmaceutical drug development and the studies on complex biosystems to develop solutions dependent on biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity47,63.

In summary, while nanotechnology has the potential to provide novel solutions for agriculture, claims made must be supported by solid experimentation to back up the findings. Husted et al.73 point out that nanotechnology papers with an agricultural focus are frequently published with only a superficial understanding of basic plant and soil science, and these authors provide guidance on proper, hypothesis-driven experimentation. Scientific journals must ensure that editors and reviewers have in-depth expertise within the plant and soil disciplines to properly evaluate such research, particularly with regard to high-quality field evaluation.

Biofertilizers

Definitions and modes of actions

Biofertilizers are defined here as formulations that contain one or more strains of microorganisms that colonize the rhizosphere, rhizoplane, or root interior of a plant and enhance its nutrition by mobilizing or increasing nutrient availability in the soil62. These bioformulations are biological products that contain microbial inocula, solid or liquid carriers, additives, and/or treatments56. Biofertilizers are increasingly the subject of commercial interests, ranging from the emergence of startup companies backed by venture capitalists to established fertilizers companies embarking on their own development or aquisition of smaller companies. Therefore, robust evaluation is urgently needed to quantify the effectiveness of bioformulations.

Some researchers consider biofertilizers as a subcategory of the more general classification of plant growth promoting microorganisms because not all microorganisms that promote plant growth also increase nutrient availability74. Nevertheless, these terms are not mutually exclusive, and though the primary function of biofertilizers is to aid in the transformation and/or acquisition of plant-available nutrients, their activity may have plant growth-promoting impacts as a secondary function (e.g., imparting abiotic stress tolerance). Biofertilizers and plant growth promoting microorganisms more broadly may also be considered a subcategory of biostimulants75,76, which “support a plant’s natural processes independently of the biostimulant’s nutrient content, including by improving nutrient availability, uptake or use efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, and consequent growth, development, quality, or yield”77. Likewise, according to the European Biostimulants Industry Council, “Plant biostimulants means a material which contains substance(s) and/or microorganisms whose function, when applied to plants or the rhizosphere, is to stimulate natural processes to enhance/benefit nutrient uptake, nutrient efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, and crop quality, independent of its nutrient content.” However, like biofertilizers, there is no globally accepted definition for biostimulants for regulatory or commercial purposes.

The primary function of biofertilizers is to increase the availability of essential plant nutrients. General types of microorganisms include symbiotic and free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphorus-solubilizing and mineralizing bacteria or fungi, potassium-solubilizing bacteria or fungi, bacteria that oxidize sulfur, microorganisms that exude chelating agents or solubilize micronutrients, and mycorrhizal fungi78. Other authors have reviewed biofertilizers extensively and in great detail74,78 and discussed how bioformulation product development has largely moved away from single-strain inoculation in favor of microbial consortia to improve survival and function of the microorganisms and/or to provide synergism, such as between arbuscular mycorrhizae and nitrogen-fixing bacteria74,78. However, these microbial consortia may experience the same limitations that single-strain inocula face, including antagonistic interactions with resident microorganisms, failure to establish under a range of environmental and soil conditions, and lack of persistence with time79. Mitter et al.74 propose strategies to screen, design microbial inocula, and optimize formulations for storage and application in commercial production.

Translating the understanding of soil microbiome function to fertilizer product development remains a challenge, and the efficacy and survival of inoculations can be hindered by soil and environmental factors (e.g., presence of antagonists; abiotic factors such as climate, nutrient content, pH, organic matter, moisture, etc.), plant related challenges (e.g., specificity, colonization, or inefficient seed coating), poor ecological traits and tolerance74 or mixing with fertilizers or pesticides harmful to microorganisms. Therefore, alternative inoculum strategies might be necessary. One strategy is biofilmed biofertilizers that contain multi-species microbial communities within a suitable environment to enhance the competitiveness with the resident community and tolerate biotic and abiotic stress in the soil80. A second strategy might be the addition of “prebiotics” that act as microbial substrates or signals to stimulate the beneficial plant-associated microbiota81, such as root exudates (e.g., sugars, organic acids, amino acids, phenolic compounds, fatty acids, enzymes, growth factors, and proteins82) or plant-derived secondary metabolites. While prebiotics can be introduced in the absence of inoculation to promote the microbial functions in the resident community, Mitter et al.74 propose coupling prebiotics with microbial inoculants to increase biofertilizer efficiency and colonization.

Agronomic and environmental impacts

Schütz et al.83 performed a meta-analysis on five categories of biofertilizers (including arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, P solubilizers, N fixers, a combination of both P solubilization and N2 fixation) and reported that their impact on yield depended on environment and nutrient levels in the soil. Barbosa et al.84 found that inoculation of maize with nitrogen-fixing Azospirillum brasilense increased grain yield by 5%, with relatively greater responses at lower yields (<3000 kg/ha) and N application rates (<50 kg/ha). In contrast, Giller et al.85 found no reliable evidence for agronomically significant quantities of N2 fixation from microbial products used to inoculate cereals and other non-legumes with free-living and/or endophytic bacteria. In the review by Raimondi et al.56 on smart fertilizers, bioformulations made up only four of the 126 field-based studies. The authors reported that (1) the results were inconclusive, (2) the studies did not consider mass balance of nutrients, and (3) biofertilizers were likely not a substitution for fertilization. For bioformulations, it is not uncommon for a strain to perform well in vitro but not in the field86,87, and there is a need for more research to improve their performance under field conditions88. Furthermore, the literature on the environmental impacts of biofertilizers is scarce78. Li et al.59 reviewed seven field-based papers on the impact of biofertilizers on the mitigation of ammonia losses and reported that ammonia volatilization decreased by 32–76%. Field studies investigating nitrous oxide emissions are rare89,90,91,92 as well as those monitoring nitrate leaching93,94, though these papers reported neutral to positive impacts on the mitigation of losses.

Limitations and uncertainties

In order to regulate the release of biofertilizers with unsubstantiated claims, Giller et al.85 propose six criteria to provide and independently verify unequivocal evidence. While these authors reviewed free-living and/or endophytic N2-fixing bacteria, their recommendations can be generalized to biofertilizer products. These include measures to validate the detection, mechanisms, and efficacy of microbes in provisioning nutrients to major cereals and other crops. Standardized and universal testing protocols and evaluation guidelines can also help examine the inconsistent impacts across crops, soils, and environments in moving from lab to field pipeline. OʻCallaghan et al.78 called for more rigorous field testing in response to the deficit of field studies. They also cautioned readers about the risks of publication bias, the overestimation of effect size, non-reporting of confidence intervals, and lack of reproducibility56,95, while Mitter et al.74 stated additional challenges to commercialization, including the lack of recommendations, short shelf life of products and other logistical concerns, costs of scaling technologies, and the need to establish biosafety guidelines and understand risks to human health.

Novel enhanced-efficiency fertilizers

Definitions and modes of actions

Enhanced efficiency fertilizers include formulations that provide physical or biochemical mechanisms to control the release of nutrients. Controlled release materials fall under this umbrella, which can be defined as nutrients mixed or coated with one or more materials or additives that exploit synergy and affect nutrient release. However, there is a great deal of overlap between controlled-release fertilizers and nanofertilizers or biofertilizers, so the discussion here is limited to what has not been previously covered. More generally, traditional CRF fall within this category, in which coating or matrices physically control the release of nutrients via organic or inorganic materials, hydrogels, hydrophobic matrices, or low solubility minerals. An extensive review of CRFs has recently been published by Kassem et al.96 providing an in-depth analysis of the different approaches and materials used or under development. Likewise, stabilized forms of fertilizers, such as those treated with enzymatic inhibitors, too may be placed under the broader category of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers, in addition to other novel means to biochemically control the release of nutrients, such as via biosensors or plant signals56.

Physical control

Physical control release mechanisms can include reducing the solubility of fertilizer, increasing mechanical strength, and enhancing abrasion resistance56. Coated fertilizers are an example of this, in which a low-permeability film or matrix prevents physical contact between the fertilizer and soil to slow its release97. Scientists have explored an assortment of different coating materials, but the industry is aiming to develop fully biodegradable materials over environmental concerns of the use of plastics at micro or nano-scales that require time to degrade and release nutrients45,98. Hydrogel materials, as discussed earlier, are a type of innovative technology with super absorbent properties that can either be coated onto fertilizers or prepared as a matrix99. Hydrogels can be derived from naturally occurring sources or synthetic ones, and the most common polysaccharide materials include alginate, starch, cellulose, cyclodextrin, dextran, guar gum, pectin, chitosan, while acrylic acid or acrylamide are examples of synthetic sources98. Nanoparticles, also discussed earlier, can coat fertilizers to modify their solubility and nutrient release100. Ultimately, formulations would respond to stimuli and release nutrients as a function of environmental changes (e.g., pH, temperature, salinity, humidity, light)99, most reportedly governed by a diffusion mechanism96.

Biochemical control

Biochemical control release mechanisms exploit biochemical responses to delay nutrient release through the addition of biochemical sensors, enzyme inhibitors, or materials that alter their properties in response to major environmental factors56. The addition of biochemical inhibitors, either homogenized within or coated on fertilizer granules, can temporarily slow nutrient transformations by inhibiting enzyme activities97. Different types of urease and ammonia monooxygenase inhibitors exist on the market, but next-generation inhibitors might include analogs with structural variations (cyclic groups, heteroatoms, and polarity) to impart better efficiency under various environmental conditions, such as by increasing the compound’s temperature tolerance or lowering its volatility9. Thinking beyond these targeting microbial activity, novel plant-oriented approaches on the horizon rely on the plant-microbe interactions in which microbes use chemotaxis (or signaling) in response to signaling molecules such as proteins, peptides, lipids, RNA, phytohormones, and metabolites to attach to a root/form biofilm and aid in nutrient acquisition9. Novel formulations might include signaling molecules incorporated into the coat of fertilizers that can attract microbes in the rhizosphere to trigger nutrient release.

Another novel mechanism for controlled nutrient release is to embed biosensor or receptor molecules into the fertilizer coat to respond to plant signaling molecules and then release nutrients9. Aptamers, for example, are single-stranded synthetic oligonucleotides made using sequencing libraries that fold in unique shapes and bind to targets with high specificity, such as root exudates101. These molecules interact with their targets through non-covalent interactions and shape complementarity, and they behave like biosensors to target root exudates or biomarkers, which allow the fertilizer to “sense” plant signals to release102. In addition to aptamers, antibodies and molecular imprinted polymers are also affinity ligands that fall within this category. The assumption is that these biosensors are indicators of plant nutrient needs. However, more work is needed to develop viable products considering that some aptamers may have partial binding to solids that may challenge measurements in solution due to interference, and the technology is also more costly for longer aptamers103. Another area of growing interest is the incorporation of microbes (e.g., bacteria) into fertilizer coatings to ensure full biodegradation of coatings, i.e., without generating any microplastics or other harmful residues104. Microbes also generate hormones that can stimulate and regulate plant growth58,105,106, and novel fertilizers (e.g., bionanofertilizers) may include mechanisms that elicit a plant hormonal response107.

Agronomic and environmental impacts

Controlled release or stablilized formulations make up the vast majority of field studies reviewed by Raimondi et al.56. Sixty-six of the 126 studies tested polymer-coated urea, while 18 were devoted to inhibitors, with agronomic and environmental impacts confirming prior meta-analyses discussed above. Previous literature has well documented the beneficial impacts of the traditional controlled release and stabilized sources of nitrogen on the reduction of environmental impacts and yield gains9. However, certain fertilizer sources may be more effective for a given combination of rate, timing, and placement12, while crop yield and environmental outcomes likely depend upon the type of fertilizer, cropping system, and biophysical conditions108,109. It is also not known what proportion of these studies include biodegradable polymers, though Raimondi et al.56 noted that synthetic non-biodegradable materials had a slower release rate than biodegradable and cellulose acetate-based ones. Several field studies have been performed using biodegradable polymers110,111,112, all of which reported reductions in ammonia volatilization.

Limitations and uncertainties

Many of the limitations that we have previously discussed also pertain to controlled release or stabilized fertilizers. For instance, the commercialization of new compound products may be challenged by the risk for accumulation and toxicity, poor or weak formulations, chemical instability, and unpredictable field performance9,56. In particular, largely lacking in previous research, future efforts should identify if enhanced efficiency products provide a means to reduce agronomically or economically optimal fertilizer rates113,114, which could increase its profitability115, reduce pollution abatement costs116, and achieve other long-term goals such as producing more nutritious food and improving soil health. Furthermore, a major caveat of all meta-analyses is that protocol inconsistency in trial design and measurements can undermine the reliability and validity of the research. It is also important to assess the probability of yield gains and increases in plant nitrogen uptake in response to EEFs rather than just focusing on effect sizes33. Therefore, our understanding of EEF performance—like nanofertilizers and biofertilizers—is hindered by the lack of standard protocols, rigorous evaluations, and criteria-based systematic reviews.

Need for standard evaluations of novel fertilizers

Identifying new technologies with real potential to increase fertilizer use efficiency and meet multiple goals across diverse farming environments is contingent upon the adoption of a framework, or standard, for rigorous evaluation of product efficacy. In this review paper, we found major gaps in our understanding of novel fertilizer technology modes of action and agronomic and environmental impacts. Thus, we argue that there is a strong need for more robust agronomic and environmental evaluation of fertilizer products and practices, and we urge coordinated approaches for fertilization evaluation.

At present, a shortage of multidisciplinary data and a lack of standardization hinder the ability to form reliable conclusions about the agronomic and environmental performance of novel fertilizer technologies117. A rigorous evaluation framework of fertilizer products and nutrient management tools would achieve two goals: (1) accelerate the innovation process by obtaining reliable, cost-efficient information on the field performance of candidate innovations (e.g., products, practices, integrated solutions), and (2) robustly evaluate innovations across key regions for purposes of registration, market development, crop advisory for farmers, and environmental certification, etc. The first objective occurs earlier in the innovation process and along the laboratory to field pipeline, which may require different protocols depending upon the most relevant parameters of interest, and follows an interactive process before proceeding to a larger scale. Speed, cost and reliability are of critical importance to quickly eliminate candidates with little promise. In contrast, the second objective might include field evaluations at the end of the innovation process but may also include the re-testing of existing innovations to obtain reliable data for new purposes, such as certification based on environmental metrics. A set of experimental and data guidelines was recently developed for the evaluation of commercialized EEFs in field trials, and includes required and recommended parameters to account for location- and objective-specific considerations118. Additional standards for proof-of-concept testing in the laboratory and greenhouse are needed, such as a portfolio of independent evidence adapted to the specific product category85. The development and adoption of evaluation frameworks along the entire pipeline are needed as many novel products continue to enter the market (see patent search results for nanofertilizers in Supplementary Data 1 and biofertilizers in Supplementary Data 2), including many for which a clear mode of action or in-field efficacy is not understood.

The selection of methods for fertilizer testing—or what and how to measure—is not trivial. While standardized experiments can facilitate comparisons across treatment groups and locations, a researcher must first determine whether novel kinds of fertilizer treatments make sense within the context of divergent conditions that farmers face, including the appropriate range of nutrient addition rates that should be examined and the possibility of other growth-limiting factors119. For example, a researcher investigating the performance of an alternative fertilizer source should ideally compare the effects to a conventional source under a set of practices that optimize the performance of that conventional fertilizer, or else relative differences might be overstated120. This is further complicated because the election of fertilizer best management practices will vary depending upon the specific production environment and cropping system. Furthermore, while research tends to focus on categorical comparisons between fertilizer sources, management practices, or systems, these categories are often difficult to define and in reality response is most accurately assessed along a gradient or response curve. The scaling of research findings is another barrier to leveraging data across experiments. The laboratory-to-field pipeline is designed to incrementally demonstrate proof-of-concepts for fertilizer efficacy by scaling up with each experiment (Fig. 3). However, if the field research only involves plot-level research, the results must then be further extrapolated to a larger farm scale at which it was not measured119. This issue of scaling has important implications if the goal is to integrate novel fertilizers into a precision agricultural framework. Lastly, the publication biases against null findings might limit generalizability of meta-analyses and other attempts to synthesize data121. We strongly encourage publication of all relevant datasets as scholarly products to help overcome this bias and enable accurate data synthesis118,122.

Improve coordination of novel fertilizer research

Both food security and environmental quality depend on the judicious use of nutrients. Recent events in Sri Lanka demonstrate the vulnerability of a nation’s food production to suddenly cutting off its supply to fertilizer123, and highlight the need for solutions that protect our agronomic and environmental interests. Efforts to solve complex nutrient management problems should involve more open innovation, particularly in the pre-competitive research space and through more public-private collaboration. Mechanisms to coordinate the evaluation process can serve scientific innovation as well as industry, including producing data for new purposes in an independent and standardized manner. This process has key components, including:

-

1.

Minimum standards to compare fertilizer treatments with proper controls and accounting for random variation across space and time8,117,118,120,124.

-

2.

Properly defined treatments and explicit data and metadata requirements to facilitate coordinated research efforts and generate data that can be seamlessly combined and reported across a larger temporal and spatial extent117,118,125,126.

-

3.

Common, robust, and transparent standardized protocols127,128,129 including the selection of sampling protocols, preparation, and laboratory analyses130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140 and model implementation141,142,143.

-

4.

Deployment of statistical tools that enable the synthesis of extensive experiments across a wider geography and time144,145, such as multilevel modeling146, structural equation modeling147,148, substitution of space for time approaches149,150,151, and augmented methods152,153,154.

Limitations of this review

We acknowledge limitations in the scope and findings of this review. While this review article aims to identify key knowledge gaps and priority areas for future research on nanofertilizers, biofertilizers, and enhanced efficiency fertilizers, it is constrained by the current lack of comprehensive and systematic studies linking specific fertilizer practices to performance outcomes, such as crop yields and environmental impacts. Additionally, the lack of field studies coupled with the tremendous diversity of cropping systems and agronomic conditions presents significant uncertainty, which limits the generalizability of sparse existing evidence. This limitation can be overcome by investments in field research for evaluation purposes that we recommend here. Until then, we cannot systematically evaluate the performance of nanofertilizers, biofertilizers, and next-generation fertilizers under varied agricultural settings, emphasizing the necessity of further empirical research to substantiate these findings.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Erisman, J. W. et al. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 1, 636–639 (2008).

McArthur, J. W. & McCord, G. C. Fertilizing growth: Agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. J. Dev. Econ. 127, 133–152 (2017).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254–257 (2012).

Giller, K. E. et al. Communicating complexity: Integrated assessment of trade-offs concerning soil fertility management within African farming systems to support innovation and development. Agric. Syst. 104, 191–203 (2011).

Morris, T. F. et al. Strengths and limitations of nitrogen rate recommendations for corn and opportunities for improvement. Agron. J. 110, 1–37 (2018).

Schut, A. G. T. & Giller, K. E. Soil-based, field-specific fertilizer recommendations are a pipe-dream. Geoderma 380, 114680 (2020).

Fixen, P. E. A brief account of the genesis of 4R nutrient stewardship. Agron. J. 112, 4511–4518 (2020).

Maaz, T. M. et al. Meta-analysis of yield and nitrous oxide outcomes for nitrogen management in agriculture. Glob. Chang Biol. 27, 2343–2360 (2021).

Lam, S. K. et al. Next-generation enhanced-efficiency fertilizers for sustained food security. Nat. Food 3, 575–580 (2022).

Hatfield, J. L. & Venterea, R. T. Enhanced efficiency fertilizers: A multi-site comparison of the effects on nitrous oxide emissions and agronomic performance. Agron. J. 106, 679–680 (2014).

Snyder, C. S., Bruulsema, T. W., Jensen, T. L. & Fixen, P. E. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 133, 247–266 (2009).

Janke, C. K., Moody, P. & Bell, M. J. Three-dimensional dynamics of nitrogen from banded enhanced efficiency fertilizers. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 118, 227–247 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Enhanced-efficiency fertilizers are not a panacea for resolving the nitrogen problem. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, e511–e521 (2018).

Drury, C. F. et al. Combining urease and nitrification inhibitors with incorporation reduces ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions and increases corn yields. J. Environ. Qual. 46, 939–949 (2017).

Woodley, A. L. et al. Ammonia volatilization, nitrous oxide emissions, and corn yields as influenced by nitrogen placement and enhanced efficiency fertilizers. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 84, 1327–1341 (2020).

Dobermann, A. et al. Responsible plant nutrition: A new paradigm to support food system transformation. Glob. Food Sec. 33, 100636 (2022).

Trenkel, M. E. Slow- and Controlled-Release and Stabilized Fertilizers: An Option for Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency in Agriculture. (IFA, International fertilizer industry Association, 2010).

Rindt, D. W., Blouin, G. M. & Getsinger, J. G. Sulfur Coating on Nitrogen Fertilizer to Reduce Dissolution Rate. J. Agric Food Chem. 16, 773–778 (1968).

Lunt, O. R. & Oertli, J. J. Controlled release of fertilizer minerals by incapsulating membranes: ii. efficiency of recovery, influence of soil moisture, mode of application, and other considerations related to use. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 26, 584–587 (1962).

Oertli, J. J. & Lunt, O. R. Controlled release of fertilizer minerals by incapsulating membranes: I. Factors influencing the rate of release. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 26, 579–583 (1962).

Goring, C. A. I. Control of nitrification by 2-Chloro-6-(Trichloro-Methyl) Pyridine. Soil Sci. 93, 211–218 (1962).

Subbarao, G. et al. Scope and strategies for regulation of nitrification in agricultural systems - Challenges and opportunities. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 25, 303–335 (2006).

IFA. IFA’s Fertilizer Terminology. (2020).

Shaviv, A. & Mikkelsen, R. L. Controlled-release fertilizers to increase efficiency of nutrient use and minimize environmental degradation - A review. Fert. Res. 35, 1–12 (1993).

Hauck, R. D. Slow-release and bioinhibitor-amended nitrogen fertilizers. Fertilizer Technology and Use 293–322 https://doi.org/10.2136/1985.FERTILIZERTECHNOLOGY.C8 (2015).

Amberger, A. Research on dicyandiamide as a nitrification inhibitor and future outlook. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 20, 1933–1955 (1989).

Linquist, B. A., Liu, L., van Kessel, C. & van Groenigen, K. J. Enhanced efficiency nitrogen fertilizers for rice systems: Meta-analysis of yield and nitrogen uptake. Field Crops Res. 154, 246–254 (2013).

Zhang, W. et al. The effects of controlled release urea on maize productivity and reactive nitrogen losses: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 246, 559–565 (2019).

Quemada, M., Baranski, M., Nobel-de Lange, M. N. J., Vallejo, A. & Cooper, J. M. Meta-analysis of strategies to control nitrate leaching in irrigated agricultural systems and their effects on crop yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 174, 1–10 (2013).

Abalos, D., Jeffery, S., Sanz-Cobena, A., Guardia, G. & Vallejo, A. Meta-analysis of the effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 189, 136–144 (2014).

Thapa, R., Chatterjee, A., Awale, R., McGranahan, D. A. & Daigh, A. Effect of enhanced efficiency fertilizers on nitrous oxide emissions and crop yields: a meta-analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 80, 1121–1134 (2016).

Qiao, C. et al. How inhibiting nitrification affects nitrogen cycle and reduces environmental impacts of anthropogenic nitrogen input. Glob. Chang Biol. 21, 1249–1257 (2015).

Burzaco, J. P., Ciampitti, I. A. & Vyn, T. J. Nitrapyrin impacts on maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency with spring-applied nitrogen: Field studies vs. meta-analysis comparison. Agron. J. 106, 753–760 (2014).

Silva, A. G. B., Sequeira, C. H., Sermarini, R. A. & Otto, R. Urease inhibitor NBPT on ammonia volatilization and crop productivity: A meta-analysis. Agron. J. 109, 1–13 (2017).

Akiyama, H., Yan, X. & Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: Meta-analysis. Glob. Chang Biol. 16, 1837–1846 (2010).

Fan, D. et al. Global evaluation of inhibitor impacts on ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Glob. Chang Biol. 28, 5121–5141 (2022).

Sha, Z. et al. Effect of N stabilizers on fertilizer-N fate in the soil-crop system: A meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst. Environ. 290, 106763 (2020).

Lam, S. K., Suter, H., Mosier, A. R. & Chen, D. Using nitrification inhibitors to mitigate agricultural N2O emission: a double-edged sword?. Glob. Chang. Biol. 23, 485–489 (2017).

Pan, B., Lam, S. K., Mosier, A., Luo, Y. & Chen, D. Ammonia volatilization from synthetic fertilizers and its mitigation strategies: A global synthesis. Agric Ecosyst. Environ. 232, 283–289 (2016).

Soares, J. R. et al. Mitigation of nitrous oxide emissions in grazing systems through nitrification inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 125, 359–377 (2023).

Grados, D. et al. Synthesizing the evidence of nitrous oxide mitigation practices in agroecosystems. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 114024 (2022).

Young, M. D., Ros, G. H. & de Vries, W. Impacts of agronomic measures on crop, soil, and environmental indicators: A review and synthesis of meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst. Environ. 319, 107551 (2021).

Timilsena, Y. P. et al. Enhanced efficiency fertilisers: A review of formulation and nutrient release patterns. J. Sci. Food Agric 95, 1131–1142 (2015).

Trenkel, M. E. Improving Fertilizer Use Efficiency Controlled-Release and Stabilized Fertilizers in Agriculture. (International Fertilizer Industry Association, Paris, 1997).

Chen, J. et al. Environmentally friendly fertilizers: A review of materials used and their effects on the environment. Sci. Total Env. 613–614, 829–839 (2018).

FAO. Food Safety Implications from the Use of Environmental Inhibitors in Agrifood Systems. Food Safety and Quality Series, No. 24. Food safety implications from the use of environmental inhibitors in agrifood systems https://doi.org/10.4060/cc8647en (2023).

Mastronardi, E., Tsae, P., Zhang, X., Monreal, C. & DeRosa, M. C. Strategic role of nanotechnology in fertilizers: Potential and limitations. in Nanotechnologies in Food and Agriculture https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14024-7_2 (2015).

Zheng, B. et al. Mechanochemical synthesis of zinc borate for use as a dual-release B fertilizer. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 9, 15995–16004 (2021).

Dimkpa, C. O. & Bindraban, P. S. Nanofertilizers: New products for the industry?. J. Agric Food Chem. 66, 6462–6473 (2018).

Derosa, M. C., Monreal, C., Schnitzer, M., Walsh, R. & Sultan, Y. Nanotechnology in fertilizers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 91 (2010).

Husted, S. et al. What is missing to advance foliar fertilization using nanotechnology?. Trends Plant Sci. 28, 90–105 (2023).

Marchiol, L., Iafisco, M., Fellet, G. & Adamiano, A. Nanotechnology support the next agricultural revolution: Perspectives to enhancement of nutrient use efficiency. Adv. Agron. 161, 27–116 (2020).

Yadav, A., Yadav, K. & Abd-Elsalam, K. Nanofertilizers: Types, delivery and advantages in agricultural. Sustain. Agrochem. 2, 296–336 (2023).

White, J. C. & Gardea-Torresdey, J. Achieving food security through the very small. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 627–629 (2018).

Kah, M., Kookana, R. S., Gogos, A. & Bucheli, T. D. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018 13:8 13, 677–684 (2018).

Raimondi, G., Maucieri, C., Toffanin, A., Renella, G. & Borin, M. Smart fertilizers: What should we mean and where should we go? Ital. J. Agron. 16, 1794 (2021).

Quintarelli, V. et al. Advances in Nanotechnology for Sustainable Agriculture: A Review of Climate Change Mitigation. Sustainability (Switzerland). 16, 9280 (2024).

Nongbet, A. et al. Nanofertilizers: A smart and sustainable attribute to modern agriculture. Plants 11, 2587 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Ammonia volatilization mitigation in crop farming: A review of fertilizer amendment technologies and mechanisms. Chemosphere 303, 134944 (2022).

Pereira, E. I. et al. Novel slow-release nanocomposite nitrogen fertilizers: The impact of polymers on nanocomposite properties and function. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 3717–3725 (2015).

Pohshna, C. & Mailapalli, D. R. Engineered urea-doped hydroxyapatite nanomaterials as nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers for rice. Acs Agric. Sci. Technol. 2, 100–112 (2022).

Alimohammadi, M., Panahpour, E. & Naseri, A. Assessing the effects of urea and nano-nitrogen chelate fertilizers on sugarcane yield and dynamic of nitrate in soil. Fert. Soil Amend. 66, 352–359 (2020).

Hofmann, T. et al. Technology readiness and overcoming barriers to sustainably implement nanotechnology-enabled plant agriculture. Nat. Food 1, 416–425 (2020).

White, J. C. & Gardea-Torresdey, J. Nanoscale agrochemicals for crop health: A key line of attack in the battle for global food security. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 13413–13416 (2021).

Kumar, N., Samota, S. R., Venkatesh, K. & Tripathi, S. C. Global trends in use of nano-fertilizers for crop production: Advantages and constraints – A review. Soil Tillage Res. 228, 105645 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Approaches to nanoparticle labeling: a review of fluorescent, radiological, and metallic. Tech. Environ. Health 1, 75–89 (2023).

Kumar, Y., Raliya, R., Singh, T. & Tiwari, K. Nano fertilizers for sustainable crop production, higher nutrient use efficiency and enhanced profitability. Indian J. Fert. 17, 1206–1214 (2021).

Kumar, Y. et al. Nanofertilizers for increasing nutrient use efficiency, yield and economic returns in important winter season crops of Uttar Pradesh. Indian J. Fert 16, 772–786 (2020).

Frank, M. & Husted, S. Is India’s largest fertilizer manufacturer misleading farmers and society using dubious plant and soil science? Plant Soil https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-06191-4 (2023).

Sikka, R., Kalia, A., Ahuja, R., Sidhu, S. K. & Chaitra, P. Substitution of soil urea fertilization to foliar nano urea fertilization decreases growth and yield of rice and wheat. Plant Soil https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-07157-w (2025).

Rico, C. M., Majumdar, S., Duarte-Gardea, M., Peralta-Videa, J. R. & Gardea-Torresdey, J. L. Interaction of nanoparticles with edible plants and their possible implications in the food chain. J. Agric Food Chem. 59, 3485–3498 (2011).

Nogueira, V. et al. Impact of organic and inorganic nanomaterials in the soil microbial community structure. Sci. Total Environ. 424, 344–350 (2012).

Husted, S. et al. Nanotechnology Papers with an Agricultural Focus Are Too Frequently Published with a Superficial Understanding of Basic Plant and Soil Science. ACS Nano. 18, 33767–33770 (2024).

Mitter, E. K., Tosi, M., Obregon, D., Dunfield, K. E. & Germida, J. J. Rethinking crop nutrition in times of modern microbiology: Innovative biofertilizer technologies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 606815 (2021).

Yakhin, O. I., Lubyanov, A. A., Yakhin, I. A. & Brown, P. H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 7, (2017).

du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 196, 3–14 (2015).

H. R. 7752. 117th Congress (2021-2022): Plant Biostimulant Act of 2022. (House of Representatives, Washington, D.C., 2022).

O’Callaghan, M., Ballard, R. A. & Wright, D. Soil microbial inoculants for sustainable agriculture: Limitations and opportunities. Soil Use Manag 38, 1340–1369 (2022).

Menéndez, E. & Paço, A. Is the application of plant probiotic bacterial consortia always beneficial for plants? Exploring synergies between rhizobial and non-rhizobial bacteria and their effects on agro-economically valuable crops. Life 10, 24 (2020).

Turhan, E. Ü., Erginkaya, Z., Korukluoğlu, M. & Konuray, G. Beneficial biofilm applications in food and agricultural industry. in Health and Safety Aspects of Food Processing Technologies (eds. Malik, A., Erginkaya, Z. & Erten, H.) 445–469 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24903-8_15.

Vassileva, M., Flor-Peregrin, E., Malusá, E. & Vassilev, N. Towards better understanding of the interactions and efficient application of plant beneficial prebiotics, probiotics, postbiotics and synbiotics. Front Plant Sci. 11, 1068 (2020).

Koo, B. J., Adriano, D. C., Bolan, N. S. & Barton, C. D. Root Exudates and Microorganisms. in Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment vol. 4 421–428 (Elsevier Inc., 2004).

Schütz, L. et al. Improving crop yield and nutrient use efficiency via biofertilization−A global meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2204 (2018).

Barbosa, J. Z. et al. Meta-analysis of maize responses to Azospirillum brasilense inoculation in Brazil: Benefits and lessons to improve inoculation efficiency. Appl. Soil Ecol. 170, 104276 (2022).

Giller, K. E., James, E. K., Ardley, J. & Unkovich, M. J. Science losing its way: examples from the realm of microbial N2-fixation in cereals and other non-legumes. Plant Soil https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-07001-1 (2024).

Hart, M. M., Antunes, P. M., Chaudhary, V. B. & Abbott, L. K. Fungal inoculants in the field: Is the reward greater than the risk?. Funct. Ecol. 32, 126–135 (2018).

Kaminsky, L. M., Trexler, R. V., Malik, R. J., Hockett, K. L. & Bell, T. H. The inherent conflicts in developing soil microbial inoculants. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 140–151 (2019).

Compant, S., Samad, A., Faist, H. & Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 19, 29–37 (2019).

Gay, J. D. et al. Climate mitigation potential and soil microbial response of cyanobacteria-fertilized bioenergy crops in a cool semi-arid cropland. GCB Bioenergy 14, 1303–1320 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from tea field soil using bioaugmentation with a trichoderma viride biofertilizer. Sci. World J. 2014, 793752 (2014).

Tao, R., Wakelin, S. A., Liang, Y., Hu, B. & Chu, G. Nitrous oxide emission and denitrifier communities in drip-irrigated calcareous soil as affected by chemical and organic fertilizers. Sci. Total Environ. 612, 739–749 (2018).

Shrestha, R. C. et al. The effects of microalgae-based fertilization of wheat on yield, soil microbiome and nitrogen oxides emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151320 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Manipulation of nitrogen leaching from tea field soil using a Trichoderma viride biofertilizer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 27833–27842 (2017).

Sun, B. et al. Application of biofertilizer containing Bacillus subtilis reduced the nitrogen loss in agricultural soil. Soil Biol. Biochem 148, 107911 (2020).

Martínez-Hidalgo, P., Maymon, M., Pule-Meulenberg, F. & Hirsch, A. M. Engineering root microbiomes for healthier crops and soils using beneficial, environmentally safe bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol 65, 91–104 (2019).

Kassem, I., Ablouh, E. H., El Bouchtaoui, F. Z., Jaouahar, M. & El Achaby, M. Polymer coated slow/ controlled release granular fertilizers: Fundamentals and research trends. Prog. Mater. Sci. 144, 101269 (2024).

Fu, J., Wang, C., Chen, X., Huang, Z. & Chen, D. Classification research and types of slow controlled release fertilizers (SRFs) used-a review. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 49, 2219–2230 (2018).

Campos, E. V. R., de Oliveira, J. L., Fraceto, L. F. & Singh, B. Polysaccharides as safer release systems for agrochemicals. Agron. Sustain Dev. 35, 47–66 (2015).

Skrzypczak, D. et al. Smart fertilizers-toward implementation in practice. in Smart Agrochemicals for Sustainable Agriculture (eds. Chojnacka, K. & Saeid, A.) 81–102 (Elsevier, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817036-6.00010-8.

Mim, J. J. et al. Towards smart agriculture through nano-fertilizer-A review. Mater. Today Sustain. 30, 101100 (2025).

Zhang, X., Chabot, D., Sultan, Y., Monreal, C. & Derosa, M. C. Target-molecule-triggered rupture of aptamer-encapsulated polyelectrolyte microcapsules. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 5, 5500–5507 (2013).

Mastronardi, E., Monreal, C. & DeRosa, M. C. Personalized Medicine for Crops? Opportunities for the Application of Molecular Recognition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 6457–6461 (2018).

Mastronardi, E., Cyr, K., Monreal, C. M. & Derosa, M. C. Selection of DNA aptamers for root exudate l -Serine using multiple selection strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 4294–4306 (2021).

Islam, Z. F., Cherepanov, P. V. & Hu, H. W. Engineering biodegradable coatings for sustainable fertilisers. Microbiol. Aust. 44, 9–12 (2023).

Singh, S. et al. Smart fertilizer technologies: An environmental impact assessment for sustainable agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 100504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atech.2024.100504 (2024).

Mandal, S. et al. Biostimulants and environmental stress mitigation in crops: A novel and emerging approach for agricultural sustainability under climate change. Environ. Res. 233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116357 (2023).

Arora, P. K. et al. Next-generation fertilizers: the impact of bionanofertilizers on sustainable agriculture. Microb. Cell Fact. 23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-024-02528-5 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Exploring optimal nitrogen management practices within site-specific ecological and socioeconomic conditions. J. Clean Prod. 241, 118295 (2019).

Sha, Z. et al. Ammonia loss potential and mitigation options in a wheat-maize rotation system in the North China Plain: A data synthesis and field evaluation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 352, 108512 (2023).

Santos, C. F. et al. Dual functional coatings for urea to reduce ammonia volatilization and improve nutrients use efficiency in a Brazilian corn crop system. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21, 1591–1609 (2021).

Santos, C. F. et al. Environmentally friendly urea produced from the association of N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide with biodegradable polymer coating obtained from a soybean processing byproduct. J. Clean. Prod. 276, 123014 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Reducing nitrogen losses through ammonia volatilization and surface runoff to improve apparent nitrogen recovery of double cropping of late rice using controlled release urea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 11722–11733 (2017).

Rose, T. J., Wood, R. H., Rose, M. T. & Van Zwieten, L. A re-evaluation of the agronomic effectiveness of the nitrification inhibitors DCD and DMPP and the urease inhibitor NBPT. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 252, 69–73 (2018).

Su, N. et al. Effectiveness of a 10-year continuous reduction of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer on production, nitrogen loss and utilization of double-cropping rice. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168857 (2024).

Thompson, M., Dowie, J., Wright, C. & Curro, A. An Economic Evaluation Of Controlled Release And Nitrification Inhibiting Fertilisers In The Burdekin. Proc. Aust. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 39, 274–279 (2017).

Doole, G. J. & Paragahawewa, U. H. Profitability of nitrification inhibitors for abatement of nitrate leaching on a representative dairy farm in the waikato region of New Zealand. Water ((Switz.)) 3, 1031–1049 (2011).

Eagle, A. J. et al. Meta-analysis constrained by data: Recommendations to improve relevance of nutrient management research. Agron. J. 109, 2441–2449 (2017).

Lyons, S. E. et al. Field trial guidelines for evaluating enhanced efficiency fertilizers. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20787 (2024).

Krupnik, T. J. et al. Does size matter? A critical review of meta-analysis in agronomy. Exp. Agric. 55, 200–229 (2019).

Cassman, K. Editorial response by Kenneth Cassman: Can organic agriculture feed the world-science to the rescue?. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 22, 83–84 (2007).

Philibert, A., Loyce, C. & Makowski, D. Assessment of the quality of meta-analysis in agronomy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 148, 72–82 (2012).

Walters, W. H. Data journals: Incentivizing data access and documentation within the scholarly communication system. Insights: UKSG J. 33 (2020).

Jeevika, W., Athula, S. & Suresh, B. Reforming fertilizer import policies for sustainable intensification of agricultural systems in Sri Lanka: Is there a policy failure? https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=reforming+fertilizer+import+policies+weerahewa&btnG= (2021).

Bolinder, M. A. et al. The effect of crop residues, cover crops, manures and nitrogen fertilization on soil organic carbon changes in agroecosystems: a synthesis of reviews. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 25, 929–952 (2020).

Brouder, S. et al. Enabling open-source data networks in public agricultural research. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology Issue Paper. QTA2019-1, 20 pp. (2019).

Slaton, N. A. et al. Minimum dataset and metadata guidelines for soil-test correlation and calibration research. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 86, 19–33 (2022).

Kladivko, E. J. et al. Standardized research protocols enable transdisciplinary research of climate variation impacts in corn production systems. J. Soil Water Conserv. 69, 532–543 (2014).

Herzmann, D. E., Abendroth, L. J. & Bunderson, L. D. Data management approach to multidisciplinary agricultural research and syntheses. J. Soil Water Conserv. 69, 180A–185A (2014).

Haddaway, N. R. & Rytwinski, T. Meta-analysis is not an exact science: Call for guidance on quantitative synthesis decisions. Environ. Int. 114, 357–359 (2018).

Bergström, L. Nitrate leaching and drainage from annual and perennial crops in tile-drained plots and lysimeters. J. Environ. Qual. 16, 11–18 (1987).

Pumpanen, J. et al. Comparison of different chamber techniques for measuring soil CO2 efflux. Agric. Meteorol. 123, 159–176 (2004).

Grace, P. R. et al. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Considerations for automated flux measurement. J. Environ. Qual. 49, 1126–1140 (2020).

Flesch, T. K. et al. Micrometeorological measurements reveal large nitrous oxide losses during spring thaw in Alberta. Atmosphere 9, 128 (2018).

Zotarelli, L., Scholberg, J. M., Dukes, M. D. & Muñoz-Carpena, R. Monitoring of nitrate leaching in sandy soils. J. Environ. Qual. 36, 953–962 (2007).

Wang, Q. et al. Comparison of lysimeters and porous ceramic cups for measuring nitrate leaching in different soil types. N.Z. J. Agric. Res. 55, 333–345 (2012).

Snyder, G. H. Nitrogen Losses by Leaching and Runoff: Methods and Conclusions. Nitrogen Economy in Tropical Soils (Springer, Dordrecht, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1706-4_41.

Ramos, C., Kücke, M. & Kücke, M. A review of methods for nitrate leaching measurement. Acta Hortic. 563, 259–266 (2001).

Vogeler, I. et al. Nitrate leaching from suction cup data: Influence of method of drainage calculation and concentration interpolation. J. Environ. Qual. 49, 440–449 (2020).

Cui, M., Zeng, L., Qin, W. & Feng, J. Measures for reducing nitrate leaching in orchards: A review. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114553 (2020).

Xu, D. M. & Fu, R. B. A comparative assessment of metal bioavailability using various universal extractants for smelter contaminated soils: Novel insights from mineralogy analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 367, 132936 (2022).

Basso, B. et al. Environmental and economic evaluation of N fertilizer rates in a maize crop in Italy: A spatial and temporal analysis using crop models. Biosyst. Eng. 113, 103–111 (2012).

Kim, T. et al. Quantifying nitrogen loss hotspots and mitigation potential for individual fields in the US Corn Belt with a metamodeling approach. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, (2021).

Shi, X., Li, X., Guo, C., Feng, P. & Hu, K. Modeling ammonia volatilization following urea and controlled-release urea application to paddy fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 196, 106888 (2022).

Lorenz, A. J. Resource allocation for maximizing prediction accuracy and genetic gain of genomic selection in plant breeding: A simulation experiment. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 3, 481–491 (2013).

Castle, S. C. et al. Impacts of sampling design on estimates of microbial community diversity and composition in agricultural soils. Micro. Ecol. 78, 753–763 (2019).

Qian, S. S., Cuffney, T. F., Alameddine, I., Mcmahon, G. & Reckhow, K. H. On the application of multilevel modeling in environmental and ecological studies. Ecology 91, 355–361 (2010).

Wade, J. et al. Improved soil biological health increases corn grain yield in N fertilized systems across the Corn Belt. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

Smith, R. G. et al. Structural equation modeling facilitates transdisciplinary research on agriculture and climate change. Crop Sci. 54, 475–483 (2014).

Li, X. et al. A new Rothamsted long-term field experiment for the twenty-first century: principles and practice. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43, 60 (2023).

Pickett, S. T. A. Space-for-time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. in Long-Term Studies in Ecology (ed. Likens, G. E.) 110–135 (Springer, New York, NY, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-7358-6_5.

Blois, J. L., Williams, J. W., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Jackson, S. T. & Ferrier, S. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9374–9379 (2013).

Neyhart, J. L., Gutierrez, L. & Smith, K. P. Optimizing the choice of test locations for multitrait genotypic evaluation. Crop Sci. 62, 192–202 (2022).

Zystro, J., Colley, M. & Dawson, J. Alternative experimental designs for plant breeding. in Plant Breeding Reviews (ed. Goldman, I.) vol. 42 87–117 (John Wiley and Sons Inc, 2019).

Federer, W. T. & Raghavarao, D. On augmented designs. Biometrics 31, 29–35 (1975).

Saggar, S. et al. Quantification of reductions in ammonia emissions from fertiliser urea and animal urine in grazed pastures with urease inhibitors for agriculture inventory: New Zealand as a case study. Sci. Total Environ. 465, 136–146 (2013).

Dimkpa, C. O., Fugice, J., Singh, U. & Lewis, T. D. Development of fertilizers for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency – Trends and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 139113 (2020).

Han, Z., Walter, M. T. & Drinkwater, L. E. N2O emissions from grain cropping systems: a meta-analysis of the impacts of fertilizer-based and ecologically-based nutrient management strategies. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst 107, 335–355 (2017).

Pan, Z. et al. Global impact of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers on vegetable productivity and reactive nitrogen losses. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 172016 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Trade-offs between agronomic and environmental benefits: A comparison of inhibitors with controlled release fertilizers in global maize systems. Field Crops Res. 323, 109768 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Foundation for Food & Agricultural Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. and A.D. conceptualized the idea. A.T. led and administered the project. T.M., A.D., and S.L. conducted literature searches and analysis. T.M. developed figures. T.M. prepared the orginal draft. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maaz, T.M., Dobermann, A., Lyons, S.E. et al. Review of research and innovation on novel fertilizers for crop nutrition. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 25 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00066-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00066-0