Abstract

Nutrient balance is critical for sustainable land management, yet information scarcity hampers its systematic evaluation of trade-offs among alternate land uses. We employed a detailed regional nutrient dataset collected from 70 monitoring sites over 16 years to conduct a comprehensive analysis of yields, nutrient balances and greenhouse gas emissions associated with different land management practices in Lower Saxony, Germany. The information was used to develop land use transformation scenarios while assessing their impacts on regional nutrient balances and emissions. Our analysis demonstrated that organic farming exhibited lower nutrient surpluses but also lower yields compared to conventional systems, while grazing systems showed the highest nutrient outputs. A comparison with other regional studies highlights the importance of unique combinations of climate, soil, management practices, and socioeconomic settings in developing sustainable land management strategies – a global perspective, while useful in setting goals, may not capture local needs specific to this combination of factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agricultural activities span half of Earth’s habitable land, consuming 70% of global freshwater resources1,2 with global food production contributing 26% of greenhouse gas emissions3,4. Feeding the rapidly growing world population would require expansion and adjustment of agricultural practices, primarily to ensure sustainable land management (SLM), by meeting human needs while maintaining long-term productivity and environmental preservation5,6. SLM attempts to reconcile competing environmental and socio-economic factors7 such as supplying plant nutrient needs with minimal leaching and other unintended fluxes.

Many practical approaches support organic farming as a potential solution to escalating food demands while maintaining environmental sustainability8,9. However, current research shows a wide range of yield disparities between organic and conventional farming methods, influenced by regional variations and agricultural intensity. These yield differences have ranged10,11 from 5% to 60%, with an average variance12 of 19-25%. Despite growing interest in organic farming, its adaptation is hampered by potential yield losses and complex environmental impacts that are local and context-dependent. Recent studies further emphasize the critical role of regional variability in nutrient balances and environmental impacts13,14. These findings reinforce the notion that globally standardized emission factors or nutrient management strategies may not accurately reflect local realities. The environmental impact of different agricultural practices, particularly with respect to nitrogen balances, remains a challenge. Modelling approaches that evaluate these farming practices often rely on numerous assumptions and limited datasets, making it difficult to assess their true long-term sustainability under different land-use scenarios10,15,16. To advance sustainable agricultural management, research must provide sufficient information to address the dual challenge of balancing food production with environmental protection. This includes developing methodologies that integrate the complexity of regional conditions, diverse land-use practices, and environmental regulations, as well as ensuring the availability of long-term, comprehensive datasets17,18,19,20.

This study addresses the issue of sustainable nutrient balance at a regional scale, considering a variety of land uses and management, using a unique and detailed dataset sourced from Lower Saxony, Germany. Our research encompasses 16 years of fertilizer applications and the resulting nutrient outputs across 70 monitoring sites. Additionally, we examine potential changes in carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas emissions stemming from agricultural and forest sectors over the same time period. To provide a comprehensive analysis, we extrapolate these observations to consider various end-member land use and management transformation scenarios, representing hypothetical, extreme cases at the bounds of possible changes. We also evaluate their effects on nutrient balances, food production, and potential greenhouse gas emissions as integral components of SLM.

Our empirical study offers a robust perspective on the distinct impacts of organic farming, conventional farming, and grazing on both nutrient balances and environmental dynamics within a fully developed, well-managed, homogeneous and environmentally regulated agricultural region. This allows for evaluating whether globally accessible comprehensive datasets are sufficient to develop a universal approach to understanding the factors influencing nutrient balance and its environmental impacts, which are crucial for SLM. Alternatively, it raises the question of whether a regional perspective, which accounts for diverse local contexts, is more effective than global efforts that homogenize them. Therefore, the objective of this study is to assess how different land use types (i.e., conventional farming, organic farming, and grazing), impact nutrient balances and greenhouse gas emissions in a region with relatively homogeneous environmental and regulatory conditions. By combining empirical measurements across 70 long-term monitoring sites with region-specific scenario analysis, we explore how even subtle variations in land management can influence sustainability outcomes, providing insights that are often overlooked in broader-scale assessments.

Results

Nutrient balance calculations

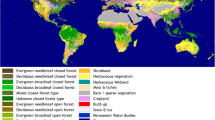

Lower Saxony covers an area21 of 47.613 km2, with arable land making up 44%, grazing areas 20% and forests 20%. The regional climate is moderate with average temperatures ranging from 8 to 10 °C annually and precipitation varies between 600 and 1000 mm per year22 (for further details, refer to Fig. S1 of the supplementary materials, climatic conditions). Using data from monitoring stations23 as shown in Fig. 1(a), we present averages of the annual inputs and outputs of macronutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium across different land management practices from 2001 to 2016 (Fig. 1b; for further details, refer to supplementary materials, annual data analysis across monitoring locations). The monitoring locations were evenly distributed to proportionally represent each land management type. The primary differences in fertilizer input between grazing, conventional farming and organic farming are in nitrogen sources (Fig. 1b). Grazing derives 46% of nitrogen from organic sources, while conventional farming derives 37% and organic farming relies entirely on organic sources of fertilizers (55%) and legume nitrogen fixation (45%). Additionally, grazing and conventional farming systems rely heavily on organic fertilizers to supply phosphorus and potassium, with grazing systems sourcing 85% of phosphorus and 90% of potassium organically. Interestingly, even for conventional farming in Lower Saxony, 64% of the phosphorus and 67% of the potassium come from organic sources. The higher tendency towards organic sources in grazing systems is largely due to the substantial input of manure in pastures and meadows. However, both grazing and conventional farming exhibit significantly higher nutrient outputs compared to organic farming, as illustrated in Fig. 1(b). Notably, grazing systems surpass conventional systems in the nitrogen and potassium output. Although it remains unclear what fraction of the macronutrients directly contributes to yields due to losses related to climatic and hydrogeological conditions, evidence suggests that conditions are relatively uniform across the study area. Organic farming is typically situated on the most fertile lands and is expected to experience lower nutrient losses compared to grazing, which is often designated to less fertile and sandy soils.

a Map of Lower Saxony displaying land use categories21 and the locations of 70 monitoring stations, each annotated with their respective land management practices (grazing, conventional farming or organic farming). White areas on the map fall outside the classified land use categories. b Mean annual inputs of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium from organic and mineral fertilization (source) and corresponding nutrient removals through yield (sink), per hectare, for each land management practice across all monitoring stations over the period 2001–2016.

Nutrient balance calculations, based on Fig. 1(b), reveal distinct patterns. Organic farming, with significantly lower nitrogen and phosphorus surpluses, seems to offer lower detrimental environmental impacts (e.g., in reducing the risk of eutrophication). Additionally, unlike grazing and conventional farming, organic farming reduces the risk of productivity loss due to potassium depletion. Furthermore, the transformation scenarios indicate that organic farming, despite its lower yields, contributes to improved nutrient balance and may help mitigate long-term soil degradation, particularly related to potassium. Notably, the land newly designated to grazing in the scenario analysis exhibits higher fertility compared to currently grazed areas, suggesting that soil quality distribution plays a role in scenario outcomes. Data enables comparison of crop yields for wheat and rye that are common for organic and conventional farming. Within conventional farming, the mean annual yield per hectare for wheat and rye stands at 8.54 and 7.52 tons/ha (dry matter), respectively. In contrast, organic farming annually yields 5.40 and 3.35 tons/ha for wheat and rye, respectively. The results show persistently lower crop yields (37% and 56% for Rye and Wheat) in organic farming compared to conventional farming consistent with other analyses11,24.

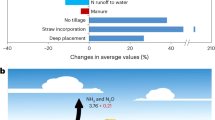

Regional nutrient balance for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, noted as current, is presented in Fig. 2(a) based on the data in Fig. 1(b). Additionally, Fig. 2(a) presents hypothetical effects of different end-member land use and management conversion scenarios from 2001 to 2016: exclusive grazing (all grazing), a proportional mix of conventional and organic farming (all farming), exclusive organic farming (all organic farming) and exclusive conventional farming (all conventional farming).

a Mean annual nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium balances across various end-member land transformation scenarios, as well as under current land management, for the entire study area, expressed in megatons. b Mean annual CO2-equivalent (CO2e) greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, CH4, and N2O) from grazing, farming and forested areas41,42, along with CO2e emissions under different end-member land use and management transformation scenarios, expressed in million tonnes per year.

Potential greenhouse gas emissions

Figure 2(b) shows average carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) greenhouse gas emissions for the entire region under current conditions and specific land uses, along with projections for scenarios where all land is dedicated to grazing, farming or forests (all forest). For comparison of different land uses, we examined potential greenhouse gas emissions11 (see Fig. 2(b)) for hypothetical transitions. The transition among land uses can alter soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks, potentially increasing or releasing stored carbon and nutrients. To capture these effects more comprehensively, we applied sequestration rates derived from different studies25,26,27,28,29,30. Considering conversion of the land solely to grazing results in the highest detrimental emissions with ca. 25 Mt CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) per year from 2001 to 2016, approximately equal to four times of the current emissions from grazing lands. The all farming scenario exhibits approximately four times greater emissions than current practices. While reverting all land to forests results in the lowest emissions with significant consequences for food security and socio-economic activities. The study region (Lower Saxony) shows modest annual CO2 emissions between 2001 and 2016, suggesting a lower environmental impact compared to global observations31. However, even this impact could be reduced via improved land management initiatives among other activities.

Discussion

The study shows that regional nutrient balance and greenhouse gas emissions are highly sensitive to local conditions, particularly land use and management practices. Our analysis in Lower Saxony demonstrates that even under relatively uniform climatic and regulatory settings, choices regarding fertilizer application rates and land use (e.g., grazing, organic farming, or conventional farming) can significantly affect both nutrient surpluses and net GHG emissions. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive understanding of nutrient balance regime for achieving SLM (see Lower Saxony SLM32 summary, supplementary materials), when many factors, including soil fertility, management practices, and socio-economic drivers, interact at regional scales.

Despite the region’s homogeneous climate, we observed distinct nutrient imbalances arising from different practices. This illustrates the complexity involved in determining nutrient balance within a single region, where numerous influencing parameters are constant, let alone those affected by multiple changing factors. While our long-term dataset (2001–2016) enables robust analysis of these interactions, it is important to note that it may not fully reflect more recent shifts in agricultural practices. Nonetheless, comparisons with more recent studies13,14 confirm that the general patterns of nutrient surpluses and the importance of local management differences remain consistent. The importance of regional nuances in shaping nutrient balances is evident not only in studying a single region like Lower Saxony but also when comparing different regions across the world. There are regions such as the Vistula River basin in Poland33 with conditions similar to Lower Saxony, where land use and management trade-offs significantly influence nutrient balance.

In Lower Saxony, nutrient imbalance (deficit or surplus) leads to the degradation of limited quality soil or the contamination of interconnected surface water canals, which are crucial for neighbouring agricultural activities and the preservation of diverse ecological functions. Moreover, recent large-scale assessments in Lower Saxony demonstrate that changes in agricultural practices can strongly alter soil organic carbon levels and organic-matter-related nitrogen fluxes, highlighting the impact of region-specific management on nutrient balances34. Similarly, Don et al.35 found that farmland conversion to bioenergy production substantially affects both greenhouse gas balances and soil carbon stocks, showing the complex interplay between land-use decisions and environmental outcomes in Germany.

GHG emissions likewise vary notably by land use. Converting all land to grazing led to the highest annual average of ~25 Mt CO₂e, whereas returning it to forested areas significantly reduced emissions. However, such drastic changes would inevitably compromise food security or involve major socio-economic shifts. In contrast, intermediate scenarios, such as emphasizing organic practices or moderately expanding forestry, can mitigate emissions while still maintaining some level of production. We acknowledge that in real-world organic farming systems, grassland and grazing are integral parts of nutrient management cycles, supporting closed-loop systems. Our separation of grazing as an independent category was a modeling decision aimed at isolating its specific effects on nutrient balances and emissions. While this abstraction simplifies the complexity of farm structures, it allows a clearer examination of the impacts associated with different dominant land uses. Future scenario development could incorporate mixed systems to reflect more realistic transformations.

Comparisons with other regions show similar strong influences of local conditions on nutrient fluxes and GHG emissions. For instance, in the North China Plain, climate extremes and water management drive nitrogen leaching and eutrophication concerns36. In places like the Mississippi River basin or Central Valley in the United States, high soil nitrogen levels or sensitive hydrogeology can exacerbate water pollution and require context-specific management37. Despite these differences, our findings confirm that local or regional data (long-term records in particular) are necessary for capturing how land use changes alter both nutrient cycling and the GHG balance.

While this study assumed uniform intensity within each land use type, varying intensity levels could alter results. For instance, organic farming typically runs at lower intensity relative to conventional farming; however, intensifying organic practices slightly (e.g., improving rotation with legume crops or optimizing nutrient inputs) might reduce yield gaps and maintain lower surpluses. A refined view of farming intensity would also clarify how best to balance environmental and food production goals under different socio-economic constraints.

Another significant factor affecting nutrient balances is crop rotation. Although this factor has been mitigated in our study by employing 16 years of data spanning various crop rotations, having data on the timing and nutrient dynamics of crop rotation stages could offer deeper insights into nutrient surplus or deficit occurrences. Moreover, the year-to-year variability in nutrient outputs (Figure S2 of the supplementary materials) revealed vulnerabilities to extreme events, such as the flooding in 2002 that lowered yields in 2003. These disturbances highlight the role of climate extremes in shaping nutrient balances. An important goal of SLM is to sustain productivity and minimize nutrient losses under changing climatic conditions. Consequently, future work should build on detailed, high-resolution analyses of weather extremes, crop rotations, and other farm-level practices to develop more robust, regionally tailored strategies.

For brevity, we did not differentiate between crop types extensively. However, in conventional farming regions of Lower Saxony, corn is exclusively cultivated in less fertile soils, while cereals are grown in highly fertile soils. An analysis of optimal crop spatial arrangement within our framework could yield further insights. The practical implementation of SLM requires multidisciplinary action, including consideration of regional policies, environmental regulations, and economic conditions. Integrating socio-economic analysis with comprehensive data can provide guidance for SLM and calibrate the trade-offs between sustainable land use and management change and nutrient balance.

Methods

Nutrient input assessment

The data on applied fertilizer in the region was documented for various activities including grazing, organic fertilization and mineral fertilization at monitoring locations.

For grazing activities, a comprehensive set of information was collected, encompassing details such as the type of livestock, the quantity of each type of animal (e.g., cow, sheep, horse, pig), the area over which grazing was spread, the average weight of the animals, duration of grazing and the specific land sections receiving manure. Moreover, animal waste samples from different monitoring locations were analyzed to ascertain nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content per kilogram of dry matter23. These analyses formed the basis for calculating fertilization rates per kilogram per hectare. Organic fertilization records included information on the type of organic fertilizer (e.g., pig manure, cow manure), the quantity applied per hectare (either volume or mass) and the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) contents. NPK values were derived using data from the Lower Saxony Chamber of Agriculture38, enabling the calculation of NPK application rates in kilograms per hectare. Mineral fertilizer application data encompassed details such as the brand, manufacturer, and quantity applied per hectare, whether in liquid or solid form, along with nutrient content information. This comprehensive dataset facilitated the calculation of NPK application rates in kilograms per hectare. Fertilizer application rates were determined by aggregating manure and organic fertilizer applications. Additionally, in organic farming areas, nitrogen fixation through legumes was calculated using data from German reference figures for agriculture report39 and incorporated into fertilizer application rates. The resulting values, averaged annually and per unit area, are presented in Fig. S(2, input/output) of the supplementary materials. The averages over the entire period are summarized in Fig. 1(b, input).

It is noteworthy here that in this study, we grouped all organic fertilizers, including conventional manure and any biogas digestate, under one category and used the total nutrient contents reported or measured for each source as the basis for fertilizer inputs. Potential nitrogen losses during storage or application were not explicitly modeled, and manure and digestate were treated as having similar nitrogen availability. All recorded organic nutrients were assumed to be plant-available, and fertilizer samples were considered effectively homogeneous. In addition, while an increase in SOC stocks can substantially increase soil nutrient pools, we did not explicitly account for these additional nutrient contributions in our calculations. Our nutrient balance estimates rely strictly on measured or reported fertilizer nutrient contents.

Nutrient output assessment

The assessment of nutrient output from agricultural land is accomplished through data collection, validation, nutrient content analysis, and yield measurements. To begin with, a comprehensive database was created to organize yield data from diverse sources, such as the hand-harvest records and the field registry, covering the period from 1991 to 2016. These data were chronologically arranged according to different agricultural practices to ensure systematic evaluation. Laboratory samples were supplemented using strict sampling protocols to ensure that samples taken from crops or soil accurately represent the overall population. Furthermore, different sources of data were standardized into uniform measurement units to ensure consistency throughout the analysis. To filter out outliers and eliminate potential errors in measurements or data entry, an outlier test was conducted using a threshold set at three standard deviations. In situations where hand-harvest yields were compared to machine-harvest yields, correction factors were applied. For crops like wheat, silage maize, and potatoes, it was found that hand-harvest yields did not significantly deviate from machine-harvest yields, so no correction factors were necessary. However, in the case of sugar beets, where hand-harvested yields were notably higher, a correction factor of 0.8 was used. Similarly, for corn, a factor of 0.9 was applied to account for the proportion of remaining plant material left in the field after harvesting. In analyzing nutrient content, the primary focus was on the essential nutrients nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), which were measured primarily from hand-harvested samples. Only those plant samples that underwent fresh mass determination were included in the analysis. The methodology for yield measurement varied between grassland and other crops. Grass yields were systematically recorded, factoring in each mowing event and grazing period. For grassland, each mowing was treated as a distinct harvesting event, while other grazing yields were derived from the dry matter intake of livestock, relying on standard intake values based on various agricultural practices. In cases where complete datasets were lacking, such as instances where specific grass cuts were not harvested, the remaining yields for that year could not be used for calculations, as reliable annual yield calculations were unattainable. Instead, the intensity of usage, categorized based on the farmer’s records in the field registry, was assigned according to the utilization categories established by the German Fertilizer Ordinance40. The entire methodology was designed to ensure comprehensive coverage and accuracy in measuring the nutrient output from agricultural practices. The resulting values, averaged annually and per unit area, are presented in Fig. S(2, input/output) of the supplementary materials. The averages over the entire period are summarized in Fig. 1(b, output).

Greenhouse gas emissions calculations and uncertainties

In this study, greenhouse gas emissions followed the Germany’s National Inventory Reportwith data primarily sourced from national-level reports on gaseous and particulate emissions from agriculture41,42. The emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), methane (CH4), and carbon dioxide (CO2) were computed for the region’s agricultural sector, taking into account its share of the total emissions in Germany and its soil management, crop production, and livestock activities. Data was also cross-referenced with local land-use statistics and production figures to ensure accurate inputs.

The methodology used aligns with the IPCC’s Tier 2 approach for N2O and CH4 emissions, which provides a higher resolution estimate by utilizing region-specific activity data and emission factors. For CO2 emissions, the calculations considered both direct emissions from fossil fuel use and indirect emissions associated with agricultural activities, such as the application of fertilizers and soil management practices.

To express the GHG emissions in a comparable manner, all emissions were converted into CO2 equivalents (CO2e) using Global Warming Potentials (GWPs) as defined by the IPCC43. The GWP for N2O was taken as 273, while for CH4, it was taken as 27.2. This conversion allows for a comprehensive assessment of the climate impact by aggregating emissions into a single metric and facilitates comparisons across different gases and activities.

The source data has implemented uncertainty in GHG emissions via using guidelines from the IPCC 2006 and EMEP 201944, by adopting Gaussian error propagation. This method was selected for its simplicity in handling large datasets, assuming normally distributed errors across variables. The propagation of uncertainties in emission factors and activity data was based on the assumption that these sources of error were independent. In our study area, the major sources of uncertainty in the GHG calculations are 1) Emission Factors: The most significant uncertainties arise from the emission factors, particularly for N2O emissions from managed soils and CH4 emissions from livestock. The IPCC default uncertainty for N2O emissions is 20%, while for CH4 from livestock, it can exceed this value for certain animal types. This uncertainty is a reflection of both spatial and temporal variability that emission factors do not fully capture. Additionally, the estimation of nitrogen fixation rates introduces further uncertainty into GHG calculations. Nitrogen fixation is influenced by several factors, such as soil type, crop species, and environmental conditions. While this variability was accounted for in the calculations, it can significantly affect the estimates of N₂O emissions. 2) Activity Data: Uncertainty in activity data (e.g., fertilizer application rates, livestock numbers) is generally lower than that of emission factors, but still contributes to the overall uncertainty. For instance, nitrogen excretion rates from livestock have an uncertainty of approximately 10%. In this study, activity data uncertainties were treated as uncorrelated across years.

For the year 2019, the overall uncertainty in GHG emissions from the agricultural sector was calculated at 29%. This figure is largely driven by the uncertainty in N2O emissions from soils, which are highly sensitive to both emission factors and management practices. The uncertainty in the trend of GHG emissions from 1990 to 2019 was estimated at 12.1%, which reflects the variability in long-term data collection and emission estimates41.

The uncertainty in emission estimates has significant implications for interpreting trends over time. We interpret a 12.1% uncertainty in the emission trend to mean that while the overall direction of emissions (increase or decrease) is clear, the magnitude of the change could be partially influenced by the inherent uncertainties in input data.

Another challenge in estimating uncertainty lies in the assumption that errors in observations and emission factors are normally distributed and uncorrelated. In practice, these errors may be skewed or correlated across different years or emission sources, complicating the estimation of total uncertainty. Moreover, the IPCC Tier 2 approach relies on regionalized data, which can introduce additional variability due to differences in measurement and reporting practices across regions.

The uncertainty in GHG calculations emphasizes the need for robust scenario analyses that account for potential variations in both activity data and emission factors. As different land-use scenarios were evaluated in this study, it is important to acknowledge that the uncertainties in input data may affect the reliability of projected GHG mitigation outcomes. Despite these uncertainties, the study’s findings provide valuable insights into the potential impacts of various land-use scenarios on the region’s GHG emissions and nutrient balance. More detailed uncertainty analysis that allows for a better understanding of the range of possible outcomes is thoroughly discussed in the report of calculations of gaseous and particulate emissions from German agriculture 1990–201941.

Land use and management and greenhouse gas emission scenarios

We applied various scenarios encompassing all land use transformations and illustrated the mean nutrient balance values across the entire observation period in Fig. 2(a). These ‘end-member’ scenarios serve as counter-factual stress-tests (i.e., extreme, hypothetical cases) designed to explore the limits of possible outcomes. These are not intended as policy recommendations, but rather to show the outer boundaries of potential changes in nutrient and greenhouse gas (GHG) levels, helping to bracket more realistic, mixed scenarios (Supplementary Table S1). Specifically, we first derived the average nutrient inputs and outputs for each land use type (grazing, organic farming, and conventional farming) from the 70 monitoring sites. We then multiplied these mean values by the proportion of each land use type across Lower Saxony, as determined by the Copernicus Land Cover Classification21 for each year, thereby upscaling the site-level nutrient fluxes to the regional scale. In this study, grazing was treated separately from conventional and organic farming as grazing areas in Lower Saxony are typically managed with substantially lower external inputs and a higher reliance on in-situ nutrient recycling compared to cropland systems. This separation allowed us to better capture the variability in nutrient balances and emissions across different land use types, rather than merging distinct management regimes. For the distribution of conventional versus organic farming within arable lands (96.6% conventional and 3.4% organic)23, we assumed that the proportions observed in our sample reflect the overall regional distribution, given the relatively homogeneous conditions of Lower Saxony. We focused on the 84% of Lower Saxony covered by arable land, grazing areas, and forests, excluding other land uses such as urban settlements, lakes, and rivers.

For each scenario and within each year, we expanded each land use type to cover this 84% of Lower Saxony, approximately 39,900 km². In formulating our end-member scenarios, arable land, grazing areas, and forests were considered as the three primary land use types. By examining hypothetical large-scale conversions among these categories, we aimed to explore the potential extremes of nutrient balances and greenhouse gas emissions that may result from such changes (for further details, refer to Table S1 of the supplementary materials). We multiplied the area of covered land by the corresponding nutrient inputs and outputs separately to derive the total amount of nutrients added and harvested annually. The nutrient balance for each scenario was calculated by subtracting inputs from outputs (Fig. S3), followed by averaging the results over the entire data collection period (2001–2016), as depicted in Fig. 2(a).

We determined the proportion of CO2 equivalent) emissions originating from the agricultural and forested sectors in Lower Saxony, utilizing national data from Germany. We assumed that the share of farming, grazing, and forested areas in Lower Saxony would proportionally represent its share of the country’s total GHG emissions. We then employed a methodology analogous to that used for nutrient calculations to estimate the GHG emissions for each scenario annually. Given that the data did not differentiate between organic and conventional farming, we conducted a comprehensive assessment across all farming scenarios. Additionally, we accounted for soil carbon sequestration when transitioning from one land use to another. Specifically, we used 0.87 and 1.65 Mg C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ for transitioning farmland to grazing25 and forest26,27; −0.70 and 0.37 Mg C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ for transitioning grazing to farmland28 and forest28,29; and −0.50 and −0.98 Mg C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹ for transitioning forest to grazing29 and farmland30 respectively (negative signs indicate net carbon release). Our methodology assumes uniformity in GHG emissions across the farming, grazing, and forested sectors, both nationwide and within Lower Saxony. The calculated GHG emissions from farming, grazing, and forested areas in Lower Saxony are presented as a proportional share of national emissions, with scenarios for allocating all 84% of Lower Saxony’s land to each sector from 2001 to 2016 illustrated in Fig. S4. The average emissions over the entire period are summarized in Fig. 2(b).

Inclusion and ethics in global research

Local researcher inclusion: Local researchers have been integral to every stage of the research process, from data collection to analysis, ensuring their significant contributions are recognized. Local relevance and collaboration: The research is locally relevant and has been implemented within the sustainable land management strategy of Lower Saxony, with collaboration from local partners to address specific needs and priorities. Roles, responsibilities, and capacity-building: Roles and responsibilities among collaborators were clearly defined, and capacity-building initiatives were facilitated for local researchers, enhancing their expertise in handling and analysing long-term soil and nutrient data. Research restrictions and exceptions: Due to collaboration with the Geological Survey of Lower Saxony (LBEG) and the availability of well-organized data, the research did not face any severe restrictions or prohibitions. Local ethics approval: As the research focused on environmental monitoring and land use, it did not require approval from a local ethics review committee, given the nature of the data utilized. Higher standards compliance: Environmental protection measures in Lower Saxony adhere to stringent European standards, ensuring the protection of biodiversity and sustainable production, thus aligning with the research objectives. Participant safety and risk mitigation: The study’s integration into the sustainable land management strategy of Lower Saxony ensures that it does not result in stigmatization, incrimination, or discrimination, as it inherently addresses social issues. Researcher safety: No significant health, safety, or security issues were encountered during the study. Benefit sharing: Benefit-sharing measures were not applicable as there were no transfers of biological materials, cultural artifacts, or traditional knowledge out of the country as part of the research process. Local and regional citations: Relevant local and regional research, particularly the regional measurements sourced from the “Das Boden-Dauerbeobachtungsprogramm von Niedersachsen,” has been appropriately cited to provide context and support to the research findings.

Data availability

All nutrient balance data23 utilized for the analytical procedures in this study are sourced from the GB 37 LBEG (2019) publication of the Geological Survey of Lower Saxony. The original publication in German is accessible via the provided link: https://nibis.lbeg.de/DOI/dateien/GB_37_Text_4a_Arial_web_neu.pdf. The raw data of the individual measurements of fertilizer application encompassing manure, organic, and mineral sources, are subject to data protection regulations. Nonetheless, we invite interested parties to engage with us, facilitating collaboration with the Geological Survey of Lower Saxony for access to this data, in acknowledgment of their participation in ongoing scientific inquiry. Greenhouse gas emission data41 are sourced from the Thünen report 77 and National Inventory Submissions 2024 for Germany42 available in English through the following link: https://www.thuenen.de/media/publikationen/thuenen-report/Thuenen_Report_77.pdf and https://unfccc.int/documents/637995.

References

FAO. The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture – Systems at breaking point. Synthesis report Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb7654en (2021).

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360, 987–992, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216 (2018).

Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHGemissions. Nat. Food 2, 198–209 (2021).

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en (FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO; (2023).

United Nations. Goal 2: Zero Hunger. United Nations Sustainable Development (2023).

Magnier, J. et al. Natural/small water retention measures: their contribution to ecosystem-based concepts. Sustainability 16, 1308 (2024).

Campanhola, F. Building a common vision for sustrainable food and agriculture FAO. Rome, Italy ISBN 978-92-5-108471-7 (print) (2014).

Reganold, J. P. & Wachter, J. M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat. Plants 2, 15221 https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2015.221 (2016).

Meemken, E.-M. & Qaim, M. Organic agriculture, food security, and the environment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 10, 39–63 (2018).

Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 485, 229–232 (2012).

Connor, D. J. Analysis of farming systems establishes the low productivity of organic agriculture and inadequacy as a global option for food supply. npj Sustain. Agric. 2, 2 (2024).

Seufert, V. & Ramankutty, N. Many shades of gray—the context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602638 (2017).

Häußermann, U. et al. Nitrogen soil surface budgets for districts in Germany 1995 to 2017. Environ. Sci. Eur. 32, 1–14 (2020).

Chmelíková, L., Schmid, H., Anke, S. & Hülsbergen, K. J. Nitrogen-use efficiency of organic and conventional arable and dairy farming systems in Germany. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 119, 337–354 (2021).

Badgley, C. et al. Organic agriculture and the global food supply. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 22, 86–108 (2007).

Muller, A. et al. Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture. Nat. Commun. 8, 1290 (2017).

Gomiero, T., Pimentel, D. & Paoletti, M. G. Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: conventional vs. organic agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 30, 95–124 (2011).

de Ponti, T., Rijk, B. & van Ittersum, M. K. The crop yield gap between organic and conventional agriculture. Agric. Syst. 108, 1–9 (2012).

Skinner, C. et al. Greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils under organic and non-organic management—a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 468–469, 553–563 (2014).

Meier, M. S. et al. Environmental impacts of organic and conventional agricultural products–Are the differences captured by life cycle assessment?. J. Environ. Manag. 149, 193–208 (2015).

[Dataset] Copernicus CLC 2018: European Environment Agency & European Environment Agency. CORINE Land Cover 2018, raster 100 m (2019).

[Dataset] DWD Climate Data Center (CDC): Multi-year station averages for the climate reference for the reference location in Lower Saxony, between 2001 and 2016 https://www.dwd.de/DE/klimaumwelt/klimaatlas/klimaatlas_node.html (2024).

[Dataset]Korte, K., Engelke, L., Groh, H., Severin, K. & Höper, H. Bewirtschaftung und Nährstoffbilanzen der landwirtschaftlich genutzten Bodendauerbeobachtungsflächen in Niedersachsen in den Jahren 2001 bis 2016 (in German). Geological Survey of Lower Saxony https://doi.org/10.48476/geober_37_2019 (2019).

de la Cruz, V. Y. V., Tantriani, Cheng, W. & Tawaraya, K. Yield gap between organic and conventional farming systems across climate types and sub-types: a meta-analysis. Agric. Syst. 211, 103732 (2023).

Conant, R. T., Cerri, C. E., Osborne, B. B. & Paustian, K. Grassland management impacts on soil carbon stocks: a new synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 27, 662–668 (2017).

Kahle, P., Hildebrand, E., Baum, C. & Boelcke, B. Long-term effects of short rotation forestry with willows and poplar on soil properties. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 53, 673–682 (2007).

Li, D., Niu, S. & Luo, Y. Global patterns of the dynamics of soil carbon and nitrogen stocks following afforestation: a meta-analysis. N. Phytol. 195, 172–181 (2012).

Deng, L., Zhu, G. Y., Tang, Z. S. & Shangguan, Z. P. Global patterns of the effects of land-use changes on soil carbon stocks. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 5, 127–138 (2016).

Don, A., Schumacher, J. & Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks–a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 1658–1670 (2011).

Qin, Z., Dunn, J. B., Kwon, H., Mueller, S. & Wander, M. M. Soil carbon sequestration and land use change associated with biofuel production: empirical evidence. Gcb Bioenergy 8, 66–80 (2016).

Tubiello, F. N. et al. The FAOSTAT database of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 015009 (2013).

Niedersächsische Ackerbau und Grünlandstrategie (in German). Ministry of Nutrition, Agriculture, and Consumer Protection of Lower Saxony https://www.gruenlandzentrum.org/niedersaechsische-ackerbau-und-gruenlandstrategie/ (2021).

Sassenrath, G. F., Schneider, J. M., Gaj, R., Grzebisz, W. & Halloran, J. M. Nitrogen balance as an indicator of environmental impact: Toward sustainable agricultural production. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 28, 276–289 (2013).

Witing, F., Gebel, M., Kurzer, H. J., Friese, H. & Franko, U. Large-scale integrated assessment of soil carbon and organic matter-related nitrogen fluxes in Saxony (Germany). J. Environ. Manag. 237, 272–280 (2019).

Don, A. et al. Land-use change to bioenergy production in Europe: implications for the greenhouse gas balance and soil carbon. Gcb Bioenergy 4, 372–391 (2012).

Fang, Q. X. et al. Quantifying Climate and Management Effects on Regional Crop Yield and Nitrogen Leaching in the North China Plain. J. Environ. Qual. 42, 1466–1479 (2013).

Harter, T. et al. Nitrogen Fertilizer Loading to Groundwater in the Central Valley. Final Report to the Fertilizer Research Education Program, Projects 11-0301 and 15-0454, California Department of Food and Agriculture and University of California Davis, 325p (2017).

Landwirtschaftskammer Niedersachsen. Nährstoffgehalte in organischer Düngung (in German). Webcode: 01033934 (2018).

KTBL – Kuratorium für Technik und Bauwesen in der Landwirtschaft E. V. Faustzahlen für die Landwirtschaft (in German) – Stand Oktober https://www.ktbl.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Allgemeines/Download/MiniFZ-Landwirtschaft.pdf (2018).

DÜV 2017. Regulation on the application of fertilizers, soil conditioners, culture substrates, and plant aids according to the principles of good agricultural practice in fertilization (translated from original German). – Date of enactment: May 26, https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Landwirtschaft/Pflanzenbau/DueV-Englisch.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (2017).

[Dataset] Haenel, H.-D., Rösemann, C. & Dämmgen, U. Calculations of Gaseous and Particulate Emissions from German Agriculture 1990 - 2018: Report on Methods and Data (RMD) Submission 2020. Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut, Germany https://doi.org/10.3220/REP1616572444000 (2020).

Gunther, D. 2024 National Inventory Document (NID). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/documents/637995 (2024).

2021. IPCC, 2021: Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Summary for Policymakers, Technical Summary, Frequently Asked Questions and Glossary. ISBN 978-92-9169-163-0. (2021)

EMEP-EMEP/EEA air pollutant emission inventory guidebook – 2019, EEA Report No 13/2019. http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2019 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Umwelt Bundesamt (UBA) of Germany under project number FKZ 37 2148 2050. The locations of the long-term soil observation monitoring stations, land use data, and detailed information about fertilizer application and nutrient output in Lower Saxony were provided by the Geological Survey of Lower Saxony (LBEG). We extend our gratitude to Hubert Groh for his collaboration in providing the data. Climate data, including annual precipitation and air temperature, were obtained from the climate data center domain of the German Weather Service (DWD). Geological information was provided by LBEG. Special thanks to Jörg Elbracht, Jona Golon, and Corinna Forberg for their invaluable cooperation and assistance. M.H.A and N.S. would like to acknowledge funding for AI4SoilHealth project from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No.101086179.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.S.G.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analyis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—review, editing and revising; M.H.A.: Data curation, formal analyis, methodology, visualization, writing—review, editing and revising; D.O.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—review, editing and revising; N.S.: conceptualization, supervision, investigation, methodology acquiring funding, writing—review, editing and revising.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sobhi Gollo, V., Afshar, M.H., Or, D. et al. Impacts of land use change on nutrient balance and greenhouse gas emissions: a regional perspective. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 34 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00076-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00076-y