Abstract

Nitrogen fertilizer application causes emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a gas that contributes to global warming. N2O emission reduction is possible given technological advances. But climate policy for N2O reduction faces challenges caused by complex information, entangled risks with invisible gains, and polarized values. Behavioral factors influence farmers’ decision-making, and here we argue context-dependent experimentation is needed to develop N2O reduction policies, proposing crop insurance as an example policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

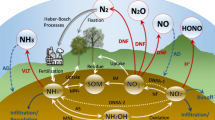

Nitrogen (N) fertilizer is essential for profitable crop production, but fertilizer application results in losses of reactive N forms that pollute water and air, including nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas contributing 6% to anthropogenic global warming that needs to be urgently mitigated1. Integrating N2O reduction targets into climate policy is possible given scientific and technological advances2. Yet, current policies have focused on water quality (nitrate pollution) and air quality (ammonia pollution), with only one country (Uruguay) explicitly including N2O in its climate goals as part of the Paris agreement (51–57% reduction in emissions expressed per GDP)2. Canada did not specify ‘N2O’ in its climate change plan but included a national target for reduction of emissions from fertilizer use of 30% below 2020 levels by 20303. Negative reaction from the agricultural sector to Canada’s reduction target (https://www.realagriculture.com/2022/08/trying-to-wrap-our-heads-around-the-federal-fertilizer-emissions-plan-a-timeline-of-how-we-got-to-this-point/). provides valuable lessons for countries considering N2O reduction goals in their climate policy. Here we argue that experimentation with real farmers under their specific contexts are needed for development of guidance for evidence-based N2O policymaking and effective policy implementation. We recommend that future N2O policies incorporate insights from behavioral and experimental economics, such as information framing, collective economic benefits, and behavioral nudges. Then, we use crop insurance as an example policy that could be designed using context-based economics experimentation findings to target N2O emission reduction efforts.

Behavioral economics, experimental economics, and their distinction

Behavioral economics is an emerging field grounded in empirical observations of human decision-making4. Although recent discussions have incorporated behavioral economics into fertilizer management5 by speculating how behavioral factors influence farmers’ decision-making, we argue context-dependent experimentation is needed to identify the cause and effects of policies. Experimental economics is an evidence-based field that relies on unique data generated from randomized trials to quantitatively examine the causal effects of various actionable instrument designs. Its principles rigorously address internal validity, external validity, incentive compatibility, and replicability. Although behavioral economics and experimental economics are sometimes used interchangeably, the former commonly refers to the incorporation of broad behavioral biases into economic models while the latter to a methodology that seeks evidence to quantify how specific variables impact decision-making. The need for context-dependent experimentation arises because agricultural producers’ decision making cannot be fully predicted by existing literature which is largely based on experimental evidence with other populations (i.e. non-farmers). Context-dependent experimentation targeted at developing improved N2O emission reduction policies needs to consider unique challenges such as complex information, risks and rewards, and polarization in values as discussed below.

Complex information

Nitrous oxide emission from soils is induced by nitrogen fertilizer addition but emissions are characterized by significant variation in time and space, driven by soil factors (e.g. soil aeration, carbon and nitrogen content) which are in turn modified by weather, crop and soil management6. Hence, the cause and effect of farmers’ production decisions are compounded by spatial and temporal heterogeneities and the role of risk such as weather events. In addition, the design of policies to achieve emission reduction targets is complicated by the complex production relationship between fertilizer practices and both the ‘good’ output (crop yield) and the ‘bad’ output (e.g. N2O emissions). As a result, there is substantial uncertainty and ambiguity in assessing farm-level metrics and, consequently, determining the optimal fertilizer management approach for each farm. This complexity hinders farmers’ ability to update their information and to learn effectively7. Moreover, these challenges are expected to intensify under climate change and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, because the response of crops to fertilizer applications and resulting environmental losses are highly sensitive to rainfall and temperature levels.

The behavioral economics literature suggests consumers are sensitive to information framing, thus simplifying messages and offering unambiguous recommendations to farmers are valuable suggestions. Yet challenges remain due to technical limitations in weather prediction and the impracticality of measuring N2O emissions at the farm level. Moreover, farmers’ social network differs from other populations’, posing differences in their social learning. Therefore, we propose that scientists and policymakers integrate an understanding of farmers’ decision-making processes during early stages of scientific innovation and policy design. Experimental economic methods can be employed ex-ante to understand how decision-making processes develop under perceptions of risk, uncertainty and ambiguity when technological frontiers advance with competing priorities, particularly in the context of agricultural production. This proactive approach should replace the current reliance on ex-post outreach strategies, which often do not fully consider the complexity of the decisions on fertilizer management facing farmers and fail to effectively address the heterogeneity among them. Results can guide innovation towards technological features that are most likely to succeed in their adoption.

Entangled risks with invisible gains

The design of policies to reduce N2O emission levels is complicated by the large number of farmers each contributing a small amount of an invisible gas with global impact, in contrast to other nitrogen pollutants (e.g. ammonia or nitrate) which have locally observable effects on air or water quality (e.g. algal blooms). In addition, decisions leading to reduced N2O emission levels, such as optimizing nitrogen fertilizer use, are entangled with risks to crop production at various stages of decision-making. For example, loss aversion is a behavioral bias affecting decision-making regarding nitrogen rate by both agronomists providing recommendations and farmers who ultimately make the final decision. As the optimal rate depends on the upcoming growing season conditions, which are unknown, there is a risk that the nitrogen rate is too low when basing recommendations on yield expectations for average weather conditions. Hence, loss aversion leads to applying “a little more” to hedge the risks of not having enough when needed. Although a farmer may benefit from the addition of fertilizer higher than needed in some years, the damage costs off the farm are imposed on society in the form of N2O emissions contributing to climate change. N2O emissions reflect market failure caused by negative externalities, as their costs are not fully borne by emitters but shifted to society. However, N2O reduction also presents unique challenges. In contrast with private gains (e.g. profits due to crop production) and observable environmental benefits (e.g. improved water quality), impacts of N2O reduction are largely invisible and global in nature. Because emissions are unobservable while field aesthetics and yields are visible, farmers are unlikely to sacrifice private benefits to contribute to the invisible global public good. These dynamics are further complicated by other behavioral factors such as fear of missing out, status quo bias, and social comparison8,9. For example, there is value to producers from having a healthy-looking crop field similar to their neighbours as well as previous years, which is determined by having non-limiting nitrogen, while the public costs of N2O emissions are not directly observable.

Potential solutions lie in addressing behavioral biases such as loss aversion and emphasizing collective economic benefits and redistribution. To address the latter, for instance, it is crucial to design mechanisms that ensure farmers’ benefits (or burden) do not come at an uncompensated expense burden (or benefit) of other key stakeholders. Making both the economic and environmental returns more salient—perhaps through regional aggregation—can enhance their visibility and appeal. A viable approach is to develop economic programs that encourage collective contributions to the public good while ensuring fair and desirable reallocation of the collective benefits. Public goods contribution is prone to free-riding behavior, while the behavioral and experimental economics literature has provided numerous solutions to encourage cooperation through behavioral nudges and strong institutions10. However, whether farming communities are nudgeable, and if so by whom, need to be determined through experimentation with farmers.

Polarization in values

Farmers’ views can be polarized around non-monetary values such as climate change, posing challenges to form attractive narratives universally appealing to all. In addition, farming communities exhibit strong social ties. Polarization in values necessitates careful consideration in designing information strategies to avoid unintended consequences such as a lower degree of trust and cooperation11. Unlike market segmentation, typically used to optimize profits when consumers have heterogeneous preferences, addressing the heterogeneity among producers demands innovative approaches. Considering that numerous practices related to nitrogen management can also improve soil quality and boost long-term economic returns, we recommend advocating economic benefits, which are universally valued by all producers. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of competing strategies of communication can only be assessed by investigating how farmers actually respond via randomization of candidate strategies with careful design.

An example of policy design: rethink crop insurance

Among various instruments developed to address agri-environmental issues, crop insurance is designed to mitigate financial risks associated with crop failures and to efficiently allocate optimal collective benefits. Since farmers often overapply fertilizers as perceived insurance against yield variability driven by loss aversion, crop insurance could serve as an effective instrument towards N2O reduction. However, limited evidence exists on how crop insurance can be used as a policy towards N2O reduction12 and insurance policies aimed at promoting agricultural sustainability have experienced limited participation13. This highlights the need for evaluating how evidence-based decision-making can be integrated into the design of crop insurance for N2O emission reduction.

Incorporating behavioral factors into crop insurance design can provide broad insights. For instance, default settings, a behavioral instrument that significantly improved social welfare14, could serve as a powerful tool to be integrated into insurance policy design. It is a simple tool that nudges individuals to select the socially optimal option without depriving them of other options. Applying default settings to nitrogen management, by embedding suggestive options in crop insurance programs to offer farmers clear and unequivocal recommendations, can help overcome the complexity associated with fertilizer management, encouraging farmers to adopt more sustainable practices. For example, the default option could be based on evidence of a nitrogen management plan that explains how application rates are determined. Other options with alternative premiums with or without fertilizer management conditions could also be available. To translate this literature-inspired conceptual idea into effective policy instruments, detailed experimental research is necessary to identify the causal effects of various available defaults on farmers’ decision-making.

Tailoring crop insurance programs to local contexts is important because socially optimal options and barriers are often shaped by regional realities. For instance, behavioral factors that help explain the low uptake of India’s Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana15 and Sub-Saharan Africa’s index-based insurance programs16, such as limited awareness and distrust, differ from those in European and North American contexts. Although more evidence is still needed, contextual behavioral experiments on agri-environmental topics are generally more common in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries17, primarily due to lower costs of implementation in these regions. Both within and between regions, caution is required when generalizing context-specific findings, and the key lies in conducting thorough experimentation in collaboration with representative stakeholders. Careful documentation of local contexts and experimental procedures can lead to valuable insights into agricultural emission reduction while addressing diverse regional challenges.

Conclusion

Experimentation on human decision-making is a novel research field, and recently has been identified as a frontier to assess the causal effects of environmental programs18. Context-based experimentation can be particularly important to inform the design of policies to reduce N2O levels, since fertilizer management practices are primarily determined through the maximization of private objectives with sub-optimal consideration of the damage costs imposed on others. The policy tools to internalize these external costs require an understanding of the decision-making process of farmers. Given the multitude of observable and unobservable factors that influence crop yield (and N2O emissions), there is a significant role of behavioral biases in the choice of practices by farmers. Experiments with farmers designed to inform N2O policies should target the complexity of decisions on fertilizer management, address the heterogeneity among farmers, determine if farming communities are nudgeable (i.e. a mechanism to encourage collective contributions to the public good), and if so by whom, while also considering polarization in values. Designing crop insurance as an N2O emission reduction policy mechanism has potential, but context-specific experimental research is needed to identify the causal effects of various available options on farmers’ decision-making.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Kanter, D. R., Ogle, S. M. & Winiwarter, W. Building on Paris: Integrating nitrous oxide mitigation into future climate policy. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 47, 7–12 (2020).

Government of Canada. Canada’s 2021 Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement. Environment and Climate Change Canada. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Canada%27s%20Enhanced%20NDC%20Submission1_FINAL%20EN.pdf (2021).

Thaler, R. H. Behavioral economics: Past, present, and future. Am. Econ. Rev. 106, 1577–1600 (2016).

Chai, Y., Pannell, D. J. & Pardey, P. G. Nudging farmers to reduce water pollution from nitrogen fertilizer. Food Policy 120, 102525 (2023).

Wagner-Riddle, C., Baggs, E. M., Clough, T. J., Fuchs, K. & Petersen, S. O. Mitigation of nitrous oxide emissions in the context of nitrogen loss reduction from agroecosystems: Managing hot spots and hot moments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 47, 46–53 (2020).

Tom, S. M., Fox, C. R., Trepel, C. & Poldrack, R. A. The neural basis of loss aversion in decision-making under risk. Science 315, 515–518 (2007).

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L. & Thaler, R. H. Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. J. Econ. Perspect. 5, 193–206 (1991).

Fliessbach, K. et al. Social comparison affects reward-related brain activity in the human ventral striatum. Science 318, 1305–1308 (2007).

Fehr, E. & Gächter, S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 980–994 (2000).

Dimant, E. Hate trumps love: The impact of political polarization on social preferences. Manage. Sci. 70, 1–31 (2024).

De Laporte, A., Schuurman, D., Skolrud, T., Slade, P. & Weersink, A. Business risk management programs and the adoption of beneficial management practices in Canadian crop agriculture. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 72, 309–324 (2024).

Palm-Forster, L., Swinton, S. M. & Shupp, R. S. Farmer preferences for conservation incentives that promote voluntary phosphorus abatement in agricultural watersheds. J. Soil Water Conserv. 72, 493–505 (2017).

Bernheim, B. D., Fradkin, A. & Popov, I. The welfare economics of default options in 401(k) plans. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 2798–2837 (2015).

Korekallu Srinivasa, A. et al. The Indian crop insurance puzzle: A discourse from behavioral science perspective. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 44, 377–382 (2021).

Aina, I. et al. Crop index insurance as a tool for climate resilience: Lessons from smallholder farmers in Nigeria. Nat. Hazards 120, 4811–4828 (2024).

Li, T. Editorial: Field experiments and farmers’ innovation adoption. Am. J. Agric. Econ. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)1467-8276.field-experiments (2023).

Ferraro, P. J. et al. Create a culture of experiments in environmental programs. Science 381, 735–737 (2023).

Acknowledgements

C.W.R. acknowledges funding by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) through the Alliance program supported by Fertilizer Canada and Grain Farmers of Ontario. T.L. would like to acknowledge funding by Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, Arrell Family Foundation, NSERC, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and Weston Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. L., C.W.R., A.W. conceptualized the manuscript. Y. L. contributed ideas related to crop insurance policy design. T.L. and C.W.R. wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Liu, Y., Weersink, A. et al. Guiding policies for agricultural nitrous oxide emission reduction with behavioral insights and experimentation. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 31 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00078-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00078-w