Abstract

Rotifer biomass may be amplified with natural phytoplankton while rotifer seeds can be raised with auto- and hetero-trophically cultured microorganisms. Centralizing the seed raising but decentralizing the biomass amplification should make scaling rotifer domestication up convenient. We configure here a conceptional system with which rotifer are domesticated with natural phytoplankton and harvested as animal feed, which may achieve simultaneously animal feed production and environmental governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

The world population is predicted to reach 9.7 billion in 2050, and 1250 million tons of meat and dairy must be produced annually to meet the global demand for animal-derived protein at the current consumption level until 20501. Such demand should amplify further the need of the feed protein2. Researchers and manufacturers have never ceased to exploit new sources of proteins. From plants and insects to microbes, diverse alternative proteins, e.g., cultured meat, mycoproteins, bacterial proteins among others, have been marketing3. Microalgal and insect proteins have received intensive attentions nowadays. Microalgae can produce 22–44 tons of protein per hectare per year on small production scales, and capture simultaneously carbon dioxide from air4,5. Insects are the human and animal diets for thousands of years and still are today, and the global market for edible insects is forecasted to reach US$ 8 billion by 20306. As the alternative sources of proteins, the cost, sustainability, environment friendliness, scalability among others determine their production efficiency while the allergens, hormones, diverse additives among others associate with their applications3. To date, a system driven by different energies, integrating economic and environmental profits, being easily scalable and highly efficient is not available yet. Here, we tried to configure a conceptional system with which rotifer are domesticated with natural phytoplankton inhabiting either freshwater or brackish and seawater and harvested as animal feed (Fig. 1).

Rotifer biology

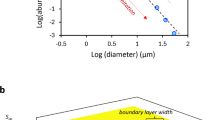

Rotifer, a group of multicellular animalcules, mainly inhabit freshwater, and some of them inhabit salt and brackish waters and even damp mosses and lichens. Rotifer live about two weeks, and are approximately 0.1 mm to 0.5 mm in body length. Some rotifer species are free swimming while others are worming or sessile. To date, about 2200 rotifer species have been documented in phylum Rotifera which consists of classes Seisonidea, Bdelloidea and Monogononta. Rotifer species cultured as the live feed of aquacultured animals belong to class Monogononta, which reproduce both sexually and asexually. Rotifer feed on microalgae, bacteria, protozoa and organic detritus up to 10 micrometers large, and are preyed upon by shrimp, crabs among others7.

The representative freshwater monogonont rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus is a species complex containing B. calyciflorus sensu stricto and other three, which success at temperatures varying between 19 °C and 37 °C8,9. The salt water or brackish rotifer B. plicatilis is also a species complex which contains B. plicatilis sensu stricto with larger body and genome size, B. ibericus with medium body and genome size and B. rotundiformis with small body and genome size as the representatives10,11.

Up to date, cross-mating is the only method tried to develop new rotifer strains12. The CRISPR methodology has been developed in B. manjavacas by microinjecting Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein into the vitellaria of young amictic females. A developmental gene (vasa) and a DNA mismatch repair gene (mlh3) have been CRISPRed out and in, respectively13. A horizontally acquired and overexpressed gene encoding a specific DNA ligase mediates the extreme tolerance of Bdelloid rotifer to radiation. Their heterologous expression in human cell lines significantly improves their radio-tolerance14. Comparatively less genetic improvement has been carried out for rotifer, and almost all cultured rotifer species/stains are the isolates from natural environment. In such scenario, we prefer to use “domesticate” rather than “culture/cultivate” to describe their growth in artificial environments.

Historical knowledge of domesticating rotifer as live feed

The rapid growth of aquaculture depends on the steady supply of animal seeds while the live feed for their larvae is critical for seed raising. Diverse techniques have been developed to produce rotifer as the best live feed of larvae, which include batch, continuous and semi-continuous and high-density domestications15. The live rotifer feed is non-substitutable; they may donate their digestive enzymes, gut neuropeptides and nutritional growth factors essential for the feed digestion of the larvae16.

B. calyciflorus and B. rubens are the most commonly mass-domesticated freshwater rotifer. They tolerate temperatures varying between 15 °C and 31 °C, and thrive in waters of various ionic composition. They have been successfully reared on the microalgae Scenedesmus costatogranulatus, Kirchneriella contorta, Phacus pyrum, Ankistrodesmus convoluus and Chlorella sp., yeast and artificial diets17. When the density increases, B. calyciflorus can aggregate linearly to form resting eggs18. When batch-domesticated with Chlorella and a supply of oxygen at 28 °C, B. calyciflorus reached the highest density, 19,200 ind. mL−1. When domesticated with a supply of oxygen and at constant acidity pH7 and 32 °C, the maximum density reached 33,500 ind. mL−1. The high-density domestication of B. calyciflorus can be realized under optimal conditions, dissolved oxygen > 5 mg L−1 and NH3-N < 12.0 mg L−1, under which, the density of freshwater B. calyciflorus reached the maximum 33,500 ind. mL−1 19. In Japan at commercial scales, stable high-density domestication of rotifer realized also densities of 20,000–30,000 ind. mL−1, and even 160,000 ind. mL−1 15.

B. plicatilis species complex is commonly used as the first feed of over 60 marine fish and 18 crustacean species17,20. When B. plicatilis at an initial density of 737 ± 80 ind. mL−1 was domesticated with 200 cells mL−1 of Chlorella sp., twice a day, in 100 L plastic cylindrical tanks and seawater renewed on every 5th day for 32 days, 1798 ± 25 ind. mL−1 was recorded on day 20, and > 1000 ind. mL−1 was sustained till day 3221. Continuously domesticating B. plicatilis under the optimal condition (dissolved oxygen ~8 mg L−1, 26–27 °C, salinity 10–20) can reach a density >1,000 ind. mL−1 22. In an automatic continuous system, dark and continuously supplied diluted sea water (salinity 20) at 24 °C, and harvested from the same volume of the seawater transferred into a harvest tank, 1,100 to 2,200 ind. ml−1 of B. plicatilis and 3,000 to 6,000 ind. mL−1 of B. rotundiformis were maintained23. When continuously cultured with Nannochloropsis oculata concentrate, B. plicatilis can reach a density of 2,188 ind. mL−1 on day 85 and maintain a density >1,500 ind. mL−1 from day 60 to day 90 when harvested every other day, 16 times in total24. The density of rotifers in these systems depends on feed quality and quantity, salinity, temperature and acidity of the medium which should be optimizable further.

Addition of γ-aminobutyric acid, porcine growth hormone, serotonin and human chorionic gonadotropin is known to improve the health status of cultured rotifers. The density and egg/female ratio of marine rotifer B. rotundiformis batch domesticated with dried N. oculata and Chlorella vulgaris was enhanced by 50 mg L−1 of γ-aminobutyric acid25. With the aid of oxygen supply and supplementation of favorable chemicals, the density of domesticated marine rotifer is expected to reach that of freshwater rotifer. These historical knowledges provided a methodological basis and the goal of rotifer mass domestication with natural phytoplankton.

Learning from the traditional nutrition enrichment of rotifer

Vitamin B12 is essential to human and animals including rotifer. Its biosynthesis is confined to a few bacteria and archaea, and its production relies on the fermentation of a group of natural bacteria and engineered E. coli26. Vitamin B12-producing bacteria have served as a nutritive complement for the domestication of B. plicatilis27. The vitamin B12 enriched Chlorella vulgaris completely supports and significantly improves the growth of B. plicatilis28 and B. calyciflorus29. The vitamin B12 rich Schizochytrium limacinum greatly enhances the growth of rotifers30. Vitamin B12 production can be produced in methanol-utilizing bacteria31 and engineered yeast32.

Rotifer must be enriched with DHA, EPA, ARA among others essential for the development and survival of marine fish and shrimp larvae33. It is not clear if these long chain PUFAs are essential for the growth of rotifer themselves; however, live microalgae and microalgal paste rich in omega-3 fatty acids, carbohydrates, lipids and plant sterols are the most appropriate rotifer feeds and rotifer PUFA enrichment species. Engineering microorganisms offers the best solution to a stable, sustainable and affordable production of omega-3 fatty acids34. A variety of genetic engineering tools and novel metabolic engineering strategies make Yarrowia lipolytica a robust workhorse for the production of an array of value-added products including PUFAs35,36. In addition to microalgae like Nannochloropsis sp., oleaginous fungi like Mortierella alpina and Thraustochytrids synthesize also ARA, EPA and DHA37. A marine thraustochytrid strain, Schizochytrium sp. KH105, produces docosahexaenoic acid, docosapentaenoic acid, canthaxanthin and astaxanthin which can be incorporated into rotifer and Artemia nauplii, and finally aid to the growth of fish larvae38. B. plicatilis feeding N. oculata yields high biomass, egg production and egg-carrying females, and N. oculata is optimal for its long-term biomass production39. These findings indicate that vitamin B12 and PUFA rich feeds should benefit the growth performance of rotifer, which are applicable in rotifer domestication with natural phytoplankton as the auxiliary means.

Domesticating rotifer with autotrophically cultured microalgae

Microalgae are rich in vitamins, antioxidants, proteins and lipids but low in carbohydrates, therefore, they are believed to be healthy food compounds40. Microalgae have been massively cultured for the production of diverse products including single cell proteins, animal feed, human food components, drug components, PUFA source, hot debated biofuel among others. However, culturing microalgae as an alternative protein source is limited by cost-ineffectiveness and downstream processing techniques including biomass harvesting41. Microalgal biomass production is also challenged by the high cost, weak knowledge about harmful organisms and loss of active ingredients42. Gene engineered microalgae have been suggested for protein drug development and edible vaccine production43, which may aid to mitigate these limitations and challenges. Feeding rotifer with the autotrophically cultured microalgae and using the harvested rotifer as animal feed may provide a way out of the dilemma; harvesting rotifer as animal feed detours at least the extremely energy-intensive microalgal harvest. The high cost of microalgal culture can be reduced further when the microalgae are used in raising rotifer as mass domestication seeds.

Domesticating rotifer with heterotrophically cultured microorganisms

The heterotrophically cultured microorganisms including microalgae, bacteria, yeast, dinoflagellate among others contain complete profiles of nutrients, which should support well the high-density domestication of rotifers in combination with auxiliary techniques like oxygen aeration and hormone supplementation. These heterotrophically cultured microorganisms themselves are the sources of single cell protein. Their values in rotifer domestication embodies in the stable and sustainable raising of rotifer seeds for biomass amplification.

The biomass of Arthrospira platensis, Chlorella vulgaris and Dunaliella salina has been used as the sources of food44,45. A group of microalgae can grow heterotrophically, yielding as much as 25-fold biomass of those grow autotrophically46. From glucose, an ultrahigh-cell-density of 286 g/L Scenedesmus acuminatus has been grown in 7.5 L bench-scale fermenters47. The heterotrophic and mixotrophic microalgae metabolizing volatile fatty acids have been isolated and tentatively cultured48. Crypthecodinium cohnii, a marine heterotrophic dinoflagellate, has been fermented to accumulate high amounts of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids49. A marine thraustochytrid Schizochytrium sp. is known as an ideal producer of high levels of polyunsaturated fatty oils, in particular, docosahexaenoic acid50. Thraustochytrids can accumulate over 150 g/l biomass and contain up to 55% lipids. Their broad substrate utilization capacity, several effective key metabolic pathways and a well-developed suite of bioprocess engineering strategies all point toward their great promise for the future exploitation51. Thraustochytrids have been increasingly studied for their faster growth rate and high lipid content52.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is popular for alcohol fermentation from carbohydrates for thousands of years while its biomass is rich in proteins, vitamins and minerals, making it a valuable ingredient in animal feed and other food products. The fermentation can be orientated to shunt the sugar metabolism on to the oxidative pathway, creating more ATP and biomass53. Some strategies like glucose-limited feeding may aid to increasing yeast biomass production54. The engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y294 simultaneously expresses α-amylase and glucoamylase genes and hydrolyzes raw starch55,56.

In line with microalgae and yeast, bacteria have also been cultured as the single cell proteins57. Engineered P. putida may produce value added products for application in the food and feed from the substrates generated from renewable feedstocks, such as lignocellulose, oils and silage58.

Rotifer seed raising

Both autotrophically and heterotrophically cultured microorganisms including microalgae, bacteria, yeasts, dinoflagellate among others can be used as the rotifer feed in raising rotifer seeds in the form of live individuals and resting eggs. These rotifer seeds may be amplified several orders of magnitude in biomass by feeding them with natural phytoplankton pumped into the rotifer domestication facilities from eutrophicated lakes and bays. The rotifer seeds may be expensive; however, they assure the stability, reliability, and sustainability of seed supply. Mass-produced rotifer individuals can be preserved at low temperature, and directly used as the seeds. However, for collection, transportation and storage, resting eggs and amictic eggs are recommended for starting new round of domestication20.

Domesticating rotifer with natural phytoplankton

Phytoplankton refers to one or more of thousands of natural eukaryotic microalgae. In practice, phytoplankton cover also the cyanobacteria like spirulina/arthrospira. Here, we call phytoplankton inhabiting lakes, reservoirs, pools and seashore bays the natural phytoplankton. The rotifer seeds can be delivered to the sites with rich natural phytoplankton, for example eutrophicated lakes, and amplified there in biomass in facilities either luxuries or shabby. The natural phytoplankton are pumped into the domestication facilities, and the rotifer at the desirable density are simply intercepted using the nets like those for phytoplankton. We prefer to use “interception” instead of “filtration” to describe the rotifer harvest; the interception nets have much bigger meshes than filtration nets. Natural phytoplankton is almost costless while rotifer harvesting through interception should be cheap, which should yield both economic and environmental benefits, and reimburse rotifer seed raising. The harvested rotifer biomass can be sun-dried, which should reduce the production cost further. Once the supply chain of rotifer seeds is established, the rotifer biomass can even be amplified by individual farmers alongside the eutrophicated pools. With autotrophically cultured microalgae, the outdoor domestication of rotifer has been tried59.

The dry weight of B. calyciflorus individuals varied between 0.06 and 0.47 μg60, and we take the median 0.25 μg in calculating the rotifer yield. If the rotifer density can reach the high one touched under the optimal conditions, which varies between 20,000 and 30,000 ind. mL−1, then 1000–1500 tons of dry rotifer can be produced in 10,000 m2 waterbody (1 m in depth), i.e. one hectare, and in one year (20 times of harvest each). The natural phytoplankton inhabiting eutrophicated lakes, seashore bays among others seem to be inexhaustible. Removal of nutrients by domesticating rotifer with natural phytoplankton is also one of the most attractive imaginable biomanipulation strategies to our most knowledge. We do not clear if the density of marine rotifer can reach that of freshwater rotifer. The facility similar to that of freshwater rotifer domestication will yield one tenth of dry rotifer (100–150 tons) if 2000–3000 ind. mL−1 can be realized, which is worth trying.

Eutrophication and climate change catalyze dense and sometimes toxic cyanobacterial blooms which threaten ecosystem functioning and degrade water quality61. One of the most important grazers that aids to control cyanobacterial blooms is Daphnia although cyanobacterial toxins like microcystins stress it indeed. Cyanotoxins include microcystins, hepatotoxins, digestive inhibitors, neurotoxins and cytotoxins. Cladocera like Daphnia consume cyanobacteria although they are poor feeds62. With the aid of gut bacteria, copepods feed on phytoplankton mixture containing nodularin-producing cyanobacteria63. The non-rotifer micrograzers may dissipate cyanobacterial blooms first while rotifers survive well and thrive even the blooms and remove them later64. The cyanotoxins have negative effects on rotifer growth and reproduction; however, Brachionus calyciflorus changes its life strategy and grazing intensity in response to the toxic cyanobacterial blooms65,66. Marine copepods and rotifers like B. plicatilis survive the harmful P. globose blooms by adjusting their life history strategy67. Hydrogen peroxide is often used to reducing cyanobacterial abundance; cyanobacteria are more sensitive than other phytoplankton68. With the technical innovation and implementation, it is expected that the influence of cyanobacteria on rotifer growth and proliferation can be smoothed away. Actually, a simple barrier net ahead of water pumping should separate floating filamentous cyanobacteria from other phytoplankton. To these understanding, we believe that the cyanobacterial blooms may interrupt the continuous domestication of rotifer but should not terminate its domestication.

Powering rotifer domestication with non-solar energy

The methanotrophs growing in methane at 500 ppm and lower have been identified69. The synthetic methylotrophic bacteria and yeasts such as E. coli, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus subtilis and S. cerevisiae metabolize methane and methanol70. The biomass of these microorganisms contains major nutrients such as proteins, fatty acids among others, which may serve as the protein source of animal feed including rotifers71. Heterotrophically culturing microorganisms like bacteria and yeasts with C1 carbon sources like methanol may extend rotifer domestication to a fossil energy supported process. Either autotrophically or heterotrophically microalgae may be combined with these bacteria and yeasts and used to raising rotifer seeds and raring them directly even.

The commonest Daphnia species are often arrested together with shrimp and crab eggs as the food of people living in Chaoshan area, Guangdong Province, China. Copepods have been recommended as human food very early72,73. The cladocera and copepods have also been cultured as the live feed of aquacultured animals. Comparatively, the studies on the biology and culturing methodology of copepods and cladocera are less intensive. In seeable future, industrializing rotifer domestication should prosper with every passing day. Currently, the price of fish meal on Chinese market varies between 1333 and 1666 US$ ton−1 (10,000–17,000 RMB ton−1). If dry rotifer can replace fish meal, running a rotifer biomass amplification factory will be highly feasible and profitable. The rotifer seeds raised with the proposed strategy may be amplified also as the open feed of fish and crab larvae. The microorganisms fermented from one carbon materials may be integrated into rotifer domestication. Such trial will build a linkage between rotifer biomass production with fossil energy, providing a trade-off between eating and other exhaustions when our food supply is extremely short.

The technologies controlling the inherent predators in natural water

Using natural phytoplankton as the alternative feed of rotifer is highly risky; natural water body could be plenty of potential predators such as ciliates, other rotifers, pathogenic bacteria, predatory fungi among others. To control the rotifers in microalgal cultivation and break cells in microalgal processing, the technologies like high-voltage pulse electroshock74, pulsed electric field75, electroporation76, high-pressure homogenization77, ultrasonication78,79, ionizing radiation80,81 among others have been developed. The natural water body contains the phytoplankton in appropriate size as rotifer feed. Pretreating the water with these techniques will kill these predators and may break their cells completely. The organic materials released will be transformed into bacterial cells in a short-term fermentation (remaining in ponds, pools or tanks for couple of days before use), and then caught by rotifers as their feed. This pretreatment may completely transform phytoplankton into bacteria, making them the most appropriate feed source of rotifers. Within acceptable range, the harmfulness to ecology should not be obvious.

The destroyed include pathogens of rotifer in the natural water body, which will avoid their disease-causing risk. These pathogens may also be suppressed by the heavy population of rotifers inoculated. Breeding disease resistant or stress tolerant rotifer varieties will be the most effective way of shooting the disease trouble. Pathogens and hosts battle permanently, no final winner and no final loser. Crops and humans ourselves will never end the war between pathogens and hosts. We believe that we have the ability of controlling the pathogens to the level of “existing but harmless”.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Ritala, A., Häkkinen, S. T., Toivari, M. & Wiebe, M. G. Single cell protein-state-of-the-art, industrial landscape and patents 2001–2016. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2009 (2017).

Kim, S. W. et al. Meeting global feed protein demand: challenge, opportunity and strategy. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 7, 221–743 (2019).

Jones, N. Fungi bacon and insect burgers: a guide to the proteins of the future. Nature 619, 26–28 (2023).

Amorim, M. L. et al. Microalgae proteins: production, separation, isolation, quantification, and application in food and feed. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 1976–2002 (2021).

Janssen, M., Wijffels, R. H. & Barbosa, M. J. Microalgae based production of single-cell protein. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 75, 102705 (2022).

Liceaga, A. M., Aguilar-Toalá, J. E., Vallejo-Cordoba, B., González-Córdova, A. F. & Hernández-Mendoza, A. Insects as an Alternative Protein Source. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 13, 19–34 (2022).

Wallace, R. L., Snell, T. W. & Smith, H. A. Phylum Rotifera. In: Thorp. J. H., Rogers, D. C. (eds.) Thorp and Covich’s freshwater invertebrates (edition 4): Ecology and general biology (vol. I). Elsevier Inc. Amsterdam. pp. 225–271 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Temporal patterns and processes of genetic differentiation of the Brachionus calyciflorus (Rotifera) complex in a subtropical shallow lake. Hydrobiologia 807, 313–331 (2017).

Wen, X., Xi, Y., Zhang, G., Xue, Y. & Xiang, X. Coexistence of cryptic Brachionus calyciflorus (Rotifera) species: roles of environmental variables. J. Plankton Res. 38, 478–489 (2016).

Gómez, A., Serra, M., Carvalho, G. R. & Lunt, D. H. Speciation in ancient cryptic species complexes: evidence from the molecular phylogeny of Brachionus plicatilis (Rotifera). Int. J. Org. Evolution 56, 1431–1444 (2002).

Fontaneto, D., Kaya, M., Herniou, E. A. & Barraclough, T. G. Extreme levels of hidden diversity in microscopic animals (Rotifera) revealed by DNA taxonomy. Mol. Phylogenetics Evolution 53, 182–189 (2009).

Kotani, T. The current Sstatus of the morphological classification of rotifer strains used in aquaculture. In: Hagiwara, A., Yoshinaga, T. (eds.) Rotifers. Fisheries Science Series. Springer, Singapore (2017).

Feng, H., Bavister, G., Gribble, K. E. & Welch, D. B. M. Highly efficient CRISPR-mediated gene editing in a rotifer. PLoS Biol. 21, e3001888 (2023).

Nicolas, E. et al. Horizontal acquisition of a DNA ligase improves DNA damage tolerance in eukaryotes. Nat. Commun. 14, 7638 (2023).

Yoshimatsu, T. & Hossain, M. A. Recent advances in the high-density rotifer culture in Japan. Aquacult. Int. 22, 1587–1603 (2014).

Kolkovski, S. Digestive enzymes in fish larvae and juveniles-implications and applications to formulated diets. Aquaculture 200, 181–201 (2001).

Dhert, P., Rotifers. In: Lavens, P., Sorgeloos, P. (eds.) Manual on the production and use of live food for aquaculture. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 361. Rome, FAO. pp. 49–78 (1996).

Cheng, S. H. et al. Observations of linear aggregation behavior in rotifers (Brachionus calyciflorus). PLoS ONE16, e0256387 (2021).

Park, H. G. et al. High-density culture of the freshwater rotifer, Brachionus calyciflorus. Hydrobiologia 446, 369–374 (2001).

Hagiwara, A., Kim, H. J. & Marcial, H. Mass culture and preservation of Brachionus plicatilis sp. complex. In: Hagiwara, A., Yoshinaga, T. (eds.) Rotifers. Fisheries Science Series. Springer, Singapore. pp. 35–45 (2017).

Sharma, J. G., Masuda, R., Mand, T. & Chakrabarti, R. The continuous culture of rotifer Brachionus plicatilis with seawater. Madridge J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2, 35–37 (2018).

Lawrence, C., Sanders, E. & Henry, E. Methods for culturing saltwater rotifers (Brachionus plicatilis) for rearing larval zebrafish. Zebrafish 9, 140–146 (2012).

Fu, Y., Hada, A., Yamashita, T., Yoshida, Y. & Hino, A. Development of a continuous culture system for stable mass production of the marine rotifer Brachionus. Hydrobiologia 358, 145–151 (1997).

Önal, U., Topaloğlu, G. & Sepil, A. The performance of continuous rotifer (Brachionus plicatilis) culture system for ornamental fish production. J. Life Sci. 9, 207–213 (2015).

Ogello, E. O., Sakakura, Y. & Hagiwara, A. Culturing Brachionus rotundiformis Tschugunoff (Rotifera) using dried foods: application of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Hydrobiologia 796, 99–110 (2017).

Fang, H., Kang, J. & Zhang, D. Microbial production of vitamin B12: a review and future perspectives. Micro., Cell Fact. 16, 15 (2017).

Yu, J., Hino, A., Ushiro, M. & Maeda, M. Function of bacteria as vitamin B12 producers during mass culture of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 55, 1799–1806 (1989).

Maruyama, I. & Hirayama, K. The culture of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis with Chlorella vulgaris containing vitamin B12 in its cells. J. World Aquac. Soc. 24, 194–198 (1993).

Woo, L. K. & Gi, P. H. Effects of food and vitamin B12 on the growth of a freshwater rotifer (Brachionus calyciflorus) in the high-density culture. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 36, 606–613 (2003).

Hayashi, M., Yukino, T., Watanabe, F., Miyamoto, E. & Nakano, Y. Effect of vitamin B12-enriched Thraustochytrids on the population growth of rotifers. Biosci., Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 222–225 (2007).

Nishio, N., Yano, T. & Kamikubo, T. Isolation of methanol-utilizing bacteria and its vitamin B12 production. Agric. Biol. Chem. 39, 21–27 (1975).

Lehner, S. & Boles, E. Development of vitamin B12 dependency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 23, foad020 (2023).

Lubzens, E. Raising rotifers for use in aquaculture. In: May, L., Wallace, R., Herzig, A. (eds.) Rotifer Symposium IV. Developments in Hydrobiology, vol 42. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 245–255 (1987).

Qin, J., Kurt, E., LBassi, T., Sa, L. & Xie, D. Biotechnological production of omega-3 fatty acids: current status and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1280296 (2023a).

Cao, L. et al. Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica to produce nutritional fatty acids: current status and future perspectives. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 7, 1024–1033 (2022).

Jia, Y. L., Wang, L. R., Zhang, Z. X., Gu, Y. & Sun, X. M. Recent advances in biotechnological production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by Yarrowia lipolytica. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 8920–8934 (2022).

Yan, C. et al. Universal and unique strategies for the production of polyunsaturated fatty acids in industrial oleaginous microorganisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 70, 108298 (2024).

Yamasaki, T. et al. Nutritional enrichment of larval fish feed with thraustochytrid producing polyunsaturated fatty acids and xanthophylls. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 200–206 (2007).

Eryalçın, K. M. Nutritional value and production performance of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis Müller, cultured with different feeds at commercial scale. Aquacult. Int. 27, 875–890 (2019).

Rozenberg, J. M. et al. Recent advances and fundamentals of microalgae cultivation technology. Biotechnol. J. 19, 2300725 (2024).

Udayan, A., Sirohi, R., Sreekumar, N., Sang, B. I. & Sim, S. J. Mass cultivation and harvesting of microalgal biomass: Current trends and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 344(Part B), 126406 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Biotechnologies for bulk production of microalgal biomass: from mass cultivation to dried biomass acquisition. Biotechnol. Biofuels 16, 131 (2023b).

Dehghani, J. et al. 2022. Microalgae as an efficient vehicle for the production and targeted delivery of therapeutic glycoproteins against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Mar. Drugs 20, 657 (2022).

Garofalo, C., Norici, A., Mollo, L., Osimani, A. & Aquilanti, L. Fermentation of microalgal biomass for innovative food production. Microorganisms 10, 2069 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Optimization of heterotrophic culture conditions for the alga Graesiella emersonii WBG-1 to produce proteins. Plants 12, 2255 (2023).

Morales-Sánchez, D., Martinez-Rodriguez, O. A. & Martinez, A. Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae: production of metabolites of commercial interest. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 92, 925–936 (2017).

Jin, H. et al. Ultrahigh-cell-density heterotrophic cultivation of the unicellular green microalga Scenedesmus acuminatus and application of the cells to photoautotrophic culture enhance biomass and lipid production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 117, 96–108 (2020).

Lacroux, J. et al. Microalgae screening for heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth on butyrate. Algal Res. 67, 102843 (2022).

Didrihsone, E. et al. Crypthecodinium cohnii growth and omega fatty acid production in mediums supplemented with extract from recycled biomass. Mar. Drugs 20, 68 (2022).

Yaguchi, T., Tanaka, S., Yokochi, T., Honda, D. & Higashihara, T. Production of high yields of docosahexaenoic acid by Schizochytrium sp. strain SR21. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 74, 1431–1434 (1997).

Sun, X., Xu, Y. & Huang, H. Thraustochytrid cell factories for producing lipid compounds. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 648–650 (2021).

Du, F. et al. Biotechnological production of lipid and terpenoid from thraustochytrids. Biotechnol. Adv. 48, 107725 (2021).

Wani, A. K. et al. Contribution of yeast and its biomass for the preparation of industrially essential materials: a boon to circular economy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 23, 101508 (2023).

Vieira, ÉD., Andrietta, D. A. G. & Andrietta, S. R. Yeast biomass production: a new approach in glucose-limited feeding strategy. Braz. J. Microbiol. 44, 551–558 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. Reducing glucoamylase usage for commercial-scale ethanol production from starch using glucoamylase expressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioresour. Bioprocess 8, 20 (2021).

Cripwell, R. A., Rose, S. H., Favaro, L. & van Zyl, W. H. Construction of industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for the efficient consolidated bioprocessing of raw starch. Biotechnol. Biofuels 12, 201 (2019).

Singh, A. K., Prajapati, K. S., Shuaib, M., Kushwaha, P. P. & Kumar, S. Microbial proteins: a potential source of protein. In: Egbuna, C., Tupas, G. D. (eds.) Functional foods and nutraceuticals. Springer, Cham. pp. 39–147 (2020).

Weimer, A., Kohlstedt, M., Volke, D. C., Nikel, P. I. & Wittmann, C. Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida: advances and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 7745–7766 (2020).

Mejias, C., Riquelme, C., Sayes, C., Plaza, J. & Silva-Aciares, F. Production of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis (Müller 1786) in closed outdoor systems fed with the microalgae Nannochloropsis gaditana and supplemented with probiotic bacteria Pseudoalteromonas sp. (SLP1). Aquacult. Int. 26, 869–884 (2018).

Pauli, H. R. A new method to estimate individual dry weights of rotifers. Hydrobiologia 186, 355–361 (1989).

Huisman, J. et al. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 471–483 (2018).

Schwarzenberger, A. Negative effects of cyanotoxins and adaptative responses of Daphnia. Toxins 14, 770 (2022).

Gorokhova, E., El-Shehawy, R., Lehtiniemi, M. & Garbaras, A. How copepods can eat toxins without getting sick: gut bacteria help zooplankton to feed in cyanobacteria blooms. Front. Microbiol. 11, 589816 (2021).

Sweeney, K., Rollwagen‑Bollens, G. & Hampton, S. E. Grazing impacts of rotifer zooplankton on a cyanobacteria bloom in a shallow temperate lake (Vancouver Lake, WA, USA). Hydrobiologia 849, 2683–2703 (2022).

Liang, Y., Ouyang, K., Chen, X., Su, Y. & Yang, J. Life strategy and grazing intensity responses of Brachionus calyciflorus fed on different concentrations of microcystin-producing and microcystin-free Microcystis aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 7, 43127 (2017a).

Liang, Y., Su, Y., Ouyang, K., Chen, X. & Yang, J. Effects of microcystin-producing and microcystin-free Microcystis aeruginosa on enzyme activity and nutrient content in the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 10430–10442 (2017b).

Sun, Y. et al. Trade-of between reproduction and lifespan of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis under different food conditions. Sci. Rep. 7, 15370 (2017).

Asaeda, T., Rahman, M. & Abeynayaka, H. D. L. Hydrogen peroxide can be a plausible biomarker in cyanobacterial bloom treatment. Scientifc Rep. 12, 12 (2022).

He, L. et al. A methanotrophic bacterium to enable methane removal for climate mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2310046120 (2023).

Gan, Y. et al. Metabolic engineering strategies for microbial utilization of methanol. Eng. Microbiol. 3, 100081 (2023).

Linder, T. Making the case for edible microorganisms as an integral part of a more sustainable and resilient food production system. Food Sec. 11, 265–278 (2019).

Herdman, W. Edible copepoda. Nature 56, 565 (1897).

Thompson, I. Copepoda as an article of food. Nature 44, 294 (1891).

Hong, J. et al. Effective removing of rotifer contamination in microalgal lab-scale raceway ponds by light-induced phototaxis coupled with high-voltage pulse electroshock. Bioresour. Technol. 394, 130241 (2024).

Rego, D. et al. Control of predators in industrial scale microalgae cultures with pulsed electric fields. Bioelectrochemistry (Amst., Neth.) 103, 60–64 (2015).

Kashyap, M., Ghosh, S., Bala, K. & Golberg, A. High voltage pulsed electric field and electroporation technologies for algal biomass processing. J. Appl. Phycol. 36, 273–289 (2024).

Ferreira, A. et al. Impact of high-pressure homogenization on the cell integrity of Tetradesmus obliquus and seed germination. Molecules 27, 2275 (2022).

Liu, Y., Liu, X., Cui, Y. & Yuan, W. W. Ultrasound for microalgal cell disruption and product extraction: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 87, 10605487 (2022).

Liao, L., Shen, Y., Xie, C., Zhang, Y. & Yao, C. Ultrasonication followed by aqueous two-phase system for extraction, on-site modification and isolation of microalgal starch with reduced digestibility. Ultrason. Sonochem. 106, 106891 (2024).

Vojvodić, S. et al. The effects of ionizing radiation on the structure and antioxidative and metal-binding capacity of the cell wall of microalga Chlorella sorokiniana. Chemosphere 260, 127553 (2020).

Stanić, M. et al. Low-dose ionizing radiation generates a hormetic response to modify lipid metabolism in Chlorella sorokiniana. Commun. Biol. 7, 821 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Science & Technology Innovation Project of Laoshan Laboratory (LSKJ202203205); and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102757).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G. and H.L. collected literatures, and generalized the findings from them. G.Y. developed the main idea, designed the conceptional framework, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, L., Liu, H. & Yang, G. Domesticating rotifer as animal feed using natural phytoplankton from eutrophic waters. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 38 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00082-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00082-0