Abstract

Agricultural soil affected by metal(loid) contaminants not only endangers food safety but also causes environmental pollution and soil health degradation. Unlike degradable organic pollutants, metal(loid)s, including arsenic (As), are non-degradable and only shift between environments. The Earth’s As amount remains constant, raising the question of whether we should dilute or concentrate it. To address this, we examined real-world soil remediation outcomes for insights. We have collected data from ~30 agricultural soil remediation projects in the world, with the longest operation time being 15 years. Based on their effect on As distribution, the As-contaminated soil remediation technologies were divided into three categories: concentration, dilution, and no change. Impacts of these three scenarios on food safety, soil As concentration, and bioavailability were analyzed. Post-remediation, the agricultural produce derived from these soils consistently meets the pertinent national standards. Scenario simulation was made at the regional scale, comparing the outcomes of soil remediation technologies, specially focusing on the distribution of As. Taking into account the results from different scales, we propose that dilution could be a viable alternative to concentration or no-change approaches for remediating low-As-contaminated agricultural soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agricultural soil pollution by metal(loid)s poses a multifaceted threat. It jeopardizes food safety, contributes to broader environmental pollution, and leads to the degradation of soil health1. Toxic metal(loid)s like arsenic (As) and cadmium (Cd) still present non-negligible threats to human health and food safety2,3, due to their wide distribution, non-degradability and extremely high toxicity4. The contamination of agricultural soils worldwide by metal(loid)s and its associated soil abandonment poses a significant obstacle to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)5,6,7.

A range of remediation technologies for metal(loid)-contaminated agricultural soils has emerged8. However, unlike organic pollutants, which can be broken down into less harmful substances9, toxic metal(loid)s cannot be eliminated; they can only change in distribution or chemical form. This raises a critical question: Is it better to disperse toxic metal(loid) evenly or to concentrate them in one place? Given the increasing As contamination in agricultural soils10, coupled with its high toxicity and diverse chemical forms, we use As as a case to discuss the metal(loid) pollution of agricultural soil.

In history, As is like a double-edged sword in respect to its application for healing purposes and for their use in murder or suicide11. Arsenic-bearing minerals have been mined by the early Chinese, Indian, Greek, and Egyptian since 4th century AD12. Evidence suggests that human activities are responsible for As fluxes that surpass natural levels for over two millennia13. The main human-induced sources of As in soil are non-ferrous mining, energy use, smelting, and agricultural practices10.

Arsenic has multiple oxidation states in nature, including –3, 0, +3, and +514. Its speciation and bioavailability are mainly regulated by redox potential and pH15. Inorganic As, such as As(III) and As(V), is more toxic than organoarsenic compounds, as it persists longer in organisms and is difficult to excrete. Specifically, As(III) is 60 times more toxic than As(V), while As(V) is 70 times more toxic than monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and dimethylarsinic acid (DMA)16. Organoarsenic species like arsenobetaine and arsenolipids are considered low-toxic or non-toxic17.

In terms of ecological and health impacts, As(V) disrupts plant phosphate metabolism, while As(III) binds to protein thiol groups to impair cellular functions. Chronic exposure to As through drinking water and staple foods poses a significant global health risk18,19,20. Numerous cases of As poisoning have been documented across the globe, attributed to both natural and human-induced sources of excessive As21.

Globally, As is classified as a Group I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer and listed among the top ten toxic substances by the World Health Organization22. The dose between 0.3 and 8 μg As /kg bw/day can result in a 1% increased risk of developing lung, skin, and bladder cancers23. Around 200 million individuals in the world are exposed to varying concentrations of inorganic As in drinking water24. Dietary intake from grain-based processed products and rice is another source for the overall As exposure23, which was associated with 240000 cancer cases, 4.3 million coronary heart disease in 201524. With climate change progresses, the bioavailability of As in soil is anticipated to rise, potentially leading to higher As concentrations in rice grains25.

Extensive research has been conducted to identify effective remediation strategies for As-contaminated soils. Global efforts to remediate As-contaminated soil have ranged from lab experiments to field applications. However, the scope of field trials remains constrained. To date, only a handful of approaches, including immobilization, phytoextraction, soil turnover and attenuation (T&A), have been subjected to real-world testing26,27,28. Comprehensive evaluations and comparative analyses of various soil remediation technologies are infrequent.

Our upcoming research examined the current soil remediation cases, disclosing their roles in improving food safety and soil health. Special attention is paid to As’s changing distribution across various environmental media, providing new insights for the remediation of As-contaminated agricultural soils. Through the above analysis, we seek to answer the question: in terms of the path to soil remediation, should we dilute or concentrate As in soil?

Data Collection and Analyzing Methods

Using “arsenic” and “agricultural soil” as the keywords, references were searched in the database of Web of Science since 2005. Published papers those reported the exact locations of longitude and latitude, and values of As concentration in soil were selected. There are in total 195 data points included in the analysis for soil As pollution status worldwide (Table S1). The selection of sampling points was designed to ensure a uniform distribution across the globe.

Field data of different soil remediation projects were obtained from literature and our field trials (Table S2).

The detailed data of As phytoextraction were from our remediation project conducted in Chenzhou City, Hunan Province, China, at 113°02′ E, 25°48′ N29,30. The area was severely polluted by the uncontrolled discharge of wastewater and waste residue from As smelting31. A five-year phytoextraction project was established. The As hyperaccumulator P. vittata was planted at 40 cm ╳ 40 cm intervals. The aboveground parts of P. vittata were harvested annually, and the resulting biomass with high contents of As was incinerated. The As-rich ash was sent to hazardous waste treatment facilities for landfill disposal. Plant and soil samples were collected and analyzed annually31,32,33,34. Post-remediation, six species of local vegetables were cultivated in treated and control (untreated) soils, and analyzed for As concentration to verify the phytoextraction effectiveness.

Field data elucidating the As immobilization process were from our field project from 2015 to 2018 in Anxin County, Baoding City, Hebei Province, China, located at 115°45′27″ ~ 115°45′30″ E and 38°49′1″ ~ 38°49′5″ N28. Soil was contaminated by As from long-term sewage irrigation. To mitigate this, ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) was applied at 0.1 wt% to immobilize As. Additionally, we incorporated findings from two As immobilization studies in France, which spanned durations of 8 and 15 years, respectively35,36. Across all three studies, iron (Fe) was employed as the immobilization agent, facilitating a direct comparison. We summarized and analyzed the vertical distribution of As well as its temporal dynamics, providing a framework for understanding the immobilization process.

Data used to illustrate the process of As biovolatilization are experimental values from a pot experiment37,38. Theoretic calculation referred to the established method39, while the parameters were set based on an actual As-contaminated paddy soil in Hunan Province, China.

where Csp’ is the As concentration of the polluted soil after treatment (mg/kg); Csp is the As concentration of the polluted soil before treatment (mg/kg); Fv is the volatilization flux [mg/(m2·a)]; Fwd is the wet-dry deposition flux [mg/(m2·a)]; t is the treatment time (a); ρ is the soil density (kg/m3), herein we use 2700 kg/m3; d is the soil depth (m), herein we use 0.2 m; Csc’ is the As concentration of the control soil surrounding the polluted soil after treatment (mg/kg); Csc is the As concentration of the control soil surrounding the polluted soil before treatment (mg/kg);

where Fwd is the wet-dry sedimentation flux [mg/(m2·a)]; Fw is the wet sedimentation flux [mg/(m2·a)]; Fd is the dry sedimentation flux [mg/(m2·a)]; C is the content of metal(loid)s in dust or rainfall [mg/kg]; D is the dust flux [kg/(m2·a)].

Data illustrating turnover and attenuation (T&A) process was from the same project of As immobilization in Anxin County, Baoding City, Hebei Province, China. Turnover and attenuation (T&A) mixes contaminated topsoil with clean soil from deeper layers to reduce the total concentration of contaminants40, suitable for slightly contaminated soil with enough thickness of clean soil layer. Soil is plowed at a depth of 0 ~ 60 cm.

Status of soil As pollution and its threat to food security

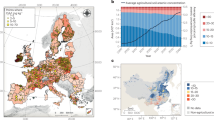

Arsenic is a toxic metalloid, and it ubiquitously exists in environment as a result of natural and human activities. The As concentration in the non-polluted soil is 0.1 ~ 40 mg/kg. However, high As concentrations in agricultural soil up to 1840 mg/kg have been observed worldwide41. Through our meta analysis of the As concentrations in agricultural soil (Fig. 1), extremely high concentrations of As in agricultural soil appearred in countries like Argentina42, Japan41, India43, and China44, posing a threat to both food safety and the health of their populations. Owing to the scarcity of comprehensive global data, the inequality in soil pollution exposure among regions or countries have been less scrutinized than those of air pollution, which are well-documented45. It is imperative to address the disproportionate exposure of low-income communities to both air and soil pollution.

Panel (a) presents the As concentrations in agricultural soils at the national level, with each number corresponding to a specific country: 1. Argentina, 2. Bangladesh, 3. Brazil, 4. Britain, 5. Canada, 6. China, 7. Colombia, 8. Ecuador, 9. India, 10. Indonesia, 11. Iran, 12. Italy, 13. Japan, 14. Kazakhstan, 15. Korea, 16. Macedonia, 17. Malawi, 18. Malaysia, 19. Nigeria, 20. Peru, 21. Russia, 22. Sri Lanka, 23. Sweden, 24. Thailand, 25. Ukraine, 26. US, 27. Vietnam. Panel (b) provides a global perspective on As pollution extent in agricultural soils.

The As-contaminated rice paddies, often submerged in water, needs to be paid special attention46. Rice is a dietary staple for over half of the world’s population, making it crucial to ensure its safety47. Long term use of As-contaminated groundwater as irrigation source for paddy significantly increased As in agricultural soil, and eventually in rice, especially in in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India48. Arsenic pollution in paddy soils is a widespread and naturally occurring issue, with levels able to accumulate over successive irrigation cycles49,50. With climate change progresses, the bioavailability of As in the soil is anticipated to rise, potentially leading to higher As concentrations in rice grains25.

Given the pervasive presence and potent toxicity of As, many efforts have been devoted to investigate suitable remediation schemes for As contaminated soil. Huge progress has been made in the past decade. However, the number of field trials is still limited26,27,28. Currently the evaluation or comparison of different soil remediation technologies is rare, but required for the decision-making.

Phytoextraction illustrated via a five-year field trial

In situ phytoextraction projects using As-hyperaccumulator P. vittata have been established on farmlands, residential areas, and industrial sites in China51, US52, Australia53, Japan26,54, Italy55, etc., with the highest As removal rate of ~18% per year achieved56,57,58.

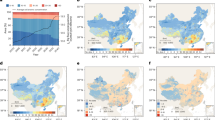

Our five-year phytoextraction trial (Fig. 2a) demonstrates that phytoextraction is highly efficient for soil As remediation. Before phytoextraction, rice grains contained As levels exceeding the maximum permissible limit of 1.0 mg/kg (dry weight), and vegetables like cabbage, lettuce, and spinach had As concentrations up to 45 times higher than the limit of 0.5 mg/kg (fresh weight). This posed a threat to human health, with 95% of human hair samples exceeding the World Health Organization’s critical value of 1.0 mg/kg.

a shows the process of phytoextraction. b depicts the initial state of As distribution and its subsequent changes during phytoextraction. Throughout the phytoremediation process, which spanned from 2001 to 2007, the soil As concentration in the majority of areas was successfully reduced to levels below the national standards for agricultural soil (Grade II, 30 mg/kg). c presents the concentration of As in leachate originating from the landfill. d shows the percentage of As flow during both phytoremediation and post-harvest processes.

With the phytoextraction progressing, the As concentration in soil gradually decreased. At the end of the remediation, soil As levels dropped from 50 mg/kg to below 30 mg/kg (Fig. 2b). Consequently, the As concentration in the agricultural produce derived from this soil sharply decreased, satisfying the national food safety standards (Fig. S1).

After phytoextraction, the As-enriched hyperaccumulator biomass (As concentration 0.1–1%) needs to be appropriately disposed. In this and most of the subsequent phytoextraction projects, incineration is adopted to decrease the volume and weight (by 71.5–86.6%)59. The combustion-derived ash containing a high concentration of As was sent to a hazardous waste treatment plant, where land disposal is commonly utilized to treat the metal-enriched ash, including underground perfusion, landfills, and surface structure treatment60. The recycling of valuable elements or energy from hyperaccumulator biomass has recently emerged as a valuable approach, not only alleviating post-harvest disposal challenges but also creating an additional economic incentive61,62.

It is important to note that the landfill disposal of As-enriched biomass still presents a risk of As release into the environment. Over time, there has been a documented increase in both total and extractable As levels, with peaks reaching 37 mg/kg and 11 mg/kg, respectively (Fig. 2c). The mass balance of As (Fig. 2d) indicated after five-year phytoextraction, 44% of the total As amount was removed from the soil, which means that phytoextraction was effective in remediating As-contaminated agricultural land. However, the resulting high-As waste may pose potential environmental hazards to the vicinity of the landfill.

Immobilization illustrated via three-year, eight-year, and 15-year cases in China and France

Immobilization refers to stabilizing As or reducing its mobility in soil with the aim of reducing its transport to plants, humans and water63. The immobilization efficiency mainly depends on the selection of adsorbent materials. Iron compounds and zero-valent iron (ZVI) are known to play a major role in As immobilization in the environment64. Fe oxides can oxidize AsIII to AsV, the less toxic and less mobile species of As, and also precipitate and sorb both As species, thus being the most important adsorbent for As in the soil.

Before immobilization, soil As levels peaked at 40.5 mg/kg, leading to wheat As levels of 0.57 mg/kg, which exceeded permissible limits. Our immobilization trial (Fig. 3a) reduced As mobility by approximately 27% and decreased wheat As concentration by about 39%, with no change in the total As level of soil (Fig. 3b), but a significant drop in the available As in the topsoil (Fig. 3c). After the immobilization, the yield of certain treatment also increased (Fig. S2), due to the alleviation of toxicity.

The longevity of As immobilizing agents is tested by a French study lasting 15 years35. The As-contaminated soil from secondary smelting, reaching 600 mg/kg, was treated with 1 wt% ZVI in 1997 and sampled in 2012. Compared to the control, the ZVI application significantly reduced the most soluble As fraction by 55%. Another experiment by the same authors targeted soil heavily contaminated by As from mining activities, at 1962 mg/kg36. After adding 1 wt% ZVI, an 8-year follow-up showed a 21% reduction in soluble As, largely due to the presence of ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite, which continue to immobilize As effectively.

Immobilization agent represented by Fe can achieve a sustained As stabilization ratio over extended periods. However, as immobilization does not affect the distribution of As in the soil, the fixed As is likely to be released under pH and Eh fluctuations65. Aging is an inescapable natural process that can result in the gradual decline of soil amendment efficacy66. Studies have been trying to obtain a consistent rate of aging, critical for an effective soil amendment67. It is recommended that this method be further refined though more long-term field experiment.

Biovolatilization and T&A illustrated via field observation, microcosm experiment, and theoretical calculation

Biovolatilization uses arsM (arsenite S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase)-expressing microorganisms to convert inorganic As into volatile methylated forms, such as DMA and MMA (Fig. 4a). Biovolatilization of As is a natural process observed in both terrestrial and marine ecosystems68. However, the natural rate is limited, requiring intentional enhancement through human intervention.

a provides a visual representation of the As biovolatilization process. b contrasts the distribution of As before and after the application of biovolatilization. c offers an illustration of the T&A approach. d depicts the vertical distribution of As, highlighting the changes that occur before and after the implementation of T&A.

Field investigations into the biovolatilization of As from agricultural soil are relatively scarce69. A field study in Bangladesh recorded an As biovolatilization rate of 240 mg/(ha·year), which is 0.07 μg/(m2·d), from a rice paddy irrigated with As-enriched groundwater69. In a separate instance, the use of rainwater, which is naturally rich in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as an irrigation source in Guangdong Province, China, resulted in a significantly higher biovolatilization flux of As, reaching 54 μg/(m2·d) in paddy soil70. Recently, a novel strategy has been proposed to intensify microbial As methylation, leveraging the transfer of the As methylation gene (arsM) through a synergistic interaction between lysogenic phages and their hosts37,38. This innovative approach has the potential to significantly increase the annual biovolatilization rate of As to ~8% of the total As per year.

Biovolatilized As in the atmosphere mainly exists as oxides attached to particulate matter (0.2–2.0 μm). Arsenic deposition varies by region, with dry deposition rates from 0.78 to 82 μg/(m2·month) and wet deposition rates from 1.8 to 247 μg(m2·month)71,72. Precipitation significantly affects As deposition, with a regression coefficient of 0.64. No studies have yet reported biovolatilized As deposition on agricultural soils. Based on local climate, there is an estimated increase of less than 0.05% of the total As load in the environment (Fig. 4b). Essentially, biovolatilization facilitates a more even distribution of As across a specific area. This process is complex, intertwined with the biogeochemical cycles of Fe, sulfur, and nitrogen73, necessitating further research to better understand and optimize its application.

Turnover and attenuation (T&A) mixes contaminated topsoil with clean soil from deeper layers (Fig. 4c) to reduce the total concentration of contaminants. The soil concentration of top soil was reduced by ~34% due to the dilution effect (Fig. 4d). After T&A, the As concentration in the crops was significantly reduced but yield was also slightly reduced due to the low content of nutrients in deeper layers. Application of fertilizer alleviated such a decrease (Fig. S3). Similar to biovolatilization, T&A also enabled a more even distribution of As, but from a vertical aspect.

To dilute or to concentrate?

We divide the As-contaminated soil remediation methods into three categories based on their effect on As distribution: concentration, dilution, and no change (Fig. 5). All three scenarios improved the food safety, soil health, and sustainability, the calculation methods of which are provided in the supplementary text.

The first category is concentration, represented by phytoextraction, which concentrates As from vast contaminated areas into a smaller biomass volume, achieving remarkable enrichment ratios of ~3000:174. With As affecting approximately 150300 km2 of Chinese agricultural soil, successful phytoextraction could yield 26 million tons of biomass with As levels over 1% (w:w). While beneficial for valuable metals like nickel and gold75, such high As concentrations pose significant environmental and health risks, complicating its management. A landfill receiving As- and Hg-containing hazardous waste, has been identified to release 408 kg of As via air within four years, leading to an 2280-fold increase in the concentration of As in the surrounding soil within a distance of 200 m76.

The second type is no-change, such as immobilization, which reduces As bioavailability without altering its distribution77. However, certain areas with high As levels persist, posing ongoing threats to health and the environment. Such areas can be likened to ticking time bombs, potentially threatening human health and the environment. Consequently, these sites necessitate ongoing monitoring and proactive management to mitigate any future risks78.

The third class is dilution, such as biovolatilization and T&A. This type reduces contamination by spreading pollutants more uniformly. With global As reserves at 11 million tons and land area at 149 million square kilometers, an extreme dilution scenario across the top 0-30 cm of soil would result in a concentration of 0.095 mg/kg, far below safety thresholds. A potential concern with biovolatilization is the atmospheric release of As. The minimum toxic As concentration affecting human health is 325 μg/m3, with a permissible exposure limit for inorganic As at 10 μg/m3. Under maximum biovolatilization, the As concentration 2 meters above soil would be approximately 0.12 ng/m3, well below the exposure limit. Moreover, the released As is mainly in less toxic organic forms.

A comparative analysis of different technologies is summarized in Table 1, which evaluate four prominent strategies based on their fundamental effect on As distribution—concentration, no-change, or dilution—alongside key practical metrics including remediation efficiency, cost, and multi-scale environmental impact.

Phytoextraction, a concentration strategy, is effective but slow and generates concentrated hazardous waste, posing a secondary disposal challenge at a local scale. In contrast, immobilization (no-change) acts rapidly to mitigate short-term risk but fails to remove As. Its primary drawback is the potential for As remobilization over time, necessitating long-term monitoring and turning remediation sites into long-term liabilities. The dilution-based strategies, T&A and biovolatilization, offer alternative pathways. T&A provides an immediate, low-cost solution for suitable sites but merely redistributes As vertically and can compromise soil fertility. Biovolatilization, meanwhile, facilitates a shift towards a more homogeneous regional distribution of As. Critically, our theoretical calculations indicate that the atmospheric flux from enhanced biovolatilization is negligible compared to background deposition, and the volatilized species are predominantly less toxic organo-arsenicals.

Therefore, for large areas of low-to-moderately As-contaminated agricultural land, dilution strategies present a viable alternative to concentration or no-change approaches. While promising, the approach remains unproven at scale due to the absence of large-scale biovolatilization applications and limited field-testing projects for T&A.

Implications and further research

Arsenic is a naturally occurring element that poses significant health hazards in regions with high concentrations. Despite research progress, our understanding of As’s global environmental cycles remains incomplete21, and effectively managing As-related risks remains challenging. In addressing As pollution, we propose that in certain contexts dilution might be an alternative to concentration or no-change scenario. However, this approach requires validation through large-scale applications and more extensive field testing, with each case evaluated on its specific conditions.

There is growing emphasis on multi-dimensional assessment of soil remediation technologies, considering factors such as economic cost, environmental impact, and energy consumption, with the goal of promoting sustainable remediation practices79. Our study introduces a novel perspective by highlighting the importance of spatial distribution of As in soils. We recommend that spatial heterogeneity be incorporated as a key criterion in evaluating the effectiveness of soil remediation.

Furthermore, appropriate soil remediation is crucial for not only safeguarding food security but also advancing the achievement of SDGs5. Effective remediation can enhance not only environmental quality but also socio-economic conditions. Therefore, we advocate for the use of specially designed, SDG-based indicators that address social, economic, and environmental dimensions to evaluate the impacts of soil remediation on regional soil health and local development.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

References

Caggia, V. et al. Root- exuded specialized metabolites reduce arsenic toxicity in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2314261121 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Remediation of heavy metal contaminated soil by asymmetrical alternating current electrochemistry. Nat. Commun. 10, 2440 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Reduced but still noteworthy atmospheric pollution of trace elements in China. One Earth 6, 536–547 (2023).

Yang, H. R. et al. Predicting heavy metal adsorption on soil with machine learning and mapping global distribution of soil adsorption capacities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14316–14328 (2021).

Hou, D. Y. et al. Metal contamination and bioremediation of agricultural soils for food safety and sustainability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 366–381 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Restoring Abandoned Farmland to Mitigate Climate Change on a Full Earth. One Earth 3, 176–186 (2020).

Trencher, G. et al. The evolution of “phase-out” as a bridging concept for sustainability: From pollution to climate change. One Earth 6, 854–871 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Overview assessment of risk evaluation and treatment technologies for heavy metal pollution of water and soil. J. Cleaner Prod. 379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134043 (2022).

Wei, R. et al. Heavy metal concentrations in rice that meet safety standards can still pose a risk to human health. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 84 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Escalating arsenic contamination throughout Chinese soils. Nat. Sustain. 7, 766–775 (2024).

Smith, H., Forshufvud, S. & WassÉN, A. Distribution of Arsenic in Napoleon’S Hair. Nature 194, 725–726 (1962).

Chen, K. et al. Evidence of arsenical copper smelting in Bronze Age China: A study of metallurgical slag from the Laoniupo site, central Shaanxi. J. Archaeol. Sci. 82, 31–39 (2017).

Shotyk, W., Cheburkin, A. K., Appleby, P. G., Fankhauser, A. & Kramers, J. D. Two thousand years of atmospheric arsenic, antimony, and lead deposition recorded in an ombrotrophic peat bog profile, Jura Mountains, Switzerland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 145, E1–E7 (1996).

Breuninger, E. S. et al. Marine and terrestrial contributions to atmospheric deposition fluxes of methylated arsenic species. Nat. Commun. 15, 9623 (2024).

Yao, B. M., Wang, S. Q., Xie, S. T., Li, G. & Sun, G.-X. Optimal soil Eh, pH for simultaneous decrease of bioavailable Cd, As in co-contaminated paddy soil under water management strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151342 (2022).

Dutré, V. & Vandecasteele, C. Solidification/stabilisation of arsenic-containing waste: Leach tests and behaviour of arsenic in the leachate. Waste Manag. 15, 55–62 (1995).

Schrenk, D. et al. Risk assessment of small organoarsenic species in food. EFSA J. 22, 90 (2024).

Wisessaowapak, C., Visitnonthachai, D., Watcharasit, P. & Satayavivad, J. Prolonged arsenic exposure increases tau phosphorylation in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells: The contribution of GSK3 and ERK1/2. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 84, 103626 (2021).

Martinez-Morata, I. et al. Nationwide geospatial analysis of county racial and ethnic composition and public drinking water arsenic and uranium. Nat. Commun. 13, 7461 (2022).

Sturchio, E. et al. Effects of arsenic on soil-plant systems. Chem. Ecol. 27, 67–78 (2013).

Chen, W. Q., Shi, Y. L., Wu, S. L. & Zhu, Y. G. Anthropogenic arsenic cycles: A research framework and features. J. Clean. Prod. 139, 328–336 (2016).

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Arsenic, metals, fibres, and dusts. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 100, 11–465 (2012).

Gundert-Remy, U. et al. High exposure to inorganic arsenic by food: the need for risk reduction. Arch. Toxicol. 89, 2219–2227 (2015).

Oberoi, S., Devleesschauwer, B., Gibb, H. J. & Barchowsky, A. Global burden of cancer and coronary heart disease resulting from dietary exposure to arsenic, 2015. Environ. Res. 171, 185–192 (2019).

Muehe, E. M., Wang, T., Kerl, C. F., Planer-Friedrich, B. & Fendorf, S. Rice production threatened by coupled stresses of climate and soil arsenic. Nat. Commun. 10, 4985 (2019).

Kohda, Y. H.-T. et al. Arsenic uptake by Pteris vittata in a subarctic arsenic-contaminated agricultural field in Japan: An 8-year study. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154830 (2022).

Majumdar, A. et al. Sustainable water management in rice cultivation reduces arsenic contamination, increases productivity, microbial molecular response, and profitability. J. Hazard. Mater. 466, 133610 (2024).

Wan, X., Lei, M., Yang, J. & Chen, T. Three-year field experiment on the risk reduction, environmental merit, and cost assessment of four in situ remediation technologies for metal(loid)-contaminated agricultural soil. Environ. Pollut. 266, 115193 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. Element case studies: Arsenic. In: van der Ent, A., Baker, A.J., Echevarria, G., Simonnot, MO., Morel, J.L. (eds) Agromining: Farming for Metals. Mineral Resource Reviews. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58904-2_22 (2021).

Chen, T., Lei, M., Wan, X., Zhou, X. & Yang, J. Application of phytoremediation technology to typical mining sites in China. In: Chen, T., Lei, M., Wan, X., Zhou, X. & Yang, J. (eds) Phytoremediation of Arsenic Contaminated Sites in China. SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7820-5_4 (2020).

Liao, X. et al. Spatial distributions of arsenic in contaminated paddy soils. Geogr. Res. 22, 635–643 (2003).

Wu, B. & Chen, T. Changes in hair arsenic concentration in a population exposed to heavy pollution: Follow-up investigation in Chenzhou City, Hunan Province, Southern China. J. Environ. Sci. 22, 283–289 (2010).

Liao, X. Y., Chen, T. B., Xie, H. & Liu, Y. R. Soil As contamination and its risk assessment in areas near the industrial districts of Chenzhou City, Southern China. Environ. Int. 31, 791–798 (2005).

Liao, X., Chen, T., Xie, H. & Xiao, X. Effect of application of P fertilizer on efficiency of As removal form Ascontanimated soil using phytoremediation: Field study. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 24, 455–462 (2004).

Tiberg, C. et al. Immobilization of Cu and As in two contaminated soils with zero-valent iron–Long-term performance and mechanisms. Appl. Geochem. 67, 144–152 (2016).

Kumpiene, J., Carabante, I., Kasiuliene, A., Austruy, A. & Mench, M. LONG-TERM stability of arsenic in iron amended contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116017 (2021).

Tang, X. et al. The arsenic chemical species proportion and viral arsenic biotransformation genes composition affects lysogenic phage treatment under arsenic stress. Sci. Total Environ. 780, 146628 (2021).

Tang, X. et al. Lysogenic bacteriophages encoding arsenic resistance determinants promote bacterial community adaptation to arsenic toxicity. ISME J. 17, 1142 (2023).

Lin, L.-F. et al. Atmospheric arsenic deposition in Chiayi county in southern Taiwan. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 13, 932–942 (2013).

Chen, C. H. & Chiou, I. J. Remediation of heavy metal-contaminated farm soil using turnover and attenuation method guided with a sustainable management framework. Environ. Eng. Sci. 25, 11–32 (2008).

Gankhurel, B. et al. Comparison of chemical speciation of lead, arsenic, and cadmium in contaminated soils from a historical mining site: Implications for different mobilities of heavy metals. ACS Earth Space Chem. 4, 1064–1077 (2020).

Pinter, I. F. et al. Arsenic and trace elements in soil, water, grapevine and onion in Jachal, Argentina. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 1485–1498 (2018).

Roychowdhry, T. Impact of sedimentary arsenic through irrigated groundwater on soil, plant, crops and human continuum from Bengal delta: Special reference to raw and cooked rice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46, 2856–2864 (2008).

Gong, Y. et al. Status of arsenic accumulation in agricultural soils across China (1985–2016). Environ. Res. 186, 109525 (2020).

Yu, W. et al. Global analysis reveals region-specific air pollution exposure inequalities. One Earth 7, 2063–2071 (2024).

Roberts, L. C. et al. Arsenic release from paddy soils during monsoon flooding. Nat. Geosci. 3, 53–59 (2010).

Storozhenko, S. et al. Folate fortification of rice by metabolic engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1277–1279 (2007).

Rahman, M. A., Hasegawa, H., Rahman, M. M., Rahman, M. A. & Miah, M. A. M. Accumulation of arsenic in tissues of rice plant (Oryza sativa L.) and its distribution in fractions of rice grain. Chemosphere 69, 942–948 (2007).

Meharg, A. A. & Rahman, M. M. Arsenic contamination of Bangladesh paddy field soils: implications for rice contribution to arsenic consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 229–234 (2003).

Peplow, M. US rice may carry an arsenic burden. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/news050801-5 (2005).

Yang, J. et al. Phytoaccumulation of As by Pteris vittata supplied with phosphorus fertilizers under different soil moisture regimes - A field case. Ecol. Eng. 138, 274–280 (2019).

Beans, C. Phytoremediation advances in the lab but lags in the field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7475–7477 (2017).

Niazi, N. K., Singh, B., Van Zwieten, L. & Kachenko, A. G. Phytoremediation potential of Pityrogramma calomelanos Var. Austroamericana and Pteris vittata L. grown at a highly variable arsenic contaminated site. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 13, 912–932 (2011).

Yang, C. Y., Ho, Y. N., Inoue, C. R. & Chien, M. F. Long-term effectiveness of microbe-assisted arsenic phytoremediation by Pteris vittata in field trials. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140137 (2020).

Cantamessa, S., Massa, N., Gamalero, E. & Berta, G. Phytoremediation of a highly arsenic polluted site, using Pteris vittata L. and arbuscular mycorrhizal Fungi. Plants 9, 1211 (2020).

Huang, Z.-C. et al. Arsenic uptake and transport of Pteris vittata L. as influenced by phosphate and inorganic arsenic species under sand culture. J. Environ. Sci.-China 19, 714–718 (2007).

Ebbs, S., Hatfield, S., Nagarajan, V. & Blaylock, M. A Comparison of the dietary arsenic exposures from ingestion of contaminated soil and hyperaccumulating pteris ferns used in a residential phytoremediation project. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 12, 121–132 (2010).

Wan, X. M., Lei, M. & Chen, T. B. Cost–benefit calculation of phytoremediation technology for heavy-metal-contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 563–564, 796–802 (2016).

Nie, C. J. et al. Pyrolysis characteristic of arsenic hyperaccumulators and its relation to arsenic content. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 27, 721–726 (2007).

Cui, X. Q. et al. A review on the thermal treatment of heavy metal hyperaccumulator: Fates of heavy metals and generation of products. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 123832 (2021).

Chen, S., Guo, G., Lei, M., Peng, H. & Ju, T. Identifying the habitat suitability of Pteris vittata in China and associated key drivers using machine learning models. Sci. Total Environ. 954, 176213 (2024).

Cai, W., Chen, T., Lei, M. & Wan, X. Effective strategy to recycle arsenic-accumulated biomass of Pteris vittata with high benefits. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 143890 (2021).

Palansooriya, K. N. et al. Soil amendments for immobilization of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils: A critical review. Environ. Int. 134, 105046 (2020).

Freitas, E. T. F., Montoro, L. A., Gasparon, M. & Ciminelli, V. S. T. Natural attenuation of arsenic in the environment by immobilization in nanostructured hematite. Chemosphere 138, 340–347 (2015).

Wang, X. M. et al. Efficient co-stabilization of arsenic and cadmium in farmland soil by schwertmannite under long-term flooding-drying condition. Environ. Pollut. 350, 124005 (2024).

Tiberg, C. et al. Immobilization of Cu and As in two contaminated soils with zero-valent iron - Long-term performance and mechanisms. Appl. Geochem. 67, 144–152 (2016).

Wang, L. W. et al. Long-term immobilization of soil metalloids under simulated aging: Experimental and modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150501 (2022).

Vriens, B., Lenz, M., Charlet, L., Berg, M. & Winkel, L. H. E. Natural wetland emissions of methylated trace elements. Nat. Commun. 5, 3035 (2014).

Mestrot, A. et al. Field fluxes and speciation of arsines emanating from soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 1798–1804 (2011).

Lin, X., Li, H. & Ai, S. Effect of atmospheric H2O2 on arsenic methylation and volatilization from rice plants and paddy soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 217, 112100 (2021).

Huang, M. J. et al. Atmospheric arsenic deposition in the Pearl River Delta region, South China: Influencing factors and speciation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2506–2516 (2018).

Savage, L., Carey, M., Williams, P. N. & Meharg, A. A. Maritime deposition of organic and inorganic arsenic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 7288–7295 (2019).

Zhu, Y. G., Xue, X. M., Kappler, A., Rosen, B. P. & Meharg, A. A. Linking genes to microbial biogeochemical cycling: Lessons from arsenic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7326–7339 (2017).

Lei, M. et al. Reaction mechanism of arsenic capture by a calcium-based sorbent during the combustion of arsenic-contaminated biomass: A pilot-scale experience. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 13, 24 (2019).

van der Ent, A. et al. Current developments in agromining and phytomining, 13th SGA Biennial Meeting on Mineral Resources in a Sustainable World, Nancy, FRANCE, Aug 24-27, 2015; Nancy, FRANCE, 1495-1496 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Pathway, flux and accumulation of pollutant emission from landfill receiving As- and Hg-containing hazardous waste. J. Clean. Prod. 403, 136697 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Enhanced arsenate immobilization by kaolinite via heterogeneous pathways during ferrous iron oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c01976 (2024).

Tu, Y. L. et al. Field demonstration of on-site immobilization of arsenic and lead in soil using a ternary amending agent. J. Hazard. Mater. 426, 127791 (2022).

Fan, Z. X. et al. A study of multi-dimensional evaluation of MPE systems for soil remediation. in 2024 IEEE 19TH Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, ICIEA 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIEA61579.2024.10665211 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no. 2023YFD1702300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.XM.; methodology, Z.WB., and W.YL.; investigation, W.XM., Z.WB., and W.YL.; writing – original draft, W.XM.; writing – review & editing, L.M.; supervision, C.TB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, X., Zeng, W., Wang, Y. et al. Revisiting the remediation of arsenic-contaminated agricultural soil: a review of real-world testing. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00111-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00111-y